Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had a significant impact on individuals, organisations and societies. It has disrupted lives – through personal and job losses, career shifts and challenges to individuals’ physical and mental health. Organisations have had to pivot and channel resources towards new ways of working as several traditional approaches became unsustainable and no longer viable. Sustained and periodic lockdowns, as well as the reorganisation of jobs and work (Stevano, Ali, & Jamieson, Reference Stevano, Ali and Jamieson2020) have also constrained economies and limited the exchange of trades and services (Maliszewska, Mattoo, & van der Mensbrugghe, Reference Maliszewska, Mattoo and van der Mensbrugghe2020).

Within workplaces, there has been a shift in norms as a result of the pandemic, and organisations have had to swiftly adapt to the new circumstances. The rise in remote work arrangements is one such adaptation (Brynjolfsson, Horton, Ozimek, Rock, Sharma, & TuYe, Reference Brynjolfsson, Horton, Ozimek, Rock, Sharma and TuYe2020). Remote work is traditionally defined as work ‘performed outside of the normal organisational confines of space and time’ (Olson, Reference Olson1983, p. 182). In 2020, this has involved employees working at home, often communicating in virtual workspaces online as a result of COVID-19's physical distancing requirements and city-wide lockdowns. Remote work can produce several gains for both employees and organisations, but is likely to also bring about various challenges or losses. Virtual workspaces have disrupted home life for several employees, with some parents working at home together – prompting the renegotiation or maintenance of roles around caring for children and engaging in other family and care duties (Bahn, Cohen, & van der Meulen Rodgers, Reference Bahn, Cohen and van der Meulen Rodgers2020).

We draw on conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989) and the challenge–hindrance framework (Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling, & Boudreau, Reference Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling and Boudreau2000) to demonstrate how employees access and draw on key resources while working from home during COVID-19. We illustrate that access to and use of key resources impacts future resource gains and subsequently influences wellbeing and productivity, and thus mutual gains for managers and employees. We further explore how a lack of resources begets future resource losses or inadequacies, presenting challenges for individuals to thrive and perform when working from home.

In exploring the theme of mutual gains between human resource management (HRM) and employees in the context of remote working, the paper centres on one case: a work unit within a large resources firm in Australia. The work unit was required to work from home for several months during 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. This organisation did not have prominent working from home policies or practices prior to the pandemic, and thus swift adaptation from both employees and the organisation was required. Through a series of qualitative phases of data collection (including both self-report data from diary entries and follow-up interviews), we explored the experiences of employees working from home. We captured their perceptions of the associated gains, losses and challenges encountered in the process of working from home. We also explored views on the role of HRM structures and systems, particularly relating to workload, work–life balance practices, technology systems and team dynamics.

This study makes three key contributions. First, through the use of qualitative case study methodology, this study sheds light on remote working experiences during a specific period of forced flexibility. Studies indicate that the prevalence of remote work will continue to increase in the future, so this study's findings will have ongoing relevance (Eddleston & Mulki, Reference Eddleston and Mulki2017; Ozimek, Reference Ozimek2020). Second, this study highlights the risks and challenges associated with the forced flexibility of remote work. Third, it applies and extends COR theory and the challenge–hindrance framework to explore the role of resource gains and losses in enabling (or hindering) wellbeing and productivity.

The impact of COVID-19 on work and organisations

COVID-19 has led to a shift in remote work from being a discretionary flexible work policy to a mandatory requirement for knowledge workers' jobs and for those for whom it is possible to work from home (Gallacher & Hossain, Reference Gallacher and Hossain2020). As a blanket requirement in several organisations, all employees, rather than just those who opt-in, were faced with working remotely for at least a portion of 2020 (Craig & Churchill, Reference Craig and Churchill2021).

COVID-19 has meant that workers with a vast array of personal and family circumstances have been forced to work remotely, and thus face different challenges when working from home, such as balancing caring responsibilities or coping with internal and external distractions (Desrochers, Hilton, & Larwood, Reference Desrochers, Hilton and Larwood2005; Nash & Churchill, Reference Nash and Churchill2020).

