INTRODUCTION

Ever since the posteconomic reforms of 1991, India has witnessed an unprecedented growth and catapulted among the world’s fastest-growing economies. The contribution of its IT industry cannot be overstated in this regard, which has made India an attractive destination for top-tier IT organizations from across the globe. Based on recent estimates, Indian IT industry contributes roughly 9.5% of total gross domestic product and is projected to generate $225 billion revenues by 2020 (India Brand Equity Foundation, 2015). At the same time, IT industry experiences roughly 21.9% attrition rates in the last fiscal year (Deloitte, 2015). Sustaining such a growing industry requires a continuous supply of competent and committed workforce to deliver value and performance. However, the current workforce is multigenerational, constituted by three generations namely, Baby boomers (1946–1960), Gen X (1961–1980), and Gen Y (1981–2000). Based on generational cohort theory, a generation includes members born in same time and experiencing the common formative events during their developmental times, leading to similar value system, perceptions, and attitudes (Kupperschmidt, Reference Kupperschmidt2000). For instance, Gen Y members have experienced events such as rise of internet, economic liberalization, popularity of social media, rise of environmental awareness, etc. However, boomers are retiring and Gen X employees are taking up leadership positions, thus leaving gaps in executive level positions to be filled by young generation, thereby shifting the focus on Gen Y members (Meister & Willyerd, Reference Meister and Willyerd2010). By 2030, nearly three-fourths of the global workforce will comprise of Gen Y members and a significant portion of this will comprise of Indians. Hence, Gen Y members are future workforce; however exhibit different work values, behavior, and preferences as compared with baby boomers and Gen X. More importantly, literature indicates that Gen Y employees are low on commitment and frequently switch jobs (Howe & Strauss, Reference Howe and Strauss2000; Cennamo & Gardner, Reference Cennamo and Gardner2008; Lub, Bijvank, Bal, Blomme, & Schalk, Reference Lub, Bijvank, Bal, Blomme and Schalk2012). Therefore, organizations must integrate top leadership, that is strategic leaders to formulate a strategy to improve commitment levels of Gen Y employees. In addition, contemporary organizations are operating in a complex business environment characterized by rapid globalization, dynamism, and turbulence. This makes the case of strategic leadership more compelling in this ever-changing landscape (Ireland & Hilt, Reference Ireland and Hitt2005; Hilt, Haynes, & Serpa, Reference Hitt, Haynes and Serpa2010).

The extant literature suggests that Gen Y employees exhibit dispositional characteristics particularly, high growth need, learning orientation, needs for achievement, and self-development. Hence they are attracted towards innovative organizations that provide a nurturing environment to support their continuous development (Terjesen, Vinnicombe, & Freeman, Reference Terjesen, Vinnicombe and Freeman2007; Ng, Schweitzer, & Lyons, Reference Ng, Schweitzer and Lyons2010). This explains their quest for continuous learning in order to make a positive impact on the organization and stay self-marketable in the talent market. Therefore, recognizing the developmental needs of Gen Y is critical to motivate this generation. Their differences in personality and motivators make them alienated to job security and they switch jobs frequently in search of satisfying their needs for self-esteem and self-actualization. Similar findings are reported by a recent Indian study, MaFoi Randstad Workmonitor (2011), which indicates that highest mobility is observed among young Indian employees, who prefer changing jobs in search of developmental opportunities. Moreover, Gen Y employees prefer an inclusive style of management and approachable top leaders who practice coaching and mentoring, share a compelling vision, and treat them as individual partners (Dulin, Reference Dulin2005; Lowe, Levitt, & Wilson, Reference Lowe, Levitt and Wilson2008). Therefore, Gen Y employee’s leadership preferences are in fitment with strategic leaders’ activities namely creating and communicating a vision for the future, developing human capital through exploring key competencies, aligning individual goals with overall strategy, and creating a learning culture (Ireland & Hitt, Reference Ireland and Hitt1999).

Although, Gen Y employees have become the topic of widespread attention in academic and popular press, however there is a scarcity of empirical literature on how to increase their commitment through competency development and top leadership support. Moreover, according to the extant literature, few studies have been carried out from an Indian Gen Y employees’ perspective. Thus, the aim of the present study is to examine the relationship between organizational learning, strategic leadership, competency development, and affective commitment of Gen Y employees. Further, we assess the moderating effects of strategic leadership and mediating effects of competency development on the impact of organizational learning on Gen Y employees’ affective commitment. The present study contributes to the literature on Indian Gen Y employees and how to evoke their positive attitudinal response manifested as affective commitment.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND HYPOTHESES

