Introduction

Employability has become a topic of interest due to changes in the broader economy and adverse employment conditions, which made employees more vulnerable and exposed to employment uncertainty (Clarke, Reference Clarke2008; Fugate, Kinicki, & Ashforth, Reference Fugate, Kinicki and Ashforth2004; Rothwell & Arnold, Reference Rothwell and Arnold2007; Van der Heijden, Reference Van der Heijden2002; Vanhercke, De Cuyper, Peeters, & De Witte, Reference Vanhercke, De Cuyper, Peeters and De Witte2014). Employability is defined as ‘the ability to keep the job one has or to get the job one desires’ (Rothwell & Arnold, Reference Rothwell and Arnold2007: 25). This definition is portrayed as a form of optimal use of employee personal competences, which are developed to address the challenges of the labor market, through ‘boundaryless’ (Arthur & Rousseau, Reference Arthur and Rousseau1996; Sullivan & Arthur, Reference Sullivan and Arthur2006) or ‘protean’ (Hall, Reference Hall2004) career development. This shift demands that employees, to a greater extent than before, be responsible for their own career development, adapt to changes, such as technological advances and globalization trends (Fugate, Kinicki, & Ashforth, Reference Fugate, Kinicki and Ashforth2004; Savickas, Reference Savickas, Brown and Lent2005) and commit to lifetime employability rather than lifetime employment within one organization (Bloch & Bates, Reference Bloch and Bates1995; Forrier & Sels, Reference Forrier and Sels2003; Froehlich, Beausaert, Segers, & Gerken, Reference Froehlich, Beausaert, Segers and Gerken2014).

Furthermore, perceptions of less job security enhance flexibility and trigger highly mobile behavior of employees (Grame, Staines, & Pate, Reference Grame, Staines and Pate1998). Organizations thus need to address the ‘employability paradox’ (Nelissen, Forrier, & Verbruggen, Reference Nelissen, Forrier and Verbruggen2017) that investment into the workforce aimed at performance enhancement and development of organizational capabilities (Van der Heijde & Van der Heijden, Reference Van der Heijde and Van der Heijden2006) may put returns at risk due to employees who are less committed to one organization (De Grip, Van Loo, & Sanders, Reference De Grip, Van Loo and Sanders2004) and possible increased staff turnover (Benson, Reference Benson2006).

As the empirical research on employability and turnover intention remains limited and a few recent studies conducted in this domain have shown mixed results (Acikgoz, Sumer, & Sumer, Reference Acikgoz, Sumer and Sumer2016; Benson, Reference Benson2006; De Cuyper, Mauno, Kinnunen, & Mäkikangas, Reference De Cuyper, Mauno, Kinnunen and Mäkikangas2011a; De Cuyper, Van der Heijden, & De Witte, Reference De Cuyper, Van der Heijden and De Witte2011b; Lu, Sun, & Du, Reference Lu, Sun and Du2016; Rahman, Naqvi, & Ramay, Reference Rahman, Naqvi and Ramay2008) we followed De Cuyper and De Witte (Reference De Cuyper and De Witte2011) to introduce two dimensions to employability: internal and external, both of which differ in scope and in focus of opportunities (De Vos, Forrier, Van der Heijden, & De Cuyper, Reference De Vos, Forrier, Van der Heijden and De Cuyper2017). Furthermore, this study advances previous research and responds to a recommendation by De Cuyper et al. (Reference De Cuyper, Mauno, Kinnunen and Mäkikangas2011a) to account for possible moderators in the indirect employability–turnover relationship through the introduction of perceived organization support and career orientation as possible moderating factors that might explain this complex relationship. Inspired theoretically by social exchange theory (Blau, Reference Blau1964; Rousseau, Reference Rousseau1995), the aim of this study is to further examine ‘employability paradox’ and answer two specific research questions: (1) Does employability (internal and external) affect employee turnover? (2) How do perceived organizational support (POS) and career orientation interact with employability (internal and external) in influencing employee turnover?

China provides an appropriate context to conduct this research as although the country has shown relatively strong economic growth over the decades, the abolition of ‘iron rice bowl’ policy, which historically guaranteed lifetime employment for employees, triggered changes in employer–employee relationships (Tsui, Wang, & Xin, Reference Tsui, Wang and Xin2006; Zhang & Morris, Reference Zhang and Morris2014) and led to more frequent employee voluntary turnover in Chinese organizations (Ding, Goodall, & Warner, Reference Ding, Goodall and Warner2000; Liu, Huang, Wang, & Liu, Reference Liu, Huang, Wang and Liu2019). As reported in recent studies (He, Lai, & Lu, Reference He, Lai and Lu2011; Newman, Thanacoody, & Hui, Reference Newman, Thanacoody and Hui2011), compared with other Asian countries, China has experienced a high employee turnover rate averaging 19.7% across industries (Aon Hewitt, 2017).

We aimed therefore to develop a conceptual model to examine the impact of employability on turnover intention by differentiating internal and external employability, and considering the possible moderating roles of POS and career orientation. The data were collected by means of a two-wave survey with a sample of 411 employees from six cities in China's Yangtze River Delta Region. The study provided a useful distinction between internal and external employability and demonstrated that the effect of these two forms of employability taken together was different from the effect of either. From an applied perspective, the findings could be of use to employers, as it was demonstrated that POS makes a difference to the turnover of employees with external employability and the latter would not show turnover intention unless they have a disengaged type of carrier orientation.

