Introduction

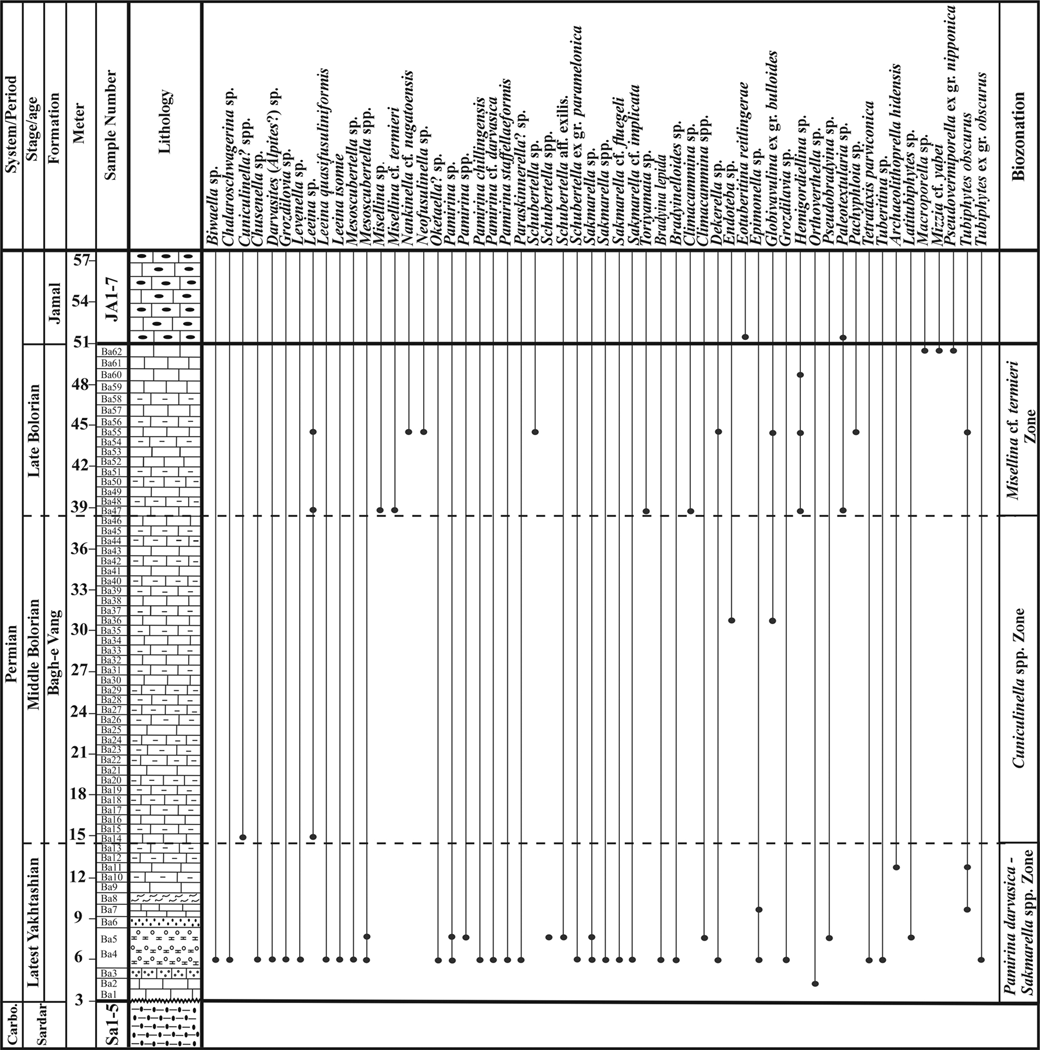

In east-central Iran, the Jamal Formation is underlain by the Carboniferous–lower Permian shales and sandstones of the Sardar Formation (e.g., Leven and Taheri, Reference Leven and Taheri2003) and is composed, from base to top, of gray medium-bedded, sandy bioclastic grainstone, gray thick-bedded calcareous conglomerate, red marl and alternating calcareous shale, and gray to dark gray, medium- to thin-bedded bioclastic wackestone to packstone. Outcrops of the Jamal Formation in the Shirgesht area, north of the town of Tabas, were first studied by Ruttner et al. (Reference Ruttner, Nabavi and Hajian1968), who assigned a late Permian age. They are composed mainly of limestone and dolomitic limestone, with chert nodules, containing small foraminifers, fusulinids, calcareous algae, bryozoans, brachiopods, crinoids, and corals. The basal part of the Jamal Formation has well-exposed outcrops on the western side of Bagh-e Vang Mountain and on the northwestern side of Shesh Angosht Mountain (Fig. 1) and is named the Bagh-e Vang Formation (Partoazar, Reference Partoazar1995). The basal part of the Jamal Formation was named the Bagh-e Vang Member by Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam (Reference Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam2004) in the Shirgesht area (eastern Iran), but later was considered as a formation at the base of the Shirgest Group (Leven et al., Reference Leven, Davydov and Gorgij2006). It includes calcareous algae, smaller foraminifers, fusulinids, corals, bryozoans, brachiopods, crinoids, ostracodes, and ammonoids (Fig. 2). The boundary between the Bagh-e Vang and Sardar formations is a disconformity, and there are some additional discontunities as a result of minor faulting.

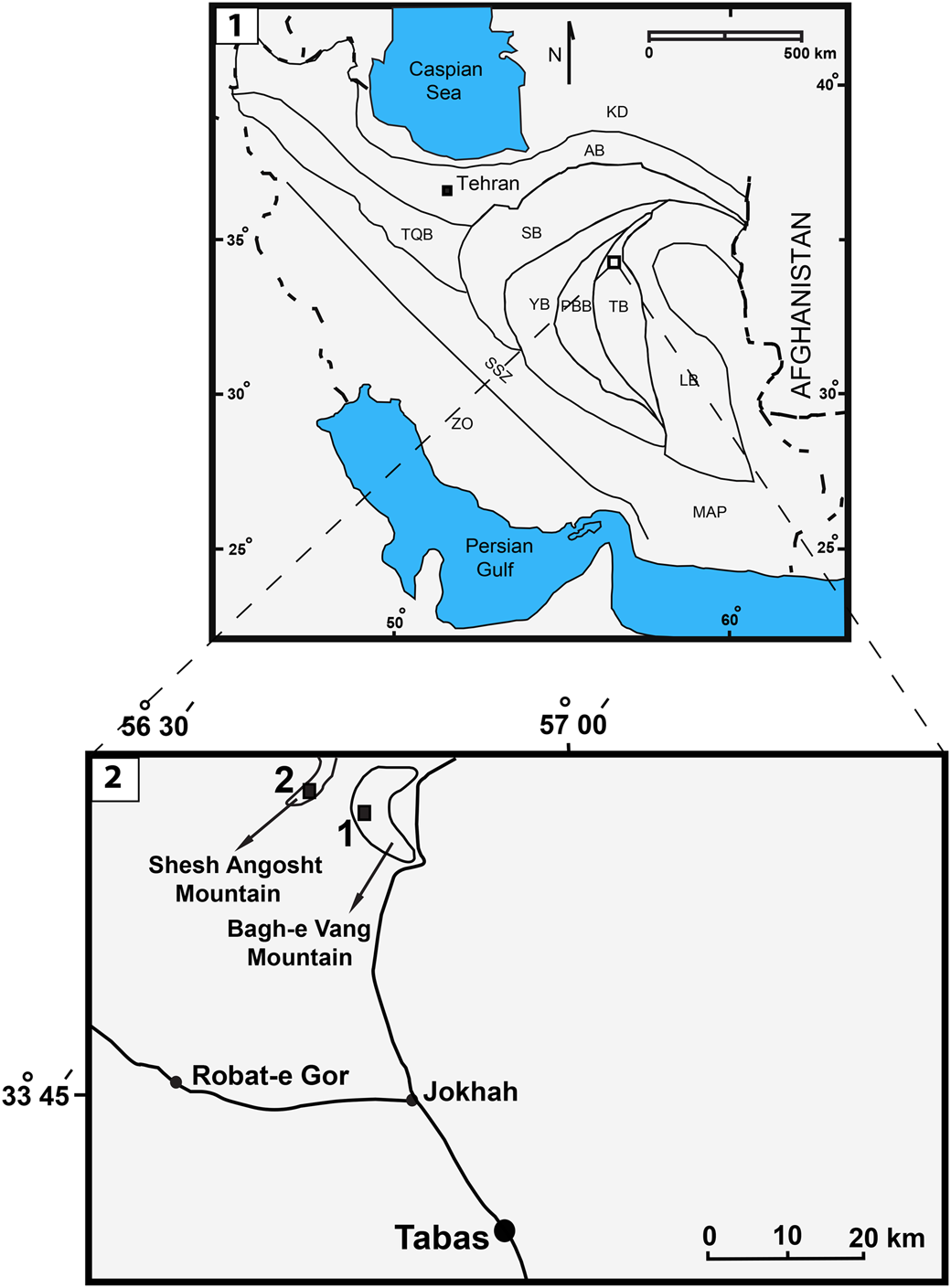

Figure 1. (1) Location map showing the position of studied sections in the east-central Iran, Tabas area. Abbreviations: AB = Alborz Belt; KD = Kopeh Dagh, LB = Lut Block, MAP = Makran accretionary Prism, PBB = Posht-e-Badam Block, SB = Sabzevar Block, SSZ = Sanandaj-Sirjan Zone, TB = Tabas Block, TQB = Tabriz-Qom Block, YB = Yazad Block, ZO = Zagros Orogen. (2) Enlarged map showing the studied sections in the Tabas area, east-central Iran: 1 = Bagh-e Vang section; 2 = Shesh Angosht section.

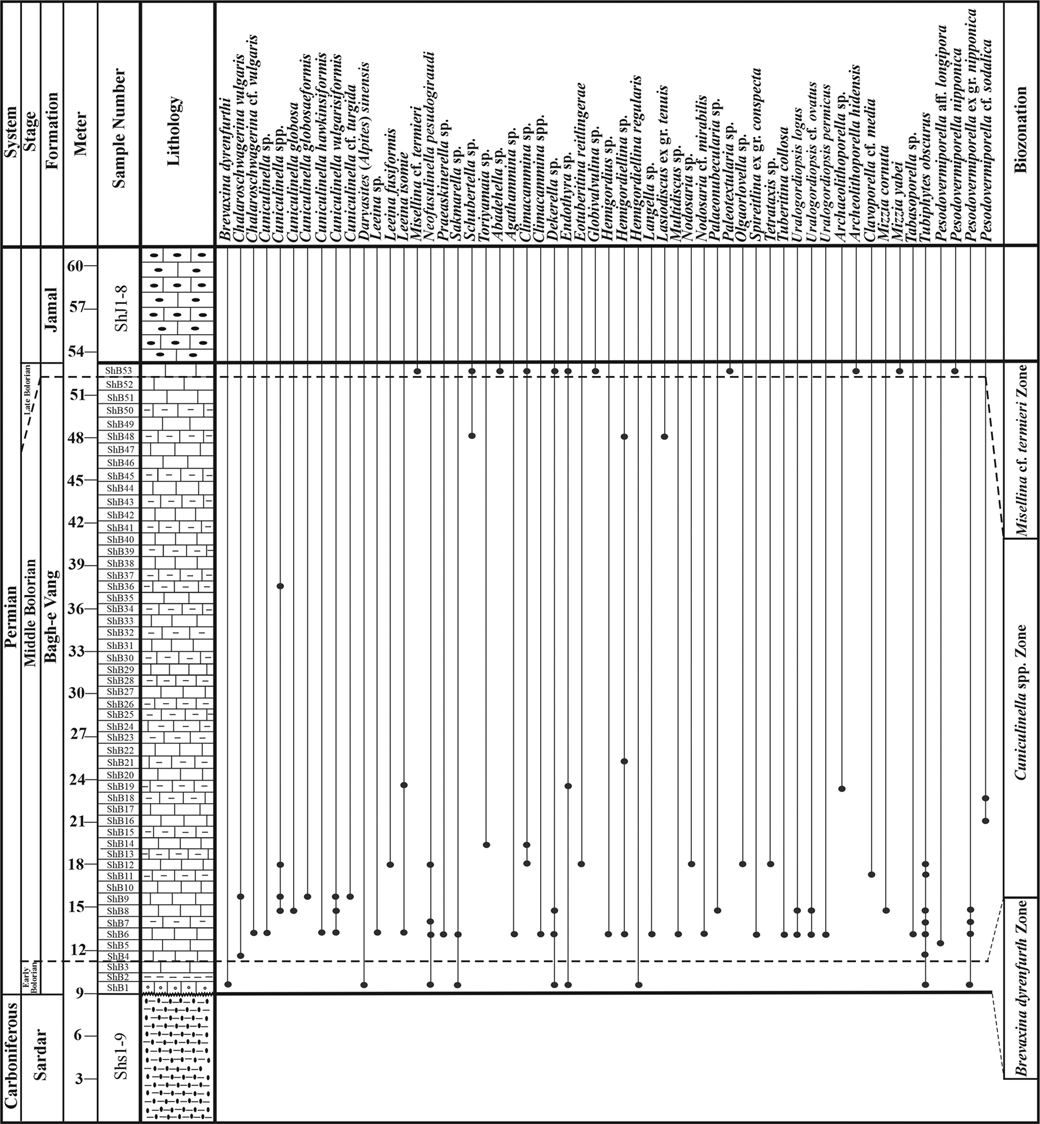

Figure 2. Fusulinid biozonation and faunal distribution of the Bagh-e Vang Formation, Bagh-e Vang section, east-central Iran. Abbreviation: Carbo. = Carboniferous.

