1. Introduction

The relationship between Italian fascism and technological progress was heavily based on aeronautical development. The advances in aviation enabled daring and record-breaking flights, which the regime promoted as political propaganda. In 1933, The New York American published Mussolini's article ‘Technocracy’, in which he stressed the importance of technological progress for fascist Italy and praised Italian seaplanes as being widely considered the best in world (Brose, Reference Brose1987). Despite the propagandistic tone of the statement, it reflected the almost decennial Italian supremacy in accomplishing sensational aeronautical feats using seaplanes, including Commander Francesco De Pinedo's flight from Italy to the Americas (1927), aerial cruises in the Western and Eastern Mediterranean (1928, 1929), and Italo Balbo's Atlantic flights from Italy to Brazil (1931) and Rome–Chicago–New York–Rome (1933). At the forefront of these successful endeavours, which secured international fame both for the Italian aviators and the seaplanes, was the record-breaking distance flight of 55,000 km accomplished by two Italian airmen: De Pinedo (born in Naples, Italy, in 1890) and Chief Mechanic Ernesto Campanelli (born in Nuoro, Sardinia, in 1891). The voyage took place between 20 April and 7 November 1925 and was achieved in a small seaplane made of wood and canvas. The undertaking was named Crociera Aerea Roma–Australia–Giappone–Roma (Aerial Cruise Rome–Australia–Japan–Rome) and had a significant outcome for the regime in terms of propaganda. It contributed to creating a new image of Italy worldwide as a modern and competitive power in the field of aeronautical progress. The flight also stressed the pivotal role played by technology in Mussolini's ambitions to disseminate fascist ideology both in Italy and within the Italian community overseas (Lee and Kennedy, Reference Lee and Kennedy2020), by including a circumnavigation of Australia, home to many Italians immigrants.

De Pinedo–Campanelli's flight to Australia marked an important step for the newborn Italian Air Force (1923) in terms of technological progress and political propaganda. It should be noted how, between the 1920s and 1930s, the aeronautical development became a central subject in the political agenda of the most advanced countries, from the United States to Europe and Australia. Mastery over the skies could indeed pay dividends in terms of political propaganda and commercial exchanges. De Pinedo–Campanelli's endeavour, as this paper will explain, significantly contributed to these purposes. Their flight should be situated within the international competition of the 1920s for accomplishing record-breaking distance flights. Remarkable examples were the first trans-Atlantic non-stop flight from Newfoundland to Ireland by the British Alcock and Brown (1919); the first England-to-Australia flight by brothers Ross and Keith Smith (1919); the first flight from London to Cape Town by Van Ryneveld and Brand (1920); the first aerial circumnavigation, achieved by the US (1924); Alan Cobham's flights from England to South Africa (1925-1926) and to Australia (1926); Charles Lindberg's New York–Paris flight (1927) and Charles Kingsford Smith's trans-Pacific flight (1928).

Thus, this paper analyses the Australian section of the De Pinedo–Campanelli flight, focusing on their stops in Perth and Adelaide and their one-month stay in Melbourne, to throw light on how the Australian public and the Italian communities in Australia perceived the event. The paper is based on examination of De Pinedo's flight diary and accounts published in the Australian press at the time. It begins by describing the preparations for the journey and the choice of the seaplane and crew. Then it analyses the arrival of the airmen in Australia and investigates how the commercial companies involved in the flight exploited De Pinedo's name and his accomplishment as a marketing ‘influencer’ for their products. This study concludes by exploring the cultural legacy of De Pinedo and Campanelli's endeavour in modern Italy and Australia.

2. Purpose of the flight, choice of the seaplane and crew

On December 1924, the chief of staff of the Royal Italian Air Force (RIAF), Commander Francesco De Pinedo, conceived a plan to fly from Italy to Australia, on to Japan, and back to Italy in a small seaplane. De Pinedo's project aimed to demonstrate the feasibility and convenience of travel worldwide using seaplanes rather than sailing by ship. He based his proposition on the features of the seaplane, which could operate over both land and sea and alight on any lake, port, large river or river mouth, while a ship had no such features (De Pinedo, Reference De Pinedo1926). To test his theory, he aimed to fly a long-distance route, including a range of climatic and geographic characteristics. At the time, the longest flight ever accomplished was the first aerial cruise around the world of 43,000 km, achieved by four seaplanes from the US Army Air Service in 1924. De Pinedo proposed a route 12,000 km longer, totalling 55,000 km, divided into three main stages: from Sesto Calende to Melbourne; from Melbourne to Tokyo; and from Tokyo to Rome. The flight itinerary covered an immense imaginary triangle, whose vertexes were Rome, Melbourne and Tokyo. The whole route included 80 stops and would take approximately seven months and 370 flight-hours.