Strategic leadership

The term ‘strategic leadership’ is coined from the word ‘strategy’ (Greek words stratus – a large army and egy – a leader or English word hegemony – leadership among nations) to refer to the leader of an organization (Adair, Reference Adair2007). The scholarly literature broadly defines strategic leadership as the ‘ability to anticipate, envision, maintain flexibility, think strategically, and work with others to initiate changes that will create a viable future for the organization’ (Ireland & Hitt, Reference Ireland and Hitt1999: 45). It is conceived as ‘the ability to influence others to voluntarily make day-to-day decisions that enhance the long-term viability of the organization, while at the same time maintaining its short-term financial stability’ (Rowe, Reference Rowe2001: 82–83). It incorporates visionary and managerial aspects of leadership by simultaneously allowing for risk-taking and rationality that is long-term strategic orientation without ignoring the short-term perspectives. A strategic leader envisions a future with the present context and pays attention to short-term financial stability, with an understanding of what long-term objectives to be achieved. In this vein, strategic leaders possess dimensions of creative leadership and operational leadership to maintain financial stability and achieve short-term goals respectively. Strategic leaders follow transactional style primarily to control and maintain operational efficiency and stability. While, transformational style is followed to build and communicate the vision in a way that employees gain meaning and develop commitment to it. In this vein strategic leaders adopt control measures such as financial control in line with operational dimension to maintain short-term performance goals and strategic controls to foster change, flexibility, risk-taking, and innovation.

In this paper, we have adopted Boal and Hoojbeg’s (Reference Boal and Hooijberg2001) conceptualization of strategic leadership, that is, a complex of absorptive capacity (includes the awareness, learning and practice of new information), adaptive capacity (ability to change), and managerial wisdom (ability of being aware of intuition, environmental perception, and social relations). In contrast to conventional leadership styles such as transformational leadership, a strategic leader scores highly on all three levels of self, others, and organization (Crossan, Lane & White, Reference Crossan, Lane and White1999). In other words, strategic leaders have holistic orientation, that is concerned with the leadership ‘of’ organizations as opposed to ‘in’ organizations, thereby emphasizing on organizational-level variables including learning, innovation rather than focusing solely on performance of immediate followers (Boal & Hooijberg, Reference Boal and Hooijberg2001; Vera & Crossan, Reference Valle, Valencia, Jimenez and Caballero2004; Elenkov, Judge, & Wright, Reference Elenkov, Judge and Wright2005).

A well-defined vision is one of the key aspects of strategic leaders. This vision gives a strong sense of purpose and direction, which facilitate strategy formulation and implementation and defines the future of the firm. They communicate this vision to inspire others and to build focus and commitment towards organization’s goals (Shrivastava & Nachman, Reference Shrivastava and Nachman1989; Ireland & Hitt, Reference Ireland and Hitt1999; Daft, Reference Daft2005). One of the fundamental theories pertaining to strategic leadership is Upper echelon theory, which states that top management teams, CEOs, senior managers, and others are ultimately responsible for deciding upon the vision and direction of the organization, however, many others play an important role in exercising strategic leadership (Hambrick & Mason, Reference Hambrick and Mason1984). This theory forms the basis of strategic leadership theory, which proposes that values, cognitive styles, and preferences of upper echelon influence the strategic choices and information processing, which ultimately shape strategic decisions (Finkelstein & Hambrick, Reference Finkelstein and Hambrick1996).

Organizational learning and its effect on affective commitment

Learning is widely conceived as a social process (Limerick, Passfield, & Cunnington, Reference Limerick, Passfield and Cunnington1994). Organizational learning refers to organizational efforts such as knowledge acquisition, information distribution, information interpretation, and mind that influence positive organizational revolution considerably and inconsiderably (Templeton, Lewis, & Snyder, 2002: 175). Schwandt and Marquardt define organizational learning as ‘a system of actions, actors, symbols, and processes that enables an organization to transform information into valued knowledge which in turn increases its long-run adaptive capacity’ (Reference Schwandt and Marquardt2000: 8). It is a process of change in thought and action encompassing detection and correction of errors and improving the actions by acquiring knowledge through learning processes (Argyris & Schon, Reference Argyris and Schön1978; Fiol & Lyles, Reference Fiol and Lyles1985; Crossan, Lane, & White, Reference Crossan, Lane and White1999 Hitt, Haynes, & Serpa, Reference Hitt, Haynes and Serpa2010). In broad terms, it is the process of developing new knowledge by creating common perspectives of organizational members and thus has a potential bearing on employees’ behavior and performance (Valle, Valencia, Jimenez, & Caballero, Reference Vera and Crossan2011).