Kahler (Reference Kahler1974) examined the fusulinid contents of a few samples collected from the Shesh Angosht section and assigned them to the Misellina Zone of Kungurian age. Partoazar (Reference Partoazar1995) considered the Bagh-e Vang Formation in the type section as Asselian–Sakmarian in age based on its fusulinid content. Later, Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam (Reference Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam2004) re-examined the biostratigraphy of the Bagh-e Vang Formation using fusulinids and identified several fusulinid biozones, in ascending order, including Pamirina-Mesoschubertella, Misellina-Chalaroschwagerina-Paraleeina, and Misellina-Armenina, ranging in age from upper Cisuralian to possibly lower Guadalupian (i.e., lower–middle Permian boundary interval). Although most fusulinid assemblages of the Bagh-e Vang Formation in the type section are indicative of the upper Cisuralian, the age of the upper part of this formation remains uncertain. Therefore, it is necessary to check the precise age of the Bagh-e Vang Formation in the Shesh Angosht section, which has not been examined using high-resolution biostratigraphy.

Here, we examine lithological and faunal changes within the Bagh-e Vang Formation at two stratigraphic sections in the Bagh-e Vang and Shesh Angosht mountains. The Bagh-e Vang section is located 54 km north of Tabas and the Shesh Angosht section is 4 km northwest of the Bagh-e Vang section. Unlike at the Bagh-e Vang section, the basal part of the Bagh-e Vang Formation at Shesh Angosht does not contain sandy bioclastic grainstone, calcareous conglomerate, and red marls. It is instead composed of alternating bioclastic wackestone and/or packstone with calcareous shales and lies conformably on greenish shales and sandstones of the Sardar Formation (Fig. 2). The purpose of this research is to: (1) identify the foraminiferal fauna and calcareous algae flora of the Bagh-e Vang Formation in both sections, (2) describe their biozones and stratigraphic distribution, and (3) discuss the paleobiogeographic affinity of their fusulinid faunas.

Geological setting

The area under study is situated in the Tabas Block (Fig. 1). The Tabas Block is bounded to the west by the Kalmard fault and to the east by the Nayband fault, which are both strike-slip faults (Alavi, Reference Alavi1991). The Tabas Block, together with the Posht-e Badam, Yazd, and Lut blocks, forms the Central Iranian Midcontinent. Ruttner et al. (Reference Ruttner, Nabavi and Hajian1968) reported more than 8 km of Paleozoic deposits in this block; these outcrops represent the most complete Paleozoic section of the Central Iran Midcontinent and include Upper Devonian and upper Carboniferous deposits that are missing in most parts of Iran. The Permian stratigraphic sections in the Shirgesht area include deposits that span the early Permian, with early part of the early Permian in the Zaladu section and the later part of the early Permian in the Bagh-e Vang and Shesh Angosht sections. There are also some outcrops of mid- and late Permian carbonates in the Tabas Block, both in the type section of the Jamal Formation and elsewhere. Therefore, the study of this block is particularly significant in terms of paleobiogeographic and tectonic reconstructions of Iran during the late Paleozoic.

Biostratigraphy

In this study, the series are subdivided into four biozones, which are: (1) Pamirina darvasica and Sakmarella spp. Zone, upper Yakhtashian; (2) Misellina (Brevaxina) dyrhenfurthi Zone, lower Bolorian; (3) Cuniculinella spp. Zone, mid-Bolorian); and (4) Misellina (Misellina) cf. M. (M.) termieri Zone, upper Bolorian (Fig. 2). The photomicrographs of the identified fusulinids, smaller foraminifer, microproblematica, and algae of this study are provided in Figures 3–7 for the Bagh-e Vang section and Figures 9–14 for the Shesh Angosht section.

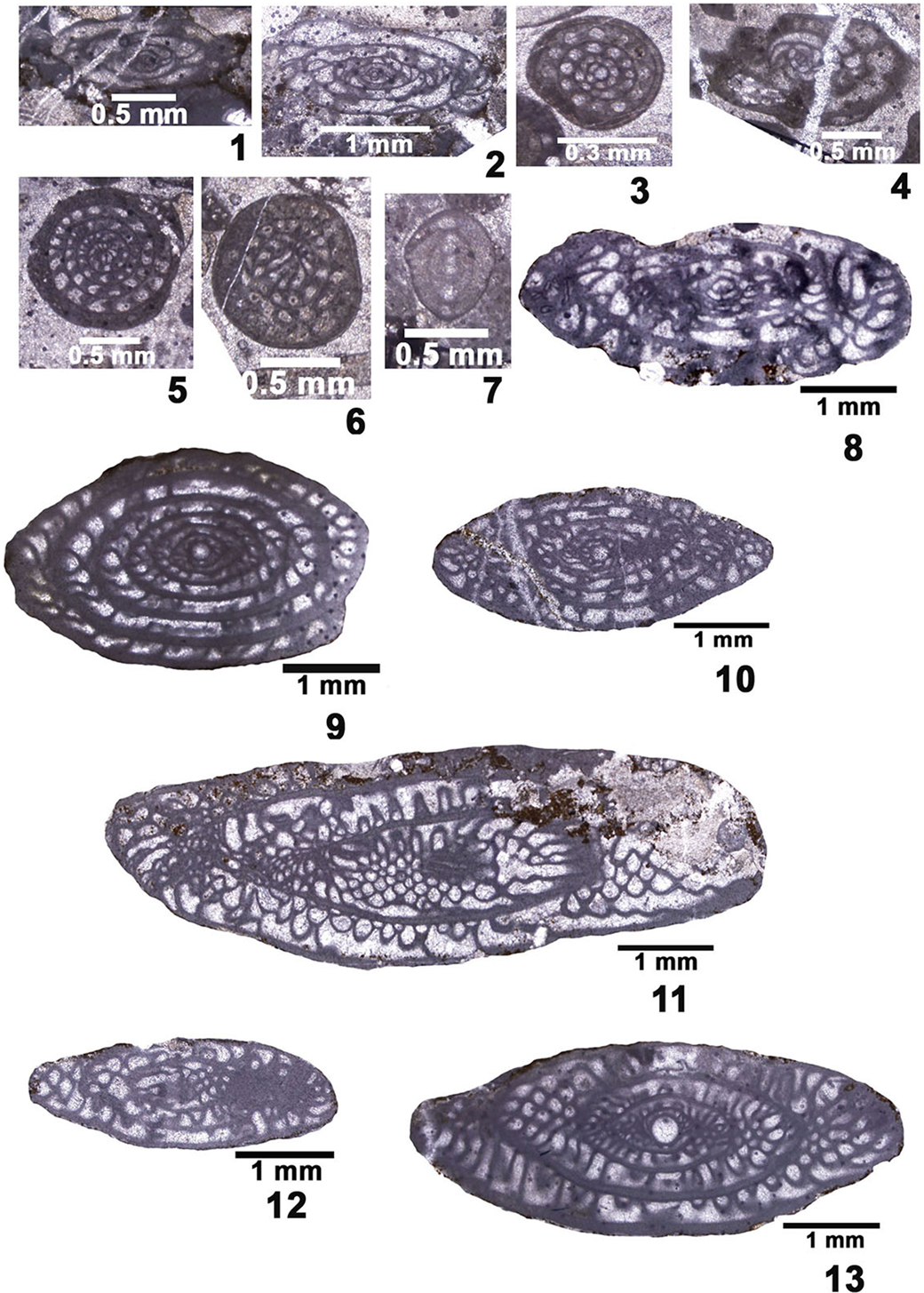

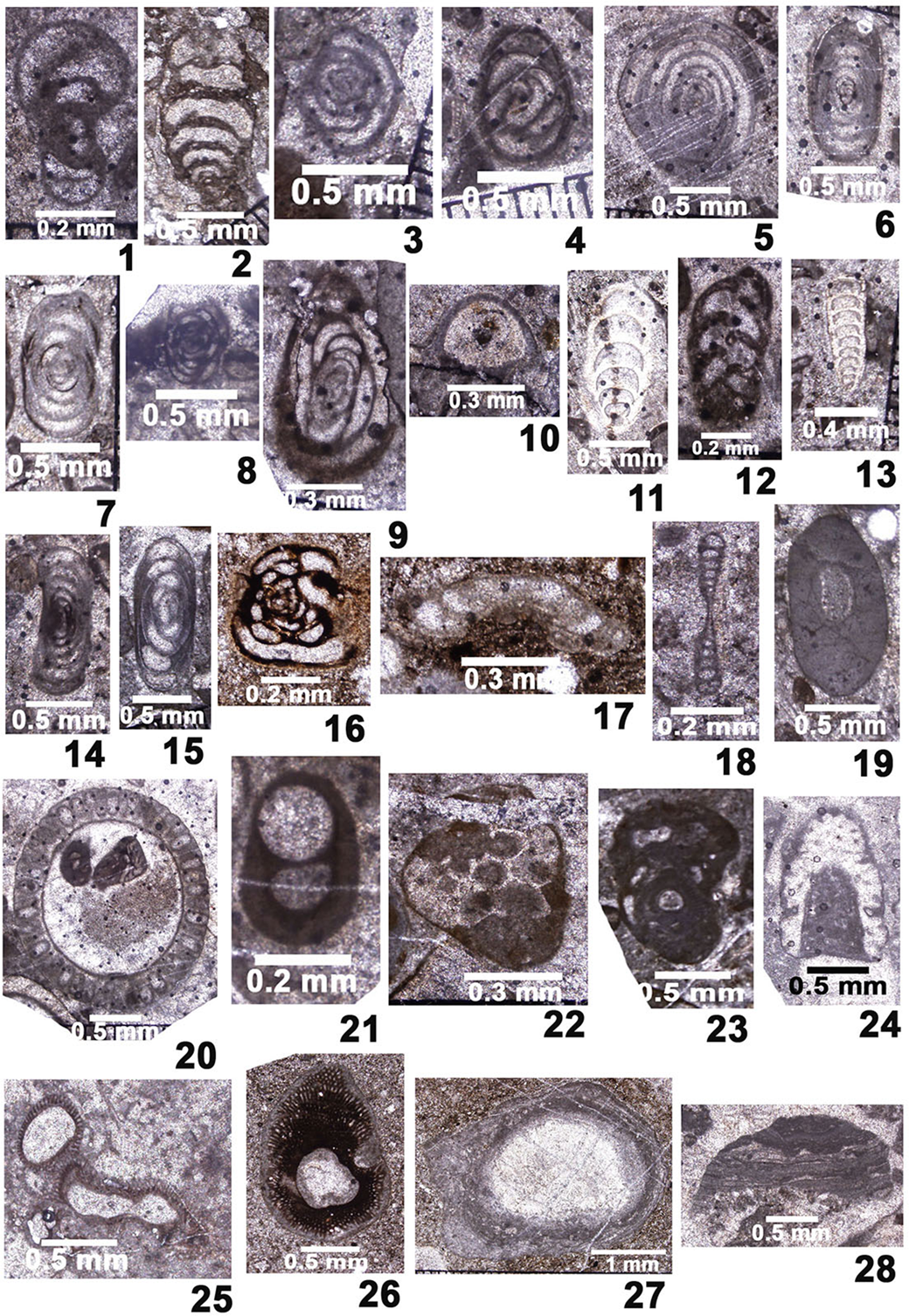

Figure 3. Lower Permian small foraminiferans and calcareous algae from the Bagh-e Vang Formation, Bagh-e Vang section, in east-central Iran. (1, 2) Tetrataxis parviconica Lee and Chen in Lee, Chen, and Chu, Reference Lee, Chen and Chu1930, (1) axial section, BA-4-5-2, ALU-902, (2) subaxial section, BA-4-30-3, ALU-903; (3–6) Bradyina ex gr. B. lepida Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1950, (3) subaxial section, BA-4-16-2, ALU-909, (4) axial section, BA-4-26-1, ALU-910, (5) subaxial section, BA-4-31-1, ALU-911, (6) oblique subaxial section, BA-4-49-2, ALU-912; (7, 8) Deckerella sp., (7) subaxial section, BA-4-24-4-1, ALU-913, (8) oblique section, BA-4-54-2, ALU-914; (9) Bradyina sp. 2, axial section, BA-4-49-1, ALU-916; (10) Bradyina sp. 3, transverse section, BA-5-2-3, ALU-917; (11) Endoteba sp., axial section, BA-36-4, ALU-944; (12, 13) Climacammina spp., four subaxial sections, (12) BA-5-14-1, ALU-919, (13) BA-5-19-4, ALU-920; (14, 15) Globivalvulina ex gr. G. bulloides (Brady, Reference Brady1876), (14) transverse section, BA-36-2, ALU-942, (15) transverse section, BA-55-14-2, ALU-943; (16–18) Hemigordiellina sp., three random sections, (16) BA-47-10-2, ALU-945, (17) BA-47-12-1, ALU-946, (18) BA-47-12-3, ALU-947; (19) Palaeotextularia sp., subaxial section, BA-47-11-1, ALU-954; (20) Pachyphloia sp., axial section, BA-55-13-2, ALU-956; (21, 22). Orthovertella sp., (21) subaxial section, BA-3-1, ALU-958, (22) subaxial section, BA-3-3, ALU-959; (23) Agathammina sp., subaxial section, BA-47-15-1, ALU-960; (24, 25) Epimonella sp., two longitudinal sections, (24) BA-4-9-3, ALU-969, (25) BA-7-6, ALU-970; (26) Archaeolithoporella hidensis Endo, Reference Endo1961, transverse section of an oncoidal grain of tebagite type, BA-11-6, ALU-996; (27) Tubiphytes obscurus Maslov, Reference Maslov1956, transverse section, BA-55-4-1, ALU-993; (28) Mizzia cf. M. yabei (Karpinsky, Reference Karpinsky1909) emend. Pia, Reference Pia1920, transverse section, BA-62-2, ALU-1003; (29) Macroporella sp., subaxial section, BA-62-3, ALU-1004.

