Introduction

The San Juan Formation is a richly fossiliferous Ordovician carbonate unit characteristic of the Cuyania (Precordillera) terrane of west-central Argentina (Astini et al., Reference Astini, Benedetto and Vaccari1995; Benedetto et al., Reference Benedetto, Sánchez, Carrera, Brussa and Salas1999, Reference Benedetto, Vaccari, Waisfeld, Sánchez and Foglia2009; Keller Reference Keller1999, Reference Keller2012; Benedetto, Reference Benedetto2004) (Fig. 1). Among brachiopods, most work has been directed toward the study of rhynchonelliforms (Herrera and Benedetto, Reference Herrera and Benedetto1989; Benedetto and Herrera, Reference Benedetto and Herrera1993; Benedetto, Reference Benedetto2001, Reference Benedetto2007; Benedetto et al., 2003; Benedetto and Cech, Reference Benedetto and Cech2006; among others), with little attention being paid to the linguliforms. Recently, Benedetto (Reference Benedetto2015) described a Middle Ordovician brachiopod assemblage from the black shales and marls (Los Azules Formation) overlying the San Juan Formation (Fig. 2), which includes minute rhynchonelliforms, obolids, acrotretids, and the craniid Philhedra. On the other hand, Holmer et al. (Reference Holmer, Popov, Lehnert and Ghobadi Pour2015) listed a fauna composed mainly of acrotretids from the San Rafael Block in the southernmost part of the Cuyania terrane. Here we describe the first linguliforms and craniifoms recovered from the upper part of the San Juan Formation, of Darriwilian age, and briefly discuss their biogeographic affinities in the light of the hypothesis of Cuyania as a Laurentian-derived terrane.

Figure 1 Lower Paleozoic basins of southern South America showing location of the Precordillera folded belt and the Central Andean Basin. The interposed striped area corresponds to deep-water clastics and volcano-sedimentary successions.

Figure 2 Outcrops of Ordovician rocks in the central and northern Precordillera Basin (left). Dark grey: deep-water clastic deposits; limestone symbol: Cambro-Ordovician platform carbonates. Location of fossiliferous localities: (1) Cerro Viejo, (2) Cerro La Chilca, (3) Villicum Range. Generalized column of San Juan Formation in the studied area (center) and details of intervals bearing linguliforms (right).

Stratigraphic setting and material

The Precordillera of western Argentina is characterized by a thick Cambro-Ordovician carbonate succession recording deposition on a low-latitude, passive-margin platform (Fig. 2). The upper part corresponds to the San Juan Formation, a 300–360 m thick carbonate unit ranging in age from the late Tremadocian to mid Darriwilian. Its basal contact is a flooding surface associated with a rapid change from restricted platform dolostones and limestones (La Silla Formation) to subtidal open-marine carbonate facies (Fig. 2) (Keller et al., Reference Keller, Cañas, Lehnert and Vaccari1994; Cañas, Reference Cañas1999). A lower interval of microbial-sponge reefs is followed by a variety of lithofacies ranging from inner-ramp, wave-agitated shoal environments to deep-ramp settings (Cañas and Carrera, Reference Cañas and Carrera1993, Reference Cañas and Carrera2003; Cañas, Reference Cañas1999). Skeletal and intraclastic wackestones and packstones bearing rich benthic faunas deposited in mid-ramp settings are the most typical lithologies of the San Juan Formation (Cañas, Reference Cañas1999). Macrofossils include sponges, receptaculitids, bryozoans, brachiopods, gastropods, rostroconchs, cephalopods, trilobites, ostracods, echinoderms, and algae (see compilation by Benedetto, Reference Benedetto2003). A rapid sea level rise associated with tectonic activity led to a diachronous drowning of the carbonate ramp. In the central part of the basin, this event took place around the Dapingian/ Darriwilian transition, leading to deposition of a rhythmic alternation of graptolitic black shales and marlstones named Los Azules Formation (Astini, Reference Astini2003; Carrera et al., Reference Carrera, Fenoglio, Albanesi and Voldman2013; Benedetto, Reference Benedetto2015).

The fauna described herein was collected from the uppermost tens of meters of the San Juan Formation at Cerro Viejo, Cerro La Chilca, and Sierra de Villicum (Fig. 2). This interval consists of richly fossiliferous nodular wackestones and mudstones deposited in middle- to outer-ramp, low-energy settings below storm-wave base (Cañas, Reference Cañas1999). It encompasses the Ahtiella argentina Biozone, the uppermost of the six brachiopod biozones recognized through the San Juan Formation (Herrera and Benedetto, Reference Herrera and Benedetto1991; Sánchez et al., 1996; Benedetto, Reference Benedetto2002, Reference Benedetto2007). The Darriwilian age of this biozone is well constrained by conodonts spanning the Paroistodus horridus Subzone within the Lenodus variabilis Zone (Albanesi and Ortega, Reference Albanesi and Ortega2002; Ortega et al., Reference Ortega, Albanesi and Frigerio2007) and the lower part of the succeeding Yangtzeplacognathus crassus Zone (Mestre and Heredia, Reference Mestre and Heredia2013; Serra et al., Reference Serra, Albanesi, Ortega and Bergström2015). According to the time-slices schema proposed by Bergström et al. (Reference Bergström, Chen, Gutiérrez Marco and Dronov2009) the sampled interval of the San Juan Formation fall mostly within Dw1 (L. variabilis Zone) but can reach the lower part of Dw2 (Fig. 2).

