Introduction

Climate change has been referred to as a ‘wicked problem par excellence’ because it constitutes a series of linked problems that cannot be solved (or even diagnosed) in isolation (Termeer, Dewulf, & Breeman, Reference Termeer, Dewulf, Breeman, Knieling and Filho2013: 28)Footnote 1. These interdependencies are evident in the UN's 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)Footnote 2. Urgent action to combat climate change and its impact (Goal 13) is contingent on other SDGs being met, such as economies transitioning toward clean energy (Goal 7), production and consumption becoming more ‘green’ (Goal 12), and economic growth enabling public and private investment in innovations that support ecologically sustainable development (Goals 8 and 9). Delayed or ineffective action in mitigating and adapting to climate change is predicted to have severe and irreversible consequences for natural and human systems globally, such as flora and fauna under water (Goal 14) and on land (Goal 15), as well as food and water supplies (Goals 2 and 6). As the UN Secretary General noted in a recent review of progress on SDGs, a failure to address climate change ‘will directly threaten the attainment of all other Sustainable Development Goals’ (United Nations, 2019a: 6).

The assessment of a changing climate's impact and the formulation of adaptation and mitigation strategies involve a high degree of complexity as well as uncertainty, and require joint efforts by diverse actors with diverging interests and understandings (Head, Reference Head2008). Interdisciplinary research, defined broadly as research activities crossing disciplinary boundaries, can help inform and support these efforts by enhancing problem-definition capacity and the potential for coherent action (Brown, Harris, & Russell, Reference Brown, Harris and Russell2010; Gibbons, Limoges, Nowotny, Schwartzman, Scott, & Trow, Reference Gibbons, Limoges, Nowotny, Schwartzman, Scott and Trow1994; Nowotny, Scott, & Gibbons, Reference Nowotny, Scott and Gibbons2001). By carefully integrating, synthesizing, and reconciling multiple disciplinary problem diagnoses and conceptualizations, interdisciplinary scholarship can support the dialog between stakeholders and develop a shared understanding of the problem, and potential solutions (Conklin, Reference Conklin2006). Interdisciplinary research can also assist practitioners in conducting more robust and comprehensive assessments of the likely efficacy and efficiency of alternative pathways (Head, Reference Head2019).

Research in management and business (hereinafter ‘management’) has the capacity to contribute to interdisciplinary research efforts to support climate action, particularly to advance understanding of the socio-economic impact of climate change and of climate change responses. Management scholars have the potential to guide the formulation and implementation of response strategies by harnessing their insights into the management of organizational change and stakeholder relationships, sustainable business practices, control systems, and consumer behavior, among other issues (Beske & Seuring, Reference Beske and Seuring2014; Griskevicius, Cantú, & Van Vugt, Reference Griskevicius, Cantú and Van Vugt2012; Härtel & Pearman, Reference Härtel and Pearman2010; Maas, Schaltegger, & Crutzen, Reference Maas, Schaltegger and Crutzen2016; Winn, Kirchgeorg, Griffi, Linnenluecke, & Günther, Reference Winn, Kirchgeorg, Griffi, Linnenluecke and Günther2011; Wright & Nyberg, Reference Wright and Nyberg2017).

Despite the obvious capacity to contribute, management scholarship confronts formidable barriers to interdisciplinary impact. More broadly, integrating social science scholarship into climate change research and policy-making has frequently proven challenging. Victor (Reference Victor2015), for example, notes that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) ‘has engaged only a narrow slice of social sciences disciplines,’ namely economics. He further criticizes the panel's tendency to report ‘stylized, replicable models’ rather than discuss controversial issues and findings that seek to reflect messy social behavior. Similar concerns about the limited consideration of the full breadth of the social sciences in published climate change research have been articulated repeatedly (Billi, Blanco, & Urquiza, 2019; Castree et al., Reference Castree, Adams, Barry, Brockington, Büscher, Corbera and Newell2014; Yearley, Reference Yearley2009).

In this paper, we examine the extent to which management research has been able to contribute its unique perspective to interdisciplinary climate change research over the last four decades. Our study is guided by two research questions. First, building on work by Goodall (Reference Goodall2008) and Reference Nyberg and WrightNyberg and Wright (forthcoming), we examine how management scholarship engages with climate change – the phenomenon per se and the phenomenon as investigated in other disciplines. Second, we assess what impact management scholarship has on climate change research appearing in the top-level interdisciplinary journals Science and Nature. Given that both these journals are highly interdisciplinary in their backward referencesFootnote 3, our investigation represents a conservative test: failure to be included in the knowledge base of two of the most avowedly interdisciplinary journals constitutes a failure in interdisciplinary impact.

For our analyses, we curated two bibliometric data sets of research papers from the management disciplines and from the journals Nature and Science published between 1980 and 2018, as well as the items referenced by and citing these papers. We find that management scholarship engages significantly with top-tier climate change research but trails other social science disciplines in influencing such research. We conclude by discussing the implications for the management disciplines' capacity to help address the wicked problem of climate change.

Conceptual Foundation

The concept of interdisciplinarity is central to our analyses of management research on climate change. The concept allows us to systematically assess the depth as well as the breadth of knowledge scholars draw from prior research, and to examine the reach of their insights and findings once published. Below we elaborate the concept of interdisciplinarity and its operationalization.

Interdisciplinarity and its derivatives

Despite the widespread resonance of interdisciplinarity, its meaning and its implications are contested. Frequently, interdisciplinarity is used as a convenient umbrella concept (Hirsch & Levin, Reference Hirsch and Levin1999) to describe a variety of different activities, components, and degrees of disciplinary integration. Further, a variety of terms are currently in use to describe similar phenomena. Aside from interdisciplinarity, authors also employ multidisciplinarity, crossdisciplinarity, and transdisciplinarity to characterize research endeavors involving ‘multiple disciplines to varying degrees on the same continuum’ (Choi & Pak, Reference Choi and Pak2006: 359). These terms are often poorly and arbitrarily differentiated in the literature, and are sometimes used interchangeably, resembling an enduring ‘terminological quagmire’ (Leathard, Reference Leathard1994: 6).

We adopt a broad conceptualization of interdisciplinarity as research activities transgressing disciplinary boundaries (Bjurström & Polk, Reference Bjurström and Polk2011; Strathern, Reference Strathern2004). We follow convention by distinguishing narrow interdisciplinarity, connecting disciplines with similar epistemologies (e.g., physics and geology) from broad interdisciplinarity, connecting disciplines with dissimilar epistemologies (e.g., physics and sociology) (Bjurström & Polk, Reference Bjurström and Polk2011). Connecting the natural and social sciences is the most distinct example of broad interdisciplinarity (Bjurström & Polk, Reference Bjurström and Polk2011).