Figure 4. Lower Permian fusulinids and calcareous algae from the Bagh-e Vang Formation, Bagh-e Vang section, in east-central Iran. (1) Permocalculus sp., longitudinal section, BA-62-8, ALU-1010; (2) Pseudovermiporella ex gr. P. nipponica (Endo in Endo and Kanuma, Reference Endo and Kanuma1954), transverse section, BA-62-10, ALU-1012; (3, 4) Levenella sp. transitional to Pamirina sp., (3) oblique section, BA-4-1-3, ALU-1015, (4) transverse section, BA-4-1-4, ALU-1016; (5, 6) Pamirina spp., (5) subtransverse section, BA-4-8-1, ALU-1026, (6) oblique section, BA-4-15-1, ALU-1027; (7–11) Mesoschubertella spp., five different sections, (7) BA-4-4-3, ALU-1017, (8) BA-2-5-1, ALU-1019, (9) BA-4-6-2, ALU-1020, (10) BA-4-15-2, ALU-1022, (11) BA-4-8-4, ALU-1021; (12–15) Pamirina chilingensis (Wang and Sun, Reference Wang and Sun1973), (12) axial section, BA-4-8-2, ALU-1028, (13) subaxial section, BA-4-10-2, ALU-1029, (14) oblique section, BA-4-16, ALU-1030, (15) axial section, BA-4-15-3, ALU-1031; (17) Chusenella? sp., oblique section, BA-4-14-2, ALU-1034; (16, 18–20) Pamirina cf. P. darvasica Leven, Reference Leven1970, (16) subaxial section, BA-4-30-1, ALU-1048, (18) axial section, BA-4-30-8, ALU-1049, (19) oblique section, BA-4-32-1, ALU-1050, (20) oblique section, BA-4-22-1, ALU-1051; (21) Pamirina staffellaeformis Zhou, Sheng, and Wang, Reference Zhou, Sheng and Wang1987, axial section, BA-4-42-2, ALU-1057; (22) Schubertella ex gr. S. paramelonica Suleimanov, Reference Suleimanov1949, axial section, BA-4-53-2, ALU-1062; (23, 24) Pamirina darvasica Leven, Reference Leven1970, (23) axial section, BA-4-56-2, ALU-1063, (24) oblique section, BA-42-57-2, ALU-1064; (25) Latitubiphytes, oblique section, BA-5-5-2, ALU-1067.

Figure 5. Lower Permian fusulinids from the Bagh-e Vang Formation, Bagh-e Vang section, in east-central Iran. (1, 2) Schubertella aff. S. exilis Suleimanov, Reference Suleimanov1949, (1) subaxial section, BA-5-9-3, ALU-1078, (2) axial section, BA-5-12-2, ALU-1079; (3) Misellina (Misellina) sp., BA-47-1-1, ALU-1102; (4) Toriyamaia sp., axial section, BA-47-11-2, ALU-1104; (5, 6) Misellina (Misellina) cf. M. (M.) termieri (Deprat, Reference Deprat1915), (5) transverse section, BA-47-12-4, ALU-1105, (6) oblique subaxial section, BA-47-13-1, ALU-1106; (7) Nankinella cf. N. nagatoensis Toriyama, Reference Toriyama1958, axial section, BA-57-15-1, ALU-1109; (8) Grozdilovia sp., subaxial section, BA-4-2-2, ALU-1110; (9) Darvasites (Alpites?) sp., oblique section, BA-4-17-12-2, ALU-1111; (11) Sakmarella cf. S. fluegeli Davydov in Davydov, Krainer, and Chernykh, Reference Davydov, Krainer and Chernykh2013, subaxial section, BA-4-11-2, ALU-1112; (10, 12) Sakmarella spp., (10) axial section, BA-4-19-3, ALU-1113, (12) oblique subaxial section, BA-4-27-1-1, ALU-1115; (13) Sakmarella cf. S. implicata (Schellwien, Reference Schellwien1908), axial section, BA-4-37-1, ALU-1116.

Figure 6. Lower Permian fusulinids from the Bagh-e Vang Formation, Bagh-e Vang section, in east-central Iran. (1) Leeina cf. L. quasifusuliniformis (Leven, Reference Leven1967), axial section, BA-4-38-1, ALU-1117; (2) Chalaroschwagerina sp., oblique section, BA-4-41-1-1, ALU-1118; (3) Biwaella sp., axial section, BA-4-57-5, ALU-1119; (4, 5) Sakmarella spp., (4) axial section, BA-4-47-1, ALU-1120, (5) oblique section, BA-5-4-3, ALU-1121; (6) Paraskinnerella? sp., subaxial section, BA-4-53-1, ALU-1122; (7, 8) Sakmarella spp., (7) axial section, BA-5-20-1-1, ALU-1124, (8) subaxial section, BA-5-8-2, ALU-1126.

Figure 7. Lower Permian fusulinids from the Bagh-e Vang Formation, Bagh-e Vang section, in east-central Iran. (1) Cuniculinella? spp., subaxial section, BA-14-3, ALU-1128; (2) Sakmarella? sp., axial section, BA-47-18-3, ALU-1129; (3–6) Silicified Leeina sp., (3) axial section, BA-14-5-1, ALU-1130, (4) oblique section, BA-47-18-4, ALU-1131, (5) oblique axial section, BA-55-5-1, ALU-1132, (6) oblique axial section, BA-55-11-1, ALU-1133. (7) Leeina isomie (Igo, Reference Igo1965), axial section, BA-61-1, ALU-1134.

Biozone 1

Pamirina darvasica and Sakmarella spp. Zone

Definition

This zone, with a thickness of ~8 m in the Bagh-e Vang section, is an assemblage zone characterized by the first occurences of two fusulinid markers, Pamirina and Sakmarella. The base of this biozone rests on the Sardar Formation. The top of this biozone is characterized by the first occurrence/first appearance datum (FO/FAD) of the markers of the overlying zone (i.e., several species of the fusulinid Cuniculinella; see later discussion, with “Cuniculina” pre-occupied). It is noteworthy that the FO of Pamirina is probably coeval with its probable FAD in the Pamirs in the upper Yakhtashian (see Leven, Reference Leven1970; Davydov et al., Reference Davydov, Krainer and Chernykh2013).

Distribution

This first biozone is recorded in the Bagh-e Vang section, from samples BA-4 to BA-13, but not in the Shesh Angosht section.

Composition

The microproblematica, smaller foraminifers, and fusulinids in biozone 1 (Figs. 3–6) include Archaeolithoporella hidensis Endo, Reference Endo1961; Tubiphytes obscurus Maslov, Reference Maslov1956; T. ex gr. obscurus; Epimonella sp.; Latitubiphytes sp.; Eotuberitina reitlingerae Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1958; Bradyina ex gr. lepida Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1950; B. sp. 2; B. sp. 3; Climacammina spp.; Deckerella sp.; Tetrataxis parviconica Lee and Chen in Lee, Chen, and Chu, Reference Lee, Chen and Chu1930; Orthovertella sp.; Hemigordiellina sp.; Schubertella ex gr. S. paramelonica Suleimanov, Reference Suleimanov1949; S. aff. S. exilis Suleimanov, Reference Suleimanov1949; S. spp.; Toriyamaia sp.; Mesoschubertella sp.; Biwaella sp.; Levenella sp.; Pamirina darvasica Leven, Reference Leven1970; P. chinlingensis (Wang and Sun, Reference Wang and Sun1973); P. staffellaeformis Zhou, Sheng, and Wang, Reference Zhou, Sheng and Wang1987; P. sp.; Darvasites (Alpites?) sp.; Sakmarella cf. S. fluegeli Davydov in Davydov, Krainer, and Chernykh, Reference Davydov, Krainer and Chernykh2013; S. cf. S. implicata (Schellwien, Reference Schellwien1908); Leeina cf. L. quasifusuliniformis (Leven, Reference Leven1967); Grozdilovia sp.; Chalaroschwagerina? sp.; Chusenella sp.; Paraskinnerella? sp.

Remarks

The regional Pamirina darvasica and Sakmarella spp. Zone is assigned to the upper Yakhtashian based on the recent dating of the Pamirina darvasica Zone of Darvaz by Davydov et al. (Reference Davydov, Krainer and Chernykh2013) and Krainer et al. (Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019) in the Carnic Alps. However, the same interval was previously included in the lower Bolorian by Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam (Reference Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam2004), who had another interpretation of the stratigraphic range of Pamirina (see discussion in Davydov et al., Reference Davydov, Krainer and Chernykh2013).

Biozone 2

Misellina (Brevaxina) dyrhenfurthi Zone

Definition

This zone is the range zone of Misellina (Brevaxina) dyrhrenfurthi (Dutkevich in Likharev, Reference Likharev and Likharev1939), with a thickness of 3 m in the Shesh Angosht section. The lower boundary of this zone is characterized by the FO/FAD of Misellina (Brevaxina) dyhrenfurthi and its upper boundary is marked by the last occurrence/last appearance datum (LO/LAD) of Misellina (Brevaxina) dyhrenfurthi and/or the FO/FAD of Cuniculinella.

Distribution

Misellina (Brevaxina) dyrhenfurthi was not recovered in our samples from the Bagh-e Vang section, but it was found in this locality by Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam (Reference Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam2004). We have found Misellina (Brevaxina) dyrhenfurthi in the Shesh Angosht section (Fig. 8), where it is present in the SHB-1 to SHB-3 samples.

Figure 8. Fusulinid biozonation and faunal distribution of the Bagh-e Vang Formation, Shesh Angosht section, east-central Iran.

Composition

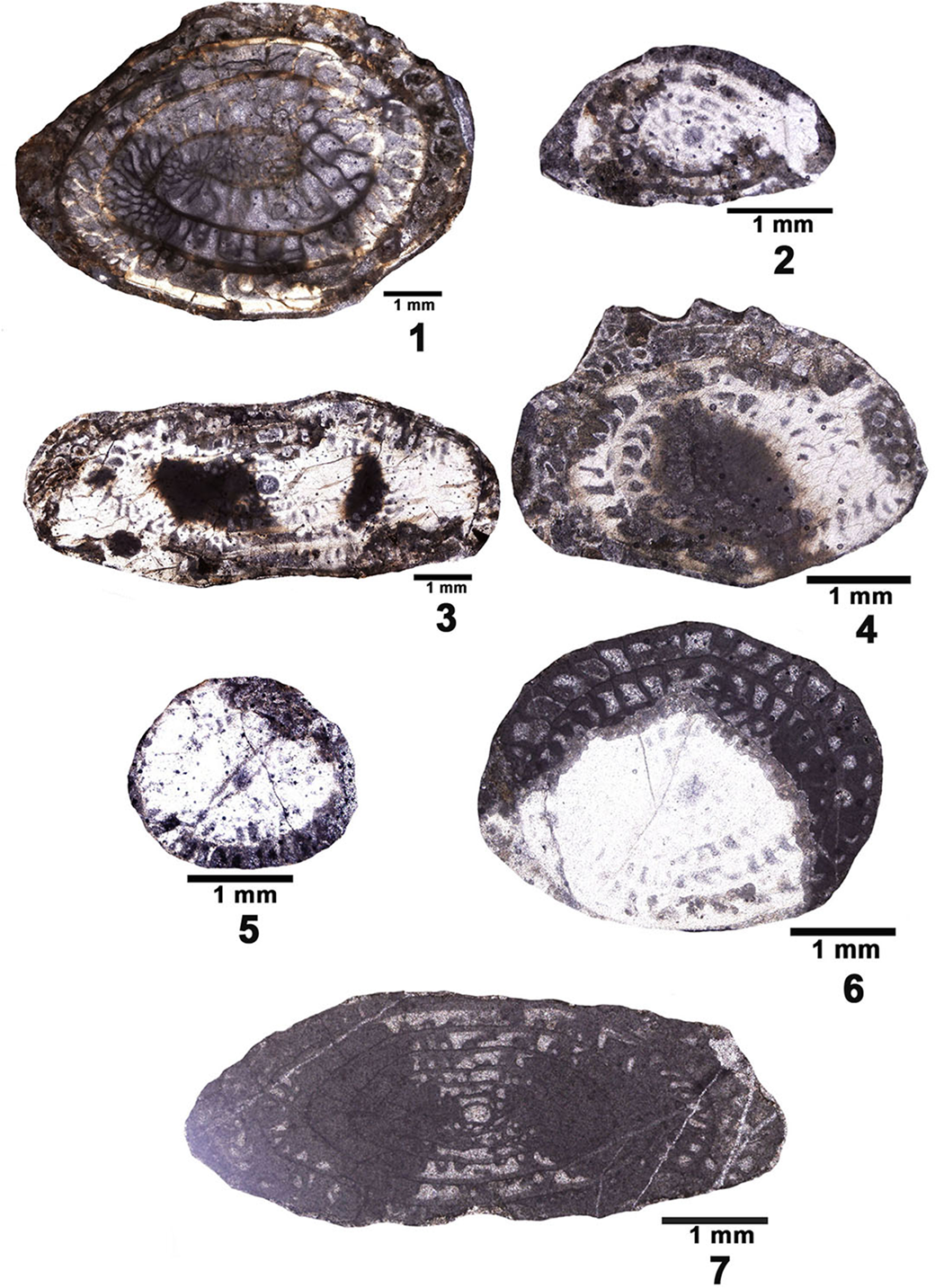

The second biozone contains the microproblematica, smaller foraminifers, and fusulinids: Tubiphytes obscurus; Endothyra sp.; Deckerella sp.; Hemigordiellina regularis (Lipina, Reference Lipina1949); Schubertella sp.; Neofusulinella? pseudogiraudi (Sheng, Reference Sheng1963); Darvasites (Alpites) sinensis; Sakmarella sp.; and Misellina (Brevaxina) dyrhenfurthi (Figs. 9, 10).

