In light of the acknowledgment that the positive work energy held by organizations' human resource bases plays a critical role in organizational effectiveness, over and beyond employees' ability to fulfil formal performance obligations (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kim, Woo, Park, Jo, Park and Lim2017; Quinn, Spreitzer, & Lam, Reference Quinn, Spreitzer and Lam2012), prior research underscores the challenge that organizations face when their employees develop dehumanized perceptions and treat co-workers as if they were impersonal objects, with limited care for their well-being (Boles, Dean, Ricks, Short, & Wang, Reference Boles, Dean, Ricks, Short and Wang2000; Keaveney & Nelson, Reference Keaveney and Nelson1993; Kilroy, Flood, Bosak, & Chenevert, Reference Kilroy, Flood, Bosak and Chenevert2016). Such depersonalization is a specific and pertinent manifestation of job burnout, ‘characterized by negative, callous, or excessively detached behaviour toward others’ (Jawahar, Kisamore, Stone, & Rahn, Reference Jawahar, Kisamore, Stone and Rahn2012: 246). When employees exhibit depersonalization and feel detached from their immediate work environment, their organizations suffer, because of the lower service orientations (Lee & Ok, Reference Lee and Ok2015) and increased intentions to leave (Altunoglu & Sarpkaya, Reference Altunoglu and Sarpkaya2012) that those employees tend to exhibit; the feelings of detachment also can have negative outcomes for the employees, including lower job satisfaction (Arabaci, Reference Arabaci2010) or poorer mental health (Kelloway & Barling, Reference Kelloway and Barling1991). Thus, the development of dehumanized perceptions of co-workers undermines both individual and organizational well-being, a concern that is particularly relevant in light of the importance of building positive intra-organizational relationships that counter the pressures of highly complex, competitive external environments (Leana & van Buren, Reference Leana and van Buren1999; Payne, Moore, Griffis, & Autry, Reference Payne, Moore, Griffis and Autry2011; Pooja, De Clercq, & Belausteguigoitia, Reference Pooja, De Clercq and Belausteguigoitia2016).

Beyond depersonalization, the broader concept of job burnout can be manifest in the presence of emotional exhaustion or a sense of inadequate personal accomplishment (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, Reference Maslach, Schaufeli and Leiter2001). The factors that influence employees' depersonalization towards co-workers are not necessarily the same as those that affect other aspects of job burnout though (Charoensukmongkol, Moqbel, & Gutierrez-Wirsching, Reference Charoensukmongkol, Moqbel and Gutierrez-Wirsching2016; Jackson, Turner, & Arthur, Reference Jackson, Turner and Arthur1987). Furthermore, depersonalization might be the most problematic manifestation of job burnout, because it directly affects other organizational members (Boles et al., Reference Boles, Dean, Ricks, Short and Wang2000; Gardner, Reference Gardner1987). In contrast to research that combines various aspects of job burnout into one broad measure (e.g., Miner-Rubino & Cortina, Reference Miner-Rubino and Cortina2007; Sliter & Boyd, Reference Sliter and Boyd2015; Taylor, Bedeian, Cole, & Zhang, Reference Taylor, Bedeian, Cole and Zhang2017), we focus specifically on the question of what makes employees more or less likely to develop depersonalized or dehumanized perceptions of their peers (Grunberg, Moore, & Greenberg, Reference Grunberg, Moore and Greenberg2006). This focus is critical for management scholarship; it explicitly acknowledges that different dimensions represent ‘conceptually, statistically, and practically distinct components of burnout’ (Boles et al., Reference Boles, Dean, Ricks, Short and Wang2000: 29), and it underscores the instrumental role of dedicated interpersonal relationships for an organization's effective functioning (Bachrach, Powell, Collins, & Richey, Reference Bachrach, Powell, Collins and Richey2006; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998; Ng & Van Dyne, Reference Ng and Van Dyne2005).

Several factors might influence employees' tendency to engage in withdrawal behaviours, defined in a broad sense, including individual factors such as job dissatisfaction (Keaveney & Nelson, Reference Keaveney and Nelson1993) and less proactive personalities (Jawahar et al., Reference Jawahar, Kisamore, Stone and Rahn2012) or contextual factors such as a lack of collegial support (Corrigan, Holmes, Luchins, & Buican, Reference Corrigan, Holmes, Luchins, Buican, Basit and Parks1994) or impending layoffs (Grunberg, Moore, & Greenberg, Reference Grunberg, Moore and Greenberg2006). We focus on employees' perceptions of workplace incivility, which capture their exposure to rude or discourteous behaviours by other organizational members (Pearson & Porath, Reference Pearson and Porath2005; Schilpzand, De Pater, & Erez, Reference Schilpzand, De Pater and Erez2016). Workplace incivility attracts increasing research interest and continues to be a critical concern to organizations, due to its persistence and threats to firm performance (Estes & Wang, Reference Estes and Wang2008; Johnson & Indvik, Reference Johnson and Indvik2001; Schilpzand, De Pater, & Erez, Reference Schilpzand, De Pater and Erez2016). This pertinent form of workplace adversity also imposes significant costs, due to the negative effects that experienced incivility has on employee motivation and productivity (Chen, Ferris, Kwan, Yan, & Zhou, Reference Chen, Ferris, Kwan, Yan, Zhou and Hong2013; Sliter, Sliter, & Jex, Reference Sliter, Sliter and Jex2012). Porath and Pearson (Reference Porath and Pearson2013) estimate, for example, that 98% of employees have been the victims of uncivil work behaviours, and 50% of them experience this phenomenon at least once per week. These same researchers also indicate that this ‘toxic’ work condition can generate costs of more than $10,000 per employee on an annual basis, because of the many distractions and delays that it imposes on employees' daily work functioning (Porath & Pearson, Reference Porath and Pearson2009, Reference Porath and Pearson2010). Notably, the cost of workplace incivility also may manifest itself in a more indirect way, through negative spillover effects into the home, such that the targets of rude work behaviours experience higher levels of work–family conflict and suffer lower quality relationships with their family members (Demsky, Ellis, & Fritz, Reference Demsky, Ellis and Fritz2014; Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2012). Yet another challenge associated with workplace incivility is that it operates somewhat under the radar and thus is difficult to detect and remedy (Cortina, Magley, Williams, & Langhout, Reference Cortina, Magley, Williams and Langhout2001; Porath & Pearson, Reference Porath and Pearson2010).

