We shall revise all the old articles and make them into new ones that will be just and noble.

(Patrice Lumumba, Speech at the ceremony of the proclamation of the Congo's Independence)

Independence provided African countries with an opportunity to break with the colonial past. While this opportunity was seized in many spheres, the decades after independence revealed that many colonial institutions were surprisingly durable. In part because of this durability of colonial institutions, many countries in Africa began being labelled as post-colonial.Footnote 1 While claims of colonial institutional persistence remain common today, especially in the institutional economics literature, they now are met with the opposing claim that the post-colonial label has faded in relevance over the more than 50 years since African independence (Young Reference Young2004; Maseland Reference Maseland2018).

This paper measures the post-coloniality of current legislation in French West Africa and offers preliminary tests of various explanations for colonial institutional endurance. The countries of French West Africa had the same coloniser, identical independence-era legislation, similar independence dates and have broadly similar background features. Despite this, our analysis reveals substantial differences in the degree to which colonial legislation persists into the present.

Colonial legislation is a formal institution that is embodied in text, and so examining its durability requires us to measure the extent to which a present document differs from a past document. This is a ‘text as data’ research question that is commonly overlooked in social science work.Footnote 2 To measure the distance between texts, we use textual analysis techniques borrowed from the information retrieval branch of computer science. Our approach allows us to transparently and precisely measure the degree of difference between texts.

We use this textual analysis to show that one cannot safely assume that colonial institutions have endured. Further, we document substantial variation in institutional persistence across countries with the same coloniser and in the same region of the world. For example, while Senegal retained a large amount of colonial legislation, Burkina Faso did not. We offer some preliminary tests of this cross-national variation in persistence of colonial institutions and find that total time under colonisation offers one of the best explanations for institutional persistence.

The institutional economics literature often relies on the colonial experience to explain current economic and political outcomes (e.g. Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001, Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2002). However, this form of analysis tends to collapse country-level experiences inside colonial groupings, so that all countries that shared a coloniser are thought of as homogenous in how colonialism impacted present outcomes (e.g. La Porta et al. Reference La Porta, Lopez-de Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1997, Reference La Porta, Lopez-de Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1999). This is odd, as there are many differences between countries that shared a common coloniser, such as political openness or levels of wealth. It seems reasonable then to suggest that institutional endurance may also vary within countries that share a coloniser, even though this variation is typically downplayed in cross-national empirical work. There is much pessimism in the central institutional economic result that institutions are largely a product of colonial history, and that these post-colonial institutions are self-reinforcing and have been more-or-less locked into place since decolonisation. We show that this pessimism is at least partially misplaced. Many French West African countries have largely abandoned the colonial aspects of the formal colonial institution that we study.

The next section summarises the current literature on institutional persistence. After examining the relevant literature, we explain why some countries are expected to retain more colonial legislation than others. This is followed by a description of our case selection, which takes advantage of the fact that French colonisation created a group of countries that had an identical penal code at independence. We then describe a method for measuring the distance between two texts. We use this method to analyse the degree of change between present and colonial legislation across countries and then we offer two preliminary analyses. The first examines institutional change over time in one country and the second examines why some countries retained more colonial legislation than others. We show that countries that were colonised for longer periods of time have present-day legislation that copies more from the colonial code than countries that were colonised for shorter periods of time.

LITERATURE

Institutions are often described as the ‘rules of the game’ (North Reference North1990). This typically includes both formal, written rules and more tacit norms and expectations. Institutions matter because they are thought to shape economic and political outcomes (e.g. Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001, Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2002; Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Iyer and Somanathan2005; Nunn Reference Nunn2008; Huillery Reference Huillery2009; Dell Reference Dell2010; Naritomi et al. Reference Naritomi, Soares and Assunção2012).Footnote 3

Institutions are also thought to generally persist over time, and there are many examples of institutions enduring for hundreds of years or even millennia (Wittfogel Reference Wittfogel1957; Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001, Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2002; Nunn Reference Nunn2008; Dell Reference Dell2010). In the immediate post-independence period in Africa, states were run in ways that drew heavily on colonial institutional templates,Footnote 4 leading them to be described as ‘post-colonial’. One classic example is Young (Reference Young1994), who makes the argument that post-independence African states borrowed norms, routines, institutions and ways of governing from colonisers.

