1. INTRODUCTION

Ships are increasingly using information and operational technology systems that depend on digitisation, networking and integration. As the reliance on computing and communication technologies is growing, the need for cyber risk management is becoming critically important (Polatid et al. Reference Polatid, Pavlidis and Mouratidis2018; Hareide et al., Reference Hareide, Jøsok, Lund, Ostnes and Helkala2018; Shapiro et al., Reference Shapiro, Maras, Velotti, Pickman, Wei and Till2018; Botunac and Grz̆an, Reference Botunac and Grz̆an2017; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Park, Lee and Kang2017; Hassani et al., Reference Hassani, Crasta and Pascoal2017; Burton, Reference Burton2016; Balduzzi et al., Reference Balduzzi, Pasta and Wilhoit2014; Svilicic and Kras, Reference Svilicic and Kras2005). Recently, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) has published Guidelines on high-level recommendations for maritime cyber risk management (IMO MSC, 2017c). While maritime regulations and policies currently do not adequately govern cyber security in the same way as other aspects of ship security and safety, cyber security risk assessment can be considered as being partly regulated by the International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPS) Code established by the IMO (IMO, 2013). However, the IMO has decided to incorporate cyber risk management into the International Safety Management (ISM) Code safety management system on ships by 1 January 2021 (IMO MSC, 2017b).

Systematic assessment of maritime cyber risk management is essential for improving cyber security on ships. Ship cyber risk assessment represents a complex set of interdependent and intersecting actions that act as safeguards against the challenges presented by recent innovations in computing and communication technologies and key shipboard operations. An effective ship cyber risk assessment should provide a method to balance appropriate cyber safeguard mechanisms and measures of evaluating a ship's critical cyber systems and assets, key shipboard operations, existing safeguard controls, assessed cyber threats and vulnerabilities, and a determined risk level.

In this paper, a comprehensive cyber risk assessment of a ship is presented to offer guidance for improving the security level of cyber systems on board ships. The assessment was conducted on the training ship Fukae-maru (shown in Figure 1) (Kobe University, 2018), and was based on a combination of a survey given to the ship's crew and computational vulnerability scanning of the ship's Electronic Chart Display and Information System (ECDIS). The ship's cyber security level has been evaluated by a quantitative cyber risk analysis.

Figure 1. Training ship Fukae-maru.