A particularly interesting debate within the research on interdisciplinarity concerns its evolution over time. Many scholars contend that research needs to become ever more interdisciplinary in response to increasingly complex challenges (Forman & Markus, Reference Forman and Markus2005; Metzger & Zare, Reference Metzger and Zare1999). Some even posit that contemporary science has moved into a postdisciplinary stage, steadily eroding the disciplinary bases of research (Gibbons et al., Reference Gibbons, Limoges, Nowotny, Schwartzman, Scott and Trow1994; Nowotny et al., Reference Nowotny, Scott and Gibbons2001). Others contend the opposite, arguing for a distinct life-cycle dynamic: interdisciplinarity may only be required for the earliest research into a new phenomenon before giving way to more discipline-based scholarship (Leydesdorff & Goldstone, Reference Leydesdorff and Goldstone2014; Olsen, Borlaug, Klitkou, Lyall, & Yearley, Reference Olsen, Borlaug, Klitkou, Lyall and Yearley2013).

Bibliometric studies present mixed findings regarding temporal trends in interdisciplinarity. Van Noorden's (Reference Van Noorden2015) study of articles from all disciplines contained in the Web of Science (WoS) database reveals that the proportion of citations from outside the home discipline was identical in 1950 and 2010 for articles originating from the natural sciences and engineering (following a decades-long slump), and increased somewhat over the same period for articles originating from the social sciences. That picture corresponds with earlier analyses by Van Leeuwen and Tijssen (Reference Van Leeuwen and Tijssen2000), comparing boundary-crossing co-citations for multiple disciplines and finding little evidence for a change between 1985 and 1995. By contrast, Porter and Rafols (Reference Porter and Rafols2009), mapping six broad research domains between 1975 and 2005, document an increase in interdisciplinarity by 50%, albeit overwhelmingly on account of narrow interdisciplinarity, i.e., research across closely related disciplines. These nuances and apparent inconsistencies across a small number of representative studies hint at the contentiousness of the interdisciplinarity concept, its operationalization and ultimate effects (e.g., Bjurström & Polk, Reference Bjurström and Polk2011; Leydesdorff & Rafols, Reference Leydesdorff and Rafols2011).

Interdisciplinarity in climate research

The origins of climate change research can be traced back to early investigations in geophysics and meteorology. Separately and, beginning in the 1950s, jointly, these disciplines formed the foundations for modern-day climate science. The emergence of the overarching earth sciences in the 1970s and 1980s, and the creation of the IPCC framework in 1989, paved the way for other disciplines to contribute to climate change research (Weart, Reference Weart2013). This, in turn, led to the growth in interdisciplinary research centers, such as the UNSW Climate Change Research Centre, New Zealand Climate Change Research Institute, and the UK's Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research.

Despite these interdisciplinary origins, the nature and dynamics of interdisciplinarity in climate change research are hotly contested. Some suggest that ‘the disciplinary mix has continued to evolve to meet the [inter-disciplinary] challenge’ of climate change (Munasinghe, Reference Munasinghe2001: 14) and document a rise in interdisciplinarity (e.g., Hellsten & Leydesdorff, Reference Hellsten and Leydesdorff2016). Others highlight the difficulties in bridging deep epistemic divides and view integration an impossibility (e.g., Malone & Rayner, Reference Malone and Rayner2001). Taking an overarching perspective, Bjurström and Polk (Reference Bjurström and Polk2011) find that disciplinary integration within climate change research occurs primarily as narrow interdisciplinarity, defined as straddling related disciplines, and only rarely as broad interdisciplinarity, defined as transgressing the boundary between the natural and social sciences. As such, they do not support Gibbons et al.'s well-known argument that societal needs for ‘socially robust knowledge’ invariably lead to an (interdisciplinary) re-shaping of science (Gibbons et al., Reference Gibbons, Limoges, Nowotny, Schwartzman, Scott and Trow1994; Nowotny, Scott, & Gibbons, Reference Nowotny, Scott and Gibbons2001). Bjurström and Polk (Reference Bjurström and Polk2011) interpret their results as reaffirming the mostly disciplinary structure of climate change research, with a persistent divide between the natural and social sciences.

Given these findings, we examine more closely how management research has navigated the challenges of interdisciplinarity. We start by investigating management research's concern with the phenomenon of climate change per se. We then explore to what extent management scholarship on the topic has been (narrowly or broadly) interdisciplinary in engaging with climate change research conducted in other disciplines (and appearing in the journals Nature and Science). Finally, we explore the impact of management scholarship on other disciplines (as represented in climate change research appearing in the journals Nature and Science).

Methods and Data

Search strategy

To investigate management scholarship's engagement with climate change and with climate change research originating in other disciplines, we built two bibliometric data sets using Clarivate's WoS databaseFootnote 4. The first data set, labeled ‘Management Climate Change Research’ (MCCR), comprises climate change-related articles in management journals from 1980 to 2018. The second data set, labeled ‘Science and Nature Climate Change Research’ (SNCCR), comprises climate change-related articles published in the two avowedly interdisciplinary journals Science and Nature from 1980 to 2018. Both data sets contain information about the items' backward references, i.e., references to prior research, and their forward citations, i.e., references made to the items in our data sets by WoS-indexed publications.

Our search strategy employed inclusive search terms to reduce the likelihood of Type II errors in the initial identification of potentially relevant publications. Any Type I errors that may result from this inclusive approach were contained with subsequent checks and filters. To determine the search string for the initial selection of articles, we consulted prior bibliometric reviews of climate change research (Haunschild, Bornmann, & Marx, Reference Haunschild, Bornmann and Marx2016; Wang, Zhao, & Wang, Reference Wang, Zhao and Wang2018) and Clarivate's experts. Ultimately, the following string was used for the topic search (field ‘TS’) for English-language items published between 1980 and 2018 and listed in the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), and Arts and Humanities Citation Index (AHCI):

