Two decades of strategic management research on market orientation has clearly established its performance benefits (Greenley, Reference Greenley1995; Kumar, Subramanian, & Yauger, Reference Kumar, Jones, Venkatesan and Leone1998; Harris, Reference Harris2001; Hult & Ketchen, Reference Hult and Ketchen2001; Hult, Ketchen, & Slater, Reference Hult, Ketchen and Slater2005; Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008; Li, Wei, & Liu, Reference Li, Wei and Liu2010; Lee & Chu, Reference Lee and Chu2013). Kohli and Jaworski (Reference Kohli and Jaworski1990) initially conceptualized market orientation as the generation and dissemination of organization wide information and the appropriate organizational responses related to customer needs and preferences and the competition. The literature on market orientation has examined both the antecedents and consequences of such behavioural and cultural orientation on the part of organizations (e.g., Tyler, & Gnyawali, Reference Tyler and Gnyawali2009). Yet, in the evolution of this literature, several studies had cast doubt on the capability of market orientation to provide sustainable competitive advantage and highlighted its adoption as just a cost of doing business (e.g., Hamel & Prahalad, Reference Hamel and Prahalad1994; Christensen & Bower, Reference Christensen and Bower1996; Kumar, Jones, Venkatesan, & Leone, Reference Kumar, Subramanian and Yauger2011). These sceptical authors refer to sustainable competitive advantage as above industry average business performance over a long period of time (e.g., Hamel & Prahalad, Reference Hamel and Prahalad1994), as opposed to the short run performance benefits demonstrated in the literature. A key argument in this context was that market orientation may induce more adaptive learning (narrowly focussed on current customers’ stated needs) than generative learning (broader focus on unexpressed or unarticulated needs; Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008), which may ultimately limit the organization’s capability to provide a sustainable competitive advantage. After continued adverse criticism (e.g., Hamel & Prahalad, Reference Hamel and Prahalad1994; Christensen & Bower, Reference Christensen and Bower1996) of the concept that is now central to marketing thought, the market orientation literature has evolved to focus on the strategic concept of proactive market orientation (Atuahene-Gima, Slater, & Olson, Reference Atuahene‐Gima, Slater and Olson2005). This literature has increasingly focussed on the proactive dimension of market orientation (discovery and satisfaction of future customer needs), contrasting it to the responsive dimension of market orientation (e.g., Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004). This literature now considers proactive market orientation as a strategic orientation which is not merely responsive, and is alternatively conceptualized as generative learning (e.g., Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008) or as entrepreneurial orientation (e.g., Li, Wei, & Liu, Reference Li, Wei and Liu2010; Lee & Chu, Reference Lee and Chu2013). This line of recent research has established the performance and innovation benefits of proactive market orientation (e.g., Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004; Atuahene-Gima, Slater, & Olson, Reference Atuahene‐Gima, Slater and Olson2005; Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008). This literature argues that, in addition to being proactive and strategic, proactive market orientation also focusses on latent and unarticulated needs of customers, thereby focussing on the generation and dissemination of tacit as well as explicit knowledge in creating organizational responses (Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004; Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008).

Although this literature has established the general stability of the proactive market orientation–innovation and proactive market orientation–performance relationships (Greenley, Reference Greenley1995; Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004; Kirca, Jayachandran, & Bearden, Reference Kirca, Bearden and Hult2005; Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008; Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Subramanian and Yauger2011), respectively, there are several issues that remain to be addressed. First, despite significant links to the organizational learning (e.g., Slater & Narver, Reference Slater and Narver1995), organizational knowledge (e.g., Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004), and resource-based view (RBV) literatures (e.g., Hult & Ketchen, Reference Hult and Ketchen2001), this literature has not examined the moderating role of crucial constructs such as intrafirm causal ambiguity (degree to which decision makers lack an understanding of the relationship between organizational inputs and results) on the relationships between market orientation and performance and innovation, respectively. The RBV literature suggests that high levels of intrafirm causal ambiguity may serve as a barrier to the success of knowledge transfer (King, Reference King2007). However, its role in the proactive market orientation–innovation capability relationship is unclear and yet to be addressed. We contribute to the literature primarily by theoretically developing why and how intrafirm causal ambiguity moderates the relationship between proactive market orientation and innovation capability. Recent literature on proactive market orientation has equated it to generative learning (Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008) and the search for creating a base of tacit as well as explicit knowledge on future customer and market trends (Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004). Yet, although these developments imply the presence of specific organizational conditions to foster innovative capabilities, very little research has examined internal factors that moderate the relationship between market orientation and innovation capability (Atuahene-Gima, Slater, & Olson, Reference Atuahene‐Gima, Slater and Olson2005). There is growing theoretical and empirical evidence on the role of intrafirm causal ambiguity and the difficulties it creates for intrafirm (Szulanski, Cappetta, & Jensen, Reference Szulanski, Cappetta and Jensen2004; Uygur, Reference Williams, Vandenbergh and Edwards2013) and interfirm knowledge transfer (Simonin, Reference Simonin1999). We draw from these literatures in identifying, conceptualizing, and developing the moderating role of intrafirm causal ambiguity on the outcomes of proactive market orientation. This serves as a crucial contribution of this study on both theoretical and empirical fronts. Focussing on intrafirm causal ambiguity as a moderator can highlight potential facilitators and barriers to the successful implementation of a strategic orientation and thus help organizational managers in better aligning their organizations to these initiatives.

Second, although this literature has identified and examined the moderators of the market orientation–performance relationship (e.g., Slater & Narver, Reference Slater and Narver1994; Grewal & Tansuhaj, Reference Grewal, Chandrashekaran, Johnson and Mallapragada2001), corresponding examinations of the moderators of the market orientation–innovation relationship are limited in number (Kirca, Jayachandran, & Bearden, Reference Kirca, Bearden and Hult2005). In response to the inconsistent effects of environmental moderators of the market orientation–performance relationship (Kirca, Jayachandran, & Bearden, Reference Kirca, Bearden and Hult2005), several researchers have highlighted a fresh need to investigate the potential moderators of the market orientation–performance relationship (e.g., Grewal, Chandrashekaran, Johnson, & Mallapragada, Reference Grewal and Tansuhaj2013). One meta-analysis (Kirca, Jayachandran, & Bearden, Reference Kirca, Bearden and Hult2005) found an inconsistent pattern of results for market dynamism, competitive intensity, and technological turbulence as moderators, leading to the conclusion that there is no support for the moderating role of these three variables on the market orientation–performance relationship. Noting that the moderating relationships of important environmental factors are complex and difficult to model, researchers have suggested that this search for moderators should be directed to internal organizational factors as a result of market orientation’s demand on organizational resources to achieve innovation capability (e.g., Atuahene-Gima, Slater, & Olson, Reference Atuahene‐Gima, Slater and Olson2005; Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008; Tyler & Gnyawali, Reference Tyler and Gnyawali2009). Thus, although the benefits of a proactive market orientation on innovation and firm performance (e.g., Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004; Kirca et. al, Reference Kirca, Jayachandran and Bearden2011) are reasonably known, little is known about the moderators of the proactive market orientation–innovation relationship. Despite early conceptualizations in the literature on the links between market orientation and organizational learning (e.g., Slater & Narver, Reference Slater and Narver1995) and the corresponding implication of the RBV of the firm (e.g., Barney, Reference Barney1991; Hult & Ketchen, Reference Hult and Ketchen2001), this literature has not examined the moderating role of causal ambiguity, a critical construct in such theoretical frameworks (e.g., King & Zeithaml, Reference King and Zeithaml2001; Tyler & Gnyawali, Reference Tyler and Gnyawali2009). Causal ambiguity is recognized in this literature as a critical impediment to organizational learning and knowledge transfer (e.g., Szulanski, Reference Szulanski1996; Uygur, Reference Williams, Vandenbergh and Edwards2013). Our conceptualization and empirical testing of the moderating role of intrafirm causal ambiguity on the market orientation–innovation capability relationship serves as a unique contribution in this context.

