INTRODUCTION

Happiness is a high-priority life goal (Diener, Reference Diener, Kahneman, Tov and Arora2000). Given the many benefits of happiness, it has been in the focus of attention of researchers for many decades (Veenhoven, Reference Veenhoven1991; Atkinson & Hall, Reference Armstrong2011), and currently, well-being and positive attitudes such as job satisfaction, commitment or happiness are a subject of interest for researches in management (Kolodinsky, Ritchie, & Kuna, Reference Kolodinsky, Ritchie and Kuna2017; Lee, Park, & Baker, Reference Lee and Allen2017). But it is also a subject of interest for companies, which make an effort to invest in its employee’s happiness, promoting positive attitudes that result in beneficial outcomes (Smith, Reference Smith2012).

It was Maslow (1954) who initially introduced the concept of Positive Psychology to examine the notion of quality of life. Later, Seligman (Reference Seligman1999) underlined the need to respond to the ‘traditional’ perspective of psychology that lies in repairing damage using an illness model. He suggested that promoting strengths is a more powerful weapon of human functioning (Seligman, Reference Seligman2002) that benefit key work organisational outcomes. For example, Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, and Topolnytsky (Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002) and Weiss and Cropanzano (Reference Weiss and Cropanzano1996) showed that job satisfaction reduces absenteeism and improves job performance. Harrison, Newman, and Roth (Reference Harrison, Anderson, Tatham and Black2006) found that positive mood at work improves job effectiveness and cooperation. Fredrickson (Reference Fredrickson2001) evidenced that positive emotions facilitate learning and teamwork. Spence, Brown, Keeping, and Lian (Reference Spence, Brown, Keeping and Lian2014) examined the connection between feeling grateful and organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB), and Yang and Hung (Reference Yang and Hung2016) found that happier workers are more productive.

However, a history of mismatch between the definitions of different attitudinal constructs and its measurement is much more frequent than it should be (Fisher, Reference Fisher2010). Despite this critical need, early academic research on positive attitudes (Edgar, Geare, Halhjem, Reese, & Thoresen, Reference Edgar, Geare, Halhjem, Reese and Thoresen2015) fails to capture a wide and accurate measurement of positive attitudes. This is mainly due to the following reasons: first, current investigations do not explain with enough exactitude the comprehensive phenomenon of happiness, and only use narrow measures of positive attitudes (Fisher, Reference Fisher2010). Nothing but wide attitudinal measures can predict broad behaviours, such as OCB (Fisher, 1980; Harrison, Newman, & Roth, Reference Harrison, Anderson, Tatham and Black2006). Second, the incongruity between definitions and measurement of these constructs is not resolved, and the problem of overlapping of attitudinal constructs persists (Warr & Inceoglu, 2012). Third, no previous research has attempted to understand the unique dimensions of happiness at work (HAW) in a practicable way. HAW requires an ample conceptualisation: ‘Happiness at work is an umbrella concept that includes a large number of constructs’ (Fisher, Reference Fisher2010: 24). Consequently, a higher-order construct that includes different positive attitudes will be useful and necessary (Fisher, Reference Fisher2010). Our research aims to close this gap by providing a feasible and manageable measurement of HAW. On the basis of Fisher’s (Reference Fisher2010) definition of HAW, Salas-Vallina et al. (2017a) developed and validated the original HAW scale. This scale is a wide and accurate tool to explore positive employee attitudes for both theoretical and practical reasons. It provides a more integrated perspective of working life and comprises three dimensions: engagement (passion at work), job satisfaction (evaluations of job characteristics) and affective organisational commitment (feelings of belonging to the organisation). The literature provides measures for well-known constructs such as engagement (Schaufeli & Bakker, Reference Schriesheim and Tsui2004) or job satisfaction (Weiss & Cropanzano, Reference Weiss and Cropanzano1996). However, while these measures capture positive attitudes, they may be insufficient to determine various facets of HAW (Fisher, Reference Fisher2010). Interestingly, HAW antecedents have been properly analysed in previous studies: transformational leadership and organisational learning capability have been proven to affect HAW (Salas-Vallina et al., 2017a). Research has also evidenced that HAW affects OCB (Salas-Vallina et al., 2017b). Although HAW implies an advancement in research, we propose that the HAW original scale needs to be shortened in order for it to be assessed more directly. The HAW scale has strong psychometric properties, but it comprises 31 items, which is long and inefficient. Multiple-item scales have benefits such as simplicity of development, management and scoring. Even though Thomas and Petersen (Reference Thomas and Petersen1982) exposed the good internal consistency of multiple-item scales, Stanton, Sinar, Balzer, and Smith (Reference Stanton, Sinar, Balzer and Smith2002) reviewed various problems of multiitem scales. They highlighted the necessity of shorter scales in organisational research, among other reasons, because measurement instruments need to be concise to reduce the likelihood of nonresponse and redundant items (Baldus, Voorhees, & Calantone, Reference Baldus, Voorhees and Calantone2015). Long scales may promote that respondents feel ‘oversurveyed’ (Rogelberg & Luong, Reference Rogelberg and Luong1998), higher refusal rates and more missing data (Stanton et al., Reference Stanton, Sinar, Balzer and Smith2002). Also, Walsh, Albrecht, Hofacker, and Takahashi (Reference Walsh, Albrecht, Hofacker and Takahashi2016) underlined the usefulness of shortened scales. We follow three key characteristics of item quality to shorten the HAW scale on the basis of accepted methods. The objective of this study, then, is to present evidence supporting the psychometric properties of a reduced version of the HAW original measurement scale. Thus, our paper is the first to offer both a short scale of HAW and a multidimensional approach to happiness in the work context. The shortened version of HAW (SHAW) may truly capture the unique HAW dimensions via a short questionnaire.

This research is organised as follows. First, we review the concept of HAW and its antecedents and outcomes. Next, we follow a four-step process to shorten the HAW scale (creating SHAW) on the basis of the practice of Matthews, Kath, and Barnes-Farrell (Reference Matthews, Kath and Barnes-Farrell2010), Kacmar, Crawford, Carlson, Ferguson, and Whitten (Reference Kacmar, Crawford, Carlson, Ferguson and Whitten2014) and Sharma, Sharma, and Agarwal (Reference Salas-Vallina, Alegre and Fernández2016). In Step 1, we select the items that compose SHAW and compare the connection between HAW dimensions. In Step 2, we verify the factor structure of HAW. In Step 3, we examine the type of correlations between SHAW and its theoretically proper antecedents. Finally, in Step 4, we explore the correlations of SHAW and theoretically pertinent outcome constructs. Finally, we discuss and interpret the results and limitations.

HAW

The term ‘happiness’ is not an unambiguous concept and has been defined in different ways (Kesebir & Diener, Reference Kesebir and Diener2008). The two main perspectives are the hedonic and the eudemonic. The hedonic approach refers to pleasant feelings and the affect balance and is represented by the subjective well-being research (Diener & Seligman, Reference Diener and Seligman2004). In contrast, the eudemonic perspective interprets happiness as doing what is right in order to have a fulfilling life, and follow self-concordant objectives, indifferent to feelings (Warr, Reference Warr2007). Happiness can be defined as global judgements of one’s life, satisfaction with personal life, the prevalence of positive moods and emotions, and low levels of negative affect (Kesebir & Diener, Reference Kesebir and Diener2008).

