Introduction

The generic diversity of trilobites, one of the important benthic organisms, was apparently increasing, and reached a major peak, on a global scale during the Darriwilian (Adrain, Reference Adrain, Harper and Servais2013). The Darriwilian trilobites of South China have been reported by various authors (e.g., Lu and Zhang, Reference Lu and Zhang1974; Lu, Reference Lu1975; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Yin and Tripp1984, Reference Zhou, Yuan and Zhou2001, Reference Zhou, Bergström, Zhou, Yuan and Zhang2011, Reference Zhou, Luo, Yin, Hu and Zhan2014a; Chen and Zhou, Reference Chen and Zhou2002; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Zhou, Hu, Zhan and Lu2014a, Reference Luo, Zhou, Hu, Zhan and Lub; Wei and Yuan, Reference Wei and Yuan2015; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Zhou, Zhan, Yan and Liu2021), and their radiation pattern and biogeographic links have been discussed in detail by Zhou and Dean (Reference Zhou and Dean1989), Zhou et al. (Reference Zhou, Yuan and Zhou2007), Zhou and Zhen (Reference Zhou and Zhen2008), Wei (Reference Wei2020), and Wei et al., Reference Wei, Zhou, Zhan, Yan and Liu2021. Most of them were documented from the clastic rocks on the Upper Yangtze Region, while these trilobites preserved in the limestone are rarely known, which limits our understanding of the macroevolution and paleobiogeography of trilobites during this interval. During the past three years, we have conducted a systematic investigation on the Darriwilian trilobites from the carbonate strata on the basis of detailed study of four sections on the Upper Yangtze Region. In this study, we document two new trilobite genera and six species and further discuss their macroevolutionary and paleobiogeographic significance.

Materials and ages

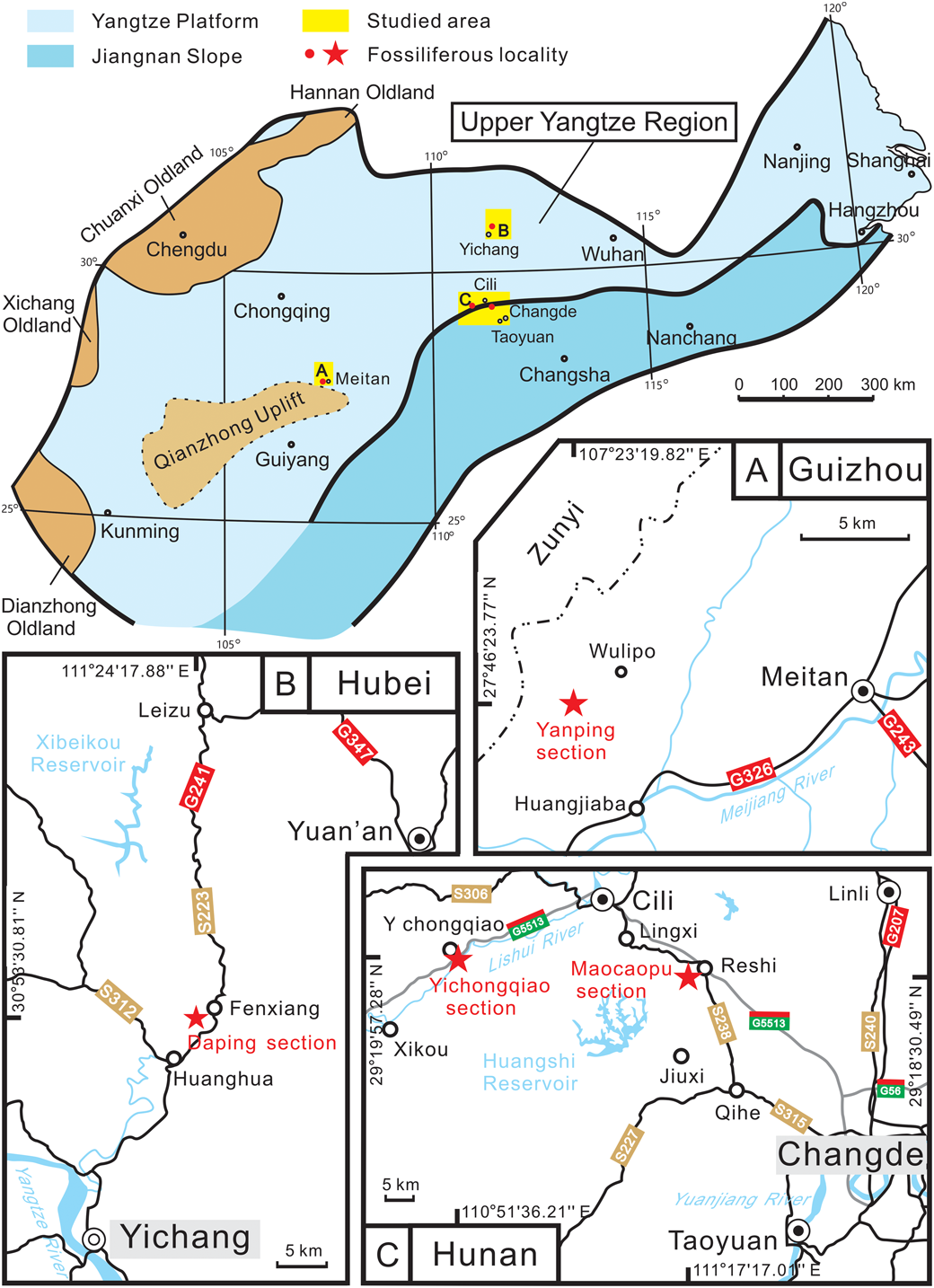

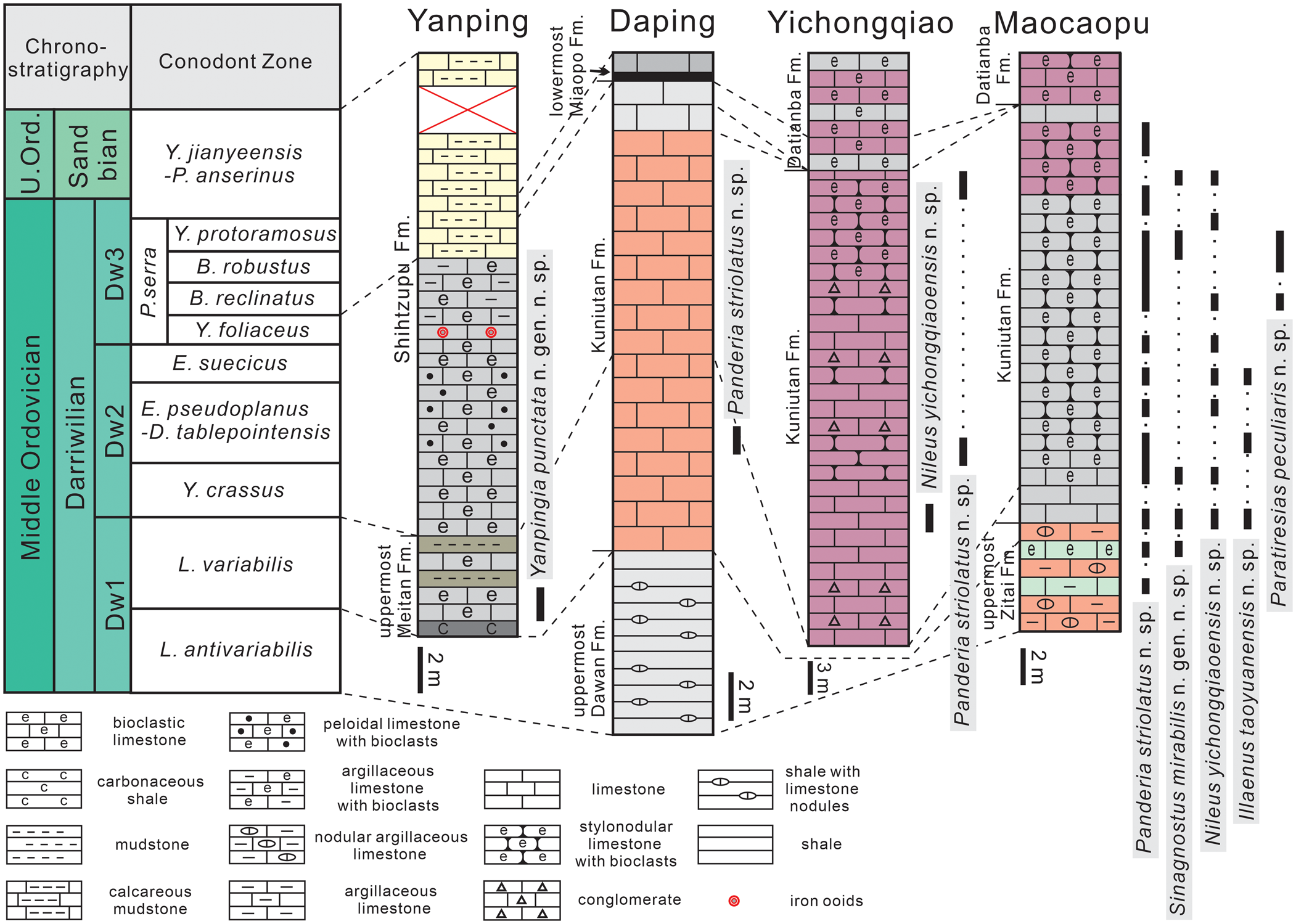

All specimens studied in this paper are collected from various limestone horizons of the Darriwilian age in the Upper Yangtze Region of South China (Figs. 1, 2), such as the uppermost Meitan Formation at the Yanping section of Guizhou Province (27°46′23.77″N, 107°23′19.82″E) and the Kuniutan Formation at the Daping section of Hubei Province (30°53′30.81″N, 111°24′17.88″E), as well as the uppermost Zitai and Kuniutan formations at the Maocaopu section (29°18′30.49″N, 111°17′17.01″E) and the Yichongqiao section (29°19′57.28″N, 110°51′36.21″E) of northwestern Hunan Province. A few specimens reported by Zhou et al. (Reference Zhou, Yuan and Zhou2001) from the Kuniutan Formation of the Yichongqiao and Maocaopu sections are also included to support the establishment of new species Nileus yichongqiaoensis n. sp. and Paratiresias peculiaris n. sp., respectively.