2. CYBER SECURITY ASSESSMENT PROCESS

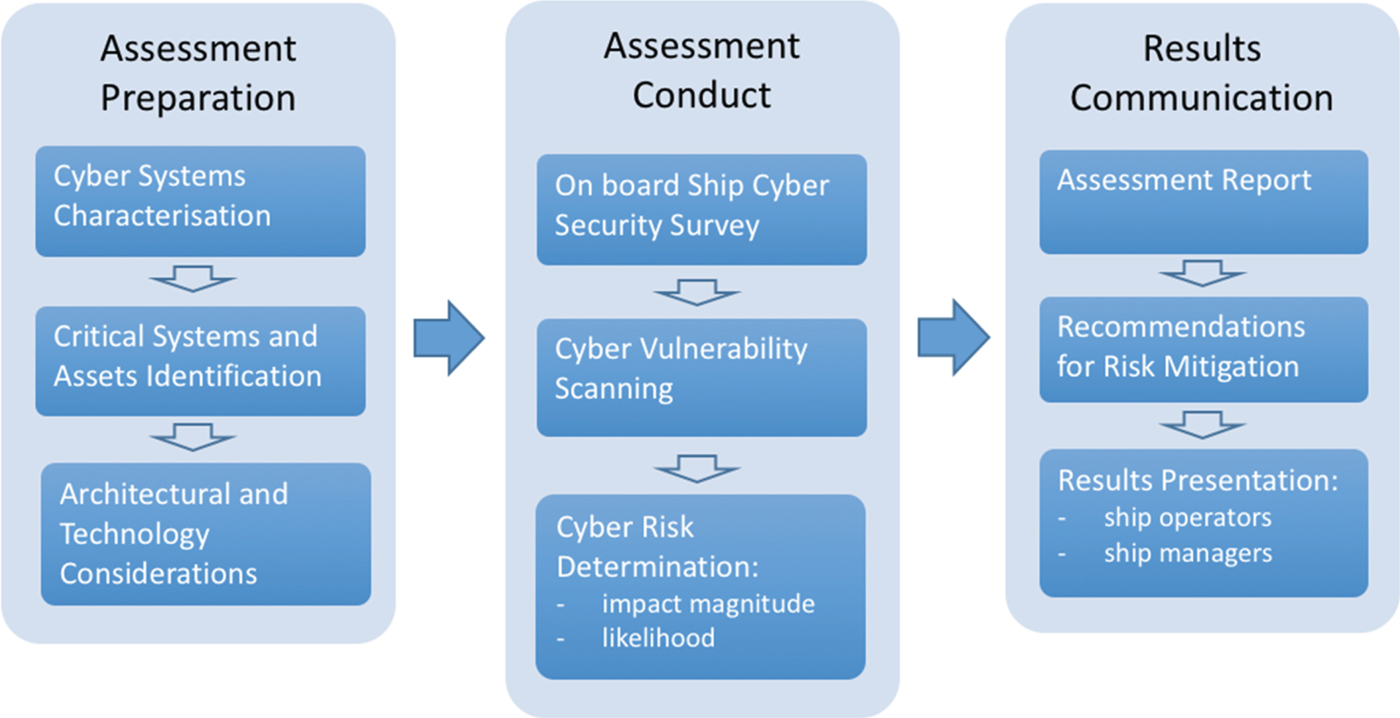

The cyber security assessment of the training ship Fukae-maru was conducted according to the assessment process shown in Figure 2. The developed assessment process relies on published guidelines and practices (IMO MSC, 2017c; NIST, 2018, BIMCO, 2017; DNV-GL, 2016). The process consists of three main phases: assessment preparation, conduct and results communication. The process is not intended for initial assessment only, but also for periodic implementation to respond to rapid technological changes in a ship environment.

Figure 2. Cyber security assessment process conducted.

In the first phase of the conducted assessment, the ship cyber systems were characterised by gathering information about general ship technical specifications. The identification of critical ship systems and assets was conducted on the basis of the ship's technical specification documentation and implemented together with the following architectural and technological considerations. Table 1 shows the technical specifications of the ship's ECDIS system, which is analysed in further detail in Chapter 3.

Table 1. Fukae-maru's ECDIS system technical specification

The first phase outputs were used to develop a survey for on board ship estimation of cyber security safeguards implemented on the ship (second phase of the process). Compared to other types of ship assessment (Ernstsen and Nazir, Reference Ernstsen and Nazir2018), the most specific element of the cyber security risk assessment is the conduct of computational vulnerability scanning of the ship's critical cyber systems. Computational cyber vulnerability scanning is a process of reviewing critical systems and assets to locate and identify known weaknesses. In the last segment of the assessment conduct phase, the cyber risk is determined on the basis of likelihood and impact magnitude of the threats and vulnerabilities detected by the survey and vulnerability scanning report. In the final phase of the process, the assessment results are reported, a recommendation for cyber risk mitigation is developed, and overall assessment results are presented to the ship's crew.

3. ON BOARD SHIP CYBER SECURITY SURVEY

The goal of performing and documenting the ship cyber security survey is to identify non-existing and/or insufficient safeguard mechanisms and measures. In addition, the cyber security survey is essential to confirm that cyber security safeguard mechanisms and measures are in place on the ship. To collect the relevant information, we developed a questionnaire on the basis of the ship cyber risk critical systems and assets identified. The form used for the survey conducted by interviewing the ship crew is given in Table 2.

