Introduction

Many monothalamous Devonian and pre-Devonian foraminifers, which are more or less spherical and have a single, terminal, rounded aperture, are considered as members of the foraminiferal class Astrorhizata; or even as members of the class Textulariata, which more traditionally includes plurilocular agglutinated foraminifers. This similarity has even been taken to its logical extreme: the assignment of Paleozoic taxa to extant genera of Astrorhizata/Textulariata (e.g., Saccammina, Psammosphaera, Lagenammina, Thurammina, Hyperammina and Sorosphaera) (Loeblich and Tappan, Reference Loeblich and Tappan1964, Reference Loeblich and Tappan1987; Poyarkov, Reference Poyarkov1969, Reference Poyarkov1977, Reference Poyarkov1979; Ross and Ross, Reference Ross and Ross1991; Vdovenko et al., Reference Vdovenko, Rauzer-Chernousova, Reitlinger and Sabirov1993).

The parathuramminids are considered as foraminifers principally because the fossil genus Parathurammina is homeomorphous of the extant genus Thurammina (Vachard, Reference Vachard2016a). However, there are several arguments against this assignment, and other putative phyla have been proposed, to which parathuramminids may be assigned: (1) Kaźmierczak (Reference Kaźmierczak1975, Reference Kaźmierczak1976) considered this group to be related with calcisphaeraceans and radiosphaeraceans, and might be interpreted as volvocale algae; (2) Vachard (Reference Vachard1994) designated these forms as pseudoforaminifers; (3) Préat et al. (Reference Préat, Blockmans, Capette, Dumoulin and Mamet2007) included in the calcispheres the genera Calcisphaera, Parathurammina, and Vicinesphaera; (4) Versteegh et al. (Reference Versteegh, Servais, Streng, Munnecke and Vachard2009) assigned the calcisphaeraceans to the Calcitarcha, which probably, like the acritarchs, constitute a heterogeneous group that includes dinoflagellates, chlorophytes, haptophytes, foraminifers, and radiolarians; (5) Vachard and Clément (Reference Vachard and Clément1994) indicated possible morphological and paleobiological similarities between some irregularinids or usloniids with thaumatoporellacean incertae sedis algae; Schlagintweit et al. (Reference Schlagintweit, Hladil, Nose and Salerno2013) even synonymized both groups; (6) Vishnevskaya and Sedaeva (Reference Vishnevskaya and Sedaeva2002a, Reference Vishnevskaya and Sedaevab), Afanasieva and Amon (Reference Afanasieva and Amon2011), and Nestell et al. (Reference Nestell, Heredia, Mestre, Beresi and González2011) considered that these forms are radiolarians, the tests of which were calcified after diagenesis, returning to outdated assumptions about the calcispheres (Williamson, Reference Williamson1880; Pia, Reference Pia1937); (7) E. Armynot du Châtelet (personal communication, 2016) advocates a relationship with thecamoebian protozoans; this assignment has also been proposed for upper Proterozoic agglutinated, monothalamous tests of Namibia and Mongolia (Bosak et al., Reference Bosak, Lahr, Pruss, Macdonald, Dalton and Matys2011, Reference Bosak, Lahr, Pruss, Macdonald, Dalton and Matys2012); and (8) the tintinnids, which are other agglutinating protists (Tappan and Loeblich, Reference Tappan and Loeblich1968; Henjes and Assmy, Reference Henjes and Assmy2008), also display sizes and shapes corresponding to some parathuramminids.

Rich assemblages of parathuramminoids and irregularinoids discovered in our material provide: (1) a more precise systematics of these taxa, which have not been investigated for more than half a century; (2) more extensive illustrations of these poorly known taxa; (3) additional paleoecological data; and (4) an opportunity to discuss the taxonomical problems of these foraminifers, pseudoforaminifers, or algae.

Geologic setting

The Carnic Alps, which are part of the Southern Alps and form an east-west-trending mountain range along the border between southern Austria and Italy, are well known for its almost continuous and well-preserved sedimentary succession ranging in age from the Late Ordovician to the Late Permian (e.g., Schönlaub, Reference Schönlaub1979, Reference Schönlaub1980, Reference Schönlaub1985a, Reference Schönlaubb; Schönlaub and Heinisch, Reference Schönlaub and Heinhisch1993; Schönlaub and Histon, Reference Schönlaub and Histon2000). The Devonian of the Carnic Alps, which is best exposed in the Plöckenpass-Wolayersee area, is developed in different facies ranging from shallow marine environments (including carbonate buildups formed by stromatoporoids and tabulate corals and lagoonal sediments) to reef slope deposits, condensed pelagic cephalopod limestones, and deep marine offshore shales and siliceous sediments (bedded chert). The shallow marine facies is up to 1200 m thick, whereas the condensed pelagic limestone facies measures ~100 m (Schönlaub, Reference Schönlaub1979, Reference Schönlaub1985a, Reference Schönlaub1985b; Schönlaub and Heinisch, Reference Schönlaub and Heinhisch1993; Schönlaub and Histon, Reference Schönlaub and Histon2000).

The Feldkogel Limestone is part of the Devonian shallow marine facies of the Feldkogel Nappe (“northern shallow-water facies”) and is described as algal laminite with dolomite layers (Schönlaub, Reference Schönlaub1985a, Reference Schönlaub1985b; Kreutzer, Reference Kreutzer1992b). The Feldkogel Limestone is more than 330 m thick and dated as Eifelian–Late Devonian (Kreutzer, Reference Kreutzer1990).

The Gamskofel Limestone is developed in a similar facies (800 m thick bedded succession of algal laminites with intercalated Amphipora limestone beds), but is older (Pragian–Givetian?) and belongs to the “southern shallow-water facies” of the Kellerwand Nappe according to Kreutzer (Reference Kreutzer1992a).

From the Feldkogel Limestone at Mount Polinik, Kreutzer (Reference Kreutzer1992a) described the following microfacies types: (1) MF-Type 5c—bindstone (stromatolite with rare ostracodes and parathuramminids), (2) MF-Type 12—quartz-rich dolosparite and stromatolites, and (3) MF-Type 13—ostracode and Parathurammina-packstone (peloid-pack-/grainstone with parathuramminids of Kreutzer, Reference Kreutzer1992b). Kreutzer (Reference Kreutzer1992a) assigned the monolocular foraminifers to Parathurammina dagmarae Suleimanov and cf. Cribrosphaeroides sp.

Recently, Pohler et al. (Reference Pohler, Bandel, Kido, Pondrelli, Suttner, Schönlaub and Mörtl2015) introduced the term Polinik Formation, in which they included the Gamskofel Limestone and Feldkogel Limestone. These authors described the Polinik Formation as a bedded, cyclic, shallow marine succession of dominantly algal laminites and Amphipora limestone. The type locality is at Mount Polinik. The Polinik Formation is of Pragian to Frasnian, probably of younger, age; its estimated thickness is 700–800 m.

Materials and methods

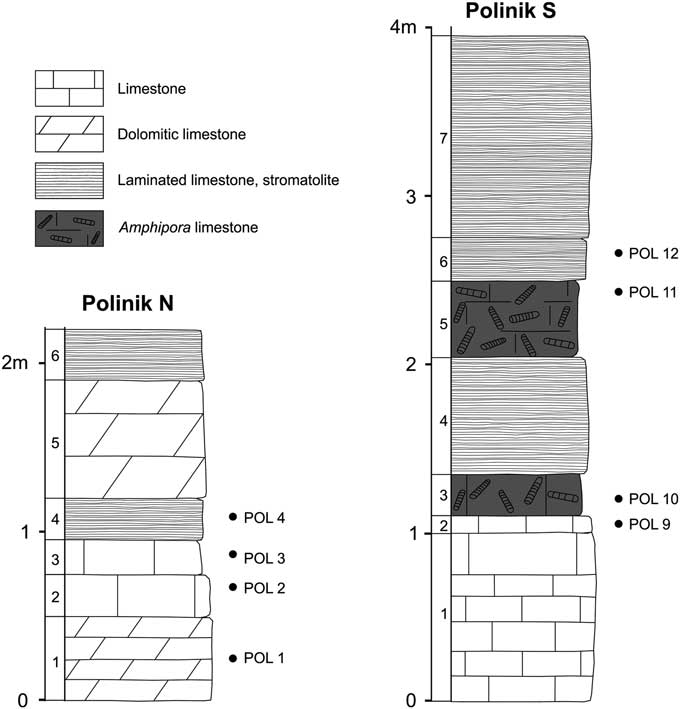

The studied samples are derived from bedded limestones of the Devonian “Feldkogel-Kalk” (Feldkogel Limestone) of the Polinik Formation exposed at the summit of Mount Polinik (2332 m) in the Carnic Alps (Figs. 1, 2), ~5 km SSW of Kötschach in the Gail Valley (Carinthia, southern Austria) (see geologic map of Schönlaub, Reference Schönlaub1985a). At the summit of Mount Polinik, we measured two short sections that characterize the facies of the Feldkogel Limestone (Figs. 2, 3). Section A is located ~10 m north of the summit cross of Mount Polinik and is 2 m thick. Section B was measured ~50 m south of the summit cross and measures ~4 m. Four samples were collected from section A and four samples from section B. Additionally, samples were collected from bedded limestones of the summit area of Mount Polinik (Fig. 2). From all samples, 16 thin sections were prepared, which were studied under the microscope in terms of microfacies and paleontology.

Figure 1 Geographical map of the studied area with location of Mount Polinik.

Figure 2 Top of Mount Polinik with locations of the two sections (Fig. 3) and the fossiliferous samples. Contour lines (2200, 2300) in meters.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

All thin sections used in this study are stored in the collection of the Institute of Geology (POL 1–POL 15), University of Innsbruck, Austria. Other repositories and abbreviations include: Geological Museum of Novosibirsk (IGiG SO AN SSSR); UTGU, Ural Geological Museum; VNIGRI, Leningrad/Sankt Petersburg.

Lithofacies

At Mount Polinik, the Feldkogel Limestone is composed of medium- to thick-bedded limestone and dolomitic limestone/dolomite. Bed thickness ranges from 20 cm to 120 cm. We observed the following lithofacies (Fig. 2): (1) dark gray massive Amphipora limestone, 20–50 cm thick; (2) well-laminated dark gray limestone that weathers light gray, with individual beds up to 120 cm thick; (3) massive to indistinctly laminated limestone and dolomite beds, 20–70 cm thick; (4) stromatolite beds, 20–50 cm thick; and (5) intraclast breccia composed of reworked, poorly sorted, angular intraclasts up to 30 cm in diameter. The intraclast breccia is rare, up to 50 cm thick, displays a channel-form geometry, and thins laterally. The base is erosive.

