Introduction

The extinct hamster genus Neocricetodon is one of the most successful and long-existed taxa of the Eurasian cricetids, spanning for more than six million years. The genus presumably originated in the early late Miocene, diversified and dispersed in both Europe and Asia throughout the late Miocene, and went extinct in the late Pliocene (Daxner-Höck et al., 1998; Kälin, Reference Kälin1999; Fejfar et al., Reference Fejfar, Heinrich, Kordos and Maul2011). Comprising approximately 20 species, it is believed to be an evolutionary link between primitive and modern cricetins (Fahlbusch, Reference Fahlbusch1969; Reig, Reference Reig1977; Zheng, Reference Zheng1984a). The earliest finds that have been assigned to this genus come from the early late Miocene of Central Europe. These are Kowalskia cf. schaubi (Kretzoi, Reference Kretzoi1951) from Rudabánya, Hungary (Kordos, Reference Kordos1987; Kretzoi and Fejfar, Reference Kretzoi and Fejfar2004), Kowalskia cf. fahlbuschi (Bachmayer and Wilson, Reference Bachmayer and Wilson1970) from Suchomasty, the Czech Republic (Fejfar, Reference Fejfar1990), and an indeterminate species from Vösendorf, Austria (Daxner-Höck, Reference Daxner-Höck1972). The fragmentary and sparse nature of these fossils complicates their taxonomical interpretation, and the origin and evolution of the genus remain poorly understood. At the same time, Neocricetodon is a biostratigraphically important taxon that is used for ordering the late Neogene mammal biochronology of Eurasia since the adoption of European and Asian land mammal ages (Mein, Reference Mein1990; Sűmengen et al., Reference Sűmengen, Űnay, Saraç, de Bruijn, Terlemez and Gűrbűz1990; Qui et al., Reference Qiu, Wang and Li2013).

There is another and even less known early species of Neocricetodon, N. moldavicus, that has been described by Lungu (Reference Lungu1981) on the basis of dental and few craniomandibular specimens from the early late Miocne of Moldova. Despite its being one of the earliest member of the genus, this species has received little attention. The original description includes a vast diagnosis, a rather brief comparison with several similar species known at that time, and five figures. It does not mention, however, the most taxonomically informative characters currently in use. This resulted in the lack of consensus about the position of N. moldavicus. It has been interpreted as either the most primitive species of the genus (Lungu, Reference Lungu1981; Wu, Reference Wu1991), or an aberrant cricetid with possible Cricetulodon Hartenberger, 1965 affinities (Topachevsky and Skorik, Reference Topachevsky and Skorik1992; Topachevsky et al., Reference Topachevsky, Nesin and Topachevsky1997). The present paper revises the type material of N. moldavicus to provide a more detailed description of this taxon and advance our knowledge of the Neocricetodon origin and evolution.

Geologic setting

The material of N. moldavicus came from two late Miocene localities Calfa and Bujor 1, Republic of Moldova (Fig. 1). Lungu (Reference Lungu1978, Reference Lungu1981), Lungu and Rzebik-Kowalska (Reference Lungu and Rzebik-Kowalska2011) have presented the detailed overview on the Calfa and Bujor 1 geology, taphonomy, and chronology. Calfa (Kalfa) is situated in the eastern part of Anenii Noi District, approximately 700 m northwest of Calfa Village (46°55'05.77''N, 29°21'43.34''E). The late Miocene section of Calfa exposes limestone intercalated with clay rich in shells of Bessarabian (corresponding to early Tortonian) mollusks (Mactra podolica, Plicatiforma fittoni, Solen subfragilis) and vertebrate fossils. The locality Bujor 1 (Bujoru, Bujory, Būzhor-I, Buzhory, Bužory) is an abandoned sandpit southeast of Bujor Village, Khynchesht District (46°54'44.11''N, 28°16'48.38''E). The section is built of sand and clayey sand intercalated with fossil-bearing gravels. Higher in the section, there is a layer of Bessarabian limestone with shells of Mactra fabreana, M. podolica, Plicatiforma fittoni, and Solen subfragilis. The exact age of Calfa and Bujor 1 faunas is debatable. Except for the remains of Proochotona kalfense Lungu, Reference Lungu1981, very few small mammal fossils collected from Calfa provide information on its biochronological age. In contrast, Bujor 1 yielded a diverse small mammal assemblage including several biostratigraphically important taxa. Both Calfa and Bujor 1 have originally been referred to the Vallesian European Land Mammal Age (roughly corresponding to early Tortonian) by Lungu (Reference Lungu1981) and later to the late Vallesian by Topachevsky et al. (Reference Topachevsky, Nesin and Topachevsky1997) and Nesin (Reference Nesin2004) based on the mammals listed by Lungu (Reference Lungu1981). Vangengeim et al. (Reference Vangengeim, Lungu and Tesakov2006) provided magnetostratigraphy-based ages for the fossil-bearing sediments of Calfa and Bujor 1 as ranging from the upper part of Chron C5An to Subchron C5r2n (11.9–11.5 Ma) and so corresponding, in their view, to the early Vallesian. This age has been followed by most subsequent authors (Casanovas-Villar, Reference Casanovas-Vilar2007; Rzebik-Kowalska and Lungu, Reference Rzebik-Kowalska and Lungu2009; Lungu and Rzebik-Kowalska, Reference Lungu and Rzebik-Kowalska2011; Delinschi, Reference Delinschi2013, Reference Delinschi2014). It has recently been questioned, however, by Vasiliev et al. (Reference Vasiliev, Iosifidi, Khramov, Krijgsman, Kuiper, Langereis, Popov, Stoica, Tomsha and Yudin2011), who provided a radioisotopic age suggesting that the Khersonian (an equivalent of middle Tortonian) most likely correlates to the younger Chron C4An and later part of Chron C4Ar, and therefore, the Bessarabian–Khersonian boundary is probably drawn within Chron C4Ar. This means that the Vallesian localities in Moldova are significantly younger than 11.2 Ma. Given that this new evidence is in good agreement with biochronological markers (the presence of at least two murid genera and Spermophilinus turolensis de Bruijn and Mein, 1968, and the absence of Democricetodon, Megacricetodon Fahlbusch, Reference Fahlbusch1964, and Microtocricetus Fahlbusch and Mayr, 1975), we consider the late Vallesian age of Calfa and Bujor 1 as most probable.

Figure 1 Location map of Bujor 1 (Buj1) and Calfa (Caf) localities.

Materials and methods

The fossils of N. moldavicus from the localities Calfa (TSU Caf), Bujor 1 (TSU Buj1) are stored in the Department of Geography, Tiraspol State University (Kishinev, Moldova). All drawings and measurements (in millimeters with 0.01 mm precision) were made using a binocular microscope with a camera lucida and ocular micrometer. To facilitate comparisons, all specimens are figured as left ones. We use uppercase letters for upper teeth and lowercase letters for lower teeth, with exception of incisors, abbreviated as Isup and Iinf. Dental terminology follows Freudenthal et al. (Reference Freudenthal, Hugueney and Moissenet1994); measurements follow Freudenthal (Reference Freudenthal1966). The age of the eastern Paratethys biochronological stages and their correlation with the European Land Mammal Ages were taken from Topachevsky et al. (Reference Topachevsky, Nesin and Topachevsky1997) and Nesin and Nadachowski (Reference Nesin and Nadachowski2001).

