Introduction

In this work, we report the first occurrence of the ostracode Harpabollia harparum (Troedsson, Reference Troedsson1918), a key constituent of Hirnantian (uppermost Ordovician) assemblages and an index fossil for that stage (Meidla et al., Reference Meidla, Tinn, Salas, Williams, Siveter, Vandenbroucke, Sabbe, Harper and Servais2013), in a lithologic unit of Brazil—the Iapó Formation of the Rio Ivaí Group, Paraná basin. Paleozoogeographical and paleoecological implications of this new record are also briefly discussed herein. In addition, we report a new record of the ostracode Satiellina paranaensis Adôrno and Salas in Adôrno et al., Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016, which has implications for the stratigraphic framework of the Ordovician–Silurian transition in the Paraná basin.

Marine Ordovician fossil representatives of the Ostracoda Latreille, Reference Latreille1802 are present in the stratigraphic record of a wide range of latitudes (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Floyd, Salas, Siveter, Stone and Vannier2003; Mohibullah et al., Reference Mohibullah, Williams, Vandenbroucke, Sabbe and Zalasiewicz2012; Meidla et al., Reference Meidla, Tinn, Salas, Williams, Siveter, Vandenbroucke, Sabbe, Harper and Servais2013) and environments (Vannier et al., Reference Vannier, Siveter and Schallreuter1989; Williams and Siveter, Reference Williams and Siveter1996). Since the Early Ordovician (Salas et al., Reference Salas, Vannier and Williams2007, Reference Salas, Waisfeld and Muñoz2018; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Siveter, Salas, Vannier, Popov and Ghobadi Pour2008), ostracodes have presented a global geographical distribution, colonizing marine environments from shore faces to continental slopes (Braddy et al., Reference Braddy, Tollerton, Racheboeuf, Schallreuter, Webby, Paris, Droser and Percival2004). Although the record of Ordovician ostracodes is large, with hundreds of species described, it is very irregular among land masses and age intervals of that period. Whereas hundreds of species have been described from the paleocontinents of Baltica (Meidla, Reference Meidla1996; Tolmacheva et al., Reference Tolmacheva, Egerquist, Meidla and Holmer2001; Tinn et al., Reference Tinn, Meidla and Ainsaar2006), Laurentia (Williams and Siveter, Reference Williams and Siveter1996), Avalonia (Landing et al., Reference Landing, Mohibullah and Williams2013), Siberia (Melnikova, Reference Melnikova1986, Reference Melnikova2011), and Ibero-Armorica (Vannier, Reference Vannier1986; Vannier et al., Reference Vannier, Siveter and Schallreuter1989), the record is much more restricted in Gondwanan basins (Schallreuter, Reference Schallreuter1988; Hinz-Schallreuter and Schallreuter, Reference Hinz-Schallreuter and Schallreuter2007; Salas et al., Reference Salas, Vannier and Williams2007; Salas, Reference Salas2011; Salas and Vaccari, Reference Salas and Vaccari2012).

In the case of Hirnantian ostracode species, records are even fewer and restricted mainly to countries of the modern Baltica region (Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia) and Sweden (collectively known as Baltoscandia), with some isolated occurrences in Austria, Canada, Czech Republic, and Poland (Mohibullah et al., Reference Mohibullah, Williams, Vandenbroucke, Sabbe and Zalasiewicz2012; Meidla et al., Reference Meidla, Tinn, Salas, Williams, Siveter, Vandenbroucke, Sabbe, Harper and Servais2013; Truuver and Meidla, Reference Truuver and Meidla2015). During that age, prevailing latitude-related climatic gradients created a marked biogeographical segregation among low-, mid-, and high-latitude assemblages of brachiopod, graptolite, and chitinozoan faunas (Benedetto et al., Reference Benedetto, Halpern and Inchausti2013). However, only two distinct types of Hirnantian ostracode assemblages are observable worldwide: low-latitude warm-water assemblages, typified by Medianella aequa (Stumbur, Reference Stumbur1956), and mid- to high-latitude cool-water assemblages, characterized by Harpabollia harparum. One important exception to this scenario is the Baltic region, which was in a low- to mid-latitude upheaval zone during the Hirnantian. The consequent influence of the cold-water “Livonian tongue” in the region favored the establishment of a cold-water assemblage in latitudes lower than expected for such faunas (Meidla, Reference Meidla2007; Meidla et al., Reference Meidla, Tinn, Salas, Williams, Siveter, Vandenbroucke, Sabbe, Harper and Servais2013).

In South America, despite considerable investigation and sampling of Hirnantian successions, no ostracode faunas have been recorded so far, possibly because glacial events dominated the geological history of Gondwanan lithologies during that stage, as exemplified by records from the Andina Central and Precordillera basins in Argentina and the Maranhão and Paraná (i.e., the Iapó Formation) basins in Brazil (Alvarenga et al., Reference Alvarenga, Guimarães, Assine, Perinotto and Laranjeira1998; Benedetto et al., Reference Benedetto, Halpern, de la Puente and Monaldi2015). Occurrences of Satiellina paranensis and Conchoprimitia brasiliensis Adôrno and Salas in Adôrno et al., Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016 in shale levels at the base of the Vila Maria Formation, which overlies the Iapó, imply an Ordovician age for both the Iapó and lowermost Vila Maria formations because Satiellina Vannier, Reference Vannier1986 and Conchoprimitia Öpik, Reference Öpik1935 are restricted to the Ordovician Period. Coupled with the absence of an unconformity between the Iapó and Vila Maria formations, as well as the presence of glacial diamictite strata, this feature suggests a Hirnantian age for the interval (Adôrno et al., Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016). However, no index fossil typical of the Hirnantian has been observed in the Iapó–Vila Maria transition until now.