Despite the salience of and costs associated with workplace incivility, limited attention has centred on how this facet of workplace adversity might steer employees to exhibit depersonalization towards co-workers or on the factors that might explain the conversion of workplace incivility into such depersonalization. This study seeks to address this gap and thus add to extant research in three main ways. First, we apply conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989, Reference Hobfoll2001) to propose and demonstrate that resource-draining workplace incivility may lead to more depersonalization towards co-workers, due to the anxiety that employees experience during the execution of their job tasks (Xie & Johns, Reference Xie and Johns1995). When employees' resource bases become depleted through their exposure to adverse work situations, such as incivility, they may avoid positive behaviours and instead allocate all their energy resources to dealing with their preoccupations with their organizational functioning (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989; McCarthy, Trougakos, & Cheng, Reference McCarthy, Trougakos and Cheng2016). Second, following calls for research that applies contingency approaches to the outcomes of workplace incivility (Fida, Spence Laschinger, & Leiter, Reference Fida, Spence Laschinger and Leiter2018; Miner & Cortina, Reference Miner and Cortina2016; Schilpzand, De Pater, & Erez, Reference Schilpzand, De Pater and Erez2016; Sguera, Bagozzi, Huy, Boss, & Boss, Reference Sguera, Bagozzi, Huy, Boss and Boss2016; Welbourne, Gangadharan, & Esparza, Reference Welbourne, Gangadharan and Esparza2016), we offer novel insights into why the development of dehumanized perceptions of co-workers, in the presence of workplace incivility, might be stronger among certain employees. In particular, we apply the notion of negative resource spirals (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001) to propose that employees' gender and education exacerbate their experience of resource loss, in the form of dignity threats and associated anxiety, in response to uncivil treatment. This effect then enhances the likelihood that employees engage in depersonalization towards co-workers. Third, our study focuses on an understudied, non-Western context, Pakistan, that should be highly relevant for the tested theoretical framework. Because this country is marked by high levels of risk avoidance (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001), people with a strong cultural link to their country might feel particularly upset by work conditions that add uncertainty to their organizational functioning, as in the case of workplace incivility, which reflects a persistent challenge in many Pakistani organizations (Bibi, Karim, & Din, Reference Bibi, Karim and Din2013).

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

The challenge of workplace incivility

Workplace incivility can come in various forms, such as when co-workers make demeaning and derogatory remarks or address the focal employee in unprofessional ways (Cortina et al., Reference Cortina, Magley, Williams and Langhout2001; Lim, Cortina, & Magley, Reference Lim, Cortina and Magley2008). The salience of this unacceptable type of workplace adversity identifies it as an on-going, important challenge for organizations (Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Magley, & Nelson, Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Magley and Nelson2017). Being the victim of work incivility is embarrassing for employees (Hershcovis, Ogunfowora, Reich, & Christie, Reference Hershcovis, Ogunfowora, Reich and Christie2017) and poses a significant threat to their sense of dignity (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Bedeian, Cole and Zhang2017), to the extent that it even may prevent them from completing their job tasks (Porath & Pearson, Reference Porath and Pearson2013; Sliter, Sliter, & Jex, Reference Sliter, Sliter and Jex2012). Previous research affirms a plethora of negative outcomes of exposure to workplace incivility, such as diminished task performance (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ferris, Kwan, Yan, Zhou and Hong2013), creativity (Sharifirad, Reference Sharifirad2016), self-efficacy (Ali, Ryan, Lyons, Ehrhart, & Wessel, Reference Ali, Ryan, Lyons, Ehrhart and Wessel2016), and self-control (Rosen, Koopman, Gabriel, & Johnson, Reference Rosen, Koopman, Gabriel and Johnson2016), as well as enhanced interpersonal deviance (Wu, Zhang, Chiu, Kwan, & He, Reference Wu, Zhang, Chiu, Kwan and He2014), absenteeism, or tardiness (Sliter, Sliter, & Jex, Reference Sliter, Sliter and Jex2012). Further substantiation of this point comes from Greenblatt's (Reference Greenblatt2017) quantitative account of the negative outcomes of exposure to workplace incivility, based on a study among 800 managers across multiple industries (Porath, Reference Porath2016; Porath & Pearson, Reference Porath and Pearson2010). Specifically, the findings indicate that ‘48% intentionally decreased work effort; 47% intentionally decreased time at work; 38% intentionally decreased work quality; 80% lost work time worrying about the incident; 63% lost time avoiding the offender; 66% said their performance declined; 78% said their commitment to the organization declined; [and] 12% said they exited the organization as a result of their uncivil treatment’ (Greenblatt, Reference Greenblatt2017: 13).

Workplace incivility also might spur job burnout (Loh & Loi, Reference Loh and Loi2018; Rahim & Cosby, Reference Rahim and Cosby2016), though limited research has considered its potential influence on the depersonalization dimension of burnout specifically – with one exception. Beattie and Griffin (Reference Beattie and Griffin2014) find a positive relationship between employees' perceptions of the severity of an uncivil event and their ignorance or avoidance of the instigator of the event. In this study, we explicate (1) why employees' exposure to workplace incivility might escalate into depersonalization towards co-workers and (2) when this process is more likely to unfold. Our focus on predicting the likelihood that employees develop dehumanized perceptions of their co-workers underscores the negative consequences that exposure to workplace civility might have for the quality of interpersonal relationships, over and beyond a general sense of burnout (Boles et al., Reference Boles, Dean, Ricks, Short and Wang2000; Grunberg, Moore, & Greenberg, Reference Grunberg, Moore and Greenberg2006). Moreover, previous research has shown that feelings of anxiety might function as causal mechanisms that link adverse work circumstances, such as role conflict (Mohr & Puck, Reference Mohr and Puck2007) or group conflict (Hon & Chan, Reference Hon and Chan2013), with negative work outcomes. We similarly propose that the influence of exposure to workplace incivility on depersonalization towards co-workers moves through concerns that employees develop about their own job situation (Baba & Jamal, Reference Baba and Jamal1991).

In addition, despite a general sense that workplace incivility undermines the quality of employees' organizational functioning, previous research offers only equivocal support for its detrimental effects on work outcomes (Estes & Wang, Reference Estes and Wang2008; Loi, Loh, & Hine, Reference Loi, Loh and Hine2015; Schilpzand, De Pater, & Erez, Reference Schilpzand, De Pater and Erez2016). This ambiguity might arise because employees exhibit varied responses to rude co-workers, depending on their surrounding work context (e.g., whether colleagues receive uncivil treatments too; Schilpzand, Leavitt, & Lim, Reference Schilpzand, Leavitt and Lim2016) but also personal factors (e.g., coping styles; Welbourne, Gangadharan, & Esparza, Reference Welbourne, Gangadharan and Esparza2016). We investigate how employees' gender and education level might stimulate the transformation of their exposure to workplace incivility into job-related anxiety and then depersonalization towards co-workers. In so doing, we focus on two critical contingencies of the process that links workplace incivility to enhanced withdrawal, in response to calls for studies of how individual differences might explain negative consequences of workplace incivility (Abubakar, Namin, Harazneh, Arasli, & Tunç, Reference Abubakar, Namin, Harazneh, Arasli and Tunç2017; Welbourne, Gangadharan, & Esparza, Reference Welbourne, Gangadharan and Esparza2016; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Zhang, Chiu, Kwan and He2014).