$$\eqalign{{\rm TS} = & \lpar {\lpar {^{\prime\ast} climat\ast \,chang ^{\ast} ^{^\prime}} \rpar \,or\,\lpar {^{\prime} {^\ast} climat \ast \,warming ^\ast {^\prime}} \rpar \,or\,\lpar {^{\prime } {^\ast} global\,temperature ^\ast {^\prime}} \rpar \,or\,} \cr & \lpar {^{\prime} {^\ast} global\,warming ^\ast {^\prime}} \rpar \,or\,\lpar {^{\prime} {^\ast} greenhouse\,gas {^\ast} ^{\prime}} \rpar \,or\,\cr & \lpar {^{\prime} {^\ast} greenhouse\,effect {^\ast} ^{\prime}} \rpar \,or\,\lpar {^{\prime}greenhouse\,warm {^\ast} ^{\prime}} \rpar \,or\,\lpar {^{\prime}anthropogenic\,warming ^\ast {^\prime}} \rpar \,or\,\cr & {\lpar {^{\prime}anthropogenic\,emission ^\ast {^\prime}} \rpar \,or\,\lpar {{^\prime}climat ^\ast \,model ^\ast {^\prime}} \rpar } \rpar } $$

$$\eqalign{{\rm TS} = & \lpar {\lpar {^{\prime\ast} climat\ast \,chang ^{\ast} ^{^\prime}} \rpar \,or\,\lpar {^{\prime} {^\ast} climat \ast \,warming ^\ast {^\prime}} \rpar \,or\,\lpar {^{\prime } {^\ast} global\,temperature ^\ast {^\prime}} \rpar \,or\,} \cr & \lpar {^{\prime} {^\ast} global\,warming ^\ast {^\prime}} \rpar \,or\,\lpar {^{\prime} {^\ast} greenhouse\,gas {^\ast} ^{\prime}} \rpar \,or\,\cr & \lpar {^{\prime} {^\ast} greenhouse\,effect {^\ast} ^{\prime}} \rpar \,or\,\lpar {^{\prime}greenhouse\,warm {^\ast} ^{\prime}} \rpar \,or\,\lpar {^{\prime}anthropogenic\,warming ^\ast {^\prime}} \rpar \,or\,\cr & {\lpar {^{\prime}anthropogenic\,emission ^\ast {^\prime}} \rpar \,or\,\lpar {{^\prime}climat ^\ast \,model ^\ast {^\prime}} \rpar } \rpar } $$In creating the MCCR data set, we included results from all four WoS subject categories (field ‘WC’) related to management: ‘business,’ ‘management,’ ‘business, finance’ (subsequently referred to as ‘finance’), and ‘operations & management science’ (subsequently referred to as ‘operations’). We restricted results to the document types (field ‘DT’) ‘article,’ ‘editorial material,’ ‘review,’ ‘book review,’ ‘letter,’ and ‘news item’Footnote 5. In contrast to Goodall (Reference Goodall2008) and Reference Nyberg and WrightNyberg and Wright (forthcoming), we included items from all journals within these subject categories in our database. Restricting the analysis to a small set of top journals would have risked misrepresenting editorial preferences for actual scholarly engagement within management disciplines with the topic of climate change.

The search results were verified with a random sample of 180 articles (10% of the articles contained in the data set). Specifically, two of the authors independently reviewed the sampled articles' relevance to climate change based on title and abstract. Disagreements in the evaluation of an article's relevance were resolved through discussion. The review identified seven false positives, i.e., items that were not relevant to our search topic. One of these false positives was a research article about organizational climate. Based on this finding, we were able to identify and exclude 11 other articles about ‘work climate,’ ‘safety climate,’ ‘ethical climate,’ etc. The final MCCR data set included 1,724 unique articles, with a total of 94,692 backward references and 42,012 forward citations.

In creating the SNCCR data set, we used the same topic search string, and same parameters concerning language, time frame, document type, and database specifications as for the management data set, but restricted results to the journals (source title field ‘SO’) Science and Nature. The initial search results were again verified with a random sample of 180 articles (6% of the articles contained in the data set) by two of the authors. The review identified only one false positive, an article about climate change on the planet Mars. In response, we were able to identify 23 other articles about the climate of planets other than Earth and excluded them from the data set. The final SNCCR data set included 2,981 unique Science and Nature articles, with a total of 59,295 backward references and 600,710 forward citations. These item counts are comparable to those presented in other recent bibliometric analyses of climate change journal publications (Haunschild, Bornmann, & Marx, Reference Haunschild, Bornmann and Marx2016).

Disciplinary classification

For our analyses, the disciplinary classification of articles is of central importance because interdisciplinarity implies a crossing of disciplinary boundaries. We therefore need to establish initially what constitutes a discipline and its demarcations. Disciplines are institutional custodians of specialist knowledge, but they are also in exchange with one another and at times share substantive knowledge content (Geertz, Reference Geertz1980). While disciplines evolve and, on occasion, new ones emerge (Bonaccorsi & Vargas, Reference Bonaccorsi and Vargas2010), disciplinary boundaries, on the whole, are remarkably stable (Abbott, Reference Abbott2001).

We follow prior bibliometric studies of interdisciplinarity (Leydesdorff, Rafols, & Chen, Reference Leydesdorff, Rafols and Chen2013; Solomon, Carley, & Porter, Reference Solomon, Carley and Porter2016) in utilizing WoS's subject categories (field ‘WC’) to delineate disciplinary boundaries and interdisciplinary connections. WoS assigns subject categories to articles and to journals. These categories are the foundation for within-discipline journal rankings based on Journal Impact Factors (JIFs). While a journal can be affiliated with multiple subject categories, most journals are affiliated with only one. For example, the journal Organization & Environment is associated with the two disciplines ‘environmental studies’ and ‘management.’ In 2018, it was in the top quartile (‘Q1’) for both disciplines, ranked 8th for the former and 16th for the latter. The journals Nature and Science are associated with the special category ‘multidisciplinary sciences,’ and based on their JIFs were ranked 1st and 2nd, respectively, in 2018, and hence are at the very top of the Q1 set of journals in the category. WoS also associates journals with its three main indices, SCIE, SSCI, and AHCI. 8% of journals are associated with more than one index. For example, the journal Ecology & Society is listed in both the SCIE and SSCI.