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

NMNHU-P, Department of Paleontology, National Museum of Natural History, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Kiev, Ukraine; NMW, Department of Geology and Paleontology, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Austria; TSU, Department of Geography, Tiraspol State University, Kishinev, Moldova; UUN, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Systematic paleontology

Order Rodentia Bowdich, Reference Bowdich1821

Family Cricetidae Fischer, Reference Fischer1817

Subfamily Cricetinae Fischer, Reference Fischer1817

Remarks

The content and rank of Cricetidae are still a matter of debate. Most paleontologists assign to Cricetidae an array of the Tertiary muroids and primitive dipodoids with the so-called “cricetid dental pattern” (Schaub, Reference Schaub1930; Tong, Reference Tong1992; Gomes Rodrigues et al., Reference Gomes Rodrigues, Marivaux and Vianey-Liaud2010 ; Maridet and Ni, Reference Maridet and Ni2013). Alternatively, the group is narrowed to just a subfamily within the family Muridae (McKenna and Bell, Reference McKenna and Bell1997). We conservatively follow Mein and Freudenthal (Reference Mein and Freudenthal1971) in considering Cricetinae as a subfamily of the family Cricetidae. The genera Cricetulodon and Democricetodon Fahlbusch, Reference Fahlbusch1964 recognized here are the same as those included by Mein and Freudenthal (Reference Mein and Freudenthal1971).

Genus Neocricetodon Schaub, Reference Schaub1934

1951 Epicricetodon Reference KretzoiKretzoi, p. 407.

1969 Kowalskia Reference FahlbuschFahlbusch, p. 103.

1987 Karstocricetus Reference KordosKordos, p. 75.

Type species

Cricetulus grangeri Young, Reference Young1927.

Other species

N. grangeri (Young, Reference Young1927); N. schaubi (Kretzoi, Reference Kretzoi1951); N. polonicus (Fahlbusch, Reference Fahlbusch1969); N. magnus (Fahlbusch, Reference Fahlbusch1969); N. intermedius (Fejfar, Reference Fejfar1970); N. fahlbuschi (Bachmayer and Wilson,Reference Bachmayer and Wilson1970); N. moldavicus (Lungu, Reference Lungu1981); N. skofleki (Kordos, Reference Kordos1987); N. occidentalis (Aguilar, Reference Aguilar1982); N. yinanensis (Zheng, Reference Zheng1984); N. nestori (Engesser, Reference Engesser1989); N. polgardiensis (Freudenthal and Kordos, Reference Freudenthal and Kordos1989); N. browni (Daxner-Höck, Reference Daxner-Höck1992); N. progressus (Topachevsky and Skorik, Reference Topachevsky and Skorik1992); N. similis (Wu, Reference Wu1991); N. hanae (Qui, 1994); N. seseae Aguilar, Calvet and Michaux, Reference Aguilar, Calvet and Michaux1995; N. ambarrensis Freudenthal, Mein and Martín-Suárez, Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martin Suarez1998.

Diagnosis

Small- to medium-sized cricetids with brachydont molars. Anterolophulid of m1 predominantly labial. Labial spur on anterolophule of M1 frequently well developed. M2 four-rooted. Mesolophs, mesolophids, anterosinusid of m2 present. M3 and m3 not very much reduced and may be elongated.

Occurrence

Early late Miocene to middle Pliocene of Europe and middle late Miocene to late Pliocene of Asia.

Remarks

The congeneric status of Neocricetodon grangeri and Kowalskia polonica was clearly demonstrated by Freudenthal et al. (Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martin Suarez1998) and further corroborated by de Bruijn et al. (Reference Bruijn, Doukas, van den Hoek Ostende and Zachariasse2012). Although this matter is not accepted by some specialists (see e.g., Daxner-Höck et al., Reference Daxer-Höck, Fahlbusch, Kordos and Wu1996; Kälin, Reference Kälin1999; Kretzoi and Fejfar, Reference Kretzoi and Fejfar2004), we follow most recent authors (Sesé, Reference Sesé2006; Prieto and Rummel, Reference Prieto and Rummel2009; Maridet et al., Reference Maridet, Daxner-Höck, Dadamgarav and Göhlich2014) in recognizing the priority of the name Neocricetodon.

Daxner-Höck et al. (Reference Daxer-Höck, Fahlbusch, Kordos and Wu1996) presented an emended diagnosis of Kowalskia (=Neocricetodon) as a small to medium-sized cricetine with low-crowned molars characterized by a posteriorly divided anteroconid of m1 with a predominance of the labial anterolophulid, long mesolophs and mesolophids, wide and anteriorly split anterocone of M1, double protolophule and metalophule, and four-rooted M2. Freudenthal et al. (Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martin Suarez1998) did not include the double protolophule and metalophule as well as four-rooted condition of M2 to their diagnosis of the genus, pointing out that these characters are insufficiently reliable to differentiate Neocricetodon from morphologically similar species of Cricetulodon. Nevertheless, in Neocricetodon, even in the most primitive species, the four-rooted M2 is common and can be used in the diagnosis. Apart from this and other minor modifications, we follow the diagnosis of Neocricetodon provided by Freudenthal et al. (Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martin Suarez1998).

The taxonomic status of some species attributed to Neocricetodon remains problematic, and the genus itself appears to represent a “waste-basket” for the cricetids with a “modern” dental pattern, but still retaining well-developed extra ridges e.g. mesolophs, mesolophids, and labial spur of the anterolophule.

Neocricetodon lavocati (Hugueney and Mein, Reference Hugueney and Mein1965) was originally described as a species of Cricetulus Milne-Edvards, 1867 on the basis of a four isolated teeth—M3 (holotype) erroneously interpreted as M2; M2, M3 and m3, from Lissieu, France, latest Miocene (Hugueney and Mein, Reference Hugueney and Mein1965). The similarity between this species and Neocricetodon was soon recognized (Daxner-Höck, Reference Daxner-Höck1972). Freudenthal et al. (Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martin Suarez1998) provided some additional dental remains from the type locality, but gave neither formal diagnosis nor description and figures. Thus, N. lavocati remains poorly represented and its attribution to Neocricetodon is still uncertain.

Kowalskia gansunica Zheng and Li, Reference Zheng and Li1982 from the latest Miocene of Songshan in China is a poorly known species and represented only by the holotype (IVPP V6282), a right mandible with m1–m3 (Zheng and Li, Reference Zheng and Li1982). The original description and figures (Zheng and Li, Reference Zheng and Li1982, fig. 4), present too few characters for proper generic allocation of “Kowalskia” gansunica. Hereby, we refrain from attribution of IVPP V6282 to Neocricetodon.

