Introduction

Macroscopic algae have been reported in the Paleoproterozoic (e.g., Hofmann and Chen, Reference Hofmann and Chen1981; Han and Runnegar, Reference Han and Runnegar1992; Yan, Reference Yan1995; Zhu and Chen, Reference Zhu and Chen1995; Yan and Liu, Reference Yan and Liu1997; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Sun, Huang, He, Zhu, Sun and Zhang2000; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Zhu, Huang, Cao and Xin2004), Mesoproterozoic (e.g., Walter et al., Reference Walter, Oehler and Oehler1976; Du et al., Reference Du, Tian and Li1986; Kumar, Reference Kumar1995, Reference Kumar2001; Dutta et al., Reference Dutta, Steiner, Banerjee, Erdtmann, Jeevankumar and Mann2006; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Zhu and Huang2006; Sharma and Shukla, Reference Sharma and Shukla2009a, Reference Sharma and Shuklab; Babu and Singh, Reference Babu and Singh2011; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Zhu, Knoll, Yin, Zhao, Sun, Qu, Shi and Liu2016), and early–middle Neoproterozoic (e.g., Hofmann and Aitken, Reference Hofmann and Aitken1979; Du, Reference Du1982; Du and Tian, Reference Du and Tian1982, Reference Du and Tian1985a, Reference Du and Tianb; Duan, Reference Duan1982; Duan et al., Reference Duan, Xing, Du, Yin, Liu, Xing, Duan, Liang and Cao1985; Hofmann, Reference Hofmann1985, Reference Hofmann, Schope and Klein1992; Walter et al., Reference Walter, Du and Horodyski1990; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Tong, Xiao, Zhu, An, Tian and Hu2015). However, abundant and diverse macroalgae are found from the late Neoproterozoic Ediacaran strata (e.g., Gnilovskaya, Reference Gnilovskaya1971, Reference Gnilovskaya, Sokolov and Iwanowski1990; Zhu and Chen, Reference Zhu and Chen1984; Chen and Xiao, Reference Chen and Xiao1991, Reference Chen and Xiao1992; Ding et al., Reference Ding, Zhang, Li and Dong1992, Reference Ding, Li, Hu, Xiao, Su and Huang1996; Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Erdtmann and Chen1992; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiao and Yuan1994; Steiner, Reference Steiner1994; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Li and Chen1995, Reference Yuan, Li and Cao1999, Reference Yuan, Chen, Xiao, Zhou and Hua2011, Reference Yuan, Wan, Guan, Chen, Zhou, Xiao, Wang, Pang, Tang and Huan2016; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002, Reference Xiao, Droser, Gehling, Hughes, Wan, Chen and Yuan2013; Grazhdankin et al., Reference Grazhdankin, Nagovitsin and Maslov2007; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Huang2007, Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2014, Reference Wang, Du, Komiya, Wang and Wang2015a, Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2016a, Reference Wang, Wang and Dub, Reference Wang, Wang and Du2017; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yin, Liu, Duan and Gao2008a, Reference Tang, Yin, Liu, Gao and Wang2009; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Babu and Shukla2009; Marusin et al., Reference Marusin, Grazhdankina and Maslov2011; Pandey and Sharma, Reference Pandey and Sharma2017; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Tong, An, Hu, Tian, Guan and Xiao2019). Macroalgae emerged in the Paleoproterozoic and prosperously developed in the Ediacaran, which is important for understanding the biotic and environmental evolution at the dawn of animal life. Metaphytes and eukaryotic algae were considered to have tissue and/or organ differentiation, among which the macroalgal holdfast generally was used in previous publications as one of the distinguishing features of organ differentiation (e.g., Du and Tian, Reference Du and Tian1985a, Reference Du and Tianb; Liu and Du, Reference Liu and Du1991; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Li and Chen1995, Reference Yuan, Chen, Xiao, Zhou and Hua2011; Zhu and Chen, Reference Zhu and Chen1995; Ding et al., Reference Ding, Li, Hu, Xiao, Su and Huang1996; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chen and Xiao2000; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002, Reference Xiao, Droser, Gehling, Hughes, Wan, Chen and Yuan2013; Wang and Wang, Reference Wang and Wang2006; Xiao, Reference Xiao, Trueba and Montufar2013; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2015b, Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2016a, Reference Wang, Wang and Du2017, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a). The Precambrian macroalgal holdfast commonly consists of a rhizome that developed from the base of the thallus or stipe and a rhizoid growing