Introduction

Most commercial banks spend little time, attention, or money on internal development practices. Moreover, retaining productive and higher performing employees in commercial banks is not an easy task. For instance, lack of organizational support resulted in employee disengagement that costs $450–$550 billion in lost productivity (Karatepe & Aga, Reference Karatepe and Aga2016). The service sector is one of the most important sectors of the Jordanian economy employing about 79% of the population. Within the service sector, the banking sector is the largest employer and has the largest capital in the Amman Stock Exchange. In 2018, Jordan’s gross domestic product amounted to around $42 billion. The banking sector is a saturated market with access to advanced information technology systems and is contributing more than 28% of the gross domestic product. The change in the global business environment has led banks to rationalize their products and services, and to consider knowledge management to improve their competitiveness. Jordanian banks are faced with fierce competition; thus, the obvious desire to survive and generate revenue exists. According to Peruta, Campanella, and Del Giudice (Reference Peruta, Campanella and Del Giudice2014), lending and financial institutions are faced with constant challenges, such as a more efficient provision of services, and risk-taking involving more complex and intangible profiles.

Ultra-modern organizations choice of investments lies in intangible assets that are not easily discernable. These assets mostly rely on knowledge creation and acquisition and human resource management practices to create and maintain competitive advantage (AbdeAli & Moslemi, Reference AbdeAli and Moslemi2013). Knowledge is among the vital elements that can be utilized to create sustainable competitive advantage in an era characterized by less work role definitions and knowledge-dependent economy (Demerouti, Bakker, & Gevers, Reference Demerouti, Bakker and Gevers2015). While knowledge gathering is valuable, it is fruitless without sharing (Abubakar, Elrehail, Alatailat & Elçi, Reference Abubakar, Elrehail, Alatailat and Elçi2017); thus, the potency of knowledge can only be exploited and maximized when shared for organizational use. Sharing knowledge with coworkers may sometimes leave subject the sharer to social dilemma or uncertainty (Connelly & Zweig, Reference Connelly and Zweig2015). Although knowledge sharing is beneficial, employees are also aware of the detrimental potency of sharing, because sharing may threaten their position or relevance in the organization. As such, some employees prefer not to share their knowledge, resulting in knowledge hiding. Knowledge hiding behavior is a situation whereby employees purposefully conceal knowledge from coworkers; it occurs as a result of two major factors, namely, situational and interpersonal (Connelly, Zweig, Webster, & Trougakos, Reference Connelly, Zweig, Webster and Trougakos2012).

Perceived organizational support (POS) represents ‘assurance that aid will be available from the organization when it is needed to carry out one’s job effectively and to deal with stressful situations’ (Rhoades & Eisenberger, Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002: 698). It also delineates employees’ perception that the organization cares about their well-being and value their contributions. Henceforth, POS seems to be a situational factor that can influence employee’s attitude toward knowledge hiding and other work outcomes. Psychological entitlement refers to the portent in which employees unswervingly believe that they warrant preferential treatments and rewards, often with little consideration of reality (Harvey & Martinko, Reference Harvey and Martinko2009). Entitlement encompasses a situation of feeling entitled and deserving (Chen, Sparrow, & Cooper, Reference Chen, Sparrow and Cooper2016); this will obviously reflect on how employees may choose to share knowledge in the organization. Henceforth, psychological entitlement may serve as an interpersonal dynamic that can influence employee’s attitude toward knowledge hiding and other work outcomes.

The significance of service employee extra-role behavior during service encounter is well-recognized. Service employee’s behavior can enhance customer value, which contributes to greater competitive advantage. Thus, organizational success and competitiveness is contingent on employee’s willingness to fill the gap between explicit and implicit job requirements. Extra-role behavior is a discretionary behavior which is neither solicited nor rewarded but directly influencing organization’s outcomes. Extra-role behaviors such as employee creativity and contextual performance can enhance organizational responsiveness (Demerouti, Bakker, & Gevers, Reference Demerouti, Bakker and Gevers2015). Commercial banks are striving hard to encourage their personnel not only to accomplish their tasks but also go ‘beyond the expectations’ by engaging in extra-role behavior.

For instance, Cropanzano, Jakopec, and Molina (Reference Cropanzano, Jakopec and Molina2017) argued that employees are likely to exert discretionary behavior to assist those with whom they share a supportive relationship (i.e., coworker, supervisor, or organization). Although it is difficult to achieve, there is growing acknowledgment that employees must be motivated to share their knowledge with others (Wittenbaum, Hollingshead, & Botero, Reference Wittenbaum, Hollingshead and Botero2004; Connelly et al., Reference Connelly, Zweig, Webster and Trougakos2012). Fong, Men, Luo, and Jia (Reference Fong, Men, Luo and Jia2018) urged researchers to empirically investigate antecedents of knowledge hiding behavior. To address this challenge, researchers have focused on factors that foster knowledge sharing, ignoring those that foster knowledge hiding behavior. What is lacking in the literature is a comprehensive review that considers the combined effects of personal (i.e., psychological entitlements) and situational (i.e., POS) factors on knowledge hiding and extra-role behavior. Thus, this study combined potential fostering and hindering factors to assess their effects on bank employee’s extra-role behavior.