While emerging economies such as India are going to be the key drivers of meaningful world economic growth in the near future (see Dhanraj & Khanna, Reference Dhanraj and Khanna2011), the market orientation literature has not paid sufficient attention to such emerging markets, with very few exceptions (e.g., Deshpande & Farley, Reference Deshpande and Farley1999; Li, Wei, & Liu, Reference Li, Wei and Liu2010). Researchers have suggested that the fundamental mechanisms that make markets work, viz, institutions, are either missing (Khanna & Palepu, Reference Khanna and Palepu2010), going through serious transformations (Aulakh, Reference Aulakh2009) or discontinuous change (Chittoor, Sarkar, Ray, & Aulakh, Reference Chittoor, Sarkar, Ray and Aulakh2009) in emerging markets. Correspondingly, in contrast to the copycat and cost-based strategies that were key predictors of global performance (e.g., Aulakh, Kotabe, & Teegen, Reference Aulakh, Kotabe and Teegen2000) of firms from emerging economies, innovation, and differentiation-based strategies on the part of these firms are becoming more important today (e.g., Chittoor et al., Reference Chittoor, Sarkar, Ray and Aulakh2009). However, the market orientation literature has yet to address the innovation consequences of such strategic orientation in emerging markets such as India. Although it is possible that the predominance of cost strategies in emerging markets may have led to the insignificant or negative findings of the market orientation–performance relationship in the past, the post-liberalization realities in emerging markets such as India may yield different results, which have yet to be examined. We contribute to the strategic orientation literature (e.g., Lee & Chu, Reference Lee and Chu2013) by providing empirical evidence from India on the relationship between proactive market orientation and innovation capability leading to performance.

Specifically, the primary research objective of this paper is to study the relationship between proactive market orientation and innovation capability, with a subsequent link to business performance. More importantly, we investigate the moderating impact of intrafirm causal ambiguity on the relationship between proactive market orientation and innovation capability. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. We first describe the Indian economic scenario followed by a review of existing literature to develop hypotheses. We then present the method used to collect data and then present the results. In the next section, we conclude by summarizing the findings and discussing managerial and research implications.

Indian Economy and Consumers

India is witnessing increasing levels of competitive intensity and market dynamism, with its institutions going through serious transformation and discontinuous change (e.g., Aulakh, Reference Aulakh2009; Chittoor et al., Reference Chittoor, Sarkar, Ray and Aulakh2009). Since the introduction in 1991 of economic reforms, privatization, and liberalization policies in India, the country has begun to experience rapid economic growth, as markets opened for international competition and investment. India has now emerged as one of the fastest-growing economies in the developing world, with the economy experiencing consistently higher levels of market turbulence and competitive intensity (Dhanraj & Khanna, Reference Dhanraj and Khanna2011). Examining the impact of proactive market orientation on innovation capability and performance in a context representing environmental turbulence is likely to make significant contributions to the literature.

Although Indian companies have traditionally adopted cost-based strategies (e.g., Aulakh, Kotabe, & Teegen, Reference Aulakh, Kotabe and Teegen2000), they are increasingly compelled to adopt innovation and differentiation strategies to survive in the context of increasing munificence and competitive intensity (e.g., Chittoor et al., Reference Chittoor, Sarkar, Ray and Aulakh2009). Indian organizations and their structures are also experiencing serious transformation and change following the privatization and liberalization of the early 1990s. Whereas pre-liberalization organizations (dominated by the public sector) were high on formalization (definition of roles, procedures, and authority), a factor expected to be negatively related to market orientation (see Kirca, Jayachandran, & Bearden, Reference Kirca, Bearden and Hult2005), post-liberalization firms (largely in the private sector) are increasingly moving away from this structure (see Barnabos & Mekoth, Reference Barnabos and Mekoth2010). Whereas pre-liberalization public sector firms were high on centralization (limited delegation of decision making), another factor expected to be negatively related to market orientation (see Kirca, Jayachandran, & Bearden, Reference Kirca, Bearden and Hult2005), the post-liberalization private sector is increasingly decentralized (see Aggarwal, Reference Aggarwal2003). Market-based reward systems are also increasingly becoming prevalent in the new Indian scenario, thereby favouring the presence of market orientation in firms, more so than ever before (see Aggarwal, Reference Aggarwal2003).

The market orientation literature suggests that the relationships with innovation and performance, respectively, are subject to cultural factors such that they are stronger in low power distance and uncertainty avoidance cultures (Kirca, Jayachandran, & Bearden, Reference Kirca, Bearden and Hult2005). Thus, whether or not the relationships tested in this study will be empirically supported has been hitherto untested. India is characterized by a higher level of power distance and lower level of uncertainty avoidance than most Western cultures (House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, Reference House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman and Gupta2004), dominant in the literature. This study, especially the third and fourth hypotheses linking innovation capability, new product development (NPD) success, and performance in an Indian context constitute a contribution to this literature. Although there are a few studies on market orientation in India (e.g., Adhikari & Gill, Reference Adhikari and Gill2012) a significant majority of them are in the manufacturing sector, and none of them have examined innovativeness of firms in the service sector, as we do in this study. We believe that relatively higher levels of differentiation strategies, lower levels of formalization and decentralization, and higher levels of market-based reward systems, highlighted above, will be in favour of finding support for the hypotheses formulated in this study. By examining innovation capability, hitherto unaddressed in India, we contribute to the literature by adding crucial elements to extant knowledge from an economy that is likely to be one of the key drivers of meaningful future economic growth.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

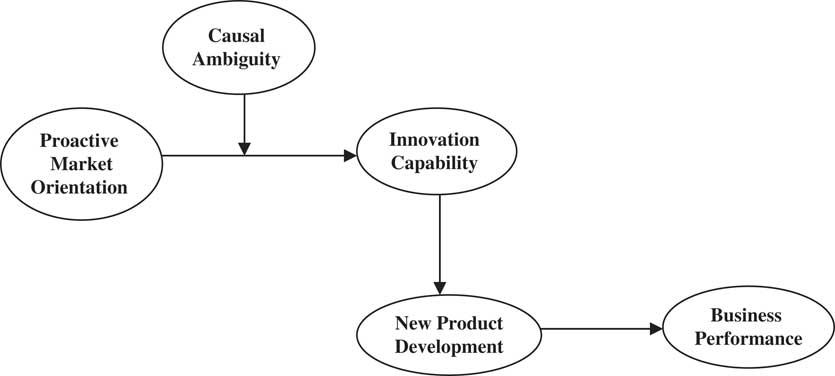

Market orientation is used by marketing practitioners as an indicator of the extent to which a firm implements the marketing concept. A market-oriented firm is presumed to have superior market sensing and customer linking capabilities which are presumed to assure them higher profits in comparison with firms that are less market oriented (Day, Reference Day1994). We define market orientation as the generation and dissemination of organization wide information and the appropriate organizational responses related to customer needs and preferences and the competition (Kohli & Jaworski, Reference Kohli and Jaworski1990). Further, following Narver, Slater, and Maclachlan, ‘market orientation that leads customers rather than merely responds to them’ is labelled for this study’s purposes as proactive market orientation (Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004, p. 336). Proactive market orientation attempts to understand and to satisfy customers’ latent needs (Slater & Narver, Reference Slater and Narver1998; Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008). In the rest of this paper, we focus exclusively on proactive market orientation. The theoretical model tested in this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Hypothesized model for proactive market orientation

In what follows, we develop the rationale for these relationships by drawing on the literatures on market orientation and RBV of the firm.