In the social sciences, happiness is commonly considered in the sense of well-being (Higgs & Dulewicz, 2014) which is viewed as the core of positive organisational behaviour (Seligman, Reference Seligman1999). Positive organisational behaviour, emerged as a result of the shift of attention from the study of negative behaviours to the study of positive ones (Seligman, Reference Seligman1999). While the prevailing theories considered that the individual is a passive subject that only responds to stimuli, positive organisational behaviour theory contemplates individuals as decision makers, with judgements, opinions and the opportunity to be effective experts (Seligman, Reference Seligman2002). Positive organisational behaviour is defined as ‘the study and application of positively oriented human resource strengths and psychological capacities that can be measured, developed, and effectively managed for performance improvement in today’s workplace’ (Luthans, Reference Luthans2002: 59), and is considered a powerful weapon to promote strengths and to build the best quality of life. Positive organisational behaviour highlights the importance of more focussed theory development and research on the positive traits, states and behaviours of employees in organisations (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2008). Positive organisational behaviour research follows the scientific method to manage the unique problems that human behaviour presents in all its complexity.

Closely connected with positive organisational behaviour theory, the Job Demands-Resources theory states that job demands (tasks that require effort) lead to negative attitudes (burnout), and job resources (physical, psychological, social or organisational characteristics) result in positive attitudes, such as engagement (Schaufeli & Bakker, Reference Schriesheim and Tsui2004). It is clear that attitudes are crucial for organisations: job satisfaction reduces absenteeism (Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002) and improves job performance (Weiss & Cropanzano, Reference Weiss and Cropanzano1996); positive mood at work improves job effectiveness, cooperation (Harrison, Newman, & Roth, Reference Harrison, Anderson, Tatham and Black2006), creativity and results (Baas, De Dreu, & Nijstad, Reference Baas, De Dreu and Nijstad2008); and positive emotions facilitate learning and teamwork (Fredrickson, Reference Fredrickson2001). On a personal level, happy feelings imply success in life, higher life expectancy and health (Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, Reference Lyubomirsky, King and Diener2005). However, the link between attitudes and behaviours is weak because only exist narrow measures of attitudes (Fisher, Reference Fisher2010), and wide attitudinal measures are required to better predict behaviours (Fisher, 1980; Harrison, Newman, & Roth, Reference Harrison, Anderson, Tatham and Black2006). Research also shows that there are too many measures related to positive attitudes Warr (Reference Warr2007), some of them overlapping, with a lack of studies that compare the diverse shapes of well-being (Warr & Inceoglu, 2012). For example, the most well-known positive attitudinal concept, job satisfaction, refers to evaluations of job conditions (Moorman, Reference Moorman1993). Another example is engagement, which specifically measures positive affectivity related to work, such as commitment, enthusiasm, energy and so forth (Macey & Schneider, Reference Macey and Schneider2008). Involvement exclusively refers to the degree to which the job becomes an essential part of an individual’s life. Organisational commitment is constrained to measure the engagement with the company, and apart from cognitive aspects, it can include affective aspects when measured with the Allen and Meyer (Reference Alvesson and Willmott1990) scale.

Because measures of happiness in the work context needed to provide a sufficiently explanatory measurement, Fisher (Reference Fisher2010), identified the need for a measure that comprised the work itself (affective implication and feelings at work), job characteristics (evaluative judgements of job characteristics, such as salary, supervision, career opportunities) and the organisation as a whole (feelings of belonging to the organisation). A reliable and valid measure of human strengths was needed to understand how these strengths grow (Seligman, Reference Seligman2002). Harrison, Anderson, Tatham, and Black (Reference Hartmann and Bambacas2014) highlighted the need of a higher-order construct to measure positive attitudes, suggesting at least three well-known and widely checked constructs. Salas-Vallina, Alegre and Fernández (2017a, Reference Schaufeli and Bakker2017b) developed and statistically validated the HAW scale, beginning with Fisher’s conceptualisation of HAW. They defined HAW on the basis of three dimensions (Table 1), that combine high pleasure and high activation (Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Ilies, Reference Xanthopoulou, Bakker and Ilies2012): engagement, job satisfaction and affective organisational commitment. This broad perspective is supported by Harrison, Newman, and Roth (Reference Harrison, Anderson, Tatham and Black2006), who argued that ‘when attempting to understand patterns of work behaviour from attitudes such as job satisfaction and organisational commitment, researchers should conceptualize the criterion at a high level of abstraction’ (Harrison, Newman, & Roth, Reference Harrison, Anderson, Tatham and Black2006: 316). Our approach lays on a similar premise to Harrison et al., but also incorporates engagement as an essential employee attitude. The HAW construct is also sustained by Warr (Reference Warr2013) vitamin model, which suggests that happiness depends not only on job characteristics (job satisfaction) but also on within-person mental processes (engagement). In addition, the literature on positive attitudes shows that employee attitudes depend on both individual characteristics and work context. HAW captures both points of view. Wright, Moynihan, and Pandey (Reference Wright, Moynihan and Pandey2012) drew up a model in which organisational characteristics (aspects of the organisational setting, such as organisational-level conflict or role clarity) influence employee attitudes, which seconds the relevance of HAW.