Figure 1. Map showing the paleogeography of the South China plate of the Darriwilian (late Middle Ordovician) and geographic location of studied sections (modified from Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zhou and Zhang2002; Zhang, Reference Zhang2016).

Figure 2. Stratigraphic columns and stratigraphic occurrences of two new genera and six new species of trilobites at Yanping, Daping, Yichongqiao, and Maocaopu sections (ages of the formations are based on Lindström et al., Reference Lindström, Chen and Zhang1991; Zhang, Reference Zhang1998; Wu, Reference Wu2011; Z.Q. Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Zhou and Xiang2016).

The age constraint on the studied material is based on conodonts preserved together with the trilobites (Fig. 2) (Lindström et al., Reference Lindström, Chen and Zhang1991; Zhang, Reference Zhang1998; Wu, Reference Wu2011; Z.Q. Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Zhou and Xiang2016). In addition, the uppermost Meitan Formation at the Yanping section yields conodont Erraticodon hexianensis An and Ding, Reference An and Ding1985 (Fig. 3), which is also discovered from the Lenodus variabilis Biozone recognized at the Honghuayuan section of Tongzi County, northern Guizhou Province (Zhen et al., Reference Zhen, Liu and Percival2007), indicating an early Darriwilian age.

Figure 3. Erraticodon hexianensis An and Ding, Reference An and Ding1985 from the uppermost Meitan Formation (lower Darriwilian), Yanping section, northern Guizhou Province. (1) Lateral view of Sc element, NIGP 173219. (2) Lateral view of Sc element, NIGP 173220. Scale bars = 100 um.

Morphological terminology and abbreviations applied in this paper are from Shergold et al. (Reference Shergold, Laurie and Sun1990) and Whittington and Kelly (Reference Whittington, Kelly and Kaesler1997). Systematic arrangement follows the classification of Adrain (Reference Adrain and Zhang2011).

Repository and institutional abbreviation

All specimens are deposited at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, with a prefix “NIGP” for their catalogue numbers.

New taxa and ecological associations

Two new genera and six new species were discovered from four studied sections along a bathymetric gradient across the Upper Yangtze Region. At the Yanping section, Yanpingia punctata n. gen. n. sp. together with Liomegalaspides asiaticus (Weller, Reference Weller1907) and rare Neseuretus paronai (Pellizzari, Reference Pellizzari1913) were collected from the uppermost Meitan Formation (Dw1), which belong to the Liomegalaspides Association living in an inner shelf environment (Wei, Reference Wei2020). At the Daping section, there are seven genera and eight species in the lower Kuniutan Formation (Dw1): Panderia striolatus n. sp., Nileus armadilloformis Lu, Reference Lu1957, Hexacopyge nasutus (Lu, Reference Lu1957), Agerina elongata Lu, Reference Lu1975, Agerina sp., Illaenus sinensis Yabe in Yabe and Hayasaka, Reference Yabe and Hayasaka1920, Carolinites ichangensis Lu, Reference Lu1975, and Mioptychopyge chengkouensis Wei and Zhou in Wei et al., Reference Wei, Zhou, Zhan, Yan and Liu2021. At the Yichongqiao section, the Kuniutan Formation (Dw2) yields eight genera and 10 species: Nileus yichongqiaoensis n. sp., Panderia striolatus n. sp., Nileus armadilloformis Lu, Reference Lu1957, Nileus sp., Hexacopyge sp., Birmanites sp., Geragnostus sp., Agerina sp., Ovalocephalus sp., and Microparia (Quadratapyge) taoyuanensis Z.Q. Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Zhou and Xiang2016. The trilobites at these two sections are dominated by Nileus and assigned to the Nileid Biofacies living in an upper outer shelf environment (sensu shallow out shelf in Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Yuan and Zhou2001; Wei, Reference Wei2020). In addition, the Nileid–Microparia (Quadratapyge) Biofacies is well developed in the uppermost Zitai and the Kuniutan formations (Dw1-2) of the Maocaopu section and composed of 18 genera or subgenera and 23 species: Sinagnostus mirabilis n. gen. n. sp., Illaenus taoyuanensis n. sp., Paratiresias peculiaris n. sp., Nileus yichongqiaoensis n. sp., Panderia striolatus n. sp., Illaenus sinensis Yabe in Yabe and Hayasaka, Reference Yabe and Hayasaka1920, Illaenus sp., Nileus armadilloformis Lu, Reference Lu1957, Microparia (Quadratapyge) taoyuanensis Z.Q. Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Zhou and Xiang2016, Geragnostus (Novoagnostus) cf. G. (N.) symmetricus (Zhou in Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Lee and Qu1982), Geragnostus (Geragnostella) sp., Geragnostus (Geragnostella) cf. G. (G.) carinatus Lu, Reference Lu1975, Geragnostus (Geragnostus) balanolobus Turvey, Reference Turvey2004, Agerina sp., Trinodus sp., Mioptychopyge semicircula Z.Y. Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Zhou and Yin2016, Mioptychopyge sp., Ovalocephalus primitivus (Lu in Lu and Zhang, Reference Lu and Zhang1974), Hexacopyge nasutus (Lu, Reference Lu1957), “Eccoptochile” sp., Rorringtonia triquetra (Apollonov, Reference Apollonov1974), aulacopleurid gen. indet. sp. indet., and niobinid gen. indet. sp. indet., indicating a lower outer shelf environment (sensu deep outer shelf in Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Yuan and Zhou2001; Wei, Reference Wei2020).

Macroevolutionary and paleobiogeographic significances

The genera and species reported herein add new data for the global trilobite diversity of the Darriwilian. According to the changes in trilobite diversity in South China, three macroevolutionary phases were recognized from the Darriwilian: the radiation phase, the decline phase, and the reradiation phase (Wei, Reference Wei2020). From the early to middle Darriwilian, although the genus-level diversity of the South China trilobites experienced a gradual decline, it still had a high speciation rate as we recorded herein. The newly documented taxa, Sinagnostus n. gen. (Metagnostidae), Yanpingia n. gen. (Asaphidae), Nileus Dalman, Reference Dalman1827 (Nileidae), and Panderia Volborth, Reference Volborth1863 (Panderiidae), belong to the Ibex Fauna, while the other two genera, Illaenus Dalman, Reference Dalman1827 (Illaenidae) and Paratiresias Petrunina in Repina et al., Reference Repina, Yaskovich, Aksarina, Petrunina, Poniklenko, Rubanov, Bolgova, Golikov, Hajrullina and Posochova1975 (Isocolidae), are referred to the Whiterock Fauna (see Adrain et al., Reference Adrain, Fortey and Westrop1998; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Yuan and Zhou2007). Obviously, the Ibex Fauna (part of the Cambrian Evolutionary Fauna) exceeded the Whiterock Fauna (part of the Paleozoic Evolutionary Fauna) in proportion, which was consistent with trilobites in South China during this time (Wei, Reference Wei2020).

The possible evolutionary relationships between these new and related taxa are proposed herein on the basis of the systematic paleontology in detail. For example, Sinagnostus n. gen. may originate from Geragnostus (Geragnostella) Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1939 by progressive degeneration of the cephalon and complication of the exoskeleton ornament. Those Chinese species previously treated as Nanillaenus Jaanusson, Reference Jaanusson1954 are reassigned to Illaenus sensu lato, which could be a separate evolutionary lineage unrelated to that of Thaleops Conrad, Reference Conrad1843 in Laurentia. Three species of Panderia, Panderia? lubrica Z.Y. Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Zhou and Yin2016, Panderia dayongensis (Ji, Reference Ji1987), and Panderia striolatus n. sp., are interpreted herein as one species group on the basis of the totally effaced axial furrows on the cranidium. Paratiresias peculiaris n. sp., as the earliest species of the genus, has an extremely narrow (sag. and exsag.) preglabellar field, which is totally absent on its descendants. This evolutionary trend may be the reflection of ontogeny recapitulating phylogeny, like Phorocephala (see Chatterton, Reference Chatterton1980, p. 29–32).