Kowalskia complicidens Topachevsky and Skorik, Reference Topachevsky and Skorik1992 is known by 10 specimens, mostly isolated teeth, from the early Turolian (roughly corresponding to late Tortonian) locality Frunzovka 2 in Southern Ukraine. It was considered as a highly specialized species of the genus based on the presence of the crest-like ectoloph, similar to that of Stylocricetus Topachevsky and Skorik, Reference Topachevsky and Skorik1992, which closes the mesosinus and four-rooted M1s (Topachevsky and Skorik, Reference Topachevsky and Skorik1992). Daxner-Höck et al. (Reference Daxer-Höck, Fahlbusch, Kordos and Wu1996) noted that Kowalskia complicidens should be excluded from the genus because of its peculiar morphology. We agree with the latter authors that the species cannot be attributed to Neocricetodon. Among the cricetids it is most similar to the genus Sinocricetus Schaub, Reference Schaub1930 as indicated by the high-crowned robust teeth, strong crests and cristids, loss of M1 protolophule I, weak to absent M3 lingual anteroloph, and deeply split projecting anterocone with anterolophules being oriented strongly posteriorly. At best, it can be tentatively assigned to that genus.

Neocricetodon neimengensis (Wu, Reference Wu1991) is one of two Neocricetodon species described from the Chinese (Inner Mongolia) localities Ertemte 2 and Harr Obo 2 correlated as the latest Miocene. Our observation of the specimens from Ertemte 2 housed at Naturhistorisches Museum Wien suggests that except for the retention of primitive characters such as metalophule II and higher number of M1s with three roots, the species is identical to Neocricetodon polonicus in size and dental morphology. It seems however, these characters are not rare in N. polonicus. The newly discovered middle late Miocene, middle Turolian (roughly corresponding to early Messinian) localities Egorovka 1 and Egorovka 2 in the Southern Ukraine have yielded a several teeth of Neocricetodon species with clear N. polonicus affinities, though exhibiting a three-rooted condition of M1 and high frequency of metalophule II in M1 and M2 (Sinitsa, 2010). These minor morphological differences do not support the species status. As a result, N. neimengensis is recognized here as a junior synonym of N. polonicus.

Neocricetodon zhengi (Qui and Storch, 2000) is based on rich fossil material from the early Pliocene locality Bilike in China (Qui and Storch, 2000). The presence, albeit rare, of the metalophule II is the only difference from N. polonicus. As stated before, this character is clearly variable within populations of N. polonicus. Therefore, we regard Neocricetodon zhengi as a junior synonym of N. polonicus.

The validity of Neocricetodon progressus was questioned by Daxner-Höck (Reference Daxner-Höck1995) who suggested its referral to N. skofleki (Kordos, Reference Kordos1987). In addition to the description of newly discovered specimens from the early Turolian locality Palievo in Southern Ukraine, Sinitsa (Reference Sinitsa2012) regarded N. progressus as valid species that can be distinguished from N. skofleki by narrower M2, M3, and m1; shorter m2; predominance of four-rooted condition in M1; reduced mesolophs, mesolophids, labial spur of the anterolophule; and lack of the third cuspid in the m1 anteroconid.

Neocricetodon moldavicus (Lungu, Reference Lungu1981)

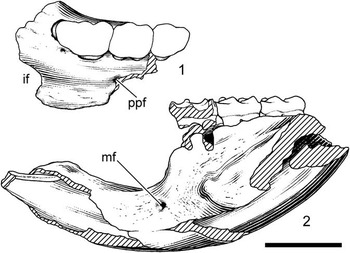

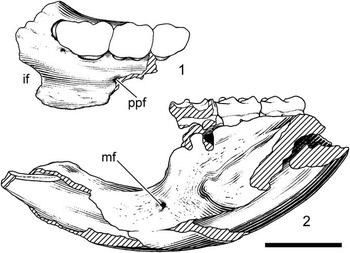

Figure 2 Neocricetodon moldavicus (Lungu, Reference Lungu1981), Calfa: (1) TSU Caf-2427, left maxillary fragment with M1–M3; (2) TSU Caf-2425, holotype, fragment of left mandible with incisor, m1–m3. if=incisive foramen, ppf=posterior palatine foramen, mf=mental foramen. Scale bar equals 3 mm.

Figure 3 Upper teeth of Neocricetodon moldavicus, Calfa (Caf) and Bujor 1 (Buj1) localities: (1) TSU Caf-2426, right with M1–M3; (2) same specimen, lateral view; (3) TSU Caf-2427, left with M1–M3; (4) TSU Buj1-434, right M1; (5) TSU Buj1-435, right M1; (6) TSU Buj1-437, left M1; (7) same tooth, medial view; (8) TSU Buj1-438, right M2; (9) same tooth, radical view; (10) TSU Buj1-461, left Isup, cross-section; (11) TSU Buj1-439, right M3; (12) TSU Buj1-440, right M3; (13) TSU Buj1-441, left M3. 1, 4, 5, 8, 11, 12: inverted. Scale bar equals 1 mm.

Figure 4 Lower teeth of Neocricetodon moldavicus, Calfa (Caf) and Bujor 1 (Buj1) localities: (1) TSU Caf-2425, holotype, left m1–m3; (2) same specimen, lateral view; (3) TSU Caf-2428, right m1–m3; (4) TSU Buj1-444, left m1; (5) TSU Buj1-446, left m1; (6) TSU Buj1-443, left m1; (7) TSU Buj1-448, right m2; (8) TSU Buj1-449, right m2; (9) TSU Buj1-455, left m2; (10) TSU Buj1-457, right m3; (11) TSU Buj1-458, left m3; (12) TSU Buj1-459, left m3; (13) TSU Buj1-460, left Iinf. 3, 7, 8, 10: inverted. Scale bar equals 1 mm.

Table 1 Dental measurements (mm) of Neocricetodon moldavicus (Lungu, Reference Lungu1981). L=maximum length, W=maximum width.

1981 Kowalskia moldavica Reference LunguLungu, p. 98, pl. 15, figs. 1A, B, 2, 3, 4.

Holotype

TSU Caf-2425, fragment of left mandible with incisor, m1, m2, and m3; Calfa, Moldova (Lungu, Reference Lungu1981, pl. 15, figs. 1a, b).

Amended diagnosis

Small- to medium-sized Neocricetodon. M1 with anterocone often deeply split; mesoloph moderately developed, labial spur of anterolophule weakly developed; protolophule I absent to short; metalophule I absent; lateral margin discernibly concave. M1 has three roots. M3 subcircular, its lingual anteroloph weak or absent. In m1, anteroconid weakly divided and bicuspid. Anterolophulid double. Mesolophids moderately developed, short to medium length in m1, nearly long in m2. Ectomesolophid of m1 indistinct. m2 lacks lingual anterolophid.

Occurrence

Early late Miocene of Moldova.

Description

Maxilla (Fig. 2.1). In ventral view, the palate is broad and smooth. The incisive foramen is moderately expanded, its posterior edge ends anterior to M1. A small and rounded posterior palatine foramen is present on the maxilla-palatine suture at about the level of M2 trigone.

