INTRODUCTION

A few months before the 2020 hajj, the Senegalese government announced that, following instructions from Saudi Arabia, it would cancel the holy pilgrimage. The expected 13,000 Senegalese pilgrims were to stay home. The government then ordered private hajj travel agencies not to collect any money from the pilgrims and to refrain from signing any contracts with lodging, transportation and other accommodation providers in Saudi Arabia.Footnote 1 Even if about 85% of pilgrims have been travelling to Mecca with private hajj agencies since 2016, the Senegalese state once again found itself as the indisputable gatekeeper between its citizens and the outside world. The neoliberal turn and its ‘laissez-faire’ creed, it appears, has not erased the central role of the state. More generally, as Lecocq argues, with a historical perspective, ‘the organisation of the hajj became a state affair, organised first by the colonial authorities, and by the postcolonial states subsequently’ (Lecocq Reference Lecocq2012: 189). In this context, we ask how has the Senegalese state organised the hajj and managed its relations with the various actors evolving in this field, mainly pilgrims, private agencies,Footnote 2 religious leaders and political actors? Specifically, what shaped the Senegalese state's management of the hajj since the liberalisation of the hajj in the early 2000s?

To answer these questions, this article argues that three inter-related imperatives structure the state organisation of the hajj in Senegal: a security imperative, a legitimation imperative, and a clientelistic imperative. We have identified these three imperatives through a thorough review of the literature that studies the political management of the hajj in various countries and time periods. We then use them to analyse the hajj in Senegal since the outset of its liberalisation around 2000. In a nutshell, the colonial and post-colonial states in Senegal have been driven by security concerns in the organisation of the hajj, as seen in state officials’ attempts at controlling the circulation of individuals, ideas and diseases between the homeland and the Holy Places, which resulted in surveillance, rationalisation and ‘legibility’ (Scott Reference Scott1998) policies. But at the same time, given the utmost importance of this sacred ritual, the successful organisation of the pilgrimage is also a legitimation tool, as state officials associate themselves with religious leaders and frame themselves as the providers of a public service. Finally, the clientelism imperative stems from the circulation and accumulation of the massive amount of financial, political and symbolic capital circulating in the field of the hajj. More generally, then, we contend that the hajj organisation constitutes an original viewpoint to observe the interrelated influences of political, religious and economic relations in the construction of the state in Senegal.

Research for this paper was carried out during fieldwork in Dakar in May–July 2017 and May–July 2018, during which we have conducted 70 semi-structured interviews with entrepreneurs of the hajj, state officials and pilgrims.Footnote 3 We have also done non-participant observation in hajj training sessions organised by private agencies, while also observing the daily interactions as they unfold in these agencies. Finally, we have carried out archival research in Senegal's National Archives, at the state-owned newspaper Le Soleil (1960–2015), while also collecting data from online Senegalese newspapers (2010–2020).

The remainder of the paper is divided in three sections. First, we undertake a review of the literature that studies the role of the state in the organisation of the hajj across various regions and time periods. From this review we have identified the three above mentioned imperatives. Second, we provide a brief overview of the Senegalese state's handling of the hajj organisation since Independence. Finally, we analyse closely how each of these imperatives has shaped the Senegalese state's management of the hajj over time.

THE STATE AND THE HAJJ: A REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

The hajj is a religious ritual, but its actual organisation has profound political implications: ‘The hallmark of the modern hajj is that it is an affair of state. Every government with a sizable Muslim population has promulgated a hajj policy in the hope that new services will win over grateful pilgrims and new restrictions will ward off potential troublemakers’ (Bianchi Reference Bianchi2004: 70). Hence, this section reviews the literature that specifically studies the role of the state in the management of the hajj in different periods and locations. Our goal is not to provide a sequential description of the various policies adopted by states over time, but to identify recurrent patterns, or imperatives. Two observations ought to be made before we dive into this literature: first, the share of studies devoted to the colonial period significantly outnumbers that of the post-colonial era. This gap ought to be filled. Second, and relatedly, there is little research on how the organisation of the hajj relates to electoral politics and patronage in the post-colonial era, especially in the post-Cold War period, with a few but highly significant exceptions such as Bianchi (Reference Bianchi2004, Reference Bianchi, Mols and Buitelaar2015, Reference Bianchi, Tagliacozzo and Toorawa2016, Reference Bianchi2017), Madore & Traoré (Reference Madore and Traoré2018) and Katz (Reference Katz2019). Finally, few studies scrutinise the impact which liberalisation reforms have had on the organisation of the hajj. To borrow from this ingenious media headline, little is known about today's politics of ‘Hajjonomics’ in those states that send thousands and hundreds of thousands of pilgrims to the Holy Places.Footnote 4

Many studies have shown that colonial and post-colonial states have been driven by a security imperative in their endeavour to manage the movement of pilgrims. In many instances, especially during the colonial era, this imperative was predicated upon the combined fears of political Islam and health risks. Several authors have captured the historical construction of this two-sided representation: Roff (Reference Roff1982) discusses the ‘sanitation and security threats’, while Chantre (Reference Chantre2013a: Reference Chantre2018) talks about the relation ‘between pandemics and pan-Islamism’, and Slight (Reference Slight2013) refers to the ‘twin poles of the imperial Hajj’. As Huber (Reference Huber, Tagliacozzo and Toorawa2015: 179) eloquently explained, in imperial representations, ‘bacteriological contagion came to be coupled with the contagiousness of political ideas that pilgrims were exposed to while in Mecca’ (see also Ryad Reference Ryad2017: 1).