The San Juan Formation and its transition to the overlying black shales are well exposed at Cerro La Chilca, approximately 50 km south of the Jáchal village (Fig. 2). The uppermost 15 m of the San Juan Formation consist of nodular wackestones-mudstones, spiculitic wackestones, and crinoidal grainstones-packestones. Macrofossils are very abundant through the entire interval. Among linguliforms, the new siphonotretid Chilcatreta and the linguloidean Glossella and Lingulasma? are relatively common, the latter two often being preserved as conjoined specimens in life position. Sedimentologic and taphonomic evidence indicates a low-energy environment dominated by deposition of open shelf muds punctuated by sporadic storm events (Carrera et al., Reference Carrera, Fenoglio, Albanesi and Voldman2013). The section is capped by a lithoclastic rudstone followed by amalgamated grainstone beds interpreted as crinoidal shoals reworked by fair-weather wave-base action.

The second sampled locality is Cerro Viejo, an N-S trending range located ~20 km northeast of Jáchal City (Fig. 2). The San Juan Formation and the succeeding black shales referred to the Los Azules Formation form a westward-dipping homoclinal sequence that is deeply incised by the Los Gatos Creek (Ottone et al., Reference Ottone, Albanesi, Ortega and Holfeltz1999; Sorrentino et al., Reference Sorrentino, Benedetto and Carrera2009). There, the upper 24 m of the San Juan Formation show a general deepening upward trend ranging from bioclastic packstones-wackestones in the base to glauconite-rich, nodular bioturbated mudstones in the upper part. Most of these levels have yielded rich rhynchonelliformean brachiopod assemblages and few remains of linguloids, trematids, and a probable craniiform.

In the Villicum Range (Sierra de Villicum), located to the northeast of San Juan City (Fig. 2), the stratigraphic interval of the San Juan Formation encompassing the Ahtiella argentina Zone attains ~15 m thickness and consists of bioclastic wackestones and laminated mudstones yielding conodonts of the Lenodus variabilis Zone (Sarmiento, Reference Sarmiento1985, Reference Sarmiento1991). The linguliforms described herein come from dark grey mudstones just in the transition to the succeeding alternation of marls and black shales of the Los Azules Formation, which mark the onset of a rapid deepening of the basin.

Repository and institutional abbreviations

All specimens are deposited in Centro de Investigaciones en Ciencias de la Tierra (CICTERRA), Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas and Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (institutional abbreviation CEGH-UNC).

Biogeographical remarks

As stated above, knowledge of linguliformean brachiopods from the extensive lower Cambrian to Middle Ordovician carbonate platform deposits of the Precordillera is still rudimentary. A varied Upper Cambrian linguliform assemblage was described by Holmer et al. (Reference Holmer, Popov and Lehnert1999) from carbonate olistoliths of the Mendoza Province. It consists mainly of acrotretids, all genera and two species of which are known from Laurentia (North America and Greenland). In that paper, the genus Curticia was documented for the first time outside Laurentia. Picnotreta, Neotreta, and Stilpnotreta, on the other hand, are widespread taxa with lesser biogeographic significance; Picnotreta, for instance, has been recorded from Antarctica, Australia, New Zealand, Siberia, and Kazakhstan (Popov et al., Reference Popov, Holmer and Gorjansky1996). According to Holmer et al. (Reference Holmer, Popov and Lehnert1999), this upper Cambrian lingulate fauna demonstrates a consistent similarity to the contemporaneous assemblages of North America, but also displays an important link with Siberian assemblages.

As Popov et al. (Reference Popov, Holmer, Bassett, Ghobadi Pour and Percival2013) pointed out, the Middle Ordovician is the best known interval in terms of the biogeographical distribution of lingulate brachiopods. Besides the fauna studied herein, the only other assemblage described from the Precordillera Basin comes from the dysoxic black shales and marls of the Los Azules Formation, of lower-mid Darriwilian age (Benedetto, Reference Benedetto2015). It consists of the obolids Palaeoglossa minima Benedetto, Reference Benedetto2015, and Anomaloglossa? sp., the acrotretid Cyrtonotreta vasculata Benedetto, Reference Benedetto2015, and the craniid Philhedra pauciradiata Benedetto, Reference Benedetto2015. Palaeoglossa is a widespread genus recorded in England, South China, southern Urals, and Australia. The type species of Cyrtonotreta comes from the Pratt Ferry Formation of Alabama, but also occurs in Sweden (Holmer, Reference Holmer1989), Kazakhstan (Popov, Reference Popov2000; Nikitina et al., Reference Nikitina, Popov, Neuman, Bassett and Holmer2006), Bohemia (Mergl, Reference Mergl2002), and New Zealand (Percival et al., Reference Percival, Wright, Simes, Cooper and Zhen2009). The palaeogeographic distribution of Philhedra during the Early-Middle Ordovician is difficult to assess because numerous species attributed to this genus are in need of revision. By the Late Ordovician, Philhedra seems to have been restricted to Baltica (Popov et al., Reference Popov, Holmer, Bassett, Ghobadi Pour and Percival2013).

Holmer et al. (Reference Holmer, Popov, Lehnert and Ghobadi Pour2015) reported a list of taxa from the San Rafael region in the southernmost extent of the Cuyania terrane (Bordonaro et al., Reference Bordonaro, Keller and Lehnert1996; Astini, Reference Astini2003). The older assemblage recovered from limestones of the Ponon Trehue Formation yielded conodonts of the L. variabilis Biozone and consequently is coeval to the upper San Juan Formation fauna. The Ponon Trehue assemblage is dominated by Numericoma and displays similarities with the Whiterockian fauna from the Antelope Valley Limestone of Nevada. A second assemblage was recovered from carbonate-rich beds of the Lindero Formation of late Darriwilian-earliest Sandbian age (Pygodus serra and P. anserinus Biozones) (Lehnert et al., Reference Lehnert, Bergström, Keller and Bordonaro1999). The fauna is dominated by the genus Mendozotreta, whose type species is Conotreta? devota Krause and Rowell, a very common acrotretid in the Meiklejohn Peak carbonate mud mound of central Nevada (Ross, Reference Ross1972; Krause and Rowell, Reference Krause and Rowell1975). The Lindero Formation also yielded Conotreta cf. multisinuata Cooper, Rhysotreta corrugata Cooper, Scaphelasma septatum Cooper, Ephippelasma minutum Cooper, Biernatia minor Cooper, Elliptoglossa sylvanica Cooper, Rowellella margarita Krause and Rowell, and Paterula cf. perfecta Cooper. According to Holmer et al. (Reference Holmer, Popov, Lehnert and Ghobadi Pour2015), this assemblage shows strong Laurentian affinities, in particular with the lingulate fauna from the Pratt Ferry Formation of Alabama.