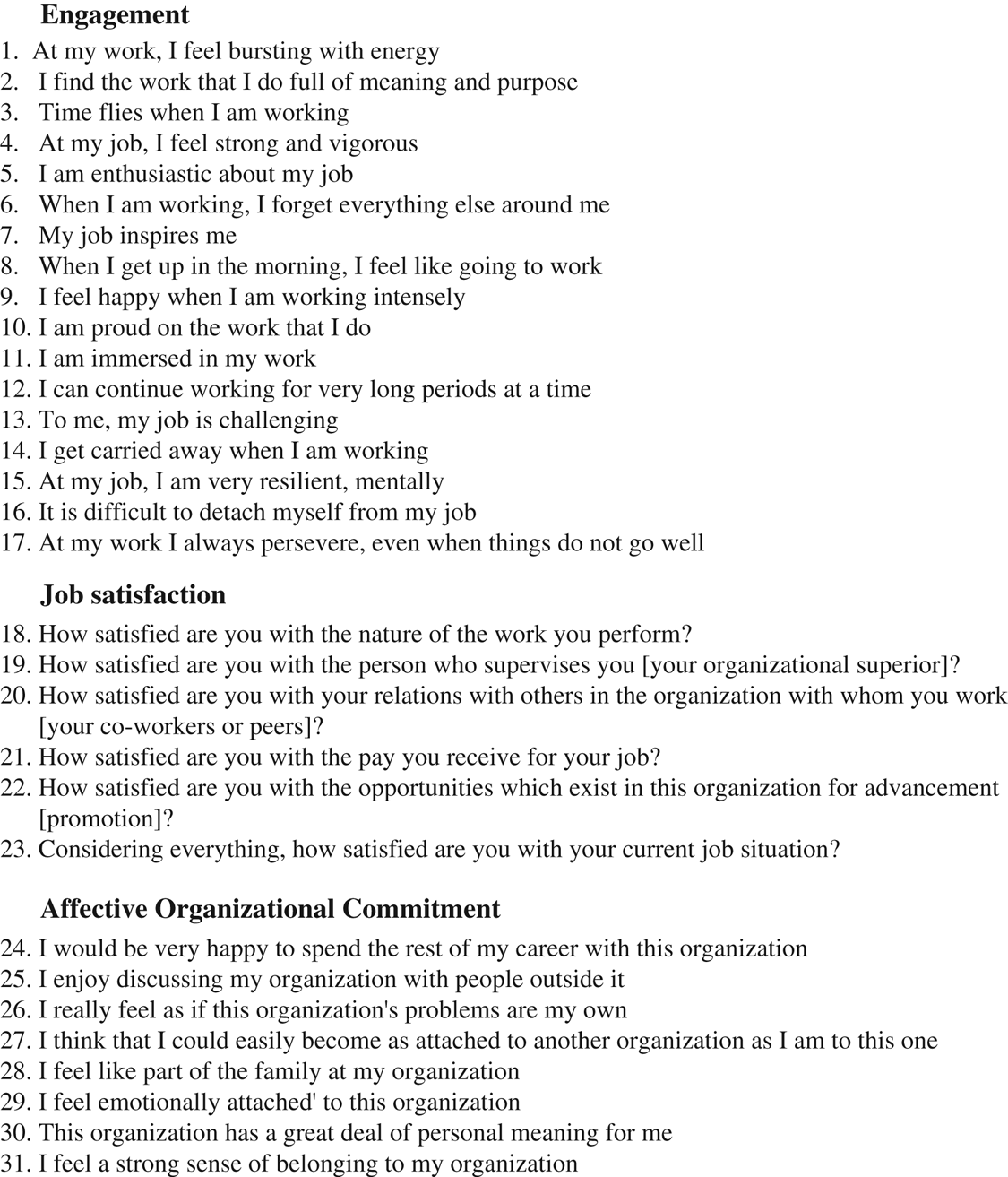

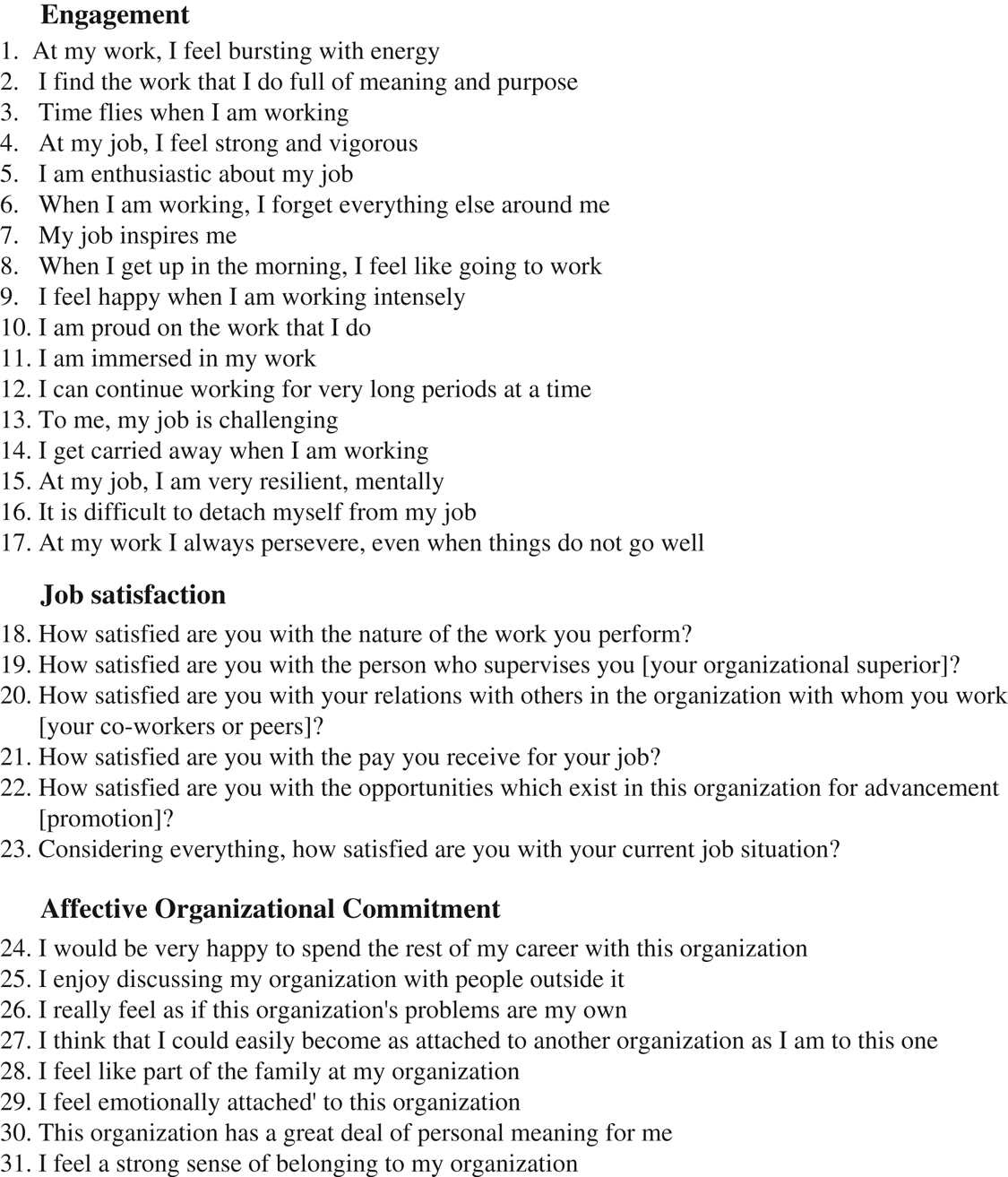

Table 1 Happiness at work dimensions

Engagement

The work itself, measured through engagement, aims to capture enthusiasm, passion, thrill at work and positive mental states related to vigour, dedication and absorption. Kahn (Reference Kahn1990) defined personal engagement as ‘the harnessing of organisation member’s selves to their work roles: in engagement, people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, emotionally and mentally during role performances’, stating that it is ‘the behaviour by which people give themselves to their work’ (Kahn, Reference Kahn1990). Engagement is a special feeling of energy and motivation related to thrill and passion at work. Following Warr and Inceoglu (Reference Warr and Inceoglu2012), engagement is a highly energising and stimulating well-being state. We understand engagement in the same way as Warr and Inceoglu (2012), and Schaufeli et al. (2010), related to the Zigarmi, Nimon, Houson, Witt, and Diehl (Reference Zigarmi, Nimon, Houson, Witt and Diehl2009) engagement concept of ‘Employee Work Passion’: engagement is a special feeling of energy and motivation related to the capacity to feel thrilled, vibrant, excited or passionate at work. Therefore, engagement refers to feelings resulting from meaningfulness at work.

Job satisfaction

Job characteristics, measured though job satisfaction, aim to evaluate job conditions. Locke (Reference Locke1976) defined job satisfaction as ‘a positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences’. This concept is considered to be a central concept in organisations (Chiva & Alegre, Reference Chiva, Alegre and Lapiedra2009) and, to date, it has been related to job performance (Weiss & Cropanzano, Reference Weiss and Cropanzano1996). Some measurement scales of job satisfaction introduce information that is within the concept of engagement, such as the Brayfield and Rothe (Reference Brayfield and Rothe1951) scale, or the Job Descriptive Index (Smith et al., 1969).

Unlike engagement, which is related to the employee’s mood at work (enthusiasm, activation), job satisfaction refers to judgements about work as a result of job characteristics (joy, gladness). Job satisfaction is understood as adequacy, sufficiency, acceptability or suitability. It evaluates employees’ feelings about working conditions, such as salary, career opportunities or relationships with peers. It is a passive and reactive concept that shows and measures whether we achieve what we want in terms of work conditions. Moorman (Reference Moorman1993) stated that job satisfaction evaluates conditions, opportunities or outcomes, which differentiates job satisfaction from engagement. Through the Schriesheim and Tsui (Reference Sharma, Sharma and Agarwal1980) questionnaire, which was used in the original HAW scale, information was gathered about judgements of job characteristics (i.e., ‘how satisfied are you with the person who supervises you?’; ‘How satisfied are you with the pay you receive for your job?’). However, satisfied workers could not be made to engage.