Mandible (Fig. 2.2). The mandibular body has a derived morphology of cricetines. The diastemal region is slender and not as massive as that of cricetodontines. Its length is about 5.03 mm, longer than the total length of m1–m3. The diastemal depression is deep and the posterior border of the diastema curves abruptly downward from the anterior end of m1. An oval and small mental foramen is high on the mandible roughly at the one-third of the diastema depth and anterior to the m1. The masseteric fossa is a narrow, semitriangular surface on the lateral side of the mandible, with its anterior margin terminating at the level of the posterior root of m1. The ascending ramus raises lateral to the anterior portion of the m3 and ascends steeply. On the medial side of the mandible, a poorly defined symphyseal surface occupies the anteromedial part of the diastemal region and fades out before reaching its posteroventral edge.

The M1 is roughly oval to rectangular in occlusal outline, with concave labial edge, tapering anteriorly to a rounded anterior edge (Fig. 3.1–3.7). Transition from anterocone to protocone is clearly defined. The anterocone is split by a deep, longitudinal groove into labial and lingual cones of about equal size. TSU Caf-2427 shows an unsplit anterocone with a distinct pit on its posterior wall (Fig. 3.2). A weak and interrupted anterolophs depart from behind the lingual and labial sides of the anterocone and enclose the protosinus and anterosinus. A narrow lingual anterolophule connects the lingual anterocone cusp to the protocone. The labial anterolophule is quite variable, ranging from completely absent in specimens from Calfa (TSU Caf-2426; TSU Caf-2427) and two teeth from Bujor 1 (TSU Buj1-435; TSU Buj1-462); to a long and merged with the lingual anterolophule in three specimens. A weakly developed knob-like labial spur of the anterolophule can be observed in three M1s from Bujor 1. One specimen from Calfa (TSU Caf-2427) bears the labial spur on the anterolophule of medium length (Fig. 3.2). The protolophule I is absent in five specimens and present in two. The protolophule II joins the paracone on its posterior wall. The entoloph is long, straight and oriented posterolaterally. The mesoloph is low, weakly to moderately developed and does not reach the labial border, absent in three, short in two, of medium length in one, and long in two specimens. The metalophule I is lacking, though TSU Buj1-437 has a short mesoloph directed posteriorly and connected to metacone thus shows a metalophule-like appearance (Fig. 3.6). The metalophule II is lacking in four of five M1s from Bujor 1. The specimens from Calfa possess a weak and narrow metalophule II. The posteroloph is thin and long, merging with the metacone on the posterolateral side to delimit a large posterosinus. The metacone is large and strongly expands laterally. Sinus and mesosinus are deep, rounded, transverse, and partially closed by low cingula, which rarely bear stylar cuspules. The tooth possesses three roots, the lingual one being anteroposteriorly elongated with a shallow longitudinal groove on its external side (Fig. 3.7).

The M2 is subrectangular in occlusal outline, with anterior part being slightly wider than the posterior part (Fig. 3.8, 3.9). Both lingual and labial anterolophs are well developed and roughly equal in length. The lingual one is lower and thinner. The protolophule I is present. The mesoloph is moderately developed; it may reach the labial border, merging with the paracone spur (TSU Caf-2426), is of medium length (TSU Buj1-438) or short (TSU Caf-2427). The metalophule I is present in specimens from Calfa, but lacking in tooth from Bujor 1. The metalophule II is always present. The tooth is four-rooted.

The M3 has rounded to trapezoidal occlusal outline, with a distinct indentation on the lateral side (Fig. 3.1–3.3, 3.11–3.13). A long labial anteroloph extends from the anterolophule to the labial edge, forming a deep, crescent-shaped anterosinus. The lingual anteroloph is lacking in both specimens from Calfa, while present, albeit weak, in M3s from Bujor 1. A well-defined protolophule I directed posterolaterally and connects to the protocone. In TSU Caf-2426 and TSU Caf-2427 the protolophule II forms a distinct additional branch turning to the protocone. Therefore, the anterior mesosinus is divided into two small basins. Three of the five M3s show a short, anteriorly directed and incomplete mesoloph. The metacone is reduced and nearly merged into the posteroloph. However, this character depends on the state of wear. For example, in a moderately worn specimen TSU Buj1-439 the metacone is rounded and cusp-like (Fig. 3.11). A metacone spur is often present, but is variable in length. The M3s from Calfa have a short metacone spur, while those from Bujor 1, except for TSU Buj1-439, have a longer metacone spur that encloses a mesosinus. The tooth is three-rooted.

There is an isolated right upper incisor from Bujor 1 originally referred to murids. Reexamination of this specimen shows it to be cricetid and tentatively assigned here to N. moldavicus (Fig. 3.10). The incisor is greatly mediolaterally compressed and roughly oval in cross-section with strong flattening of the labial and lingual sides, comparable to the condition in some sigmodontines (Oryzomys Baild, 1857; Peromyscus Gloger, 1841). The enamel band covers about one-third of labial side and ends abruptly reaching the lingual side. The outer enamel surface is smooth apart from a smooth longitudal rib at the anteromedial edge.

The m1 is triangular to rectangular in occlusal outline with a relatively short anteroconid and swollen posterior part (Fig. 4.1–4.6). The anteroconid is bifid, but only barely separated into two cusps. It is unsplit in three specimens, and in the other four only the mesial part of the anteroconid is strongly constricted, though possibly bilobed when unworn. All teeth show a discernible cleft on its posterior side. The anterior face of the anteroconid is smooth and gently rounded. The lingual anterolophulid is a short connection between the anteroconid and the metalophulid. Out of the nine m1s, two specimens (TSU Buj1-443; TSU Buj1-444) lack the lingual anterolophulid. The labial anterolophulid, being more pronounced, is discernable in nearly all m1s. There is no distinct labial spur of the anterolophulid. The mesolophid is variable in size. Most of specimens have a short to medium length mesolophid decreases in height. It is nearly absent in four m1s (TSU Caf-2428; TSU Buj1-442; TSU Buj1-445; TSU Buj1-447), represented only by a swelling at the center of the ectolophid. The ectomesolophid does not exist in any of the specimens. A massive posterolophid runs posteriorly from the hypoconid, curving medially and joining the entoconid, delimiting the posterosinusid.

The occlusal outline of m2 is a rounded rectangle (Fig. 4.1, 4.2, 4.7–4.9). The tooth is narrowed at the junction between talonid and trigonid. The labial anterolophid extends to the lateral base of the protoconid and tends to enclose the protosinusid. In contrast, the lingual anterolophid is often absent. When present, it is just a swelling at the anterior wall of the metalophulid (TSU Buj1-450; TSU Buj1-454; TSU Buj1-455), rather than a weak crest (TSU Buj1-448). The mesolophid is slightly anteriorly directed. It is long and reaches the lingual margin in four specimens, and of medium length in six m2s. Two teeth, TSU Caf-2428 and TSU Buj1-452, exhibit a very short, reduced mesolophid. The majority of specimens lack entomesolophid; it is discernible in one tooth from Bujor 1 (TSU Buj1-455). The strong posterolophid completely encloses a deep posterosinusid depression. Nearly all m2s show a well-developed labial posterolophulid.