Theory and hypotheses

POS and extra-role behavior

According to Törner, Pousette, Larsman, and Hemlin (Reference Törner, Pousette, Larsman and Hemlin2017), ‘POS implies a shared, general apprehension of the workplace that will frame employees’ interpretations of situations in daily work, underpinned by social norms.’ POS is also an employees’ perception that the organization values their contribution and cares about their well-being (Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison, & Sowa, Reference Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison and Sowa1986). Higher POS is associated with reduced employee absenteeism, turnover intention, workplace withdrawal behavior, and positive organizational outcomes like citizenship behavior (Eder & Eisenberger, Reference Eder and Eisenberger2008; Rubel, Rimi, & Walters, Reference Rubel, Rimi and Walters2017; Mayes, Finney, Johnson, Shen, & Yi, Reference Mayes, Finney, Johnson, Shen and Yi2017; Yeniyurt, Henke, & Yalcinkaya, Reference Yeniyurt, Henke and Yalcinkaya2014; Ye, Li, & Tan, Reference Ye, Li and Tan2017). Social exchange theory (SET) is among the most prominent and influential theories used in explaining positive and desirable workplace behaviors, and social relationships. According to SET, individual’s interactions are often perceived as contingent and interdependent on the actions of other people; and that interdependent transactions can generate excellent relationships. The ‘rule’ of exchange materialize a ‘normative definition of the situation that forms among or is adopted by the participants in an exchange relation’ (Emerson, Reference Emerson1976: 351). Seibert, Wang, and Courtright’s (Reference Seibert, Wang and Courtright2011) meta-analytic review of SET revealed that employees feel strongly obligated to reciprocate when empowered, because POS aids the development of social exchange between organization and employees (Fallon & Rice, Reference Fallon and Rice2015). Moreover, employee’s emotional attachment to the organization can be built through development-oriented practices (Dymock, Billett, Klieve, Johnson, & Martin, Reference Dymock, Billett, Klieve, Johnson and Martin2012). Based on the above reasoning, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 1: Perceived organizational support is positively related to extra-role behavior.

POS and knowledge hiding behavior

Connelly et al. (Reference Connelly, Zweig, Webster and Trougakos2012: 65) defined knowledge hiding as ‘withholding or concealing of relevant information or knowledge, ideas, and know-how requested by a co-worker at workplace.’ It simply implies that employee give little or no effort toward the realization of organizational knowledge (Lin & Huang, Reference Lin and Huang2010; Connelly et al., Reference Connelly, Zweig, Webster and Trougakos2012). Knowledge hiding behavior has three dimensions, namely, playing dumb, evasive hiding, and rationalized hiding (Connelly et al., Reference Connelly, Zweig, Webster and Trougakos2012). Playing dumb is when the person hiding knowledge assumes a position of ignorance to his/her subordinate regarding a relevant knowledge or information requested by the subordinate. According to Ladan, Nordin, and Belal (Reference Ladan, Nordin and Belal2017), an example of statement showing an individual is playing dumb is ‘Am not aware of the knowledge.’ Evasive hiding is said to be a situation where the individual hiding knowledge provides an incorrect or misleading information while the last dimension is rationalized hiding and is a situation when the individual hiding knowledge gives rational justification why they will not share the requested knowledge by their coworkers and putting a blame for it on a third party. An example of statement that typifies rationalized hiding is ‘the information you are requesting is classified and not permitted to be shared with a third party.’ As psychological ownership theory postulated, individuals are often in the ‘state of feeling as though the piece of ownership is theirs’ (Pierce, Kostova, & Dirks, Reference Pierce, Kostova and Dirks2001: 299). In the context of this study, the target/piece of ownership is knowledge. Employees with high psychological ownership may engage in knowledge hiding to retain a good level of control over the knowledge they possess. Research has shown that employees display unwanted behaviors when there is perception of distrust, cynicism, and lack of POS (Biswas & Kapil, Reference Biswas and Kapil2017; Collins, Reference Collins2017). Drawing on SET, employees are keen to reciprocate the actions of their organization. POS enhanced affective organizational commitment and knowledge sharing intention (Jeung, Yoon, & Choi, Reference Jeung, Yoon and Choi2017). This imply that the quality of employee’s relationship with hiring organization does impact the tendency to engage in knowledge hiding behavior. Except Poell and Batistič (Reference Poell and Batistič2017) and Tsay, Lin, Yoon, and Huang (Reference Tsay, Lin, Yoon and Huang2014), studies on the effects of POS are very limited. Based on the above reasoning, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 2: Perceived organizational support is negatively related to knowledge hiding behavior.

Knowledge hiding behavior and extra-role behavior

Organizations create their knowledge competencies through the encouragement of knowledge sharing as it leads to development of intellectual capital as well as high brainpower performance (Dalkir & Liebowitz, Reference Dalkir and Liebowitz2011). This implies that effective organizational performance is often accomplished via efficient communication, opinion, and experience sharing as well as transfer of insights among the employees (Chang, Liao, Lee, & Lo, Reference Chang, Liao, Lee and Lo2015). While most literature extensively examine the impact of knowledge sharing on organizational outcomes, we opted to investigate the impact of knowledge hiding on employees’ extra-role behavior, because the link has been underexplored. The work of Sofiah, Padmashantini, and Gengeswari (Reference Sofiah, Padmashantini and Gengeswari2014) outlined employees’ willingness to share as a direct consequence of the display of citizenship behavior. Knowledge hiding can be a form of effort withholding (Poell & Batistič, Reference Poell and Batistič2017) rather than giving. Scholars (e.g., Černe, Nerstad, Dysvik, & Škerlavaj, Reference Černe, Nerstad, Dysvik and Škerlavaj2014; Connelly & Zweig, Reference Connelly and Zweig2015) have argued that willingness to conceal is a form of antisocial behavior by employees. Antisocial or deviant behaviors even with justified reasons can hinder productivity and performance. Based on the above reasoning, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 3: Knowledge hiding behavior is negatively related to extra-role behavior.

