Introduction

The Hopping Hotspots Hypothesis (Renema et al., Reference Renema, Bellwood, Braga, Bromfield, Hall, Johnson, Lunt, Meyer, McMonagle, Morley, O'Dea, Todd, Wesselingh, Wilson and Pandolfi2008) argues that the tropical hotspot of shallow-marine biodiversity has moved during the past 50 million years from the Western Tethys (>40 Ma), through the Arabian region (~30–20 Ma), to its present position in the Indo-Australian Archipelago (IAA: <20 Ma). The southern tip of India occupied a central position between the Arabian and IAA biodiversity hotspots during the early Miocene and is thus an important area to study the origins of the huge modern marine biodiversity in the IAA.

This study describes an early Miocene (Burdigalian) ostracode fauna from the shallow marine Quilon Formation in Kerala (southwestern India). Indian shallow marine ostracodes have well been investigated, especially since the 1960s, as summarized by the checklist in Jain (Reference Jain1981) and the atlases in 1990–2000s (Bhandari, Reference Bhandari1996; Bhandari et al., Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001). In Indian ostracode papers, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images appeared in 1980s. The atlases show SEM images, but detailed morphological characters are not always clear and internal views including muscle scars and hingement are seldom shown. Since the early 2000s, after publication of the atlases, comprehensive taxonomic update or re-evaluation has not been done for ~20 years. Herein, we re-evaluate the taxonomy of early Miocene ostracodes from southern India based on high-resolution SEM images of external and internal views. We revised the generic assignments of several species and erected one new genus and one new species. We also discuss the paleobiogeographic affinities of the south Indian ostracode fauna with respect to the Hopping Hotspots Hypothesis of Renema et al. (Reference Renema, Bellwood, Braga, Bromfield, Hall, Johnson, Lunt, Meyer, McMonagle, Morley, O'Dea, Todd, Wesselingh, Wilson and Pandolfi2008).

Geological setting

This study was carried out at “Channa Kodi” locality (8°58′36″N, 76°38′08″E) close to Padappakkara village in the southern onshore part of the Kerala Basin (Fig. 1). The Kerala Basin is the southernmost sedimentary basin on the Western Indian passive margin and extends ~600 km parallel to the coastline, bounded by the Tellicherry Arch in the north, the Chargos-Laccadive Ridge in the west, and the Central Indian Ocean Basin in the south. During the Cenozoic, the basin constituted a major depocenter for terrigenous clastic sediments that derived from denudation of the Western Ghats (Campanile et al., Reference Campanile, Nambiar, Bishop, Widdowson and Brown2008). Channa Kodi is the type locality of the fossiliferous Quilon Limestone, which represents patchy carbonate occurrences in the Quilon Formation of the Neogene siliciclastic Warkalli Group (Menon, Reference Menon1967; Vaidyanadhan and Ramakrishnan, Reference Vaidyanadhan and Ramakrishnan2008; Reuter et al., Reference Reuter, Piller, Harzhauser, Kroh, Rögl and Ćorić2011). The Quilon Formation is underlain by the lower Miocene Mayyanad Formation and overlain by the Ambalapuzha Formation of Miocene to Pliocene age (Vaidyanadhan and Ramakrishnan, Reference Vaidyanadhan and Ramakrishnan2008). Palynofloras from the Warkalli Group document marginal marine brackish lagoonal depositional environments as well as brackish and freshwater swamps similar to the present-day Kerala backwaters (Rao and Ramanujam, Reference Rao and Ramanujam1975; Ramanujan, Reference Ramanujan1987; Kern et al., Reference Kern, Harzhauser, Reuter, Kroh and Piller2013; Reuter et al., Reference Reuter, Kern, Harzhauser, Kroh and Piller2013). Facies analysis of the Quilon Limestone at Channa Kodi indicates a shallow marine seagrass environment that had likely developed temporarily during a sea-level rise (Reuter et al., Reference Reuter, Piller, Harzhauser, Kroh, Rögl and Ćorić2011). In accordance with this paleoenvironmental interpretation, Harzhauser (Reference Harzhauser2014) described a highly diverse seagrass-associated gastropod fauna from a weakly lithified, bioclastic carbonate sand of at least 0.3 m thickness, which is exposed ~1 m below the Quilon Limestone at the base of Channa Kodi section (bed 1: Reuter et al., Reference Reuter, Piller, Harzhauser, Kroh, Rögl and Ćorić2011) (Fig. 1). The sediment sample used for this ostracode study (here we call the sample CK-09-02) derived also from bed 1 (Fig. 1). Based on the associated benthic foraminiferan fauna, which is characterized by mesophotic taxa (Brigulio and Rögl, Reference Brigulio and Rögl2018; Rögl and Brigulio, Reference Rögl and Brigulio2018), it has been recently suggested that the seagrass fauna was transported from seagrass beds, which grew in ~20–30 m water depth, down to 60–70 m water depth (Brigulio et al., Reference Brigulio, Ćorić and Rögl2018). This paleobathymetric reconstruction, however, has to be taken with caution because it does not consider the attenuation of light in seagrass canopies (e.g., Hedley et al., Reference Hedley, McMahon and Fearns2014) and turbid coastal waters along southern Kerala (Jyothibabu et al., Reference Jyothibabu, Balachandran, Jagadeesan, Karnan, Arunpandi, Naqvi and Pandiyarajan2018).

Figure 1. (1) Locality maps and stratigraphic summary. Red star shows the location of the studied site CK-09-02, close to Padappakkara village. Light-red band indicates the biostratigraphic range and the age of the sample CK-09-02 (19.01–17.75 Ma). See main text for the details of calcareous nannofossil zones. TA: Tellicherry Arch. Charg.-Lacc. Ridge: Chargos-Laccadive Ridge. (2) Columnar section and field photograph of the Channa Kodi type locality. The columnar section is divided into beds 1–4. The sample CK-09-02 is from bed 1. Modified after Reuter et al. (Reference Reuter, Piller, Harzhauser, Kroh, Rögl and Ćorić2011).

The presence of Sphenolithus belemnos Bramlette and Wilcoxon, Reference Bramlette and Wilcoxon1967 in bed 1 (Fig. 1) of the Channa Kodi section (Reuter et al., Reference Reuter, Piller, Harzhauser, Kroh, Rögl and Ćorić2011; Ćorić, Reference Ćorić2019) allows correlation to the Calcareous Nannofossil Miocene Biozone (CNM) 5 of Backman et al. (Reference Backman, Raffi, Rio, Fornaciari and Pälike2012), covering the time interval between 19.01 and 17.75 Ma. This age may be further constrained to 19.01–17.96 Ma because Sphenolithus belemnos shows a sharp decrease in abundance at the top of the biozone, occurring ca. 0.2 Ma prior to the appearance of Sphenolithus heteromorphus Deflandre, Reference Deflandre1953, which defines the top of CNM5 (Backman et al., Reference Backman, Raffi, Rio, Fornaciari and Pälike2012). According to Backman et al. (Reference Backman, Raffi, Rio, Fornaciari and Pälike2012), CNM5 corresponds to Zone CN2 of Okada and Bukry (Reference Okada and Bukry1980) and encompasses most of Zone NN3 of Martini (Reference Martini and Farinacci1971).

Materials and methods

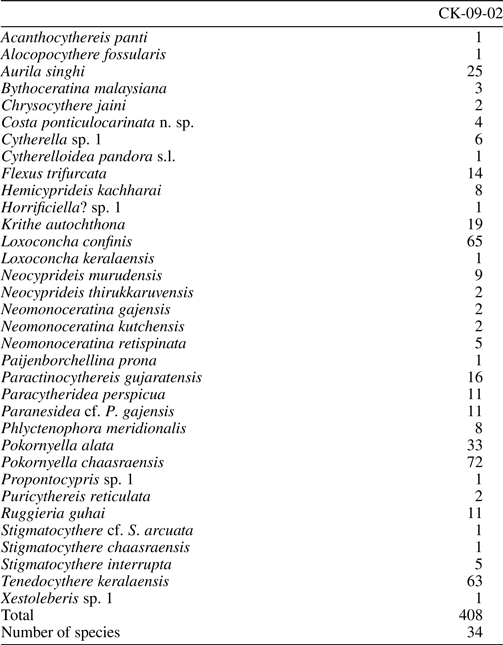

The sample CK-09-02 was wet sieved through a 63 μm sieve and then oven-dried. Because the sample was ostracode-rich, the residue sample was split into fractions using a splitter to obtain >300 specimens. All specimens in a split were picked from the >150 μm size fraction, sorted, identified, and counted on a cardboard slide under a stereomicroscope, Leica S8 APO (Appendix 1). The number of specimens refers to valves and carapaces. Additional specimens were picked from the remaining splits and used for taxonomic purpose (note that these additional specimens are not included in the census count of Appendix 1). Full information about the sample and specimens used for this study is given in Table 1 and Appendices 1 and 2. Uncoated ostracode specimens were digitally imaged with a Hitachi S-3400N variable pressure scanning electron microscope (SEM) in low-vacuum mode, at the Electron Microscope Unit, University of Hong Kong. High-resolution figures of ostracode SEM images (Figs. 2–19) are available at Dryad (http://datadryad.org/; https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.0rxwdbrww). For the higher classification, we mainly referred to the World Ostracoda Database (Brandão et al., Reference Brandão, Angel, Karanovic, Perrier and Meidla2019), Whatley et al. (Reference Whatley, Siveter, Boomer and Benton1993), and Horne et al. (Reference Horne, Cohen, Martens, Holmes and Chivas2002). Abbreviations: LV, left valve; RV, right valve; A-1, last juvenile instar (adult minus one); L, length (mm); H, height (mm).