Geological setting

The Paraná is an intracratonic basin that encompasses territories of south-central Brazil, eastern Paraguay, northeastern Argentina, and central-west Uruguay. The Rio Ivaí Group is the lowermost Phanerozoic stratigraphic unit in the basin and Brazil, spanning from the Upper Ordovician to the Llandovery (Assine et al., Reference Assine, Soares and Milani1994; Milani et al., Reference Milani, Melo, Souza, Fernandes and França2007). The Rio Ivaí Group comprises, from bottom to top, the Alto Garças, Iapó, and Vila Maria formations and is exposed mainly at the northern border of the basin in Central-West Brazil (Alvarenga et al., Reference Alvarenga, Guimarães, Assine, Perinotto and Laranjeira1998).

The Iapó Formation is composed of diamictites and fine-grained facies with dropstones, deposited during a glacial advance/retreat cycle (Assine et al., Reference Assine, Soares and Milani1994, Reference Assine, Alvarenga and Perinotto1998; Alvarenga et al., Reference Alvarenga, Guimarães, Assine, Perinotto and Laranjeira1998). The Hirnantian age of the formation (Assine et al., Reference Assine, Soares and Milani1994, Reference Assine, Alvarenga and Perinotto1998) is based, among other features, on stratigraphic correlation with other glacial diamictite-bearing units, such as the Nhamundá and Ipú formations in Brazil (Caputo, Reference Caputo, Landing and Johnson1998; Vaz et al., Reference Vaz, Rezende, Wanderley Filho and Travassos2007), the Zapla in Argentina, the Cancañiri in Bolivia, and the Eusebio Ayala in Paraguay (Benedetto et al., Reference Benedetto, Halpern and Inchausti2013, Reference Benedetto and Muñoz2015; Cishowolski et al., Reference Cishowolski, Rustán and Uriz2019). The fine-grained facies of the Iapó Formation have so far provided fossiliferous occurrences of archeogastropods and brachiopods such as Kosoidea australis Zabini et al., Reference Zabini, Furtado-Carvalho, Do Carmo and Assine2019, an inarticulate brachiopod species of the Hirnantian–Llandovery genus Kosoidea Havlíček and Mergl, Reference Havlíček and Mergl1988 (Zabini et al., Reference Zabini, Furtado-Carvalho, Do Carmo and Assine2019, Reference Zabini, Denezine, Rodrigues, Gonçalves, Adôrno, Do Carmo and Assine2021) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Chronolithostratigraphic chart of the Rio Ivaí Group, Paraná basin, Brazil, according to Assine et al. (Reference Assine, Alvarenga and Perinotto1998) and Adorno et al. (Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016).

Samples studied in the present work were recovered from the Três Barras Farm section of Adôrno et al. (Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016), one of the best-known outcrops of the Iapó Formation and the only one dated through radiometric analysis (Mizusaki et al., Reference Mizusaki, Melo, Vignol-Lelarge and Steemans2002). This section is approximately 14 m in stratigraphic thickness, the lower 9.5 m of which are sedimentary deposits of the Iapó Formation, represented by massive polymictic glacial diamictites and shale with dropstones in a greenish-colored shale–sandstone matrix (Fig. 2). Just above these lies a thin layer of sandstone. The sedimentary deposits of the Iapó Formation at Três Barras Farm unconformably overlie granitic rocks that form the basement of the Paraná basin; above them lie the black shale levels of the Vila Maria Formation in gradational contact.

Figure 2. Lithologic log of the Três Barras Farm section, Bom Jardim de Goiás, State of Goiás, Brazil. (1) Contact between the Iapó Formation and the basement. (2) Diamictite facies of Iapó Formation. (3) Shale facies of the Vila Maria Formation. Symbols used herein follow the Federal Geographic Data Committee (2006).

Materials and methods

Field campaigns for this work were conducted between 2016 and 2018, during which were performed the lithostratigraphic log (descriptive criteria follow Miall, Reference Miall1985) and systematic sampling of the Três Barras Farm section. The main sampling area was at a subsection of Três Barras along the Jacaré Creek, located ~20 km south of the Town of Bom Jardim de Goiás, State of Goiás, Central-West Brazil (16°26.615′S, 52°5.825′W) (Fig. 3). One sample yielding ostracodes was collected at 6.95 m in the section MP-3519, from a level composed of shale with dropstones and sandstones.

Figure 3. Geographical map showing the location of the Três Barras Farm section and Paleozoic surfaces around the Bom Jardim de Goiás Municipality, State of Goiás, Brazil. Other Paleozoic units in the area include the Furnas and Ponta Grossa (Devonian) and the Aquidauana formations (Carboniferous), while the Ordovician–Silurian is represented by the Vila Maria and Iapó formations (Alvarenga et al., Reference Alvarenga, Guimarães, Assine, Perinotto and Laranjeira1998). Symbolization standards follow the Federal Geographic Data Committee (2006).

The methodology for extraction of ostracodes from rock samples followed Adôrno et al. (Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016): First, they were separated from the main bulk of samples by hand cutting ~0.3 cm3 blocks containing specimens. After that, each specimen was excavated from its blocks and cleaned with 1 mm syringe needles under a Leica ES4 stereoscopic microscope. Selected specimens were coated with gold on a Leica EM SCD500 high vacuum film deposition system and photographed and analyzed using a JEOL NeoScope JCM-5000 scanning electron microscope at the Micropaleontology Lab (LabMicro) of the University of Brasília (UnB), Brazil.

Images of specimens were measured, whenever possible, by using CorelDRAW X6 and the Windows 7 Calculator software. Due to a preservation artifact that led to dislocation between valves and abrasion, both the length and height of CP-852 and CP-902 were approximated up to points respectively assumed as the hypothetical posterior end and ventral margins of the right valve.

Repository and institutional abbreviation

All illustrated specimens are housed at LabMicro at the Research Collection of the Museum of Geosciences (MGeo), under the codification “CP” (from the Portuguese Coleção de Pesquisa) and numbers 851; 852; 853; 902; 903; 904; 905.