Organizational learning has received considerable academic attention across a myriad of disciplines. However, most of the management literature has stressed on distinguishing the various types and levels of learning such as adaptive and generative learning (Senge, Reference Senge1990); strategic and tactical learning (Dodgson, Reference Dodgson1991); single loop, double loop, and deutero-learning (Argyris & Schon, Reference Argyris and Schön1978). One of the catalysts for the focus on organizational learning is the present turbulent and hyper-competitive business environment. Such an environment demands organizations to be agile and flexible, which largely depends on their ability to continuously learn and develop to stay sustainable and gain competitive advantage (López, Peón, & Ordás, 2005). There is compelling evidence in the literature, which suggests a strong linkage of organizational learning with work attitudes. Organizations with a focus on organizational learning achieve higher levels of employees’ job satisfaction, profitability, and performance (Leslie, Aring, & Brand, Reference Leslie, Aring and Brand1998; Rowden & Conine, Reference Rowden and Conine2005). Likewise, several studies revealed that organizational commitment is significantly associated with all the organizational learning levels including individual learning, team learning, and environmental learning (Lankau & Scandura, Reference Lankau and Scandura2002; Najaf Aghaei & Shahrbanian, Reference Najaf Aghaei and Shahrbanian2012; Mehrabi, Jadidi, Allameh Haery, & Alemzadeh, Reference Mehrabi, Jadidi, Allameh Haery and Alemzadeh2013).

Affective commitment is denned as ‘an affective or emotional attachment to the organization such that the strongly committed individual identifies with, is involved in, and enjoys membership in, the organization’ (Allen & Meyer, Reference Aiken and West1990: 2). It expresses the emotional attachment of the employees, which acts as a binding force. Therefore, employees with a high degree of affective commitment feel integrated with the organization and identify themselves with it (Porter, Crampon, & Smith, Reference Porter, Crampon and Smith1976; Mowday, Steers, & Porter, Reference Mowday, Steers and Porter1979). The extant research on affective commitment suggests following antecedents – positive work experiences of the employee, organizational and personal characteristics, job challenge, degree of autonomy, and the variety of skills utilized by the employee (Allen & Meyer, Reference Aiken and West1990; Mathieu & Zajac, Reference Mathieu and Zajac1990). Further, affective commitment is shown to be positively related with higher intention to stay, and lower turnover intentions and absenteeism (Mathieu & Zajac, Reference Mathieu and Zajac1990; Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1997; Griffeth, Hom, & Gaertner, Reference Griffeth, Hom and Gaertner2000).

In context of Gen Y employees perception of organizational learning is highly important as they display strong learning orientation (Aryee, Lo, & Kang, Reference Aryee, Lo and Kang1999). Moreover, when an organization exhibits care and concern for employees and offer avenues for development, it satisfies their higher-order need of self-actualization and creates an emotional belongingness with the organization. Once Gen Y employees recognize that organization offers a compelling employee value proposition wherein the organization is committed to their overall development, it results in their positive reciprocal behavioral outcomes viz. affective commitment. The perception of organizational learning environment within organization evokes positive attitudinal response manifested as high affective commitment. This is grounded on affective events theory, which states that affective work events result in affective reactions, which in turn, shape employees’ work attitudes and behaviors (Weiss & Cropanzano, Reference Weiss and Cropanzano1996). In this vein, organizational learning environment provides an affective experience, which generates affective reactions in the form of affective commitment. Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 1: Organizational learning has a positive impact on Gen Y employees’ affective commitment.

Mediating role of competency development

Competencies are conceptualized as the success factors that differentiate a top-performing employee from a mediocre one (Kochanski, Reference Kochanski1996). In similar vein, Woodruffe views a competency as ‘a set of behavior patterns that the incumbent needs to bring to a position in order to perform its tasks and functions with competence’ (Reference Woodruffe1992: 17). Competency development is defined as ‘an important feature of competency management, which encompasses all activities carried out by the organization and the employee to maintain or enhance the employee’s career, learning, and functional competencies’ (Forrier, Sels, & Stynen, Reference Forrier, Sels and Stynen2009).

Development of competencies is linked to personal development and achievement of self-actualization. The extant literature indicates a positive association between development of competencies, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment (Mathieu & Zajac, Reference Mathieu and Zajac1990; McCusker & Wolfman, Reference McCusker and Wolfman1998). Therefore, employees with access to competency development opportunities are highly motivated and committed. The extant research has shown that the organizational initiatives to offer learning and development opportunities, particularly skill and capacity development are strong predictors of employee satisfaction and retention (Cole, Reference Cole1999). Another study reveals that organizational learning promotes sharing of information and knowledge, and creates learning opportunities resulting in skill development (Argyris & Schon, Reference Argyris and Schön1978). This results in building their personal and professional competencies such as problem-solving, networking, decision making, self-confidence, opportunity identification, and analytical aptitude. This is consistent with earlier research, which suggests a strong association between knowledge sharing and competency development (Naim & Lenka, Reference Naim and Lenka2016).