Microfacies

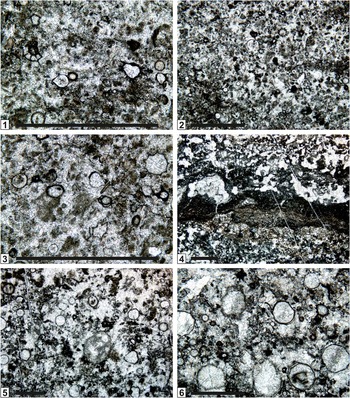

Limestones of the Feldkogel Limestone at the summit of Mount Polinik are composed of four microfacies types (Mörtl, Reference Mörtl2014; Figs. 4, 5).

Figure 4 (1) Bioclastic and pelloidal grainstone with Vasicekia? sp. (tubular specimens with clear wall), Neoarchaesphaera ellipsoidalis, Ivanovella sp., Cribrosphaeroides (Parphia) robusta, and Amphipora sp., sample POL3. (2) Bioclastic and pelloidal grainstone with Vasicekia? sp. (tubular specimens with clear wall), Neoarchaesphaera ellipsoidalis, Parathurammina sp., and Suleimanovella sp., sample POL3c. (3) Dolomitized floatstone with Amphipora sp., sample POL10a. (4) Floatstone with Amphipora cf. A. pervesiculata and parathuramminids in the matrix, sample POL11. (5) Bioclastic and pelloidal grainstone with Vasicekia sp. (tubular specimens with clear wall), Neoarchaesphaera ellipsoidalis, Parathurammina sp., and Suleimanovella sp., sample POL11-10. (6) Bioclastic and pelloidal grainstone with Uralinella sp., Parathurammina sp., Neoarchaesphaera ellipsoidalis, Suleimanovella sp., and ostracodes, sample POL11a. Scale bars=1 mm.

Figure 5 (1) Bioclastic and pelloidal grainstone with Vasicekia? sp., Uralinella sp., Radiosphaerella sp., Neoarchaesphaera ellipsoidalis, and Suleimanovella sp., sample POL11a-2. (2) Bioclastic and pelloidal grainstone with Uralinella sp., Parathurammina sp., Salpingothurammina sp., Suleimanovella sp., and ostracodes, sample POL11d. (3) Bioclastic and pelloidal grainstone with Uralinella sp., Parathurammina sp., Neoarchaesphaera ellipsoidalis, and Suleimanovella sp., sample POL11a-7. (4) Three layers of microbialites; two with parathuramminids, sample POL12b. (5) Bioclastic and pelloidal grainstone with Uralinella sp., Parathurammina sp., Bykovaella sp., Suleimanovella sp., and Amphipora sp., sample POL13a. (6) Bioclastic and pelloidal grainstone with Uralinella sp., Parathurammina sp., Bykovaella sp., Suleimanovella sp., and Vasicekia? sp., sample POL13c. Scale bars=1 mm.

(1) Amphipora floatstone to rudstone (Fig. 4.2, 4.3). Skeletons of Amphipora are embedded in a matrix of grainstone composed of abundant peloids and foraminifers. Rare skeletons of brachiopods occur. Amphipora skeletons are up to several cm in size, mostly complete, rarely fragmented. The following species are present (J. Hladil, written communication, 2014): Amphipora cf. A. angusta Lecompte, Reference Lecompte1952; A. cf. A. rudis Lecompte, Reference Lecompte1952; A. cf. A. laxeperforata Lecompte, Reference Lecompte1952; and A. cf. A. pervesiculata Lecompte, Reference Lecompte1952 (Mörtl, Reference Mörtl2014, text-fig. 31).

(2) Grainstone to packstone containing abundant peloids and foraminifers (Figs. 4.1, 4.2, 4.5, 4.6, 5.1–5.6). This microfacies is partly laminated, locally bioturbated. Locally, small amounts of micritic matrix are present. Subordinately, fragments of brachiopods, Amphipora, and ostracodes are observed (Mörtl, Reference Mörtl2014, text-fig. 32).

(3) Ostracode wackestone to packstone. This microfacies is composed of alternating densely and less densely packed ostracode layers. Ostracode shells are oriented parallel to bedding and are embedded in peloidal micrite. Many ostracodes are preserved with both valves, and the interior is filled with calcite cement (Mörtl, Reference Mörtl2014, text-fig. 29).

(4) Bindstone, composed of laminated cyanobacteria mats (microbial mats, stromatolites), alternating with thin layers containing abundant peloids and aggregate grains, rare micritic intraclasts and some fossils, such as ostracodes and foraminifers. LF-fabrics are common (Mörtl, Reference Mörtl2014, text-fig. 30).

Systematic paleontology

Subkingdom Rhizaria Cavalier-Smith, Reference Cavalier-Smith2002

Phylum Foraminifera d’Orbigny Reference d’Orbigny1826 emend. Cavalier-Smith, Reference Cavalier-Smith2003

Class Fusulinata Gaillot and Vachard, Reference Gaillot and Vachard2007 emend. Vachard, Reference Vachard2016a

Subclass Afusulinana Vachard, Pille, and Gaillot, Reference Vachard, Pille and Gaillot2010

Order Parathuramminida Mikhalevich, Reference Mikhalevich1980 emend. Vachard, Reference Vachard2016a

Diagnosis

Unilocular (= monothalamous), free to temporarily attached foraminifers showing a large central chamber. Rarely bilocular with two concentric chambers or several chambers built alongside. Apparently, no true plurilocular tests exist, but clusters of unilocular chambers can be encountered (e.g., Tschernyncevella Antropov, Reference Antropov1950; Rauserina Antropov, Reference Antropov1950; Uralinella Bykova, Reference Bykova1952; and various tuberitinoids). Wall thin (Eovolutina Antropov, Reference Antropov1950) to thick (Vicinesphaera Antropov, Reference Antropov1950), dark-microgranular, occasionally bilayered with an inner hyaline-pseudofibrous layer, rarely more differentiated. Apertures are typically emplaced at the extremity of hollow necks connecting the central chamber with the external environment; often also, the walls are finely perforated by very numerous minute foramina; or the apertures are inconspicuous. Wall thin to moderately thick, dark-microgranular, occasionally bilayered with an inner hyaline-pseudofibrous layer, rarely more differentiated (e.g., Tubesphaera Vachard, Reference Vachard1994 and some parathuramminids).

Occurrence

Questionable in the middle Cambrian, rare in the Ordovician–early Silurian, present during the late Silurian–Early Devonian, common during the Middle and Late Devonian, present in the Mississippian, rare in the Pennsylvanian–Permian (except for the tuberitinoids, which remain common during this time interval); very rare in the earliest Triassic, during which only tuberitinids locally subsist (Vachard, Reference Vachard2016a, Reference Vachard2016b, with references therein).

Remarks

Suspected to be micritized envelopes of volvocacean algae by Toomey and Mamet (Reference Toomey and Mamet1979) or acritarchs that underwent an early post-mortem calcification (Kaźmierczak and Kremer, Reference Kaźmierczak and Kremer2005), these taxa remain enigmatic; nevertheless, it seems to be possible to reconstruct their phylogeny as follows (Figs. 6, 7). First, the forms with one or two chambers and a non-perforated dark-microgranular wall (i.e., the eovolutinoids) appear. After that, the wall thickens and becomes ornamented with necks, with the ivanovellids, which can give rise, more or less coevally, to the parathuramminids, uralinellids, and tuberitinoids. Eovolutinids also give rise to the tuberitinoids, whereas the irregularinoids derive either from the eovolutinoids, ivanovellids, or parathuramminids (and in this case, “Parathurammina” mirabilis Saltovskaya, Reference Saltovskaya1981, the diameter of which is 0.80–0.85 mm, may be transitional). The order Parathuramminida encompasses four superfamilies (Vachard, Reference Vachard2016a, and this work: Figs. 6, 7): Parathuramminoidea Rauzer-Chernousova and Fursenko, Reference Rauzer-Chernousova and Fursenko1959 nomen correctum Loeblich and Tappan, Reference Loeblich and Tappan1961; Irregularinoidea Gaillot and Vachard, Reference Gaillot and Vachard2007; Tuberitinoidea Gaillot and Vachard, Reference Gaillot and Vachard2007 emend. Vachard, Reference Vachard2016a; and Calcisphaeroidea Vachard, Reference Vachard2016a.

Figure 6 Superfamilies, families, and genera of the Parathuramminida. 1: Eovolutinidae; 2: Ivanovellidae; 3: Calcisphaeroidea; 4: Tuberitinoidea; 5: Uralinellidae; 6: Parathuramminidae; 7: Parathuramminitidae.

Figure 7 Superfamilies, families, and genera of the Irregularinoidea and Caligelloidea. 8: Irregularinoidea; 9: Earlandioidea; 10: Caligelloidea. 11: Tournayellinidae.

Superfamily Parathuramminoidea Fursenko in Rauzer-Chernousova and Fursenko, Reference Rauzer-Chernousova and Fursenko1959 nomen correctum Loeblich and Tappan, Reference Loeblich and Tappan1961 (as Parathuramminacea) and Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984 (as Parathuramminidea) (non Parathuramminoidea Zadorozhnyi, Reference Zadorozhnyi1987, described as a suborder) emend. Vachard, Reference Vachard2016a.

Diagnosis

Unilocular free foraminifers. Large central chamber, spherical to polygonal. Apertures inconspicuous or absent (Eovolutinidae emend. herein, even if some intercameral connections may exist in Rauserina), perhaps blind (Ivanovellidae) or at the extremity of radiate necks connecting the central chamber with the external environment (Parathuramminidae, Parathurammininae, Parathuramminitinae, and Uralinellidae). Wall thin (e.g., Eovolutina) to thick (e.g., Vicinesphaera), dark-microgranular, occasionally bilayered with an inner hyaline-pseudofibrous layer, rarely more differentiated with possibly three layers. Apertures inconspicuous or absent, some intercameral connections may exist (e.g., Rauserina).

Occurrence

Late Silurian–Mississippian, rare to very rare in the Pennsylvanian–Permian; probably cosmopolitan.

Remarks

This superfamily is composed of four families (Fig. 6): Eovolutinidae Loeblich and Tappan, Reference Loeblich and Tappan1986 (synonym of Rauserinidae Sabirov, Reference Sabirov1987b); Ivanovellidae Chuvashov and Yuferev in Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984 emended herein; Parathuramminidae Bykova in Bykova and Polenova, Reference Bykova and Polenova1955 emend. Vachard, Reference Vachard1994; and Uralinellidae Chuvashov, Yuferev, and Zadorozhnyi in Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984.

Family Eovolutinidae Loeblich and Tappan, Reference Loeblich and Tappan1986 emend. herein

Diagnosis

Small parathuramminoids, with a proportionally broad central, spherical chamber. Apertures inconspicuous or absent. Wall thin to moderately thick, dark-microgranular.

Occurrence

Questionable in the middle Cambrian, rare in the Ordovician–early Silurian (Vachard, Reference Vachard2016a), present during the late Silurian–Mississippian, rare to very rare in the Pennsylvanian–Permian.