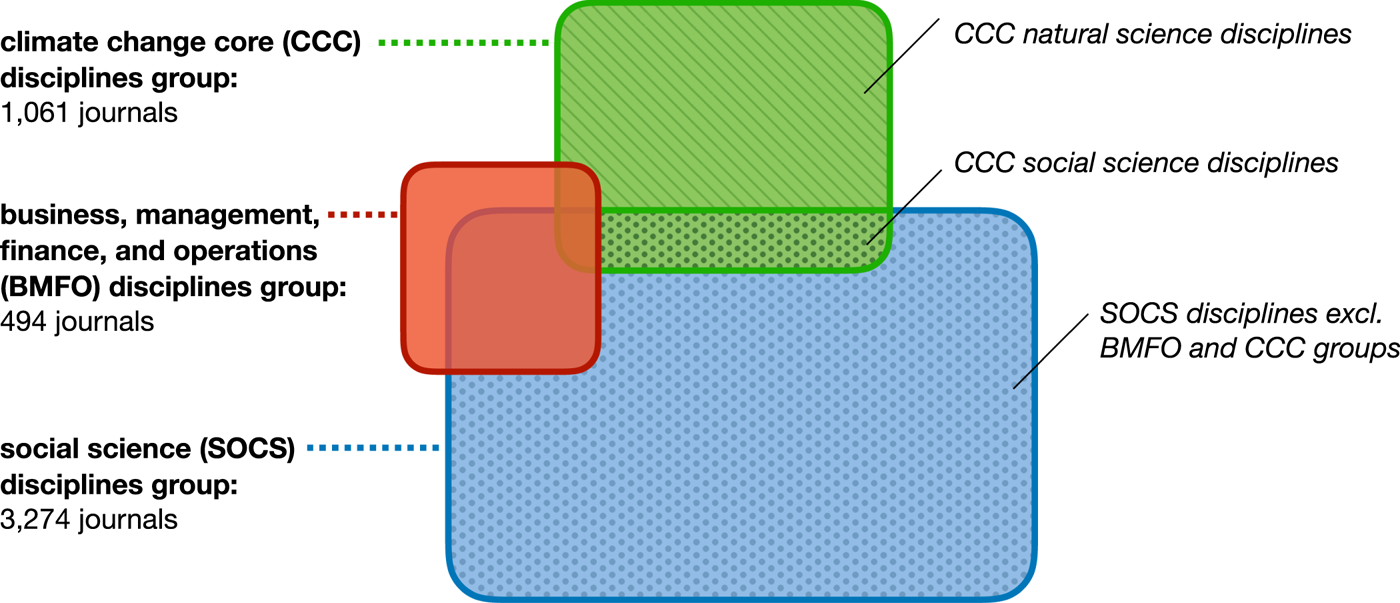

For our analyses, we make use of journals' association with subject categories and WoS indices to quantify papers' degree of narrow and broad interdisciplinarity of backward references. To this end, we created three groups to aid in delineating interdisciplinary referencing. The social science (‘SOCS’) disciplines group comprises all 3,274 journals that are listed in the Social Science Citation Index (including those journals with multiple index affiliations). The Climate Change Core (‘CCC’) disciplines group comprises all 1,061 journals that are associated with the 10 most common WoS subject categories in climate change research, specifically ‘environmental sciences,’ ‘meteorology and atmospheric sciences,’ ‘multidisciplinary geosciences,’ ‘ecology,’ ‘environmental studies,’ ‘energy and fuels,’ ‘water resources,’ ‘physical geography,’ ‘multidisciplinary sciences,’ and ‘environmental engineering.’ Of these 10, only environmental studies is associated with the SOCS. Collectively, the 10 categories account for two-thirds of all climate change research (using the search string above) across the WoS SCIE, SSCI, and AHCE databases. The third group, the ‘BMFO’ disciplines group, comprises all 494 English-language journals from the business, management, finance, and operations disciplines. Within the BMFO group, some journals are associated with more than one of the BMFO disciplines and some journal associations are incongruous with the respective journals' mission statements. Hence, we adjusted the disciplinary associations and assigned journals to a single, primary discipline (see Appendix for details). The adjustments result in a set of 66 business, 201 management, 112 finance, and 115 operations journals. Figure 1 provides an overview of how the three groups (SOCS, CCC, BMFS) overlap and intersect.

Figure 1. Overview of three groups for the analysis of interdisciplinary engagement within climate change research.

Lastly, in our analyses of narrow and broad interdisciplinarity, we distinguish, for more gradation, between references to a native discipline, and non-native disciplines. For example, an item published in Organization & Environment, a journal whose primary discipline is management, may contain references to items published in finance journals. We designate these as non-native references within the BMFO disciplines group, an indicator for narrow interdisciplinarity. For items from the SNCCR data set, we base the native/non-native designation on the item-level (not journal-level) disciplinary affiliation, since both Science and Nature are in the multidisciplinary sciences journal category. Using the item-level disciplinary designation allows for a more precise assessment of interdisciplinary referencing in these articlesFootnote 6.

Item content coding

Using two samples from the MCCR and SNCCR data sets, respectively, we undertook qualitative holistic coding (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2014) to identify research themes and the degree of engagement with climate change. Holistic coding typically involves applying a single code to an entire item, rather than line-by-line coding (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2014). Multiple researchers worked independently to categorize items; a very small number of divergent allocations were resolved through team discussion (Saldaña, Reference Saldaña2009).

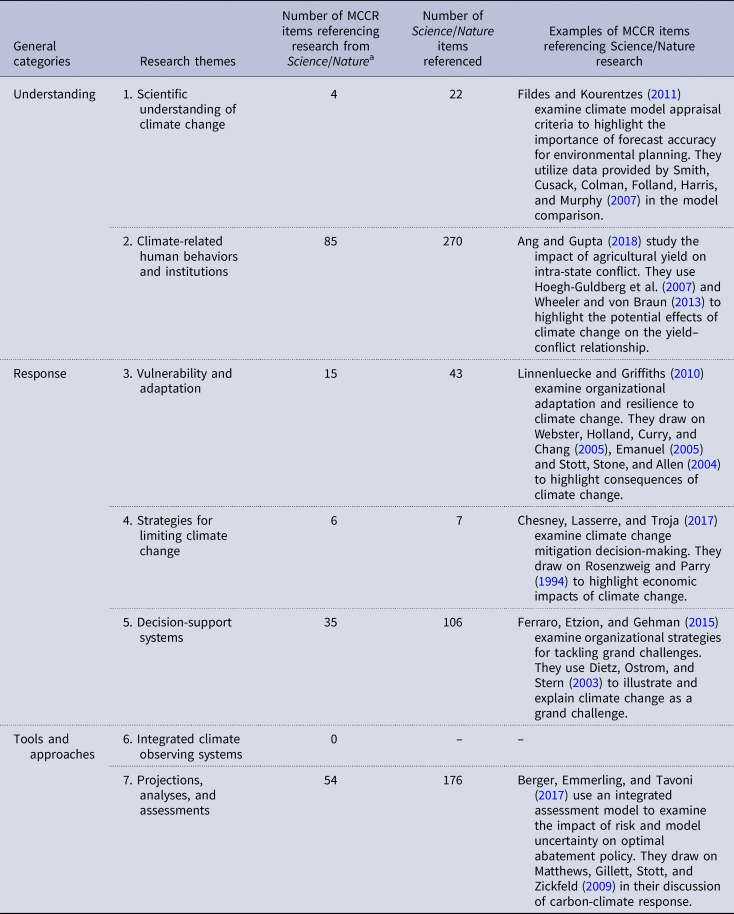

We coded the items according to seven integrative themes proposed by the Panel on Advancing the Science of Climate Change convened by the United States' National Research Council (NRC). The themes can be grouped into the three overarching categories of ‘understanding’ (research devoted to the scientific understanding of climate change and its interactions with coupled human-environment systems), ‘response’ (solution-focused research devoted to improving and supporting more effective responses to climate change), and ‘tools and approaches’ (creation of tools and approaches required for both understanding and responding to climate change) (see Table 1). The themes and overarching categories provide a systematic way to classify climate change research (NRC (National Research Council) (U.S.), 2011: 91). In our coding, and in line with the Panel's recommendations, a single research paper may address several of the research themes and thus may be assigned to multiple categories.

