INTRODUCTION

I … demand the formation of a consolidated Muslim State in the best interests of India and Islam. For India, it means security and peace resulting from an internal balance of power; for Islam, an opportunity to rid itself of the stamp that Arabian Imperialism was forced to give it, to mobilize its law, its education, its culture, and to bring them into closer contact with its own original spirit and with the spirit of modern times (Iqbal, 1930: para. 13d).

Although ethnic privileges remain often unquestioned in the context of work, their understanding contributes to deconstructing many of the oppressions and inequalities in organizations (Nkomo, Reference Neville, Worthington and Spanierman1992; Hunter, Grimes, & Swan, Reference Hunter, Grimes and Swan2009; Sang, Al-Dajani, & Özbilgin, Reference Saïd2013; Torino, Reference Torino2015). Privilege can be defined as an advantage, right or immunity granted or available to a specific person or group of people. The concept of ethnic privilege is mainly researched in Western contexts with a particular focus on whiteness in societies and organizations (e.g., Lund & Carr, Reference Khattab2010; Sang, Al-Dajani, & Özbilgin, Reference Saïd2013). However, despite enormous Muslim population, exceeding 1.6 billion (Pew, Reference Peach2011; Khattab, Reference Khan2012), and rich ethnic and cultural diversity (more than 56 countries are members of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation), there is dearth of research on this topic in the context of Muslim majority countries (MMC) and communities. Religion in general and Islam in particular are largely under-researched themes in organization studies. Yet, religion is not ‘left at home’; it infuses working life (Essers & Benschop, Reference Essers and Benschop2009: 404).

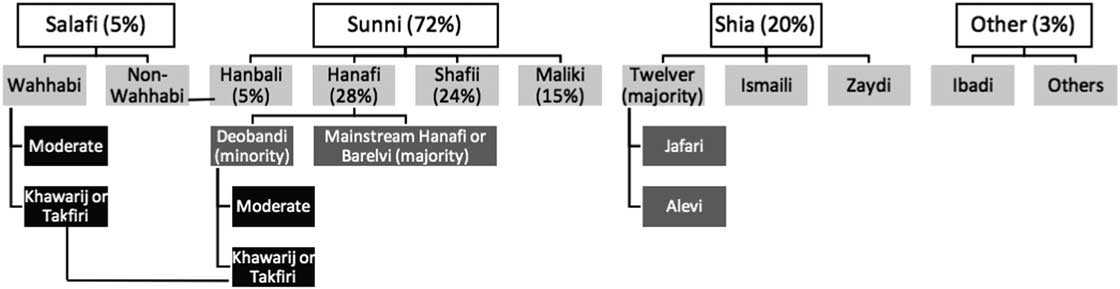

In the world today, three main sects or branches of Islam are more prominent: Sunni, short for Ahlus Sunnah, that is, those who follow the traditions of the Prophet Muhammad and revere his companions; Shia, short for Shia of Ali, that is, those who follow the Prophet Muhammad and his cousin Ali; and Salafi, that is, those who follow the ‘salaf,’ the early Arab Muslim role models including the companions of the Prophet (al-Laalika’ee, Reference al-Laalika’ee1999). Some scholars view Salafis as a sub-sect of Sunnism, however, in their beliefs and traditions, such as opposition to Sufi shrines, rejection of the Mawlid or Milad traditions celebrating the Prophet’s birthday, denunciation of intercession (or tawassul) through Prophet Muhammad and saints, intolerant approach to other Islamic sects and strict views on female seclusion, Salafis are much different from the majority of Sunni Muslims (Wiktorowicz, Reference Williams2006; Duderija, Reference Duderija2007; Rana, Reference Prokop2010). In August 2016, more than 100 senior Sunni scholars including Ahmed el-Tayeb, the grand cleric of Cairo’s al-Azhar University, and other clerics from more than 30 countries met in Grozny and declared that Salafis or Wahhabis were not a part of the Ahlus Sunnah or Sunni (Dehlvi, Reference Dehlvi2016).

Sunni Muslims generally include the followers of the Hanafi, Shafii, Maliki and Hanbali schools of Islamic jurisprudence. Mainstream Sunni Muslims represent 72–77% of the worldwide Muslim population (Hanafis 28%, Shafiis 24%, Malikis 15%, Hanbalis 5%) while Salafis (beside Hanbalis) are no more than 5%. The followers of the Hanbali school are a core part of the Salafi (or Wahhabi) movement in Saudi Arabia. Shia Muslims, including Twelver (Ithna Ashari), Ismaili and Zaydi (see Figure 1), represent 15–20% of the global Muslim population and constitute a majority or significant minority in countries where Islam found its roots in its first few decades, that is, Saudi Arabia (10–20%), Iraq (65%), Iran (95%), Yemen (50%), Bahrain (70%), Kuwait (30%), Syria (20%) and Lebanon (30%) (Bulletin of Affiliation, Reference Boje1998; Pew, Reference Peach2011; Al-Islam, 2017). While the majority of the mainstream Sunni and Shia Muslims follow traditional Sufi practices and allow women and men to visit shrines and participate in religious rituals such as Mawlid and Ashura, the Salafis and Deobandis are opposed to visiting Sufi shrines, celebrating the Prophet’s birthday or seeking God’s help through intercession of the Prophet or saints. While most Salafis do not condone terrorism and violence, a dominant majority of Islamist militants of the Al-Qaeda, Islamic State, Boko Haram, Al-Shabab and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (known as the Khawarij or Takfiris due to their practice of excommunication and violence against all those who do not subscribe to their supremacist agenda) emanates from extremist sections within Salafi and Deobandi communities.

Figure 1 An overview of Islamic sects in the current era

Departing from sweeping generalizations about Islam and gender that are commonplace in the mainstream media and scholarship, this paper pays attention to diversity within Islam and develops an Islamic and postcolonial perspective to understand and examine religio-ethnic privilege and its implications for women’s employment in the national context of a South Asian MMC, Pakistan. The term postcolonial is used here to refer to cultural legacies and influences of Arab colonialism in South Asia. The history of Arab colonization of Pakistan dates back to early 8th century AD when an Arab general Muhammad bin Qasim conquered most parts of Sindh and Punjab regions for the Umayyad Caliphate (Rosser, Reference Roediger2004). The Arab influences on Pakistani society, including history, economy, ideology and culture, continue to date and have been described as Arab imperialism and colonialism and a source of Islamist radicalization (Iqbal, 1930; Nasr, Reference Nasr2000; Mushtaq, Reference Mir and Naquvi2010; Ejaz, Reference Ejaz2011; Yasmeen, Reference Yasmeen2012). The present paper argues that a foreign, Arab-Islamic religio-ethnic stereotype – Arab-Salafi Muslim woman – is becoming increasingly prevalent and privileged in Pakistani society and organization, which may disadvantage nonconforming women (Duderija, Reference Duderija2007; Hoodbhoy, Reference Hoodbhoy2009; Özbilgin, Syed, Ali, & Torunoglu, Reference Nkomo2012; Syed & Van Buren, Reference Syed and Pio2014; Valentine, Reference Valentine2015). It may be noted that while Salafis, in their Wahhabi form (i.e., influenced by the ideology of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, a hardline 18th century cleric), are dominant in Saudi Arabia, they represent a wealthy and increasingly influential minority community in the worldwide Muslim population including Pakistan. Indeed, there are other forms of Islam such as various sub-sects of Sunni and Shia that prevail in MMCs across the world including in the Arab world, the focus of this paper is on Salafi (or Wahhabi) ideology originating from Saudi Arabia. The paper explains the process through which sections of a moderate MMC seem to be turning their back on modernity and historically tolerant Islamic traditions and falling for ultra-orthodox Salafi ideology and conduct. This paper uses the case of workplace – and the issue of female modesty and employment – as the prism to reflect on this phenomenon.