Systematic paleontology

The taxonomy of Harpabollia harparum (Troedsson, Reference Troedsson1918) and Satiellina paranaensis Adôrno and Salas in Adôrno et al., Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016 as well as their stratigraphic and paleozoogeographical distribution are presented here. Supraordinal and ordinal taxonomies follow Liebau (Reference Liebau2005) while the subordinal taxonomy is based on Mohibullah et al. (Reference Mohibullah, Williams and Zalasiewicz2013). The terminology for morphological features of ostracode carapaces and valves is from Scott (Reference Scott, Moore and Pitrat1961) and Vannier et al. (Reference Vannier, Siveter and Schallreuter1989).

Subclass Ostracoda Latreille, Reference Latreille1802

Superorder Podocopomorpha Kozur, Reference Kozur1972

Order Palaeocopida Henningsmoen, Reference Henningsmoen1953

Suborder Binodicopina Schallreuter, Reference Schallreuter1972

Superfamily Drepanelloidea Ulrich and Bassler, Reference Ulrich, Bassler, Swartz, Prouty, Ulrich and Bassler1923

Family Bolliidae Bouček, Reference Bouček1936

Genus Harpabollia Schallreuter, Reference Schallreuter1990

Type species

Bollia harparum Troedsson, Reference Troedsson1918 (Schallreuter, Reference Schallreuter1990), by original designation.

Diagnosis (emended)

Genus of Bolliidae characterized by the following features: elongate, L2 and L3 connected ventrally by a prominent U-shaped lobe; L1 and L4 as subvertical ridges, remarkably weaker than L2 and L3 and connected ventrally by a pseudovelum, forming a U-shaped groove parallel to the ventral margin; a wide, nonlobate area in the posterior region of the lateral valve surface.

Remarks

The generic diagnosis largely follows Schallreuter (Reference Schallreuter1990) but with modifications to avoid the original use of the morphological term “zygal crista.” Historically, names used for said structure have widely diverged (Kesling, Reference Kesling1951; Henningsmoen, Reference Henningsmoen1953, Reference Henningsmoen1965; Martinsson, Reference Martinsson1962; Weber and Becker, Reference Weber and Becker2006), even after Schallreuter (Reference Schallreuter1973) made a clear distinction between lobes and sulci (formed by folding of the valve and demonstrating the opposite structures on the internal surface) and ornamental features such as cristae (formed by thickening of the shell and not visible internally). In Harpabollia Schallreuter, Reference Schallreuter1990, the ventral connection of the two lobes demonstrates a clearly lobal character, being prominent also in internal molds (see Schallreuter Reference Schallreuter1990, fig. 2-2). This justifies the amendment of the generic diagnosis.

Melnikova (Reference Melnikova2010) suggested Harpabollia might be a junior synonym of Pseudozygobolbina Neckaja in Abushik et al. (Reference Abushik, Ivanova, Kochetkova, Martynova, Netskaya, Rozhdestvenskaya and Markovskiy1960). However, Harpabollia differs from Pseudozygobolbina by several features, including, in lateral view, greatest height of the carapace at a median (versus anterocentral) position, a less tumid (versus more tumid) L4 lobe that is positioned far (versus reaches closer) from the posterior end of the valves, L2 and L3 lobes not projecting (versus projecting) beyond the hinge line, and smooth (versus punctate) ornamentation around and over part of L2 and L3.

Harpabollia harparum (Troedsson, Reference Troedsson1918)

