Introduction

In their seminal work, Dollard and Bakker (Reference Dollard and Bakker2010) devised the concept of psychosocial safety climate (PSC) and defined it as ‘policies, practices, and procedures for the protection of worker psychological health and safety’ (p. 580). PSC denotes a climate of managerial commitment toward: (1) stress prevention among employees; (2) prioritizing employee health and safety over competing demands like production; (3) continuous upward and downward communication regarding employee health and safety; and (4) encouraging employee participation in resolving their health and safety problems (Hall, Dollard, & Coward, Reference Hall, Dollard and Coward2010; Dollard & McTernan, Reference Dollard and McTernan2011). The PSC literature, including work on Malaysian workers, has provided considerable evidence of its effectiveness in improving psychological health and positively influencing employee wellbeing (see Law, Dollard, Tuckey, & Dormann, Reference Law, Dollard, Tuckey and Dormann2011; Dollard et al., Reference Dollard, Bailey, McLinton, Richards, Wes, Anne and Stephanie2012a, Reference Dollard, Opie, Lenthall, Wakerman, Knight, Dunn and MacLeod2012b; Idris, Dollard, Coward, & Dormann, Reference Idris, Dollard, Coward and Dormann2012; Idris, Dollard, & Yulita., Reference Idris, Dollard and Yulita2014; Yulita, Idris, & Dollard, Reference Yulita, Dollard, Shimazu, Bin, Dollard and Oakman2016).

Although psychological health is vital for safety behaviors (Clarke & Cooper, Reference Clarke and Cooper2004; Mearns & Hope, Reference Mearns and Hope2005), limited research has been conducted on the role of PSC in improving workplace safety (Yulita, Idris, & Dollard, Reference Yulita, Dollard, Shimazu, Bin, Dollard and Oakman2016). In a recent and first study on the topic, Zadow, Dollard, Mclinton, Lawrence, and Tuckey (Reference Zadow, Dollard, Mclinton, Lawrence and Tuckey2017) found that PSC reduces emotional exhaustion, work injuries, and underreporting of injuries. These findings highlight the significance of PSC in improving workplace safety. Our study advances work on PSC by investigating if it improves safety behaviors (compliance and participation) by reducing psychological distress.

Safety compliance and participation are individual behaviors that ‘provide researchers with a measurable criterion which is more proximally related to psychological factors than accidents or injuries’ (Christian, Bradley, Wallace, & Burke, Reference Christian, Bradley, Wallace and Burke2009: 1104). Moreover, individuals are motivated to engage in safety behaviors when they perceive that their climate is motivating and conducive for such behaviors (Neal & Griffin, Reference Neal and Griffin2006). High-level PSC provides continuous upward and downward communication, encourages participation, and prioritizes health and safety over production demands. Thus, the perception that one's work environment is psychosocially safe should ensure management commitment to employee psychological health and safety. This is likely to positively impact safety behaviors of employees.

The argument for a PSC-safety behaviors link is significant specifically for challenging jobs and demanding industries such as the oil and gas industry (Mirza & Isha, Reference Mirza and Isha2017). Because job description plays a key role in determining psychological distress among employees (Carlisle & Parker, Reference Carlisle and Parker2014), there is a need to investigate factors that reduce psychological distress among employees in challenging jobs/industries in efforts to improve their safety behaviors. Our study focuses on Malaysian organizations for similar reasons. First, stress-related issues have been reported by workers in Malaysian organizations (Idris, Dollard, & Winefield, Reference Idris, Dollard and Winefield2010; Idris & Dollard, Reference Idris and Dollard2011). Second, the overall safety awareness and performance in Malaysian organizations is unsatisfactory (Lugah, Ganesh, Darus, Retneswari, Rosnawati, & Sujatha, Reference Lugah, Ganesh, Darus, Retneswari, Rosnawati and Sujatha2010; Kumar, Chelliah, Chelliah, Binti, & Amin, Reference Kumar, Chelliah, Chelliah, Binti and Amin2012).

The objective of this paper is to examine the effect of PSC on safety behaviors via psychological distress. We propose in line with conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989) that high-level PSC diminishes the need to invest psychological resources toward countering a threat to safety. This argument is in line with the literature that shows high-level PSC predicts workplace safety (Clarke & Cooper, Reference Clarke and Cooper2004; Siu, Kong, Phillips, & Leung, Reference Siu, Kong, Phillips and Leung2004; Zheng, Xiang, Song, & Wang, Reference Zheng, Xiang, Song and Wang2010) and significantly reduces employees' psychological distress (Dollard et al., Reference Dollard, Bailey, McLinton, Richards, Wes, Anne and Stephanie2012a, Reference Dollard, Opie, Lenthall, Wakerman, Knight, Dunn and MacLeod2012b; Idris et al., Reference Idris, Dollard, Coward and Dormann2012). A psychosocially safe climate ensures employees their safety and reduces the stress of safety concerns. Employee psychological resources preserved as a result of a diminished need to expend them toward safety concerns can be invested toward other vital behaviors such as improving safety compliance and participation.