Affective organisational commitment

The organisation as a whole, measured through affective organisational commitment, considers affective feelings at work and continuance and normative commitment to work. Affective organisational commitment takes the whole organisation as a reference, measuring affection for the organisation, monetary evaluation of belonging to the organisation, and feelings of responsibility to the organisation (i.e., ‘I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organisation’; ‘I feel a strong sense of belonging to my organisation’). The concept of organisational commitment is defined as ‘employees interest and connection with an organisation’ (Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1997). Meyer et al. (Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002) stated that affective commitment is strongly related to important organisational variables, such as job performance. Meyer and Allen’s model has three components: affective, continuance and normative commitment. Affective commitment refers to emotional links, identification and involvement in the organisation (Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002). Continuance commitment is related to the perceived costs to the employee if she or he leaves the organisation (Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1984). Normative commitment is the obligation the employee feels to stay within the organisation (Allen & Meyer, Reference Alvesson and Willmott1990).

HAW may be particularly meaningful because it is a broad enough concept to overcome the compatibility principle, which facilitates the connection between attitudes and behaviours, such as HAW and OCB (Salas-Vallina, Alegre, & Fernández, Reference Schaufeli and Bakker2017b). Further, the Job Demands-Resources theory shows that work resources increase engagement (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007), and Llorens, Schaufeli, Bakker, and Salanova (Reference Llorens, Schaufeli, Bakker and Salanova2007), in a longitudinal study, demonstrated a positive gain spiral in which engagement increases task resources over time. Therefore, a mutual relationship between HAW dimensions is found, implying that HAW is composed of three constructs with mutual feedback. These constructs have both affective and cognitive components. Affective elements refer to feelings towards the target, while cognitive components refer to an individual’s beliefs or thoughts about an attitude target, which is distinct, for example, from job satisfaction (Fisher, Reference Fisher2000).

It must be stressed that there are considerable differences between HAW and well-being. There are two main research streams that represent the concept of well-being, namely, psychological well-being and subjective well-being. Psychological well-being, whose main exponent is Carol Ryff (1989), refers to eudaimonic aspects in life, such as personal growth, purpose in life, self-acceptance, environmental mastery, positive relationships and autonomy. Later, Ryan and Deci (2001) and Huppert and So (2013) continued to develop this approach, which argues that hedonic theories are inadequate to describe the Good Life (Ryan & Deci, 2001). The second view of the concept, subjective well-being, has three main components, two affective elements (positive and negative affect) and one cognitive element (life satisfaction) (Diener, Reference Diener1984). Subjective well-being researchers consider that happiness is an internal state of subjective evaluations about the quality of one’s life (Kashdan et al., 2008). This perspective further emphasises the hedonic and subjective aspects of well-being. Literature suggests that hedonic happiness understood as the mere pursuit of pleasure, is not sustainable over the long term without eudaimonic well-being (Kashdan et al., 2008; Fisher, Reference Fisher2010). The concept of HAW, measured by means of SHAW, goes one step beyond well-being for different reasons. First, it includes both hedonic and eudaimonic elements. On the one hand, engagement comprises cognitive and eudaimonic elements, and on the other, affective and subjective aspects. Job satisfaction mainly includes eudaimonic elements. Affective organisational commitment involves eudaimonic and hedonic components of well-being. Second, HAW is a broad enough concept to capture much of the variance in person-level happiness in organisations (Fisher, Reference Fisher2010). Third, SHAW might better explain behaviours, given that attitude precedes behaviours, and behaviours need broad-based attitudinal measures to be precisely explained (Harrison, Newman, & Roth, Reference Harrison, Anderson, Tatham and Black2006).

There are different scales within the positive organisational behaviour field, such as the one by Singh and Aggarwal (2017) and Lyubomirski and Lepper’s (1999) subjective happiness measurement scale. The former focusses exclusively on subjective well-being whilst the latter is a short, operative scale, yet is different on several counts when compared to the SHAW scale. First, Lyubomirski and Lepper developed a scale based exclusively on the subjective approach of well-being (Lyubomirki & Lepper, Reference Lyubomirsky and Lepper1999), which highlights hedonic elements. In contrast, the SHAW scale includes objective elements (working conditions) and cognitive aspects, besides subjective ones. Second, Lyubomirski and Lepper’s scale measures happiness in general, while the SHAW measurement scale focusses on the work context. Therefore, Lyubomirski and Lepper’s scale brings little information about the determinants of happiness in working life. Third, Lyubomirski and Lepper’s scale includes four items that ask about the respondents’ general level of happiness (i.e., ‘Some people are generally very happy. They enjoy life regardless of what is going on, getting the most out of everything. To what extent does this characterization describe you?’). This type of questions may entail problems in the quality of responses, as the concept of happiness might be interpreted in different ways depending on the respondent. Conversely, SHAW does not directly ask about happiness, instead, it fields questions such as ‘I feel a strong sense of belonging to my organization’, which is expected to be much more precisely answered by the respondents.

SCALE REDUCTION AND VALIDATION PROCEDURE

Self-report scales are a commonly used method for data collection (Sackett & Larson, Reference Sackett and Larson1990). Standard organisational surveys contain measures of different constructs that contain multiple items. Although multiitem scales are easy to develop and administer (Thomas & Petersen, Reference Thomas and Petersen1982), research has highlighted problems with them. Such is the case of the HAW scale, which consists of three dimensions and a total of 31 items. Rogelberg and Luong (Reference Rogelberg and Luong1998) showed that many employees feel ‘oversurveyed’, which could have negative consequences for response rates. Respondents could negatively perceive items that seem redundant or of minor importance. More motivated respondents imply higher response rates and better data (Rogelberg & Luong, Reference Rogelberg and Luong1998), and better wording improves the quality of items (Holden & Fekken, Reference Holden and Fekken1990). Stanton et al. (Reference Stanton, Sinar, Balzer and Smith2002) proposed a procedure for scale reduction based on three-item categories: internal, external and judgemental. Internal qualities are those that can be examined in comparison to other items on the scale or the global scale scores. External qualities represent links between the items or the scale with other constructs. Judgmental qualities allude to a subjective assessment of items, which is based on researchers’ knowledge (Kacmar et al., Reference Kacmar, Crawford, Carlson, Ferguson and Whitten2014). Our research shortens the original HAW scale, which consists of three dimensions and 31 items. Although the HAW scale overcomes the psychometric properties of dimensionality, reliability and validity, a shorter version is needed. The current length of the HAW scale may cause problems with lower response rates and is more complex to administer than a shorter one (Stanton et al., Reference Stanton, Sinar, Balzer and Smith2002). We follow Stanton et al. (Reference Stanton, Sinar, Balzer and Smith2002) and Kacmar et al. (Reference Kacmar, Crawford, Carlson, Ferguson and Whitten2014) methodology to shorten the HAW original scale in four steps. Two international and diversified samples (N1=234; N2=251) were used to shorten the original HAW scale. This guarantees a more robust analysis and stronger results. Composite and heterogeneous samples were obtained from different occupational sectors, such as physicians, nurses, teachers or banking employees, across Spain and Italy. The first sample was used to measure the long HAW version, and following select the items of the SHAW scale. The second sample included the SHAW scale, in order to compare the results with the first sample, as explained later. Table 2 shows the gender distribution, educational level and age of both samples.