on the rhizome (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Du, Komiya, Wang and Wang2015a, Reference Wang, Wang and Du2017, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a). With a holdfast (a simple rhizome without a rhizoid) extended by its thallus (Walter et al., Reference Walter, Du and Horodyski1990; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Du2016b, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a), the eukaryotic macroalga Grypanis spiralis (Walcott, Reference Walcott1899) Walter et al., Reference Walter, Oehler and Oehler1976 (e.g., Walter et al., Reference Walter, Oehler and Oehler1976, Reference Walter, Du and Horodyski1990; Runnegar, Reference Runnegar1991; Han and Runnegar, Reference Han and Runnegar1992; Hofmann, Reference Hofmann, Schope and Klein1992; Sharma and Shukla, Reference Sharma and Shukla2009a; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2016a, Reference Wang, Wang and Dub, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a), which has been reported from the Paleoproterozoic Negaunee Iron Formation (dated to ca. 1870 Ma by Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Bickford, Cannon, Schulz and Hamilton2002) in the USA (Han and Runnegar, Reference Han and Runnegar1992), was regarded as the earliest fossil record of eukaryotic algae (Runnegar, Reference Runnegar1991; Han and Runnegar, Reference Han and Runnegar1992; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Du2016b, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a). Macroalgae with a taping or globular rhizome without a rhizoid were recorded in the late Paleoproterozoic Tuanshanzi Formation (ca. 1700 Ma) in North China (see Hofmann and Chen, Reference Hofmann and Chen1981; Yan, Reference Yan1995; Zhu and Chen, Reference Zhu and Chen1995; Yan and Liu, Reference Yan and Liu1997; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a). With a holdfast composed of a tapering or globular rhizome and filamentous or disk-like rhizoid, abundant and diverse eukaryotic macroalgae were found in the Ediacaran from Australia (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Droser, Gehling, Hughes, Wan, Chen and Yuan2013), India (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Babu and Shukla2009; Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Tiwari, Ahmad, Shukla, Shukla, Singh, Pandey, Ansari, Shukla and Sumar2016; Pandey and Sharma, Reference Pandey and Sharma2017), Namibia (Leonov et al., Reference Leonov, Fedonkin, Vichers-Rich, Ivantsov and Trusler2009), Russia (Gnilovshaya, Reference Gnilovskaya1971, Reference Gnilovskaya, Sokolov and Iwanowski1990; Gnilovshaya et al., Reference Gnilovskaya, Istchenko, Kolesnikov, Korenchuk and Udaltsov1988; Grazhdankin et al., Reference Grazhdankin, Nagovitsin and Maslov2007; Marusin et al., Reference Marusin, Grazhdankina and Maslov2011), and South China (Zhu and Chen, Reference Zhu and Chen1984; Chen and Xiao, Reference Chen and Xiao1991, Reference Chen and Xiao1992; Ding et al., Reference Ding, Zhang, Li and Dong1992, Reference Ding, Li, Hu, Xiao, Su and Huang1996; Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Erdtmann and Chen1992; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiao and Yuan1994, Reference Chen, Chen and Xiao2000; Steiner, Reference Steiner1994; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Li and Chen1995, Reference Yuan, Li and Cao1999, Reference Yuan, Chen, Xiao, Zhou and Hua2011, Reference Yuan, Wan, Guan, Chen, Zhou, Xiao, Wang, Pang, Tang and Huan2016; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Knoll and Yuan1998, Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Huang2007, Reference Wang, Chen, Wang and Huang2011, Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2014, Reference Wang, Du, Komiya, Wang and Wang2015a, Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2016a, Reference Wang, Wang and Du2017; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yin, Liu, Duan and Gao2008a, Reference Tang, Yin, Liu, Gao and Wang2009; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Tong, An, Hu, Tian, Guan and Xiao2019). However, the emergence of pithy macroalgae has been debated over whether a tubular or cylindrical structure within macroalgal stipes in the middle–late Ediacaran are natural biotic structures or diagenetic abiotic structures (e.g., Ding et al., Reference Ding, Li, Hu, Xiao, Su and Huang1996; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Huang2007, Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2015b, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Tong, An, Hu, Tian, Guan and Xiao2019).