Remarks

Eovolutinidae (= Rauserinidae) emend. herein encompasses the eovolutinins (with two concentric chambers), rauserinins (with clusters of unilocular chambers), and vicinesphaerins (strictly unilocular) (e.g., the genera Eovolutina Antropov, Reference Antropov1950; Rauserina Antropov, Reference Antropov1950; Vicinesphaera Antropov, Reference Antropov1950; Archaesphaera Suleimanov, Reference Suleimanov1945 [partim]; Serginella Pronina, Reference Pronina1963; Paralagena Sabirov, Reference Sabirov1986; and ?Tscherdyncevella Antropov, Reference Antropov1950). They are the most primitive parathuramminids due to the presence, among them, of Vicinesphaera Antropov, Reference Antropov1950 as early as in the Cambrian of Kazakhstan and the Early Ordovician of Mexico (Vachard et al., Reference Vachard, Clausen, Palafox, Buitrón, Devaere, Hayart and Régnier2017). The family Eovolutinidae is often confused with the Archaesphaeridae Poyarkov, Reference Poyarkov1979 auctorum, which could therefore have priority; nevertheless, it is more probable that Archaesphaera Suleimanov, Reference Suleimanov1945 is a transverse section of Eotuberitina Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1958, and therefore is a tuberitinoid rather than a parathuramminoid. However, true Eotuberitina seem to appear in Upper Devonian deposits, and an “Archaesphaera”, such as that of Flügel and Hötzl (Reference Flügel and Hötzl1971, fig. 1.1, 1.2), belongs to another taxon, which are either oblique sections of Eovolutina cutting only the external chamber, or oblique sections of Ivanovella, which do not pass by the external spines.

Family Ivanovellidae Chuvashov and Yuferev in Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984

Diagnosis

Small- to moderate-sized unilocular tests with spherical to polygonal central chamber. Radiate to irregularly arranged protuberances of the wall; either unperforated or when possessing a central neck, the latter does not communicate with the external environment. Inconspicuous apertures. Wall dark-microgranular.

Occurrence

Early Ordovician to Late Devonian in Laurussia, Siberia and eastern Paleotethys (Tian Shan and South China).

Remarks

The Ivanovellidae are partly synonymous with Psammosphaeridae sensu Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1965 (non Haeckel, Reference Haeckel1894, nec Cushman, Reference Cushman1927). They are composed of Ivanovella Pronina, Reference Pronina1969; Lechangsphaera Lin, Reference Lin1984; Neoivanovella Chuvashov and Yuferev in Dubatolov, Reference Chuvashov and Yuferev1981; Neoarchaesphaera Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1963 (non 1958); Elenella Pronina, Reference Pronina1969; ?Ratella Kotlyar, Reference Kotlyar1982; and ?Turcmeniella Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1965. The mazzuelloid microproblematica are probably recrystallized (phosphatized) ivanovellids. Mazzuelloids were interpreted as microfossils with an original phosphatized wall (Kozur, Reference Kozur1984), but a secondary phosphatization is more probable (Hüsken and Eiserhardt, Reference Hüsken and Eiserhardt1997; Kremer, Reference Kremer2005; and general discussion of the problems of phosphatization in Porter, Reference Porter2004 and Zhuralev and Wood, Reference Zhuravlev and Wood2008). Hüsken and Eiserhardt (Reference Hüsken and Eiserhardt1997) advocated for a phosphatization of the organic wall of acritarchs, but it seems that their illustrations (pl. 1, fig. 15, pl. 2, figs. 1–4) most probably correspond to secondarily phosphatized ivanovellids (perhaps Neoarchaesphaera spp.). The material illustrated by Kremer (Reference Kremer2005) seems also to belong to Neoarchaesphaera. Moreover, because the mazzuelloids are known from Late Ordovician to Early Devonian, they have a stratigraphic distribution similar to that of the ivanovellids.

Genus Ivanovella Pronina, Reference Pronina1969

Type species

Ivanovella isensis Pronina, Reference Pronina1969.

Other species

See Chuvashov and Yuferev in Dubatolov (Reference Chuvashov and Yuferev1981) and Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev in Dubatolov (Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1981).

Diagnosis

Test unilocular, with spherical central chamber and radiate necks, prominent at the periphery and not communicating with the external environment. Inconspicuous apertures. Wall dark-microgranular.

Occurrence

Ludlovian–Pridolian of the central and northern Urals. Late Emsian of Gornyi Altai. Middle Devonian–Frasnian of the Tomsk area (SW Siberia). Late Emsian–Frasnian of southwestern Siberia (the Famennian age indicated by Vdovenko et al., Reference Vdovenko, Rauzer-Chernousova, Reitlinger and Sabirov1993, p. 29, is possibly due to a lapsus calami). Discovered in the Givetian of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Ivanovella sp. 1

Diagnosis

The test is small; the chamber is subhexagonal; the necks are short and subtriangular.

Occurrence

Only one sample in the Givetian of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Description

Outer diameter=0.08 mm; inner diameter=0.04 mm; test wall thickness=0.01 mm.

Diagnosis

The test consists of an irregularly polygonal chamber; the necks are long, thin and triangular.

Occurrence

Only one sample in the Givetian Feldkogel Limestone of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Description

Outer diameter=0.13 mm; inner diameter=0.08 mm; test wall thickness=0.005 mm.

Diagnosis

The test consists of a polygonal chamber with a thick wall; the necks are long, triangular to thin and occasionally curved.

Occurrence

Rare in the Givetian Feldkogel Limestone of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Description

Outer diameter=0.26 mm; inner diameter=0.12 mm; test wall thickness=0.03 mm.

Materials

Three specimens (sample POL11-5).

Ivanovella reitlingerae new species

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:11BF6627-39AF-4F5C-8C30-48A3841DC9DB

1965 Parathurammina cf. spinosa Lipina; Reference Ferrari and VaiFerrari and Vai, text-fig. 2e.

1971 Parathurammina aperturata Pronina; Reference Menner and ReitlingerMenner and Reitlinger, p. 29, pl. 8, figs. 2, 7–9.

Holotype

Fig. 10.16 (sample POL11a-38); Institute of Geology, University of Innsbruck, Cat. Nr. P 10139-POL 11a (thin section); early Givetian of Feldkogel Limestone, Polinik Formation, Mount Polinik (Austria).

Diagnosis

An Ivanovella with a central chamber subtrapezoidal to subhexagonal, and numerous thin cylindrical necks.

Occurrence

Givetian of Norilsk region (NW Siberia). ?Frasnian of northern Italy. Discovered in the Givetian Feldkogel Limestone of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Description

Outer diameter=0.21–0.23 mm; inner diameter=0.12–0.14 mm; test wall thickness=0.003–0.005 mm; neck diameter (nd)=0.01–0.02 mm.

Etymology

Named in honor of E.A. Reitlinger who illustrated the taxon.

Materials

A dozen specimens (samples POL11a-23, POL11a-38, and POL11a-40).

Remarks

Differs from Parathurammina aperturata by the unilayered wall, the polygonal central chamber, and longer necks; and from the other Ivanovella by thinner wall and necks, and more regularly arranged around the central chamber.

Ivanovella luginensis Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev in Dubatolov, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1981

1981 Ivanovella luginensis Reference Zadorozhnyi and YuferevZadorozhnyi and Yuferev in Dubatolov, p. 56, pl. 1, figs. 5, 9, 10.

1984 Ivanovella luginensis; Reference Zadorozhnyi and YuferevZadorozhnyi and Yuferev, p. 99, pl. 3, figs. 12, 13.

1988 Ivanovella luginensis; Reference Bogush, Zarodozhnyi and IvanovaBogush et al., p. 18.

1990 Ivanovella lunginensis (sic); Reference Bogush and YuferevBogush and Yuferev, p. 22.

Holotype

Axial section (No. 576/8, IGiG SO AN SSSR) from the Frasnian of the oblast of Tomsk, SW Siberia, Russia (Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev in Dubatolov, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1981, pl. 1, fig. 5).

Diagnosis

Small species characterized by numerous necks, irregularly arranged. Necks short to fairly long. Wall relatively thick.

Occurrence

Late Emsian of Altai, and Frasnian of Tomsk area (SW Siberia, Russia). Discovered in the Givetian of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Description

Outer diameter=0.12–0.15 mm (the type material is even smaller: 0.08–0.13 mm); number of necks: 6–15; length of necks=0.03–0.05 mm (with a wall from 0.005 to 0.01 mm); test wall thickness=0.02–0.03 mm.

Materials

25 specimens (samples POL11a–9a, POL11b–18a, and POL11b–21b).

Ivanovella sp. 4

1994 Parathurammina stellata Lipina; Reference VachardVachard, pl. 2, fig. 8 (only).

Diagnosis

Moderate-size species characterized by few abundant necks, irregularly arranged and short to moderate. Wall relatively thin.

Occurrence

Frasnian of western France. Rare in the Givetian of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Description

Outer diameter=0.17 mm; inner diameter=0.09 mm; number of necks: six; length of necks=0.05–0.06 mm; test wall thickness=0.01–0.02 mm.

Materials

Three specimens (sample POL11a-8).

Genus Neoarchaesphaera Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1963 (non 1958)

Type species

Neoarchaesphaera bykovae Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1965 (= Archaesphaera magna sensu Bykova in Bykova and Polenova, Reference Bykova and Polenova1955 non Suleimanov, Reference Suleimanov1945=Neoarchaesphaera magna Miklukho-Maklay sensu Loeblich and Tappan, Reference Loeblich and Tappan1987).

Other species

See Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev in Dubatolov (Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1981).

Diagnosis

Small-sized Ivanovellidae with an irregular angular-rounded to spherical profile. Central chamber spherical, relatively broad. Fairly abundant papilliform to longer protuberances, as radiate necks, prominent at the periphery and not communicating with the central chamber. Inconspicuous apertures. Wall dark-microgranular.

Occurrence

Early Ordovician of Sonora (Mexico; Vachard et al., Reference Vachard, Clausen, Palafox, Buitrón, Devaere, Hayart and Régnier2017). Silurian of the Urals and Poland. Late Emsian of Gornyi Altai. Late Silurian–Early Devonian Zeravshano-Gissar (Saltovskaya, Reference Saltovskaya1981 as Parathurammina [partim]). Relatively frequent and probably widespread during the Devonian (with e.g., Parathurammina sensu Malakhova, Reference Malakhova1969, pl. 48, figs. 330, 331, pl. 49, fig. 337); Parathurammina? sensu Racki and Soboń-Podgórska (Reference Racki and Soboń-Podgórska1993, text-fig. 9a–c); and “Thurammina without marked projections” sensu Holcová and Slavík (Reference Holcová and Slavík2013, text-fig. 3). Late Devonian of the Urals and western Siberia (Russia) Kok Shaal and Tian Shan (Kyrgyzstan), and southern Fergana (Uzbekistan).

