Introduction

Microconchids are an extinct group of generally small (cf. Zatoń and Mundy, Reference Zatoń and Mundy2020) tubeworms, which appeared during the Late Ordovician and disappeared from the fossil record at the end of the Middle Jurassic (e.g., Taylor and Vinn, Reference Taylor and Vinn2006; Vinn and Taylor, Reference Vinn and Taylor2007; Zatoń and Vinn, Reference Zatoń and Vinn2011). Based on superficial resemblance to Recent serpulid polychaete tubes, microconchids were often misidentified as Spirorbis Daudin, Reference Daudin1800 or Serpula Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1758 (e.g., Howell, Reference Howell1964; Beus, Reference Beus1980), or as ‘vermiform’ gastropods (Burchette and Riding, Reference Burchette and Riding1977; Bełka and Skompski, Reference Bełka and Skompski1982). However, due to their completely different tube characteristics (i.e., bulbous larval shell, microlamellar and punctate tube), Weedon (Reference Weedon1990, Reference Weedon1991, Reference Weedon1994) assigned the tubeworms to the tentaculitoids, and included them in a separate order Microconchida.

Microconchids first appeared in fully marine environments but colonized brackish habitats as early as the early Silurian (Brower, Reference Brower1975), and freshwater environments during the Early Devonian (Schweitzer, Reference Schweitzer1983; Caruso and Tomescu, Reference Caruso and Tomescu2012; see also Taylor and Vinn, Reference Taylor and Vinn2006; Zatoń et al., Reference Zatoń, Vinn and Tomescu2012a). They were also a common constituent of microbial buildups (Peryt, Reference Peryt1974; Burchette and Riding, Reference Burchette and Riding1977; Toomey and Cys, Reference Toomey and Cys1977; Dreesen and Jux, Reference Dreesen and Jux1995; He et al., Reference He, Wang, Woods, Li, Yang and Liao2012) and metazoan buildups (Pruss et al., Reference Pruss, Payne and Bottjer2007; Brayard et al., Reference Brayard, Vennin, Olivier, Bylund, Jenks, Stephen, Bucher, Hofmann, Goudemand and Escarguel2011), and in some cases formed their own bioherms (Beus, Reference Beus1980; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Vinn and Yancey2011; Zatoń et al., Reference Zatoń, Niedźwiedzki, Rakociński, Blom and Kear2018). Microconchids are the dominant, or even sole, encrusters in the aftermaths of some of the mass extinctions, and thus they are widely considered as an opportunistic, ‘disaster’ taxon (Fraiser, Reference Fraiser2011; Zatoń and Krawczyński, Reference Zatoń and Krawczyński2011a; He et al., Reference He, Wang, Woods, Li, Yang and Liao2012; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Chen, Wang, Ou, Liao and Mei2015, Reference Yang, Chen, Mei and Sun2021; Zatoń et al., Reference Zatoń, Niedźwiedzki, Blom and Kear2016a; Shcherbakov et al., Reference Shcherbakov, Vinn and Zhuravlev2021).

As encrusting organisms, microconchids colonized mainly firm and hard substrata, e.g., shells, cobbles, and hardgrounds in marine settings (Vinn and Wilson, Reference Vinn and Wilson2010; Zatoń and Borszcz, Reference Zatoń and Borszcz2013; Zatoń et al., Reference Zatoń, Zhuravlev, Rakociński, Filipiak, Borszcz, Krawczyński, Wilson and Sokiran2014a). They also colonized plant remains in brackish to freshwater environments (Caruso and Tomescu, Reference Caruso and Tomescu2012; Zatoń et al., Reference Zatoń, Grey and Vinn2014b; Shcherbakov et al., Reference Shcherbakov, Vinn and Zhuravlev2021) utilizing different strategies (Vinn, Reference Vinn2010). On such substrates, the majority of microconchids cemented their tubes (e.g., Vinn and Taylor, Reference Vinn and Taylor2007), with only their terminal parts elevated above the substratum (e.g., Zatoń and Krawczyński, Reference Zatoń and Krawczyński2011a, Reference Zatoń and Krawczyńskib). In some species, especially in those forming organic buildups, the larval shell (the planispirally coiled initial part of the tube) was cemented and the rest of the tube was helically uncoiled and oriented upward (Burchette and Riding, Reference Burchette and Riding1977; Beus, Reference Beus1980; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Vinn and Yancey2011). Permian Helicoconchus Wilson, Vinn, and Yancey, Reference Wilson, Vinn and Yancey2011 from Texas, unlike any other species described, was able to bud new tubes from the parent tube (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Vinn and Yancey2011). Commonly, microconchid tubes are loosely scattered in sedimentary layers, a pattern that indicates that in many cases the tubes were transported from their original habitats (e.g., Suttner and Lukeneder, Reference Suttner and Lukeneder2004). In other cases, the tubes were detached from degraded organic substrata, e.g., algae, or dissolved aragonitic shells that they encrusted (e.g., Zatoń and Peck, Reference Zatoń and Peck2013).

Herein, we document Devonian microconchids that are abundantly preserved as isolated specimens in mixed siliciclastic and carbonate deposits, but that possess skeletal features of certain ecological adaptations not previously noted in these taxa. The novel structures have implications for the paleobiology, phylogenetic relationships, and evolutionary paleoecology of this still enigmatic group of tentaculitoids. We discuss their evolution, linked to the repeated development of eustatically driven, brackish water estuarine settings—episodes that were unique to the ancient Rocky Mountain region of Laurentia in the Devonian. A palynologic analysis provides an age constraint for the fossils and supports our interpretation of a brackish estuarine paleoenvironment.