Because these colonial institutions were designed for the benefit of the coloniser to the exclusion of the colonised, their endurance beyond the colonial era is often pointed to as the reason for post-independence authoritarianism in many countries (Mamdani Reference Mamdani1996). Differences in colonial history have also been linked to variation in property rights (Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001), the endurance of agricultural marketing boards (Bates Reference Bates1981), and many other contemporary development outcomes (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Iyer and Somanathan2005; Huillery Reference Huillery2009; Dell Reference Dell2010; Alonso Reference Alonso2011; Naritomi et al. Reference Naritomi, Soares and Assunção2012). Studies on specific, formal institutions also suggest that they are long-lasting and have impacts on present-day outcomes. For example, the legal origins literature posits that the legal system inherited from a coloniser (a country's ‘legal family’) has impacts on economic and political outcomes today, such as levels of shareholder protection (La Porta et al. Reference La Porta, Lopez-de Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1997, Reference La Porta, Lopez-de Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1999).

Much of the work on institutional persistence measures the outcomes of batches of institutions rather than studying the effect or persistence of a specific rule (Rodrik Reference Rodrik2007). This is of potential concern, as it means that most research on institutions studies how a game is played and then declares afterwards that all structure in the game was due to ‘the rules’. This blends all factors that could possibly influence social life into one compound treatment which is then dubbed ‘institutions’.Footnote 5 We eschew this approach by focusing on a specific, formal institution.

One of the prime sources of cross-national variation in institutions comes from differing colonial experiences. This work typically assumes that decay either doesn't happen, or it happens evenly across countries with the same coloniser. While the study of historical, and often colonial, institutions has taught us a great deal about the importance of history in explaining present outcomes, it has tended to either examine institutions in a single country or to examine many countries but homogenise their experiences (Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001; Jones Reference Jones2013). This homogenisation often occurs simply through the setup of empirical studies. For example, this homogenisation exists in cross-national studies that attempt to find the effect of colonial practices, such as those that are ‘extractive’ across many countries (e.g. Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001). It is also prevalent in a lesser form in every research design that uses a dummy variable to capture the influence of French or English colonial practices (e.g. La Porta et al. Reference La Porta, Lopez-de Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1997, Reference La Porta, Lopez-de Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1999). A French dummy in this context gives the effect of being colonised by France, implicitly ignoring heterogeneity in the effect of colonisation among former French colonies. While the influence of colonial dummies in much work suggests that on average the country of colonisation influences country-level institutions, there can be a great deal of variation around that average. Worse, this variation could be caused by persistent colonial institutions having different effects in different countries, or it could be caused by institutions not having persisted in some countries. These are distinct questions that, if possible, should be analysed separately.

While African states did originally borrow templates for governing from the colonisers, by the 1980s and 1990s many of these institutions had been changed or curtailed. Here the marketing boards example from Bates (Reference Bates1981) is useful, as today many countries have disbanded or reduced the scope of their marketing boards. This is only one example, but it suggests that colonial structures may fade unevenly across countries over time. Similarly, a decade after writing The African Colonial State in Comparative Perspective (1994), Young (Reference Young2004) argued that the overall decline of formal state politics had limited the utility of the post-colonial label. A similar fading of the influence of colonial legacies is apparent in Maseland (Reference Maseland2018), which finds that colonial origin has over time lost its ability to explain institutional or economic outcomes cross-nationally in Africa. Similarly, research on the endurance of legal institutions has found that the colonial penal code itself has largely not endured since the colonial era (Berinzon & Briggs Reference Berinzon and Briggs2016).

There is therefore ongoing debate on the extent to which African states remain post-colonial. Some aspects of African states, such as many borders, are clearly colonial creations. There is more debate over the post-colonial nature of governance and institutions. Our work adds to the ongoing debate about the usefulness of the post-colonial label and the endurance of colonial institutions in the independence period by creating precise, country-level measures of the post-coloniality of legislation, by focusing on formal institutions and using textual analysis, offering preliminary tests of explanations for why some countries have present laws that are more strongly informed by colonial-era legislation, and by focusing on neglected cases (Briggs Reference Briggs2017). In measuring the persistence of French colonial-era laws in West Africa, we also speak to this broader literature on institutional persistence and the extent to which we can claim that countries with similar colonial experiences can be expected to have similar institutional features today.

THEORY

Most of the cross-national literature on historical institutions assumes that institutions evolve evenly across countries over time. Examining legislation in French West Africa offers a useful test of this assumption. Aside from describing how institutional change varies across countries, we also examine how cross-national patterns in institutional change align with standard accounts for why institutions might endure or change over time.

Our first two explanations are based on the idea that colonial institutions are more likely to persist when they are more ‘taken for granted’ and when they are more deeply embedded into the routines and practices of host governments. Duration of colonisation is the first variable that influences the embeddedness of institutions. One day after a new institution is proposed, it is unlikely to have much staying power. This is because it takes time for new institutions to become habitual. After a country has experienced 100 years of an institution, habits have been formed and the institution is more likely to be taken for granted. Given this relationship between time and persistence, countries that were colonised for longer periods should retain more colonial legislation than countries that had shorter periods of colonisation.