Organisations too, have been differentially prepared for a COVID-19 response, and have varied in their approach and management of the transition to, and practice of, remote work and other changes. Differing practices, including the allocation of important enabling resources for working from home, such as adequate equipment, technology and effective online communication practices (Leonardi, Treem, & Jackson, Reference Leonardi, Treem and Jackson2010; Rockmann & Pratt, Reference Rockmann and Pratt2015) are a case in point.

More than forcing several employees into distanced or remote work arrangements, COVID-19 has further challenged the capacity of organisations to adapt swiftly (and safely) to changing, unprecedented circumstances (Spicer, Reference Spicer2020). Furthermore, rapid change and the sustained physical distance between employees and managers places challenges on the degree to which individuals remain identified with the organisation (Ashforth, Reference Ashforth2020). Pressure to remain resilient and relevant while simultaneously engaging in efforts to develop and retain staff adds to the business as usual (BAU) requirements for an organisation's long-term welfare and survival (Ashforth, Reference Ashforth2020; Plimmer et al., Reference Plimmer, Berman, Malinen, Franken, Naswall, Kuntz and Löfgren2021). Indeed, employees and organisations have faced increased and unprecedented challenges in regard to how work is done in the COVID-19 era.

Remote working

Remote working, often synonymously referred to as telework or telecommuting, is a prominent form of flexible working that includes the ability and/or requirement to work away from the usual office environment, at home, or while mobile (Barsness, Diekmann, & Seidel, Reference Barsness, Diekmann and Seidel2005; Eurofound & the International Labour Office, 2017). Although remote working has increased in prominence over the last 30 years, the practice has recently become much more commonplace, enabled by a myriad of bespoke and general use online technologies and communication platforms. This has transformed home offices into virtual workspaces.

Typically, and particularly in the context of Australia, the administration of remote and flexible working arrangements falls to the formal HRM function within organisations. There are two reasons for this. First, under Australia's Fair Work Act (2009), all employees have provision to request flexible working arrangements. Accordingly, HRM personnel within organisations are responsible for employee relations and legislation compliance and as such the HRM function sets the policies. Second, recent law cases from separate state jurisdictions across Australia have successfully claimed that organisations remain liable for the health and safety of employees while working remotely and/or from home. As such, HRM is responsible for setting up systems to ensure compliance with operational health and safety frameworks.

Managers and leaders also have a key role in the implementation of flexible and remote working policies (Golden & Fromen, Reference Golden and Fromen2011; Poulsen & Ipsen, Reference Poulsen and Ipsen2017). Typically, managers are responsible for approving remote working requests from staff (using procedures devised by HR). Empirical research has tracked the key role of managers in ensuring business continuity when remote working arrangements are deployed (Choi, Reference Choi2018; Golden & Fromen, Reference Golden and Fromen2011). The research concludes that managers need to draw on more relation-based management techniques, move away from task-oriented approaches, and emphasise outputs rather than inputs (i.e., where and when work gets done).

Forced flexibility

Forced-flexibility, introduced to enable business continuity, has presented numerous challenges for employees, managers and organisations. Working remotely during the pandemic has posed a paradox for employees. Specifically, employees who have spent most or all of their time working inside the physical boundaries of their organisations have had to adapt to remote working quickly, at times resulting in difficulties segmenting work from private life (Chawla, MacGowan, Gabriel, & Podsakoff, Reference Chawla, MacGowan, Gabriel and Podsakoff2020).

The collision of work and home lives may contribute to heightened demands from both spheres, through increased external distractions and a loss of routine. The interconnections of work and family seem to be the most challenging aspect of working remotely for employees with children or carer responsibilities, but it is worth noting that employees without children are not immune to the negative consequences of altered working conditions on their wellbeing and may experience loneliness and a lack of purpose or resources (Carnevale & Hatak, Reference Carnevale and Hatak2020). However, as Sull, Sull, and Bersin (Reference Sull, Sull and Bersin2020) argue, working from home may in some ways provide employees with more time and opportunity to effectively balance conflicting demands of work and home if they have access to adequate resources, for example, technological and managerial support.