Given these representations, colonial authorities securitised the hajj through a large repertoire of policies of control, surveillance and repression. It was in South Asia and South East Asia that European colonisers instigated the first systematic experiments in securitising the hajj. For instance, at the time of maritime transportation, colonial authorities in the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) feared ‘contamination and transgression onboard’ (Alexanderson Reference Alexanderson2014: 1023), envisioning the travel to the Holy Places as a journey on ‘subversive seas’ which required tight surveillance (Chiffoleau Reference Chiffoleau, Tagliacozzo and Toorawa2015; Tagliacozzo Reference Tagliacozzo, Tagliacozzo and Toorawa2015; Tantri Reference Tantri2016; Alexanderson Reference Alexanderson2019). In British India, authorities used a more laissez-faire approach than their Dutch counterparts since 1858 (following the 1857 Sepoy Rebellion), but their strategies of surveillance of pandemics and political Islam were enhanced by the 1870s (Low Reference Low2008: 282; Mishra Reference Mishra2011; Slight Reference Slight2015, Reference Slight and Ryad2017; Tagliacozzo Reference Tagliacozzo, Tagliacozzo and Toorawa2015). From then on, in a context where the Ottoman Sultan Abdulahmid II called for the unity of Muslims around the world, colonial powers (Dutch, British, French and Russian) consolidated their policy of control (Chiffoleau Reference Chiffoleau, Tagliacozzo and Toorawa2015: 109, 118; Chantre Reference Chantre2018).

French authorities in North Africa, inspired by their European rivals, though more in line with the restraining approach of the Dutch than that of the British in India (Chiffoleau Reference Chiffoleau, Chiffoleau and Madoeuf2005: 139), developed networks of surveillance and attempted the same ‘separation’ policy on the boats departing from North Africa (Campbell Reference Campbell2014; Chantre Reference Chantre2018). In British Nigeria, the ‘Nigerian Pilgrimage Scheme of 1919–1936’ followed a similar pattern (Heaton Reference Heaton, Falola and Heaton2007). In the most extreme cases, such as major epidemics or major political turmoil or world wars, they simply called off the hajj (D'Agostini Reference D'Agostini and Ryad2017: 113–15).

States also implemented more subtle policies, which we argue are similar to practices which Scott (Reference Scott1998) denoted through the concept of ‘legibility’, that is policies that seek to standardise and simplify social patterns to make society easier to understand and control. As Bianchi (Reference Bianchi2004: 70) argues, state pilgrimage officials ‘enveloped pilgrimage in detailed rules, often with more zeal for surveillance than service’. Campbell adds that ‘“Ordering” the hajj meant creating modern travellers, as well as modern subjects who were better knowable and reachable by the state’ (Campbell Reference Campbell2014: 265–66; emphasis added). Gradually, by the middle of the 19th century, states also developed such policies through an international health regime, with the first series of international health conferences (Chiffoleau Reference Chiffoleau2011, Reference Chiffoleau2016; Huber Reference Huber, Tagliacozzo and Toorawa2015; Chantre Reference Chantre2018). This legibility approach can be seen in the first orders to impose passports on pilgrims, as soon as 1825 for the Dutch East Indies (Chiffoleau Reference Chiffoleau2016: 2), by 1846 in French Algeria (Chiffoleau Reference Chiffoleau, Chiffoleau and Madoeuf2005: 137) and in 1881 in the British Strait Settlements (Roff Reference Roff1982: 372; Low Reference Low2008: 282). By 1926, the Saudi instructed all pilgrims to carry a passport (Chiffoleau Reference Chiffoleau, Tagliacozzo and Toorawa2015: 18). Increasingly, colonial states and then post-colonial states refined the administrative tools that made pilgrims more legible, a real ‘identificatory revolution’ (Chantre Reference Chantre2018: 433) including: the obligation to travel with state-approved companies and to follow ‘official routes’ while forbidding the ‘illicit’ pilgrimage; to carry a health certificate; to fill out personal finances forms and so on (Laffan Reference Laffan2002; Bianchi Reference Bianchi2004: 215; Heaton Reference Heaton, Falola and Heaton2007; Ichwan Reference Ichwan2008: 126–27; Miran Reference Miran2015). The rising influence of the New Public Management paradigm in the 1990s and the computerisation of administrative processes have consolidated this process of legibility in the organisation of the hajj (banking transactions; identification of pilgrims; health examinations; booking procedures; etc.) (Bayart Reference Bayart2004; Ali et al. Reference Ali, Basir and Ahmadun2016). More generally, as Huber compellingly argues, new technologies now carry ‘the promise of making the pilgrim body visible wherever its location’ (Huber Reference Huber, Tagliacozzo and Toorawa2015: 194; emphasis added).

