INTRODUCTION

Goal-setting is an immensely popular concept in work planning and assessment, and useful as a fundamental component of organisational management in general. Even though it is a common practice of many organisations in virtually all sectors of human endeavour (Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham2006; Bipp & Kleingeld, Reference Bipp and Kleingeld2011), available evidence suggests that not every employee, educator, manager or organisation knows how to do it or do it well (Lee, Reference Lee2015). Surveys done at different times in the United Kingdom found that up to 79% of British organisations (Institute of Personnel Management, 1992; Yearta, Maitlis, & Briner, Reference Yearta, Maitlis and Briner1995) and 62% of companies use goal-setting as employee management tool to motivate organisational effectiveness (Baron & Armstrong, Reference Baron and Armstrong2004; Bipp & Kleingeld, Reference Bipp and Kleingeld2011). While this seems an impressive goal-setting practice in UK companies and organisations, a qualitative study by Greenbank (2001) involving 58 owner-business managers reports a rather poor goal-setting practice in small-scale businesses in the United Kingdom, because any goal-setting they did was informal, and objective statements were not written down. Hence, Platt (Reference Platt2002) in the United Kingdom, believes that very few out of the managers who know the meaning of the SMART acronym, also know how to formulate ‘good objectives that comply with all the criteria’ (p. 23). Likewise, the ad hoc report of Doran (Reference Doran1981) in the United States that outlines the famous SMART criteria for objective-setting 36 years ago, asserts that formal goal-setting may be absent or at best ineffective in most American companies.

Significantly, goals are the foundational blocks that form the base on which organisations and programmes are built, and good goals are therefore essential management tools that all results oriented organisations must have (Mullins, Reference Mullins1999). Well formulated goals, serve three basic functions. First, they provide a conceptual framework for planning strategies and their component activities that are required to achieve desired results (Mullins, Reference Mullins1999). Second, they are the monitoring benchmarks that enable objective appraisal of the quality and progress of implementation, which is done to determine whether or not the organisation or programme is on its planned course (Mullins, Reference Mullins1999; Bipp & Kleingeld, Reference Bipp and Kleingeld2011). Third, they are the rational tools for evaluating the relevance and overall value of policies, services and projects at the end of implementation, which allows empirical judgement of the effectiveness, efficiency and success of work, and demonstration of management accountability for expended resources at all levels (Shiell, Reference Shiell1997; Greenbank, Reference Greenbank2001; Fitsimmons, Reference Fitsimmons2008; Bipp & Kleingeld, Reference Bipp and Kleingeld2011). Hence, referring to goals in a healthcare context, Shiell (Reference Shiell1997) asserts that, ‘the success of health service delivery at clinical, planning or system level must be measured against agreed objectives’ (Abstract). In agreement, an Oracle white paper (Oracle, 2012) in business and industrial contexts emphatically asserts that, ‘the organization that makes it a priority to develop quality, effective goals will succeed in its performance management, [and] in its business in general’ (p. 2). Therefore, goal-setting, the process of formulating goals, has been regarded as a characteristic feature of every well-managed organisation (Beardshaw & Palfreman, Reference Beardshaw and Palfreman1990; Bratton, Callinan, Forshaw, & Sawchuk, Reference Bratton, Callinan, Forshaw and Sawchuk2007).

The origin of scientific goal-setting as we know it today can be traced back to Fredrick W. Taylor’s time and motion studies at the beginning of the 20th century, in which he assigned daily tasks as goals to ‘blue collar workers’ (Locke, Shaw, Saari, & Latham, Reference Locke, Shaw, Saari and Latham1981). Pierre Dupont followed up the work of Taylor by testing Taylor’s ideas with managers at Dupont Powder Company and General Motors. The work of Duport probably formed the basis for Peter Drucker’s system of Management by Objectives in 1954 (Locke et al., Reference Locke, Shaw, Saari and Latham1981). According to Locke and Latham (Reference Locke and Latham2002), Mace (Reference Mace1935) was the first to publish any work on the effects of goals on task performance; and they then founded their own research work on the published works of researchers such as Atkinson in 1958 who reported a curvilinear relationship between effort and task performance, and Ryan (Reference Ryan1970) who linked the positive effect of conscious goals on action or behaviour. However, there was no formal goal-setting theory based on empirical evidence until Locke and Latham published their theory of goal-setting and task performance in 1990. From their own work, Locke and Latham concluded that the relationship between specific and difficult goals and task performance is positive and linear. This they then aligned with Albert Bandura’s social cognitive theory of the positive causative effect of motivation and cognition factors within given environments on desired behavioural change (Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham2002). Locke and Latham’s theory was the product of many empirical researches in cognitive psychology conducted over a period of many decades, and which began with finding answers to the question of whether goal-setting influences a person’s task performance (Locke, Reference Locke1968). According to Latham and Locke (Reference Latham and Locke2007), by the beginning of the 21st century, the goal-setting theory had provided a theoretical framework for more than 1,000 empirical studies.

Purpose of review

This paper is primarily a review of available literature on the concepts of goals and goal-setting, aimed at describing current knowledge and practice and identifying gaps in literature for further explorative research on the subject in healthcare. It specifically reviews the definitions and classifications of goals as well as the philosophy and frameworks of goal-setting practice in a general context.

METHODS

To the large extent, the step by step approach recommended by Cronin, Ryan, and Coughlan (Reference Cronin, Ryan and Coughlan2008) for a traditional or narrative literature review methodology was used because it enables a broad search for relevant materials sufficient to summarise and synthesise available knowledge on the subject. Three phases of organised literature search were done using online databases accessed through the university of Bradford library search sites, Google and Google scholar. The initial database search included Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) and Emerald. Both database sources were selected because of their wide collection of peer reviewed journals relating to healthcare and management researches. The key words used were ‘goal-setting’, ‘objective setting’, ‘framework for setting objectives’, and ‘management by objectives’. No time frame was used in the search through Google scholar. None was also initially selected for the HMIC and Emerald databases, but the search was later restricted to the period from 2005 to current (January 2016). Using ‘objective setting’ for example, a total of 38,844 was generated by the HMIC database. The Emerald management database generated 81,608 articles for goal-setting, 51,053 for framework for setting objectives and 97,212 for management by objectives. The search results were scanned for articles with titles that include the terms ‘goal-setting’ and only sources that gave access to downloading the articles – abstract or full document through the university library web links were printed for review. In this first phase, no article was excluded on the ground of year of publication. The second phase of literature search was more restricted, but included a multiple database search that connected six databases, including CINAHL, EBSCOhost (eBook collection), Medline, PsycARTICLES, Psychology & Behavioural Sciences and Psych.INFO. In the second search, the key phrases used were ‘Goal-setting’, ‘Framework or model or theory’, and ‘Health’. When the three phrases or words were searched with ‘AND’ 2,617 articles were generated. This number reduced to 1944 when the dates of publication were limited to the 10 years from 2006 to 2016. The third phase searched for more recent journal articles published during the 5-year period from 2013 to 2018, accessed through the websites of four management journals recommended by a reviewer of this article, using only the broad key words ‘Goals, Objectives’. The search through the website of Academy of Management Journal produced a result of 9,993 articles as abstracts, but only four articles were selected for review based on relevance to the goal concept. The search through the website of Journal of Management provided a link to all SAGE journals and a result of 2,231 articles for Health Sciences from which seven relevant articles were selected. The search of Journal of Management and Organisation (Cambridge Core) produced 403 articles because restriction to articles that give open access in the field of Medicine, Life sciences and Nutrition. Only one relevant article was selected. Even though 932 articles were generated through Strategic Management Journal, none were considered relevant.

