Introduction

This study seeks to understand the specific resource needs of international entrepreneurs (IEs) and their perceptions and expectations of bureaucratic networks as resource providers. Our focus is on government and industry networks because studies suggest that these networks are key resource providers for entrepreneurial firms to enter international markets (Von Nordenflycht, Reference Von Nordenflycht2010; Leonidou, Palihawadana, & Theodosiou, Reference Leonidou, Palihawadana and Theodosiou2011). Bureaucratic networks typically refer to government networks whose main tasks include implementing public policies and service delivery of government resources (Gains, Reference Gains2003; Bach, Niklasson, & Painter, Reference Bach, Niklasson and Painter2012). Other scholars also regard professional and industry associations as bureaucratic networks as these associations provide common services to coordinate and benefit large numbers of firms (Grandori & Soda, Reference Grandori and Soda1995: 201).

Many entrepreneurs use internationalisation as an organisational growth strategy and with this strategy comes distinct challenges and constraints (Hutchinson & Xavier, Reference Hutchinson and Xavier2006; Malo & Norus, Reference Malo and Norus2009). Many of these challenges and constraints are exacerbated by resource limitations, particularly for entrepreneurial organisations (Ahuja & Lampert, Reference Ahuja and Lampert2001; Sui & Baum, Reference Sui and Baum2014) and the ability to acquire, orchestrate and manage resources is crucial to the growth of their ventures in international markets (Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik2003; Penrose, Reference Penrose2009). Pfeffer and Salancik’s (Reference Pfeffer and Salancik2003: 19) resource dependency theory posit that ‘…no organisation is completely self-contained or in complete control of the conditions of its own existence…’, suggesting that organisations depend on external sources to fill resource gaps. External networks are one such means for entrepreneurs to alleviate resource constraints (Birley, Reference Birley1985; Jarillo, Reference Jarillo1989). We define networks as sets ‘of actors and some set of relationships that link them’ (Hoang & Antoncic, Reference Hoang and Antoncic2003: 167). Cultivating a diverse set of social and business networks is crucial as each network brings different types of resources.

A network approach to internationalisation emphasises relationships and linkages in the internationalisation process (Johanson & Vahlne, Reference Johanson and Vahlne1992). Studies suggest that a network approach to internationalisation is particularly relevant to resource-poor entrepreneurs as potential network resources are available with less capital and less risks (Varis, Kuivalainen, & Saarenketa, Reference Varis, Kuivalainen and Saarenketa2005; Slotte-Kock & Coviello, Reference Slotte-Kock and Coviello2010). Internationalisation studies also show that network relations provide access to resource opportunities which would otherwise not be available (Vasilchenko & Morrish, Reference Vasilchenko and Morrish2011; Newbert, Tornikoski, & Quigley, Reference Newbert, Tornikoski and Quigley2013). For small entrepreneurial organisations, network relationships are particularly instrumental as these relationships affect entry mode decisions and speed of internationalisation (Coviello & Munro, Reference Coviello and Munro1997; Chetty & Holm, Reference Chetty and Holm2000). Actors in business networks are typically goal-oriented and ties are established for purposes of mutual exchange, problem solving and other cooperative strategies. The instrumental role of these business networks of suppliers, customers, distributors and competitors is a frequent focus of study in internationalisation literature (Chetty & Wilson, Reference Chetty and Wilson2003; Ellis, Reference Ellis2011). Equally, research shows that in addition to business networks, bureaucratic networks comprising government agencies, industry and professional associations are also key resource providers (Grandori & Soda, Reference Grandori and Soda1995; Gains, Reference Gains2003; Bach, Niklasson, & Painter, Reference Bach, Niklasson and Painter2012). Unlike business networks where ties are typically formed based on mutual exchange of resources (Ellis, Reference Ellis2011), IEs tend to view bureaucratic networks from a resource-based view whereby bureaucratic networks are seen as resource providers and IEs as receivers (Leonidou, Palihawadana, & Theodosiou, Reference Leonidou, Palihawadana and Theodosiou2011; Battisti & Perry, Reference Battisti and Perry2015). Studies suggest that, compared with business networks, bureaucratic networks provide different types of business resources that are embedded within the organisations’ operations. For example, government agencies are particularly helpful for entrepreneurs at early stages of internationalisation with the provision of financial, information and knowledge resources (Leonidou, Palihawadana, & Theodosiou, Reference Leonidou, Palihawadana and Theodosiou2011; Martincus, Carballo, & Garcia, Reference Martincus, Carballo and Garcia2012). Studies on industry associations provide evidence of resource opportunities, such as diffusion of knowledge and innovation (Maennig & Ölschläger, Reference Maennig and Ölschläger2011; Newbery, Gorton, Phillipson, & Atterton, Reference Newbery, Gorton, Phillipson and Atterton2015), connecting with other organisations in the same industry and accessing mentoring programmes (Ozgen & Baron, Reference Ozgen and Baron2007; Von Nordenflycht, Reference Von Nordenflycht2010).