Among the six genera described herein, three are cosmopolitan (Illaenus, Nileus, and Panderia), one regionally widespread (Paratiresias), and the other two endemic to South China (Sinagnostus n. gen. and Yanpingia n. gen.). The widespread Panderia was distributed mainly in Baltica as well as Taurides, Tarim, North China, South China, Sibumasu, Kazakhstan, Avalonia, Armorica, and Iberia during the late Dapingian to Hirnantian (see the following for the species and occurrences of Panderia). It is interesting to note that three species, Panderia? lubrica, Panderia dayongensis, and Panderia striolatus n. sp., as a species group, are distributed in North China, Tarim, and South China, respectively, suggesting a close link between these paleoplates. Paratiresias was uncommon and confined to low and middle latitudes along the eastern Peri-Gondwana plates or terranes, including Kazakhstan (Petrunina in Repina et al., Reference Repina, Yaskovich, Aksarina, Petrunina, Poniklenko, Rubanov, Bolgova, Golikov, Hajrullina and Posochova1975), Alborz (Karim, Reference Karim2008), Sibumasu (Z.-Y. Zhou, personal communication, 2019), North China (Zhou and Dean, Reference Zhou and Dean1986), and South China (this paper) during the middle Darriwilian to the middle Katian. At species level, five of the six taxa described herein (Sinagnostus mirabilis n. gen. n. sp., Yanpingia punctata n. gen. n. sp., Panderia striolatus n. sp., Nileus yichongqiaoensis n. sp., and Paratiresias peculiaris n. sp.), as far as we know, have been found only in South China, while Illaenus taoyuanensis n. sp. has also been reported from the coeval strata of Tarim (Zhang, Reference Zhang1981; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Dean, Yuan and Zhou1998a). As such, the trilobites in the study area have a strong endemicity and show a faunal link with eastern Peri-Gondwana at low and middle latitudes, e.g., Tarim, Kazakhstan, Alborz, Sibumasu, and North China.

Systematic paleontology

Class Trilobita Walch, Reference Walch1771

Order Agnostida Salter, Reference Salter1864

Family Metagnostidae Jaekel, Reference Jaekel1909

=Trinodidae Howell, Reference Howell1935; Geragnostidae Howell, Reference Howell1935; Arthrorhachidae Raymond, Reference Raymond1913 (see Fortey, Reference Fortey1980a, p. 24)

Genus Sinagnostus new genus

Type species

Sinagnostus mirabilis n. sp., uppermost Zitai and Kuniutan formations (lower–middle Darriwilian), Maocaopu, Taoyuan County, Hunan Province.

Diagnosis

As for the type species.

Etymology

From Latin Sino meaning “China,” where all currently known specimens of this new agnostid trilobite were collected.

Remarks

It is currently known that Metagnostidae Jaekel, Reference Jaekel1909 consists of eight genera and six subgenera: Chatkalagnostus Hajrullina and Abdullaev in Abdullaev and Khaletskaya, Reference Abdullaev and Khaletskaya1970, Corrugatagnostus Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1939, Dividuagnostus Koroleva, Reference Koroleva1982, Galbagnostus (Galbagnostus) Whittington, Reference Whittington1965, Galbagnostus (Granuloagnostus) Pek, Reference Pek1970, Geragnostus (Geragnostus) Howell, Reference Howell1935, Geragnostus (Geragnostella) Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1939, Geragnostus (Novoagnostus) Nielsen, Reference Nielsen1997, Geragnostus (‘Neptunagnostella’) Pek, Reference Pek1977, Homagnostoides Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1939, Trinodus M'Coy, Reference M'Coy1846, and Sinagnostus n. gen. (Arthrorhachis Hawle and Corda, Reference Hawle and Corda1847 has been treated as a junior homonym of Trinodus, see Owen and Parkes, Reference Owen and Parkes2000; Turvey, Reference Turvey2004; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Yin and Zhou2014b). Type species of Sinagnostus n. gen., Sinagnostus mirabilis n. sp., displays a faint and arched forward F3, the lack of F2, a media tubercle of glabella behind F3, a short pygidial axis, and anterolateral lobes that are isolated by oblique F1 posteriorly, all of which correspond to those of Metagnostidae Jaekel, Reference Jaekel1909 (see Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Laurie and Sun1990, p. 53).

Among the agnostids known, only two genera are lacking a lateral border of the cephalon: Denagnostus Jago, Reference Jago1987 and Sinagnostus. Although both forms have an effaced exoskeleton, the posterior axial lobe of Denagnostus is longer, expanding backward and just reaching the posterior border furrow, and its posterior border bears a low ridge and a pair of small posterolateral spines (see type species Denagnostus corbetti Jago, Reference Jago1987, p. 213, pl. 24, figs. 13–19, pl. 25, figs. 1, 2). Sinagnostus is also similar to Geragnostus (‘Neptunagnostella’), basing on an effaced exoskeleton, but the latter has a smooth exoskeleton, a complete cephalic border, an obvious preglabellar furrow, and no terminal tubercle of pygidial axis (see type species Agnostus consors Holub, Reference Holub1912, p. 6, pl. 1, fig. 5; Pek, Reference Pek1977, p. 15, pl. 3, fig. 5). Furthermore, Sinagnostus may be closer to Geragnostus (Geragnostella) than to G. (‘Neptunagnostella’) on the morphology, including a relatively long pygidial axis and a long and faintly outlined M3 (>M1 + M2) with a small terminal tubercle, but differs mainly in having a more ambiguous glabella, no lateral border of the cephalon, a convex forward tubercle that lies at the middle part of M2, and dense fine pits on the exoskeleton. It does seem possible that this new genus was derived from G. (Geragnostella) by progressive degeneration of the cephalon and complication of the exoskeleton ornament.

Sinagnostus mirabilis new species

Figure 4

Holotype

NIGP 172776 (Fig. 4.1, 4.2), one cephalon, Kuniutan Formation (Dzikodus tablepointensis Conodont Zone, middle Darriwilian), Maocaopu, Taoyuan County, Hunan Province.

Figure 4. Sinagnostus mirabilis n. gen. n. sp. from the uppermost Zitai and Kuniutan formations (lower–middle Darriwilian), Maocaopu section, northwestern Hunan Province. (1, 2) Dorsal view and scanning electron microscopy of cephalon, holotype NIGP 172776. (3) Dorsal view of cephalon, paratype NIGP 172777. (4, 5) Dorsal and posterior views of cephalon with an attached thoracic segment, paratype NIGP 172778. (6, 7) Dorsal and lateral views of cephalon, paratype NIGP 172779. (8) Dorsal view of pygidium, paratype NIGP 172780. (9) Dorsal view of pygidium, paratype NIGP 172781. (10) Dorsal view of pygidium, paratype NIGP 172782. (11) Dorsal view of pygidium, paratype NIGP 172783. (12) Dorsal view of pygidium, paratype NIGP 172784. Scale bars = 1 mm.

Diagnosis

Exoskeleton is almost effaced and covered with dense and fine pits. Anterior cephalic border narrows posteriorly and disappears at about 42–48% of cephalic length from the front. Pygidial border is smooth without posterolateral spines. F2 is arched anteriorly. An elongated and slightly convex forward tubercle is located at the middle part of M2. M3 is conical in outline, and its length is slightly longer than that of the posteroaxis. Faintly outlined M3 has a small terminal axial tubercle.

Description

These materials have been reported by Wei (Reference Wei2020) as Sinagnostus zhoui in Chinese. The cephalon is almost effaced, strongly convex, and subcircular in outline; the maximum width (tr.) lies at 35% of cephalic length (sag.) from the posterior margin, occupying 94–98% of cephalic length. The anterior border is arched forward and slightly convex, well defined by anterior border furrow; its length (sag.) is about 11% of cephalic length (sag.); narrowing posteriorly and disappearing at about 42–48% of cephalic length from the front. The lateral border is completely absent. The posterior margin is nearly straight, with triangular posterolateral spines on both sides. The glabella is conical in outline, tapering gently forward, and occupying 64% of cephalic length. The maximum glabellar width (tr.) along the posterior margin is about 75% of glabellar length (sag.) and 52% of the maximum cephalic width (tr.). The anterior lobe is effaced; the posterior lobe is convex, rounded posteriorly, and pointed at rear end. Axial furrows become shallower anteriorly and disappear. Basal lobes are subtriangular in outline, isolated by shallow and curved oblique furrows. Glabellar median tubercle is small and visible at 33–34% of cephalic length from posterior margin. F1 and F2 are absent; faint F3 is convex anteriorly and located in front of median tubercle.

The axial ring is trapezoid in outline, well defined by axial furrows. Pleural field is narrow (tr.), the width of which is about 50% that of the axial ring. Pleural furrow is short (tr.) and deep.