A total of 65 goal-setting articles found from the database searches as full articles or abstract were selected for review. The oldest article is dated 1982 and the most current are dated 2017. In addition, some secondary sources, such as the paper by Doran (Reference Doran1981), cited in these articles were traced through the links in the references in the primary sources, in a way that describes ‘snow-balling’ technique, using either google or google scholar search engines. Textbooks, including dictionaries and titles relating to organisational management, available to the author and with indexed materials on goals, objectives and goal-setting, and the recent articles written by the author were also included in the review as sources.

RESULTS

Terminological definitions of a goal

In Collins English Dictionary, a goal is simply ‘aim or purpose’ (Collins, 2006: 363). Oxford Social Care Dictionary defines it as ‘an end result’ that work is specifically performed to achieve (Harris & White, Reference Harris and White2013: 229). Hence, popular goal-setting theorists render the meaning of the term similarly as the purpose of an action whose end-result is expected to be achieved at a particular time in the future (Lee, Locke, & Latham, Reference Lee, Locke and Latham1989; Stretcher et al., Reference Stretcher, Seijts, Kok, Latham, Glasgow, DeVellis, Meertens and Bulger1995; Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham2002, Reference Locke and Latham2006; Fitsimmons, Reference Fitsimmons2008). In addition, some authors in the field of organisational management defined the term as a timed future accomplishment that the whole organisation is working hard to attain, which could be either the immediate or ultimate objectives to which the effort of employees are directed (Beardshaw & Palfreman, Reference Beardshaw and Palfreman1990; Mullins, 1999; Bratton et al., Reference Bratton, Callinan, Forshaw and Sawchuk2007). However, other authors in the same sector Mullins (1999) also equates ‘objectives’ etymologically to terms such as ‘goals’, ‘aims’ or ‘end-result’. Other related terms such as ‘target’ have been used interchangeably with goals, aims and objectives as their synonyms in goal-setting literature, which suggests that the distinction of the meanings of the different goal concepts may be terminologically hazy in the academic arena (Ogbeiwi, Reference Ogbeiwi2016).

On the contrary, in development and health sectors, while goals generally express the expected results or desired effects of a planned action or work, they can differ in type, meaning and formulation, depending on the level of organisational or programme framework at which they are set (Ogbeiwi, Reference Ogbeiwi2016). Accordingly, the use of the term ‘goal’ in development organisations means a higher-order objective, and has the same meaning as ‘aim’ or a long-term goal in a healthcare context. To many health organisations, an objective is a short-term goal, achievable as an intermediate milestone on the path towards attaining the overall aim (OECD, 2002; Save the Children, 2003). Therefore, in the typology of goals, the terms ‘aims’, ‘objectives’, and ‘targets’ are considered different types of the generic term ‘goal’ rather than its synonyms, and each has a distinctive conceptual framework that differentiates it according to a set of seven themes: object, scope, hierarchy, timeframe, measurability, significance, expression (Ogbeiwi, Reference Ogbeiwi2016).

Classifications of goals

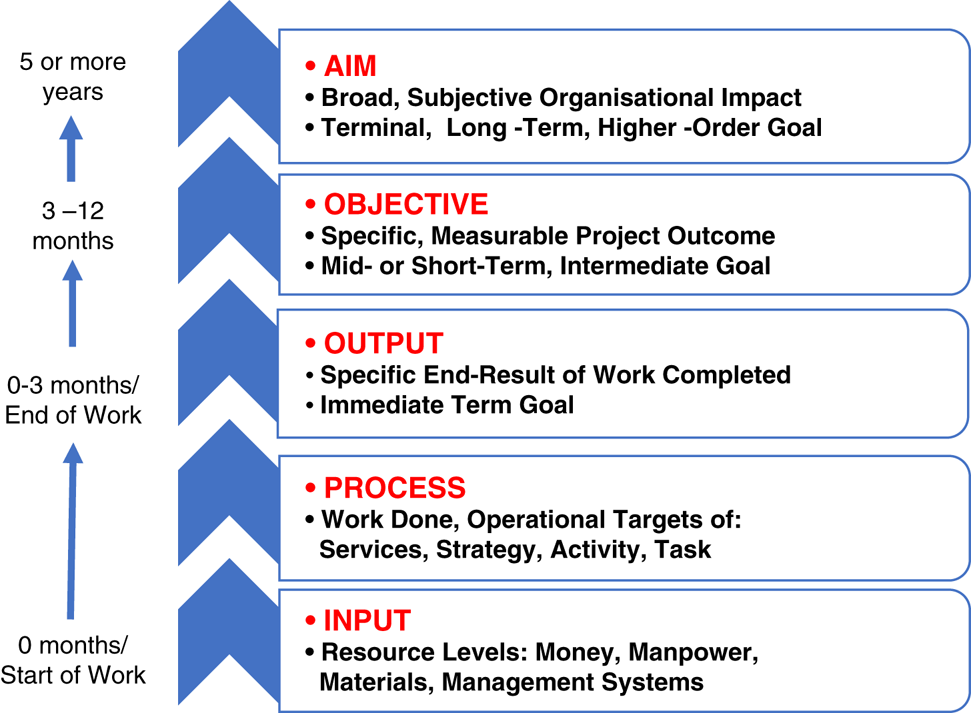

A goal can be formulated and written in different forms and types to suit the organisational context of goal setters. Figure 1 shows the basic typology of goals in a health context (Ogbeiwi, Reference Ogbeiwi2016), and illustrates the differentiation of goal types according to a linear directional framework into three levels of results of work: output (immediate goal), outcome expressed as objective (intermediate goal) and impact expressed as aim (terminal goal).

Figure 1 Types of goals in a healthcare context (adapted from Ogbeiwi, Reference Ogbeiwi2017)

Bratton et al. (Reference Bratton, Callinan, Forshaw and Sawchuk2007) differentiate two types: immediate and ultimate goals, and Mullins (1999) likewise wrote about broad purpose goals and specific accomplishment goals, or general and specific objectives. However, Mullins (1999: 119–120) also gives two different ways to classify goals types. The first differentiates goals into three types according to the concept of ‘power and compliance’ – including order goals (to restrain workers), economic goals (to set profit margins) and cultural goals (to satisfy social needs of workers). The second classification differentiates goals according to the types of organisational system results they represent: including consumer goals (e.g., consumer satisfaction targets), product goals (service/goods objectives), operational goals (performance targets) and secondary goals (sub-goals linked to the overall organisational aim).