The literature review (next) informs us that an ultra-orthodox ideology, focus on Arab-Islamic values, and a specific emphasis on physical and moral modesty (Duderija, Reference Duderija2007) are key elements of the popular image of ‘good Muslim woman’ promoted by the Arab-Salafi ideology. It may be argued that in organizations and wider societies in the Arab-Salafi-influenced MMCs, those women who conform to the ‘good Muslim woman’ image may be relatively more acceptable and differentially treated than nonconforming Muslim and non-Muslim women (Syed, Ali, & Winstanley, Reference Stepan and Robertson2005).

In his comment on Arab influences on Pakistan, Ejaz (Reference Ejaz2011) notes the increasing influence of Saudi Arabia and other Arab Sheikhdoms of the Gulf on major sections of Pakistani society, such as economy, politics, communication and banking. In other words, there is increasing radicalization of ordinary Sunni Muslims to Salafi or Wahhabi ideology. Ejaz describes the phenomenon as Arab imperialism, and notes that along with the Arab economic domination, Arab-Salafi ideology has been rapidly penetrating Pakistani society, with possible extremist connotations and tendencies. He describes Pakistan as place where ‘primitive’ Arab-Salafi ideology has been competing with ‘modern’ Western imperialist ideology – with particular implications for women. ‘The hijab and sleeveless women are showing up in Pakistan at the same time’ (Ejaz, Reference Ejaz2011: para. 5–6). With the advent of globalization, Pakistani society is experiencing both Arab-Salafi and Western influences, and owing to the enormous sponsorship of Salafi ideology by Saudi Arabia and other petro-dollar Sheikhdoms of the Gulf, the current drift seems to be more towards the Arab-Salafi ideology (Mushtaq, Reference Mir and Naquvi2010; Yasmeen, Reference Yasmeen2012). This in turn creates polarization and tensions in the context of gender.

While there is a growing body of literature on gender in Islamic contexts (Mernissi, Reference Maykut and Morehouse1996; Hassan, Reference Hassan2001; Winter, 2001), there is a general lack of research on the increasing Arab-Salafi influence and its implications for women in MMCs. Through qualitative interviews with Muslim women working in Pakistani organizations, the paper uses an Islamic and postcolonial lens to develop the notion of religio-ethnic privilege and examine its implications for gender equality at work.

This paper contributes to the organization studies literature by introducing and developing a new concept, that is, Muslim ethnic privilege. While the notion of ethnic privilege is often related to the mainstream or white employees but our study suggests that minority groups too (in this instance, Muslim women practicing Arab-Salafi traditions) may have an ethnic privilege.

Also, it is important to note that ethnic (or religio-ethnic privilege) is not necessarily related to numerical majority or minority of the population. In fact, in several MMCs (e.g., Pakistan, Turkey and Egypt), Salafis and their affiliated Islamists constitute a numerical minority, however, they remain a powerful section of society due to various factors, for example an extensive network of Islamist seminaries and groups, generous Saudi financial support, and Muslim political reaction to the US-led wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Indeed, Salafis represent a powerful minority sect in Pakistan and many other MMCs but are increasingly influencing mainstream Sunni Muslims. Ethnicity in this sense is not necessarily confined to minority groups (Kellas, Reference Kauser and Fotaki1998) but can be used to refer to foreign culture, agents and influences.

The paper offers a departure from a monolithic perspective of Islam that is often projected in mainstream media and academic scholarship (barring a few exceptions, such as Pio’s [Reference Phinney2010] study of female entrepreneurs of Islamic Dawoodi Bohra Ismaili community in Sweden, or Mir and Naquvi’s [Reference Miles and Huberman2016] account of American Muslim community’s reaction to the Takfiri extremists). A monolithic perspective is problematic because Muslim beliefs, practices and their interpretations vary tremendously on the basis of denomination, sect, cultural and ethnic practices, gender and religiosity (Syed & Pio, Reference Syed, Ali and Winstanley2016). The study is timely given the increasing Salafi influence in Muslim communities and societies and its potential implications for work and organizations.

The paper is structured as follows. First, it discusses the concepts of ethnic privilege and religio-ethnic privilege and uses Islamic and postcolonial insights to consider the interplay between ethnic privilege and gender. It then provides a brief overview of Muslim religio-ethnic privilege and gender in the context of Pakistan. In the qualitative study section, the paper presents findings of interviews with Muslim female employees and also outlines some implications for future research and practice.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

In this section, an overview of ethnic privilege is offered and the notion of Muslim religio-ethnic privilege is introduced. In particular, implications of a good Muslim woman stereotype for women’s employment in an MMC context are discussed. Given the lack of attention to internal heterogeneity and complexity of Islam in English language sources, both scholarly and media sources are used to illustrate arguments in this paper. In the words of Saïd (Reference Rosser1978), there are not one but many Islams in the world today, a fact referring to internal heterogeneity of Islam which is largely ignored in scholarship on Islam and Muslims including in the field of management and organization studies.

Religio-ethnic privilege

Ethnic privilege can be defined as a way of conceptualizing ethnic inequalities that focuses as much on the advantages that certain ethnic groups accrue from society as on the disadvantages that certain other ethnic groups may experience. Research on ethnic privilege is usually dominated by a focus on advantages and rights available to white persons in the workplace and wider society (Neville, Worthington, & Spanierman, Reference Mushtaq2001; Williams, Reference Winter2004; Kauser & Fotaki, Reference Kamla2015). Ethnic privilege may involve historical and extant processes of racism, ethnocentrism, capitalism, colonialism and imperialism, all of which influence work, organization and management (Grimes, Reference Grimes2001; Roediger, Reference Rizzo, Abdel-Latif and Meyer2005).