Indeed, many of these bureaucratic networks see their roles as resource and service providers to facilitate resource-constrained entrepreneurs to pursue international markets. Many studies indicate that bureaucratic promotion programmes augment IEs resources and capabilities in facilitating their initial entry, and subsequent expansion to, international markets (Wilkinson & Brouthers, Reference Wilkinson and Brouthers2006; Lederman, Olarreaga, & Payton, Reference Lederman, Olarreaga and Payton2010). But despite the resources behind these programmes, some studies indicate reluctance of IEs to take advantage of resources from bureaucratic networks. For example, Neergaard and Ulhoi’s (Reference Neergaard and Ulhoi2006: 1) study finds that government initiatives of forming business networks to assist small businesses may in fact, ‘unintentionally destroy existing, well-functioning inter-organisational cooperative arrangements’, thus fostering both a mistrust and negative perception of government programmes based on the efforts required to engage with them (Gençtürk & Kotabe, Reference Gençtürk and Kotabe2001). These results suggest the need for a deeper understanding of why IEs are not making the most of the resources that are specifically designed to facilitate their plans for internationalisation. Furthermore, while the role of business networks is frequently examined in entrepreneurship and internationalisation literature, such is not the case for bureaucratic networks. This seems quite perplexing as many bureaucratic networks are typically set up to provide services and opportunities for resource-constrained entrepreneurs and IEs (Bennett & Ramsden, Reference Bennett and Ramsden2007; Wincent, Reference Wincent2008). We suggest this gap merits attention and as such, we approach this study with two key research questions: (1) From an internationalisation perspective, what are the resource needs of IEs at pre-entry and postentry stages? and (2) How do IEs perceive the role of bureaucratic networks as resource providers in their pursuit of international markets?

To address our research questions, we conduct in-depth, face-to-face interviews with entrepreneurs/CEOs in the Australian health and medical industry. The medical industry provides the context of our study as it is science-intensive, knowledge-based and typically R&D-driven (Powell, White, Koput, & Owen-Smith, Reference Powell, White, Koput and Owen-Smith2005; Stuart & Ding, Reference Stuart and Ding2006). These characteristics predispose IEs within the industry to seek networks as a means to fill resource gaps, particularly in areas of knowledge, new technology, skills and experience (Almeida, Hohberger, & Parada, Reference Almeida, Hohberger and Parada2011).

We begin the next section with a background of the theoretical underpinnings of this study. We then present an overview of the qualitative research method used before discussing our results and proposing several propositions based on our analysis of the data. A concluding section follows that discusses the limitations of our study and suggests areas for further research.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Resources and IEs

Resources drive an organisation’s capacity to evolve and grow. These resources are either inherited or have to be acquired from external sources (Penrose, Reference Penrose1960: 2). Resource-based views of organisations suggest that resources can be classified as financial, physical, human, technical, reputational and organisational (Grant, Reference Grant1991; Barney, Wright, & Ketchen, Reference Barney, Wright and Ketchen2001; Penrose, Reference Penrose2009). Studies suggest that in an internationalisation context, resources that are particularly relevant to IEs are, (1) entrepreneurial, (2) relational, (3) knowledge and (4) information (Vasilchenko & Morrish, Reference Vasilchenko and Morrish2011; Fletcher, Harris, & Richey, Reference Fletcher, Harris and Richey2013; Child & Hsieh, Reference Child and Hsieh2014).

Entrepreneurial resources are the creativity, tenacity and value-creation skills that IEs bring to their new ventures. Entrepreneurs do more than merely respond to market challenges, many of them create change (Jacobides & Winter, Reference Jacobides and Winter2007; Kor, Mahoney, & Michael, Reference Kor, Mahoney and Michael2007). While characteristically lacking financial resources, entrepreneurs typically possess ideas and the ability to convince others. Wealth and value are desired outputs of these entrepreneurial resources (Alvarez & Busenitz, Reference Alvarez and Busenitz2001; Kor, Mahoney, & Michael, Reference Kor, Mahoney and Michael2007). Relational resources include the IE’s network of relationships which provides crucial resources that open many opportunities, such as entering international markets (Mort & Weerawardena, Reference Mort and Weerawardena2006; Kontinen & Ojala, Reference Kontinen and Ojala2011; Bangara, Freeman, & Schroder, Reference Bangara, Freeman and Schroder2012) and cooperative arrangements in operating various marketing functions such as distribution and logistics (Nyaga, Whippleb, & Lynch, Reference Nyaga, Whippleb and Lynch2010; Zacharia, Nix, & Lusch, Reference Zacharia, Nix and Lusch2011). These network relationships provide links to two other crucial resources: information and knowledge. Compared with knowledge resources, information resources refer primarily to facts which are codifiable and easily communicated (Vasilchenko & Morrish, Reference Vasilchenko and Morrish2011). Child and Hsieh (Reference Child and Hsieh2014: 5) define information as ‘data that are structured and understood in a way so as to become a useful input into knowledge… knowledge comprises information …as a basis for taking action’.