Description

See discussions in Loeblich and Tappan (Reference Loeblich and Tappan1987) and Vdovenko et al. (Reference Vdovenko, Rauzer-Chernousova, Reitlinger and Sabirov1993). Parathurammina spinosa sensu Grozdilova and Lebedeva (Reference Grozdilova and Lebedeva1954, pl. 2, fig. 3) is a Neoarchaesphaera, whereas other specimens figured by Grozdilova and Lebedeva (Reference Grozdilova and Lebedeva1954, pl. 2, figs. 1, 2) belong to Salpingothurammina.

Remarks

In the literature, Neoarchaesphaera has been described under the names Parathurammina (partim); Archaesphaera (partim), Salpingothurammina auctorum, and Calcispheric structure sensu Kaźmierczak and Kremer (Reference Kaźmierczak and Kremer2005, figs. 6B, 7B, C).

Neoarchaesphaera ellipsoidalis (Poyarkov, Reference Poyarkov1969)

1969 Parathurammina (Salpingothurammina) ellipsoidalis Reference PoyarkovPoyarkov, p. 89, pl. 1, fig. 9.

1971 Parathurammina ellipsoidalis; Reference Menner and ReitlingerMenner and Reitlinger, p. 29, pl. 8, figs. 1, 3, 6.

1979 Parathurammina (Salpingothurammina) ellipsoidalis; Reference PoyarkovPoyarkov, text-fig. 14.

1981 Parathurammina (Salpingothurammina) ellipsoidalis; Reference PetrovaPetrova, pl. 6, fig. 10.

1981 Parathurammina ellipsoidalis; Reference ZadorozhnyiZadorozhnyi, p. 111 (no. 21 of the table).

1990 Bykovaella ellipsoidalis (Poyarkov); Reference Bogush and YuferevBogush and Yuferev, p. 20.

2008 Parathurammina elipsoidales (sic); Reference AnfimovAnfimov, p. 78.

Holotype

Axial section (No. 225/70; Akademiya Nauk SSSR) from the Givetian of Fergana, Turkmenistan (Poyarkov, Reference Poyarkov1969, pl. 1, fig. 9).

Diagnosis

Small species characterized by numerous necks, irregularly arranged, short to moderate. Wall relatively thin.

Occurrence

Eifelian of the northern Urals; Givetian of Norilsk area (NW Siberia); Givetian–Frasnian of southern Fergana (Uzbekistan); Givetian of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Description

Outer diameter=0.22–0.30 mm (type material: 0.23–0.30 mm); number of necks: 10–14; length of necks=0.17–0.22 mm (with a wall of 0.015–0.045 mm); test wall thickness=0.01–0.03 mm.

Diagnosis

Small species characterized by numerous necks, irregularly arranged and short to moderate. Wall relatively thin, dark-microgranular; a very thick fibrous inner layer is present, but seems to be more diagenetic than eogenetic. The specimen is questionably assigned to Neoarchaesphaera.

Occurrence

Givetian of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Description

Outer diameter=0.13 mm; inner diameter=0.15 mm; number of necks: 6–9; length of necks=0.025 mm (with a wall of 0.008 mm); test wall thickness=0.006 mm. The ontogenetic wall is dark-microgranular; a very thick fibrous inner layer is present, but seems more diagenetic than eogenetic. The specimen is questionably assigned to Neoarchaesphaera.

Type species

Neoarchaesphaera (Elenella) multispinosa Pronina, Reference Pronina1969.

Other species

See Vachard (Reference Vachard1991).

Diagnosis

Small-sized Ivanovellidae with a spherical central chamber, relatively broad. Fairly abundant papilliform to longer protuberances, as radiate necks (or trabecules), prominent at the periphery and not communicating with the central chamber. Inconspicuous apertures. Wall dark-microgranular in the protuberances and grayish in the spaces between the protuberances.

Occurrence

Ludlovian–Pridolian of the Urals (Petrova and Pronina, Reference Petrova and Pronina1980), and late Emsian of northern Spain (Vachard, Reference Vachard1991).

Remarks

Assigned to “algal spore cysts” by Toomey and Mamet (Reference Toomey and Mamet1979), considered as a foraminifer in the Russian literature and by Loeblich and Tappan (Reference Loeblich and Tappan1987) and Vachard (Reference Vachard1991), this genus remains poorly known. In the literature, it corresponds partially to some Archaesphaera and Neoarchaesphaera.

Elenella cf. E. losvica (Petrova, Reference Petrova1981)

Figure 8.5, 8.6, 8.9, 8.15, 8.35

Figure 8 (1–3, 10, 11, 14, 25) Uralinella antiqua Petrova, Reference Petrova1981: (1) sample POL11-11; (2) sample POL11a-1; (3) sample POL11a-28; (10) sample POL11a-27; (11) sample POL11a-27; (14) sample POL11b-16; (25) sample POL 13b-3. (4?, 7, 8, 13, 16, 18?, 24?) Uralinella sabirovi n. sp.: (4) paratype?, sample POL11a-26; (7) paratype, sample POL11a-5; (8) holotype, sample POL11a-3; (13) paratype, sample POL11b-19c; (16) paratype, sample POL11b-23; (18) paratype?, sample POL13a-2; (24) paratype?, sample POL13b-8. (5, 6, 9, 15, 35) Elenella cf. E. losvica (Petrova, Reference Petrova1981); (5) sample POL11-8; (6) sample POL11a-26a; (9) sample POL11a-14a; (15) sample POL11b-19c; (35) sample POL14-6a. (12?, 17, 19, 20, 21?, 22, 27, 28) Elenella polinikensis n. sp.; (12?) paratype?, sample POL11b-14; (17) paratype, sample POL13a-1a; (18) paratype, sample POL13a-2; (19) paratype, sample POL13a-3; (20) holotype, sample POL13b-4; (21?) paratype?, sample POL 13a-5a (see also the morphotaxon Ratella); (22) paratype, sample POL13a-5; (27) sample POL13b-6; (28) paratype, POL13b-11. (23) Elenella sp. 3, sample POL14-9. (26) Paracaligella ex gr. antropovi Lipina, Reference Lipina1955, sample POL11b-14a. (29) Bithurammina? sp., sample POL14-7. (30) Auroria cf. A. singularis Poyarkov, Reference Poyarkov1969, sample POL14-17. (31) Auroria cf. A. triangularis Saltovskaya, Reference Saltovskaya1981, sample POL13a-4. (32, 33) Cribrosphaeroides (Parphia) robusta Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1965; (32) sample POL13a-1; (33) sample POL13b-1. (34) Uslonia cf. U. incomposita (Petrova, Reference Petrova1981), sample POL13b-12. (36) Auroria? sp. Givetian of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria); sample POL14-8. Scale bars=0.1 mm.

1981 Parathurammina? losvica Reference PetrovaPetrova, p. 89, pl. 7, figs. 13, 14, 16, 17.

1984 Uralinella lozvica (sic); Reference Zadorozhnyi and YuferevZadorozhnyi and Yuferev, p. 97, pl. 3, figs. 3–5.

1987 Uralinella losvica; Reference ZadorozhnyiZadorozhnyi, pl. 2, figs. 21–23.

1988 Uralinella lozvica (sic); Reference Bogush, Zarodozhnyi and IvanovaBogush et al., p. 32.

1990 Uralinella losvica; Reference Bogush and YuferevBogush and Yuferev, p. 22.

2008 Parathurammina lozvica; Reference AnfimovAnfimov, p. 78.

2013 Saltovskajina lozvica; Reference Makarenko and SavinaMakarenko and Savina, p. 128.

2016a Ellenella spp.; Reference VachardVachard, fig. 3.5, 3.6, 3.9, 3.15, 3.35.

Holotype

Axial section (No. 23/1868, UTGU) from the Eifelian of the northern Urals, Russia (Petrova, Reference Petrova1981, pl. 7, fig. 13).

Diagnosis

Small species for the genus, characterized by a moderate number of necks, a relatively broad inner spherical chamber and a polygonal external chamber.

Occurrence

Eifelian–Givetian of the western slope of the middle and northern Urals. Eifelian of the Tomsk area (SW Siberia). Givetian–Frasnian of the southeastern part of the western Siberian Plain. Discovered in the early Givetian of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Description

Outer diameter=0.18–0.21 mm; inner diameter=0.06–0.10 mm; number of necks: (3)–6–8; test wall thickness(s)=0.02–0.05 mm.

Remarks

As for E. losvica, the taxon shares a wall of uralinellid with a shape of parathuramminid; our material slightly differs from E. losvica by the less acute shape of protuberances. As indicated by our synonymy list, the genus assignment and the species spelling vary in the literature.

Materials

20 specimens (samples POL11-8, POL11a-14a, POL11b-19c, POL11a-26a, and POL14-6a).

Elenella polinikensis new species

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:D33F76C5-55F5-4B65-878D-3DD160BCB135

Figure 8.12?, 8.17–8.20, 8.21?, 8.22, 8.27, 8.28

2014 Parathuramminide; Reference MörtlMörtl, text-figs. 33e, 33g.

2016a Uralinellla spp.; Reference VachardVachard, fig. 3.12, 3.17–3.20, 3.21, 3.22, 3.27, 3.28.

Holotype

Fig. 8.20 (sample POL13a–4); Institute of Geology, University of Innsbruck, Cat. Nr. P 10141-POL 13a (thin section); early Givetian of Feldkogel Limestone (Polinik Formation); Mount Polinik (Austria).

Diagnosis

Elenella relatively large, spherical, but generally periphically poorly preserved. Central chamber subpolygonal with thick dark-microgranular wall. Necks more regular and thinner than the wall. Peripheral thin, dark-microgranular wall. Intermediary wall grayish recrystallized/filled by microsparite.

Occurrence

Givetian of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Description

Outer diameter=0.16–0.36 mm; inner diameter=0.08–0.17 mm; inner chamber wall thickness=0.01–0.03 mm; outer chamber wall thickness=0.06–0.08 mm; number of necks: 8–14 (their width is 0.01–0.02 mm).

Etymology

After Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Remarks

Similar to the upper Emsian species E. monielli Vachard, Reference Vachard1991, the new species differs by a larger central chamber with a thicker wall, and fewer necks/trabecules within the wall.

Materials

25 specimens (samples ?POL11b-14, POL13a-1a, POL13a-2, POL13a-3, POL13a-5, ?POL13a-5a, POL13b-4, POL13b-6, and POL13b-11).

Elenella sp. 3

Diagnosis

The test is composed of two almost spherical, concentric chambers; the necks are long, thin and occasionally curved.

Occurrence

Givetian of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Materials

Only one specimen (sample POL14-9).

