Introduction

Lungfish constitute a long-lived group of marine and freshwater fishes that first appeared in the Early Devonian and were distributed globally until the beginning of the Paleogene. Today, however, the group is limited to six species distributed among three families and restricted to freshwater environments in the southern continents: Australia (Neoceratodontidae), South America (Lepidosirenidae), and Africa (Protopteridae). Australian lungfish are most similar to the Paleozoic and Mesozoic forms in their possession of flipper-like fins, a single lung, and large scales, whereas the other two families have fins that are reduced to filaments, paired lungs, small scales, and eel-like bodies. The unusual respiratory system of lungfish is employed for several reasons but is often used to survive low-oxygen water conditions or estivation. Extant lungfish feed on a variety of invertebrates and small vertebrates (Kemp, Reference Kemp1986; Kirkland, Reference Kirkland1987).

Fossil lungfish, which are typically represented by only their distinctive tooth plates, have been recovered from all continents, including Antarctica (Dziewa, Reference Dziewa1980; Clack et al., Reference Clack, Sharp, Long, Jørgensen and Joss2011). Most lungfish have two pairs of primary masticatory tooth plates, an upper set attached to the paired entopterygoids and a lower, opposing set supported by the paired prearticular bones. The tooth plate is essentially a contiguous crown formed of a dentine complex supported by trabecular bone. Tooth plates consist of several ridges (or crests) radiating labially from a common mesiolingual origin, each ridge formed by the fusion of linearly arranged cusps (or denticles) in the juvenile (Kemp, Reference Kemp2001) and terminating labially to a point. The sharp, cuspate ridges wear with age and gradually dull, producing a more subdued occlusal surface lingually. The number and configuration of tooth plate ridges have been used repeatedly in the literature for species diagnoses as well as for demonstrating phyletic or phenetic relationships. The angles between the ridges depend on two factors, the angle of growth and the angle of wear, but only the angle of growth can be used for taxonomic determination (Kemp, Reference Kemp1997). As has been previously reported, lungfish exhibit considerable intraspecific variation in tooth plate morphology; therefore, it can be difficult to identify them to the specific or even generic level without additional cranial material (Schultze, Reference Schultze1981; Pardo et al., Reference Pardo, Huttenlocker, Small and Gorman2010; Otero, Reference Otero2011; Frederickson and Cifelli, Reference Frederickson and Cifelli2017). However, some authors argue that isolated tooth plates can be reliably used as taxonomic indicators (e.g., Kemp, Reference Kemp1998).

In North America, lungfish were believed to have become extinct during the Cenomanian (Kirkland, Reference Kirkland1987) until tooth plates were recovered from the Late Cretaceous (late Campanian) Mount Laurel Formation in New Jersey (Parris et al., Reference Parris, Grandstaff and Gallagher2004) and the Iron Springs Formation (late Santonian) of Utah (Eaton et al., Reference Eaton, Gardner, Kirkland, Brinkman, Nydam, MacLean, Biek and Huntoon2014). The New Jersey specimen became the first definitive record of Late Cretaceous lungfish from North America east of the Western Interior Seaway (Appalachia). Although the New Jersey specimen extended the geochronologic range of eastern North American lungfish to the late Campanian, a substantial temporal gap in the fossil record (of ~20 million years) remained between the New Jersey specimen and the Cenomanian lungfish of east Texas (Main, Reference Main2013; Main et al., Reference Main, Parris, Grandstaff and Carter2014).

In 1998, Columbus, Mississippi, resident Eric Loftis was collecting fossil material from a transgressive lag deposit in the Late Cretaceous Eutaw Formation at Luxapallila Creek in Lowndes County, Mississippi, when he discovered a partial lungfish tooth plate with attached bone material. This fossil was donated to G. Phillips of the Mississippi Museum of Natural Science (MMNS) and accessioned into the collections. In 2012, another lungfish tooth plate was collected from material screened from the Late Cretaceous Tombigbee Sand Member of the Eutaw Formation by a Wright State University (Ohio) student during a field trip to Trussells Creek in Greene County, Alabama. The fossil was given to the first author, who later placed the specimen in the collections of the Alabama Museum of Natural History (ALMNH). These specimens are remarkable because they are the first records of lungfish from the eastern Gulf Coastal Plain and fill a spatiotemporal gap between the Cenomanian lungfish of the Western Interior and those of the late Campanian of the Atlantic Coastal Plain.

Geologic setting

The Upper Cretaceous Eutaw Formation in Alabama and Mississippi is divided into the lower unnamed member (from here referred to as “lower Eutaw Formation”) and the upper Tombigbee Sand Member. The fossil lungfish specimens described herein were obtained from two distinct lithofacies within the Eutaw Formation, suggestive of different source habitats.