Location, geologic and depositional setting

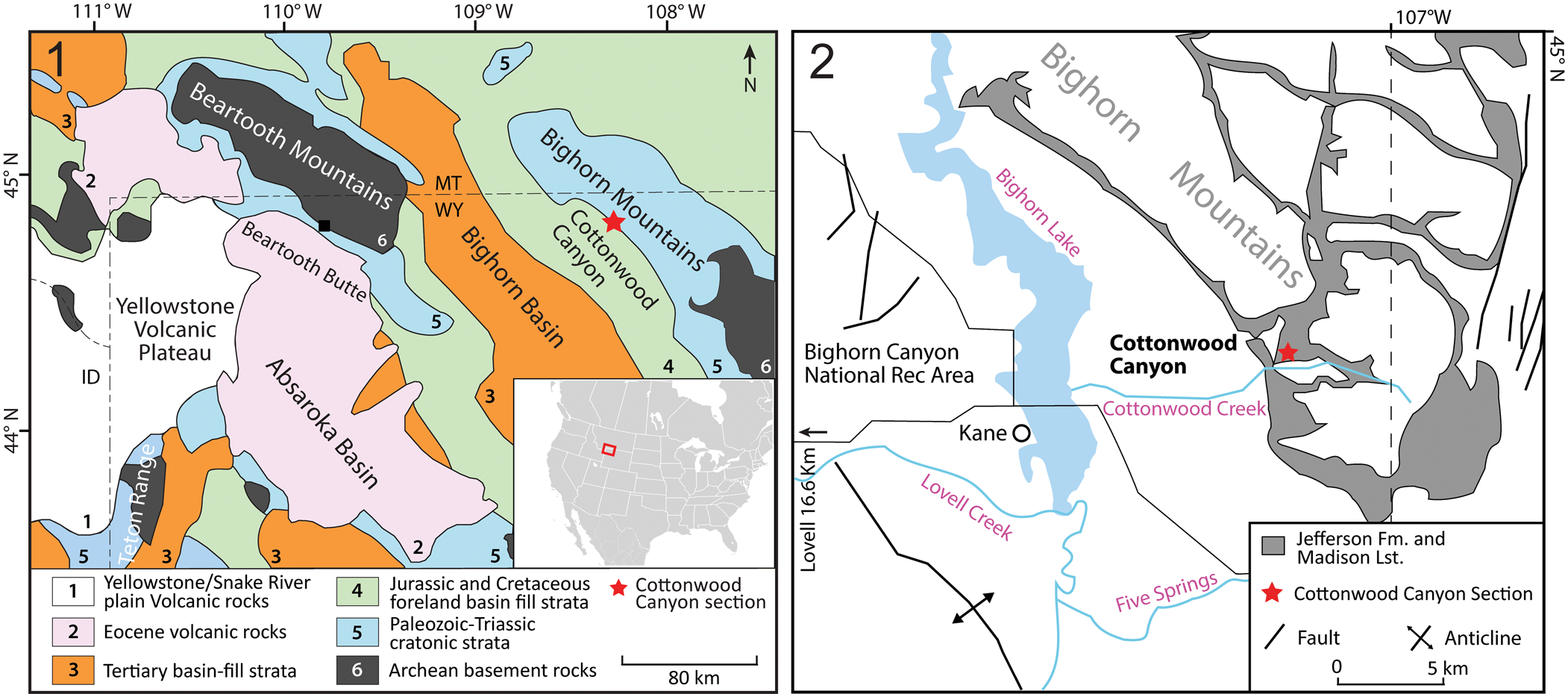

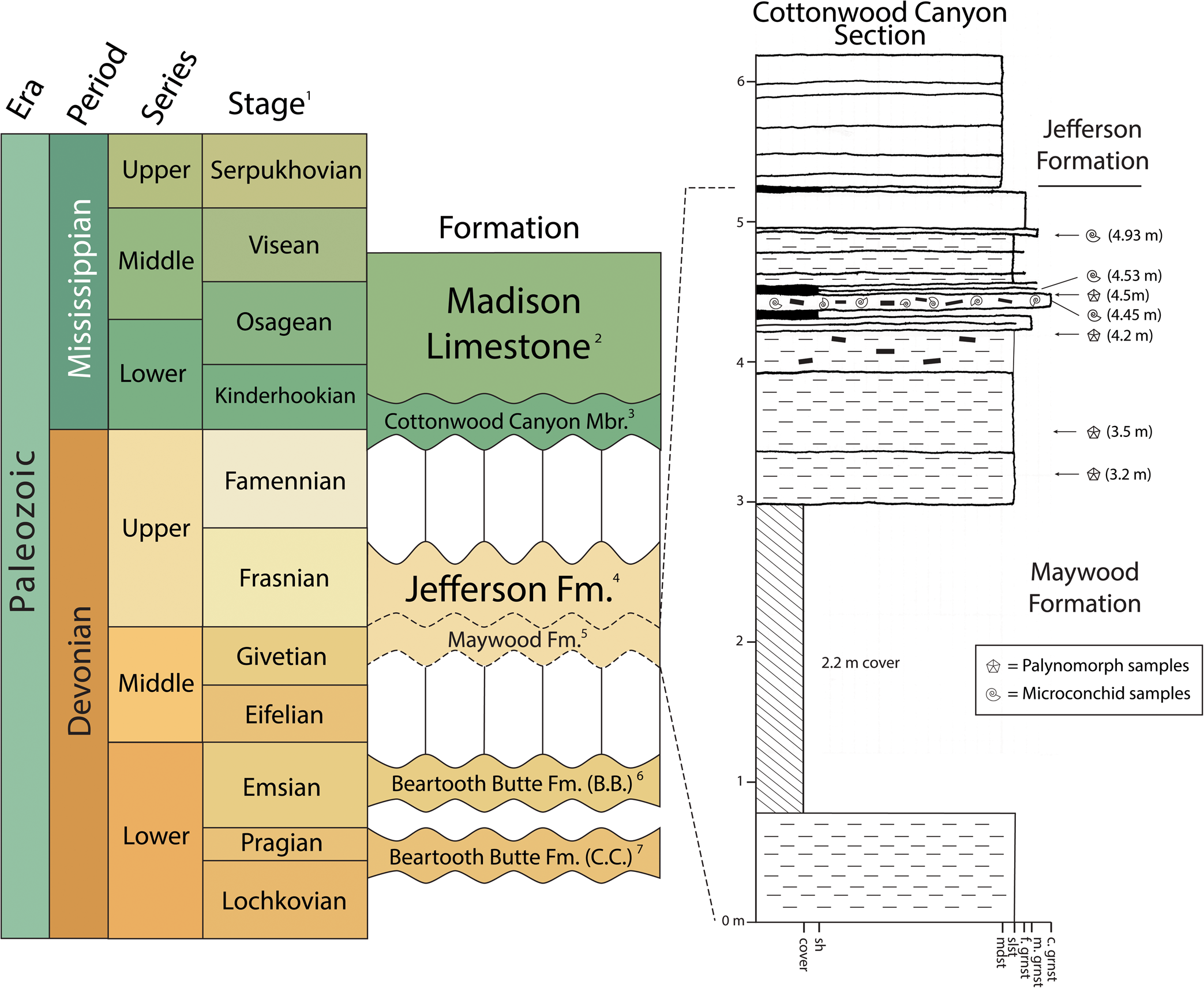

Samples for this study were collected at Cottonwood Canyon, Wyoming, USA (Fig. 1), on the western side of the northern Bighorn Mountains, ~28 km to the east of Lovell, Wyoming. The study area is ~0.7 km into the canyon on the northern wall. At this site, a thick (33.6 m), narrow channel-fill of the Lower Devonian Beartooth Butte Formation rests on the Upper Ordovician Bighorn Formation. This is overlain by a laterally extensive, 10.2 m thick covered interval. Sandberg (Reference Sandberg1961) interpreted a covered interval at the same stratigraphic level in his section < 1 km to the southeast as the fine-grained upper Beartooth Butte Formation. We measured a section through the Maywood Formation (44°52′14.0″N, 108°03′26.5″W) that rests directly on the Bighorn Formation outside of the Beartooth Butte Formation channels (i.e., on an interfluve). The Maywood Formation is 5.24 m, including a 2.2 m thick covered interval near the base (Fig. 2). The Maywood is overlain by the Jefferson Formation along a rapidly gradational contact interval (Fig. 3).

Figure 1. Location of the sampled site: (1) generalized geologic map of northern and northeastern Wyoming, showing the study site at Cottonwood Canyon, Wyoming (adapted from Malone et al., Reference Malone, Welch, Foreman and Craddock2017); (2) generalized geologic map of Cottonwood Canyon area, Wyoming (adapted from Pierce and Nelson, Reference Pierce and Nelson1971).