For the purposes of this paper, religio-ethnic privilege refers to the privileges gained by those Muslim women/men who conform to an Arab-Salafi role model of good Muslim woman/man, such as preferential treatment in employment and wider society. An Arab-Salafi ideology-influenced woman will often wear black cloaks known as abaya, usually paired with the hijab (headscarf) or niqab (covering all of the face apart from the eyes), or a burqa (covering the body from head to toe, with a mesh for the eyes). By ethnicity, the paper refers to a cluster of nonphysical cultural characteristics, such as one’s national origin, language and religion as well as a sense of people-hood or shared cultural identity (Phinney, 1996; Jones, Reference Iqtadar1997). Previous research (Poulter, Reference Pio1990; Yilmaz, Reference Yilmaz2000; Khattab, Reference Khan2012) suggests that religion and its various traditions and practices are an important component of ethnic identity. This is particularly true in an Islamic context where it is hard to segregate Arab cultural traditions from Islamic traditions, and religion has a visible impact on dress code, festivals, diet, language and other aspect of daily life (Stepan & Robertson, Reference Spivak2004; Rizzo, Abdel-Latif, & Meyer, Reference Rana2007).

The role of religion as a part of ethnic identity is also recognized in non-MMC contexts. For example, in Mandla v. Dowell Lee (in the UK), the House of Lords defined several criteria by which a group of people could be regarded as an ethnic group. These criteria included: a cultural tradition of its own (essential), long shared history (essential) and religion (nonessential) (Poulter, Reference Poulter1997, cited in Yilmaz, Reference Yilmaz2000). Poulter, thus, identifies the role of religious beliefs and value systems as an important element of minority communities: ‘…the most important characteristics of the minority communities today are not so much the (predominantly) brown or black skins of their members but their adherence to certain customs, traditions, religious beliefs and value systems which are greatly at variance from those of the majority white community’ (Poulter, Reference Pio1990: 3).

Arab colonial influences

From a postcolonial perspective, religious and cultural identity in colonized societies represents the dilemmas of developing a national identity after colonial rule, and the ways in which the literature projects the colonized as inferior people, society and culture. Postcolonial scholarship analyzes, explains and responds to the cultural legacies of colonialism and of imperialism, to the human consequences of controlling a country and establishing settlers for the economic and ideological exploitation of the native people and their resources (Spivak, Reference Shepard1988; Weedon, Reference Weedon2000).

While postcolonial scholarship has generally focused on European domination and colonization of parts of Asia, Africa and other continents, this paper deals with Arab imperialism and its use of Islam as a tool of domination on non-Arab countries. According to Shaikh, a polemicist known for critical views on Islam, Islam as a religion brought ‘imperial dignity to the Arabs’ (Reference Shannon1998: 75), subordinating non-Arab converts and their descendants to Arab cultural hegemony, making them permanent allies for the Arab cause. In Shaikh’s rather harsh assessment, non-Arab Muslim are charmed by Arab imperialism (Reference Shannon1998: 7) while non-Arab Muslim countries may be seen as spiritual and cultural satellites of Arabia. In that sense, Islam may be seen as being used as the subtle tool of Arab imperialism. It must, however, be noted that Salafis represent a minority sect not only in MMCs but also in Arab countries. Therefore, term Arab-Salafi in this paper refers to the propagation and influence of Salafi (or Wahhabi) ideology of Saudi Arabia and other Salafi Sheikhdoms and groups.

With regards to Muslim religio-ethnic privilege, it is important to note that Islamic society is not monolithic (Saïd, Reference Rosser1978; Peach, Reference Pabst2006). There are numerous Islamic sects and interpretations, and correspondingly there are numerous Islamic societies in the world today, representing diverse cultures, ethnicities and sects. These diversities are attributable to a variety of interpretations and ethnic practices of Islam in different parts of the world. These interpretations vary across ethnicities and sects, and result in distinct forms of gender relations and privileges in each society.

In the last few decades, Saudi Arabia has been actively promoting and propagating an ultra-orthodox Salafi interpretation of Islam (Gartenstein-Rossa & Vassefia, Reference Gartenstein-Rossa and Vassefia2012). While the Saudi version of Salafi Islam is influenced by the teachings of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703–1792), it has a history of close relationship with other Salafi or similar ultra-puritanical movements in the world, for example, Taliban in Afghanistan (primarily influenced by the Deobandi ideology), Darul Uloom Deoband in India, and Deobandi and Salafi (Ahl-e-Hadith) groups and Jamaat-e-Islami in Pakistan. In the last few decades, Saudi Arabia has promoted itself as a champion of the pan-Salafi movement in the world (in the guise of generic pan-Islamic or pan-Sunni slogans) and has been able to influence other forms of Salafi and mainstream Sunni Islam across Asia, Africa and other continents. Hoodbhoy (Reference Hoodbhoy2009) notes that generous Saudi funding is helping in proliferation of the Arab-Salafi ideology through media, scholars and institutions in Muslim communities across the world including Pakistan. As a result, there is a growth in radical Islamist movements and the spread of ultra-puritanical ideologies, which are known for certain features for example, condemnation of many common Muslim practices as polytheism (shirk) and religious innovation (bid’ah), emphasis on the salaf (the earliest Muslims) as role models of Islamic practice, literalist approach to Islamic theology, restrictions on women and religious minorities, xenophobia, etc. The resurgence of Islamists in Turkey, Egypt, Libya, Pakistan, Afghanistan and other MMCs may be seen, at least partially, as an outcome of the global Salafi or allied Islamist movements (Wiktorowicz, Reference Wiktorowicz2001, Reference Williams2006; Shepard, Reference Shaikh2012).

The global pan-Salafi movement represents a transnational effort for religious purification, connecting members of an imagined community through an ultra-orthodox approach to Islam (Dorsey, Reference Dorsey2012; Gartenstein-Rossa & Vassefia, Reference Gartenstein-Rossa and Vassefia2012). According to Wiktorowicz (Reference Wiktorowicz2001), Salafis constitute one of the fastest-growing Islamic movements and enjoy a global reach in virtually all countries. Wiktorowicz’s interviews with Jordanian and Egyptian non-Salafis (mainstream Sunnis such as those following Imam Abu Hanifa and Imam Shafi’i) suggest that even non-Salafi Islamists are not immune from the scope of the Salafi movement and its effects on Islamic practices. The Salafi thought has affected mainstream Sunni Muslims and Islamists in various parts of the world. In India, Barelvi Sunnis (i.e., the Hanafi majority community that follows the South Asian tradition of Sufi Islam) or Sufis are complaining that gradually their mosques and adherents are being taken over by Salafis (The Telegraph, Reference Tayeb2009). Pakistani scholar Hoodbhoy thus points towards the growing impact of the Saudi Salafi ideology in Pakistan. ‘For three decades, deep tectonic forces have been silently tearing Pakistan away from the Indian subcontinent and driving it towards the Arabian Peninsula. This continental drift is not physical but cultural, driven by a belief that Pakistan must exchange its South Asian identity for an Arab-Muslim one. Now a stern, unyielding version of Islam (Wahhabism) is replacing the kinder, gentler Islam of the Sufis and saints who had walked on this land for hundreds of years’ (Reference Hoodbhoy2009: para. 6).