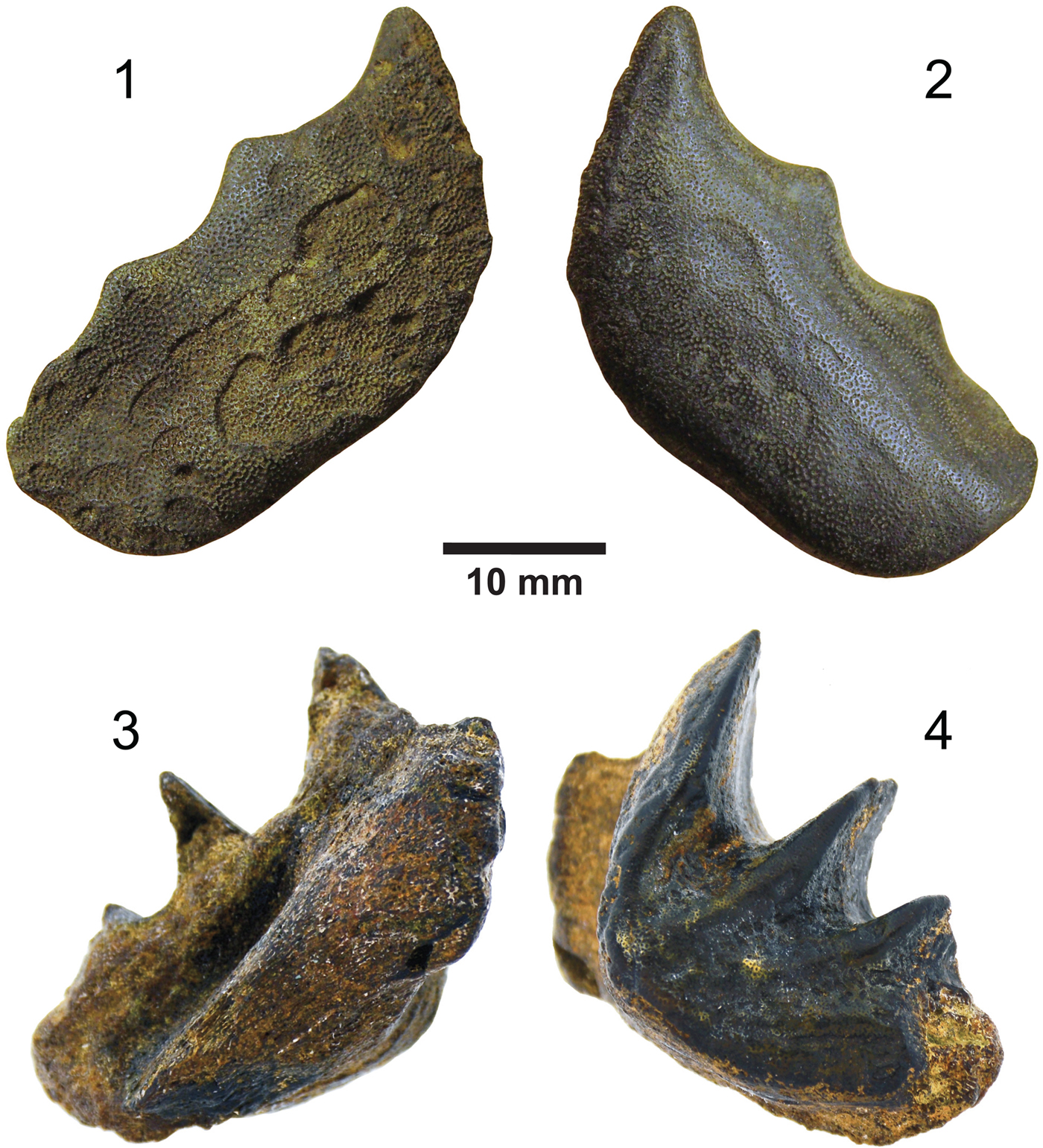

The Alabama specimen (ALMNH 8723; Fig. 1.1, 1.2) was screened from gravel derived from the Tombigbee Sand Member in the stream bed of Trussells Creek in Greene County, Alabama. This site, designated ALMNH locality AGr-43, is located on private property and accessible to ALMNH staff through an agreement with the current landowners (Fig. 2). The Mississippi specimen (MMNS VP-3440; Fig. 1.3, 1.4) was collected in situ within the Eutaw Formation along a channelized length of Luxapallila Creek in Columbus, Lowndes County, Mississippi (MMNS locality MS.44.001). Although stratigraphically and geographically separated from typical Tombigbee Sand lithology, the unusual macrofossiliferous bed along this section of Luxapallila Creek is arguably time equivalent. The MS.44.001 locality (MMNS locality number) is on private property managed by the Tombigbee River Valley Water Management District (Fig. 2). Unfortunately, most of the site is now overgrown in riparian vegetation or covered by riprap revetment.

Figure 1. Lungfish right prearticular tooth plates in approximate life position (anterior at top). (1, 2) Ceratodus frazieri Ostrom Reference Ostrom1970, ALMNH 8723, in (1) aboral and (2) occlusal views. (3, 4) Ceratodus carteri Main et al., Reference Main, Parris, Grandstaff and Carter2014, MMNS VP-3440, in (3) aboral and (4) occlusal views. Scale bar = 10 mm.

Figure 2. (1) Geologic map of outcropping Late Cretaceous marine strata and lateral equivalents in Mississippi and Alabama, showing collection localities MS.44.001 in Lowndes County, Mississippi, and AGr-43 in Greene County, Alabama. Localities indicated by stars. (2) Stratigraphic column of Late Cretaceous geologic units in the study area (top right) showing approximate horizons of (A) ALMNH 8723 and (B) MMNS VP-3440. Stratigraphic data modified from Mancini and Puckett (Reference Mancini, Puckett, Armentrout and Rosen2002) using chronostratigraphic divisions of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) chart, version 2017/02. County scale bar = 10 km.

At the request of the landowners, precise locality information for these two sites is not published here. However, the information may be obtained by request through ALMNH or MMNS.

Trussells Creek

The Tombigbee Sand exposure at Trussells Creek (AGr-43) consists of ~5–6 m of massive to weakly bedded, well-sorted, fine-grained, angular to subangular, light gray quartz sand, with subordinate quantities of glauconite, muscovite, feldspar, and heavier mineral grains (Needham, Reference Needham1934; Stephenson and Monroe, Reference Stephenson and Monroe1940; Raymond et al., Reference Raymond, Osborne, Copeland and Neathery1988; Mancini and Soens, Reference Mancini and Soens1994; Becker et al., Reference Becker, Slattery and Chamberlain1998). Locally, portions of the unit contain beds of calcareous sandstone and sandy chalk (Raymond et al., Reference Raymond, Osborne, Copeland and Neathery1988). The Tombigbee Sand is noted for its transgressive lag deposits, which typically contain quartz pebbles, phosphate grains, pyrite and siderite nodules, and numerous fossils (Stephenson and Monroe, Reference Stephenson and Monroe1940; Mancini and Soens, Reference Mancini and Soens1994).

The contact of the Tombigbee Sand Member with the lower Eutaw Formation is represented by an erosional unconformity and lag deposit, whereas the contact with the overlying Mooreville Chalk is a gradational shift from sand to chalk. Although the contact with the Mooreville Chalk is gradational, it may be indicated locally by a layer of phosphatic pebbles and mollusk steinkerns (Mancini and Soens, Reference Mancini and Soens1994). Liu (Reference Liu2007) arbitrarily placed the Mooreville contact at the level where the sand attains a chalk content of 50%. The age of the Tombigbee-Mooreville contact is diachronous, being earliest Campanian in east-central Mississippi and ranging to the mid-Santonian in central Alabama (Mancini et al., Reference Mancini, Puckett and Tew1996). As the lower Mooreville Chalk is exposed a short distance downstream from the outcropping Tombigbee Sand where ALMNH 8723 was collected, the upper contact in western Alabama at AGr-43 is believed to be close to the Santonian-Campanian boundary. Although ALMNH 8723 was collected out of stratigraphic position from riverbed gravel, the very dark coloration of the specimen (Fig. 1.1, 1.2) suggests that it is almost certainly derived from the Tombigbee Sand rather than the overlying Mooreville Chalk, as fossils from the Mooreville Chalk tend to be tan or light brown in color and are more delicately preserved.

The upper Tombigbee Sand Member of the Eutaw Formation contains a diverse and well-known vertebrate macrofaunal assemblage dominated by isolated elasmobranch teeth (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Slattery and Chamberlain1998; Ciampaglio et al., Reference Ciampaglio, Cicimurri, Ebersole, Runyon, Ebersole and Ikejiri2013). Other common marine vertebrate fossils include teeth and vertebrae of fish, rostral denticles and teeth of sawfish and rays, shell fragments of marine chelonioid turtles, mosasaur teeth and bones, and rare elasmosaur teeth and bones (Thurmond and Jones, Reference Thurmond and Jones1981; Becker et al., Reference Becker, Slattery and Chamberlain1998; Manning, Reference Manning2006; Becker et al., Reference Becker, Seidemann, Chamberlain, Buhl and Slattery2008; Konishi et al., Reference Konishi, Caldwell and Bell2010; Ciampaglio et al., Reference Ciampaglio, Cicimurri, Ebersole, Runyon, Ebersole and Ikejiri2013; Ikejiri et al., Reference Ikejiri, Ebersole, Blewitt, Ebersole, Ebersole and Ikejiri2013). A smaller, but still significant, portion of the fauna of the Tombigbee Sand in general is represented by freshwater and terrestrial vertebrate remains, including trionychid turtle shell fragments, gar scales and teeth, crocodile teeth and osteoderms, and rare dinosaur bones (Kaye and Russell, Reference Kaye and Russell1973; Schein and Lewis, Reference Schein and Lewis2007; Ebersole and King, Reference Ebersole, King, Parham and Ebersole2011; Ikejiri et al., Reference Ikejiri, Ebersole, Blewitt, Ebersole, Ebersole and Ikejiri2013; Jasinski, Reference Jasinski, Ebersole and Ikejiri2013). The vertebrate fossil assemblage at AGr-43 includes some temporal mixing of reptiles and mammals derived from the late Pleistocene deposits that immediately overlie the Cretaceous Eutaw Formation at that location. According to ALMNH records, these contaminants include the fragmentary remains of proboscideans, horses, bison, tapirs, tortoises, and a variety of freshwater turtles.