The second driver of embeddedness is colonial effort. Colonisers did not expend the same amount of effort reshaping societies across all their colonies. Instead, effort was likely a function of both the desire of the colonial power to exert control in the colony and the resource constraints that the colonial power faced in the colony. We consider the desire to control a colony to increase if the colony has a historical connection to the metropole, if the colony is thought to convey special prestige, and if the colony offers larger potential economic gains. These factors explain why the British cared deeply about holding India while the French invested in their longstanding settlements in Senegal. The desire to invest in a colony was tempered by resource constraints, as the colonial powers had little interest in financially supporting their colonies. In France, this was put formally into law with the 1900 law of financial autonomy for the colonies. This meant, roughly speaking, that colonies that were richer received more investments and could afford a larger administration than colonies that were poorer. Both arguments suggest that more historically important, richer colonies such as Senegal or Côte d'Ivoire should have retained more colonial legislation than colonies that were poorer, such as Upper Volta (Burkina Faso).

Third, it is expected that countries with more layers of institutions, and especially countries with more clashing institutions, will be less receptive to new institutional transplants. The logic is that as layers of new institutions are sequentially introduced to a country, it becomes more difficult for each layer to establish itself as normal or taken-for-granted. Failure to achieve this habitual status means that the institution has a relatively shallow hold on both the minds of people and the routines of bureaucracies. In the case of French West Africa, this logic would suggest that Togo should be quickest to abandon French colonial legislation as the colony was first colonised by the Germans before being divided into the British parts of Togo (now part of Ghana) and French Togoland (present-day Togo). This layering of European institutions should lead to shallower embeddedness when compared to countries that only experienced French colonisation, and so it is expected that Togo will have legislation that is more distant from colonial legislation than the other French colonies in the region.

The final explanation is a factor that may enable discontinuous change rather than reinforce institutional embeddedness. In general, it is expected that colonies that had more contentious breaks with their coloniser will be more likely to experience institutional changes while colonies that maintained close ties with their coloniser will experience fewer changes away from colonial institutions. Most of France's West African colonies gained independence peacefully and remained closely tied to France after formal decolonisation. For these countries, independence was less likely to present a critical juncture that allowed for vast reshaping of their institutions. The notable exception to this story is Guinea, which voted for immediate independence rather than joining a future French Community. The infamous French response to this vote involved the withdrawal of all French aid and French officials. Departing officials took all government property with them, including the light bulbs in their offices (Meredith Reference Meredith2011: 58–74). This harsh diplomatic break may have created a critical juncture, as it could have created the space to redefine Guinean institutions in a way that distanced them from the colonial past. Thus, we expect Guinea to have institutions that are more distant than the remaining AOF countries.

CASE SELECTION AND DATA

To test the question of whether different countries have had different levels of institutional durability, we aimed to select countries that shared an identical formal institution at independence, gained independence at about the same time, were broadly similar on background factors such as geography, and had variation on key independent variables like the duration of colonisation. These conditions are satisfied by an analysis of the penal code in the sub-Saharan portion of French West Africa (Afrique occidentale française, AOF). The countries in the sub-Saharan portion of the AOF are Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Guinea, Niger, Mali and Senegal. From this we dropped Benin because we were unable to find a post-independence penal code.Footnote 6 We then added Togo to the sample. Togo was a French mandate that was acquired from Germany after World War I and then administered as part of the AOF. Adding Togo provides additional variation on key independent variables such as duration under French colonisation or the extent to which the colony had clashing institutions.

Furthermore, the penal code is particularly useful for testing our question. Starting in 1904,Footnote 7 the French implemented a harsh penal code called the Indigénat as a tool of subjugation over their African subjects (Mann Reference Mann2009). While referred to as a Code, its handful of articles were not codified in any kind of modern understanding of the word. Instead, it was a set of rules that gave largely unrestricted power to ensure subjugation of those outside the metropole through the premise of legal order (Merle Reference Merle2004). In 1946, the Indigénat was repealed, and the penal code used in metropolitan France was extended to cover the AOF. All of the countries in the AOF gained their independence with this identical, French penal code. This created a unique historical experiment, and we leverage this episode to examine if formal institutions decay unevenly across countries.