Security concerns overlapped with another imperative: legitimation. The literature, which focuses for the most part on the colonial era, shows how imperial authorities used the hajj to attempt to appear benevolent towards their Muslim subjects and to lessen anticolonial sentiments (Lecocq Reference Lecocq2012; D'Agostini Reference D'Agostini and Ryad2017: 112). This can be seen in the case of British India, where authorities sought to maintain ‘the “legitimacy” of colonial rule by respecting the “religious law” of indigenous communities’ (Elfenbein Reference Elfenbein2015: 263), facilitating the hajj, short of providing direct subsidies to pilgrims (Elfenbein Reference Elfenbein2015: 264–5; Lombardo Reference Lombardo2016). Their efforts ‘to ameliorate the sufferings of India's destitute pilgrims were a consistent feature of the British Empire's management of the Hajj from the 1870s until the era of decolonization’ (Low Reference Low and Ryad2017: 78). In colonial Tunisia (Chantre Reference Chantre2013b), in Algeria (Chiffoleau Reference Chiffoleau2016, 8; D'Agostini Reference D'Agostini and Ryad2017: 114), and later in West Africa (Lecocq Reference Lecocq2012: 197–8), authorities aimed at framing France as a ‘Muslim power’, that is, as a ‘solicitous and accommodating empire’ (Mann & Lecocq Reference Mann and Lecocq2007: 368), hoping to make French rule ‘acceptable, even if [the French] could not fully persuade them that it was legitimate’ (Reference Mann and Lecocq2007: 371).

Fewer studies investigate the post-colonial era, but those that do indicate that post-colonial leaders face a different set of constraints than their colonial predecessors, the main one being the requirement to legitimise their newly independent state. A central legitimation strategy consists in framing the organisation of the hajj as a public service (Darmadi Reference Darmadi2013: 448), as a constitutive element of the post-colonial state's larger mission of nation-building and development. In Malaysia, the state hajj agency was tasked with a mission of ‘national economic development and nation-building’ (McDonnell Reference McDonnell, Eickerlman and Piscatori1990: 112; Miller Reference Miller2006: 225), while in neighbouring Indonesia the state sought to ‘maintain its “national” project to control the Hajj’ (Darmadi Reference Darmadi2013: 445). Both the Indonesian and Turkish governments also used the hajj ‘to improve the position of women and rural citizens’ (Bianchi Reference Bianchi, Mols and Buitelaar2015: 74). For their part, Indian courts proclaimed the hajj as a ‘public service’ that needs to be inclusive, ‘particularly for the poor’ (Elfenbein Reference Elfenbein2015: 258). As for Pakistan, the government of Benazir Bhutto ‘use[d] pilgrimage to help a wide range of aggrieved groups enter the social and economic mainstream’ (Bianchi Reference Bianchi2004: 97).

Post-colonial states’ legitimation efforts also depend on the relationship they develop with influential non-state Islamic figures and organisations, which often have deeper and stronger roots in society. Of course, the nature of these relations may vary significantly; collaborative relations are not a given. For instance, Bianchi (Reference Bianchi2004: 78) shows that in Pakistan, under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (1973–1977), the Islamic elites viewed the new state hajj agency as ‘a raiding party, probing their flanks and signalling the state's intention to strike at the heart of their wealth and power’ and fought his regime fiercely.

Finally, we have identified a third recurrent imperative in the literature, which we call a ‘clientelistic imperative’. As many authors demonstrate, the religious, political, social and economic value of the hajj makes it prone to the development of relations of clientelism. As the colonial and post-colonial states increasingly gained control over the hajj, officials became unavoidable gatekeepers with whom pilgrims, religious leaders and businessmen have had to curry favour (Donnan Reference Donnan1989: 213). Scholars of the colonial era show that a widespread mechanism of clientelism took the form of ‘sponsoring’ the hajj, by which local elites would exchange their loyalty to the colonial state and would then ‘benefit from the state's calculated patronage’ (Donnan Reference Donnan1989; Mann & Lecocq Reference Mann and Lecocq2007: 373; Darmadi Reference Darmadi2013: 455–6). In colonial Northern Nigeria, for instance, the hajj was seen as a ‘major reward for the “good behaviour” of Northern Emirs’ (Tangban Reference Tangban1991: 242; Lecocq Reference Lecocq2012: 201), while in neighbouring colonial Cameroon, French authorities ‘reward[ed] those Muslims that were faithful to the French’ (Adama Reference Adama2009: 124).

In the post-colonial era, and with the development of air travel, the scope and extent of clientelistic dynamics increased with the number of pilgrims travelling to Saudi Arabia and the amount of financial resources that came with it. As Bianchi contends, ‘a lucrative and centrally controlled Hajj business provided enormous incentives for all groups to grab a share of the soaring profits and patronage in every country with a sizable Muslim population’ (Reference Bianchi, Tagliacozzo and Toorawa2016: 135; also Bianchi Reference Bianchi2017: 3). In the most populous Muslim states, such as Indonesia, India, Pakistan or Bangladesh, the 1988 decision by the Saudis to impose quotas based on a country's population (1000 pilgrims per million Muslims) heightened the gatekeeper role of the state, hence the politics of clientelism (Bianchi Reference Bianchi2004: 51–2). Although more impartial mechanisms such as lotteries may be used to minimise these problems, they are not flawless. For instance, in 2019 the Indian government ran a lottery for the hajj packages it sells, but the demand significantly exceeded the offer (267,000 applicants for 140,000 available packages).Footnote 5 Furthermore, as some studies have shown, party politics amplifies these clientelistic dynamics: in Indonesia and Turkey, Bianchi argues (Reference Bianchi, Mols and Buitelaar2015: 65), ‘[s]tate sponsorship of the Hajj generates a steady stream of scandals, subsidies, services, contracts, investments, and patronage’. Looking at the case of Côte d'Ivoire, Madore & Traoré (Reference Madore and Traoré2018) persuasively demonstrate how, since the democratisation era of the 1990s, the Ivoirian state used patronage schemes to both coopt and marginalise Islamic associations that had a stake in the management of the hajj. Similar patterns were seen in a diverse set of countries, such as Pakistan (Donnan Reference Donnan1989: 214), Nigeria (Pérouse de Montclos Reference Pérouse de Montclos2017: 281), Burkina Faso (Oubda Reference Oubda2003: 75), Côte d'Ivoire (Cissé Reference Cissé, Holder and Sow2014; Savadogo Reference Savadogo, Holder and Sow2014; Traoré Reference Traoré2015) as well as Russia (Naganawa Reference Naganawa, Papas, Welsford and Zarcone2012: 314; Kane Reference Kane2015).