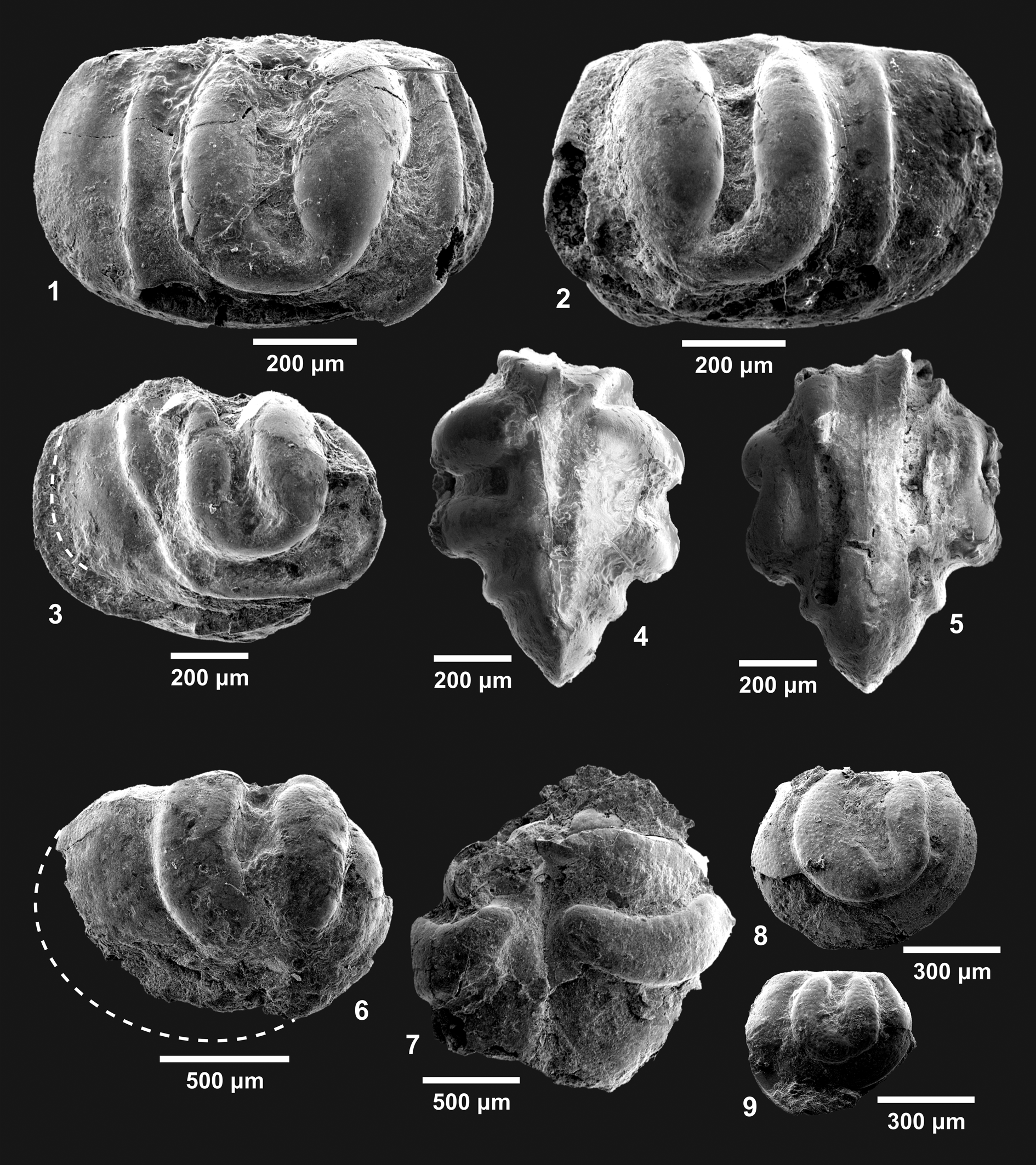

Figure 4.1–4.5

- Reference Troedsson1918

Bollia harparum Troedsson, p. 12, pl. 2, figs. 19, 20.

- ?Reference Bassler and Kellett1934

Bollia harparum; Bassler and Kellett, p. 72.

- Reference Havlíček and Vaněk1966

Bollia sp.; Havlíček and Vaněk, p. 61.

- ?Reference Gailite and Grigelis1968

Bollia mezvagarensis; Gailite, p. 132.

- ?Reference Gailite1970

Bollia mezvagarensis; Gailite, p. 23.

- ?Reference Nilsson1979

Bollia harparum; Nilsson, p. 11.

- ?Reference Ul'st, Gailite and Yakovleva1982

Bollia mezvagarensis; Ul'st et al., p. 121.

- Reference Sztejn1985

Bollia mezvagarensis; Sztejn: p. 72, pl. 4, fig. 8.

- ?Reference Schönlaub, Daurer and Schönlaub1985

Quadrijugator harparum; Schönlaub, p. 66.

- Reference Vannier1986

Quadrijugator? harparum; Vannier, p.107, figs. 30D, E, 31a, b.

- ?Reference Schönlaub, Cocks and Rickards1988

Quadrijugator harparum; Schönlaub, p. 109.

- Reference Schallreuter1988

Harpabollia harparum; Schallreuter and Krůta, p. 100.

- Reference Schallreuter1990

Harpabollia harparum; Schallreuter, p. 122, fig. 2:1–3.

- Reference Sidaravičiene1992

Bollia mezvagarensis; Sidaravičiene, p. 166, pl. 53, fig. 10.

- Reference Schallreuter1995

Harpabollia argentina; Schallreuter, p. 2, pl. 83, fig. 1.

- Reference Meidla1996

Harpabollia harparum; Meidla, p. 80, pl. 15, fig. 3.

- [non] Reference Gubanov and Bogolepova1999

Harpabollia harparum; Gubanov and Bogolepova, p. 419, fig. 2J.

- Reference Meidla2007

Harpabollia harparum; Meidla, p. 124, fig. 2a, b.

- Reference Truuver and Meidla2015

Harpabollia harparum; Truuver and Meidla, p. 739, figs. 5.25, 7M, N.

- Reference Zabini, Denezine, Rodrigues, Gonçalves, Adôrno, Do Carmo and Assine2021

Harpabollia harparum; Zabini et al., p. 9, fig. 8a.

Figure 4. Ostracode species found in the Iapó Formation, Rio Ivaí Group, Paraná basin, Brazil. (1–5) Harpabollia harparum (Troedsson, Reference Troedsson1918). (1, 2, 4, 5) Adult carapace (CP 851): (1) right lateral view; (2) left lateral view; (4) dorsal view; (5) ventral view. (3) Adult carapace (CP 852) displaying a preserved connection between L1 and L4 lobes (the dotted line marks the approximate posterior end of the right valve). (6–9) Satiellina paranaensis Adôrno and Salas in Adôrno et al., Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016: (6), adult carapace (CP-902), right lateral view (the dotted line marks the approximate posterior end and dorsal margins of the carapace); (7) (CP-903) dorsal view of disarticulated valves; (8) juvenile valve (CP 904), right lateral view; (9) juvenile valve (CP 905), right lateral view.

Lectotype

Mold of a left valve, no. LO 2904T, from Tommarp, Sweden, currently housed at the Department of Geology of Lund University, Lund, Sweden (Troedsson, Reference Troedsson1918).

Diagnosis (new)

Species of Harpabollia characterized by the following features: valves that are more convex anteriorly; L2 and L3 with elongated bulb-like dorsal swellings; L2 is more prominent than L3 and may reach slightly beyond the dorsal margin; L1 and L4 as subvertical ridges; L1 nearly parallel to the anterior margin.