Only convex median tubercle and obscure axis can be observed on external surface of pygidium. Pygidium is elongated oval in outline; the maximum width (tr.) is 92–96% of its sagittal length (excluding articulating half ring). Articulating half ring is transverse and defined by deep articulating half-ring furrow, its length (sag.) is about 13% of axial length (sag.). Anterior shoulders are ridge-like, extending posterolaterally. Posterior border is convex, and its width (sag.) is about 14–16% of sagittal length of pygidium (excluding articulating half ring), narrowing anteriorly and forming ridge-like lateral border. Posterior part of border furrow is narrow (sag.), while the sides widen (tr.) gradually. Pygidial border is smooth without posterolateral spines. Axis is convex and triangular in outline, tapering rapidly backward, about 52–55% of pygidial width anteriorly (tr.) and 60–67% of sagittal length of pygidium (excluding articulating half ring). Anterolateral lobes are subtetragonal shape, well defined by oblique F1 posteriorly. Middle part of M1 is trapezoid in outline, merging with M2 backward. F2 is arched anteriorly. M2 is slightly longer than M1 (sag.). An elongated and slightly convex forward tubercle is located at the middle part of M2. M3 is conical in outline and slightly longer than length (sag.) of the sum of M1 and M2. Faintly outlined M3 has a small terminal tubercle. On a few specimens, a pair of oval muscle impressions is present on both sides of M2; in addition, two lines of punctate muscle impressions lie on M3, which meet at the terminal tubercle or slightly back. Pleural field is strongly convex, inclining laterally and posteriorly to border furrow. Length (sag.) of posteroaxis occupies 19–25% of sagittal length of pygidium (excluding articulating half ring). Exoskeleton is covered with dense and fine pits.

Etymology

From Latin mirabilis, meaning “queer,” referring to the strange appearance of the cephalic border.

Materials

Eight paratype specimens, three cephala, and five pygidia (NIGP 172777–172784), uppermost Zitai and Kuniutan formations (Lenodus antivariabilis–Dzikodus tablepointensis conodont zones, lower–middle Darriwilian), Maocaopu, Taoyuan County, Hunan Province.

Remarks

Compared with Geragnostus (Geragnostella) fenhsiangensis Lu (Reference Lu1975, p. 92, pl. 1, figs. 9, 10; Turvey, Reference Turvey2004, p. 535, fig. 7d–o) from the relatively lower strata of South China, besides the lack of a lateral border of the cephalon, Sinagnostus mirabilis n. sp. has a shallow and narrow (sag. and exsag.) anterior border furrow, an obscure glabella, a narrowing anteriorly pygidial border, a deep and broad (tr.) lateral border furrow of pygidium, a convex forward tubercle that is located at the middle part of M2, and exoskeleton surface that is covered with dense and fine pits.

Order Corynexochida Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935

Suborder Illaenina Jaanusson, Reference Jaanusson and Moore1959

Family Illaenidae Hawle and Corda, Reference Hawle and Corda1847

Subfamily Illaeninae Hawle and Corda, Reference Hawle and Corda1847

Genus Illaenus Dalman, Reference Dalman1827

Type species

Entomostracites crassicauda Wahlenberg, Reference Wahlenberg1818, Crassicauda Limestone (uppermost Darriwilian), Fjäcka, Siljan, Sweden; by subsequent designation of Pictet (Reference Pictet1854).

Illaenus taoyuanensis new species

Figure 5

- Reference Zhang1981

Nanillaenus? primitivus Zhang, p. 194, pl. 70, fig. 6a–e (part; not fig. 5a, b).

- Reference Zhou, Dean, Yuan and Zhou1998a

Nanillaenus? primitivus; Zhou et al., p. 718, pl. 7, figs. 1, 2, 6 (part; not pl. 6, figs. 5, 7, 8, 10, 11).

Figure 5. Illaenus taoyuanensis n. sp. from the Kuniutan Formation (lower–middle Darriwilian), Maocaopu section, northwestern Hunan Province. (1–4) Dorsal, posterior, anterior, and lateral views of cranidium, holotype NIGP 172801. (5–8) Dorsal, posterior, anterior, and lateral views of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172803. (9) Dorsal view of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172802. (10) Dorsal view of librigena, paratype NIGP 172806. (11, 12) Dorsal and posterior views of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172804. (13) Dorsal view of pygidium, paratype NIGP 172807. (14) Dorsal view of pygidium, paratype NIGP 172808. (15) Dorsal view of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172805. Scale bars = 2 mm.

Holotype

NIGP 172801 (Fig. 5.1–5.4), one cranidium, Kuniutan Formation (Dzikodus tablepointensis Conodont Zone, middle Darriwilian), Maocaopu, Taoyuan County, Hunan Province.

Diagnosis

A species of Illaenus with transversely broad cranidium, strongly abaxially protruded palpebral area, and short (sag.) pygidium with narrow (tr.) axis.

Occurrence

Lower to middle Darriwilian strata in South China (Hunan Province) and Tarim (Xinjiang).

Description

Transversely broad and semielliptical cranidium, with a narrow (sag. and exsag.) marginal rim, curving downward strongly in front of palpebral lobes, nearly 50–56% as long as wide. Glabella is convex (tr.) and basal width 38–42% of the maximum cranidial width between palpebral lobes. There are four pairs of muscle impressions at least, including elliptical 2P and 3P and oval 1P and 4P (Fig. 5.15). Axial furrows are deep and broad posteriorly, converging slightly forward as far as the level of the anterior end of the palpebral lobe, in front of which they become shallower and divergent for a short distance before dying out. Palpebral lobe is semicircular and placed posteriorly; its length is equal to 36% of sagittal cranidial length in palpebral view. Palpebral area is strongly abaxially protruded. Palpebral ridge is faint, extending anteromedially to axial furrows (Fig. 5.9). Anterior branches of facial sutures are long and slightly convergent forward, cutting anterior margin in a rounded angle; posterior branches are very short and obliquely directed outward. Librigena is broad (tr.) and triangular in outline, with crescentic eye, sharply raised eye socle, and narrowly rounded genal angle.

Pygidium is short (sag.) and transverse, about 41–44% as long as wide, with strongly oblique facet distally. Narrow (tr.) axis is gently convex and triangular in outline, rapidly tapering posteriorly, occupying 28–31% of pygidial width anteriorly and 56–60% of pygidial length (sag.). Axis is defined by shallow axial furrows and divided by shallow and transverse ring furrows into four axial rings at least (Fig. 5.13). Doublure is roughly uniform width (Fig. 5.13), occupying 40% of pygidial length (sag.).

External surface of cranidium is covered with fine terrace lines subparallel to anterior margin, while surface of librigena bears oblique terrace lines. Surface of pygidium is smooth, but pygidial doublure has terrace lines parallel to lateral margins. Some irregular pits distribute on internal surface of cranidium and pygidium.

Etymology

The name is derived from Taoyuan County, Hunan Province, where the type specimens were collected.

Materials

Seven paratype specimens, four cranidia, two pygidia, and one librigena (NIGP 172802–172808), Kuniutan Formation (Lenodus variabilis–Yangtzeplacognathus crassus conodont zones, lower–middle Darriwilian), Maocaopu, Taoyuan County, Hunan Province.

Remarks

The phylogenetic analysis has been applied by Amati and Westrop (Reference Amati and Westrop2004) to systematically revise the relationships between Illaenus, Nanillaenus, and Thaleops. The result indicates that the species of Illaenus are a paraphyletic group and require major revision, while the species of Nanillaenus and Thaleops form a monophyletic group, so Nanillaenus is synonymized with Thaleops, all of which has also been followed by Shaw and Bolton (Reference Shaw and Bolton2011) and Carlucci and Westrop (Reference Carlucci and Westrop2015). Previously described Chinese illaenids bearing strongly abaxially protruded palpebral area and short (sag.) pygidium with strongly oblique facet distally have been assigned by various authors (e.g., Lee, Reference Lee1978; Zhang, Reference Zhang1981; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Dean, Yuan and Zhou1998a, Reference Zhou, Dean and Luo2014b; Turvey and Zhou, Reference Turvey and Zhou2004; Zhou and Zhou, Reference Zhou, Zhou, Zhou and Zhen2008) to Nanillaenus Jaanusson, Reference Jaanusson1954. Although those Chinese species share characters with type species Nanillaenus conradi (Billings, Reference Billings1859) (see Amati and Westrop, Reference Amati and Westrop2004, p. 225, pl. 7, figs. 1–4), such as transversely broad cranidium and pygidium and abaxially protruded palpebral area, Nanillaenus conradi has a longer and stronger oblique facet distally, an obvious pygidial axis slowly tapering posteriorly, and surface of cranidium and pygidium covered with dense and coarse pits. In addition, the type species of Thaleops, Thaleops ovata Conrad, Reference Conrad1843 (see Amati and Westrop, Reference Amati and Westrop2004, p. 215, pl. 1–3, figs. 1, 2), is totally different from this new species in having a well-defined glabella, a pair of stalked eyes, and a strongly convex pygidial axis.

Overall, it seems that the new form is unable to be assigned to either Nanillaenus or Thaleops. Some similar morphological features, such as broad palpebral area, short (sag.) pygidium, long and strongly oblique facet, and indistinct pygidial axis, are present in a few species of Illaenus and Thaleops (e.g., Illaenus consimilis Billings, Reference Billings1865, see Whittington, Reference Whittington1965, p. 393, pl. 50–52; Thaleops marginalis [Raymond, Reference Raymond1925], see Whittington, Reference Whittington1965, p. 389, pl. 46, figs. 7, 9, 11, 12, pl. 47, pl. 48, figs. 1–6, 8, 10); all of these are more likely to be convergent. More interestingly, the cranidial surface of this new species is covered with fine terrace lines rather than coarse pits like Thaleops species. This ornament is common in Illaenus species, so we temporarily assigned it to Illaenus sensu lato.