Innovation capability

We use the traditional distinction between resources and capabilities in the resource-based literature (e.g., Ketchen, Hult, & Slater, Reference Jain and Bhatia2007) and conceive innovation capability as the unique organizational ability required to deliver innovation. Specifically, we define innovation capability as the ability to create and develop organizational processes that provide (Deshpande, Farley, & Webster, Reference Deshpande, Farley and Webster1993) the organizational readiness to develop and bring new products to markets ahead of competitors. Innovation capability is important for effective innovation performance in the form of new product success, and is dependent on the outside-in process of market orientation for key inputs (see Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004). Market orientation is expected to lead to high levels of innovation capability because it drives a continuous disposition to meeting customer needs and it emphasizes greater information use in the form of intelligence generation and intelligence diffusion (Atuahene-Gima, Slater, & Olson, Reference Atuahene‐Gima, Slater and Olson2005). It is the philosophy of market orientation and the corresponding attention to future customer needs (especially latent and unarticulated) that enables the organization to create innovation capability (Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008). By engaging in deep relationships with key customers, the proactive market-oriented firm develops a customer orientation that is capable of discovering unaddressed and therefore unidentified needs (Slater & Narver, Reference Slater and Narver1998). Subsequently, by generating and disseminating knowledge of such customer needs throughout the organization, and placing it in the context of their competitor orientation (understanding of rivals’ strengths and weaknesses and how they are meeting customers’ needs) the proactive market-oriented firm is able to create the required organizational responsiveness (Hult, Ketchen, & Slater, Reference Hult, Ketchen and Slater2005), akin to our conception of innovation capability here. Such responsiveness, however, requires shared interpretation (Slater & Narver, Reference Slater and Narver1995) provided by generative as opposed to adaptive learning (Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008). Overall, therefore, the organization wide generation and dissemination of ‘new’ knowledge of customer needs, placed in the context of ‘developing’ knowledge of competitors’ offerings, spurs the interfunctional coordination of different organizational units possessing a common (shared) understanding, and yields the capability to innovate. It is worthy of note that this argumentation is reflective of the fact that customer orientation, competitor orientation, and interfunctional coordination are the three components of market orientation as originally conceived by Narver and Slater (Reference Narver and Slater1990), which we have now blended with Kohli and Jaworski’s (Reference Kohli and Jaworski1990) original conceptualization.

Proactive market orientation is specifically likely to stimulate the development and implementation of novel ideas that address current and future customer needs (Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004). Starting with novel ideas devoid of associated customer needs, on the other hand, results in a search for problems for which these ideas may be solutions. By engaging people in generative learning rather than adaptive learning, proactive market orientation focusses on latent customer needs and can therefore alert the firm to new technologies (e.g., Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008) and new markets (Slater & Narver, Reference Slater and Narver1998). Generative learning thus endows the proactive market-oriented firm with the capability to look beyond existing boundaries of customers and markets, thereby resulting in greatly enhanced problem-solving capacity for the teams involved in innovation (Hult, Ketchen, & Slater, Reference Hult, Ketchen and Slater2005; Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008). Such proactive market orientation is therefore likely to foster the development of organizational processes that provide an organizational readiness for innovation and development of new products and services, that is, innovation capability.

As reflected in our theoretical model (see Figure 1), we conceptualize innovation capability as an outcome of market orientation which facilitates the development of successful new products and services. The evolution in this literature from the concept of market orientation to that of proactive market orientation is based mainly on the nature of customer needs, with researchers increasingly emphasizing both expressed and latent, in addition to both current and future needs (Slater & Narver, Reference Slater and Narver1998; Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004). Further, proactive market orientation focusses on expressed as well as latent (difficult to articulate, difficult to anticipate, etc.) needs of customers (Slater & Narver, Reference Slater and Narver1998; Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004). The discovery of latent, unarticulated needs can often lead to deeper insight into customer demands and to uncover new market opportunities, and thus to more commitment to the development of innovative products and services. This is done by, for example, working closely with lead users or undertaking experiments to discover future needs (Slater & Narver, Reference Slater and Narver1998; Atuahene-Gima, Slater, & Olson, Reference Atuahene‐Gima, Slater and Olson2005). We therefore propose a direct relationship between proactive market orientation and innovation capability in the Indian context:

Hypothesis 1: The greater the proactive market orientation of firms, the higher their level of innovation capability.

The Moderating Role of Intrafirm Causal Ambiguity

We draw from the RBV literature to theorize how and why intrafirm causal ambiguity (e.g., Barney, Reference Barney1991; Szulanski, Reference Szulanski1996; Simonin, Reference Simonin1999; Szulanski, Cappetta, & Jensen, Reference Szulanski, Cappetta and Jensen2004; King, Reference King2007; Ambrosini & Bowman, Reference Aiken and West2010; Uygur, Reference Williams, Vandenbergh and Edwards2013) moderates the relationship between proactive market orientation and innovation capability. But first, we reaffirm the need to examine internal organizational factors as relevant moderators of the relationship between proactive market orientation and its outcomes. Some have noted that very few studies have examined internal organizational factors as moderators in this context, despite the organizational and resource demands made by proactive market orientation practices (e.g., Atuahene-Gima, Slater, & Olson, Reference Atuahene‐Gima, Slater and Olson2005; Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008; Tyler & Gnyawali, Reference Tyler and Gnyawali2009). Moreover, although the literature has examined the moderators of the market orientation–performance relationship, it has yet to examine the moderators of the market orientation–innovation (capability) relationship.