Table 2. Form used for conducting the survey by interviewing the ship crew

The survey is segmented into four parts regarding the ship's cyber critical systems: the cyber security management system, bridge systems, power systems and networking systems (Table 2). Each of the segments has been individually categorised regarding the related assets and possible cyber threats. Data collection was conducted by interviewing the ship's crew, the ship's captain and the first officer for the cyber security management system, bridge systems, and networking systems. The first engineer officer was interviewed for the power systems. The evaluation results from these surveys concerning cyber security safeguard mechanisms and measures are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Cyber security measures and mechanisms incorporated

In Table 3, the critical network security system (see Table 2) is incorporated in the bridge systems and power systems. The survey results indicate that cyber security is integrated in the ship policies and procedures only in part, and policies and procedures mainly dedicated to cyber security are not fully developed. However, the policies and procedures are well communicated and periodically reviewed. The ship's crew is trained by the ship's systems vendors, as well as by the University. The bridge systems and power systems demonstrated an equal level of cyber security. On the vessel itself, an Internet connection is not established, a physical access policy is in place, the handling of portable devices is controlled, logical authentication is in place, authorisation using strong control mechanisms is enforced and confidential agreements with all suppliers and sub-suppliers are in place.

4. CYBER VULNERABILITY COMPUTATIONAL SCANNING

Computational cyber vulnerability scanning is a process of reviewing critical systems and assets to locate and identify known weaknesses. The computational scanning of the ship's ECDIS system was performed using an industrial-leading software tool, Nessus Professional (Nessus, 2018). As the ECDIS operates in the stand-alone configuration with no Internet connection, a laptop with the vulnerability scanner pre-installed was directly connected to the ECDIS via an Ethernet cross cable. While the ECDIS application was running under administrative credentials, the remote vulnerability scanning was performed without administrative privileges. The testing setup is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Testing setup for computational vulnerability scanning of ECDIS.

The scanning report summary including the ECDIS IP address (192·168·60·59) is shown in Figure 4. The computational scanning resulted in 14 vulnerabilities detected and 23 information packages identified. Half of the vulnerabilities detected have been assigned designations under the critical risk factor, indicating the need for urgent action in solving security issues. From the rest of the vulnerabilities, two, four and one have been respectively marked with high, medium and low risk factors, respectively.

Figure 4. Nessus Profession vulnerability scanner summary report on vulnerabilities detected.

The ECDIS critical cyber vulnerabilities detected together with descriptions and possible solutions are given in Table 4. The detected critical cyber vulnerabilities (Table 5, vulnerabilities 1 and 2) alert that the ECDIS system (which is IMO compliant) is implemented on a computer with a version of the operating system (Microsoft Windows XP, Service Pack 2) that is has not been supported by the vendor for more than four years (Microsoft, 2018). The lack of support implies that no new security patches for the operating system have been released by the vendor. In addition, the vendor is unlikely to investigate or acknowledge reports of newly discovered vulnerabilities. This allows an attacker to exploit well-known vulnerabilities using widely available tutorials, for which significant expertise and knowledge in computational technologies is not needed. As a consequence of the outdated operating system, five critical vulnerabilities related to different active services were raised and detected by the vulnerability scanner (Table 4, vulnerabilities 3 - 7). The common characteristic of these vulnerabilities is a provision of remote access to the ECDIS with logically authorised privileges. The possible solution for these detected critical vulnerabilities is to upgrade to a supported version of the operating system with a supported service pack and appropriate security patch. It is important to point out that the supporting operating system updates could significantly impact the ECDIS software performance (IMO MSC, 2017a), and therefore it should be conducted by the ECDIS equipment manufacturer.

Table 4. ECDIS cyber vulnerabilities computationally detected and assigned with the critical risk factor.

* Implementation of the possible solution is to be conducted by the ECDIS equipment manufacturer.

Table 5 shows detected vulnerabilities classified with risk factors of high, medium and low. The detected high-risk factor vulnerabilities are related to omissions of services running on the ECDIS, allowing for possible unauthorised remote code execution. The solution requires urgent installation of a set of security patches for the operating system provided by the vendor. The medium and low risk factor vulnerabilities detected are also related to the remote establishment of unauthorised access. The possible solution for these vulnerabilities includes adequate configuration of the operating system by activating available options. It is worth noting that the detected vulnerabilities arise from services running on the ECDIS that are not required for the expected functionality of the ECDIS operating in the stand-alone configuration, as it is on the Fukae-maru. With an adequate operating system setup, which should be based on the disabling of unnecessary services, the cyber security level of the ECDIS would be significantly improved without influencing fundamental functionality. As in the case of the supporting operating system updates, these activities could also impact the ECDIS software performance significantly and are to be conducted by the ECDIS equipment manufacturer.