The biogeographic affinities of the small linguliform assemblage from the San Juan Formation described in this paper are mostly with the Laurentian and Baltic faunas. For instance, Glossella is a typical taxon of the North American Great Basin, and also occurs in Scotland, originally a part of Laurentia. This genus has been reported otherwise from the East European platform (Poland, Estonia, and the Russian peri-Baltic area). The San Juan specimens assigned tentatively to Lingulasma closely compare in size, shape and ornamentation to Lingulasma occidentale Cooper, Reference Cooper1956, from the yellowish limestones overlying the Eureka Quartzite in Monitor Range of Nevada (Cooper, Reference Cooper1956). Similar to Glossella, the genus Lingulasma occurs in approximately coeval beds (Kunda regional stage, lower Darriwilian) of the Baltic region (Norway, Sweden, Russia). Although by the Late Ordovician Trematis becomes a widespread genus, it is noteworthy that its first records in lower Darriwilian rocks are confined to the Precordillera and the Great Basin of Nevada. Finally, the siphonotretid Chilcatreta n. gen. is presently restricted to the Precordillera Basin.

The linguliform brachiopods from the autochtonous successions of northwesten Argentina, which constitute the southern extent of the large Central Andean Basin (Fig. 1), are mostly of Tremadocian-Floian age and therefore cannot be reliably compared with the younger Precordilleran faunas. It has long been acknowledged that the Lower Ordovician rhynchonelliforms from NW Argentina and Bolivia are very different from those of the Precordillera, having a definite Gondwanan (North Africa and peripheral South European and Asian terranes) biogeographic signature (Benedetto, Reference Benedetto1998; Benedetto et al., 2009; Benedetto and Muñoz, 2015, Reference Benedetto and Muñoz2016; Muñoz and Benedetto, Reference Muñoz and Benedetto2016). To date, the scarce Lower Ordovician linguliforms described from northwest Argentina include Libecoviella, which has been recorded from approximately coeval strata of the Prague Basin (Mergl, Reference Mergl2002) and Australia (Brock and Holmer, Reference Brock and Holmer2004), and Leptembolon, known from Estonia and the South Urals (Popov and Holmer, Reference Popov and Holmer1994). The Tremadocian material ascribed by Harrington (Reference Harrington1937, Reference Harrington1938) to Obolus (Broeggeria) and Lingulella is currently under revision by the authors.

The Late Cambrian lingulate assemblage from northwest Argentina described by Mergl et al. (2015) (Furongian; but see age discussion by Muñoz and Benedetto, Reference Muñoz and Benedetto2016), besides Libecoviella and the new elkaniid Saltaia, includes Eurytreta and Schizambon, both suggesting closest affinities to the warm/temperate assemblages of Laurentia and Kazakhstan. In addition, Eurytreta has been reported from the approximately coeval Tiñu Formation of the Mexican Oaxaqia terrane (Streng et al., Reference Streng, Mellbin, Landing and Keppie2011), which by the Cambrian/Ordovician transition is thought to have been located at southern-temperate latitudes close to the Amazonian margin of Gondwana (Keppie et al., Reference Keppie, Dostal, Murphy and Nance.2008).

In summary, linguliforms from the Cuyania terrane display major similarities with those inhabiting low-latitude palaeocontinents, as the cluster analysis carried out by Popov et al. (Reference Popov, Holmer, Bassett, Ghobadi Pour and Percival2013) demonstrated. This is consistent with previous multivariate analyses of the Precordilleran rhynchonelliform brachiopods, which by the Floian-Dapingian are still linked to the Toquima-Table Head faunal Realm of Laurentia (Benedetto, Reference Benedetto2003, Harper et al., Reference Harper, Bruton and Rasmussen2008, Reference Harper, Owen and Bruton2009; Benedetto et al., Reference Benedetto, Vaccari, Waisfeld, Sánchez and Foglia2009). By the latest Dapingian-early Darriwilian, ~40% of genera show Baltic and Celtic affinities (Benedetto, Reference Benedetto2003). At that time, Cuyania is thought to have been situated relatively close to the Gondwana margin but not too far from Laurentia as to prevent dispersal of species having long-lived planktotrophic larvae. Considering the time span since the rifting of Cuyania from the Ouachita Embayment of Laurentia, from which it became detached by the early mid Cambrian (Astini et al., Reference Astini, Benedetto and Vaccari1995; Thomas and Astini, Reference Thomas and Astini1996, Reference Thomas and Astini2003), until its docking to Gondwana by the late Middle Ordovician, it appears that the interposed West Iapetus Ocean was relatively narrow, probably ~1500 km wide (Benedetto, Reference Benedetto2004). Such a paleogeographic scenario could account for the Laurentian affinities of a portion of the brachiopod fauna. However, there is not yet a good explanation for the Baltic signature of a number of linguliform and rhynchonelliform brachiopods from the Cuyania terrane other than both regions were situated in similar low-temperate latitudes. According to the global ocean surface circulation model by Pohl et al. (Reference Pohl, Nardin, Vandenbroucke and Donnadieu2015) for the Middle Ordovician (460 Ma), a large clockwise Rheic Gyre developed south of 40°S connecting the cold-water platforms of northwestern Gondwana with Baltica. Along the northern limb of the Rheic, convergence the Southern Westerlies flow along the Andean–North African Gondwana margin before intercepting the Baltica continent, which at that time was still located in temperate latitudes (Cocks and Torsvik, Reference Cocks and Torsvik2005). We infer that such an oceanic current could have established a connection of the Cuyania terrane with Laurentia and further eastward to Avalonia and Baltica through the East Iapetus Ocean (cf. Muñoz and Benedetto, Reference Muñoz and Benedetto2016, fig. 4), but a more detailed analysis is needed to understand the faunal relationships between Cuyania and Baltica.