Partial materials from the upper Dawangou Formation (lower–middle Darriwilian) of Kalpin area of Xinjiang considered to be Nanillaenus? primitivus Zhang, Reference Zhang1981 by Zhang (Reference Zhang1981, p. 194, pl. 70, fig. 6a–e) and Zhou et al. (1998a, p. 718, pl. 7, figs. 1, 2, 6) are treated as Illaenus taoyuanensis n. sp. herein. Illaenus taoyuanensis is distinguished from Illaenus crassus Zhou et al. (2014b, as Nanillaenus crassus, p. 41, fig. 20) and Illaenus primitivus Zhang (Reference Zhang1981, as Nanillaenus? primitivus, p. 194, pl. 70, fig. 5a, b) in having a broader cranidium and pygidium, a longer librigena, and a narrower (tr.) pygidial axis. In addition, it bears a strong resemblance to Illaenus consimilis Billings, Reference Billings1865 (see Whittington, Reference Whittington1965, p. 393, pl. 50–52) from the middle of Table Head Formation (middle Darriwilian) of western Newfoundland, but the latter has a longer (sag.) pygidium (about 51–53% as long as wide rather than 41–44% of new species) that is covered with terrace lines subparallel to the lateral margin.

Family Panderiidae Bruton, Reference Bruton1968

Genus Panderia Volborth, Reference Volborth1863

= Rhodope Angelin, Reference Angelin1854 (see Bruton, Reference Bruton1968, p. 5); Parabumastides Ji, Reference Ji1987 (see Zhou and Zhou, Reference Zhou, Zhou, Zhou and Zhen2008, p. 260); Qijiangia Xiang and Ji, Reference Xiang and Ji1988 (see Zhou and Zhou, Reference Zhou, Zhou, Zhou and Zhen2008, p. 260)

Type species

Panderia triquetra Volborth, Reference Volborth1863, Kunda Stage?, St Petersburg, Russia; by original designation.

Other species

Panderia monodi Dean, Reference Dean1973 from the upper Dapingian to lower Darriwilian of Turkey; Panderia striolatus n. sp. from the lower–middle Darriwilian of South China; Panderia ramosa Bruton, Reference Bruton1968 from the lower–middle Darriwilian of Sweden; Panderia? lubrica from the middle Darriwilian of North China; Panderia baltica Bruton, Reference Bruton1968 from the middle Darriwilian of Sweden; Panderia lerkakensis Bruton, Reference Bruton1968 from the uppermost Darriwilian of Sweden; Panderia derivata Bruton, Reference Bruton1968 from the Darriwilian of Sweden; Panderia migratoria Bruton, Reference Bruton1968 from the latest Sandbian–early Katian of Norway and the Sandbian of Thailand; Nileus beaumonti Rouault, Reference Rouault1847 from the upper Darriwilian of France; Panderia arcutata Z.Q. Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Zhou and Xiang2016 from the upper Darriwilian–Sandbian of South China; Parabumastides dayongensis Ji, Reference Ji1987 from the upper Darriwilian–Sandbian of South China; Illaenus parvulus Holm, Reference Holm1882 from the upper Sandbian–lower Katian of Sweden; Panderia hadelandica Bruton, Reference Bruton1968 from the middle Katian of Norway; Panderia curta Petrunina in Repina et al., Reference Repina, Yaskovich, Aksarina, Petrunina, Poniklenko, Rubanov, Bolgova, Golikov, Hajrullina and Posochova1975 (= Panderia orbiculata Ji, Reference Ji1986; Nileus fenxiangensis Xiang and Zhou, Reference Xiang, Zhou, Wang, Xiang, Ni, Zeng, Xu, Zhou, Lai and Li1987; Qijiangia szechuanensis Xiang and Ji, Reference Xiang and Ji1988; see Z.Q. Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Zhou and Xiang2016) from the middle Katian of Turkestan and Alai ranges; Panderia erratica Bruton, Reference Bruton1968 from the middle–upper Katian of Sweden; Panderia insulana Bruton, Reference Bruton1968 from the upper Katian of Norway; Panderia megalophthalma Linnarsson, Reference Linnarsson1869 from the upper Katian of Sweden; Panderia balashovae Krylov, Reference Krylov2018 from the Katian of Leningrad region, Russia; Panderia koshkarovi Krylov, Reference Krylov2018 from the Katian of Leningrad region, Russia; Illaenus (Panderia) lewisi Salter, Reference Salter1867 from the Upper Ordovician of England; Nileus beaumonti Rouault, Reference Rouault1847 from the Upper Ordovician of Portugal; Panderia edita Bruton, Reference Bruton1968 from the Hirnantian of Sweden.

Occurrence

Upper Dapingian to Hirnantian strata in Europe (Turkey, Sweden, Norway, France, England, Portugal, and Russia), Turkestan and Alai ranges, Thailand, North China, and South China.

Panderia striolatus new species

Figure 6

- Reference Zhou, Yuan and Zhou2001

Panderia sp. Zhou et al., p. 76, fig. 4E, F.

Figure 6. Panderia striolatus n. sp. from the uppermost Zitai and Kuniutan formations (lower–middle Darriwilian), Maocaopu section, northwestern Hunan Province. (1–4) Dorsal, anterior, ventral, and lateral views of cephalon, holotype NIGP 172819. (5) Dorsal view of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172820. (6, 7) Dorsal and lateral views of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172821. (8–10) Dorsal, anterior, and lateral views of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172822. (11) Dorsal view of librigena, paratype NIGP 172825. (12) Dorsal view of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172824. (13) Dorsal view of librigena, paratype NIGP 172826. (14) Dorsal view of librigena, paratype NIGP 172827; the Kuniutan Formation, lower Darriwilian, Daping section, western Hubei Province. Scale bars = 2 mm.

Holotype

NIGP 172819 (Fig. 6.1–6.4), one cephalon, Kuniutan Formation (Yangtzeplacognathus crassus Conodont Zone, middle Darriwilian), Maocaopu, Taoyuan County, Hunan Province.

Diagnosis

A species of Panderia that displays fine terrace lines subparallel to anterior margin on frontal area but lacks marginal rim on cranidium. Axial furrows are totally effaced. Cranidial median tubercle is situated slightly anterior at the mid-length of palpebral lobes in palpebral view. Librigena is narrow (tr.).

Occurrence

Lower to middle Darriwilian strata in South China (Hubei and Hunan provinces).

Description

Cephalon is semielliptical in outline, about 64–67% as long as wide in dorsal view. In palpebral view, cephalon is subelliptical in outline, about 70% as long as wide. Cranidium is broadly rounded forward and absent marginal rim on frontal margin, strongly curving downward anteriorly in front of palpebral lobes, and its length (sag.) is equal to 77–84% of width (tr.) in palpebral view. Small median tubercle is situated slightly anterior at the mid-length of palpebral lobes in palpebral view. Axial furrows are totally effaced. Palpebral lobe is crescentic in shape, 46–51% as long as cranidial length, and located at the mid-length in palpebral view. Anterior branches of facial sutures are slightly convergent forward; posterior branches are long, extending posteriorly to cut posterior margin of cephalon. Cephalic doublure is broad (sag. and exsag.) and covered with fine terrace ridges parallel to anterior margin. Librigena is narrow (tr,) and crescentic in outline with rounded genal angle, steeply inclining posterolaterally, with narrow (tr.) marginal rim dying out at posterior margin. Eye is large and crescent-shaped and composed of many small lenses. Fine terrace lines are present on frontal area and subparallel to anterior margin.

Etymology

From Latin striolatus meaning “striolate,” referring to fine terrace lines subparallel to anterior margin on frontal area of cranidium.

Materials

Eight paratype specimens, five cranidia and three librigenae (NIGP 172820–172827), uppermost Zitai and Kuniutan formations (Lenodus antivariabilis–Dzikodus tablepointensis conodont zones, lower–middle Darriwilian), Maocaopu, Taoyuan County, Hunan Province; lower Kuniutan Formation (Lenodus variabilis Conodont Zone, lower Darriwilian), Daping, Yichang City, Hubei Province.

Remarks

Although pygidium of this new species is still unknown, it is obviously different from other Panderia species currently known according to its cephalic characters. Among Panderia species reported so far, only three have totally effaced axial furrows on cranidium, i.e., Panderia? lubrica, Panderia dayongensis, and Panderia striolatus n. sp., but axial furrows (or posterior sections of axial furrows) of other species are obvious (see Baltoscandia species in Bruton, Reference Bruton1968). Panderia dayongensis (Ji, Reference Ji1987, p. 248, pl. 1, figs. 1–3; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Yin and Zhou2014b, p. 50, fig. 23H–P) is different from Panderia striolatus in having a smooth cranidium with marginal rim and larger palpebral lobe (about 60% of the cranidial length rather than 46–50% in new species). Panderia striolatus may be closer to Panderia? lubrica Z.Y. Zhou et al. (2016, p. 297, fig. 4G–Y) in lacking marginal rim and axial furrows on cranidium, but the latter has strongly convergent forward anterior branches of facial sutures, a slightly shorter (exsag.) posterior area of fixigena, and a pair of larger palpebral lobes (about 54–63% of cranidial length rather than 46–50%). In addition, Panderia migratoria (figured by Fortey, Reference Fortey1997, p. 431, pl. 7, figs. 7–14) from the lower part of the Pa Kae Formation (Sandbian) of southern Thailand shows a pair of the faint axial furrows, a broader (tr.) librigena, a shorter (sag.), and smooth cranidium, all of which are easily distinguished from Panderia striolatus.