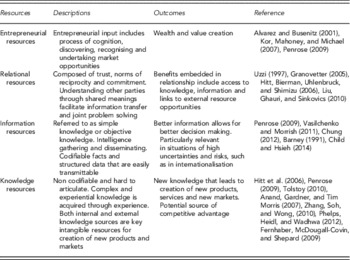

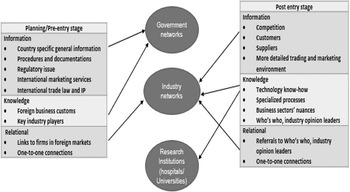

Murray and Peyrefitte (Reference Murray and Peyrefitte2007) regard knowledge as the most important resource of an organisation. Knowledge is often described as experiential or tacit, as it entails accumulated expertise and skills which are typically noncodifiable. Knowledge synthesises and combines with other resources to create competitive advantages (Tolstoy, Reference Tolstoy2010; Zhang, Soh, & Wong, Reference Zhang, Soh and Wong2010; Phelps, Heidl, & Wadhwa, Reference Phelps, Heidl and Wadhwa2012). In an internationalisation context, knowledge is a combination of ‘procedures and routines for how to learn in local markets’ (Blomstermo, Erikssona, Lindstrand, & Sharma, Reference Blomstermo, Erikssona, Lindstrand and Sharma2004: 358), including experiential knowledge gained from network relational resources which are crucial for business development. Some scholars suggest that at pre-entry stage, information resources are most critical – for example, IEs need to have a thorough understanding of the business operations, industry norms, customers characteristics, procedures and routines of different countries (Blomstermo et al., Reference Blomstermo, Erikssona, Lindstrand and Sharma2004; Prashantham & Young, Reference Prashantham and Young2011). Furthermore, to enable effective evaluations of market entry options, IEs require information and access to international business connections (Fletcher, Harris, & Richey, Reference Fletcher, Harris and Richey2013). At postentry stage, more tacit and experiential knowledge is needed to guide localisation strategies in foreign markets (Fletcher, Harris, & Richey, Reference Fletcher, Harris and Richey2013). Studies further suggest that after entering foreign markets, experiential knowledge and relational resources such as network links, are critical to market expansion (Tolstoy, Reference Tolstoy2010, Reference Tolstoy2014). Table 1 summarises the discussion on the four particularly relevant resources for IEs.

Table 1 International entrepreneur and resources

For resource-constrained entrepreneurs seeking to pursue international markets, networks help to ‘identify international opportunities, establish credibility and often lead to strategic alliances and other cooperative strategies’ (Oviatt & McDougall, Reference Oviatt and McDougall2005: 540). Many studies on the instrumental role of business networks as resource opportunities for IEs are grounded in social exchange theory whereby actors engage in mutually beneficial exchange of tangible and intangible resources, such as tacit knowledge between buyer and supplier (Díez-Vial & Fernández-Olmos, Reference Díez-Vial and Fernández-Olmos2013), information between manufacturer and distributor (Vázquez-Casielles, Iglesias, & Varela-Neira, Reference Vázquez-Casielles, Iglesias and Varela-Neira2013) and even collaborative exchanges with competitors (Chetty & Wilson, Reference Chetty and Wilson2003). These relational resources from business networks add richness and diversity to pre-existing relational ties of the IEs and provide expanded links to resource opportunities. In the case of bureaucratic networks however, these networks are often seen as opportunities to fill resource gaps rather than opportunities to create mutually beneficial exchanges (Penrose, Reference Penrose2009).

Government and industry networks as resource opportunities for IEs

For the purpose of our study, government networks include government agencies such as federal, state and local publicly funded bodies designed to promote international trade activities with a particular focus on assisting small- and medium-sized enterprises to internationalise (Leonidou, Palihawadana, & Theodosiou, Reference Leonidou, Palihawadana and Theodosiou2011; Martincus, Carballo, & Garcia, Reference Martincus, Carballo and Garcia2012). Industry networks are typically nongovernment networks and include an array of industry, professional and trade associations as well as chambers of commerce. Many of these are sector and/or profession specific and all operate on the basis of providing social, economic and business opportunities to their members (Bennett & Ramsden, Reference Bennett and Ramsden2007; Maennig & Ölschläger, Reference Maennig and Ölschläger2011). Industry networks are often described as intermediating agencies as they directly and indirectly encourage diffusion of information and innovation (Belso-Martínez, Reference Belso-Martínez2006; Dickson & Arcodia, Reference Dickson and Arcodia2010).

Government networks provide financial as well as information and knowledge resources in the form of export incentives, training and seminars, subsidised international trade exhibitions (Leonidou, Palihawadana, & Theodosiou, Reference Leonidou, Palihawadana and Theodosiou2011; Martincus, Carballo, & Garcia, Reference Martincus, Carballo and Garcia2012) and export grants to encourage country of origin marketing (Austrade, 2013). According to Gencturk and Kotabe (2001: 51), governments are the ‘largest producers of external information’ and their most important role is ‘in providing local firms with information necessary to enhance their global competitiveness’. Trade exhibitions form one of the main sources of information for many small entrepreneurial and family businesses (Kontinen & Ojala, Reference Kontinen and Ojala2011). There are also some aspects of financial assistance as most government-organised trade exhibitions are financially subsidised. In a study of 31 firms in the Lammhult Cluster in Sweden, Ramirez-Pasillas (Reference Ramirez-Pasillas2010) find that international trade fairs enable local and transnational relations to make connections, thus facilitating access to information. Although studies suggest that smaller firms seem to benefit more from government export programmes (Leonidou, Palihawadana, & Theodosiou, Reference Leonidou, Palihawadana and Theodosiou2011; Martincus, Carballo, & Garcia, Reference Martincus, Carballo and Garcia2012), others have questioned the effectiveness of these programmes (Neergaard & Ulhoi, Reference Neergaard and Ulhoi2006). Some research suggests that government networks tend to be bureaucratic (Dean, Holmes, & Smith, Reference Dean, Holmes and Smith1997; Lederman, Olarreaga, & Payton, Reference Lederman, Olarreaga and Payton2010) and that this bureaucracy discourages participation by smaller entrepreneurial firms where the cost of exporting is not recouped by the perceived savings in using resources from government (Gençtürk & Kotabe, Reference Gençtürk and Kotabe2001). Others indicate that general export information are readily available from various public sources, such as websites, thus negating the information-provider role of government networks (Seringhaus & Botschen, Reference Seringhaus and Botschen1991; Loane & Bell, Reference Loane and Bell2006).