Literature Review

Conservation of resources theory (COR)

According to the conservation of resources (COR) theory, ‘individuals strive to obtain, retain, protect, and foster those things that they value’ (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001: 341). The theory emphasizes that individuals try to preserve their resources and that resource loss or a threat of their loss is stressful (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989, Reference Hobfoll2001). COR theory has been influential in explaining numerous workplace behaviors as attempts to preserve psychological resources or as reactions to resource loss or threat. In suggesting that resource depletion produces distress, COR implies that conducive work environments like psychosocially safe climates prevent depletion and unnecessary consumption of psychological resources, enabling their use elsewhere.

Based on COR, the safety literature explains that in high-level PSC environments, workers are ‘not struggling to maintain depleted resources and are able to invest resources to protect their health and safety at work including accessing and remembering new safety information, monitoring hazards and effectively using safety materials’ (Zadow et al., Reference Zadow, Dollard, Mclinton, Lawrence and Tuckey2017: 559). High-level PSC environments are characterized by management support and commitment to employee psychological health. Employees in such environments are unlikely to perceive a threat to their psychological resources. The preserved resources are thus available for utilization toward more meaningful activities as opposed to countering stress arising from a threat to them. In a safety context, the availability of these psychological resources enables productive activities among employees like acquisition of new safety information, personal initiative to better equip themselves to cope with safety threats, vigilance and active involvement toward their own safety and safety in general.

This study does not explicitly measure employee resources but investigates if, based on COR theory, psychosocially safe climates foster positive safety behavior by reducing/eliminating psychological distress.

Psychosocial safety climate (PSC)

PSC refers to management commitment to preventing workplace stress and psychological health issues among employees (Dollard et al., Reference Dollard, Bailey, McLinton, Richards, Wes, Anne and Stephanie2012a, Reference Dollard, Opie, Lenthall, Wakerman, Knight, Dunn and MacLeod2012b). Low-quality PSC organizations expose employees to work conditions that leave them susceptible to psychosocial risks (Law et al., Reference Law, Dollard, Tuckey and Dormann2011). It can be deduced that in high-level PSC organizations, management ensures that jobs are not demanding to an extent that they affect employee psychological health. In high-level PSC environments, employee health is valued and productivity does not come at the cost of their psychological health (Hall, Dollard, & Coward, Reference Hall, Dollard and Coward2010). These organizations have favorable working conditions where management emphasis is on protecting employees from psychological health concerns. Therefore, the current study proposes that PSC will decrease psychological distress levels and by doing so, increase their safety behaviors.

Psychological distress

Psychological distress is described as ‘the unique discomforting, emotional state experienced by an individual in response to a specific stressor or demand that results in harm, either temporary or permanent, to the person’ (Ridner, Reference Ridner2004: 539). The literature highlights two main factors that contribute to psychological distress among employees. First, employee position within the hierarchy determines psychological distress as it is more prevalent in white and blue collar workers as compared with ‘senior executives, professional and middle managers’ (Durand & Marchand, Reference Durand and Marchand2005). Second, organizational factors faced by employees (Shirom, Westman, & Melamed, Reference Shirom, Westman and Melamed1999) such as demanding job designs (Carlisle & Parker, Reference Carlisle and Parker2014) and work overload cause psychological distress (Bultmann, Kant, Van Den Brandt, & Kasl, Reference Bultmann, Kant, Van Den Brandt and Kasl2002). The focus of the current study is production workers (blue collar) of oil and gas industry of Malaysia. The demanding work environment of these workers and their position within the organizational hierarchy exposes them to greater risks of psychological distress. Thus, we suggest that a psychosocially safe climate will be helpful in reducing psychological distress, resulting in improved safety behaviors.

Safety compliance

Safety compliance is defined as ‘the extent to which employees adhere to safety procedures and carry out work in a safe manner’ (Neal, Griffin, & Hart, Reference Neal, Griffin and Hart2000). Safety compliance includes activities essential for workplace safety such as following standard operating procedures and appropriate use of personal protective equipment (Neal & Griffin, Reference Neal and Griffin2006). Studies have shown that safety compliance is a function of safety knowledge and motivation (Neal, Griffin, & Hart, Reference Neal, Griffin and Hart2000). It implies that safety compliance results from a motivation to comply with safety regulations and from knowledge about safety procedures. We suggest that employees can be motivated to comply with safety regulations by improving the PSC environment that reduces their psychological distress, freeing up psychological resources to be invested toward crucial safety behaviors.

Safety participation

Safety participation is defined as ‘behaviors that do not directly contribute to an individual's personal safety but that do help to develop an environment that supports safety’ (Neal & Griffin, Reference Neal and Griffin2006: 947). These behaviors include voluntary participation in safety activities, helpful behavior toward co-workers regarding workplace safety, regular attendance in safety meetings, and educating others about workplace safety (Neal & Griffin, Reference Neal and Griffin2002). Safety participation also stems from safety knowledge and motivation (Neal, Griffin, & Hart, Reference Neal, Griffin and Hart2000). We suggest that employees who are not psychologically distressed from safety concerns in a high-PSC environment are in better positions to actively participate in safety activities, absorb new safety information, and help their co-workers in combating potential safety threats.