We believe that intrafirm causal ambiguity, drawn from the RBV literature, plays a critical moderating role in the processes surrounding proactive market orientation for several reasons outlined here. First, several researchers in the market orientation literature have developed significant links between the core construct of market orientation and organizational learning (Slater & Narver, Reference Slater and Narver1995), organizational knowledge (Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004), and RBV (Hult & Ketchen, Reference Hult and Ketchen2001) literatures, respectively. Slater and Narver (Reference Slater and Narver1995) suggested that market orientation provides a foundation for organizational learning and helps in the development of new knowledge that becomes the basis for competitive advantage. Narver, Slater, and Maclachlan (Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004) suggested that proactive market orientation is essentially the generation, dissemination, and shared interpretation of knowledge about expressed and latent customer needs. Hult and Ketchen (Reference Hult and Ketchen2001) used the RBV as an overarching framework for theoretically underpinning the role of strategic marketing resources constituting proactive market orientation practices. Thus, the emerging view of proactive market orientation is that it is primarily constituted of the knowledge processes of (a) developing a customer orientation with ‘new’ knowledge of expressed and latent customer needs, (b) developing a competitor orientation by combining old and new knowledge of strengths and weaknesses of rivals and their offerings, and (c) interfunctional coordination among different business units to disseminate such knowledge and develop a shared interpretation that can guide organizational responsiveness. Proactive market orientation, therefore, involves the entire range of processes surrounding organizational learning (e.g., Slater & Narver, Reference Slater and Narver1995) and transfers of information and knowledge among different business units (e.g., Hult & Ketchen, Reference Hult and Ketchen2001), while also involving the development of a shared interpretation of knowledge (Hult, Ketchen, & Slater, Reference Hult, Ketchen and Slater2005). However, intrafirm causal ambiguity is likely to pose a number of challenges to these processes of knowledge transfer (e.g., Uygur, Reference Williams, Vandenbergh and Edwards2013) and development of shared interpretation, especially in the creation of organizational processes of innovation capability, as we show in what follows.

Intrafirm causal ambiguity

The theoretical model developed here focusses on an issue that is central to knowledge transfer and organizational learning, that is, causal ambiguity, which is the degree to which decision makers understand (or lack an understanding of) the relationship between organizational inputs and results (Barney, Reference Barney1991; Simonin, Reference Simonin1999; King, Reference King2007; Ambrosini & Bowman, Reference Aiken and West2010; Uygur, Reference Williams, Vandenbergh and Edwards2013). Causal ambiguity is central to the RBV of the firm (Barney, Reference Barney1991; King & Zeithaml, Reference King and Zeithaml2001) and therefore the knowledge-based theory of the firm (Grant, Reference Grant1996), but is also relevant to the behavioural theory of the firm (Cyert & March, Reference Cyert and March1963) and therefore the organizational learning literature (Huber, Reference Huber1991). King (Reference King2007) identifies organizational boundaries as separating the construct of causal ambiguity into intrafirm and interfirm causal ambiguity and further suggests that both of these exist in organizations at different time points. We first draw on several facets of causal ambiguity and its consequences for knowledge transfer to highlight its interest to us in the context of the theoretical model tested here.

Several studies have identified the challenges posed by intrafirm causal ambiguity for knowledge transfer. King (Reference King2007) identified evidence (see Simonin, Reference Simonin1999) suggesting that an arduous relationship between the two entities in a merger context may be coincident with high levels of causal ambiguity and may thus affect knowledge transfer in such contexts. Simonin (Reference Simonin1999) found that causal ambiguity played a highly critical role in knowledge transfer by completely mediating the impact of constructs such as tacitness of knowledge, knowledge complexity, cultural distance, and organizational distance on successful technological knowledge transfer in strategic alliances. Highlighting the role of causal ambiguity in making knowledge transfer difficult, Uygur (Reference Williams, Vandenbergh and Edwards2013) theoretically developed two new constructs (viz, relevance of knowledge, and locality) to add to two previously known antecedents of causal ambiguity (viz, knowledge complexity, and tacitness; e.g., Simonin, Reference Simonin1999). Thus, it is now well recognized that causal ambiguity plays a critical role in knowledge transfer by making it difficult. Proactive market orientation, as we have briefly noted earlier, depends significantly on learning and knowledge processes, including its transfer within the organization. We therefore argue that intrafirm causal ambiguity is likely to play a moderating role on the effectiveness of proactive market orientation and develop it further, in what follows.

Role of intrafirm causal ambiguity in market orientation

Intrafirm causal ambiguity could either have a strong or weak effect on the understanding and implementation of proactive market orientation as we explain here. Although proactive market orientation will be effective in creating and developing organizational processes of NPD in a quick and efficient manner even under conditions of high causal ambiguity, this effectiveness is much higher for low causal ambiguity. First, we know from the RBV literature that intrafirm causal ambiguity among middle managers is relatively higher and more critical for firm performance than that among top managers (King & Zeithaml, Reference King and Zeithaml2001). Next, the market orientation literature suggests that although top managers have a comprehensive understanding of their firms’ market orientation, middle managers are unlikely to have a similar understanding (Deshpande, Farley, & Webster, Reference Deshpande, Farley and Webster1993; Greenley, Reference Greenley1995). This literature also suggests that middle managers may have more uncertainty than top managers about the appropriate culture and attitudes required for effective market orientation (Greenley, Reference Greenley1995). We suggest that this is mainly because middle managers with high levels of intrafirm causal ambiguity may have difficulty understanding the critical (causal) relationships between managerial practices and innovation outcomes in a specific context (Ambrosini & Bowman, Reference Aiken and West2010; Uygur, Reference Williams, Vandenbergh and Edwards2013). Other findings from the market orientation literature, based on in-depth cognitive study using cognitive mapping techniques (Tyler & Gnyawali, Reference Tyler and Gnyawali2009), suggest that core cause-effect beliefs in this domain vary widely across organizational levels and functions. The greater the gap in beliefs between different functions and levels of managers, the higher is the level of causal ambiguity (Szulanski, Cappetta, & Jensen, Reference Szulanski, Cappetta and Jensen2004; Ambrosini & Bowman, Reference Aiken and West2010) about the precise ways and means through which market orientation works in a specific firm’s context. Thus, the market orientation literature and the findings therein (Greenley, Reference Greenley1995; Tyler & Gnyawali, Reference Tyler and Gnyawali2009) suggest that there is significant variation in intrafirm causal ambiguity about the processes underlying proactive market orientation across different levels of management. We lay a foundation for our theorizing here on the basis of these findings from the market orientation literature.

First, proactive market orientation is essentially a process of creating, transferring, and leveraging a base of tacit and explicit knowledge about expressed as well as unarticulated and unanticipated future needs of customers (Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004). The innovation literature suggests that innovation capability derives from the way in which knowledge sets are constructed and leveraged, with the existence of multiple possibilities in attempting to fulfil expressed versus latent needs (Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008). Expressed needs represent market-pull factors and latent needs represent technology-push factors (Ettlie & Subramanian, Reference Ettlie and Subramanian2004). A balanced emphasis on both types of needs is critical for establishing innovation capability that has potential to lead to positive outcomes. The effectiveness of the ways in which these knowledge sets are leveraged to yield innovation capability varies as a function of intrafirm causal ambiguity.

In the process of creating innovation capability from proactive market orientation, the complexity of new knowledge of customer needs is likely to be more easily handled when causal ambiguity is low rather than high (e.g., Simonin, Reference Simonin1999; Uygur, Reference Williams, Vandenbergh and Edwards2013). Additionally, the tacitness of new knowledge of unexpressed and latent customer needs is also likely to be more easily handled under low causal ambiguity conditions than high (e.g., Szulanski, Reference Szulanski1996). Sharing this knowledge by placing new knowledge in the context of previously existing customer and competitor knowledge is also likely to be more complicated for high versus low causal ambiguity, by virtue of its differential relevance to the existing knowledge base (e.g., Uygur, Reference Williams, Vandenbergh and Edwards2013), for these two conditions. Top managers are likely to have a better understanding (lower causal ambiguity) of the firm’s market orientation than its middle managers (Tyler & Gnyawali, Reference Tyler and Gnyawali2009). Additionally, managers in different functions, whose interfunctional coordination is critical for the success of market orientation, are likely to have different levels of causal ambiguity (Greenley, Reference Greenley1995). Therefore, leveraging ‘new and developing’ knowledge on customers and competitors is likely to depend on the shared interpretation of it, the effectiveness of which is likely to vary as a function of varying levels of causal ambiguity across organizational levels. In sum, therefore, the proactive market orientation processes of creating, sharing and leveraging customer and competitor knowledge are likely to be more effective in creating and developing crucial organizational processes required for the development of new products under low rather than high causal ambiguity.