Similar views are expressed by Pabst (Reference Özbilgin, Syed, Ali and Torunoglu2009) and Nasr (Reference Nasr2000) who suggest that the tolerant Sufi-minded Barelvi Sunni form of indigenous Islam in Pakistan has been supplanted by the hardline Salafi or Wahhabi ideology. Pabst (Reference Özbilgin, Syed, Ali and Torunoglu2009) notes that the madrasa-inspired, Saudi-financed Salafi or Wahhabi Islam is hurting the indigenous Islam of the Subcontinent. The term madrasa is used for religious schools established for Islamic instruction.

Wieland (Reference Wiktorowicz2006) has highlighted the attempts to enhance the influence of Salafi ultra-orthodox ideology in Arab countries. Saudi Salafis are known for making inroads in societies as diverse as Europe, North America, Indian subcontinent and Africa. They are also reportedly involved in financing Islamic schools or madrasas and there is an increasing number of mosques preaching Salafi ideology and values (Wieland, Reference Wiktorowicz2006; Kamla, Reference Jones2012). Several Arabs and non-Arabs perceive such developments as a change from their form of progressive Islam to a less tolerant version of religion (Wieland, Reference Wiktorowicz2006). A large number of modern as well as religious madrasa schools in MMCs (e.g., Pakistan, Turkey, Bangladesh) regularly receive financial aid from Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries, both government and NGOs (Prokop, Reference Poulter2003; Candland, Reference Candland2005). In turn, their curricula and teachers reflect and disseminate the Arab-Salafi ideology.

Female modesty and the privilege

The Arab-Salafi influences are particularly constraining for women who are expected and at times forced to observe the strict form of veil and gender segregation (Shannon, Reference Sang, Al-Dajani and Özbilgin2014). While at least some form of veil, for example, chadar (a traditional loose garment consisting of a long cloth or veil that envelops the body) or dupatta (a shawl-like thin scarf that is a usual part of women’s clothing in South Asia), is also evident in mainstream Sunni, Sufi, Shia and other sects and practices of Islam, the Arab-Salafi version of the hijab, a veil that covers the head and chest, is a relatively new phenomenon in Pakistan. Historically, Barelvi Sunni (Hanafi) or Sufi women have relatively freely participated in visits to shrines and also in agricultural-economic activities. From an ultra-orthodox Salafi view, visits to shrines are tantamount to polytheism and the participation of women in public activities is discouraged or strictly regulated to enforce gender segregation and modesty (Figueira, Reference Figueira2011; Shepard, Reference Shaikh2012).

Because of its ultra-orthodox and gender discriminatory leanings, the Arab-Salafi ideology promotes certain stereotypes which affect women’s employment and equal opportunity at work. In this context, the ethnic privilege may be described as the unearned advantage of being a ‘good Muslim woman’ in a religio-culturally stratified society, reflecting an institutional and socio-cultural power that is largely unacknowledged by stakeholders such as governments, employers, managers and employees. ‘Good Muslim women’ are expected to physically as well as morally conform to certain stereotypes. For example, the working women who break the norm of gender segregation may be undervalued and frowned upon (Syed, Ali, & Winstanley, Reference Stepan and Robertson2005). This attitude was reflected during a study of carpet-weaving and sardine-canning units in Morocco when most of the exclusively male managerial staff expressed the idea that ‘only loose women go to work outside of their homes’ (Mernissi, Reference Maykut and Morehouse1996: 66). While not all of the constraints put on women may be attributed to an Arab-Salafi interpretation, Salafi Islam is more restrictive for women than other versions or interpretation of Islam. This is true not only in Saudi Arabia (where women are not allowed to drive or travel alone and only recently the Saudi government announced that women will be allowed to drive with effect from June 2018) and other countries where Salafis ideology is a favored interpretation of Islam but also in certain other countries where there is significant influence of Islamists and a gradual co-option of Islamist movements with the Salafi Islam is taking place.

While in today’s Muslim world, due to political and socio-economic pressures, a significant number of women may be seen in the ‘public space,’ a ‘nonconforming to the tradition’ Muslim woman may be seen by puritanical Muslims as a symbol not of ‘modernization’ but of ‘Westernization’ (Hassan, Reference Hassan2001). From an Islamist perspective, the hijab may constitute part of the ideological and cultural resistance to Western cultural imperialism and represents a symbol of identity to many Muslims (Kamla, Reference Jones2012), particularly in Arab countries. There appears to be a multilayered postcolonial dynamic where Salafi and other Islamists react to trends in Westernization/globalization by attempting to impose their vision on the societies they regard as veering from tradition as they define it. Gender becomes a focus as gendered institutions (the workplace, the public sphere, the home) and gender roles are clearly experiencing change. A study on Muslim Arab women at workplace suggests that women’s dress is overemphasized and influences women’s opportunities at work (Kamla, Reference Jones2012).

In their self-acquired status of guardians of Muslim traditionalism, Salafi and other Islamist groups and parties may feel threatened by the phenomenon of women working in the formal organizations (Iqtadar, Reference Iqbal2009). They see Muslim women at work and other public spaces as symbols of ‘Westernization,’ which is linked with the continuing onslaught on what they perceive to be the integrity of the Islamic way of life.

‘Good Muslim woman’ at work: An Arab-Salafi perspective

It is possible to identify certain key elements of a good Muslim woman stereotype using an Islamic and postcolonial lens (Doumato, Reference Doumato1992; Mernissi, Reference Maykut and Morehouse1996; Syed, Ali, & Winstanley, Reference Stepan and Robertson2005; Mushtaq, Reference Mir and Naquvi2010): Salafi ideology, focus on Arab-Islamic values, physical modesty (e.g., hijab, dress code and gender segregation), moral modesty (e.g., restraint in speech and social interaction; religious rituals) and individual identity (e.g., family status, marriage, children, sect). Vidyasagar and Rea (Reference Vidyasagar and Rea2004) report how Salafi sharia and legal system sanctions male superiority and gender segregation in all areas of life, and adversely effects women’s choice of career and equal opportunities at work. While some of these elements may also be visible in other sect of Islam, it is argued that due to their puritanical and ethnocentric nature, Arab-Salafi values and stereotypes are much more powerful, gender discriminatory and restricting for women.