Thus, in any service delivery system, goals are hierarchical, differing according to their organisational level and expected timeframe for attainment (Figure 1). Accordingly, they cascade both structurally downwards from general goals at the higher management levels to specific goals at the lower operational levels, and temporally upward from immediate goals to long-term goals (Bradley, Reference Bradley1999). General goals are broad aims or statements of expected long-term impact of intervention, futuristic visions and overall purposes of an organisation, while specific goals are either the immediate results of individual task performance or the intermediate or short-term outcomes of performance at team, project or sub-organisational levels. Some researchers like Whitehead (Reference Whitehead1998) differentiated general and specific goals simply as ‘Symbolic’ and ‘Action-oriented’ targets. From her description, symbolic targets are broad and unmeasurable goals stated at a higher organisational or national level intended to stimulate people to action. Action-oriented targets are specific goals that target a particular change to be achieved in a given population at a local level, with a measurement indicator and by a given time frame (Whitehead, Reference Whitehead1998). Some researchers have used other terms, such as ‘distal’ and ‘proximal’ goals to differentiate general and specific goals in line with their respective distant and near timeframes for achievement (Yearta, Maitlis, & Briner, Reference Yearta, Maitlis and Briner1995; Ginsburg, Reference Ginsburg2001). Clearly therefore, alternative terms for proximal and distal goals also refer to short-term and long-term goals (Kerr & LePelley, Reference Kerr and LePelley2013). This supports the impression that goals within an organisation can be hierarchical both temporally (in time) and structurally (in authority and responsibility).

Other binary classifications of goals exist in literature, including: quantitative versus qualitative goals, assigned versus participative goals, conscious versus subconscious goals, micro versus macro goals, difficult versus easy goals, specific versus vague goals, performance versus learning goals, and personal versus group goals (Erez & Earley, Reference Erez and Earley1987; Yearta, Maitlis, & Briner, Reference Yearta, Maitlis and Briner1995; Ginsburg, Reference Ginsburg2001; Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham2006; Zhang & Chiu, Reference Zhang and Chiu2012; Kerr & LePelley, Reference Kerr and LePelley2013; Sitzmann & Bell, Reference Sitzmann and Bell2015). These different systems of classifications indicate that types of goals are differentiated respectively according to their different properties of measurement, goal-setting approach, cognition, localisation, target, clarity, and purpose. Elaborating on the different goals-setting approach, Busse and Wismar (Reference Busse and Wismar2002a) describe an analytical model with two political coordinates of goal-setting. On this model, goals can be either ‘technocratic’ or ‘participative’. Technocratic goals are those set through prescriptive, assigned, non-consultative or top–down approach: they are goals formulated by the top management of an organisation and given to workers to accomplish. This goal type is therefore extrinsic to those who are expected to deliver them, and therefore may be less inspiring and owned than participative type. On the other hand, participative goals are agreed goals that emerge from a bottom-up consultative approach – begins with the participation and collaboration of all available and relevant stakeholders at the grassroots (Busse & Wismar, Reference Busse and Wismar2002b). Locke and Latham (Reference Locke and Latham2013) define three goal-setting approaches as the usual sources of goals in work performance settings. In addition to assigned and participative goal categories, they add ‘self-set’ goals. Unlike assigned or technocratic goals, which are set by others and given to employees, and participative goals, which are produced jointly by the employees and the management, self-set goals are those set by employees themselves, either individually or collaboratively as a team (Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham2002). In healthcare, collaborative goal setting is the norm for health personnel to work with individual patients to set their personal treatment improvement goals (Morris, Carlyle, & Lafata, Reference Morris, Carlyle and Lafata2016). Furthermore, Greenbank’s (Reference Greenbank2001) study of objective-setting by British micro-business owner-managers reports business or organisational goals as different from personal or own goal.

Philosophy of goal-setting

The goal concept encompasses the specific destination of service delivery, which is the purpose of effort being made at every organisational level, whether done by a single employee, a team, a department or the whole organisation (Oracle, 2012). According to Bratton et al. (Reference Bratton, Callinan, Forshaw and Sawchuk2007: 6), achieving goals is a basic expectation of every human activity. So, organisations or individuals working with no goals lack vital direction for their effort or destination for their journey. They exist functionally with no formal purpose. Thus, goals and goal-setting are therefore the essence of all organisations and their programmes (Mullins, 1999).

Some authors asserted that inherent in every goal statement is an expression of both a dissatisfaction with the current situation and a desire for change to a better future state (Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham2006; Day & Tosey, Reference Day and Tosey2011; Barbic et al., Reference Barbic, MacEwan, Leon, Chau, Salehmohammed, Kim, Khemda, Mernoushed, Khoshpouri, Osati and Barbic2017). Barbic et al. (Reference Barbic, MacEwan, Leon, Chau, Salehmohammed, Kim, Khemda, Mernoushed, Khoshpouri, Osati and Barbic2017) reviewed the short-term goals of 108 acute mental health patients at an emergency department and found the goals were based on their dissatisfaction with their housing, employment and social relationships. Yearta, Maitlis, and Briner (Reference Yearta, Maitlis and Briner1995) connected desired goals with the needs of people who set them. Hence, irrespective of the goal sources and types, the logical approach to goal-setting is problem-based (van Herten & Gunning-Schapers, Reference Van Herten and Gunning-Schapers2000a; Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham2002; Fitsimmons, Reference Fitsimmons2008), as goals are set to reflect the desired changes that are expected from the planned intervention of the problem situations affecting a particular population or organisation (Fitsimmons Reference Fitsimmons2008). Accordingly, in the description of a Health Policy Development Cycle by van Herten and Gunning-Schapers (Reference Van Herten and Gunning-Schapers2000a), setting goals begins with problem analysis that helps planners to understand the baseline situation of their target population that needs to change, and then to select a problem-relevant intervention for which related goals and action plans are formulated. A problem-based goal-setting approach is also illustrated by the four-step RAID model of Continuous Quality Improvement framework reported by Parker (Reference Parker2003), which she used in a clinical governance programme to transform the poor quality of patient care and low staff morale situation in a 25-bed acute psychiatric adult ward in London. The RAID model involved working with all stakeholders to Review the prevailing problem situation, Agree on solutions and setting high goals on a short and long-term, Implement solutions according to the clinical governance guidelines to beat deadlines, and then Demonstrate and Develop on changes by accurately measuring outcomes (Parker, Reference Parker2003).