Psychological entitlement and knowledge hiding behavior

Psychological entitlement is a pervasive and stable sense that one deserves more and is entitled to more than others (Campbell, Bonacci, Shelton, Exline, & Bushman, Reference Campbell, Bonacci, Shelton, Exline and Bushman2004). Psychologically entitled individuals are likely to have a high tendency of favoring self and a feeling of deserving praises and rewards (Harvey & Harris, Reference Harvey and Harris2010; Harvey, Harris, Gillis, & Martinko, Reference Harvey, Harris, Gillis and Martinko2014). Knowledge ownership is contested in the organizational context and it offers a suitable platform for potential conflict between employees and organizations. Researchers (e.g., Brown, Pierce, & Crossley, Reference Brown, Pierce and Crossley2014; Han, Chiang, McConville, & Chiang, Reference Han, Chiang, McConville and Chiang2015) argued that the tendency of organizations to ‘own what you know, can raise such conflicts with their employees.’ Psychology of ownership is the feeling of being psychologically tied to an object, in the context of this study knowledge. Thus, psychological ownership of knowledge (POK) delineates employees feeling of knowledge ownership and its possession (Han, Chiang, & Chang, Reference Han, Chiang and Chang2010; Pierce, Jussila, & Li, Reference Pierce, Jussila and Li2018), which may result in knowledge sharing or hiding. Ownership-driven knowledge hiding occurs either through: (1) overvaluing of knowledge or (2) anticipated loss of control (von der Trenck, Reference von der Trenck2015). Theorizing on POK theory, we argue that higher psychological entitlement may predict higher knowledge hiding behavior among bank employees. A plausible explanation for this is because individuals often invest money, time, and mental energy to acquire knowledge, for example, formal education, experience, and training. Thus, those with high sense of psychological knowledge ownership are prone to exhibit low knowledge sharing motivations (Serenko, Bontis, & Hull, Reference Serenko, Bontis and Hull2016) and high knowledge hiding behavior (Lin & Huang, Reference Lin and Huang2010; Peng, Reference Peng2013; Kettinger, Li, Davis, & Kettinger, Reference Kettinger, Li, Davis and Kettinger2015), because sharing is equal to transference of ownership. Based on the above reasoning, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 4: Psychological entitlement is positively related to knowledge hiding behavior

POS, knowledge hiding behavior, and extra-role behavior

POS seems to affect the way employees accommodate demands and valuate rewards, which aid the promotion of adaptive and positive organizational outcomes (Neves & Eisenberger, Reference Neves and Eisenberger2014). With the current competition in banking service industry, it has become paramount for managers to elucidate extra-role behaviors. Supportive climate is not enough, because innovative and extra-role behaviors can only materialize with organizational and social support (Mainemelis, Kark & Epitropaki, Reference Mainemelis, Kark and Epitropaki2015), and healthy workplace relationships (Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart, & Adis, Reference Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart and Adis2017). For instance, knowledge sharing was found to mediate the link between subjective well-being and innovative behavior (Wang, Yang, & Xue, Reference Wang, Yang and Xue2017). Similarly, knowledge hiding may mediate the link between POS and extra-role behavior, and this could be explained from the tenets of SET. Employees expect their organizations to support and value their contributions, and failure to do so may result in loss of motivation, alienation, and counter-productive behaviors (e.g., knowledge hiding). Such behaviors can reduce the desire to engage in extra-role behavior. It has been consistently shown that a sense of belonging and trust for organization can enhance commitment, knowledge sharing, and participative behaviors (Han, Chiang, & Chang, Reference Han, Chiang and Chang2010; Mayes et al., Reference Mayes, Finney, Johnson, Shen and Yi2017). Drawing on POK theory, which explains the feeling of possession linking to knowledge in a psychological sense that makes individuals to regard intangible/tangible objectives as an addition of themselves (Han, Chiang, & Chang, Reference Han, Chiang and Chang2010), this work propagates the notion that unsupportive workplace impairs organizational trust and social relationships, which may result in distrust in the management. This article theorizes that employees may engage in knowledge hiding behaviors, due to the believe of knowledge ownership, lack of trust, and sense of belonging. Excessive knowledge concealing may result in lower extra-role behavior. Based on the above reasoning, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 5: Knowledge hiding behavior mediates the relationship between perceived organizational support and extra-role behavior.