Order Asaphida Salter, Reference Salter1864

Superfamily Asaphoidea Burmeister, Reference Burmeister1843

Family Asaphidae Burmeister, Reference Burmeister1843

Subfamily Nobiliasaphinae Balashova, Reference Balashova1971

Genus Yanpingia new genus

Type species

Yanpingia punctata n. sp., uppermost Meitan Formation (lower Darriwilian), Yanping, Meitan County, Guizhou Province.

Species questionably assigned

Lycophron titan Smith and Laurie (Reference Smith and Laurie2021, p. 9, fig. 5B, C, F, I, non 5A, D, E, G, H, J–M), from the middle Darriwilian of the Amadeus Basin, central Australia.

Diagnosis

As for the type species.

Etymology

From Yanping, a small village of Huangjiaba town, Meitan County, northern Guizhou Province, where the type specimens were collected.

Remarks

Hypostome of this new genus shows forked outline, broadly rounded median notch, oval median body, well-defined maculae, and effaced posterior border furrow (Fig. 7.6), all of which are consistent with the definition of “nobiliasaphine” type revised by Turvey (Reference Turvey2007, p. 354–355), so we consider that it should belong to Nobiliasaphinae Balashova, Reference Balashova1971.

Figure 7. Yanpingia punctata n. gen. n. sp. from the uppermost Meitan Formation (lower Darriwilian), Yanping section, northern Guizhou Province. (1) Dorsal view of cranidium, holotype NIGP 172879. (2) Dorsal view of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172880. (3) Dorsal view of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172881. (4) Dorsal view of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172882. (5) Dorsal view of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172883. (6) Dorsal view of hypostome, paratype NIGP 172884. (7) Dorsal view of librigena, paratype NIGP 172885. (8) Dorsal view of librigena, paratype NIGP 172886. (9) Dorsal view of pygidium, paratype NIGP 172887. (10, 11) Dorsal view of pygidium and close-up of axis, paratype NIGP 172888. (12) Dorsal view of pygidium, paratype NIGP 172889. Scale bars = 1 mm.

Yanpingia n. gen. established here is similar to Basilicus Salter, Reference Salter1849 on the morphology. However, the new genus is different from the latter in characters of the facial suture, with anterior branches converging on the dorsal surface in front of the glabella rather than divergent and crossing the anterior cephalic margin as in Basilicus (Ghobadi Pour et al., Reference Ghobadi Pour and Turvey2009). Compared with Basilicus (Basilicus) (Fortey, Reference Fortey1980b, p. 257, fig. 3d) and Basilicus (Basiliella) Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1934 (DeMott, Reference DeMott, Sloan, Shaw and Tripp1987), the cranidial anterior border of the new genus is narrower (tr.) and pointed forward, and the axial rings and pleural furrows of the pygidium are faint. Although Basilicus (Parabasilicus) Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1934 also has faint axial rings and pleural furrows on the pygidium (see type species Basilicus (Parabasilicus) typicalis Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1934, p. 475, pl. 39, fig.1), it differs from Yanpingia in having a broad and rounded anterior margin of cranidium and a slightly convex pygidial axis. Several forms previously referred to Basilicus (Parabasilicus), i.e., Basilicus (Parabasilicus) brumbyensis Jakobsen et al. (Reference Jakobsen, Nielsen, Harper and Brock2013, p. 15, fig. 13B–K) and Basilicus (Parabasilicus) sp. Zhou and Fortey (Reference Zhou and Fortey1986, p. 183, pl. 5, figs. 17, 19, 22, pl. 6, figs. 1–6), have a pointed forward cranidial anterior border like that of Yanpingia, but they are different from the new genus in having effaced furrows on glabella, smooth cranidium, and hypostome.

Damiraspis Ghobadi Pour et al., Reference Ghobadi Pour and Turvey2009 (see type species Damiraspis margiana Ghobadi Pour et al., Reference Ghobadi Pour and Turvey2009, p. 341, figs. 6K, L, 8D–F, 9G, H, K, M, 10A–J) of the Kypchak Limestone (upper Darriwilian) of central Kazakhstan differs from Yanpingia in having a smooth cranidium, a broader (tr.) anterior border, a transverse preglabellar furrow, a longer (sag.) median body of hypostome, and a non-effaced pygidium.

The new genus is distinct from Ningkianites Lu, Reference Lu1975, type species Ningkianites insculpta (Endo, Reference Endo1932, p. 111, pl. 39, figs. 18–20; Lu in Lu et al., Reference Lu, Zhang, Zhu, Chien and Xiang1965, p. 499, pl. 100, fig. 16; Chang and Jell, Reference Chang and Jell1983, p. 203, fig. 5F, G; Turvey, Reference Turvey2007, p. 368, pl. 5, figs. 1, 2, 4–10) and differs in having a cranidial surface that is densely covered with fine pits, rapidly tapering forward anterior branches of facial sutures, two pairs of glabellar furrows with prominent S1, and an effaced pygidium that is defined by faint border furrow.

In addition, it is like the endemic genus Liomegalaspides Lu, Reference Lu1975 from South China, Tarim, and Annamia (Lu, Reference Lu1975; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Dean, Yuan and Zhou1998a, Reference Zhou, Dean and Luob; Turvey, Reference Turvey2007), but the new form has remarkable S1, preglabellar and axial furrows, an arched posteriorly occipital ring, a cranidial surface that is densely covered with fine pits, a strongly convex pygidial axis, and a weakly defined pygidial border.

Yanpingia punctata new species

Figure 7

Holotype

NIGP 172879 (Fig. 7.1), cranidium, uppermost Meitan Formation (Lenodus variabilis Conodont Zone, lower Darriwilian), Yanping, Meitan County, Guizhou Province.

Diagnosis

Anterior border of cranidium is narrow (sag. and tr.), concave, and pointed forward. Preglabellar field is absent. Elongated glabella contracts at anterior part of the mid-length, having an obvious median ridge and two pairs of glabellar furrows. Occipital ring is arched posteriorly. Anterior branches of facial sutures are divergent forward, curving inward at a rounded angle, then tapering rapidly forward and meeting at a pointed angle. Surface of cranidium is densely covered with fine pits. Pygidium is subtriangular in outline with a strongly convex axis extending backward to border furrow. Axial rings and pleural furrows are faint. Pygidial border is weakly defined by border furrow.

Description

Cranidium is gently convex, with concave anterior border, and the width (tr.) of frontal area is about 64–70% of cranidial length (sag.). Preglabellar field is absent, and anterior border is about 13–15% of cranidial length at the sagittal line. Elongated glabella is slightly convex, rounded anteriorly, defined by deep preglabellar furrow and shallower posteriorly axial furrows, and contracted at anterior part of the mid-length, about 61–65% as wide as long, with an obvious median ridge. A prominent median tubercle is almost adjacent to occipital furrow. There are two pairs of glabellar furrows; S1 extends and deepens backward and inward at the level of contraction of glabella, then disappears at one-third of the length (sag.) of glabella; S2 is shallow, running forward from axial furrows level with anterior extremity of palpebral lobe. Occipital ring is arched posteriorly, weakly separated from glabella by a very shallow and fading adaxially occipital furrow, and its width (sag.) is about 10% of glabellar length (sag.). Palpebral lobe is medium sized and semicircular, occupying about 28–30% of cranidial length (sag.). Anterior branches of facial sutures are divergent forward, curving inward at a rounded angle, then tapering rapidly forward and meeting at a pointed angle; posterior branches extend posterolaterally. Posterior area of fixigena is long (exsag.), narrowing adaxially. Librigena is broad (tr.) and gently convex, with genal spine directed rearward and slightly outward. Lateral border of librigena is concave, narrowing gradually backward, with terrace lines parallel to margin. Eye is raised above the level of librigena.

Hypostome is forked, with a broadly rounded median notch, about 83% as wide as long. Median body is oval in outline, convex (tr.), and defined by deep and broad lateral border furrows. Middle furrow becomes shallower adaxially with a pair of oval maculae. Posterior border furrow is absent. Lateral border widens posteriorly; posterior border is forked and broadly based, bluntly pointed at rear end. Anterior wing is small and triangular.

Pygidium is strongly convex and subtriangular in outline, about 63–68% as long as wide. Axis is strongly convex, slowly tapering backward to border furrow, and defined by deep axial furrows, occupying about 84–88% of pygidial length and 30–32% of the maximum pygidial width. About 12 axial rings and a rounded terminal piece are separated by faint axial ring furrows. Pleural field is strongly convex and inclining laterally, with a deep anterior pair of pleural furrows, and separated by faint pleural furrows, having nine pairs of pleural segments at least that extend to border furrow. Pygidial border is broad (tr.), narrowing slightly posteriorly, and weakly defined by border furrow.

Surface of cranidium is densely covered with fine pits. Fine concentric lines occur around the front end of median body of hypostome. Pygidial border shows transverse and faint lines.

Etymology

From Latin punctata, meaning “punctate,” referring to surface of cranidium densely covered with fine pits.