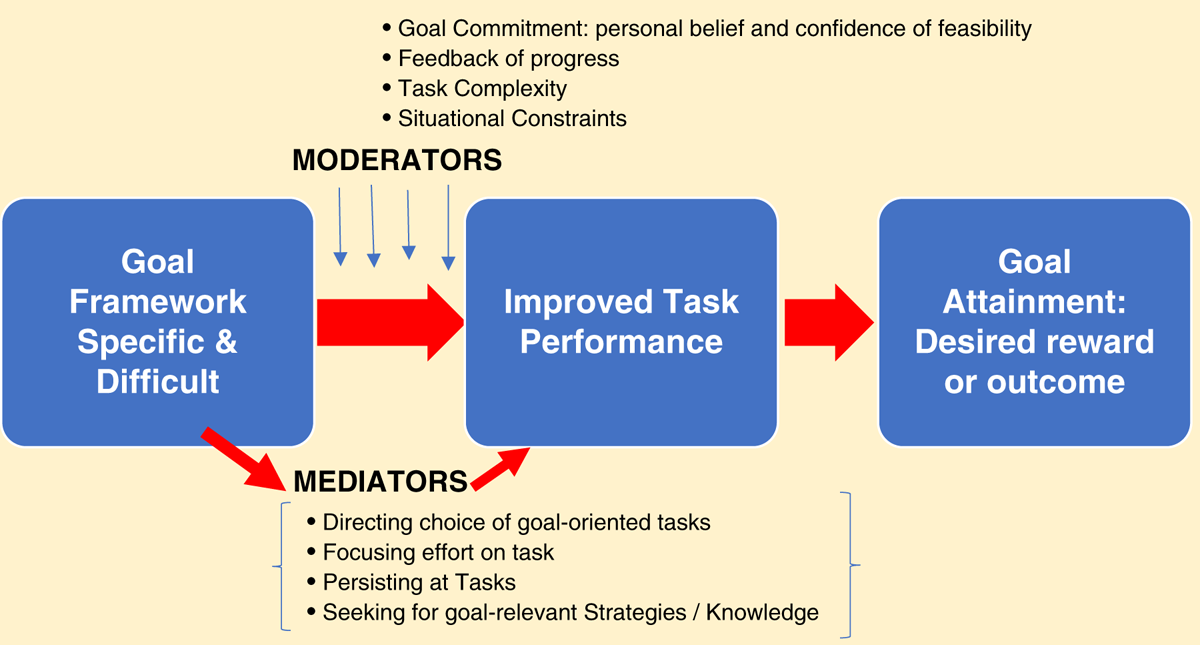

Moreover, the constructs of the goal-setting theory (Figure 2) provide evidence that the key philosophical reasoning behind goal-setting is its power to motivate the behaviour and effort of workers that are required as goal mediators to improve action performance towards achieving the desired changes or outcomes in any work-related setting (Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham2006). The Locke and Latham’s (Reference Locke and Latham1990) theory indicates that the desired goal effect only occurs when the goal framework is formulated to be specific and challenging, and where the necessary moderating factors are in place in the practical context of the organisation (Figure 2). According to Locke and Latham (Reference Locke and Latham2006: 265), ‘So long as a person is committed to the goal, has the requisite ability to attain it, and does not have conflicting goals, there is a positive, linear relationship between goal difficulty and task performance’.

Figure 2 Goal-setting theory (adapted from Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham2002)

Thus, Figure 2 shows the theory links goal framework as the independent variable in its theoretical relationship with goal attainment as the dependent or outcome variable and improved task performance as the key predictor variable. The directions of the arrows in Figure 2 show the mediating and moderating factors are also necessary predictors of higher task performance: they facilitate the goal effect by directly influencing improvement of task performance after goals with a specific and challenging framework have been set (Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham2002). Many further empirical researches based on the goal-setting theory, such as the ones by Brown, Jones, and Leigh (Reference Brown, Jones and Leigh2005), Campion and Lord (Reference Campion and Lord1982), Matsui, Okada, and Inoshita (Reference Matsui, Okada and Inoshita1983), Seijts and Latham (Reference Seijts and Latham2000), Wood, Mento, and Locke (Reference Wood, Mento and Locke1987), Yearta, Maitlis, and Briner (Reference Yearta, Maitlis and Briner1995), and Jansen and Paine (Reference Jansen and Paine2017) have explored the different mediators and moderators in the relationship between goal-setting and task performance and/or goal attainment, and concluded they are indispensable factors that must be present intrinsically in the individual workers and extrinsically in the organisational contexts for a goal-setting practice to be effective.

Particularly, the four mediators in Figure 2 are the mechanisms by which the goal effect on task performance happens. According to Locke and Latham (Reference Locke and Latham2002), goals motivate higher task performance by inspiring cognitive change in workers and management towards acquiring goal relevant behaviours, which reveals the directing, energising, persisting and strategising functions of structured goal-setting (Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham2013). Similarly, the four moderators are organisational factors that can have a positive control on the goal effects, when present (Wood, Mento, & Locke, Reference Wood, Mento and Locke1987; Seijts & Latham, Reference Seijts and Latham2000; Brown, Jones, & Leigh, Reference Brown, Jones and Leigh2005; Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham2006). The study by Medlin and Green (Reference Medlin and Green2009) expand this theory by adding two-employee predictor constructs as hypotheses in the relationship between goal-setting and tasks performance, including employee engagement (full involvement and enthusiasm in the job) and workplace optimism (unwavering belief in the ‘best possible outcome’).

However, an attempt by Yearta, Maitlis, and Briner (Reference Yearta, Maitlis and Briner1995) to replicate the relationships in Locke and Latham’s theory under non-experimental real-life organisational settings found reversed relationships between the key constructs of specific, difficult goals and task performance. Yearta Maitlis and Briner (Reference Yearta, Maitlis and Briner1995) discovered that the harder the goal in a normal work situation, the lower the task performance. Similarly, two other studies by Boyce et al. (Reference Boyce, Johnston, Wayda, Bunker and Eliot2001) and Erez and Earley (Reference Erez and Earley1987) tested the goal-setting theory using three goal-setting approaches (self-set, assigned, and do-your-best) to determine their effect on task performance in different work contexts. Similar to Locke and Latham (Reference Locke and Latham1990) theory, Boyce et al. (2001) reported that performance was better in the groups with specific goals, whether instructor set (assigned) or self-set, than in the group with vague ‘do-your-best’ goals. However, contrary to Locke and Latham’s (Reference Locke and Latham2002, Reference Locke and Latham2006) hypothesis that goal sources have no effect on outcome, both studies reported significant differences in outcomes with the different goal-setting approaches. Boyce et al. (2001) reported that performance was better in the assigned goal group than the self-set goal group, while Erez and Earley (Reference Erez and Earley1987) reported that participative goal-setting produced higher levels of goal acceptance and performance than the assigned approach, but with no significant effect of cultural differences.

Hence, like Yearta, Maitlis, and Briner (Reference Yearta, Maitlis and Briner1995), more recent authors such as Ordonez, Schweitzer, Galinsky, and Bazerman (Reference Ordonez, Schweitzer, Galinsky and Bazerman2009) and Kramer, Thayer, and Salas (Reference Kramer, Thayer and Salas2013) asserted that Locke and Latham’s goal-setting theory might not apply in every organisational context. Yearta, Maitlis, and Briner (Reference Yearta, Maitlis and Briner1995) concluded in their study that the theory does not consider organisational or work settings with multiple goals. Kramer, Thayer, and Salas (Reference Kramer, Thayer and Salas2013) inferred that the key factors in the goal-setting framework involving single goals for improving individual performance are different from the factors that prevail when goals are set for enhancing team or group performance, as team goals bring a social dimension with its social dynamics and a multi-level concept of individual, team and organisational goals to goal-setting. These same factors, according to Locke & Latham (Reference Locke and Latham2006), also inherently introduce into goal-setting the problem of goal conflict (where workers’ personal goals conflict with group or organisational goals), which Seijts and Latham (Reference Seijts and Latham2000) found hampers group performance. Therefore, Ordonez et al. (Reference Ordonez, Schweitzer, Galinsky and Bazerman2009) warned that Locke and Latham’s theory of goal-setting and task performance should not be seen as a ‘halcyon pill’ (p. 3) or panacea for motivating employee for better performance. They supported this by reporting the adverse organisational side effects of goal-setting experienced by organisations such as Sears, Roebuck and Co., Enron and Ford Motor Company. Ordonez et al. (Reference Ordonez, Schweitzer, Galinsky and Bazerman2009) therefore surmised that in organisational settings where goals are too specific, too narrow-focused, too many, too time inappropriate, and/or too challenging, they might encourage harmful, riskier and unethical behaviour of employees in response to the goal drive to improve performance toward winning rewards.