Table 5. ECDIS cyber vulnerabilities computationally detected

* Implementation of the possible solution is to be conducted by the ECDIS equipment manufacturer

5 CYBER RISK DETERMINATION

On the basis of the survey conducted and computational vulnerability scanning results, a cyber risk analysis was performed to identify and categorise cyber threats to which the ship is exposed. Table 6 shows the cyber threats determined together with estimated likelihood and impact magnitude of their exposure. The threat likelihood has been defined as a rating of the probability that a vulnerability is exploited. The likelihood levels are given as low, medium and high with given values of 0·1, 0·5 and 1, respectively. The impact refers to the magnitude of harm resulting from successful exploitation of a vulnerability. The impact magnitude rates are given as high, medium, and low with given values of 100, 50 and 10, respectively.

Table 6. Cyber threats determined

Five of the nine cyber threats determined (Table 6) are related to the bridge systems and power systems, while four of the remaining threats influence all of the ship cyber critical systems. On the basis of the evaluated impact magnitude and likelihood of the threats determined, a qualitative risk analysis was performed. Cyber risk level is calculated by multiplying the threat likelihood ratings with the impact magnitude of the vulnerability exploited. The result indicates qualitative risk levels: (i) critical-risk level requiring immediate action (multiplication product higher then 90), (ii) high-risk level requiring remediation implementation plan (multiplication product higher then 50), (iii) medium-risk level which may be acceptable over the short term (multiplication product higher then 10), and (iv) acceptable low-risk level (multiplication product lower then 10). Results of the qualitative risk analysis of cyber threats determined are given in the cyber risk-level matrix in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Risk-level matrix with qualitative risk analysis of cyber threats determined.

The risk-level matrix (Figure 5) indicates that the first five cyber threats determined (see Table 6) represent the medium-risk level for ship cyber security. The cyber risk with the highest risk level assigned (medium-risk level with the multiplication product of 20) is related to physical access. While safety procedures in the maritime field are traditionally focused on physical security, for a ship's electronic equipment, the establishment of unauthorised physical access represents a threat with the highest impact magnitude. An example frequently performed on a ship is plugging a malware-infected Universal Serial Bus (USB) memory stick into ECDIS for the purpose of an electronic charts update. In addition to raising awareness on the cyber hygiene and anti-malware tools usage, the ECDIS hardware (including USB ports) should be kept in a locked case to prevent physical access by unauthorised personnel. However, for a training ship with strongly controlled student access, the threat likelihood is estimated as low (value of 0·2, see Table 5). The four medium-risk level cyber threats determined are related to the operating system maintenance and remote authorised access (threats 2-5 in Table 5). As the assessment has been conducted on a training ship with no Internet connection, the medium-risk level risks are acceptable over the short term, at least until an Internet connection is established on the ship. With an active Internet connection, the cyber risks would rise to the critical-risk level, requiring immediate action. The acceptable low-risk level has been assigned to the cyber risks affecting all the ship critical systems (threats 6-9 in Table 5) and requiring the development of cyber security-focused policies and procedures, crew training, awareness raising and periodic evaluation and improvements. While the low-risk level cyber risks do not necessarily have to be solved in the short term, the recommended action should be taken to mitigate the cyber risks.

6. CONCLUSIONS

A comprehensive experimental assessment of the Fukae-maru's cyber security management has been presented. An assessment process consisting of three phases was developed: the assessment preparation activities, assessment conduct and results communication. The ship's incorporated cyber security safeguard measures and mechanisms were identified via the developed survey and by interviewing the ship's crew. Computational vulnerability scanning of the ship's ECDIS system has been introduced as a specific part of cyber security assessment conduct and the Nessus Professional software tool was used for this. A quantitative cyber risk analysis has been conducted for evaluation of the ship cyber risks. The presented assessment process is comprehensive and applicable to all ships, offering guidelines for mitigating cyber risks and to improve the cyber security level of ship cyber critical systems and assets.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

The research was financially supported by the Erasmus+ programme of the European Union (grant number 2016-1-HR01-KA107-021738) and the Faculty of Maritime Studies University of Rijeka under the research project Internet of Maritime Things and Cyber Security.