The roles of industry networks are variously described as: providing information, acting as regulatory agents and providing members with opportunities to interact and collectively represent themselves (Greenwood, Hinings, & Suddaby, Reference Greenwood, Hinings and Suddaby2002). Industry networks play important roles in monitoring compliance with various normative and coercive expectations (Oliver, Reference Oliver1997; Gruen, Summers, & Acito, Reference Gruen, Summers and Acito2000) and facilitate mentoring programmes for their members. For example, in Ozgen and Baron’s (Reference Ozgen and Baron2007) survey of 200 new IT companies, the authors find that nascent entrepreneurs benefit from participation in professional forums. Industry networks create business opportunities among members (Dickson & Arcodia, Reference Dickson and Arcodia2010) and facilitate innovation diffusion as these networks ‘indirectly encourage innovation diffusion through the establishment of weak ties’ (Swan & Newell, Reference Swan and Newell1995: 850). Furthermore, the authors suggest that industry networks encourage collaborative links among industry members by creating many weak ties that present greater opportunities to gain novel information (Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1973). Innovation diffusion can only work when knowledge is imparted and shared with members and, according to Swan and Newell (Reference Swan and Newell1995), industry networks play a particularly positive role in this respect. Such networks can also retard diffusion of knowledge and innovations (Cavazosa & Szyliowicz, Reference Cavazosa and Szyliowicz2011). For example, in two qualitative studies of the UK health segment, Ferlie, Fitzgerald, Wood, and Hawkins (Reference Ferlie, Fitzgerald, Wood and Hawkins2005) find that strong social and cognitive boundaries among members, such as professional and cultural differences, can inhibit diffusion. In an internationalisation context, industry networks can provide a powerful voice in representing the industry as well as lobbying for trade advantages as demonstrated by Bennett and Ramsden’s (Reference Bennett and Ramsden2007) study of UK firms trying to enter the EU market.

In summary, organisation growth is clearly dependent on a stream of resources that are either inherited or have to be acquired. Internationalisation studies suggest that from the perspective of pursuing international markets, the four key resources of entrepreneurial inputs, relational links, knowledge and information are particularly instrumental for effective entry to international markets. The ‘inherited resources’ of an entrepreneurial firm are typically brought in by the entrepreneur, such as pre-existing information, knowledge, relational ties and skills in decision making and active orchestration of resources. As no firm is self-sufficient, active orchestration of resources implies active pursuit of resources from the external environment, such as business and bureaucratic networks (Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik2003). This study focusses on bureaucratic networks of government agencies and industry associations. Our theoretical background indicates the contribution of bureaucratic networks as external resource providers for IEs. Equally, studies also indicate that these networks are not viewed positively by many IEs as resource opportunities. Given these contrasting findings, we examine the specific resources sought by IEs and explore IEs’ perceptions and expectations of bureaucratic networks as providers of resources needed in the pursuit of international markets.

METHOD

This research adopts a qualitative approach as the aim is to build on existing knowledge and to interpret information within a real life context (Yin, Reference Yin2010). A qualitative approach encourages an open and flexible investigation to be conducted with the aim of developing new insights. Importantly, the researcher should not be bound by any preconceived expectations or exclude any variables from the beginning of the research. Qualitative work acquires richer insights by stressing the situational contexts of an investigation (Denzin & Lincoln, Reference Denzin and Lincoln2008). As such, a qualitative approach allows scholars to explore, describe, explain and understand phenomena of complex interrelationships within dynamic environments such as those faced by resource-constrained entrepreneurs as they pursue international markets (Coviello, Reference Coviello2005).

Doz (Reference Doz2011) notes that qualitative research is uniquely suited to explaining organisational processes and answering questions of ‘how’, ‘who’ and ‘why’ individuals and organisations take action. Our unit of study is the decision maker in the organisation, who in our case, is the IE and owner/CEO. The IE is an individual who combines ‘innovative, proactive and risk-seeking behaviour that crosses national borders and is intended to create value in organisations’ (McDougall & Oviatt, Reference McDougall and Oviatt2000: 903). Gaining the perspectives of IEs is particularly relevant for the current research where the entrepreneur has a pivotal role in determining the resources required for a firm’s internationalisation. Face-to-face interviews provide a suitable approach in studying and understanding the ways IEs go about addressing the shortcomings of their organisations and enables the researcher to interact, empathise and interpret the individual viewpoint of respondents (Bryman & Burgess, Reference Bryman and Burgess2002).

Data collection

With the Australian health and medical industry being the research context, data collection started with an analysis of member organisations listed in the online directories of Health and Medical products (Austrade, 2011a), Health and Wellbeing products (Austrade, 2011b) and the Complementary Healthcare Council website (CHC, 2011). We merged the three online sources to ensure no duplication of organisations as some organisations are registered on all three online directories. From the merged data set, we identified manufacturers of health and medical products as this segment has more potential to internationalise compared with services, retail and practitioner segments. Based on a purposive and convenient sample selection (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994), eight entrepreneurs/CEOs were chosen for this study. The selection was based on several criteria. First, participants’ organisations had to be Australian owned and operated. This helped to eliminate the potential bias of better resourced multinational organisations and/or their Australian subsidiaries. Second, their products had to be registered with the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (ATGA) as this qualifies their health product classification (ATGA, 2011). Third, the organisations had to have already entered international markets. Finally, the interview participant had to be the founder, owner and/or senior decision maker of the organisation. This is an important criterion as internationalisation strategies, in view of inherent uncertainties and potentially risky investments, requires top-level decision making (Schweizer, Reference Schweizer2012; Jansen, Curseu, Vermeulen, Geurts, & Gibcus, Reference Jansen, Curseu, Vermeulen, Geurts and Gibcus2013).

