Introduction

In the last 30 years, research on family firms (FF) registered considerable progress research has shown that presents characteristics and strategies that distinguish them from other companies (Astrachan, Reference Astrachan2010; Chrisman, Chua, & Sharma, Reference Chrisman, Chua and Sharma2005; Chrisman, Chua, Steier, Wright, & McKee, Reference Chrisman, Chua, Steier, Wright and McKee2012; do Paço, Fernandes, Nave, Alves, Ferreira, & Raposo, Reference do Paço, Fernandes, Nave, Alves, Ferreira and Raposo2021), meaning they have gradually gained legitimacy as a field of study (Samara, Reference Samara2021). Among numerous definitions contained in the literature, Martínez, Stöhr, and Quiroga (Reference Martínez, Stöhr and Quiroga2007: 87) underline that an FF is ‘i) a firm whose ownership is clearly controlled by a family, where family members are on the board of directors or top management; ii) a firm whose ownership is clearly controlled by a group of two to four families, where family members are on the board; iii) a firm included in a family business group; and iv) a firm included in a business group associated with an entrepreneur that has designated his family successor’.

European Family Business (2020) estimates that FF account for between 65 and 80% of all companies in Europe and an important proportion of European employment (around 50%). They are considered the driver of economic recovery and the most common company worldwide (Ferrari, Reference Ferrari2021). Due to the economic well-being they provide to societies, and only a minority being able to go beyond the third generation (Cirillo, Huybrechts, Mussolino, Sciascia, & Voordeckers, Reference Cirillo, Huybrechts, Mussolino, Sciascia and Voordeckers2020; Leiß & Zehrer, Reference Leiß and Zehrer2018; Lorandini, Reference Lorandini2015; Molly, Laveren, & Deloof, Reference Molly, Laveren and Deloof2010), their continuation and organizational renewal have become reasons for concern, being one of the main challenges faced by FF as stated by several authors (Ahmad, Omar, & Quoquab, Reference Ahmad, Omar and Quoquab2021; Dodd, Theoharakis, & Bisignano, Reference Dodd, Theoharakis and Bisignano2014; Ingram & Głód, Reference Ingram and Głód2018; Venter, Boshoff, & Maas, Reference Venter, Boshoff and Maas2005). This concern for continuity is also applicable for other businesses. This low rate of ownership succession between generations highlights the importance of improving understanding of ways to facilitate an effective succession process (Sund, Melin, & Haag, Reference Sund, Melin and Haag2015).

Succession is something that most FF have in common, gaining prominence due to the retirement of numerous founders (Cadieux, Reference Cadieux2007; Chua, Chrisman, & Steier, Reference Chua, Chrisman and Steier2003; De Massis, Chua, & Chrisman, Reference De Massis, Chua and Chrisman2008; Molly, Laveren, & Deloof, Reference Molly, Laveren and Deloof2010). Note that this is also a problem faced by non-FF when it comes to the time of passing the leadership of the business (see, e.g., Ip, Reference Ip2009). Indeed, succession issue is an important topic and has inspired a large branch of literature on FF (e.g., Chrisman, Chua, & Sharma, Reference Chrisman, Chua and Sharma2005; Chua, Chrisman, & Steier, Reference Chua, Chrisman and Steier2003, Reference Chua, Chrisman, Steier and Rau2012; di Belmonte, Seaman, & Bent, Reference di Belmonte, Seaman and Bent2017; Huang, Lyu, & Zhu, Reference Huang, Lyu and Zhu2019; Joshi, Reference Joshi2017; Molly, Laveren, & Deloof, Reference Molly, Laveren and Deloof2010; Shen, Reference Shen2018; Thiele, Reference Thiele2017) and choosing an appropriate, competent successor is one of the most critical decisions for FF's survival and strategy (Amore, Minichilli, & Corbetta, Reference Amore, Minichilli and Corbetta2011; Bennedsen, Nielsen, Perez-Gonzalez, & Wolfenzon, Reference Bennedsen, Nielsen, Perez-Gonzalez and Wolfenzon2007; Carney, Zhao, & Zhu, Reference Carney, Zhao and Zhu2019; Dumas, Reference Dumas1990; Zahra & Sharma, Reference Zahra and Sharma2004).

Succession is seen as a set of actions and events leading to capital ownership and leadership transfer from one family member (Breton-Miller, Miller, & Steier, Reference Breton-Miller, Miller and Steier2004; Seaman, Bent, & Unis, Reference Seaman, Bent and Unis2016; Sharma, Chrisman, Pablo, & Chua, Reference Sharma, Chrisman, Pablo and Chua2010). This is a multi-stage, long-term process that begins before naming the successor and includes their growing involvement and effective management of family dynamics (Cabrera-Suárez, Reference Cabrera-Suárez2005; Leiß & Zehrer, Reference Leiß and Zehrer2018; Morris, Williams, & Nel, Reference Morris, Williams and Nel1996). Ahmad and Yaseen (Reference Ahmad and Yaseen2018) stress that a well-managed succession process holds on to the founders' successes and ensures the business's success in the coming years.

Various studies suggest that founders are fundamental for FF's continuity, seeking to prolong the legacy by identifying successors with the most potential (Akinbami, Adejumo, Akinyemi, Jiboye, & Obisanya, Reference Akinbami, Adejumo, Akinyemi, Jiboye and Obisanya2019; Armstrong, Reference Armstrong2012; Chirapanda, Reference Chirapanda2020; Kesner & Sebora, Reference Kesner and Sebora1994; Miller, Steier, & Le Breton-Miller, Reference Miller, Steier and Le Breton-Miller2003). Nevertheless, founders neglect and tend to postpone the succession, assuming that junior members will naturally take over the company (Ahmad, Siddiqui, & AboAlsamh, Reference Ahmad, Siddiqui and AboAlsamh2020; Ferrari, Reference Ferrari2021). Ferrari (Reference Ferrari2021) found that other mechanisms and social norms can influence the succession. Succession is also interpreted negatively and as a problem that has to be overcome, involving solid emotional questions, conflicts among members and a loss or change of identity (Dumas, Reference Dumas1990; Howorth, Westhead, & Wright, Reference Howorth, Westhead and Wright2004; Joshi, Reference Joshi2017).

FF fail for various reasons. Sometimes, due to the non-existence of a succession plan or a lack of clarity, but also due to incompetence, unpreparedness, the successor's lack of training or family rivalries (Ahmad & Yaseen, Reference Ahmad and Yaseen2018; Miller, Steier, & Le Breton-Miller, Reference Miller, Steier and Le Breton-Miller2003). Other problems are related to the lack of a successor, their lack of interest, lack of academic training, nepotism as a problem for external investors, bad governance policies, systematic family overlapping or even a harmful juridical system (Ahmad, Omar, & Quoquab, Reference Ahmad, Omar and Quoquab2021; Bjuggren & Sund, Reference Bjuggren and Sund2001; Bloemen-Bekx, Van Gils, Lambrechts, & Sharma, Reference Bloemen-Bekx, Van Gils, Lambrechts and Sharma2021; De Massis, Chua, & Chrisman, Reference De Massis, Chua and Chrisman2008; Lee, Lim & Lim, Reference Lee, Lim and Lim2003; Royer, Simons, Boyd, & Alannah, Reference Royer, Simons, Boyd and Rafferty2008; Suess-Reyes, Reference Suess-Reyes2017). On the other hand, family protocols have proven to be effective in the continuity, cohesion and performance of family businesses (Arteaga & Menéndez-Requejo, Reference Arteaga and Menéndez-Requejo2017).