Theoretical lens: COR theory

To substantiate our theoretical predictions, we draw from COR theory. This theory postulates that employees' exposure to adverse work conditions links to negative work attitudes or behaviours through experiences of resource depletion, then prompts a subsequent motivation to conserve resources in work-related efforts (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989, Reference Hobfoll2001; McCarthy, Trougakos, & Cheng, Reference McCarthy, Trougakos and Cheng2016). For example, COR theory helps explain how employees' exposure to dysfunctional organizational politics (Abbas, Raja, Darr, & Bouckenooghe, Reference Abbas, Raja, Darr and Bouckenooghe2014) or family-to-work conflict (De Clercq, Rahman, & Haq, Reference De Clercq, Rahman and Haq2019) steers them away from positive work behaviours. Similarly, we argue that employees' exposure to workplace incivility may generate resource losses, in the form of affronts to their dignity and associated preoccupations about their organizational functioning (Andersson & Pearson, Reference Andersson and Pearson1999; Hershcovis et al., Reference Hershcovis, Ogunfowora, Reich and Christie2017), such that they seek to undo that loss by conserving energy and not caring any more about the well-being of their co-workers (Hobfoll & Shirom, Reference Hobfoll, Shirom and Golembiewski2000).

Formally, we propose that an important reason workplace incivility enhances depersonalization towards co-workers resides in employees' resource loss, as manifest in their job-related feelings of anxiety (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001). Such anxiety captures the strain that employees experience during the execution of their job tasks, emerging as worries about their organizational functioning and ability to fulfil their job duties (Parker & DeCotiis, Reference Parker and DeCotiis1983; Xie, Reference Xie1996). To the extent that employees believe their co-workers treat them with disrespect, their resulting concerns about their job situation (Schilpzand, Leavitt, & Lim, Reference Schilpzand, Leavitt and Lim2016; Sliter & Boyd, Reference Sliter and Boyd2015) may lead them to dehumanize other organizational members and stop caring for their well-being. Previous research acknowledges that exposure to workplace incivility depletes employees' positive energy reservoirs (Abubakar, Reference Abubakar2018; Geldart, Langlois, Shannon, Cortina, & Griffith, Reference Geldart, Langlois, Shannon, Cortina, Griffith and Haines2018; Lim, Cortina, & Magley, Reference Lim, Cortina and Magley2008), but it has not explicitly examined how such energy depletion, in the form of job-related anxiety, might drive employees to exhibit depersonalization towards co-workers (Maslach, Reference Maslach1982).

Moreover, COR theory and its underlying notion of negative resource spirals (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001, Reference Hobfoll2011) suggests that the harmful effect of employees' perceptions of workplace adversity is invigorated to the extent that they possess personal characteristics or operate in work conditions that exacerbate their experience of resource loss after such exposures. For example, employees' exposure to unfair information provision diminishes their job performance to a greater extent in the presence of political organizational climates (De Clercq, Haq, & Azeem, Reference De Clercq, Haq and Azeem2018). Similarly, we propose that the indirect effect of workplace incivility on depersonalization towards co-workers through job-related anxiety should be particularly strong among male employees, compared with their female counterparts, and among employees with higher education levels. That is, we predict male and higher-educated employees may be more likely to experience losses in personal dignity when they are treated with disrespect – particularly in the empirical context of this study, Pakistan, with its male-dominated culture (Ali & Syed, Reference Ali and Syed2017; Strachan, Adikaram, & Kailasapathy, Reference Strachan, Adikaram and Kailasapathy2015) and strict educational stratification (Ali, Reference Ali2014; Memon, Reference Memon2006). Therefore, the escalation of workplace incivility into enhanced job-related anxiety and subsequent depersonalization towards co-workers might be higher among these employees.

The proposed invigorating role of gender (i.e., being male) is particularly notable in light of previous ambiguous findings about how this personal characteristic influences the outcomes of workplace civility. For example, female employees, compared with their male counterparts, are more frequent victims of workplace incivility (Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Leskinen, Huerta, & Magley, Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Leskinen, Huerta and Magley2013) and experience greater psychological distress in its presence (Abubakar, Reference Abubakar2018). But they also might exhibit less withdrawal behaviour due to a greater tolerance for uncivil behaviours (Loi, Loh, & Hine, Reference Loi, Loh and Hine2015). In contrast, male employees often respond to incivility in more overt ways, by withdrawing from their immediate work environment or confronting instigators, rather than in covert ways, such as gossiping in their social network (Pearson, Andersson, & Wegner, Reference Pearson, Andersson and Wegner2001). Male employees also tend to perceive greater injustice, compared with their female counterparts, when they observe uncivil treatment of women at work (Miner & Cortina, Reference Miner and Cortina2016). Yet the two genders engage in similar levels of organizational withdrawal when their employer is lax with respect to hostile co-worker behaviours (Miner-Rubino & Cortina, Reference Miner-Rubino and Cortina2007).

In a male-dominated context such as Pakistan (Jalal, Reference Jalal and Kandiyoti1991; Strachan, Adikaram, & Kailasapathy, Reference Strachan, Adikaram and Kailasapathy2015), COR theory suggests that male employees may experience particularly strong resource losses in the form of reduced dignity when they are the victims of rude or discourteous behaviours, so they may be more likely to respond negatively to this situation with depersonalized interactions with colleagues (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001; Porath, Overbeck, & Pearson, Reference Porath, Overbeck and Pearson2008). Similarly, the status and privileges that come with education in Pakistani society make it likely that employees with education-related status sense greater affront when they are treated in ways that do not align with their credentials (Ali, Reference Ali2014; Buchmann & Hannum, Reference Buchmann and Hannum2001). Thus the core research issues – the role of job-related anxiety in connecting resource-draining workplace incivility with depersonalization towards co-workers, and the invigorating roles of being male and more educated in this process – are highly pertinent for the empirical context of this study, and they also should have great relevance for other countries with cultural profiles that align with Pakistan's.

Figure 1 summarizes the proposed theoretical framework, and its constitutive hypotheses are detailed in the next section.

Figure 1. Conceptual model

Hypotheses

Mediating role of job-related anxiety

We predict a positive relationship between employees' exposure to workplace incivility and their job-related anxiety. When employees are treated with disrespect, they experience resource losses in the form of threats to their dignity (Cortina et al., Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Magley and Nelson2017; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Bedeian, Cole and Zhang2017). According to COR theory, such resource depletion caused by rude co-worker treatment may become so distracting that it adds stress about their ability to meet their job obligations (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989; Ng & Feldman, Reference Ng and Feldman2012; Sliter, Sliter, & Jex, Reference Sliter, Sliter and Jex2012). Employees tend to feel more energized and in control of their work tasks if they believe their colleagues treat them with respect and provide encouraging instead of derogatory remarks (Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Koopman, Gabriel and Johnson2016). Conversely, if employees sense that their colleagues are condescending and show limited respect for their dignity, the associated energy depletion may prevent them from meeting job expectations (Cho, Bonn, Han, & Lee, Reference Cho, Bonn, Han and Lee2016), which fuels anxiety about their organizational functioning (McCarthy, Trougakos, & Cheng, Reference McCarthy, Trougakos and Cheng2016).