The literature suggests that in the Salafi-influenced organizations and communities, women who do not conform to the elements of ‘good Muslim woman’ stereotype may face constraints and problems. For example, women who try to break the Saudi law which disallows them from driving were arrested and threatened with dire consequences (Al Nafjan, Reference Al Nafjan2012). There are strict restrictions on women’s mobility outside their homes without a male relative (mahram). Similarly in Pakistan, it is not uncommon to see that women who work in formal organizations are underpaid and undervalued, and their participation in public life is resented by Islamist circles (Ali & Knox, Reference Ali and Knox2008; Mushtaq, Reference Mir and Naquvi2010). In February 2007, Zil-e-Huma Usman, a female Pakistani minister and women rights activist was shot dead by an Islamic extremist who believed that she was dressed inappropriately and that women should not be seen in public space (Bhat & Hussain, Reference Bhat and Hussain2007). This and other similar examples of Islamist extremists’ violence against women are not consistent with the relatively reconciliatory Sunni Sufi traditions of the Subcontinent, and may be traced back to Salafi ideology in Saudi Arabia.

CONTEXT: GENDER, RELIGION AND ETHNIC PRIVILEGE IN PAKISTAN

The paper discusses gender, religion and ethnic privilege in Pakistan’s national context of Islam. According to the 1973 national constitution, Pakistan is an Islamic republic; no law can be enacted or enforced in the country contravening the Quran and the Sunnah (traditions of the Prophet Muhammad). Islamic laws in Pakistan have generally served to reinforce patriarchal ideas about women’s status and role in society (Hussain, Barki, Ahmed, Hassan, & Coleman, Reference Hussain, Barki, Ahmed, Hassan and Coleman2004). According to a survey, 67% of Pakistanis believe that government should take steps for further Islamization of the society (Gallup Survey, 2011).

In terms of religious composition, Muslims constitute 97% of the total population (180 millions) in Pakistan. The Muslim population is further divided into Sunni (75%) and Shia (25%) sects. Salafis (locally known as the Ahl-e-Hadith) constitute a tiny fraction (est. 10%) of Pakistan’s Sunni population, however, owing to generous Saudi funding and an active network of seminaries, organizations and charities, they remain quite influential. Majority of Sunni Muslims in Pakistan belong to Barelvi ideology, which is a South Asian version of Sufism. Within Sunni Muslims, Deobandi sub-sect is considered to be closer to Wahhabi or Salafi ideology and has close links with Saudi Arabia.

In terms of gender equality and employment, Pakistan’s performance has been quite dismal. For example, according to the World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap Report (World Economic Forum, Reference Wieland2015), Pakistan is ranked 144 among 145 countries, showing very large gender gaps in wages, participation in economy and highly skilled employment. The country was deemed most unequal in its employment of men and women for labor force and the relative incomes earned by the two groups.

Gender roles in Pakistan reflect the weight of culture and tradition while Islam remains an important and influential overlay. In the early 1980s, President General Zia-ul-Haq (then military dictator, 1977–1988), heavily influenced by Saudi Arabia and its Arab-Salafi version of Islam, Islamized the country’s constitution and introduced new laws and regulations. For example, government employees, women in particular, had to give up their Western-style clothing and adhere to strict Islamic dress. Education in state schools was segregated, and girls were required to wear a scarf or dupatta. The economy was to be run on Islamic lines, including reinstitution of an old Islamic wealth tax, zakat and Islamic banking practices (Tayeb, Reference Syed and Van Buren1997). Many of General Zia’s Islamic laws are still in force in the country. During his period, Islamists were able to affect a number of laws and amendments in the national constitution, for example the inclusion of Islamist Objectives Resolution into country’s constitution, promulgation of puritanical Sharia laws against women.

Due to Pakistan’s very foundations based on Islamic identity and its gradual Islamization of laws and institutions under the increasing Saudi influence, Pakistanis are known for visible adherence to Islamic practices, especially when it comes to female modesty. For example, during the 1980s, female newscasters and actors on Pakistan Television (PTV) were forced to wear a dupatta in their media appearances; a few who did not comply with this official policy were fired from their jobs or forced to resign (Dawn, 2013). The aftereffects of such policies are still felt in Pakistan today where females who conform to Islamic stereotypes, such as modest Islamic dress, may be valued and respected. In April 2014, a female TV actor faced the charges of blasphemy when a Sufi devotional song, qawwali, was played as a background song on her wedding, shown on a private TV channel (The Indian Express, 2014). While the role of Pakistan’s very creation on Muslim communal basis may not be ignored, the growing spread of Salafi ideology (Mushtaq, Reference Mir and Naquvi2010; Yasmeen, Reference Yasmeen2012) and Pakistan’s economic dependence on Saudi Arabia have further enabled the Salafization of Pakistani society.

Islamists in Pakistan – as well as in other countries, for example Saudi Arabia, Taliban’s Afghanistan – have explicitly and implicitly prescribed, propagated and tried to implement a puritanical stereotype of a good Muslim woman which is, in the main, based on Salafi views on Islam and is in line with an Arab-Salafi woman stereotype. This then may lead to differential treatment of those women – Muslim as well as non-Muslim – who do not conform to such stereotype. In Pakistan, good Muslim women are considered to cover their head with dupatta or chadar. At workplaces, women wearing a dupatta, chadar or hijab are considered more modest as compared with those who do not cover their head (Syed, Ali, & Winstanley, Reference Stepan and Robertson2005). However, hijab, an Arab-Islamic version of veil instead of the South Asian tradition of dupatta, is a relatively new phenomenon in Pakistani society and workplaces. In Professor Hoodbhoy’s words:

The Saudi-isation of a once-vibrant Pakistani culture continues at a relentless pace. The drive to segregate is now also being found among educated women. …Two decades back, the fully veiled student was a rarity on Pakistani university and college campuses. The abaya [a loose over-garment, essentially a robe-like dress which covers the whole body], was an unknown word in Urdu. Today, some shops across the country specialize in abayas. At colleges and universities across Pakistan, the female student is seeking the anonymity of the burqa. And in some parts of the country she seems to outnumber her sisters who still “dare” to show their faces. I have observed the veil profoundly affect habits and attitudes. Many of my veiled female students have largely become silent note-takers, are increasingly timid and seem less inclined to ask questions or take part in discussions. They lack the confidence of a young university student (Reference Hoodbhoy2009: para. 23).

The phenomenon may also be attributed to Arab-Salafi influence, such as through the growing power of Islamist parties and preachers, who are influenced by the Saudi Salafi movement, despite some occasional political differences. Next, the paper explains the research design and presents results of the qualitative study.

METHODOLOGY

This study is part of a larger research project which focused on equality-related issues facing women in Pakistani organizations. However, the paper’s focus is on the following question: How does a ‘good Muslim woman image’ or expectation affect women’s employment in formal organizations in Pakistan?