The m3 is rounded triangle to trapezoid with roughly straight anterior and labial edges (Fig. 4.1–4.3, 4.10–4.12). The tooth show little variation in a structure of the occlusal surface. Both the labial anterolophid and anterolophulid are similar to those of m2. The lingual anterolophid is a small, medially oriented swelling. TSU Buj1-458 has a well-developed but low lingual anterolophid that forms a narrow anterosinusid. The mesolophid is directed posteriorly and long in all but one specimen, TSU Buj1-459, which shows a transversal mesolophid is of medium length (Fig. 4.12). Reaching the lingual border of the tooth crown, mesolophid forms a crest-like mesostylid that connects with entoconid. The latter one shows some degree of reduction, so it is hardly discernible from the hypolophulid in some slightly-worn molars (TSU Caf-2430, TSU Buj1-459). The large circular posterosinusid is delimited by a long and hook-shaped posterolophid.

The lower incisors are approximately oval in cross section, with a round or roughly flattened ventral face, an nearly straight lingual side, and a flat or slightly convex labial side (Fig. 4.13). The enamel covers the ventral face and forms a fine longitudinal rib along the lingual side. On the surface of the enamel on the ventral side, one, rather two, smooth longitudinal ridges are discernible.

Materials

Calfa: TSU Caf-2426, right maxillary fragment with M1, M2, and M3; TSU Caf-2427, left maxillary fragment with M1, M2, and M3; TSU Caf-2425, fragment of left mandible with incisor, m1, m2, and m3; TSU Caf-2428, fragment of right mandible with m1, m2, and m3; TSU Caf-2429, fragment of left mandible with m1, m2, and m3; TSU Caf-2430, fragment of right mandible with m2 and m3.

Bujor 1: TSU Buj1-434, right M1; TSU Buj1-435, right M1; TSU Buj1-436, right M1; TSU Buj1-437, left M1; TSU Buj1-462, anterior fragment of left M1; TSU Buj1-438, right M2; TSU Buj1-439, right M3; TSU Buj1-440, right M3; TSU Buj1-441, left M3; TSU Buj1-461, left Isup; TSU Buj1-442, right m1; TSU Buj1-443, left m1; TSU Buj1-444, left m1; TSU Buj1-445, left m1; TSU Buj1-446, left m1; TSU Buj1-447, left m1; TSU Buj1-448, right m2; TSU Buj1-449, right m2; TSU Buj1-450, right m2; TSU Buj1-451, right m2 with anterior border broken; TSU Buj1-452, right m2 with posterolateral border broken; TSU Buj1-453, left m2; TSU Buj1-454, left m2; TSU Buj1-455, left m2; TSU Buj1-456, left m2; TSU Buj1-457, right m3; TSU Buj1-458, left m3; TSU Buj1-459, left m3; TSU Buj1-460, left Iinf.

Remarks

The dental morphology of Calfa and Bujor 1 specimens is that of a typical member of the genus Neocricetodon, with an elongated mesolophs, mesolophids, and the labial spur on the anterolophule of M1. Derived characters of Neocricetodon present in N. moldavicus include well-developed labial anterolophule of M1, four-rooted M2, and a salient labial anterolophulid of m1. The M3s are elongate and show no signs of reduction.

There are eighteen species of the genus. The type species Neocricetodon grangeri is only known from the holotype, a fragmentary skull associated with a pair of mandibles and a few postcranial elements from the locality Chia Yu Tsun, China, latest Miocene (Young, Reference Young1927; Schaub, Reference Schaub1930; Daxner-Höck et al., Reference Daxner-Höck1992). It differs from Neocricetodon moldavicus in having smaller m2 and m3, longer mesolophs and mesolophids, barely divided anteroconid in m1, and extended lingual anterolophid in m2.

Neocricetodon schaubi from the middle late Miocene locality Csákvár in Hungary (Kretzoi, Reference Kretzoi1951; Kordos, Reference Kordos1987; Kretzoi and Fejfar, Reference Kretzoi and Fejfar2004) differs from N. moldavicus in possession of clearly divided M1 anterocone, a straight lateral edge of M1. The metalophule I, labial spur of the anterolophule, mesolophs, and mesolophids are constantly present and well developed.

Neocricetodon polonicus from the early Pliocene locality Podlesice in Poland (Fahlbusch, Reference Fahlbusch1969) is small in almost all dental measurements and falls outside the lower limits of the specimens of N. moldavicus. Other distinctions between the species include longer mesolophs, mesolophids, and labial spur of the anterolophule, lack of the metalophule II of M1, the predominance of four-rooted M1s, and well-developed lingual anterolophid in m2.

The second species of Neocricetodon described from Podlesice, Neocricetodon magnus (Fahlbusch, Reference Fahlbusch1969), is easily distinguished from N. moldavicus in its significantly larger size, single-cusped anteroconid in m1, stronger mesolophs and mesolophids. The M1 lingual root of N. magnus is bisected by a prominent medial groove or completely split into two smaller roots.

Neocricetodon intermedius, the latest European species of the genus, is only known from the type locality Ivanovce in the Slovak Republic (Fejfar, Reference Fejfar1970), correlated with the late early Pliocene. The species differs from N. moldavicus in being larger; having wide, bulky, and deeply split anterocone of M1, well-developed mesolophs and mesolophids. The M1s of N. intermedius are always four-rooted and lacking the metalophule II.

Neocricetodon fahlbuschi is known by abundant and well-preserved fossils from the middle late Miocene locality Kohfidisch, Austria (Bachmayer and Wilson, Reference Bachmayer and Wilson1970; Bachmayer and Wilson, 1978; Bachmayer and Wilson, Reference Bachmayer and Wilson1980; Freudenthal et al., Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martin Suarez1998). This species is larger than N. moldavicus, has longer mesolophs, mesolophids, and M1 labial spur of the anterolophule. The upper teeth, M1 and M2, show a higher frequency of protolophule I. More than 40% of M1s are four-rooted.

Neocricetodon occidentalis from the type locality Crevillente 2 in Spain, middle late Miocene (de Bruijn et al., Reference Bruijn, Mein, Montenat and van de Weerd1975; Aguilar, Reference Aguilar1982; Freudenthal et al., Reference Freudenthal, Lacomba and Martin Suárez1991; Freudenthal et al., Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martin Suarez1998) has a larger size, longer anterior portion of M1 and m1, a better developed mesolophs, mesolophids, and metalophules of M1, rounded M3 with reduced talon and stronger lingual anteroloph of M1, and higher frequency of four-rooted M1s.

Neocricetodon yinanensis is a poorly known species, represented by only a few, albeit nearly complete, mandibles and two imperfect skulls from the middle Pliocene locality Yinan in China (Zheng, Reference Zheng1984b). The cheek teeth of N. yinanensis, are easily separable from those of N. moldavicus by being larger with longer mesolophs and mesolophids, better developed lingual anterolophid of m2, bulky and a long anterior portion of M1 and m1. All M1s have four roots.

Neocricetodon skofleki from the type locality Tardosbánya, Hungary, middle late Miocene (Kordos, Reference Kordos1987; Freudenthal and Kordos, Reference Freudenthal and Kordos1989) differs from N. moldavicus in having pronounced mesolophs and mesolophids, wider anterocone of M1 with long labial spur of the anterolophule, rather well-developed metalophule I of M1 and the lingual anterolophid of m2.