Initial contact with participants was by phone, followed by emails to confirm participation and arrangement of interview time. Semi-structured face-to-face interviews were conducted. As internationalisation can occur over a continuous period, the semi structured interview is an appropriate methodology as it allows for guided, concentrated, focussed and open-ended communication with interviewees (Crabtree & Miller, Reference Crabtree and Miller1992; Freeman & Cavusgil, Reference Freeman and Cavusgil2007). Schweizer (Reference Schweizer2005: 1055) further highlights that semi-structured interviews with company representatives can obtain an appropriate degree of comparability and allow ample opportunity for unobstructed narration. This study used open-ended questions with each interview lasting around 1 hr and 45 min. Interviews spanned each firm’s initial internationalisation process, their resource constraints and opportunities and their reliance and perceptions of both government and industry networks as resource providers. All interviews were recorded and extensive notes were also taken. Follow-up phone calls and emails took place to verify and expand on data collected. In total, close to 17 hr of face-to-face interviews were recorded together with 18 phone conversations and 23 emails pertaining to data collection. To reduce subjective bias, triangulation of results was achieved by cross-checking factual information from interviews against key secondary sources (i.e., company brochures, newsletters and websites, annual reports and relevant industry publications).

The chief investigator, and lead author of this study, undertook two verbatim transcriptions of the interviews while the remaining six were contracted to a professional transcriber. All verbatim transcriptions were cross-checked by the chief investigator with audio recordings. A summary of the interviews, supplemented with data from emails, phone calls, participants’ company newsletters and websites, was prepared and emailed to each participant for data verification (Flick, Reference Flick2008).

Data analysis

All transcribed interviews together with other data sources such as interview and phone conversation notes, information from websites, brochures and company write-ups were imported into NVivo 10 software (QSR, 2012) to assist in analysis of qualitative data. The qualitative analysis employed a process of interpreting the data, by moving continually back and forth from the data to the key concepts of the research. This interactive process was critical to seeing how each theme was emerging and allowed each theme to emerge as a part of a reflective and active approach to the data sorting and categorisation.

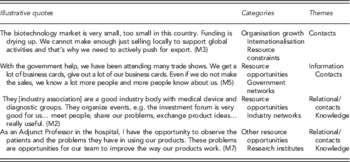

A recursive exercise of data coding, categorising and abstracting (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994; Spiggle, Reference Spiggle1994) was carried out to identify patterns of activities. In particular, a number of techniques were used in data analysis consistent with other qualitative studies on IEs (see Varis, Kuivalainen, & Saarenketa, Reference Varis, Kuivalainen and Saarenketa2005; Vasilchenko & Morrish, Reference Vasilchenko and Morrish2011) including the use of open, axial and selective coding (Strauss & Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998). We started with open coding, which required the data to be dissected for similarities and differences with no initial preconceptions, to establish broad categories. These included: (i) growth through internationalisation, (ii) resource opportunities and constraints in entering international markets, (iii) types of resources that are needed and/or missing, and (iv) external organisations approached by participants to seek resource advice. Axial coding required linking of categories and sub-categories to develop common themes. For example, the question ‘When seeking information and advice on international markets, who would you approach and why?’ elicited an array of responses such as ‘Our company is so small and people don’t know us and we don’t know many people’ (participant M3) and ‘… we went to government agencies as it did not cost money in the beginning…’ (participant M4). In selective coding, integration of all the categories in previous coding stages occurred around a common ‘core’. The categories were then theme coded where appropriate under Information, Knowledge and/or Relational/contacts, see Table 2. An iterative process of comparing notes from interviews, emails, phone conversations and other company printed materials was done until analytic closure was achieved (Leitch, Hill, & Harrison, Reference Leitch, Hill and Harrison2010). Thus, the analysis included open, axial and selective coding to develop the descriptive narrative.

Table 2 Categories and themes

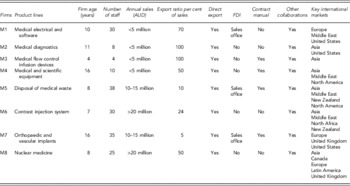

Code names identify the eight entrepreneurial founders/CEOs interviewed, M1 to M8. Company size in terms of annual sales ranges from below AUD 5 million to above AUD 20 million and number of staff ranges from three to 50 full-time employees. All eight participants are active in international markets. In addition to exports, high levels of international activities appear through cooperative alliances with networks of suppliers, distributors and other institutions. This is consistent with internationalisation literature suggesting that competitive advantages are gained not just through export sales but also through other international activities (Williamson, Reference Williamson2008; Christopher, Mena, Khan, & Yurt, Reference Christopher, Mena, Khan and Yurt2011; Golovko & Valentini, Reference Golovko and Valentini2011). Many of the participants engage in multiple entry modes as a way of diversifying risks associated with uncertainties of foreign markets (Leonidou, Reference Leonidou2004). Table 3 shows key information on participants’ organisations as well as their different modes of entry.