Family Uralinellidae Chuvashov, Yuferev and Zadorozhnyi in Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984

Diagnosis

Test bilocular, probably attached, at least temporarily. Inner chamber spherical, central or excentered. Outer chamber, larger, polygonal to ellipsoidal or subspherical. Radiate necks crossing through the space between the two chambers and often prominent at the periphery. Aperture inconspicuous or single at the extremity of each neck. Wall dark-microgranular, although this interpretation is often discussed.

Occurrence

Late Silurian (Ludlovian)–latest Viséan of western and central Europe, former USSR (the Urals, Preural, eastern Russian Platform, western Siberia, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan), up to early Tournaisian in South China, Vietnam, and Australia.

Remarks

The family Uralinellidae encompasses the following taxa: Uralinella Bykova, Reference Bykova1952; radiospherid calcispheres forms A and C sensu Veevers (Reference Veevers1970, pl. 46, figs. 1–3, pl. 47, figs. 1–5); Sogdanina Saltovskaya, 1974; Arakavaella Pronina, Reference Pronina1963; Maclayina Saltovskaya, Reference Saltovskaya1981; ?Ivdelina Malakhova, Reference Malakhova1963 (= “well-preserved radiosphaerid calcispheres” sensu Berkyova and Munnecke, Reference Berkyova and Munnecke2010, fig. 3A–D, 3F–I); ?Radiina Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1957; and ?Algaeformis Anfimov, Reference Anfimov2012. Contrary to Vachard (Reference Vachard1994), we consider that the latest Viséan genus Sogdanina is not synonymous with the Devonian genus Uralinella because its intermediary layer of the wall is entirely calcified (see for example Sogdanina sp. illustrated by Sanz-Lopez et al., Reference Sanz-Lopez, Vachard and Perret2005, pl. 6, fig. 9, under the name of Uralinella cf. U. augusta Sabirov). Ivdelina and “well-preserved radiosphaerid calcispheres” (sensu Berkyova and Munnecke, Reference Berkyova and Munnecke2010, p. 588) belong either to the Uralinellidae or to the Tuberitinidae. The genus Algaeformis, initially assigned to the Uralinellidae, more probably belongs to the Auroriidae as redefined herein, as well as the genus Radiina.

Genus Uralinella Bykova, Reference Bykova1952

Type species

Uralinella bicamerata Bykova, Reference Bykova1952.

Other species

See Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev (Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984) and Vachard (Reference Vachard1994).

Diagnosis

Uralinellidae with a well-developed, polygonal to subspherical outer chamber. Radiate necks crossing through the space between the two chambers, and markedly prominent at the periphery. Aperture single at the extremity of each neck. Wall dark-microgranular, apparently formed by an inner layer around the inner chamber, and an outer layer at the periphery. Calcified wall of the necks and hollow intermediary spaces secondarily filled by neosparite.

Occurrence

Early Devonian of Tajikistan. Late Devonian of northern Spain. Middle Devonian of the northern and central Urals, western Siberia, Zeravchan Gissar and Turkestan ranges (Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan). Givetian of western France and Morocco. Late Devonian of Molotov area, Bashkorotostan, Tatarstan, Urals, and SW Siberia (Russia), Moravia (Czech Republic), and Belgium. Latest Famennian–early Tournaisian of Greece (Vachard and Clément, Reference Vachard and Clément1994), central Urals (Chuvashov, Reference Chuvashov1965), Tian Shan (Poyarkov, Reference Poyarkov1969), South China (Wang, Reference Wang1987), Vietnam (Doan in Tong et al., Reference Tong, Dang, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Ta, Pham and Doan1988) and Australia (Veevers, Reference Veevers1970; Stephens and Sumner, Reference Stephens and Sumner2003).

Uralinella antiqua Petrova, Reference Petrova1981

Figure 8.1–8.3, 8.10, 8.11, 8.14, 8.25

1981 Uralinella antiqua Reference PetrovaPetrova, p. 93, pl. 11, figs. 15–18.

1984 Uralinella antiqua; Reference SabirovSabirov, pl. 2, fig. 6.

1984 Uralinella antiqua; Reference Zadorozhnyi and YuferevZadorozhnyi and Yuferev, p. 97, pl. 3, figs. 6–8.

1985 Uralinella antiqua; Reference ZadorozhnyiZadorozhnyi, pl. 17, fig. 15.

1987 Uralinella antiqua; Reference ZadorozhnyiZadorozhnyi, p. 34, pl. 3, figs. 1, 2.

1988 Uralinella antiqua; Reference Bogush, Zarodozhnyi and IvanovaBogush et al., p. 32.

1990 Uralinella antiqua; Reference Bogush and YuferevBogush and Yuferev, p. 21.

2008 Uralinella antiqua; Reference AnfimovAnfimov, p. 78.

2008 Uralinella antique (sic); Reference TsygankoTsyganko, p. 71, text-fig. 3.

2008 Uranovella antique (sic); Reference TsygankoTsyganko, p. 73.

2013 Uralinella antiqua; Reference Makarenko and SavinaMakarenko and Savina, p. 128.

Holotype

Axial section (No. 92/1868, UTGU) from the Middle Devonian of the northern Urals, Russia (Petrova, Reference Petrova1981, pl. 11, fig. 17).

Diagnosis

Small species for the genus, characterized by a relatively broad inner spherical chamber, a relatively small external polygonal chamber, and a few necks.

Occurrence

Early Devonian of Tajikistan and western Siberia. Eifelian of Tomsk area (SW Siberia). Middle Devonian of the northern and central Urals. Frasnian of SW Siberia. Discovered in the Givetian of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Description

Test outer diameter=0.09–0.18 mm (0.09–0.12 mm; rarely 0.18–0.20 mm for the type material); test inner diameter=0.05–0.12 mm (0.05–0.09 mm for the type material); number of necks: 3–6 (4–5 for the type material); inner diameter of necks=0.005–0.008 mm; test wall thickness=0.005–0.001 mm (0.008–0.013 mm for the type material).

Materials

24 specimens (samples POL11-11, POL11-13, POL11a-1, POL11a-27, POL11a-27a, POL11a-28, POL11b-16. 25, and POL13b-3).

Uralinella sabirovi new species

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:48FFF09A-8C87-4A98-8245-131F8158126C

Figure 8.4?, 8.7, 8.8, 8.13, 8.16, 8.18?, 8.24?

2016a Uralinella spp.; Reference VachardVachard, fig. 3.4?, 3.7, 3.8, 3.13, 3.16, 3.18?, 3.24?.

Holotype

Fig. 10.8 (sample POL11a–3); Institute of Geology, University of Innsbruck, Cat. Nr. P 10139-POL 11a (thin section); Givetian of the Feldkogel Limestone (Polinik Formation); Mount Polinik (Austria).

Diagnosis

This species of Uralinella is characterized by the greater number of canals; small size; thin wall, and a festooned profile of the second chamber.

Occurrence

Givetian of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Description

Outer chamber=0.12–0.23 mm; inner chamber=0.06–0.10 mm; number of canals: 9–12, mainly 10; test wall thickness=0.005–0.006 mm, rarely 0.01 mm.

Etymology

Named in honor of A.A. Sabirov, for his contributions to parathuramminid micropaleontology.

Materials

10 specimens (samples POL11a-3, POL11a-5, ?POL11a-26, POL11b-19c, POL11b-23, ?POL13a-2, and ?POL13b-8).

Remarks

Differs from U. antiqua by the greater number of canals, and from U. bicamerata and U. parva Sabirov, Reference Sabirov1974 by a smaller size, more canals, and a festooned profile of the second chamber.

Family Parathuramminidae Bykova in Bykova and Polenova, Reference Bykova and Polenova1955 emend. Vachard, Reference Vachard1994

Diagnosis

Test free or rarely atttached, unilocular with a globular to polygonal chamber with rare to abundant tubular, mamillate, or subconical projections variously arranged and developed; wall dark-microgranular, occasionally with an inner pseudofibrous layer, or recrystallized and in this case mimicing the agglutinated wall of the homeomorphous Thurammininae. Aperture at the end of the projections, on the surface, or inconspicuous.

Occurrence

?Early Cambrian of Russia (Winchester-Seeto and McIlroy, Reference Winchester-Seeto and McIlroy2006; as Thurammina? sp.); Ordovician–Mississippian; probably cosmopolitan at least during their acme during the Givetian–Frasnian. The last, Mississippian, well-represented genus is Hemithurammina Mamet, Reference Mamet1973 (see Perret and Vachard, Reference Perret and Vachard1977); in younger strata, the parathuramminids are very rare and doubtful (Nguyên, Reference Nguyên1986, pl. 1, fig. 15).

Remarks

Parathuramminidae is synonymous with Thurammininae Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1963 (partim); Chrysothuramminidae Loeblich and Tappan, Reference Loeblich and Tappan1986; and Dagmarellinae Chuvashov, Yuferev, and Zadorozhnyi in Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984, which is a nomen nudum because Dagmarella is an invalid genus. Parathuramminidae includes two subfamilies: Parathurammininae Bykova in Bykova and Polenova, Reference Bykova and Polenova1955 emend. Vachard, Reference Vachard1994; and Parathuramminitinae Antropov, Reference Antropov1970. The collective morphogenus Parathurammina Suleimanov, Reference Suleimanov1945 was progressively subdivided into numerous genera or subgenera: Salpingothurammina Poyarkov in Purkin et al., Reference Purkin, Poyarkov and Rozhanets1961; Parathuramminites Antropov in Poyarkov, Reference Poyarkov1969; Chrysothurammina Neumann, Pozaryska, and Vachard, Reference Neumann, Pozaryska and Vachard1975; Saltovskajina Sabirov, Reference Sabirov1982b; Cordatella Petrova in Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984; Marginara Petrova in Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984 (nomen correctum Loeblich and Tappan, Reference Loeblich and Tappan1986 for Margarinarae, incorrect name because in the plural); Suleimanovella Yuferev in Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984; Cushmanella Zadorozhnyi in Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984 (pre-occupied); Bykovaella Zadorozhnyi in Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984; Radiosphaerella Yuferev in Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984; Kolongella Zadorozhnyi in Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984; and Polygonella Zadorozhnyi in Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984.