Occurrence

Late Ordovician: Katian, Precordillera Argentina basin (Salas, Reference Salas2007), Rio Sassito Formation sensu Keller and Lehnert (Reference Keller and Lehnert1998), Argentina, San Juan Province, Sassito Creek (Schallreuter, Reference Schallreuter1995); Hirnantian: (1) Scandinavian basin sensu Harris et al. (Reference Harris, Sheehan, Ainsaar, Hints, Männik, Nõlvak and Rubel2004), Sweden: (1a) upper part of Lindegård mudstone (Calner et al., Reference Calner, Erlström, Eriksson, Ahlberg, Lehnert, Calner, Ahlberg, Lehnert and Erlström2013), Skåne County, Röstånga (“localities 5a and 3i”) and Tommarp (“locality 17”) (Troedsson, Reference Troedsson1918), and (1b) possibly Loka Formation, Östergötland County, Borenshult locality (Meidla, Reference Meidla2007), (2) Livonian basin sensu Harris et al. (Reference Harris, Sheehan, Ainsaar, Hints, Männik, Nõlvak and Rubel2004), Kuldiga Formation: (2a) Latvia, Ventspils Municipality, Mežvagari and Piltene, Kuldīga Municipality, Adze and Remte, Saldus Municipality, Blidene and Sturi, Engure Municipality, Dreimani (Gailite, Reference Gailite1970), Pavilosta Municipality, Riekstini (Brenchley et al., Reference Brenchley, Carden, Hints, Kaljo, Marshall, Martma, Meidla and Nõlvak2003), and Jūrmala Municipality, Jūrmala (Meidla et al., Reference Meidla, Ainsaar, Truuver, Gutiérrez-Marco, Rábano and García-Bellido2011), and (2b) Estonia, Valga County, Taagepera (Meidla, Reference Meidla1996), and Pärnu County, Ruhnu (Brenchley et al., Reference Brenchley, Carden, Hints, Kaljo, Marshall, Martma, Meidla and Nõlvak2003), (3) Prabuty Formation (Truuver and Meidla, Reference Truuver and Meidla2015), Poland, Warmińsko-Mazurskie Voivodeship, Dłużec Mały (Sztejn, Reference Sztejn1985; Podhalańska, Reference Podhalańska and Podhalańska2014), (4) Carnic basin, Plöcken Formation sensu Corradini et al. (Reference Corradini, Pondrelli, Suttner and Schönlaub2015), Austria, Carinthia State, “Cellon section” (Carnic Alps) (Schallreuter, Reference Schallreuter1990), and (5) Prague basin, Kosov Formation sensu Röhlich (Reference Röhlich2007), Czech Republic, Bohemia (Havlíček and Vaněk, Reference Havlíček and Vaněk1966; Schallreuter and Krůta, Reference Schallreuter and Krůta1988). The present work expands the lithostratigraphic and geographical distributions of the species to, respectively, the Iapó Formation, Rio Ivaí Group, Paraná basin, and the Três Barras Farm section, Bom Jardim de Goiás, State of Goiás, Brazil.

Materials

CP-851, adult carapace (length = 0.892 mm; height = 0.574 mm; width = 0.663 mm), CP-852, adult carapace (length ≈ 0.862 mm; height ≈ 0.542 mm; width nonmeasurable), and CP-853, adult disarticulated valves (nonmeasurable).

Remarks

The specific identification follows Troedsson (Reference Troedsson1918). In the present work, we include a specific diagnosis for Harpabollia harparum because it is absent from Schallreuter (Reference Schallreuter1990), who solely provided a diagnosis for the genus Harpabollia. Some individuals from Baltoscandian strata in Estonia (Meidla, Reference Meidla1996), Poland (Sztejn, Reference Sztejn1985; Truuver and Meidla, Reference Truuver and Meidla2015), and Sweden (Meidla, Reference Meidla2007) differ from the Brazilian ones by their narrower and less tumid L3 lobe, but the Brazilian morphotype is also present in the Baltoscandian area, as exemplified by other materials from Sweden (Troedsson, Reference Troedsson1918) and Austria (Schallreuter, Reference Schallreuter1990). In a similar way, the weak L4 lobe also varies rather widely within the pool of figured specimens. This might be due to different levels of preservation, as some of the materials are internal molds and not carapaces or valves. Bollia mezvagarensis Gailite, Reference Gailite1970 is strikingly similar to other species of Harpabollia, despite its type materials being much larger than Harpabollia harparum and Harpabollia argentina Schallreuter, Reference Schallreuter1995. Specimens of Bollia mezvagarensis in Sztejn (Reference Sztejn1985) are of the same size as the ones in Troedsson (Reference Troedsson1918) and, despite the poor positioning of specimens for illustration in the plates, clearly belong to Harpabollia harparum. Bollia mezvagarensis in Sidaravičiene (Reference Sidaravičiene1992) presents a higher length/height ratio than the Harpabollia harparum type specimen illustrations in Troedsson (Reference Troedsson1918) due to electronic deformation of illustrative SEM photographs; otherwise, they clearly belong to Harpabollia harparum. Despite being different in size and overall shape, Harpabollia argentina is strikingly similar in ornamentation to Harpabollia harparum; we consider it to be a juvenile instar form of the species as it is common among binodicopine ostracodes for the juveniles and adults of the same species to share common ornamentation features. Several doubtful attributions in the synonymic list of Harpabollia harparum (Bassler and Kellett, Reference Bassler and Kellett1934; Gailite, Reference Gailite and Grigelis1968; Nilsson, Reference Nilsson1979; Ul'st et al., Reference Ul'st, Gailite and Yakovleva1982; Schönlaub, Reference Schönlaub, Daurer and Schönlaub1985, Reference Schönlaub, Cocks and Rickards1988) are due to such publications not presenting images of specimens evaluated. The only exceptions to this list are Havlíček and Vaněk (Reference Havlíček and Vaněk1966) and Schallreuter and Krůta (Reference Schallreuter and Krůta1988), since both materials were evaluated by the author who proposed both the genus Harpabollia and the inclusion of Harpabollia harparum as its type species (Schallreuter, Reference Schallreuter1990). The specimen figured in Gubanov and Bogolepova (Reference Gubanov and Bogolepova1999) clearly does not present the lobe pattern of the genus Harpabollia and therefore is not synonymous with Harpabollia harparum.

Family incertae sedis

Genus Satiellina Vannier, Reference Vannier1986

Type species

Bollia delgadoi Vannier, Reference Vannier1983 (Vannier, Reference Vannier1986), by original designation.

Satiellina paranaensis Adôrno and Salas in Adôrno et al., Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016

Figure 4.6–4.9

- Reference Adôrno2014

Satiellina jamariensis; Adôrno, p. 28, figs. 4.13.1–17.

- Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016

Satiellina paranaensis Adôrno and Salas in Adôrno et al., p. 383, figs. 4A–F.

Holotype

Mold of a left valve, CP-634, from Bom Jardim de Goiás Municipality, Brazil, housed in the scientific collections of the Museum of Geosciences at LabMicro, University of Brasilia, Brazil (Adôrno et al., Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016).