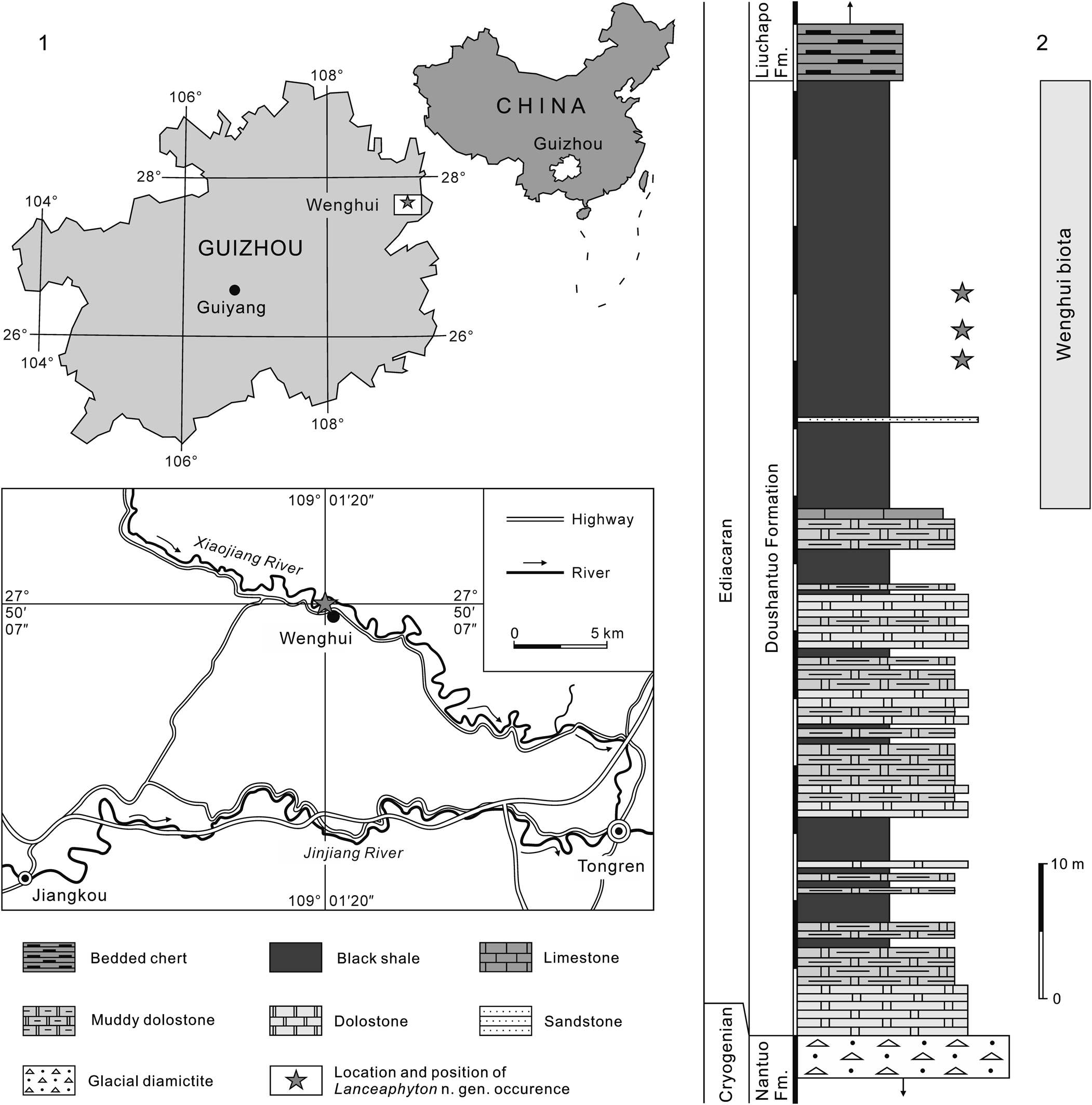

The Ediacaran Wenghui biota (see Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Huang2007), from black shales of the upper Doushantuo Formation in northeastern Guizhou, South China (Fig. 1), is preserved as carbonaceous compressions, including abundant and diverse macroscopic algae, metazoans, and a few ichnofossils (e.g., Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Chen, Peng, Yu, He, Wang, Yang, Wang and Zhang2004; Wang et al., Reference Wang, He, Yu, Zhao, Peng, Yang and Zhang2005, Reference Wang, Wang and Huang2007, Reference Wang, Wang and Huang2008, Reference Wang, Zhao, Yang and Wang2009, Reference Wang, Chen, Wang and Huang2011, Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2014, Reference Wang, Du, Komiya, Wang and Wang2015a, Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2016a, Reference Wang, Wang and Dub, Reference Wang, Wang and Du2017, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang, Zhao and Liu2020b; Wang and Wang, Reference Wang and Wang2006, Reference Wang and Wang2008, Reference Wang and Wang2011, Reference Wang and Wang2018; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yin, Liu, Duan and Gao2008a, Reference Tang, Yin, Stefan, Liu, Wang and Gaob, Reference Tang, Yin, Liu, Gao and Wang2009, Reference Tang, Bengtson, Wang, Wang and Yin2011; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Gehling, Xiao, Zhao and Droser2008). In this biota, a lance-like macroalga was regarded without systematic description as a holdfast of an unnamed macroalga (see Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Huang2007, Reference Wang, Zhao, Yang and Wang2009, Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2014, Reference Wang, Du, Komiya, Wang and Wang2015a, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a). After examination of all collected specimens, we observe that the lance-like macroalga has not only an unbranching thallus and a holdfast (including a rhizome and many filamentous rhizoids), but also a thickened carbonaceous mass with distinct boundaries and smooth intergradation in the center of the lower thallus and the rhizome. In this paper, we describe the lance-like macroalga and discuss the tissue and/or organ differentiation of the Ediacaran macroalga.

Figure 1. (1) Ediacaran Doushantuo Formation stratigraphic section at Wenghui, Jiangkou, northeastern Guizhou, South China. (2) The lance-like pithy macroalga Lanceaphyton n. gen. described in this paper is found in upper Doushantuo black shales in Wenghui section of northeastern Guizhou.

Geologic setting

In the Wenghui section (27°50′07″N, 109°01′20″E) of Jiangkou, Guizhou Province, China (Fig. 1.1), the Ediacaran Doushantuo Formation (>71 m thick) is composed of cap dolostones in the lower part, dolostones and muddy dolostones with intercalated black shales in the middle part, and fossiliferous black shales in the upper part. It overlies glacial diamictites of the Nantuo Formation and underlies bedded cherts of the Liuchapo Formation. In addition to the lance-like macroalga, abundant and diverse carbonaceous macrofossils (i.e., the Wenghui biota) have been found from the upper Doushantuo black shales (Fig. 1.2). Previous researchers (e.g., Wang et al., Reference Wang, He, Yu, Zhao, Peng, Yang and Zhang2005, Reference Wang, Zhao, Yang and Wang2009, Reference Wang, Chen, Wang and Huang2011, Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2014, Reference Wang, Wang and Du2016b, Reference Wang, Wang and Du2017, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang, Zhao and Liub; Wang and Wang, Reference Wang and Wang2006, Reference Wang and Wang2011, Reference Wang and Wang2018) suggested that the Wenghui biota lived in a low-energy environment with occasional water currents and was preserved either in situ or nearby their growth position.