A qualitative method of inquiry was adopted to explore the stereotypes and privileges of Muslim women in Pakistani organizations. The data is based on 23 interviews with women working in formal organizations in Lahore, Pakistan. Participants were recruited using the authors’ personal networks, also using the snowball method. This sampling method was deemed appropriate because of the personal nature of the questions and also in view of the access issues. Criterion sampling ensured that the participants fitted the following criteria: Muslim women, employment in formal organizations, based in Lahore, even representation of married and single females and those with and without hijab. Table 1 offers demographic overview of the study’s participants. These women were allowed to freely narrate their stories around the questions asked and were encouraged to refer to religious symbols and norms (such as prayer, hijab, Islamic terms) to illustrate their experiences and insights (Boje, 2014). The participants’ education level varied between 12th Grade (Intermediate) and Masters. Each interview lasted, on average, between 30 and 60 min. The interviewees varied in terms of their appearance and religiosity, for example, wearing hijab or lack of it. The occupations or organizations of the interviewees were not considered in this study. Also, the study did not focus on ethnic divisions within Pakistan, for example, Punjabi, Sindhi, Pashtun, and instead examined the implications of religio-ethnic stereotypes for female employees.

Table 1 Demographic profile of participants

Note.

H=hijabi; M=married; N=no; NH=non-hijabi; UM=unmarried; Y=yes.

A semi-structured interview protocol was used to explore ethnic privileges of ‘good Muslim women’ at the workplace. The questions sought to encourage participants to share their individual experiences, perceptions and reflections related to religio-ethnic privilege or lack thereof. The interview questions were refined, in light of a face validity test based on preliminary interviews with two Muslim female academics. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim – except in a few cases where the interviewees preferred not to use a recorder and consequently notes were taken on both the content and context of the interview. The data collection continued until theoretical saturation, that is, until no new themes were uncovered (Guba, Reference Guba1978; Maykut & Morehouse, Reference Malik1994). As a result, a total number of 23 interviews were carried out.

To ensure candidness of the stories, all of the interviews were conducted by the second author, a Western-educated Pakistani Muslim female who wears a dupatta. The dupatta (a part of traditional Pakistani dress) and Western education were considered dual advantage in developing rapport and having candid conversations with the hijab-wearing and non-hijab wearing participants. Interviews were conducted in both Urdu (Pakistan’s national language) and English and the former were then translated back to English. To become more familiar with the data, the transcripts were thoroughly read and reviewed multiple times by both authors and notations were made to record relevant themes and issues. Following the aforementioned procedures (Guba, Reference Guba1978; Miles & Huberman, Reference Mernissi1994), key themes were elucidated which are presented in the next section.

FINDINGS

The following themes related to the good Muslim woman stereotype and their respective implications were evident in the stories collected in this study: physical modesty, moral modesty, individual identity and family status and other experiences. It may be noted that the boundaries between these themes are more overlapping and blurry than neatly defined and distinct. The participants are coded as follows: hijabi (H), non-hijabi (NH), married (M), unmarried (UM). We use a number in these codes to differentiate the interviewees.

Physical modesty

While not all participants agreed with the notion of gender segregation – a few did indicate the importance of refraining from freely mixing with male colleagues. Many of them (17) agreed that women who wear hijab or dupatta are more respected among their colleagues as compared with other females who do not cover their head. Hijab, appeared in this study, as an important symbol of physical modesty. A hijabi participant thus explained her perceived advantage at the workplace because of her hijab. ‘I definitely am at an advantage because of wearing hijab. Males, no matter how much they are attracted to modern girls, tend to respect the girl with a hijab. Along with some exceptions, the majority still respects woman with hijab. Standing up in respect, offering their own seat if none is available, early processing of documents or queries, are some examples’ (H-M-1).

Those wearing hijab did not treat it as an imposition on them by males or religion, and in fact expressed pride in observing hijab as a part of their Islamic identity. ‘Personally, I feel that for me, my hijab is my identity as a Muslim, and I am so proud of it. I am more careful in and around people as I am not representing myself rather I am a symbol of Muslim women’ (H-UM-2).

A non-hijabi woman, manager in a communication firm, thus expresses her perspective of ‘good Muslim woman,’ and also relates it to female modesty. ‘A good Muslim girl is intelligent, capable, loving, and modest. She does not feel the need to behave badly to anyone. She does not attempt to seek happiness in shallow pursuits such as nightclubs and fashion. She has a deep love of God and prays five times a day. Her hijab which keeps her beauty hidden from strangers is so that her beauty is reserved just for her husband and her family. A good Muslim woman should cover herself up and minimize temptation as much as possible’ (NH-M-4).

It is worth noting that while the participant herself does not wear hijab, she believes that ‘a good Muslim woman should cover herself up and minimize temptation as much as possible.’ One possible explanation of this dichotomy is the wider acceptability and influence of a specific notion of ‘a good Muslim woman’ promoted by Islamic circles. Thus, an ordinary Muslim woman while satisfied with her daily routines and choices within and outside the workplace (such as wearing or not wearing hijab) may judge her own choices harshly using an Islamic yardstick.

There was also a perception that hijab contributes to gender segregation, which is an important element of physical modesty within Arab-Salafi values. For example, a hijabi woman explains how her hijab contributes to her segregation from male colleagues. ‘A woman who wears a hijab is usually isolated in work environment as so called “modern women” are more popular amongst their male colleagues’ (H-M-6). While the dual impact of hijab – that is, gender segregation at the cost of interaction with male colleagues – mentioned in this extract cannot be ignored, it also serves as a useful tool to avoid certain people (discussed in next section).

Moral modesty

The interviewees also identified the moral aspects of modesty, for example, restraint in behavior and attitude, speech and social interaction, as important features of a good Muslim woman. A non-hijabi participant explains how a Muslim woman is expected to be modest in behavior and attitude. ‘Saying prayer five times a day keeps us clean, away from vulgarity and using foul language since a Muslim has to abstain from all these in order to remain in wazoo (ablution). A Muslim woman would be polite, decent and abstain from foul language. She would be hardworking since Islam focuses on halal ways of earnings’ (NH-M-5).

Next, a hijabi woman explains how hijab as an Islamic identity also helps her in avoiding people who she is not comfortable with. ‘It [hijab] helps in avoiding people whom I am not comfortable with. It serves as my identity’ (H-UM-4). This observation points towards the influence of the notion of hijab as a marker of Islamic identity and while the practice and the related perceptions may be empowering, those may also serve to isolate the hijab-observing woman from those who she may not be ‘comfortable with.’

Another participant explains how hijab is an official requirement in her workplace: ‘He [the director] is a Tablighi [a Deobandi missionary], therefore, I face no issues at all due to my hijab. In fact, all female employees in our organization wear hijab or dupatta. This is an official policy. During lunch break, all girls offer prayer in a separate room’ (H-M-3).