Psychological entitlement, knowledge hiding, and extra-role behavior

Psychological entitlement is generally associated with negative outcomes. Entitled followers are more likely to engage in self-serving attributions and prioritize their own needs above and beyond others in the organization (Harvey & Martinko, Reference Harvey and Martinko2009). According to Yam, Klotz, He, and Reynolds (Reference Yam, Klotz, He and Reynolds2017), entitlement serves as moral credential that foster employees to engage in both interpersonal and organizational deviance. Therefore, entitled individuals are more likely to act selfishly (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Bonacci, Shelton, Exline and Bushman2004) and be disrespectful toward others (Twenge & Campbell, Reference Twenge and Campbell2008). One reason why entitled employees may engage in knowledge hiding is related to status concerns. Such employees have a deep concern for what others think of them, and they place great value on receiving approval and recognition from others (Rose & Anastasio, Reference Rose and Anastasio2014). Two, psychologically entitled individuals are disposed to attributional biases that allow them to reinterpret their immoral actions as being, in fact, moral (Lee, Schwarz, Newman, & Legood, Reference Lee, Schwarz, Newman and Legood2017) through a process known as moral rationalization (i.e., blaming others for negative outcomes). Three, frequent performance feedback can apprise employees of the correctness and sufficiency of their behavior and might therefore influence a psychologically entitled employee’s ability to form inflated performance perceptions. Similarly, the amount of informative job-related information (i.e., management’s expectations, strategic plans, and ideas) will reduce ambiguity and aligns both employees and management’s expectations (Harvey & Harris, Reference Harvey and Harris2010). This article theorizes that in the absence of communication (i.e., evaluative and informative communication), individual’s entitlement might increase, which may later result in negative work outcomes. Given that extra-role behavior is not formally recognized by most organizations reward system (Spitzmuller & Van Dyne, Reference Spitzmuller and Van Dyne2013), in line with POK theory entitled individuals may engage in knowledge hiding to earn the respect of others. Consequently, these individuals are less likely to engage in extra-role behavior. They are likely to use their moral credentials and attributional biases to interpret the reasons for the reduced extra-role behavior. Research shows that collective knowledge psychological ownership weakens knowledge hiding because team’s success is more important than individual’s goals (Tewoldemedhin & Medeubayev, Reference Tewoldemedhin and Medeubayev2017). Thus, high perception of individual entitlement and knowledge ownership may result in greater knowledge hiding, which in turn affects extra-role behavior, because individual goals are more important than collective goals. Based on the above reasoning, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 6: Knowledge hiding behavior mediates the relationship between psychological entitlement and extra-role behavior.

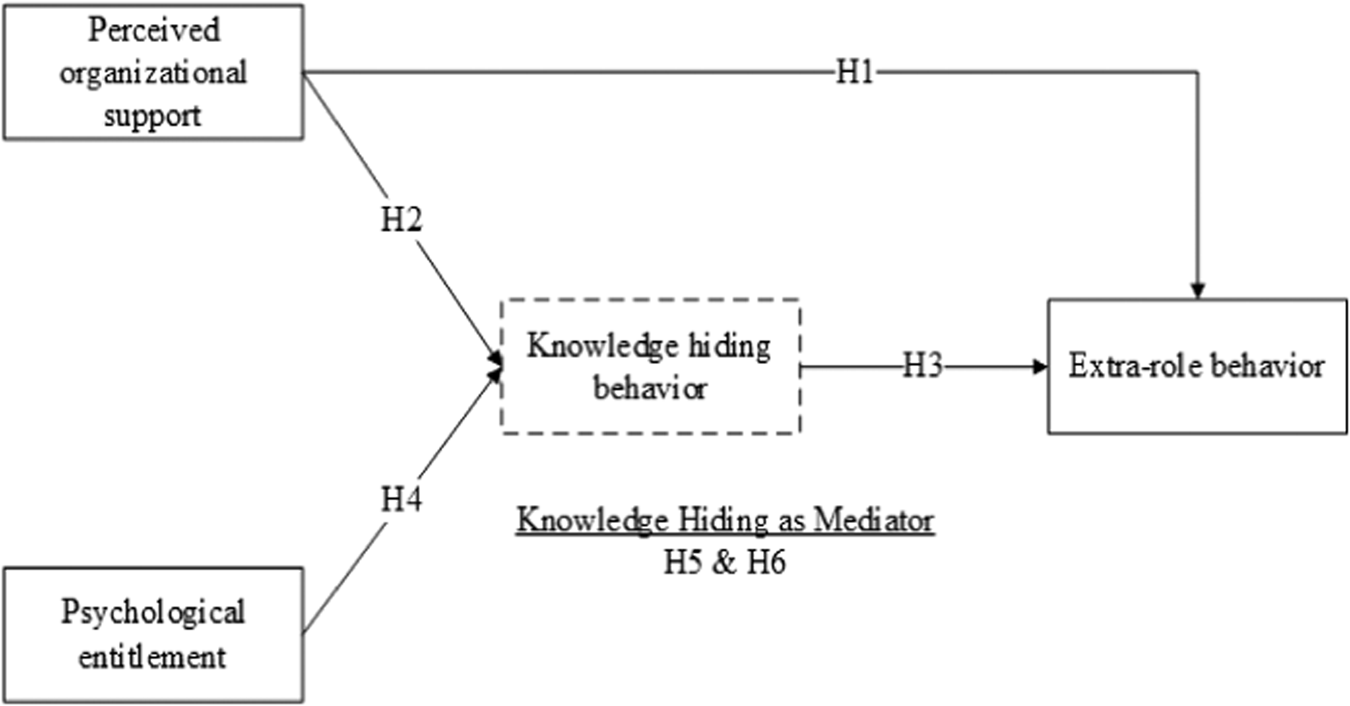

Figure 1 presents the proposed measurement model and the hypotheses.