Gen Y employees exhibit a dominant growth need and a learning goal orientation; hence they are attracted to the developmental initiatives offered by organization (Aryee, Lo, & Kang, Reference Aryee, Lo and Kang1999; Naim & Lenka, Reference Naim and Lenka2017a). Moreover, when Gen Y employees perceive an environment conducive for competency development, it generates a sense of emotional attachment with the organization. Thus, competency developmental opportunities offered by the organization evoke positive attitudinal response manifested as high affective commitment. Thus, in consistent with social exchange framework, whereby competency developmental opportunities offered by the organization evoke positive attitudinal response manifested as high affective commitment (Emerson, Reference Emerson1976). Based on this discussion, we believe that competency development mediates the relationship between organizational learning and affective commitment. Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 2: Competency development mediates the relationship between organizational learning and affective commitment.

Moderating role of strategic leadership

In this volatile, hyper-competitive business environment, one of the main aim of strategic leaders is to create a nimble organization that can respond to rapid changes and stay sustainable. Such a hostile and disruptive environment demands interpretation of changing context through sensemaking activities achieved through organizational learning. One of the effective means of achieving it is through development of human capital. Therefore, strategic leaders facilitate the development of employees by motivating them to continuously enrich their capabilities and offer opportunities to realize their true potential and develop as talent (Ireland & Hilt, Reference Ireland and Hitt1999). Importantly, one of the main activates of strategic leaders is to enhance the absorptive capacity of firm, groups, and individuals by inculcating a culture that facilitates continuous learning, dialog, collaboration, autonomy, risk-taking, experimentation, and nurturing relationships (Hilt, Haynes, & Serpa, Reference Hitt, Haynes and Serpa2010). Being visionary they sense the market demands and hence have a holistic approach of development, that is by focusing on their managerial and visionary aspects; they strive to drive organization to become continuous learning engines (Centre for Creative leadership, 2004). It is worthwhile to note that contingent upon different circumstances, strategic leaders follow behavioral leadership styles such as transformational, charismatic, transactional, and authentic in order to influence and lead followers towards achievement of organizational goals.

Strategic leaders are primarily responsible for implementing strategic plans in the whole organization. They act as learning agents and influence the development of the organization by creating and communicating a compelling vision. They are supportive leaders, who empower their followers to take initiatives, stimulate them to be creative, learn from mistakes, and achieve the performance beyond expectations (Năstase, Reference Năstase2010). Evidence from the past literature corroborates the positive impact of transformational leadership on organizational learning (Burke, Reference Burke2006). In addition, the extant research reveals a significant positive effect of top management support on organizational learning and knowledge sharing (Vera & Crossan, Reference Valle, Valencia, Jimenez and Caballero2004). Therefore, support for organization-wide learning, development of knowledge sharing, and continuous learning culture within the organization will foster the competency development of Gen Y employees. As a result, Gen Y employees will have access to developmental opportunities whereby they can expand their competency levels through acquisition of knowledge from peers and superiors reinforced by knowledge sharing and organizational learning culture within the organization. In other words, employees working under strategic leaders will exhibit a positive perception of competency development. Therefore, presence of strategic leaders reinforces the organizational learning, thereby strengthening the influence of organizational learning on competency development. Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 3a: Strategic leadership moderates the relationship between organizational learning and competency development.

Mediated moderation

Till now, we have proposed that strategic leadership can make the connection between the organizational learning and competency development stronger and that competency development positively influences affective commitment of Gen Y employees (part of Hypothesis 2). Further, we have posited that the interaction of organizational learning and strategic leadership influences affective commitment of Gen Y employees through the mediating effects of competency development. The reason behind this proposition is that both organizational learning and strategic leadership influence competency development of Gen Y employees, which further has a positive influence on the affective commitment. Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 3b: Competency development mediates the interactive effect of organizational learning and strategic leadership on affective commitment of Gen Y employees (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Research framework.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Sample and questionnaire design

A cross-sectional survey design is used to gather primary data. Data were collected by means of a structured questionnaire. Gen Y employees from an Indian multi-national IT organization in Delhi-NCR region are selected as respondents. NCR is one of the biggest IT hubs in India. The sample comprises of software development professionals born between 1981 and 2000. We contacted HR Managers to take their consent to participate in this research and to identify Gen Y employees based on their birth years. We administered 700 questionnaires from August 2015 to November 2015 to survey Gen Y employees. The questionnaires were administered in English language as our respondents working in IT industry possess professional qualifications from higher education institutes, hence are proficient in English language. Respondents were given 2 weeks to respond. After that time, a reminding mail was sent, again by the HR manager.