Nevertheless, there is agreement among a wide range of goal-setting researchers that goal-setting is generally useful as a motivational and inspirational management tool that can help employers and employees to become collaboratively focused on increasing the level of task performance, effort and capacity they needed to achieve desired outcomes (Yearta, Maitlis, & Briner, Reference Yearta, Maitlis and Briner1995; Bradley, Reference Bradley1999; Fulop & Hunter, Reference Fulop and Hunter2000; Ginsburg, Reference Ginsburg2001; Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham2002; Medlin & Green, Reference Medlin and Green2009; Kerr & LePelley, Reference Kerr and LePelley2013; Saari, Reference Saari2013). In fact, Nanji, Ferris, Torchiana, and Meyer (Reference Nanji, Ferris, Torchiana and Meyer2013) asserted that goals act as catalysts that inspire, motivate and stimulate progress. The goal-setting theory received full support from the IBM case study reported by Saari (Reference Saari2013), which was conducted for over 11 years, in which Gerstener used self-set stretch goals at every level of the company to transform their failing business. In addition, while defining stretch goals as goals purposely set at visibly impossible high levels, and so are therefore meant to drive employees and management of organisations to their maximum limit of performance, Kerr and LePelley (Reference Kerr and LePelley2013) reported how the concept was popularised world-wide as a major innovation to goal-setting by Jack Welch in General Electric (GE) in the 1980s and 1990s. Using goal setting, he enforced improvement of products and services to enable a massive savings of US$ 12 billion in a 4-year period (Kerr and LePelley, Reference Kerr and LePelley2013). Other mega companies that positively transformed their business outcomes through emulating GE’s stretch goal-setting included Commonwealth Health Corporation (CHC) in 1988 and Toyota Motors between 1997 and 2001 (Kerr & LePelley, Reference Kerr and LePelley2013).

However, Nanji et al. (Reference Nanji, Ferris, Torchiana and Meyer2013) reviewed the use of organisational ‘Big Hairy Audacious Goals’ goals: a bold type of stretch goals, which are overarching long-term goals (10–30 years) that require massive effort and have a 50–70% chance of attainment. They cautioned that despite its popularity, only 38% of organisations were successful to a full or limited extent. This conforms with the assertion by Yang, Gary, and Yetton (Reference Yang, Gary and Yetton2015) from their management simulation experiments that there is no evidence that stretch goals, despite their popular support, actually improve performance at the organisational level. In fact, some recent authors believe that extremely high-performance goals will have negative effects on organisations and agree with Ordonez et al. (Reference Ordonez, Schweitzer, Galinsky and Bazerman2009) that they could create opportunity for corrupt behaviours as employees strive against odds to achieve them (Yang, Gary, & Yetton, Reference Yang, Gary and Yetton2015; Welsh, Miller, & Cho, Reference Welsh, Miller and Cho2016).

Goal-setting frameworks

Many authors regard the use of frameworks as crucial concepts for effective goal-setting, because of their theoretical link to improvement of performance and achievement in programmes and organisations (Oracle, 2012). Historically, popular goal-setting models such as Drucker’s (Reference Drucker1955) management by objectives (MBO) has been known since the 1950s, and used extensively since the 1970s in America and Japan. However, MBO is reported to have depreciated both in its value and use by organisations (van Herten & Gunning-Schapers, Reference Van Herten and Gunning-Schapers2000b; Dahlsten, Styhre, & Williander, Reference Dahlsten, Styhre and Williander2005; Bipp & Kleingeld, Reference Bipp and Kleingeld2011). Dahlsten, Styhre, and Williander (Reference Dahlsten, Styhre and Williander2005) and Lindberg and Wilson (Reference Lindberg and Wilson2011) who studied the experience of MBO in Sweden in the 1990s, described how MBO was used to introduce participatory objective setting to organisations, in which specific, precise and measurable objectives were set for every organisational level. Furthermore, through the MBO process, overall organisational or corporate objectives were translated into shorter term objectives or sub-goals for all work levels and units of the organisation in a way that motivates workers and managers to control, monitor, and reward the progress of their work (Dahlsten, Styhre, & Williander, Reference Dahlsten, Styhre and Williander2005; Lindberg & Wilson, Reference Lindberg and Wilson2011).

According to Bipp and Kleingeld (Reference Bipp and Kleingeld2011) and Ogbeiwi (Reference Ogbeiwi2017), a number of other effective goal-setting frameworks have been developed over the past 20 years, including balanced scorecard approach by Kaplan and Norton (Reference Kaplan and Norton1996) and the productivity measurement and enhancement system by Pritchard, Harrell, DiazGranados, and Guzman (Reference Pritchard, Harrell, DiazGranados and Guzman2008). Some authors have examined how goal-setting-based models or frameworks are used in different sectors, such as the use of Object/Objective-Oriented Maintenance Management (OOMM) in the field of engineering reported by Zhu, Gelders, and Pintelon (Reference Zhu, Gelders and Pintelon2002). Bipp and Kleingeld (Reference Bipp and Kleingeld2011) assessed the goal-setting practice in a German company that used an un-named goal-setting framework in their annual planning cycle for more a decade. Their goal-setting approach was top–down: goals were formulated by the top management and cascaded through all organisational levels to individual employees. The goal-setting procedures involved using interviews to review the results of the goals for the past year before the goals for the next year were set, and the goal attainment of individual employees was linked to rewards. However, the article does not mention the kinds or example of goal statements set by the case company, and so, the extent to which the goals formulated through the reported process satisfy the required goal attributes is unknown.

Particularly in healthcare, there is evidence that goal-setting with different frameworks and approaches are traditionally used by many national governments to provide leadership, guidance, and strategic direction (van Herten & Gunning-Schapers, Reference Van Herten and Gunning-Schapers2000a). As earlier mentioned, van Herten and Gunning-Schapers (Reference Van Herten and Gunning-Schapers2000b) report the major role the use of a Health Policy Development Cycle has played in this regard. Busse and Wismar (Reference Busse and Wismar2002a, Reference Busse and Wismar2002b) from their review of policy documents of goals-based health programmes in countries in the European Union, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and United States argued that many health programmes in the developed countries have failed because of the kind of goal-setting process employed and the intervention areas focused by their health targets. According to them goal-setting was mostly the non-participative technocratic approach and, in most of the countries, health targets focused on intervention areas outside the health sector. In their papers, they advocated for an integrated and balanced approach that incorporates both top–down and bottom–up approaches for a successful goal-setting in healthcare delivery systems (Busse & Wismar, Reference Busse and Wismar2002a, Reference Busse and Wismar2002b).