In addition to increasing concerns about their ability to perform adequately, the perceived threats to their dignity caused by workplace incivility may generate negative emotions about their job. Employees who are treated in a condescending manner by other members likely experience frustration or anger, which undermines their satisfaction with their career situation in general (Lim, Cortina, & Magley, Reference Lim, Cortina and Magley2008). Employees' anxiety about their jobs thus should be higher when they are overcome by negative emotions because others fail to show respect for their dignity or feelings (Hon & Chan, Reference Hon and Chan2013). Exposure to workplace incivility similarly might generate doubts among employees about whether their daily work efforts are appreciated, to the extent that they interpret the incivility as a signal of limited confidence in their ability to contribute (Pearson & Porath, Reference Pearson and Porath2005). This misattribution may generate further negative emotions about their job situation and worries about whether there is a future for them in the organization. Taken together, these arguments suggest that employees' job-related anxiety should increase in response to increasing levels of workplace incivility.

Hypothesis 1

There is a positive relationship between employees' exposure to workplace incivility and their job-related anxiety.

In turn, we posit that employees' feelings of job-related anxiety increase their depersonalization towards co-workers. As noted, such anxiety implies that employees are preoccupied with their organizational functioning and worry about their ability to meet the employer's expectations (McCarthy, Trougakos, & Cheng, Reference McCarthy, Trougakos and Cheng2016; Xie & Johns, Reference Xie and Johns1995). According to COR theory, employees' job-related anxiety should spur passiveness towards co-workers because they feel motivated to conserve valuable energy resources when experiencing stress at work (Hobfoll & Shirom, Reference Hobfoll, Shirom and Golembiewski2000). Similarly, the presence of job-related anxiety tends to steer employees' energy resources towards negative activities, such as ruminating or complaining, leaving less room for positive behaviours, such as caring for other organizational members (Netemeyer, Maxham, & Pullig, Reference Netemeyer, Maxham and Pullig2005). The energy-draining effect of job-related anxiety thus implies that employees are less likely to dedicate energy to positive activities, such that they exhibit more indifference to co-workers.

Employees who experience significant anxiety about their organizational functioning also tend to identify less strongly with their organization and be less actively involved in their work (Masihabadi, Rajaei, Koloukhi, & Parsian, Reference Masihabadi, Rajaei, Koloukhi and Parsian2015; Quinn, Spreitzer, & Lam, Reference Quinn, Spreitzer and Lam2012), which may spur them to withdraw from their immediate work environment. Conversely, employees who experience low job-related anxiety likely are motivated to engage in positive activities, from which their co-workers and organization can benefit, rather than closing themselves off from others. That is, when employees experience lower job-related anxiety, they should feel more energized and excited by the prospect of attending to their co-workers' needs (Eatough, Chang, Miloslavic, & Johnson, Reference Eatough, Chang, Miloslavic and Johnson2011; Netemeyer, Maxham, & Pullig, Reference Netemeyer, Maxham and Pullig2005). Thus we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2

Employees' job-related anxiety relates positively to their depersonalization towards co-workers.

Combining the preceding arguments, we predict a mediating role of job-related anxiety, such that employees' resource depletion, associated with their exposure to workplace incivility, enhances their depersonalization towards co-workers because of their enhanced job-related anxiety. Employees who sense threats to their personal resource of dignity, because co-workers treat them discourteously, are more likely to withdraw from their immediate work environment, because they worry excessively about their ability to function in a context marked by such treatment (Estes & Wang, Reference Estes and Wang2008; Schilpzand, Leavitt, & Lim, Reference Schilpzand, Leavitt and Lim2016). An important explanatory mechanism that may underpin the relationship between workplace incivility and enhanced depersonalization towards co-workers thus is the level of anxiety that employees experience when performing their work. Previous research similarly proposes a mediating role of job-related anxiety between other workplace stressors, such as unethical work climates (Jaramillo, Mulki, & Solomon, Reference Jaramillo, Mulki and Solomon2006) or work–family conflict (Netemeyer, Maxham, & Pullig, Reference Netemeyer, Maxham and Pullig2005), and diminished positive work outcomes. We extend such claims by predicting:

Hypothesis 3

Employees' job-related anxiety mediates the relationship between their exposure to workplace incivility and their depersonalization towards co-workers.

Moderating role of gender

Consistent with the notion of negative resource spirals (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001, Reference Hobfoll2011), we anticipate that the escalation of employees' exposure to workplace incivility into enhanced job-related anxiety depends on the extent to which their personal characteristics make the associated loss in personal dignity more prominent. Previous research indicates that men are more offended when they suffer dysfunctional workplace dynamics, such as when they receive demeaning or unprofessional comments (Kaukiainen et al., Reference Kaukiainen, Salmivalli, Björkqvist, Österman, Lahtinen, Kostamo and Lagerspetz2001; Porath, Overbeck, & Pearson, Reference Porath, Overbeck and Pearson2008), an issue that may be exacerbated in male-dominated cultures in which men tend to have more status than women (Ali & Syed, Reference Ali and Syed2017; Syed, Ali, & Winstanley, Reference Syed, Ali and Winstanley2005). According to COR theory, the escalation of resource-draining workplace incivility into enhanced job-related anxiety might be more likely among male employees, because they experience greater affront and dignity loss in the presence of disrespectful treatments (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2011; Hobfoll & Shirom, Reference Hobfoll, Shirom and Golembiewski2000). Men also tend to have a strong desire to be in control of their job situation (Hochwarter, Perrewé, & Dawkins, Reference Hochwarter, Perrewé and Dawkins1995), but that desire may be compromised if they perceive that others show little interest in their opinions or treat them derogatorily (Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Koopman, Gabriel and Johnson2016). This negative situation then should intensify their feelings of job-related anxiety in response to workplace incivility.

The invigorating role of being male also aligns with the premises of social role theory. According to this theory, the ways that employees experience adverse work conditions are regulated by social norms and expectations (Eagly & Crowley, Reference Eagly and Crowley1986), including the normative, gender-based expectations they might have about how people should treat one another (Mesch, Brown, Moore, & Hayat, Reference Mesch, Brown, Moore and Hayat2011; Schminke, Ambrose, & Miles, Reference Schminke, Ambrose and Miles2003). The role status that comes with being male in a male-dominated culture such as Pakistan implies that male employees have higher expectations of the respect that ‘should’ be accorded to them in the workplace (Ali & Syed, Reference Ali and Syed2017), which may intensify their interpretation of uncivil treatments as embarrassing attacks, thereby enhancing their job-related feelings of anxiety (Andersson & Pearson, Reference Andersson and Pearson1999; Hershcovis et al., Reference Hershcovis, Ogunfowora, Reich and Christie2017). Finally, the proposed triggering effect of being male echoes the more general argument that men tend to exhibit more ego involvement than women (Domangue & Solmon, Reference Domangue and Solmon2010; Kaukiainen et al., Reference Kaukiainen, Salmivalli, Björkqvist, Österman, Lahtinen, Kostamo and Lagerspetz2001), such that their sense of dignity may be undermined to a greater extent when they are the victims of incivility. Accordingly, they might feel particularly distressed by this source of workplace adversity.

Hypothesis 4

The positive relationship between employees' exposure to workplace incivility and their job-related anxiety is moderated by their gender, such that this positive relationship is stronger among male than among female employees.