Table 2 Gender, educational level and age

The sample size exceeds the size of previous scale development papers (Fernandez-Lores, Gavilan, Avello, & Blasco, Reference Fernandez-Lores, Gavilan, Avello and Blasco2015). Data were gathered from an electronic questionnaire, with the appointment of the head of the medical service. In the first step, we explore both the internal and judgemental qualities of the original items, selecting those to be conserved for the shortened scale, following Matthews, Kath, and Barnes-Farrell (Reference Matthews, Kath and Barnes-Farrell2010) implementation. It consists of evaluating internal qualities (item-level statistics) and judgemental qualities (nonstatistical aspects) from the first sample. In Step 2, we confirm the factor structure, conducting a confirmatory factor analysis. In Step 3, we check external qualities, examining whether the shortened scale works accurately with the antecedents of the long version of the scale. Finally, in Step 4, we analyse if the shortened scale behaves correctly with the long scale’s outcome variables.

Step 1: Scale reduction

Method

The first sample (N1=234) was used to both assess HAW and the SHAW. The HAW scale was developed by Salas-Vallina, Alegre, and Fernández (Reference Salas-Vallina, Alegre and Fernández2017a), which is composed of three dimensions. The theoretical discussion of the HAW scale has been developed in previous research (Salas-Vallina, Alegre, & Fernández, Reference Salas-Vallina, Alegre and Fernández2017a), in which HAW derives from (1) engagement, which is measured using the Utrech Work Enthusiasm Scale (UWES) (Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Roma, & Bakker, Reference Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Roma and Bakker2002), and consists of 17 items ranging from 1=‘never’, to 6=‘always’. Cronbach’s α of engagement was 0.91. (2) Job satisfaction, which is measured using Schriesheim and Tsui’s (Reference Sharma, Sharma and Agarwal1980) scale, and includes six items ranging from 1=‘totally disagree’, to 5=‘totally agree’. Cronbach’s α of job satisfaction was 0.94. (3) Affective organisational commitment, which is measured by means of Allen and Meyer’s (Reference Alvesson and Willmott1990) scale, and contains eight items ranging from 1=‘totally disagree’, to 5=‘totally agree’. Cronbach’s α of affective organisational commitment was 0.90. SHAW was measured by means of nine items, selected from the original HAW scale.

Results

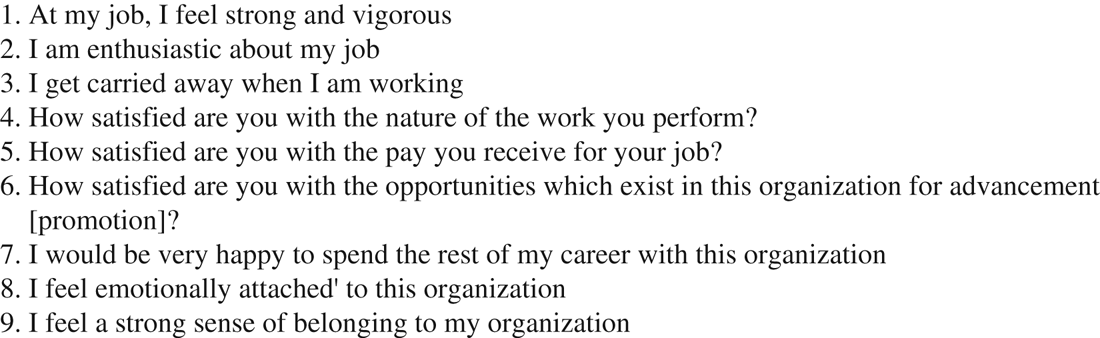

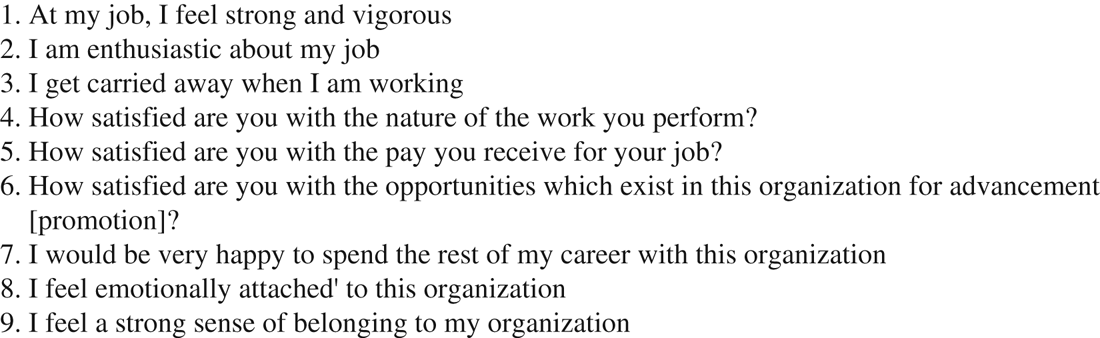

We must ensure that HAW dimensions accurately follow their theoretical definitions. To this end, we rely on our knowledge and research experience of the construct. A quality selection criterion combined with professional judgement, and not necessarily a factor loading criteria, works properly for both external relations and internal consistency (Stanton et al., Reference Stanton, Sinar, Balzer and Smith2002). Our research group chose a group of three items that best captured the content area of the dimension (Matthews, Kath, & Barnes-Farrell, Reference Matthews, Kath and Barnes-Farrell2010). After reviewing the literature on well-being, engagement, job satisfaction and commitment, we selected the items that we agreed best represented the construct, avoiding repetition and concept overlapping. Figure 1 shows HAW 31 items and Figure 2 shows SHAW selected items.

Figure 1 Happiness at work measurement scale items

Figure 2 Shorted happiness at work scale selected items

The original engagement scale consists of three subdimensions, namely vigour, dedication and absorption. We selected one item for each subdimension: item 4 (‘At my job, I feel strong and vigorous’, ENG1), item 5 (‘I am enthusiastic about my job’, ENG2) and item 14 (‘I get carried away when I am working’, ENG3), were item 4 represents vigour, item 5 represents dedication and item 14 represents absorption. The three items are focussed on capturing feelings of vigour, energy, passion at work.

For job satisfaction, we selected item 18 (‘How satisfied are you with the nature of the work you perform?’, JS1), item 21 (‘How satisfied are you with the opportunities which exist in this organization for advancement [promotion]?’, JS2) and item 22 (‘Considering everything, how satisfied are you with your current job situation?’, JS3). These items focus on general and wide questions, combined with job characteristics questions that we judged they accurately represent the construct (objective evaluations of the job). For affective organisational commitment, we chose items 24 (‘I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization’, AOC1), 29 (‘I feel emotionally attached’ to this organization’, AOC2) and 31 (‘I feel a strong sense of belonging to my organization’, AOC3).

These items clearly gather the sense of the construct, as they focus on emotional attachment and feelings of belonging to the organisation. Next, we conducted an iterative process to check item reduction. First, the items were selected on the basis of face validity by a group of experts in the research field. Then, the selected item was regressed on the remaining items and the item with the highest β value was added to the first item. Next, the sum of these two items was regressed on the remaining items and the item with the highest β was added to both of the previously selected items. This iterative process finished when no significant variance was found. In addition, literature considers that three items for each dimension are an accurate number, as it is the minimum number of items for a viable analysis (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001).

Then, we determined the Cronbach’s αs of both the SHAW and the original HAW scale to guarantee adequate reliability. Table 3 shows satisfactory reliability results and robust correspondence (0.980) between the original and SHAW forms. Next, we assessed discriminant validity is correlating the SHAW with HAW dimensions of engagement, job satisfaction and affective organisational commitment, following accepted methods (Kacmar et al., Reference Kacmar, Crawford, Carlson, Ferguson and Whitten2014). The correlations of the SHAW scale with these dimensions were strong and positive. We also verified that the original and SHAW scale worked similarly with engagement, job satisfaction and affective organisational commitment. To this end, we ran a Fisher r-to-z transformation to identify divergences in correlations (Cohen & Cohen, Reference Cohen and Cohen1983). Table 4 shows no significant differences between the original and SHAW scale and the dimensions of engagement, job satisfaction and affective organisational commitment.