Table 3 Key Information on participants’ organisations

RESULTS

Growth through internationalisation

All eight interview participants stressed the need to pursue international markets in view of the small Australian market. Many also expressed that internationalisation is key to the survival of their organisations and being owner/CEO, they are instrumental in driving the internationalisation process of their organisations through their entrepreneurial vision, tenacity and decision making,

M4 – From day one, we have targeted oversea markets. Quite often it’s opportunistic and strategic. Middle East for us, is strategic, I wanted to develop this market and we spent four years developing this market! Very relationship-driven but it has worked out very well… from that one big project, many projects have followed.

Resource needs at pre and postentry to international markets

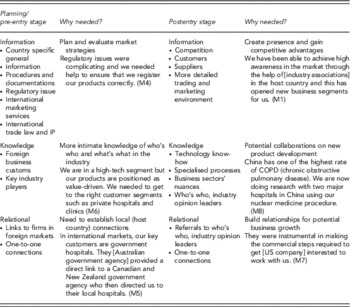

Participant IEs are very much aware of their resource limitations. From their point of view, information, knowledge and relational resources are needed before entering an international market (planning/pre-entry stage), as well as after entry to the markets (postentry stage). The differences between the two stages lie in the depth of these resources and the contextual factors involved. Table 4 details the different contextual factors of information, knowledge and relational resource at planning/pre-entry stage of their international expansion and postentry stage to international markets.

Table 4 Resources required at planning/pre-entry stage and postmarket entry stage

At planning and pre-entry stage IEs need basic information about the host country environments. At this stage, IEs feel that government networks, in view of their considerable size and depth of resources, are better able to provide general and basic information. M3 explains,

We know there are interests from US and UK but both are so different markets. We have to do a lot of research and homework. [Government website] in this case, was very useful. It even has country-specific information but they are basically, very general information.

At this information-gathering stage, government sponsored trade exhibitions are consistently well regarded as useful avenues to establish business contacts, as well as opportunities to create market presence for the IEs range of products. In this early stage, we find that knowledge and relational resources are highly inter-related. The emphasis is on seeking new ways of doing business (knowledge) and potential partners to work with (relational). At this stage, IEs are still exploring their options as M4 explains:

Our products are so technical and difficult to export. We were looking for oversea partners who understand technically what their customers want and our intention was to adapt our products to their markets.

Furthermore, IEs stressed that at this preliminary stage where there is so much uncertainty, keeping costs low is a major consideration and many see government networks as cheaper alternatives to export consultants.

At postentry stage information needs are more specific to the business and trading environment, such as working with local people and opportunities for business expansion. Participants may start with simple exports but all have intentions to expand through various degree of commitment as seen in M1’s business in United States of America:

We have been exporting our products but because the products are quite technical, a number of customers have also hired us for consulting services. Now, more than half our revenue comes from consulting work.

Similar to pre-entry stage, we find that at postentry stage knowledge and relational resources are highly interlinked. Participants continue to look for new ways to improve their products and services and at the same time, actively seek potential partners to work with. M8 reveals:

We were lucky to work with a professor and physician from [US University]. They were a team who did the first synthesis and testing of radioactivity and brain scan. We are still not selling in the US yet because of regulatory issues but their research has helped us to improve our products.

Findings also indicate that while government networks are the predominant provider of external resources at planning/pre-entry stage, a different picture emerges at the postentry stage where industry associations and research institutions such as hospitals and universities, are the predominant connections to resource opportunities. M3 emphasises the importance of professional and industry associations at home and overseas:

We have always been members in [Professional association] and [Industry association]. Firms in medical device know one another but these associations help us to meet one another. When I was looking for medical specialists in India, [Industry association] got me the contacts.

Based on IEs indication of where they seek external resources, a conceptual summary is shown in Figure 1. Research institutions of universities and hospitals are often mentioned as knowledge sources and as such, we include them in Figure 1.

Figure 1 External resource providers at pre and postentry stage

The next section analyses participants’ perceptions and experiences of both government and industry networks as resource providers.

Role of government networks: ‘Instrumental but bureaucratic’

In pursuing international markets, all participants regard government networks as their ‘first port of call’ when seeking information. Most participants regard government networks positively in terms of providing information to export markets especially at the planning stage of internationalisation where uncertainties abound. All participants have used the government export agency website and all have participated in export training and seminars. Specialised services, such as providing referrals between Australian and international organisations and government-sponsored trade exhibitions, are seen as particularly useful in promoting products as well as seeking international business connections. IEs view positively, the financial savings from participating in government-sponsored trade exhibitions. While government networks are perceived as instrumental in supporting entrepreneurs’ pursuits of international markets, some participants suggest that their experiences with government networks are not always positive. Some participants express frustration with the bureaucracy, the ‘one size fits all’ programmes, lack of specialised knowledge and the cost of services:

M4 – You know, government networks are riddled with people who mean well and want to do well, but they’re really hard to contact, they’re really expensive when they get fired up to do something, they’re really disconnected with the cut and thrust of small business. If I was a big corporate I’d go there for sure. But we’re not, we’re just an SME, ten people.

Role of industry networks: ‘Mixing with the right people’

Our empirical results indicate that industry networks are regarded as practical links to resources. All participants are members of various professional and industry associations. These associations are seen as reliable sources of up-to-date industry information and regulatory matters, as well as opportunities to mix with people in their professional community. Professional associations are particularly seen as proactive in linking small entrepreneurial firms to international investors, both venture capital and private investors. M2 explains,

I know the biotech industry is a small industry. There’re only about 300 biotech companies in Australia of various sizes and shapes and forms. So, as an industry body… there are a lot of meetings… we’re well networked within that. They [Professional association] are a good industry body and they span a medical device and diagnostics group which is growing in size and strength, so we actually span sort of both areas.