Figure 9. Lower Permian small foraminiferans and calcareous algae from the Bagh-e Vang Formation, Shesh Angosht section, in east-central Iran. (1) Endothyra sp., axial section, SHB-1-3-1, ALU-1135; (2) Deckerella sp., oblique longitudinal section, SHB-1-7-2, ALU-1136; (3) Hemigordiellina regularis (Lipina, Reference Lipina1949), transverse section, SHB-1-8-1, ALU-1137; (4) Uralogordiopsis cf. U. ovatus (Grozdilova, Reference Grozdilova1956), subaxial section, SHB-6-4-3, ALU-1140; (5–7). Uralogordiopsis longus (Grozdilova, Reference Grozdilova1956), (5) subtransverse section, SHB-6-4-2, ALU-1142, (6) axial section, SHB-6-5-4, ALU-1143, (7) axial section, SHB-6-9-3, ALU-1145; (8) Hemigordiellina sp., axial section, SHB-6-7-1-2, ALU-1153; (9) Agathammina sp., transverse section, SHB-6-16-2, ALU-1155; (10) Tuberitina collosa Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1950, axial section, SHB-6-9-4, ALU-1160; (11) Langella sp., axial section, SHB-6-26-1, ALU-1164; (12) Spireitlina ex gr. S. conspecta (Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1950), subaxial section, SHB-6-26-2, ALU-1165; (13) Nodosaria cf. N. mirabilis Lipina, Reference Lipina1949, axial section, SHB-6-33-1, ALU-1172; (14, 15) Uralogordiopsis permicus (Grozdilova, Reference Grozdilova1956), (14) axial section, SHB-6-37-1, ALU-1178, (15) subaxial section, SHB-8-2-3, ALU-1179; (16) Olgaorlovella sp., random section, SHB-12-7-1, ALU-1192; (17) Tetrataxis sp., subaxial section, SHB-12-8-2, ALU-1195; (18) Lasiodiscus ex gr. L. tenuis Reichel, Reference Reichel1946, axial section, SHB-48-1, ALU-1204; (19) Tubiphytes obscurus Maslov, Reference Maslov1956, oblique section, SHB-1-1-2, ALU-1216; (20) Tabasoporella sp. (see Rashidi and Senowbari-Daryan, Reference Rashidi and Senowbari-Daryan2010), transverse section, SHB-6-10-4, ALU-1221; (21) Pseudovermiporella ex gr. P. nipponica (Endo in Endo and Kanuma, Reference Endo and Kanuma1954), transverse sections, SHB-6-21-2, ALU-1228; (22) Mizzia cornuta Kochansky and Herak, Reference Kochansky-Devidé and Herak1960, subtangential section, SHB-8-4, ALU-1239; (23) Palaeonubecularia sp., oblique section, SHB-8-4-3-3, ALU-1240; (24) Clavaporella cf. C. media (Vachard in Vachard and Montenat, Reference Vachard and Montenat1981), sublongitudinal section, SHB-11-1, ALU-1249; (25, 26) Pseudovermiporella cf. P. sodalica Elliott, Reference Elliott1958, two oblique sections, (25) SHB-16-2, ALU-1251, (26) SHB-18-1, ALU-1252; (27) oncoid of Archaeolithoporella sp., longitudinal section, SHB-19-3, ALU-1253; (28) Archaeolithoporella hidensis Endo, Reference Endo1961, longitudinal section, SHB-53-6, ALU-1254.

Remarks

This lower Bolorian zone has been traditionally mentioned in the Cisuralian fusulinid-based biozonation since the work of Deprat (Reference Deprat1915) and Leven (Reference Leven1967, Reference Leven1997, Reference Leven1998). It was recently re-studied in its type locality by Angiolini et al. (Reference Angiolini, Campagna, Borlenghi, Grunt, Vachard, Vezzoli and Zanchi2016).

Biozone 3

Cuniculinella spp. Zone

Definition

This zone is the probable range zone of Cuniculinella, the taxonomy of which is discussed hereafter. Its thickness is 24 m in the Bagh-e Vang section and 41 m in the Shesh Angosht section. The base of this biozone is characterized by the FO/FAD of Cuniculinella. The top of this biozone is marked by the LO/LAD of this genus and/or the FO/FAD of typical Misellina (Misellina).

Distribution

In Bagh-e Vang section, this biozone extends from BA-14 to BA-46; in the Shesh Angosht section, it is located between SHB-10 and SHB-52.

Composition

In our material from the Bagh-e Vang section, we found the following microproblematica, smaller foraminifers, and fusulinids (Fig. 7): Tubiphytes sp.; Endoteba sp.; Globivalvulina ex gr. G. bulloides (Brady, Reference Brady1876); Schubertella spp.; Cuniculinella? sp.; and Leeina spp. The sample BA14 collected near the base of this zone was silicified. The material of Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam (Reference Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam2004) was richer in larger fusulinids with Cuniculinella hawkinsiformis (Igo, Reference Igo1965), C. vulgarisiformis (Morikawa, Reference Morikawa1952), C. globosaeformis (Leven, Reference Leven1967), Skinnerella spp., “Iranella” spp. (this name is also pre-occupied according to F. Le Coze, personal communication, June 2019), Leeina fusiformis (Schellwien in Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth, Reference Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth1909), and Paraleeina postkraffti (Leven, Reference Leven1967). In the Shesh Angosht section, we identified the microproblematica, cyanobacteria, dasycladale algae, smaller foraminifers, and fusulinids: Tubiphytes obscurus; Archaeolithoporella hidensis; Mizzia cornuta Kochansky and Herak, Reference Kochansky-Devidé and Herak1960; Tabasoporella sp.; Tuberitina collosa Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1950; Climacammina spp.; Spireitlina ex gr. S. conspecta (Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1950); Palaeonubecularia sp.; Pseudovermiporella aff. P. longipora (Praturlon, Reference Praturlon1963); P. ex gr. P. nipponica (Endo in Endo and Kanuma, Reference Endo and Kanuma1954); Hemigordiellina sp.; Agathammina spp.; Uralogordiopsis longus (Grozdilova, Reference Grozdilova1956); U. permicus (Grozdilova, Reference Grozdilova1956); U. cf. U. ovatus (Grozdilova, Reference Grozdilova1956); “Multidiscus” sp.; Nodosaria cf. N. mirabilis Lipina, Reference Lipina1949; Langella sp.; Neofusulinella? pseudogiraudi; Sakmarella sp.; Leeina isomie (Igo, Reference Igo1965); L. sp.; Chalaroschwagerina? vulgaris (Schellwien in Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth, Reference Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth1909); C.? cf. C. vulgaris; Cuniculinella hawkinsiformis; C. vulgarisiformis; C. tumida Skinner and Wilde, Reference Skinner and Wilde1965a; C. globosa (Schellwien in Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth, Reference Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth1909); C. spp.; and Praeskinnnerella sp. (Figs. 9–14).

Figure 10. Lower Permian fusulinids and calcareous algae from the Bagh-e Vang Formation, Shesh Angosht section, in east-central Iran. (1) Pseudovermiporella nipponica (Endo in Endo and Kanuma, Reference Endo and Kanuma1954), subtangential section, SHB-53-10, ALU-1255; (2) Mizzia yabei (Karpinsky, Reference Karpinsky1909) emend. Pia, Reference Pia1920, transverse section, SHB-53-11, ALU-1256; (3–5) Misellina (Brevaxina) dyrenfurthi (Dutkevich, Reference Dutkevich and Likharev1939), (3) subtransverse section, SHB-1-2-3, ALU-1261, (4) subaxial section, SHB-1-12-5, ALU-1263, (5) oblique section, SHB-1-8-3, ALU-1262; (6–8) Neofusulinella? pseudogiraudi (Sheng, Reference Sheng1963), (6) transverse section, SHB-1-5-2, ALU-1264, (7) subtransverse section, SHB-1-8-2, ALU-1265, (8) subaxial section, SHB-7-1, ALU-1270; (9) Toriyamaia sp., oblique section, SHB-14-1, ALU-1274; (10) Misellina (Misellina) cf. M. (M.) termieri (Deprat, Reference Deprat1915), subaxial section, SHB-53-4, ALU-1277; (11) Chalaroschwagerina? vulgaris (Schellwien in Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth, Reference Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth1909), oblique section, SHB-4-1-2, ALU-1278; (12, 13). Sakmarella sp., (12) oblique section, SHB-1-4-2, ALU-1279; (13) subtransverse section, SHB-6-12-1, ALU-1280; (14) Leeina isomie (Igo, Reference Igo1965), subtransverse section, SHB-6-6-5, ALU-1288; (15) Leeina sp., transverse section, SHB-6-1-1, ALU-1281; (16) Darvasites (Alpites) sinensis (Chen, Reference Chen1934), axial section, SHB-1-7-4, ALU-1282.

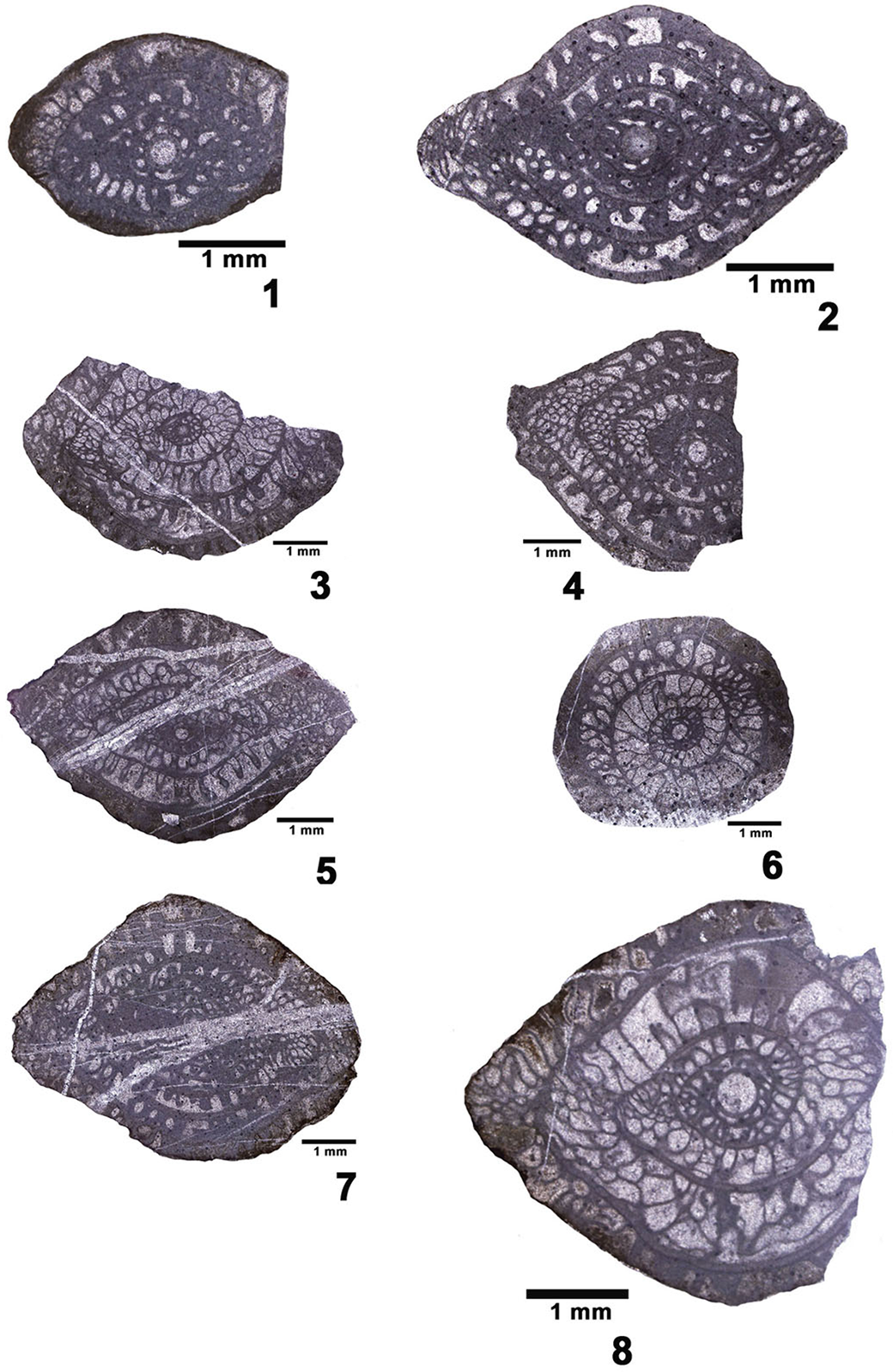

Figure 11. Lower Permian fusulinids from the Bagh-e Vang Formation, Shesh Angosht section, in east-central Iran. (1–6) Cuniculinella vulgarisiformis (Morikawa, Reference Morikawa1952), (1) oblique subaxial section, SHB-6-16-1, ALU-1292, (2) oblique section, SHB-6-17-1, ALU-1293, (3) subaxial section, SHB-6-18-1, ALU-1295, (4) axial section, SHB-6-19-1, ALU-1296, (5) subaxial section, SHB-6-20-1, ALU-1297, (6) subaxial section, SHB-6-24-2, ALU-1298; (7) Leeina isomie (Igo, Reference Igo1965), subaxial section, SHB-6-9-1, ALU-1289.

Figure 12. Lower Permian fusulinids from the Bagh-e Vang Formation, Shesh Angosht section, in east-central Iran. (1) Cuniculinella hawkinsiformis (Igo, Reference Igo1965), axial section, SHB-6-2-2, ALU-1283; (2) Praeskinnnerella sp., subaxial section, SHB-6-32-3, ALU-1302; (3–5) Cuniculinella sp., (3) axial section, partly silicified, SHB-6-31-2, ALU-1305, (4) axial section, SHB-6-38-1, ALU-1307, (5) axial section, SHB-6-31-3, ALU-1306; (6) Cuniculinella vulgarisiformis (Morikawa, Reference Morikawa1952), axial section, SHB-6-34-2, ALU-1309; (7, 8) Cuniculinella tumida Skinner and Wilde, Reference Skinner and Wilde1965a, (7) oblique axial section, SHB-8-3-2, ALU-1312, (8) oblique subaxial section, SHB-8-4-2, ALU-1314.