We located the most recent available version of the penal code from each country and, using methods described below, measured the distance from each article in each current penal code back to the articles of the 1955 version of the colonial penal code. This gives us a precise measure of how much each country's penal code retains the language of the colonial code that all of the countries in the sample inherited at independence.Footnote 8

We then compiled information on a number of independent variables that allow us to carry out preliminary tests of the explanations noted above. The first explanation hinged on the duration of each country's colonial experience. We expected that countries that had longer periods of colonisation would have present codes that are closer to colonial codes. To test this, we use data on dates of military conquests from Huillery (Reference Huillery2009, Reference Huillery2011, Reference Huillery2014). Our measure of time under colonisation is the difference between the date of first military conquest and independence.Footnote 9

Our second explanation for variation in the degree to which present legislation retains colonial language was related to the importance that France attached to each colony. We expect that the French should have worked harder to instil their institutions in places that were more important to them. They should also have been able to spend more implanting institutions in colonies that were richer, and so could support a larger administration. We measure the wealth of the colony using exports and we use the number of French citizens in each colony per 1000 Africans as a measure of both wealth and the importance of the colony from France.Footnote 10 Our third and fourth explanations single out individual countries. We expect that Togo will have moved away from the colonial code because it had many clashing colonial institutions and that Guinea will have done the same because of its contentious break with France.

MEASURING TEXTUAL DISTANCE

Political scientists have recently taken an interest in computational text analysis, but most of this work is focused on either classification or scaling (Grimmer & Stewart Reference Grimmer and Stewart2013; Lucas et al. Reference Lucas, Nielsen, Roberts, Stewart, Storer and Tingley2015). For example, the first branching point in a taxonomy of text as data methods introduced by Grimmer & Stewart (Reference Grimmer and Stewart2013: 268) divides research objectives into either classification or ideological scaling. Classification groups texts into categories. For example, Stewart & Zhukov (Reference Stewart and Zhukov2009) examine whether Russia's political and military leaders share defence priorities, and in order to answer this question they group thousands of public statements from Russia's political and military leaders into categories. Scaling uses textual information to place actors within some policy space. For example, Laver et al. (Reference Laver, Benoit and Garry2003) use official party documents to measure the policy position of parties in Britain, Ireland and Germany. Slapin & Proksch (Reference Slapin and Proksch2008) present a model for measuring the ideological positions of parties over time and use it to show the position of German political parties from 1990 to 2005.

While classification and scaling are important, neither method is appropriate for answering our research question. Rather than placing texts into categories or using texts to place actors on a left–right scale, answering our research question requires us to create comparable measures of similarity from one set of texts to a single reference text. One way to measure the similarity between texts is to use plagiarism software. For example, Hinkle (Reference Hinkle2015) used this approach to measure the extent to which one law borrows language from another law. Our approach to this problem draws on string matching techniques common in the information retrieval domain of computer science.Footnote 11 In its most basic form, these approaches require dividing texts into vectors of word or character-counts and then measuring the distance between the vectors. Similar techniques are now appearing in political science (e.g. Wilkerson et al. Reference Wilkerson, Smith and Stramp2015) and legal research (e.g. Berinzon & Briggs Reference Berinzon and Briggs2016), but they are generally not grouped into a coherent categorisation. Our article thus adds a new branch to the taxonomy of text-based methods presented in Grimmer & Stewart (Reference Grimmer and Stewart2013), and we call this branch ‘distance’. Classification places texts within groups, scaling uses text to place actors within a space, and distance measures the degree of difference between texts.

We expect that distance measures will be most useful when one is asking questions about textual changes over time or space. For example, if one wanted to examine the degree to which the text of a bill changes as it moves through committees then one could calculate the distance from the evolving text at various points in time back to the original document. One could also use distance methods to measure the degree to which regulations diffuse across countries. The remainder of this section presents our specific approach to calculating distance scores for penal codes in French West Africa.

Our fundamental texts are penal codes. The smallest unit of each penal code, and our fundamental unit of analysis, is the article. Articles can contain information about what constitutes a crime, information about punishment, or more general information about the code. Each country's code contains hundreds of articles. Working at the article level allows us to make more nuanced comparisons from the current penal codes back to the colonial code. For example, a current code where half of the articles are exact copies of colonial articles and half are completely unique would receive the same code-level score as one where all of the articles in the current code borrow half of their characters from the colonial code. However, these two cases would be easily distinguished in an article-level analysis.