Hypotheses development

Psychosocial safety climate and psychological distress

The key distinction between safety climate and PSC is that the former specifically focuses on reducing/eliminating physical threat to employees (Zohar, Reference Zohar2010; Mirza & Isha, Reference Mirza and Isha2018) while the latter deals with preventing psychosocial hazards faced by employees (Hall, Dollard, & Coward, Reference Hall, Dollard and Coward2010). PSC in the organization is indicative of a climate which enables employees to cope with work demands and provides healthy working conditions (Yulita, Idris, & Dollard, Reference Yulita Idris, Dollard, Shimazu, Bin, Dollard and Oakman2014). In other words, PSC is an indication of management commitment to employee psychological health which is evident in standardized safety-specific procedures and an emphasis on the importance of safety. Therefore, employees in high-PSC environments have the least amount of psychological health problems (Yulita, Idris, & Dollard, Reference Yulita, Dollard, Shimazu, Bin, Dollard and Oakman2016).

PSC is crucial to workers' psychological health. In one of the earliest studies in the domain, Dollard and Bakker (Reference Dollard and Bakker2010) reported a negative relationship between PSC and psychological distress. In another study, Dollard, Tuckey, and Dormann (Reference Dollard, Tuckey and Dormann2012) found that PSC moderates the job demand–resource relationship with psychological distress. Other studies have reported that PSC decreases employee psychological distress (Hall, Dollard, & Coward, Reference Hall, Dollard and Coward2010; Law et al., Reference Law, Dollard, Tuckey and Dormann2011; Dollard et al., Reference Dollard, Bailey, McLinton, Richards, Wes, Anne and Stephanie2012a, Reference Dollard, Opie, Lenthall, Wakerman, Knight, Dunn and MacLeod2012b). It was also found to be more strongly related to psychological distress than any other climate measure (Idris et al., Reference Idris, Dollard, Coward and Dormann2012). A recent review on PSC (Yulita, Idris, & Dollard, Reference Yulita, Dollard, Shimazu, Bin, Dollard and Oakman2016) also reported a strong negative association between PSC and psychological distress. Based on this empirical evidence, we propose that even within a stressful work environment like the oil and gas sector, high-level PSC reduces psychological distress among employees. Thus, we propose that:

Hypothesis 1

Psychosocial safety climate will be negatively associated with psychological distress.

Psychological distress and safety behaviors

Psychological distress is associated with depression and anxiety (Payton, Reference Payton2009) and hazardous work environments are reported to be a major cause of stress among employees, reducing their safety performance (Enshassi, El-Rayyes, & Alkilani, Reference Enshassi, El-Rayyes and Alkilani2015). Job demands also play a key role in influencing psychological distress among employees (Carlisle & Parker, Reference Carlisle and Parker2014). Employees working in a demanding industry such as the oil and gas sector may be more vulnerable to psychological distress because of the sensitivities associated with their jobs and an additional demand of being safety-conscious while performing their challenging jobs (Mirza & Isha, Reference Mirza and Isha2017). A continual need for devoting resources toward protecting themselves from psychosocial hazards will result in a considerable depletion of these resources among employees. This is likely to leave them with fewer resources to invest in improving their safety behaviors.

In a study examining the relationship between psychological distress and workplace safety, Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Xiang, Song and Wang2010) reported that psychological distress causes injuries among construction workers. Similarly, Jacobsen, Caban-Martinez, Onyebeke, Sorensen, Dennerlein, and Reme (Reference Jacobsen, Caban-Martinez, Onyebeke, Sorensen, Dennerlein and Reme2014) also found that psychological distress was the reason for construction workers' pain and injuries. Coal miners with high psychological distress also complained of more musculoskeletal pain in another study (Carlisle & Parker, Reference Carlisle and Parker2014). Siu et al. (Reference Siu, Kong, Phillips and Leung2004) examined the effects of psychological distress on occupational accidents and injuries. They found that psychological distress predicted occupational accidents. Overall, these studies suggest that psychological distress influences safety behaviors among employees. Thus, examining the relationship between psychological distress and safety-behaviors will give us a better understanding of the psychological distress–safety relationship.