Lorandini (Reference Lorandini2015) supports those successors cannot maintain the founder's entrepreneurial vitality. Then again, failure can result from a lack of balance between three overlapping systems in an FF: family, firm and ownership (Joshi, Reference Joshi2017). Therefore, failure in inter-generational succession and strategy is a challenge warranting in-depth research (di Belmonte, Seaman, & Bent, Reference di Belmonte, Seaman and Bent2017; Miller, Steier, & Le Breton-Miller, Reference Miller, Steier and Le Breton-Miller2003), recognizing the importance of planning for succession for FFs' survival (Ibrahim, Soufani, & Lam, Reference Ibrahim, Soufani and Lam2001). Brunninge, Nordqvist, and Wiklund (Reference Brunninge, Nordqvist and Wiklund2007) highlight that family dynamics influence how strategies are elaborated and implemented.

Recent years have seen a growing number of articles concentrating on succession strategies and their effects on firms (e.g., Cadieux, Reference Cadieux2007; Carney, Zhao, & Zhu, Reference Carney, Zhao and Zhu2019; Churchill & Hatten, Reference Churchill and Hatten1997; do Paço et al., Reference do Paço, Fernandes, Nave, Alves, Ferreira and Raposo2021; Dodd, Theoharakis, & Bisignano, Reference Dodd, Theoharakis and Bisignano2014; Dumas, Reference Dumas1990; El-Chaarani, Reference El-Chaarani2014; Ferrari, Reference Ferrari2021; Huang, et al., Reference Huang, Lyu and Zhu2019; Mahto, Cavazos, Calabrò, & Vanevenhoven, Reference Mahto, Cavazos, Calabrò and Vanevenhoven2021; Pan, Weng, Xu, & Chan, Reference Pan, Weng, Xu and Chan2018; Sonnenfeld & Spence, Reference Sonnenfeld and Spence1989). This shows that succession strategies are of great importance for the continuity of FF and the academic community. Researchers in strategy treated succession as one aspect by which FF aligned themselves within a competitive environment and arranged internal resources, procedures and/or practices (tacit or explicit) to maximize advantage (Kesner & Sebora, Reference Kesner and Sebora1994; Whittington, Reference Whittington2006).

Various systematic reviews have been made of the literature on FF to contextualize and define the field of research. For example, through an analysis of co-citations, Teixeira, Mota Veiga, Figueiredo, Fernandes, Ferreira, and Raposo (Reference Teixeira, Mota Veiga, Figueiredo, Fernandes, Ferreira and Raposo2020) drew up an intellectual map of the topic in the Asian context. Through a review of the literature on FF advisory bodies, Strike (Reference Strike2012) shows the determinant role of consultants for FF, despite more research being necessary for the area. Sageder, Mitter, and Feldbauer-Durstmüller (Reference Sageder, Mitter and Feldbauer-Durstmüller2018) focus on creating and maintaining FF's reputation, and Cirillo et al. (Reference Cirillo, Huybrechts, Mussolino, Sciascia and Voordeckers2020) and Conz and Magnani (Reference Conz and Magnani2020) reviewed the state-of-the-art on the growth and resilience of FF, respectively. Kesner and Sebora (Reference Kesner and Sebora1994) explored the key stages of succession research until the 80s, providing future directions and a helpful succession model. As far as we know, and despite the various systematic reviews carried out on FF, no review has provided a general, wide-ranging view of the succession strategies most commonly adopted by FF, recognizing their relevance and applicability for firms' longevity. We find great fragmentation and a consequent lack of literature systematization regarding succession in FF. We thus consider essential to analyse and provide a general, wide-ranging view of the succession in family businesses, following a strategic approach that aligns business continuity with family relationships and expectations. It is in this context that our research arises.

This study sets out from this gap identified and proposes to map the existing literature referring to FF's succession strategies, contributing to developing this field of research. It aims to map scientific publications, intellectual structure and research trends in FF succession, using content analysis techniques (Elo, Kääriäinen, Kanste, Pölkki, Utriainen, & Kyngäs, Reference Elo, Kääriäinen, Kanste, Pölkki, Utriainen and Kyngäs2014). Specifically, we seek to: (i) identify fundamental contributions to the research of FF succession strategies; (ii) present an illustrative and integrative framework, concentrating all different perspectives and connections between different clusters, and (iii) determine lines of research that form the dominant intellectual structure to contribute clearly to define a future research agenda.

To do so, this systematic literature review (SLR) covers a total of 84 articles on the Scopus database. Using techniques of bibliographic coupling and VosViewer software four thematic clusters were identified: (i) socio-emotional wealth and corporate governance, (ii) leadership and inter-generational conflicts, (iii) managing succession process and (iv) succession planning drivers. We intend to provide researchers with a more solid basis to explicitly position their contributions in the literature on FF succession, support future research in the field and provide knowledge to FF members to guide their succession strategies.

The next section presents the methods used in this systematic review. Then the results are discussed in terms of the central domains of FF succession, their intellectual and collaborative structure resulting from co-citation networks. Finally, an integrative framework was presented, and the last section presents the conclusions, suggests future research avenues and discusses the study's limitations.

Methods

Considering the evolution of publications on FF succession strategies, the state-of-the-art and the main clusters of specialization were analysed through an SLR, according to the recommendations of Gundolf and Filser (Reference Gundolf and Filser2013). SLR is suitable since it identifies and synthesizes relevant literature, compares previous studies, captures the development of knowledge in a research domain and can be applied to the management field to produce a reliable knowledge stock (Denyer & Tranfield, Reference Denyer and Tranfield2009; Paul & Criado, Reference Paul and Criado2020). We seek to offer a general view of the subject, gaps for future research and a critical number of discussions referring to ideas, theories, methods, constructs and variables (Marabelli & Newell, Reference Marabelli and Newell2014; Paul & Criado, Reference Paul and Criado2020).

The Scopus database was chosen to carry out this SLR since it provides more than 80 million articles to reliable, relevant and up-to-date research. Regarding the protocol adopted, it was decided to use the title, abstract and key words, according to the following search equation: (TITLE-ABS-KEY(‘family business’) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(‘family company’) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(‘family firm’) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(‘family enterprise’) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(succession) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(strategy)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, ‘ar’)) AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, ‘BUSI’) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, ‘ECON’) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, ‘PSYC’)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, ‘English’)).

We selected articles (document types) in business, management and accounting, and economics, econometrics and finance categories. Furthermore, we consider that succession may also have some psychological implications, and we also included this subject area, despite a small number of articles, which were simultaneously categorized in the previous areas enumerated. In the first result of Scopus, we have got 105 articles.

The next step was to organize an excel file with all the articles to monitor the reading and analysis of the articles. A total of 21 articles were excluded from this study. Two of these articles were duplicated on the database, and 19 articles were eliminated for the following reasons: (i) succession strategy was not the central aspect of the research (four articles) and/or (ii) they were case studies that did not present scientific methodology (e.g., the history of FFs published by Emerald Emerging Markets Case Studies) (15 articles). The VosViewer software was used to reinforce this perspective by showing that all this group of articles had little connection with the central nucleus of the clusters.