Figure 1 Conceptual model

Research design

Sampling technique and procedure

The banking sector is a business of information, not just a business of money (Lamb, Reference Lamb2001).

As a service industry, the banking sector is heavily reliant on three assets: employees, clients which their employee build, and employee knowledge (Tewoldemedhin & Medeubayev, Reference Tewoldemedhin and Medeubayev2017). Moreover, banks do not sell goods, but rather services (Chatzoglou & Vraimaki, Reference Chatzoglou and Vraimaki2009). For commercial banks to survive the fierce market competition, they must encourage their personnel to engage in extra-role behavior, this makes such types of banks suitable to study our outcome variables (i.e., knowledge hiding and extra-role behavior). Participants are employees of Jordanian commercial banks. The country has 13 commercial banks that includes 607 branches and 15,332 employees (Association of Banks in Jordan, 2015).

Three independent translators were contacted to back-translate the survey items from English to Arabic and vice versa. Next, top management of the banks was contacted for permission. A preliminary study was carried out with 10 employees to ensure that the survey is free ambiguity. It appears that the participant fully understood, and have no problem rating the survey items. Before administering the full survey, a brief introduction about the research intent was issued to the participants. Moreover, participants were told that participation is voluntary, and that they can discontinue at any time. Participants were encouraged to answer as honestly as possible, and that there are no right or wrong answers; the researchers and the top management assured them of their confidentiality and anonymity (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2012). These techniques are known to ‘reduce people’s evaluation apprehension and make them less likely to edit their responses to be more socially desirable, lenient, acquiescent and consistent with how the researcher wants them to respond’ (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003: 888). In this study, a stratified simple random sampling technique was used. A sample of size n consists of n individuals from the population chosen in such a way that every set of n individuals has an equal chance to be the sample selected. The main aim is to ensure that the sample represents the true demographics of Jordan’s commercial banks, and the sample size was determined by SurveyMonkey sample calculator.

Measures

Knowledge hiding behavior was measured with survey items adopted from Connelly et al. (Reference Connelly, Zweig, Webster and Trougakos2012). POS was measured with survey items adopted from Eisenberger et al. (Reference Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison and Sowa1986) and Eisenberger, Armeli, Rexwinkel, Lynch, and Rhoades (Reference Eisenberger, Armeli, Rexwinkel, Lynch and Rhoades2001). Psychological entitlement was measured with survey items adopted from Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Bonacci, Shelton, Exline and Bushman2004). Extra-role behavior was measured with survey items adopted from Netemeyer and Maxham (Reference Netemeyer and Maxham2007). Participants responded using a 7-response points scale (1=‘strongly disagree’ to 7=‘strongly agree’).

Control variables

In this paper, the author(s) included participants’ age, gender, income, education, and work experience while testing the proposed hypotheses, because they were associated with knowledge hiding and extra-role behavior in prior research (e.g., Connelly et al., Reference Connelly, Zweig, Webster and Trougakos2012; Černe et al., Reference Černe, Nerstad, Dysvik and Škerlavaj2014; Černe, Hernaus, Dysvik, & Škerlavaj, Reference Černe, Hernaus, Dysvik and Škerlavaj2017; Xiao & Cooke, Reference Xiao and Cooke2018). The variables did not change the explanatory nature of the predictor variables on the criterion variables.

Data analysis

Sample and descriptive statistics

A total of 375 complete surveys were compiled. The dataset revealed that 45.1% of the employees were between 21 and 30 years; 25.9% of the participants were aged between 31 and 40 years; 18.4% of the participants were aged between 41 and 50 years; 6.9% of them are above 50 years old; and the rest were below 20 years. About 69.6% of the participants reported to have bachelor’s degree, 14.1% have higher degrees, 10.9% reported to have some college degrees, and the rest are high school leavers. Furthermore, monthly income is reported in Jordanian Dinars: 44.8% of the respondents earn <1,000; 31.5% earn between 1,000 and 1,499; 17.6% of the respondents reported to earn between 1,500 and 1,999; and the rest were earning more than 2,000 Dinars monthly. A majority of the respondents 42.9% have over 6 years and 28.3% have an organizational tenure between 4 and 6 years. While 18.4% have between 1 and 3 years, and the rest have <1 year organizational tenure.

Model fit indices

Confirmatory factor analysis was carried out to examine the structure and composition of the factors, as it is a viable approach to test construct validity. As a first step, we tested for a one factor model, in which all items were constraint to load on a single factor. This approach is widely used to assert the absence of common method variance. The single factor model yielded the following model fit indices: [χ2=1368.656, degress of freedom (df)=230, p<.000, χ2/df=5.951 goodness-of-fit (GFI)=0.708, normed fitness index (NFI)=0.617, incremental fit index (IFI)=0.660, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI)=0.623, comparative fitness index (CFI)=0.657, root mean square of approximation (RMSEA)=0.115].