Andrews, Hall, Teesson, and Henderson (Reference Andrews, Hall, Teesson and Henderson1999) state that psychological distress explains the extent of ‘psychological impairment’ in an individual. Psychological impairment is described as a condition which limits people's learning capabilities, performance on physical tasks, the ability to care for themselvesFootnote 1, etc. Dunbar (Reference Dunbar1993) found that anxiety and depression influences safety compliance behaviors among employees. In a study on oil production workers, Li, Jiang, Yao, and Li (Reference Li, Jiang, Yao and Li2013) found that psychological demands (mental and cognitive) have detrimental effects on safety compliance behaviors. Similarly, in a recent study, Smith, Hughes, DeJoy, and Dyal (Reference Smith, Hughes, DeJoy and Dyal2018) found that work stress causes burnout among workers, which negatively influences their safety behaviors. Psychological distress has also been reported to result in unsafe behaviors (Khosravi, Asilian-Mahabadi, Hajizadeh, Hassanzadeh-Rangi, Bastani, and Behzadan, Reference Khosravi, Asilian-Mahabadi, Hajizadeh, Hassanzadeh-Rangi, Bastani and Behzadan2014). These studies clearly indicate the harmful effects of work stress/psychological stress on safety behaviors among employees. Thus, it can be deduced that psychological distress compromises an individual's ability to actively participate in safety practices and comply with safety regulations.

Hypothesis 2

Psychological distress will be negatively associated with employees' safety compliance.

Hypothesis 3

Psychological distress will be negatively associated with employees' safety participation.

Mediating role of psychological distress

We propose that PSC perceptions positively influence workers' safety behaviors via reduced psychological distress. A psychosocially safe climate ensures employees increased organizational/managerial commitment to their psychological health and safety. Employees feel their health and safety is prioritized over production demands and effective communication policies are in place to address employee concerns. Such an environment also focuses on encouraging active participation of employees regarding psychological health and safety.

According to the conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989), employees struggle to preserve their resources and any threat to them is stressful. A high-level PSC will ensure minimum loss of psychological resources and will allow them to invest in their safety behaviors. As discussed earlier, high-level PSC decreases employee psychological health concerns (Yulita, Idris, & Dollard, Reference Yulita, Dollard, Shimazu, Bin, Dollard and Oakman2016), which means important psychological resources will not be lost as employees will not have to worry about their psychological health, thus, preserving these resources and enabling investing them toward improving their safety behaviors.

Blue-collar workers of the oil and gas industry are routinely faced with a challenging work environment. Their job responsibilities expose them to considerable physical and psychological risk. This is likely to have implications for their psychological health in terms of psychological distress. Any errors in such an environment can spell disaster, thereby accentuating the need for an additional focus on safety (Mirza & Isha, Reference Mirza and Isha2017). It is imperative for workers in such high-risk environments to comply with safety procedures. This requires their focus and attention that is possible only when they are not psychologically distressed. Management can ensure this by committing to provide a psychosocially safe climate (e.g., Hall, Dollard, and Coward, Reference Hall, Dollard and Coward2010; Dollard et al., Reference Dollard, Bailey, McLinton, Richards, Wes, Anne and Stephanie2012a, Reference Dollard, Opie, Lenthall, Wakerman, Knight, Dunn and MacLeod2012b; Yulita, Idris, and Dollard, Reference Yulita, Dollard, Shimazu, Bin, Dollard and Oakman2016). Based on this argumentation, we propose that psychological distress will mediate the relationship between PSC and employee safety compliance and participation.

In a study on part-time Canadian workers, Turner, Hershcovis, Reich, and Totterdell (Reference Turner, Hershcovis, Reich and Totterdell2014) found that psychological distress mediates the relationship between work–family conflict and injuries. Siu et al. (Reference Siu, Kong, Phillips and Leung2004) studied construction workers and reported partial support for mediating role of psychological distress between safety climate and safety performance. In a PSC-focused study, it was found that PSC reduces workers’ compensation claims by reducing their emotional exhaustion (Bailey, Dollard, McLinton, and Richards, Reference Bailey, Dollard, McLinton and Richards2015). Employees in psychosocially safe climates are less stressed about their safety which allows them to be more receptive toward safety information and enables them to properly employ safety gears and be more participative in safety activities (Zadow et al., Reference Zadow, Dollard, Mclinton, Lawrence and Tuckey2017) (Figure 1). Thus, we propose that

Hypothesis 4

Psychological distress will mediate the relationship between PSC and safety compliance.

Hypothesis 5

Psychological distress will mediate the relationship between PSC and safety participation.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework (- - - - - - = indirect effect; ——— = direct effect).

Method

Procedure and participants

Participants of the study were operation and production workers of eight different oil and gas organizations operating in three states of Malaysia (Pahang, Kedah, and Penang). Operation and production workers (mainly involved in oil extraction and processing) were included because the nature of their work exposes them to considerable safety challenges and risks (Mirza & Isha, Reference Mirza and Isha2017). These operation and production workers include material specialists, pipe-liners, and electricians, and civil and chemical foremen. Before testing hypothesis, analysis of variance was performed to confirm if there is a difference between these categories. Results confirmed that there is no difference between these groups in terms of the key variables of this study. The job description of operation and production workers in the oil and gas industry requires them to be extra vigilant in performing their job as their mistake can cause a catastrophe. Furthermore, the literature also reports such workers are highly susceptible to psychological distress (Durand & Marchand, Reference Durand and Marchand2005; Carlisle & Parker, Reference Carlisle and Parker2014).