Figure 2. Devonian and Mississippian chronostratigraphic framework and stratigraphic units (left) and generalized stratigraphic column of Maywood Formation at Cottonwood Canyon, Wyoming (right). Chronostratigraphy of Devonian and Mississippian from Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Harper and Gibbard2020). Vertical lines represent depositional hiatus between formations; dashed, wavy lines at base and top of Maywood Formation indicate uncertain ages of the unit. The vertical axis next to the stratigraphic column represents stratigraphic height (in meters). The numbers on the right indicate stratigraphic heights where microconchid and palynomorph samples were taken. Superscripts: 1 = North American stages (Kinderhookian and Osagean) are used for Lower Mississippian stages instead of Tournaisian; 2 = Peterson, Reference Peterson1981; 3 = Sandberg, Reference Sandberg1967; 4 = Sandberg, Reference Sandberg1963; 5 = Sandberg, Reference Sandberg1963; 6 = Beartooth Butte (B.B.), Wyoming; 7 = Cottonwood Canyon (C.C.), Wyoming. Vertebrate fossils by Elliot and Johnson (Reference Elliot, Johnson, Klapper, Murphy and Talent1997) and spore fossils by Tanner (Reference Tanner1984) and Noetinger et al. (Reference Noetinger, Bippus and Tomescuin press) indicate different ages of two exposures of the Beartooth Butte Formation: Late Lochkovian–Pragian at Cottonwood Canyon, middle–late Emsian at Beartooth Butte. Strata: black = plant debris and coal fragments; fine dashes = minor clay component; thick dashes = plant material; crosshatch = cover. c. grnst = coarse grainstone; f. grnst = fine grainstone; m. grnst = medium grainstone; mdst = carbonate mudstone; sh = shale; slst = calcisiltite

Figure 3. Maywood and Jefferson formations at Cottonwood Canyon, Wyoming: (1) red, fine-grained strata of the upper Maywood Formation and contact with the thin to medium bedded dolomudstone of the basal Jefferson Formation; (2) close-up of contact interval showing brown to gray calcisiltite and dolosiltite beds of the uppermost Maywood. Two mm thick layers of microconchids are indicated by black arrows. Scale = hammer ~33 cm (1); pencil ~14 cm (2).

The Beartooth Butte and Maywood formations are interpreted to represent infills of incised valleys that eroded into underlying rocks, primarily the Bighorn Dolomite, with deposition at different times during the Devonian (Dorf, Reference Dorf1934; Sandberg, Reference Sandberg1961; Sandberg and McMannis, Reference Sandberg and McMannis1964): the Beartooth Butte Formation in the Lower Devonian (upper Lochkovian to Emsian, see Tanner, Reference Tanner1984; Elliot and Johnson, Reference Elliot, Johnson, Klapper, Murphy and Talent1997) and the Maywood during the Givetian. At our Cottonwood Canyon section, the Beartooth Butte channel rests on the Bighorn and includes a narrow, deeply incised part at the base. The basal part consists of red, very coarse, conglomeratic debris-flow deposits, and the upper part that filled a broader valley consists of fine-grained facies. Sandberg (Reference Sandberg1961) established a late Lochkovian to Pragian age for this fine-grained interval in his section at Cottonwood Canyon.

The unconformably overlying Maywood Formation channels were cut into both the Bighorn Dolomite and the upper Beartooth Butte Formation. The overlying Jefferson Formation is assigned to the Frasnian (Sandberg, Reference Sandberg1965) and consists of dolostone, dolomitic siltstone, and argillaceous dolomite. It is in turn overlain by the Mississippian Madison Limestone.

The Maywood Formation is considered an equivalent of the Souris River Formation in Montana (Kauffman and Earll, Reference Kauffman and Earll1963). Sandberg (Reference Sandberg1963) described the Maywood Formation at Cottonwood Canyon and noted the abundance of microconchids (attributed to Spirorbis) throughout his ~4.9 m (16 ft) section, located farther east within Cottonwood Canyon than the section we describe here. In our study site, the base of the formation consists of 80 cm of tan-weathering dolosiltite (Fig. 2). It is succeeded by a 2.2 m covered interval. The lower 1.22 m above the covered interval consists entirely of calcisiltite and dolosiltite. The rest of the formation (4.22–5.24 m) is better exposed and consists mostly of calcisiltite/dolosiltite facies, with a few shale and microconchid grainstone beds. The latter contains both complete and broken microconchid specimens, some of which are coated by pyrite. Some microconchid grainstone beds are also rich in fish remains, rounded coal pebbles, macroscopic plant impressions, macerated plant stems, and megaspores. A lower Upper Devonian age was assigned to the formation based on these spores and vertebrate fossils (Sandberg, Reference Sandberg1963).

The biota of the Maywood Formation in Cottonwood Canyon indicates a marginal marine environment, but whether the deposition was in brackish or fresh water remains uncertain based on microflora and fish fauna (Sandberg, Reference Sandberg1963). The strata at Cottonwood Canyon were interpreted to be deposited in the upper reaches of a long, narrow estuary that extended into a retreating shoreline whereas the Maywood Sea transgressed southward and westward from the Williston Basin, Montana (Sandberg, Reference Sandberg1963; Sandberg and McMannis, Reference Sandberg and McMannis1964). Many Maywood and associated Middle–Upper Devonian channel-fill deposits share similarities with the Lower Devonian Beartooth Butte Formation in channel geometry, lithology, and fossil assemblages. The Maywood Formation was noted to directly overlie the Beartooth Butte Formation in several stratigraphic sections, and deposition of both units took place within individual channels, which controlled and localized the Late Devonian transgression (Sandberg and McMannis, Reference Sandberg and McMannis1964).

Materials and methods

Our microconchid samples were collected from the middle and upper part of the Maywood Formation. The samples consist of fine to coarse grainstone collected from three stratigraphic horizons (samples 4.45, 4.53, and 4.93) of 3–4 mm thick grainstone beds.

The samples were first inspected with a Nikon SMZ 1000 binocular microscope, and subsequently sample fragments with selected specimens were imaged using a Philips XL30 environmental scanning electron microscope (ESEM) at the Institute of Earth Sciences, University of Silesia, Sosnowiec, Poland. The specimens were examined uncoated under low-vacuum conditions using back-scattered (BSE) imaging. Selected specimens were also documented using a Leica Wild M10 binocular microscope equipped with a Nikon NikCam Pro1 camera.

To better determine the age of the microconchid-bearing deposits and to decipher their paleoenvironments, four samples of organic-rich shale, calcareous shale, and calcisiltite (collected at 3.2 m, 3.5 m, 4.2 m, and 4.5 m; see Fig. 2) were subjected to palynological investigation. Standard palynologic maceration was followed using HCl (10%), HF (70%), and several washes of distilled water, allowing the neutralization of the residues, which were sieved using 5-μm meshes. Four slide mounts were made using a drop of residue mixed with one drop of polyvinyl alcohol. After drying, one drop of clear casting resin was added, and the cover slip turned and sealed. The residues were oxidized with 3 ml of Schultz solution in a hot bath for a short time, and after washing and centrifuging until neutralization, a 10% solution of NH4OH was added. The residues were then placed in a hot-water bath for two minutes and washed three or four times. Two sets of slides were created: one set with oxidized residues (3.5 m and 4.2 m) and another set with oxidized residues (3.2 m and 4.5 m) stained with a drop of Bismarck Brown Y. Microscopic analysis of the microfossils was performed using Nikon E200 and Leica DM500 light microscopes (bearing a fluorescence device), and images were taken with a Amuscope 14 Mp video camera.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

The specimens studied are housed at the Institute of Earth Sciences, University of Silesia, Sosnowiec, Poland (GIUS 4-3732). Palynological residues, slides, and extra rock samples are housed at Centro de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas de Transferencia a la Producción (CICYTIP-Pl; CICYTTP-CONICET-ER-UADER, of di Pasquo and Silvestri, Reference Di Pasquo and Silvestri2014).

Systematic paleontology

Class Tentaculita Bouček, Reference Bouček1964

Order Microconchida Weedon, Reference Weedon1991

Family Palaeoconchidae Zatoń in Zatoń & Olempska, Reference Zatoń and Olempska2017

Genus Aculeiconchus new genus

Type species

Aculeiconchus sandbergi n. gen. n. sp.