Neocricetodon nestori from the “Locality 1” of Baccinello in Italy, latest Miocene (Engesser, Reference Engesser1989), differs from N. moldavicus in being larger, having elongated mesolophs and mesolophids, reduced M3, four-rooted M1s with enlarged anterocone and well-developed protolophule I.

Neocricetodon polgardiensis, known from more than a thousand and a half specimens from the latest Miocene karstic locality Polgárdi 4 in Hungary (Freudenthal and Kordos, Reference Freudenthal and Kordos1989), is a large member of Neocricetodon, comparable in size to N. fahlbuschi. Apart from its much larger size, the species differs from N. moldavicus in longer mesolophs, mesolophids, and labial spur of the anterolophule; and constantly present lingual anterolophid of m2. In M1 and m1, the anterior portion is massive with divided anterocone and anteroconid; a half of M1s bear the metalophule I. The ectomesolophids of m1 and m2 are often present.

Neocricetodon browni from the latest Miocene Greek locality Maramena (Daxner-Höck, Reference Daxner-Höck1992; Daxner-Höck, Reference Daxner-Höck1995) is a relatively large-sized species that differs from N. moldavicus in clearly divided, broad anterocone and anteroconid in M1 and m1, longer mesolophs, mesolophids, and labial spur of the anterolophule. In M1 and M2, the protolophule I, metalophule I, and metalophule II are frequently present. In M3 and m2, the lingual anteroloph and lingual anterolophid respectively are more pronounced.

Neocricetodon progressus from the middle late Miocene locality Novoelizavetovka 2, Ukraine (Topachevsky and Skorik, Reference Topachevsky and Skorik1992; Sinitsa, Reference Sinitsa2012), has a wider anteroconid of M1 with cusps and cuspids being deeply split, more pronounced labial spur of the anterolophule and the metalophule I of M1, better developed lingual anteroloph of M3 and lingual anterolophid of m2, and much higher percentage of four-rooted M1s.

Neocricetodon similis from the type locality Ertemte 2 in China, latest Miocene (Wu, Reference Wu1991), differs from N. moldavicus in having longer mesolphs and mesolophids, better developed anterocone, metalophule I, labial spur of the anterolophule, and the four root of M1. The m2s are often with lingual anterolophid.

Neocricetodon hanae from the Shihuiba Formation at Lufeng locality in China is the only well-known middle late Miocene species of the genus in Asia. It differs from N. moldavicus in having a relatively larger anteroloph of M1 with the main cusps being distinctly separated, more pronounced mesolophs, mesolophids, metalophule I of M1, and labial spur of the anterolophule, better developed lingual anteroloph of M3, and the lingual anterolophid of m2. Furthermore, N. hanae from the type locality has over 40% of M1s being four-rooted.

Neocricetodon seseae from the middle late Miocene Castelnou 1 locality in France (Aguilar et al., Reference Aguilar, Calvet and Michaux1995; Freudenthal et al., Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martin Suarez1998) possesses a derived dental morphology, similar to that in N. moldavicus. In addition to its larger anterocone and anteroconid of M1 and m1, N. seseae has a longer mesolophs and mesolophids, a straight labial edge of M1, and an elongated M3 crown. In m1, the anteroconid shows a strong tendency to tripartition.

Among the species of Neocricetodon, N. moldavicus seems closest to N. ambarrensis from the middle late Miocene (Vallesian or early Turolian) locality Ambérieu 2C in France (Freudenthal et al., Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martin Suarez1998). The species shares with N. moldavicus a rather simple dental pattern with shortened mesolophs, mesolophids, labial spure of the anterolophule, and bicuspid, albeit barely divided, anterocone of M1. However, N. ambarrensis is separable from N. moldavicus by smaller M2, M3, m2, and m3, well-developed and constantly present labial anteroloph of M3, and much higher frequency of the lingual anterolophid on m2.

Lungu (Reference Lungu1981) considered Neocricetodon moldavicus as one of the most primitive species of the genus on the basis of its generalized dental morphology, including the narrow and undivided anterocone and anteroconid on first molars, presence of the third anterolophulid of m1. This view was partially accepted by Wu (Reference Wu1991), Daxner-Höck (Reference Daxner-Höck1992) and Sinitsa (Reference Sinitsa2012). Careful examination of the type material leads us to the conclusion that most characters used by Lungu were rather misinterpreted due to either rough preparation or poor preservation of the specimens. For instance, an undivided and solid anterocone of M1 was originally described for TSU Caf-2426 (Lungu, Reference Lungu1981, pl. 15, fig. 4). Actually, the anterocone of this specimen was broken off presumably after the tooth had been already fossilized, and its morphology cannot be adequately evaluated. Contrary to original concept of N. moldavicus, we identify this species as having rather advanced dental morphology.

Both samples from Calfa and Bujor 1 undoubtedly represent a single species. However, there are subtle differences in their morphology. In contrast with the specimens from Bujor 1, all teeth from Calfa display a more generalized dental morphology in having a narrower anterocone of M1 and m1 anteroconid with less divided cusps and cuspids, retaining primitively elongated mesolophs, mesolophids as well as the labial spur of the anterolophule. We consider these minor differences as variability and leave them without any taxonomic consequences. Indeed, the more primitive appearance of the Calfa specimens may represent a population of an older geological age.

The type and 34 referred specimens, from Calfa and Bujor 1 localities, are the only fossils formally described for N. moldavicus. However, this species has been subsequently documented in faunal lists from the late Miocene localities Girovo and Veveritsa 1 in Moldova (Lungu and Rzebik-Kowalska, Reference Lungu and Rzebik-Kowalska2011). Three isolated teeth from Girovo (right M2, TSU Gir-2; left m2, TSU Gir-3; left m3, TSU Gir-4) apparently represent Neocricetodon, though possessing expanded mesoloph and mesolophids along with strong lingual anterolophid of m2, a condition unknown in N. moldavicus. We have not found any Cricetidae fossils from Veveritsa 1 either in the TSU or related collections. Nonetheless, recent field work at Veveritsa 1, carried on in August 2010, has yielded two additional specimens, an isolated left M2 and right m2 of Neocricetodon. These teeth more closely resemble the specimens from Girovo then those of N. moldavicus in having an elongated mesoloph, mesolophid, and the m2 lingual anterolophid. Because of their fragmentary nature the remains from Girovo and Veveritsa 1 cannot be referred to N. moldavicus or any other species of the genus.