The forced flexibility resulting from COVID-19 has also raised the stakes for managers and organisations, particularly in contexts where remote working was not previously a prominent part of work policy or was considered as being impossible (e.g., the health sector) (Lee, Reference Lee2020). Managers are likely to face unique challenges in how to support and interact with staff who are working remotely (Poulsen & Ipsen, Reference Poulsen and Ipsen2017). In particular, they have had to prepare their employees for dramatically altered working conditions, including switching to working remotely or from home, and putting in place new policies and procedures to minimise human contact (Carnevale & Hatak, Reference Carnevale and Hatak2020). Along with the transition to altered working conditions, managers have needed to ensure that employees can handle work-to-life and life-to-work conflicts for the sustenance of their wellbeing and productivity. Hence, different types of organisational support, including emotional and instrumental, are critical to equip managers and employees with the necessary tools to overcome the challenges associated with the sudden shift in working conditions and ensure positive outcomes (French, Dumani, Allen, & Shockley, Reference French, Dumani, Allen and Shockley2018). In the same vein, Bentley, Teo, McLeod, Tan, Bosua, and Gloet (Reference Bentley, Teo, McLeod, Tan, Bosua and Gloet2016) have highlighted the need, at the organisational level, to have support mechanisms and structures such as technological resources and reporting policies. The same study also revealed that communication channels also need to be designed in ways that support remote working.

The current study seeks to provide insight into the complex challenges discussed above by focusing on the employee experience of remote work, and the role of the organisation, and HR specifically, in supporting this to create mutual gains during this period of forced flexibility and beyond. Through the lens of COR theory, integrated with the challenge–hindrance framework (Cavanaugh et al., Reference Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling and Boudreau2000), we aim to identify the gains and losses which impact employees' wellbeing and productivity while working from home during COVID-19.

Conservation of resources theory and its relationship with stress

The central tenet of COR theory is that ‘individuals strive to obtain, retain, protect, and foster those things that they value’ (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001, p. 341). In this endeavour, individuals draw on personal strengths, social attachments and aspects of cultural belongingness in order to survive in a context that they perceive as threatening. Furthermore, employee wellbeing may be impacted when an individual is threatened with loss of resources; where there is an actual loss of resources; or where an individual fails to acquire sufficient resources even after significant investment in resources (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989, Reference Hobfoll2001).

Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu, and Westman (Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018) proposed three corollaries related to the tenets and principles of COR. Corollary 1 is the notion that those with more resources are not as vulnerable to resources loss as individuals lacking resources. Corollary 2 relates to ‘loss cycles’, which occur when the resource loss spirals gain in magnitude, resulting in greater and greater resources losses (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018, p. 106). Corollary 3 is associated with ‘gain spirals’ and the notion that resource gain begets further resources (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018, p. 106). These spirals develop slower than loss cycles.

Studies show that not only does emotional stress increase at times of significant resource loss, the level of stress experienced during loss is reduced when accompanied by resource gains (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001). Hence, resource gains acquire their saliency when viewed in light of the individual's perceived loss and gain. Loss of resources may lead to a spiral of losses in future resources which can create continued negative impacts on wellbeing. This was exemplified in a study investigating workplace bullying and cyber bullying, where Gardner et al. (Reference Gardner, O'Driscoll, Cooper-Thomas, Roche, Bentley, Catley and Trenberth2016) found that resource loss can lead to poor physical and mental health, which in turn reduces the individual's ability to deal with work and other demands, often leading to further loss. Similarly, Herttuala, Kokkinen, and Konu (Reference Herttuala, Kokkinen and Konu2020) postulate that work wellbeing is an integral part of employees' holistic wellbeing, which includes their psychological, physical and social resources to meet work challenges. Having more challenges (losses) than resources jeopardises employees' wellbeing (Dodge, Daly, Huyton, & Sanders, Reference Dodge, Daly, Huyton and Sanders2012). Hence, the importance of understanding more about the impact that loss has on the overall wellbeing of employees, and organisational performance is evident, particularly in flexible remote work spaces where there is increasing research evidence about the impact of virtual and remote work on mental health (Poulsen & Ipsen, Reference Poulsen and Ipsen2017).