As indicated above, under ideal conditions, such an outside-in process is likely to lead to smooth implementation of market orientation and to contribute to the development of innovation capability. Under conditions of high causal ambiguity, however, managers have difficulty in creating and sharing the base of tacit and explicit knowledge that is required for effective implementation of market orientation. Higher levels of causal ambiguity, relative to lower levels, make it difficult for managers to effectively choose from, prioritize, and organize the multiple pieces of tacit and explicit knowledge relating to customers and competitors, in addition to knowledge related to market-pull versus technology-push factors. Sharing and leveraging knowledge from this knowledge base is less effective in creating innovation capability than under conditions of low causal ambiguity. This difficulty in creating and sharing the knowledge base leads to lower levels of innovation capability. Under conditions of low causal ambiguity, on the other hand, managers are likely to have relative ease in creating and sharing such knowledge, thereby not having an impact on the otherwise strong relationship between market orientation and innovation capability. Thus, each of the components of market orientation, viz, customer orientation, competitor orientation, and interfunctional coordination required for market orientation to contribute to innovation capability is likely to be smoother and more effective under conditions of low causal ambiguity than when it is high. Thus, high levels of intrafirm causal ambiguity among managers may make the processes of tracking customers, generating intelligence, diffusing intelligence, and engaging in interfunctional coordination less effective in creating innovation capability than under conditions of low causal ambiguity. Therefore, market orientation is likely to be more strongly related to innovation capability under conditions of low causal ambiguity than high causal ambiguity. Thus:

Hypothesis 2: The relationship of proactive market orientation and innovation capability is moderated by causal ambiguity such that this relationship is stronger for lower levels of causal ambiguity than for higher levels.

Innovation capability and NPD success

We defined innovation capability earlier as the ability to create and develop organizational processes that provide the organizational readiness to develop and bring new products to markets ahead of competitors. NPD success, on the other hand, refers to the successful development of a sufficient level of quantity and quality of new products and services. It is not sufficient to bring a high quantity of new products to markets faster than competitors for them to succeed. The relationship of innovation capability with NPD success is dependent on the ways in which the relevant knowledge sets have been constructed and leveraged in creating innovation capability, as noted earlier. Focussing more on knowledge related to expressed needs (market-pull) rather than latent needs (technology-push) in the construction of innovation capability could result in different levels of NPD success. A certain level of uncertainty exists in the conversion of breakthrough concepts into ready-for-market products/services (Ettlie & Subramanian, Reference Ettlie and Subramanian2004). Additionally, financial and market success of new products depend on many environmental, cultural, and market factors (Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008) all of which cannot be anticipated in dynamic markets, such as those in India, some of which may lead to failure.

Our central argument is that firms with higher levels of innovation capability are better positioned (Hult & Ketchen, Reference Hult and Ketchen2001) than other firms to effectively target appropriate markets, to more effectively develop products/services, and to better position the products/services within these markets (Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004; Lin, Tu, Chen, & Huang, Reference Lin, Tu, Chen and Huang2013). However, this better positioning is still subject to uncertainty, risk, and several factors related to the local market and the local environment (see Galvin, Reference Galvin2014), as noted above. Specifically, organizational responsiveness may well be a function of prevailing levels of power distance and uncertainty avoidance in the country. The innovation capability required for realizing the potential of strategic resources involves achieving alignment with other important organizational elements (Ketchen, Hult, & Slater, Reference Jain and Bhatia2007), which may be specific to the cultural context (Galvin, Reference Galvin2014). The innovation capability resulting from market orientation reflects organizational capabilities (Atuahene-Gima, Slater, & Olson, Reference Atuahene‐Gima, Slater and Olson2005) in information generation and use, and involves complex interactions among individuals and departments within the firm (Jaworski & Kohli, Reference Kapur and Ramamurti1993), targeted specifically to developing new products and services, and positioning them adequately in appropriate markets. Effective execution of these capabilities in these specific contexts can make the difference between financial (and market) success and failure of the new products developed. Although many studies have found evidence of a strong, positive, and direct relationship between market orientation and a new product’s market performance (e.g., Matsuno, Mentzer, & Ozsomer, Reference Matsuno, Mentzer and Ozsomer2002; Atuahene-Gima, Slater, & Olson, Reference Atuahene‐Gima, Slater and Olson2005; Bodlaj, Coenders, & Zaskar, Reference Bodlaj, Coenders and Zaskar2012), these studies have been done in other country contexts. The effectiveness with which proactive market orientation relates to innovation capability (as in previous hypothesis) and subsequently to NPD success (here) has not been examined in India. If these relationships are stronger in manufacturing versus services, stronger in low versus high power distance, and stronger in high uncertainty avoidance cultures, as the literature suggests (Kirca, Jayachandran, & Bearden, Reference Kirca, Bearden and Hult2005) positive findings from our study can bring new evidence to this literature. Our study is characterized by a relatively higher focus on service firms, conducted in a country characterized by relatively higher power distance and relatively lower uncertainty avoidance than most Western countries (see House et al., Reference House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman and Gupta2004).

Although not without risk of failure, the innovation capability resulting from uncovering latent customer needs that are unstated, results in product development that is higher in both quantity and quality than otherwise (Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004). Additionally, although building innovation capability is risky and subject to local market factors, it has the potential to bring higher rewards in the form of NPD success. Based on the above, we hypothesize the following with specific reference to India:

Hypothesis 3: The greater the innovation capability of an organization, the higher its NPD success.

Proactive market orientation and business performance

As argued earlier, the strategic resources represented by proactive market orientation are only a potential, realization of which requires innovative capability and NPD success. A substantial portion of the effect of market orientation on performance is accounted for by innovativeness, in general (Kirca, Jayachandran, & Bearden, Reference Kirca, Bearden and Hult2005), which can be seen as the sum of innovation capability and NPD success in this study. NPD success combined with general effectiveness and efficiency in organizational operations translates into business performance. Innovations in the form of new products resulting from a focus on expressed needs can produce higher performance in the short run at the expense of long-run performance, whereas those focussing excessively on latent needs can undermine short run performance (Atuahene-Gima, Slater, & Olson, Reference Atuahene‐Gima, Slater and Olson2005; Ketchen, Hult, & Slater, Reference Jain and Bhatia2007). Business performance is defined here as the achievement of a relatively better market position (i.e., market share), resulting in relatively higher profitability, and relatively higher return on investment. Thus, the effect of proactive market orientation on business performance is mediated by innovation capability and the NPD success resulting from such capability. The business performance literature has highlighted the need for an optimum level of alignment between organizational strategy and environmental factors (Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008), with this being critical in dynamic environments such as those in India. Both innovation capability and NPD success help firms in responding to changes in the environment and obtaining the required level of organization–environment fit (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Tu, Chen and Huang2013). Product performance results in business performance only after a certain time lag (Lakshman & Parente, Reference Lakshman and Parente2008) and only when the organizational processes surrounding the launch and sales of new products are efficient from a cost perspective. Since market orientation has been shown to be strongly related to both cost- and revenue-based performance measures, it is only reasonable to argue that the NPD success derived from market orientation is linked to business performance in the form of market share, return on investment, and profitability (Kirca, Jayachandran, & Bearden, Reference Kirca, Bearden and Hult2005). Thus, we offer the following mediation hypothesis for the Indian context:

Hypothesis 4: The impact of proactive market orientation on business performance is mediated by innovation (including innovation capability and NPD success).