A three-factor model in which psychological entitlement and playing dumb dimension of knowledge hiding behavior were combined to form one construct yielded the following model fit indices: (Δχ2=782.500, χ2=586.156, df=225, p<.000, χ2/df=2.605, GFI=0.871, NFI=0.836, IFI=0.892, TLI=0.878, CFI=0.891, RMSEA=0.066). The four-factor measurement model yielded the following model fit indices: (Δχ2=165.622, χ2=420.534, df=224, p<.000, χ2/df=1.877, GFI=0.914, NFI=0.882, IFI=0.941, TLI=0.933, CFI=0.941, RMSEA=0.048). The four-factor measurement model has satisfactory model fit indices than the alternative models. Thus, it appears that common method bias was not a major problem (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2012). Standardized factor loadings of items that are <0.40 were eliminated (Bagozzi & Yi, Reference Bagozzi and Yi1988). The retained item loadings ranged from 0.43 to 0.82 with t-values between 6.809 and 16.757 (see Table 1).

Table 1 Scale items standardized factor loadings and descriptive statistics

Note. –* dropped items during confirmatory factor analysis

The composite reliability (CR) value for the four variables were above the threshold of 0.60 (Hair Jr, Black, Babin, & Anderson, Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010). The average variance extracted (AVE) is higher than 0.5, but we can accept lesser values. Because Fornell and Larcker (Reference Fornell and Larcker1981) reported that if AVE is <0.5, but CR is >0.6, the convergent validity of the construct is still adequate. Several scholarly works support this notion (e.g., Huang, Wang, Wu, & Wang, Reference Huang, Wang, Wu and Wang2013; Calisir, Basak & Calisir, Reference Calisir, Basak and Calisir2016; Gökçearslan, Mumcu, Haşlaman, & Çevik, Reference Gökçearslan, Mumcu, Haşlaman and Çevik2016). The maximum shared variance (MSV) of the constructs were found to be less than AVE. The correlations coefficients of the researched variables did not exceed 0.80; this provided the evidence for discriminant validity (Anderson & Gerbing, Reference Anderson and Gerbing1988; Kline, Reference Kline2005). Cronbach’s α values of the researched variables were all above the threshold of 0.70, as recommended by Nunnally (Reference Nunnally1967). This provided the evidence of internal consistency and instrument reliability (see Table 2).

Table 2 Mean, standard deviation, and correlation coefficients

Note. AVE=average variance extracted; α=Cronbach’s alpha; CR=composite reliability; MSV=maximum shared variance; SD=standard deviation. ***Significant at the 0.001 level, **Significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed)

Bivariate correlations

Bivariate correlation shows that POS negatively co-relates with psychological entitlement (r=−0.244, ρ<0.001) and positively co-relates with extra-role behavior (r=0.333, ρ<0.001). Knowledge hiding behaviors positively co-relate with psychological entitlement (r=0.150, ρ<0.001) and negatively co-relate with extra-role behavior (r=−0.103, ρ<0.05). These results provided preliminary support for the measurement model. See Table 2 for the inter-correlation coefficients of the variables, alongside means, standard deviations, Cronbach α’s, CR, AVE, and MSV.

Hypotheses testing

To test the hypothesized model, the following control variables (i.e., gender, age, income, education, work experience, and/or organizational tenure) were considered. Applying structural equation modeling with maximum likelihood estimates in AMOS, we found that POS has a positive impact on extra-role behavior (β=0.179, ρ<0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 1 received empirical support. Contrariwise to our expectation, the result shows that POS did not influence knowledge hiding behavior (β=−0.062, ρ>0.100). Thus, Hypothesis 2 did not receive empirical support. Knowledge hiding behavior has a negative impact on extra-role behavior (β=−0.118, ρ<0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 3 received empirical support. Psychological entitlement has a positive impact on knowledge hiding behaviors (β=0.150, ρ<0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 4 received empirical support (see Table 3).

Table 3 Maximum likelihood coefficients

Note. β=standardized beta; SE=standard error

***Significant at the p<.001 level, **Significant at the p<.05 level (two-tailed)

To test for the indirect effects, a bias-corrected bootstrapping approach with a resample size of n=5,000 and 95% confidence interval following the procedures was set-forth by Hayes (Reference Hayes2015). The result revealed that the indirect effect of POS on extra-role behavior through knowledge hiding behavior was not significant (β=0.007, ρ>0.100). Thus, Hypothesis 5 did not receive empirical support. We also found that the indirect effect of psychological entitlement on extra-role behavior through knowledge hiding behavior was negative and significant (β=−0.018, ρ=0.011). The bias-corrected estimate suggested a partial mediation as follows (95% confidence interval: −0.043 and −0.003). Thus, Hypothesis 6 was supported.

Results and discussion

Understanding situational and interpersonal factors explaining the prevalence of knowledge hiding and extra-role behavior is critical for theory advancement and to provide guidance for practice.