Table 1. Integrative climate change research themes (adapted from NRC (National Research Council) (U.S.), 2011)

The coding process revealed that items in the MCCR and SNCCR data sets vary with regards to their depth of engagement with the topic of climate change. Some items use climate change as a stepping-off point to introduce their phenomenon of interest. For example, a substantial number of disaster management-related items in the MCCR data set briefly note that global warming increases the incidence of extreme weather events, thus highlighting the importance of the research presented, before drilling down into the focal disaster management issue. In contrast, a number of studies on corporate governance investigate board of directors' responsibilities in climate change-related decision-making. They consider, in some detail, the specific challenges of, and responses to, climate change that need to be considered by decision-makers (e.g., Prado-Lorenzo & Garcia-Sanchez, Reference Prado-Lorenzo and Garcia-Sanchez2010). We discuss these differences in the degree of engagement below, distinguishing between ‘token engagement’ and ‘direct engagement.’

Results

Research output

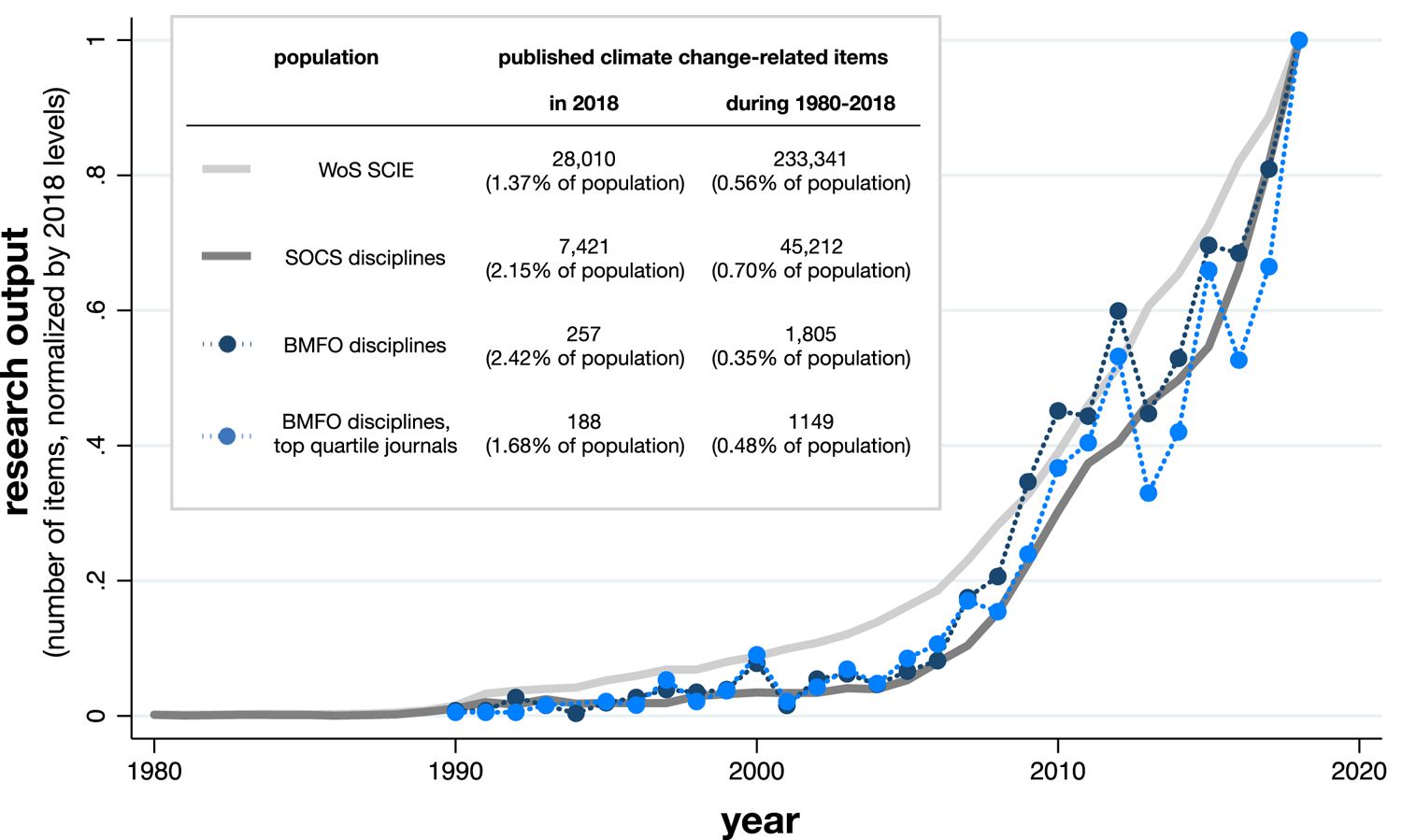

Management scholars are not oblivious to the problems facing the planet and human kind. Over the period 1980–2018, 1,725 items were published in 257 different journals. Notably, 64% of the items were published in top quartile journals. At the same time, the absolute number of management publications on the topic appears miniscule compared to the more than 200,000 published papers on climate change across all disciplines (Haunschild, Bornmann, & Marx, Reference Haunschild, Bornmann and Marx2016); or even when compared to the approximately 40,000 publications in the social sciences. However, when considering the vastly different quantities of publications across these different groupings, management scholarship's respectable engagement with climate change comes to light. Specifically, .35% of all items published in BMFO journals during the 39-year period we examined were related to climate change. This is about half the scholarly attention the topic received across all social science disciplines (.7% of published papers between 1980 and 2018). However, management scholarship on climate change grew significantly from the mid-2000s, and at a rate comparable to that of the social sciences. Figure 2 shows that climate change-related research output captured in the MCCR data set, normalized by 2018 levels, followed the growth pattern of research on the topic in the social sciences, with a marked upturn in research output beginning in the second half of the 2000s.