Invertebrate macrofossils in the Tombigbee Sand are equally as diverse as vertebrates; however, heavier-valved mollusks tend to be better preserved than their thin-shelled counterparts. Larger oysters dominate the invertebrate fauna (Stephenson and Monroe, Reference Stephenson and Monroe1940), likely due to preservational bias attributable to their thick shells. Other bivalves from the unit include inoceramids, mactrids, anomiids, and pectinids (Stephenson and Monroe, Reference Stephenson and Monroe1940; Phillips, Reference Phillips2011). Although the Tombigbee Sand bivalves have been largely neglected by recent researchers, ammonite research is more extensive and reports the presence of Texanites (Plesiotexanites) shiloensis Young, Reference Young1963, Placenticeras syrtale (Morton, Reference Morton1834), Scaphites leei Reeside, Reference Reeside1927 (form I) Cobban, Reference Cobban1969, Pseudoschloenbachia mexicana (Renz, Reference Renz1936), Reginaites leei (Reeside, Reference Reeside1927), Reginaites exilis Kennedy and Cobban, Reference Kennedy and Cobban1991, Boehmoceras arculus (Morton, Reference Morton1834), Glyptoxoceras sp. Spath, Reference Spath1925, and Hyphantoceras (?) amapondense (Hoepen, Reference Hoepen1921) in the lower portion of the unit (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Cobban and Landman1997). This lower Tombigbee Sand ammonite faunal assemblage was assigned to the uppermost Santonian Texanites (Plesiotexanites) shiloensis zone of the Gulf Coast sequence and correlated with the upper Santonian Desmoscaphites erdmanni Cobban, Reference Cobban1951 Zone of the U.S. Western Interior Seaway (WIS) (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Cobban and Landman1997). Other notable invertebrates from the Tombigbee Sand include the Santonian crinoids Uintacrinus socialis Grinnell, Reference Grinnell1876, and Marsupites testudinarius (Schlotheim, Reference Schlotheim1820) (Stephenson and Monroe, Reference Stephenson and Monroe1940; Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Cobban and Landman1997; Ciampaglio and Phillips, Reference Ciampaglio and Phillips2007). Several layers in the Tombigbee Sand contain unidentified gastropods and bivalves represented by steinkern fragments.

Numerous micropaleontological studies have been conducted on the Tombigbee Sand in the interest of biostratigraphic correlation and sequence stratigraphy of the Gulf Coastal Plain. A previous study of the foraminifera determined that the Tombigbee Sand near AGr-43 is situated within the Dicarinella asymetrica (Sigal, Reference Sigal1952) Total Range Zone, where it co-occurs with the Globotruncanita elevata (Brotzen, Reference Brotzen1934) Interval Zone near the Tombigbee Sand–Mooreville Chalk contact (Mancini et al., Reference Mancini, Puckett and Tew1996). The presence of these two zones places the strata at AGr-43 close to the Santonian-Campanian boundary (Smith and Mancini, Reference Smith, Mancini, Russell, Keady, Mancini and Smith1983; Mancini and Soens, Reference Mancini and Soens1994; Mancini et al., Reference Mancini, Puckett and Tew1996; Puckett, Reference Puckett2005). Ostracode biostratigraphy places the boundary near AGr-43 between the Veenia quadrialira (Swain, Reference Swain1952) Interval Zone (middle Santonian–late Santonian) and the Pterygocytheresis cheethami (Hazel and Paulson, Reference Hazel and Paulson1964) Interval Zone (late Santonian–middle Campanian) (Puckett, Reference Puckett1994; Mancini et al., Reference Mancini, Puckett and Tew1996), whereas the nannofossil assemblage places the site near the boundary of the Calculites obscurus (Deflandre, Reference Deflandre1959) and Aspidolithus parcus (Stradner, Reference Stradner1963) zones (CC17–CC18) (Dowsett, Reference Dowsett1989; Mancini et al., Reference Mancini, Puckett and Tew1996).

Luxapallila Creek

According to G. Phillips at MMNS (personal communication, 2017), prior to riparian reclamation, the Luxapallila Creek locality in Mississippi consisted of a lengthy exposure of dominantly clay and sandy clay beds as well as cross-bedded sands of the lower Eutaw Formation. Within the channel walls, a relatively thin, clastic, vertebrate-rich layer is overlain and underlain by micaceous, thinly laminated clays with thinner lignite interlaminae, or carbonaceous films traditionally associated with the lower Eutaw (Stephenson and Monroe, Reference Stephenson and Monroe1940; Kaye, Reference Kaye1955; Wahl, Reference Wahl1966; Soens, Reference Soens1984; Rindsberg and Puckett, Reference Rindsberg and Puckett1997). The bounding shale beds have few detectable macrofauna, and the subjacent shale is replaced laterally upstream by cross- and flaser-bedded sands. Along much of its outcrop area, thinly laminated micaceous, lignitic shale immediately underlies the lag deposit. Where these laminated clay beds have been eroded to reveal horizontal surfaces, the clay laminae frequently exhibit ripples. A whitish to reddish yellow-brown claystone layer, 5 to 8 cm thick, lies within the laminated clays between 55 and 70 cm beneath the base of the macrofossil lag. The claystone ranges from a near continuous mass to very discontinuous separate entities, the latter instance consisting (at two locations in the study area) of discrete toroidal, bed-parallel claystone bodies averaging 18 cm in diameter. At the northernmost point of the outcropping lag layer, the subjacent thinly laminated clays (above the claystone bed) are replaced laterally by a large localized lens of thin, interlaminated quartz sands and comminuted lignite, forming planar beds, wavy (flaser) beds, and low-angle cross-beds. Larger lignitized plant debris, from pebble size to logs, interrupts bedding in various places. The well-defined macrofossil bed averages ~0.5 m thick and is exposed along a 1.3 km stretch of the creek, where it was uncovered in the late 1990s during a channelization project to alleviate flooding in east Columbus, Mississippi. The generally fining-upward bed constitutes a marginal marine lag with one (or more) sideritized zones composing the base and representing a major surface (or surfaces). Due in part to its species composition, the fossiliferous lag is treated as age equivalent to the basal bed of the Tombigbee Sand as it rests on a major disconformable surface. The superjacent clay bed is estimated to be between 7 and 10 m thick and lies beneath beds more typical of the upper Tombigbee Sand Member (e.g., Stephenson and Monroe, Reference Stephenson and Monroe1940; Kaye, Reference Kaye1955; Soens, Reference Soens1984) located ~4.8 km downstream from the Luxapallila Creek site. A comparable upper Eutaw section to that in Luxapallila Creek where a similar vertebrate-rich lag is not immediately attached to or associated with the typical Tombigbee Sand lithology was measured and illustrated by Soens (Reference Soens1984, App. 1 and 2, locality CS-Miss 79-63/columnar section Y). There, the lag was separated from the Tombigbee Sand by ~10 m.