Literature Review

Relationship between employability and turnover intention

For decades employee development remained one of the most important human resources initiatives in organizations, given the intent of the latter to have high-performing, dedicated and flexible employees, which form a source of sustained competitive advantage (Nelissen, Forrier, & Verbruggen, Reference Nelissen, Forrier and Verbruggen2017; Van der Heijde & Van der Heijden, Reference Van der Heijde and Van der Heijden2006). Given significant changes in the labor market worldwide, such as deteriorating job security, skill obsolescence and widespread organizational downsizing accelerated by rapid technological advancements, the relationship between employers and employees shifted the responsibility to develop a career from the former to the latter (Clarke & Patrickson, Reference Clarke and Patrickson2008).

Employees become more concerned about their own employability, which is defined by Rothwell and Arnold (Reference Rothwell and Arnold2007) as the ability to retain the job with their current employer (i.e., internal) or seize opportunities in the external labor market and thereby nurture boundaryless career development (Sullivan & Arthur, Reference Sullivan and Arthur2006). Although not yet extensively studied by researchers (De Vos et al., Reference De Vos, Forrier, Van der Heijden and De Cuyper2017), the widespread belief among practitioners indicates that organizations may face an ‘employability’ paradox (De Cuyper & De Witte, Reference De Cuyper and De Witte2011; Nelissen, Forrier, & Verbruggen, Reference Nelissen, Forrier and Verbruggen2017). Employers driven by the need to have employees with high occupational expertise may face a dilemma when organizational investment into employee development (i.e., employability) may not yield returns due to the risk of losing them to competing organizations. As mixed evidence was presented regarding the relationship between employees' employability and their turnover intention (Acikgoz, Sumer, & Sumer, Reference Acikgoz, Sumer and Sumer2016; Benson, Reference Benson2006; De Cuyper et al., Reference De Cuyper, Mauno, Kinnunen and Mäkikangas2011a; De Cuyper, Van der Heijden, & De Witte, Reference De Cuyper, Van der Heijden and De Witte2011b; Lu, Sun, & Du, Reference Lu, Sun and Du2016; Rahman, Naqvi, & Ramay, Reference Rahman, Naqvi and Ramay2008) and following De Cuyper and De Witte (Reference De Cuyper and De Witte2011), we introduced two dimensions to employability: internal and external, both of which differ in scope and in focus of opportunities (De Vos et al., Reference De Vos, Forrier, Van der Heijden and De Cuyper2017). This reasoning is underpinned by social exchange theory.

Social exchange theory (Blau, Reference Blau1964; Rousseau, Reference Rousseau1995) conceptualizes reciprocal relationships between two agents within organizations (employer and employee) in such a way that two-sided rewarding interaction is based upon the norms of trust, kindness and respect. Employer investments into employees' development are returned in the form of enhanced capabilities, expertise and willingness to perform the tasks, subsequently leading to the disclosure of a wider range of career development opportunities by employees as well as their confidence for the development internally. The scope of opportunities for employees is, therefore, narrowed down by the perception of being valuable, resourceful and able to realize career goals with a current employer (Benson, Finegold, & Mohrman, Reference Benson, Finegold and Mohrman2004; Nauta, Van Vianen, Van der Heijden, Van Dam, & Willemsen, Reference Nauta, Van Vianen, Van der Heijden, Van Dam and Willemsen2009). Therefore, employees with a high level of internal employability incline toward risk aversion, vigilant behavior to ensure safety, nonlosses and thus advancement of their career success internally (De Cuyper & De Witte, Reference De Cuyper and De Witte2011; Kammeyer-Mueller, Wanberg, Glomb, & Ahlburg, Reference Kammeyer-Mueller, Wanberg, Glomb and Ahlburg2005; Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski, & Erez, Reference Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski and Erez2001).

Accordingly, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1a Employees' internal employability negatively influences their turnover intention.

Considered as alternative to internal career development path, external employability is embedded in boundaryless career concept (Sullivan & Arthur, Reference Sullivan and Arthur2006), which is based on employee commitment to lifetime employability rather than lifetime employment within one organization (Bloch & Bates, Reference Bloch and Bates1995; Forrier & Sels, Reference Forrier and Sels2003; Froehlich et al., Reference Froehlich, Beausaert, Segers and Gerken2014). Employees with a high level of external employability do believe that career development opportunities are there to be seized and attained (De Vos et al., Reference De Vos, Forrier, Van der Heijden and De Cuyper2017) without obligation to reciprocate through organizational commitment (De Cuyper & De Witte, Reference De Cuyper and De Witte2011). Such employees are driven by individual aspirations and task accomplishments with maximum positive outcomes. They commit themselves to the organization through affective attachment, which contrasts with normative or continuance commitment (Allen & Meyer, Reference Allen and Meyer1990), thus employees with higher external employability are more confident about career development opportunities outside their organization (De Cuyper & De Witte, Reference De Cuyper and De Witte2011).

Accordingly, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1b Employees' external employability positively influences their turnover intention.