The oil and gas sector is categorized as a ‘safety-sensitive’ industry in the safety literature (Mirza & Isha, Reference Mirza and Isha2017) because these workers operate under stressful conditions owing to their constant exposure to chemical and hazardous materials. Questionnaires (paper-based) were distributed during working hours with a cover letter ensuring confidentiality. The principal researcher remained in the organization during the process of questionnaire completion to clarify possible queries from respondents. Researchers were allowed limited time in one visit, extending the data collection time period to 4 months.

A total of 400 questionnaires were distributed, out of which 219 were returned (response rate 55%), which is acceptable given the lack of support provided to Malaysian researchers (Ali, Azimah Chew Abdullah, & Subramaniam, Reference Ali, Azimah Chew Abdullah and Subramaniam2009). Out of the total sample, 29 incomplete questionnaires were discarded. Thus, the overall sample of the study was N = 190. Majority of the respondents were male (80%). The largest age bracket was 20–30 years (39%) and most of the respondents (42%) had an organizational tenure between 0–5 years. A large proportion of the respondents answered in the Malay language (93%) while rest (7%) opted to respond in English.

Measures

The recommended back-translation technique (Brislin, Lonner, & Thorndike, Reference Brislin, Lonner and Thorndike1973) was used to translate scales except for psychological distress (already available in Malay). A bilingual questionnaire was designed to prevent comprehension difficulties. Both English and Malay language experts had a background of psychology and had good command over both the languages.

PSC was measured using the 12-item PSC scale (Hall, Dollard, & Coward, Reference Hall, Dollard and Coward2010). Items included ‘In my workplace senior management acts quickly to correct problems/issues that affect employees’ psychological health,’ ‘Senior management acts decisively when a concern of an employees’ psychological status is raised,’ ‘Senior management show support for stress prevention through involvement and commitment,’ ‘Psychological well-being of staff is a priority for this organization,’ ‘Senior management clearly considers the psychological health of employees to be of great importance,’ ‘Senior management considers employee psychological health to be as important as productivity,’ ‘There is good communication here about psychological safety issues which effect me,’ ‘Information about workplace psychological well-being is always brought to my attention by my manager/supervisor,’ ‘My contributions to resolving occupational health and safety concerns in the organization are listened to,’ ‘Participation and consultation in psychological health and safety occurs with employees,’ unions and health and safety representatives in my workplace,’ ‘Employees are encouraged to become involved in psychological safety and health matters,’ and ‘In my organization, the prevention of stress involves all levels of the organization.’ Anchoring points were: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree.

Psychological Distress was measured using the Malay version (Yusoff, Rahim, & Yaacob, Reference Yusoff, Rahim and Yaacob2009) of the General Health Questionnaire, GHQ-12 (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg1978). The original scale consisted of 12 items, however Shevlin and Adamson (Reference Shevlin and Adamson2005) suggested an alternative three factor model of GHQ-12 i.e., ‘Anxiety-Depression, Social Dysfunction, and Loss of Confidence.’ The current study used four items (‘Felt constantly under strain?,’ ‘Been feeling unhappy or depressed?,’ ‘Lost much sleep over worry?,’ and ‘Felt you could not overcome your difficulties?’) from the Anxiety-Depression factor, in line with previous studies (e.g., Turner et al., Reference Turner, Hershcovis, Reich and Totterdell2014). Anchoring points for the items were: 1 = Not at All, 4 = Much more than Usual. The focus of current study was specifically the stress component. Therefore, it was more relevant to use 4 factor items rather than the overall general scale of 12 items.

Safety compliance was measured using the scale of Neal and Griffin (Reference Neal and Griffin2006). The scale consists of three items (‘I use all the necessary safety equipment to do my job’; ‘I ensure the highest levels of safety when I carry out my job,’ and ‘I use the correct safety procedures for carrying out my job’). Anchoring points were: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree.

Safety participation was measured using the scale of Neal and Griffin (Reference Neal and Griffin2006). It consists of three items (‘I put in extra effort to improve the safety of the workplace,’ ‘I promote the safety program within the organization,’ and ‘I voluntarily carry out tasks or activities that help to improve workplace safety’). Anchoring points were: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree.

Data Analysis and Results

The proposed model was assessed with the Partial Least Square approach using Smart-PLS 3.2.7 software (Ringle, Wende, & Becker, Reference Ringle, Wende and Becker2015). We followed the recommended two-staged analytical practice (Anderson & Gerbing, Reference Anderson and Gerbing1988) to assess the measurement and structural models.

To compute the appropriate sample size, G* Power version 3.1.9.2 was employed. Using the .80 value recommended for social and behavioral sciences, the required sample size for the study was 68. Given that total sample size of the study is 190, it comfortably exceeds the required sample size for the study. The study also exceeds the minimum sample size recommended for PLS-SEM analysis i.e., 100 (Reinartz, Haenlein, & Henseler, Reference Reinartz, Haenlein and Henseler2009).