Method

The hypotheses were tested using 220 survey responses to a questionnaire containing measures of the key constructs in this study which were completed by middle managers working in the marketing function of firms in India. The participants were solicited from part-time executive education programs (2-year duration) from two premier business schools in India, one in the north of the country, and the other in the south. A total of 574 executives from these two business programs were solicited to participate in this study through presentations made by research collaborators. The survey questionnaires were posted online (Google Drive) and a link to the survey was sent to all these participants via email. Three reminder emails were sent to the nonrespondents to participate in the survey. We received 220 complete responses yielding a response rate of 38.33%. Consistent with the literature (e.g., Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008), we compared late responses with early responses to assess nonresponse bias following the reasoning that late respondents are more like nonrespondents and any difference between them is likely to be symptomatic of nonresponse bias (Armstrong & Overton, Reference Armstrong and Overton1977). We performed t-tests on the responses and found no significant differences between these two groups on any of the variables (size, performance, R&D investment, NPD). Thus, although there may be residual nonresponse bias, it is not likely to be a serious problem in this study. A majority of the respondents were male (90%) and possessed an average experience of 10.28 years. The managerial experience of these respondents (in the focal organization) had an average of 5.47 years. A majority of these respondents worked in the service sector (82.7%) with the rest coming from the manufacturing sector. About 5.9% of the respondents came from the retail sector, with others coming from telecommunication services (11.4%), financial services (10.9%), insurance services (0.9%), and other services (39.1%).

The survey instrument contained 7-point Likert type scale items pertaining to the hypothesized constructs, including the independent and dependent constructs, in addition to background questions. The response format was varied across items pertaining to the independent and dependent constructs to reduce common method variance. All of the independent constructs were measured using 7-point Likert type scales varying from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The dependent constructs had specific response formats described below. We describe all the scale questions here and show the questions pertaining to the items retained after confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in Table 1.

Table 1 Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for measurement model in the study

CFI=comparative fit index; IFI=incremental fit index; NFI=normed fit index; RMSEA=root mean square error of approximation; CMIN=calls the Chi-Square statistic.

We measured proactive market orientation using eight items from the scale used by Narver, Slater, and Maclachlan (Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004). As can be seen in the CFA results shown in Table 1, six of these items were retained for subsequent analyses.

Innovation capability was assessed with three items previously used in India from Deshpande and Farley (Reference Deshpande and Farley1999), which has later been used in many other studies (e.g., Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004). Two questions were used to assess the quantity and quality, respectively, of NPD by slightly modifying the single item used by Narver, Slater, and Maclachlan (Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004). For NPD, respondents were asked to indicate their responses on a 7-point scale varying from much lower to much higher by comparing with all other competitors over the last 3 years. For business performance respondents were asked to report on a 7-point Likert scale, relative to all their competitors over the last 3 years, about their return on investment, market share, and performance of their products and services, drawn from previous research (Lakshman & Parente, Reference Lakshman and Parente2008). Respondents provided responses on these performance items on a 7-point scale varying from much lower to much higher. Although our measure of business performance is subjective and hence inherently limited, the literature has noted a close relationship between objective and subjective indicators of performance (see Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008). Following precedent, we combined the three measures into a scale based on relative comparisons by the respondents (see Lakshman & Parente, Reference Lakshman and Parente2008; Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008).

We used a slightly modified and reduced (three items) version of the 6-item scale used by Szulanski (Reference Szulanski1996) to measure causal ambiguity (the other three items are not applicable in this context). As shown in Table 1, two of these three items were retained after CFA. Causal ambiguity was measured on a 7-point scale varying from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

In addition to the above, we used several control variables in the tests of the hypotheses, questions for which were drawn from previous research. All of these control variables are business-specific factors that could explain the rate of innovation and/or business performance (e.g., Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004). First, the relative size of the respondent’s organization was assessed using a single item ranging from much smaller to much larger in comparison with the largest competitor (e.g., Harris, Reference Harris2001). Second, the degree to which the respondent firm’s products/services were branded/differentiated was assessed using a single item on a 7-point scale ranging from highly standardized (commodity) to highly differentiated (e.g., Deshpande & Farley, Reference Deshpande and Farley1999). Finally, the level of R&D investments made by the respondents’ firms were captured using a single 7-item scale ranging from much lower to much higher in comparison with competitors (e.g., Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004). Additionally, several background questions about the respondents’ gender, years of experience, and industry affiliation were also included.

Reliability and validity of the measures

We followed a two-step procedure for establishing the validity and the reliability of the measures used in this study. We first conducted a CFA for each of the constructs in the study. Having ascertained the goodness of fit and the respective factor structure to the corresponding items, we then tested the overall measurement model of the constructs in the study (see results in Table 1). This overall measurement model verification also serves to alleviate common method variance concerns. For addressing common method variance, we used varied response formats and clearly separated the independent (earlier) and the dependent variables (later) in terms of their positioning in the questionnaire. We also interspersed the location of multiple items pertaining to the different constructs representing independent variables in the study for the same objective. We also used two questions to measure humane orientation from GLOBE studies (see House et al., Reference House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman and Gupta2004), which is theoretically unrelated to any of the study variables to verify that in fact these are unrelated in the study (see Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2003 for all these recommendations). As can be seen from Table 2, none of the correlations of the study variables with humane orientation are significant and some of these are negative. Perhaps most importantly, we conducted CFA of all the constructs in the study and report the results in Table 1.

Table 2 Means, SDs, correlationsFootnote a , square root of average variance extracted (AVE) of the variables

Note. The bolded values along the diagonal are the values of the Square of the Average Variance Extracted of the corresponding construct.

a All correlations above 0.15 are significant at the p<.05 level with the exception of the correlations for humane orientation.

b None of the correlations for ‘humane orientation’ are significant (this variable has a different pairwise n because it was used in the questionnaire at only one of the two sites).

NPD=new product development.