Furthermore, Langford, Sawyer, Giomo, Brownson, and Toole (Reference Langford, Sawyer, Giomo, Brownson and Toole2007) reviewed the effectiveness of the Self-Management Goal Cycle framework as a model for diabetic care in the United States and concluded that collaborative goal-setting with diabetes patients is effective for enhancing their self-management skills. Scobbie, McLean, Dixon, Duncan, and Wyke (Reference Scobbie, McLean, Dixon, Duncan and Wyke2013) reported that both patients and health professionals found the Goal-Action Planning model beneficial and acceptable in stroke rehabilitation. Some studies reported the use of WHO’s International Classification of Function, Disability and Health and the Talking Mats as coded guides for patient goal-setting and action planning in special communication and rehabilitation need settings (Bornman & Murphy, Reference Bornman and Murphy2006; Murphy & Boa, Reference Murphy and Boa2012); and the use of Goal Attainment Scaling as an effective framework for the evaluation of the achievement of treatment goals (Balkin, Reference Balkin2013; Brady, Busse, & Lopez, Reference Brady, Busse and Lopez2014). Another two goal-setting frameworks reported in healthcare improvement planning are total quality management and continuous quality improvement initiatives (Ginsburg, Reference Ginsburg2001; Parker, Reference Parker2003; Medlin & Green, Reference Medlin and Green2009). These frameworks provide practical guides or steps for the process of setting goals (Ogbeiwi, Reference Ogbeiwi2017). None, however, is a goal-setting framework that guides how the structure of a goal statement should be formulated or constructed, such that it possesses the theoretical core goal attributes required to motivate task performance and achieve desired outcomes (Ogbeiwi, Reference Ogbeiwi2017).

According to Locke and Latham (Reference Locke and Latham2013), to have a specific and difficult structure, goal statements must have a framework with two attributes or components: Goal content – that is, it states the specific quantifiable performance result to be achieved, and Goal intensity – that is, the goal-setting practice factors including the mediating goal-setting effort, the moderating individual goal commitment, and the goal hierarchy. Yearta, Maitlis, and Briner (Reference Yearta, Maitlis and Briner1995) simply explain the goal content as the structure that makes a goal-specific and difficult, while the goal intensity as the needed goal commitment as well as the other factors of goal-setting practices. Authors like Bipp and Kleingeld (Reference Bipp and Kleingeld2011) adapted the Locke and Latham’s goal attributes to their local cultural contexts in Germany in their study of the employee perceptions of the goal-setting theory-based practices. In their study, the descriptive attributes of goal content included goal clarity, and absence of goal conflict, goal stress and dysfunctional goal effects (Bipp & Kleingeld, Reference Bipp and Kleingeld2011).

Framework for writing SMART goal statements

Doubtlessly, one of the most popular developments on the Locke and Latham’s theoretical goal attributes that has generated a lot of research interests over the years is Doran’s (Reference Doran1981) set of five SMART criteria that spell out the attributes of an effective goal statement as Specific, Measurable, Assignable, Realistic and Time-related. In these criteria, Doran (Reference Doran1981) recommended that SMART objectives should state ‘a specific area for improvement’, ‘an indicator of progress’, ‘who will do it’, ‘what results’ can be accomplished given the resource context of the organisation, and ‘when the result’ (p. 36) will be attained. Unlike other goal-setting frameworks, SMART criteria prescribe the structural components for writing or formulating a goal statement, such that it possesses all five SMART attributes (Oracle, 2012). According to Bipp and Kleingeld (Reference Bipp and Kleingeld2011), the SMART framework sets out the criteria for the ‘effective use of goals in performance management or appraisal’ (p. 308). Oracle (2012) recommended SMART framework as the gold standard required for writing any goal statement.

However, Day and Tosey (Reference Day and Tosey2011) considered SMART criteria inadequate for formulating learning goals and instead recommended Zimmerman’s (Reference Zimmerman2008) eight criteria for appropriate learning goals that evolved from the combination of both Locke and Latham’s goal-setting theory and Bandura’s social cognitive theory to the development of educational goals. On Zimmerman’s criteria, appropriate learning goals must be specific, challenging, proximal, hierarchical, conscious, self-set, performance or process related, and congruent to self and others’ goals (Day & Tosey, Reference Day and Tosey2011). Day and Tosey asserted that the SMART criteria while drawing upon the principles of Locke and Latham’s goal-setting theory to produce learning goals that are specific and challenging, may not produce goals that are attainable on a short-term and can engage the student’s commitment to learn. However, unlike Doran’s SMART criteria, Zimmerman’s criteria do not provide any clarity of what framework components should be in a goal statement to make it fulfil the eight attributes. Hence, Day and Tosey (Reference Day and Tosey2011) attempted to fill this gap by proposing a five component ‘P.O.W.E.R.’ framework for writing educational goal statements that they claimed satisfy Zimmerman’s criteria; where the acronym means stating: Positive outcome desired, Own role, What task to be done (with dates), Evidence of accomplishment and Relationships required.

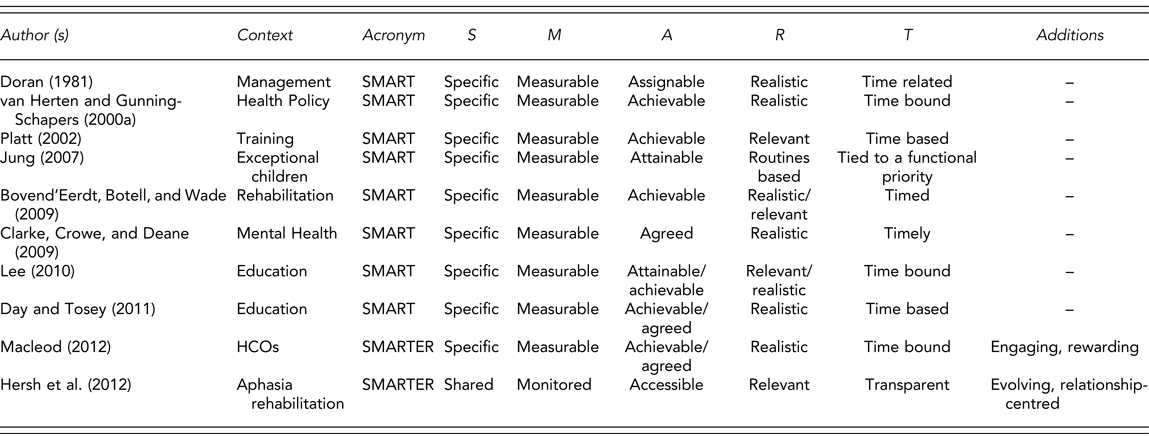

Therefore, it appears the perceived inadequacy in the SMART criteria has made recent authors to amend the original SMART attributes and acronym since Doran first published them in 1981. Table 1 shows the definitions of SMART found in 10 journal articles, including Doran’s, and reveals that most revisions retained the first two criteria of ‘specific’ and ‘measurable’, but changed the remaining three by substituting or adding other attributes that the proponents considered more appropriate. Two of the most recent articles even proposed a SMARTER acronym, while one, Hersh, Worrall, Howe, Sherratt, and Davidson (Reference Hersh, Worrall, Howe, Sherratt and Davidson2012), reported a completely different set of attributes.