Diagnosis

Microconchid tubeworm having microlamellar tube structure, possessing hollow spines on its underside (base).

Etymology

Aculei (Latin) = spines; concha (Latin) = shell.

Occurrence

Maywood Formation, Middle Devonian (Givetian), Cottonwood Canyon, Wyoming, USA (44°52′14.0″N, 108°03′26.5″W).

Remarks

Aculeiconchus n. gen. differs from other described microconchids by the presence of spines on the tube base.

Aculeiconchus sandbergi new species

Figures 4–6

Figure 4. ESEM photomicrographs of Aculeiconchus sandbergi n. gen. n. sp. from the Devonian Maywood Formation, Wyoming: (1) dorsal side of planispirally coiled tube devoid of any spines, paratype, GIUS 4-3732/1; (2) tube underside with basal spines (arrows), paratype, GIUS 4-3732/2; (3) lateral view of holotype showing distinct basal spines, GIUS 4-3732/3; (4) detail of enlarged spine shown in (3); (5) tube underside with numerous hollow spines (arrows), paratype, GIUS 4-3732/4; (6) crushed tube with distinct basal spines in displaced, lateral positions, paratype, GIUS 4-3732/5.

Figure 5. ESEM photomicrographs of Aculeiconchus sandbergi n. gen. n. sp., paratypes, from the Devonian Maywood Formation, Wyoming: (1, 2) lamellar tube microstructure, GIUS 4-3732/6 (1) and 4-3732/9 (2); (3) tube underside with numerous, variously arranged but broken basal spines (arrows), GIUS 4-3732/7; (4) close-up of hollow basal spine preserved on the tube in (3, black arrow), showing its microlamellar structure.

Figure 6. Stereomicroscopic photographs of Aculeiconchus sandbergi n. gen. n. sp., paratypes, and its spines, Maywood Formation, Wyoming: (1) planispirally coiled tube with its uncoiled terminal part and basal spines of varying lengths (arrows), GIUS 4-3732/8; (2) basal spines dispersed loosely on the sediment (white arrows) and attached to the tube fragment (black arrow); (3) magnified long basal spine showing slight widening at its distal end.

Type specimens

Holotype (GIUS 4-3732/3) and paratypes (GIUS 4-3732/1, 2, 4–9) from Cottonwood Canyon, Wyoming, USA (44°52′14.0″N, 108°03’26.5”W), Maywood Formation, Middle Devonian (Givetian). Apart from the holotype and paratypes, other material comprises many variably preserved specimens embedded in the host rock of the Maywood Formation.

Diagnosis

Planispirally coiled tube with a tendency to helically uncoil; dorsal and lateral sides of tube covered by fine, transverse riblets; tube base with hollow spines of differing lengths.

Occurrence

Maywood Formation, Middle Devonian (Givetian), Cottonwood Canyon, Wyoming, USA (44°52′14.0″N, 108°03′26.5″W).

Description

Tube dextrally (clockwise) coiling planispirally (Fig. 4), to 1.97 mm diameter, in some cases distally helically uncoiled into upright direction (Fig. 6.1). Umbilicus open with rounded margin; aperture rounded, to 0.4 mm in diameter. The tube exterior shows dense, fine transverse riblets running from umbilical margin to tube base (Fig. 4.1, 4.3). Tube microstructure lamellar (Fig. 5.1, 5.2, 5.4); distinct deflections of the laminae seen in tube cross sections, indicating presence of pseudo- or punctuation, not detected. Only locally, some laminae show some deflection (Fig. 5.1), which potentially could point to presence of poorly developed (or poorly preserved) pseudopunctation.

Base of planispirally coiled tube rounded, with hollow spines of various lengths (Figs. 4.2–4.5, 5.3, 5.4). Spines projecting perpendicularly, or slightly obliquely, from tube base (Figs. 4.2, 4.3, 4.5, 6.1); arranged in single row or in irregular patterns with two spines on opposite sides of tube base (Figs. 4.5, 5.3); of varying length, with some as long as 0.7 mm (Fig. 6.3), circular to oval in cross section, but diameter can differ in single specimens (0.036–0.060 mm; in such cases, spine diameter increasing distally, forming flat base at top; Figs. 4.3, 6.3); ornamented with fine, transverse growth lines (Fig. 4.4); some with slight bending (Fig. 6.1); hollow inside; microlamellar structure not differing from that of tubes (Fig. 5.4); no spines observed on upper sides of tubes (Fig. 4.1).

Etymology

Named in honor of Charles A. Sandberg, an eminent Devonian expert who explored the area studied.

Remarks

The presence of lamellar tube structure lacking evident punctuation or pseudopunctation could indicate that Aculeiconchus sandbergi n. gen. n. sp. was either entirely devoid of such microstructural features or that these were poorly developed. Thus, for the moment, the species Aculeiconchus sandbergi n. gen. n. sp. is best included in the family Palaeoconchidae, to which the spine-bearing microconchids of Spinuliconchus Zatoń and Olempska, Reference Zatoń and Olempska2017 have also been assigned (see Zatoń and Olempska, Reference Zatoń and Olempska2017). With respect to external tube morphology and ornamentation, the new species described here could be like other microconchid species, e.g., Microconchus vinni Zatoń and Krawczyński, Reference Zatoń and Krawczyński2011b from the upper Givetian of the Holy Cross Mountains, Poland. However, Aculeiconchus sandbergi n. gen. n. sp. differs from all other described microconchid genera and species by its hollow spines located solely on the tube base. Two species of Devonian microconchids from the USA and Poland—Spinuliconchus angulatus (Hall, Reference Hall1861) (see Zatoń et al., Reference Zatoń, Wilson and Vinn2012b) and Spinuliconchus biernatae Zatoń and Olempska, Reference Zatoń and Olempska2017, respectively—possess short, hollow spines, but these are located exclusively on the dorsal and lateral sides of their tubes (Fig. 7). The latter species also comes from deposits of fully marine paleoenvironments, whereas the new species described here comes from estuarine, fresh to brackish water deposits. Because the basal spines present in the Maywood microconchids could have played a specific function different from those of Spinuliconchus spp. (see below), the erection of the new genus and species on the basis of these spines is fully justified.

Figure 7. SEM photomicrographs of Spinuliconchus biernatae Zatoń and Olempska, Reference Zatoń and Olempska2017 from the Lower Devonian of the Holy Cross Mountains, Poland: (1) tube in lateral view showing short hollow spines on its dorsal and lateral sides (arrows); (2) magnified hollow lateral spine.

For the moment, Aculeiconchus sandbergi n. gen. n. sp. is only known from the Devonian Maywood Formation of Wyoming and thus can be tentatively regarded as an endemic species. However, because microconchid tubeworms, and especially those from nonmarine deposits, are still poorly recognized, this genus and species could be found in other units in the future.