Occurrence

Uppermost Ordovician of the Paraná basin, Rio Ivaí Group, Vila Maria Formation, Aldeia Creek section, Bom Jardim de Goiás, State of Goiás, Brazil (Adôrno et al., Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016). The present work expands the lithostratigraphic and geographical distributions of the species to, respectively, the Iapó Formation, Rio Ivaí Group, and the Três Barras Farm section.

Materials

CP-902, adult carapace (length ≈ 1.383 mm; height ≈ 1.047 mm; width = 0.603 mm), CP-903, adult disarticulated valves (nonmeasurable), CP-904, juvenile valve (length = 0.704 mm; height = 0.502 mm), and CP-905, juvenile valve (length = 0.532 mm; height = 0.452 mm).

Remarks

The diagnosis follows Adôrno et al. (Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016). In addition, due to the recovery of better-preserved molds that could eventually be separated from the rock matrix, the present work adds imaging of Satiellina paranaensis in dorsal view, as well as from juvenile instars of the species. However, new materials display differences from type specimens in Adôrno et al. (Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016), namely, a slight furrow in the dorsal half of the L2 lobe and punctate ornamentation over the lobes; these variations are probably also due to better preservation of the present specimens compared with the type material of Satiellina paranaensis.

Discussion

Ostracode assemblages and the age of the Iapó Formation

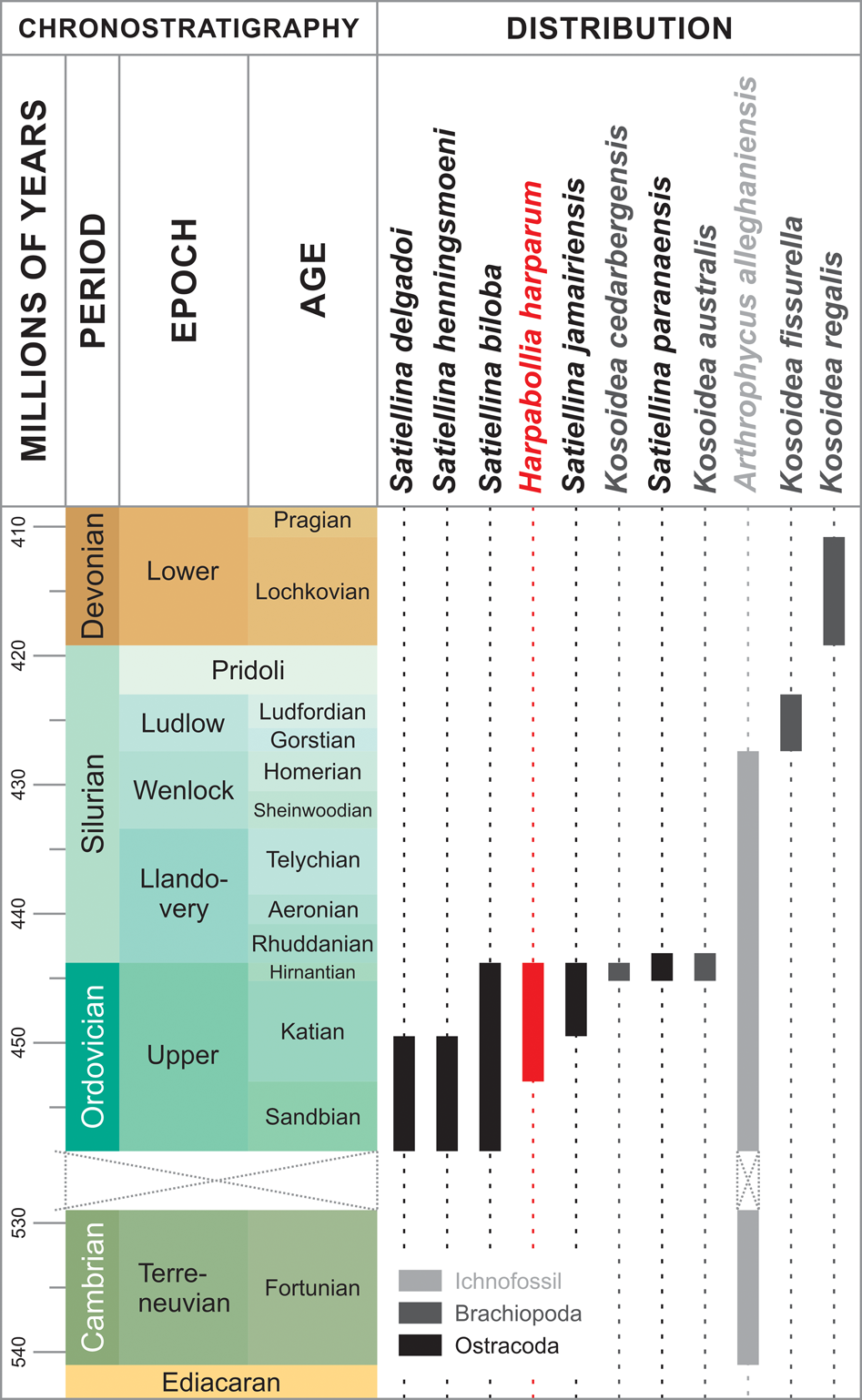

The faunas of the Ordovician–Silurian sedimentary deposits of the Paraná basin were known from very isolated and poorly studied occurrences (Popp et al., Reference Popp, Burjack and Esteves1981) until Conchoprimitia brasiliensis and Satiellina paranaensis were described by Adôrno et al. (Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016) from the Vila Maria Formation. Other than Satiellina paranaensis, the genus Satiellina comprises four species of Middle–Upper Ordovician distribution throughout Ibero-Armorica, Gondwana, and Baltica: Satiellina biloba (Troedsson, Reference Troedsson1918), Satiellina delgadoi (Vannier, Reference Vannier1983), Satiellina henningsmoeni Nion in Robardet et al., Reference Robardet, Henry, Nion, Paris and Pillet1972, and Satiellina jamairiensis Vannier, Reference Vannier1986. Due to its wide geographical distribution and the restricted overall biostratigraphic range of its species, the genus is important for intrabasinal strata correlation (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Species diversity and stratigraphic distribution of the ostracod genera Satiellina Vannier, Reference Vannier1986 and Harpabollia Schallreuter, Reference Schallreuter1990, the brachiopod genus Kosoidea Havlíček and Mergl, Reference Havlíček and Mergl1988, and the ichnospecies Arthrophycus alleghaniensis (Harlan, Reference Harlan1831).