Research exploring the antecedents and consequences of knowledge hiding behavior is scarce. Several scholars called for further research (Connelly et al., Reference Connelly, Zweig, Webster and Trougakos2012; Peng, Reference Peng2013; Černe et al., Reference Černe, Nerstad, Dysvik and Škerlavaj2014; Connelly & Zweig, Reference Connelly and Zweig2015). This paper responded to these calls by exploring and empirically tested the mechanistic nature of knowledge hiding behavior. More subtly, the present study investigated the relationship between POS, psychological entitlement, and extra-role behavior as mediated by knowledge hiding behavior in the banking industry. Prior research denotes the importance of knowledge and extra-role behavior for commercial banks; in addition, the banking industry has been classified as knowledge-dependent and intensive industry (Taherparvar Esmaeilpour, & Dostar, Reference Taherparvar, Esmaeilpour and Dostar2014; Campanella, Derhy & Gangi, Reference Campanella, Derhy and Gangi2018). Thus, uncovering the underlying mechanism, for example, antecedents and consequences can provide important insights for human resource managers in the industry.

The findings support the assumption that POS positively impact employees’ extra-role behavior. Drawing on SET, employees are likely to reciprocate with extra-role behavior if they perceive high POS. This result is in line with previous studies on the positive impact of POS (Sofiah, Padmashantini, & Gengeswari, Reference Sofiah, Padmashantini and Gengeswari2014; Kurtessis et al., Reference Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart and Adis2017; Mayes et al., Reference Mayes, Finney, Johnson, Shen and Yi2017). This finding suggests to managers that the apparent strategic tool in getting employees engage in extra-role behavior is to create a climate of support that comforts them to share and get along with organizational values.

POS did not have a significant impact on knowledge hiding behavior. This finding is not congruent with prior findings and the established theoretical framework. Prior scholars noted that monetary compensation (Bartol & Srivastava, Reference Bartol and Srivastava2002), workplace justice climate (Bouty, Reference Bouty2002), and psychological contract (Scarborough & Carter, Reference Scarborough and Carter2000) are important predictors of knowledge sharing, the antonym for knowledge hiding. More related findings (e.g., Jeung, Yoon, & Choi, Reference Jeung, Yoon and Choi2017) found that high POS can increase knowledge sharing intention, decrease knowledge withholding intentions (Tsay et al., Reference Tsay, Lin, Yoon and Huang2014), and knowledge hiding (Poell & Batistič, Reference Poell and Batistič2017). The oriental nature of Jordanians may be the reason we have such finding as opposed to individualist nature of the Western culture and findings, for example, low POS result in knowledge hiding (Poell and Batistič, Reference Poell and Batistič2017). Given the limitations of research on these two variables, more research is needed before the current result could be archived. Other theoretical frameworks such as affective events theory and social network theory may explain how social network structure and social tie can determine the occurrence knowledge hiding; this might help uncover the mechanistic germination of knowledge hiding and its outcomes.

Our third hypothesis indicates a significant negative relationship between knowledge hiding and extra-role behavior. More subtly, those who share knowledge are recompensed with information from colleagues and positive social images, but are also distrait and harmed by losing exclusive informational advantage (Kimmerle, Wodzicki, Jarodzka, & Cress, Reference Kimmerle, Wodzicki, Jarodzka and Cress2011). Similar assertions on creativity exist in the literature (e.g., Wasko & Faraj, Reference Wasko and Faraj2005; Serenko, Bontis, & Hull, Reference Serenko, Bontis and Hull2016; Törner et al., Reference Törner, Pousette, Larsman and Hemlin2017; Fong, Reference Fong, Men, Luo and Jia2018), but this link has generally been left unexplored. We addressed this research gap by providing empirical evidence about the detrimental effect of knowledge hiding on extra-role behavior. Thus, it is recommended that bank managers should find and manage the antecedents of employee knowledge hiding, because those employees exhibiting these behaviors will not engage in extra-role behavior.

Regarding our fourth hypothesis, the result confirms that psychological entitlement is positively related to knowledge hiding behavior. This is because psychologically entitled persons tend to rationalize their decisions to suit their personal purpose (Connelly et al., Reference Connelly, Zweig, Webster and Trougakos2012; Kettinger et al., Reference Kettinger, Li, Davis and Kettinger2015; Christina et al., Reference Christina, Stefan and Markus2016). POK theory maintains that one aspires to obtain and conserve their knowledge to retain control or when they are not adequately rewarded or recognized for their achievements. Rhee and Choi (Reference Rhee and Choi2017: 828) quoted that ‘high-status members can interfere with or distort intra-team knowledge flow to achieve their own goals, consequently sacrificing team performance.’ These high-status members are mostly knowledgeable workers who may possess high psychological entitlement. The lesson here is that managers should monitor and evaluate employees’ perceptions of entitlement because of its deleterious effects on the flow of knowledge in the organization.

Having established the direct associations in the first four hypotheses, this study moves further with the indirect association between the variables under investigation. Regarding our fifth hypothesis, the result suggests that knowledge hiding behavior did not mediate the relationship between POS and extra-role behavior. Although knowledge hiding has an impact on extra-role behavior in line with Černe et al. (Reference Černe, Nerstad, Dysvik and Škerlavaj2014) and Bogilović, Černe, and Škerlavaj (Reference Bogilović, Černe and Škerlavaj2017), plausible explanations for this finding might be, first, knowledge is mostly solicited by colleague. Second, Jordan is more oriental in nature; thus, employees are prone to make collective decisions. Even with low POS, individual employee is less incline to engage in knowledge hiding to avoid initiating the ‘loop of distrust’ which may isolate them from their coworkers (Černe et al., Reference Černe, Nerstad, Dysvik and Škerlavaj2014), but these are more likely to lower their innovative and extra-role behaviors.