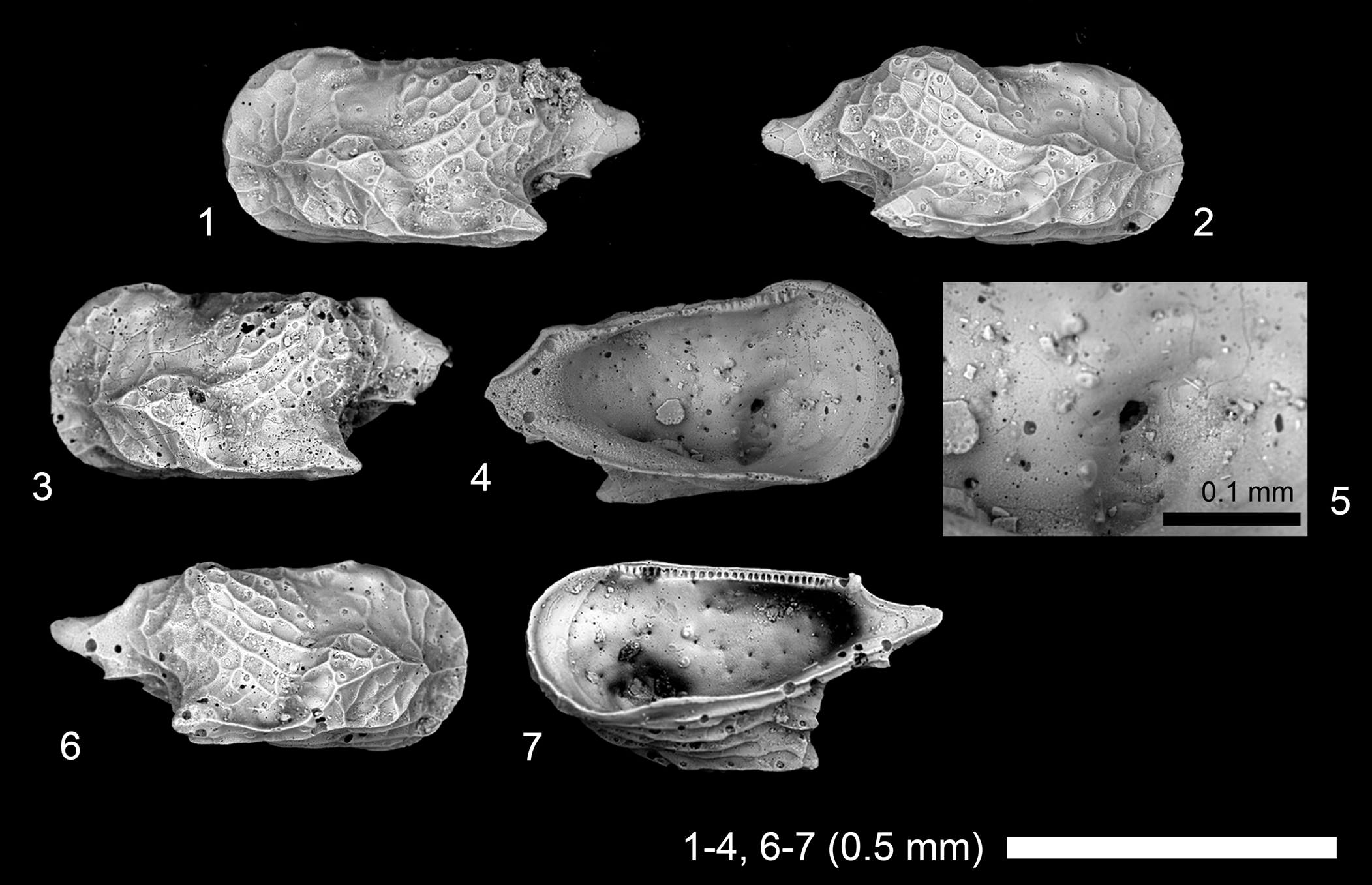

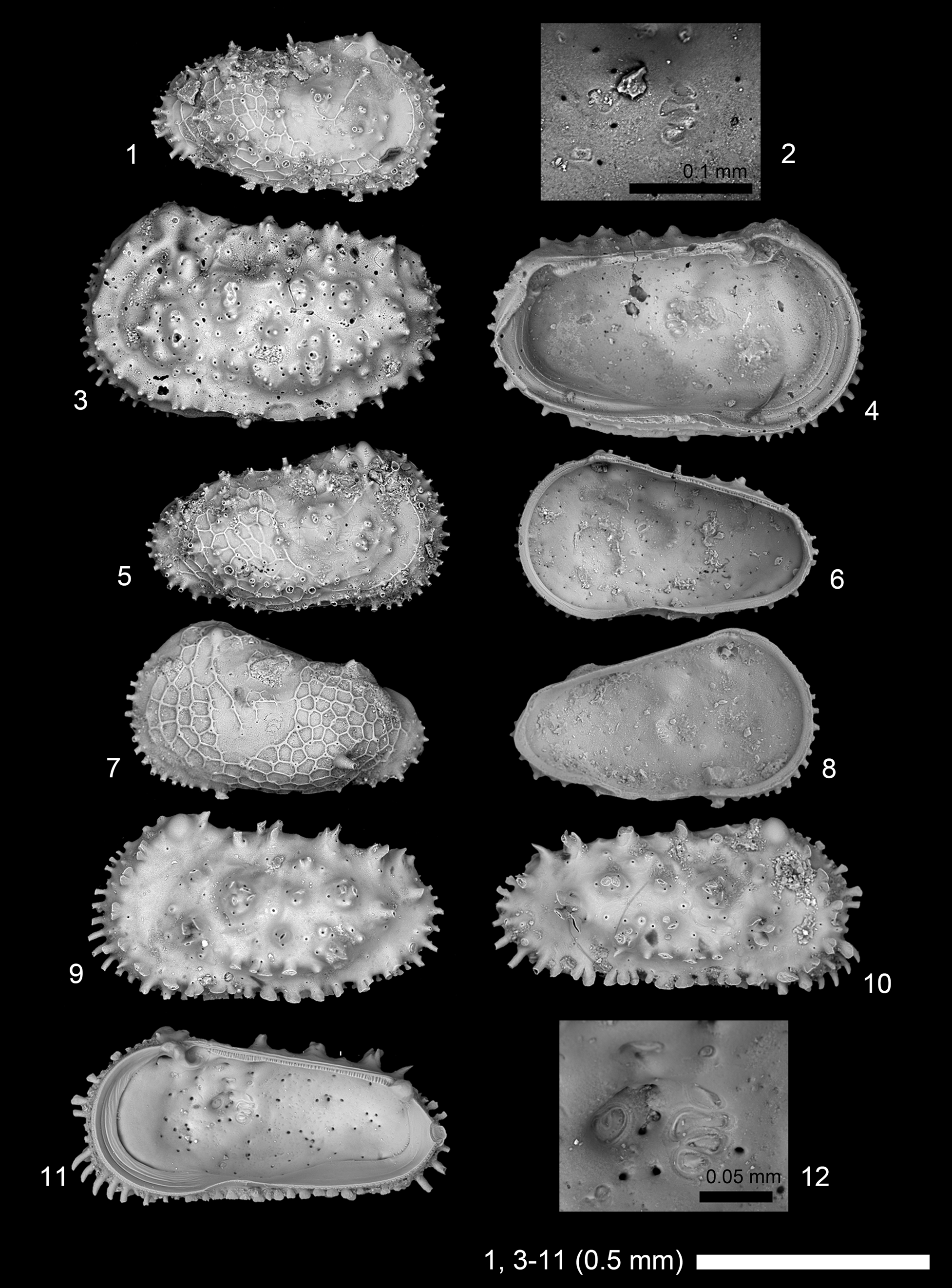

Figure 2. Scanning electron microscope images of ostracode species. (1–4, 6) Cytherella sp. 1: (1), juvenile? LV, 2019/0181/0001 (19A-ck-09-2-001); (2) juvenile? RV, 2019/0181/0002 (19B-ck-09-2-001); (3, 4) juvenile? LV, 2019/0181/0003 (CK-09-02-003); (6) adult? RV, 2019/0181/0004 (19B-ck-09-2-002); (5, 7, 8) Cytherelloidea pandora s.l. (Kornicker, Reference Kornicker1963), adult? RV, 2019/0181/0005 (CK-09-02-054); (9–13) Paranesidea cf. P. gajensis Khosla, Reference Khosla1978: (9), adult RV, 2019/0181/0006 (19A-ck-09-2-015); (10) adult RV, 2019/0181/0007 (CK-09-02-001); (11, 13) adult RV, 2019/0181/0008 (19B-ck-09-2-003); (12) adult LV, 2019/0181/0009 (19B-ck-09-2-004). (1–3, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12) Lateral views; (4, 5, 7, 10, 13) internal views; (5, 13) close-up of subcentral muscle scars.

Table 1. Dimensions of selected specimens.

All specimens are from the sample CK-09-02, southwestern India, early Miocene.

NHMW, catalog numbers of the Natural History Museum Vienna; No., M.Y.'s personal catalog number. T, type (P, paratype; H, holotype); V/C, valve or carapace (L, left valve; R, right valve; C, carapace); A, adult; J, juvenile; F, female; M, male; L, length; H, height.

Repository and institutional abbreviation

Figured specimens are deposited in the Natural History Museum Vienna (NHMW), under catalogue numbers 2019/0181/0001–2019/0181/0115. M.Y.'s personal catalogue numbers are also shown.

Systematic paleontology

Class Ostracoda Latreille, Reference Latreille1802

Subclass Podocopa Sars, Reference Sars1866

Order Platycopina Sars, Reference Sars1866

Superfamily Cytherelloidea Sars, Reference Sars1866

Family Cytherellidae Sars, Reference Sars1866

Genus Cytherella Jones, Reference Jones1849

Type species

Cytherina ovata Roemer, Reference Roemer1841, Lower Cretaceous, northern Germany. Designated by Ulrich (Reference Ulrich1894).

Cytherella sp. 1

Figure 2.1–2.4, 2.6

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

Juveniles of this species are very similar to Cytherella mayyanadensis Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989, but have slightly better-developed surface punctation.

Genus Cytherelloidea Alexander, Reference Alexander1929

Type species

Cytherella williamsoniana Jones, Reference Jones1849, Cretaceous, southeastern England.

Cytherelloidea pandora s.l. (Kornicker, Reference Kornicker1963)

Figure 2.5, 2.7, 2.8

- Reference Kornicker1963

Cytherella pandora Kornicker, p. 69, text-figs. 26–29, 43, 44.

- Reference Baker and Hulings1966

Cytherella pandora; Baker and Hulings, p. 114, pl. 1, fig. 15.

- Reference van den Bold1966

Cytherella sp. aff. C. pandora; van den Bold, pl. 2, fig. 1.

- Reference Keyser and Schöning2000

Cytherella pandora; Keyser and Schöning, p. 569, pl. 1, figs. 6, 7.

Holotype

No. 107612 (National Museum of Natural History, Washington DC, USA) from Great Bahama Bank. Recent.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

This species is very similar to Cytherelloidea pandora (Kornicker, Reference Kornicker1963) described from Modern sediments from Bahama. However, given the large difference in type locality and age, we prefer to call our specimens Cytherelloidea pandora s.l.

Order Podocopida Sars, Reference Sars1866

Suborder Bairdiocopina Gründel, Reference Gründel1967

Superfamily Bairdioidea Sars, Reference Sars1866

Family Bairdiidae Sars, Reference Sars1866

Genus Paranesidea Maddocks, Reference Maddocks1969

Type species

Paranesidea fracticorallicola Maddocks, Reference Maddocks1969, Recent, Madagascar.

Paranesidea cf. P. gajensis Khosla, Reference Khosla1978

Figure 2.9–2.13

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

This species is similar to Paranesidea gajensis Khosla, Reference Khosla1978, but is distinguished by having a less-punctate valve.

Suborder Cypridocopina Jones, Reference Jones1901

Superfamily Cypridoidea Baird, Reference Baird1845

Family Candonidae Kaufmann, Reference Kaufmann1900

Genus Phlyctenophora Brady, Reference Brady1880

Type species

Phlyctenophora zealandica Brady, Reference Brady1880, Recent; type locality not designated. Junior synonym of Macrocypris orientalis Brady, Reference Brady, De Folin and Perier1868, Recent; northern Java: see Whatley and Zhao (Reference Whatley and Zhao1987) and Wouters (Reference Wouters1999).

Phlyctenophora meridionalis (Lubimova and Mohan in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960)

Figure 3.1–3.8

- Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960

Paracypris meridionalis Lubimova and Mohan in Lubimova et al., p. 23, pl. 2, fig. 3.

- Reference Tewari and Tandon1960

Paracypris gajensis Tewari and Tandon, p. 151, text-fig. 2, fig. 3a, b.

- Reference Khosla1978

Phlyctenophora meridionalis; Khosla, p. 261, pl. 2, fig. 7, pl. 6, fig. 1.

- Reference Khosla, Nagori and Kalia1990b

Phlyctenophora meridionalis; Khosla and Nagori, p. 91, pl. 3, fig. 15.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Phlyctenophora meridionalis; Bhandari et al., p. 132, pl. 113, figs. 1, 2.

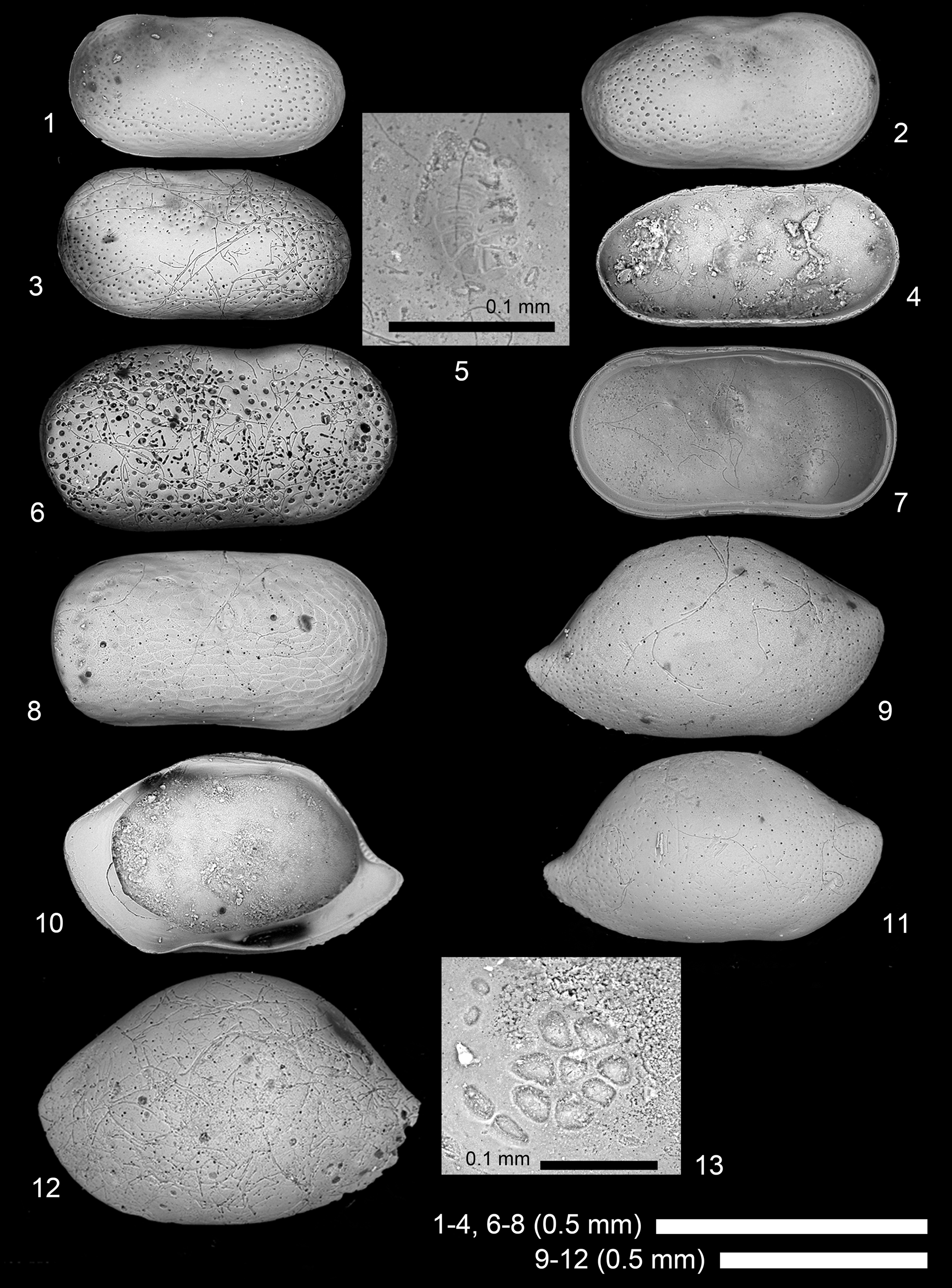

Figure 3. Scanning electron microscope images of ostracode species. (1–8) Phlyctenophora meridionalis (Lubimova and Mohan in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960): (1–3) adult RV, 2019/0181/0010 (CK-09-02-050); (4–7) adult LV, 2019/0181/0011 (CK-09-02-049); (8) juvenile RV, 2019/0181/0012 (CK-09-02-002). (9–11) Propontocypris sp. 1, juvenile LV, 2019/0181/0013 (CK-09-02-034). (12, 13) Bythoceratina malaysiana Whatley and Zhao, Reference Whatley and Zhao1987, adult RV, 2019/0181/0014 (CK-09-02-052). (1, 4, 8, 9, 12) Lateral views; (2, 3, 5–7, 10, 11, 13) internal views; (3, 5, 11) close-up of subcentral muscle scars; (7), close-up of hingement.