To construct our distance measure, we first prepare the text for analysis by removing all punctuation, making all text lowercase, standardising numbers and removing all instances of multiple spaces from the text.Footnote 12 We then compare each article in each French West African penal code to all articles in the AOF code and record the minimum distance. This procedure gives us the distance from each article in each current West African penal code to its closest match in the colonial code. Distances between articles were calculated using cosine distance.Footnote 13

In order to calculate the cosine distance between two articles, we first divide each article into n-character sections of the article known as ‘grams’. For example, the phrase ‘foo bar’ can be divided into the following 4-grams: ‘foo ’, ‘oo b’, ‘o ba’, ‘ bar’. For our analysis, and following Berinzon & Briggs (Reference Berinzon and Briggs2016), these 4-grams are calculated for all articles.Footnote 14 Articles are then compared to each other by calculating the complement of the cosine of the angle created by two vectors formed from the 4-gram counts of each respective article. We compare each article from the present code in each former colony to each article in the entire AOF code and then record the smallest distance for each contemporary article. This gives us a measure that conveys how close the language of the articles of the present code is to the language of the colonial code.

For clarity, we provide a brief example using the trivial case of calculating the 1-gram cosine distance between sentences with only two possible characters: ‘a’ and ‘b’. The first sentence (s1) reads ‘aab’ and the second (s2) reads ‘aabb’. Figure 1 shows a graph of the count of 1-grams per sentence. The graph reveals that the angle between the two vectors will always be in the range between 0 and 90 degrees, as the number of instances of ‘a’ and ‘b’ will never be negative, and so the cosine of θ will range from 0 to 1. We take the complement of the cosine so that 1 implies that the two vectors share no n-grams and 0 implies complete similarity. The intuition is the same for higher dimensional vectors.Footnote 15 In the higher dimensional case, we count number of times each n-gram occurs in each sentence and records these counts as vectors x and y, respectively. The cosine distance between the sentences is then calculated as:

Figure 1. An example of cosine distance.

This approach has a few attributes that make it noteworthy. First, it is sensitive to the order of characters within each n-gram but it is not sensitive to the order of the n-grams across the entire string. This has two effects. First, if a sentence is inverted (if inverted, a sentence is) and compared against itself it will generally have a small cosine distance because most n-gram will be similar across the two sentences.Footnote 16 Second, because n-grams can span multiple words, the order of contiguous words will have some influence on cosine distance, making the n-gram approach somewhat sensitive to word order, unlike a ‘bag of words’ approach that focuses solely on counts of words. Another noteworthy attribute of cosine distance is that it is not influenced by the length of each article. Instead, it is influenced by the relative frequency of n-grams. This implies that if we are working with 1-grams, then sentences such as ‘ba’ or ‘aaabbb’ will both have a cosine distance of zero when compared against s2 in Figure 1.

An example can clarify how cosine distance relates to the actual text of articles within the penal codes. Table I shows two examples of articles from the current Senegalese penal code that were matched to AOF articles at two small but distinct cosine distances. The table shows the actual data that were used to measure the distance between articles, so there is no punctuation and there are no upper-case letters. The differences between the current Senegalese articles and their closest matching AOF articles appear in bold. The first Senegalese article prevents ex post facto laws and regulations. The AOF version differs in three ways. First, it changes the order of the initial words (offence, crime, violation). Given that we measure the cosine distance between two vectors of 4-character sections of the text, this reversal of word order has only a small effect on the cosine distance between the two articles. The next difference is the use of ‘prévues’ (foreseen) instead of ‘prononcées’ (declared). This change in wording introduces only a small difference in meaning.Footnote 17 The third difference is that the Senegalese article allows for the offences to be provided in a law or an administrative action, whereas the AOF article restricts punishments to only those provided in law.Footnote 18 While these two articles are not identical, the differences between them are minor and accordingly the articles have a low cosine distance of 0.12.

Table I The relationship between language and cosine distance.

The next article addresses the crime of using counterfeit currency. There are two differences, one grammatical and one substantive. The substantive difference is that in Senegal both usage and attempted usage are criminalised while in the AOF only usage is criminalised. The grammatical difference is that the Senegalese code has plural language as it refers to being subject to the same ‘punishments’ as opposed to the AOF code, which refers to the same ‘punishment’. While these articles are a small sample of the thousands of articles that were studied, they provide a sense of how the cosine distance scores map to real articles within the codes. In general, we consider pairs of articles with cosine distances under about 0.2 to be close matches.Footnote 19

By calculating the cosine distance between current and colonial legislation, we are able to produce precise, transparent measures of the distance between each article in each African state's current penal code and that article's closest match in the colonial code. Examining legislation in this way allows us to measure the extent to which formal institutions are copies, or perhaps echoes, of colonial-era laws. In the following section, we use this approach to measure the degree to which West African countries have retained colonial legislation. We then examine the factors that help explain why countries have retained or abandoned colonial legislation.