The present record of the monospecific genus Harpabollia and its widespread species, Harpabollia harparum, is the first of a taxon whose known distribution is restricted to the Hirnantian (Truuver and Meidla, Reference Truuver and Meidla2015) in the Rio Ivaí Group of the Paraná basin. Harpabollia harparum is the dominant component of the “Harpabollia harparum assemblage,” an important and well-known faunal association related to Upper Ordovician cold-water seas around Baltica and the Argentinean region of Gondwana. It is regarded as diagnostic of the Hirnantian by its co-occurrence with typical members of the Hirnantia–Dalmanitina fauna of invertebrates (Meidla, Reference Meidla2007; Truuver and Meidla, Reference Truuver and Meidla2015). Therefore, this taxon is a powerful tool to constrain the age both of the Iapó Formation and of species associated with it in these deposits, such as Satiellina paranaensis. The ostracode fauna herein identified, constituted by Harpabollia harparum and Satiellina paranaensis, is also the oldest recorded in deposits from Brazil so far and the first of Hirnantian age in South America.

A Hirnantian age for the Iapó Formation can also be inferred by the occurrence (Zabini et al., Reference Zabini, Furtado-Carvalho, Do Carmo and Assine2019) of the Hirnantian–Lower Devonian brachiopod genus Kosoidea, which comprises the following species: Kosoidea australis Zabini et al., Reference Zabini, Furtado-Carvalho, Do Carmo and Assine2019, Kosoidea cedarbergensis Basset et al., Reference Basset, Popov, Aldridge, Gabbott and Theron2009, Kosoidea fissurella Havlíček and Mergl, Reference Havlíček and Mergl1988, and Kosoidea regalis Havlíček, Reference Havlíček1999. In the Três Barras Farm section, Kosoidea australis occurs together with Satiellina paranaensis and Harpabollia harparum in sample MP-3519 of the Iapó Formation. Another important aspect of Kosoidea australis is that the species can be found in the Upper Iapó and lower part of the Vila Maria formations (Ordovician) in the Aldeia Creek section of Adôrno et al. (Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016) and the COHAB section of Zabini et al. (Reference Zabini, Furtado-Carvalho, Do Carmo and Assine2019; Reference Zabini, Denezine, Rodrigues, Gonçalves, Adôrno, Do Carmo and Assine2021) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Composite section of the Iapó–Vila Maria interval around the Bom Jardim de Goiás Municipality, State of Goiás, Brazil: (1) Aldeia Creek outcrop; (2) Três Barras Farm outcrop; (3) COHAB outcrop. Co-occurrences of Harpabollia harparum (Troedsson, Reference Troedsson1918), Satiellina paranaensis Adôrno and Salas in Adôrno et al., Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016, and Kosoidea australis Zabini et al., Reference Zabini, Furtado-Carvalho, Do Carmo and Assine2019 are exclusive of shale with dropstone levels of the Hirnantian Iapó Formation; the latter two also co-occur at the shale levels of the Hirnantian–Ruddanian basal Vila Maria (Adôrno et al., Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016; Zabini et al., Reference Zabini, Furtado-Carvalho, Do Carmo and Assine2019), which is also constrained by Rb/Sr dating (Mizusaki et al., Reference Mizusaki, Melo, Vignol-Lelarge and Steemans2002). Arthrophycus alleghaniensis (Harlan, Reference Harlan1831) is found in sandstone/siltstone levels typical of the upper Llandovery (Silurian) Vila Maria (Burjack and Popp, Reference Burjack and Popp1981).

Upper portions of the Vila Maria Formation are currently dated as Llandovery, initially on the basis of the presence (Burjack and Popp, Reference Burjack and Popp1981) of the Cambrian–early Silurian (Neto de Carvalho et al., Reference Neto de Carvalho, Fernandes and Borghi2003) ichnospecies Arthrophycus alleghaniensis (Harlan, Reference Harlan1831) (also found in the upper part of the Aldeia Creek section [Adôrno et al., Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016]) and later confirmed by palynomorph assemblages (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Colbath, Faria, Boucot and Rohr1985). Additional radiometric Rb–Sr data from the Três Barras Farm section (Mizusaki et al., Reference Mizusaki, Melo, Vignol-Lelarge and Steemans2002) indicate an absolute dating of 435.9 ± 7.8 Ma for the shale levels from the Vila Maria Formation, which places it slightly over, but still into the chronologic range of, the late Hirnantian (443.8 ±1.5 Ma). Therefore, it also agrees (at least partially) with the present brachiopod- and ostracode-based dating for the Iapó and basal Vila Maria formations as Hirnantian.

Paleobiogeography and paleoenvironment analysis

Paleobiogeographical relationships between Ordovician faunas of the Paraná basin and those from Gondwanan and peri-Gondwanan regions have been previously addressed by Adôrno et al. (Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016), who hypothesized the presence of Satiellina paranaensis was an indication of the affinities between strata of the Paraná basin and those in northern Africa and Ibero-Armorica. Zabini et al. (Reference Zabini, Furtado-Carvalho, Do Carmo and Assine2019, Reference Zabini, Denezine, Rodrigues, Gonçalves, Adôrno, Do Carmo and Assine2021) suggested the presence of Kosoidea reveals similarities between the Paraná basin and the South African Soom Formation of the Karoo basin (Basset et al., Reference Basset, Popov, Aldridge, Gabbott and Theron2009). The occurrence of Harpabollia harparum expands the correlation to Baltica, where most of the records of the species are observed (Truuver and Meidla, Reference Truuver and Meidla2015).