Moderating effect of perceived organizational support

Given mixed evidence provided by previous studies regarding the relationship between employees' employability and their turnover intention, and as a response to a recommendation by De Cuyper et al. (Reference De Cuyper, Mauno, Kinnunen and Mäkikangas2011a) to account for possible moderators in the indirect employability–turnover relationship, we introduce perceived organization support as possible moderating factor that might explain this complex relationship. Given the substantial exchange of tangible and intangible resources within an organization (Newman, Thanacoody, & Hui, Reference Newman, Thanacoody and Hui2012), employer–employee relationships are underpinned by the tenets of social exchange theory (Blau, Reference Blau1964), which shows the existence of reciprocal and implicit obligations as well as trust between the employee and the organization to enable the former to contribute to the development of organization in return for benefits from the latter (Rousseau, Reference Rousseau1995). Such relationships are underpinned by moral norms and it has been widely studied through the lens of POS, which is defined as employees' ‘global beliefs concerning the extent to which the organization values their contribution and cares about their well-being’ (Eisenberger, Huntington, & Sowa, Reference Eisenberger, Huntington and Sowa1986: 501). Although prior studies identified a variety of positive consequences of POS at work, such as affective commitment (Liu, Reference Liu2009), job satisfaction (Cao, Hirschi, & Deller, Reference Cao, Hirschi and Deller2014; Riggle, Edmondson, & Hansen, Reference Riggle, Edmondson and Hansen2009), psychological well-being (Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart, & Adis, Reference Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart and Adis2017), knowledge sharing and employee communication (Erdogan, Kraimer, & Liden, Reference Erdogan, Kraimer and Liden2004; Jeung, Yoon, & Choi, Reference Jeung, Yoon and Choi2017), organizational citizenship behavior (Rhoades & Eisenberger, Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002), we believe that its impact on employee turnover is the critical one. POS was chosen by us as a possible moderator in the employability–turnover relationship because a number of prior studies (Allen, Shore, & Griffeth, Reference Allen, Shore and Griffeth2003; Haar, de Fluiter, & Brougham, Reference Haar, de Fluiter and Brougham2016; Maertz, Griffeth, Campbell, & Allen, Reference Maertz, Griffeth, Campbell and Allen2007; Rhoades, Eisenberger, & Armeli, Reference Rhoades, Eisenberger and Armeli2001) identified the negative relationship between POS and turnover intention. Retaining employees appears to be among the priorities for many organizations (Hom, Lee, Shaw, & Hausknecht, Reference Hom, Lee, Shaw and Hausknecht2017; Koster, De Grip, & Fouarge, Reference Koster, De Grip and Fouarge2011; Lee & Bruvold, Reference Lee and Bruvold2003) and the latter strive to control and mitigate the manifestation of such organizational withdrawal through employee employability enhancement initiatives to invoke organizational commitment and continued participation (Maertz et al., Reference Maertz, Griffeth, Campbell and Allen2007; Mathieu, Fabi, Lacoursière, & Raymond, Reference Mathieu, Fabi, Lacoursière and Raymond2016). We expect therefore employees possessing internal employability to respond to a high level of POS by a low intention to withdraw from the organization.

Accordingly, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2a POS moderates the negative relationship between employees' internal employability and turnover intention such that the relationship becomes stronger for employees perceiving a high level of POS.

It is anticipated that the level of reciprocity is lower for employees with high external employability as they are committed to their organizations in an autonomous way through affective commitment, promotion orientation career path, intrinsic motivation and directed toward achieving positive outcomes by pursuing ideal goals, personal growth and advancement (Johnson, Chang, & Yang, Reference Johnson, Chang and Yang2010; Markovits, Ullrich, van Dick, & Davis, Reference Markovits, Ullrich, van Dick and Davis2008). Turnover intention of promotion-oriented employees with external employability therefore can be reduced through the support from the organization to allow the former to grow and aspire within the organization (Andrews, Kacmar, & Kacmar, Reference Andrews, Kacmar and Kacmar2014) and develop a positive emotional bond with the organization (Rhoades & Eisenberger, Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002). Supporting and promoting employee development initiatives, such as training, salary increases and promotions would encourage such employees to adopt an organizational membership, lead to greater inducements and belief in the reciprocity norms in organizations and reduce employee turnover (Allen, Shore, & Griffeth, Reference Allen, Shore and Griffeth2003; Koster, De Grip, & Fouarge, Reference Koster, De Grip and Fouarge2011; Maertz et al., Reference Maertz, Griffeth, Campbell and Allen2007).

Accordingly, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2b POS moderates the positive relationship between employees' external employability and turnover intention such that the relationship becomes weaker for employees perceiving a high level of POS.

Moderating effect of career orientation

Given employees' exposure to widespread career uncertainty and the necessity of taking greater control over their own career management to remain employable in a highly competitive labor market (Callanan, Perri, & Tomkowicz, Reference Callanan, Perri and Tomkowicz2017; Direnzo, Greenhaus, & Weer, Reference Direnzo, Greenhaus and Weer2015), we argue that career orientation should be considered as another potential moderator in the employability–turnover relationship. Career is perceived differently by employees and its orientation is comprised of ‘attitudes expressed by superordinate intentions of an individual that will influence career-related decisions’ (Gerber, Wittekind, Grote, & Staffelbach, Reference Gerber, Wittekind, Grote and Staffelbach2009b: 304). Studies by Tschopp, Grote, and Gerber (Reference Tschopp, Grote and Gerber2014) and Gerber, Grote, Geiser, and Raeder (Reference Gerber, Grote, Geiser and Raeder2012) showed that employees act differently when faced with external job opportunities and the response is dependent on their career orientation, which according to Gerpott, Domsch, and Keller (Reference Gerpott, Domsch and Keller1988) reflects employees' personal values and attitudes toward the career.