In addition, VosViewer was extremely useful and was used to define and clarify the clusters. This software was used for bibliographic coupling, and the units of analysis were the documents. Specifically, bibliographic coupling is a method that applies references shared among articles to determine their similarities (Zupic & Čater, Reference Zupic and Čater2015). The greater the extent of overlapping in the articles' bibliographies, the stronger the mutual level of connection. No minimum criterion of citations of articles in VosViewer was used, and after some tests, a minimum number of six articles per cluster was defined, leading to four clusters.

After applying these criteria and the protocol defined, the review contained 84 articles, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Criteria and protocol.

Next, Figure 2 presents the image generated by VosViewer, showing, besides the most cited articles in the area, four colours corresponding to clusters and the links between articles through bibliographic coupling techniques. Based on Figure 2 provided by VosViewer, we started a content analysis process of articles, explained in results analysis. Particularly, content analysis is a popular method for analysing written material. We consider the indications of Elo et al., (Reference Elo, Kääriäinen, Kanste, Pölkki, Utriainen and Kyngäs2014), who pointed out that the structure of concepts created by content analysis should be presented clearly and understandably, providing an overview of the entire result.

Figure 2. Clusters suggested by VosViewer.

Results analysis

Analysis of citations

Regarding journals, articles are also very fragmented. The 84 articles considered in this SLR were published in 48 journals. Standing out among these journals are Journal of Family Business Management (14 articles), Family Business Review (11), Journal of Family Business StratGloveregy (5), International Small Business Journal (4) and International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business (5). All the other journals have no more than two articles. This shows that the field of FFs is wide-ranging and of interest to various journal typologies, mainly linked to the topic of entrepreneurship.

In the set of articles selected, 2011 citations were recorded. Standing out here are the articles by Miller, Steier, and Le Breton-Miller (Reference Miller, Steier and Le Breton-Miller2003) with 375 citations, Zahra and Sharma (Reference Zahra and Sharma2004) with 274 citations, Zellweger (Reference Zellweger2007) with 239 citations, Yu, Lumpkin, Sorenson and Brigham (Reference Yu, Lumpkin, Sorenson and Brigham2011) with 158 citations and Howorth et al. (Reference Howorth, Westhead and Wright2004) with 117 citations. All the remaining articles have fewer than 80 citations.

Figure 3 shows that articles on FF succession strategy started to increase from 2012, and the peak of 37 articles was reached between 2018 and 2021. The year 2020 was the most productive year in publications (12 articles). Although 2021 is not yet completed, it already registers 10 publications. However, the greater demand for articles on the subject and the greater flow of citations occurred much earlier, particularly in 2003 (375 citations), 2004 (437 citations), 2007 (311 citations) and 2012 (200 citations). A total of 2357 citations were registered. The area has shown recent growth in terms of articles.

Figure 3. Number of articles vs. number of citations.

As for the methods used, the articles were divided into: (i) qualitative, (ii) quantitative, (iii) mixed and (iv) conceptual. Half of the studies presented a qualitative methodology (50%), followed by quantitative studies (27.38%) and theoretical-conceptual methodology (21.43%). Only one study used a mixed methodology.

Figure 4 gives a clearer view of the most common methods per year.

Figure 4. Methods used vs. year.

Cluster analysis

Cluster 1 (n = 26 articles): socio-emotional wealth and corporate governance

Zahra and Sharma (Reference Zahra and Sharma2004) concluded that research on FF has been increasing substantially, although it still has a long way to go, especially through the intersection of cross-disciplines. They reviewed and identified some key trends in research on FF, of which succession was highlighted. Succession processes are slow and gradual, strengthening the role of the extended family, respect for each person's role and the successor's progressive integration strategies. During this time, the older generation makes the necessary preparations to ensure harmony within the family and the firm's continuity over generations (Kamei, Boussaguet, D'Andria, & Jourdan, Reference Kamei, Boussaguet, D'Andria and Jourdan2016).

However, FF have less of a cooperative tendency than other firm typologies, prioritizing agreements with organizations in the same community, influenced by the stage of the succession process (Pittino & Visintin, Reference Pittino and Visintin2011). Zheng and Ho (Reference Zheng and Ho2012) compare and examine the evolution of corporate governance, management style and succession pattern in the Hong Kong banking sector. Zheng and Wong (Reference Zheng and Wong2016) attempt to identify ways to solve family conflicts, suggesting the mechanism of genealogical tree-pruning to reduce the effects of the centrifugal force that can destroy Craig and Moores's (Reference Craig and Moores2005) Balanced Score Card in the FF context, adding the family nature to the four perspectives. They suggest families should professionalize their management and be helped to plan the succession through this tool.

For Yacob (Reference Yacob2012), FF's prosperity can be linked to the succession process, when innovation-oriented decisions made by the new generation are just as innovative as the original business. Well-defined governance systems and robust succession plans also allow the appointment of people seriously committed to the FF's sustainability (Yacob, Reference Yacob2012).

Dodd, Theoharakis, and Bisignano (Reference Dodd, Theoharakis and Bisignano2014) concluded that entrepreneurial culture means organizational renewal, impacting FF's profits. Therefore, founders with great aspirations for future growth and succession plans in progress make renewal viable. Marchisio, Mazzola, Sciascia, Miles, and Astrachan (Reference Marchisio, Mazzola, Sciascia, Miles and Astrachan2010) also confirm the complexity of FF's corporate entrepreneurship and how this influences continuity through the generations and the firm's growth. To minimize the negative impact undertakings can have at the family level, FF can adopt an incremental strategy in financing new undertakings to minimize the impact on the family's wealth. Additionally, Dodd, Theoharakis, and Bisignano (Reference Dodd, Theoharakis and Bisignano2014) show that FF with strong family altruism are destined to stagnate.

Especially during the first years of the company, the founding CEO greatly influences the firm's strategic options (Abebe, Li, Acharya, & Daspit, Reference Abebe, Li, Acharya and Daspit2020). For Lorandini (Reference Lorandini2015), FFs have a limited life-span, with the Buddenbrooks syndrome being associated with the loss of vitality in subsequent generations. Training in the work context and transmitting family values to the new generation can mould successors' character.

Amore, Minichilli, and Corbetta (Reference Amore, Minichilli and Corbetta2011) also conclude that although non-family CEOs contribute to a significant increase in short-term debt, they are positively associated with investment related to the transition. Zellweger (Reference Zellweger2007) points out that investment strategies based on the lower cost of equity show that FF have reasons to invest in long-term projects.

Węcławski (Reference Węcławski2014) also aims to identify financing opportunities, highlighting the preservation of FF's economic independence. Bank loans are traditionally seen as the main source of external finance, though the difficulty in accessing them forces FF to consider alternative sources. In matters of financing, Thiele (Reference Thiele2017) underlines that FF generally prefer to turn to family members' internal capital to ensure control. However, non-family capital investment is a relevant alternative in some circumstances, providing additional non-financial benefits (e.g., external investors' know-how).