Overall, our survey of the literature that studies the role of colonial and post-colonial states’ management of the hajj enabled us to identify what we call the three imperatives. Though there is indeed much variation across time and space, these imperatives provide a useful typology to decipher the Senegalese state's actions in managing the hajj. Before we do so, however, we provide a brief overview of the hajj organisation in Senegal.

THE STATE AND THE HAJJ IN SENEGAL: A BRIEF OVERVIEW

In Senegal, the colonial state was involved in the organisation of the hajj by the end of the 19th century, at first mostly as an overseer, and increasingly so as an organiser. After the Second World War, colonial authorities institutionalised a model that was to survive up until today: an official state ‘Mission’ was tasked with organising the hajj, made of administrators and doctors (Mbacké Reference Mbacké1991: 271–2). Soon after gaining its Independence, in 1963, the Senghor administration (1960–1981) instituted a Commissariat général au pèlerinage, to be reconvened every year, under the supervision of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs,Footnote 6 and led by a Commissaire who was appointed by the President. This structure barely changed, up until 2009, when the Wade government (2000–2012) converted this yearly organisation into a permanent state agency,Footnote 7 still supervised by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. President Sall (2012–current) undertook a major reform in 2015–2016, abolishing the Commissariat Footnote 8 whose reputation has been tarnished by mismanagement scandals, and replacing it with a Délégation générale au Pèlerinage aux Lieux saints de l'Islam, still under the supervision of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.Footnote 9 The Délégué général and his Deputy are appointed by presidential decree.Footnote 10 This reform also imposed stricter conditions (cahier des charges) on private agencies running a hajj business, as we discuss further below.

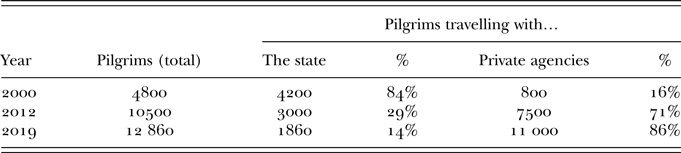

With these reforms, the state increasingly liberalised the field, as shown in Table I. Whereas the state agency was in charge of almost all pilgrims from the 1960s to the mid-1990s, the global context of neoliberal reforms imposed from abroad led to a phase of liberalisation of the public sector and industries (Ndiaye Reference Ndiaye and Diop2013), which eventually hit, though with some delay, the hajj sector as well. In 1999, the year before Wade's election, Commissaire Mbaye declared that ‘Any association or private agency is free to take pilgrims in charge’.Footnote 11 After his election, Wade accelerated the liberalisation of the sector: in his first year in power, 16% of pilgrims travelled with private agencies; that number rose to 65% by the end of his second term. Since Macky Sall took over, that number has increased to about 85%. However, as we will explain below, despite the liberalisation of the hajj, the state maintains much power, as a gatekeeper, a regulator and supervisor.

Table I Number of Senegalese pilgrims and the organisations with which they travelled to Saudi Arabia

Sources: Le Soleil 15.2.2000; Wal Fadjri 24.8.2012; Le Quotidien 12.7.2019.

SECURITISING AND SURVEILLING THE HAJJ IN SENEGAL

The security imperative has structured the Senegalese state's actions in the field of the hajj in different ways. Since the liberalisation turn, after 2000, we did not find clear evidence suggesting that the Senegalese state was particularly worried about the hajj–Islamism nexus. Historically, its colonial predecessor did put in place a surveillance apparatus to monitor the pilgrims and the potential ‘Wahabi’ encounters they could make abroad (Robinson Reference Robinson2000: 150–1; Mann & Lecocq Reference Mann and Lecocq2007; Hardy & Semin Reference Hardy and Semin2009: 140; Diawara Reference Diawara2012: 97). Similarly, in the post-colonial era, the Iranian revolution (Mbacké Reference Mbacké1991: 463) and the growing number of Senegalese students trained in North African and Middle Eastern countries, the Arabisants with a reformist inclination (Brossier Reference Brossier2016), maintained a certain level of suspicion about global Islamism. But since 2000, and despite the dominant geopolitical narrative of the ‘Global war on terror’ (Jourde Reference Jourde2007), we did not see clear effects of this anxiety in the organisation of the hajj. There might be one exception, however. This older fear of ‘pan-Islamism’ may manifest itself in a pattern that was initiated right after the Second World War and which has endured up until today: post-colonial governments have always nominated Commissaires (called Délégué Général since 2016) who are closely associated with the two largest Sûfi orders, the Tijâniyya and the Mûridiyya, and not a single one associated with Islamist (or ‘Reformist’) movements.Footnote 12 This proximity between the state and the Sûfi orders in the management of the hajj (which we discuss further below), as well as its corollary, the exclusion of leading figures of the Islamist movements, may suggest the Senegalese state's persistent understanding of Islamist figures and organisations as potentially subversive.