Phylogenetic analysis

We performed a cladistic analysis to produce a phylogenetic hypothesis of Neocricetodon and to determine the phylogenetic position of N. moldavicus within the genus. Only 15 species, those with known intraspecific variation, were included in the analysis. The poorly known species N. magnus, N. schaubi, N. seseae, and N. yinanensis were excluded. Morphological data were assessed by studying the type material of N. browni (UUN and NMW), N. fahlbuschi (NMW), N. moldavicus (TSU), N. progressus (NMNHU-P), and some additional materials of N. polonicus from Podlesice, N. similis from Ertemte 2, N. skofleki from Eichkogel, Democricetodon affinis (Schaub, 1925) from La Grive M, and D. gaillardi (Schaub, 1925) from Sansan (NMW). In other cases, character scores were taken from the literature. The genus Cricetulodon, exemplified by Cricetulodon sabadellensis Hartenberger, Reference Hartenberger1966 from Can Llobateres (Hartenberger, Reference Hartenberger1966; Freudenthal et al., Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martin Suarez1998), was included to test the monophyly of Neocricetodon and to provide a context for assigning the sister group of the genus. Character polarity was determined by outgroup comparison using Democricetodon affinis from La Grive M, D. gaillardi from Sansan, and D. freisingensis from Giggenhausen, and the tree was rooted on D. affinis. The data matrix includes 22 characters (Table 2), 13 of which are multistate (characters 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 17, 18, 21; three character states each). A few species preserve details of the cranial anatomy, but most include only teeth. For this reason, all of the morphologic data are dental. All, but eight characters (1, 2, 3, 4, 10, 15, 16, 22) were treated as unordered, with equal weighting. Multiple states were considered to represent intraspecific variation. The matrix was analyzed using the branch and bound algorithm of PAUP 4.0b10 (Swofford, Reference Swofford1999). To evaluate node support, 1,000 bootstrap replicates were generated in PAUP using a heuristic search algorithm. Mesquite 3.04 (Maddison and Maddison, Reference Maddison and Maddison2003) was used for examination of character-state distributions.

Table 2 Data matrix for cladistic analysis of species of Neocricetodon. Codes for ambiguity character states: 01=A, 12=B, 02=C.

Analysis of the matrix produced five most parsimonious trees, each 48 steps long, a consistency index of 0.708, and a retention index of 0.825. All topologies showed the integrity of the Neocricetodon as a clade, including N. moldavicus, which nested well within it (Fig. 5). With inclusion of “Kowalskia cf. schaubi” from Rudabánya the genus is found to be non-monophyletic. “Kowalskia cf. schaubi” should therefore be excluded from the genus. The Neocricetodon clade is defined by the following unequivocal characters: presence of the M1 labial anterolophule, four-rooted M2, and presence of the labial anterolophulid on m1 (Fig. 6). It is also supported by an expansion of the M1 anterocone (CI=0.667) and by presence of the metalophule I on M2 (CI=0.500; reversed in N. grangeri). In all five topologies, the advanced Neocricetodon species, N. browni, N. polgardiensis, N. similis, and N. skofleki form a clade (referred to as clade A), which is sister to another one (clade B) composed of N. intermedius and N. polonicus. These two clades are nested successively with a more remote N. nestori and N. grangeri. Despite the weak support of clade A and B as sister taxa by a single homoplastic character, the affinities of these clades with N. nestori and N. grangeri are corroborated by at least two unambiguously placed synapomorphies (Fig. 6). N. hanae and N. fahlbuschi are recovered as a sister clade to aforementioned taxa. The interrelationships between the basal members of the genus are less certain mostly because of their similar dental morphology. The strict consensus tree revealed N. ambarrensis and N. moldavicus as a distinct clade, which is a sister group to a clade comprising N. occidentalis and N. progressus (Fig. 5.1). The 50% majority rule consensus tree (Fig. 5.2) further resolves these clades, with N. ambarrensis reconstructed as a basalmost member of the genus, followed by N. moldavicus, N. progressus, and N. occidentalis, which form a series of stem taxa.

Figure 5 Strict (1) and majority rule (2) consensus cladograms showing interrelationships among Neocricetodon species. The indices on the strict consensus tree show bootstrap and Bremer Support for the different nodes.*“Kowalskia cf. schaubi” from Rudabánya.

Figure 6 Majority rule consensus tree of Neocricetodon showing character-state changes; see Appendix for explanation of numbered characters. Solid circle=strict synapomorphy, empty circles=homoplasy (parallelism or reversal). Numbers above the branches indicate characters and those below indicate character states.

Discussion

Phylogeny

The origin of Neocricetodon is traditionally linked with the derived species of Democricetodon, but it is not yet clear whether the species could be its direct ancestor. Most authors followed Fahlbusch (Reference Fahlbusch1969) in considering D. gaillardi (Mein and Freudenthal, Reference Mein and Freudenthal1971; Wu, Reference Wu1991; Heissig, Reference Heissig1995) or D. freisingensis (Fejfar et al., 2007), as a plausible ancestor for Neocricetodon. However, the possibility of an origin from as yet unknown species cannot be ruled out and even seems more plausible (Kälin, Reference Kälin1999). Although Democricetodon and early Neocricetodon species may be differentiated on a few characters, these two genera are in fact difficult to distinguish based on available dental remains. This difficulty is further complicated by their similar size and stratigraphic overlap as can be clearly seen in the Rudabánya and Suchomasty samples. Moreover, the broadening and splitting of the M1 anterocone and m1 anteroconid, which are commonly used to define the members of Neocricetodon (Fahlbusch, Reference Fahlbusch1969; Daxner-Höck, Reference Daxner-Höck1972; Kordos, Reference Kordos1987; Daxner-Höck et al., Reference Daxer-Höck, Fahlbusch, Kordos and Wu1996; Kälin, Reference Kälin1999; Kretzoi and Fejfar, Reference Kretzoi and Fejfar2004), are also present in primitive cricetines genera Megacricetodon, Democricetodon, Schizocricetodon Kälin and Engesser, 2001 (Fahlbusch, Reference Fahlbusch1964; Kälin and Engesser, Reference Kälin and Engesser2001), Cricetulodon, Nannocricetus Schaub, Reference Schaub1934, and Stylocricetus (Freudenthal, Reference Freudenthal1967; Wu, Reference Wu1991; Topachevsky and Skorik, Reference Topachevsky and Skorik1992; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wang, Liu and Liu2011). Therefore, the definition of Neocricetodon should not be limited to these homoplastic characters. Our phylogenetic analyses indicate five Neocricetodon synapomorphies: presence of the labial anterolophule in M1, four-rooted M2, presence of the labial anterolophulid of m1, expansion of the M1 anteroloph, and the presence of the M2 metalophule I. These are broadly concordant with the diagnostic traits proposed by Freudenthal et al. (Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martin Suarez1998), whereas the last two characters are homoplastic and reversed in a few clades, so they seem to be phylogenetically irrelevant.