Various studies address non-economic orientation by FF through socio-emotional wealth (SEW) and hold on to it. SEW refers to the non-financial socioemotional wealth or ‘affective endowments’ that FF owners obtain through their controlling firm ownership (Mahto et al., Reference Mahto, Cavazos, Calabrò and Vanevenhoven2021). For this purpose, Hedberg and Luchak (Reference Hedberg and Luchak2018) study the maintenance of SEW through the founder's leadership style, identifying evasive, anxious and confident characteristics.

According to Pan et al. (Reference Pan, Weng, Xu and Chan2018), FFs should become pro-actively involved in activities with a social reach through a corporate philanthropy strategy, preserving specialized assets to ensure smooth transitions and increase the successor's visibility. El-Chaarani (Reference El-Chaarani2014) reveals key success factors related to the country's culture and economic situation, with it also necessary to address human resource management, emotional intelligence, succession plans and professionally administered family councils.

Carney, Zhao, and Zhu (Reference Carney, Zhao and Zhu2019) mention that the beginning of intra-family succession means a generational change, with family control being negatively associated with investment in R&D and positively with the results of innovation. Succession and involvement of the second generation are considered adaptive events in the company's life-cycle, allowing redefinition of its strategy (Carney, Zhao, & Zhu, Reference Carney, Zhao and Zhu2019), with an impact on corporate innovation, this effect being more pronounced in FF that try to choose members with higher levels of training and external experience (Huang, Lyu, & Zhu, Reference Huang, Lyu and Zhu2019). But despite greater general investment in innovation leading to greater competitive advantage and sustainable growth, Huang, Lyu, and Zhu (Reference Huang, Lyu and Zhu2019) underline that the new generation faces problems in building identity.

According to Ahmad and Yaseen (Reference Ahmad and Yaseen2018), factors such as customer orientation, business strategies and the board of directors, play a decisive role in the FF succession process. Their results also show that a successor's high level of education can cause the succession process to evolve. On the other hand, Akinbami et al. (Reference Akinbami, Adejumo, Akinyemi, Jiboye and Obisanya2019) wonder why FF do not go beyond Nigeria's third and fourth generation. Despite finding they have succession plans, FF differ significantly in how they implement them.

In turn, Petrů, Kramoliš, and Stuchlík (Reference Petrů, Kramoliš and Stuchlík2020) examine how successors cope with the paradox of control and autonomy, generating ambivalent emotions arising from conflicting roles, and reveal that these generate questions of belonging and contradictory aspirations of control and autonomy. Liu (Reference Liu2021) investigates how to reduce future barriers to succession and other problems related to family governance. By analysing succession roadblocks in FF, the author categorized them into four models (the ownership dilution model, sale or withdrawal model, ownership management model and dispersive ownership model) and proposes alternatives on how strategic planning can overcome the challenges of succession roadblocks.

Several authors argue that family succession in business is one of the factors in the stable growth of national economies. Klimenko and Posukhova (Reference Klimenko and Posukhova2020) analysed the socioeconomic effects of dynasties in Western countries and Russia. They concluded that the most important predictor of career choice in business is a parental business background and early formation of professional identity. Their findings also emphasize that successful succession in an FF involves preliminary planning for the transfer of management, understanding of the basic principles and continuity rules by family members.

Yu et al. (Reference Yu, Lumpkin, Sorenson and Brigham2011) review 12 years of the empirical literature, identifying 327 variables and discovering themes and structures underlying the field of research on FF. These authors say there is consensus among specialists that more attention should be paid to family activities and attitudes that influence business results and contribute to family results. In the same line, Samara (Reference Samara2021) provides an SLR on the situation of FF in the Middle East and shows that the dominant cultural traits of the patriarchal system lead to high workforce commitment.

Cluster 2 (n = 23 articles): leadership and inter-generational conflicts

Ahrens, Uhlaner, Woywode, and Zybura (Reference Ahrens, Uhlaner, Woywode and Zybura2018) suggest that former managers' involvement harms the firm's performance. When stepping down, executive leaders may feel frustrated by abandoning their heroic mission, especially when the business is transferred to an incompetent successor (Sonnenfeld & Spence, Reference Sonnenfeld and Spence1989). However, conflicts between family members, and principally bad relations among siblings, can become sensitive matters when it comes to succession, even leading to the end of FFs (Friedman, Reference Friedman1991; Sonnenfeld & Spence, Reference Sonnenfeld and Spence1989).

According to Osnes, Hök, Yanli Hou, Haug, Grady, and Grady (Reference Osnes, Hök, Yanli Hou, Haug, Grady and Grady2018), there are three patterns of succession: (1) monolithic transfer of a company and a leadership function to a family member, (2) various leadership functions distributed among the owners and (3) family members in active ownership functions with a CEO. Avrichir, Meneses, and dos Santos (Reference Avrichir, Meneses and dos Santos2016) examine the effect of separating family-controlled and family-managed from family-controlled and non-family-managed in internationalization.

Pittino, Visintin, and Lauto (Reference Pittino, Visintin and Lauto2018) suggest that individual attributes combine to generate behavioural results. Shi, Graves, and Barbera (Reference Shi, Graves and Barbera2019) seek to understand family dynamics that influence and affect owner-managers regarding the capacities available for internationalization, finding a solid connection between succession and commitment to internationalization, marked by the successor's relation with the incumbent leader. Otherwise, networks can inhibit or facilitate FF's internationalization process by perceiving opportunities in external markets, an international vision, the successor's pro-activeness and innovative spirit (Meneses, Coutinho, & Pinho, Reference Meneses, Coutinho and Pinho2014). This sets out the assumption that the successor can operate as an internal/external actor with new ideas, training and an international vision.

Di Toma and Montanari (Reference Di Toma and Montanari2012) also studied how FF's entrepreneurial process, through private equity as a governance mechanism, can sustain a business transition, re-aligning the family's interests and objectives. Among the alternative options for FF at this time, the acquisition of private capital can be selected by family owners to project their wealth invested in the FF, ensuring its continuity, growth and value-creating strategy.

Koffi, Guihur, Morris, and Fillion (Reference Koffi, Guihur, Morris and Fillion2014) argue that transitions are affected by the successor's credibility and behavioural strategy in the eyes of the firm's various publics. Bodolica, Spraggon, and Zaidi (Reference Bodolica, Spraggon and Zaidi2015) show benefits in strategies limiting forecasts of FF success, suggesting governance concepts. Basco and Bartkevičiūtė (Reference Basco and Bartkevičiūtė2016) point out the importance of FF's size for developing and implementing regional public policies, concluding that any public policy intervention should consider FF's characteristics due to their role in regional development and competitiveness. Although FF have more conservative characteristics based on lower risk, non-family managers bring about faster internationalization and a broader geographical scale (Avrichir, Meneses, & dos Santos, Reference Avrichir, Meneses and dos Santos2016).

Heryjanto, Tannady, Ihalauw, Dwiatmadja, and Harijono (Reference Heryjanto, Tannady, Ihalauw, Dwiatmadja and Harijono2020) show how supply chain management as a method leads to competitive advantage, going towards successful succession. Osnes et al. (Reference Osnes, Hök, Yanli Hou, Haug, Grady and Grady2018) explore the transfer of functions in FF that have been successful for decades, revealing ingenuity and innovation in how cases of rivalry, conflict and envy have been overcome. In these cases, consultants have a prominent role in defining strategies to identify and seek successors (Darwish, Gomes, & Bunagan, Reference Darwish, Gomes and Bunagan2020; Lenz, Schormüller, & Glückler, Reference Lenz, Schormüller and Glückler2020).