In January 1925, De Pinedo presented his final plan to the Italian government for approval. However, difficulties arose in terms of costs, forcing him to declare that he or his heirs would entirely refund the cost of the seaplane in the event of loss or failure of the flight (De Pinedo, Reference De Pinedo1926). This declaration allowed De Pinedo to proceed with the organisation of the flight and focus on finding an appropriate aircraft. He approached the Società Idrovolanti Alta Italia (SIAI), an Italian company manufacturing seaplane based in northern Italy, which was the official supplier for the RIAF. At the time, SIAI produced a two-seater floating biplane with a four-bladed wooden propeller, called Savoia S.16 ter, which was used by the RIAF's squadrons. These seaplanes were equipped with 300 hp engines manufactured by Fiat, but De Pinedo needed a more powerful engine to deal with long-distance flights. Since such an engine was not available in Italy at that time, he consulted the French motor company Lorraine–Dietrich, which had recently launched a new 450 hp engine prototype (De Pinedo, Reference De Pinedo1926). De Pinedo asked the company to provide two of these: one to be installed in the seaplane and the other to be sent to Tokyo as a replacement to cover the last stage of the flight. In the months prior to departure, De Pinedo travelled to London to obtain logistical support from the British authorities, as much of the route included flying over territories controlled by Great Britain. He also made agreements with the Shell Oil Company and Wakefield, the producer of Castrol oil, to ensure adequate provisions of petrol and engine lubricant throughout the route.

As his companion, he chose Chief Mechanic Ernesto Campanelli, who also acted as co-pilot and navigator. Campanelli had already flown with De Pinedo during the First World War and had been his mechanic on the flight from Italy to Holland in 1924. He was one of the most expert and well-regarded mechanics in the RIAF. Campanelli was sent to Paris to gain experience with the Lorraine–Dietrich 450 hp (Cauli, Reference Cauli2008). Once the seaplane was assembled, De Pinedo named it Gennariello after Saint Gennaro, the patron Saint of Naples, where he was born. On 20 April 1925, the pair were ready to depart from Sesto Calende (Varese), a small town near Lake Maggiore, where SIAI had its headquarters. The first stage of the daring flight, to Melbourne, covered 23,500 km in 51 days and 161 flight hours.

3. Reaching Australia by air: perception and recognition

A few days after their departure, the press began to release news about the progress of the flight. The notice reached Australia through The Adelaide Chronicle, which mistakenly reported De Pinedo's departure as being 1 May. The account emphasised the Australian assistance to the aviators granted by The Commonwealth Government and the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), which would help them to make the Australian section of the flight successful. Also, the city of Adelaide organised a civic reception to welcome them once they landed there.Footnote 1 Although the focus of the article was on the cooperation secured between the Australian authorities and the Italian aviators, this account shows how the flight had effectively engendered interest and anticipation in Australia weeks prior to the airmen's arrival. Thus, after flying over Greece, the Middle East, India, Thailand, the Sunda Islands and Indonesia, the aviators finally reached Australia on 31 May and landed in Broome, on the north coast of Western Australia.

Reaching Australia was important in several respects in terms of image for both fascist Italy and the RIAF. No other Italian aviators had landed in Australia prior to De Pinedo and Campanelli; their arrival in the continent broke the previous Italian aeronautical record-distance held by Arturo Ferrarin and Guido Masiero, who flew from Rome to Tokyo in 1920; and finally, they were the first Italians to reach Melbourne by air, where the Italian consulate, as will be discussed later, heavily promoted the event among the Italian community for propaganda purposes. Soon, Australian public interest in the flight increased, due to the continuous press coverage in the Australian newspapers, which provided the public with details and updates on the journey. The Sunday Times dedicated its cover page to the forthcoming arrival of the Italian aviators, even providing the time of their landing. The Mirror defined De Pinedo as a ‘plucky Italian airman’ whose departure from Kupang (the last stop before Broome) ‘had evoked a great interest’ in the continent. It also published a map of the itinerary, including all the Australian stops, to make its readership familiar with the flight, while inviting ‘every good Australian sportsman to wish the plucky Italians the best of luck in their venture’.Footnote 2

Once the aviators arrived in Broome, Mussolini sent a message to the prime minister of Australia to express the Italian government's pleasure on the completion of this stage of the flight. However, it also disclosed Mussolini's ambivalent attitude toward the venture, as he did not provide any official recognition during the flight's progress; instead, once the airmen landed in Australia, he propagandistically displayed ‘apparent confidence’ in praising the favourable outcome of the achievement and lauding De Pinedo's ability in accomplishing this feat.Footnote 3 Lord Stanley Bruce, prime minister of Australia, sent a telegram to De Pinedo, stating: ‘We welcome you in our country and we feel that your success will contribute to strengthening the existing friendship between Italy and Australia’ (De Pinedo, Reference De Pinedo1926). The next day, the press reported how the whole population of Broome had been gathered at the pier since the morning, waiting for the visitors, who ‘gracefully descended on Roebuck Bay.’ De Pinedo then gave his first interviews, expressing his pleasure at arriving in Australia and appreciating the welcome given him on landing.Footnote 4 An interesting account was published by The Sydney Morning Herald, which explained, for the first time, the purpose of De Pinedo's flight to its Australian readership: to demonstrate the technical efficiency of the RIAF and the worthiness of the Italian seaplane produced by the SIAI. The newspaper compared De Pinedo's feat with that of the British aviators Ross and Keith Smith, who flew from London to Darwin in 1919, specifying that De Pinedo had covered almost 17,000 km in 39 days, while the Smiths took 10 days less to cover the same distance. However, ‘the Australian airman was under compulsion of completing his journey within 31 days to win the Commonwealth Government's prize of £A10,000’.Footnote 5 After leaving Broome, the aviators rapidly reached Port Hedland, Carnarvon and Perth, the first major Australian city on their route, followed by Bunbury, Port Albany, Israelite Bay, Port Eyre and Adelaide.