The fossil record of Neocricetodon extends as far back as the early late Miocene, which is roughly consistent with the genetically estimated date of early cricetine diversification at 10.8–12.2 Ma (Neumann et al., Reference Neumann, Michaux, Lebedev, Yigit, Colak, Ivanova, Poltoraus, Surov, Markov, Maak, Neumann and Gattermann2006). Although the assignment of N. moldavicus to Neocricetodon is well supported, the presence of the genus reported from the early late Miocene (Vallesian) localities Rudabánya (Kordos, Reference Kordos1987; Kretzoi and Fejfar, Reference Kretzoi and Fejfar2004), Vösendorf (Daxner-Höck, 1971), and Suchomasty (Fejfar, Reference Fejfar1990) in Central Europe is less evident. The oldest of these finds, described as Kowalskia cf. schaubi from the early Vallesian of Rudabánya, is morphologically most primitive. It does not present any labial anterolophule in M1 nor signs of a fourth root in M2. It displays a complete metalophule II and a strong lingual anterolophulid of m1 with the labial one being only weakly developed. Some characters shared with Neocricetodon and early cricetines, such as a broad anterocone and anteroconid of M1 and m1 respectively, are interpreted as homoplasies here. It appears to have a definite Democricetodon morphology and, given their occurrence in the same locality, should be referred to this genus. A few cricetine teeth from the early Vallesian of Vösendorf in Austria have been interpreted by Daxner-Höck (1971) as the earliest record of Kowalskia (=Neocricetodon). Unfortunately, it is difficult to confirm the systematic position of the species given that it’s M2, M3, and especially m1 are unknown. The available specimens possess an array of plesiomorphic character states shared with ancient cricetines, while lacking any Neocricetodon synapomorphies, and thus could not be assigned to this genus. The forms from Rudabánya and Vösendorf, albeit advanced in having the enlarged M1 anterocone and m1 anteroconid and the presence of the metalophule I in M1, retain a rather generalized cricetine dental morphology. We consider them to represent an advanced Democricetodon, which, based on the derived character combination, could be the most plausible candidates for the ancestors of Neocricetodon known to date. Kowalskia cf. fahlbuschi was reported from the late Vallesian locality Suchomasty in the Czech Republic (Fejfar, Reference Fejfar1990). Judging from the figures (no description was provided in the original study) we suppose those specimens may be referred to Neocricetodon for the reasons given above. It apparently represents the second earliest record of the genus followed after the appearance of N. moldavicus at the beginning of the late Vallesian. The co-occurrence of two distantly related European Neocricetodon species at roughly the same time and the lack of certain members of the genus in the early Vallesian, suggests an early Vallesian origin, and subsequent “explosive” basal radiation of Neocricetodon.

Paleobiogeography

Another point of controversy concerns the place of Neocricetodon origin. In recent studies, the European origin for the genus seems to be favored (Kälin, Reference Kälin1999; Fejfar et al., Reference Fejfar, Heinrich, Kordos and Maul2011). It is believed to have evolved from an advanced species of European Democricetodon and subsequently spread to Asia, probably early late Miocene (Fejfar et al., Reference Fejfar, Heinrich, Kordos and Maul2011; Kretzoi and Fejfar, Reference Kretzoi and Fejfar2004, Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zheng and Liu2008; Wu, Reference Wu1991). This assumption has been supported by the presence of Neocricetodon in the Vallesian of Central Europe, whereas no reliable evidence of the genus or its immediate ancestors are known in Asia prior to middle late Miocene of the Chinese Yuanmou Basin, Shihuiba, and Bahe formations (Qui, Reference Qiu1995; Qui and Qui, Reference Qiu and Qiu1995; Qui et al., Reference Qiu, Wu and Qiu1999; Ni and Qui, Reference Ni and Qiu2002; Deng, Reference Deng2006; Qi et al., Reference Qi, Dong, Zheng, Zhao, Gao, Yue and Zhang2006; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zheng and Liu2008). The presence of N. moldavicus, certainly an advanced Neocricetodon, in the early late Miocene of Eastern Europe provides a strong argument for the European origin of the genus. However, it is possible that a vast gap in the Asian fossil record of early late Miocene (11.2–9.5 Ma), rather than evolutionary phenomena, is responsible for the lack of the early members of Neocricetodon or their ancestors in Asian faunas. Several occurrences of the genus have been included in the faunal lists of Chinese localities dated between 8.7 and 7.2 Ma (Qui, 2002; Dong and Qi, Reference Dong and Qi2013; Qui et al., Reference Qiu, Wang and Li2013). So, it seems that center of origin of Neocricetodon is yet to be discovered.

Our phylogenetic analysis suggests a close relationship between N. moldavicus, N. progressus, N. ambarrensis, and N. occidentalis. Freudenthal et al. (Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martin Suarez1998) considered that “western populations” of Neocricetodon, containing N. ambarrensis, N. occidentalis, and N. seseae, represent a detached branch of the genus and supposed that “N. ambarrensis to be an immigrant from the East”. This hypothesis seems to be corroborated by our results indicating a close phylogenetic relationship between N. ambarrensis, N. occidentalis and the East European species N. moldavicus and N. progressus. Although N. moldavicus could not be a direct ancestor for any of the mentioned species, it predates the oldest N. ambarrensis fossil record (late Vallesian or early Turolian at Ambérieu 2C and Cucalón), and is remarkably consistent with the estimate appearance of Neocricetodon in Western Europe (Freudenthal et al., Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martin Suarez1998; Mein, Reference Mein1999). This time interval corresponds to the early-late Vallesian boundary, which was characterized by an extensive faunal interchange between Europe, Africa, and Asia and coincides with the appearance of murids and advanced cricetids in the Mediterranean area (Aguilar and Michaux, Reference Aguilar and Michaux1996; Freudenthal et al., Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martin Suarez1998).

Acknowledgments

For access to the collections of fossil rodents in their care, we are grateful to N. Volontir and the late A. Lungu (Tiraspol State University, Kishinev), and U. Göhlich (Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Austria). We also thank A.S. Tesakov (Institute of Geology, Moscow), S. Čermák (Institute of Geology, Prague), L. Maul (Senckenberg Research Institute, Frankfurt), D.V. Ivanoff (National Museum of Natural History, Kiev), and G. Daxner-Höck (Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Austria) for advice and useful comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to M. Freudenthal (University of Granada, Granada) and other referees for their constructive reviews. MS was supported by Act 211 Government of the Russian Federation, contract № 02.A03.21.0006.

Appendix

Characters included in the phylogenetic analysis

1. Number of M1 roots: three (0); three, with a lingual root being deeply grooved (1); four (2).

2. M1 labial and lingual anterocone: undivided (0); partially divided (1); deeply divided (2).

3. M1 anterocone proportions: short and narrow (0); moderately expanded (1); long and broad (2).

4. M1 labial anterolophule: absent (0); present in less than 50% of specimens (1); present in more than 50% of specimens (2).

5. M1 lingual anteroloph: complete, connected with the anterocone (0); incomplete and weak, isolated from the anterocone (1).

6. M1 labial spur of the anterolophule: complete (0); incomplete (1); short to absent (2).

7. M1 protolophule I: absent (0); present (1).

8. M1 mesoloph: complete (0); incomplete (1); short to absent (2).

9. M1 metalophule I: absent (0); present (1).

10. M1 metalophule II: present (0); vestigial (1); absent (2).

11. Number of M2 roots: three (0); four (1).

12. M2 mesoloph: complete (0); incomplete (1); short to absent (2).

13. M2 metalophule I: absent (0); present (1).

14. M2 metalophule II: present (0); vestigial (1); absent (2).

15. M3 lingual anteroloph: present (0); absent (1).

16. m1 anteroconid: undivided (0); weakly to moderately divided (1); deeply divided (2).

17. m1 anterolophulid: lingual (0); double (1); labial (2).

18. m1 mesolophid: complete (0); incomplete (1); short to absent (2).

19. m1 ectomesolophid: present (0); absent (1).

20. m2 lingual anterolophid: present (0); absent (1).

21. m2 mesolophid: complete (0); incomplete (1); short to absent (2).

22. m2 ectomesolophid: present (0); absent (1).