Common method variance

There exists a possibility of common method variance when data are collected from single source (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003), or cross-sectional research design is used by the study (Audenaert & Decramer, Reference Audenaert and Decramer2016). When a single factor explains majority of the variance in a data set than there is an issue of common method variance (Podsakoff & Organ, Reference Podsakoff and Organ1986). To evaluate the possibility of common method variance, Harman's one-factor test was employed. The results of the test showed that the single factor accounted for 34.93%, indicating that a common factor such as method (time of testing, single source) is not an issue for this data set.

Another method to assess common method variance is suggested by Bagozzi, Yi, and Phillips (Reference Bagozzi, Yi and Phillips1991). They suggested that in a correlation matrix, if the inter-correlations are significantly greater than .90 then there may exist an issue of common method variance. The results of correlation matrix in Table 2 indicate that all the values are lower than .90. Hence, both methods confirm that there is no serious issue of common method variance in this study.

Multicollinearity

Multicollinearity refers to whether independent variables in a regression model are highly correlated with each other, or are they highly correlated with dependent variable (Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, Reference Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt2016). According to, Ramayah, Cheah, Chuah, Ting, and Memon (Reference Ramayah, Cheah, Chuah, Ting and Memon2016), multicollinearity must be confirmed before hypothesis testing. In the current study the multicollinearity was confirmed through variance inflation factors (VIF). If the VIF value is greater than 3.33 then there exists a potential issue of multicollinearity (Kock & Lynn, Reference Kock and Lynn2012).

VIF was calculated to examine the issue of multicollinearity. Results showed that VIF values for PSC and psychological distress were 1.300 and 1.315, which were substantially lower than the threshold value of 3.33 (Kock & Lynn, Reference Kock and Lynn2012). This shows there are no multicollinearity issues in the study.

Measurement model

The measurement model involves two types of validity: convergent and discriminant validity. Convergent validity explains that items which are supposed to be theoretically related are actually converging on the construct to which they are associated (Urbach & Ahlemann, Reference Urbach and Ahlemann2010). The convergent validity includes item loadings, average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt2016). The validity of items is considered adequate if their loadings are equal or higher than .7, if loading of an item is between .4 and .7 than it should be considered for removal only if it can improve AVE or CR, and if the item loading is lower than .4 the item should be deleted (Kock, Reference Kock2014; Hair et al., Reference Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt2016). Item loadings were within the acceptable range (.699–.905). The CR and AVE were greater than .5 and .7 which is in line with the required threshold value suggested in the literature (Chin, Reference Chin, Vinzi, Chin, Henseler and Wang2010; Hair et al., Reference Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt2016) (Table 1).

Table 1. Item loadings, CR, and AVE

Discriminant validity explains the extent to which constructs are distinct from each other. We assessed the discriminant validity using the Fornell and Larcker (Reference Fornell and Larcker1981) criterion. According to this criterion, the square root of AVE for all constructs should be greater than correlations among all other constructs. Table 2 shows all values on the diagonal were greater than the correlation values of all other constructs, thus establishing discriminant validity of the model.

Table 2. Discriminant validity of constructs

Note: Values on the diagonal are square root of the AVEs.

Structural model

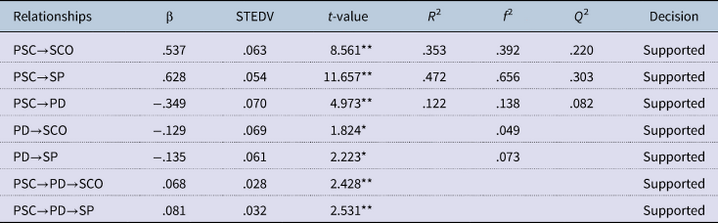

To assess the structural model, it is recommended to report R 2 values (predictive power), β-values, and t-values using a bootstrapping procedure of 5,000 samples (Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, Reference Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt2014). Kaufmann and Gaeckler (Reference Kaufmann and Gaeckler2015) also suggest reporting f 2 (effect size), and Q 2 values. As stated by Sullivan and Feinn (Reference Sullivan and Feinn2012), ‘While a p value can inform the reader whether an effect exists, the p value will not reveal the size of the effect. In reporting and interpreting studies, both the substantive significance (effect size) and statistical significance (p-value) are essential results to be reported’ (p. 279). We also ran blindfolding test to examine the predictive relevance (Q 2) of the model which is computed only for dependent variables. Q 2 validates that the observed relationships are not only statistically relevant but they have practical relevance as well, and is only applied on the endogenous (dependent) constructs with single or multiple items (Geisser, Reference Geisser1975).

Psychological distress showed moderate predictive power (R 2 = .122). Safety compliance (R 2 = .353) and safety participation (R 2 = .472) showed substantial predictive power. The predictive relevance (Q 2) for psychological distress (.082), for safety compliance (.220), and for safety participation (.303) were all greater than zero, indicating that the model has predictive relevance (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt2014). Table 3 shows effect sizes (f 2) for PSC with safety compliance and participation is substantial. PSC with psychological distress is small to moderate. While for other two relationships i.e., psychological distress with safety compliance and participation the effect size was also small to medium (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988).