The Wenghui biota can be correlated paleontologically with another Ediacaran macrobiota, the Miaohe biota (e.g., Chen and Xiao, Reference Chen and Xiao1991, Reference Chen and Xiao1992; Ding et al., Reference Ding, Zhang, Li and Dong1992, Reference Ding, Li, Hu, Xiao, Su and Huang1996; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiao and Yuan1994, Reference Chen, Chen and Xiao2000; Steiner, Reference Steiner1994; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Li and Chen1995; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Tong, An, Hu, Tian, Guan and Xiao2019) from the upper Doushantuo black shales at Miaohe, Zigui, western Hubei, South China, which shares many common species (see Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Wang and Huang2011, Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2016a, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Tong, An, Hu, Tian, Guan and Xiao2019). The lithological succession of the Doushantuo Formation in northeastern Guizhou is similar to that of western Hubei (e.g., Qin et al., Reference Qin, Zhu, Xie, Chen, Wang, Wang, Yin, Zheng, Qin, Zhu, Chen, Luo, Zhu, Wang and Qian1984; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Qin, Zhu, Chen, Xie, Wang and Han1987; Liu and Xu, Reference Liu and Xu1994; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Zhang and Yang2007; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Shi, Zhang, Wang and Xiao2011; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Huang, Chen, Hou, Yang and Du2012). The macrofossil-bearing black shales of the upper Doushantuo Formation at both the Wenghui and Miaohe areas were dated to ca. 560–551 Ma (see Condon et al., Reference Condon, Zhu, Bowring, Wang, Yang and Jin2005; Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Komiya, Lyons, Bates, Gordon, Romaniello, Jiang, Creaser, Xiao, McFadden, Sawaki, Tahata, Shu, Han, Li, Chu and Anbar2015; Li et al., Reference Li, Planavshy, Shi, Zhang, Zhou, Cheng, Tarhan, Luo and Xie2015; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Du2017, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a; Wang and Wang, Reference Wang and Wang2018).

Material and methods

All studied specimens are preserved as carbonaceous compressions and were collected from black shales of the upper Doushantuo Formation in the Wenghui section of northeastern Guizhou, South China. The studied specimens are preserved together with various macrofossils (e.g., Baculiphyca Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Li and Chen1995, emend. Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002; Gesinella Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Erdtmann and Chen1992; Cucullus Steiner, Reference Steiner1994; Longifuniculum Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Erdtmann and Chen1992; Zhongbaodaophyton Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiao and Yuan1994, emend. Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2015b) on the same bedding plane. They were obtained only by mechanically cleaving the bedding planes (i.e., not processed in other ways).

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

The studied specimens are housed in the College of Resource and Environment Engineering (CREE), Guizhou University (GU), China.

Systematic paleontology

Genus Lanceaphyton new genus Ye Wang and Yue Wang

Type species

Lanceaphyton xiaojiangensis n. gen. n. sp. Ye Wang and Yue Wang.

Diagnosis

As for the type species by monotypy.

Occurrence

Ediacaran, Upper Doushantuo Formation, South China.

Etymology

From the Latin lancea and phyton, with reference to the lance-like pattern of this macroalga.

Remarks

The lance-like Lanceaphyton n. gen. is similar to Baculiphyca Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Li and Chen1995, emend. Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002, in the elongate and unbranching thallus, but Baculiphyca has a clavate thallus tapering down to the base and connecting with a globular rhizome. The clavate macroalga Baculiphyca emended by Xiao et al. (Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002) was combined with other genera (including Diaoyapolotes Chen in Chen and Xiao, Reference Chen and Xiao1991; Miaohenella Ding in Ding et al., Reference Ding, Zhang, Li and Dong1992; Eoscytosiphon Ding in Ding et al., Reference Ding, Zhang, Li and Dong1992; ?Gesinella Steiner, Reference Steiner1994; and Baculiphyca Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Li and Chen1995), which broadened its diagnosis to include both rhizoidal and globose holdfasts (see Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002, p. 353). With a cylindrical or tubular structure within the lower thallus (Chen and Xiao, Reference Chen and Xiao1991; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiao and Yuan1994; Ding et al., Reference Ding, Li, Hu, Xiao, Su and Huang1996; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Huang2007, 2020a), the clavate Baculiphyca differs from Lanceaphyton n. gen. in having a thickened carbonaceous mass in the center of both the lower thallus and the tapering rhizome. Lanceaphyton n. gen. is different from Gesinella Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Erdtmann and Chen1992, in that the latter has a large-sized thallus with a basal divergence angle and no cylindrical structure in the center of the thallus and rhizome. The new genus is characterized by the thickened carbonaceous mass within the tapering rhizome and the lower part of the unbranching thallus of nearly uniform width, which distinguish it from other Precambrian macroalgae.

Lanceaphyton xiaojiangensis new species Ye Wang and Yue Wang

Figures 2.1–2.8, 3.1–3.10

- Reference Chen and Xiao1991

Diaoyapolites longiconidalis n. gen. n. sp. Chen [nom. nud.] in Chen and Xiao, p. 320, pl. III, figs. 5, 6.

- Reference Chen and Xiao1992

Diaoyapolites longiconidalis [nom. nud.]; Chen and Xiao, p. 519, pl, III, figs. 1, 2.

- Reference Chen, Xiao and Yuan1994

Diaoyapolites longiconidalis [nom. nud.]; Chen et al., p. 394, pl, II, fig. 1.