The literature we surveyed above indicated that beyond the question of ‘subversive’ ideas and movements, the securitisation of the hajj also included the deployment of administrative tools that aimed at better controlling the pilgrims, by making them more legible (Scott Reference Scott1998), or visible (Huber Reference Huber, Tagliacozzo and Toorawa2015). This pattern is clearly seen in Senegal. But the issue of the liberalisation of the hajj organisation complicated this question. Initially, the pressure to liberalise met fierce resistance from state officials, who refused to let go and give non-state actors a bigger role in the hajj organisation due to security concerns. Their fear of private actors echoed that of their colonial predecessors, ‘who recognized that the expansion of the commercial market meant that they would lose what little knowledge they had of who went, where they stayed, and with whom they conversed’ (Mann & Lecocq Reference Mann and Lecocq2007: 375). This could be seen in Commissaire Mbaye's declaration in 1990: ‘nobody else but the state can organize the pilgrimage and provide the necessary security conditions … The state should never surrender this obligation, this task, to individuals or organizations’.Footnote 13 And as a former assistant to Commissaire Mbaye told us: ‘We did not want to hear anything about the private sector! … We fought that battle because we knew that the interest of the pilgrim was not in the private sector.’Footnote 14 This explains why, by the mid-1990s, only a few well-established tourism agencies were allowed to develop a new ‘hajj’ niche.

But probably due to the combined effects of the structural adjustment programmes and President Wade's own liberal orientation, the state did embark upon a clear liberalisation path by 2000. However, the imperative to securitise the pilgrimage and make pilgrims more visible did not recede. In fact, during the liberalisation phase the Senegalese state maintained, if not perfected, its capacity of control through what Hibou (Reference Hibou1999) calls a process of décharge. As the Délégué general told us in 2017, ‘it's true that the trip itself [‘convoyage’] can be given to private agencies, but as to the security of the Senegalese and the conditions in which they do the hajj, this is the responsibility of the state. Even if it is a religious event … it has a security dimension.’Footnote 15 Such policies included the health sector, as Diawara's (Reference Diawara2012) fascinating work shows. Building on previous colonial policies, and on Saudi requirements, the Senegalese government makes it mandatory for pilgrims to carry a vaccination certificate and to attend a medical examination (which was decentralised across the country in 2010).Footnote 16 Although, it must be noted, governmental rules are not always fully observed: travel agency owners told us that in reality it is difficult to deny an elderly person to do the hajj when a relative is financing the trip.Footnote 17 The state also developed procedures that sought to better monitor and standardise social practices, such as culinary practices. For instance, since the 1960s Senegalese cooks always accompanied pilgrims and cooked for them in Saudi Arabia. But Saudi authorities eventually judged their culinary practices as unsanitary, which led the Senegalese Commission to create a ‘hygiene team’ in the mid-1980s to monitor the cooks.Footnote 18 In the eyes of the 2002 Commissaire, a more coercive policy was needed, and the hygiene team visited the kitchens with the support of police officers.Footnote 19 He stated that ‘any cook who does not follow the hygiene code of conduct will have their licence removed’.Footnote 20 In 2014, after a series of deadly fires spread in informal kitchens, tighter rules were passed: the Saudis made it mandatory to pay for local government-approved subcontractors for all cooking activities; Senegalese cooks could no longer cook and sell their meals to the pilgrims.Footnote 21 However, some cooks pleaded their case to the Commissaire and were given the right to cook classic Senegalese dishes such as ceebu jeen, yaasa or mafé, as long as they were supervised by the hotels and served the meal in the refectory.Footnote 22

More generally, through the 2016 reform of the hajj, which we presented above, the state imposes strict specifications to private agencies, which allows it to exert a tight control over those who try to make it into the hajj sector. Also, by the mid-2000s, the state implemented more developed technologies of surveillance at the country's airport which, combined with the obligation for pilgrims to carry a biometric passport (since 2009, following Saudi requests),Footnote 23 heightens its capacity to know more about its citizens (Sandor Reference Sandor2016; Frowd Reference Frowd2017). Though these new technological tools may not be as efficient in practice as they seem (Sandor Reference Sandor2016; Frowd Reference Frowd2017), they do demonstrate the Senegalese state's attempt at consolidating its security policies of information-gathering and monitoring despite having privatised the organisation of the hajj.

ATTEMPTING TO MAKE THE STATE MORE LEGITIMATE

As indicated in our review of the literature, legitimation constitutes a second fundamental imperative in the state's organisation of the hajj. In Senegal, the most obvious instantiation of this imperative manifests itself in the state's close collaboration with Sûfi religious families. Let us recall that during the colonial era, as Robinson's (Reference Robinson2000) concept of the ‘Path of Accommodation’ indicates, French officials sought to legitimise their rule by developing accommodative relations with Sûfi leaders. With respect to the hajj specifically, this was seen in colonial authorities’ appointment of Sûfi figures as ‘General Delegates’ in the yearly hajj mission d'encadrement, such as Abdel Aziz Sy, the khalîf of the Tijâniyya in 1949,Footnote 24 or Seydou Nourou Tall, khalîf of the Tijâniyya Umariyya, in 1952.Footnote 25