Holotype

No. II-6 (Palaeontology Laboratory, Oil and Natural Gas Commission, Dehra Dun, India) from Kutch, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

Internal details of this species have rarely been shown. Our high-resolution SEM images clearly showed six subcentral muscle scars, supplementing Khosla (Reference Khosla1978) who drew five scars only. The distinct arrangement of subcentral muscle scars clearly supports the affiliation of this species to Phlyctenophora (van Morkhoven, Reference van Morkhoven1963).

Superfamily Pontocypridoidea Müller, Reference Müller1894

Family Pontocyprididae Müller, Reference Müller1894

Genus Propontocypris Sylvester-Bradley, Reference Sylvester-Bradley1947

Type species

Pontocypris trigonella Sars, Reference Sars1866, Recent, off the northwest coast of Norway.

Propontocypris sp. 1

Figure 3.9–3.11

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

This species is distinguished from Propontocypris (Propontocypris) sp. cf. P. (P.) herdmani (Scott) of Bhandari et al. (Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001) by having a more slender shape in lateral view.

Suborder Cytherocopina Gründel, Reference Gründel1967

Superfamily Cytheroidea Baird, Reference Baird1850b

Family Bythocytheridae Sars, Reference Sars1866

Genus Bythoceratina Hornibrook, Reference Hornibrook1952

Type species

Bythoceratina mestayerae Hornibrook, Reference Hornibrook1952, Recent, New Zealand.

Bythoceratina malaysiana Whatley and Zhao, Reference Whatley and Zhao1987

Figure 3.12, 3.13

- Reference Whatley and Zhao1987

Bythoceratina malaysiana Whatley and Zhao, p. 341, pl. 3, figs. 3–5.

- non Reference Mostafawi2003

Bythoceratina malaysiana; Mostafawi, p. 69, fig. 41A, B.

- Reference Khosla and Nagori1989

Bythoceratina nealei Khosla and Nagori, p. 51, pl. 12, figs. 8, 9.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Bythoceratina nealei; Bhandari et al., p. 40, pl. 21, figs. 1, 2.

Holotype

No. 1986.124 (Natural History Museum, London, UK) from Malacca Straits. Recent.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

The specimen shown here is much better preserved than the type specimens. Delicate reticulation is visible in our specimen (Fig. 3.12). Mostafawi (Reference Mostafawi2003) considered Bythoceratina nealei Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989 a junior synonym of Bythoceratina malaysiana Whatley and Zhao, Reference Whatley and Zhao1987. We agree with this, but the Persian Gulf specimens reported as Bythoceratina malaysiana by Mostafawi (Reference Mostafawi2003) are not conspecific to Bythoceratina malaysiana in our opinion. Mostafawi's (Reference Mostafawi2003) specimens have less-rectangular outline, less-developed subcentral sulcus, and downward ala compared to Bythoceratina malaysiana.

Family Cytherettidae Triebel, Reference Triebel1952

Genus Flexus Neviani, Reference Neviani1928

Type species

Cythere plicata Münster, Reference Münster1830, “Tertiary,” northwestern Germany (see Weiss, Reference Weiss1983 for SEM images).

Flexus trifurcata (Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960)

Figure 4.1–4.10

- Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960

Cytheretta trifurcata Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., p. 45, pl. 4 fig. 3.

- Reference Tewari and Tandon1960

Cytherelloidea kathiawarensis Tewari and Tandon, p. 160, text-fig. 5, fig. 5.

- Reference Khosla1978

Cytheretta (Flexus) trifurcata; Khosla, p. 271, pl. 3, figs. 3, 4.

- Reference Khosla, Nagori and Kalia1990b

Cytheretta (Flexus) trifurcata; Khosla and Nagori, p. 89, pl. 3, fig. 4.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Cytheretta (Flexus) trifurcata; Bhandari et al., p. 62, pl. 44, figs. 1, 2.

- non Reference Aziz and Al-Shumam2013

Flexus trifurcata; Aziz and Al-Shumam, p. 167, pl. 3, fig. 3.

- non Reference Hawramy and Khalaf2013

Flexus trifurcata; Hawramy and Khalaf, p. 56, pl. 2, fig. 21.

Figure 4. Scanning electron microscope images of ostracode species. (1–10) Flexus trifurcata (Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960): (1) adult RV, 2019/0181/0115 (19B-ck-09-2-005); (2–4) adult RV, 2019/0181/0015 (CK-09-02-007); (5, 6) adult LV, 2019/0181/0016 (CK-09-02-064); (7, 8) adult LV, 2019/0181/0017 (CK-09-02-008); (9, 10) adult RV, 2019/0181/0018 (CK-09-02-063). (11–14) Paijenborchellina prona (Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960), adult RV, 2019/0181/0019 (CK-09-02-065). (15–17) Hemicyprideis kachharai Khosla, Reference Khosla1978: (15) adult RV, 2019/0181/0020 (CK-09-02-032); (16, 17) juvenile? RV, 2019/0181/0021 (19B-ck-09-2-007). (1, 2, 5, 7, 9, 11, 15, 16) lateral views; (3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12–14, 17) internal views; (14) close-up of subcentral muscle scars; (4, 13) close-up of hingement.

Holotype

No. II-24 (Palaeontology Laboratory, Oil and Natural Gas Commission, Dehra Dun, India) from Kutch, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

There is a certain morphological variation in this species. Posterior loop connecting median lateral and ventrolateral ridges can be angular (our specimens; Khosla, Reference Khosla1978; Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960) or rounded (Bhandari et al., Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001). Very broad inner lamella (Fig. 4.6) is a typical character of this family.

Family Cytheridae Baird, Reference Baird1850b

Genus Paijenborchellina Kusnetzova in Mandelstam et al., Reference Mandelstam, Schneider, Kuznetsova and Katz1957

Type species

Paijenborchellina excelens Kusnetzova in Mandelstam et al., Reference Mandelstam, Schneider, Kuznetsova and Katz1957, Lower Cretaceous (Barremian), Caspian coast of Azerbaijan.

Paijenborchellina prona (Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960)

Figure 4.11–4.14

- Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960

Paijenborchella prona Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., p. 43, pl. 4 fig. 1a, b.

- Reference Tewari and Tandon1960

Paijenborchella boldi Tewari and Tandon, p. 159, text-fig. 5, fig. 2a, b.

- Reference Guha1968

Paijenborchella prona.; Guha, p. 213, fig. 4.

- Reference Khosla1978

Paijenborchella (Eupaijenborchella) prona; Khosla, p. 274, pl. 5, fig. 8.

- Reference Khosla and Nagori1989

Paijenborchellina prona; Khosla and Nagori, p. 49, pl. 12, fig. 1.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Paijenborchellina prona; Bhandari et al., p. 118, pl. 100, figs. 1, 2.

Holotype

No. II-22 (Palaeontology Laboratory, Oil and Natural Gas Commission, Dehra Dun, India) from Kutch, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

We found well-preserved specimens of Paijenborchellina prona (Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960). High-resolution SEM images clearly showed that this species has not only primary but also secondary reticulation.

Family Cytherideidae Sars, Reference Sars1925

Genus Hemicyprideis Malz and Triebel, Reference Malz and Triebel1970

Type species

Hemicyprideis aucta Malz and Triebel, Reference Malz and Triebel1970, early Miocene, Germany.

Hemicyprideis kachharai Khosla, Reference Khosla1978

Figure 4.15–4.17

- Reference Khosla1978

Hemicyprideis kachharai Khosla, p. 272, pl. 3, figs. 1, 2, pl. 6, fig. 5.

- Reference Khosla, Nagori and Kalia1990b

Hemicyprideis kachharai; Khosla and Nagori, p. 89, pl. 1, fig. 12.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Hemicyprideis kachharai; Bhandari et al., p. 74, pl. 55, figs. 1, 2.

Holotype

RUGDMF no. 80 (Department of Geology, University of Rajasthan, Udaipur, India) from Gujarat, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

This species is known only from early Miocene of India.

Genus Neocyprideis Apostolescu, Reference Apostolescu1956

Type species

Cyprideis (Neocyprideis) durocortoriensis Apostolescu, Reference Apostolescu1956, lower Eocene, northeastern France.

Neocyprideis murudensis (Bhandari, Khosla, and Nagori, Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001)

Figure 5.1–5.8

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Miocyprideis murudensis Bhandari, Khosla, and Nagori, p. 92, pl. 73 figs. 1, 2.

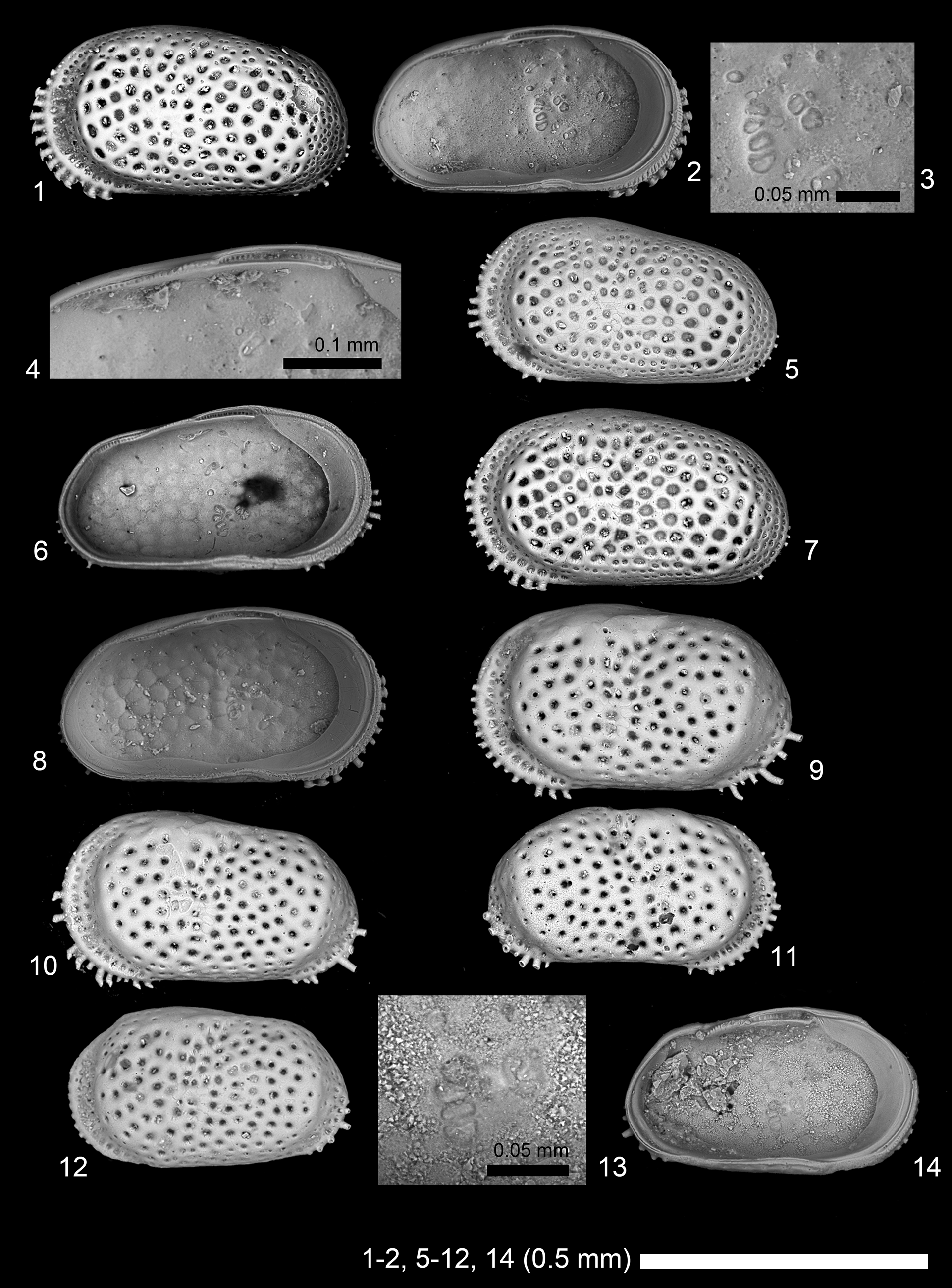

Figure 5. Scanning electron microscope images of ostracode species. (1–8) Neocyprideis murudensis (Bhandari, Khosla, and Nagori, Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001): (1–4) adult LV, 2019/0181/0022 (CK-09-02-037); (5, 6) adult LV, 2019/0181/0023 (19B-ck-09-2-006); (7, 8) adult LV, 2019/0181/0024 (CK-09-02-035). (9–14) Neocyprideis thirukkaruvensis (Guha and Rao, Reference Guha and Rao1976): (9) adult LV, 2019/0181/0025 (19A-ck-09-2-003); (10) adult LV, 2019/0181/0026 (19B-ck-09-2-008); (11) adult RV, 2019/0181/0027 (19B-ck-09-2-009); (12–14) adult LV, 2019/0181/0028 (19B-CK-09-043). (1, 5, 7, 9–12) Lateral views; (2–4, 6, 8, 13, 14) internal views; (3, 13) close-up of subcentral muscle scars; (4) close-up of hingement.