The results in Table 1 suggest that the measurement of the study constructs provides high degrees of convergent and discriminant validity, in addition to providing an excellent fit to the data. All of the fit indices are highly acceptable (comparative fit index (CFI)=0.95; incremental fit index (IFI)=0.96; normed fit index (NFI)=0.92; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)=0.07) (Williams, Vandenbergh, & Edwards, Reference Uygur2009), permitting us to proceed with further analysis. We present the average variance extracted, construct reliability, and factor loadings for the constructs and the relevant items in Table 1. Acceptable levels of convergent validity are indicated by the higher than threshold values for average variance extracted (the lowest is 0.61 for two constructs) for all the constructs. We followed Fornell and Larcker’s (Reference Fornell and Larcker1981) method to establish discriminant validity by comparing the square root of the average variance extracted of each of the latent factors with the cross-construct correlations in Table 2. The square root of the average variance extracted is higher than the corresponding cross-construct correlations in every instance in Table 2, suggesting that constructs in this study have more internal variance than that shared with other constructs, indicating discriminant validity. A look at the factor loadings suggests that the lowest is at 0.67, thereby also giving us confidence in the measurement approach used in this study. All of this suggests that the measurement approach used in this study is strong and that common method variance does not account for our results.

Results of the structural model

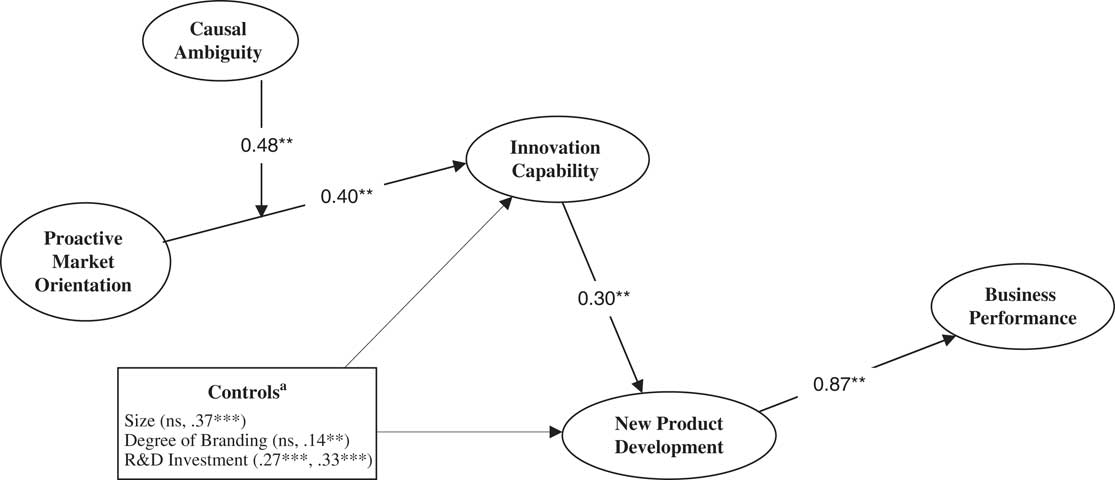

We tested the hypotheses through tests of the structural relationships using AMOS 18 package of SPSS (results in Figure 2) as explained here. First, for the theoretical model in Figure 1, we modelled proactive market orientation as a latent exogenous construct, represented by the indicators identified in the earlier CFA in Table 1. Additionally, we modelled innovation capability, NPD, and business performance as latent endogenous constructs, represented by their corresponding indicators from the earlier CFA. Finally, we modelled three control variables (organizational size, degree of branding, R&D investment), and a product term representing the interaction between proactive market orientation and causal ambiguity as observed exogenous variables (Aiken & West, Reference Ambrosini and Bowman1991; Williams, Vandenbergh, & Edwards, Reference Uygur2009).

Figure 2 Structural test of the proactive market orientation model Note. Fit indices for model: χ2 =365.01, p<.01; CMIN/df=2.43; CFI=0.94, IFI=0.94, NFI=0.90, RMSEA=0.08. aThe first parameter in parentheses after the name of the control variable refers to the effect on innovation capability and the second refers to the corresponding effect on new product development (NPD); **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. ns=non significant.

Proactive market orientation

We report the results of the test of the theoretical model in Figure 1 and display it graphically in Figure 2. The results in Figure 2 provide an excellent fit to the data (χ2=365.01, p<.01; calls the Chi-Square statistic (CMIN)/df=2.43; CFI=0.94, IFI=0.94, NFI=0.90, RMSEA=0.08) (Williams, Vandenbergh, & Edwards, Reference Uygur2009) with all of the fit indices in the acceptable range. All of the hypotheses are supported while controlling for relative size, degree of branding, and level of R&D investments, as explained below. First, in support of Hypothesis 1, proactive market orientation is positively and significantly related to innovation capability (β=0.40, p<.01). Next, as predicted in Hypothesis 2, the interaction between causal ambiguity and proactive market orientation is significant (β=0.48, p<.01) and in the expected direction. In support of Hypothesis 3, the relationship between innovation capability and NPD is positive and significant (β=0.30, p<.01). A number of elements indicate support for the mediation effect in Hypothesis 4. First, the relationship between NPD and business performance in this model is positive and significant (β=0.87, p<.01). Second, alternative model specifications with direct paths from innovation capability and/or proactive market orientation to business performance result in inferior fit and nonsignificant paths. Thus, the effect of proactive market orientation on business performance is mediated by innovation (i.e., innovation capability and NPD success).

Discussion

Our results provide strong support for the importance of proactive market orientation for innovation and subsequently for business performance in the context of an emerging market such as India. Our main contribution to the literature is the theoretical development and identification of the moderating impact of a critical construct drawn from the RBV of the firm (e.g., Barney, Reference Barney1991), that is, intrafirm causal ambiguity (e.g., King, Reference King2007). Causal ambiguity has been identified earlier as a critical construct in studies of knowledge transfer (Szulanski, Reference Szulanski1996; Szulanski, Cappetta, & Jensen, Reference Szulanski, Cappetta and Jensen2004). Despite noting the importance of organizational learning and organizational resources, the market orientation literature has not conceptualized internal organizational characteristics that can either facilitate or inhibit effective implementation of market orientation (Slater & Narver, Reference Slater and Narver1995). Following calls in the literature for examining internal organizational factors as moderators (e.g., Atuahene-Gima, Slater, & Olson, Reference Atuahene‐Gima, Slater and Olson2005), we have successfully identified, theoretically conceptualized, and empirically demonstrated how and why intrafirm causal ambiguity moderates processes of proactive market orientation leading to crucial innovation outcomes. In this context, our conceptualization of the moderating impact of intrafirm causal ambiguity on the relationship between market orientation and business performance through innovation is a crucial theoretical contribution. Market orientation makes demands on the entire range of learning and knowledge processes in the organization for customer orientation, competitor orientation, and interfunctional coordination in generating a response to the market. Although factors such as strategic consensus and mission rigidity have been investigated in prior research (Atuahene-Gima, Slater, & Olson, Reference Atuahene‐Gima, Slater and Olson2005), such studies are rare. More importantly, researchers have not leveraged the organizational learning and resource-based literatures to identify critically appropriate moderators to examine in this context, as we have done here. We identified intrafirm causal ambiguity as it is a core construct in the RBV of the firm, in addition to the specific role it plays in knowledge transfer.