Microconchids, palynofacies and age of the Maywood Formation

The microconchid tubes are loose specimens in the host rock. Although the deposits also contain plant fragments, there is no clear evidence that microconchids encrusted them, as is the case of other assemblages associated with plants (e.g., Caruso and Tomescu, Reference Caruso and Tomescu2012; Zatoń et al., Reference Zatoń, Grey and Vinn2014b). In the Maywood Formation collections, only one microconchid was found adpressed to a plant fragment, whereas in the older Beartooth Butte Formation, tens of planispirally-coiled microconchids encrusted the plant remains of Drepanophycus Goeppert, Reference Goeppert1852 (see Caruso and Tomescu, Reference Caruso and Tomescu2012). In our samples, the tubes are both isolated from each other and densely packed. Depending on the sample, ~15–50 tubes are present within 1 cm2. The deposits are, in some cases, so rich in microconchid tubes that they form a ‘microconchid grainstone.’ The specimens are generally oriented parallel or oblique to bedding, and are commonly overturned. In some cases, the apertures of the helically uncoiled, distal parts of the tubes protrude from the layers and their openings are visible. In general, the specimens are relatively complete but can be flattened, and those tubes that are incomplete were probably broken during splitting of the rock samples. Some specimens are coated by iron oxides, most probably after pyrite weathering. The fossils could represent a mix of autochthonous and parautochthonous assemblages. Apart from microconchids and plant fragments, the deposits are also rich in phosphatic fish scales and teeth, some of which represent groups such as acanthodians, symmoriid chondrichthyans, and sarcopterygians (personal communication, M. Coates, 2021).

The four samples analyzed (Fig. 2) are dominated by amorphous organic matter (60–80%), but also contain a low-diversity assemblage of well-preserved trilete spores (15–30%), and low abundances of phytoclasts (tracheids) and indeterminate organic particles (5%). Pyrite (mostly euhedral) is present in low abundance in the exine of the spores, and embedded into algogenic organic matter (AOM) (fibrous, granular, and lumpy) that shows orange fluorescence (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Some biostratigraphically important and characteristic palynomorphs from the Maywood samples: (1) Geminospora lemurata Balme, Reference Balme1962 emend. Playford, Reference Playford1983, CICYTTP-Pl 2606-R-3823-2A-ox England Finder coordinates (EF) H16/4; (2) Geminospora lemurata Balme, Reference Balme1962 emend. Playford, Reference Playford1983, CICYTTP-Pl 2605-R-3823-1A EF M24/1 (tetrad); (3) Samarisporites triangulatus Allen, Reference Allen1965, CICYTTP-Pl 2606-R3823-2B EF P29/3; (4) Quadrisporites sp. indet., CICYTTP-Pl 2608-R3823-4A-ox EF M30/1; (5) Dictyotidium sp. indet., CICYTTP-Pl 2605-R3823-1C-ox EF O29; (6) amorphous organic matter under white light, CICYTTP-Pl 2607-R3823-3A EF O29; (7) algal colony revealed under flourescence not seen in (6), CICYTTP-Pl 2607-R3823-3A EF O29; (8, 9) G. lemurata and AOM lump under white light (8) and fluorescence (9), CICYTTP-Pl 2605-R3823-1A EF O29.

The samples are dominated by spores of Geminospora lemurata Balme, Reference Balme1962 emend. Playford, Reference Playford1983, along with some fragments of megaspores (Biharisporites parviornatus Richardson, Reference Richardson1965), and many tetrads (most frequently of G. lemurata). There are also some algal specimens in the 3.2 m sample that are identified as Dictyotidium sp. indet., Leiosphaeridia sp. indet., and Quadrisporites sp. indet.; some indeterminate forms are present in all four samples (Fig. 8).

The presence of the early–middle Givetian Geminospora lemurata (see Richardson and McGregor, Reference Richardson and McGregor1986; Streel et al., Reference Streel, Higgs, Loboziak, Riegel and Steemans1987; Avkhimovitch et al., Reference Avkhimovitch, Tchibrikova, Obukhovskaya, Nazarenko, Umnova, Raskatova, Mantsurova, Loboziak and Streel1993; Melo and Loboziak, Reference Melo and Loboziak2003; Breuer and Steemans, Reference Breuer and Steemans2013) and scarce specimens of the middle–late Givetian Samarisporites triangulatus Allen, Reference Allen1965 (e.g., Richardson and McGregor, Reference Richardson and McGregor1986; di Pasquo et al., Reference Di Pasquo, Amenábar and Noetinger2009; Noetinger and di Pasquo, Reference Noetinger and di Pasquo2011; Breuer and Steemans, Reference Breuer and Steemans2013; Turnau, Reference Turnau2014; Noetinger et al., Reference Noetinger, di Pasquo and Starck2018), documented in samples from 3.5 m (Fig. 2), indicates a middle Givetian age for the Maywood Formation.

Discussion

Spines in microconchids and their possible function

As mentioned above, in microconchid tubeworms, spines have been noted only in two formally described species that inhabited marine paleoenvironments: the Lower Devonian Spinuliconchus biernatae from Poland (Zatoń and Olempska, Reference Zatoń and Olempska2017) and Spinuliconchus angulatus from the Middle Devonian (Givetian) of the USA (Zatoń et al., Reference Zatoń, Wilson and Vinn2012b; Zatoń and Olempska, Reference Zatoń and Olempska2017). Spines are also visible in the hand drawing of the Middle Devonian microconchid ‘Spirorbis’ spinulifera ‘Hall,’ illustrated by Nicholson (Reference Nicholson1876), which could represent the genus Spinuliconchus. However, details of these spines are lacking.

In both Spinuliconchus species, the spines are short, located on the dorsal and lateral sides of the tube, and bent toward the aperture. They are more or less regularly spaced in a single row (Spinuliconchus angulatus) or several rows (Spinuliconchus biernatae) on the tube. In Spinuliconchus biernatae, the spines are present on both the planispirally coiled and uncoiled parts of the tube (Fig. 7). In both species, the spines are crescent-shaped or circular in cross section, and hollow. Spines located in these positions on encrusting microconchids could have functioned as antipredatory structures against small perpetrators (tiny fish or arthropods), or as antifouling devices impeding overgrowth by other encrusters. However, the optimal place for spines functioning as antipredatory structures would be in close proximity to the aperture from which the lophophore extruded. Spines located in such a position are present in, e.g., bryozoans, where they are sharp and pointed (Taylor and Lewis, Reference Taylor and Lewis2003; Taylor, Reference Taylor2020), in contrast to the rounded forms of the microconchids. Thus, in the case of the Spinuliconchus microconchids, the locations and arrangement of the spines better suggest an antiovergrowth function. In this respect, the spines could have served as natural obstacles hampering other epibionts from competitively overgrowing the microconchids. Similar hollow spines on some Late Ordovician and Silurian cornulitids (Vinn and Mutvei, Reference Vinn and Mutvei2005; Vinn and Eyzenga, Reference Vinn and Eyzenga2021), a group from which the microconchids are thought to be derived on the basis of similar skeletal features (Vinn and Mutvei, Reference Vinn and Mutvei2005, Reference Vinn and Mutvei2009; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Vinn and Wilson2010), could have played a similar function.

Formation, function, and phylogenetic significance of the basal spines of microconchids from Wyoming

The basal spines noted on the Devonian Maywood Formation Aculeiconchus n. gen. microconchids from Wyoming are very similar in shape and structure to spines located on the dorsal and lateral sides of tubes of Spinuliconchus microconchids, as discussed above. The basal spines of the Maywood specimens, however, in some cases are longer (to 700 μm versus 140 μm in Spinuliconchus biernatae), of greater diameter (~90 μm versus ~63 μm in Spinuliconchus biernatae), and distally wider. Also, unlike the dorsal and lateral spines of Spinuliconchus, the basal spines are oriented perpendicular to the tube base or are directed slightly obliquely, forward or backward of the aperture. Their lengths can differ in single individual fossils.