MAIN RESULTS

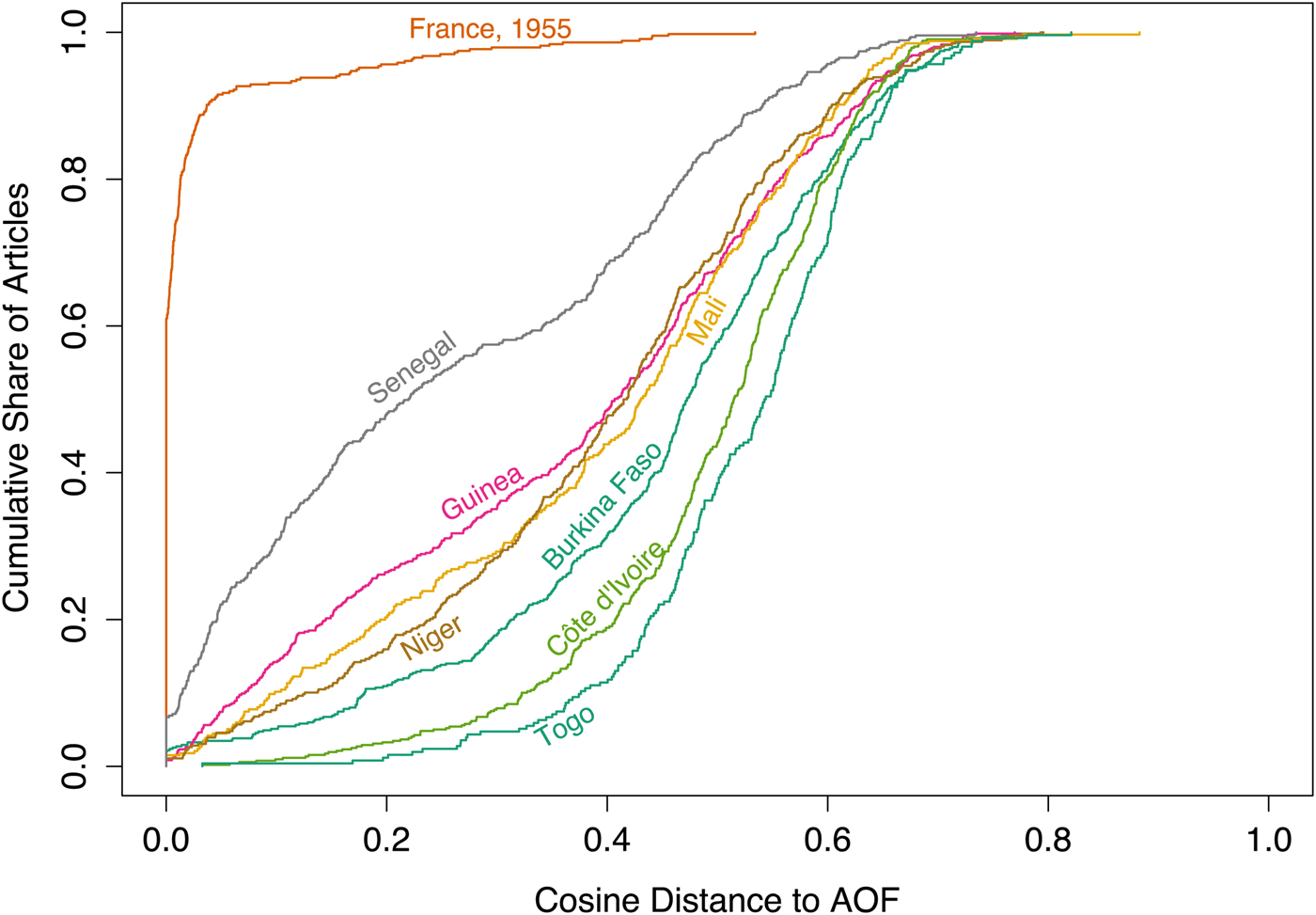

We now turn to the result of the analysis. Figure 2 shows the cumulative distribution of the cosine distances from each article in each contemporary code to the articles of the colonial code. It also includes the distribution of distances between the articles of France's penal code of 1955 and the AOF code. Each line shows how the entirety of the current penal code from each country relates back to the AOF code.

Figure 2. The empirical cumulative distribution of cosine distances in each country's penal code.

The figure first shows that, as expected, the French penal code from 1955 is almost an exact copy of the AOF code from the same year. One difference between the two involves the finer points of the death penalty. For example, Article 12 in the French code of 1955 allows only the guillotine for executions while the AOF code allows rifles if a guillotine is not available. Also, article 26 of the French code of 1955 permits more public officials as execution observers than the similar AOF article. The differences between the codes are quite minor. On the eve of independence, the colonies had exactly the same penal code and it was almost an exact copy of the code operating in the metropole.