Upon Independence, post-colonial officials reproduced and adapted this relationship, well captured by Cruise O'Brien's concept of the ‘Senegalese Social Contract’ (Cruise O'Brien Reference Cruise O'Brien1992; Villalón Reference Villalón1994; Beck Reference Beck1997; Audrain Reference Audrain2004). Regarding the organisation of the hajj specifically, this translated into the nomination of the Commissaires (and later Délégué general): as explained above, all the Commissaires have been known disciples of Sûfi orders, either the Tijâniyya or the Murîdiyya. None came from Islamist ranks. These include Rawane Mbaye (1984–2001) who was very close to the ruling family in Tivaouane; Cheikh Tidiane Aliou Cissé (2002), a grandson of al Hajj Ibrahima Niass (Niassiyya branch of the Tijâniyya);Footnote 26 Thierno Ka (2003–2004); a Tijâni; El Hadji Moustapha Gueye (2005–2007), also associated to the Niassiyya of the Tijâniyya; Thierno Ibrahima Diakhaté (2008–2009), a Mûrid; El Hadj Mansour Diop, a Tijâni (2010–2012). As for the current Délégué Général, Abdoul Aziz Kébé, appointed in 2016, he is also close to the Tijâniyya leadership (Tivaouane branch).Footnote 27 For the most part, as an informant explained, the office of the Commissaire is a chasse-gardée (a ‘preserve’) of the Tijâniyya.Footnote 28 Also, since 2003, the state hajj agency (then led by Commissaire Ka, a well-known professor of Islamic studies) has institutionalised the annual visit of the Commission to the country's ruling Sûfi families prior to the hajj, thereby confirming their close proximity and mutual recognition.Footnote 29 For the 2019 hajj, the Délégation visited the headquarters of each of the largest Sûfi families in the towns of Tivaouane, Kaolack and Touba.Footnote 30 It visited some of them again a few months later at the end of 2019, during which the Khalif of the Mûridiyya offered its blessing to the Délégation. Footnote 31 As well, the Délégation Générale celebrated the ruling Sufi families on its Facebook page and YouTube channel, with a series of posts with pictures of the most important Sufi families’ historical figures or their close relatives and a description of the pilgrimage they had performed.Footnote 32 Furthermore, the state hajj agency has granted Sufi families licences to run private agencies. For instance, the Medina Gounass branch of the Tijâniyya operates the agency with the largest quota in the country, with more than 500;Footnote 33 the Tall branch of the Tijâniyya also operates two agencies, and so on.

Framing the hajj organisation as a public service constitutes another instantiation of the legitimation imperative. Our review of the literature indicated that the era of Independence changed how the new post-colonial officials tried to legitimise their rule: in Senegal as in many other countries, officials sought to convince their citizens that the state was no longer a foreign, coercive and tax-extracting apparatus, but rather a national institution whose mission was to serve them and enhance their welfare. The hajj was part of this public mission. Though this was obviously the case during most of the ‘state-led’ organisation of the hajj between 1960 and 2000, it remained so after the liberalisation turn, even if this meant that the state depicted itself more as a regulator and supervisor than as a doer. For instance, in 2000, when President Wade fast-tracked the liberalisation of the hajj organisation, a high-ranking official at the Commission reminded his employees that ‘every supervisor ought to know that this is a true public service mission’.Footnote 34 Despite the liberalisation, state officials reproduced this public welfare, framing themselves as problem-solvers who could fix the unavoidable glitches of the hajj organisation, including, for example, the cases of pilgrims left at the airport; pilgrims getting lost and/or sick in Saudi Arabia without support; lost luggage; flight delays; inadequate lodging and food. Every year, the media renew this perpetual tension between, on the one hand, the criticisms of unhappy pilgrims who, upon their return to Senegal, vent their anger at the government in the media (‘Chronicle of a predictable fiasco!’),Footnote 35 and on the other hand, the Commissariat (or Délégation) which celebrates its work in a ‘Mission Accomplished’ tone (‘we were successful by a rate of 80%!’),Footnote 36 while expressing its readiness to resolve the problems for the following year.

In the same vein, every reform of the hajj organisation the government has implemented over the years was also justified through a public welfare problem-solving frame, conveying the idea that the government would improve its delivery of this essential public service, included during the liberalisation era. Immediately after his election in 2012, President Sall called for a complete audit of the Commissariat in an attempt to show that the state would correct past malfunctions in the delivery of services and the use of public resources for the hajj, a ritual that has a ‘very strong social dimension’ (IGE 2013: 37). Then, in 2015, his administration dismantled the state hajj agency after private agencies had left 300 pilgrims behind at Dakar's airportFootnote 37 and the Commissariat had mismanaged the aftermath of a deadly stampede that killed 2,400 pilgrims in Saudi Arabia, including 62 Senegalese.Footnote 38 The government declared that it would push for a ‘new dynamic of modernization and rational and rigorous management of the pilgrimage, for the benefit of all our compatriots’ (emphasis added).Footnote 39 As we explained above, the 2016 reform imposed very strict conditions on travel agencies intending to run a hajj business, including the obligation to apply for a three-year licence (agrément); to operate in a permanent physical office, with a full-time administrative staff and a religious guide (encadreur); to own a bank letter of guarantee; and to offer a formal and complete service proposal for the pilgrims (medical visits; training sessions; transportation; accommodation).Footnote 40 The Délégation then centralises all this information through a national electronic portal where private agencies carry out all the required operations, from visa applications and hotel reservations to paying the various fees.Footnote 41 Following a request from the Saudis, the Délégation pooled all the agencies into larger ‘groupings’ (regroupements).Footnote 42 The reform also set a maximum of pilgrims per agency (100) and per regroupement (600).Footnote 43 In addition, agencies must get the prices of their packages approved by the Délégation.Footnote 44 Importantly, when private agencies fail to meet these standards, they can be sued and their owners jailed, as happened to three of them in 2017.Footnote 45