In all, 356 completely filled questionnaires were collected with a response rate of 50.85%. Out of this sample 71% are males and 29% are females, with an age group of 20–24 represented by 27% respondents, 25–29 by 57%, and 29–34 by 16%. Questionnaire items were adopted from preexisting validated scales. The population born between 1981 and 2000 is defined as Gen Y employees. The 5-point Likert scale (1=‘strongly disagree’; 5=‘strongly agree’) was used as the measurement method. The questionnaire consists of three sections namely; first section is the brief introduction and instructions along with the purpose of research and assurance of establishing the anonymity of responses. Second section includes the statements dealing with basic information of the respondents namely gender, age group, education, and years of experience; third section includes the statements on strategic leadership, organizational learning, competency development, and affective commitment. Strategic leadership is measured by an 11-item scale used by Davies and Davies (Reference Davies and Davies2010). A sample item was: ‘My leader promotes a culture of dialog, inquiry, and knowledge sharing and search for the lessons in both successful and unsuccessful outcomes.’ Responses were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1=‘strongly disagree’ to 5=‘strongly agree’ and measures Gen Y employees’ perception about their leader’s strategic leadership style. Cronbach α is found to be 0.96 and mean value is 3.5 (SD=2.12). Organizational learning is measured by using a 16-item scale by Jerez-Gómez, Céspedes-Lorente, and Valle-Cabrera (Reference Jerez-Gómez, Céspedes-Lorente and Valle-Cabrera2005). An example is ‘I am encouraged to take risks in this organization’. Cronbach α is found to be 0.96 and mean value is 2.2 (SD=1.51). Competency development is measured by using a 10-item scale of Lankau and Scandura (Reference Lankau and Scandura2002) and Liu, Liu, Kwan, and Mao (Reference Liu, Liu, Kwan and Mao2009); and evaluates the perception of Gen Y employees’ access to competency development opportunities. A sample item is ‘I have been given tasks that develop my competencies for the future’. Cronbach α for competency development is 0.90 and mean value is 3.1 (SD=1.76). Affective commitment is measured by Meyer and Allen’s (Reference Meyer and Allen1997) 6-item scale. An example is ‘I really feel as if this organization’s problems are my own’. Cronbach α for affective commitment is 0.90 and mean value is 3.1 (SD=1.98).

Controls

To avoid potentially misleading relationships between our study’s variables and to enhance the validity of the study, the probable influence of gender, experience, and education were controlled.

RESULTS

Data analysis

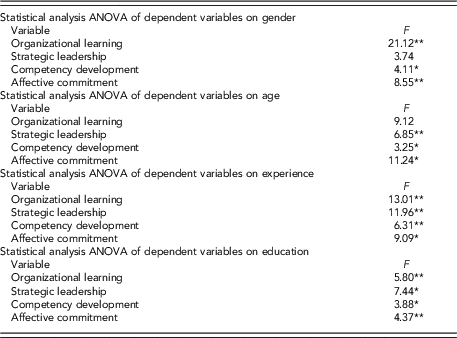

For the present study, data analysis was conducted using SPSS 21 and AMOS 7.0 software. In addition, an SPSS macro named PROCESS was used to provide various features of SOBEL, which assist in estimating an indirect effect. This method facilitates examining the significance of conditional indirect effect on different moderator variable values. First, the construct validity of the scale and overall fit of the hypothesized model were examined with maximum likelihood method, using SPSS 21 and AMOS 7.0 statistical packages. All items were factor-analyzed (principal component analysis) using varimax rotation. The eigenvalues of the unreduced item intercorrelation matrix were calculated and it was suggested that factors be extracted based on the eigenvalues greater than unity (Kaiser, 1970). For construct validation purpose, CFA was performed for all constructs (strategic leadership, organizational learning, competency development, and affective commitment). As evident from Table 3, results of CFA indicate that this model has acceptable fit indices (χ2=227.744, χ2 /df=2.332, p<.001, good-fit-index=0.924, adjusted good-fit-index=0.895, root mean square residual=0.019, normed-fit-index=0.945, CFI=0.981, IFI=0.945, RMSEA=0.029). The magnitudes of standardized loadings ranged from 0.61 to 0.91, and t-values ranging from 9.739 to 17.248 were significant. Overall goodness of fit statistics, magnitudes of standardized loadings, and the t-values provide support for convergent validity (Anderson & Gerbing, Reference Anderson and Gerbing1988). The factor loadings of all the items in the research model were >0.5. In addition, the AVE values for all study variables were between 0.870 and 0.915, which were >0.5. Thus, this measurement model possesses adequate convergent validity. Further, all inter-factor correlations with 95% confidence intervals were no more than 1.00, proving the discriminant validity (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, Reference Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham2009). Table 1 describes descriptive statistics, reliabilities, AVE, and inter-correlations of all variables. The CFA results also shows that the square roots of all the AVE values of every research construct are higher than the pairwise correlation coefficients between the selected construct and all other variables. This constitutes the favorable discriminant validity of the measurement model (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981; Hair et al., 2009) (see Table 1). Furthermore, the result reveals a 39% explained variance, which was well within the prescribed limit of 50%, the minimum threshold in accordance with Harman’s single factor test (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2012), thereby indicating that common method variance is not a potential threat for the current study. Also, the relationship between demographic variables and study constructs was examined by performing one-way ANOVA. The results of this analysis are summarized in Table 1, which presents the corresponding F-values. It is observed that age, gender, education, and experience were found to be statistically insignificant on studied constructs.