Another participant, a non-hijabi woman, claims that a good Muslim woman remains aware of her moral limits and may feel more secure in her hijab. ‘A good Muslim woman knows her limits wherever she goes whatever she does, who knows to maintain her dignity as a Muslim woman either she wears hijab or not. I do not wear so I cannot comment much but I am sure there would be lots of advantages as well. I guess a woman feels more secure in hijab that she can escape herself from evil eyes’ (NH-UM-5). ‘Evil eyes’ in this extract may be interpreted as harassment and continuous gazing by males within and outside the workplace.

Individual identity and family status

There was a general perception amongst the participants that fresh graduates, unmarried girls in particular, are not considered loyal, reliable employees by organizations. It was suggested that many employers believe that girls leave their job as soon as they plan to get married. This may very well be the case for some women whose husbands may not wish them to continue working in formal organizations. This practice and mindset may, at least partially, reflect the Arab-Salafi stereotype which imposes restrictions on women’s mobility and participation in the public space. In the words of a participant: ‘Most of the girls do not stick around for longer period to get promoted. Most of the girls join after they graduate and then we have this problem of getting married and most of the time they have to leave the job. So, they are not considered for that [managerial] level position….so, all they need is to communicate better with their managers that we are not going to leave after four or eight months we are here for good four, five years we want to make a career’ (NH-UM-6).

It may be noted that the spatial restrictions indicated in the above account may also have a social aspect as these place women within patriarchal hierarchies that are fluid across space and time. Some participants also suggested that employers might not be willing to offer flexible work arrangements to accommodate women’s family-related roles. This in turn discourages female employment in organizations. ‘Sometimes there are timings issues. They are not able to coordinate office timings with family time especially women who are married. Females prefer to apply for jobs which do not interfere with their family life’ (NH-UM-4).

In the words of another participant: ‘I think the biggest problem for a married female employee is that she is doing two tasks. If husband and wife are working and when they come back from work at the same time, man will lie down to take rest and woman will leave the bag on the table and she will straight away go to kitchen’ (NH-M-5).

The above extracts also reflect the Islamist stereotype which holds women as responsible for domestic chores. However, at least one participant, a non-hijabi woman, reported that she had experienced no differences in treatment at work before and after marriage. Her experiences suggest that organizational culture can serve as an important mediator in addressing issues of intersectionality and ethnic privilege at work. However, she also refers to the case of a personal friend, a medical graduate, who decided to leave the job after marriage due to Islamic reasons. ‘In my experience, I didn’t encounter any harassment as a single woman or later as a married woman. It depends on the company culture, professionalism and attitudes of colleagues. However, I know one of my personal friends, a doctor at a government hospital, who left her job after marriage because of Islamic reasons’ (NH-M-6).

Other experiences

Not all responses in the present study suggest that hijab and other components of the ‘good Muslim woman’ stereotype result in religio-ethnic privilege. For example, there was a view that in some situations, non-hijabi or modern women could be relatively more advantaged, which indicates the polarized nature of Pakistani society and workplaces. ‘Sometimes I do feel that it [hijab] does matter and equal opportunity will not be given to me as compared to a girl who is dressed in modern fitted clothes and she has done her hair and put on make-up’ (H-UM-4).

Another hijabi woman opined how her Islamic practices were in fact putting her at a disadvantage. ‘People consider you conservative and old fashioned, which in return might cost you a promotion or pay raise. Yes, sometimes I am disadvantaged because of wearing hijab.…They preferred modern girls to accompany them’ (H-M-4). The previous extract also points towards the male chauvinist currents in Pakistani society (Malik, Reference Lund and Carr2011), where some male managers may show more interest in non-hijabi or modern women. The extract may also be interpreted as apprehension and distrust that some hijabi women may have in their perceptions of non-hijabi women.

DISCUSSION

The study has offered an Islamic and postcolonial perspective on ethnic privilege which takes a different form and trajectory than what is usually theorized and observed in mainstream Western contexts. It has shown that female employees in Pakistan and possibly other MMCs are subject to a good Muslim woman stereotype, outlining specific physical and moral codes of modesty, which may result in differential treatment between conforming and nonconforming women. In a society or community increasingly influenced by puritanical Salafi ideology, women observing abaya, niqab or hijab may not only escape insults or aggression at the hands of Salafi vigilantes but may actually experience preferential treatment in their employment and career. The latter is particularly likely in religious-oriented organizations or those led by religious minded people. The study suggests that an ultra-orthodox Arab-Salafi mentality is gaining ground in Pakistan and this could lead to women who conform being treated differently, possibly more favorably, than women who don’t conform. This finding is consistent with Zanoni and Janssens’s (Reference Zanoni and Janssens2007) study, which shows how dominant discourses – which conceptually are akin to stereotypes – can act to marginalize and disadvantage those groups who do not meet the norms constructed through them. The interviews show that hijabi women feel more respected or more comfortable, and in some cases, may also receive preferential treatment due to their Islamic modest appearance. However, given the polarization of Pakistani society, the religio-ethnic privileges illustrated in the study are subtle and refined instead of visible discrimination.

The study points towards the influence of an ultra-orthodox Islamist ideology which is inspiring Arab-Salafi-influenced practices among Pakistani women. This finding is consistent with a common concern expressed in media reports (Hanif, Reference Hanif2012; Khan, Reference Kellas2012). For example, some women rights activists fear Talibanization of Pakistan as they witness the proliferation of women in hijab and even the Saudi-style niqab on the streets of Karachi (Ali, Reference Ali2003). This shows an increasing Arab-Salafi influence on Pakistani society, which may create issues for nonconforming women.

Interestingly but not surprisingly, given the subtle nature of the Salafi transformation, none of the interviewees in the present study mentioned Saudi Arabia, and only a few referred to the Aslaf (plural of Salaf, an Urdu version of ‘the pious predecessors’). Based on their own views on and practices of Islam and the preachers they referred to in their conversations, it was obvious that some of them were influenced, probably subconsciously, by such ideologies. While some of these positions and attitudes can also be attributed to the missionary work of Jamaat-e-Islami and other indigenous Pakistani Islamist groups, the distinctions between pan-Salafi movement and indigenous Islamists are becoming increasingly blurry in today’s Pakistan due to a host of reasons. For example, it is hard to differentiate the Jamaat-e-Islami’s founder Maududi’s views on gender segregation from a Salafi interpretation of Islam. The Jamaat-e-Islami is a powerful pressure group in Pakistani society, media and academic institutions. While they have a limited vote bank in Pakistani society, they have one of the most organized, well-funded organizational network in all areas of Pakistan, close contacts with Saudi Arabia, and an ideology that promotes a good woman stereotype, which then enables the import and normalizing of the Arab-Salafi values. In the last few decades, Al-Huda and Jamaat-ud-Dawa, two Salafi groups in Pakistan have been gradually expanding their network of Islamist teachings with a specific focus on Muslim women. Moreover, the Deobandi minority sub-sect, which is closer to Salafi ideology than mainstream Sunni Sufi or Barelvi Hanafi Muslims, has the highest number of madrasas and religio-political organizations in Pakistan.