Holotype

IPE/H02/04/8037 (Paleontology Laboratory, Keshava Deva Malaviya Institute of Petroleum Exploration, Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Limited, Dehra Dun, India) from off Bombay, India. Middle Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

Following Titterton and Whatley (Titterton and Whatley, Reference Titterton, Whatley, Hanai, Ikeya and Ishizaki1988, Reference Titterton and Whatley2006; Titterton et al., Reference Titterton, Whatley and Whittaker2001) and Yasuhara et al. (Reference Yasuhara, Hong, Tian, Chong, Okahashi, Littler and Cotton2018), we abstain from separating Neocyprideis Apostolescu, Reference Apostolescu1956 and Miocyprideis Kollmann, Reference Kollmann1960, at least for now, although we believe their generic status merits further consideration, as discussed in Yasuhara et al. (Reference Yasuhara, Hong, Tian, Chong, Okahashi, Littler and Cotton2018). Neocyprideis murudensis (Bhandari, Khosla, and Nagori, Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001) was known only as right lateral views of the holotype and a paratype (Bhandari et al., Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001). Here we showed lateral and internal details of left valves.

Neocyprideis thirukkaruvensis (Guha and Rao, Reference Guha and Rao1976)

Figure 5.9–5.14

- Reference Guha and Rao1976

Miocyprideis thirukkaruvensis Guha and Rao, p. 94, pl. 1, figs. 2–4.

- Reference Khosla, Hanai, Ikeya and Ishizaki1988

Miocyprideis thirukkaruvensis; Khosla, p. 102, pl. 2, figs. 5–8.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Miocyprideis thirukkaruvensis; Bhandari et al., p. 94, pl. 76, figs. 1–4.

Holotype

Repository uncertain.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

Neocyprideis thirukkaruvensis (Guha and Rao, Reference Guha and Rao1976) is similar to Neocyprideis murudensis (Bhandari, Khosla, and Nagori, Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001), but distinguished by having better-developed posteroventral marginal spines and by a lack of secondary reticulation (fine punctation) in ventral, dorsal, and posterior margins.

Type species

Cythere convexa Baird, Reference Baird1850b, Recent, UK.

Aurila singhi Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989

Figure 6

- Reference Khosla1978

Aurila sp. cf. A. amygdala Khosla, p. 262, pl. 3, fig. 5.

- Reference Khosla and Nagori1989

Aurila singhi Khosla and Nagori, p. 36, pl. 7, figs. l–3.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Aurila singhi; Bhandari et al., p. 34, pl. 16, figs. 1–4.

- non Reference Aziz and Al-Shumam2013

Aurila singhi; Aziz and Al-Shumam, p. 166, pl. 2, fig. 5.

Figure 6. Scanning electron microscope images of Aurila singhi Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989. (1, 2) Adult RV, 2019/0181/0029 (19A-ck-09-2-006); (3–5) adult LV, 2019/0181/0030 (CK-09-02-022); (6–8) adult LV, 2019/0181/0031 (19A-ck-09-2-05); (9, 10) adult RV, 2019/0181/0032 (CK-09-02-024); (11–13) A-1 LV, 2019/0181/0033 (19A-ck-09-2-07); (14–16) A-1 RV, 2019/0181/0034 (19B-ck-09-2-013). (1, 4, 7, 9, 11, 14) Lateral views; (2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16) internal views; (3, 16) close-up of subcentral muscle scars; (6, 13) close-up of hingement.

Holotype

SU371 (Department of Geology, Moban Lal Sukbadia University, Udaipur, India) from Quilon beds, Padappakkara, Kerala, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

While hingement is different between adult (holamphidont) and A-1 specimens (antimerodont), subcentral muscle scars are the same between adult and A-1 specimens, showing three frontal scars and a divided dorsomedian adductor scar. It suggests that subcentral muscle scars are more conservative and useful for taxonomy (e.g., defining genus) compared to hingement, which may be more affected by developmental stage, calcification degree, etc., especially in Hemicytheridae, given that we see a similar expression in Pokornyella and Tenedocythere (see below).

Genus Pokornyella Oertli, Reference Oertli1956

Type species

Cythere limbata Bosquet, Reference Bosquet1852, type horizon not designated (reported from the middle Oligocene and late Eocene in the original paper), north-central France.

Pokornyella alata Khosla, Reference Khosla1978

Figure 7

- Reference Khosla1978

Pokornyella alata Khosla, p. 264, pl. 3, figs. 7, 8.

- Reference Khosla, Nagori and Kalia1990b

Pokornyella alata; Khosla and Nagori, p. 91, pl. 2, fig.10.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Pokornyella alata; Bhandari et al., p. 132, pl. 114, figs. 1, 2.

Figure 7. Scanning electron microscope images of Pokornyella alata Khosla, Reference Khosla1978. (1–4) Adult RV, 2019/0181/0061 (19B-ck-09-2-022); (5, 6) adult RV, 2019/0181/0062 (19B-ck-09-2-023); (7) A-1 RV, 2019/0181/0063 (19B-ck-09-2-024c); (8, 9) adult LV, 2019/0181/0064 (CK-09-02-025); (10, 11) A-1 RV, 2019/0181/0065 (19B-ck-09-2-026). (1, 5, 7, 8, 10) lateral views; (2–4, 6, 9, 11) interval views; (3, 6) close-up of subcentral muscle scars; (4) close-up of hingement.

Holotype

RUGDMF no. 38 (Department of Geology, University of Rajasthan, Udaipur, India) from Gujarat, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

Pokornyella is similar to Aurila, but distinguished by two (instead of three) frontal scars and undivided dorsomedian scar, which are found both in adults and A-1 juveniles (see Pokornyella chaasraensis; Fig. 8.2, 8.14, 8.18). As discussed above for Aurila singhi, subcentral muscle scars seem to be useful for genus-level taxonomy in Hemicytheridae.

Figure 8. Scanning electron microscope images of Pokornyella chaasraensis (Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960). (1, 2) Adult LV, 2019/0181/0066 (19B-ck-09-2-027); (3) adult RV, 2019/0181/0067 (19B-ck-09-2-025); (4–6) adult LV, 2019/0181/0068 (CK-09-02-020); (7, 8) subadult? LV, 2019/0181/0069 (CK-09-02-021); (9, 10) adult RV, 2019/0181/0070 (CK-09-02-023); (11, 12) adult RV, 2019/0181/0071 (19B-CK-09-050); (13, 14) juvenile RV, 2019/0181/0072 (CK-09-02-017); (15, 16) A-1 LV, 2019/0181/0073 (19B-CK-09-047); (17, 18) A-1 RV, 2019/0181/0074 (19B-CK-09-048). (1, 3, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17) Lateral views; (2, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18) internal views; (2) close-up of subcentral muscle scars; (6) close-up of hingement.

Pokornyella chaasraensis (Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960)

Figure 8

- Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960

Trachyleberis chaasraensis Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., p. 39, pl. 3, fig. 6a, b.

- Reference Tewari and Tandon1960

Hemicythere aff. amygdala Tewari and Tandon, p. 157, text-fig. 4, fig. 2a, b

- Reference Guha1961

Aurila chaasraensis; Guha, p. 3, text-figs. 2, 4, 6.

- Reference Khosla1978

Pokornyella chaasraensis; Khosla, p. 265, pl. 3, fig. 6, pl. 6, fig. 11.

- Reference Khosla, Nagori and Kalia1990b

Pokornyella chaasraensis; Khosla and Nagori, p. 91, pl. 2, fig. 13.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Pokornyella chaasraensis; Bhandari et al., p. 134, pl. 115, figs. 1, 2.

Holotype

No. II-20 (Palaeontology Laboratory, Oil and Natural Gas Commission, Dehra Dun, India) from Kutch, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

Pokornyella chaasraensis (Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960) is similar to Pokornyella alata Khosla, Reference Khosla1978 in overall appearance, but distinguished by lacking a distinct ventrolateral ridge, especially in adult specimens.

Genus Tenedocythere Sissingh, Reference Sissingh1972

Type species

Cythereis prava Baird, Reference Baird1850a, Recent, Greece.

Tenedocythere keralaensis Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989

Figure 9

- Reference Khosla and Nagori1989

Tenedocythere keralaensis Khosla and Nagori, p. 43, pl. 9, figs. 6–10.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Tenedocythere keralaensis; Bhandari et al., p. 160, pl. 142, figs. 1–4.

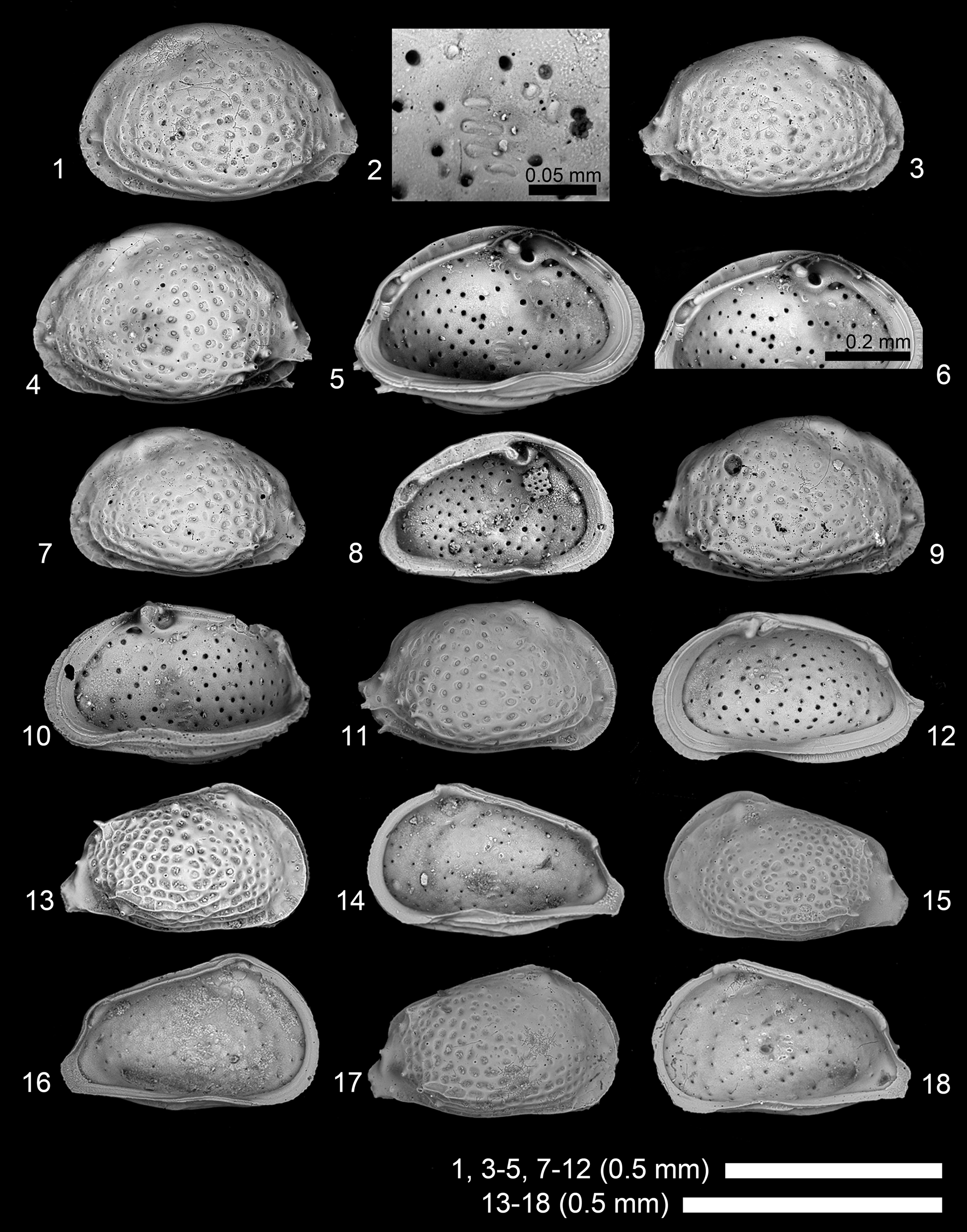

Figure 9. Scanning electron microscope images of Tenedocythere keralaensis Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989. (1, 2) Adult LV, 2019/0181/0075 (19B-ck-09-2-028); (3–5) adult LV, 2019/0181/0076 (CK-09-02-010); (6) adult RV, 2019/0181/0077 (19B-ck-09-2-029); (7, 8) adult LV, 2019/0181/0078 (CK-09-02-013); (9, 10) adult RV, 2019/0181/0079 (CK-09-02-019); (11–13) A-1 RV, 2019/0181/0080 (CK-09-02-011); (14–16) A-1 LV, 2019/0181/0081 (19B-CK-09-051); (17–19) A-1 RV, 2019/0181/0082 (19B-CK-09-053). (1, 3, 6, 7, 9, 11, 14, 17) Lateral views; (2, 4, 5, 8, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16, 18, 19) internal views; (2, 16, 19) close-up of subcentral muscle scars; (5, 13) close-up of hingement.