Despite their fleeting visits to these locations, evidence of their passage to Perth, Bunbury and Adelaide reveals Australians’ eager interest in the flight. For instance, on 3 June in Perth, a few hours before their arrival, the whirring of another aircraft was mistaken for De Pinedo's, provoking a collective excitement: ‘Heads shot out of windows in the city, many folks ran into the streets to get a glimpse, while others eager to see the landing raced to the Esplanade.’ Later, the Italians landed in front of the Royal Perth Yacht Club, welcomed by a huge crowd where ‘scores of cameras clicked while one college boy was seen to clamber over the naval launch to the plane in order to secure an autograph’,Footnote 6 while the Italian community of Fremantle formally congratulated De Pinedo on his achievement. A few days later, their landing was echoed in Italy by the most popular Italian weekly magazine, La Domenica del Corriere, which dedicated its cover to celebrating the airmen's arrival in Perth (Figure 1). La Domenica helped to popularise De Pinedo and Campanelli's feat among Italians, because of its wide readership and its famous illustrator Achille Beltrame, whose painted covers were familiar to Italian readers.

Figure 1. Cover of La Domenica del Corriere celebrating the arrival of the aviators in Perth

De Pinedo's arrival in Australia put new energy into the debate on the feasibility of developing air routes between Europe and Australia, which was becoming a major issue with the Australian public. Furthermore, his interviews on the accomplishment provided him with the opportunity to discuss Italian aeronautical progress, the best evidence of which was having reached Australia by air. The basis of the interest in the flight's progress was the novelty that it represented. At that time, aircraft were almost unknown to people who lived in remote areas or small villages. Thus, it is not surprising that, apart from the many official receptions organised by local authorities, other acts of recognition of the achievement spontaneously and genuinely resulted from the curiosity of people who had never seen an airplane. Evidence of this was documented by De Pinedo in his diary, with instances such as the Bunbury mayor who telegraphed him asking him to fly repeatedly over the village as its inhabitants had never seen an airplane. Once there, a group of school children came to the river, where the floating plane was docked, to see the airmen and the biplane and asked them to sign their notebooks and fly again over their school before leaving the village. Also, schoolteachers in Adelaide telegraphed De Pinedo asking for a fly-over for their schools, as their pupils wanted to see the plane and the aviators (De Pinedo, Reference De Pinedo1926).

On 8 June 1925, the airmen landed in the Outer Harbour in Adelaide, at the end of the last stage prior to Melbourne. Their arrival in the city elicited the curiosity of the public, as De Pinedo (Reference De Pinedo1926) noted from the cockpit of his seaplane while flying over the city: ‘The traffic had been stopped, the population piled out on the streets, crossroads and squares: they were immobilised, astonished.’ As reported by The Adelaide News and The Advertiser Adelaide, an estimated 10,000 people crowed along the wharfs, on the stone embankments, and on the decks of ships to see the ‘daring Italian airmen’ landing. A long line of cars, ‘many decorated with the Italian colours’, congested the road to the Outer Harbour, where a thousand cars were parked. Finally, they landed amid ‘a tremendous ovation from the assembled crowd, the booming of steamers, and railway whistles, while many Italians on the wharf waved Italian flags’.Footnote 7 Such description gives an understanding of the increasing popularity of the airmen and the way the flight had significantly captured the popular imagination. The seaplane represented the newest icon of technological progress in the field of long-haul transport, which was replacing other symbols of modernity and progress from previous decades, such as cars, trains, trams and steamers. The mayor of Adelaide granted De Pinedo and Campanelli the ‘title’ of record-men, as their seaplane, which had flown for such a long distance, was the first representing another nation's arrival in Australia by air.Footnote 8 However, this stage of the flight was also important because it showed the propagandistic aspect behind the journey. De Pinedo stressed how aeronautical development was rapidly advancing in Italy, where ‘one sees immense workshops and factories devoted to the manufacture of instruments of the air’, making Italy one of the foremost among nations in the global progress of aviation. He thus motivated immense public interest in the flight internationally, because of people's awareness of the flight's potentialities.Footnote 9