The present study also identifies at least some adverse implications for ‘good Muslim women’, which points towards the polarized nature of Pakistani society. However, some female participants who did not wear hijab agreed that the hijab-wearing females are generally more respected within and outside the workplace. In general, the study suggests that if Salafi ideology continues to get hold in Pakistan, women who conform to the Arab-Salafi values are likely to be more privileged, particularly in those workplaces where owners or managers are influenced by those values.

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

The paper makes a significant contribution to understanding gender constraints and stereotypes facing Muslim women in Pakistan on the basis of religion and ethnicity. It has added to the extant literature on ethnic privilege by using an Islamic and postcolonial lens to theorize its important variation and nuances in an Islamic context. It has suggested how Arab-Salafi ideology is pervasive in the world of Islam along religious, cultural and ethnic lines, which then contributes to what has been described as religio-ethnic privilege in this paper.

Employers and managers in Pakistani organizations may pay special attention to protect female employees from adverse effects of religio-ethnic stereotypes. For example, awareness sessions and focus groups may be conducted to educate male as well as female employees about the implications of good Muslim woman stereotypes, particularly those which are foreign to Pakistani culture.

Policy makers and leaders in public and private sector organizations may carefully review workplace routines and policies to ensure that no woman or group of women is disadvantaged due to her practice of lack of practice of a specific view or interpretation of religion. Given the increasing spread and influence of the Arab-Salafi ideology across the world, the findings and implications of this study may be particularly relevant to those countries where Muslims constitute the majority or are a significant part of the population. Scholars may investigate this issue in Muslim minority communities in the West and elsewhere to develop a nuanced understanding of broader social inequalities, that is, how is this issue shaping out in terms of global maps and religious affiliation, and is there are clearer trend beyond MMCs?

This focus will also help in highlighting that gender is not a unitary category and that it is important to consider internal heterogeneity of women to identify and assist underprivileged and disadvantaged women. Moreover, scholars may wish to examine in depth if privileges of being a ‘good Muslim woman’ are confined to ‘respect,’ or do they also include more power, influence, promotion opportunities.

At the government policy level, there is a need to reconsider the increasing influence and spread of the Salafi ideology and its implications for diversity and social integration. It is, however, a fact that Saudi government officials and clerics frequently express their support for the Salafi ideology. For example, in December 2010, at a conference titled, ‘Salafism: Legal Path, National Demand,’ the Saudi Crown Prince Nayef bin Abdulaziz thus outlined the Saudi government’s commitment to Salafism: ‘True Salafism is the path whose rules derive from the book of God and the path of the Prophet…This blessed state [Saudi Arabia] has been established along correct Salafi lines since its inception by Imam Mohammed bin Saud and his pact with Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. Saudi Arabia will continue on the upright Salafi path and not flinch from it or back down’ (cited in Dorsey, Reference Dorsey2012: para.11). Implicit in the above confession is the special importance and privilege of the Salafi ideology as taught by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab and the Saudi Arabian identity. Such ethnocentric approach may not be consistent with Islam’s diversity and cross-cultural adaptability.

Moreover, policy makers may closely monitor the labor market statistics in order to identify disparities between various groups of Muslim women, taking into account their intersectionality along dimensions of ethnicity and sect. In particular, gender statistics in areas and industries visibly inundated by the Salafi ideology may be monitored, and adequate interventions may be considered. They may also pay attention to regulate mass media as well as academic curricula and religious seminaries to promote gender egalitarian interpretations of Islam. Employers and business managers may wish to pay specific attention to how puritanical interpretations and practices of Islam are affecting women’s employment and equality at work, and how macro-level stereotypes could be addressed via appropriate organizational interventions, for example, diversity training, redress procedures.

Scholars may wish to conduct similar studies on religio-ethnic ethnic privilege and Islamic stereotypes facing Muslim women at work in other MMCs as well as Muslim diaspora in the West to take into account their heterogeneities and evaluate and refine the contentions offered in this paper. Scholars may investigate the specific effects of teachings of Salafi and other Islamist preachers in the West and the implications of such teachings on employment trends and attitudes of Muslim women. Another direction for future research is to take into account the heterogeneity of Salafi ideologies, how such ideologies differ across countries, and their possible implications for gender equality and employment.

The evidence that hijab can be a double-edged sword is a novel theme highlighted in the present study. It suggests that hijab does not always accrue privilege but may also be a source of disadvantage due to the segregation it generates. For example, there is also an issue of social and spatial barriers that are generated by the hijab. This may be a fruitful avenue for future research.

Indeed, the Arab-Salafi stereotype is not the only type of religio-ethnic privilege in the world of Islam. The Taliban’s Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, representing Deobandi sub-sect albeit influenced by Arab-Salafi ideology, required women to cover their entire body including head and face. In the Shia-theocrats dominated Iran, Muslim women are forced to cover their hair and remain subject to laws made by dominant male clerics. In contrast, hijab at public sector organizations is banned in Turkey, although in December 2010, the Turkish government ended the headscarf ban in universities (Head, Reference Head2010). In the United Kingdom, it was reported that female teachers at a state funded Muslim school in the United Kingdom were asked to cover their heads with Islamic scarves during school hours even if they were not Muslim (Dixon, Reference Dixon2013). Therefore, the implications of the present study are far-reaching and numerous. Future scholars may wish to empirically examine various types of religio-ethnic privilege in diverse national, religious and industry contexts, and document their implications in organizations and wider society.

In terms of limitations, the present study is constrained by a small sample size and also the fact that women in this study worked in an urban-setting in Lahore. Future scholars may conduct qualitative and quantitative inquiries on this topic with larger and more diverse samples of Muslims women in order to evaluate and refine the insights offered in this paper.

CONCLUSION

The paper has used an Islamic and postcolonial lens to show that an Arab-Salafi stereotype is used by Islamists to promote a popular image of ‘good Muslim woman,’ which may in turn contribute to religio-ethnic privilege available to the image conforming women. Particularly in the Salafi ideology-influenced societies and organizations, women who conform to Arab-Salafi stereotype may have privileges which may not be available to the nonconforming women. Future scholars may explore in detail the specific codes of religio-ethnic privilege, which are reproduced in contemporary organizations in MMCs, particularly in the Sharia-driven organizations, and the extent and ways in which such codes configure employment relations and gender relations.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Charmine Hartel and three anonymous reviewers for providing most helpful comments on our paper.