Systematic paleontology

The systematic classification follows that of the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology (Bassett, Reference Bassett2000, Reference Bassett2007; Holmer and Popov, Reference Popov2000, Reference Holmer and Popov2007).

Class Lingulata Gorjansky and Popov, Reference Gorjansky and Popov1985

Order Lingulida Waagen, Reference Waagen1885

Superfamily Linguloidea Menke, Reference Menke1828

Family Obolidae King, Reference King1846

Subfamily Glossellinae Cooper, Reference Cooper1956

Genus Glossella Cooper, Reference Cooper1956

Type species

Glossella papillosa Cooper, Reference Cooper1956, from the Pratt Ferry Formation, Alabama, USA. Middle Ordovician (late Darriwilian), by original designation.

Glossella cuyanica new species

Figure 3 Glossella cuyanica Lavié and Benedetto n. sp. (1–4) holotype CEGH-UNC 26922, specimen with conjoined valves, (1) dorsal view, (2) ventral view, (3) lateral view, (4) detail of ornamentation; (5) external mold of conjoined specimen in life position CEGH-UNC 26925; (6, 13, 14) paratype CEGH–UNC 26926, (6) detail of ornamentation on the lateral slope, (13) incomplete partially exfoliated ventral valve, (14) detail of ornamentation of anterior region; (7) paratype CEGH-UNC 26924, exfoliated dorsal valve; (8, 9) paratype CEGH-UNC 26928, (8) dorsal valve internal mold, (9) latex cast; (10–12) paratype CEGH-UNC 26927, (10) partially decorticarted dorsal valve, (11) detail of ornamentation, (12) posterior region. Lingulasma? sp. (15, 16) conjoined specimen CEGH-UNC 26935, (15) ventral view, (16) detail of ornamentation; (17, 18) fragmentary conjoined specimen CEGH-UNC 26934, (17) anterior region, (18) detail of ornamentation. Scale bars represent 3 mm, except (15) and (17), which are 5 mm; and (4), (6), (11), and (18), which represent 1 mm.

Types

Holotype: A specimen with conjoined valves, CEGH-UNC 26922 from Cerro La Chilca. Paratypes: A conjoined specimen in life position, one dorsal valve, and two ventral valves from Cerro La Chilca; two ventral valves and one dorsal valve from Cerro Viejo (Quebrada Los Gatos), CEGH-UNC 26923–26929.

Diagnosis

Elongate suboval dorsibiconvex shell; dorsal valve with a pair of low rounded carinas fading anteriorly; dorsal pseudointerarea reduced to absent. Ornamentation of minute drop-shaped or wedge-shaped papillae arranged in radial rows numbering five to eight per millimeter, spreading toward lateral margins, indistinct on the umbonal region and anterior third of valves.

Occurrence

Darriwilian, upper part of the San Juan Formation at Cerro La Chilca and Cerro Viejo (Quebrada Los Gatos), San Juan Province, Precordillera of west-central Argentina.

Description

Shell dorsibiconvex with elongate suboval outline (length/width ratio=1.80); largest specimen 14 mm long and 9.3 mm wide; maximum width slightly anterior to midlength. Anterior margin evenly rounded; lateral margins gently curved. Ventral pseudointerarea orthocline with broad triangular pedicle groove. Dorsal valve with thickened posterior margin; dorsal pseudointerarea almost absent. A pair of low rounded carinae variably developed on the posterior third of dorsal valve, fading at midlength. Shell surface with minute granules or papillae arranged in radial rows spreading toward margins where they number five to eight per millimeter. Granules small, heart-shaped and densely crowded on midsection (Fig. 3.14) becoming drop-shaped or wedge-shaped marginally with their steeper slopes facing anteriorly and trails pointing posteriorly (Fig. 3.4, 3.6), where they number 20–24/mm on the lateral valve slopes; granules indistinct on the umbonal region and anterior third of valves, which bear only fine closely spaced growth lines. Dorsal valve with a weak long median ridge (Fig. 3.7).

Etymology

From the Cuyania terrane.

Remarks

The Precordilleran species resembles Glossella livida Krause and Rowell, Reference Krause and Rowell1975, from the Darriwilian of Nevada, in its dorsibiconvex profile, dorsal valve with thickened posterior margin lacking pseudointerarea, and ornamentation pattern of radially arranged granules, which are absent on the umbonal and anteromedial regions. The main difference with the North American species lies in the shell size, the Argentinean form being two to three times larger. In addition, G. livida has a definitely oval and more elongate shell and the dorsal valve in not carinate. The species G. liumbona Cooper, Reference Cooper1956 (Bromide Formation of Oklahoma, upper Sandbian) resembles G. cuyanica n. sp. in having dorsibiconvex suboval shells but differs in that radial rows of granules are developed on the entire shell surface, including the anterior third. Moreover, in G. liumbona the outline tends to be subrectangular and more elongate (length/width ratio 1.98). G. papillosa Cooper (Pratt Ferry Formation of Alabama, Darriwilian) is quite similar to G. cuyanica in shell size and shape but granules are present over the entire surface, as in G. liumbona and, in addition, rows are more closely spaced than in our species. G. pulcherrima (Reed, Reference Reed1917), from the Sandbian of Scotland (Williams, Reference Williams1962), can be distinguished from G. cuyanica by the equidistant arrangement of rows of granules (instead of becoming more separated toward margins) and the ornamented anterior shell surface.