Holotype

No. 394 (Department of Geology, University of Rajasthan, Udaipur, India) from Quilon beds, Padappakkara, Kerala, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

Subcentral muscle scars of Tenedocythere are the same as those of Pokornyella, consisting of two frontal scars and undivided dorsomedian scar both in adult and A-1 specimens (Fig. 9.2, 9.16, 9.19), suggesting a very close relationship between Tenedocythere and Pokornyella, especially given the high overall similarity between A-1 juveniles of these genera.

Family Krithidae Mandelstam in Bubikyan, Reference Bubikyan1958

Genus Krithe Brady, Crosskey, and Robertson, Reference Brady, Crosskey and Robertson1874

Type species

Ilyobates praetexta Sars, Reference Sars1866, Recent, off the northwest coast of Norway.

Krithe autochthona Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960

Figure 10

- Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960

Krithe autochthona Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., p. 25, pl. 2, fig. 4.

- Reference Tewari and Tandon1960

Krithe indica var. kutchensis Tewari and Tandon, p. 153, text-fig. 6, fig. 2a, b.

- Reference Guha1968

Krithe autochthona; Guha, p. 213, pl. 2, fig. 2.

- Reference Khosla1978

Krithe autochthona; Khosla, p. 272, pl. 2, figs. 18–20, pl. 6, fig. 10.

- Reference Khosla and Haskins1980

Dentokrithe autochthona; Khosla and Haskins, p. 211, pl. 1, figs. 1–6.

- Reference Khosla, Nagori and Kalia1990b

Dentokrithe autochthona; Khosla and Nagori, p. 89, pl. 1, fig. 13.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Dentokrithe autochthona; Bhandari et al., p. 64, pl. 46, figs. 1, 2.

Figure 10. Scanning electron microscope images of Krithe autochthona Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960. (1–3) Adult male LV, 2019/0181/0035 (19B-ck-09-2-014); (4–6) adult male RV, 2019/0181/0036 (19B-CK-09-044); (7, 8) adult female LV, 2019/0181/0037 (CK-09-02-005); (9–11) adult male RV, 2019/0181/0038 (CK-09-02-045a); (12) adult female LV, 2019/0181/0039 (CK-09-02-004); (13) adult female LV, 2019/0181/0040 (CK-09-02-006a). (1, 4, 7, 9, 12) Lateral views; (2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11, 13) internal views; (6, 11) close-up of subcentral muscle scars; (3) close-up of hingement.

Holotype

No. II-7 (Palaeontology Laboratory, Oil and Natural Gas Commission, Dehra Dun, India) from Kutch, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

This species has recently been assigned to Dentokrithe Khosla and Haskins, Reference Khosla and Haskins1980 (Bhandari et al., Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001), which is a junior synonym of Thracella Sönmez, Reference Sönmez1963 (Guernet et al., Reference Guernet, Huyghe, Lartaud, Merle, Emmanuel, Gély, Michel and Pilet2012). Thracella (=Dentokrithe) and Krithe are almost identical, except a slight difference in hingement (adont versus pseudadont). We agree with Mazzini's (Reference Mazzini2005) opinion that this hingement difference is an intra-generic variation.

Type species

Cythere rhomboidea Fischer, Reference Fischer1855, Recent, Baltic Sea and Kattegat.

Loxoconcha confinis (Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960)

Figure 11.1–11.10

- Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960

Cytheropteron confinis Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., p. 52, pl. 4, fig. 10.

- Reference Guha1968

Cytheropteron confinis; Guha, p. 213, pl. 1, fig. 3.

- Reference Guha1974

Loxoconcha confinis; Guha, p 171.

- Reference Khosla1978

Loxoconcha confinis; Khosla, p. 275, pl. 5, fig. 11.

- Reference Khosla, Nagori and Kalia1990b

Loxoconcha (Loxoconcha) confinis; Khosla and Nagori, p. 91, pl. 3, fig. 5.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Loxoconcha (Loxoconcha) confinis; Bhandari et al., p. 82, pl. 64, figs. 1, 2.

Figure 11. Scanning electron microscope images of Loxoconcha species. (1–10) Loxoconcha confinis (Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960): (1, 2) adult male LV, 2019/0181/0041 (19B-ck-09-2-015); (3, 4) adult male RV, 2019/0181/0042 (CK-09-02-047); (5–8) adult female LV, 2019/0181/0043 (CK-09-02-048); (9, 10) adult female RV, 2019/0181/0044 (CK-09-02-046). (11–15) Loxoconcha keralaensis Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1990a: (11) adult? RV, 2019/0181/0045 (19B-ck-09-2-016); (12–15) adult RV, 2019/0181/0046 (CK-09-02-055). (1, 3, 7, 9, 11, 12) Lateral views; (2, 4–6, 8, 10, 13–15) internal views; (6, 14) close-up of subcentral muscle scars; (5, 15) close-up of hingement.

Holotype

No. II-27 (Palaeontology Laboratory, Oil and Natural Gas Commission, Dehra Dun, India) from Kutch, India. Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

External and internal views of male and female specimens are shown (Fig. 11).

Loxoconcha keralaensis Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1990a

Figure 11.11–11.15

- Reference Khosla1978

Loxoconcha sp. cf. L. alata Khosla, p. 275, pl. 5, figs. 12, 13.

- Reference Khosla and Nagori1989

Loxoconcha (Loxoconcha) subalata Khosla and Nagori, p. 46, pl. 11, figs. 1–4.

- Reference Khosla and Nagori1990a

Loxoconcha (Loxoconcha) keralaensis Khosla and Nagori, p. 314.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Loxoconcha (Loxoconcha) keralaensis; Bhandari et al., p. 84, pl. 65, figs. 1–4.

Holotype

SU407 (Department of Geology, Moban Lal Sukbadia University, Udaipur, India) from Quilon beds, Padappakkara, Kerala, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Type species

Paracytheridea depressa Müller, Reference Müller1894, Recent, Bay of Naples, Italy.

Paracytheridea perspicua Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960

Figure 12

- Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960

Paracytheridea perspicua Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., p. 50, pl. 4, fig. 8a, b.

- Reference Tewari and Tandon1960

Paracytheridea misrai Tewari and Tandon, p. 153, text-fig. 2, fig. 4a–c.

- Reference Khosla1978

Paracytheridea perspicua; Khosla, p. 275, pl. 5, fig. 6.

- Reference Khosla, Nagori and Kalia1990b

Paracytheridea perspicua; Khosla and Nagori, p. 91, pl. 3, fig. 6.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Paracytheridea perspicua; Bhandari et al., p. 126, pl. 108, figs. 1, 2.

Holotype

No. II-25 (Palaeontology Laboratory, Oil and Natural Gas Commission, Dehra Dun, India) from Kutch, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

Left valves shown here (Fig. 12.1, 12.3) are identical to the original drawing (Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960, pl. 4, fig. 8a).

Figure 12. Scanning electron microscope images of Paracytheridea perspicua Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960. (1) Adult LV, 2019/0181/0047 (19B-ck-09-2-017); (2) adult RV, 2019/0181/0048 (19B-ck-09-2-018); (3–5) adult LV, 2019/0181/0049 (19A-ck-09-2-016 = CK-09-02-027); (6, 7) adult RV, 2019/0181/0050 (CK-09-02-028). (1–3, 6) Lateral views; (4, 5, 7) internal views; (5) close-up of subcentral muscle scars.

Family Schizocytheridae Howe in Moore, Reference Moore1961

Genus Neomonoceratina Kingma, Reference Kingma1948

Type species

Neomonoceratina columbiformis Kingma, Reference Kingma1948, type horizon not designated (reported from the Pliocene and Recent in the original paper), type locality not designated (reported from north Sumatra and Java Sea in the original paper).

Neomonoceratina gajensis Guha, Reference Guha1974

Figure 13.1–13.5

- Reference Guha1974

Neomonoceratina gajensis Guha, p. 169, pl. 1, figs. 16–19, pl. 2, fig. 15.

- Reference Khosla1978

Neomonoceratina gajensis; Khosla, p. 273, pl. 5, figs. 16, 17.

- Reference Khosla, Nagori and Kalia1990b

Neomonoceratina gajensis; Khosla and Nagori, p. 91, pl. 1, fig. 9.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Neomonoceratina gajensis; Bhandari et al., p. 100, pl. 82, figs. 1, 2.

Figure 13. Scanning electron microscope images of Neomonoceratina species. (1–5) Neomonoceratina gajensis Guha, Reference Guha1974: (1) adult RV, 2019/0181/0051 (19A-ck-09-2-009); (2) adult RV, 2019/0181/0052 (19B-ck-09-2-021); (3–5) adult LV, 2019/0181/0053 (CK-09-02-029). (6–10) Neomonoceratina kutchensis Guha, Reference Guha1961: (6, 7) adult RV, 2019/0181/0054 (CK-09-02-031); (8–10) adult RV, 2019/0181/0055 (CK-09-02-057). (11–17) Neomonoceratina retispinata Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989: (11) adult LV, 2019/0181/0056 (19B-ck-09-2-019); (12) adult RV, 2019/0181/0057 (19B-ck-09-2-020); (13–15) adult RV, 2019/0181/0058 (CK-09-02-056); (16, 17) adult LV, 2019/0181/0059 (CK-09-02-030). (1–3, 6, 8, 11–13, 17) Lateral views; (4, 5, 7, 9, 10, 14–16) internal views; (5, 9) close-up of subcentral muscle scars; (10, 15) close-up of hingement.

Holotype

No. III-23 (Palaeontology Laboratory, Oil and Natural Gas Commission, Baroda, India) from Kutch, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

Our specimens have a better-developed keel and less-developed reticulation and calcification compared to the specimens shown in Khosla (Reference Khosla1978) and Bhandari et al. (Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001). The original description (Guha, Reference Guha1974) is not clear enough to compare in this regard.

Neomonoceratina kutchensis Guha, Reference Guha1961

Figure 13.6–13.10

- Reference Guha1961

Neomonoceratina kutchensis Guha, p. 3, figs. 12, 14, 18.

- Reference Guha1968

Neomonoceratina kutchensis; Guha, p. 213, pl. 2, fig. 1.

- Reference Khosla1978

Neomonoceratina kutchensis; Khosla, p. 274, pl. 5, fig. 15.

- Reference Khosla, Nagori and Kalia1990b

Neomonoceratina kutchensis; Khosla and Nagori, p. 91, pl. 1, fig. 10.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Neomonoceratina kutchensis; Bhandari et al., p. 102, pl. 83, figs. 1, 2.

Holotype

No. II-29 (Palaeontology Laboratory, Oil and Natural Gas Commission, Dehra Dun, India) from Kutch, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

Internal details are shown in Figure 13.7, 13.9, and 13.10.

Neomonoceratina retispinata Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989

Figure 13.11–13.17

- Reference Khosla and Nagori1989

Neomonoceratina retispinata Khosla and Nagori, p. 23, pl. 2, figs. 8–10.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Neomonoceratina retispinata; Bhandari et al., p. 108, pl. 89, figs. 1–4.

Holotype

No. 333 (Department of Geology, University of Rajasthan, Udaipur, India) from Quilon beds, Padappakkara, Kerala, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

Neomonoceratina retispinata Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989 is similar to Neomonoceratina kutchensis Guha, Reference Guha1961 in outline, but distinguished by having better-developed spines and primary reticulation on lateral surface.

Family Trachyleberididae Sylvester-Bradley, Reference Sylvester-Bradley1948

Genus Acanthocythereis Howe, Reference Howe1963

Type species

Acanthocythereis araneosa Howe, Reference Howe1963, middle Eocene, Louisiana, USA.

Acanthocythereis panti Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989

Figure 14.1–14.5

- Reference Khosla and Nagori1989

Acanthocythereis panti Khosla and Nagori, p. 28, pl. 4, figs. 1–4.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Acanthocythereis panti; Bhandari et al., p. 20, pl. 1, figs. 1–4.

Figure 14. Scanning electron microscope images of ostracode species. (1–5) Acanthocythereis panti Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989: (1, 2) adult female RV, 2019/0181/0083 (19B-ck-09-2-030); (3) adult male LV, 2019/0181/0084 (19B-ck-09-2-032); (4, 5) adult male RV, 2019/0181/0085 (CK-09-02-045b). (6–8) Alocopocythere fossularis (Lyubimova and Guha, 1960), adult RV, 2019/0181/0086 (19A-ck-09-2-014). (9–12) Chrysocythere jaini Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989: (9) adult male RV, 2019/0181/0087 (19B-ck-09-2-035); (10) adult female RV, 2019/0181/0088 (19B-ck-09-2-034); (11, 12) adult female RV, 2019/0181/0089 (CK-09-02-062). (1, 3, 4, 6, 9–11) lateral views; (2, 5, 7, 8, 12) internal views; (2, 8) close-up of subcentral muscle scars.