Llanos-Contreras and Jabri (Reference Llanos-Contreras and Jabri2019) highlight specific priorities of family dynamics, which cause decline and recovery strategies in FFs, concluding they are reluctant to become involved in actions that threaten their emotional wealth. Leiß and Zehrer (Reference Leiß and Zehrer2018) explore patterns of inter-generational communication and how these can impact the entrepreneurial family, identifying typologies of communication in succession.

Radu-Lefebvre and Randerson (Reference Radu-Lefebvre and Randerson2020) showed that when motivated by self-conformity and self-protection motives, successors accept the incumbent's control and manage ambivalent emotions through defensive strategies such as avoidance or compromise, which contributes to the successor's pursuit of legitimacy. McAdam, Brophy, and Harrison (Reference McAdam, Brophy and Harrison2021) explore how daughters, as successors, should become involved in the succession process in a work of identity in the succession process, considering it is the incumbent's function to shape and legitimize the daughter's succession through identity as a key process. In turn, Akhmedova and Cavallotti (Reference Akhmedova and Cavallotti2021) evaluated the motivation patterns of three groups of daughters in FF and identified important differences in extrinsic, intrinsic and ethical motivation among daughters holding different positions. These differences affect how daughters interact with their business environment and how they justify themselves as viable leaders and successors.

From the perspective of do Paço et al. (Reference do Paço, Fernandes, Nave, Alves, Ferreira and Raposo2021), the unique characteristics that family businesses have distinguish them from other businesses and highlight the experiences and obstacles that can jeopardize their continuity, particularly succession.

Ng, Tan, Sugiarto, Widjaja, and Pramono (Reference Ng, Tan, Sugiarto, Widjaja and Pramono2021) investigated large family businesses' key concerns and strategies in Indonesia to understand inter-generational succession. Based on research findings on incumbents' mindsets, they identified preferred criteria and experiences in choosing their successors, including apprenticeship learning and predisposition to entrepreneurship.

Kallmuenzer, Tajeddini, Gamage, Lorenzo, Rojas, and Schallner (Reference Kallmuenzer, Tajeddini, Gamage, Lorenzo, Rojas and Schallner2021) explore the motives, actions and meanings of multiple stakeholders involved in a succession of inter-family hospitality family businesses. The authors also reveal some success factors, namely, a clear and open communication strategy among potential successors, a well-defined succession plan and successors' active involvement. Costa, Aurora, and Spindler (Reference Costa, Aurora and Spindler2021) investigated the relationship between family succession, professionalization and internationalization in family businesses, arguing that FF can boost its internationalization by introducing succession planning and professionalization in international activities.

Ferreira, Fernandes, Schiavone, and Mahto (Reference Ferreira, Fernandes, Schiavone and Mahto2021) provided an overview of the past, present and future research in sustainability in FF through an SLR by combining different bibliometric techniques. They concluded that the literature is grouped around the following main themes: family business capital, family business strategy, family business social responsibility and family business succession.

Cluster 3 (n = 20 articles): managing succession process

According to Sonnenfeld and Spence (Reference Sonnenfeld and Spence1989), the typology of leadership can affect FF succession. Leaders are differentiated in their styles from the outset through the hero concept. The same authors suggest that an executive leader's departure can influence the organization and management style.

Dumas (Reference Dumas1990) provides key principles for managing succession process fathers–daughters successfully. The author states that the CEO's personality is an element with a profound impact on structure, culture and strategy, arguing that the FF becomes an extension of its founder, who has a role in defining the business's identity. Friedman (Reference Friedman1991) argued that sibling relationships could turn into rivalries that destroy family businesses and concluded that competition for parental love and attention stimulates sibling rivalry. Furthermore, he reinforces that adult brothers and sisters in family businesses remain organically subordinate to their parents and face unique challenges in overcoming the harmful effects of sibling rivalry, bringing implications for inter-generational succession.

Research should also seek to identify the differences between FF led by owners or elements outside the family. In this connection, Churchill and Hatten (Reference Churchill and Hatten1997) mention that family bonds and the biological imperative introduce the possibility of family succession as an alternative to selling the company, with the choice of a successor, training, development and transfer of power central topics in FFs. Janjuha-Jivraj and Woods (Reference Janjuha-Jivraj and Woods2002) explore succession experiences influenced by ethnicity, identifying mothers as ‘bumpers’ between generations. Miller, Steier, and Le Breton-Miller (Reference Miller, Steier and Le Breton-Miller2003) analysed failed succession problems and consider that inter-generational successions are affected by an inappropriate relationship between past and future, i.e., excessive attachment to the past, a rejection of the past by a rebellious one, or an incongruous blending of past and present by an unsure new leader. Ibrahim, Soufani, Poutziouris, and Lam (Reference Ibrahim, Soufani, Poutziouris and Lam2004b) study human resources in FFs, suggesting three critical factors in the human resource strategy regarding selecting a successor: leadership capacity, management skills and competences, willingness and commitment to take control of the firm.

According to Howorth, Westhead, and Wright (Reference Howorth, Westhead and Wright2004), management buy-outs and management buy-ins are an alternative solution to FF ownership, allowing independent company ownership to continue. Management buy-outs are a firm acquired by its managers outside the family, whereas management buy-in is characterized by a scenario of acquisition, where managers who do not work in the firm acquire sufficient quotas to control it. Ibrahim, McGuire, Soufani, and Poutziouris (Reference Ibrahim, McGuire, Soufani and Poutziouris2004a) trace two FF until the third generation, focusing on the intensive process of encouraging different family members' involvement, where the owners influence the firm's firm strategic direction.

Cadieux (Reference Cadieux2007) highlights a typology of functions the predecessor should take on during and after installing the successor. In this way, the previous leading role should give way to operating functions, as the supervising ‘king’ and consultant. Cater (Reference Cater2011) proposes leadership shared with various family members and leadership succession strategies at times of crisis. The founder should have a central role in conveying exclusive tacit knowledge to the successor. Armstrong (Reference Armstrong2012) explored competitive factors of human capital that can affect FFs growth and the effectiveness of generational leadership. A second generation with a more qualified leader may compromise the firm's growth if levels of tacit knowledge similar to the first-generation leader are absent. The results of Del Giudice, della Peruta, and Maggioni (Reference Del Giudice, della Peruta and Maggioni2013) demonstrate that management behaviour acts as an effective governance mechanism for FF in situations of changes in generational turnover.