The concept of traditional career orientation (Guest & Conway, Reference Guest and Conway2004) assuming employees consider job security and loyalty to their organizations crucial and aim to develop vertically within one organization was split up into two types: traditional/promotion oriented and traditional/loyalty oriented (Arthur & Rousseau, Reference Arthur and Rousseau1996; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Wittekind, Grote and Staffelbach2009b). Both of these orientations are based on long-term tenure with an employer and the norms of reciprocity, which are underpinned by social exchange theory (Blau, Reference Blau1964). Employees with the traditional/promotion orientation are eager to achieve career success by climbing up the hierarchical ladder, whereas traditional/loyalty-oriented ones demand the provision of job security and long-term commitment in the form of employment within the organization (Tschopp, Grote, & Gerber, Reference Tschopp, Grote and Gerber2014).

Given further manifestation of the ‘boundaryless career’ development approach (Arthur & Rousseau, Reference Arthur and Rousseau1996), more recently emerged independent career orientation is inclined toward employment mobility shaped by sets of multiple and coexisting boundaries (Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Wittekind, Grote and Staffelbach2009b; Rodrigues & Guest, Reference Rodrigues and Guest2010). Employees with independent career orientation value the self-management of their careers and possess active as well as positive attitudes toward frequent changes of organizations and display loyalty to themselves rather than to their organizations (Guest & Conway, Reference Guest and Conway2004; Tschopp, Grote, & Gerber, Reference Tschopp, Grote and Gerber2014).

Disengaged career orientation means that employees consider personal life to be more crucial than their career and strive to maintain work–life balance, may occasionally be work-centered and thus their disengagement mainly refers to limited commitment to vertical career advancement, rather than to work itself (Tschopp, Grote, & Gerber, Reference Tschopp, Grote and Gerber2014).

Earlier studies such as Guest and Conway (Reference Guest and Conway2004), Gerber, Wittekind, Grote, Conway, and Guest (Reference Gerber, Wittekind, Grote, Conway and Guest2009a) and Gerber et al. (Reference Gerber, Wittekind, Grote and Staffelbach2009b) showed that employees with independent career orientation exhibited the highest intention to leave, followed by those with disengaged career orientation and then by those with traditional career orientation (promotion and loyalty). Therefore, we believe that the relationship between employability and turnover intention may be moderated by four career orientation categories: traditional/promotion, independent, traditional/loyalty and disengaged.

Accordingly, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3a The four career orientation categories will have different moderating effects on the negative relationship between employees' internal employability and turnover intention.

Hypothesis 3b The four career orientation categories will have a different moderating effect on the positive relationship between employees' external employability and turnover intention.

Method

Sample and procedure

We collected our data from a sample of employees from six cities in China's Yangtze River Delta Region (Nanjing, Suzhou, Nantong, Changzhou, Taizhou and Yancheng). Following Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, and Podsakoff (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003) in order to prevent possible common method variance, the self-administered questionnaires were distributed in two waves both by post (return postpaid) and through emails but offered no incentives. In the first wave, demographic variables, employability and POS were measured; and in the second wave, career orientation and turnover intention were measured. The two waves were separated by 1 week. On the first page of the questionnaire, detailed instructions were provided and the participants were informed of the research purpose and assured of the anonymity of participation. Only four zip-code digits and the final four digits of the participants' cell phone numbers were required (e.g., ‘0094, 5361’).

A total of 550 pairs of questionnaires were distributed. For the first and second rounds of the survey, 512 and 486 questionnaires were returned, respectively. After pairing, 465 pairs were obtained. The return rates for the first and second rounds were 93.1% and 88.4%, respectively; the return rate for the pairing of the questionnaires from the first and second rounds was 84.5%. The questionnaire pairs that were incomplete or exhibited obviously irregular or contradictory answers were removed (54 pairs). Overall, 411 valid questionnaire pairs remained for an overall valid return rate of 74.7%. Table 1 shows the profile of the participants.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of participant profile (n = 411)

Measures

Employability

We adopted the scale for employees' self-perceived employability developed by Rothwell and Arnold (Reference Rothwell and Arnold2007). We hereafter used the term ‘overall employability’ when referring to this construct. It contains two sub-constructs: internal employability and external employability. The measurement was based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree and 5 = totally agree) comprising 10 items; among them were four items about internal employability (e.g., ‘Among the people who do the same job as me, I am well respected in this organization’) and six items about external employability (e.g., ‘The skills I have gained in my present job are transferable to other occupations outside this organization’). The value of Cronbach's α for the overall scale was .86; and the values of Cronbach's α for the internal and external employability dimensions were .84 and .84, respectively.

Perceived organizational support

We adopted the scale for measuring POS developed by Shanock and Eisenberger (Reference Shanock and Eisenberger2006), which comprised six items (e.g., ‘The organization values my contribution to its well-being’ and ‘The organization shows very little concern for me’). A 7-point Likert scale was used (1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree). The value of Cronbach's α for this scale was .79.

Career orientation

This study adopted the career orientation scale widely used in the literature (Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Wittekind, Grote and Staffelbach2009b). This scale comprised nine items and used a dichotomous forced-choice method (e.g., ‘Being employable in a range of jobs vs. having job security’ and ‘Commitment to yourself and your career vs. commitment to the organization’). The participants were required to choose based on the prospects of future careers. In accordance with the research of Guest and Conway (Reference Guest and Conway2004), the Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2007) and Latent GOLD 4 (Vermunt & Magidson, Reference Vermunt and Magidson2005) statistical software packages were employed to classify the measures into four types: traditional/promotion, traditional/loyalty, independent and disengaged career orientation.