Regarding our sixth hypothesis, the result suggests that knowledge hiding behavior mediates the relationship between psychological entitlement and extra-role behavior. Psychological entitlement may have functioned as an underlying mechanism of the credentialing process in moral licensing to engage in knowledge hiding behavior. Moral credentials encourage employees to engage in both interpersonal and organizational deviance. This provides a further justification for the mediating role of knowledge hiding behavior (Yam et al., Reference Yam, Klotz, He and Reynolds2017). The former interpersonal deviance (i.e., increased knowledge hiding) and the latter organizational deviance (i.e., reduced extra-role behavior) suggest that presence of knowledge hiding represents a helper function for the relationship.

Implication for practice and theory

Knowledge hiding is associated with decreased work-related interactions, hampered unit performance, and poor decision making (Evans, Hendron, & Oldroyd, Reference Evans, Hendron and Oldroyd2015). Recent studies posit that identifying the organizational, team and individual-level antecedents of knowledge hiding may be interesting and can enhance knowledge sharing, organizational productivity, and performance (Connelly et al., Reference Connelly, Zweig, Webster and Trougakos2012; Connelly & Zweig, Reference Connelly and Zweig2015); employee creativity and extra-role behavior (Demerouti, Bakker, & Gevers, Reference Demerouti, Bakker and Gevers2015; Zhao & Xia, Reference Zhao and Xia2017). As such, the results of our study may provide some important practical implications for organizations. First, bank management can leverage POS to bring out the best out of their employees. It is unfortunate that bank employees must deal and make transactions with different types of customers (i.e., rude, uncivil, nasty, etc). The study findings suggest that if bank managers want their employees to do great jobs with customers, then they must be ready to do a great job with their employees by providing adequate support. This is in line with SET, which postulates that POS is a symbiotic mechanism. It is also important that management in financial establishments should exert efforts geared toward providing support climate in their organization to foster in extra-role behavior.

Second, human resource management should also note that lack of knowledge sharing does interprets motivations for hiding. Knowledge sharing fails for various reasons. For instance, individuals cannot share knowledge they do not possess. In this case, there is no attempt to hide the knowledge, thus, organizational knowledge sharing initiatives, functioning as motivational factors to encourage employees to share knowledge, do not necessarily eliminate knowledge hiding due to the existence of distinct driving factors for knowledge hiding. Henceforth, human resource management strategies designed to eliminate knowledge hiding behavior should be implemented as complementary to knowledge sharing initiatives (Xiao & Cooke, Reference Xiao and Cooke2018).

Third, knowledge sharing and management have grown in its importance to organizational sustenance and survival. Thus, bank managers need to ensure that there is a proper flow of knowledge within their organization. Our findings suggest that managers can either increase their effort in providing supportive climate that would enhance sharing and extra-role behavior. This is because supportive climate signals organizational equity or justice and ethical values to subordinates. This may to some extent affect employee extra-role behavior. In doing so, conflicts of knowledge ownership are less likely to arise, technically, diminishing the idea of psychological entitlement. Moreover, based on POK theory entitled, employees are likely to go to extra length to achieve their objectives. Thus, managers should take measures to avoid the development of knowledge hiding because of psychological entitlement. For instance, several behavioral shaping and control mechanisms should be put in place (i.e., counselling, mentoring, training, reward, recognition, and others) to hinder the development of psychological entitlements among workers, thereby, reducing the propensity of potential knowledge hiding behavior.

Fourth, entitled individuals tend to make self-serving attributions, which may increase the likelihood for morally disengagement and greater perception of injustice in the workplace. Henceforth, managerial strategies (i.e., the use of objective data to measure performance, performance-tracking, reward, and compensation strategies) should be put in place to reduce the tendency of attributions, ambiguities, and clear managerial communication. Doing this may reduce the level of psychological entitlement. This research stands in the forefront in bearing to light the untapped dimension of literature that enables researchers to blend SET and POK theory to predict employee behaviors and work outcomes.

Limitations and future research direction

This study has several limitations that are worth mentioning, even though certain objective conditions exist. First, to decrease exposure to common method bias, the researcher employed a systematic random sampling method, both procedural and statistical approach. Moreover, the collection of questionnaire data from a single industry and country limits the generalizability of the findings. A research design incorporating survey data with interviews could be a useful avenue to take the current research finding further, by considering contextual factors such as organizational fairness and personality traits; these factors could potentially allow for the exploration of intervention mechanism of knowledge hiding behaviors among employees. Future researchers are encouraged to test for role of organizational justice and personality traits as antecedents of knowledge hiding behaviors.

In lieu of the extensive literature review carried out on psychological entitlement in relation to organizational support, knowledge hiding behaviors and organizational citizenship behavior (extra role), two main areas can be considered for further research. The first is exploring the contributory organizational factors of psychological entitlement perceptions. Scholars may explore the relationship between entitlement perceptions and the hubris, pride, and indulgent practices at organizational level because these practices can increase entitlement perceptions as noted by Maitlis, Vogus and Lawrence (Reference Maitlis, Vogus and Lawrence2013) that hubris is linked with sequestered sense-making in organization. Second, future research can explore the moderating role of organizational justice on the relationship between employees’ perception of entitlement and knowledge hiding and extra-role behavior.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.