Table 1 Construct means, SD, and discriminant validity (N=356)

Note: Values in bracket in diagonal line represent square root of AVE.

Age (in years): 1=20–24 (27%), 2=25–29 (57%), and 3=29–34 (16%).

Gender: 1=male (70.23%), 2=female (29.77%).

Education: 1=intermediate (32.14%), 2=graduate (57.32%), 3=postgraduate (10.54%); experience (in years): 0–2 (16.15%), 2–4 (20.92%), 4–6 (29.09%), 6 (19.05).

*Significance level of .05 (two-tailed).

**Significance level of .01 (two-tailed).

Test of hypotheses

Hypotheses testing was performed in two-step method, wherein the first step involved the test of direct effect and the simple mediation (Hypotheses 1 and 2). While, the second step examined the moderating effect (Hypothesis 3a) and mediated moderation (Hypothesis 3b). To tackle multicollinearity, all continuous variables were mean-centered in the study (Aiken & West, Reference Allen and Meyer1991).

Test of mediation

Table 2 indicates the findings of Hypotheses 1 and 2, which revealed the direct effect of organizational learning on affective commitment of Gen Y employees (β=0.16, t=3.54, p<.01). Findings of Hypothesis 2, also showed the positive indirect effect of organizational learning on affective commitment of Gen Y employees through competency development. The indirect effect of organizational learning on affective commitment (β=0.08) was confirmed with a two-tailed significance test (assuming a normal distribution), that is the SOBEL test (SOBEL z=3.59, p<.001). Moreover, bootstrap was performed to validate the findings of SOBEL test with 95% CI, which did not contain zero (0.03, 0.17). Hence, Hypotheses 1 and 2 are supported (see Table 2).

Table 2 Regression results from simple mediation on organizational learning

Note: N=356. Bootstrap sample size ¼ 1,000, LL ¼ lower limit, UL ¼ upper limit, CI ¼ confidence interval.

Test of mediated moderation

As depicted in Table 3, findings of Hypotheses 3a supported a positive relationship between organizational learning and competency development; this relationship would be strengthened if strategic leadership was positive. Results of Table 3 indicate that the positive influence of the cross product between strategic leadership and organizational learning, on competency development was significant (β=0.15, t=4.83, p<.01).

Table 3 ANOVA table

Note:

*Significance level of .25.

**Significance level of .08.

Also, the conditional indirect effect of organizational learning on affective commitment of Gen Y employees was performed with respect to three values of strategic leadership, that is, the mean, 1 SD above, and 1 SD below the mean. Normal-theory tests (or Bootstrap) indicated that two out of three conditional indirect effects (based on moderator values at the mean and at one standard deviation above the mean) were positive and significant at 95% CI and did not contain zero. Thus, Hypothesis 3b is supported, since positive direct effect of organizational learning on affective commitment of Gen Y employees with the mediating role of competency development was observed when strategic leadership was moderate to high.

DISCUSSION

The present study is undertaken to examine the linkage between organizational learning, strategic leadership, competency development, and Gen Y employees’ affective commitment. In this vein, this study emphasized on the mediating effect of competency development and moderating effect of strategic leadership on the relationship between organizational learning and affective commitment. Findings of the hypotheses testing reveal that organizational learning has a positive relationship with Gen Y employees’ affective commitment (β=0.16, t=3.5, p<.01), indicating that higher the organizational learning, higher the affective commitment. This is due to the fact that organizational learning promotes development in Gen Y employees manifested as competency development, which creates a sense of emotional attachment with the organization. This is in agreement with past research, which reveals a positive link of organizational learning with affective commitment (Che Rose, Kumar, & Gua Pak, Reference Che Rose, Kumar and Gua Pak2009). Affective commitment is identified as an important construct of organizational psychology research. The extant literature has compelling evidence that affective commitment correlates significantly with discretionary behavior, job satisfaction, performance, productivity, motivation, and intention to stay (Mathieu & Zajac, Reference Mathieu and Zajac1990; Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1997; Huang, You, & Tsai, Reference Huang, You and Tsai2012; Borgogni, Russo, Miraglia, & Vecchione, Reference Borgogni, Russo, Miraglia and Vecchione2013).