Moog, Mirabella, and Schlepphorst (Reference Moog, Mirabella and Schlepphorst2011) focus on the dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation (innovation, aggressive competitiveness, risk-taking, autonomy and pro-activeness), achieving results on how owners' personal or individual orientations, predecessors and successors affect FF strategy. Scholes, Wright, Westhead, and Bruining (Reference Scholes, Wright, Westhead and Bruining2010) support this, saying that if it is impossible to identify a successor and ensure the company's survival and development, FFs owners can consider an exit via a management buy-out or management buy-in. FF can also follow non-financial interests (Scholes et al., Reference Scholes, Wright, Westhead and Bruining2010). Moreover, the choice of successor, the entry strategy, the timing of the entry and family harmony seem to be favoured when the family is involved in decision-making (Hacker & Dowling, Reference Hacker and Dowling2012). Glover (Reference Glover2013) analyses the social, cultural and symbolic capital of small FF, showing this has an essential role in family farming. The results indicate that social networks are important for farmers and their families and the transfer of knowledge that is crucial for successful succession.

di Belmonte, Seaman, and Bent (Reference di Belmonte, Seaman and Bent2017) stress that rural FF lack formalized rules and previous experience in family members, although it is preferable to have higher education. The same authors find that such firms have a succession strategy based on primogeniture, although planning is determinant. According to Ahrens et al. (Reference Ahrens, Uhlaner, Woywode and Zybura2018), the owner's involvement in the firm is positively related to performance, especially when the successor's human capital is still limited. These authors show moderating factors related to succession as a process, the relevance of the successor's attributes (human capital) and learning through succession. The predecessor's mentality is vital for FF, and it should stimulate successors both individually and inter-personally, through discovering their interests and passions, seeking to build entrepreneurial knowledge through cultural values, autonomy, role modelling and appropriate succession planning and their retirement (Tan, Supratikno, Pramono, Purba, & Bernarto, Reference Tan, Supratikno, Pramono, Purba and Bernarto2019).

Cluster 4 (n = 15 articles): succession planning drivers

Ling, Baldridge, and Craig (Reference Ling, Baldridge and Craig2012) suggest that FF with modern, cohesive family structures present greater possibilities to integrate members of the succeeding generation. This generation's involvement in decision-making and strategies is essential to prepare for leadership roles and retain organizational knowledge. Also, Rogers, Carsrud, and Krueger (Reference Rogers, Carsrud and Krueger1996) provided an exhaustive inventory of the results of the succession process, trying to forecast the strategy chosen in a given case. Dalpiaz, Tracey, and Phillips (Reference Dalpiaz, Tracey and Phillips2014) underline the role of narratives as an alternative in FFs succession processes.

Yeoh (Reference Yeoh2014) seeks to understand external CEOs' role in FF's innovative efforts, discovering a mediating effect between process innovations and financial performance. Hallak, Assaker, and O'Connor (Reference Hallak, Assaker and O'Connor2014) stress entrepreneurial self-efficacy in tourist firm performance, showing that FF in this sector did not achieve higher performance than their non-family counterparts, contradicting previous studies. Seaman, Bent, and Unis (Reference Seaman, Bent and Unis2016) highlight that the business context and the family's environment are crucial for business continuity. Even if descendants do not initially want continuity, this results in this favourable context, making it an attractive career option. Joshi (Reference Joshi2017) analyses entrepreneurship, the family condition in the firm and transition management, showing that FF can provide family members, other employees and the surrounding community with various benefits, with these differentiating factors increasing their competitive advantages.

Evidence shows that family involvement in business is beneficial for SMEs' survival and innovation capacities, and corporate social responsibility contributes to FF's longevity (Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Omar and Quoquab2021; Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Siddiqui and AboAlsamh2020). Besides the planning associated with effective succession and adaptation to constantly changing environments, Chirapanda (Reference Chirapanda2020) points out other factors representing FF sustainability, such as introducing innovations giving rise to competitive advantages, leadership and team management, and good relations with the local community.

Shen (Reference Shen2018) observed a growing interest in applying the SEW model to analyse FF's diversification strategy regarding succession, revealing that the second generation is more likely than others to diversify. Zehrer and Leiß (Reference Zehrer and Leiß2019) explore how resilience is developed through inter-generational learning during the succession, observing that family resilience is achieved through a shared vision, mutual understanding and a clear succession framework. Hillen and Lavarda (Reference Hillen and Lavarda2020) analyse an FF's budget needs in a succession process as the main moment in the organizational life-cycle.

Selcuk and Suwala (Reference Selcuk and Suwala2020) address the motivational context, resources and generational paths of migrants' FF. The results of this study show there are four real circumstances in all cases, namely, (i) little strategic planning and survival depending too much on the owner, (ii) families dependent on personal, family and collective resources, not benefiting from financing programmes, (iii) families developing their own involvement during business growth and (iv) succession adding ambivalent effects. It is necessary to create more financing opportunities for migrants' FFs and succession consultancy.

Santos, Teston, Zawadzki, Lizote, and Machado (Reference Santos, Teston, Zawadzki, Lizote and Machado2020) explore individual absorptive capacity and entrepreneurial intention in farming successors. They show that successors with perceived behavioural control assimilate and transform more knowledge that can potentially be applied to farm succession management.

Conclusion and research agenda

This research aimed to provide a general and extensive view of the succession strategies most used by FF, mapping the existing literature referring to FF succession strategies, using content analysis to identify the main research streams.

Despite the systematization carried out, research is found to be excessively fragmented. There are very diversified, albeit complementary, topics within clusters, giving a very wide-ranging perspective of the most common succession strategies. Cluster 4 was the least robust, concentrating only 17.86% of publications. Conversely, clusters 1 and 2 concentrate 30.95 and 27.38% of publications, respectively, indicating that SEW, and leadership and inter-generational conflicts are decisive factors to be considered in successful succession strategies in parallel increasing the interest of scholars. Also, managing succession processes (cluster 3) revealed to be a research topic, which aggregates a set of considerable articles (23.81%).

Articles about succession strategies are mostly found in journals devoted to the subject of FFs (e.g., Journal of Family Business Management, Journal of Family Business Strategy and Family Business Review). However, other journals on entrepreneurship are also interested in the topic, and qualitative methodologies are more common. A growing number of studies on FF succession strategies took place from 2012, although from 2018 onwards, the most productive years are registered in terms of publications.