Figure 13. Lower Permian fusulinids from the Bagh-e Vang Formation, Shesh Angosht section, in east-central Iran. (1, 2) Cuniculinella tumida Skinner and Wilde, Reference Skinner and Wilde1965a, (1) axial section, SHB-8-11-1, ALU-1317, (2) axial section, SHB-8-12-2, ALU-1319; (3) Chalaroschwagerina globosa (Schellwien in Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth, Reference Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth1909), axial section, SHB-8-6-2, ALU-1320; (4) Cuniculinella vulgarisiformis (Morikawa, Reference Morikawa1952), axial section, SHB-8-9-1-1, ALU-1322; (5, 6) Chalaroschwagerina? vulgaris (Schellwien in Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth, Reference Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth1909), (5) axial section, SHB-9-3-1, ALU-1334, (6) subaxial section, SHB-9-10-2, ALU-1335; (7) Cuniculinella vulgarisiformis (Morikawa, Reference Morikawa1952), axial section, SHB-9-5-1, ALU-1336; (8) Cuniculinella globosaeformis (Leven, Reference Leven1967), oblique axial section, SHB-9-17-1, ALU-1343.

Figure 14. Lower Permian fusulinids from the Bagh-e Vang Formation, Shesh Angosht section, in east-central Iran. (1) Chalaroschwagerina? vulgaris (Schellwien in Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth, Reference Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth1909), subaxial section, SHB-9-22-1, ALU-1350; (2) Cuniculinella vulgarisifomis (Morikawa, Reference Morikawa1952), oblique axial section, SHB-9-22-2, ALU-1351; (3, 4) Cuniculinella spp.; (3) transverse section, SHB-12-8-1, ALU-1348, (4) transverse section, SHB-9-23-1, ALU-1347; (5) Leeina fusiformis (Schellwien in Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth, Reference Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth1909), subaxial section, SHB-12-2-1, ALU-1352; (6) Leeina isomie (Igo, Reference Igo1965), axial section, SHB-19-1, ALU-1353; (7, 8) Cuniculinella cf. turgida Skinner and Wilde, Reference Skinner and Wilde1965a, (7) axial section, SHB-9-19-1, ALU-1344. (8) subaxial section, SHB-9-20-1, ALU-1345.

Remarks

A mid-Bolorian age is suggested here for this biozone because of its occurrence between a well-characterized lower Bolorian biozone and an upper Bolorian biozone, but this suggestion can be debated because, so far, Cuniculinella has not been mentioned, either in Leven's work in Darvaz (e.g., Leven et al., Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992) or in the Bolorian stratotype by Angiolini et al. (Reference Angiolini, Campagna, Borlenghi, Grunt, Vachard, Vezzoli and Zanchi2016). In this case, this local zone corresponds either to the top of the Misellina (Brevaxina) dyhrenfurthi Zone (i.e., upper lower Bolorian); or to the lower part of the Misellina (Brevaxina) parvicostata Zone (i.e., lower upper Bolorian).

Biozone 4

Misellina (Misellina) cf. M. (M.) termieri Zone

Definition

This appearance zone is characterized by the FO/FAD of Misellina (Misellina) cf. M. (M.) termieri (Deprat, Reference Deprat1915). It is 12 m thick in the Bagh-e Vang section and 1 m thick in the Shesh Angosht section.

Distribution

This biozone extends from BA-47 to BA-62 in the Bagh-e Vang section and occurs in the Shesh Angosht section in SHB-53.

Composition

The microproblematica, smaller foraminifers, fusulinids, and cyanobacteria occurring in this zone in Bagh-e Vang section are: Tubiphytes obscurus; Palaeotextularia sp.; Deckerella sp.; Climacammina sp.; Globivalvulina ex gr. G. bulloides; Hemigordiellina sp.; Agathammina sp.; Pachyphloia sp.; Nankinella cf. N. nagatoensis Toriyama, Reference Toriyama1958; Schubertella spp.; Toriyamaia sp.; Leeina isomie; Misellina (Misellina) cf. M. (M.) termieri; and M. (M.) sp. (Figs. 5, 7). The microproblematica, smaller foraminifers, and fusulinids occurring in this zone in Shesh Angosht section are: Archaeolithoporella hidensis; A. sp.; Mizzia yabei (Karpinsky, Reference Karpinsky1909) emend. Pia, Reference Pia1920; Eotuberitina reitlingerae; Lasiodiscus ex gr. L. tenuis Reichel, Reference Reichel1946; Endothyra sp.; Palaeotextularia sp.; Deckerella sp.; Climacammina sp.; Tetrataxis sp.; Globivalvulina sp.; Pseudovermiporella nipponica; P. cf. P. sodalica Elliott, Reference Elliott1958; Schubertella sp.; Neofusulinella? pseudogiraudi; Toriyamaia sp.; Leeina fusiformis; L. isomie; and Misellina (Misellina) cf. M. (M.) termieri (Figs. 9, 10).

Remarks

Our Misellina (Misellina) cf. M. (M.) termieri is not necessarily the M. (M.) aff. M. (M.) termieri in the sense of Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam (Reference Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam2004, pl. 6, fig. 7), but most probably something similar to Misellina (Misellina) claudiae (Deprat, Reference Deprat1915) in the sense of Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam (Reference Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam2004, pl. 6, fig. 3), which was found by these authors in the same sample as Misellina (Brevaxina) parvicostata (pl. 6, figs. 4, 8–10) and is the zonal marker of the upper Bolorian. Inversely, if our Misellina (Misellina) cf. M. (M.) termieri is the M. (M.) aff. M. (M.) termieri in the sense of Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam (Reference Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam2004), this last local biozone 4 could be lower Kubergandian in age. However, that is unlikely, due to the absence of associated Armenina found by Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam (Reference Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam2004).

Materials and methods

For the biostratigraphic study, 62 and 49 samples were collected from the Bagh-e Vang Formation in the Bagh-e Vang and Shesh Angosht sections, respectively. In order to study smaller foraminifers and algae, 128 thin sections were prepared as well as 250 oriented thin sections for fusulinid identification. The biostratigraphical analyses and biozones described in this study have been established following Salvador (Reference Salvador1994), Armstrong and Brasier (Reference Armstrong and Brasier2008), and Owen (Reference Owen2009), with references therein. Taxonomically, we have followed the classification of Vachard (Reference Vachard and Montenari2016, Reference Vachard, Lucas and Shen2018) for the Paleozoic foraminifers and that of Vachard et al. (Reference Vachard, Hauser, Martini, Zaninetti, Matter and Peters2001a) and Vachard (Reference Vachard, Lucas and Shen2018) for the Paleozoic cyanobacteria, calcareous algae, and microproblematica. In the regional biozones established here, the lower boundary of each zone is defined by the presence of a characteristic assemblage or a characteristic taxon. The upper boundary is generally conventional and placed under the base of next zone. The ranges of markers of biozones were mainly compiled from Leven (Reference Leven1970, Reference Leven1993a, b, Reference Leven1997, Reference Leven1998), Leven et al. (Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992), Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam (Reference Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam2004), Davydov et al. (Reference Davydov, Krainer and Chernykh2013), and Krainer et al. (Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019). In this research, specimens larger than 1 mm are considered large in size, those between 500 μm and 1000 μm are medium in size, and those less than 500 μm are small in size.

Repository and institutional abbreviation

The prepared thin sections are housed in the Paleontology Repository of Lorestan University, Iran (Collection ALU-900–ALU-1353).

Systematic micropaleontology

This section describes foraminiferal taxa that are biostratigraphically interesting. The main nomenclatural problem is a taxon called Cuniculina or Cuniculinella (in part) in the literature, the most advanced forms of chalaroschwagerinids exhibiting cuniculi.

The abbreviations used are as follows: w = width; D = diameter; h = height of last whorl; s = wall thickness.

Subkingdom Rhizaria Cavalier-Smith, Reference Cavalier-Smith2002

Phylum Foraminifera d'Orbigny, Reference Orbigny1826 emend. Cavalier-Smith, Reference Cavalier-Smith2003

Class Fusulinata Maslakova, Reference Maslakova and Menner1990 nom. translat. Gaillot and Vachard, Reference Gaillot and Vachard2007 emend. Vachard, Krainer, and Lucas, Reference Vachard, Krainer and Lucas2013

Subclass Fusulinana Maslakova, Reference Maslakova and Menner1990 nom. correct. Vachard, Pille, and Gaillot, Reference Vachard, Pille and Gaillot2010 emend. Vachard, Reference Vachard and Montenari2016

Order Endothyrida Fursenko, Reference Fursenko1958

Suborder Endothyrina Bogush, Reference Bogush1985

Superfamily Bradyinoidea Rauzer-Chernousova et al., Reference Rauzer-Chernousova, Bensh, Vdovenko, Gibshman, Leven, Lipina and Chediya1996

Family Bradyinidae Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1950 nom. translat. Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1958

Genus Bradyina Möller, Reference Möller1878

Type species

Bradyina nautiliformis Möller, Reference Möller1878; subsequently designated by Cushman (Reference Cushman1928).

Other species

See Morozova (Reference Morozova1949); Reitlinger (Reference Reitlinger1950); and Pinard and Mamet (Reference Pinard and Mamet1998).

Diagnosis

Tests free, nautiloid, involute, and planispirally coiled, with a few whorls and chambers. Septa short with additional, longer and thinner, pre- and post-septal lamellae. Alveolar wall overlain by a continuous tectum. Simple aperture becomes cribrate in the last chamber. Additional sutural pores present.

Occurrence

Upper Visean (Poty et al., Reference Poty, Devuyst and Hance2006; Somerville, Reference Somerville2008; Hance et al., Reference Hance, Hou and Vachard2011) to upper Cisuralian (Baryshnikov et al., Reference Baryshnikov, Zolotova and Kosheleva1982; Filimonova, Reference Filimonova2010; Vachard, Reference Vachard, Lucas and Shen2018). Our study makes it possible to establish that the LAD of Bradyina is definitively upper Yakhtashian. The Guadalupian and Lopingian species assigned to Bradyina belong in reality to Postendothyra (see Hance et al., Reference Hance, Hou and Vachard2011; Vachard, Reference Vachard, Lucas and Shen2018). The genus Bradyina was Paleotethyan and Panthalassan in the Upper Mississippian, and cosmopolitan since the Lower Pennsylvanian (e.g., Mamet, Reference Mamet1970; Hance et al., Reference Hance, Hou and Vachard2011; Vachard, Reference Vachard, Lucas and Shen2018).

Bradyina spp.

Figure 3.3–3.6, 3.9, 3.10

Remarks

The exact LAD of Bradyina was discussed in Vachard (Reference Vachard, Lucas and Shen2018) and Krainer et al. (Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019). Our material makes it possible to establish that this LAD is upper Yakhtashian in age because representatives of this genus are still numerous in samples BA-4 and BA-5, but are absent from younger samples, despite the paleoenvironments remaining identical (i.e., a shallow carbonate platform).

Suborder Palaeotextulariina Hohenegger and Piller, Reference Hohenegger and Piller1975 emend. Vachard, Reference Vachard and Montenari2016

Superfamily Endoteboidea Vachard, Krainer, and Lucas, Reference Vachard, Krainer and Lucas2013

Family Endotebidae Vachard et al., Reference Vachard, Martini, Rettori and Zaninetti1994

Genus Endoteba Vachard and Razgallah, Reference Vachard and Razgallah1988

Type species

Endoteba controversa Vachard and Razgallah, Reference Vachard and Razgallah1988, by original designation.

Other species

See Vachard and Razgallah (Reference Vachard and Razgallah1988) and Vachard et al. (Reference Vachard, Martini, Rettori and Zaninetti1994).

Diagnosis

Endothyroidally coiled Palaeotextulariina with faint deviations of the axis. Wall brownish, microgranular with a calcareous, or rarely siliceous, agglutinate. Aperture terminal, basal simple.

Occurrence

The genus Endoteba first occured in the upper Cisuralian (Vachard et al., Reference Vachard, Martini and Zaninetti2001b; Vachard, Reference Vachard, Lucas and Shen2018; Krainer et al., Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019; and this paper). It was recently mentioned in the Kubergandian (lower Guadalupian) of Japan (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi2019). It becomes abundant in the Capitanian (upper Guadalupian), is rare in the Lopingian and Lower Triassic, and diversifies again in the Middle Triassic (Vachard et al., Reference Vachard, Martini, Rettori and Zaninetti1994).

Endoteba sp.

Figure 3.11

Remarks

There was a question about the exact FAD of Endoteba (see Vachard et al., Reference Vachard, Martini and Zaninetti2001b and Vachard, Reference Vachard, Lucas and Shen2018). Our samples indicate a FO (first local occurrence), and probable FAD (oldest occurrence), of this genus in the upper Yakhtashian of central Iran.

Class Miliolata Saidova, Reference Saidova1981

Order Cornuspirida Mikhalevich, Reference Mikhalevich1980

Superfamily Cornuspiroidea Bogdanovich in Subbotina et al., Reference Subbotina, Voloshinova and Azbel1981

Family Hemigordiidae Reitlinger in Vdovenko et al., Reference Vdovenko, Rauzer-Chernousova, Reitlinger and Sabirov1993

Genus Agathammina Neumayr, Reference Neumayr1887

Type species

Serpula pusilla Geinitz in Geinitz and Gutbier, Reference Geinitz and Gutbier1848, by original designation.

Other species

See Zolotova and Baryshnikov (Reference Zolotova, Baryshnikov, Rauzer-Chernousova and Chuvashov1980) and Gaillot and Vachard (Reference Gaillot and Vachard2007).

Diagnosis

Test formed by the coiling of an undivided tubular chamber similar to that of the eosigmoilinid archaediscoids and not, as classically indicated, to miliolid chambers with a quinqueloculine coiling. Wall porcelaneous. Aperture terminal and simple.