The overall similarity of the basal spines of the specimens of Aculeiconchus n. gen. to the dorsal and lateral spines of Spinuliconchus species, and the fact that the microlamellar structures of all of these spines and tubes are similar, clearly indicate that the formation mechanism of the dorsal/lateral spines in Spinuliconchus and the basal spines in Aculeiconchus n. gen. was the same. Moreover, as noted earlier by Zatoń et al. (Reference Zatoń, Wilson and Vinn2012b), the hollow spines of Spinuliconchus angulatus can be referred to as ‘tubular hollow’ spines, which are characteristic of siphonotretid and productide brachiopods (see Alvarez and Brunton, Reference Alvarez, Brunton, Brunton, Cocks and Long2001), but also exist in some lingulate brachiopods, e.g., Acathambonia portranensis Wright, Reference Wright1963 (see Wright and Nõlvak, Reference Wright and Nõlvak1997). Such spines in these brachiopods, as in Spinuliconchus microconchids, formed external ornamentation. According to Alvarez and Brunton (Reference Alvarez, Brunton, Brunton, Cocks and Long2001, p.109), tubular hollow spines grew from a separated bud of generative epithelium at the valve margin, which grew rapidly away from the valve surface, producing a complete tube of shell. Therefore, the spines in Spinuliconchus and the basal spines in the Maywood specimens of Aculeiconchus n. gen. formed in a similar manner (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Schematic section through the tube and basal spine of Aculeiconchus sandbergi n. gen. n. sp., showing that these hollow spines probably grew from a separated bud of epithelium at a tube margin, as in some brachiopods.

Interestingly, similarly hollow tubular projections also occur in some cyclostome bryozoans, e.g., Tubulipora andersonni Borg, Reference Borg1926. In these bryozoans, the tubes are in fact extensions of their exterior colony walls, and the spaces within the tubes are confluent with body cavities of the living chambers of feeding zooids (Boardman, Reference Boardman and Moore1983). Thus, tubular extensions in these bryozoans also formed in a similar way as the microconchid hollow spines. Taking the close phylogenetic relationships of microconchids and ‘lophophorates’ (a clade including phoronids, brachiopods, and bryozoans; see Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Vinn and Wilson2010; Taylor, Reference Taylor2020) into account, the acceptance of a similar formation mechanism for hollow spines in these groups is justified. Below, the position and interpreted function of the basal spines in Aculeiconchus n. gen. microconchids is compared with its spine-bearing brachiopod and bryozoan relatives. It is well known that tubular hollow spines in productide brachiopods—e.g., Horridonia horrida (Sowerby, Reference Sowerby1823) (see e.g., Kaźmierczak, Reference Kaźmierczak1967) and Levitusia humerosa (Sowerby, Reference Sowerby1822) (see Brunton, Reference Brunton1982) —served to stabilize shells on the soft sea bottom. The spines of chonetidine brachiopods served the same purpose, allowing them to survive in higher energy paleoenvironments (Mills and Leighton, Reference Mills and Leighton2008). The productide brachiopod Heteralosia slocomi King, Reference King1938 used its prominent hollow spines for attachment, i.e., for clasping and cementing to other objects (Pérez-Huerta, Reference Pérez-Huerta2013). The basal spines of the Aculeiconchus n. gen. microconchids could have been potentially used for anchoring the microconchid tube, providing additional stabilization in unconsolidated sediment, as in some productide brachiopods. The different lengths of the basal spines, noted in the Aculeiconchus n. gen. tubes and as broken specimens scattered loosely in the strata (Fig. 6.2, 6.3), indicate that they could have been elongated during the organism's life. The variable lengths, and the spines’ flat and widened terminations, could have enhanced stabilization on the substratum (Fig. 10.1). As with some brachiopods, spine lengthening could have been possible due to the presence of epithelium within the spines, and proliferation of generative zones that secreted the tube material at the distal end of the spines (Brunton, Reference Brunton1976; Alvarez and Brunton, Reference Alvarez, Brunton, Brunton, Cocks and Long2001; Pérez-Huerta, Reference Pérez-Huerta2013). However, such a mode of life is unusual in microconchids, because the great majority of species are known to have cemented to hard, firm substrata along planispirally coiled tubes, and no species described to date possess basal spines. Of course, not all previously described microconchids had a fully encrusting mode of life, e.g., Spathioconchus weedoni Zatoń et al., Reference Zatoń, Niedźwiedzki, Blom and Kear2016a from the Lower Triassic of Greenland, which coped well with soft bottom sediment. However, this species had a unique, nearly straight tube which, following larval attachment to any small, hard particle, was able to grow horizontally on the substratum, kept pace with aggregating sediment by accommodation of its tube growth, and formed small buildups (Zatoń et al., Reference Zatoń, Niedźwiedzki, Rakociński, Blom and Kear2018). Thus, the small size and planispiral morphology of Aculeiconchus n. gen. seem to be rather unlikely features for stable residence on a soft bottom, even with the aid of thin, basal spines, which are present in some much larger brachiopods. It is very likely that such tiny organisms would have been easily displaced, covered by sediment, and smothered by any strong sedimentary event or the burrowing activities of benthic animals.

Figure 10. Reconstruction of Aculeiconchus sandbergi n. gen. n. sp.: (1) a productide brachiopod mode of life, in which the microconchid rests on unconsolidated substratum with basal spines serving as anchoring, stabilizing devices (less likely); (2) a cyclostome bryozoan mode of life, in which the microconchid colonizes an algal thallus with its basal spines serving as attachment extensions that were adapted for fixation to flexible substrata (preferred). The ciliated lophophore crown is hypothetical.

A much better analogy is provided by some Recent and fossil bryozoans. As mentioned above, examples of both modern cyclostome tubuliporines, e.g., Tubulipora andersonni and some fossil examples (see Voigt, Reference Voigt1992), possess calcified tubular extensions growing on the underside of the colonies, which enabled the bryozoans to efficiently fix to soft, flexible substrata, e.g., algae (Boardman, Reference Boardman and Moore1983; Voigt, Reference Voigt1992). Similar, but chitinous, basal extensions also occur in the order Cheilostomata (Voigt, Reference Voigt1992; Vieira and Stampar, Reference Vieira and Stampar2014). Such basal tubular extensions, serving as restricted points of attachment, could prevent the bryozoan colonies from cracking during bending of flexible substrata, e.g., algal thalli. A similar role could have been played by the basal spines of Aculeiconchus n. gen. (Fig. 10.2), especially because some microconchids colonized algal substrata (e.g., Peryt, Reference Peryt1974; Zatoń and Peck, Reference Zatoń and Peck2013; Shcherbakov et al., Reference Shcherbakov, Vinn and Zhuravlev2021). The terminations of some basal spines of microconchids are flat (Fig. 4.3, 4.6) like those of bryozoans (cf. Boardman, Reference Boardman and Moore1983, fig. 61.1; Voigt, Reference Voigt1992), suggesting a firm, wide attachment area. The variable length of basal spines in these microconchids, on other hand, is strong evidence that the encrusted substratum was flexible and uneven at the point of tube attachment, in part because by basal spine lengthening, the animal could adjust its tube growth on a flexible substratum. In many cases, microconchids are found as loosely scattered specimens, possibly indicating detachment following degradation of such unmineralized substrata. In the deposits of the Maywood Formation, specimens of Aculeiconchus n. gen. are also loosely scattered in the host deposit, being commonly preserved obliquely and as overturned individuals. This kind of preservation might have resulted from substratum degradation, followed by the scattering of specimens on the bottom. The lack of algal fossils preserved in the Maywood deposits certainly results from purely taphonomic processes. It is well known that noncalcified algae have very low fossilization potential, and if they are preserved, they are usually confined to dark, fine-grained Konservat-Lagerstätte deposits (e.g., LoDuca et al., Reference LoDuca, Melchin and Verbruggen2011; Filipiak and Zatoń, Reference Filipiak and Zatoń2016). Even carbonate thalli of charophyte algae usually disintegrate after algal death and source the fine-grained fraction of the bottom sediment (e.g., Apolinarska et al., Reference Apolinarska, Pełechaty and Pukacz2011). Only their calcified female fructifications (gyrogonites) are usually fossilized and provide evidence for the presence of the charophyte. Such microconchid–gyrogonite associations are known from the fossil record (Racki and Racka, Reference Racki and Racka1981; Ilyes, Reference Ilyes1995; Zatoń and Peck, Reference Zatoń and Peck2013; Shcherbakov et al., Reference Shcherbakov, Vinn and Zhuravlev2021), indicating that at least some microconchids might have colonized these algae. Assuming that Aculeiconchus n. gen. microconchids lived similarly to some bryozoans, their basal spines could be the sole evidence of the former presence of algae to which they attached.