Moderating role of education level

We similarly predict an invigorating effect of employees' education level on the positive relationship between their exposure to workplace incivility and job-related anxiety. The contrast between being treated disrespectfully in the workplace and the prestige that tends to come with higher educational levels may be perceived as an affront to their personal resource of dignity (Cortina et al., Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Magley and Nelson2017; Kane & Montgomery, Reference Kane and Montgomery1998) – an issue that is highly pertinent in a class-driven society such as Pakistan (Buchmann & Hannum, Reference Buchmann and Hannum2001; Memon, Reference Memon2006) – such that higher-educated employees become particularly preoccupied with their job situation and how they fit with their organization when others treat them in a condescending manner (Estes & Wang, Reference Estes and Wang2008). Following COR theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001), to the extent that employees believe that their educational credentials deserve consideration and respect, the resource-draining effect of their exposure to workplace incivility, as manifest in their sense of dignity loss, should be stronger among employees who hold higher educational credentials, such that they become particularly distressed in the presence of disrespectful treatments (Schilpzand, Leavitt, & Lim, Reference Schilpzand, Leavitt and Lim2016).

Moreover, previous research indicates that education can increase people's awareness of dysfunctional or unethical practices, so highly educated employees may be more sensitive to a lack of professionalism in intra-organizational exchanges (Miller, Reference Miller2009; Rest, Reference Rest1986). Employees with more education also may exhibit greater commitment to the well-being of their organization (Mottaz, Reference Mottaz1986; Pooja, De Clercq, & Belausteguigoitia, Reference Pooja, De Clercq and Belausteguigoitia2016), including a greater sensitivity to violations of implicit rules about how colleagues should treat one another to meet organizational goals. Conversely, less educated employees may experience disrespectful and rude treatments as less threatening to their personal dignity or to organizational well-being, so their exposure to workplace incivility may be less likely to translate into enhanced job-related anxiety.

Hypothesis 5

The positive relationship between employees' exposure to workplace incivility and their job-related anxiety is moderated by their education level, such that this positive relationship is stronger among more highly educated employees.

These arguments also suggest the presence of moderated mediation effects (Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, Reference Preacher, Rucker and Hayes2007), such that gender and education may function as critical contingencies of the indirect effect of employees' exposure to workplace incivility on their depersonalization towards co-workers through their job-related anxiety. Such moderated mediation implies that for male and more educated employees, the role of job-related anxiety as a causal mechanism that explains the positive relationship of workplace incivility and depersonalization towards co-workers should be stronger. In particular, being male and having more education intensifies the experience of dignity loss due to being treated in disrespectful ways (Kane & Montgomery, Reference Kane and Montgomery1998; Porath, Overbeck, & Pearson, Reference Porath, Overbeck and Pearson2008), and this experience increases employees' propensity to conserve energy resources and engage in depersonalization towards co-workers, due to preoccupations about their organizational functioning. In short, to the extent that individual characteristics, such as being male and more educated, intensify a sense of affront associated with resource-draining disrespectful treatments, employees' job-related anxiety may offer a more pertinent explanation of why such treatments contribute to enhanced depersonalization towards co-workers (Hobfoll & Shirom, Reference Hobfoll, Shirom and Golembiewski2000).

Hypothesis 6

The indirect relationship between employees' exposure to workplace incivility and their depersonalization towards co-workers through their enhanced job-related anxiety is moderated by their (a) gender and (b) education, such that this indirect relationship is stronger among male and more educated employees.

Research Method

Sample and data collection

To test the hypotheses, we collected survey data from employees in six Pakistani-based organizations that operate in the telecommunications sector. This sector is highly competitive in this country, and organizational decision makers must promote and nurture positive interpersonal relationships among their employee bases and encourage them to support one another if they are to meet organizational goals (Imran, Majeed, & Ayub, Reference Imran, Majeed and Ayub2015; Malik, Saleem, & Naeem, Reference Malik, Saleem and Naeem2016). In turn, employees in this sector tend to encounter high levels of job stress, due to internal and external pressures, which may generate negative feelings about their organizational functioning or undermine their ability to meet pre-set performance targets (Mansoor, Fida, Nasir, & Ahmad, Reference Mansoor, Fida, Nasir and Ahmad2011). An investigation of how the experience of adverse work situations may prompt employees to grow indifferent to the well-being of their co-workers, and the critical role of their job-related feelings of anxiety in the process, thus is a pertinent issue in this empirical context.

One of the authors relied on existing professional contacts to identify targeted organizations; after receiving organizational approval, this author conducted personal visits to their sites to distribute surveys to possible participants. Among the six participating organizations, five were private telecom companies, and one organization was a public telecom operator. The size of the organizations ranged between 3,300 and 4,500 employees. To ensure representativeness, the targeted participants belonged to a wide range of departments, including operations, IT, sales, marketing, and administration, and they operated at different hierarchical levels (i.e., lower, middle, and upper management). The surveys were in English, which is the official language of higher education and business practice in Pakistan. Participation was completely voluntary, and participants were guaranteed that their organization would not know who participated in the research. After completing the surveys, the participants placed them in sealed envelopes and returned them to the same author. Although they learned that the insights generated from the findings would benefit their organization, the respondents did not receive any monetary or other incentive to participate.

The data collection process itself entailed three rounds of paper-and-pencil surveys, with a 3-week time lag between each round. These time lags were long enough to minimize concerns about reverse causality but short enough to avoid the possibility that significant organizational events might occur during the study. The 3-week time lag also reduced the likelihood of expectancy bias or the risk that participants might answer the questions in ways consistent with their predictions of the research hypotheses – that is, that rude behaviours by other organizational members ‘inevitably’ add stress to their organizational functioning or that job-related anxiety gives employees the ‘right’ to dehumanize co-workers. The first survey asked employees about their exposure to workplace incivility, gender, and education level; the second survey assessed their job-related anxiety; and the third survey captured their depersonalization towards co-workers. For each survey round, the research goal was clearly explained, with special care taken to guarantee participants' complete confidentiality. In particular, we emphasized that the responses would be accessible only to the research team, no individual information would ever be communicated, and only aggregate data would be available beyond the research team. The survey also mentioned that there were no correct or incorrect answers, with explicit requests that participants answer the questions as honestly as possible, to diminish the likelihood of acquiescence and social desirability biases (Spector, Reference Spector2006).

A total of 1,820 surveys were randomly distributed to possible participants in the six organizationsFootnote 1. The targeted participants were selected by randomly choosing names from employee lists provided by the human resource departments of the participating organizations. Of the 1,820 originally administered surveys, 1,003 were returned in the first round, with a response rate of 55%. In the second round, 711 respondents completed the survey, representing a response rate of 71%. In the third round, we received 523 surveys, with a response rate of 74%. After removing surveys with missing data, we retained 507 completed sets of surveys for the analyses. Among these respondents, 63% were men, their average age was 30 years, and 74% worked in middle or upper managementFootnote 2.