Holotype

No. 343 (Department of Geology, University of Rajasthan, Udaipur, India) from Quilon beds, Padappakkara, Kerala, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

Both female and male specimens are shown.

Genus Alocopocythere Siddiqui, Reference Siddiqui1971

Type species

Alocopocythere transcendens Siddiqui, Reference Siddiqui1971, middle Eocene, Pakistan.

Alocopocythere fossularis (Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960)

Figure 14.6–14.8

- Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960

Trachyleberis fossularis Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., p. 40, pl. 3, fig. 7.

- Reference Guha1961

Echinocythereis fossularis; Guha, p. 4, figs. 5, 9.

- Reference Khosla and Nagori1989

Alocopocythere fossularis; Khosla and Nagori, p. 33, pl. 5, fig. 6.

Holotype

No. II-17 (Palaeontology Laboratory, Oil and Natural Gas Commission, Dehra Dun, India) from Kutch, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

Only one broken valve was found in this study.

Genus Chrysocythere Ruggieri, Reference Ruggieri1962

Type species

Chrysocythere cataphracta Ruggieri, Reference Ruggieri1962, Miocene, Sicily, Italy.

Chrysocythere jaini Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989

Figure 14.9–14.12

- Reference Khosla1978

Hiltermanicythere sp. Khosla, p. 269, pl. 4, figs. 12, 13.

- Reference Khosla and Nagori1989

Chrysocythere jaini Khosla and Nagori, p. 29, pl. 4, figs. 9, 10.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Chrysocythere jaini; Bhandari et al., p. 42, pl. 24, figs. 1–4.

Holotype

No. 348 (Department of Geology, University of Rajasthan, Udaipur, India) from Quilon beds, Padappakkara, Kerala, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Type species

Cytherina edwardsii Roemer, Reference Roemer1838, “Tertiary,” Sicily, Italy. Designated by Howe (Reference Howe1955).

Costa ponticulocarinata new species

Figure 15

Figure 15. Scanning electron microscope images of Costa ponticulocarinata n. sp. (1, 2) adult LV, 2019/0181/0090 (19B-CK-09-036); (3, 4) adult RV, 2019/0181/0091 (19B-CK-09-037); (5–7) adult RV, 2019/0181/0092 (CK-09-02-061; holotype); (8) adult LV, 2019/0181/0093 (CK-09-02-042). (1, 3, 5, 8) lateral views; (2, 4, 6, 7) internal views; (7) close-up of subcentral muscle scars.

Holotype

Adult RV, 2019/0181/0092 (CK-09-02-061) (Fig. 15.5–15.7). The type locality and horizon: CK-09-02, Channa Kodi, Quilon Formation, southwestern India, early Miocene (Fig. 1).

Paratypes

2019/0181/0090 (19B-CK-09-036) (Fig. 15.1, 15.2), 2019/0181/0091 (19B-CK-09-037) (Fig. 15.3, 15.4), 2019/0181/0093 (CK-09-02-042) (Fig. 15.8).

Diagnosis

A Costa species with very well-developed ponticulate carinae and very broad inner lamella.

Occurrence

CK-09-02, Channa Kodi, Quilon Formation, southwestern India, early Miocene.

Description

Carapace moderately calcified, highest at the anterodorsal corner. Outline elongate and subrectangular; anterior margin rounded, bearing spines (visible from internal view), especially in ventral two-thirds; posterior margin bluntly acuminate and upturned, bearing long spines, especially in ventral half; dorsal margin curved at anterior one-third, bearing well-developed dorsolateral ridge (ponticulate carina); ventral margin slightly concave; ventrolateral ridge well developed as ponticulate carina, almost straight, relatively short without reaching anterior or posterior margin; median lateral ridge well developed as ponticulate carina, straight, composed of two parallel ridges in anterior half and single ridge in posterior half. Anterodorsal corner prominent; posterodorsal corner angular. Lateral surface ornamented with primary reticulation and ponticulate carinae. Hingement amphidont. Frontal muscle scar V-shaped. Adductor muscle scars consist of a vertical row of four elongate scars; ventral and ventromedian scars close to each other, dorsomedian scar curved. Anterior marginal frill well developed in internal view.

Etymology

From the Latin ponticulata + carinata (adjective in the nominative singular, feminine), with reference to very well-developed ponticulate carinae of this species.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

Species of Costa Neviani, Reference Neviani1928 usually have moderately broad inner lamella (Moore, Reference Moore1961; van Morkhoven, Reference van Morkhoven1963; Doruk, Reference Doruk1973), but this species has a very broad inner lamella. Also, hingement of this genus is reported to be holamphidont (Moore, Reference Moore1961; van Morkhoven, Reference van Morkhoven1963; Doruk, Reference Doruk1973), but some of our specimens show crenulation on anterior and posterior hinge teeth, indicating a paramphidont hinge. However, the taxonomic importance of width of inner lamella is uncertain at genus level, and the minor difference of amphidont-type hingement may be related to calcification degree rather than taxonomic difference because we see similar hingement difference between adult and A-1 in single species in Aurila and Pokornyella in this study. Otherwise, this species shows considerable similarity to the type species of Costa edwardsii (Roemer, Reference Roemer1838) (Doruk, Reference Doruk1973). Thus, we prefer to put this species in Costa.

Genus Horrificiella Liebau, Reference Liebau1975

Type species

Cythere horridula Bosquet, Reference Bosquet1854, Upper Cretaceous, type locality not designated (reported from southwestern Netherlands and west-central Belgium in the original paper).

Horrificiella? sp. 1

Figure 16

Figure 16. Scanning electron microscope images of Horrificiella? sp. 1. (1, 2) Juvenile LV, 2019/0181/0060 (CK-09-02-058). (1) Lateral view; (2) internal view.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

This species is also similar to Jugosocythereis Puri, Reference Puri1957 (type species Cythereis bicarinata Swain, Reference Swain1946). It is difficult to assure the generic assignment of this species because only one juvenile specimen occurred in our material.

Genus Paractinocythereis new genus

Type species

Actinocythereis gujaratensis Tewari and Tandon, Reference Tewari and Tandon1960, early Miocene, southwestern Kutch, India.

Diagnosis

Trachyleberidid genus characterized by three horizontal rows of spines and a lack of ocular ridge. Carapace subrectangular and/or subovate (male elongate). Anterior margin rounded, strongly denticulate with clavate spines. Posterior margin blunt and upturned, with dense spines in its ventral half. Primary reticulation weak or absent. Frontal scar V-shaped; adductor muscle scars consisting of an oblique row of four scars, with the second scar from the top elongate and largest. Hingement holamphidont with denticulate median hinge element. Internal snap-knob structure present.

Etymology

Referring to similarity and affinity of this genus to Actinocythereis.

Remarks

This genus is similar to Actinocythereis, but distinguished by lacking an ocular ridge and having a higher carapace in lateral view, resulting in subrectangular and/or suboval outline. This genus was distributed in Africa (Apostolescu, Reference Apostolescu1961; El Sogher, Reference El Sogher, Salim, MouzughI and Hammuda1996), India (Khosla and Pant, Reference Khosla and Pant1988), and USA (Huff, Reference Huff1970; Yasuhara et al., Reference Yasuhara, Hunt, Okahashi and Brandão2015) during the Paleogene; and in Arab-Africa (El-Waer, Reference El-Waer1988; Khalaf, Reference Khalaf1989; Hawramy and Khalaf, Reference Hawramy and Khalaf2013; Ied and Ismail, Reference Ied and Ismail2016), India (Bhandari et al., Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001), IAA (Shin et al., Reference Shin, Yasuhara, Iwatani, Kase, Fernando, Hayashi, Kurihara and Pandita2019), and South China Sea (Gou et al., Reference Gou, Chen, Guan, Jian, Liu, Lai, Wu, Chen and Hou1981) during the Neogene. Given their absence in Cenozoic Europe (Western Tethys) (e.g., Ducasse et al., Reference Ducasse, Guernet, Tambareau and Oertli1985; Guernet, Reference Guernet2005; Lord et al., Reference Lord, Whittaker, King, Whittaker and Hart2009; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Wilkinson, Maybury, Whatley, Whittaker and Hart2009; Guernet et al., Reference Guernet, Huyghe, Lartaud, Merle, Emmanuel, Gély, Michel and Pilet2012) and Paleogene Pacific (e.g., Yamaguchi, Reference Yamaguchi2006; Yamaguchi and Kamiya, Reference Yamaguchi and Kamiya2007a, Reference Yamaguchi and Kamiyab, Reference Yamaguchi and Kamiya2009) fossil records, the relationship between American and Eastern Tethys Paleogene Paractinocythereis n gen. remains uncertain, but we speculate on a possible dispersal from the Eastern Tethys through the African coast to the Atlantic coast of the USA (or the opposite direction). Actinocythereis probably evolved from and took over Paractinocythereis in the USA in the Miocene.

Species included: Paractinocythereis purii (Huff, Reference Huff1970) n. comb., P. texana (Stadnichenko, Reference Stadnichenko1927) n. comb., P. scutigera (Brady, Reference Brady, De Folin and Perier1868) n. comb., P. sinensis (Gou in Gou et al., Reference Gou, Chen, Guan, Jian, Liu, Lai, Wu, Chen and Hou1981) n. comb., P. iraqensis (Khalaf, Reference Khalaf1981) n. comb., P. costata (Khalaf, Reference Khalaf1989) n. comb., P. cornuocula (Khalaf, Reference Khalaf1989) n. comb., P. dextraspina (Khalaf, Reference Khalaf1989) n. comb., P. spinosa (Khalaf, Reference Khalaf1989) n. comb., P. modesta (Apostolescu, Reference Apostolescu1961) n. comb., P. spinosa (El-Waer, Reference El-Waer1988) n. comb., which is a junior homonym of P. spinosa (Khalaf, Reference Khalaf1989), P. khariensis (Khosla and Pant, Reference Khosla and Pant1988) n. comb., P. gujaratensis (Tewari and Tandon, Reference Tewari and Tandon1960) n. comb., P. tumefacentis (Lubimova and Guha in Lubimova et al., Reference Lubimova, Guha and Mohan1960) n. comb., P. vinjhanensis (Tewari and Tandon, Reference Tewari and Tandon1960) n. comb. (male of Actinocythereis gujaratensis, in our opinion).

Paractinocythereis gujaratensis (Tewari and Tandon, Reference Tewari and Tandon1960) new combination

Figure 17

- Reference Tewari and Tandon1960

Actinocythereis gujaratensis Tewari and Tandon, p. 154, text-fig. 3, fig. la, b.

- Reference Tewari and Tandon1960

Trachyleberis vinjhanensis Tewari and Tandon, p. 155, text-fig. 3, fig. 4a, b.

- Reference Khosla1978

“Archicythereis” sp. A Khosla, p. 267, pl. 4, fig. 8, pl. 6, fig. 12.

- Reference Khosla and Nagori1989

“Archicythereis” vermai Khosla and Nagori, p. 24, pl. 3, figs. 1–3.

- Reference Khosla, Nagori and Kalia1990b

Actinocythereis gujaratensis; Khosla and Nagori, p. 89, pl. 2, fig. 2.

- Reference Khosla, Nagori and Kalia1990b

Trachyleberis vinjhanensis; Khosla and Nagori, p. 89, pl. 2, fig. 3.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Actinocythereis gujaratensis; Bhandari et al., p. 20, pl. 2, figs. 1–4.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

“Archicythereis” vermai; Bhandari et al., p. 30, pl. 12, figs. 1–4.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Actinocythereis vinjhanensis; Bhandari et al., p. 22, pl. 4, figs. 1, 2.

Figure 17. Scanning electron microscope images of Paractinocythereis gujaratensis (Tewari and Tandon, Reference Tewari and Tandon1960). (1, 2) A-1 RV, 2019/0181/0094 (19B-ck-09-2-033); (3, 4) adult female? LV, 2019/0181/0095 (CK-09-02-043); (5, 6) A-1 RV, 2019/0181/0096 (CK-09-02-044); (7, 8) A-1 LV, 2019/0181/0097 (CK-09-02-053); (9) adult male? LV, 2019/0181/0098 (19B-ck-09-2-031); (10–12) adult male? RV, 2019/0181/0099 (CK-09-02-051). (1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 10) lateral views; (2, 4, 6, 8, 11, 12) internal views; (2, 12) close-up of subcentral muscle scars.

Holotype

No. 138 (probably Geology Department, Lucknow University, Lucknow, India) from Kutch, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

“Archicythereis” vermai Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989 is a juvenile of Actinocythereis gujaratensis Tewari and Tandon, Reference Tewari and Tandon1960 n. comb., in our opinion. In addition, Actinocythereis vinjhanensis (Tewari and Tandon, Reference Tewari and Tandon1960) n. comb. is probably male of and, thus, conspecific with (and thus junior synonym of) Actinocythereis gujaratensis Tewari and Tandon, Reference Tewari and Tandon1960 n. comb. (considering alphabetical order of species name), in our opinion.