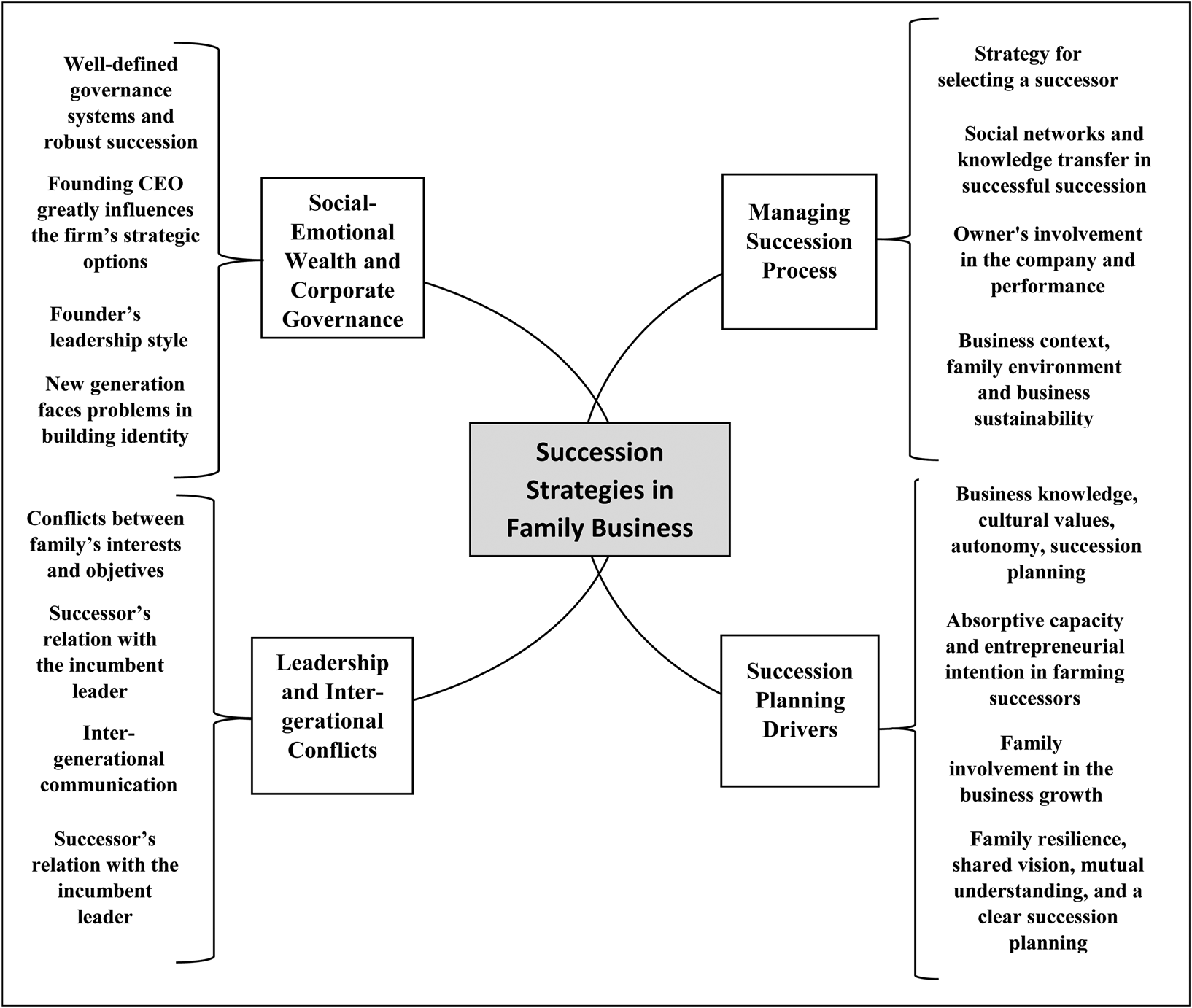

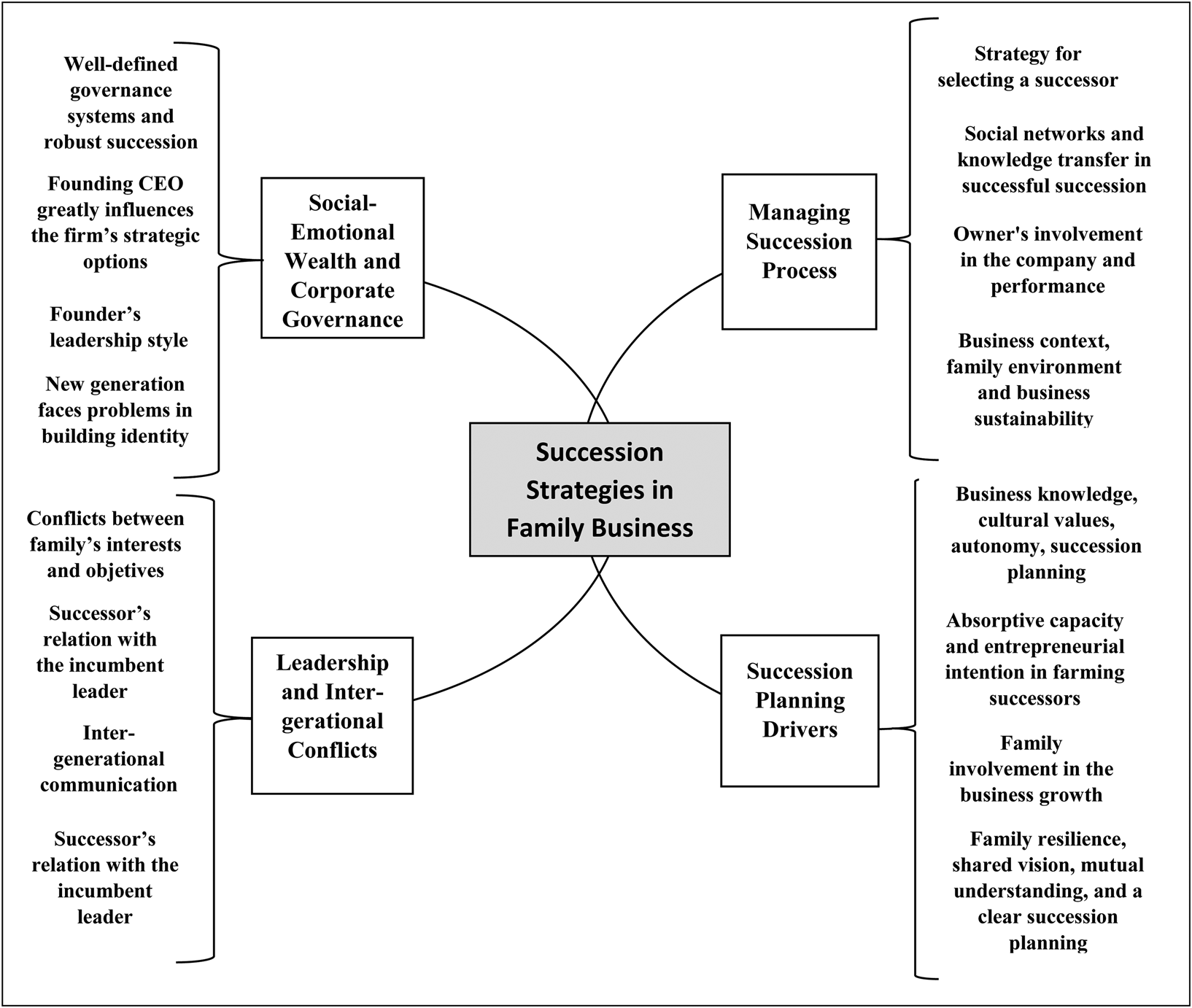

The SLR led to extracting four main strategic approaches: (i) socio-emotional wealth and corporate governance, (ii) leadership and inter-generational conflicts, (iii) managing succession process and (iv) succession planning drivers.

Figure 5 shows a comprehensive framework in family business succession strategies according to four clusters. This framework conveys results more clearly and is taken into account to report content analyses processes (Elo et al., Reference Elo, Kääriäinen, Kanste, Pölkki, Utriainen and Kyngäs2014).

Figure 5. Theoretical framework of leading succession strategies.

As can be gathered, succession is an adaptive event in the company's life-cycle, bringing new blood which influences strategy and re-aligns the firm (Carney, Zhao, & Zhu, Reference Carney, Zhao and Zhu2019). When initially gaining influence in strategic decision-making, the emerging generation may not yet have developed a major concern about the future generation of successors.

Therefore, family companies need to understand how to develop promising leaders from the second generation and ensure their success after succession (Armstrong, Reference Armstrong2012). It is important to assume that successful successions can take different ways. Kesner and Sebora (Reference Kesner and Sebora1994) verified that some authors defined a filled vacancy, others defined success as a minimum short-term organizational disruption, and others based on the market's reaction. Additionally, succession can also link family members' mental and cultural processes, even as attitudes and social norms (Ferrari, Reference Ferrari2021).