Occurrence

The Permian FAD and LAD of this genus, relatively common from Capitanian to Changhsingian, are poorly known; its so-called Triassic survivors are now assigned to other genera.

Agathammina sp.

Figures 3.23, 9.9

Remarks

As indicated by Gaillot and Vachard (Reference Gaillot and Vachard2007), the transitional form between Hemigordiellina and Agathammina seems to be Glomospira parapusilliformis Baryshnikov in Zolotova and Baryshnikov, Reference Zolotova, Baryshnikov, Rauzer-Chernousova and Chuvashov1980, which is Kungurian in age. Our samples indicate a FO (and probable FAD) of this genus in the upper Bolorian; this datum is relevant to a problem mentioned by Gaillot and Vachard (Reference Gaillot and Vachard2007, p. 87) and Vachard (Reference Vachard, Lucas and Shen2018, p. 221) concerning the exact age of the FAD of the genus Agathammina.

Family Neodiscidae Lin, Reference Lin1984 nom. translat. and emend. Gaillot and Vachard, Reference Gaillot and Vachard2007

Genus Uralogordiopsis Vachard in Krainer, Vachard, and Schaffhauser, Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019

Type species

Uralogordiopsis grozdilovae Vachard in Krainer, Vachard, and Schaffhauser, Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019, by original designation.

Other species

See Krainer et al. (Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019).

Diagnosis

Planispiral, lenticular, and often biumbilicate. Proloculus is followed by an undivided tubular chamber with a high lumen and poorly developed buttresses. Porcelaneous wall generally well preserved and amber-colored. Aperture terminal and simple.

Occurrence

Cisuralian of the Urals, Carnic Alps, and Mexico; Kubergandian of Japan and northern Afghanistan; Upper Murgabian of Japan; Guadalupian of Transcaucasia; ?Guadalupian of Yunnan (according to Krainer et al., Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019).

Remarks

Uralogordiopsis differs from Hemigordius by the bilayered wall and the much larger size, and from Uralogordius Gaillot and Vachard, Reference Gaillot and Vachard2007 (= Arenovidalina sensu Baryshnikov et al., Reference Baryshnikov, Zolotova and Kosheleva1982) (Vachard et al., Reference Vachard, Flores de Dios, Buitrón and Grajales2000a, p. 9; Vachard and Bouyx, Reference Vachard and Bouyx2001; not Ho, Reference Ho1959) by the planispiral coiling entirely evolute and the discoid profile.

Uralogordiopsis spp.

Figure 9.4–9.7, 9.14, 9.15

Remarks

We have found Uralogordiopsis cf. U. ovatus (Grozdilova, Reference Grozdilova1956) and U. longus (Grozdilova, Reference Grozdilova1956) in sample SHB-6, and U. permicus (Grozdilova, Reference Grozdilova1956) in samples SHB-6 and SHB-8. Such biodiversity in a few beds of the studied section indicates an acme and diversification of this genus in the mid-Bolorian Cuniculinella sp. Zone. This local datum is possibly a general datum for the genus Uralogordiopsis, recently described by Vachard in Krainer et al. (Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019), and still poorly known.

Order Fusulinida Fursenko, Reference Fursenko1958

Suborder Staffellina Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wang and Wang1981 emend. Vachard, Reference Vachard and Montenari2016

Superfamily Staffelloidea Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1949 nomen translat. Solovieva, Reference Solovieva1978

Family Nankinellidae Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1963

Genus Nankinella Lee, Reference Lee1934

Type species

Staffella discoides Lee, Reference Lee1931, by original designation.

Other species

See Sheng (Reference Sheng1963); Rozovskaya (Reference Rozovskaya1975); Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Sheng and Zhang1981); and Zhang (Reference Zhang1982).

Diagnosis

Tests lenticular to rhombic, carinate, and moderate- to large-sized. Planispiral and involute, with planar septa, and faint pseudochomata. The wall, originally aragonitic, becomes secondarily completely microsparitized. Aperture terminal and simple.

Occurrence

Guadalupian–Lopingian; on the Palaeotethyan, Neotethyan, and Panthalassan shelves.

Nankinella cf. N. nagatoensis Toriyama, Reference Toriyama1958

Figure 5.7

- Reference Toriyama1958

Nankinella nagatoensis Toriyama, p. 65, pl. 6, figs. 5–13.

- Reference Toriyama1958

Nankinella spp.; Toriyama, p. 68, pl. 6, figs 14, 15 (fide Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi2019).

- Reference Ishizaki1962

Nankinella nagatoensis; Ishizaki, p. 137, pl. 7, figs. 2, 3.

- Reference Kahler and Kahler1966

Nankinella nagatoensis; Kahler and Kahler, p. 57.

- Reference Leven1998

Nankinella nagatoensis; Leven, pl. 1, fig. 19.

- Reference Zhang and Hong1998

Nankinella nagatoensis; Zhang and Hong, p. 209, pl. 2, figs. 15–17.

- Reference Kobayashi2012

Nankinella nagatoensis; Kobayashi, fig. 6.40, 6.41, 6.52.

- Reference Kobayashi2017

Nankinella nagatoensis; Kobayashi, p. 33, pl. 1, figs. 51–54.

- Reference Kobayashi2019

Nankinella nagatoensis; Kobayashi, p. 58, pl. 3, figs. 21–30, 34–36.

Holotype

Axial section (No. GK.D1623, Loc. 497, Department of Geology, Kyushu University) from the Cisuralian of Akiyoshi (Loc. 4E97), Japan (Toriyama, Reference Toriyama1958, pl. 6, figs. 8, 13, which is the same specimen in two magnifications).

Occurrence

Guadalupian of Japan (Akiyoshi Group; Toriyama, Reference Toriyama1958), Transcaucasia (Asni Fm; Leven, Reference Leven1998), and South China (Zhang and Hong, Reference Zhang and Hong1998). It is found in the upper Bolorian Misellina (Misellina) cf. M. (M.) termieri Zone of the Bagh-e Vang section (sample BA-55).

Description

Species are relatively small for the genus, subrhomboidal or rarely inflated lenticular, with a few whorls and an exceptionally narrow whorl section in axial section. Measurements: D = 770–1250 μm; w = 500–540 μm; w/D = 0.40–0.77; proloculus diameter = 55 μm; number of whorls = 3–5; h = 250 μm; s = 20 μm.

Remarks

Our specimens are smaller than the type material of Toriyama (Reference Toriyama1958) and that of Kobayashi (Reference Kobayashi2019) from Japanese localities, but, characteristically, they show the highest whorl profile immediately above the tunnel and decreasing in height poleward.

Suborder Fusulinina Wedekind, Reference Wedekind1937 nom. correct. Loeblich and Tappan, Reference Loeblich and Tappan1961 emend. Vachard, Reference Vachard and Montenari2016

Superfamily Schubertelloidea Vachard in Vachard, Clift, and Decrouez, Reference Vachard, Clift and Decrouez1993

Diagnosis

According to Vachard (Reference Vachard and Montenari2016), tests are small- to medium-sized, short fusifom, and inflated fusiform to elongate fusiform. Spherical proloculi testify to generations A and B. Juvenaria generally lenticular and perpendicular to the adult whorls. Primitive forms of schubertelloids, such as Schubertina Marshall, Reference Marshall1969 emend. Davydov, Reference Davydov2011 (= Eoschubertella of the authors, non Thompson, Reference Thompson1937; see discussion in Ghazzay-Souli et al., Reference Ghazzay-Souli, Vachard and Razgallah2015, p. 257), have a unilayered, dark, microgranular wall, but, typically, the wall is bilayered with an outer, dark, microgranular tectum and an inner, thicker, yellowish, microgranular layer, called the protheca. Septa planar in the central parts of the chambers and faintly to moderately folded at the poles. Chomata small to moderate. Cuniculi very rarely conspicuous.

Occurrence

Mid-Bashkirian to upper Lopingian; with endemic or cosmopolitan genera.

Family Schubertellidae Miklukho-Maklay, Rauzer-Chernousova, and Rozovskaya, Reference Miklukho-Maklay, Rauzer-Chernousova and Rozovskaya1958 emend. Leven, Reference Leven1987

Subfamily Schubertellinae Skinner, Reference Skinner1931

Genus Schubertella Staff and Wedekind, Reference Staff and Wedekind1910 emend. Sheng, Reference Sheng1963

Type species

Schubertella transitoria Staff and Wedekind, Reference Staff and Wedekind1910, by subsequent designation by Thompson (Reference Thompson1937) due to the initial monotypy (see Dunbar and Henbest, Reference Dunbar and Henbest1942; Kahler in Ebner and Kahler, Reference Ebner and Kahler1989).

Other species

See Kahler and Kahler (Reference Kahler and Kahler1966); Rozovskaya (Reference Rozovskaya1975); Leven et al. (Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992); and Davydov (Reference Davydov2011).

Diagnosis

Test shortly fusiform, often asymmetrical. Early stage discoidal and forms a juvenarium perpendicular to the later stage, which is more or less fusiform, with acute poles. Septa numerous, unfluted in the center of the chambers and slightly fluted at the poles, especially in the outer whorls. Chomata low, asymmetrical, bordering a broad and low tunnel. Wall bilayered with an outer tectum and a protheca. Primitive forms (Schubertina or Eoschubertella of the authors) exhibit only the dark tectum. Advanced forms (Dutkevitchites, Oketaella, and Biwaella) show tectum and an inner porous layer. Aperture terminal and simple.

Occurrence

Bashkirian–lower Moscovian forms belong more probably to the genus Schubertina (or Eoschubertella of the authors), whereas typical representatives are distributed from the upper Moscovian (only lower Virgilian in North America; according to Sanderson et al., Reference Sanderson, Verville, Groves and Wahlman2001) to Lopingian. Schubertella is cosmopolitan from the Moscovian to the Wordian (see Rauzer-Chernousova et al., Reference Rauzer-Chernousova, Gryzlova, Kireeva, Leontovich, Safonova and Chernova1951; Skinner and Wilde, Reference Skinner, Wilde, Skinner and Wilde1966a, Reference Skinner and Wildeb; Leven, Reference Leven1998; Davydov, Reference Davydov2011); then, it is only Paleotethyan.

Schubertella ex gr. S. paramelonica Suleimanov, Reference Suleimanov1949

Figure 4.22

- Reference Suleimanov1949

Schubertella paramelonica Suleimanov, p. 31, pl.1, fig.5.

- Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019

Schubertella paramelonica; Vachard in Krainer et al., p. 66, pl. 16, figs. 2?, 7, 8, 10? (with 22 references in synonymy).

Holotype

Axial section (No. 3494, Institute of Geological Sciences, Academy of Sciences of the SSSR), from the Sakmarian (lower Tastubian) of Shak-Tau Hill, Russia (Suleimanov, Reference Suleimanov1949, pl. 1, fig. 5).

Occurrence

Cisuralian of southern Urals, Darvaz, Slovenia (as mentioned by Forke, Reference Forke2002), Artinskian of Japan (Ueno, Reference Ueno1996). Yakhtashian–Bolorian of the Carnic Alps (Krainer et al., Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019) and found in the upper Yakhtashian of the Bagh-e Vang section (sample BA-4).

Description

Shell is large for the genus, fusiform to ovoid with variable shapes of the lateral slopes, and broadly rounded to more or less truncated axial regions. The small and spherical proloculus is followed by a small juvenarium, nautiloid, and deviated at ~60° compared to the adult whorls. The septa are almost planar. The chomata are relatively well developed, especially in the penultimate and last whorls. Measurements: D = 500–700 μm; w = 675–1000 μm; w/D = 1.35–1.43; proloculus diameter = 30 μm; number of whorls = 4; h = 150 μm; s = 10 μm.

Remarks

Compared to the type material of Suleimanov (Reference Suleimanov1949), our specimens are smaller and have fewer whorls and a thinner wall.

Schubertella aff. S. exilis Suleimanov, Reference Suleimanov1949

Figure 5.1, 5.2

- Reference Suleimanov1949

Schubertella kingi var. exilis Suleimanov, p. 33, pl. 1, figs. 11–13.

- Reference Wang, Sheng and Zhang1981

Schubertella kingi var. exilis; Wang et al., p. 19, pl. 12, figs. 4, 5, 12.

- Reference Zhang1982

Schubertella kingi exilis; Zhang, p. 145, pl. 2, fig. 22.

- Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019

Schubertella exilis; Vachard in Krainer et al., p. 65, pl. 15, figs. 11–17, pl.16, fig. 1, pl. 17, figs. 1, 2 (with 21 references in synonymy).

Holotype

Axial section (No. 7637; Institute of Geologic Sciences, Academy of Sciences of the SSSR), from Sakmarian of Preurals, Russia (Suleimanov, Reference Suleimanov1949, pl. 1, fig. 11).

Occurrence

Cisuralian of the Paleotethys and Urals Ocean shelves (Krainer et al., Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019), lower Yakhtashian (Zweikofel Fm and Zottachkopf Fm) of the Carnic Alps (Davydov et al., Reference Davydov, Krainer and Chernykh2013; Krainer et al., Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019), and found in the upper Yakhtashian of the Bagh-e Vang section (sample BA-5).

Description

The elongate species of Schubertella correspond to the group of S. kingi Dunbar and Skinner, Reference Dunbar and Skinner1937. In this group, S. exilis is a relatively small and biconvex species. Measurements: D = 610–800 μm; w = 1200–2000 μm; w/D = 2.00–2.50; proloculus diameter = 20–25 μm; number of whorls = 4–5; h = 100–200 μm; s = 10 μm.

Remarks

Compared to the type material of Suleimanov (Reference Suleimanov1949), our specimens have a thinner wall and a smaller proloculus diameter.