Turnover intention

The employee turnover intention scale was adopted from Hui, Wong, and Tjosvold (Reference Hui, Wong and Tjosvold2007). This scale comprised three items (e.g., ‘It is very possible that I will look for a new job next year’). A 7-point Likert scale was used (1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree). The value of Cronbach's α was .64.

Control variables

The demographic variables were used as the control variables, including sex (1 = men and 0 = women), age (1 = below 25 years, 2 = 25–35 years, 3 = 36–45 years, 4 = 46–55 years and 5 = above 55 years), education level (1 = below senior high school, 2 = senior high school, 3 = college, 4 = Bachelor's degree, 5 = Master's degree and 6 = doctorate or above) and employment position level (1 = operational employee, 2 = first-line manager, 3 = middle manager and 4 = senior manager).

The reliability and validity of the scales used in this study have been verified previously in empirical studies. We used a translation-back-translation method to develop our questionnaire in the Chinese language. Two coworkers with high English proficiency were first invited to translate the original English scales into Chinese. Thereafter, a bilingual scholar with a PhD degree in industrial psychology and work experience in an English-speaking country was invited to back translate the Chinese scales into English. The back-translated English scales were compared with the original English scales. Inconsistencies were discussed and modified (the translation-back-translation process was repeated for considerably inconsistent parts) to produce a final version of the Chinese scales.

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis

We used χ2 value, degree of freedom (df), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) as the goodness-of-fit indices to assess the construct validity of the scales (i.e., employability, career orientation, POS, turnover intention). As shown in Table 2, the construct validity of the scales used in this study was acceptable.

Table 2. CFA results regarding questionnaire construct validity (n = 411)

Latent class analysis

Latent class analysis (LCA) is a statistical technique that integrates latent variables and categorical variables and is used to explore latent class variables hidden behind explicit class variables (Meng et al., Reference Meng, Wu, Li, Zhou, Li, Zhang and Zhao2010). In this study, LCA was performed to statistically investigate career orientation. By performing LCA, participants were classified into groups based on the degree of similarity in the way they answered a series of items. Specifically, the participants were classified into a minimal number of groups (i.e., latent class variables) to explain differences in the item-answering styles used among the participants within a group (Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Wittekind, Grote, Conway and Guest2009a).

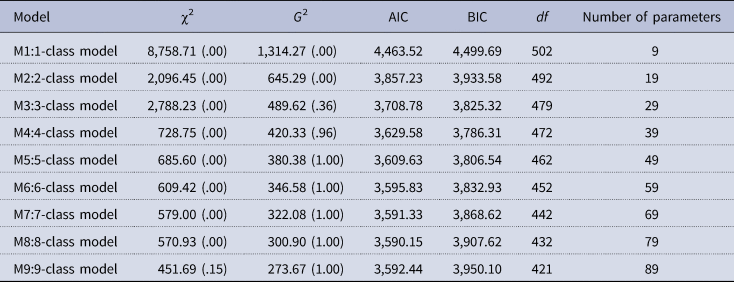

In LCA, the Pearson χ2, the likelihood ratio χ2 (G 2), the Akaike information criteria (AIC) and the Bayesian information criteria (BIC) are the main indices for model fitness. Generally, assessing goodness of fit typically begins with a single model (i.e., the number of latent classes is 1), and then the number of latent classes gradually increases. The fit between hypothetical models and observation data should be repeatedly examined to identify an optimal model (Meng et al., Reference Meng, Wu, Li, Zhou, Li, Zhang and Zhao2010). No significant χ2 and G 2, and lower AIC and BIC values indicate excellent model fitness.

As shown in Table 3, when the number of latent classes was 4, the G 2 value was not significant (G 2 = 420.33, df = 472, p = .96), and the AIC and BIC values were relatively lower, especially the latter. The χ 2, G 2, AIC values for M1–4 decreased sharply, while gradually decreasing for M4–9. Meanwhile, the p values of Vuong–Lo– Mendell–Rubin (VLMR) and adjusted Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio tests for 4 (H0) versus 5 classes were not significant (p = .19; .19). Taking these into account and in line with Gerber et al. (Reference Gerber, Wittekind, Grote and Staffelbach2009b), we adopted M4 as the optimal model.

Table 3. Summary table for the goodness-of-fit indices of the exploratory latent class model (n = 411)

After the optimal model was determined, the names of latent classes were determined. Table 4 and Figure 1 show the conditional probabilities of nine items for the four latent classes.

Figure 1. Conditional probabilities for the four latent classes. Note: f Class 1 = 63, f Class 2 = 209, f Class 3 = 85, f Class 1 = 54

Table 4. Conditional probabilities of nine items for the four latent classes (n = 411)

Note. f Class 1 = 63, f Class 2 = 209, f Class 3 = 85, f Class 1 = 54.

As shown in Table 4 and Figure 1, for Class 1, the conditional probability values on all the items where the participants chose Option 1 were very low (all below .10). For Class 2, the conditional probability values on items 2 and 4 where the participants chose Option 1 were very high (both above .60), the conditional probability values on items 1 and 7 were moderate (both between .30 and .60), while the conditional probability values on other items were very low (all below .20). For Class 3, the conditional probability values on items 1–4 where the participants chose Option 1 were very low (all below .10), while the conditional probability values on items 5–9 were very high (all above .60). For Class 4, the conditional probability values on four items (items 2, 4, 6, 7) where the participants chose Option 1 were very high (all above .60), and the conditional probability values on the other five items (items 1, 3 5, 8, 9) were moderate (all between .30 and .60).