Our findings suggest that intrafirm causal ambiguity is a crucial moderator for proactive market orientation, as it depends on organizational learning mechanisms of intelligence generation and diffusion (Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008). Thus, it is critical that middle managers, in addition to top managers, in market-oriented organizations have a clear idea of the organizational systems and culture required to be innovative (Tyler & Gnyawali, Reference Tyler and Gnyawali2009; Uygur, Reference Williams, Vandenbergh and Edwards2013). Additionally, our findings also suggest that cause-effect beliefs of middle managers need to be convergent with those of top managers to effectively harness the capabilities of proactive market orientation in achieving innovation that contributes to sustainable competitive advantage (Greenley, Reference Greenley1995). While it is important to have low levels of intrafirm causal ambiguity, it is equally important to have high levels of interfirm causal ambiguity. RBVs of the firm indicate that it is a high level of interfirm causal ambiguity (King, Reference King2007) that protects innovations and prevents competitors from easily replicating the initiatives of focal firms (Barney, Reference Barney1991). In the context of market orientation, this suggests that proactive market orientation requires the fine tuning of a number of internal organizational factors (Ketchen, Hult, & Slater, Reference Jain and Bhatia2007) to effectively convert potential resources into capabilities, while also reducing the level of causal ambiguity (Lakshman, Reference Lakshman2011) before it can succeed. Additionally, these efforts have to be augmented with those seeking to increase interfirm causal ambiguity to leverage rent-seeking opportunities (Ambrosini & Bowman, Reference Aiken and West2010) from innovative products and services.

Next, although there are questions about the applicability of the market orientation construct in emerging markets, our study provides results that are consistent with those from advanced economies. Our study and the results herein contribute to the literature on market orientation by providing evidence from India, where few studies exist in this regard. Specifically, our sample of predominantly service firms suggests that the concept of market orientation contributes to business performance in this market context as much as it does in the case of manufacturing firms (Jain & Bhatia, Reference Jaworski and Kohli2007)Footnote 1 . Additionally, despite suggestions in previous research (e.g., Pelham, Reference Pelham1997) that market orientation could be less significant in markets dependent on cost advantages rather than innovation (differentiation) advantages (e.g., India as typically conceived), we provide evidence in this country for the strong role of proactive market orientation. This suggests that India and the markets therein are no longer dependent on cost-cutting strategies, and economies of scale as typically conceived (e.g., Aulakh, Kotabe, & Teegen, Reference Aulakh, Kotabe and Teegen2000) but that it is increasingly important for firms to innovate and differentiate in India (e.g., Chittoor et al., Reference Chittoor, Sarkar, Ray and Aulakh2009). Since the liberalization of the 1990s, India has gone through significant institutional changes and organizational transformation (e.g., Chittoor et al., Reference Chittoor, Sarkar, Ray and Aulakh2009), with the business environment becoming more competitively intense. Proactive market orientation plays an increasingly important role under conditions of high competitive intensity, as is generally suggested in the literature (e.g., Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Subramanian and Yauger2011) and as confirmed empirically by our study in India.

Our results also contribute to the stream of literature on market orientation that focusses on innovation and NPD (e.g., Narver, Slater, & Maclachlan, Reference Narver, Slater and MacLachlan2004; Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008) rather than simply on sales and profitability (e.g., Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Subramanian and Yauger2011). Consistent with this innovation-focussed literature stream, we find that proactive market orientation is important for business performance only through the mediating variable of innovation through NPD. From this perspective, although this can be viewed simplistically as just a cost of doing business to avoid failure (e.g., Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Subramanian and Yauger2011), it goes much beyond this and provides a real (innovation) base of sustainable competitive advantage.

Managerial and research implications

We have successfully validated (using CFA) a measure of proactive market orientation in the Indian context, with a sample of predominantly service firms. Researchers can now explore more in-depth relations between formalization, centralization, and market-based rewards as suitable antecedents, using this validated measure. It is noteworthy that our measure of proactive market orientation follows the conceptualization of market orientation as a process of intelligence generation and use (e.g., Kohli & Jaworski, Reference Kohli and Jaworski1990). Following the literature’s (Slater & Narver, Reference Slater and Narver1995; Ketchen, Hult, & Slater, Reference Jain and Bhatia2007) conceptualization and suggestion that market orientation represents strategic resources dependent on processes of organizational learning for effective conversion to capabilities, we drew from the resource-based theory of the firm in examining the impact of intrafirm causal ambiguity as a relevant moderator. Future research can examine other constructs from this theoretical framework by examining their direct and moderating impacts. Perhaps it is time to include the VRIN (Valuable, Rare, Inimitable, Nonsubstitutable) framework of resources discussed by Barney (Reference Barney1991) in deeper investigations of the role of resources in studies of market orientation (Lee & Chu, Reference Lee and Chu2013).

Managers can benefit from a broader knowledge of the organizational (discussed above) and cultural factors facilitating market orientation in its implementation (e.g., Tyler & Gnyawali, Reference Tyler and Gnyawali2009). Managers in India (or of MNCs operating in India) would do well to focus on innovation and the success of NPD as the means through which market orientation achieves business performance. In creating innovation capability, managers should ensure that they take a balanced approach to knowledge pertaining to expressed (market-pull) versus latent (technology-push) needs. The resulting base of balanced knowledge should then be shared and leveraged with other organizational members. In the sharing and leveraging of this knowledge base, managers should pay special attention to the varying levels of causal ambiguity within the organization. More specifically, managers need to pay specific attention to eliminating intrafirm causal ambiguity at the middle levels to profit more from market orientation efforts (King, Reference King2007; Lakshman, Reference Lakshman2011). Specifically, our findings suggest that organizations need to develop leaders with high levels of cause-effect beliefs and engage their leadership in reducing causal ambiguity (Lakshman, Reference Lakshman2011) among middle managers in particular. Managers should also focus specifically on new products/services directly targeted towards expressed needs vis-à-vis those targeted towards latent needs in confirming that they have indeed used a balanced approach in creating their innovation capability.

Limitations and future research directions

The analysis in the study is based on managers’ perceptions of their firms’ proactive market orientation. But as Deshpande, Farley, and Webster (Reference Deshpande, Farley and Webster1993) point out, apart from the management’s own assessment, customers’ evaluation of the organization’s customer focus should be assessed and linked to business performance measures. However, internal observers such as managers are perhaps the best for intelligence generation and use measures. Thus, despite this limitation of a possibly biased measure of customer focus, our study provides relatively strong evidence. Our use of subjective measures sourced from single respondents could also have contributed to some level of common method variance. However, our empirical results using CFA and discriminant validity tests suggest that it is not a serious concern, but, nevertheless, a limitation to be addressed in future research.

The focus of the present study has been an examination of the consequences of market orientation. But it will be of equal interest in future research to investigate the antecedents of market orientation in the Indian context. Any such knowledge can be of great help to managers interested in organizational factors involved in the role of strategic orientation in improving business performance. Our study has also laid the foundation for possible future investigations of the details of innovation in service contexts, in a manner different from manufacturing contexts alluded to in the literature. Future studies could distinguish between exploitative and exploratory innovation (e.g., Atuahene-Gima, Slater, & Olson, Reference Atuahene‐Gima, Slater and Olson2005; Morgan & Berthon, Reference Morgan and Berthon2008) in service contexts and separately study the moderating role of causal ambiguity within each. With India increasingly being considered as a country with a competitive advantage in services (e.g., Kapur & Ramamurti, Reference Ketchen, Hult and Slater2001), such investigations would yield more managerially relevant knowledge in this domain.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the editor and reviewers for their insightful feedback on previous versions of the manuscript.