Figure 2. Growth of climate change research over time. WoS SCIE = Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded; SOCS = Social Sciences; BMFO = Business, Management, Finance, and Operations.

Particularly encouraging is that throughout this growth, a disproportionate number of the items in the MCCR data set appeared in the top quartile of the management disciplines' journals (see percentages of items in Q1 journals, and lists of highest impact journals, in Table 2). This provides evidence that the topic has claimed its place in mainstream management-related journals and is not limited to the disciplinary fringes. In management and operations that tendency is particularly pronounced, with the majority of climate change-related research appearing in top quartile journals.

Table 2. Overview of management research on climate change-related issues 1980–2018

We now turn to management scholars' connection with climate change research appearing in other disciplines, labeled as interdisciplinary engagement (based on backward references) or interdisciplinary impact (based on forward citations).

Interdisciplinary engagement

The quantitative assessment of the MCCR items' backward references reveals substantial narrow and broad interdisciplinarity. References to journals outside their native discipline could be found in 92% of all items in the data set. Of the 94,692 backward references, 7.3% were made to non-native disciplines within the BMFO group (e.g., a finance journal article referencing research from management journals), 10.3% to environmental studies (the sole social science discipline in the CCC group), and 10.1% to other social sciences (principally to economics). Collectively, these represent the extent of narrow interdisciplinarity, i.e., engagement with epistemologically similar disciplines.

MCCR items also include a notable amount of references to journals outside the social sciences, indicative of broad interdisciplinary engagement: 7.4% of references go to natural science journals from the CCC group, and 13.2% to other disciplines. The journals Science and Nature are well-represented in the broad interdisciplinary engagement efforts: they are among the top 5 most frequently cited journals outside the BMFO group. We also note a substantial share (34%) of nonjournal references. These prominently include books on climate as well as government and other reports (such as the IPCC's).

Figure 3 visualizes how these patterns of backward references evolved over time. The figure shows gradations of interdisciplinarity, ranging from native, within-discipline, and narrowly interdisciplinary references at the bottom to increasingly broad interdisciplinary references at the top layers. After 2010, the share of references to natural and to social science journals in the CCC group stabilized at around 7% and 10% of yearly references, respectively. The percentage of native disciplinary references increased from 15% in 2010 to 22% in 2018, replacing primarily nonjournal references. The share of references to journals from the SOCS group peaked during the early 2000s and declined thereafter. The general pattern of substantial and sustained broad interdisciplinary engagement holds true for articles from all four BMFO group disciplines, with articles published in management journals showing the strongest engagement with the CCC group disciplines.

Figure 3. (Inter)disciplinary engagement of climate change-related management research (MCCR data set).

To investigate in more detail how management scholars integrate research from across various disciplines, we coded a sample of 121 items in the MCCR data set. Because we are particularly interested in how scholars engage top-tier multidisciplinary climate change research, we drew our sample from the 443 MCCR items that contained at least one reference to either Science or Nature.

Table 3 shows, across the seven research themes, how many MCCR research papers reference items published in Science or Nature, and how many such items they cumulatively reference. The table also provides illustrative examples for each theme, summarizing representative MCCR items and their use of research published in Science or Nature. Seven out of the 121 MCCR items we coded only featured token references to climate change and consequently were not assigned to any of the seven research themesFootnote 7. The remaining MCCR items engaged with the topic of climate change directly and adopted one or more research themes. MCCR items spanned a range of topics related to climate change, including organizational resilience, environmental accounting, risk management, and corporate social responsibility, as well as a range of contexts, including the agricultural sector, carbon pricing, energy markets, and financial markets.

Table 3. Coding results for seven research themes based on a sample of 121 MCCR items

a MCCR items can cover multiple research themes, and hence are included in the counts of multiple themes.

Interdisciplinary research impact

We noted above that management disciplines' research on climate change does attract significant scholarly attention, as evidenced by the items' relatively high number of forward citations. Yet for that scholarship to contribute to addressing the wicked problem of climate change, it needs to be noticed and utilized outside of its disciplinary boundaries, and ultimately find an audience outside of academia.

Of the 2,981 items in the SNCCR data set, only 26 items reference research from BMFO disciplines. Of the 1,745 items in the MCCR data set, only 19 feature among the 48 unique BMFO items referenced by the SNCCR items. The low engagement of SNCCR items with research from management disciplines should be considered in a context of (1) increasing interdisciplinarity of research published in Science and Nature, and (2) persistently low overall engagement with, and integration of, social science research. From 1980 to 2018, the number of unique disciplines cited by the 2,935 SNCCR items grew, from only eight different disciplines (all from the natural sciences) in 1980 to a total of 124 different disciplines (38 of them from the social sciences) in 2018. The most frequently referenced social science disciplines are environmental studies, economics, and anthropology (see Table 4).

Table 4. Top 10 referenced social science disciplines in SNCCR data set

a Cited references can be associated with multiple social science disciplines.

Despite this broadening of the knowledge base, however, the share of references to articles from social science disciplines remained low, reaching its highest level at just under 6% of total references in the year 2016. Figure 4 visualizes the gradations of interdisciplinary referencing over time (as in Figure 3, the groups are layered from the bottom to the top with increasingly broad interdisciplinarity). The figure reveals that social science disciplines other than environmental studies (the sole social science discipline in the CCC group) are all but absent before 2010 and constitute only a small share of references after 2010. References to BMFO disciplines are so low that they are invisible in the figure.

Figure 4. (Inter)disciplinary engagement of Science and Nature climate change research (SNCCR data set).

To investigate how items in the SNCCR data set integrate management disciplines' climate change-related research, we coded all SNCCR items citing management disciplines research (total sample of 26 SNCCR items and 40 cited management papers).

Table 5 presents the seven research themes identified in the SNCCR items referencing management research as well as the number of management items referenced cumulatively by the Science/Nature items associated with each theme. Table 5 also provides an exemplar for each theme, summarizing the climate change focus of the SNCCR item and how utilized management research. Five out of 26 SNCCR items were classified as token references and were not assigned to any research themesFootnote 8. The remaining Science/Nature items engaged with the topic of climate change directly. For instance, Wheeler and von Braun (Reference Wheeler and von Braun2013) investigate the impact of climate change on global food security to highlight adaptation and mitigation strategies.

Table 5. Coding results for seven research themes based on 26 items from the journals Science and Nature

a SNCCR items can cover multiple research themes, and hence are included in the counts of multiple themes.