Table 1 Definitions of the SMART acronym for effective goals in journal articles

Note. HCOs=health care organisations.

Less orthodox sources reveal that the revision of Doran’s SMART is widespread. For example, the white paper by Oracle (2012) exchanged Doran’s ‘assignable’ with ‘attainable’, ‘realistic’ with ‘relevant’ and ‘time-related’ with ‘timely’; and reported other authors’ attempts to lengthen the acronym with various new attributes. The revised acronyms in Oracle (2012) include ‘SMART-ER’ (engaging, rewarding), ‘SMART-C’ (challenging or collaborative), ‘SMART-S’ (stretch, sustainable, significant), and ‘SMA-A-RT’ (actionable). In addition, Oracle outlines that in writing a SMART objective, the statement should specify the ‘outcomes to be delivered’, a means of measurement that ‘can be objectively assessed’ and a ‘delivery date or schedule’ (p. 10). Rather than add any structural components to the goal statement, the remaining two Oracle criteria can only be considered during its formulation, that is, to be attainable, the employee should have access to all resources needed to achieve it, and to be relevant the objective should be aligned with other goals of every management level of the organisation. Similarly, the toolkits of some popular health organisations recommend the revised SMART criteria. In addition to specific and measurable, Save the Children’s (2003) toolkit claims SMART means ‘Achievable, Relevant and Time-bound’ (p. 254). Even different departments within Centre for Disease Control and Prevention proffer differing meanings, adding ‘Achievable, Realistic and Time-phased’ (CDC, 2009: 1) or ‘Attainable/Achievable, Relevant and Time-bound’ (CDC-DHDSP, 2017: 3) to Specific, and measurable.

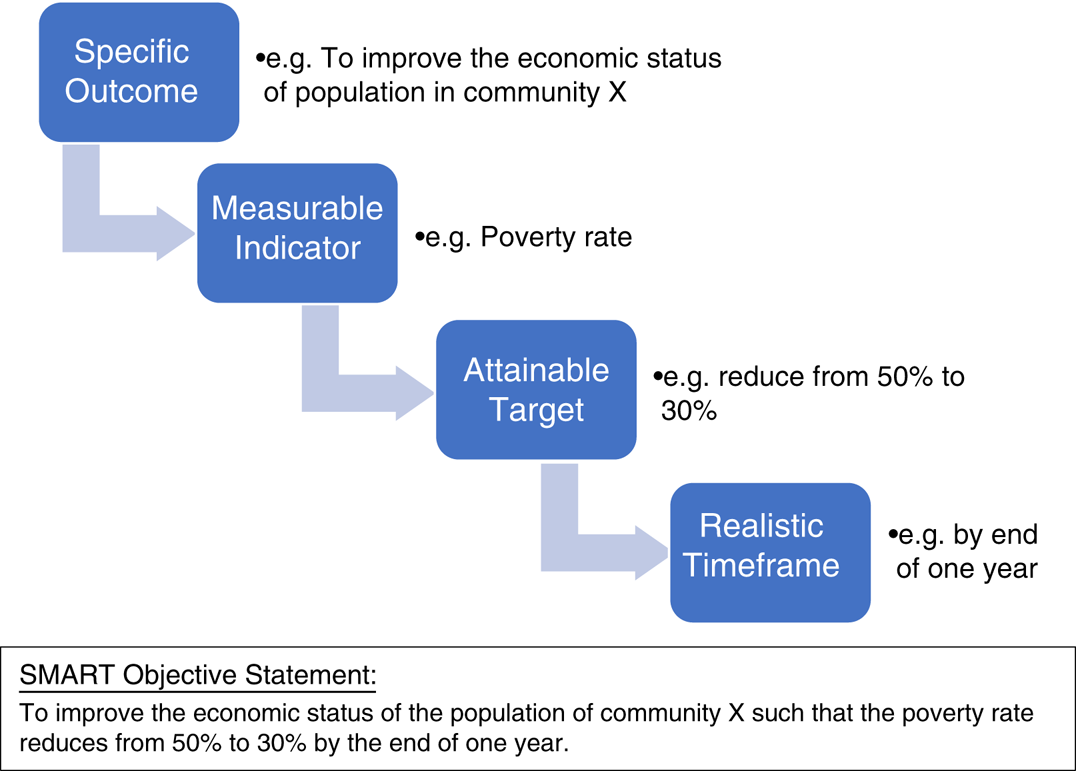

Therefore, with few exceptions like Jung (Reference Jung2007) and Hersh et al. (Reference Hersh, Worrall, Howe, Sherratt and Davidson2012), among recent authors, there is more agreement with the Doran’s SMART criteria of ‘specific’ and ‘measurable’ as acceptable attributes of an effective goal statement, than with ‘assignable’, ‘realistic’ and ‘time-based’. While the exclusion of assignable in a goal statement is probably understandable, it is not clear if there is any hermeneutical justification for the disagreements over either of the two sets of related terms: attainable, achievable, realistic and relevant, or time-based, time-related, time-bound and timely. Accordingly, in earlier reviews, Ogbeiwi (Reference Ogbeiwi2016, Reference Ogbeiwi2017) reduced Doran’s original five-goal components for writing an objective statement to a four-component OITT framework illustrated in Figure 3, which includes specifying outcome, indicator, target and time-frame, and excludes the person to whom the goal is assigned.

Figure 3 OITT Framework of an SMART objective statement (Ogbeiwi, Reference Ogbeiwi2016, in press). SMART Objective Statement: To improve the economic status of the population of community X such that the poverty rate reduces from 50 to 30% by the end of 1 year

Still, examples of a SMART goal or objective statement that possesses all four framework components required to satisfy the recommended criteria or goal attributes are rare to find in published articles on SMART goal setting. Thus, indicating that the majority of academic reviews and empirical researches on goal-setting and framework attributes are silent about the extent to which actual goals formulated in real-life management practice are truly specific, measurable, attainable, realistic or time bound. However, Platt (Reference Platt2002) assessed the smartness of 11 objectives against a template of his SMART criteria of specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-based and considered only two as SMART, including: ‘To have agreed, set and recorded 3 performance targets with each member of staff by the end of June 2003’ and ‘To achieve 500% reduction over previous year on transport costs (end of this week)’ (p. 25). However, none of these ‘SMART’ objective statements contain a complete set of SMART components if assessed on the OITT framework in Figure 3. The first example is task-oriented, having a target and timeframe, but lack an outcome and indicator measure. The second example states an indicator (transport cost), target (500% reduction) and timeframe, but lack an outcome. Ogbeiwi (Reference Ogbeiwi2017) conducted a similar review of 17 published examples of SMART objectives and found that none possessed a complete set of outcome, indicator, target and timeframe. Hence, there is an apparent lack of capacity to formulate statements of SMART goals or objectives with the attributes to be useful as effective goals.