Family Lingulasmatidae Winchell and Schuchert, Reference Winchell and Schuchert1893

Genus Lingulasma Ulrich, Reference Ulrich1889

Type species

Lingulasma schucherti Ulrich, Reference Ulrich1889, from the Richmondian (Late Ordovician) of Illinois, USA, by original designation.

Lingulasma? sp.

Materials

Two incomplete conjoined specimens CEGH-UNC 26934-26935, from the upper part of the San Juan Formation, Cerro La Chilca, one incomplete conjoined specimen CEGH-UNC 26931 from the transitional beds from the San Juan Formation to the Los Azules Formation, Quebrada La Pola, Sierra de Villicum, San Juan Province.

Description

Shell thick, large (up to 16.2 mm wide), subrectangular, with subparallel lateral margins; anterior margin almost straight, with anterolateral extremities narrowly rounded. Posterior shell region not preserved. Ornamentation well developed throughout the shell surface consisting of radial rows of minute pustules developed at the intersection with growth lines with 13–15/mm. Radial rows densely spaced, numbering eight to nine per millimeter on the median region, becoming more separated and less defined toward margins where concentric growth lines prevail. Interiors not preserved.

Remarks

Although the San Juan specimens closely resemble the genus Lingulasma in shell shape and convexity, and exhibit the distinctive ornamentation of radial rows of pustules, the generic attribution to Lingulasma is not conclusive because of the lack of information on internal characters. It should be noted that ornament of radially aligned small pustules is also present in Leontiella and Glossella, so this feature alone is insufficient to attribute with certitude our specimens to Lingulasma. In all available shells the posterior half is broken and crushed and then the distinctive elevated platforms are not preserved. Cooper (Reference Cooper1956) noted that most specimens of Lingulasma are preserved with the beak and the prominent inner platforms crushed or broken. According to Savazzi (Reference Savazzi1986), this peculiar preservation can be attributed to its infaunal vertical position. In general, Lingulasma has been described in life position within burrows in sandy sediments (Cooper, Reference Cooper1956; Pickerill, Reference Pickerill1973), which does not permit observation of the posterior third of shell, including the morphology of the pseudointerarea. A very similar preservation is exhibited by the San Juan specimens. Among the numerous species described by Cooper (Reference Cooper1956) from the Ordovician of North America, our material closely resembles L. occidentale Cooper, Reference Cooper1956, in being medium-sized for the genus, and in its straight subparallel lateral shell margins with rounded anterolateral extremities. Moreover, ornamentation in both species is very similar, with radial rows of rounded pustules with nine to ten per millimeter. From L. schucherti Cooper, Reference Cooper1956, and L. galanensis Cooper, Reference Cooper1956, our specimens differ in having considerably smaller size, different shape, and different arrangement of radial ornamentation. L. compactum Cooper, Reference Cooper1956, differs in its poorly developed radial ornamentation on the flanks and along the margins, and rows of pustules are slightly more densely spaced (approximately seven per millimeter), whereas L. matutinum Cooper, Reference Cooper1956, differs from the Argentinean species in having fewer and more widely spaced radial rows.

Superfamily Discinoidea Gray, Reference Gray1840

Family Trematidae Schuchert, 1893

Genus Trematis Sharpe, Reference Sharpe1848

Type species

Orbicula terminalis Emmons, Reference Emmons1842. Upper Ordovician (Sandbian), North America, by original designation.

Trematis sp. indet.