- Reference Yuan, Li and Chen1995

Diaoyapolites longiconidalis [nom. nud.]; Yuan et al., p. 97, pl. II, fig. 7.

- Reference Ding, Li, Hu, Xiao, Su and Huang1996

Miaohenella conica n. sp. Ding [nom. nud.] in Ding et al., p. 86, pl. 27, fig. 2.

- Reference Wang, Wang and Huang2007

Unnamed holdfast forms [gen. et sp. indet.] Wang et al., p. 836, pl. II, fig. 25.

- Reference Wang, Zhao, Yang and Wang2009

Macroalgal holdfast [gen. et sp. indet.] Wang et al., fig. 2.6.

- Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2014

Macroalgal holdfast [gen. et sp. indet.] Wang et al., fig. 4r.

- Reference Wang, Du, Komiya, Wang and Wang2015a

Macroalgal holdfast [gen. et sp. indet.] Wang et al., fig. 5E.

- Reference Wang, Wang, Tang, Zhao and Liu2020b

Unnamed macroalga [gen. et sp. indet.] Wang et al., p. 9, figs. 5L–N.

Figure 2. Lanceaphyton xiaojiangensis n. gen. n. sp. holotype and paratype. (1–3) holotype, JK50-1017A; (1) complete specimen; (2) showing the rhizome-thallus transition; (3) a magnified view of the holdfast. (4, 5) holotype, JK50-1017B; (4) complete specimen; (5) a magnified view of the holdfast; (6–8) paratype, WG-10-091; (6) complete specimen; (7) showing the disappearance of the thickened carbonaceous mass within the thallus; (8) showing the rhizome-thallus transition. Abbreviations: cc, central carbonaceous mass; sc, side carbonaceous mass.

Figure 3. Pithy macroalga Lanceaphyton xiaojiangensis n. gen. n. sp. from the upper Doushantuo Formation, Wenghui, Jiangkou, Guizhou, China. (1, 2) WG-08-088 (1) complete specimen; (2) a magnified view of the holdfast; (3, 4) WH-P-01091 (3) complete specimen; (4) a magnified view of the rhizome-thallus transition; (5, 6) WH-P-03002 (5) complete specimen; (6) showing the rhizome-thallus transition; (7) WH-P-02115; (8–10) JK54-0086 (8) complete specimen; (9) a magnified view of the thallus; (10) a magnified view of the rhizome-thallus transition. Abbreviations: cc, central carbonaceous mass; sc, side carbonaceous mass.

Diagnosis

Lance-like carbonaceous compression with an elongate and unbranching thallus of nearly uniform width, a tapering rhizome, numerous filamentous rhizoids, and a thickened carbonaceous mass within the rhizome and the lower thallus.

Occurrence

Black shales of the upper Doushantuo Formation, Wanghui section of northeastern Guizhou; Miaohe section of western Hubei, South China.

Description

Lance-like carbonaceous compression with an unbranching thallus and a holdfast. The rod-like thallus, which is incompletely preserved, widens slightly upwards, nearly uniform in width (Figs. 2.1, 2.4, 2.6, 3.1, 3.3, 3.5, 3.7, 3.8). The preserved thallus typically is straight (Figs. 2.1, 2.4, 3.1) or rigid flex (Figs. 2.6, 3.3–3.8). The holdfast consists of a tapering rhizome connecting with the thallus and numerous filamentous rhizoids growing on the rhizome (Figs. 2.1–2.6, 2.8, 3.1–3.8, 3.10). Thickened carbonaceous masses can be observed in the center and two sides of the thallus and rhizome, respectively. The central carbonaceous mass is commonly preserved in three dimensions (Figs. 2.6–2.8, 3.1–3.6, 3.8–3.10) with distinct boundaries and smooth intergradation (Figs. 2.1–2.8, 3.1–3.10), like the thallus and rhizome in morphology. The central carbonaceous mass extends down to near the end of the rhizome (Figs. 2.4, 2.5, 3.1–3.4); while its density gradually is decreasing upward to thin in the middle part of the thallus (Figs. 2.6, 2.7, 3.3). The side carbonaceous mass is faintly visible as a thin wall covering the thallus and rhizome (Figs. 2.2, 2.3, 2.5–2.8, 3.2, 3.4, 3.9, 3.10). In some specimens, the side carbonaceous mass shows a woven-like edge in the rhizome (Figs. 2.2, 2.3, 3.2). The thallus is 41.3 mm and 3.4 mm in preserved maximum length and width, respectively. The width at the rhizome-thallus transition is 0.7–2.8 mm. The rhizome maximum preserved length is 10.1 mm. Near the rhizome-thallus transition, the width of the central carbonaceous mass is 0.4–1.2 mm, accounting for 0.42–0.58 of the thallus width.

Etymology

After the Xiaojiang River near the Wenghui section of Jiangkou, northeastern Guizhou, South China.

Materials

Twelve specimens (JK49-1006, JK50-1017, JK54-0009, JK54-0086, JK54-0018, JK58-0003, WH-P-01091, WH-P-02115, WH-P-03002, WH-P-03049, WG-10-019, WG-08-088), seven of which are illustrated.