All these taxa were considered to be homeomorphs of the extant agglutinating genus Thurammina Brady, Reference Brady1879, which is, however, undoubtedly known only from Jurassic deposits (e.g., Häusler, Reference Häusler1883; Kaźmierczak, Reference Kaźmierczak1973; Munk, Reference Munk1994; Guilbault et al., Reference Guilbault, Krautter, Conway and Vaughn Barrie2006; Reolid et al., Reference Reolid, Nagy, Rodríguez-Tovar and Olóriz2008; Reolid and Molina, Reference Reolid and Molina2010). Parathurammina sensu stricto is one of these Devonian foraminiferal genera, which shows a dark-microgranular wall in shallow water, transformed into an agglutinating and/or recrystallized wall in deeper waters (Vachard et al., Reference Vachard, Pille and Gaillot2010; Vachard, Reference Vachard2016a). The name Parathurammina is therefore entirely appropriate to replace the Paleozoic Thurammina of the literature. Similarly, other names could be given to the Paleozoic representatives of Saccammina, Rhabdammina, Bathysiphon, etc. A parathuramminid character, which is unusual among the foraminifers, is the presence of double chambers joined together; examples are known in Bithurammina, Bisphaera, Bituberitina, Eovolutina, and various parathuramminidae and uralinellidae (e.g., Grozdilova and Lebedeva, Reference Grozdilova and Lebedeva1954, pl. 2, fig. 9; Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1962, pl. 2, fig. 1; Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1965, pl. 2, fig. 2; Chuvashov, Reference Chuvashov1965, pl. 3, fig. 7; Poyarkov, Reference Poyarkov1969, pl. 3, fig. 10; Brunner, Reference Brunner1975, pl. 2, fig. 7, 1976, pl. 4, fig. 9; Poyarkov, Reference Poyarkov1979, pl. 6, fig. 6; Zukalova, Reference Zukalova1981, pl. 2, figs. 1, 2; Petrova, Reference Petrova1981, pl. 11, figs. 3, 5; Kotlyar, Reference Kotlyar1982, text-fig. 4; Lin and Hao, Reference Lin and Hao1982, pl. 1, fig. 24; Doan in Tong et al., Reference Tong, Dang, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Ta, Pham and Doan1988, pl. 1, fig. 4; Vachard and Clément, Reference Vachard and Clément1994, pl. 2, fig. 8). If the external additional chamber is often questionable (except for Parathurammina praetuberculata ramosa Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1962, pl. 1, fig. 7), internal chambers are most significant, as for example, in Parathurammina (?) aff. P. dagmarae (sic) sensu Grozdilova and Lebedeva, Reference Grozdilova and Lebedeva1954, pl. 2, figs. 7, 8; and Parathurammina sp. (Grozdilova and Lebedeva, Reference Grozdilova and Lebedeva1954, pl. 2, fig. 9; Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1962, pl. 2, fig. 1; and Poyarkov, Reference Poyarkov1969, pl. 3, fig. 10). These forms have been termed Bithurammina Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1963, even if this taxon remains invalid because its type species, Parathurammina (?) aff. P. dagmarae sensu Grozdilova and Lebedeva, was never correctly re-named (see Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1965; Ektova, Reference Ektova1968; Poyarkov, Reference Poyarkov1969, Reference Poyarkov1979; Kotlyar, Reference Kotlyar1982; Doan in Tong et al., Reference Tong, Dang, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Ta, Pham and Doan1988; Vachard, Reference Vachard1991).

Subfamily Parathurammininae Bykova in Bykova and Polenova; Reference Bykova and Polenova1955 emend. Vachard, Reference Vachard1994

Diagnosis

Test free, moderate to large in size, globular with many papilliform projections; thin wall unilayered dark-microgranular, or bilayered with an additionally inner pseudofibrous layer. One distal, areal aperture at the end of each projection.

Occurrence

Ordovician–early Visean; probably cosmopolitan.

Remarks

Synonym of Parathuramminae (sic) Zadorozhnyi, Reference Zadorozhnyi1987 and Dagmarellinae Chuvashov, Yuferev and Zadorozhnyi in Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984 (nomen nudum; see earlier), this subfamily encompasses the genera: Parathurammina Suleimanov, Reference Suleimanov1945; Bykovaella Zadorozhnyi in Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984; Kolongella Zadorozhnyi in Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984; and ?Bithurammina Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1965 non 1963.

Genus Parathurammina Suleimanov, Reference Suleimanov1945

Type species

Parathurammina dagmarae Suleimanov, Reference Suleimanov1945.

Other species

Parathurammina arguta Pronina, Reference Pronina1960; P. eodagmarae Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1954; P. graciosa Pronina, Reference Pronina1960; P. kokschaalica Ektova, Reference Ektova1968; P. magna Antropov, Reference Antropov1950; P. oldae Suleimanov, Reference Suleimanov1945; P. parabreviradiosa Saltovskaya, Reference Saltovskaya1981; P. paradagmarae Grozdilova and Lebedeva, Reference Grozdilova and Lebedeva1954; P. uralica Petrova, Reference Petrova1981; ?P. cordata Pronina, Reference Pronina1960; ?P. eoarguta Sabirov, Reference Sabirov1984; ?P. marginara Pronina, Reference Pronina1960; ?P. tamarae Petrova, Reference Petrova1981 (eventually with a median layer, more or less diaphanothecal, within the external dark layer, supposed characteristic of Cordatella and/or Marginara); ?Thurammina adamsi Conkin and Conkin, Reference Conkin and Conkin1964; ?T. arcuata Moreman, Reference Moreman1930; ?T. arenacorna Gutschick, Weiner, and Young, Reference Gutschick, Weiner and Young1961; ?T. echinata Dunn, Reference Dunn1942; ?T. elegans Dunn, Reference Dunn1942; ?T. elliptica Moreman, Reference Moreman1930; ?T. foerstei Dunn, Reference Dunn1942 (= Amphitremoidea according to Nestell and Tolmacheva, Reference Nestell and Tolmacheva2004); ?T. globosa Ireland, Reference Ireland1939; ?T. hexagona Dunn, Reference Dunn1942: ?T. ?hexactinellida Dunn, Reference Dunn1942; ?T. irregularis Moreman, Reference Moreman1930; ?T. inflata Dunn, Reference Dunn1942; ?T. jubata Dunn, Reference Dunn1942; ?T. lawrencensis Ireland, Reference Ireland1956; ?T. limbata Dunn, Reference Dunn1942; ?T. limbata var. disciformis Dunn, Reference Dunn1942; ?T. magna Dunn, Reference Dunn1942; ?T. melleni Dunn, Reference Dunn1942; ?T. papillata Moreman, Reference Moreman1930; ?T. papillata var. monticulifera Ireland, Reference Ireland1939; ?T. parvituba Dunn, Reference Dunn1942 (= Amphitremoidea according to Nestell and Tolmacheva, Reference Nestell and Tolmacheva2004); ?T. phasela Moreman, Reference Moreman1930; ?T. polygona Ireland, Reference Ireland1939; ?T. pustulosa Gutschick, Weiner, and Young, Reference Gutschick, Weiner and Young1961; ?T. quadrata Dunn, Reference Dunn1942; ?T. sphaerica Ireland, Reference Ireland1939; ?T. subpapillata Ireland, Reference Ireland1939; ?T. tubulata Moreman, Reference Moreman1930; and ?T. micropapillata Blumenstengel, Reference Blumenstengel1961, perhaps belong to Parathurammina, even if the microstructure of their wall remains unknown.

Diagnosis

Test free, moderate to large in size, globular with many papilliform projections; thin wall dark-microgranular with an inner pseudofibrous layer. One distal, areal aperture at the end of each projection.

Occurrence

Ordovician–Mississippian; cosmopolitan.

Remarks

Parathurammina s.s. is partially synonymous with Thurammina (partim), ?Cordatella (partim), ?Marginara (partim), and ?Guangxithurammina Lin et al., Reference Lin, Li and Sun1990. The genus Chrysothurammina Neumann, Pozaryska, and Vachard, Reference Neumann, Pozaryska and Vachard1975 differs from Parathurammina because the pseudofibrous layer of the wall that surrounds the inner chamber also penetrates the necks.

Parathurammina graciosa Pronina, Reference Pronina1960

Figures 9.4, 9.6, 9.7, 9.15, 9.19–9.23, 9.27, 9.28?, 10.2

Figure 9 (1, 8) Paracaligella ex gr. antropovi Lipina, Reference Lipina1955: (1) longitudinal section of a tubular chamber resembling Irregularina, sample POL 3-7; (8) more regular longitudinal section, sample POL 11b-25. (2) Earlandia sp. 1, small curved longitudinal section, sample POL11a-30. (3) Neoarchaesphaera? sp., sample POL11a-20. (4, 6, 7, 15, 19, 21–23, 27, 28?) Parathurammina graciosa Pronina, Reference Pronina1960: (4) sample POL11a-24; (6) sample POL3-1a; (7) with Bykovaella breviradiosa (Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1962), sample POL11-2; (15) sample POL11-1; (19) sample POL11-7; (21) sample POL11-9; (22) pseudofibrous, inner layer well visible here, sample POL11a-4; (23) sample POL 11a-10; (27) sample POL11a-14; (28) sample POL11a-39. (5) Earlandia sp. 2. Broader, rectilinear, slightly tapering test, sample POL11a-31. (9) Neoarchaesphaera ellipsoidalis (Poyarkov, Reference Poyarkov1969), sample POL11a-29. (10) Suleimanovella cf. S. totaensis (Petrova, Reference Petrova1981), sample POL11a-16. (11, 12) Paracaligella sp. 2: (11) sample POL 13b-9; (12) sample POL13b-14. (13, 14, 18) Parathurammina cf. P. uralica Petrova, Reference Petrova1981: (13) sample POL3-1; (14) sample POL3-2; (18) sample POL11b-12a. (16, 17, 24, 25) Bykovaella aperturata (Pronina, Reference Pronina1960) emend. Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984: (16) sample POL11-3; (17) sample POL11-6; (24) POL11a-12; (25) sample POL11a-6a. (20) ?Bithurammina aff. B. sphaerica Ektova, Reference Ektova1968, sample POL.14-33. (26) Parathurammina arguta Pronina, Reference Pronina1960, sample POL11a-6. Scale bars=0.1 mm.

1960 Parathurammina graciosa Reference ProninaPronina, p. 47, pl. 1, figs. 1, 2.

1969 Parathurammina graciosa; Reference MalakhovaMalakhova, pl. 51, figs. 350, 351, 355.

1969 Parathurammina cf. graciosa; Reference MalakhovaMalakhova, pl. 48, fig. 329, pl. 51, fig. 361.

1969 Parathurammina (Salpingothurammina) graciosa; Reference PoyarkovPoyarkov, table 19.

1971 Parathurammina graciosa; Reference Menner and ReitlingerMenner and Reitlinger, p. 29, pl. 8, fig. 5.

1979 Parathurammina graciosa; Reference Lavrusevich, Lavrusevich and SaltovskayaLavrusevich et al., p. 322.

1979 Parathurammina (Salpingothurammina) graciosa; Reference PoyarkovPoyarkov, text-fig. 14.

1981 Parathurammina graciosa; Reference PetrovaPetrova, pl. 8, figs. 4, 5, 8.

1985 Parathurammina graciosa; Reference ZadorozhnyiZadorozhnyi, p. 126, 131?, pl. 17, fig. 1, pl. 18, figs. 1, 2.

1990 Parathurammina graciosa; Reference Bogush and YuferevBogush and Yuferev, p. 20.

2008 Parathurammina graciosa; Reference AnfimovAnfimov, p. 78.

2011 Parathurammina graciosa; Reference AnfimovAnfimov, p. 16.

2014 Parathuramminide; Reference MörtlMörtl, text-fig. 33b.

Holotype

Axial section (No. 476/3 Museum of the Geological Direction of the Urals) from the early Givetian of the central Urals, Russia (Pronina, Reference Pronina1960, pl. 1, fig. 1).