Table 3 Descriptive statistics, correlations and reliabilities

Note. Cronbach’s αs appear on the diagonal.

AOC=affective organisational commitment; ENG=engagement; HAW=happiness at work; JS=job satisfaction.

**p<.01, ***p<.001.

Table 4 Comparison of correlations between the original and shortened forms of the happiness at work (SHAW) scale and engagement (ENG), job satisfaction (JS) and affective organisational commitment (AOC)

Note. ***p<.001.

Discussion

In Step 1, we generated a short form of the HAW scale consisting of nine items (three items for each dimension). SHAW presents satisfactory reliability and has similar properties to the HAW scale in terms of its dimensions of engagement, job satisfaction and affective organisational commitment. In Step 2, we validate the factor structure of the SHAW scale.

Step 2: Confirm factor structure

Method

A new sample (N2=251) was used to confirm SHAW’s factor structure. To evaluate the psychometric properties of SHAW, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis using EQS. In congruence with accepted methods (Gerbing & Anderson, Reference Gerbing and Anderson1988), we assessed dimensionality, reliability, content validity, convergent validity and discriminant validity. SHAW is a second-order factor and comprises three dimensions: engagement (ENG), job satisfaction (JS) and affective organisational commitment (AOC). Three items represented each SHAW dimension, for a total of nine items. Dimensionality refers to the adequate factorial structure in designing the SHAW scale. Reliability allows us to confirm the level of quality of the measurement scale (considering random error). Validity ensures that the scale measures what it is intended to measure.

Results

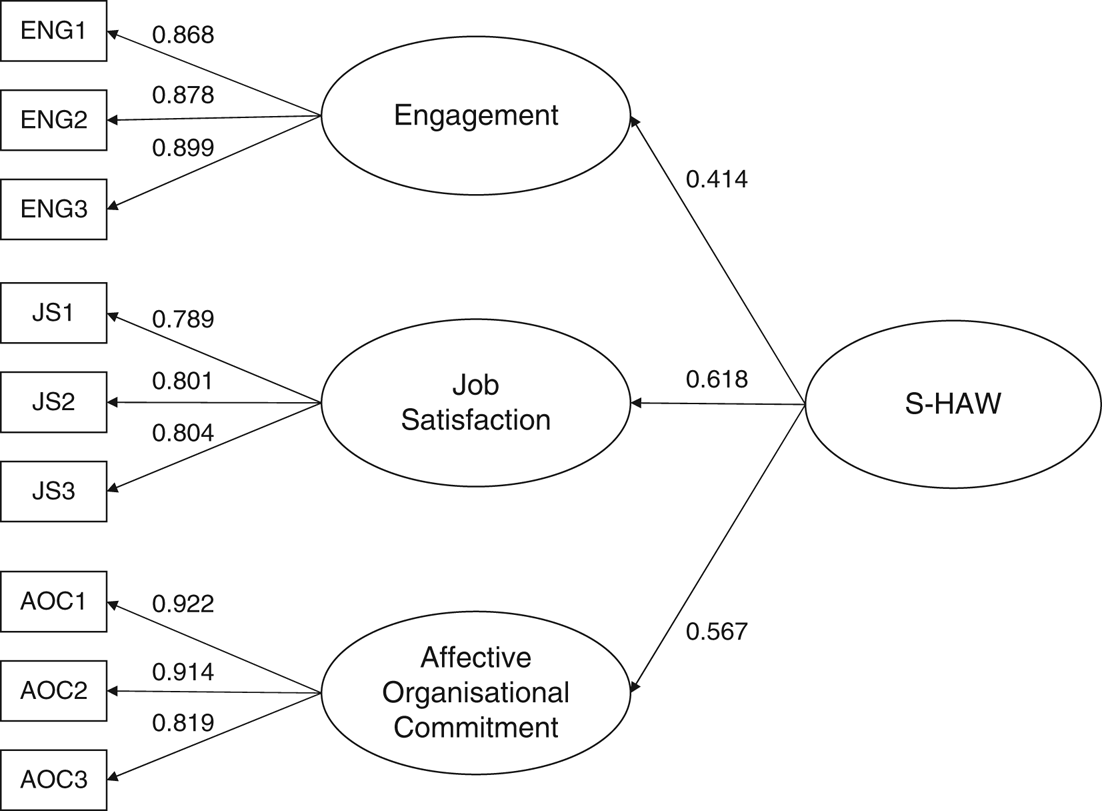

To verify the dimensionality of the SHAW higher-order construct, we ran a second-order confirmatory factor analysis. All factor loadings were significant (Table 5), and the results revealed, in absolute terms, a good fit; the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), was close to 0 (0.048), the Bentler and Bonet Normed Fit Index (BBNFI) was higher than 0.992 (0.990), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) was close to 1 (0.996) and the normed χ2 (the ratio of the χ2 to the df) had a value below 4 (2.418), yielding a very good fit (Hair et al., 2014). Figure 3 shows confirmatory factor analysis results and Table 5 shows the global fit indicators of the model.

Figure 3 Confirmatory factor analysis for the shortened version of happiness at work (SHAW). AOC=affective organisational commitment; ENG=engagement; JS=job satisfaction

Table 5 Fit values of the happiness at work (HAW) second-order factor model

Note. BBNFI=Bentler and Bonet Normed Fit Index; CFI=Comparative Fit Index; NC=normed χ2; RMSEA=root mean square error of approximation; SHAW=shortened version of HAW.

All loadings for the second-order factors are significant at p<.01.

Reliability is defined by Hair et al. (2014) as ‘the ratio of the true score’s variance to the observed variable’s variance’. We used composite reliability values and R 2 values to check reliability; all the values fell within the recommended range at above 0.50, and composite reliability values were above 0.70 (Table 5 and Figure 2). We can, therefore, confirm the reliability of the measurement scales for each dimension of HAW (Table 6).

Table 6 Shortened version of happiness at work composite reliability, variance extracted, standardized loadings, the reliability of indicators and measurement error

Note. The parameter was equalled to 1 to fix the latent variable scale. Parameter estimates are standardized.

All parameter coefficients are statistically significant (**p<.01).

Validity ensures that the scale measures what it intends to measure. We checked content, convergent and discriminant validity. We affirm that there is content validity if the scale items represent the construct and they are easy to respond to. Both the dimensions and the items of SHAW are based on previously validated scales (Hartmann & Bambacas, Reference Harrison, Newman and Roth2000; Schaufeli et al., Reference Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Roma and Bakker2002; Vigoda & Cohen, Reference Vigoda and Cohen2002) (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Composite reliability (CR) formula. λ (lambda) is the standardized factor loading for item i and ε the respective error variance for item i. The error variance (ε) is estimated based on the value of the standardized loading (λ)

Convergent validity shows that the measure used has a high correlation with other measures that evaluate the same concept. It was evaluated using the BBNFI indicator and the factor loadings estimated in the confirmatory factor analysis. In Table 5, the BBNFI index lies above 0.90 (Ahire, Golhar, & Waller, Reference Ahire, Golhar and Waller1996), the factor loadings are above 0.4 (Hair et al., 2014) and the t-values are superior to 1.96 (Anderson & Gerbing, Reference Anderson and Gerbing1982) (Table 7).