Table 3. Results of hypotheses testing

**p < .001, *p < .05.

Hypotheses testing

We had predicted a negative association between PSC and psychological distress. Results showed support for Hypothesis 1 (β = −.349, p < .001). Hypothesis 2 predicted a negative relationship with safety compliance. Results showed support for Hypothesis 2 (β = −.129, p < .05). Hypothesis 3 predicted a negative association between psychological distress and safety participation (β = −.135, p < .05); thus, Hypothesis 3 was also supported.

To perform the mediation analysis, we followed the procedure recommended by Preacher, Rucker, and Hayes (Reference Preacher, Rucker and Hayes2007). According to the approach specified by them in order to achieve mediation emphasis should be on the indirect effect, if it's significant the mediation is achieved otherwise there is no mediation (Memon, Cheah, Ramayah, Ting, and Chuah, Reference Memon, Cheah, Ramayah, Ting and Chuah2018). Hypothesis 4 predicted that psychological distress would mediate the relationship between PSC and safety compliance. Table 3 shows significant support for the mediation path (β = .068, p < .001); thus Hypothesis 4 was accepted. Hypothesis 5 predicted a mediating role of psychological distress between PSC and safety participation. Results also showed support for Hypothesis 5 (β = .081, p < .001).

Although not hypothesized, we also tested for direct relationships between PSC and safety compliance, and between PSC and safety participation to see if there exists any direct association. Results showed a positive effect of PSC on both safety compliance (β = .537, p < .001) and safety participation (β = .628, p < .001). The examination of the direct relationship was considered to clarify association between key variables, however, these were non-hypothesized relationships. As such limited discussion has been provided on these relationships in the following section.

Discussion

The main objective of the paper was to examine the effects of PSC on workplace safety via psychological distress. First, we developed direct hypotheses linking PSC to psychological distress and then examined the impact of psychological distress on safety behaviors. Based on the conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989), it was proposed that high-level PSC will enable provision of sufficient resources to invest toward improving safety behaviors by reducing employee psychological distress.

As predicted, psychological distress mediated the relationship between PSC and safety behaviors. PSC, by reducing psychological distress, allows employees to invest their conserved resources in acquiring and improving their safety behaviors. Our study makes important theoretical contributions. First, it advances PSC theory in the workplace safety literature (Zadow et al., Reference Zadow, Dollard, Mclinton, Lawrence and Tuckey2017) by confirming that it also improves individuals’ safety compliance and participation by reducing psychological distress. Second, the results highlight the importance of improving the overall PSC as opposed to focusing on the physical safety climate alone (Zohar, Reference Zohar2010) in order to improve safety behaviors among employees. It has been suggested that studies should include both measures of climate (Yulita, Idris, & Dollard, Reference Yulita, Dollard, Shimazu, Bin, Dollard and Oakman2016) and the results of our study suggest that future studies may require both climate measures to improve our understanding about their role in workplace safety.

PSC was found to significantly reduce psychological distress, which is in line with earlier findings (Hall, Dollard, & Coward, Reference Hall, Dollard and Coward2010; Law et al., Reference Law, Dollard, Tuckey and Dormann2011; Dollard et al., Reference Dollard, Bailey, McLinton, Richards, Wes, Anne and Stephanie2012a, Reference Dollard, Opie, Lenthall, Wakerman, Knight, Dunn and MacLeod2012b). Our study adds to the PSC literature by showing that even in hazardous working conditions, psychosocially safe climates reduce psychological distress. Limited studies have examined this relationship in hazardous environments (Yulita, Idris, & Dollard, Reference Yulita, Dollard, Shimazu, Bin, Dollard and Oakman2016).

Our findings are in line with earlier findings on the psychological distress and workplace safety literature (Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Xiang, Song and Wang2010; Jacobsen et al., Reference Jacobsen, Caban-Martinez, Onyebeke, Sorensen, Dennerlein and Reme2014). However, most previous studies operationalized injuries as a measure of workplace safety and little work had been conducted on how psychological distress influences safety behaviors among workers. Our study fills an important void in the occupational health and safety literature. Our study, based on the concept of safety motivation (Neal & Griffin, Reference Neal and Griffin2006), established that low level of psychological distress improves workers’ safety compliance and participation. A recent review on workplace safety also highlighted the importance of contextual factors (Mirza & Isha, Reference Mirza and Isha2017). Although the review was specific to safety leadership, in general, it stressed upon considering the contextual requirements of different organizations regarding workplace safety. The results of our study confirmed that in the high risk oil and gas industry it is equally important to focus on psychosocial factors in order to improve safety behaviors of workers. It makes an important contribution to the occupational safety literature by explaining the importance of viewing it from a more holistic perspective. In industries like the oil and gas sector, where working conditions are stressful, organizations may also need to focus on psychosocial factors to improve safety behaviors of workers. Future studies seeking to investigate ways to improve safety should consider both psychosocial and physical safety.