Quite often participants are members of two or three professional or industry associations. While professional-type associations are seen as more serious, even prestigious, industry-type associations tend to be viewed as more informal and friendlier as M5 explains:

I’m a councillor at [local business chamber]. Our networking sessions are very relaxed, always after office hours. Our members are mostly local so we have a lot in common. So… we get a lot of informal contacts that way, we network – that’s the way we do the network here.

Not surprising, the roles played by industry networks are more specialised in that IEs access these networks as credible conduits to industry sector knowledge and business connections. Networking programmes offered by professional and industry associations in particular are seen as linkages to potential resource opportunities. Participants regard these networks as less bureaucratic, more understanding of their needs and even more trustworthy compared with government networks as professional and industry associations are seen as supporting members’ interests.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with Penrose (2009) resource-based views, our study indicates that effective output of organisational growth is driven by entrepreneurial energy and ambition. Internationalisation as a growth strategy is no exception as it is the entrepreneur’s resources that bring the pursuit of international markets to fruition. This is shown in our findings as participant IEs have been able to internationalise their business through their entrepreneurial ambition and decision making (Lamb, Sandber, & Liesch, Reference Lamb, Sandber and Liesch2011). We set as our first research aim, the identification of specific resources that IEs seek as they plan to enter international markets, and their subsequent resource needs after entry into international markets. An array of resource needs and the scarcity of these resources are articulated by participants and guided by literature, we coded the different resources under information, knowledge and relational (Vasilchenko & Morrish, Reference Vasilchenko and Morrish2011; Fletcher, Harris, & Richey, Reference Fletcher, Harris and Richey2013) for analysis. While financing is an implicit resource requirement for any entrepreneurial growth strategy, such as in internationalisation (Grant, Reference Grant1991; Alvarez, Reference Alvarez2004), our empirical results suggest that IEs actively seek information, knowledge, and relational contacts as they pursue international markets. Thus:

Proposition 1: IEs existing relational, knowledge and informational resources are insufficient to meet their initial and subsequent global expansion needs.

At pre-entry stage to international markets, resources considered essential are information and contacts to foreign markets (Chung, Reference Chung2012; Child & Hsieh, Reference Child and Hsieh2014). At postentry stage, while information and contacts continue to be important resources, the emphasis is on host markets’ intelligence, such as working with local people and seeking new business segment opportunities. Our results reveal that at postentry stage, knowledge resources are required to better understand the industry dynamics and product needs of their host markets. In pursuing new international markets, information is crucial to decision making as it provides ‘a useful input to knowledge’ (Child & Hsieh, Reference Child and Hsieh2014: 2). In a pilot study of the internationalisation strategy of a serial entrepreneur, findings suggest that IEs are in ‘permanent information gathering mode’ (Chang & Webster, Reference Chang and Webster2012), while Chung’s (Reference Chung2012) study of 100 New Zealand exporters finds that information gathering and disseminating relate positively to market responses. Not surprising, knowledge resources are much sought after by IEs in our study who are in the science-intensive medical segment. All participants particularly seek complex and technical knowledge that provide a difference or a potential edge in developing and improving their products. This is consistent with studies where knowledge-seeking activities influence innovation outputs (Yoon, Lee, & Song, Reference Yoon, Lee and Song2015) and Phelps, Heidl, and Wadhwa (Reference Phelps, Heidl and Wadhwa2012) regard these ‘knowledge networks’ as influential in the diffusion of knowledge creations.

Relational resources, based on close relationships between parties, influence knowledge acquisition (Liu, Ghauri, & Sinkovics, Reference Liu, Ghauri and Sinkovics2010) and access to market opportunities (Loane & Bell, Reference Loane and Bell2006; Mort & Weerawardena, Reference Mort and Weerawardena2006). Our study indicates two key factors in relational resources. First, IEs extend their own relational resources, from past and present relationships, to access market opportunities, but IEs continue to seek new relational resources for future opportunities. Second, in seeking new relational resources, industry networks are the preferred channel as members perceive industry networks as more proactive and offering greater networking opportunities than government networks. Thus:

Proposition 2: During pre-entry, the requirements to control costs and reduce uncertainty drive IEs to place a greater initial reliance on government networks.

Proposition 3: Relational resources acquired through industry networks at postentry, expand and become more intertwined with foreign players and complement existing relationships developed before market entry.

Our second research aim set out to examine IEs’ perceptions and expectations of bureaucratic networks as resource providers. Our study indicates that IEs regard government networks as useful, but only at planning and pre-entry stage. IEs view positively the information resources that government networks provide (Leonidou, Palihawadana, & Theodosiou, Reference Leonidou, Palihawadana and Theodosiou2011; Martincus, Carballo, & Garcia, Reference Martincus, Carballo and Garcia2012), including government sponsored trade exhibitions which are seen as useful information-gathering avenues (Ramirez-Pasillas, Reference Ramirez-Pasillas2010; Kontinen & Ojala, Reference Kontinen and Ojala2011). Our results show these positives are negated by perceived bureaucracy of working with government networks and, thus, support past studies that indicate IEs’ indifference to government export programmes networks (Hara & Kanai, Reference Hara and Kanai1994; Gençtürk & Kotabe, Reference Gençtürk and Kotabe2001). It is logical to surmise that government networks, though better-resourced and better-funded than other networks, cannot be all things to all people. But better communications, as alluded to by participants, can improve the rate of IEs participations of the many programmes and incentives designed to assist entry to international markets. Better communications can work both ways, such that government networks can actively listen and consider IEs feedback to design more customised programmes to meet IEs resource needs.