Further, in context of Indian Gen Y employees, learning and development is very important, as they face pressure from family, friends, and relatives to progress in their professional careers. Also, IT industry demands continuous upgradation of skills and knowledge to stay marketable and enhance career opportunities Therefore, continuous learning is quintessential for Indian Gen Y from IT industry. Consequently, organization offering avenues for development generates a sense of emotional attachment from the organization. It has theoretical underpinnings from social exchange theory, which asserts that relationships develop over time based on certain ‘rules’ of exchange. In this view, when individuals receive economic and socio-emotional resources from their organization, they tend to reciprocate for the positive treatment received by getting themselves deeper into their role often manifested as positive response of higher commitment (Emerson, Reference Emerson1976).

The second hypothesis is focused on assessing the mediating effect of competency development on organizational learning and affective commitment, signifying that competency development is the key to evoke affective commitment. This is consistent with the findings of Kadiresan, Selamat, Selladurai, Ramendran, and Mohamed (Reference Kadiresan, Selamat, Selladurai, Ramendran and Mohamed2015), that an organization’s developmental opportunities to enhance employee competencies have a profound influence on affective commitment of the employees. As per a recent study (Miles & Wilson, Reference Miles and Wilson2004), Indian young generation employees lack basic skills including technical competency, communication, problem-solving, interpersonal skills, critical thinking, and personal skills. Therefore Indian IT organizations should embrace myriad types of learning interventions to enhance competency levels in Gen Y employees such as stretch assignments, secondments, lateral moves on multiple projects, international on-site assignments, social media-enabled learning, and mentoring. However, there is still a long way forward for Indian organizations, as they lag behind their foreign competitors in terms of investment for talent development initiatives (Budhwar & Sparrow, Reference Budhwar and Sparrow1997). The present turbulent and complex business environment demands flexibility and continuous learning instead of bureaucratic style of command and control (Hitt & Ireland, 2002; House & Aditya, 1997; Jansen, Vera, & Crossan, 2009). As a result, an emphasis on competency development is a crucial driving force for increasing employee effectiveness and employability, which in turn, drive organizational sustainability (Nyhan, Reference Nyhan1998).

The third hypothesis highlighted the moderating effect of strategic leadership on organizational learning and competency development of Gen Y employees, suggesting that strategic leaders being visionary and development-oriented reinforce the competency development. In any organization, top leadership support is prerequisite for organization learning and employee development. This is consistent with the study examining the relationship between strategic leadership and competency development of Gen Y employees (Naim & Lenka, Reference Naim and Lenka2015). A strategic leader exhibits a holistic orientation towards overall development of the organization. Such a leader view this environment as presenting opportunities and respond by inculcating a culture supportive to knowledge sharing, open communication creativity, innovation, and intrapreneurship by focusing on continual development and exploitation (Hilt, Haynes, & Serpa, Reference Hitt, Haynes and Serpa2010; Simsek, Jansen, Minichilli, & Esteve, Reference Simsek, Jansen, Minichilli and Esteve2015). The culture of knowledge sharing, in itself enhances competency development of Gen Y employees (Naim & Lenka, Reference Naim and Lenka2016). Also, Gen Y employees seek supportive leadership who mentor them and facilitate their development (Dulin, Reference Dulin2005). Research reveals that Gen Y responds to leaders who set direction by showing how an individual job is linked to organizational goals (Downing, Reference Downing2006). In this vein, strategic leaders create an alignment between organizational vision and strategy with individual goals, in turn maximizing the understanding of big picture and awareness of individual roles. This generates a perception of being valued by making contributions towards achieving larger organizational goals and feeling of better connected to the organizational bottom-line. This is highly desirable for Gen Y employees who continuously strive to make contributions towards the realization of organizational objectives (Hastings, Reference Hastings2008). In the Indian context, IT employees are expected to follow the instructions of their team leaders (who are also the point of contact with the clients) and imitate them as role models. Thus, strategic leaders influence team leaders, which in turn, shape the development of their subordinates. In other words, a strategic leader creates conducive environment for competency development by promoting organization learning.

Theoretical implications

Results of the present study offer significant theoretical contributions. First, competency development of Gen Y employees is the key to evoke their affective commitment. The findings reveal that strategic leadership plays a crucial role in competency development, ultimately leading to increased affective commitment of Gen Y employees. Therefore, strategic leadership and competency development act as important intervening variables between organizational learning and affective commitment. Second, this study is of the first of its kind to investigate the influence of strategic leadership on affective commitment of employees, particularly young employees-Gen Y. Third, we believe that no study till date has examined the factors that influence affective commitment of Indian Gen Y employees. This research is an attempt to take the topic of strategic leadership and affective commitment a step ahead by means of a quantitative analysis. No such study has ever focused on affective commitment of Indian Gen Y employees from IT industry using an empirical approach.