The management research that does get cited by the SNCCR data set represents a diverse set of articles featuring climate change, including sustainable development, applied scenario planning, and risk financing and insurance. In most cases, the Nature and Science climate change papers that draw on management scholarship only cite a single item. Overall, references to top-tier management journals are rare. Only two out of 26 SNCCR items featured direct use of the management research. For example, Steinacher, Joos, and Stocker's (Reference Steinacher, Joos and Stocker2013) study of carbon emissions utilized scenario modelling as described in Grübler et al. (Reference Grübler, Nakicenovic, Riahi, Wagner, Fischer, Keppo and Tubiello2007). In the majority of SNCCR items, the research from management disciplines provided the context or precursor to the main topic. Management disciplines' broad range of theories, such as those regarding institutions, stakeholder management, and complexity (Ansari, Gray, & Wijen, Reference Ansari, Gray and Wijen2011) have great potential relevance for the wicked problem of climate change. Yet they mostly remained underutilized by SNCCR items (see also Daddi, Todaro, De Giacomo, & Frey, Reference Daddi, Todaro, De Giacomo and Frey2018, on this point), which typically only feature a generic cite of the article's general topic or empirical finding (e.g., Sutton & Hodson, Reference Sutton and Hodson2005). A notable exception is the study of ecosystem conservation by Amel, Manning, Scott, and Koger (Reference Amel, Manning, Scott and Koger2017), in which the authors engage more fully with the concepts of organizational culture, norms, and leadership, as set out in the management research they reference.

Discussion

Climate change is a wicked problem, characterized by intertwined bio-physical and social processes. Interdisciplinary work carries the promise of addressing these interdependencies, furthering our understanding and honing our responses. Yet bringing together the natural and social science communities remains a formidable challenge in the face of ingrained epistemic, methodological, and structural boundaries that tend to divide the disciplines (Härtel & Pearman, Reference Härtel and Pearman2010; Mooney, Duraiappah, & Larigauderie, Reference Mooney, Duraiappah and Larigauderie2013; Victor, Reference Victor2015). Some suggest that ‘the social’ of climate change has been downplayed and mostly treated in a reductionist fashion (Billi, Blanco, & Urquiza, 2019; Victor, Reference Victor2015).

Recognizing the challenges of interdisciplinarity, the present paper aimed to establish ‘stylized facts’ (Helfat, Reference Helfat2007) regarding management scholars' connection with climate change – the phenomenon per se, as well as climate change research appearing in other disciplines. Our investigation uncovered the following:

• Management research, broadly defined, is increasingly concerned with the phenomenon of climate change, as evident in significant and growing numbers of articles centered on the topic.

• Climate change-related management research spans across the spectrum of research themes identified by the NRC's Panel on Advancing the Science of Climate Change.

• Management research is incorporating into its knowledge base climate change research appearing outside the discipline, in the form of substantial narrow as well as broad interdisciplinary references.

• Management research is exceedingly rarely cited by climate change research appearing in the most high-profile interdisciplinary research outlets Nature and Science.

Our findings provide a different perspective on climate change research in management than Goodall's (Reference Goodall2008) and Reference Nyberg and WrightNyberg and Wright's (forthcoming) assessments. Goodall's review of climate change research in management up to the year 2006 led her to lament that, at the time, the discipline's top journals had ‘barely published an article on the topic’ (p. 408). Similarly, Reference Nyberg and WrightNyberg and Wright (forthcoming), following their analysis of top management publications for the period 2007–2018, conclude that there is evident neglect of climate change research in the ‘management academy.’ Using a more inclusive search strategy (incorporating business, management, operations, and finance journals), we confirm limited research attention to climate change between 1980 and 2006 (130 articles, 75% of which are published in top quartile journals). But we also detect a remarkable growth in climate change-related research thereafter (2007–2018: 1,594 articles). Over the timeframe examined, specialized management journals such as Business Strategy and the Environment and Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management have significantly increased the number of articles they publish per year, and as a result have emerged as key outlets for climate change-related management research. Additionally, editorial clarion calls (e.g., Howard-Grenville, Buckle, Hoskins, & George, Reference Howard-Grenville, Buckle, Hoskins and George2014) and Special Issues (e.g., Organization Studies, 2012, Issue 11) have strengthened the topic's legitimacy within the management disciplines. In short, our findings lead us to disagree with the contention that climate change is ‘noticeably absent in academic management research’ (Nyberg & Wright, Reference Nyberg and Wrightforthcoming: 3).

While the substantial and growing volume of research on climate change within the management disciplines is reason to celebrate, the disparity between interdisciplinary engagement (backward references) and interdisciplinary impact (forward cites) is cause for concern. While management has successfully broadened its knowledge base by including sources from beyond the home discipline, it has failed to ‘export’ its own insights. It seems that exhortations for greater interdisciplinarity by august institutions and esteemed editors, generous incentives for interdisciplinary work by funding agencies, or the creation of interdisciplinary research units are insufficient to help management scholarship infiltrate other disciplines.

We briefly consider two interpretations for this disparity between management disciplines' interdisciplinary engagement and interdisciplinary impact. The first interpretation is that management scholarship goes unnoticed with climate change researchers outside the management disciplines, and in particular with those outside the social sciences. The absence of organization-level phenomena and references to firms in recent statements outlining whole-of-science approaches to climate change research hint at this possibility (cf. Kramer et al., Reference Kramer, Hartter, Boag, Jain, Stevens, Ann Nicholas and Liu2017; Reid et al., Reference Reid, Chen, Goldfarb, Hackmann, Lee, Mokhele and Whyte2010). To bridge this awareness gap requires management scholars to intensify efforts at promoting their climate change-related work. Analogous to Hambrick's (1994) call for knowledge translation in a bid to bridge the gap between management scholars and practitioners, the discipline needs to find ways to translate its insights for consumption by other scholars. For instance, generating more publications with the explicit aim of making climate-related management scholarship accessible to researchers in other disciplines may help stimulate mutual interdisciplinary engagement. To reiterate, management research on climate change spans all three overarching categories of the NRC framework – from understanding climate-related behavior, to response options and methodological contributions – and therefore has ample opportunities to pursue interdisciplinary dialog across a wide range of topic areas.