Measures

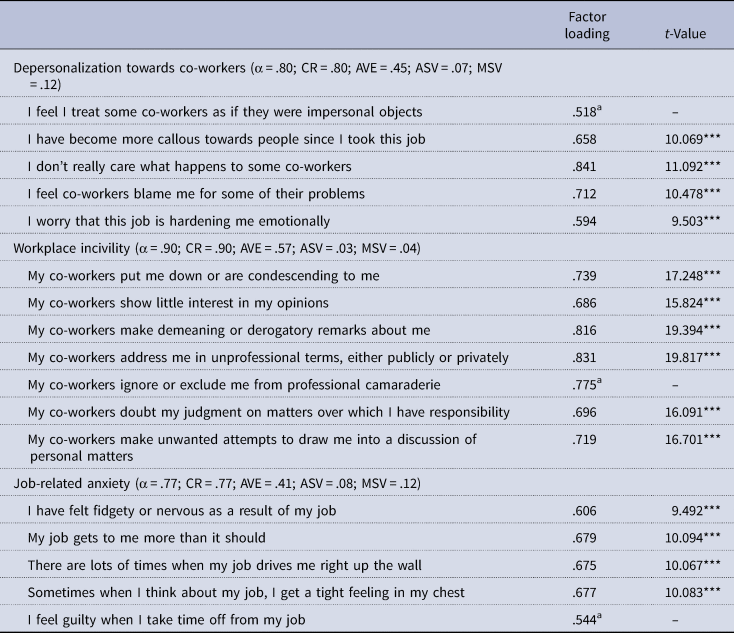

The measures of the focal constructs used items from previous research, with 5-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘strongly agree’). Table 1 provides a summary of the measurement items.

Table 1. Constructs and measurement items

a Initial loading was fixed to 1 to set the construct scale.

ASV = average shared variance; AVE = average variance extracted; CR = construct reliability; MSV = maximum shared variance; α = Cronbach's α.

Depersonalization towards co-workers

To measure employees' depersonalization in relation to their colleagues, we used a 5-item scale based on previous research (Boles et al., Reference Boles, Dean, Ricks, Short and Wang2000; Jawahar et al., Reference Jawahar, Kisamore, Stone and Rahn2012). Three sample items were ‘I treat some co-workers as if they were impersonal objects’, ‘I have become more callous toward people since I took this job’, and ‘I don't really care what happens to some co-workers’ (Cronbach's α = .80).

Workplace incivility

We measured workplace incivility with a seven-item scale used in previous research (e.g., Cortina et al., Reference Cortina, Magley, Williams and Langhout2001; Lim, Cortina, & Magley, Reference Lim, Cortina and Magley2008; Taylor, Bedeian, & Kluemper, Reference Taylor, Bedeian and Kluemper2012). Sample items included ‘My co-workers put me down or are condescending to me’, ‘My co-workers address me in unprofessional terms, either publicly or privately’, and ‘My co-workers make demeaning or derogatory remarks about me’ (Cronbach's α = .90).

Job-related anxiety

To measure employees' job-related anxiety, we relied on the five items of the job-related feelings of anxiety scale, developed by Parker and DeCotiis (Reference Parker and DeCotiis1983) and applied in subsequent studies (e.g., Baba & Jamal, Reference Baba and Jamal1991; Xie, Reference Xie1996). The respondents indicated, for example, whether ‘I have felt fidgety or nervous as a result of my job’, ‘Sometimes when I think about my job I get a tight feeling in my chest’, and ‘There are lots of times when my job drives me right up the wall’ (Cronbach's α = .77).

Gender

Employees' gender was measured with a dummy variable, using female as the base category (0 = female; 1 = male).

Education

We assessed employees' educational levels with a 5-point scale, with the following categories: secondary school, non-university post-secondary, bachelor, master, and doctoral degrees.

A confirmatory factor analysis that applied a 3-factor model supported the convergent and discriminant validity of the three multi-item constructs (i.e., depersonalization towards co-workers, workplace incivility, and job-related anxiety). The fit of this model was good: χ2(116) = 319.69, normed fit index (NFI) = .91, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = .93, confirmatory fit index (CFI) = .94, and root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) = .06. The factor loadings shown in Table 1 provide evidence of convergent validity, in that they are strongly significant for each item (p < .001; Gerbing & Anderson, Reference Gerbing and Anderson1988)Footnote 3. Moreover, in support of the discriminant validity of the three constructs, for each construct pair, the fit of the constrained model, in which the correlation between two constructs is set to 1, is significantly worse than the fit of the corresponding unconstrained model, in which the correlation between the constructs could vary freely (Δχ2(1) > 3.84; Anderson & Gerbing, Reference Anderson and Gerbing1988). As further evidence of discriminant validity, the inter-construct correlations are smaller than the square roots of the corresponding average variance extracted (AVE), and the values of the average shared variance and maximum shared variance are smaller than the AVEs (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2009).

We also undertook two tests to check for common method bias. First, Harman's single-factor test (Podsakoff & Organ, Reference Podsakoff and Organ1986), based on an exploratory factor analysis with all items of the focal constructs, shows that the first factor accounted for only 28% of the total variance. Second, the fit of a one-factor model, based on a confirmatory factor analysis, is very poor (χ2(119) = 1,595.70, NFI = .55, TLI = .50, CFI = .56, RMSEA = .16), significantly worse (Δχ2(3) = 1,276.01, p < .001) than the fit of the aforementioned three-factor model, which alleviates concerns about common method bias.

Results

We provide the correlations and descriptive statistics in Table 2; the regression results are provided in Table 3. Models 1–3 predicted job-related anxiety, and Models 4 and 5 predicted depersonalization towards co-workers. For each model, the variance inflation factor values were lower than 10, so multicollinearity was not a concern (Aiken & West, Reference Aiken and West1991).

Table 2. Correlations and descriptive statistics

Note: n = 507.

*p < .05; **p < .01.

Table 3. Regression results

Note: n = 507.

*p < .05; ***p < .001.

According to Hypothesis 1, employees who perceive they are treated with disrespect or rudeness should be more likely to worry about their work situation. We find support for this hypothesis in the positive relationship between exposure to workplace incivility and job-related anxiety in Model 1 (β = .166, p < .001). We also find support for Hypothesis 2, in that the experience of anxiety prompts employees to exhibit less care for the well-being of their colleagues, according to the positive relationship between their job-related anxiety and depersonalization towards co-workers in Model 5 (β = .438, p < .001).

To test Hypothesis 3, which argues for the presence of mediation by perceptions of job-related anxiety, we follow the three-step approach suggested by Baron and Kenny (Reference Baron and Kenny1986). First, the initial results indicate a significant, positive relationship between the independent and mediator variables, as well as between the mediator and dependent variables. Second, when accounting for the effect of perceptions of job-related anxiety, the negative relationship between workplace incivility and depersonalization towards co-workers in Model 4 (β = .179, p < .05) becomes insignificant in Model 5 (β = .106, ns). Thus, perceptions of job-related anxiety fully mediate the relationship between workplace incivility and depersonalization towards co-workers. To confirm the mediation by job-related anxiety, we use the bootstrapping method suggested by Preacher and Hayes (Reference Preacher and Hayes2004), which provides confidence intervals (CIs) for the indirect effects to avoid potential statistical power problems that might be caused by asymmetric and other non-normal sampling distributions of these effects (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, Reference MacKinnon, Lockwood and Williams2004). The results indicate that the CI for the indirect effect of workplace incivility on depersonalization towards co-workers through job-related anxiety does not include 0 [.038, .126], in further support of the presence of mediation.