Remarks

Lanceaphyton xiaojiangensis n. gen. n. sp. is similar to Baculiphyca taeniata Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Li and Chen1995, emend. Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002, but the former has a thallus of nearly uniform width, a distinctly tapering rhizome, and a central carbonaceous mass within both the rhizome and lower thallus. Diaoyapolotes longiconoidalis Chen in Chen and Xiao, Reference Chen and Xiao1991, a synonym of B. taeniata (see Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002), was described as having a tubular structure within its lower part (see Chen and Xiao, Reference Chen and Xiao1991; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiao and Yuan1994; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Li and Chen1995). All five species of Miaohenella (M. typicura Ding in Ding et al., Reference Ding, Zhang, Li and Dong1992; M. eleganta Ding in Ding et al., Reference Ding, Zhang, Li and Dong1992; M. conica Ding in Ding et al., Reference Ding, Li, Hu, Xiao, Su and Huang1996; M. rhomba Ding in Ding et al., Reference Ding, Li, Hu, Xiao, Su and Huang1996; and M. nana Ding in Ding et al., Reference Ding, Li, Hu, Xiao, Su and Huang1996), which were considered synonymous with B. taeniata (see Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002), have a cylindrical structure within the stipe (Ding et al., Reference Ding, Zhang, Li and Dong1992, Reference Ding, Li, Hu, Xiao, Su and Huang1996). The cylindrical structure was also observed in the center of the stipe of B. taeniata (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Huang2007, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a). Ye et al. (Reference Ye, Tong, An, Hu, Tian, Guan and Xiao2019) suggested that, based on the measurement of many specimens, the basal divergence angle of the clavate thallus of B. taeniata ranges from 2.0–15.6°, with an average of 7.2°. In other words, B. taeniata has a clavate thallus with a distinct divergence angle in the base, a globular rhizome connecting the thallus, and a cylindrical or tubular structure only within the lower thallus, which warrant its differentiation from the new species. Similarly, L. xiaojiangensis n. gen. n. sp. is different from B. brevistipitata Ye et al., Reference Ye, Tong, An, Hu, Tian, Guan and Xiao2019, in that the latter's thallus consists of a broad laminar blade and a terete stipe connecting with a globular rhizome. However, the holotype (see Chen and Xiao, Reference Chen and Xiao1991, pl. IV, figs. 3, 4) of D. longiconoidalis is different from the other two specimens (see Chen and Xiao, Reference Chen and Xiao1991, pl. IV, figs. 5, 6) in that the latter specimens have a rod-like thallus of nearly uniform width and a tapering rhizome, not a globular rhizome. For this reason, the latter two specimens do not correspond to the diagnosis of B. taeniata, as emended by Xiao et al. (Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002). With an unbranching thallus of nearly uniform width, a distinctly tapering rhizome growing out many filamentous rhizoids, and a central carbonaceous mass and/or tubular structure within both the rhizome and lower thallus, some Ediacaran macroalgal specimens in previous publications, such as the specimens assigned to D. longiconoidalis (see Chen and Xiao, Reference Chen and Xiao1991, pl. IV, figs. 5, 6; Chen and Xiao, Reference Chen and Xiao1992, pl, III, figs. 1, 2; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiao and Yuan1994, pl, II, fig. 1; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Li and Chen1995, pl. II, fig. 7) and M. conica (see Ding et al., Reference Ding, Li, Hu, Xiao, Su and Huang1996, pl. 27, fig. 2), are assigned to L. xiaojiangensis n. gen. n. sp. rather than to B. taeniata Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Li and Chen1995, emend. Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002.

The lance-like Lanceaphyton xiaojiangensis n. gen. n. sp. is similar to Gesinella hunanensis Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Erdtmann and Chen1992, in the unbranching thallus and the tapering rhizome with numerous filamentous rhizoids, but the latter has a larger-sized thallus with a distinct divergence angle at the base and no central carbonaceous mass and/or tubular structure within the thallus and rhizome. Lanceaphyton xiaojiangensis n. gen. n. sp. is different from Discusphyton wenghuiensis Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Du2017, and Sitaulia minor Singh et al., Reference Singh, Babu and Shukla2009, in that the latter two have a thallus with a divergence angle at the base and a disc-like rhizoid growing on a globular rhizome. Lanceaphyton xiaojiangensis n. gen. n. sp. differs from other Precambrian unbranching macroalgae (for example, Flabellophyton lantianensis Steiner, Reference Steiner1994, Sinoclindra linearis Ye et al., Reference Ye, Tong, An, Hu, Tian, Guan and Xiao2019, S. yunnanensis Chen and Erdtmann, Reference Chen, Erdtmann, Simonetta and Conway Morris1991, Tawuia dalensis Hofmann in Hofmann and Aitken, Reference Hofmann and Aitken1979, and Vendotaenia antiqua Gnilovskaya, Reference Gnilovskaya1971) in its stiff thallus of nearly uniform width, tapering rhizome with many filamentous rhizoids, and thickened carbonaceous mass or tubular structure in the center of the rhizome and lower thallus.

Structure features and their bio-functional interpretations

Pith and outer tissues

In previous publications, a thickened carbonaceous mass or tubular structure within the thallus of Baculiphyca was interpreted as a natural biotic structure (pith) (see Ding et al., Reference Ding, Li, Hu, Xiao, Su and Huang1996; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Huang2007, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a) or an abiotic structure (diagenetic material) (see Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Tong, An, Hu, Tian, Guan and Xiao2019). Similarly, a cylindrical carbonaceous mass within the stipe and rhizome of Zhongbaodaophyton Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiao and Yuan1994, emend. Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2015b, and Wenghuiphyton Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Huang2007, possessing the distinct shape and boundary in high density and smooth intergradation patterns, was interpreted as a pith of biological organs (see Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Huang2007, Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2015b, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a).