The vertebrate fossil content at MS.44.001 was first mentioned by Kaye (Reference Kaye1955), who was reporting on the geology of Lowndes County, Mississippi. The discussion was very brief and based on anecdotal information from a Columbus resident who found abundant shark teeth in the Luxapallila channel, although the source bed was never located. The specific provenance provided in that account coincides approximately with the south end of the present Luxapallila locality. The vertebrate fossil content consists of an ecologically disparate mix of various terrestrial, freshwater, brackish-water, and marine taxa. Identified vertebrate specimens from the site consist primarily of chondrichthyan and osteichthyan taxa (Cicimurri et al., Reference Cicimurri, Ciampaglio and Runyon2014). Reptile remains are less common and include crocodiles, mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, trionychid and chelonioid turtle shell fragments, and teeth and bones of both theropod and ornithischian dinosaurs (Cicimurri et al., Reference Cicimurri, Ciampaglio and Runyon2014; Dockery and Thompson, Reference Dockery and Thompson2016). No articulated bones have been observed in situ at the site. In addition, bone, teeth, and coprolites, as well as lithified wood, all show evidence of abrasive transport consistent with having been preserved elsewhere and reworked into the existing coarse lag. Most bones are reduced to fragments, but whole pedal elements of dinosaurs (for example) have been recovered (Dockery and Thompson, Reference Dockery and Thompson2016).

Invertebrate fossils in the lower Eutaw Formation at MS.44.001 are scarce and poorly preserved. Most specimens are fragmentary molds in the poorly indurated base of the fossil bed. Cicimurri et al. (Reference Cicimurri, Ciampaglio and Runyon2014) reported possible specimens of the crab Pagurus convexus Whetstone and Collins, Reference Whetstone and Collins1982, a callianassid shrimp, two unidentified gastropod species, one unidentified species of bivalve, cephalopod tentacle hooklets, and weathered echinoderm plates. No microfossils have been reported to date from the Luxapallila site.

Depositional environments

The Eutaw Formation (including the Tombigbee Sand) was deposited early in a marine transgression within the Mississippi Embayment. Mancini et al. (Reference Mancini, Puckett, Tew and Smith1995) assigned both members to the UZAGC-3.0 depositional sequence within the Mississippi Embayment, with the lower member representing the lowstand systems tract and the Tombigbee Sand representing the first transgressive surface (lower Eutaw–Tombigbee contact) and transgressive systems tract. Mancini and Puckett (Reference Mancini, Puckett, Armentrout and Rosen2002) later referred this depositional sequence to Cycle Six of a broader intrabasinal correlation of transgressive-regressive cycles in the northern Gulf of Mexico Basin.

The depositional environments suggested by the Tombigbee Sand lithology at Trussells Creek range from tidally influenced, paralic associations at the base of the unit to more offshore barrier to inner shelf environments near the contact with the overlying Mooreville Chalk (Needham, Reference Needham1934; King and Skotnicki, Reference King and Skotnicki1994; Mancini and Soens, Reference Mancini and Soens1994; Mancini et al., Reference Mancini, Puckett and Tew1996). The majority of the Cretaceous fossils at the Trussells Creek site in Alabama are believed to be derived from the lag deposit at the base of the unit; thus, the depositional environment of ALMNH 8723 is likely nearshore marine. However, it is uncertain whether the terrestrial and fluvial vertebrate materials present in the Tombigbee Sand were delivered from nearby river deltas during the Late Cretaceous, were reworked from the underlying strata during the marine transgression, or are a combination of both.

The depositional environments in the Eutaw Formation at the Luxapallila Creek site are slightly more complex. The thinly interlaminated clay-lignite beds are replaced (at least at one location) by a large lens of variably bedded interlaminated sand-lignite layers that likely represent back-barrier, lagoonal tidal mud flats incised by sandy tidal creeks. Furthermore, the faunal assemblage composition of the site is seemingly very telling of the originating environment. The scarcity of large pelagic species, namely mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and large-bodied sharks, suggests that offshore origin for any portion of the Luxapallila lag deposit is unlikely.

Materials and methods

The anatomical terminology used to describe the tooth plate specimens in this study largely follows that of Kirkland (Reference Kirkland1987), whereas the biometric units used are those developed by Vorob'yeva and Minikh (Reference Vorob'yeva and Minikh1968) in the interest of comparison with most previous studies. Biometric features of the fossils were determined by photographing the occlusal surface of each specimen with a digital camera and importing the images into Adobe Illustrator, where points of measurement and angle rays were marked. The images were then printed, and measurements were obtained using a protractor for angles and analog caliper for distances. As the biometric measurements consist of angles and ratios, the scale of the printed images was inconsequential. Measurements were recorded in an Excel spreadsheet and compared with measurements of similar species (Table 1) obtained from various sources. The length, width, and thickness of the specimens described here were obtained by direct measurement of the fossils using an analog caliper.

Table 1. Biometric measurements of Ceratodus frazieri (ALMNH 8723) and Ceratodus carteri (MMNS VP-3440) in comparison with measurements obtained from other referred specimens of each species. Measurements of Potamoceratodus guentheri included for comparison with MMNS VP-3440. Measurements followed by an asterisk are estimated due to specimen damage. <ABC = angle between mesial and lingual borders; <C1CP = angle between ridges C1 and CP; <C2CP = angle between ridges C2 and CP; <C3CP = angle between ridges C3 and CP; remaining columns represent ratios of various line segments (see Fig. 4). 1Measurements obtained by photographing specimen or using published photographs with angles and measuring points determined by the authors of this study. 2Measurements obtained from Kirkland (Reference Kirkland1987, table 1). 3Measurements obtained using published diagram of specimen in Parris et al. (2004, fig. 2). 4Measurements obtained using published diagrams of specimens in Main et al. (2014, fig. 2B–F; note: figure 2C in Main et al., Reference Main, Parris, Grandstaff and Carter2014 was incorrectly diagrammed with crests in the opposite order, which was corrected in the measurements presented here; see Systematic paleontology section for equivalent UTA specimen numbers).

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

Institutional abbreviations used in this study are as follows: ALMNH = Alabama Museum of Natural History, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, USA; BYU = Paleontological Collections, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA; DMNH = Perot Museum of Nature and Science, Dallas, Texas, USA; KUVP = University of Kansas Natural History Museum, Lawrence, Kansas, USA; MOR = Museum of the Rockies, Bozeman, Montana, USA; MMNS = Mississippi Museum of Natural Science, Jackson, Mississippi, USA; NJSM = New Jersey State Museum, Trenton, New Jersey, USA; OMNH = Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, Norman, Oklahoma, USA; SDSM = South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, Rapid City, South Dakota, USA; SMU = Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas, USA; USNM = United States National Museum, Washington, District of Columbia, USA; UTA = University of Texas-Arlington, Arlington, Texas, USA; YPM = Yale Peabody Museum, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Systematic paleontology

Class Sarcopterygii Romer, Reference Romer1955

Subclass Dipnoi Müller, Reference Müller1844

Order Ceratodontiformes Berg, Reference Berg1940

Family Ceratodontidae Gill, Reference Gill1872

Genus Ceratodus Agassiz, Reference Agassiz1838

Type species

Ceratodus latissimus Agassiz, Reference Agassiz1838

Ceratodus frazieri Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1970

Figures 1.1, 1.2, 3, 4.2; Table 1

1970 Ceratodus frazieri Ostrom, p. 53, pl. 8B, 9A.

Figure 3. SEM scans of occlusal surface of ALMNH 8723 showing denteon pattern and structure at (1) 58× magnification (scale bar = 1 mm) and (2) 608× magnification (scale bar = 100 mm). Area indicated in scan (1) is the region magnified in scan (2). The tooth plate was not coated prior to scanning in order to preserve the integrity of the specimen.