Genus Puricythereis Bonaduce, Masoli, and Pugliese, Reference Bonaduce, Masoli and Pugliese1976

Type species

Puricythereis papilio Bonaduce, Masoli, and Pugliese, Reference Bonaduce, Masoli and Pugliese1976, Recent, Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea.

Remarks

Quadraleberis Bate and Sheppard, Reference Bate and Sheppard1980 and Crenaleya Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Neale and Siddiqui1991 are junior synonyms of Puricythereis. Spongicythere Howe, Reference Howe1951 (type species Spongicythere spissa Howe, Reference Howe1951) is very similar to Puricythereis in outline and reticulation (Howe, Reference Howe1951) and may be the senior synonym. However, the original 1950s micrographic images do not allow detailed comparisons (Howe, Reference Howe1951) and the type or topotype specimens of Spongicythere spissa need to be restudied to determine if Puricythereis is a junior synonym of Spongicythere.

Puricythereis reticulata (Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989)

Figure 18.1–18.5

- Reference Khosla and Nagori1989

Lankacythere reticulata Khosla and Nagori, p. 35, pl. 6, figs. 8–10.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Lankacythere reticulata; Bhandari et al., p. 82, pl. 63, figs. 1–4.

Figure 18. Scanning electron microscope images of ostracode species. (1–5) Puricythereis reticulata (Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989): (1) adult female? LV, 2019/0181/0100 (19A-ck-09-2-010); (2–5) adult male? LV, 2019/0181/0101 (CK-09-02-033). (6–16) Ruggieria guhai Khosla, Reference Khosla1978: (6) A-1 LV, 2019/0181/0102 (19A-ck-09-2-012); (7–9) adult RV, 2019/0181/0103 (CK-09-02-039); (10–12) A-1 LV, 2019/0181/0104 (CK-09-02-041); (13, 14) adult RV, 2019/0181/0105 (CK-09-02-038); (15, 16) adult LV, 2019/0181/0106 (CK-09-02-040). (1, 2, 6, 7, 10, 13, 15) lateral views; (3–5, 8, 9, 11, 12, 14, 16) internal views; (4, 8) close-up of subcentral muscle scars; (5, 12) close-up of hingement.

Holotype

No. 365 (Department of Geology, University of Rajasthan, Udaipur, India) from Quilon beds, Padappakkara, Kerala, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

This species is better placed in Puricythereis rather than Lankacythere Bhatia and Kumar, Reference Bhatia, Kumar and Krstic1979, in our opinion. The type species of Lankacythere, Cythere coralloides Brady, Reference Brady1886 (Mostafawi, Reference Mostafawi1992; Jellinek, Reference Jellinek1993), is clearly distinct from Puricythereis, and this species is very similar to the type species of Puricythereis (Bonaduce et al., Reference Bonaduce, Masoli and Pugliese1976) in having irregular-shaped fossae with ingrowing spines and posteroventral margin bearing spines.

Genus Ruggieria Keij, Reference Keij1957

Type species

Cythere micheliniana Bosquet, Reference Bosquet1852, Miocene, southwestern France.

Ruggieria guhai Khosla, Reference Khosla1978

Figure 18.6–18.16

- Reference Guha1961

Ruggieria aff. micheliniana (Bosquet); Guha, p. 4, fig. 15.

- Reference Khosla1978

Ruggieria guhai Khosla, p. 270, pl. 4, figs. 18, 19, pl. 6, fig. 19.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Ruggieria guhai; Bhandari et al., p. 144, pl. 126, figs. 1, 2.

Holotype

RUGDMF no. 64 (Department of Geology, University of Rajasthan, Udaipur, India) from Gujarat, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

Lateral and internal views of adult and juvenile specimens are shown.

Genus Stigmatocythere Siddiqui, Reference Siddiqui1971

Type species

Stigmatocythere obliqua Siddiqui, Reference Siddiqui1971, early Eocene, Pakistan.

Stigmatocythere cf. S. arcuata Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla, Nagori, Hanai, Ikeya and Ishizaki1988

Figure 19.11–19.13

Figure 19. Scanning electron microscope images of Stigmatocythere species. (1–6) Stigmatocythere interrupta Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla, Nagori, Hanai, Ikeya and Ishizaki1988: (1, 2) adult carapace, 2019/0181/0107 (19B-ck-09-2-038); (3, 4) adult RV, 2019/0181/0108 (ck-09-02-059); (5) adult LV, 2019/0181/0109 (19B-ck-09-2-040a); (6) adult RV, 2019/0181/0110 (CK-09-02-060). (7–10) Stigmatocythere chaasraensis (Guha, Reference Guha1961), adult LV, 2019/0181/0111 (CK-09-02-006b). (11–13) Stigmatocythere cf. S. arcuata: (11) adult LV, 2019/0181/0112 (19B-ck-09-2-039); (12) adult RV, 2019/0181/0113 (19B-ck-09-2-041); (13) adult carapace, 2019/0181/0114 (CK-09-02-009). (1) right lateral view of carapace; (2, 13) left lateral views of carapaces; (3, 5–7, 11, 12) lateral views; (4, 8–10) internal views; (9) close-up of subcentral muscle scars; (10) close-up of hingement.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

This species is very similar to Stigmatocythere arcuata Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla, Nagori, Hanai, Ikeya and Ishizaki1988, but has stronger primary reticulation and irregular-shaped fossae.

Stigmatocythere chaasraensis (Guha, Reference Guha1961)

Figure 19.7–19.10

- Reference Guha1961

Occultocythereis chaasraensis Guha, p.4, figs. 8, 10, 13.

- Reference Khosla1976

Stigmatocythere chaasraensis; Khosla, p. 136, pl. 1, figs. 7–9.

- Reference Khosla1978

Stigmatocythere chaasraensis; Khosla, p. 271, pl. 5, fig. 2, pl. 6, fig. 16.

- Reference Khosla, Nagori, Hanai, Ikeya and Ishizaki1988

Stigmatocythere (Stigmatocythere) chaasraensis; Khosla and Nagori, p.110, pl. 1, fig. 1.

- Reference Khosla, Nagori and Kalia1990b

Stigmatocythere (Stigmatocythere) chaasraensis; Khosla and Nagori, p. 91, pl. 3, fig. 1.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Stigmatocythere (Stigmatocythere) chaasraensis; Bhandari et al., p. 154, pl. 135, figs. 1, 2.

- Reference Bhandari2004

Stigmatocythere (Stigmatocythere) chaasraensis; Bhandari, p. 187, fig. 8.2.

Holotype

No. II-30 (Palaeontology Laboratory, Oil and Natural Gas Commission, Dehra Dun, India) from Kutch, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

Only one left valve was found in this study.

Stigmatocythere interrupta Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla, Nagori, Hanai, Ikeya and Ishizaki1988

Figure 19.1–19.6

- Reference Khosla, Nagori, Hanai, Ikeya and Ishizaki1988

Stigmatocythere (Bhatiacythere) interrupta Khosla and Nagori, p. 115, pl. 2, figs. 1–4.

- Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001

Stigmatocythere (Bhatiacythere) interrupta; Bhandari et al., p. 150, pl. 131, figs. 1–4.

- Reference Bhandari2004

Stigmatocythere (Bhatiacythere) interrupta; Bhandari, p. 193, fig. 9.4.

Holotype

RUGDMF no. 284 (Department of Geology, University of Rajasthan, Udaipur, India) from Quilon beds, Kerala, India. Early Miocene.

Dimensions

See Table 1.

Remarks

Stigmatocythere interrupta Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla, Nagori, Hanai, Ikeya and Ishizaki1988 is similar to Stigmatocythere rete Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla, Nagori, Hanai, Ikeya and Ishizaki1988, but distinguished by the lack of primary reticulation. Stigmatocythere arcuata Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla, Nagori, Hanai, Ikeya and Ishizaki1988 has finer ridges and slightly different ridge arrangement compared to Stigmatocythere interrupta.

Discussion

Paleoenvironmental interpretation

Abundant genera in the sample CK-09-02 include Pokornyella, Loxoconcha, Tenedocythere, and Aurila. All of these genera are known to be indicative of shallow (upper shelf or neritic), fully marine, and warm water environments (Bonaduce et al., Reference Bonaduce, Ruggieri and Russo1984; Whatley and Jones, Reference Whatley and Jones1999; Zorn, Reference Zorn2003; Whatley et al., Reference Whatley, Jones and Roberts2004; Szczechura, Reference Szczechura2006; Titterton and Whatley, Reference Titterton and Whatley2008; Hajek-Tadesse and Prtoljan, Reference Hajek-Tadesse and Prtoljan2011; Seko et al., Reference Seko, Pipík and Doláková2012). Krithe is the only typical deep-sea genus from this sample (Zhou and Ikeya, Reference Zhou and Ikeya1992; Coles et al., Reference Coles, Whatley and Moguilevsky1994; Zhao and Whatley, Reference Zhao and Whatley1997; Rodriguez-Lazaro and Cronin, Reference Rodriguez-Lazaro and Cronin1999; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Yasuhara, Iwatani, Alvarez Zarikian, Bassetti and Sagawa2018). Although shallow-marine Krithe occurrences and species are known (Ishizaki, Reference Ishizaki1971; Whatley and Zhao, Reference Whatley and Zhao1993; Zhao and Whatley, Reference Zhao and Whatley1997), Krithe is indicative of comparatively deeper waters, even in shallow marine environments, and suggests deeper waters than those suggested from the abundant genera mentioned above (Yasuhara et al., Reference Yasuhara, Irizuki, Yoshikawa and Nanayama2002a, Reference Yasuhara, Yoshikawa and Nanayama2005; Yasuhara and Seto, Reference Yasuhara and Seto2006). No other typical deep-water genera, such as Cytheropteron and Argilloecia, occurred in this sample, even though these genera are known to be abundant in upper bathyal depths in the Indo-Pacific region (Iwatani et al., Reference Iwatani, Yasuhara, Rosenthal and Linsley2018). In addition to the above-mentioned abundant genera, many other warm (often tropical) water indicator genera occurred in this sample (e.g., Cytherelloidea, Neomonoceratina, Paijenborchellina, Ruggieria, Phlyctenophora, and Stigmatocythere) (Wood and Whatley, Reference Wood and Whatley1994; Yasuhara et al., Reference Yasuhara, Hong, Tian, Chong, Okahashi, Littler and Cotton2018; Hong et al., Reference Hong, Yasuhara, Iwatani and Mamo2019; Shin et al., Reference Shin, Yasuhara, Iwatani, Kase, Fernando, Hayashi, Kurihara and Pandita2019). Loxoconcha and Aurila are typical phytal genera, although they include sediment-dwelling species (Kamiya, Reference Kamiya, Hanai, Ikeya and Ishizaki1988; Yasuhara et al., Reference Yasuhara, Irizuki, Yoshikawa and Nanayama2002b, Reference Yasuhara, Yoshikawa and Nanayama2005; Szczechura, Reference Szczechura2006; Yasuhara and Seto, Reference Yasuhara and Seto2006; Reich et al., Reference Reich, Di Martino, Todd, Wesselingh and Renema2015). In sum, the depositional environment interpreted based on ostracodes for the sample CK-09-02 is shallow (upper–middle shelf or neritic), full marine, and warm water environment, with some phytal environment nearby. This is generally consistent with the paleoenvironment interpreted based on other fossil groups (see the geological setting section above).

Paleobiogeographic remarks

Compared to relatively well-investigated Paleogene global shallow-marine ostracode paleobiogeography (Yamaguchi, Reference Yamaguchi2006; Yamaguchi and Kamiya, Reference Yamaguchi and Kamiya2009; Yasuhara et al., Reference Yasuhara, Hong, Tian, Chong, Okahashi, Littler and Cotton2018), Miocene shallow-marine Indian ostracodes have seldom been discussed in a global paleobiogeography context (Szczechura, Reference Szczechura1980; Siddiqui, Reference Siddiqui and Maddocks1983).