As established above, job resources are valuable in preventing, or at least mitigating, different forms of stress experienced by employees. The challenge–hindrance framework, used as an extension to COR theory, is relevant here (Cavanaugh et al., Reference Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling and Boudreau2000). Resources such as supervisory support, positive co-worker relationships, autonomy, and, in this case, technological assistance and communication, may influence whether a demand is perceived as a hindrance or a more manageable challenge (Dawson, O'Brien, & Beehr, Reference Dawson, O'Brien and Beehr2016).

Challenge–hindrance framework and resources

Demands that are challenging (also termed challenge stressors), rather than hindering, can be potentially beneficial in that they stretch employees in a reasonable and achievable manner (Searle & Tuckey, Reference Searle, Tuckey, Leiter and Cooper2017) and promote opportunities for growth and development (Ventura, Salanova, & Llorens, Reference Ventura, Salanova and Llorens2015). In other words, they are manageable obstacles. Hindrance stressors, on the contrary, are demands which are deemed unmanageable. Hindrance demands often include interpersonal conflict, organisational constraints and red-tape (LePine, Podsakoff & LePine, Reference LePine, Podsakoff and LePine2005) and are experienced by employees in ways that thwart growth and development (Albrecht, Reference Albrecht2015).

In experiencing the unmanageability of hindrance demands, employees may retreat and withdraw from potentially productive work behaviours in an attempt to preserve existing resources (Dawson, O'Brien, & Beehr, Reference Dawson, O'Brien and Beehr2016). Such actions are consistent with corollary 2 of COR, which states that resource loss leads to and magnifies future resource losses, resulting in a ‘loss cycle’ (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). In the remote working context, there is arguably a higher risk of withdrawal due to the fact that several resources are not as readily available or visible as in face-to-face arrangements. Without transparency or understanding of the resources available to buffer demands, coupled with social isolation from direct co-worker or supervisor contact, stressors may increase in perceived severity and, therefore, manageability. From this view, it is essential for remote workers to be provided with adequate levels of visible and meaningful support to enable the effective balance of preservation and further use of relevant job-related resources for both wellbeing and productivity. This kind of support is consistent with COR's corollary 3 as purported by Hobfoll et al. (Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018), whereby support for resources, and resource gain, leads to the acquisition of further resources.

This study draws on COR theory as well as the challenge–hindrance framework to explore experiences of remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic. With a particular focus on wellbeing and productivity, we posed the following research questions (RQs) to guide our study:

(1) What are the challenges associated with changes in work dynamics during and post-COVID-19?

(2) How has remote working impacted processes related to productivity and performance?

(3) How has remote working impacted processes related to wellbeing?

Method

Contextual background

The study investigated the experiences of managers and employees from one work unit in a large resource-sector organisation in Australia. The Australian resources sector comprised of organisations involved in the generation of resource commodities such as natural gas, aluminium, coal and iron ore, and accounts for over 70% of the country's goods exports (Department of Industry, Science, Energy, & Resources, n.d.). The participants of this study worked in professional and field-work areas of the resources sector.

Data collection was undertaken over 2 months, and explored the process of the change in work dynamics due to the radical implementation of flexible working arrangements across the organisation during March and April 2020. For some, who already worked from home one or more days per week or worked remotely from other team members, this was not completely foreign territory; however, for most of the team, significant adjustments were made to how, where, and when they worked.

Prior to this event, team members described their work context as one underpinned by high work intensity (i.e., high demand work that is cognitively challenging) and high work variety (i.e., undertaking several tasks across one or more components of a portfolio of work, one or more programmes and one or more projects). In combination, they reflected a high-performance work team, comprising high-level talent, operating in a coordinated fashion to deliver broad and varied team goals.

The change in work context meant that team members had to balance new demands associated with working remotely, in addition to the BAU work context described above. The extent of the change was significant and entailed extensive learning of new technologies and ways of working, as well as balancing new demands. The new demands related to heightened family responsibilities, increased internal demands and external distractions.