4. The flight as a marketing strategy

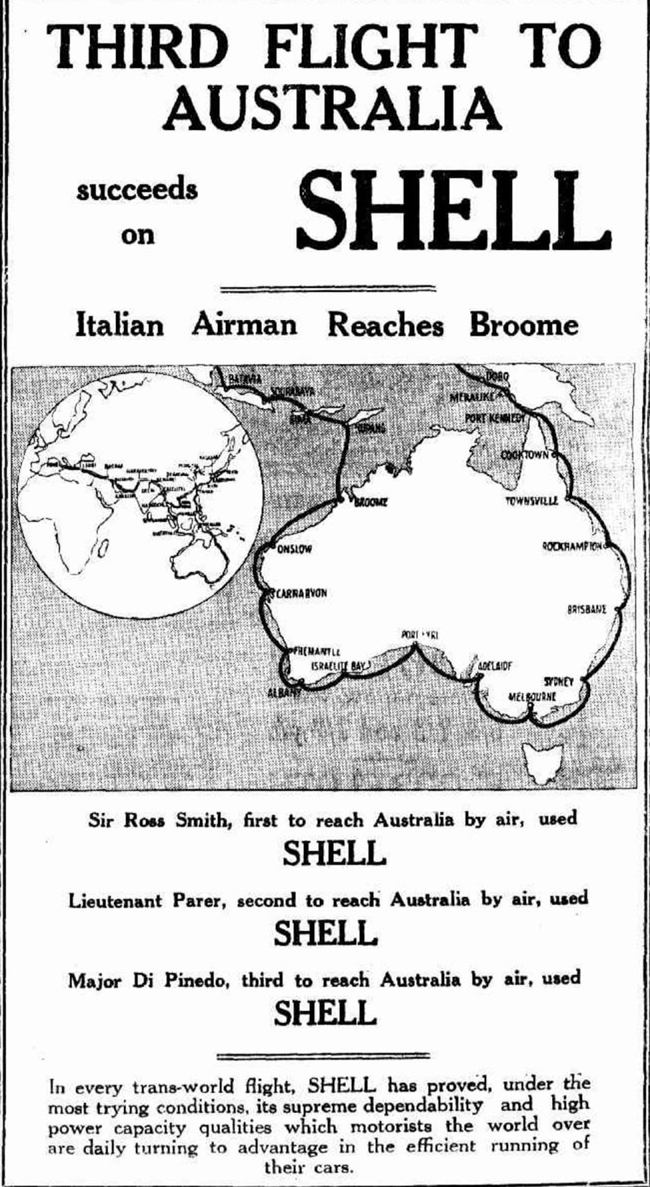

The successful arrival in Australia of the Italian aviators engendered intense commercial exploitation of the flight. It paid dividends in terms of the images of the companies involved: SIAI as the seaplane builder; Lorraine–Dietrich as builders of the engine; Titanine–Emaillite, which provided the aircraft dope; and Shell and Castrol, which were respectively the official providers of petrol and lubricant for the engine. De Pinedo's name became central in their marketing strategies. Shell, in particular, was highly proactive in associating its image with the commander's name (Figures 2 and 3). Its representative in South Australia emphasised the major contribution of the company to the success of the flight through its satisfactory arrangements for refuelling along the whole route. This allowed them to fly to Adelaide in record time and without mishap, as well as establishing the feasibility of civil aviation covering large distances throughout Australia.Footnote 10 This attitude reflected Shell's marketing strategy in sponsoring record-breaking exploits, such as car races, which expanded to include aviation by the 1920s. On his part, De Pinedo endorsed the company, declaring that any aviator using Shell petrol in his engine could accomplish sensational record-breaking flights (Heller, Reference Heller, da Silva Lopes and Duguid2010). This strategy increased a few days before the Italians reached Melbourne. Shell repeatedly published posters displaying its logo, the Italian seaplanes and De Pinedo's name to emphasise how his flight was the third one in Australia to succeed on Shell fuel at a speed of 100 miles per hour.Footnote 11 Lorraine–Dietrich also exploited the flight for commercial purposes, emphasising that De Pinedo had reached Melbourne ‘behind a Lorraine–Dietrich engine’.Footnote 12 However, the contribution of the French company to the flight was apparently overlooked by the Australian press, as George Bader, the trade commissioner for France to Australia, stated in a polemic to the editor of The Sydney Morning Herald. He said he was surprised ‘in reading the Sydney and Melbourne newspapers to see that nothing was said about the motor, a 450 hp Lorraine–Dietrich, of French manufacture [despite the fact] that the French community had enthusiastically followed the various stages of De Pinedo's wonderful flight’. Bader concluded his comment by mentioning Antonio Grossardi, the Italian consul general in Melbourne, who praised the success of the Italian aviator, without saying anything about the engine, stating ‘it would instead be fair for the public to know that the French motor played a most important part in De Pinedo's great success’.Footnote 13 Such debate demonstrates how the Italian exploit represented a significant return in terms of image for the commercial companies involved in it.

Figure 2. Advertisement published by Shell announcing the arrival of De Pinedo in Australia. (National Library of Australia.)

Figure 3. Advertisement published by Lorraine–Dietrich emphasising De Pinedo's exploit. (National Library of Australia.)

5. ‘Melbourne's Welcome To The Intrepid Italian Airmen.’