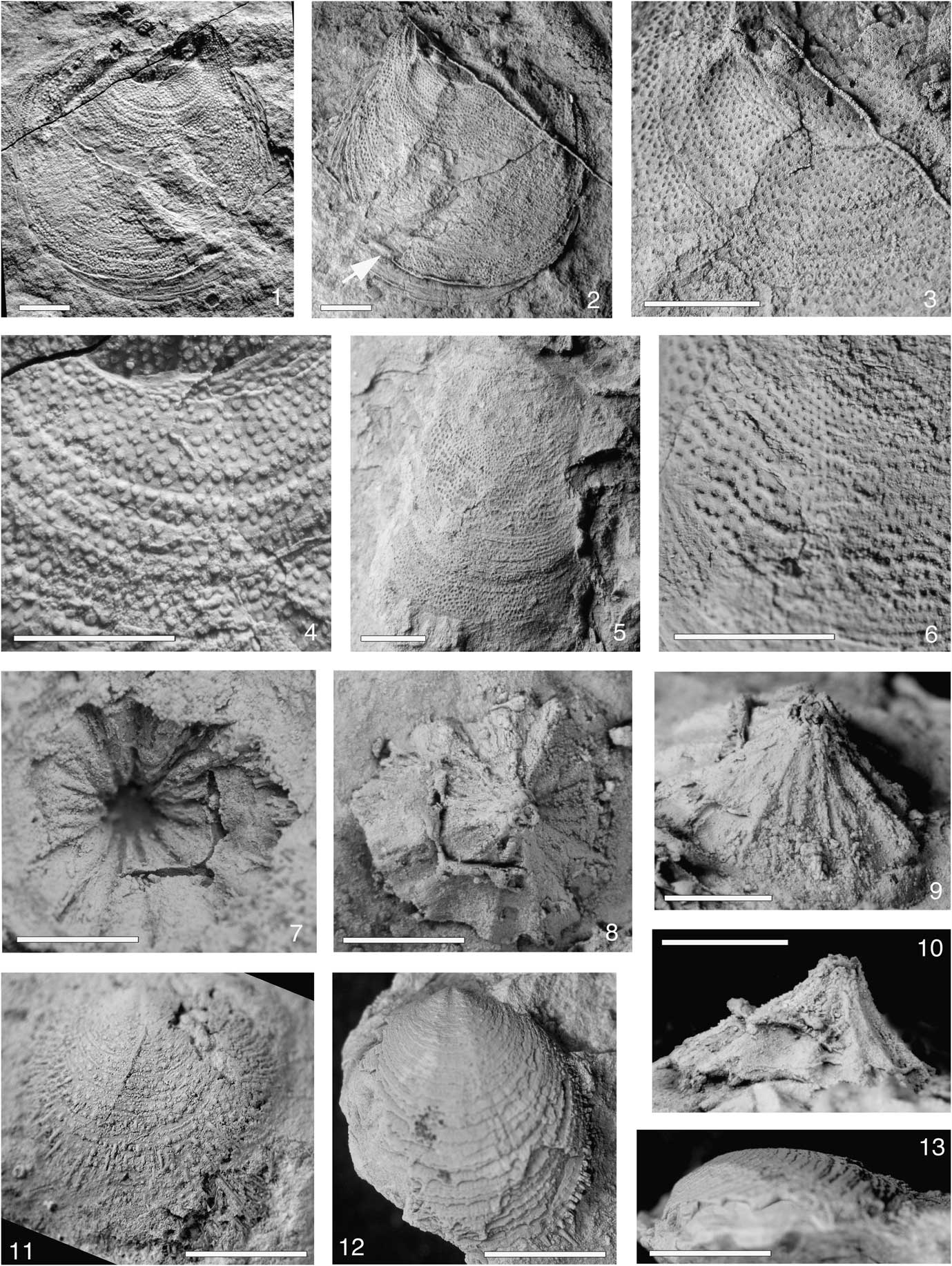

Figure 4 Trematis sp. (1–4) conjoined specimen CEGH-UNC 26920: (1) external mold of dorsal valve; (2) latex cast showing displacement of valves (arrow); (3) detail of pits, latex cast; and (4) detail of external mold showing infill of pits. (5) Incomplete dorsal valve CEGH-UNC 26931 and (6) detail of ornamentation. Craniida gen. et sp. indet. CEGH-UNC 26919 (7–10): (7) external mold of dorsal valve, (8) latex cast dorsal view, (9) latex cast posterior oblique view, and (10) latex cast lateral view. Chilcatreta tubulata Lavié and Benedetto n. gen. n. sp. (11) paratype CEGH-UNC 26947, dorsal valve; (12, 13) paratype CEGH-UNC 26946: (12) dorsal valve (13) lateral view. All scale bars represent 3 mm.

Materials

One conjoined specimen CEGH-UNC 26920 from the upper part of the San Juan Formation, Cerro Viejo (Quebrada Los Gatos), and one incomplete dorsal valve CEGH-UNC 26921 from transitional beds between the San Juan Formation and the Los Azules Formation, Sierra de Villicum (Quebrada La Pola).

Description

Dorsal valve up to 15 mm long, gently convex in the umbonal region becoming gradually planar anteriorly. Maximum convexity at ~20% of valve length from the posterior margin. Outline nearly subcircular, slightly longer than wide (length/width ratio 0.90 measured in one specimen). Ornamentation of small, rounded to suboval superficial pits ranging from 0.08 to 0.18 mm in diameter, numbering six per millimeter measured on the valve midlength, arranged in roughly quincuncial pattern, not delimited by costellae; pits increasing in size and depth toward shell margins. Pitted ornament superimposed on irregularly spaced growth lines. Dorsal interior and ventral valve unknown.

Remarks

In one of the available specimens, the valves are conjoined and slightly displaced, but details of ventral valve are not visible (Fig. 4.2). The general shell shape and outline along with the characteristic ornamentation of small rounded superficial pits lead us to refer the San Juan specimens to the widespread genus Trematis. However, because of the lack of information on internal features, the Precordillera material is left in open nomenclature. Other trematid genera such as Tethyrete Havlíček, Reference Havlíček1994, and Drabodiscina Havliček, Reference Havlíček1972, clearly differ in that pits are arranged radially instead of quincuncially, and rows are bounded by fine radial costellae and crossbars. In addition, pits in Drabodiscina are roundly subrectangular in outline. One of the most similar species is Trematis sp. from the Darriwilian of New Zealand (Percival et al., Reference Percival, Wright, Simes, Cooper and Zhen2009), which shares with the Precordilleran specimens a nearly planar, subcircular dorsal valve ornamented by pits of similar size and arrangement. Among the numerous species described from North America, our material resembles T. parva Cooper, Reference Cooper1956, (Upper Ordovician of Virginia) in size and pits arrangement, but it differs in its smaller, wider than long, elliptical shell, and shallowly sulcate dorsal valve. The type species T. terminalis (Emmons, Reference Emmons1842) can be distinguished by its more depressed and slightly elongated dorsal valve, and smaller size of pits. Conversely, T. elliptopora Cooper, Reference Cooper1956, clearly differs in having considerably larger suboval pits. Another species with quincuncually arranged pits is T. evansi Lockley and Williams, Reference Lockley and Williams1981, from the upper Darriwilian limestones of southwest Wales, which differs from the Precordilleran form in its subcircular outline, greater convexity of dorsal valve (our specimens, however, are probably compressed), and slightly finer pitting.