Industry networks, while less helpful at planning and pre-entry stage, are the main external providers of resources at postentry stage. Industry networks are regarded positively as providing invaluable resources through dissemination of information and knowledge, and mentoring and networking programmes (Ozgen & Baron, Reference Ozgen and Baron2007; Dickson & Arcodia, Reference Dickson and Arcodia2010). Networking programmes are particularly relevant and the participants seek out industry networks when they need to know ‘who is who’ they can connect with to expand their international markets. Participants also see industry networks as more responsive and trustworthy than government networks, thus putting in question the inclusion of industry networks as bureaucratic networks (Grandori & Soda, Reference Grandori and Soda1995). In fact, IEs approach industry networks as these networks are seen as less rigid, more proactive and responsive to industry needs. This more positive perception of industry networks could be the result of representations that industry networks make on behalf of their members, especially in lobbying governments for better trading advantages (Bennett & Ramsden, Reference Bennett and Ramsden2007). Thus:

Proposition 4: During pre-entry, IEs positive expectations of government networks extend to the delivery of informational, relational and knowledge resources. However, their provision of relational and knowledge resources postentry is considered inadequate and is further undermined by perceptions of bureaucratic necessities and prohibitive costs.

Proposition 5: IE positive expectations of industry networks are based on their ability alone to provide the tacit and experiential knowledge resources deemed essential to guide localisation strategies of their firm(s) in foreign markets.

CONCLUSION AND CONTRIBUTION

While some of our findings do show consistency with past studies, our current research does contribute to knowledge of the resource-seeking behaviour of IEs. Specifically, we draw attention to four resources of entrepreneurial inputs, information, knowledge and relational that are particularly instrumental from an internationalisation perspective. We further expand on these resource needs to indicate that there are differences in the focus of these resource needs at planning/pre-entry stage and postentry stage. While these four resources are implicit in resource-based views theories (Grant, Reference Grant1991; Penrose, Reference Penrose2009) we highlight the relevance of these resources from an IE’s perspective as follows:

-

(1) The resources that an entrepreneur brings, such as vision, recognising opportunities, resource acquisition and the ability to make strategic decisions, can often be taken for granted. Our study emphasises that it is the entrepreneur who is instrumental in driving the internationalisation process. This is revealed in the ways the entrepreneur participants create value for their organisations by developing products and seeking new market opportunities.

-

(2) The entrepreneur participants continue to seek and establish relational resources through their engagement with different external organisations such as government and industry networks. We suggest that entrepreneurial and relational resources are crucial as they influence the acquisition of information, relationships and knowledge resources highlighting a sequential connection between the uses of the four resources.

Our study also contributes to IEs’ resource-seeking behaviour by highlighting the roles played by government and industry networks. Previous studies indicate that both these networks provide resource opportunities (Maennig & Ölschläger, Reference Maennig and Ölschläger2011; Martincus, Carballo, & Garcia, Reference Martincus, Carballo and Garcia2012). However, our current research extends this by focussing on the specific resources that each of these networks offers, such as information, knowledge and relational resources at different stages of the firms’ internationalisation. More importantly, we demonstrate that IEs approach these networks guided by their perceptions of each networks’ efficiency, measured by their responsiveness and cost, and efficacy in terms of their abilities to provide the tacit and experiential knowledge of the relevant industries.

Practical implications

Our study suggests that many opportunities remain open for government and industry networks to interact closely with IEs. Most governments are already implementing export promotion programmes to assist IEs (Ramirez-Pasillas, Reference Ramirez-Pasillas2010; Leonidou, Palihawadana, & Theodosiou, Reference Leonidou, Palihawadana and Theodosiou2011), but government networks, which tend to be better resourced, can play more instrumental roles in facilitating the growth of a knowledge-based industry segment through the funding of high level international scientific conferences and creating connection opportunities for IEs to seek international networks. In a knowledge-intensive segment such as health and medical, customised and tailored resources that provide links to knowledge and relational resources are crucial. After the first hurdle of entering international markets, IEs need support to sustain their growth in international markets. From this perspective, there are opportunities for both government and industry networks to implement programmes that focus on postentry stage. Programmes that promote the image and reputation of home country can enhance opportunities for IEs to connect with key players in host countries.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. The small sample size and the focus on a specific industry restrict the generalisability of our results. In our study, industry networks are very much focussed on professional and trade associations. In practice, industry networks also include most organisations in the same industry, for example, networks of suppliers and service providers such as consulting firms. Although we recognise these limitations, we suggest our results present interesting insights and opportunities for future research. For example, while extant studies highlight the benefits of government and industry networks for IEs (Swan & Newell, Reference Swan and Newell1995; Martincus, Carballo, & Garcia, Reference Martincus, Carballo and Garcia2012), bureaucracy and poor communications weaken the effectiveness of these benefits (Neergaard & Ulhoi, Reference Neergaard and Ulhoi2006; Lockett, Jack, & Larty, Reference Lockett, Jack and Larty2012). We suggest that another interesting strand of future research should focus on the effectiveness of communications between IEs and government and industry networks.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments and suggestions. The authors also thank Associate Editor, Dr David Tappin for his thoughtful input. Any errors remain authors’ own.