Third, to test the individual moderating effects postulated in Hypotheses 4 and 5, we assess the workplace incivility × gender and workplace incivility × education interaction terms in Models 2 and 3, respectively. Both interaction terms are significant (β = .356, p < .001, and β = .136, p < .05). To clarify these interactions, in Figure 2 we plot the effects of workplace incivility on job-related anxiety for male and female employees (panel a) and at high and low education levels (panel b), together with simple slope analyses (Aiken & West, Reference Aiken and West1991). Consistent with Hypothesis 4, the relationship between workplace incivility and job-related anxiety is positive and significant for men (β = .468, p < .001) but not significant for women (β = −.244, ns). Similarly, the positive relationship between workplace incivility and job-related anxiety is significant at high education levels (β = .302, p < .001) but not at low levels (β = .030, ns), as predicted by Hypothesis 5.

Figure 2. Moderating effects on the relationship between workplace incivility and job-related anxiety: (a) gender and (b) education

Finally, to test for the moderated mediation effect proposed in Hypothesis 6, we applied Preacher, Rucker, and Hayes's (Reference Preacher, Rucker and Hayes2007) procedure. The logic of moderated mediation implies that the indirect effect of workplace incivility on depersonalization towards co-workers through job-related anxiety differs at different levels of the moderatorFootnote 4. Similar to the bootstrapping procedure we used to test for mediation, this procedure produces CIs rather than point estimates for the conditional indirect effects (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, Reference MacKinnon, Lockwood and Williams2004). Consistent with expectations, we find that the bootstrap 95% CI for the indirect effect of workplace incivility does not include 0 for men [.060, .165] but does include 0 for women [−.132, .021]. Similarly, the bootstrap 95% CI of the conditional effect of workplace incivility does not include 0 at high education levels [.060, .182] but does at low levels [−.024, .079], so the role of job-related anxiety in connecting workplace incivility to enhanced depersonalization towards co-workers is more prominent among male employees (Hypothesis 6a) and more educated employees (Hypothesis 6b).

Discussion

Discussion of findings

With this study, we have drawn from COR theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989) to propose that (1) depersonalization towards co-workers, as a response to workplace incivility, occurs because employees grow anxious about their job situation, and (2) their gender (i.e., being male) and education can activate this process, because these individual characteristics intensify the loss in dignity that employees experience in this negative work situation. Our results confirm these theoretical predictions.

First, the findings offer support for the proposed mediating effect of job-related anxiety: Employees' exposure to disrespectful treatments influences their use of depersonalization, due to their feelings of job-related anxiety. That is, exposure to workplace incivility spurs depersonalization because employees feel stressed by their job situation. This mediating effect, explicated in Hypothesis 3, reflects the logic of COR theory and captures two critical constitutive relationships: between work incivility and job-related anxiety (Hypothesis 1) and between job-related anxiety and depersonalization (Hypothesis 2). To the extent that employees' resource reservoirs are depleted because of disrespectful co-worker treatment, they doubt their ability to meet their job obligations (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001; Sliter, Sliter, & Jex, Reference Sliter, Sliter and Jex2012; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Bedeian, Cole and Zhang2017), which fuels their anxiety levels, as manifest in worries about the quality of their organizational functioning and fit with their organization (Schilpzand, Leavitt, & Lim, Reference Schilpzand, Leavitt and Lim2016). Furthermore, feelings of job-related anxiety lead employees to conserve their energy resources, such that they become less likely to go out of their way to contribute to the well-being of other members (Hobfoll & Shirom, Reference Hobfoll, Shirom and Golembiewski2000; Netemeyer, Maxham, & Pullig, Reference Netemeyer, Maxham and Pullig2005). A key insight of this study is that job-related anxiety is a critical mechanism by which workplace incivility causes employees to withdraw from their immediate work environment and dehumanize co-workers.

Second, the results indicate that the positive relationship between exposure to workplace incivility and job-related anxiety is stronger among employees who are male or possess higher educational levels (Hypotheses 4 and 5). In specifying these moderating effects, we apply the previously theorized but rarely examined logic of negative resource spirals (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001, Reference Hobfoll2011). The loss in personal dignity caused by exposure to workplace incivility combines with two personal factors that make employees particularly sensitive to such loss, such that the escalation of disrespectful treatments into enhanced job-related anxiety becomes more salient among male and higher-educated employees. This finding of negative resource spirals aligns with previous research that indicates a reinforcing, harmful effect of different resource-draining work context conditions (e.g., informational unfairness and organizational politics) on the generation of positive work outcomes (De Clercq, Haq, & Azeem, Reference De Clercq, Haq and Azeem2018); it also extends such research by revealing the interplay of a contextual factor (workplace incivility) with two personal characteristics.

Third, the invigorating effects of gender and education likely might be especially relevant in the cultural context of this study. Pakistani society is marked by expectations of a dominant role for men (Ali & Syed, Reference Ali and Syed2017; Strachan, Adikaram, & Kailasapathy, Reference Strachan, Adikaram and Kailasapathy2015), so male employees might perceive disrespectful treatments as particularly offensive (Mesch et al., Reference Mesch, Brown, Moore and Hayat2011; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Bedeian, Cole and Zhang2017) and react more negatively, in the form of greater job-related anxiety. Similarly, in a stratified country such as Pakistan, the status derived from education credentials suggests that well-educated employees might experience uncivil treatments as particularly stressful and contrary to their expectations (Buchmann & Hannum, Reference Buchmann and Hannum2001; Memon, Reference Memon2006), so they become particularly distressed when they suffer such treatment (Porath, Overbeck, & Pearson, Reference Porath, Overbeck and Pearson2008). Notably, these moderating roles of gender and education are particularly insightful in combination with the mediating role of job-related feelings of anxiety. That is, the moderated mediation results (Hypotheses 6a and b) support the prediction that job-related anxiety links workplace incivility more powerfully to enhanced depersonalization towards co-workers among employees who are male and more educated.

Theoretical and practical contributions

Overall, this study is insightful for management scholarship, in that it provides a more thorough understanding of why and when exposure to workplace incivility can escalate into the development of dehumanized perceptions of other organizational members. It extends previous research that specifies direct relationships of workplace incivility with psychological distress (e.g., Abubakar, Reference Abubakar2018) or job burnout in general (e.g., Rahim & Cosby, Reference Rahim and Cosby2016), by revealing how employees' worries about their organizational functioning (i.e., job-related anxiety) function to connect this source of workplace adversity to an enhanced development of dehumanized perceptions towards co-workers. Furthermore, we complement previous research on the mitigating effects of adequate skills (e.g., self-efficacy; Fida, Spence Laschinger, & Leiter, Reference Fida, Spence Laschinger and Leiter2018) or support mechanisms (e.g., co-worker support; Geldart et al., Reference Geldart, Langlois, Shannon, Cortina, Griffith and Haines2018) on employees' negative reactions to workplace incivility, by showing how employees' gender and education can invigorate this process. Employees' anxiety about their job situation offers an important and underexplored explanation for why exposure to uncivil behaviours prompts employees to dehumanize co-workers, but the strength of this explanatory mechanism increases with personal characteristics that exacerbate the affront or dignity loss that arises from this exposure.