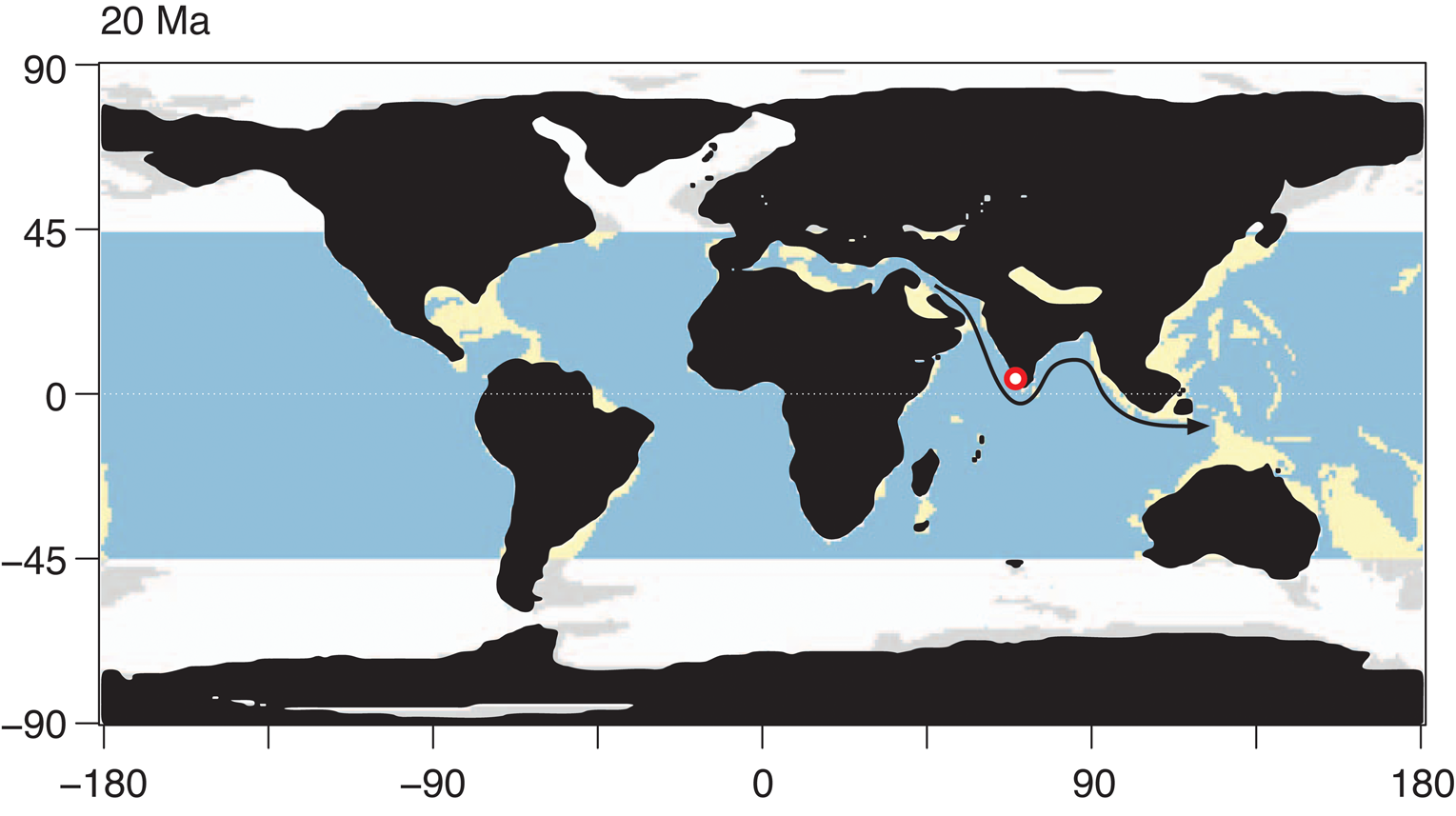

Many genera that we found here and reported from Miocene India (Khosla, Reference Khosla1978; Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989; Bhandari et al., Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001) are well known and widely distributed in the Tethyan region (see Fig. 20 for early Miocene paleogeographic map). Phlyctenophora is widely known from Tethyan Paleogene (see Yasuhara et al., Reference Yasuhara, Hong, Tian, Chong, Okahashi, Littler and Cotton2018) and Paratethyan Miocene (Aiello and Szczechura, Reference Aiello and Szczechura2004; Gross and Piller, Reference Gross and Piller2006). Flexus is widely known from the Oligocene–Miocene of Europe (Moore, Reference Moore1961; Weiss, Reference Weiss1983; Ducasse and Cahuzac, Reference Ducasse and Cahuzac1997 Gross and Piller, Reference Gross and Piller2006; Szczechura, Reference Szczechura2006; Faranda et al., Reference Faranda, Cipollari, Cosentino, Gliozzi and Pipponzi2008; Hajek-Tadesse and Prtoljan, Reference Hajek-Tadesse and Prtoljan2011; Seko et al., Reference Seko, Pipík and Doláková2012) and from the Eocene–Miocene of Arabia (Al-Furaih, Reference Al-Furaih1980; Aziz and Al-Shumam, Reference Aziz and Al-Shumam2013). Paijenborchellina is also a Tethyan genus, known from the Cretaceous to Recent circum-Mediterranean region, including Africa, Russia, Arabia, and West Asia (Szczechura, Reference Szczechura1980; Brouwers and Fatmi, Reference Brouwers and Fatmi1992a, Reference Brouwers and Fatmib [as Paijenborchella]; Bassiouni and Luger, Reference Bassiouni and Luger1996; Bhandari, Reference Bhandari1996; Hawramy and Khalaf, Reference Hawramy and Khalaf2013; Yasuhara et al., Reference Yasuhara, Hong, Tian, Chong, Okahashi, Littler and Cotton2018). Costa is also a typical Tethyan genus (Yamaguchi and Kamiya, Reference Yamaguchi and Kamiya2009). Hemicyprideis is basically an European genus known from the Oligocene to the Miocene (Malz and Triebel, Reference Malz and Triebel1970; Ducasse et al., Reference Ducasse, Guernet, Tambareau and Oertli1985; Monostori, Reference Monostori2004; Tóth, Reference Tóth2008), and known from the Arabian Miocene (Hawramy and Khalaf, Reference Hawramy and Khalaf2013). Neocyprideis (sensu Yasuhara et al., Reference Yasuhara, Hong, Tian, Chong, Okahashi, Littler and Cotton2018) was widely distributed in the Tethyan Region during the Paleogene including Europe, Arabia, Africa, and West Asia (Keen and Racey, Reference Keen and Racey1991; Siddiqui, Reference Siddiqui2000; Yasuhara et al., Reference Yasuhara, Hong, Tian, Chong, Okahashi, Littler and Cotton2018). The center of distribution of these Tethyan genera has shifted eastward to the Indo-Pacific region in the Neogene, and they have been widely reported from the Miocene Indian and IAA regions (Khosla, Reference Khosla, Hanai, Ikeya and Ishizaki1988; Bhandari et al., Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001; Yasuhara et al., Reference Yasuhara, Hong, Tian, Chong, Okahashi, Littler and Cotton2018; Shin et al., Reference Shin, Yasuhara, Iwatani, Kase, Fernando, Hayashi, Kurihara and Pandita2019). Krithe with pseudadont hinge has been reported as Thracella and Dentokrithe from the European Eocene (Lord et al., Reference Lord, Whittaker, King, Whittaker and Hart2009; Guernet et al., Reference Guernet, Huyghe, Lartaud, Merle, Emmanuel, Gély, Michel and Pilet2012) and the Indian Eocene and Miocene (Bhandari, Reference Bhandari1996; Bhandari et al., Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001), respectively. Aurila and Loxoconcha are globally distributed Cenozoic genera (van Morkhoven, Reference van Morkhoven1963; Athersuch and Horne, Reference Athersuch and Horne1984), but they are diverse in the European Miocene and thereafter (Ruggieri, Reference Ruggieri1975; Athersuch and Horne, Reference Athersuch and Horne1984; Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Maybury and Whatley2000; Guernet, Reference Guernet2005; Gross and Piller, Reference Gross and Piller2006; Zorn, Reference Zorn2010). In addition, there is a similar species to Loxoconcha confinis known in Europe—Loxoconcha punctatella (Reuss, Reference Reuss1850) (see Gross and Piller, Reference Gross and Piller2006). Paracytheridea is globally known, but Paracytheridea perspicua is very similar to the Tanzanian Eocene species Paracytheridea anapetes Ahmad Reference Ahmad1977 (Ahmad, Reference Ahmad1977; Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Neale and Siddiqui1991). Although Neomonoceratina is most diverse in the tropical Indo-West Pacific (Zhao and Whatley, Reference Zhao and Whatley1988), oldest records of the genus are known from the Eastern Tethys of Indo-Pakistan and Arab-Africa (Bassiouni and Luger, Reference Bassiouni and Luger1996; Bhandari, Reference Bhandari1996; Siddiqui, Reference Siddiqui2006; Yasuhara et al., Reference Yasuhara, Hong, Tian, Chong, Okahashi, Littler and Cotton2018). Pokornyella is obviously a Tethyan genus, well known from the Paleogene and Miocene of Europe (Ducasse and Coustillas, Reference Ducasse and Coustillas1981; Ducasse et al., Reference Ducasse, Guernet, Tambareau and Oertli1985; Gross and Piller, Reference Gross and Piller2006; Zorn, Reference Zorn2010; Guernet et al., Reference Guernet, Huyghe, Lartaud, Merle, Emmanuel, Gély, Michel and Pilet2012), as well as its adjacent regions (Holden, Reference Holden1976; Yasuhara et al., Reference Yasuhara, Hong, Tian, Chong, Okahashi, Littler and Cotton2018). Pokornyella chaasraensis is very similar to a European species Pokornyella deformis (Reuss, Reference Reuss1850) (Gross and Piller, Reference Gross and Piller2006; Zorn, Reference Zorn2010). Ruggieria is a Miocene–Recent European genus (Moore, Reference Moore1961) that is also known from the early Miocene of Africa (Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Neale and Siddiqui1991) and India (Bhandari et al., Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001) and Recent Indo-Pacific (Whatley and Zhao, Reference Whatley and Zhao1988; Dewi, Reference Dewi1997). The trachyleberidid genera Chrysocythere and Costa are globally distributed, but are also typical European genera (Ruggieri, Reference Ruggieri1961; Guernet, Reference Guernet2005; Bossio et al., Reference Bossio, Dall'Antonia, Da Prato, Foresi and Oggiano2006). Puricythereis is known from the Oligocene–Miocene of Africa as Crenaleya (Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Neale and Siddiqui1991), the Eocene of Europe as Leguminocythereis heistensis (Keij, Reference Keij1957) in Ducasse et al. (Reference Ducasse, Guernet, Tambareau and Oertli1985, pl. 81, fig. 9, not others; we do not think this specimen is conspecific with Leguminocythereis heistensis), the Miocene of India as Quadraleberis and Lankacythere (Khosla and Nagori, Reference Khosla and Nagori1989), and the Recent Red Sea, Persian Gulf, and East African coast as Puricythereis and Quadraleberis (Bate and Sheppard, Reference Bate and Sheppard1980; Jellinek, Reference Jellinek1993; Mostafawi, Reference Mostafawi2003). Stigmatocythere is known from the Eocene–Miocene of Indo-Pakistan (Siddiqui, Reference Siddiqui1971, Reference Siddiqui and Maddocks1983; Bhandari, Reference Bhandari2004), Paleocene–Miocene Arab-Africa (Reyment, Reference Reyment1963; Okosun, Reference Okosun1987; Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Neale and Siddiqui1991; Guernet et al., Reference Guernet, Bourdillon De Grissac and Roger1991; Keen and Racey, Reference Keen and Racey1991; Bassiouni and Luger, Reference Bassiouni and Luger1996; Hawramy and Khalaf, Reference Hawramy and Khalaf2013), and Recent Indo-Pacific (Whatley and Zhao, Reference Whatley and Zhao1988; Dewi, Reference Dewi1997). In summary, our early Miocene Indian ostracode fauna shows strong affinity both to Eocene–Miocene Eastern and Western Tethyan ostracode faunas and to Miocene–Recent Indo-Pacific ostracode faunas, supporting the Hopping Hotspot Hypothesis that the Tethyan biodiversity hotspot has shifted eastward through Arabia to IAA, together with concomitant biogeographic shifts of the Tethyan elements (Renema et al., Reference Renema, Bellwood, Braga, Bromfield, Hall, Johnson, Lunt, Meyer, McMonagle, Morley, O'Dea, Todd, Wesselingh, Wilson and Pandolfi2008) (Fig. 20).

Figure 20. Early Miocene paleogeographic map (20 Ma), from Leprieur et al. (Reference Leprieur, Descombes, Gaboriau, Cowman, Parravicini, Kulbicki, Melián, de Santana, Heine, Mouillot, Bellwood and Pellissier2016). Red circle indicates the studied site CK-09-02. Light blue, deep tropical ocean; yellow, tropical shallow reefs; white and light gray, deep ocean and shallow waters outside the tropical boundary, respectively. Arrow indicates hypothetical route of biogeographic shift of Tethyan elements from Tethys to IAA.

Tenedocythere is well known from the middle–late Miocene of Europe (Bonaduce et al., Reference Bonaduce, Ruggieri and Russo1984; Gross and Piller, Reference Gross and Piller2006; Szczechura, Reference Szczechura2006; Hajek-Tadesse and Prtoljan, Reference Hajek-Tadesse and Prtoljan2011), but older (Eocene–early Miocene) records are known only from the Central Pacific (Holden, Reference Holden1976) and the Eastern Tethys of Africa and India (Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Neale and Siddiqui1991; Bhandari et al., Reference Bhandari, Khosla and Nagori2001). Quadracythere subquadra Siddiqui, Reference Siddiqui1971 sensu Ahmad et al. (Reference Ahmad, Neale and Siddiqui1991) (note that, in our opinion, Ahmad's specimens are not conspecific or congeneric to Quadracythere subquadra) and Quadracythere vanga Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Neale and Siddiqui1991 are Tenedocythere, in our opinion, and are from Oligocene of Africa, the oldest records of the genus (Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Neale and Siddiqui1991). Especially Tenedocythere keralaensis is very similar to Tenedocythere subquadra (Siddiqui, Reference Siddiqui1971) sensu Ahmad et al. (Reference Ahmad, Neale and Siddiqui1991). Thus, inverse westward shift had also existed.