While the colonies had the same penal code at independence, Figure 2 shows that there is now considerable variation in the extent to which current penal codes use the same language as the colonial code. To confirm this visual result, we performed two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests for each contiguous pair of African countries in the figure. A rejection of the null implies that the cumulative distributions of cosine distances from a pair of countries are statistically significantly different. The null can be rejected (p < 0.01) for all contiguous pairs of countries in Figure 2 except for Guinea and Mali (p = 0.25) and Mali and Niger (p = 0.29). Senegal has retained the most colonial-era legislation. Almost half of all current Senegalese articles are close matches (cosine distance < 0.2) to the AOF penal code and 7% of Senegal's articles are identical to articles in the AOF. Togo's current penal code is the most distant from the AOF. Only 1% of articles in Togo's code are close matches (cosine distance < 0.2) to the AOF. The remainder of the current West African codes fall within these two extremes.

There is no section of the original AOF Penal Code that all countries have uniformly changed or retained. For example, while Senegal is much closer to the AOF code than Burkina Faso and Niger, all three of them are unique in having maintained almost exact copies of the articles on poisoning (AOF article 301) and proxenetism (AOF Article 334). Togo has retained very little of the AOF code, but the AOF article defining theft has persisted (AOF article 379). A version of this article that is quite close to the AOF version has in fact persisted in most countries, with the exception of Guinea. In sum, there seem to be no cross-country patterns in which sections of the colonial penal code were retained or changed.

EXPLORATORY ANALYSES

The main goal of this article was to measure institutional change in seven West African countries. Our analysis reveals substantial colonial-institutional decay and substantial cross-national variation in this decay. Before concluding, however, we would like to also present two preliminary, exploratory analyses. The first examines legal change over time in the case of Senegal. The second examines the factors that may explain variation in the degree to which current penal codes echo the language of colonial laws.

First, we present a full record of changes to Senegal's penal code over time in Figure 3. This is possible because Senegal has not enacted a new penal code, and therefore the current version records dates of past additions or abrogations. Senegal's penal code underwent two periods of fairly large legal change, first in the mid-1970s (with law n. 77-33 of 22 February 1977) and then again in the late 1990s and early 2000s (with laws n. 99-05 of 29 January 1999 and n. 2000-38 of 29 December 2000). The modifications in 1977 address topics such as disenfranchisement of certain individuals (Article 34), the criminalisation of things that lead to the demoralisation of the army or the nation (Art. 57(4), 70), criminalisation of impersonating an officer (227), and offences against foreign dignitaries (Art. 266). The modifications in 1999 included an increase in penalties when assault is enacted on a woman or a particularly vulnerable person (Art. 294), criminalisation of physical assaults against a spouse (Art. 297 bis), criminalisation of the modification of sexual organs (Art. 299 bis) and harassment (Art. 319 bis). Generalising somewhat, it seems that the 1977 reforms made changes related to state security and the 1999 changes focused on women's rights. However, there was never an attempt to enact widespread change across the entirety of the code. Instead, there were only modest adaptations related to concerns of the day (Government of Senegal, n.d.). Senegal has retained the most AOF legislation, so one can read Figure 3 as showing the shape of moderate institutional change.

Figure 3. Changes to Senegal's penal code over time.

The next exploratory analysis examines the factors that may explain cross-country differences in the degree to which countries retained post-colonial legislation. Table II shows the mean cosine distance for each country in the sample, along with a number of explanatory variables that guide the remaining analysis.

Table II Explaining variation in legal post-coloniality.

The most evident result from Table II is the extent of Senegalese exceptionalism. Senegal had a longer duration of colonisation than any other country in our sample and its colonial experience was qualitatively different from that of the other colonies.Footnote 20 Senegal had far more French citizens in the country relative to Africans and its exports were many times more valuable than any other French colony until World War II when Côte d'Ivoire experienced an export boom. From a theory-testing point of view, this overlap is unfortunate. If colonial institutions are more durable in places that were colonised longer, had more valuable exports or had more French citizens per capita, then Senegal should retain more colonial law than other colonies. Essentially all of our explanations predict that the Senegalese code will be the closest to the colonial code, and this is in fact the case.

As with Senegalese exceptionalism, there is also a case to be made for Togolese exceptionalism. Togo was originally colonised by Germany and only became French after World War I. Thus, Togo had multiple layers of conflicting European institutions, which should weaken the influence of any given layer. Togo also came under French control quite late relative to other colonies, though once it was under French control it was a valuable colony in terms of exports. Both clashing European institutions and a short time under colonisation would predict that Togo would be likely to abandon colonial law, which it did. Unfortunately, given the present country-level data and our small number of observations, we cannot parse out the unique effect of either duration of colonisation or clashing institutions in Togo.