Figure 4. (1) Biometric diagram of generalized lungfish tooth plate showing anatomical directions modified from Kirkland (Reference Kirkland1987). Biometric diagrams of (2) ALMNH 8723 and (3) MMNS VP-3440 showing occlusal surface measurement points. AB = line segment representing mesial border; BC = line segment representing lingual border; B = approximate point of origination of the occlusal ridges; C1 = terminal point of first ridge; C2 = terminal point of second ridge; C3 = terminal point of third ridge; CP = terminal point of fourth ridge. Measurements are listed in Table 1.

Holotype

Left prearticular tooth plate (YPM 5276), Early Cretaceous, Unit V (of Ostrom) ~15.2 meters below Unit VI, Cloverly Formation; NW1/4, Section 34, T58N, R95W, Big Horn County, Wyoming, USA.

Diagnosis

(After Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1970.) Tooth plate large, broad, and thin with four broad, nontuberculated radial ridges. Radial ridges are not sharp crested distally as they are in Potamoceratodus guentheri (Marsh, Reference Marsh1878) and do not extend to the medial margin of the plate. Laterally, the ridges end in broad projections separated by shallow notches. The anterior ridge is the largest and ends in the longest distal projection. The posterior ridge is very faint and terminates distally in a very slight lateral projection. The radial ridges are so subdued (apparently by excessive wear) that the typical ceratodontid radiating pattern is not clear, except near the lateral margin. Medial margin is broadly rounded and not angled as in most other ceratodontids.

Occurrence

Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian–Tithonian?) uppermost Morrison Formation, South Dakota and Oklahoma, USA; Early Cretaceous (Aptian–Albian) Cloverly Formation, Montana and Wyoming, USA; Early Cretaceous (Albian) Kiowa Formation, Kansas, USA; Late Cretaceous (Santonian) Eutaw Formation, Alabama, USA; Late Cretaceous (Campanian) Mount Laurel Formation, New Jersey, USA

Materials

YPM 5276 (holotype); KUVP 16262 (Schultze, Reference Schultze1981); SDSM 426, MOR 367 (Kirkland, Reference Kirkland1987); OMNH 04033 (Kirkland, Reference Kirkland1998, as Ceratodus cf. C. frazieri); NJSM 18774 (Parris et al., Reference Parris, Grandstaff and Gallagher2004, as Ceratodus aff. C. frazieri); USNM 546680, USNM 547214, USNM 546249, USNM 546795 (Oreska et al., Reference Oreska, Carrano and Dzikiewicz2013); OMNH 60408 (Frederickson and Cifelli, Reference Frederickson and Cifelli2017); ALMNH 8723 (herein).

Remarks

ALMNH 8723 is identified as a right prearticular (lower) tooth plate of Ceratodus frazieri. The Alabama specimen consists of a single complete but heavily worn tooth plate, with no bone material preserved on the aboral surface (Fig. 1.1, 1.2). In occlusal view, the tooth plate generally appears broad and subrectangular in outline. Its dimensions measure 37.9 mm in length, 19.6 mm at the widest point, and 6.8 mm in maximum thickness, with a smooth occlusal surface lacking any sharp transverse ridges. Laterally projecting points or crests at the labial margin of the tooth plate suggest that four, or possibly five, transverse ridges were present on the occlusal surface prior to wear. The lingually directed intercrest invaginations or notches along the labial margin are comparatively shallow and arc smoothly from crest to crest. The notch between C1 and C2 is deepest, with each successive notch becoming shallower. The notch between C3 and CP is weakly developed and there is almost no notch between crests four (CP) and a possible fifth crest. The mesial-lingual margin of the tooth plate is smooth and broadly rounded. The tooth plate is somewhat curved toward the occlusal surface, giving that surface a slightly concave shape.

In addition to a network of microscopic punctations (denteons), both occlusal and aboral surfaces are covered by shallow subcircular depressions arranged in an irregular pattern indicating areas of harder and softer material. Scanning electron micrographs (SEM) of the tooth plate occlusal surface (Fig. 3.1) reveal the denteons to be simple rounded pits, most of which are filled by a material alternatively called secondary dentine (Parris et al., Reference Parris, Grandstaff and Gallagher2004) or impacted hard material from abrasion of the tooth (Kemp, Reference Kemp2001). Ring-like fractures are present in the material filling some of the denteons (Fig. 3.2) and likely are the result of diagenetic alteration.

Biometric analysis (Fig. 4.2, Table 1) was conducted on ALMNH 8723 to determine ridge crest angles and other measurement ratios. However, the biometric method of Vorob'yeva and Minikh (Reference Vorob'yeva and Minikh1968), which has been invoked repeatedly in the literature, is somewhat subjective and confusing in the precise placement of the common vertex, or “apex of the inner angle” as used by Martin et al. (Reference Martin, Barbieri and Cuny1999). Nevertheless, the present authors used this biometric method to allow comparison with previous studies, and the results of the current study are presented in Table 1. The angle between the lingual and mesial borders (<ABC) of ALMNH 8723 is broadly obtuse (149°) whereas the angles between C1 and CP on the occlusal surface are contained within 90° of CP . No single ridge is separated from an adjacent ridge by more than 33°. These tooth plate measurements are comparable with specimens of Ceratodus frazieri reported from North America (Kirkland, Reference Kirkland1987; Parris et al., Reference Parris, Grandstaff and Gallagher2004; Frederickson and Cifelli, Reference Frederickson and Cifelli2017).

Ceratodus carteri Main et al., Reference Main, Parris, Grandstaff and Carter2014

Figures 1.3, 1.4, 4.3; Table 1

2014 Ceratodus carteri Main et al., p. 290, fig. 2

Holotype

Right pterygopalatine tooth plate (DMNH 2013-07-0778, formerly UTA-AASL 006), Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian), Woodbine Formation, Arlington, Tarrant County, Texas, USA. Paratype—left prearticular tooth plate (DMNH 2013-07-0774, formerly UTA-AASL 001), Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian), Woodbine Formation, Arlington, Tarrant County, Texas, USA.

Diagnosis

(Modified from Main et al., Reference Main, Parris, Grandstaff and Carter2014.) Five ridge crests on the pterygopalatine (upper) tooth plate and four on the prearticular (lower) tooth plate. Tooth plates have high, sharp ridge crests, obtuse inner angles, and relatively straight lingual margins. Lacks a flattened crushing platform associated with the third and fourth crests like that present in Potamoceratodus guentheri.

Occurrence

Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian) Woodbine Formation, Texas, USA; Late Cretaceous (Santonian) Eutaw Formation, Mississippi, USA.

Materials

DMNH 2013-07-0778 (UTA-AASL 006) (holotype), DMNH 2013-07-0774 (UTA-AASL 001) (paratype), DMNH 2013-07- 0775 (UTA-AASL 002), DMNH 2013-07-0776 (UTA-AASL 003), DMNH 2013-07-0777 (UTA-AASL 004), DMNH 2013-07-0779 (UTA-AASL 007), SMU 73202 (Main et al., Reference Main, Parris, Grandstaff and Carter2014); MMNS VP-3440 (herein). Specimens housed at the University of Texas-Arlington (UTA) were transferred to the Perot Museum of Nature and Science (DMNH) in July 2013.