DISCUSSION

Goal-setting has generated a massive research interest in the past 4 decades, as evidenced by the large collection of literature sources found and reviewed. However, we cannot claim that a robust review of contemporary concepts of goals and goal-setting has been done with this narrative review methodology, as it uses a search strategy that is considered less structurally organised than the more empirical systematic review (Cronin, Ryan, & Coughlan, Reference Cronin, Ryan and Coughlan2008). Nevertheless, ample evidence gathered from the sources reviewed has enabled a reasonable overview of current knowledge of goals and goal setting that is fundamental to contemporary understanding and application of the management concepts.

This review finds that answering basic questions such as ‘What is a goal?’ may not be so simple, given the massive haziness and confusion that surround the definitions and differentiation of the related goal terms of goals, objectives, aims, or target in both academic literature. Apparently, the debates on whether they are synonyms or not in management circles is not new (Doran, Reference Doran1981). While Doran believes that whichever term is used may not be practically relevant in all contexts, Macleod (Reference MacLeod2012) thinks the confusion is pointless as the understanding the entire concept and theory of goal setting is still evolving. Both authors, however, assert that a clearer differentiation of each goal term, as a different type of expected results of work done, will enable their better application in organisational goal setting practices, especially at the executive level. A detailed thematic synthesis to harmonise the definitions and differentiate the meaning of each term was reported by the author (Ogbeiwi, Reference Ogbeiwi2016).

Overall, the different classification systems in literature indicate that goals exist as different types, differentiable by their contextual, structural, functional and temporal characteristics. Contextual characteristics refer to goal differences in the goal-setting process or approach: how they are set, for example self-set, assigned and participative goals. Structural characteristics refer to the goal differences in their content or what goal framework with which they are formulated or how they are stated, for example specific, broad, general or vague goals. Functional characteristics refer to the different goal purposes or uses, which goal aspects or changes in the organisation’s work they are expected to achieve or why they are set, for example performance and learning goals. Temporal characteristics refer to the different goal timeframes or when they will be achieved, for example immediate-term, short-term or long-term goals. This observation is compatible with the Locke and Latham’s (Reference Locke and Latham2002) description of core goal attributes in their goal-setting theory, which differentiated goals according to their content and intensity, with goal content further elucidated as the goal specificity, clarity and difficulty. The goal classifications have major implication on planning in organisational settings, where goals can be set for the desired effect of performance at different levels of individual, team, departmental and organisational tiers (Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham2006; Fitsimmons, Reference Fitsimmons2008). Therefore, like Oracle (2002) and Fitsimmons (Reference Fitsimmons2008) advise, effort should be made during planning to logically link or align the lower-level goals with the higher goals, also referred to as micro-level and macro-level respectively by Yearta, Maitlis, and Briner (Reference Yearta, Maitlis and Briner1995) and Locke and Latham (Reference Locke and Latham2006); as well as align personal goals to organisational goals, and vice versa, to ensure goal relevance and goal commitment by employees at all levels (Zhang & Chiu, Reference Zhang and Chiu2012). However, Zhang and Chiu (Reference Zhang and Chiu2012) assert that alignment of personal goals will only motivate individual employees if the goals are also shared goals at the group level.

The evidence found in articles reviewed shows that research about goals in organisations has been evolving for more than 100 years, and, therefore, the understanding of the goal concept is still emerging. Current knowledge show that the goals underscore the direction and destination of an organisation. So, to be relevant to the needs of the organisation and their target population, they should be formulated using a problem-based approach, to reflect the desired change from a problematic status quo, knowing the power of goals to motivate behavioural change (Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham2006). However, the implication of the goal setting theory by Locke and Latham (Reference Locke and Latham1990) and the battery of models and frameworks that have been developed on it by other authors is this: goals can only motivate improved performance towards achieving the desired change if they are written in a structural framework that makes them specific and challenging, and due attention given to the behavioural mediators in the relationship between goal setting and task performance, and the employee and organisational moderators of goal effect (Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham2002). Hence, despite the doubts in some authors that the theory may not be replicable or applicable or even generalisable to every work setting (Erez & Earley, Reference Erez and Earley1987; Yearta, Maitlis, & Briner, Reference Yearta, Maitlis and Briner1995; Boyce et al., 2001; Ordonez et al., Reference Ordonez, Schweitzer, Galinsky and Bazerman2009; Kramer, Thayer, & Salas, Reference Kramer, Thayer and Salas2013), empirical evidence shows that goal-setting theory provides a formidable framework for understanding and further studying the positive and directional effects of goals (MacLeod, Reference MacLeod2012).

Most existing goal setting frameworks only outline practical steps for setting goals in the different contexts, but do not provide any framework for formulating or writing good goals statements. This apparently informed the universal interest in Doran’s SMART criteria and the components they recommend should constitute the framework of an effective goal statement. However, there seems to be controversy over which attributes of the SMART acronym appropriately define a good goal in today’s work contexts. The summary of the basic components in Doran’s criteria according to literature is: SMART goal statements or objectives must have four basic components, to be specific, measurable, attainable or realistic, relevant and time bound (Ogbeiwi, Reference Ogbeiwi2016, Reference Ogbeiwi2017).

So far, no literature has been found with written examples of SMART objectives that fully possess all framework components required to write statements with the five attributes of SMART goals. This is compatible with findings made from a recent review by Ogbeiwi (Reference Ogbeiwi2017). Equally, there is no previous research inquiry found to have examined the process of formulation of SMART goal statements according to these attributes and components in any health service provision contexts. To what extent are the current goals of organisations and programmes in different work sectors SMART? Can the goal framework or way they are formulated and written motivate achievement of their desired outcomes? The answers to these questions are currently unknown. Clearly these are obvious gaps for further research.

CONCLUSIONS

The terminological confusion in the definitions of goal terms in popular usage still prevents a clear understanding of how the goal concepts can be applied effectively in existing organisational goal setting practices. This review finds that goal types are multifarious, and vary according to the organisational goal-setting contexts as well as the structural, functional, and temporal attributes of the goals set. Locke and Latham’s (1990) theory of goal setting and task performance provides a framework for understanding the philosophy of goals, especially that the goal framework could influence attainment of desired outcomes, under specific individual employee and organisational conditions. However, evidence of research exploring the components of a framework for writing statements of actual goals that the work of organisations and programmes can be logically planned is still lacking.

Acknowledgement

Sincere thanks to Drs Bryan McIntosh and Barbara McNamara, my academic supervisors at the Faculty of Health Studies, University of Bradford, UK, who read and commented on the original literature review report from which this paper was developed.

Declaration

This article is an original work of the author and has not been submitted or published elsewhere and aligns with the scope of this journal by seeking to update the knowledge of the readership with the current concepts of goals and goal-setting. Some materials from the authors previous articles are used in some sections, especially definitions, goal setting theory and the framework. These are appropriately cited and referenced. There is, however, no conflict of interest as this review was not supported by any external funding or obligations.

About the Author

Osahon Ogbeiwi, MBBS, MCommH, MA, AFHEA. Doctoral researcher at Faculty of Health Studies, University of Bradford. His doctoral study is on the broad topic of ‘Goal-setting in Healthcare’ and specifically exploring as a qualitative case study the ‘Leprosy goal-setting practice of The Leprosy Mission Nigeria’. He has previously published 2 articles on goal definitions and SMART goal framework in the British Journal of Healthcare Management, and another on leprosy goal-setting is in press.