Table 7 Pairwise confirmatory analyses

Discriminant validity warrants that all dimensions that make up the construct are different from each other (Gatignon, Tushman, Smith, & Anderson, Reference Gatignon, Tushman, Smith and Anderson2002). We checked discriminant validity using pairwise confirmatory factor analysis. It consists of comparing two models, one of which was estimated by constraining the correlation to 1. The results show (Table 8) that the model fits better for all pairs of constructs where the correlation is not equal to 1, confirming that the two constructs are distinct from each other, although they may be significantly correlated (Bagozzi, Yi, & Phillips, Reference Bagozzi, Yi and Phillips1991). We also found that all correlation coefficients were significant and below 0.9 (Del Barrio & Luque, Reference Del Barrio and Luque2000), which also ensures discriminant validity.

Table 8 Comparison of correlations between the original (sample 1) and shortened (sample 2) happiness at work (HAW) scales and antecedent variables

Note. AOC=affective organisational commitment; ENG=engagement, JS=job satisfaction; SHAW=shortened version of HAW.

*p<.05, **p<.01.

We also conducted Harman’s single-factor test (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Moorman and Fetter2003) to assess whether common method variance exists. This test allows us to check if responses are affected by social desirability. The results of the confirmatory factor analysis with the indicators loading into a single factor (χ2 161.392; CFI=0.886; RMSEA=0.186; BBNFI=0.913; BBNNFI=0.886; χ2/df=6.725) suggested a poor fit, meaning that a single factor does not account for all of the variances in the data. In addition, the variance extracted for each dimension (Tables 5 and 6) is above the squared correlation of a construct with any of the others composing SHAW scale (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), which confirms discriminant validity. Therefore, we can conclude that SHAW consists of three distinct dimensions. Pairwise confirmatory factor analysis is a stringent test, which was complemented with Harman’s single-factor test. Both confirmed that SHAW dimensions show significant distinctions to deserve considering each as a separate and unique variable.

Discussion

Steps 1 and 2 confirm that SHAW works similarly as the original version. In Steps 3 and 4, we examine the external qualities of SHAW by analysing it in terms of the antecedents of the original HAW scale (Stanton et al., Reference Stanton, Sinar, Balzer and Smith2002).

Step 3: Antecedents

Method

To assess the external qualities of SHAW, we first examined its correlation with antecedents from the nomological network. We obtained the r-to-z Fisher transformation using the first sample (N1=234), in order to determine if the original and SHAW scale versions significantly differed in their correlations with HAW antecedents.

Competence, autonomy and relatedness have been proved to be antecedents of positive attitudes (Reis et al., 2000). Pekrun et al. (2006) found that performance-approach goals promote intrinsic motivation. Kindness, gratitude, optimism, curiosity, humour and open-mindedness are also important contributors to happiness (Seligman, Reference Seligman2002). In the organisational context, Hackmand and Oldham (1975) argued that task significance, skill variety, task identity, feedback from the job and autonomy produce positive work attitudes. The more developed view of Morgeson and Humphrey (2006) suggested 21 motivational factors, including social and work context factors (task significance, task variety, skill variety, feedback from others, work conditions, social support, etc.). Warr (Reference Warr2007) provided a different typology of job characteristics that promote positive attitudes, such as supportive supervision, equity, environmental clarity and opportunity for skill use. Fisher (Reference Fisher2010) and Pryce-Jones and Lindsay (2014) highlighted that leaders’ behaviour might be related to employee happiness. For example, it has been found that charismatic leadership promotes subordinate job satisfaction (DeGroot, Kiker, & Cross, Reference DeGroot, Kiker and Cross2000), and trust in the leader predicts satisfaction and commitment (Dirks & Ferrin, Reference Dirks and Ferrin2002). Previous research has also evidenced a direct and positive relationship between transformational leadership and HAW (Salas-Vallina, Alegre, & Fernández, Reference Salas-Vallina, Alegre and Fernández2017a), in line with Mathieu, Fabi, Lacoursière, and Raymond (Reference Mathieu, Fabi, Lacoursière and Raymond2016) model, in which transformational leadership is positively related to employee’s commitment and job satisfaction. We measured transformational leadership using Rafferty and Griffin’s (Reference Rafferty and Griffin2004) adaptation of the Podsakoff scale (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Moorman, & Fetter, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff1990). This scale comprises the dimensions of vision (‘has a clear understanding of where we are going’), inspirational communication, intellectual stimulation, supportive leadership and personal recognition.

Another construct that influences HAW is organisational learning capability (Salas-Vallina, Alegre, & Fernández, Reference Salas-Vallina, Alegre and Fernández2017a). It has been proven that organisational learning capability mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and HAW. The scale validated by Chiva, Alegre, and Lapiedra (Reference Chiva and Alegre2007) was used to measure organisational learning capability. The scale measures the five factors of organizational learning capability (OLC) defined by Chiva, Alegre, and Lapiedra (Reference Chiva and Alegre2007) through items such as ‘people are encouraged to interact with the environment: competitors, customers, technological institutes, universities, suppliers etc.’.

Results

We provide correlations between the HAW original and shortened scales and antecedents of HAW in Table 7. Columns 1 and 2 evidence that the correlations between the HAW scale (using sample 1), SHAW (using sample 2) and its antecedents (transformational leadership and organisational learning capability) are very similar. Fisher’s r-to-z transformation in column 3 shows that the differences in correlations are not significant (z<1.96). The pattern of results for the dimensions reveals that both the original and shortened forms’ dimensions correlate similarly with HAW antecedents, considering the two different samples.

Discussion

Step 3 provides evidence that HAW antecedents work similarly in the original and SHAW scales. Although HAW dimensions correlate nearly identically with HAW antecedents, it is interesting to observe that some are strongly related to each dimension (i.e., engagement correlates more strongly with organisational learning capability, while job satisfaction correlates more strongly with transformational leadership, for both samples).

Step 4: Outcomes

Method

We also evaluated external qualities of SHAW by comparing its correlation with HAW outcomes. We obtained the r-to-z Fisher transformation to determine whether the original and SHAW significantly differ in their correlations with HAW outcomes.

Past research found a reduced intention to quit as a consequence of job satisfaction and commitment (Meyer et al. (Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002). OCB was found to emerge as a result of higher job satisfaction and commitment levels (LePine et al., 2002). Happier employees are more predisposed to learn (Singh & Aggarwal, Reference Singh and Aggarwal2017). Moreover, the ‘Holy Grail’ of organisational behaviour research lies in the positive relationship between job satisfaction and job performance (Weiss & Cropanzano, Reference Weiss and Cropanzano1996). Previous research (Salas-Vallina, Alegre, & Fernández, Reference Schaufeli and Bakker2017b) has also revealed that OCB is a consequence of HAW. OCB goes beyond traditional measures of job performance and reveals a type of behaviour that refers to positive contributions made by employees that are not included in their job specifications. Organ defined OCB as the ‘individual behaviour that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognised by the formal reward system and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organisation’ (Reference Organ1988: 4). The attitudinal theory states that positive attitudes result in positive behaviours (Abzari, Kabiripour, & Saeidi, Reference Abzari, Kabiripour and Saeidi2015), and the Job Demands-Resources theory posits that resources lead to positive attitudes, which result in pro-social behaviours (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007). OCB was measured using the Lee and Allen (Reference Lee, Park and Baker2002) scale, which has been validated in previous research. Participants answered how often they presently engaged in the behaviour or if they assisted others with their duties.

Results

Table 9 provides empirical evidence that both the original and the SHAW scale do not have significant differences (z<1.96) in their correlations with the outcome variable, which means that they work similarly. We also determined the correlations between the original (using sample 1) and shortened (using sample 2) HAW dimensions and OLC, finding that they correlate similarly. These results are interesting for researchers who aim to work with specific HAW dimensions.