More interestingly, we find very little support for the argument that Guinea's uniquely negative decolonisation experience led to a sharp break in the colonial nature of its institutions. In fact, Guinea's current code is second only to Senegal in terms of the degree to which it has retained colonial language.

We also find little support for arguments that explain the retention of colonial laws as a function of exports or French citizens per capita in the colonies. While these variables successfully isolate Senegal from the remaining countries, they do not do a good job of explaining the retention of colonial legislation across the remaining countries. This is most easily seen in Côte d'Ivoire, which was easily the second most important French colony according to these criteria but has shifted its laws considerably since gaining independence. This suggests that colonial effort or the wealth of the colonies does not offer a good explanation for patterns in institutional change, though again, these are tentative statements given our small sample and given the fact that time under colonisation was not randomly assigned to countries but could easily relate to our other variables.

Time under colonisation offers the best overall explanation for the extent to which countries changed or retained colonial institutions. Figure 4 shows the relationship between a country's time under colonial ruleFootnote 21 and its mean cosine distance. Years under colonisation explains about two-thirds of the variation in mean cosine distances across countries.Footnote 22

Figure 4. Time under colonisation and changes in colonial law.

CONCLUSION

We measured the degree of similarity between the text of contemporary penal code of seven French West African countries and the colonial code that all countries inherited at independence. This approach allows us to directly measure the extent to which one formal institution in the present-day is post-colonial. Contrary to much work on the durability of colonial institutions, we find that most present-day codes have retained rather little colonial language.

Furthermore, we find that there is not a ‘French effect’ that is uniform across countries. Instead, countries vary in the degree to which their current laws reflect colonial law, suggesting a lack of homogenous ‘post-coloniality’ across countries. We presented preliminary tests for explanations of these cross-national differences. While our case selection strategy allows us to make strong claims about the unevenness of institutional persistence, our claims about the likely causes of institutional persistence are much more tentative and are limited by the small number of cases under study. Nevertheless, the results can still inform opinions about the drivers of the cross-national changes in legislation.

We found that explanations around Senegalese and Togolese exceptionalism do well, as Senegal's penal code was closest to the AOF code and Togo's was farthest. More generally, time under colonisation tracks well with changes in the penal code. We find little evidence supporting the idea that Guinea's unique break with France at independence caused it to adopt new institutions with fewer markers of its French past. Rather, Guinea's code was second closest to the AOF after Senegal's. Finally, we find little overall support for the idea that the French were better at implanting their institutions in places that were more valuable (in terms of exports) to France or in places that had more French people per capita. The lack of support for this last explanation is surprising, as post-independence ties to France have been shown to have influenced the wording of constitutions in French West Africa (Elgie Reference Elgie2012).

Aside from the relevance of this study to students of African politics and those interested in the post-colonial state, the results also show that one cannot safely assume that historical institutions typically endure or that historical institutions will decay evenly across countries over time. This finding will likely be of interest to both institutional economists and political scientists working on questions of the durability of historical institutions. Rather than even persistence over time, we found very wide divergence in the degree to which current legislation retains colonial language.

Our results also may inform international legal reform activities in West Africa, as many of these activities assume that African legislation is outdated and so requires updating. This view of African legislation as outdated is common in the legal literature. For example, Van Hoecke & Warrington (Reference Van Hoecke and Warrington1998: 499) write that ‘most African countries, after decolonisation, have, to a large extent, kept the European law imported by their colonial rulers’. Similarly, Mancuso (Reference Mancuso2008: 39–40) writes of the ‘the overall antiquity of the laws in force in almost all sub-Saharan countries’ and ‘the inadequacy of such texts with respect to the needs of the modem economy’. In showing that the colonial code has largely been abandoned, we both correct this error in the legal literature and call into question efforts aimed at updating stagnant African legislation.

Finally, the identity of a country's former coloniser has been used to explain cross-national differences in present political and economic outcomes, and the mechanism linking colonisers to present outcomes is the durability of colonial institutions. We show that within a sample of countries with the same coloniser, there is a great deal of heterogeneity in institutional decay. This suggests that institutional difference based on coloniser is, at minimum, an insufficient explanation for present development outcomes. Moreover, this provides an optimistic view of the endurance of colonial institutions. Formal institutions are not always so durable. Post-colonial labels that were apt in the early independence period may be ill-fitting today.