It is interesting that together with the record of Trematis in the early Darriwilian Antelope Valley Limestone of Nevada, USA (Popov et al., Reference Popov, Holmer, Bassett, Ghobadi Pour and Percival2013), the Precordilleran material constitutes the earliest record of trematids at global scale; its occurrence in allochthonous limestones from New Zealand is slightly younger (late Dw2-early Dw3) (Percival et al., Reference Percival, Wright, Simes, Cooper and Zhen2009). In South America, Trematis sp. had previously been reported from the Upper Ordovician Trapiche Formation of the Precordillera Basin (Benedetto and Herrera, Reference Benedetto and Herrera1987).

Order Siphonotretida Kuhn, Reference Kuhn1949

Superfamily Siphonotretoidea Kutorga, Reference Kutorga1848

Family Siphonotretidae Kutorga, Reference Kutorga1848

Genus Chilcatreta new genus

Derivation of name

After the Cerro La Chilca locality.

Type species

Chilcatreta tubulata n. sp.

Diagnosis

Shell ventribiconvex with conical ventral valve and gently convex sulcate dorsal valve. Ventral pseudointerarea high, procline. Pedicle opening small closed posteriorly by a small plate, projected internally by a long, cylindrical pedicle tube. Ornamentation of concentric rows of long hollow spines intercalated with pustules, alternating with rows formed exclusively by small pustules. Slightly enlarged median costa flanked by inconspicuous radial ribs in the apical region of ventral valve.

Remarks

Externally, the new genus Chilcatreta closely resembles Cyrbasiotreta Williams and Curry, Reference Williams and Curry1985, in having a conical ventral valve, sulcate dorsal valve, and two sizes of spines arranged along the edge of lamellae. In spite of these similarities, the Precordilleran specimens cannot be attributed to the Irish genus by having a long inner pedicle tube. In Cyrbasiotreta it is lacking, the only structure being a subcircular ridge originated by thickening of the inner margins of the pedicle opening. Moreover, although not mentioned in the diagnosis, both valves bear impersistent radial costellae (cf. Williams and Curry, Reference Williams and Curry1985, figs. 50a, 56a). Among those genera possessing a variably developed pedicle tube the new genus resembles Multispinula Rowell, Reference Rowell1962, in its pedicle track being covered by a small concave plate and the strongly lamellose ornament bearing pustules and hollow spines, but it can readily be distinguished from our material in having an elongate suboval outline, subequally biconvex shell profile, and gently convex, non-conical ventral valve. Although all these features are present in the type species Multispinula macrothyris (Cooper), in Multispinula hibernica (Reed), from the Tourmakeady Limestone of Ireland (Williams and Curry, Reference Williams and Curry1985), the shell tends to be circular in outline and the ventral pseudointerarea is relatively high for the genus. The Irish species can be viewed as a ventribiconvex variant within the genus Multispinula and it cannot be assigned to the new genus Chilcatreta by having a much larger, tear-shaped pedicle opening and shorter pedicle tube. Siphonotreta clearly differs from Chilcatreta in its almost equibiconvex shell profile, gently convex ventral valve, almost orthocline ventral pseudointerarea, and non-sulcate dorsal valve. Moreover, the ornament in Siphonotreta consists of closely spaced, evenly distributed short spines of uniform size. The scarce material referred to Siphonotreta americana Cooper, Reference Cooper1956, from the Upper Ordovician (Mohawkian) of North America, resembles externally our specimens in having a dorsal sulcus gradually widening anteriorly, a small oval pedicle foramen located anterior to the apex, and growth lamellae bearing one or two rows of spines, but clearly differs in the non-conical profile of the ventral valve (Cooper Reference Cooper1956, pl. 14, fig. 10). On the other hand, it should be noted that in the North American species there is no evidence of pedicle tube, so that its generic attribution is not conclusive. Nushbiella Popov (in Kolobova and Popov, Reference Kolobova and Popov1986) can be distinguished from Chilcatreta by its characteristic radial ornament, low conical ventral valve, and shorter pedicle tube. In Nushbiella neozelandica Percival (in Percival et al., Reference Percival, Wright, Simes, Cooper and Zhen2009) the radial ornament is poorly defined and, as in Chilcatreta, there is a slightly stronger median rib in the ventral valve. In other features, however, the New Zealand species matches with the Nushbiella diagnosis. Karnotreta clearly differs from Chilcatreta in its much smaller size, low conical ventral valve, larger subcircular pedicle track, ornament of flattened subequal spines, and short broad pedicle tube fused to the inner wall of the pseudointerarea (Williams and Curry Reference Williams and Curry1985, fig. 59). Eosiphonotreta Havlíček, 1982, resembles Chilcatreta in its long cylindrical pedicle tube but differs in its elongated oval shell outline, entirely open apical pedicle foramen, and lower apsacline to orthocline ventral pseudointerarea. In addition, Eosiphonotreta has widely spaced spines not confined to growth lamellae, and small pustules randomly covering the entire shell surface. In conclusion, the combination of a subconical ventral valve, ornamentation of long hollow spines alternating with rows of minute pustules, and the presence of a conspicuous pedicle tube justifies the proposal of a new genus.

Chilcatreta tubulata new species

Figure 5 Chilcatreta tubulata Lavié and Benedetto n. gen. n. sp. (1–3) holotype CEGH-UNC 26940: (1) exterior of dorsal valve, (2) detail of ornamentation on the marginal region, and (3) detail of ornamentation on the central region showing rows of small pustules alternating with larger hollow spines. (4–6) Paratype CEGH-UNC 26941: (4) crushed dorsal valve, (5) detail of marginal ornamentation, (6) detail of ornamentation on the central region. (7–10) Paratype CEGH-UNC 26939: (7) ventral valve anterior oblique view, (8) anterior view, (9) posterior view, and (10) lateral view. (11) Paratype CEGH-UNC 26943, dorsal valve exterior. (12–15) Paratype CEGH-UNC 26938: (12) ventral valve, (13) posterior oblique view, (14) detail of pedicle foramen, and (15) lateral view. (16–19) Paratype CEGH-UNC 26937, partly decalcified ventral valve showing pedicle tube: (16) lateral oblique view, (17) posterior oblique view, (18) ventral view, and (19) detail of pedicle tube. All scale bars represent 3 mm, except (3), (5), (6), (15), and (19), which represent 1 mm.