Overall, although the state has granted more space to private agencies since 2000, it did so by continuing to frame itself as the ultimate promoter of its citizens’ welfare. This echoes what Donnan (Reference Donnan1989: 213) found in Pakistan, where ‘successive regimes have vied with each other to convince the nation that their hajj policy has been the most successful and the most equitable’. This public service frame, as a constitutive element of the legitimation imperative, continues to dictate how state officials envision their role. This was clear in how the Délégué général presented the role of the state, in spite of the overall liberalisation: ‘the state sold its shares, but it continues to be vigilant, because this is not a market of, say, books or whatever. We are talking about men and women, human beings. We can't leave it like this to the hands of predators in the name of religion.’Footnote 46 He restated his view two years later, saying that ‘the privatization of the pilgrimage, which [the President] wants, is beneficial for our country's economy because the state will remain within its functions, which are regulation, control and guidance’.Footnote 47 The Sufi-dominated Conseil supérieur islamique du Sénégal backed this position and declared that ‘the state should not opt out of the organisation of the hajj and leave all the organisation to private agencies’.Footnote 48

Finally, as the literature we reviewed above makes clear, the magnitude of financial and symbolic resources that circulate across the field of the hajj organisation also contributes to the development of clientelistic political relations.

THE HAJJ AS A BREEDING GROUND FOR CLIENTELISM

Various valued resources can feed clientelistic relations. These can include financial resources to perform the hajj, nominations on the state hajj agency commission, and the allocation of licences and quotas to operate private agencies.

The cost associated with the pilgrimage, including transportation, lodging and daily expenses, represents a major financial burden for most people and as such constitutes a potential leverage for clientelistic relations. State officials can use their access to public resources to finance entirely or in part the hajj of clients in exchange for political support. This practice, known as hajj-sponsoring, began in the colonial era, as Robinson (Reference Robinson2000: 80) has shown. It was reproduced in the post-colonial era, during the state-led phase (Diawara Reference Diawara2012: 259). Since the privatisation of the hajj under Wade, fewer pilgrims travel with the state, which minimises the clientelistic practice of the state's hajj sponsorship. But the quota of pilgrims still allocated to the state remained vulnerable to patronage. Evidence of this is not easy to find, given its illicit nature, but we can get some glimpses of it in auditing reports. As we explained above, right after his election, President Sall ordered two auditing agencies, the Cour des Comptes (Court of Audits) and the Inspection Générale de l’État (General State Inspectorate), to audit the state's handling of the hajj under Wade. Their reports shed light on clientelistic patterns related to the ‘hajj sponsorship’ practices. For instance, in 2010 and 2011, state agencies which have nothing to do with the pilgrimage were asked to transfer money to the presidency: the Post and Telecommunication agency transferred CFA36 million (US$63,000) to President Wade's chief of staff in matters related to the pilgrimage (Cour des Comptes 2013: 197), while the Public Housing Agency (SNHLM) was asked by the President's chief of staff to transfer more than CFA18 million (US$31,000) over four years (2008–2011) as ‘subsidies’ to pay for plane tickets for the hajj (Cour des Comptes 2014: 142–3). Also, staff members in the 2008 hajj were paid important sums of money without being officially part of the organisation (Cour des Comptes 2012: 116). For its part, the General State Inspectorate noted that the state hajj agency had accumulated a debt of CFA500 million (US$840,000) between 2008 and 2012 with Saudi hotels, a ‘consequence of the opacity of hajj-related contract negotiation by Commissariat officials' (IGE 2013: 41). It was also reported that President Wade gave hajj packages to mayors and other members of his Presidential coalition, called CAP 21,Footnote 49 paying for their flights as well as their expenses in Saudi Arabia.Footnote 50 These problems may have contributed to the major 2016 reform. As an official at the Délégation told us, the reform was needed because ‘there was too much “business” going on’. ‘Well … “corruption”’ said the person who introduced us and was attending the discussion.Footnote 51

Another major conduit for clientelistic relations is nested in nomination of members of the hajj agency's ‘Supervision Mission’, made of encadreurs (supervisors), tasked with supporting the Commissaire and the pilgrims in Saudi Arabia. Securing the nomination as a supervisor is a source of financial and symbolic benefits.Footnote 52 Established in 1949, and growing in size over the years, the Mission was accused of being a breeding ground of patronage since its inception (Mbacké Reference Mbacké1991: 283). These suspicions continued in the post-colonial era, as a high-ranking hajj official told us: ‘The choice of encadreurs was sometimes politically motivated … When the marabout gives the name of five people that should go to Mecca, another marabout does it as well, and a traditional leader, etc., and this is what instrumentalisation is about.’Footnote 53 It has to be said that the amount of resources spent on the encadreurs is significant: in its 2013 report, the State General Inspectorate noted that as much as 77% of the Commissariat's budget for 2008 was devoted to the payment and transportation of encadreurs (IGE 2013: 38). Although the privatisation of the hajj organisation at the turn of the millennium strongly reduced the number of encadreurs, given that the Commissariat was in charge of far fewer pilgrims, the clientelistic nature of these appointments does not seem to have subsided. For instance, in 2009, the Commissaire accused the minister of foreign affairs of ‘having directed him to appoint some of his kin from Saint-Louis on the list of encadreurs, which shows how clientelisms undermines this position [of the Commissaire]’.Footnote 54 The Commissaire was immediately fired and replaced by one of his deputies.Footnote 55 In 2015, a former supervisor publicly denounced another Commissaire, saying that he ‘has surrounded himself with military officers who are, in reality, his close kin. I would ironically compare the Commissaire to a “Haalpulaar dynasty” … One dares to say it, the Commissariat is rotten by scam.’Footnote 56