As mentioned above, some specimens also have helically uncoiled tubes in an upright position. Such vertical growth mode could have resulted from several factors, including escape from other encrusting organisms, or in the case of inhabiting strictly benthic microhabitat (e.g., shells, stones), an attempt to keep pace with sediment aggradation (Burchette and Riding, Reference Burchette and Riding1977; Vinn, Reference Vinn2010). Given the absence of other associated epibionts in the Maywood deposits, and the assumption that microconchids colonized algal thalli well above the bottom sediment, the crowding of associated microconchids on a given substratum is a more likely explanation for helical tube growth in some of the specimens.

A bryozoan-like attachment mode, found for the first time in Aculeiconchus n. gen. microconchids, not only provides a completely novel attachment strategy in this group of tentaculitoid tubeworms, but also suggests that microconchids were even more phylogenetically close to their ‘lophophorate’ relatives (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Vinn and Wilson2010; Vinn and Zatoń, Reference Vinn and Zatoń2012). Analysis of characters (see Vinn and Zatoń, Reference Vinn and Zatoń2012) placed the entire tentaculitoid group close to the Brachiozoa (Brachiopoda + Phoronida). However, in addition to the calcareous skeleton, bulb-like tube origin, lamellar and punctate (with punctae pointed in a direction of skeletal accretion) tube microstructure, the presence of budding in some of the species (Helicoconchus, see Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Vinn and Yancey2011), and encrusting mode of life characteristic for all microconchids in general (e.g., Taylor and Vinn, Reference Taylor and Vinn2006; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Vinn and Wilson2010), the presence of hollow basal spines serving as devices for attachment to flexible substrata in Aculeiconchus n. gen. suggests that microconchids, unlike other tentaculitoids (see Vinn and Zatoń, Reference Vinn and Zatoń2012), might not have been as phylogenetically distant from bryozoans as previously thought.

Paleoecological implications

The Maywood Formation is widely distributed in Montana and northern Wyoming (Sandberg, Reference Sandberg1961; Kauffman and Earll, Reference Kauffman and Earll1963; Sandberg and McMannis, Reference Sandberg and McMannis1964). As mentioned earlier, based on its faunal composition (fish and spores), the Maywood was deposited in brackish or fresh water (Sandberg and McMannis, Reference Sandberg and McMannis1964) within shallow, potentially long, narrow estuaries that extended from epicontinental seas during transgression of the Middle Devonian. Further transgression eventually led to widespread nonchannelized deposition of the marine Jefferson Formation in the early Late Devonian.

The paleosalinity range for microconchids is highly debated (Gierlowski-Kordesch and Cassle, Reference Gierlowski-Kordesch and Cassle2015; Zatoń et al., Reference Zatoń, Wilson and Vinn2016b). Taylor and Vinn (Reference Taylor and Vinn2006) and Zatoń et al. (Reference Zatoń, Vinn and Tomescu2012a) showed that microconchid tubeworms as a group were tolerant of different paleosalinity regimes and habitats, and were able to thrive in various fully marine, brackish, or even freshwater paleoenvironments. Gierlowski-Kordesch and Cassle (Reference Gierlowski-Kordesch and Cassle2015), however, argued that osmoregulation from fully marine to fully freshwater conditions by the microconchids is highly unlikely, and that they would have only occupied marine- and brackish-water settings. They hypothesized that the existence of microconchids in association with freshwater fauna was due to transport of marine or brackish water microconchids by marine processes (e.g., storm surges). On the basis of numerous examples, Zatoń et al. (Reference Zatoń, Wilson and Vinn2016b) rejected this hypothesis and supported the idea that microconchids originated in the Late Ordovician in shallow shelf environments and later colonized marginal marine environments, and eventually freshwater habitats by the Early Devonian through the evolution of osmoregulation (Zatoń et al., Reference Zatoń, Vinn and Tomescu2012a), as did ostracodes during their invasion of freshwater habitats (Bennett, Reference Bennett2008). Indeed, the colonization of freshwater habitats by microconchids is supported by firm paleontological evidence, e.g., their coexistence with such terrestrial or freshwater components as vascular plant remains (Sandberg, Reference Sandberg1963; Brower, Reference Brower1975; Mastalerz, Reference Mastalerz1996; Zatoń and Mazurek, Reference Zatoń and Mazurek2011; Caruso and Tomescu, Reference Caruso and Tomescu2012; Florjan et al., Reference Florjan, Pacyna and Borzęcki2012; Zatoń and Peck, Reference Zatoń and Peck2013; Shcherbakov et al., Reference Shcherbakov, Vinn and Zhuravlev2021), charophytes (Ilyes, Reference Ilyes1995; Zatoń and Peck, Reference Zatoń and Peck2013; Shcherbakov et al., Reference Shcherbakov, Vinn and Zhuravlev2021), spinicaudatans, and freshwater ostracodes and bivalves (Trueman, Reference Trueman1942; Zatoń and Peck, Reference Zatoń and Peck2013; Shcherbakov et al., Reference Shcherbakov, Vinn and Zhuravlev2021).

The Aculeiconchus n. gen. microconchids of the Maywood Formation are found in association with plant remains, but they also exist in carbonate facies that grade into the overlying, fully marine Jefferson Formation. These suggest a likely brackish water origin, although temporary fully freshwater conditions cannot be ruled out. This is supported by the organic microfossil data presented in this study. Indeed, the terrestrial spores recovered from the Maywood samples belong to progymnosperm, lycopsid, and primitive fern groups (see Supplemental Data 1), which were major components of swamp plant communities (Streel and Scheckler, Reference Streel and Scheckler1990), suggesting very close proximity of freshwater sources to the depositional paleoenvironment of the Maywood Formation. The highly abundant progymnosperm Geminospora spp. indet., in particular, specifically suggests deposition in, or adjacent to, fluviolacustrine, lower floodplain, or paralic environments (Streel and Scheckler, Reference Streel and Scheckler1990). Fine granular and fibrous AOM with orange fluorescence has been linked with various terrestrial and algal aquatic sources. In addition, well-preserved terrestrial spores, and the presence of megaspores, tetrads, and pyrite, all support a brackish, shallow-water depositional setting. This agrees with other fossiliferous and lithologic evidence provided in this and previous studies (e.g., Sandberg, Reference Sandberg1963).