Harpabollia and Satiellina were genera typically found in seas that were strongly influenced by nearby ice sheets (although their distribution was not confined to such paleoenvironments [Meidla et al., Reference Meidla, Tinn, Salas, Williams, Siveter, Vandenbroucke, Sabbe, Harper and Servais2013]); such were the environments found along the continental glacial deposits of the Iapó Formation, as well as in several localities in Gondwana and nearby continents (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chatterton and Wang1997; Le Heron and Howard, Reference Le Heron and Howard2010; Vidal et al., Reference Vidal, Dabard, Gourvennec, Le Hérissé, Loi, Paris, Plusquellec and Racheboeuf2011; Benedetto et al., Reference Benedetto, Halpern and Inchausti2013). Deposits of the Iapó are typical of middle- to outer-ramp marine environments (Assine et al., Reference Assine, Alvarenga and Perinotto1998; Benedetto and Muñoz, Reference Benedetto and Muñoz2015) and correlate well with glaciogenic deposits in Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, Peru, and South Africa.

The faunal affinities between these regions suggest a rapid immigration event for the cold-water species of Harpabollia and Satiellina along lower- and higher-latitude areas (Vannier, Reference Vannier1986; Meidla, Reference Meidla2007; Scotese, Reference Scotese2014) (Fig. 7). Binodicopine ostracodes such as Harpabollia and Satiellina rapidly migrated during the Late Ordovician from peri-Gondwana to Avalonia and Baltica propelled by cold-water currents, reaching mostly the deep-shelf (and even shallow-platform) paleoenvironments of these areas. Three possible mechanisms are suggested to explain the migration: (1) active island hopping through Avalonia (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Floyd, Salas, Siveter, Stone and Vannier2003) until Baltica, following the pathway opened by the resurgence of the “Livonian tongue” (Meidla et al., Reference Meidla, Tinn, Salas, Williams, Siveter, Vandenbroucke, Sabbe, Harper and Servais2013); (2) passive long-distance migration through currents (Titterton and Whatley, Reference Titterton, Whatley, Hanai, Ikeya and Ishizaki1998) along the northernmost Rheic Ocean up to Ibero-Armorica; (3) passive transport on host animals (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Floyd, Salas, Siveter, Stone and Vannier2003) such as cephalopods (very common during the Ordovician) or possibly sharks.

Figure 7. Late Ordovician (Katian–Hirnantian) paleogeographic map (modified from Scotese, Reference Scotese2014 according to Cocks and Torsvik, Reference Cocks and Torsvik2020) showing the latest Ordovician paleozoogeographic distribution of the ostracode genera Harpabollia Schallreuter, Reference Schallreuter1990 and Satiellina Vannier, Reference Vannier1986. Notice that species of both genera are confined to regions dominated by cold-water marine currents (Scotese, Reference Scotese2000).

The widespread distribution of Harpabollia harparum in the Hirnantian can be traced back to the Katian, when the species was found throughout the Argentinean Precordillera. From there, it seems to have migrated to North and peri-Gondwanan areas during the latest Ordovician. This migration would continue toward the Baltica regions, where Meidla (Reference Meidla2007) first described the Harpabollia harparum assemblage, typical of Hirnantian cold-water paleoenvironments. Therefore, the occurrence of Harpabollia harparum in the Paraná basin represents another step in the pathway proposed for the distribution of the species through Late Ordovician cold-water sea regions. Additional occurrences of Satiellina paranaensis and Kosoidea australis, associated with Harpabollia harparum in the Iapó Formation and in the lower portion of Vila Maria Formation (Adôrno et al., Reference Adôrno, Do Carmo, Salas, Zabini and Assine2016; Zabini et al., Reference Zabini, Furtado-Carvalho, Do Carmo and Assine2019), indicate a continuous deposition between the Hirnantian–Llandovery intervals or positioned in the lower levels of black shale from Vila Maria Formation.

Conclusions

The first occurrence of ostracodes described in the Iapó Formation comprises faunas that were recovered from strata at Goiás State, Brazil. Two species were identified in the present samples: Satiellina paranaensis, known from the Vila Maria Formation in the Ordovician–Silurian of the Paraná basin, and, more diagnostic to Hirnantian, Harpabollia harparum. The occurrence of this species is a powerful tool to date the Iapó Formation as Hirnantian and to attribute the associated occurrences of Satiellina paranaensis to the same chronostratigraphic interval. So far, this is also the oldest ostracode fauna recorded in sedimentary deposits from Brazil and the first Hirnantian ostracod species in South America.

Species of Harpabollia and Satiellina ostracod genera were cold-water taxa found in marine paleoenvironments strongly influenced by nearby glaciation, such as those along the continental glacial deposits of the Iapó Formation and other parts of Gondwana and Baltica. The faunal affinity between these regions suggests a rapid migration event for both Harpabollia and Satiellina species, starting from the Argentinean Precordillera during the Katian and reaching other higher-latitude areas (Gondwana), as well as lower-latitude ones (Ibero-Armorica and Baltica, where the Harpabollia harparum assemblage was first identified) during the Hirnantian.

Considering occurrence of Kosoidea australis in the post-Hirnantian interval in the Vila Maria Formation, it seems that paleoenvironmental changes associated with warming sea temperatures during the Ordovician–Silurian transition have not extensively affected such faunal distributions in the Rhuddanian interval of Vila Maria Formation.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the Brazilian Fundação de Apoio à Pesquisa do Distrito Federal (process no. 00193.00002054/2018-91) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) (process no. 459776/2014-2) for financial support for the present work, granted between 2018 and 2020. Additional thanks go to the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior for providing vital access to a vast library of scientific works through its Portal de Periódicos database. We also thank the Center for Research in Earth Sciences, National Scientific and Technical Research Council of the National University of Córdoba, Argentina, for providing laboratory assistance for the study of fossil materials during technical visit by L.R.O. Gonçalves. Finally, we are grateful to the researchers A.M. Leite, A.S. Reis, C. Zabini, and E. Vaccari for the very deep and insightful scientific dialogs that helped enhance this manuscript as well as to the reviewers and the associated editor of the Journal of Paleontology for their detailed revision.