Materials

Ten paratype specimens, four cranidia, one hypostome, two librigenae, and three pygidia (NIGP 172880–172889), uppermost Meitan Formation (Lenodus variabilis Conodont Zone, lower Darriwilian), Yanping, Meitan County, Guizhou Province.

Remarks

Recently, Smith and Laurie (Reference Smith and Laurie2021) established a new species, Lycophron titan, from Stairway Sandstone (Dw2) of the Amadeus Basin, central Australia, on the basis of four specimens (fig. 5A–M) collected from three different sections. However, one of the cranidia (fig. 5B, C, F, I) shows almost identical morphology to Yanpingia punctata n. sp., bearing an anterior border with obtuse angle rather than a tongue-like anterior border like Lycophron species (Fortey and Shergold, Reference Fortey and Shergold1984; Laurie, Reference Laurie2006). The specimen is incomplete and absent an associated pygidium and hypostome preserved in the same horizon. Hence, it is hard to judge its generic placement and make a detailed comparison.

Superfamily Cyclopygoidea Raymond, Reference Raymond1925

Family Nileidae Angelin, Reference Angelin1854

Genus Nileus Dalman, Reference Dalman1827

Type species

Asaphus (Nileus) armadillo Dalman, Reference Dalman1827, Komstad Limestone Asaphus expansus Trilobite Zone (lower Darriwilian), Husbyfjöl, Östergötland, Sweden; by monotypy.

Nileus yichongqiaoensis new species

Figure 8

- Reference Zhou, Yuan and Zhou2001

Nileus cf. N. depressus schranki Nielsen, Reference Nielsen1995; Zhou et al., p. 75, fig. 3M, N, non O.

Figure 8. Nileus yichongqiaoensis n. sp. from the Kuniutan Formation (middle Darriwilian), Yichongqiao section, northwestern Hunan Province. (1, 2) Dorsal and lateral views of cephalon, holotype NIGP 131799. (3) Dorsal view of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172933; the Kuniutan Formation (lower–middle Darriwilian), Maocaopu section, northwestern Hunan Province. (4) Dorsal view of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172934. (5) Dorsal view of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172935. (6) Dorsal view of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172936. (7) Dorsal view of librigena, paratype NIGP 172937. (8) Dorsal view of pygidium, paratype NIGP 172938. (9) Dorsal view of pygidium, paratype NIGP 172939. (10) Dorsal view of pygidium, paratype NIGP 172940. (11) Dorsal view of pygidium, paratype NIGP 172941. Scale bars = 2 mm.

Holotype

NIGP 131799 (Fig. 8.1, 8.2), one cephalon refigured from Zhou et al. (2001, fig. 3M, N), Kuniutan Formation (Yangtzeplacognathus crassus–Dzikodus tablepointensis conodont zones, middle Darriwilian), Yichongqiao, Cili County, Hunan Province.

Diagnosis

A species of Nileus with an elongated glabella, a pair of long palpebral lobes, and strongly divergent outward anterior branches of facial sutures. Librigena becomes narrower rapidly forward. Pygidium is transversely oval in outline, defined by a broad and concave border furrow.

Occurrence

Lower to middle Darriwilian strata in South China (Hunan Province).

Description

Cephalon is semielliptical in outline, gently convex (tr.), sloping downward anteriorly and laterally. The sagittal length of the cephalon is equal to 74% of the maximum width (tr.) along its posterior margin. Cranidium is slightly arched anteriorly, and its length (sag.) is about 91–97% of the maximum width between palpebral lobes. Glabella is elongated, the width of which between palpebral lobes is about 65–74% of glabellar length (sag.), and it is defined by shallow axial furrows that are subparallel or slightly divergent posteriorly. Median tubercle is small, situated at one-third of glabellar sagittal length from posterior margin. Width (tr.) of fixigena is about 23–30% of glabellar width between palpebral lobes. Palpebral lobe is long (exsag.), crescentic, occupying 44–51% of cranidial length (sag.). Posterior area of fixigena is short (exsag.) and triangular; its length (exsag.) occupies about 9–12% of cranidial length (sag.). Anterior branches of facial sutures strongly diverge outward, then curve inward to meet anterior margin; posterior branches are short and divergent posterolaterally. Librigena is rounded posterolaterally, narrowing rapidly forward. Genal field is gently convex, sloping downward posterolaterally; lateral border bears a narrow (tr.) rim. Eye is large and crescentic; eye socle is upturned, separated from genal field by an obvious furrow.

Pygidium is transversely oval in outline, gently convex (tr.); the sagittal length is equal to 56–62% of the maximum width (tr.), which is situated at 38–43% of pygidial length (sag.) from anterior to posterior margin. Axis is conical, gently convex, poorly defined by faint axial furrows, occupying about 29–34% of the maximum pygidial width (tr.) and 56–65% of pygidial length (sag.), with five rings. Pygidial border is defined by a broad and concave border furrow, about 17–22% of sagittal length of pygidium. Surface of pygidial sides is covered with approximately transverse terrace lines, which are also present on pygidial border of a few specimens.

Etymology

From Yichongqiao, a small village of Cili County, northwestern Hunan Province, where the type specimens were collected.

Materials

Nine paratype specimens, four cranidia, one librigenae, and four pygidia (NIGP 172933–172941), Kuniutan Formation (Yangtzeplacognathus crassus–Dzikodus tablepointensis conodont zones, middle Darriwilian), Yichongqiao, Cili County, Hunan Province; Kuniutan Formation (Lenodus variabilis–Dzikodus tablepointensis conodont zones, lower–middle Darriwilian), Maocaopu, Taoyuan County, Hunan Province.

Remarks

The holotype of the new species (Fig. 8.1, 8.2) from the Kuniutan Formation (middle Darriwilian) of Yichangqiao section was previously identified by Zhou et al. (2001, p. 75, fig. 3M, N) as Nileus cf. N. depressus schranki Nielsen, Reference Nielsen1995; however, we consider that it differs from Nileus depressus schranki (Nielsen, Reference Nielsen1995, p. 265, figs. 192–198) in having an elongated glabella and slightly arched anteriorly cranidium. Furthermore, a pygidium figured by Zhou et al. (2001, p. 75, fig. 3O) as Nileus cf. N. depressus schranki displays transverse terrace lines on pygidial sides that belong to “exarmatus type” (Nielsen, Reference Nielsen1995, p. 197), but the pygidium of Nileus depressus schranki is entirely covered with dense and transverse terrace lines that should be “depressus type,” so this specimen may be much closer that of Nileus armadilloformis Lu, Reference Lu1957 from the same horizon than to Nileus depressus schranki.

Nileus yichongqiaoensis n. sp. is rather similar to Nileus exarmatus Tjernvik (Reference Tjernvik1956, p. 209, pl. 2, figs. 18, 19; Nielsen, Reference Nielsen1995, p. 225, figs. 163–167) from the Floian to Dapingian strata of the Baltica in having an elongated glabella, a long palpebral lobe, strongly divergent outward anterior branches of facial sutures, and a broad and concave pygidial border furrow, but the latter has a broader (tr.) anterior part of librigena and a narrow (sag. and exsag.) border in front of anterior cranidial margin. Compared with Nileus jafari Ghobadi Pour and Turvey (Reference Ghobadi Pour, Popov and Vinogradova2009, p. 477, fig. 7) from the Dapingian to lower Darriwilian strata of central Iran, the new species shows subparallel or slightly divergent posteriorly axial furrows, a pair of longer palpebral lobes, a narrower (tr.) anterior part of the librigena, and a narrower (sag. and exsag.) pygidial border. Nileus yichongqiaoensis differs from Nileus armadilloformis (Lu, Reference Lu1957, p. 282, pl. 152, figs. 3–6) in having an elongated glabella, an anteriorly arched cranidium, a narrower (tr.) anterior part of the librigena, and an obvious border furrow on the pygidium. The pygidium of Nileus walcotti (Endo, Reference Endo1932; see Chang and Jell, Reference Chang and Jell1983, fig. 6a, b; Lu, Reference Lu1975, as Nileus liangshanensis, p. 152, pl. 23, fig. 9) is close to that of the new form in having an obvious border furrow, but the cephalon of Nileus walcotti bears a broadly anteriorly rounded cranidium, a slightly broader (tr.) glabella, a pair of shorter (exsag.) palpebral lobes, and a broader (tr.) anterior part of the librigena.

Order Uncertain

Family Isocolidae Angelin, Reference Angelin1854

Genus Paratiresias Petrunina in Repina et al., Reference Repina, Yaskovich, Aksarina, Petrunina, Poniklenko, Rubanov, Bolgova, Golikov, Hajrullina and Posochova1975

Type species

Paratiresias turkestanicus Petrunina in Repina et al., Reference Repina, Yaskovich, Aksarina, Petrunina, Poniklenko, Rubanov, Bolgova, Golikov, Hajrullina and Posochova1975, Kielanella–Tretaspis beds (Sandbian–lower Katian, according to Z.Q. Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Zhou and Xiang2016, p.65), Uluktau district, Turkistan–Alai Ridge; by original designation.

Other species

Paratiresias peculiaris n. sp., from the middle Darriwilian of South China; Paratiresias sp. indet., from the lower Katian of western Yunnan (Prof. Zhi-Yi Zhou's collection); Paratiresias alborzensis Karim, Reference Karim2008, from the lower–middle Katian of northwestern Iran.