The large aggregations of monospecific microconchids likely reflect colonization of stressed environments (Zatoń et al., Reference Zatoń, Vinn and Tomescu2012a), specifically in waters of variable salinities, which we envision for the Maywood estuaries. The abundance of microconchids in these settings is due in part to environmental exclusion of predators and competitors, and an abundance of nutrients delivered directly from fluvial sources (Zatoń et al., Reference Zatoń, Vinn and Tomescu2012a; Shcherbakov et al., Reference Shcherbakov, Vinn and Zhuravlev2021).

A nearly identical suite of fossils, including microconchids, plant debris, spores, and fish fragments, are present in the underlying Beartooth Butte Formation at both Cottonwood Canyon and Beartooth Butte (Sandberg, Reference Sandberg1961, Reference Sandberg1963; Elliot and Johnson, Reference Elliot, Johnson, Klapper, Murphy and Talent1997; Caruso and Tomescu, Reference Caruso and Tomescu2012). Those estuarine channel-fill deposits are Lockhovian/Pragian and Emsian in age, respectively, and thus the older strata at Cottonwood Canyon are nearly 30 Myr older than the Maywood strata (Elliot and Ilyes, Reference Elliot and Ilyes1996; Elliot and Johnson, Reference Elliot, Johnson, Klapper, Murphy and Talent1997; Noetinger et al., in press). The reappearance of nearly identical lithofacies and suites of vertebrate, invertebrate, and flora is a remarkable paleogeographic and paleoecological pattern. Paleogeographically, channels cut during lowstands were repeatedly inundated by transgressing oceans, establishing estuarine valleys that were filled by fine-grained mixed siliciclastic–carbonate strata. This paleoecologic pattern was repeated over a 30 Myr interval and includes the colonization of dynamic, migrating, brackish to freshwater environments by opportunistic, monospecific microconchids and associated nektonic vertebrate and cartilaginous fauna. In the Cottonwood Canyon section, the Maywood channels were in the upper reaches of the estuarine system and were <5 m deep (Sandberg, Reference Sandberg1963). This narrow, marginal marine realm, with its component fauna and flora, would have tracked the Givetian transgressing ocean, producing a characteristic lithofacial and biofacial assemblage that replicated those established earlier in the Lower Devonian during deposition of the Beartooth Butte Formation. However, the specific nature of microconchids changed from those encrusting Drepanophycus plants, as known from the Beartooth Butte Formation, to a completely new species that could have evolved basal spines adapted for fixation to flexible algal substrata.

The repeated incision of the Beartooth Butte and Maywood channels into bedrock preceded the Antler Orogeny and associated foreland basin (Speed et al., Reference Speed, Elison, Heck and Ernst1988; Dorobek et al., Reference Dorobek, Reid, Elrick, Cooper and Stevens1991), which largely affected areas far to the west (i.e., Nevada region) and was initiated after deposition of these units. The Antler Orogeny is generally attributed to mid-Frasnian at the earliest and generally Late Devonian to Early Mississippian (Silberling and Roberts, Reference Silberling and Roberts1962; Smith and Ketner, Reference Smith and Ketner1968; Johnson and Pendergast, Reference Johnson and Pendergast1981; Macke, Reference Macke and Stoeser1993; Ketner, Reference Ketner2012).

The Wyoming shelf was thus tectonically quiescent during most of the Devonian, which indicates that channel incision during lowstands was almost certainly driven by eustasy (Dehler, Reference Dehler1995; Grader and Dehler, Reference Grader, Dehler, Hughes and Thackray1999). The Beartooth Butte Formation, with channel-fills of Lockhovian/Pragian boundary (Cottonwood Canyon) and mid-Emsian (Beartooth Butte, Wyoming) ages, correspond to well-known regressive to transgressive episodes, specifically the bases of Johnson et al.'s (Reference Johnson, Klapper and Sandberg1985) Ia and Ic events, respectively (see also Johnson and Sandberg, Reference Johnson, Sandberg, McMillan and Glass1988). The Maywood channels were filled during the Givetian, corresponding to the base of the IIb event (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Klapper and Sandberg1985; Johnson and Sandberg, Reference Johnson, Sandberg, McMillan, Embry and Glass1989). These eustatic events created narrow, stressed ecological niches that microconchids were well adapted to exploit, and they did so repeatedly over a long stretch of geologic time by tracking transgressive pulses within valleys cut during previous episodes of lowstand erosion.

Conclusions

Herein, we describe a new genus and species of microconchid, Aculeiconchus sandbergi n. gen. n. sp., from samples collected from the Devonian Maywood Formation of Wyoming, which has basal spines on the undersides of their tubes. In this regard, they are unusual relative to all previously described microconchid species, which either lack spines or have dorsal and lateral spines only. The spines are identical with respect to microstructure, and thus in formation mechanism, to spines of all other species of microconchids. All microconchid spines, including those of Aculeiconchus n. gen., are comparable to the tubular hollow spines known in some brachiopod groups, especially siphonotretids and productides. They are also like basal tubular extensions in some modern and fossil cyclostome bryozoans. The basal spines of Aculeiconchus n. gen. certainly had an adaptive function different from the dorsal and lateral spines in other microconchid species. Unlike some productide brachiopods, which used the hollow spines for anchoring and stabilizing the shell on unconsolidated soft sediment, we propose that the basal spines of the Aculeiconchus n. gen. microconchids had a similar function to the tubular basal extensions of some cyclostome bryozoans, which use them for fixation to flexible algal thalli. Such an ecological adaptation is novel relative to all microconchids described to date, thus expanding their disparity and the range of known strategies for colonization of variable substratum types and paleoecological habitats, for this poorly recognized clade of opportunistic tentaculitoids. Moreover, the bryozoan-like basal spines found in Aculeiconchus n. gen. suggests that microconchids, although phylogenetically linked with ‘lophophorates,’ might not have been so distant from bryozoans.

The Maywood microconchids are both dispersed and make up very thin (a few mm) monospecific (Aculeiconchus sandbergi n. gen. n. sp.) shell accumulations. A wide variety of phosphatic cartilaginous and bony fish remains, and abundant plant fossils are found in association with these tubeworms. As with the underlying Lockhovian/Pragian Beartooth Butte Formation, which contains a nearly identical suite of fossils and was similarly deposited within channels, we interpret the Maywood as an estuarine, brackish water channel fill. The fauna and flora in both formations suggest that brackish water produced stressed environments that opportunistic microconchids repeatedly colonized over an ~30 Myr interval. These narrow, shallow-water environments tracked marine incursions through channels that were successively cut during repeated lowstands. Tectonic quiescence of the central to northern US Rocky Mountain region during most of the Devonian indicates that erosion and subsequent deposition were driven by major eustatic events.

These Devonian deposits record a remarkable paleogeographic and paleoecological pattern that is recorded by channel erosion, transgression, and colonization of a particular suite of flora and fauna, including microconchids. The specific salinity-stressed paleoenvironments led to a series of adaptive innovations in microconchids, specifically those that allowed colonization of a diverse suite of substrata from plant roots, to hard substrata, and to flexible soft algal thalli.

Acknowledgments

The research of M. Zatoń was partially supported by NCN grant 2018/31/B/ST10/00292. We thank Global Geolab Limited for processing the organic microfossil samples used for our palynological analysis; P. Taylor and A. Ernst for useful information on bryozoans and relevant literature; M. Coates for determination of fish fossils; B. Waksmundzki for the line drawings in Figures 9, 10; E. Olempska for the SEM photomicrographs in Figure 7. The editors, O. Vinn, and an anonymous reviewer are thanked for corrections, remarks, and constructive comments that improved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability statement

Data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.wwpzgmsk7.

Supplemental Data 1. Botanical affinity of the taxa encountered in the Maywood Formation.