A second interpretation is that researchers from other disciplines are aware of management scholarship on climate change, but do not consider it relevant or rigorous enough to incorporate into their own studies. Victor (Reference Victor2015) – a member of the IPCC Working Group III, which is tasked with assessing mitigation and climate policy options – describes the group's tendency to ignore insights from the social sciences as they are often seen as speculative, uncertain, and supported only by weak paradigms. It is conceivable that similar reservations account for the lack of engagement with management research. If this is the case, overcoming such concerns would prove more challenging than addressing an awareness gap. It would likely require management scholars to more directly collaborate with researchers from other disciplines, particularly those from outside the social sciences. Such collaborations would be aided, for example, by the recommendations laid out by Brown, Deletic, and Wong (Reference Brown, Deletic and Wong2015). Addressing other disciplines' concerns about management scholarship's rigor and relevance may require stronger efforts within management disciplines to conduct (and publish) replication studies, and to compile large-scale, open-access data sets of organizational behavior related to climate change.

Irrespective of whether management scholarship is confronting an awareness gap or rigor/relevance concerns, new ways of connecting with other disciplines are sorely needed in the search for research impact and, more importantly, in the race to motivate climate action. As climate science shifts its emphasis to developing practical adaptation and mitigation strategies (Weaver, Mooney, & Allen, Reference Weaver, Mooney and Allen2014), scholars and policy makers have to contend with the value-laden and pluralist nature of stakeholder views and claims (Garud, Gehman, & Karunakaran, Reference Garud, Gehman and Karunakaran2014). Seemingly endless debates concerning the evidence for climate change, its precise impact, and the feasibility of alternative pathways to a low-carbon future (Brett, Reference Brett2014; Head, Reference Head2014) are signs of an underlying social and political impasse. Management scholarship offers a considerable conceptual arsenal for decoding organizational, institutional, and cultural determinants of climate change denialism and resistance to climate action, as well as techniques that facilitate consensus-building, coordination, and adaptive change among social actors. For example, organizational sense-making and sense-giving practices (Fiss & Zajac, Reference Fiss and Zajac2006; Maitlis, Reference Maitlis2005) or boundary work (Garud, Gehman, & Karunakaran, Reference Garud, Gehman and Karunakaran2014) are highly relevant for collective organization in favor of climate action. Likewise, suitable funding mechanisms for climate change adaptation and mitigation initiatives (Shardul & Carraro, Reference Shardul and Carraro2010), performance management systems that foster accountability, enable progress monitoring and corrective interventions (Atkins, Atkins, Thomson, & Maroun, Reference Atkins, Atkins, Thomson and Maroun2015), as well as quantitative models of complex organizational systems that aid planning and decision-making under uncertainty (Filar & Haurie, Reference Filar and Haurie2010; Huang, Wei, Wang, & Liao, Reference Huang, Wei, Wang and Liao2017) are all indispensable for sustainable organizational responses to climate change. Finding ways to communicate such expertise in a manner that resonates with researchers from other disciplines is an important step for management scholars toward gaining a stronger voice within the interdisciplinary climate science community, and a pathway to impact on policy and practice (Davis, Reference Davis2015; Rynes & Shapiro, Reference Rynes and Shapiro2005).

Limitations and future research

We hasten to add a number of limitations to our findings. First, this paper judges interdisciplinarity solely on account of the disciplinary affiliation of journals in which articles (and the corresponding references) are published. As such, any inaccuracies in the journal-level WoS categories may create bias in the assessment of interdisciplinarity (Porter, Roessner, Cohen, & Perreault, Reference Porter, Roessner, Cohen and Perreault2006; Rafols, Leydesdorff, O'Hare, Nightingale, & Stirling, Reference Rafols, Leydesdorff, O'Hare, Nightingale and Stirling2012). We further note that interdisciplinarity can be established not only on the basis of article- or journal-level disciplinary categorization, but also on account of author-team composition, e.g., based on authors' institutional affiliation. We commend such complementary work for future research as it would shed more light on the extent to which researchers are publishing outside the home discipline. Further, our findings of management scholarship's lack of impact are based on data from only two interdisciplinary journals, Science and Nature, and on a purely descriptive analysis. Future bibliometric studies may wish to investigate whether our findings extend to a broader set of interdisciplinary journals (e.g., Nature Climate Change, Climatic Change, etc.) and with that broader database may seek to develop predictive models for management scholarship's interdisciplinary impact. Ultimately, however, bibliometric methods are limited in addressing the two foremost questions arising from our findings, namely, what causes management scholarship's lack of interdisciplinary impact?, and what can be done practically to overcome the barriers to impact? To more fully address these questions, we encourage scholars to consider nonbibliometric evidence to explore a broader set of interdisciplinary practices and engagement strategies.

Conclusion

Mapping management scholarship's engagement with, and impact on, interdisciplinary climate science can aid in directing future research and engagement activities in support of the SDG of climate action. We have discussed the need and the opportunity for management scholars to explore new ways for demonstrating the social value and relevance of their expertise across disciplinary boundaries. Some of the interdisciplinary engagement activities we have sketched out may be unfamiliar and discomfiting to some academics and their institutions. Yet they echo the call issued by the President of the UN's Economic and Social Council that we ‘must move out of [our] comfort zone to pursue new ways of collective action at a much swifter pace’ (United Nations, 2019b: 2).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Loet Leydesdorff, University of Amsterdam, for his encouragement and guidance of this project, and acknowledge the constructive feedback received from ANZAM attendees. We acknowledge the generous support from the Faculty of Business & Economics, The University of Melbourne and La Trobe Business School, La Trobe University. In addition, we thank Jean-Francois Desvignes and Anthony Leal from Clarivate for their continued support throughout this investigation.

Appendix

Adjusted Disciplinary Associations for Web of Science-Indexed Management Journals

The disciplinary association of business, management, operations, and to a lesser degree finance journals to their respective subject categories in the WoS database present some challenges for bibliometric analysis. Most notably, more than 40% of journals associated with the business discipline are also associated with management, thus making the two disciplines and their bibliometric metrics hard to distinguish. Further, some disciplinary assignments are inconsistent and misaligned with journals' stated missions. For example, the journal ‘Operations Management Research’ is not assigned to the operations discipline. To be able to discriminate bibliometric characteristics between the four management disciplines in our study more clearly, we corrected inconsistencies and assigned journals to a single, primary discipline. Operations and finance journals that were also associated with management were assigned operations or finance respectively as their primary discipline. Since the distinctive characteristic of the business category (compared to the management category) is its marketing, communications, and ethics journals, we assigned all journals with such focus to the business category. All journals focused on supply chain management, logistics, information systems, and decision sciences were assigned to the operations discipline. Journals focused on general management, strategy, organization studies, organizational behavior, and human resource management were assigned to the management category. Corrective reassignments were based on journals' mission statements and, in ambiguous cases, Clarivate's Journal Citation Report data on journal relationships which, based on backward references and forward citations, identifies those journals a focal journal is most closely related to.