Diagnosis

Relatively large species characterized by a large central chamber, and numerous necks, asymmetrically arranged. Necks short, with a narrow central channel, entirely cylindrical (i.e., with neither proximal nor distal enlargement). Wall thin, bilayered, dark-microgranular, and hyaline-microgranular.

Occurrence

Middle Eifelian–early Givetian of eastern slope of the central Urals. Givetian of northern and southwestern Siberia and Zeravshano-Gissar (Tajikistan). Frasnian of SW Siberia (Bogush et al., Reference Bogush, Bochkarev and Yuferev1975). Discovered in the Givetian of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Description

Test outer diameter=0.15–0.31 mm (type material: 0.09–0.27 mm); central chamber diameter=0.12–0.20 mm; number of necks: 11–13; length of necks=0.004–0.13 mm (for a wall thickness of 0.008 to 0.01 mm); test wall thickness=0.003–0.007 mm (type material: 0.004–0.007 mm).

Materials

32 specimens (samples POL3-1a, POL11-1, POL11-2, POL11-7, POL11-9, POL11a-4, POL11a-10, POL11a-14, POL11a-21, POL11a-24, ?POL11a-39).

Parathurammina cf. P. uralica Petrova, Reference Petrova1981

Figures 9.13, 9.14, 9.18, 10.1, 10.10

1981 Parathurammina uralica Reference PetrovaPetrova, p. 86, pl. 6, figs. 3, 5, 6.

1990 Bykovaella uralica; Reference Bogush and YuferevBogush and Yuferev, p. 21.

?2009 Parathurammina crassitheca Antropov; Reference Mamet and PréatMamet and Préat , fig. 1.19 only (non fig. 1.18=Kolongella).

2011 Parathurammina uralica; Reference AnfimovAnfimov, p. 16.

Holotype

Axial section (No. 3/1868; Geological Museum of the Urals UTGU) from the Eifelian of the northern Urals, Russia (Petrova, Reference Petrova1981, pl. 6, fig. 3).

Diagnosis

Relatively large species characterized by numerous necks, asymmetrically arranged. Necks short, with a narrow central channel, entirely cylindrical (i.e., without proximal or distal enlargement). Wall thin, bilayered, dark-microgranular, and hyaline-microgranular.

Occurrence

Eifelian of the northern and central Urals. Doubtful in the late Eifelian of Belgium. Givetian of SW Siberia. Givetian of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Description

Outer diameter=0.17–0.40 mm (type material: 0.13–0.24 mm); inner diameter=0.14–0.30 mm; length of necks=0.03–0.04 mm (for a wall of 0.01–0.02 mm); test wall thickness=0.015–0.04 mm (type material: 0.015–0.03 mm).

Materials

12 specimens (samples POL3-1, POL3-2, POL11, POL11b-12a, POL13a-2b).

Remarks

This species might be a homeomorph of Bykovaella irregulariformis (Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984) and/or B. oblisa (Petrova, Reference Petrova1981), but it has a bilayered wall and consequently belongs to Parathurammina. In this genus, P. uralica is the most similar species compared to our taxon.

Parathurammina arguta Pronina, Reference Pronina1960

Figures 9.26, 10.7 (partim), 10.9, 10.10

1960 Parathurammina arguta Reference ProninaPronina, p. 7, pl. 1, fig. 5.

1969 Parathurammina arguta; Reference PoyarkovPoyarkov, table 12.

1979 Parathurammina arguta; Reference Lavrusevich, Lavrusevich and SaltovskayaLavrusevich et al., p. 323.

1979 Parathurammina (Parathurammina) arguta; Reference PoyarkovPoyarkov, text-fig. 13.

1981 Parathurammina (Parathurammina) aperturata; Reference PetrovaPetrova, pl. 7, figs. 9–11.

1985 Parathurammina arguta; Reference ZadorozhnyiZadorozhnyi, p. 127, pl. 17, fig. 6.

2013 Parathurammina arguta; Reference Makarenko and SavinaMakarenko and Savina, p. 128.

2014 Parathuramminide; Reference MörtlMörtl, text-fig. 33a.

Holotype

Axial section (No. 476/8 Museum of the Geological Direction of the Urals) from the early Givetian of the central Urals, Russia (Pronina, Reference Pronina1960, pl. 1, fig. 5).

Diagnosis

Relatively large species characterized by numerous necks, regularly, radially arranged. Necks short, papilliform. Wall thin, bilayered, dark-microgranular and clear-pseudofibrous.

Occurrence

Eifelian–early Givetian of the central Urals and Givetian of the northern Urals (Pronina, Reference Pronina1960; Petrova, Reference Petrova1981), Zeravshano-Gissar (Lavrusevich et al., Reference Lavrusevich, Lavrusevich and Saltovskaya1979), and Siberia (Zadorozhnyi, Reference Zadorozhnyi1985, Reference Zadorozhnyi1987). Givetian of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Description

Outer diameter=0.27–0.50 mm (type material: 0.34–0.52 mm); inner diameter=0.15–0.37 mm; number of necks: 13–15; length of necks=0.01–0.06 mm (for a wall of 0.015 mm); test wall thickness=0.01 mm (type material: 0.01 mm).

Materials

Eight specimens (samples POL11a-6, POL11b-5, POL13a-1, POL13a-7).

Genus Bykovaella Zadorozhnyi in Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984

Type species

Parathurammina aperturata Pronina, Reference Pronina1960.

Other species

Parathurammina breviradiosa Reitlinger in Varsanofieva and Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1962; P. argensis Sabirov, Reference Sabirov1987a; P. bykovae Poyarkov in Purkin et al., Reference Purkin, Poyarkov and Rozhanets1961; P. crassitheca Antropov, Reference Antropov1950; P. dagmarae var. crassitheca Antropov, Reference Antropov1950; P. iniqua Pronina, Reference Pronina1970; Polygonella irregulariformis Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984; Parathurammina irregularis Pronina, Reference Pronina1960; P. khavsakiensis Sabirov, Reference Sabirov1987a; P. macilenta Pronina, Reference Pronina1970; P. mirabilis (sic mirabile) Saltovskaya, Reference Saltovskaya1981; P. praeaperturata Saltovskaya, Reference Saltovskaya1981; P. turgida Chuvashov, Reference Chuvashov1965.

Diagnosis

Test free, moderate in size, globular with many tubular projections; thin wall dark-microgranular. One areal aperture at the end of each projection.

Occurrence

Late Silurian, Early–Middle Devonian, Late Devonian (Frasnian–early Famennian), early Tournaisian of Russian Platform, the Urals, western Siberia, Tian Shan (Tajikistan), South China, Spain, western and northern France, ?Germany (see Vachard, Reference Vachard1991). Discovered in the Givetian of Austria.

Remarks

Many Bykovaella of the literature have been designated by Parathurammina (partim), Thurammina (partim), Salpingothurammina (partim), and Polygonella (partim).

Bykovaella aperturata (Pronina, Reference Pronina1960) emend. Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984

1928 Calcisphères de La Villedé, formes épineuses; Reference MilonMilon, fig. 35.1, 35.2, 35.4, 35.6 (non 35.3, 35.5, 35.7, 35.8), pl. 2, fig. 1a, 1a’.

1960 Parathurammina aperturata; Reference ProninaPronina, p. 47, pl. 1, fig. 3.

1969 Parathurammina aperturata; Reference PoyarkovPoyarkov, p. 87, pl. 1, figs. 2, 5.

1969 Parathurammina aperturata; Reference MalakhovaMalakhova, pl. 49, figs. 337, 338, pl. 50, fig. 344, pl. 52, fig. 359.

non1971 Parathurammina aperturata; Reference Menner and ReitlingerMenner and Reitlinger, p. 29, pl. 8, figs. 2, 7–9 (= Elenella reitlingerae n. sp.).

1977 Parathurammina aperturata; Petrova, p. 4, text-figs. 1, 2.

1979 Parathurammina aperturata; Reference PoyarkovPoyarkov, p. 44, pl. 5, fig. 2.

1979 Parathurammina aperturata; Reference Lavrusevich, Lavrusevich and SaltovskayaLavrusevich et al., p. 322.

1979 Parathurammina (Salpingothurammina) aperturata; Reference PoyarkovPoyarkov, p. 96, text-fig. 14.

1979 Parathurammina apertura (sic); Reference Dubreuil and VachardDubreuil and Vachard, p. 241.

non 1981 Parathurammina aperturata; Reference SaltovskayaSaltovskaya, p. 107, pl. 2, fig. 6, pl. 3, figs. 6, 8 (= Neoarchaesphaera).

1984 Bykovaella aperturata; Reference Zadorozhnyi and YuferevZadorozhnyi and Yuferev, p. 79, pl. 1, figs. 3–5.

1985 Bykovaella aperturata; Reference ZadorozhnyiZadorozhnyi, p. 126, pl. 17, fig. 2, pl. 18, fig. 3.

1987 Bykovaella aperturata; Reference ZadorozhnyiZadorozhnyi, p. 16, pl. 1, figs. 4–7.

non 1987 Parathurammina aperturata; Reference Loeblich and TappanLoeblich and Tappan, pl. 207, fig 17.

1988 Bykovaella aperturata; Reference Bogush, Zarodozhnyi and IvanovaBogush et al., p. 5.

1990 Bykovaella aperturata; Reference Bogush and YuferevBogush and Yuferev, p. 20.

1991 Parathurammina crassitheca Antropov; Reference VachardVachard, p. 261, pl. 1, fig. 25.

1994 Parathurammina aperturata; Reference VachardVachard, p. 20, text-fig. 12.6.

1994 Parathurammina crassitheca; Reference VachardVachard, p. 20, text-fig. 12.5 only (non pl. 1, figs. 2, 12–23, nec pl. 2, figs. 1, 7) (with 40 references in synonymy).

2002 Bykovaella aperturata; Reference KalvodaKalvoda, p. 26, text-fig. 11.

2008 Bykovaella aperturata; Reference TsygankoTsyganko, p. 70, text-fig. 3.

2009 Parathurammina du groupe P. dagmarae Suleimanov; Reference Mamet and PréatMamet and Préat, pl. 1, figs. 12, 15, 17 (non figs. 11, 14, 16=other species of Bykovaella, nec fig. 13=Kolongella).

2011 Parathurammina aperturata; Reference AnfimovAnfimov, p. 16.

2013 Parathurammina aperturata; Reference SabirovSabirov, p. 115, text-fig. 1.

2013 Parathurammina aperturata; Reference Makarenko and SavinaMakarenko and Savina, p. 128.

Holotype

Axial section (No. 476/6 Museum of the Geological Direction of the Urals) from the early Givetian of the central Urals, Russia (Pronina, Reference Pronina1960, pl. 1, fig. 3).