Remarks

Manning (Reference Manning2006) first reported the occurrence of the Mississippi lungfish specimen in his dissertation; however, it was never published formally and the current report is a more detailed comparative, diagnostic description. MMNS VP-3440 (Fig. 1.3, 1.4) is a partial right prearticular (lower) bearing most of a tooth plate that is here referred to Ceratodus carteri. Much of the symphyseal region of the prearticular is present, but the caudal process is completely absent. The anteroventral surface of the element is considerably eroded, and there is loss of the labial extremities of all occlusal ridges of the tooth plate except the second. The preserved dimensions of MMNS VP-3440 measure 25.5 mm in length, 27.5 mm in width, and ~11.0 mm in thickness. Although the posterior portion is missing, the tooth plate is estimated to have been between 31.0 and 35.0 mm in length based on comparison with known specimens of C. carteri. The thickness of the tooth plate had to be approximated due to the presence of the attached bone material. Ruge's ridge (usage of Martin Reference Martin, Buffetaut, Janvier, Rage and Tassy1982; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Barbieri and Cuny1999) is barely visible ventrally beneath the anteriormost inter-ridge notch. The predepositional erosion has revealed the pulp cavities of all ridges. Four occlusal ridges radiate from an inner angle (usage of Vorob'jeva and Minikh, Reference Vorob'yeva and Minikh1968; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Barbieri and Cuny1999, and so on). The fourth (CP) ridge is severely truncated due to erosion. Ridge one is sharp compared to the other ridges, and this is accentuated by the deep first intercrest notch and steep mesial edge. There is a nearly equally deep, lingually invaginated notch between C2 and C3, and although the more posterior ridges are incomplete, the inter-ridge notches become increasingly shallower moving distally, producing a relatively flat surface at the lingual origins of the posterior ridges. Ridges C3 and CP (which is incomplete) are separated by a subtle notch. The peaks of all ridges exhibit an attritional wear, and the ridges tend to bow slightly distally, although C1 is nearly straight. The intact ridges are cuspless, except for the lingual termination of C2, which has a small, single, relatively sharp cusp. Cusps were likely present on the labial extremities of the other ridges, which are missing.

The occlusal surface of MMNS VP-3440 is composed of compound dentine (interdenteonal and circumdenteonal dentines) densely populated with microscopic, evenly distributed punctations representing the surface expression of denteons; however, remnants of the mantle layer are found along the lower margins of C1 and C2. The denteons are of consistent size and evenly distributed about the occlusal surface. No SEM scans were made of MMNS VP-3440 as the specimen was unavailable at that time.

As mentioned, the biometric method developed by Vorob'yeva and Minikh (Reference Vorob'yeva and Minikh1968) is somewhat subjective in the placement of the requisite landmarks on the tooth plate surface. The method of Kemp (Reference Kemp1977) and Kemp and Molnar (Reference Kemp and Molnar1981) requires straight ridges for establishing the sides of (and thus measuring) inter-ridge angles. Due to the slight distal bowing in C2 through CP of MMNS VP-3440, placement of the sides of the inter-ridge angles was approximated in the Mississippi specimen (Fig. 4.3, Table 1). This bowing is also mirrored in the convexity of the lingual edge. Damage to the labial end of CP also necessitates that the remaining angles be estimated relative to that ridge using the measurement format of Vorob'yeva and Minikh (Reference Vorob'yeva and Minikh1968). The inter-ridge angles of C1 through C3 are still of some descriptive value. The angle between the lingual and mesial borders (<ABC) of MMNS VP-3440 is slightly obtuse (108°) whereas the angles between C1 through CP on the occlusal surface are contained within ~71° of the estimated fourth ridge (CP). The calculated angles obtained in this analysis are comparable to those of Ceratodus carteri (Main et al., Reference Main, Parris, Grandstaff and Carter2014) and Potamoceratodus guentheri (Kirkland et al., Reference Kirkland1987 as ‘Ceratodus’ felchi).

Discussion

The taxonomic assignment of lungfish tooth plates is problematic because families and genera are defined in various ways by different authors. Although biometric analysis can aid in identification by providing a range of measurements for a given taxon, the range of measurements sometimes overlaps with other taxa (Kemp and Molnar, Reference Kemp and Molnar1981; Kirkland, Reference Kirkland1987). In addition, post-Triassic lungfish discoveries constituting skeletal remains other than tooth plates are very rare (Pardo et al., Reference Pardo, Huttenlocker, Small and Gorman2010). This is due in part to preservational bias, specifically a general reduction in skeletal ossification over time, accompanied by a concomitant increase in mineralization of tooth plates within several lineages (Cavin et al., Reference Cavin, Suteethorn, Buffetaut and Tong2007). This is complicated by the fact that over half of the described species are based on isolated tooth plates or other fragmentary remains (Marshall, Reference Marshall1987). Specific assignment is further frustrated by ontogenetic variation and the near global distribution of certain conservative tooth plate morphologies such as those exhibited by ALMNH 8723 and MMNS VP-3440 (Smith and Krupina, Reference Smith and Krupina2001; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Krupina and Joss2002; Pardo et al., Reference Pardo, Huttenlocker, Small and Gorman2010). Other researchers (Kirkland Reference Kirkland1987, Reference Kirkland1998; Frederickson and Cifelli, Reference Frederickson and Cifelli2017) faced these same problems when dealing with isolated tooth plates from the late Mesozoic of the North American Western Interior. Frederickson and Cifelli (Reference Frederickson and Cifelli2017) developed a system of phenetically based species groups (morphotypes) for Mesozoic ceratodontid lungfish due to the considerable intraspecific variation in tooth plate morphologies and because similar morphologies are present in specimens separated by vast time intervals and geographic distances. They expanded upon the system of Martin (Reference Martin, Buffetaut, Janvier, Rage and Tassy1982; see also Kirkland, Reference Kirkland1987; Parris et al., Reference Parris, Grandstaff and Banks2014) in which tooth plates are divided into two primary types: ‘Ceratodont’ for flat, crushing dentitions, and ‘Ptychoceratodont’ for sharp-crested, cutting (sectorial) dentitions. These two primary types were then subdivided into four morphospecies based on lungfish taxa that are present in the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation of the Western Interior. Despite the difficulties in taxonomic assignment of isolated lungfish tooth plates, efforts were made by the present authors to identify the Alabama and Mississippi specimens using a combination of their morphologic and biometric features.