Based on Gerber et al. (Reference Gerber, Wittekind, Grote and Staffelbach2009b), we named the four latent classes ‘traditional/promotion career orientation,’ ‘independent career orientation,’ ‘traditional/loyalty career orientation’ and ‘disengaged career orientation.’

Descriptive statistical analysis and correlation analysis

Table 5 shows the means and standard deviations (SDs) of various variables and the correlation coefficients between variables. The results indicate that the independent variables (employability, internal employability and external employability) and the moderator variables (POS and career orientation) were almost significantly correlated with the dependent variable (turnover intention).

Table 5. Descriptive statistical analysis and correlation analysis (n = 411)

Note. *Signifies p < .05, and ** signifies p < .01; Career orientation: 1 – traditional/ promotion career orientation, 2 – independent career orientation, 3 – traditional/ loyalty career orientation, 4 – disengaged career orientation.

Moderated multiple regression analysis

Moderated multiple regression analysis was performed to explore the influence of the independent variable (employees' employability) on the dependent variable (turnover intention) and to examine whether POS and career orientation exhibited moderating effects on these relationships.

Moderating effect of POS

Table 6 shows the regression analysis results regarding the moderating effect of POS on the relationship between employees' employability and turnover intention. In Model 2, only the independent variable (overall employability) was included. Its coefficient of determination (R 2) was .08, and thus accounted for 8% variance. Model 3 included the variable POS; it accounted for 15% more variance in turnover intention. Model 4 included the interaction term of employability and POS; its R 2 was .23 but explained no more variance in turnover intention. The interaction term exhibited no significant effect on turnover intention (β = .03, p > .10). In other words, POS did not significantly affect the relationship between employees' overall employability and turnover intention. However, in Model 5, the independent variables internal employability and external employability were included, the R 2 was .12 and internal employability exhibited a significant negative effect on turnover intention (β = −.16, p < .01) and external employability exhibited a significant positive effect on turnover intention (β = .26, p < .01). Therefore, Hypothesis 1a and Hypothesis 1b were supported.

Table 6. Moderating effect of POS on the relationship between employability and turnover intention (n = 411)

Note. **Signifies p < .01, *signifies p < .05 and † signifies p < .10.

Next, we turned to examine the moderating effect of POS on the relationship between employees' internal employability, external employability and turnover intention. In Model 6, the variable POS was included, its R 2 was .23 and the F value for the overall regression model was 17.00 (p < .01). In Model 7, the two interaction terms were included, R 2 was .24 and the F value for the overall regression model was 14.06 (p < .01). The interaction of external employability and POS significantly affected turnover intention (β = .11, p < .05), while the interaction of internal employability and POS only had a near significant trend to affect turnover intention (β = −.09, p < .10). Therefore, Hypothesis 2b was supported, whereas Hypothesis 2a was not supported.

Next, we conducted post hoc analyses for the two interaction effects. First, the interaction between POS and external employability on turnover intention was examined (Figure 2a). Post hoc probing indicated that at both one SD below (β = .5394, p < .01) and above (β = .8841, p < .01) the mean on POS, external employability could predict turnover intention. However, using the Johnson–Neyman technique (Johnson & Neyman, Reference Johnson and Neyman1936), the interaction was found to be insignificant at p < .05 level for any value of POS below 2.79 on this 7-point Likert scale. Next, we examined the interaction between POS and internal employability on turnover intention (Figure 2b). In post hoc analyses examining simple slopes for POS at one SD below the mean, internal employability predicted turnover intention (β = .3462, p < .01), but at one SD above the mean, only at the margin of significance (β = .4392, p = .05). Using Johnson–Neyman, the interaction was found to be insignificant at p < .05 level for any value of POS below 3.06 on this 7-point Likert scale.

Figure 2. The two-way interaction of POS and external employability (a) and internal employability (b) on turnover intention. Low designates −1 SD for the scale; high designates +1 SD for the scale

Moderating effect of career orientation

Table 7 shows the moderating effect of the four types of career orientations (Career Orientation 1–4) on the relationships between internal employability, external employability and turnover intention. In Model 4, the independent variables internal employability, external employability and moderator traditional/promotion career orientation (Career Orientation 1) were included. The R 2 was .16 and the F value for the overall regression model was 8.21 (p < .01). In addition, the interaction term of external employability and traditional/promotion career orientation exhibited a significant effect on turnover intention (β = .13, p < .05), but the interaction term of internal employability and traditional/promotion career orientation did not (β = .06, p > .10). In other words, being traditional/promotion career orientated only significantly affected the relationship between employees' external employability and turnover intention.

Table 7. Moderating effect of career orientation on the relationship between internal employability, external employability and turnover intention (n = 411)

Note. **Signifies p < .01, * signifies p < .05, and † signifies p < .10; Career orientation: 1 – traditional/ promotion career orientation, 2 – independent career orientation, 3 – traditional/ loyalty career orientation, 4 – disengaged career orientation.

Similarly, in Model 6, independent career orientation (Career Orientation 2) significantly but negatively affected both the relationship between employees' internal employability, external employability and turnover intention (β = −.33, p < .01; β = −.15, p < .01). However, in Model 8, traditional/loyalty career orientation (Career Orientation 3) only affected the relationship between employees' internal employability and turnover intention significantly positively (β = .27, p < .01), but did not affect the relationship between external employability and turnover intention. In Model 10, being disengaged career oriented (Career Orientation 4) only affected the relationship between employees' external employability and turnover intention significantly positively (β = .06, p < .05), but did not affect the relationship between internal employability and turnover intention. Therefore, both Hypothesis 3a and Hypothesis 3b were only partially supported.