Diagnosis

Relatively large species characterized by numerous necks, regularly, radially arranged. Necks long with a narrow central channel, entirely cylindrical (i.e., without either proximal or distal enlargement). Wall thin.

Occurrence

Eifelian–early Givetian of the central and southern Urals (Pronina, Reference Pronina1960); Eifelian of the Tomsk area (SW Siberia; Makarenko and Savina, Reference Makarenko and Savina2013). Givetian of western France (Milon, Reference Milon1928, re-interpreted here; Dubreuil and Vachard, Reference Dubreuil and Vachard1979), Zeravshano-Gissar (Lavrusevich et al., Reference Lavrusevich, Lavrusevich and Saltovskaya1979), southern Fergana (Tian Shan; Poyarkov, Reference Poyarkov1969; Saltovskaya, 1981), Siberia (Menner and Reitlinger, Reference Menner and Reitlinger1971; Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984; Zadorozhnyi, Reference Zadorozhnyi1985, Reference Zadorozhnyi1987; Bogush and Yuferev, Reference Bogush and Yuferev1990), Germany (Flügel and Hötzl, Reference Flügel and Hötzl1971), South China (Lin and Hao, Reference Lin and Hao1982), and Belgium (Mamet and Préat, Reference Mamet and Préat2009). Givetian of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Description

Outer diameter=0.30–0.35 mm (type material: 0.18–0.34 mm); inner diameter=0.22–0.25 mm; number of necks: 15–16; length of necks=0.01–0.07 mm (with a wall of 0.007–0.015 mm); test wall thickness=0.005 mm (type material: 0.005–0.01 mm).

Materials

Twelve specimens (samples POL11-3, POL11-6, POL11a-6a, POL11a-12).

Remarks

Bykovaella crassitheca (Antropov, Reference Antropov1950) differs only by a thicker wall (0.02–0.025 mm) and a Frasnian age.

Bykovaella breviradiosa (Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1962)

Figure 10 (1, 10) Parathurammina cf. P. uralica Petrova, Reference Petrova1981: (1) sample POL11b-13; (10) sample POL13a-2b. (2) Parathurammina graciosa Pronina, Reference Pronina1960, sample POL11a-21. (3) Bykovaella breviradiosa (Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1962), sample POL11b-19b. (4–8) Bykovaella bykovae (Poyarkov in Purkin et al., Reference Purkin, Poyarkov and Rozhanets1961): (4) sample POL13a-5; (5) sample POL13a-6; (6) sample POL13a-8; (7) right, with P. arguta (left), sample POL11b-5; (8) sample POL11b-19. (7, 9, 10) Parathurammina arguta Pronina, Reference Pronina1960; (7) (with Bykovaella bykovae), sample POL11-2; (9) sample POL13a-1; (10) sample POL13a-7. (11) Kolongella cf. K. pojarkovi Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984, sample POL11b-21. (12) Salpingothurammina sp. 1, sample POL13a-3. (13) Ivanovella sp. 1, sample POL11a-9. (14) Ivanovella sp. 2, sample POL11a-10b. (15) Ivanovella sp. 3, sample POL11-5. (16, 17, 22?) Ivanovella reitlingerae n. sp.: (16) holotype, sample POL11a-38; (17) paratype, sample POL11a-40; (22) paratype?, sample POL11a-2. (18, 20, 21) Ivanovella luginensis Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev in Dubatolov, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1981: (18) sample POL11b-18a; (20) sample POL11b-21b; (21) sample POL11a-9a. (19) Ivanovella sp. 4, sample POL11a-8. (23) Salpingothurammina cf. S. kakvensis (Petrova, Reference Petrova1981), sample POL13a-3a. (24) Bithurammina aff. B. sphaerica Ektova, Reference Ektova1968, sample POL11a-34. (25) Suleimanovella sp. 2., sample POL4c. (26, 27) Suleimanovella sp. 3: (26) sample POL11b-12; (27) sample POL13b-10. (28–32) Radiosphaerella poyarkovi n. sp.: (28) holotype, sample POL11b-24; (29) paratype, sample POL11a-25a; (30) paratype, sample POL11a-22; (31) paratype, sample POL11a-17; (32) paratype, sample POL11a-11. (33) Marginara? sp., sample POL14-24. (34) Parathuramminites sp., sample POL14-1. (35, 36) Bykovaella cf. B. macilenta (Pronina, Reference Pronina1970): (35) sample POL14-21; (36) sample POL14-20. (37) Vasicekia? sp., sample POL3-6. Scale bars=0.1 mm.

1962 Parathurammina breviradiosa Reference ReitlingerReitlinger, p. 52, pl. 1, figs. 1, 2.

1965 Parathurammina breviradiosa; Reference ChuvashovChuvashov, p. 19, pl. 1, figs. 4–6.

1969 Parathurammina breviradiosa; Reference PoyarkovPoyarkov, table 12.

1969 Parathurammina breviradiosa; Reference MalakhovaMalakhova, pl. 51, fig. 356.

1979 Parathurammina breviradiosa; Reference PoyarkovPoyarkov, pl. 3, fig. 4.

1979 Parathurammina (Parathurammina) breviradiosa; Reference PoyarkovPoyarkov, text-fig. 13.

1981 Parathurammina breviradiosa; Reference PetrovaPetrova, pl. 8, fig. 19.

1981 Parathurammina breviradiosa; Reference ZadorozhnyiZadorozhnyi, p. 111 (no. 3 of the table).

?1981 Parathurammina magna Antropov; Reference ZukalovaZukalova, pl. 1, fig. 2.

1984 Parathurammina breviradiosa; Reference Zadorozhnyi and YuferevZadorozhnyi and Yuferev, p. 77, pl. 1, figs. 1, 2.

1987 Parathurammina breviradiosa; Reference ZadorozhnyiZadorozhnyi, p. 14, pl. 1, figs. 1–3.

1988 Parathurammina breviradiosa; Reference Bogush, Zarodozhnyi and IvanovaBogush et al., p. 22.

1989 Parathurammina dagmarae Suleimanov; Reference Préat and MametPréat and Mamet, pl. 6, fig. 5 only (non figs. 4, 6=Parathuramminites).

1990 Parathurammina breviradiosa; Reference Lin, Li and SunLin et al., p. 124, pl. 3, figs. 1–4.

1990 Parathurammina breviradiosa; Reference Bogush and YuferevBogush and Yuferev, p. 20.

1994 Parathurammina breviradiosa; Reference VachardVachard, text-fig. 12.1.

?1999 Parathurammina du groupe P. dagmarae Suleimanov (= Salpingothurammina breviradiosa [Reitlinger]) (sic); Reference Mamet, Préat and LehmamiMamet et al., pl. 5, figs. 13, 14.

2005 Late Devonian calcisphere; Reference Kaźmierczak and KremerKaźmierczak and Kremer, fig. 6F.

2008 Parathurammina breviradiosa; Reference AnfimovAnfimov, p. 80.

2013 Parathurammina breviradiosa; Reference Makarenko and SavinaMakarenko and Savina, p. 128.

2014 Parathuramminide; Reference MörtlMörtl, text-fig. 33b.

Holotype

Axial section (No. 3456/2 Geological Institute Nauk, Akademiya Nauk SSSR) from the Frasnian of the central Urals, Shezhym oblast, Russia (Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1962, pl. 1, fig. 1).

Diagnosis

Relatively moderate species, characterized by a few necks, irregularly arranged, short to medium-sized, with a narrow central channel, and with a distal enlargement. Wall thin.

Occurrence

Eifelian of the Tomsk area (SW Siberia). Givetian of the northern Urals (Petrova, Reference Petrova1981), and perhaps Moravia (Zukalova, Reference Zukalova1981) and Morocco (Mamet et al., Reference Mamet, Préat and Lehmami1999). Late Devonian of Siberia (Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev, Reference Zadorozhnyi and Yuferev1984; Bogush and Yuferev, Reference Bogush and Yuferev1990), Frasnian of the northern Urals, early Famennian of the central Urals (Chuvashov, Reference Chuvashov1965). Late Famennian of SW Siberia (Bogush and Yuferev, Reference Bogush and Yuferev1990). Discovered in the Givetian of Mount Polinik (Carnic Alps, Austria).

Description

Outer diameter=0.20–0.40 mm (type material: 0.20–0.48 mm); inner diameter=0.13–0.41 mm; number of necks: 4–9; length of necks=0.70–0.90 mm (with a wall of 0.007–0.015 mm); test wall thickness=0.003–0.006 mm.

Materials

10 specimens (samples POL11-2 and POL11b-19b).

Bykovaella bykovae (Poyarkov in Purkin et al., Reference Purkin, Poyarkov and Rozhanets1961)

Figure 10.4–10.6, 10.7 (partim), 10.8

?1955 Parathurammina magna Reference Bykova and PolenovaBykova, p. 17, pl. 2, figs. 4, 5, pl. 4, fig. 5.

1961 Thurammina (Salpingothurammina) bykovae Poyarkov in Reference Purkin, Poyarkov and RozhanetsPurkin et al., p. 31, pl. 1, fig. 1 (non fig. 6).

1969 Parathurammina (Salpingothurammina) bykovae; Reference PoyarkovPoyarkov, p. 86, pl. 1, figs. 3–6.

?1971 Parathurammina dagmarae Suleimanov; Reference Flügel and HötzlFlügel and Hötzl, p. 370, fig. 2.1–2.4.

1979 Parathurammina (Salpingothurammina) bykovae; Reference PoyarkovPoyarkov, text-fig. 14.

1979 Parathurammina bykovae (Reference PoyarkovPoyarkov); Reference Lavrusevich, Lavrusevich and SaltovskayaLavrusevich et al., p. 322.

?1981 Parathurammina dagmarae; Reference ZukalovaZukalova, pl. 1, fig. 1.

1984 Bykovaella bykovae; Reference Zadorozhnyi and YuferevZadorozhnyi and Yuferev, p. 80, pl. 1, fig. 6.

1988 Bykovaella bykovae; Reference Bogush, Zarodozhnyi and IvanovaBogush et al., p. 5.

?1994 Parathurammina bykovae; Reference VachardVachard, p. 22, text-fig. 12.1, pl. 2, figs. 1, 2 (with 11 references in synonymy) (see B. cf. B. macilenta).

2002 Bykovaella bykovae; Reference KalvodaKalvoda, text-figs. 11, 12.

?2004 Parathurammina dagmarae; Reference FlügelFlügel, text-fig. 10.24.

2008 Bykovaella bykovae; Reference TsygankoTsyganko, p. 71, text-fig. 3.

2008 Bykovaella bykovella (sic); Reference TsygankoTsyganko, p. 74.