Genus Neofusulinella Deprat, Reference Deprat1912b

Type species

Neofusulinella lantenoisi Deprat, Reference Deprat1913, by subsequent designation (Thompson, Reference Thompson1934, not Galloway and Ryniker, Reference Galloway and Ryniker1930).

Other species

See Kahler and Kahler (Reference Kahler and Kahler1966); Rozovskaya (Reference Rozovskaya1975); and Leven et al. (Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992).

Diagnosis

Test fusiform, medium-sized, with planar septa only folded in the polar extremities. Chomata moderately developed. Wall typically schubertelloid with dark tectum and yellowish primatheca. Aperture terminal and simple.

Occurrence

Bolorian–Murgabian (= Kungurian–Wordian) of the Paleotethyan shelves (Leven et al., Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992).

Genus Neofusulinella?

Remarks

Apparently, several representatives of the group Schubetella paramelonica were called Mesoschubertella by Ueno (Reference Ueno1996) (see below). On the other hand, Leven (Reference Leven1987) considered Mesoschubertella Kanuma and Sakagami, Reference Kanuma and Sakagami1957 as transitional between Schubertella and Yangchienia Lee, Reference Lee1934 (see Leven, Reference Leven1987, pl. 2, fig. 5), whereas the Mesoschubertella of Ueno (Reference Ueno1996) are obviously transitional between Schubertella and Neofusulinella Deprat, Reference Deprat1912b. Such forms, which are transitional between S. paramelonica and Neofusulinella giraudi (Deprat, Reference Deprat1915), are known from the upper Yakhtashian–Bolorian of Japan, Iran, and Darvaz (Uzbekistan), Pamir (Tajikistan), Thailand, and North and South China (Leven, Reference Leven1987; Ueno, Reference Ueno1996; Leven and Vazari Moghaddam, Reference Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam2004). We infer also that this transitional stage is present in Guatemala with Neofusulinella? muelleriedi (Thompson and Miller, Reference Thompson and Miller1944), as redescribed by Vachard et al. (Reference Vachard, Fourcade, Romero, Mendez, Cosillo, Alonzo, Requeña, Azema and Cros1997), Davydov (Reference Davydov2011), and Granier et al. (Reference Granier, Basso and Vachard2017).

Neofusulinella? pseudogiraudi (Sheng, Reference Sheng1963 non 1962)

Figure 10.6–10.8

- Reference Sheng1962

Schubertella pseudogiraudi Sheng, p. 427, pl. 1, figs. 8, 9 (holotype not designated).

- Reference Sheng1963

Schubertella pseudogiraudi Sheng, p. 159, pl. 4, figs. 14–19.

- Reference Sheng1965

Schubertella pseudogiraudi; Sheng, p. 566, pl. 5, figs. 15–17.

- Reference Kahler and Kahler1966

Schubertella pseudogiraudi; Kahler and Kahler, p. 211.

- Reference Rozovskaya1975

Schubertella (Schubertella) pseudogiraudi; Rozovskaya, p. 13.

- Reference Lin, Li, Chen, Zhou and Zhang1977

Schubertella pseudogiraudi; Lin et al., p. 34, pl. 6, fig. 20.

- Reference Chen and Wang1978

Schubertella pseudogiraudi; Chen and Wang, p. 26, pl. 3, figs. 36, 37.

- Reference Liu, Xiao and Dong1978

Schubertella pseudogiraudi; Liu, Xiao, and Dong, p. 20, pl. 2, fig. 4.

- Reference Igo, Rajah and Kobayashi1979

Schubertella pseudogiraudi; Igo et al., pl. 17, figs. 9, 10, pl. 18, figs. 11–14.

- Reference Zhou1982

Schubertella pseudogiraudi; Zhou, p. 230, pl. 1, fig. 10.

- Reference Xie1982

Schubertella pseudogiraudi; Xie, p. 15, pl. 6, fig. 7.

- Reference Zhang1982

Schubertella pseudogiraudi; Zhang, p. 144, pl. 2, figs. 18, 20, 21, 24, 25, 34, 35.

- Reference Zhou1982

Schubertella pseudogiraudi; Zhou, p. 230, pl. 1, fig. 10.

- Reference Zhou and Zhang1984

Schubertella pseudogiraudi; Zhou and Zhang, pl. 2, figs. 12, 13.

- Reference Zhou, Sheng and Wang1987

Schubertella pseudogiraudi; Zhou, Sheng, and Wang, pl. 3, fig. 10.

- Reference Leven1987

Schubertella pseudogiraudi; Leven, pl. 2, fig. 7.

- ?Reference Sun and Zhang1988

Schubertella pseudogiraudi; Sun and Zhang, pl. 1, fig. 7, pl. 2, figs. 15, 18, pl. 3, figs. 3, 13.

- Reference Zhang1992

Schubertella pseudogiraudi; Zhang, pl. 1, figs. 3, 7.

- Reference Ueno and Sakagami1993

Neofusulinella? pseudogiraudi; Ueno and Sakagami, p. 282, fig. 5.11–5.13.

- Reference Partoazar1995

Neofusulinella? pseudogiraudi; Partoazar, pl. 5, figs. 11–13 (from Ueno and Sakagami, Reference Ueno and Sakagami1993).

- Reference Leven and Okay1996

Schubertella pseudogiraudi; Leven and Okay, pl. 9, fig. 13.

- Reference Angiolini, Campagna, Borlenghi, Grunt, Vachard, Vezzoli and Zanchi2016

Neofusulinella pseudogiraudi; Angiolini et al., p. 567, figs. 9E–G, 13A–D, 14H, 15D–F.

Holotype

Axial section (No. 12009, Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Academia Sinica, Beijing, People's Republic of China) from the Maokou Limestone, near Zisongzheng of Wangmo, Kueichow Province, China (Sheng, Reference Sheng1963, pl. 4, fig. 15).

Occurrence

Bolorian–Murgabian (= Kungurian–Wordian) of eastern Paleotethys (as indicated by the synonymy list, above), Darvaz (Leven, Reference Leven1987), and Turkey (Leven and Okay, Reference Leven and Okay1996). Identified from the lower and mid-Bolorian Misellina (Brevaxina) dyhrenfurthi and Cuniculinella spp. zones of the Shesh Angosht section (samples SHB-1 and SHB-7).

Description

The test is fusiform, moderately sized, and primitive for the genus; it is harmoniously vaulted in the central regions and bluntly pointed in the polar regions. The septa are planar, and only folded in the polar extremities, but more than in Schubertella. The proloculus is spherical. The first whorl is deviated, like many schubertellids. Moderate chomata are present in all of the whorls. The tunnel is low, but relatively wide. The wall is typically schubertelloid, with a dark tectum and yellowish primatheca. Septal pores are conspicuous. The aperture is terminal and simple. Measurements: D = 500–700 μm; w = 1000 μm; w/D = 2.00; number of whorls = 4–5; proloculus diameter = 20 μm; h = 100–170 μm; s = 50 μm.

Remarks

As indicated by Ueno and Sakagami (Reference Ueno and Sakagami1993), this species is transitional between Schubertella and Neofusulinella. However, due to the symmetrical, fusiform shape, the species closely resembles Neofusulinella. Comparisons with Neofusulinella giraudi were indicated by Sheng (Reference Sheng1963) and Igo et al. (Reference Igo, Rajah and Kobayashi1979) (e.g., smaller w/D ratio, thicker wall, and stronger chomata).

Genus Mesoschubertella Kanuma and Sakagami, Reference Kanuma and Sakagami1957 emend. Rozovskaya, Reference Rozovskaya1975

Type species

Mesoschubertella thompsoni Kanuma and Sakagami, Reference Kanuma and Sakagami1957, by original designation.

Other species

See Rozovskaya (Reference Rozovskaya1975); Leven et al. (Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992); Ueno (Reference Ueno1996); and Davydov (Reference Davydov2011).

Diagnosis

Test small, subrhombic to fusiform, with strong chomata and polar folding relatively developed. Aperture terminal and simple with tunnel. Wall schubertelloid with primatheca.

Occurrence

Yakhtashian–Bolorian (= Artinskian–Kungurian) of the Paleotethyan and Panthalassan shelves (see Leven et al., Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992; Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam, Reference Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam2004; Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi2019).

Remarks

The type of wall of Mesoschubertella has been discussed by many authors. We follow the authors Rozovskaya, Reference Rozovskaya1975; Leven et al., Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992; Ueno, Reference Ueno1996; Davydov, Reference Davydov2011; and Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi2019, who consider Mesoschubertella as a taxon possessing a typical schubertellid wall with a primatheca, and not a keriothecal wall, as indicated by Kanuma and Sakagami (Reference Kanuma and Sakagami1957) and Loeblich and Tappan (Reference Loeblich and Tappan1987). Mesoschubertella and Schubertella have such a wall, therefore, the same microstructure; nevertheless, Mesoschubertella morphologically differs by its symmetrical shape, often rhombic, with strong chomata, and slightly more-developed septal folding. Mesoschubertella is relatively characteristic of the Kungurian/Bolorian.

Mesoschubertella spp.

Figure 4.7–4.11

Remarks

Representatives of this genus, although relatively abundant in our material, are left in open nomenclature due to the discussed definition of the genus. This genus is distinguished in the upper Yakhtashian of the Bagh-e Vang section (sample BA-4).

Genus Toriyamaia Kanmera, Reference Kanmera1956

Type species

Toriyamaia laxiseptata Kanmera, Reference Kanmera1956, by original designation.

Other species

See Kahler and Kahler (Reference Kahler and Kahler1966); Rozovskaya (Reference Rozovskaya1975); Leven et al. (Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992); Krainer et al. (Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019).

Diagnosis

Test involute, elongate fusiform, and asymmetrical with weakly deviated juvenarium. Adult stages loosely coiled. Planar septa only gently curved in the polar areas. Wall typical of schubertellid with primatheca. Chomata more distinct than in Schubertella.

Occurrence

?Sakmarian–Artinskian–Kungurian–Guadalupian of the Paleotethys and Panthalassa; very rare in the USA (Texas; Stewart, Reference Stewart1966).

Toriyamaia sp.

Figures 5.4, 10.9

Remarks

Rare sections in our material correspond to an undetermined species of Toriyamaia. Measurements: Diameter = 1400–2000 μm; w = 1300–3000 μm; w/D = 1.50. This taxon, in open nomenclature, was found in the upper Bolorian Misellina (Misellina) cf. M. (M.) termieri Zone of the Bagh-e Vang and Shesh Anghost sections (samples BA-47 and SHB-14).

Family Biwaellidae Davydov, Reference Davydov1984 nom. translat. Leven in Leven et al., Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992

Occurrence

Late Pennsylvanian–upper Cisuralian; rare, but probably cosmopolitan.

Remarks

Test schubertelliform, inflated fusiform to elongate fusiform, or subcylindrical, with an inconspicuous juvenarium. Septa weakly folded. Chomata diversely developed. Wall initially dark microgranular becoming porous, perforated and falsely keriothecal in adult whorls. Aperture terminal, simple.

Genus Biwaella Morikawa and Isomi, Reference Morikawa and Isomi1960

Type species

Biwaella omiensis Morikawa and Isomi, Reference Morikawa and Isomi1960, by original designation.

Other species

See Kahler and Kahler (Reference Kahler and Kahler1966); Rozovskaya (Reference Rozovskaya1975); Leven et al. (Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992); Davydov (Reference Davydov2011); and Krainer et al. (Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019).

Diagnosis

Test moderately large and elongate fusiform. Proloculus relatively small, juvenarium absent. Septa planar to slightly folded in the poles. Wall pseudokeriothecal with tectum. Central aperture with tunnel and asymmetrical chomata.

Occurrence

Gzhelian–Cisuralian (Davydov, Reference Davydov2011) or mid-Asselian–lower Bolorian (Leven et al., Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992), cosmopolitan. The Gzhelian–Asselian forms assigned to Biwaella often belong to Oketaella because the acme of true Biwaella is generally Sakmarian and Yakhtashian. Moreover, Pasini (Reference Pasini1965, p. 85) indicated that Oketaella and Biwaella may be two generations, megalo- and microspheric, of the same genus. In our opinion, the relationship of both genera is justified, and several species of Biwaella in the literature more probably belong to Oketaella (see Krainer et al., Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019, p. 70). Rare Bolorian Biwaella were mentioned by Leven et al. (Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992) and Leven (Reference Leven1993b).

Biwaella sp.

Figure 6.3

Remarks

Test elliptical with sparsely located chomata and relatively developed septal folding. D = 1300 μm; w = 2000 μm; w/D = 1.53; proloculus diameter = 40 μm; number of whorls = 5. A few specimens were found in the upper Yakhtashian of the Bagh-e Vang section (sample BA-4).

Superfamily Schwagerinoidea Solovieva, Reference Solovieva1978 (as Schwagerinacea)

Family Triticitidae Davydov, Reference Davydov1986 nomen translat. Rauzer-Chernousova et al., Reference Rauzer-Chernousova, Bensh, Vdovenko, Gibshman, Leven, Lipina and Chediya1996

Subfamily Darvasitinae Leven in Leven, Leonova, and Dmitriev, Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992 nom. translat. Herein

Genus Darvasites Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1959

Subgenus Alpites Davydov, Krainer, and Chernykh, Reference Davydov, Krainer and Chernykh2013

Type species

Fusulina contracta Schellwien in Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth, Reference Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth1909, by original designation.

Diagnosis

Test medium sized and subcylindrical fusiform with slightly convex lateral slopes and bluntly rounded poles. Small to medium spherical proloculus. No individualized juvenarium, but the first whorls are more tightly coiled. Septal folding developed in lateral zones, absent in central zones. Chomata small and asymmetrical. Tunnel has more or less regular path. Axial filling faint or absent. Wall shows fine keriotheca.