Next, we conducted post hoc analyses for the five interaction effects. First, the interaction between traditional/promotion career orientation (Career Orientation 1) and external employability on turnover intention was examined (Figure 3a). In post hoc analyses examining simple slopes at one SD above the mean, external employability predicted turnover intention (β = 1.3890, p < .01), but at one SD below the mean, only close to being statistically significant to predict turnover intention (β = .2263, p = .07). Next, we examined the interaction between independent career orientation (Career Orientation 2) and internal employability as well as external employability on turnover intention. For internal employability (Figure 3b), simple slopes at one SD below (β = .4374, p < .01) and above (β = −.9942, p < .01) were both significant. For external employability (Figure 3c), simple slopes at one SD below (β = .8876, p < .01) and above (β = −.3275, p < .05) were also both significant. We also examined the interaction between traditional/loyalty career orientation (Career Orientation 3) and internal employability on turnover intention (Figure 3d). Post hoc analyses indicated that simple slopes at one SD below (β = −.3110, p < .05) and above (β = .4263, p < .01) were both significant. Finally, we examined the interaction between disengaged career orientation (Career Orientation 4) and external employability on turnover intention (Figure 3e). Post hoc analyses also indicated that simple slopes at one SD below (β = .3955, p < .01) and above (β = .9106, p < .01) were both significant.

Figure 3. The two-way interaction of career orientation and employability on turnover intention. (a) Career Orientation 1 and External Employability, (b) Career Orientation 2 and Internal Employability, (c) Career Orientation 2 and External Employability, (d) Career Orientation 3 and Internal Employability, and (e) Career Orientation 4 and External Employability. Low designates −1 SD for the scale; high designates +1 SD for the scale

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to further examine ‘employability paradox’ (De Cuyper & De Witte, Reference De Cuyper and De Witte2011; Nelissen, Forrier, & Verbruggen, Reference Nelissen, Forrier and Verbruggen2017) through probing the association between employability and employee turnover, differentiating between internal and external employability and including POS and career orientation as two possible moderators of the relationship. Although previous studies such as Acikgoz, Sumer, and Sumer (Reference Acikgoz, Sumer and Sumer2016), De Cuyper et al. (Reference De Cuyper, Mauno, Kinnunen and Mäkikangas2011a), Berntson, Näswall, and Sverke (Reference Berntson, Näswall and Sverke2010) have failed to find the direct relationship between employability and turnover intention, or provided mixed evidence (Benson, Reference Benson2006), the findings from our research show that overall employability exhibited a significant positive effect on turnover intention. Furthermore, differentiation of internal and external employability, which is widely accepted conceptually (Forrier & Sels, Reference Forrier and Sels2003; Rothwell & Arnold, Reference Rothwell and Arnold2007; Van der Heijden, Reference Van der Heijden2002; Vanhercke et al., Reference Vanhercke, De Cuyper, Peeters and De Witte2014) also led us to revealing contrasting results to the effect of overall employability. Our empirical evidence showed that employees with high internal employability tend to seek promotion with their current employer and that employees with high external employability are likely to leave their current organizations for more favorable career development elsewhere.

Another notable result of our research, which concurs with previous POS-related empirical studies (Allen, Shore, & Griffeth, Reference Allen, Shore and Griffeth2003; Loi, Hang-yue, & Foley, Reference Loi, Hang-yue and Foley2006; Newman, Thanacoody, & Hui, Reference Newman, Thanacoody and Hui2012; Wayne, Shore, & Liden, Reference Wayne, Shore and Liden1997), shows that POS significantly and negatively influenced turnover intention, indicating that employees who perceived that their organizations highly valued their contributions or interests did not easily exhibit turnover intention. By examining the interaction effect of overall employability, we found that POS did not significantly affect the relationship between employees' overall employability and turnover intention. Yet, when we look closely by examining internal and external employability as two separate constructs, the results indicate that the moderating effect of POS mainly existed between external employability and turnover intention, but it had a certain trend to moderate the relationship between internal employability and turnover intention.

Lastly, as for the moderating effect of career orientation, our study results indicated that for employees of all four career orientation types, internal employability significantly and negatively influenced turnover intention. The negative influence of internal employability on turnover intention was the most significant among employees with traditional career orientations (promotion and loyalty), followed by those employees with disengaged and independent career orientation. This may be because employees with traditional career orientation objectives tended to develop themselves within one organization, possess high internal employability conducive to their development within the current environment, and hence be unwilling to leave their organizations (Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Wittekind, Grote and Staffelbach2009b). Despite independent career orientation embracing the notion of self-management and inclination to more frequent change of employers (Tschopp, Grote, & Gerber, Reference Tschopp, Grote and Gerber2014), when employees with this type of career orientation possess high internal employability, they can competently perform their current job, but also acquire new skills and be successful in careers within their organization (Weng & McElroy, Reference Weng and McElroy2012). Similarly, high internal employability helps employees with disengaged career orientation to offset the antecedents of turnover intention such as low organizational commitment and lack of willingness to advance the career vertically through the better achievement of desired work–life balance within their current organization (Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Wittekind, Grote and Staffelbach2009b). Our results show that only those employees who are high in external employability but have disengaged career orientation tend to leave their current employer, and employees with other career orientations tend to remain loyal to their organizations despite there being external opportunities.