With the liberalisation of the field, a new site of potential clientelistic relations materialised: the allocation of licences to private travel agencies and the quota of pilgrims each agency is allowed to have. As explained above, the state now selects the private agencies allowed to enter the market through the allocation of licences (agréments) and apportions the quotas of pilgrims per agency. With the 2016 reform, 140 new agencies were given licences, in addition to the 145 that already existed, for a total of 285 agencies.Footnote 57 With the total number of pilgrims granted to Senegal by the Saudi authorities ranging around 10,000 and 12,000 between 2016 and 2019, the government's allocation of almost 300 licences meant that many of the new private agencies would be small, with a quota of barely 15 or 20 pilgrims. To make sure all these new agencies could get at least 15 pilgrims, many of the large agencies that existed prior to 2016 had to cut out about 10% of their quota to be redistributed to the small ones,Footnote 58 although some seem to have lost even more (one female travel agency owner says her quota dropped from 300 pilgrims to 90).Footnote 59 For the manager of one of the largest agencies, the reason why so many small agencies were allowed some quotas is political: ‘Which privatization of the hajj are we talking about? Those small agencies with, what, 10, 15, 20 pilgrims? How can these agencies be profitable at all? The state controls them, this is clearly a ‘divide-to-rule’ policy.’Footnote 60 In such a context, developing the right relations with state officials could therefore be important. As a travel agency owner explained to us, ‘the hajj, it is also a business, and it is highly political, you need to have connections in higher circles and build a network’.Footnote 61 Similarly, another travel agency owner told us that in the early 2000s, she used to have a quota of around 300 pilgrims. But she eventually got caught up in one of the many factional struggles that plagued the Wade presidency. When she refused to back one of her cousins, who at the time was an influential minister (and whose ministry had an official role to play in the hajj) and the leader of a vying faction, the Commissariat slashed her quota significantly the year after. Later, after Wade lost the presidency, the cousin apologised for what he had done to her.Footnote 62 Another female agency owner explained to us that even though her travel agency is very large (for which the hajj is just one sector in the whole tourism industry), the reason she has never been allocated more than 60 pilgrims, a small quota for such a large agency, is because she refuses to play the ‘game of politics’.Footnote 63 By contrast, one of her colleagues, who belongs to a powerful Sufi brotherhood, candidly admitted that the agency was granted a major extension in its quota after the 2016 reform due to a ‘favour’ by a high-ranking official.Footnote 64

Another agency owner added an interesting electoral twist to this game. As we were meeting with five agency owners belonging to the same association (regroupement), she explained to us why she had decided to create her own hajj agency: ‘For me, it is about politics. As simple as that. Politics brought me to the hajj business.’ A colleague who was sitting next to her described how it all works: ‘A local politician will send somebody at the Délégation, they'll arm-twist the Délégué général to impart some quota to a tradeswoman like her. And when it's election time, she will return the favour by mobilising her network for the politician.’Footnote 65 Of course, this is not to say that the entire process of quota allocation is rigged by clientelism. But the evidence suggests that the privatisation era has opened up a new window for patronage politics.

CONCLUSION

In this paper, we have demonstrated that the Senegalese state's management of the hajj since the turn of the millennium has been influenced by security, legitimation and clientelism imperatives. From the imposition of the first vaccination certificates to the hyper-centralisation of information made possible by the technological (computerisation) shift, the state acted as a gatekeeper between its citizens-qua-pilgrims and the outside world. But the Senegalese state is not just a surveillance apparatus, it also seeks the support of its citizens. To do so it perpetuated the historical collaboration with influential Sûfi families and attempted to improve the experience of the hajj. Even if the state no longer flies thousands of Senegalese pilgrims to the Holy Places, it has not surrendered to the laissez-faire credo. Rather, as Schmidt (Reference Schmidt2009: 524) says, it has opted for a faire-avec approach, ‘having market actors perform functions that the state generally did in the past, with clear rules as to what that should entail’. As we saw, the state made clear that it would continue to be a regulator, supervisor and arbitrator. Interestingly, the Covid-19 pandemic may confirm this central role of the state. The ‘Pandemic State’, as Flynn (Reference Flynn2020) aptly called it, is also at work in the organisation of the hajj. After all, the hajj is a ‘state affair’, as Lecocq (Reference Lecocq2012: 189) reminded us. The first state interventions in the hajj management in the mid-1850s were already largely due to the politics of epidemics. The latest pandemic will be no exception.

More generally, the Senegalese case combines many of the dynamics we have identified in our review of the literature and suggests that Senegal is not significantly different from other countries in how its state had managed the organisation of the hajj. But a future research project would need to compare the relative impact of each of these imperatives in different states. Our preliminary research carried out in Cameroon suggests, for instance, that the clientelistic imperative has more bearing on the organisation of the hajj there than it does in Senegal and, conversely, that the legitimacy imperative is less meaningful. Such comparative study would have to study at more length how regime type, as well as the history of state construction, both influence the relative weight of these imperatives on the state's management of the hajj.