Emended diagnosis

Cranidium is elongated trapezoid in outline with entire anterior border flattened or arched forward. Glabella is slightly convex and expanding forward, well defined by distinct axial and preglabellar furrows. Preglabellar field is extremely narrow (sag. and exsag.) or absent. Fixigena is narrow (tr.), sloping strongly downward. Eye is small and located forward. Posterior border is strongly widening abaxially, merging with posterior part of lateral border to form a short genal spine. Facial sutures are proparian type. Surface of cranidium is smooth or covered with fine lines. Pleural field consists of three pleural ribs; anterior half rib forms a prominent protrusion upward. Pygidial border is convex strongly, tube-like, covered by terrace lines parallel to pygidial margin (emended from Petrunina in Repina et al., Reference Repina, Yaskovich, Aksarina, Petrunina, Poniklenko, Rubanov, Bolgova, Golikov, Hajrullina and Posochova1975, p. 227; Karim, Reference Karim2008, p. 120–121).

Occurrence

Middle Darriwilian to middle Katian strata in Asia (Turkestan and Alai ranges, northwestern Iran, western Yunnan, North China, and South China).

Remarks

Paratiresias was established by Petrunina in Repina et al. (Reference Repina, Yaskovich, Aksarina, Petrunina, Poniklenko, Rubanov, Bolgova, Golikov, Hajrullina and Posochova1975) on the basis of three cranidia poorly preserved (p. 227, pl. 47, figs. 1, 4–7). Then type species Paratiresias turkestanicus was also reported by Zhou and Dean (Reference Zhou and Dean1986, p. 780, pl. 65, figs. 3, 4, 6, 7, 10) from the upper Chedao Formation (lower Katian) of Huanxian area, Gansu Province, to provide additional detail for the cranidium. However, pygidia of Paratiresias were unknown until Paratiresias alborzensis was established by Karim (Reference Karim2008), who described pygidial morphology in detail (p. 120, fig. 7v–y). Since then, the definition of this genus just becomes complete (see preceding emended diagnosis). Unfortunately, although librigenae of Paratiresias alborzensis have been collected by Karim (Reference Karim2008, p. 120), there were neither description nor figures in the paper. Cranidia described in the following provide some new morphological information for Paratiresias, i.e., extremely narrow (sag. and exsag.) preglabellar field, flattened anterior border, and smooth surface.

Whittington (Reference Whittington1956) discussed in detail three genera of Isocolidae and considered that members of this family have opisthoparian facial sutures; however, several species of Paratiresias show proparian type (Zhou and Dean, Reference Zhou and Dean1986, p. 779, pl. 65, fig. 4; Karim, Reference Karim2008, p. 119, fig. 7i, k; Fig. 9.3, 9.6); their posterior branches of facial sutures extend posteriorly to cut the lateral margin.

Figure 9. Paratiresias peculiaris n. sp. from the Kuniutan Formation (middle Darriwilian), Maocaopu section, northwestern Hunan Province. (1–3) Dorsal, anterior, and lateral views of cranidium, holotype NIGP 172966. (4) Dorsal view of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172967. (5, 6) Dorsal and lateral views of cranidium, paratype NIGP 131802. (7, 8) Dorsal and anterior views of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172968. (9, 10) Dorsal and lateral views of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172969. (11, 12) Dorsal and anterior views of cranidium, paratype NIGP 172970. Scale bars = 1 mm.

Paratiresias is most similar to Holdenia Cooper, Reference Cooper1953 (=Tiresias M'Coy, Reference M'Coy1846 =Hanzhongaspis Chen in Lee et al., Reference Lee, Song, Zhou and Yang1975; see Dean, Reference Dean1962, p. 342; Ji, Reference Ji1986, p. 24; Zhou and Dean, Reference Zhou and Dean1986, p. 780) within the family Isocolidae, but it differs from the latter in that the fixigena is narrower (tr.), the anterior cephalic border is prominent and well defined by a deep anterior border furrow, the preglabellar field is narrower or absent at the sagittal line, pygidial axial rings and pleural ribs are clearer, anterior half rib forms a prominent protrusion upward, and the pygidial border is tube-like and strongly convex.

Paratiresias peculiaris new species

Figure 9

- Reference Zhou, Yuan and Zhou2001

Paratiresias sp. Zhou et al., p. 74, fig. 3K.

Holotype

NIGP 172966 (Fig. 9.1–9.3), one cranidium, Kuniutan Formation (Dzikodus tablepointensis Conodont Zone, middle Darriwilian), Maocaopu, Taoyuan County, Hunan Province.

Diagnosis

A species of Paratiresias with an extremely narrow (sag. and exsag.) preglabellar field. No muscle impressions occur on the glabellar. Anterior border is low and flat, becoming narrower (exsag.) abaxially. Surface of cranidium is smooth.

Occurrence

Middle Darriwilian strata in South China (Hunan Province).

Description

Cranidium is trapezoid in outline, broadly rounded anteriorly, and its length (sag.) is about 86–90% of the maximum width (tr.) along the posterior margin. Preoccipital glabella is strongly convex, subrectangle in profile, broadly rounded anteriorly, gently expanded forward, strongly sloping downward anteriorly and laterally, and attaining its maximum width at two-thirds to three-fourths length from the occipital furrow, where the width is about 70–73% of the length. Glabellar furrows and muscle impressions are not present on the glabella. Axial furrows are wide and deep. Occipital ring with a tiny median tubercle has the sagittal length (sag.) about 15–18% that of preoccipital glabella and shortens (exsag.) and curves forward abaxially. Occipital furrow is deeply incised. Preglabellar field is gently convex, inclining downward anteriorly, becoming narrower (sag. and exsag.) adaxially and even absent at the sagittal mid-length. Anterior border is low and flat, becoming narrower (exsag.) abaxially, defined by deep and narrow (sag. and exsag.) anterior border furrow. Its length (sag.) at the sagittal mid-length is equal to 7–11% of cranidial length. Fixigena is convex, strongly inclining downward anteriorly and laterally, becoming gradually narrower (tr.) anteriorly. Eye is very small and approximately level with the maximum width of the glabella. Anterior branches of facial sutures are very short, slightly divergent forward; posterior branches are long, extending posteriorly across the posterior part of the lateral border to cut the lateral margin. Lateral border furrow is connected with the deep and narrow (exsag.) posterior border furrow at a rounded angle, forming a triangular depression posterolaterally. Posterior border widens (exsag.) laterally and extends posterolaterally, merging with the posterior part of the lateral border to form a short genal spine directed rearward. Surface of cranidium is smooth.

Etymology

From peculiaris, meaning “peculiar,” referring to a species of Paratiresias with an extremely narrow (sag. and exsag.) preglabellar field.

Materials

Five paratype cranidial specimens (NIGP 131802, 172967–172970), Kuniutan Formation (Dzikodus tablepointensis Conodont Zone, middle Darriwilian), Maocaopu, Taoyuan County, Hunan Province.

Remarks

Paratiresias peculiaris n. sp. described here is the oldest known species of the genus, showing an extremely narrow (sag. and exsag.) preglabellar field that is totally absent on the Late Ordovician species. This evolutionary trend corresponds to that of Phorocephala Lu in Lu et al., Reference Lu, Zhang, Zhu, Chien and Xiang1965 of Telephinidae (Zhou and Dean, Reference Zhou and Dean1986, p. 750–751), indicating that it may be the reflection of ontogeny recapitulating phylogeny like Phorocephala (Chatterton, Reference Chatterton1980, p. 29–32).

Compared with type species Paratiresias turkestanicus (Petrunina in Repina et al., Reference Repina, Yaskovich, Aksarina, Petrunina, Poniklenko, Rubanov, Bolgova, Golikov, Hajrullina and Posochova1975, p. 227, pl. 47, figs. 1, 4–7; Zhou and Dean, Reference Zhou and Dean1986, p. 780, pl. 65, figs. 3, 4, 6, 7, 10), Paratiresias peculiaris has a more elongated glabella without muscle impressions, smooth cranidium, and extremely narrow (sag. and exsag.) preglabellar field rather than it being totally absent as in other Paratiresias species. The new species is very similar to Paratiresias alborzensis (Karim, Reference Karim2008, p. 120, fig. 7i–y) from the lower–middle Katian strata of northwestern Iran in having an elongated glabella without muscle impressions, but the latter has a strongly anteriorly arched anterior border, surface of cranidium that is ornamented with fine terrace lines, and no preglabellar field. In addition, the anterior border of Paratiresias peculiaris is low, flat, and narrower (exsag.) abaxially; however, those of Paratiresias turkestanicus and Paratiresias alborzensis show gently convex and even width (sag. and exsag.).

Acknowledgments

This paper is a contribution to the IGCP 735 project “Rocks and the Rise of Ordovician Life.” The research has been financially supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB 26000000), the National Science Foundation of China (41672008, 41972011, 41972015, 42072005, and 42072007), and the State Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy (Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, CAS) (213123). We thank G.X. Wang, L.X. Li, X.C. Luan, Y.C. Zhang, and G.Z. Yan from the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (NIGPAS) for their help in the field. Special thanks are due to the editors, H. Parnäste, and another anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments and suggestions that substantially improved the manuscript both academically and linguistically.