Etymology

Refers to the cylindrical pedicle tube.

Diagnosis

As for genus by monotypy.

Occurrence

Darriwilian, upper part of the San Juan Formation at Cerro La Chilca, San Juan Province, Precordillera of west-central Argentina.

Types

Holotype: A dorsal valve CEGH-UNC 26940 from Cerro La Chilca. Paratypes: One conjoined specimen CEGH-UNC 26944, three ventral valves and six dorsal valves CEGH-UNC 26937–26939, 26941–26943, 26945–26947 from the same levels and locality as the holotype.

Description

Shell ventribiconvex, inequivalved, nearly subcircular in outline, up to 10 mm long, with average length/width ratio=0.95. Ventral valve high conical in lateral profile, ~42% as high as long; apex slightly inclined toward posterior margin, located at ~10% of valve length from posterior margin. Ventral pseudointerarea moderately large, broadly triangular, flattened to gently convex, steeply procline, covered by strong spinose growth lamellae and divided by a faint rounded ridge. Pedicle track small, 11%–15% as long as valve, elongately oval to subtriangular in outline, located forward to apex and closed posteriorly by a subtriangular concave plate (Fig. 5.14). Dorsal valve subcircular to broadly elliptical, with small apex curved onto a poorly defined pseudointerarea. Dorsal median sulcus initially narrow, becoming broader and shallower anteriorly. Both valves ornamented by strong growth lamellae separated by smooth intervals, each bearing a row of long, tubular conical hollow spines with four to five per millimeter intercalated with one or two small rounded pustules, which also form more or less continuous concentric rows alternating with rows of larger spines (Fig. 5.3–5.6). Interior of ventral valve bearing a long cylindrical pedicle tube, suboval in cross section, with a diameter equivalent to ~10% of valve width (Fig. 5.16–5.19).

Subphylum Craniiformea Popov et al., Reference Popov, Bassett, Holmer and Laurie1993

Class Craniata Williams et al., Reference Williams, Carlson, Brunton, Holmer and Popov1996

Order Craniida Waagen, 1885

Genus and species indet.

Materials

A single dorsal valve CEGH-UNC 26919 from the uppermost levels of the San Juan Formation, Quebrada Los Gatos, Cerro Viejo, San Juan Province, Argentina.

Description

Dorsal valve high subconical, 50% as high as long, maximum width 6 mm; outline roundly subtrapezoidal, 89% as wide as long, with scalloped margin; posterior margin slightly curved, anterior margin semielliptical. Apex exocentric, located at approximately one-third of maximum valve length from posterior margin. Lateral profile with steeply inclined gently concave posterior slope, and longer nearly planar anterior slope inclined ~45° with respect to the commissural plane. Radial ornamentation of ten simple broad ribs originated at the umbo and enlarged rapidly toward the margin; posterior slope of valve with five narrower rounded ribs, two of which arising by interpolation (Fig. 4.8, 4.9), separated by interspaces of approximately equal width as ribs. Faint radial striae scarcely visible on some ribs. Internal features unknown.

Remarks

The calcareous subconical valve with holoperipheral growth, the lateral profile with steep posterior face, and the radial ornament pattern lead us to refer this single specimen to the craniids, but in absence of information on muscle scars its attribution to this order is only provisional. Although cone-shaped (limpet-like) shells are present in some groups of gastropods and in the tryblidians (=monoplacophoran) the general morphology of the San Juan shell does not fit with that of these mollusc groups. In most of Paleozoic tryblidians, for instance, the shell apex distinctly overhanging the anterior margin of aperture and the shell surface is usually ornamented by concentric lamellae comarginal with aperture.

Among the radially ornamented craniids, the Argentinean specimen shares with the encrusting genus Deliella Halamski, Reference Halamski2004, a small subconical dorsal valve, absence of spines, and presence of radial striations between ribs. However, the type species Deliella deliae Halamski, from the Devonian of Poland and Morocco, clearly differs in being finely multicostellate with numerous undulating ribs increasing in number by dichotomy. The genus Thulecrania Holmer, Popov, and Bassett, Reference Holmer, Popov and Bassett2013, from the Silurian of Gotland (Sweden), differs in the submarginal position of the apex, and in having high bladelike ribs bearing prominent solid spines originated at the intersection of ribs and growth lamellae. The Ordovician genus Philhedra Koken, Reference Koken1889, clearly differs from our material in lacking true radial ribs and by having the entire shell surface covered by long hollow spines, which in the Estonian type species P. baltica Koken, Reference Koken1889, are radially disposed (Bassett, Reference Bassett2000) but in the Precordilleran P. pauciradiata Benedetto, Reference Benedetto2015, tend to be irregularly distributed (Benedetto, Reference Benedetto2015). On balance, although the San Juan Formation shell may represent a new craniid genus, formal nomination has been withheld until additional specimens showing internal features are known. Concerning to the life habits, the single available dorsal valve has been found isolated in mudstones without connection with other benthic organisms from the same bed (mainly rhynchonelliform brachiopods and cylindric sponges), suggesting that probably it was not an epizoan form.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to I. Percical and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments and suggestions. The Centro de Investigaciones en Ciencias de la Tierra, Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), and Universidad Nacional de Córdoba provided logistical facilities. This work was supported by CONICET (grant PIP 112-201101-00803). This article is a contribution to the IGCP Project-653 “The onset of the Great Ordovician Biodiversification.”