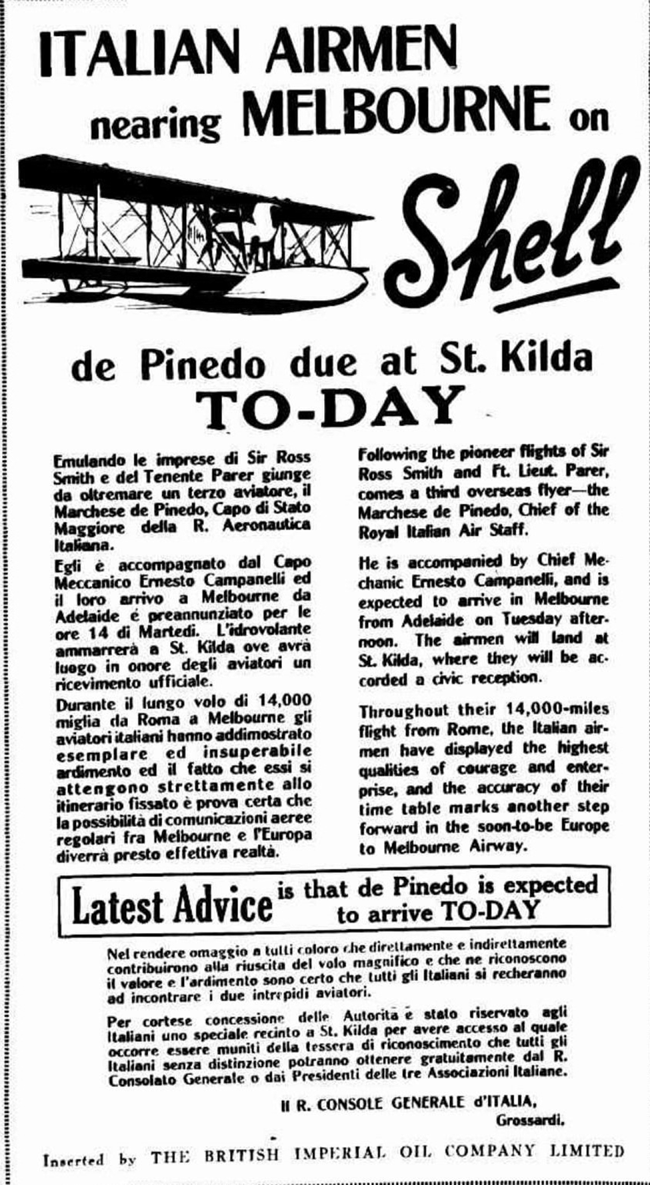

After leaving Adelaide, De Pinedo and Campanelli finally landed in Melbourne on 9 June at Saint Kilda Beach. The press gave great attention to their arrival, as it marked the successful conclusion of the first stage of the entire voyage. Cables spread the news of the achievement worldwide. No other Italian aviator had reached Melbourne before. It was a remarkable accomplishment, both for the airmen's popularity, which was at its highest, and for fascism, which could exploit the result to display Italy as a modern and technologically advanced nation. With regard to this, Melbourne represented a significant focus for the regime's propaganda apparatus, due to the significant Italian community living there. A central figure in celebrating De Pinedo's arrival was the Italian consul general, Antonio Grossardi, who based his diplomatic activities on fostering nationalism and concord to disseminate fascist ideology among the Italian immigrant community (Tosco, Reference Tosco2002). In terms of national pride, De Pinedo and Campanelli's flight was a crucial accomplishment for Italians in Australia, because it bolstered the image of Italy as a competitive power. This explains Grossardi's intense propaganda activity in the days prior to the aviators’ arrival. Several announcements appeared, a few even hosted in Shell's advertisements, indicating the date, time and location of the landing, both in Italian and English. This strategy aimed to secure the widest possible coverage of the news among his compatriots and the Australian public. In his messages to the Italian community, he emphasised the ‘highest qualities of courage and enterprise’ displayed by the two airmen and he was sure that every Italian will be there to praise the two Italian aviators’. He encouraged all Italians in the community to go to the Italian Consulate and collect a pass allowing them access to an area specifically reserved for Italians by the local authorities to enable them to easily see the landing (Figure 4).Footnote 14

Figure 4. Message of the Italian Consul published in Italian (left) and English (right) announcing the imminent arrival. of the aviators. (National Library of Australia.)

The news of De Pinedo and Campanelli approaching Melbourne engendered strong interest in the Australian public, as demonstrated in the accounts published in the days prior to the landing and the posters released by Shell, Wakefield Castrol Oil and Lorrain–Dietrich depicting the seaplane and lauding the brilliant performances of their products during the exploit.Footnote 15 On 9 June, the airmen landed at Saint Kilda Beach before thousands of people, while ‘the Italian colony seemed to be affected by a crisis of enthusiastic fury. Those who had followed our journey with great concern, finally felt a relief in seeing our arrival’ (De Pinedo, Reference De Pinedo1926). In its evening edition, The Herald published the aviators’ full-face photos framed by the Italian–English headline: ‘Melbourne da il benvenuto agli intrepidi aviatori italiani − Melbourne's welcome to the intrepid Italian airmen’, while promoting the publication of a full photographic coverage of the event to its readership in the next edition. The front page also reported De Pinedo's appreciation for the warm welcome received and his explanation for the flight, which was ‘a sporting one and perhaps for this reason appeals to the sport-loving Australians’.Footnote 16