In the rhizome and lower thallus of the compression Lanceaphyton n. gen., the central carbonaceous mass structure has a stable form and distinct boundary, and is similar to the rhizome and thallus in morphology, but smaller in size (Figs. 2.1–2.8, 3.1–3.10). In addition, the central carbonaceous mass gradually decreases upward, disappearing in the middle part of the thallus (Figs. 2.6, 2.7, 3.3), while it extends down and tapers into a tapering rhizome (Figs. 2.4, 2.5, 3.1–3.4). With a stable form, a distinct boundary, and smooth intergradation pattern, the central structure formed by the high-density carbonaceous mass can be interpreted as an original biological structure rather than a diagenetically abiotic structure. Moreover, the central carbonaceous mass is preserved as a three-dimensional cylinder and/or cone in some specimens (Figs. 2.6–2.8, 3.1–3.6, 3.8–3.10), confirming its originally cylindrical and conical nature in the lower thallus and the rhizome, respectively, and implying that it is composed of high-density organic matter rather than an abiotic or diagenetic material. Therefore, the Ediacaran macroalga Lanceaphyton n. gen. possesses a pith within the rhizome and lower thallus, which is composed a high-density tissue (perhaps mechanical tissue) (Fig. 4). The macroalgal pith may be a critical structure keeping the rhizome in place and reinforcing the support effect of the stipe or the lower thallus.

Figure 4. Reconstruction and principal structures of Lanceaphyton xiaojiangensis n. gen. n. sp.

The thickened carbonaceous mass is also found in the outermost sides of the thallus and rhizome, visible as a thin wall (Figs. 2.2, 2.3, 2.5–2.8, 3.2, 3.4, 3.9, 3.10). Similarly, it can be interpreted as a high-density organic tissue covering the thallus and rhizome. In other words, Lanceaphyton n. gen. has an outer tissue that may be epidermis and/or cortex composed of dense cells (Fig. 4) that provided a protective function and/or conducted photosynthesis. The Ediacaran macroalgal epidermis and/or cortex was also described in Baculiphyca (see Ding et al., Reference Ding, Li, Hu, Xiao, Su and Huang1996; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Huang2007) and is a normal structure of modern algae (e.g., Dromgoole, Reference Dromgoole1982; Ito and Miyoshi, Reference Ito and Miyoshi1993; Fournet et al., Reference Fournet, Ar Gall, Deslandes, Huvenne, Sombret and Floc'h1997; Husiman et al., Reference Huisman, De Clerck, Van Reine and Borowitzka2011; Sherwood et al., Reference Sherwood, Necchi, Carlile, Laughinghouse, Fredericq and Sheath2012; Croce and Parodi, Reference Croce and Parodi2013).

Holdfast and thallus

Previous researchers suggested that the Ediacaran Wenghui biota lived in a relatively low-energy environment, with occasional water currents (e.g., Wang and Wang, Reference Wang and Wang2006, Reference Wang and Wang2011, Reference Wang and Wang2018; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Wang and Huang2011, Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2014, Reference Wang, Du, Komiya, Wang and Wang2015a, Reference Wang, Wang and Du2017, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang, Zhao and Liu2020b). In the Wenghui biota, the macroalgal holdfast commonly is preserved together with its thallus on the same bedding plane of black shales, meaning that the holdfast easily could have been lifted from water-rich muddy sediments by seafloor currents (see Wang and Wang, Reference Wang and Wang2006, Reference Wang and Wang2018; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Du, Komiya, Wang and Wang2015a, Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wangb, Reference Wang, Wang and Du2016b, Reference Wang, Wang and Du2017, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a). In other words, the compression pattern of macroalgal holdfasts was influenced by the lifted position before being buried. When the macroalgal holdfast had been uprooted and/or removed from the muddy sediments, its thallus and holdfast were preserved on the same bedding plane.

The Ediacaran macroalga Lanceaphyton n. gen. consists of two parts: a thallus that grew over the sediment surface for sunlight uptake and a holdfast that grew into the sediments to keep the thallus fixed on the seafloor. However, it is difficult to determine whether the carbonaceous compression on the same bedding plane is the thallus or the holdfast. Morphologically, the holdfast of Lanceaphyton n. gen. commonly consists of a tapering pithy rhizome and many filamentous rhizoids growing on the rhizome, while the unbranching thallus of nearly uniform width is a rod-like organ/tissue that can be divided into an upper pithless thallus and a lower pithy thallus (pithy stipe) connecting with the pithy rhizome (Fig. 4). The tapering pithy rhizome with a sharp top (Figs. 2.4, 2.5, 3.1–3.4) may have been conducive for insertion into and growth in the sediments, with the numerous filamentous rhizoids possibly having had the ability to grow in the gaps between sediment grains and to keep the rhizome in place. In addition, the increasingly horizontal bedding in the upper Doushantuo fossiliferous black shales implies that macroalgal holdfasts grew in different layers of sediments. For the holdfast of Lanceaphyton n. gen., the woven-like outer tissue in the rhizome (Figs. 2.2, 2.3, 3.2) and the symmetrical rhizoids of unequal lengths (Figs. 2.1–2.5, 3.1, 3.2) might be related to the different sediments in which they were growing, which requires further research. Moreover, we note that the rhizome and stipe (lower thallus) of Lanceaphyton n. gen. are nearly straight and/or rigid bow-shape (Figs. 2.1–2.8, 3.1–3.10), suggesting that they may have been originally hardened in nature. The stipe with a cylindrical pith (perhaps mechanical tissue) not only would have strengthened the lodging resistance but also would have supported the upper pithless thallus to stay in the water column for photosynthesis.