Fourth, this study contributes to the literature on strategic leadership, organizational learning, competency development, and affective commitment through external validation of the concepts developed in a western world context. In particular, there is a limited empirical literature on strategic leadership and that also emphasizes on its impact on firm innovation and performance (Carter & Greer, Reference Carter and Greer2013). In addition, this paper addresses individual outcomes of organizational learning, rather than organizational-level variables, which are widely discussed in extant literature. Also, this paper adds a new dimension (strategic leadership) to the leadership literature linking it with affective commitment as prior literature has mainly emphasized on transformational leadership’s impact on follower commitment (Katou, Reference Katou2015). Finally, improving the employee commitment levels has a strong positive influence on retention rates, which will combat the problem of high attrition among young employees.

Practical implications

This study provides various practical implications which could lead to positive employee outcomes. First, the findings suggest how top leadership support influences employee attitudinal outcomes. It further reinforces the significance of top leader behaviors on organizational outcomes such as organizational learning. Second, it provides HR managers a strategy focusing on learning and development in order to strengthen commitment and in turn, retention rates of young employees. Third, to enhance affective commitment of Gen Y employees, leaders must adopt strategic leadership style. When a leader has strategic approach, it influences organization culture to be conducive to learning and development. As a result, organization as a whole becomes a learning entity with a strategic orientation towards learning, performance, and innovation. Therefore, it is essential for organizations to nurture strategic leadership dimension into their leadership development interventions. This involves highlighting the significance of vision development and communication, development of strategic competencies, creation of effective organizational culture and processes, and alignment of people and organization (Davies & Davies, Reference Davies and Davies2010).

In addition, strategic leadership is in fitment with the dynamic nature of IT industry, as it enables to anticipate (by environment scanning to identify changes in client demands on software development projects, and opportunities); interpret (by recognizing patterns and dealing with project deadlines); and decide (by evaluating multiple options such as selecting projects of different clients) (Schoemaker, Krupp, & Howland, Reference Schoemaker, Krupp and Howland2013). Second, IT industry is one of the fastest growing industries generating 3.1 million jobs in 2013. This is despite the growing acknowledgement that a majority of Indian graduates are unemployable due to lack of basic competencies; thus it is prerequisite for IT organizations to have a strategic focus on competency development of young generation of employees, Gen Y (Naim & Lenka, Reference Naim and Lenka2017b). This will ensure a continuous supply of competent employees capable of delivering value and achieving targets, along with the higher levels of motivation, job satisfaction, and commitment. Moreover, a perception of competency development is a strong intrinsic motivation for employees, in particular for Indian Gen Y employees, who are achievement-oriented and harbor an ambition to succeed (Puybaraud, Reference Puybaraud2010). Also, committed employees are enthusiastic and eager to perform leading to higher performance, productivity, and most importantly, completion of projects within specified deadlines in conformance to quality standards. Finally, evoking positive employee attitudes of affective commitment is a predictor of intention to stay (Naim & Lenka, Reference Naim and Lenka2016). This has valuable implications for contemporary hyper-competitive global economy characterized by high talent mobility. Therefore, a significant implication of this study is designing a strategy to bolster commitment levels resulting in higher retention rates, which serves as a valuable source of competitive advantage for organizations.

Limitations and future avenues of research

Like any other research, this study is not devoid of any limitations. The first limitation is its relatively small sample size and cross-sectional nature of survey method. Hence, further research is needed to confirm our suggested relationships, as self-reported surveys are poor in measuring causality. As this study was carried out in IT industry of India, empirical findings of the study could be more applicable in Asian countries as compared with Western ones. It is better to replicate this study in public sector organization or in manufacturing sector, may be in a different country as suggested results may not be generalized. As quantitative research design has its obvious limitations so future studies should employ qualitative methods like focus interviews to further examine the results of this study. Further, it may not be a complete investigation as management perspective is not examined. Therefore, future research should interview both HR Managers and Gen Y employees to validate the study results. Further, this study will pave the way for future research work in this domain by utilizing longitudinal research design.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank my parents for their continuous blessings and unconditional support. Thanks to my supervisor for her guidance and constructive criticism. Last, but not the least, all praise to Al-Kareem for keeping me motivated throughout

About the Authors

Mohammad F Naim is presently an Assistant Professor, University of Petroleum & Energy Studies, Dehradun, India. He holds a PhD in management from Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee and has published research on a wide range of areas. Prior to that, he has completed MBA in Human resource Management and holds a bachelor degree in Biotechnology. His research interest includes talent management, HR technology and employer branding.

Usha Lenka is presently an Associate Professor, at the Department of Management Studies, Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee, India. She holds a PhD in management from the Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur and has published research on a wide range of areas. She has research experience of more than 10 years. Her research interest includes talent management, knowledge management, creativity and innovation quality management, and learning organization.