The arrival of the Italian seaplane was a remarkable event in the history of the city. The RAAF provided an escort of honour to the incoming float-plane, as De Pinedo (Reference De Pinedo1926) wrote: ‘Two seaplanes of the Australian Air Force were waiting for us while flying over Port Phillips to guide towards Point Cook, where three squadrons of aircraft took off to escort us to Melbourne.’ The accounts of that day show how the public clearly understood the uniqueness of the event. Despite it being a working day in Saint Kilda, as reported in The Argus, all the shops closed and a large crowd assembled on the esplanade and foreshore.Footnote 17 According to The Herald, 20,000 eager people waited for the aviators at the pier, which was adorned with the Union Jack, the Australian and the Italian flags, while the police struggled to contain the thousands of people praising the aviators.Footnote 18 The barriers and police cordons were quickly overwhelmed by the surging, ‘wildly excited mass of people who wanted a close-up of the aviators amid cheers and cries of Viva l'Italia, from the many Italians gathered on the pier’, who eventually hoisted De Pinedo and Campanelli on their shoulders.Footnote 19 Once the airmen disembarked, the Italian consul, Grossardi, and Joseph Levi, mayor of Saint Kilda, who was dressed in his official robes, greeted them. Levi read an official message: ‘The Australian people are delighted to welcome the first foreigners to reach Melbourne from Europe by air.’ The government of the State of Victoria hosted a lunch to celebrate the airmen's achievement, while the mayor of Melbourne, Lord William Brunton, honoured them with a solemn function at Melbourne's Civic Hall. It was a rare event, ‘because the last time such a civic reception had taken place, during the visit of the Prince of Wales’ was in May 1920 (De Pinedo, Reference De Pinedo1926). De Pinedo spent almost one month in Melbourne to allow Campanelli to fully service the plane before undertaking the second stage of the flight. This sojourn saw the collaboration of the RAAF in servicing the seaplane, which was sheltered at Point Cook, where the RAAF Flying School had its headquarters and provided logistical assistance to Campanelli (Cauli, Reference Cauli2008).

The stop also provided the airmen with an opportunity to attend several official receptions, many of which were promoted by the consul, who thoroughly publicised these in the Australian press. The regular official receptions and the constant interest of the press in De Pinedo and Campanelli helped to turn them into celebrities. The journalists were always hovering over De Pinedo to interview and photograph him (Cauli, Reference Cauli2008), while the press often published the aviators’ photos, making them familiar to their readers. However, their popularity also increased because of the commercial posters released by Shell, picturing the cheerful faces of the airmen with the slogan: ‘The smile of success after 14,000 miles on Shell’, and by Lorraine–Dietrich, which portrayed the seaplane with the caption ‘Halfway around the world without trouble … and a Lorraine-Dietrich brought them!’Footnote 20 (Figures 5–8).

Figure 5. De Pinedo (left) and Campanelli (right) on the cockpit of their seaplane after landing in Melbourne. (Courtesy of The Royal Australian Air Force Museum, Point Cook, Melbourne.)

Figure 6. Advertisement published by Shell to celebrate the aviators’ exploit. (National Library of Australia.)

Figure 7. Chief Mechanic Ernesto Campanelli while servicing the seaplane at Point Cook, Melbourne. (Courtesy of The Royal Australian Air Force Museum, Point Cook, Melbourne.)

Figure 8. Members of RAAF Flying School providing logistical assistance to Campanelli. (Courtesy of The Royal Australian Air Force Museum, Point Cook, Melbourne.)

Furthermore, the Italian associations in Melbourne, including Dante Alighieri, Circolo Italiano Cavour, Circolo Duca degli Abruzzi and the consul general hosted a ceremony in a theatre to pay tribute to the aviators, and another at the Grand Hotel Menzis, where the attendees included the prime minister of Australia.Footnote 21 Later in August, a detailed photographic record of the function was published by The Home, a well-known glamour and style bimonthly magazine in 1920s Australia, which could be compared today with Vogue or Vanity Fair. Perhaps the most important ‘reception’ that De Pinedo attended was the opening session of the Australian Parliament, as a spectator. This enabled him to understand how a part of Australian society perceived Italy and the Italians. The prime minister's references to the country's immigration policy captured the attention of the aviator, who noted how Australia had restricted access to immigrants, ‘especially to those belonging to the yellow race’. He reported that ‘part of the public opinion has an unclear idea of Italy and the Italians, who are considered as coloured people. Someone was even astonished on seeing the colour of my skin was very similar to that of the Australians!’ However, De Pinedo's overall opinion of Australia was positive and he claimed that his stay in the country proved to him the existence of good relationships between Italy and Australia, and showed how the Italians living there could contribute to Australia's progress (De Pinedo, Reference De Pinedo1926).