Analysis of the set of articles revealed that FF are governed, in many cases, by SEW and non-financial orientations (Hedberg & Luchak, Reference Hedberg and Luchak2018; Llanos-Contreras & Jabri, Reference Llanos-Contreras and Jabri2019; Mahto et al., Reference Mahto, Cavazos, Calabrò and Vanevenhoven2021; Scholes et al., Reference Scholes, Wright, Westhead and Bruining2010; Shen, Reference Shen2018), such as the independence, image, pride and reputation of the FF (Sageder, Mitter, & Feldbauer-Durstmüller, Reference Sageder, Mitter and Feldbauer-Durstmüller2018; Tan et al., Reference Tan, Supratikno, Pramono, Purba and Bernarto2019). Pursuing non-economic objectives is the major difference between an FF and its non-family counterparts (Zellweger, Nason, & Nordqvist, Reference Zellweger, Nason and Nordqvist2012). Yacob (Reference Yacob2012) showed that FF's prosperity is associated with succession and Węcławski (Reference Węcławski2014) highlights that an additional factor of these firms is maintaining continuity and ensuring succession for the next generation.

This study identified various strategic factors and determinants of FF continuity. Some studies indicate that succession and second-generation involvement can mean strategic redefinition with an effect on identity and innovative culture (Carney, Zhao, & Zhu, Reference Carney, Zhao and Zhu2019; Huang, Lyu, & Zhu, Reference Huang, Lyu and Zhu2019), stimulating various types of long-term investments (do Paço et al., Reference do Paço, Fernandes, Nave, Alves, Ferreira and Raposo2021). Culture, entrepreneurial orientation and corporate entrepreneurship determine continuity over the generations and FFs growth (Di Toma & Montanari, Reference Di Toma and Montanari2012; Dodd, Theoharakis, & Bisignano, Reference Dodd, Theoharakis and Bisignano2014; Marchisio et al., Reference Marchisio, Mazzola, Sciascia, Miles and Astrachan2010; Moog, Mirabella, & Schlepphorst, Reference Moog, Mirabella and Schlepphorst2011).

Various other studies indicate the personality and involvement of CEOs and leadership capacities as relevant in the succession process (Ahrens et al., Reference Ahrens, Uhlaner, Woywode and Zybura2018; Armstrong, Reference Armstrong2012; Cadieux, Reference Cadieux2007; Dumas, Reference Dumas1990; Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Soufani, Poutziouris and Lam2004b; Sonnenfeld & Spence, Reference Sonnenfeld and Spence1989; Tan et al., Reference Tan, Supratikno, Pramono, Purba and Bernarto2019). Family involvement in businesses is also beneficial for FF survival (Ahmad et al. Reference Ahmad, Siddiqui and AboAlsamh2020). In addition, effective succession planning, adaptation to constantly changing environments and the business context contribute to these companies' longevity (Akinbami et al., Reference Akinbami, Adejumo, Akinyemi, Jiboye and Obisanya2019; Chirapanda, Reference Chirapanda2020; Seaman, Bent, & Unis, Reference Seaman, Bent and Unis2016).

Focusing on and preparing the successor seems to be another strategy influencing succession. The successor's gradual, progressive integration in the company (Kamei et al., Reference Kamei, Boussaguet, D'Andria and Jourdan2016), and their customer orientation, level of education and the governance implemented in the firm are other factors to consider (Ahmad & Yaseen, Reference Ahmad and Yaseen2018). Solving possible conflicts, pruning the FF's genealogical tree (Osnes et al., Reference Osnes, Hök, Yanli Hou, Haug, Grady and Grady2018; Petrů, Kramoliš, & Stuchlík, Reference Petrů, Kramoliš and Stuchlík2020; Zheng & Wong, Reference Zheng and Wong2016), communication and succession typologies (Leiß & Zehrer, Reference Leiß and Zehrer2018) and successors' credibility in the eyes of their respective publics (Koffi et al., Reference Koffi, Guihur, Morris and Fillion2014) are found to be key strategies for FF's continuity. Communication may be the key to increasing the incumbent's willingness to let go and the successor take control of the firm and be accepted by stakeholders (Sund, Melin, & Haag, Reference Sund, Melin and Haag2015). In any case, the formalization of well-defined and early succession planning seems to be relevant (Ferrari, Reference Ferrari2021; Kallmuenzer et al., Reference Kallmuenzer, Tajeddini, Gamage, Lorenzo, Rojas and Schallner2021; Klimenko & Posukhova, Reference Klimenko and Posukhova2020), and the support of advisors (e.g., consultants) and even the nomination of non-family CEO's should be considered as succession strategy (Mahto et al., Reference Mahto, Cavazos, Calabrò and Vanevenhoven2021; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Tan, Sugiarto, Widjaja and Pramono2021).

Other interesting conclusions of this study are that the investigation of succession strategies is following different paths in each of the clusters due to the complexity of the process. Succession planning drivers lack some robustness and should be the target of further studies. We also conclude that the number of variables of succession strategies identified and reported in the literature has been increased considerably in recent years. Thus, we suggest that effective succession strategies should not be restricted to formalities, tools and traditional documents (e.g., family council, family protocol, family governance measures, etc.) that have been positively associated with the performance and transgenerational orientation of FFs, as stated by several authors (see Arteaga & Menéndez-Requejo, Reference Arteaga and Menéndez-Requejo2017; Bloemen-Bekx et al., Reference Bloemen-Bekx, Van Gils, Lambrechts and Sharma2021; Cabrera-Suárez, Reference Cabrera-Suárez2005; Suess-Reyes, Reference Suess-Reyes2017).

This study provides the first SLR on succession strategies. This is particularly useful for identifying and discussing the main research trends followed so far, but also for providing a theoretical framework and topics for future research, contributing to the evolution trajectory of this field of study. Our study also provides contributions for practitioners. Therefore, we recommend that founders, CEO's of FFs, as well as consultants specialized in the area adopt throughout the process a mix of strategic policies described in this study to ensure a smooth succession. These succession strategies reviewed can contribute to the inter-generational sustainability, business expansion and thus to the economic growth of societies.

Despite this wide-ranging approach to the theme, the study is not without limitations, such as using a single database instead of different sources to collect the information. The use of several databases would allow a more extensive coverage of the topic under analysis. Another limitation has to do with the type of document analysed. Conference proceedings, doctoral theses, textbooks and other documents related to FF and succession were excluded from the analysis.

Based on our review and findings, some future lines of research are suggested. Table 1 below presents some topics for future lines of research related to family business succession strategies, detailed by cluster. These topics were developed considering one of the following criteria: (i) articles that have recently introduced new subtopics and which, in our opinion, still lack theoretical and empirical robustness, and (ii) compilation of some future lines of investigation advanced by other articles considered in cluster analysis section. In our vision, these topics contribute to the progress of this academic field, providing more knowledge to CEOs of FF and especially answers on how to overcome some of their main succession issues.

Table 1. Suggestions for future lines of research

Acknowledgements

This project has been cofunded with support from the European Commission under the Erasmus+ Knowledge Alliances programme under Grant Agreement 2018-2547/001-001. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Financial support

This work is supported by national funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I. P., under the project ‘UIDB/04630/2020’.