In comparison with other North American Mesozoic lungfish tooth plates, the Alabama specimen fits within the ‘ceratodont’ morphotype division described in the preceding as its flat occlusal surface appears to be ideally suited for crushing thin-shelled mollusks. ALMNH 8723 compares well morphologically with a lower tooth plate (OMNH 60408) from the Early Cretaceous Cloverly Formation of Montana that was referred to Ceratodus frazieri by Frederickson and Cifelli (Reference Frederickson and Cifelli2017, p. 149, fig. 12). ALMNH 8723 also compares favorably with an upper tooth plate (KUVP 16262) assigned to C. frazieri by Schultze (Reference Schultze1981, p. 190, fig. 1) from the Early Cretaceous Kiowa Formation of Kansas. The Alabama specimen is similar to these two tooth plates in the degree of the inner angle (<ABC), the relatively broad, flat occlusal surface, the very shallow notches along the labial margin, and the shape of the posterior-lingual margins. Interestingly, the Alabama specimen compares less favorably from a morphological standpoint with the holotype of C. frazieri (YPM 5276) than it does with the preceding referred specimens. The primary difference is in the angles of ridges C1 and C2, which are projected more anteriorly in YPM 5276 and directed more laterally (labially) in ALMNH 8723. The notches on the labial margin are also deeper in YPM 5276 than they are in the Alabama specimen. Biometrically, ALMNH 8723 shares differences and similarities with YPM 5276. The ridge angles (C1–C3) are wider relative to the CP ridge in YPM 5276 than in ALMNH 8723 although the inner angle (<ABC) is similarly very wide in both specimens (Table 1). The remaining biometric ratios are comparable between ALMNH 8723 and YPM 5276, as well as the other referred specimens of C. frazieri. The length/width/thickness ratio of the Alabama specimen (5.6/2.9/1.0) compares favorably with that of the holotype of C. frazieri (5.9/2.8/1.0), although the dimensions of both specimens may be affected by wear. Furthermore, the masticatory wear of ALMNH 8723 may have been significantly enhanced by ablation that resulted from rolling during postmortem transport.

ALMNH 8723 is comparatively smaller than the other referred specimens of C. frazieri. It is unknown whether this smaller size represents a younger ontogenetic stage (which seems unlikely given the considerable wear on the occlusal surface), individual variation, or sexual dimorphism or may be characteristic of a new taxon. A specimen referred to C. frazieri from the Morrison Formation in Oklahoma (OMNH 60408) is similarly smaller than typical specimens of this species. The smaller size of OMNH 60408, along with other subtle morphological differences, may prove that specimen to be a species distinct from C. frazieri (R. Cifelli, personal communication, 2018).

The Alabama specimen also compares well biometrically with lower tooth plate measurements of the ‘ptychoceratodont’ Ceratodus fossanovum (Kirkland, Reference Kirkland1987; Table 1 as ‘C. guentheri’; see Kirkland, Reference Kirkland1998 for explanation). However, ALMNH 8723 differs considerably from C. fossanovum in the height of the transverse ridges and depth of the labial notches. The Alabama specimen does not compare favorably with the members of the C. robustus morphospecies group of Frederickson and Cifelli (Reference Frederickson and Cifelli2017), in that tooth plates of those species (C. robustus Knight, Reference Knight1898 and C. molossus Frederickson and Cifelli, Reference Frederickson and Cifelli2017) are much broader and more massive than that of ALMNH 8723.

Due to the morphological and biometric similarities discussed, ALMNH 8723 is referred to Ceratodus frazieri. However, the authors here concur with Parris et al. (Reference Parris, Grandstaff and Gallagher2004) that Late Cretaceous material referred to C. frazieri from eastern North America, while characteristically similar to the holotype, may warrant the designation of new species pending the discovery of diagnostic cranial material because of the geographic and stratigraphic separation from the mid-Cretaceous C. frazieri specimens of the Western Interior (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1970; Schultze, Reference Schultze1981; Kirkland, Reference Kirkland1987; Frederickson and Cifelli, Reference Frederickson and Cifelli2017).

Early identification attempts of MMNS VP-3440 were similarly difficult. Damage to the distal end of the fourth ridge (CP) in MMNS VP-3440 required that most of the biometric measurements be estimated, which complicated comparisons with other lungfish taxa. However, the recent discovery of a lungfish skull from the Morrison Formation of Colorado (Pardo et al., Reference Pardo, Huttenlocker, Small and Gorman2010) partially clarified North American Mesozoic lungfish taxonomy. Several closely related tooth plate forms reported from mid-Cretaceous sites in the Western Interior (Main et al., Reference Main, Parris, Grandstaff and Carter2014; Parris et al., Reference Parris, Grandstaff and Banks2014) are morphologically, geographically, and stratigraphically closer to MMNS VP-3440 than any previously published material.

In contrast to ALMNH 8723, the Mississippi tooth plate possesses high cutting ridges of the ‘ptychoceratodont’ morphotype of Frederickson and Cifelli (Reference Frederickson and Cifelli2017) and others. Morphologically, MMNS VP-3440 compares favorably with a left lower tooth plate (USNM 323006a) assigned to Ceratodus felchi by Kirkland (Reference Kirkland1987, fig. 3G) from the Jurassic Morrison Formation of Colorado. This Late Jurassic specimen was later referred (Kirkland, Reference Kirkland1998) to C. guentheri and finally reassigned to Potamoceratodus guentheri by Pardo et al. (Reference Pardo, Huttenlocker, Small and Gorman2010) in their description of that new genus. Aside from the morphological similarity that includes sharp cutting ridges and deep labial notches, MMNS VP-3440 also shares similar geometry of the inner angle and crest angles with USNM 323006a (Table 1). A more plausible candidate for the Mississippi tooth plate is Ceratodus carteri, a recently named species from the mid-Cretaceous (Cenomanian) of Texas that is very similar to the older Potamoceratodus guentheri (Main et al., Reference Main, Parris, Grandstaff and Carter2014). The differences between C. carteri and P. guentheri noted by Main et al. (Reference Main, Parris, Grandstaff and Carter2014) were that tooth plates are larger in C. carteri and that there is no flattened crushing platform associated with the third and fourth ridges (C3–CP) in C. carteri. The distal portion of CP is missing in MMNS VP-3440, but the proximal portion is separated from C3 by a furrow as is the case reported for C. carteri, rather than being combined into a crushing platform as in P. guentheri. Biometrically, MMNS VP-3440 is comparable with specimens of C. carteri in the degree of inner angle (<ABC) and ridge angles and has more affinities with its biometric ratios than it has with P. guentheri (Table 1). Conversely, the Mississippi tooth plate is nearly twice as large as the known specimens of C. carteri, although this too may be attributable to ontogeny or perhaps could be an example of evolutionary increase in body size over time. In addition, the C2 and C3 in MMNS VP-3440 are bowed anteriorly like that present in C. nirumbee Frederickson and Cifelli, Reference Frederickson and Cifelli2017 (Frederickson and Cifelli, Reference Frederickson and Cifelli2017, fig. 2.8). However, in other species such as C. kirklandi Frederickson and Cifelli, Reference Frederickson and Cifelli2017, the posterior ridges on tooth plates of the same anatomical position may bow either anteriorly or posteriorly (Frederickson and Cifelli, Reference Frederickson and Cifelli2017, fig. 3.7, 3.8). This suggests that the direction of ridge bowing may be a matter of individual variation. MMNS VP-3440 differs from the members of the similar C. fossanovum morphospecies group of Frederickson and Cifelli (Reference Frederickson and Cifelli2017), including C. fossanovum and C. nirumbee, which generally have more obtuse inner angles, lower ridge crests, and well-developed crushing platforms at various points along the mesial-lingual margins. It is for these reasons that MMNS VP-3440 is referred to Ceratodus carteri although, as is the case with ALMNH 8723, the possibility exists that it may be referred to a new species if more diagnostic cranial material is discovered in the Eutaw Formation.