De Pinedo also received telegrams from the Italian authorities, such as the president of the Chamber of Deputies, the Minister for the Colonies and the mayors of Rome and Naples, who praised the welcome accorded in Australia to the aviators and emphasised how the airmen's reception in Australia ‘would meet with a sympathetic echo throughout Italy’.Footnote 22 The fascist propaganda publicly lauded De Pinedo. Perhaps the best evidence of this is in Mussolini's closing speech, delivered at the national congress of the Fascist Party in Rome, while the aviators were still in Melbourne. Mussolini claimed that De Pinedo represented the new type of Italian that fascism aimed to create, as he embodied all the typifying features of a fascist, such as bravery, a love of challenges and pride in being Italian (Mussolini, 1934). Interestingly, Mussolini did not hesitate to glorify the aviator although the voyage was not yet completed. Reaching Australia was already a success in terms of propaganda, which could only increase once the aviators completed their journey. On 16 July 1925, the two aviators left Melbourne to travel to Sydney, before continuing to Brisbane, Rockhampton, Townsville, Innisfail, Cookstown and Port Kennedy, which concluded their circumnavigation of Australia. They then proceeded towards Japan. Finally, on 7 November 1925, after traveling abroad for seven months, the airmen returned to Rome, landing on the Tevere River before a wildly excited crowd and Mussolini, who proudly welcomed the two aviators.

6. The flight's legacy in modern Italy and Australia

The successful accomplishment of the daring flight was politically exploited by the fascist government. It presented an image of Italy abroad as a technologically advanced nation. Accounts of De Pinedo and Campanelli's arrival in Rome described thousands of Italians everywhere along the river; all the bridges crossing the Tevere were crowded. Mussolini and the government waited for the aviators at the Ponte di Ripetta dock. Once they landed, Mussolini delivered an official speech emphasising the political significance of the flight and praising De Pinedo, who ‘truly embodies the new generation of Italians, which fascism aims to create. Faraway and unknown peoples are now aware of what the new Italy is. His feat demonstrates the unbreakable vigour of the Italian people. Today, millions of people worldwide remember his name. It is a glorious day for all the Italian people.’Footnote 23 Despite Mussolini's commendation, it is interesting to note how he praised the undertaking only after it was successfully accomplished. At the beginning, he had been quite cautious in supporting De Pinedo's proposal. As Gentile (Reference Gentile2003) claimed, Mussolini's political power between 1924 and 1925 was still precarious because the internal situation of the Fascist party threatened his role as charismatic leader and uncontested Duce. His leadership within the party was experiencing a serious crisis that jeopardised fascism itself. The situation became even more complicated as a result of Giacomo Matteotti's murder (Canali, Reference Canali2015). Thus, it is no wonder that Mussolini was cautious in granting governmental support in organising daring enterprises such as long-distance flights. The failure of such undertakings could compromise national prestige and the image of fascism. As mentioned at the beginning of this paper, De Pinedo promised to repay the entire cost of the seaplane in the event of failure and promised that his heirs would pay for the cost of the plane if he did not come back. This solution allowed the aviator to obtain Mussolini's final approval. A further evidence of this ambivalent attitude can be seen in September 1925, when General Umberto Nobile was setting up an Arctic exploration flight with the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen in the airship Norge. Mussolini only signed a document in which he approved of Italy giving the dirigible to the Norwegian Aero Club, but in doing so, Italy had no responsibility in the event of failure. It only would lose the airship. However, once the De Pinedo–Campanelli and Nobile–Amundsen flights were internationally successful, Mussolini immediately exploited them for political propaganda. In this regard, De Pinedo and Campanelli's achievement paved the way for the further successful flights accomplished by the Italian aviators between the 1920s and 1930s. A success that reach the peak with Balbo's trans-Atlantic flights in 1931 and 1933.

The regime popularised the voyage and De Pinedo's name in different ways. The landing dock on the Tevere River was named after the commander as Molo Francesco De Pinedo. Also, De Pinedo's statements were used in an enlistment campaign promoted by the Royal Italian Air Force Academy. In 1926, the feat was even celebrated in a goose game titled Il volo d'Oriente col ‘Gennariello’ (The Gennariello's flight across the Orient), which retraced the route of the seaplane in 80 illustrated slots. This board game was one of many produced during this period to popularise among children the ‘heroic’ personalities who had undertaken sensational endeavours. Such popularisation of De Pinedo and Campanelli's flight brings to investigate their view of Mussolini and the regime. Were the two aviators ‘eager fascists’ or airmen who wished to push the boundaries?