Implications for Management

The study has several important implications for investment in staff employability and retention, which may be of use to practitioners while addressing the concerns related to the employability paradox (De Cuyper, Van der Heijden, & De Witte, Reference De Cuyper, Van der Heijden and De Witte2011b; Nelissen, Forrier, & Verbruggen, Reference Nelissen, Forrier and Verbruggen2017) namely the tension between enhancing employees and the risk of their turnover.

First, the study shows that the link between internal employability and turnover intention helps to retain employees, while external employability has the opposite effect. Therefore, combining our results with the findings from Benson's (Reference Benson2006) study, organizations should attempt to develop internal employability by embedding on-the-job employee training into career development planning in order for employees to gain more specific rather than general skills needed for within organization promotion.

Second, the results of our study show a negative moderating effect of perceived-organizational support on the relationship between external employability and turnover intention. In other words, POS can significantly buffer the unfavorable impact of external employability on turnover intention. This highlights the importance of nurturing an employability culture within organizations (Nauta et al., Reference Nauta, Van Vianen, Van der Heijden, Van Dam and Willemsen2009) to facilitate the dialog between employees and their managers of how to best self-develop, create challenging work assignments, which will enable employees to fulfill their potential without the need to seek opportunities outside. Furthermore, having in place supportive human resources management practices to advance organizational commitment (Koslowsky, Weisberg, Yaniv, & Zaitman-Speiser, Reference Koslowsky, Weisberg, Yaniv and Zaitman-Speiser2012), such as work–life balance policies, family social activities and personal wellbeing programs, could help to retain employees who have strong external employability.

Finally, our results suggest that for employees with disengaged career orientation, external employability significantly and positively influences turnover intention, but this is not the case for independent, traditional/promotion and traditional/loyalty career orientations. Management should therefore be aware that not all employees with high external employability want to quit but only those who have disengaged career orientation are likely to consider job alternatives externally. For this group of employees, the management should be cautious about investing resources in their employability development, but may rather strengthen the links between coworkers and the organization to promote the intrinsic values and unique supportive climate unavailable elsewhere (Van den Broeck, De Cuyper, Baillien, Vanbelle, Vanhercke, & Witte, Reference Van den Broeck, De Cuyper, Baillien, Vanbelle, Vanhercke and Witte2014).

Limitations and Further Research

This study has several limitations and the findings should be interpreted cautiously. First, several participants in this study were employees in state-owned enterprises. Known as the ‘iron rice bowl’ system (Liu, Huang, Wang, & Liu, Reference Liu, Huang, Wang and Liu2019; Zhang & Morris, Reference Zhang and Morris2014), employment in these organizations is guaranteed for the lifetime but induces nonproductive behaviors and creates a sense of stability as well as loyalty to their organizations. Regardless of employability level, these employees were unlikely to leave their current organizations. We believe this phenomenon partially influenced the relationship between employees' overall employability and turnover intention. In the future, researchers should consider the homogeneity of participants and survey employees in private enterprises.

Second, this study selected only two individual factors (i.e., POS and career orientation) for the moderation test. Other factors could also influence the relationship between employability and turnover intention, such as psychological contract type, leadership style (Green, Miller, & Aarons, Reference Green, Miller and Aarons2011; Yizhong, Baranchenko, Lin, Lau, & Ma, Reference Yizhong, Baranchenko, Lin, Lau and Ma2019) and career commitment (Koslowsky et al., Reference Koslowsky, Weisberg, Yaniv and Zaitman-Speiser2012), therefore future research could investigate these additional moderating factors.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to conduct a closer examination of employee employability by differentiating the impacts of internal versus external employability on turnover intention. We tested these impacts by considering organizational support and career orientation as possible moderating factors. The results of our empirical work support the distinction of impacts of internal and external employability and the study contributes to the literature by helping to explicate the previous inconsistent findings on the relationship between employability and turnover intention.

Dr Yevhen Baranchenko is a Senior Lecturer in Strategic Management and International Business at Newcastle Business School of Northumbria University (UK). Yevhen has been engaged in research in a variety of areas including transformation leadership, employee relations and graduate employability.

Dr Xie Yizhong is an Associate Professor in Human Resources Management at the School of Economics and Management of Nanjing University of Science and Technology. He graduated from the Institute of Psychology of Chinese Academy of Sciences with a doctoral degree in industrial and organizational psychology. Later Yizhong became a postdoctoral fellow there. His research interests include employability, human resources and organizational behavior. He has published widely in these areas in top journals including the Journal of Vocational Behavior.

Dr Zhibin Lin is an Associate Professor in Marketing at Durham University Business School. He is a keen researcher whose interests cut across several disciplines such as digital marketing, transport, travel and tourism management and international business. He is a regular contributor to a number of international leading journals, such as Tourism Management, Journal of Business Research, European Journal of Marketing, Information & Management, Transportation Research Part E, Computers in Human Behavior and others.

Dr Marco Chi Keung Lau is an Associate Professor in Financial Economics at Huddersfield University. Most of his recent research has been developed in the fields of Behavioral Economics & Finance, Chinese Economy and Financial Econometrics. His research was published previously in journals such as International Review of Financial Analysis, Energy Economics, Applied Economics and China Economic Review.

Dr Jie Ma is a Senior Lecturer in Operations Management and the Program leader for the top-up BA (Hons) Business and Business with International Management degree programs. He holds a BSc (Hons) degree in computing and an MA degree in management from Durham University Business School. Jie received his PhD in operations management from Newcastle University.