Practical Implications

The study has some important implications for practitioners. Previously, safety climate was considered imperative for ensuring workplace safety (Zohar, Reference Zohar2010). However, results of our study indicate that organizational focus needs to expand beyond physical safety and should also focus on PSC to improve workplace safety. At the managerial level, establishing high-level PSC is not only important for psychological health but also for improving safety behaviors among members. Creating a work climate wherein employees feel their management is committed toward their psychological health, they don't feel overburdened with work requirements, and an overall psychosocially safe environment reduces stress among employees and enables them to be more productive in absorbing safety information, participating in safety practices and implementing them.

The PSC literature (Bailey, Dollard, & Richards, Reference Bailey, Dollard and Richards2015) explicates the practical measures needed to establish PSC within organizations. Ensuring the effective application of PSC through legislation for high-risk industries like oil and gas can be an effective way to practically implement PSC policies (e.g., Dollard et al., Reference Dollard, Bailey, McLinton, Richards, Wes, Anne and Stephanie2012a, Reference Dollard, Opie, Lenthall, Wakerman, Knight, Dunn and MacLeod2012b). Other best practices like inclusion of PSC in performance reviews of management and appointment on leadership positions based on individual commitment to PSC policies are some ways to do so (see Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Dollard, McLinton and Richards2015). Last, the results of our study clearly explain that high-risk organizations like oil and gas must prioritize workers’ psychosocial health over competing demands (e.g., production) to positively influence their safety behaviors.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The study is not without limitations. The cross-sectional nature of the research design means that our results must be viewed with caution. There were two reasons for adopting a cross-sectional design. First, collecting data from oil and gas industry was very difficult given the procedures and amount of time required to access the industry. Second, the lack of support provided to researchers in Malaysia (Ali, Azimah Chew Abdullah, & Subramaniam, Reference Ali, Azimah Chew Abdullah and Subramaniam2009) did not enable us to collect data multiple times. Although cross-sectional research is suitable at the initial stages of research (Barling, Loughlin, & Kelloway, Reference Barling, Loughlin and Kelloway2002), a longitudinal design is required to justify the causal process and mediation. Future studies should look to include other climate measures (specifically safety climate) to better understand their individual and comparative effects on workplace safety. A similar study has been conducted on psychological health (e.g., Idris et al., Reference Idris, Dollard, Coward and Dormann2012).

Data for our study were collected from the oil and gas sector of Malaysia. Therefore, caution must be exercised while generalizing these results elsewhere. It will be interesting to see if individuals in other industries and occupations that involve varying levels of job demands are equally affected by a psychosocially safe/unsafe climate. Our study did not explicitly measure employee resources but tested a conceptual model based on the premise of COR theory. We propose that an explicit measure of the employee resources conserved in a psychosocially safe climate would help advance knowledge on COR and would significantly add to the safety literature. A comparison of safety behaviors in a psychosocially safe climate versus an unsafe climate could further advance theory on safety and provide significant practical implications for managers and organizations.

Conclusion

PSC is an essential component in determining employees' safety behaviors. Drawing on conservation resources theory, this study confirms our hypotheses that PSC has a positive influence on safety behaviors through psychological distress. The findings of this study provide a significant contribution to the body of knowledge not only in terms of direction relationship between psychosocial safety and psychological distress but also the indirect effect of PSC on safety behaviors. In doing so, this is the first study that conceptualizes and empirically tested the mediating role of psychological distress between PSC and safety behaviors. Additionally there is a limited research on PSC in Asian setting particularly in South-East Asian countries. This study provides empirical evidence which is useful for both practitioners and academicians. The implications of these results for safety interventions and further research are discussed.

Author ORCIDs

Muhammad Zeeshan Mirza, 0000-0002-7582-9513; Sundas Azeem, 0000-0001-9742-822X.

Muhammad Zeeshan Mirza is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Engineering Management, College of E&ME, National University of Sciences and Technology. He holds a PhD in Management and Masters in HRM. His research interests include leadership, organizational climate, occupational health and safety, and organizational context.

Ahmad Shahrul Nizam Isha is an Associate Professor at the Department of Management and Humanities, Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS, Perak, Malaysia. He holds a PhD and a Postdoctoral fellowship in occupational health psychology. His areas of research include employee well-being, occupational health psychology, and health & safety at workplace.

Mumtaz Ali Memon is Assistant Professor and Head of Cluster at Air University, Islamabad, Pakistan. He is also the Managing Editor of the Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling (JASEM). He holds a PhD in Management, MBA in Human Resource Management (HRM), and MSc in Human Resource Development. His main research areas cover HRM practices, workplace behavior, and advanced quantitative research methods.

Sundas Azeem is a Lecturer at the Department of Management Sciences, Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto Institute of Science and Technology, Islamabad, Pakistan. She holds a Masters in HRM. Her areas of interest include organizational justice, impression management, attribution styles, and counterproductive work behavior.

Muhammad Zahid is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Management Sciences, City University of Science & Information Technology, Peshawar, Pakistan. He holds a PhD in Management and MS in finance. His areas of research include banking and finance, corporate sustainability, corporate governance, and financial performance.