Taxonomic assignment of Lanceaphyton n. gen.

Lanceaphyton n. gen. with a thallus and a holdfast is a centimeter-scale macrofossil with different organ and/or issue features (Fig. 4). Generally, tissue and/or organ differentiation is considered as a key trait of eukaryotic algae or metaphytes (e.g., Du and Tian, Reference Du and Tian1985a, Reference Du and Tianb; Liu and Du, Reference Liu and Du1991; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Li and Chen1995, Reference Yuan, Chen, Xiao, Zhou and Hua2011; Zhu and Chen, Reference Zhu and Chen1995; Ding et al., Reference Ding, Li, Hu, Xiao, Su and Huang1996; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chen and Xiao2000; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002; Wang and Wang, Reference Wang and Wang2006; Xiao, Reference Xiao, Trueba and Montufar2013; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Wang2015b, Reference Wang, Wang and Du2016b, Reference Wang, Wang and Du2017, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a). In addition, no filamentous structure has been observed in the thallus and holdfast of Lanceaphyton n. gen., except the filamentous rhizoids growing on the rhizome. Like Baculiphyca, which is regarded as a macroalga (e.g., Chen and Xiao, Reference Chen and Xiao1991; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiao and Yuan1994, Reference Chen, Chen and Xiao2000; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Li and Chen1995, Reference Yuan, Li and Cao1999; Ding et al., Reference Ding, Li, Hu, Xiao, Su and Huang1996; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Yuan, Steiner and Knoll2002; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Huang2007, Reference Wang, Du, Komiya, Wang and Wang2015a, Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yin, Liu, Duan and Gao2008a; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Tong, An, Hu, Tian, Guan and Xiao2019), Lanceaphyton n. gen. is a macroscopic alga rather than colonial bacterium or sulfur bacterium. Moreover, the Ediacaran macroalga Lanceaphyton n. gen. has various tissues and organs to serve different biofunctions (e.g., the holdfast acting for fixation, the pithy stipe supporting the upper thallus for photosynthesis, the pith reinforcing the biofunctions of the stipe and rhizome, and the outer tissue serving for protection and/or conducting photosynthesis). The Lanceaphyton-type holdfast (i.e., the pithy cone-type holdfast of Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a) was considered to be a more advanced holdfast in the evolution of macroalgal holdfasts, which may have originated from the Baculiphyca-type holdfast with pithy stipe and pithless rhizome (see Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Tang and Zhao2020a). Thus, we suggest that Lanceaphyton n. gen. is a high-level metaphyte or eukaryotic macroalga. In addition, the pith of Lanceaphyton n. gen., which accounts for about half of the width of the thallus and the rhizome, is sometimes preserved in three dimensions (Figs. 2.6–2.8, 3.1–3.6, 3.8–3.10) with a distinct boundary. In modern macroalgae, quite a lot of algal bodies of phaeophytes contain epidermis, cortex, and pith. A thick pith commonly is one of the important features of phaeophytes, differentiating them from rhodophytes and chlorophytes with filamentous pith and from other macroalgae without pith. Lanceaphyton n. gen. is morphologically similar to phaeophytes. However, morphological features are not taken as the primary and exclusive basis in the taxonomy of modern algae (Lee, Reference Lee2018), and a rapid diversification of brown algae was considered to have occurred within the Mesozoic in the time-calibrated phylogeny (Silberfeld et al., Reference Silberfeld, Leigh, Verbruggen, Cruaud, de Reviers and Rousseau2010). Unfortunately, cellular details are not observed in the specimens, therefore the phylogenetic affinity of Lanceaphyton n. gen. cannot be fully resolved in this study.

Conclusions

The macroalga Lanceaphyton xiaojiangensis n. gen. n. sp. has been collected from the upper Doushantuo black shales (ca. 560–551 Ma) of the Ediacaran in South China. The lance-like macroalga not only possessed a pith (perhaps mechanical tissue) and outer tissue (perhaps epidermis and/or cortex), but also was significantly differentiated into an unbranching thallus (including the upper thallus without pith and lower stipe with pith) and holdfast (including a tapering pithy rhizome and numerous filamentous rhizoids). The thallus, which is of nearly uniform width, mainly served to conduct photosynthesis, whereas the lower stipe has a cylindrical pith that supported the upper pithless thallus. In the holdfast, the tapering pithy rhizome grew down into the sediments and the filamentous pithless rhizoids dispersed in the sediments. With differentiated tissues and organs, especially the thick pith accounting for about half of the width of the rhizome and stipe, Lanceaphyton n. gen. represents as a high-level eukaryotic macroalga, morphologically similar to phaeophytes, that lived on the seafloor. However, the phylogenetic affinity of Lanceaphyton n. gen. requires further research owing to the absence of preserved microstructural details.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 41762001) and the Science and Technology Project of Guizhou Province, China (grant No. 2017-5788). The authors thank Bruce Runnegar and two anonymous reviewers for constructive reviews and comments that improved this paper greatly.