Occurrence

Upper Asselian of Turkey (Kobayashi and Altıner, Reference Kobayashi and Altıner2008); Lower Sakmarian of the Urals (Grozdilova and Lebedeva, Reference Grozdilova and Lebedeva1961); Hermagorian–Bolorian (= Sakmarian–Kungurian in the Paleotethys; Davydov et al., Reference Davydov, Krainer and Chernykh2013) of South China (Chen, Reference Chen1934; Zhou, Reference Zhou1998), Japan (Nogami, Reference Nogami1961; Choi, Reference Choi1973), Vietnam (Saurin, Reference Saurin1954), Malaysia (Vachard, Reference Vachard1990), NE Thailand (Igo et al., Reference Igo, Ueno and Sashida1993), Sumatra (Vachard, Reference Vachard1989), North China (Han, Reference Han1975), Tarim (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Han and Wang1984), Pamirs (Leven, Reference Leven1967), Darvaz (Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1949; Leven and Shcherbovich, Reference Leven and Shcherbovich1980; Leven, Reference Leven1998), Afghanistan (Leven, Reference Leven1997), Iran (Kahler, Reference Kahler1976; Lys et al., Reference Lys, Stampfli and Jenny1978; Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam, Reference Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam2004), Turkey (Leven, Reference Leven1995; Leven and Okay, Reference Leven and Okay1996; Okuyucu, Reference Okuyucu1999), Hungary (Bérczi-Makk and Kochansky-Devidé, Reference Bérczi-Makk and Kochansky-Devidé1981), Croatia (Kochansky-Devidé, Reference Kochansky-Devidé1955, Reference Kochansky-Devidé1964, Reference Kochansky-Devidé1970; Ramovš and Kochansky-Devidé, Reference Ramovš and Kochansky-Devidé1965; Kochansky-Devidé and Ramovš, Reference Kochansky-Devidé and Ramovš1966), Sicily (Carcione et al., Reference Carcione, Vachard, Martini, Zaninetti, Abate, Lo Cicero and Montanari2004), and Carnic Alps (Kahler and Kahler, Reference Kahler, Kahler and Flügel1980; Kahler, Reference Kahler, Ebner and Kahler1989; Davydov et al., Reference Davydov, Krainer and Chernykh2013; Krainer et al., Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019). Alpites is currently unknown in the Americas; however, some forms are relatively similar to Alpites, such as Pseudofusulinoides pusillus and P. aff. P. changi (Schellwien, Reference Schellwien1898) sensu Vachard et al., Reference Vachard, Vidaurre-Lemus, Fourcade and Requeña2000c in Guatemala and “Schwagerina” tintensis Roberts in Newell, Chronic, and Roberts, Reference Newell, Chronic and Roberts1953, in Peru.

Darvasites (Alpites) sinensis (Chen, Reference Chen1934)

Figure 10.16

- Reference Chen1934

Triticites sinensis Chen, p. 36, pl. 7, figs. 8, 12.

- Reference Saurin1954

Triticites cf. sinensis; Saurin, p. 10, pl. 1, figs. 28, 29.

- Reference Rozovskaya1958

Triticites (Rauserites) sinensis; Rozovskaya, p. 100, pl. 8, figs. 8, 9.

- Reference Kahler and Kahler1966

Triticites sinensis; Kahler and Kahler, p. 524.

- Reference Rozovskaya1975

Nagatoella (Darvasites) sinensis; Rozovskaya, p. 163.

- Reference Zhou1982

Darvasites sinensis; Zhou, p. 244, pl. 4, figs. 5–8.

- Reference Xie1982

Darvasites sinensis; Xie, p. 23, pl. 9, figs. 4–7.

- Reference Xiao, Wang, Zhang and Dong1986

Darvasites sinensis; Xiao et al., p. 144, pl. 2, fig. 23.

- Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992

Darvasites sinensis; Leven in Leven et al., p. 86, pl. 11, figs. 10, 11.

- Reference Leven1995

Darvasites sinensis; Leven, p. 238, pl. 1, fig. 9.

- Reference Zhou1998

Darvasites sinensis; Zhou, pl. 1, fig. 11.

Lectotype

We herein designate as lectotype the axial section (No. 3262, Research Institute of Geology, Academia Sinica, Nanking) from the Permian Swine Limestone, Chuanshan, southern Kiangsu, China (Chen, Reference Chen1934, pl. 7, fig. 8).

Occurrence

Yakhtashian–Bolorian (= Artinskian–Kungurian) of the Paleotethyan and Panthalassan shelves. It is found in the lower Bolorian Misellina (Brevaxina) dyhrenfurthi Zone of the Shesh Anghost section (sample SHB-1).

Description

This species is ellipsoidal and relatively large for the genus. The chomata begin to show the regular arrangment of those of Darvasites, which is the descendent of Alpites. Measurements: w = 4000–6220 μm; D = 2100–3090 μm; w/D = 1.90–2.0; number of whorls = 9; proloculus diameter = 60 μm; h = 300 μm; s = 80 μm.

Remarks

In their morphology and dimensions, our specimens are similar to the lectotype of Chen (Reference Chen1934), designated herein.

Darvasites (Alpites?) sp.

Figure 5.9

Remarks

An oblique section with a diameter of 2500 μm in our material could be a representative of this subgenus. Rare specimens were found in the upper Yakhtashian of the Bagh-e Vang section (sample BA-4).

Family Schwagerinidae Dunbar and Henbest, Reference Dunbar and Henbest1930

Subfamily Schwagerininae Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1953.

Genus Sakmarella Bensh and Kireeva in Bensh, Reference Bensh1987

Type species

Fusulina moelleri Schellwien, Reference Schellwien1908, by original designation.

Other species

See Bensh (Reference Bensh1987).

Diagnosis

Test large and moderately to strongly elongate fusiform with tighter internal volution. Polar extremities smooth and rounded. Septal folding strong and developed in the entire chamber. Tunnel absent. Axial filling absent or weakly developed. Phrenothecae present.

Occurrence

Sakmarian of Central Pamir (Leven, Reference Leven1993a); upper Sakmarian of Central Afghanistan (Vachard, Reference Vachard1980; Vachard and Montenat, Reference Vachard and Montenat1981; Leven, Reference Leven1997); upper Asselian–lower Sakmarian of Pre-Urals, South Urals, and Precaspian Basin (Schellwien, Reference Schellwien1908; Korzhenevskiy, Reference Korzhenevskiy1940; Leven, Reference Leven1993a); Sakmarian–Kungurian of NW Pakistan (Leven, Reference Leven2010); Cisuralian of South China (Chen and Wang, Reference Chen and Wang1978) and the Carnic Alps (Davydov et al., Reference Davydov, Krainer and Chernykh2013); Wolfcampian of the USA (Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, California; Thompson, Reference Thompson1954; Skinner and Wilde, Reference Skinner and Wilde1965a; Kahler and Kahler, Reference Kahler and Kahler1966).

Remarks

This genus has been discussed for a long time, and there are several partial synonyms of Sakmarella (see Davydov et al., Reference Davydov, Krainer and Chernykh2013; Krainer et al., Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019), the species of which were previously assigned to the following taxa: Nonpseudofusulina; Pseudofusulina (part., especially in Leven, Reference Leven1993a); Schwagerina (part.); Fusulina (part.); Daixina (part.); and Paraschwagerina (part.).

Remarks

Our sections are too oblique to provide precise species names; hence, they are only compared with known species (such as S. cf. S. fluegeli and S. cf. S. implicata) or remain in open nomenclature. Specimens occur in the upper Yakhtashian Pamirina darvasica and Sakmarella spp. Zone of the Bagh-e Vang section and in the lower Bolorian Misellina (Brevaxina) dyhrenfurthi Zone and the mid-Bolorian Cuniculinella Zone of the Shesh Anghost section (samples BA-4, BA-5, BA-47, SHB-1, and SHB-6).

Genus Chalaroschwagerina Skinner and Wilde, Reference Skinner and Wilde1965a

Type species

Chalaroschwagerina inflata Skinner and Wilde, Reference Skinner and Wilde1965a, by original designation.

Other species

See Choi (Reference Choi1973), Bensh (Reference Bensh1987), Zhou (Reference Zhou1989), Leven et al. (Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992); Leven (Reference Leven1997), Vachard et al. (Reference Vachard, Martini and Zaninetti2001b), and Krainer et al. (Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019).

Diagnosis

Test inflated fusiform to globular and constantly bilaterally symmetrical, often strongly vaulted in median part, with poles rounded to bluntly pointed. Proloculus moderate to large, spherical to reniform. No true juvenarium, but 0.5–2 initial whorls are often more tightly coiled and followed by later, loosely coiled whorls. Septa strongly fluted and form rounded to triangular loops that reach three-quarters of the chamber height. Cuniculi absent. Axial filling absent or very weak. Weak chomata on the proloculus and absent in the later whorls. Low and narrow tunnel and diversely developed phrenothecae and septal pores. Wall composed of a tectum and an alveolar keriotheca.

Occurrence

Cosmopolitan (see e.g., Leven, Reference Leven1995, Reference Leven1998, and Vachard et al., Reference Vachard, Martini and Zaninetti2001b) and known from Sakmarian–Kungurian of Uzbekistan (Darvaz; Leven et al., Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992, Reference Leven, Gaetani and Schroeder2007), Pakistan (Leven, Reference Leven2010), Malaysia (Fontaine et al., Reference Fontaine, Bin Amnan and Vachard1999), Sumatra (Nguyen Duc Tien, Reference Nguyen Duc Tien1986), South China (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Sheng and Wang1987; Zhou, Reference Zhou1989) and western Yunnan (Ueno et al., Reference Ueno, Wang and Wang2003), East Siberia (Davydov et al., Reference Davydov, Belasky and Karavayeva1996), Mexico (Chiapas) (Thompson and Miller, Reference Thompson and Miller1944; Vachard et al., Reference Vachard, Flores de Dios, Pantoja, Buitrón, Arellano and Grajales2000b), southern Chile (Douglass and Nestell, Reference Douglass and Nestell1976), and the Carnic Alps (Davydov et al., Reference Davydov, Krainer and Chernykh2013; Krainer et al., Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019).

Remarks

Before being formally described, this genus was assigned to the following taxa: Pseudofusulina (part), Schwagerina (part.), and Taiyuanella (part.); see discussion in Krainer et al. (Reference Krainer, Vachard and Schaffhauser2019).

Chalaroschwagerina sp.

Figure 6.2

Remarks

Rare Chalaroschwagerina have been observed in our material, but not determined because they are oblique sections. They were found in the upper Yakhtashian of the Bagh-e Vang section (sample BA-4).

Genus Chalaroschwagerina?

Remarks

This form is transitional between true Chalaroschwagerina and Cuniculinella emend. Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi2019 (= Cuniculina Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam, Reference Leven and Vaziri Moghaddam2004) because it has the rhombic form septal folding of the former, but does not exhibit cuniculi. It is recognized in the upper Yakhtashian of eastern Paleotethys (see the synonymy lists of the two species described below).

Chalaroschwagerina? vulgaris (Schellwien in Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth, Reference Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth1909)

Figures 10.11, 13.5, 13.6, 14.1

- Reference Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth1909

Fusulina vulgaris Schellwien in Schellwien and Dyrhenfurth, p. 163, pl. 14, figs. 1, 2.

- Reference Ozawa1925

Schellwienia vulgaris; Ozawa, p. 23, pl. 7, fig. 3.

- Reference Likharev and Likharev1939

Schwagerina vulgaris; Likharev, p. 39, pl. 2, figs. 7–9.

- Reference Miklukho-Maklay1949

Pseudofusulina vulgaris; Miklukho-Malay, p. 87, pl. 8, figs. 2, 3, pl. 9, figs. 1–3.

- Reference Kalmykova1967

Pseudofusulina vulgaris; Kalmykova, p. 179, pl. 8, figs. 1–6.

- Reference Ota1977

Pseudofusulina vulgaris; Ota, pl. 2, figs. 7, 8.

- Reference Liu, Xiao and Dong1978

Pseudofusulina vulgaris; Liu, Xiao, and Dong, p. 58, pl. 12, fig. 2.

- Reference Zhang1982

Pseudofusulina vulgaris; Zhang, p. 177, pl. 15, figs. 2, 5, 6, 8.

- Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992

Chalaroschwagerina vulgaris; Leven in Leven et al., p. 91, pl. 14, figs. 5–7.

- Reference Ueno1992

Chalaroschwagerina vulgaris; Ueno, fig. 3.1–3.4.

- Reference Leven1997

Chalaroschwagerina vulgaris; Leven, p. 67, pl. 10, figs. 1, 2.

- Reference Leven1998

Chalaroschwagerina vulgaris; Leven, pl. 4, figs. 2, 4.

- Reference Zhou1998

Chalaroschwagerina vulgaris; Zhou, pl. 3, fig. 11.

- Reference Leven and Özkan2004

Chalaroschwagerina vulgaris; Leven and Özkan, pl. 2, figs. 12, 13.

Lectotype

Axial section (Geologisches Institut, Königsberg, Germany, currently Kaliningrad, Russia; catalogue number not given) from Permian of Obi-Niou river, Darvaz, Uzbekistan (Schellwien in Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth, Reference Schellwien and Dyhrenfurth1909, pl. 14, fig. 1; subsequently designated by Toriyama, Reference Toriyama1958, p. 167).

Occurrence

Upper Yakhtashian of Darvaz, Afghanistan, South China, Japan (see references in Leven et al., Reference Leven, Leonova and Dmitriev1992; Ueno, Reference Ueno1992). It is found in the mid-Bolorian Cuniculinella Zone of the Shesh Anghost section (samples SHB-4 and SHB-9).

Description

Test relatively large and subglobular with highly vaulted median portion and blunt poles. Proloculus spherical. Initial two whorls tightly coiled, adult whorls loosely coiled. Septa intensively fluted. Thin phrenothecae. Chomata absent. Tunnel indistinct. Measurements: w = 6000–7855 μm; D = 2000–6000 μm; w/D = 1.52–1.67; proloculus diameter = 200– 310 μm; number of whorls = 5; s = 100 μm.

Remarks