Due to the lack of evidence in this regard, we can only examine the vicissitude of De Pinedo and Campanelli following their flight to Australia, which could depict the two characters as airmen who wished to participate in the international competition for accomplishing record-breaking distance flights. Between the 1927 and 1929, De Pinedo did not agree with Italo Balbo, minister of the RIAF, who considered the RIAF as a formidable propaganda weapon. Their disagreement reached its peak in 1929, forcing De Pinedo to resign. Although Mussolini esteemed the aviator because of his aeronautical endeavours, he accepted his resignation (Ferrante, Reference Ferrante2005) and sent him to Argentina as military attaché in the Italian Embassy in Buenos Aires. In this context, Mussolini acted for avoiding further conflicts between De Pinedo and Balbo, which would eventually affect the image of the RIAF and the regime itself. As Ferrante (Reference Ferrante2005) noted, De Pinedo unenthusiastically accepted the new appointment, although he did not comply with the decision because he was a military man and used to obey to the orders. Analysing Campanelli's view of fascism is even more difficult because there are no documents related to the 1920s and 1930s in this regard. The only evidence dates to the 1943, when he decided to not endorse the Republica Sociale Italiana (established on 23 September 1943 after the fall of the regime on 25 July 1943). In the aftermath of the Armistice (8 September 1943), he decided to reach his family, as many other aviators did (Grassia, Reference Grassia2016), but he soon had to hide from the Nazis, who wanted to deported him in Germany in order to exploit his expertise in the aeronautical field, and from the partisans, who wanted to shoot him because of his aeronautical endeavours accomplished under the aegis of the regime (Cauli, Reference Cauli2008).Footnote 24

Despite its fame, the seaplane's fate was ‘inglorious’. In June 1944, members of a RAAF squadron accidentally discovered its wreck in Guidonia, near Rome, after noticing the Point Cook Flying School crest painted on the seaplane's hull. It had been put there by De Pinedo in recognition of the RAAF's assistance received during his stay in Melbourne (Figures 9 and 10).

Figure 9. Members of a RAAF squadron observing the Point Cook Flying School crest painted on the seaplane's hull. (Courtesy of The Royal Australian Air Force Museum, Point Cook, Melbourne.)

Figure 10. Guidonia (Rome), the wreck of Gennariello in June 1944. (Courtesy of The Royal Australian Air Force Museum, Point Cook, Melbourne.)

So, what is the cultural legacy of De Pinedo and Campanelli in modern Italy and Australia 95 years later? On one side, the Italian desire to ‘ignore’ the exploits, and those who undertook them, that were accomplished during the fascist era, contributed to De Pinedo and Campanelli's achievement being forgotten for a long time. Finally, in 1971, the Italian national air company Alitalia named one of its Boeing 747-243B after De Pinedo, calling it the I-Demo Francesco De Pinedo. In 1975, Rome and Melbourne issued a special postmark commemorating the 50th anniversary of the flight, which was used to stamp airmail sent from Melbourne to Fiumicino Airport on 16 and 17 July. Also, in 2005, Italian Post issued special postcards to commemorate De Pinedo's flight's 80th anniversary for National Aero-Philatelic Day (a day for specialists in aeronautical postal history). In 2007, Oristano, the town where Ernesto Campanelli spent his youth, named its airport after him and the Province of Oristano and Italian Post issued a special postmark to celebrate the event. Finally, in 2015, the Sardinian newspaper L'Unione Sarda published an article celebrating the 90th anniversary of De Pinedo and Campanelli's flight to Australia and Japan.

The legacy in Australia was different. From 1926 until 1931, the passage of the two Italian airmen was recalled in the Official Year Book of the Commonwealth of Australia. In 1956, the book Centenary History of Port Adelaide 1856–1956 recorded the arrival of the two airmen in the section ‘distinguished visitors to the city’ (Lumbers, Reference Lumbers1956). In 2000, Australian Post issued a special postmark to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the flight. A further contribution to disseminate the legacy of De Pinedo and Campanelli's visit to the Australian coast came from the Italian community through the Italian–Australian newspaper Il Globo, which in 1968 and 2005 published two articles to commemorate, respectively, the 43rd and 80th anniversaries of the airmen's arrival in Australia (Cauli, Reference Cauli2008). These articles also suggest that the propagandistic purpose of the flight did not create a political issue in Australia. Australians were instead genuinely fascinated by the novelty represented by De Pinedo and Campanelli's flight, as the accounts published in the Australian press analysed in this paper have revealed.

7. Conclusion

The arrival of the Italian seaplane in Australia created admiration and curiosity in the public. Specifically, the landings in Perth, Adelaide and Melbourne brought the popularity of the airmen and their exploit to the highest level. The press played a pivotal role in making the two Italian airmen familiar to Australian readers, because of its continuous interest in the flight's progress through accounts often enriched with technical information about the seaplane and the route map. Furthermore, the commercial companies involved in the fight contributed to popularising De Pinedo's feat by associating his name with their marketing strategies. The aviators’ names, published in commercial advertisements, became synonymous with the reliability and high performance of their products, which were seen as necessary for the accomplishment of sensational feats. The evidence analysed in this paper shows that their long-distance flight, and the seaplane itself, were perceived by many as a novelty. From this perspective, their exploit shows that the spectacle of the flight, as defined by the aviation historian Robert Wohl (Reference Wohl2005), was able to stimulate the imagination of the public and turned the aviators into celebrities. Thus, De Pinedo and Campanelli should be considered as the forerunners of modern aeronautical spectacles, and although their feat was sporadically recorded, especially in Italy, its legacy still fascinates both the Australian and Italian public, as this analysis has proved. This paper has examined only a section of the flight; but it can be considered as the basis to undertake further analysis to reconstruct and examine the whole flight, throwing light on how it was perceived globally, and its political entanglements.