Table 9 Comparison of correlations between the original and shortened happiness at work (HAW) scales and outcome variables

Note. AOC=affective organisational commitment; ENG=engagement, JS=job satisfaction; SHAW=shortened version of HAW.

**p<.01.

Discussion

Step 4 confirms that the OCB outcome variable examined in previous research correlates with SHAW similarly to the original HAW scale, using two different samples. In addition, we found that HAW original scale dimensions correlate with OCB slightly more compared to SHAW dimensions.

DISCUSSION

This paper has developed and validated a short version of the HAW scale, which is a broad and accurate measure of positive attitudes at work (Fisher, Reference Fisher2010). Self-report survey methods need to be improved by shortening existing scales (Kacmar et al., Reference Kacmar, Crawford, Carlson, Ferguson and Whitten2014), and the SHAW scale is a reliable, valid and acceptable measure that answers the call for more accurate and precise self-report measures. SHAW supports previous research on positive attitudes and takes Fisher’s (Reference Fisher2010) conceptualization of HAW, which comprises three dimensions that broadly capture HAW, considering the affective implication and feelings at work, evaluative judgements of job characteristics, such as salary, supervision and career opportunities, and feelings of belonging to the organisation. These three dimensions are respectively captured in the original HAW scale using engagement (a special feeling of energy and motivation related to the capacity of thrilling and feeling passionate at work), job satisfaction (a more reactive concept that captures feelings about working conditions, such as salary, career opportunities or relationship with peers) and affective organisational commitment (feelings of affection and belonging to the organisation). What makes HAW particularly interesting is that not only does it integrate and clarify its three dimensions, but it also presents a higher-order construct, a general attitude measure (Salas-Vallina, Alegre, & Fernández, Reference Salas-Vallina, Alegre and Fernández2017a, Reference Schaufeli and Bakker2017b), which enables compatibility when wanting to link attitudes and behaviours, such as HAW and OCB.

We shortened the original HAW scale by using best practice recommendations for scale reduction (Stanton et al., Reference Stanton, Sinar, Balzer and Smith2002; Kacmar et al., Reference Kacmar, Crawford, Carlson, Ferguson and Whitten2014), using two heterogeneous samples from different occupational sectors, such as physicians, nurses, teachers or banking employees, across Spain and Italy. The results of our research suggest that the nine-item version of the HAW scale adequately captures all aspects of each dimension only with less than one-third of the items and that both versions of HAW have similar psychometric properties. In Step 1, we followed Stanton et al.’s (Reference Stanton, Sinar, Balzer and Smith2002) recommendation of contemplating not only internal item qualities (factor loadings, Cronbach’s αs) but also judgemental qualities. Research expertise can positively influence the quality of items by improving items’ relevance or clarity of expression and avoiding semantic redundancy, negations or absolutes. We choose nine items of the 31 items in the original HAW scale. In Step 2, we verified the factor structure of the SHAW scale using the second sample, by means of confirmatory factor analysis. We ensured that SHAW overcomes the psychometric properties of dimensionality, reliability, content validity, convergent validity and discriminant validity. In Step 3, we checked that there were no significant differences in the correlations between the HAW scale and SHAW dimensions with HAW antecedents. In Step 4, we confirmed that the HAW scale and SHAW work similarly in relation to HAW outcomes. Steps 4 and 5 used the first sample (N=234). These four steps demonstrate that the proposed SHAW performs in the same manner as the original HAW scale. We provide ample evidence that our shortened scale can be used to measure HAW while maintaining the statistical properties of the original scale.

Our research shows that the SHAW scale is a viable measure to implement in the growing field of positive management, in which few comprehensively reliable and valid wide measures exist (Fisher, Reference Fisher2010). SHAW is a quick and accessible tool to assess happiness in the work context. We argue that this new measurement scale presents a high statistical potential to widely capture positive attitudes at work, which opens undeveloped research possibilities. Our environment is increasingly characterised by the progressive dehumanisation of organisations (Kristensen & Johansson, Reference Kristensen and Johansson2008). Sulkowski stated that ‘The industrial era of dehumanization of the workforce has influenced and left management practices being incompatible with the emotional, cognitive and collaborative underpinnings of modern human capital. […] there is a need to humanize [human capital] again’ (Reference Sulkowski2013: 10).

However, there is some criticism of positive psychology. Fineman (Reference Fineman2006) argues that the ‘sunnier side of life’, namely, positive emotions (love, hope and joy), should be linked to negative emotions (fear, anxiety, sadness), as they are two sides of the same coin, and that love and jealousy, or anger and energy can be mixed. Hence, research should not focus solely on the positive, as it represents a narrow view of reality. But the point is that SHAW is not an emotion, it is an attitude. And as Fisher (Reference Fisher2010) stated, emotions (joy, love) precede attitudes (engagement, commitment, satisfaction, happiness). Therefore, the complex and little-known world of emotions is not examined in this research.

Fineman also stated that positiveness is presented as the panacean world, being seductive and uncritical. The SHAW scale does not support this view. SHAW does not force people to smile and feel happy. On the contrary, it is a way to improve their quality of life at work. We do not propose psychotherapeutic workplace programs to improve self-esteem (Armstrong, Reference Atkinson and Hall2004). The aim of SHAW is not to generate positive energy. SHAW aspires to seduce companies to set the stage for better working conditions. In response to this, employees are expected to become more engaged, satisfied and committed at work, which is aligned with recent publications centring on happiness and the common good (Felber, Reference Felber2015).

As Fineman (Reference Fineman2006) and (Doughty, Reference Doughty2004) rightly argued, measures for positivity do not take into account social or economic conditions in the workplace. Moreover, positivity is often understood as an imposed psychological state, which leads to employee conformity to the organisation (Fineman, Reference Fineman2006). Nevertheless, we agree with Fineman that programmes that aim to make workers happy can reinforce subordination, control and inequalities (Alvesson & Willmott, Reference Allen and Meyer1992). This is not the case of the SHAW construct, in which happiness emerges as a consequence of breaking down imbalances in the workforce. For example, a fair salary is included in the job satisfaction dimension of SHAW, which refers to good working conditions. What is more, affective organisational commitment refers to employees’ perception of belonging to the organisation, which is closely related to participation and, by extension, to the level of democratisation of the organisation. Still, we agree with Fineman (Reference Fineman2006) that positivity at work might need to consider cultural diversity, as cultural norms differ between countries, and therefore the SHAW scale may require adaptation to distant cultures.

More than ever before, managers need employees that make a critical difference in innovation, competitiveness and performance. The focus in modern organisations should be on the management of human capital, creating the working conditions that inspire employees to be happy, going the extra mile and persisting in the face of difficulties. HAW is a powerful tool that may help organisations to attract creative, enthusiastic and passionate employees who make companies successful. HAW should become a primary focus of human resources management and its rigorous measurement is primarily a practice imperative.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

To validate the psychometric properties of the SHAW scale, we did not limit the sample to a specific department or organisation. We used data collected from two samples with a wide range of employees throughout Spain and Italy. We followed accepted methods for scale reduction (Stanton et al., Reference Stanton, Sinar, Balzer and Smith2002), accurately examining internal, external and judgemental qualities of the new shortened scale. However, our research design presents some limitations. First, although we analysed different antecedent and outcome variables, they represent only an example of the wide number of variables that could have been included. This limitation also opens future research possibilities for SHAW. Causal effects were not explored due to the process of data collection. We propose that future research tests additional antecedent and outcome variables and validates previous theoretical models, comparing its psychometric properties with those of the SHAW scale. Although our validation of the SHAW scale still requires further exploration, this research demonstrates that HAW can be accurately measured using a shortened scale.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the reviewers for their useful comments.