This study also offers practical insights for organizations. The negative feelings that come with workplace incivility can be detrimental and lead to unnecessary stress and depersonalization towards co-workers, so organizations should identify strategies to diminish its occurrence. For example, they could allocate resources to initiatives that show employees how to identify mistreatments of themselves or other organizational members (Ackroyd & Thompson, Reference Ackroyd and Thompson1999). Such efforts might enhance awareness of the harmful outcomes of workplace incivility for individual employees and the organization in general, such as when this source of adversity generates destructive retaliation in the form of even more aggressive behaviours by the victims of the incivility (Beattie & Griffin, Reference Beattie and Griffin2014). Moreover, organizations should acknowledge that certain employees, due to their personal characteristics, might be more easily offended than others by uncivil treatments.

Notably, the finding that male and well-educated employees in Pakistan are more likely to exhibit depersonalization towards co-workers in response to workplace incivility – and the associated argument that they do so because these employees are more likely to be offended by rude treatments – has important implications that go beyond the specific study context. For example, male-dominated cultures mark many countries (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001) and also might manifest forcefully at lower levels of analysis, such as in certain industries (e.g., finance), professions (e.g., engineers), or work areas (e.g., manufacturing). Furthermore, the theoretical logic underpinning this study, even if not empirically tested, suggests that in female-oriented cultures, female employees might experience greater affront, compared with their male counterparts, when they are victims of workplace incivility (Cortina et al., Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Leskinen, Huerta and Magley2013) and react in particularly negative ways. More generally, any organizational measure to reduce workplace incivility seemingly should have particularly great value when that effort aligns with gender-related expectations about how people should be treated, which permeate countries, industries, professions, and work domains. Ultimately, such alignment may diminish the chances that employees avoid maintaining dedicated interpersonal relationships and exhibit depersonalization towards their colleagues.

In a related vein, the invigorating effect of education on the relationship between workplace incivility and depersonalization, through job-related anxiety, might be particularly relevant in cultures that associate high prestige with educational credentials. Yet it also is helpful for understanding the different ways employees within countries might respond to rude or offensive treatment. On the one hand, increasing educational levels suggest that employees are more aware of their rights and regard rude or disrespectful behaviours as unacceptable (Welzel, Reference Welzel2013). On the other hand, as in the case of gender, industries or professions that rely on highly educated employees (e.g., universities, hospitals) might be particularly prone to the risk that their employees are offended by incivility in the workplace (e.g., Koon & Pun, Reference Koon and Pun2018; Reiger & Lane, Reference Reiger and Lane2009). Notably, higher education institutions themselves can have an instrumental role in this regard, to the extent that they provide students and potential future victims of workplace incivility with appropriate tools to identify, report, and avoid rude behaviours in the workplace, as well as help them establish effective coping strategies so that they can build immunity to these behaviours (Welbourne, Gangadharan, & Esparza, Reference Welbourne, Gangadharan and Esparza2016).

The finding that certain groups in society (i.e., women and less-educated employees) are affected to a lesser extent by workplace incivility also has important implications. These groups – in certain countries, industries, or professions – might find workplace incivility more acceptable and believe that they do not have the ‘right’ to use their frustration as a reason to become anxious about their job situation or dehumanize other organizational members (Loi, Loh, & Hine, Reference Loi, Loh and Hine2015). This tempered approach might have negative consequences in the long term though, to the extent that their frustration keeps growing under the surface and then eventually erupts in the form of overtly aggressive responses. If employees do not appear negatively affected by workplace incivility but actually hide their frustration, it is of paramount importance that organizational leaders establish internal cultures that name rude and demeaning behaviours for what they are and search for organization-level solutions to eradicate the offensive behaviours (Pearson & Porath, Reference Pearson and Porath2005).

Finally, female and less-educated employees might be less likely to react to exposures to workplace incivility with enhanced job-related anxiety and subsequent depersonalization because the negative treatment that they receive is more subtle than can be captured by the generic scale of workplace incivility, as used herein and in other studies (Cortina et al., Reference Cortina, Magley, Williams and Langhout2001; Taylor, Bedeian, & Kluemper, Reference Taylor, Bedeian and Kluemper2012). For example, instigators of the incivility might purposefully exploit the specific vulnerabilities of certain employees or manipulate the situation, such that their rudeness or discrimination is covert, masked by appearances of appropriate conduct, to the extent that it even might go unnoticed by the victims. Organizational decision makers and scholars therefore should clarify and recognize the different interpretations that various employees might develop in response to treatments they receive in the workplace, and then use targeted approaches to diminish the likelihood that truly offensive, rude behaviours affect different groups of employees negatively. Such targeted efforts might involve formal training programmes organized outside the workplace, formal on-the-job training initiatives, or informal learning, all of which represent valuable sources of employee development that also can diminish the negative consequences of incivility in the workplace (Enos, Kehrhahn, & Bell, Reference Enos, Kehrhahn and Bell2003; Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2003).

Limitations and future research

This study has some limitations, whose consideration offers opportunities for further research. First, we did not directly capture the theorized mechanisms that we use to link employees' suffering from workplace incivility with job-related anxiety and their subsequent depersonalization towards co-workers, namely, their sense of dignity loss and associated diminished ability and motivation to care for the well-being of others. In a similar vein, we argued that the invigorating roles of being male and more educated for translating workplace incivility into depersonalization, through job-related anxiety, could be explained by the enhanced affront or offense that these employees experience when they are victims of disrespectful treatments. Follow-up studies could measure these mechanisms explicitly. Second, continued research could investigate other contingency factors that invigorate the indirect relationship between workplace incivility and depersonalization towards co-workers, through job-related anxiety, such as employees' neuroticism (Gunthert, Cohen, & Armeli, Reference Gunthert, Cohen and Armeli1999), risk aversion (Vandenberghe, Panaccio, & Ayed, Reference Vandenberghe, Panaccio and Ayed2011), or limited confidence in their work-related abilities (Bandura, Reference Bandura1997). Third, our empirical focus is on one country, Pakistan, which might limit the generalizability of the findings. Cross-national comparisons could provide deeper insights into the relative importance of job-related anxiety as a mediator of the link between workplace incivility and depersonalization towards co-workers, as well as reveal how various moderators work differently in settings marked by distinct cultural and institutional characteristics (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001). Moreover, it would be useful to determine how personal characteristics inform the extent to which exposure to workplace incivility escalates into enhanced job-related anxiety and subsequent depersonalization across different industries, professions, and work domains.