For many years the fossil record of Mesozoic lungfishes in North America was restricted to the Western Interior and to strata older than the mid-Cretaceous (Kirkland, Reference Kirkland1987). Kirkland also noted the occurrence of a tooth plate from the Cenomanian Woodbine Formation of northeastern Texas but did not describe the specimen. Subsequent discoveries extended the temporal range of western North American ceratodontids to the late Santonian or possibly early Campanian (Eaton et al., Reference Eaton, Gardner, Kirkland, Brinkman, Nydam, MacLean, Biek and Huntoon2014). Lungfish fossils in eastern North America were unknown until the discovery of multiple specimens from the Albian-Aptian Trinity Group, which were later described by Parris et al. (Reference Parris, Grandstaff and Banks2014), and Cenomanian Woodbine Formation of northeastern Texas (Kirkland, Reference Kirkland1987; Main, Reference Main2013; Main et al., Reference Main, Parris, Grandstaff and Carter2014). Parris et al. (Reference Parris, Grandstaff and Gallagher2004) reported the youngest occurrence of fossil lungfish in North America from the late Campanian Mount Laurel Formation of New Jersey. An additional early to mid-Cretaceous occurrence of lungfish from eastern North America was reported from the Arundel Clay Facies of the Potomac Formation in Maryland (Frederickson et al., Reference Frederickson, Lipka and Cifelli2016).

As the New Jersey lungfish specimen (NJSM 18774) reported by Parris et al. (Reference Parris, Grandstaff and Gallagher2004) is late Campanian in age, ALMNH 8723 and MMNS VP-3440 from the late Santonian therefore represent the second-youngest lungfish specimens reported from North America. A possible exception to this assertion is a badly damaged lungfish tooth plate from the Santonian Iron Springs Formation of Utah; however, the age of the Iron Springs Formation is poorly constrained (Eaton et al., Reference Eaton, Gardner, Kirkland, Brinkman, Nydam, MacLean, Biek and Huntoon2014). Other studies have proposed that the Santonian–Campanian boundary near AGr-43 is positioned within the shark tooth lag deposit at the base of the Tombigbee Sand because of the co-occurrence of Santonian ammonites and Campanian chondrichthyans (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Slattery and Chamberlain1998). However, the biostratigraphic ranges of the Campanian fauna used in the Becker study have more recently been shown to extend into the Santonian (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Landman and Cobban2001; Shimada and Cicimurri, Reference Shimada and Cicimurri2005; Bourdon et al., Reference Bourdon, Wright, Lucas, Spielmann and Pence2011), supporting a latest Santonian age for the Tombigbee Sand in Greene County, Alabama. Geographically, ALMNH 8723 and MMNS VP-3440 represent the first Cretaceous lungfish fossils reported from the southeastern United States.

The Alabama and Mississippi lungfish specimens were collected from geologic units that were deposited in marginal marine environments. As other middle to Late Cretaceous lungfish specimens have been recovered from a range of marine or near-marine environments (Schultze, Reference Schultze1981; Parris et al., Reference Parris, Grandstaff and Gallagher2004; Frederickson et al., Reference Frederickson, Lipka and Cifelli2016), some authors have proposed that Late Cretaceous lungfish from North America may have developed a degree of salt tolerance (Frederickson and Cifelli, Reference Frederickson and Cifelli2017). Although the salt tolerance hypothesis is plausible, the present authors consider it more likely that these rare specimens represent material that was delivered to the marine setting by river discharge. For comparison, individuals of the modern Australian lungfish Neoceratodus forsteri are occasionally washed into estuarine environments by river floods. However, the species is unable to survive in brackish water, and these individuals will die soon if they are unable to return to fresh water (Kemp, Reference Kemp1993). Fossil material of several freshwater organisms has been recovered at sites AGr-43 and MS.44.001 (see Geologic setting). While the living relatives of these specific fossil organisms are also known from brackish water environments, the quantity of their fossil specimens at AGr-43 and MS.44.001 far outnumber the unique specimens of lungfish collected to date from each site. In fact, at MS.44.001, more dinosaur fossils (which are presumed to have been fully terrestrial organisms) have been recovered than fossil lungfish. If these Late Cretaceous lungfish were adapted to brackish or marginal marine environments, probability would suggest that the occurrence of lungfish fossils would be proportionally similar in frequency to that of other brackish water organisms from these sites.

It is interesting to note from the findings of this study that there appear to have been two species of lungfish living virtually simultaneously in the southern portion of the Appalachian subcontinent of North America during the Late Cretaceous. It is possible that these two species avoided direct competition with each other by ecological niche separation: C. frazieri may have preyed on thin-shelled mollusks and arthropods, processing the armor with its crushing-type dentition, whereas C. carteri may have used its sectorial dentition to consume soft-bodied invertebrates or small vertebrates (Kirkland, Reference Kirkland1987). Alternatively, these species may have utilized habitat segregation in which they preferred different zones within the water column (demersal vs. pelagic), different river drainage basins, or perhaps different regions of the river basins (upper vs. lower). Unfortunately, there currently is no direct fossil evidence to support any of these hypotheses. In present-day Africa, the four extant species of the lungfish genus Protopterus Owen, Reference Owen1839 exhibit habitat segregation by living in different river drainage basins or in different areas of the same basin, although there is some overlap in a few of the biogeographic ranges (Otero, Reference Otero2011). This lends some indirect support for possible habitat segregation of different contemporaneous lungfish species in the Late Cretaceous of southern Appalachia.

Conclusions

ALMNH 8723 is the first record of lungfish from the state of Alabama, and MMNS VP-3440 is the first record of lungfish from the state of Mississippi. These two specimens are the first records of lungfish from the Gulf Coastal Plain of the southeastern United States.

ALMNH 8723 is provisionally identified as a right prearticular tooth plate of Ceratodus frazieri on the basis of its broad and thin morphology, smooth occlusal surface, broadly rounded mesial-lingual margin, crests separated by shallow notches along the labial margin, and biometric similarity with referred specimens of C. frazieri. MMNS VP-3440 is tentatively referred to a right prearticular with tooth plate of Ceratodus carteri on the basis of its high, sharp cutting ridges, slightly obtuse inner angle, deep notches along the labial margin, and biometric similarity with the paratype and referred specimens of C. carteri.

ALMNH 8723 and MMNS VP-3440 are derived from the late Santonian Eutaw Formation in Alabama and Mississippi, respectively, and as such represent the second-youngest occurrence of fossil lungfish from eastern North America. This record partially bridges the geochronologic gap between the lungfish fossils from the Cenomanian of Texas and those of the Campanian of New Jersey.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their thanks to the Bryant family for their generosity in facilitating activities of ALMNH staff on their property in Alabama. G. Phillips of the MMNS is thanked for the loan of material under his care, for his information on the stratigraphy and geology of the Luxapallila site, and for his review of an earlier version of the manuscript. We are also indebted to the donor of the Mississippi tooth plate, E. Loftis of Columbus (MS), who first recognized the specimen as a lungfish and brought it to the attention of paleontologists. J. Fredrickson and R. Cifelli at the Sam Noble Museum at the University of Oklahoma provided the authors with casts of lungfish tooth plates in their collection. A. Nicosia and J. Spry provided assistance in the scanning electron microscopy of the Alabama specimen, which was performed at the Central Analytical Facility at the University of Alabama. J. Parham, then of the ALMNH, aided in the field research. R. Pellegrini at the NJSM is thanked for the loan of material under his care. D. Parris at the NJSM provided helpful comments on Ceratodus carteri. The original manuscript benefitted greatly from the critical reviews of A. Kemp, R. Cifelli, and several anonymous colleagues.