Using a qualitative case study approach, we explored the challenges, stressors and demands associated with the change, and the impact of these on wellbeing and productivity, from the experience of both managers and employees. The findings create a narrative of the experience in adopting flexible working arrangements in response to a specific event.

Research phases

This qualitative study contained two distinct phases: a Diary Study conducted during the event, and a Critical Event Study conducted immediately after the event, yet still during a period of disruption that warranted continued flexible work arrangements. Prior to the commencement of the study, the organisation invited all 25 employees working within the team to participate by completing diary entries for 4 days across a 2-week period in April 2020. Eleven respondents (three team managers and eight team members within the work unit) responded to the first phase of the study.

The second phase commenced immediately after the mandatory remote working response to COVID-19 was eased, and comprised of an online survey and in-depth interviews.

The critical incident technique (CIT) was used in the second phase of data collection. The CIT is a qualitative research method suited to collecting and analysing narratives in such a way that facilitates their usefulness in solving practical problems (Butterfield, Borgen, Amundson, & Maglio, Reference Butterfield, Borgen, Amundson and Maglio2005). For this study, the method enabled a deeper and more detailed understanding of work events and associated experiences. In this phase, participants were asked to recall a positive and a negative event that had occurred over the past month in relation to their experience of working remotely. This was followed by a series of probing questions. Both phases were designed to explore the three RQs.

Data collection and analysis

Diary study

A self-completion data collection sheet was used to collect diary entries. Individual team members were asked to bring to mind one positive and one negative event that had occurred during the day of diary completion associated with working remotely. Each participant wrote from the view of the following four aspects of the work system: the working environment, the work itself, one's self and relationships. In most cases, respondents provided single sentence comments. The diary data were analysed by organising the various comments under the four categories listed above for both positive and negative events, comprising then a total of eight event categories. Where multiple references were made to a particular type of positive or negative event, this was identified as a theme.

Critical event study

An online questionnaire was distributed to all members of the five participating work teams. Participants were asked to describe their experiences and challenges, and their approaches to adapting to the demands of the changes to work dynamics and the workplace. Their responses formed story-telling narratives (n = 15). Analysis of the story-telling narratives involved examination of key challenges, demands and stressors, and wellbeing and performance enhancing responses, adaptations and innovations (Flanagan, Reference Flanagan1954). The CIT was further employed in the seven follow-up interviews, from which a deeper and more detailed understanding of working experiences developed. The interviews were conducted by three different researchers.

Data analysis

Yin's (Reference Yin2013) qualitative analysis method was utilised to first organise, then derive meaning from, text-based responses concerning each team member's perception of salient (positive and negative) work experiences during the event. Next, the RQs were used to identify the key challenges for those working remotely during the mandatory remote working response to the COVID-19 period. This included preferences and concerns of workers regarding future flexible work arrangements in a post COVID-19 work environment. A number of themes were identified and then extracted separately by three members of the research team. This was followed by a discussion until consensus on the identified themes was reached (Cascio, Lee, Vaudrin, & Freedman, Reference Cascio, Lee, Vaudrin and Freedman2019).

Participant characteristics (critical event study)

The diary study data were collected anonymously and internally by the case study organisation, prior to the critical event study. Critical event participants consisted of eight male and seven female team members completing the online questionnaire, and four male and three female team members participating in the online interviews. All participants who completed the questionnaires indicated that they were in a relationship (married or de facto), and most (n = 13) had children or dependents in their home during the initial COVID-19 lockdown period. Of the 13 respondents with children or dependents, 12 were responsible for the day-to-day care of their dependents. The number of people living in the household ranged from two to five, with more than half of the employees having more than four people in their home during the event.

Findings

Analysis of the data suggests that, over time, team members adapted to the flexible remote work environment and valued the increased productivity it engendered. To better understand the mutual gains for employees and organisations during the period of change, and to identify areas where HRM can facilitate and support change processes to promote mutual gains, the findings are presented using a time-based narrative starting with the findings from the diary study.

Flexible working experiences described during the event

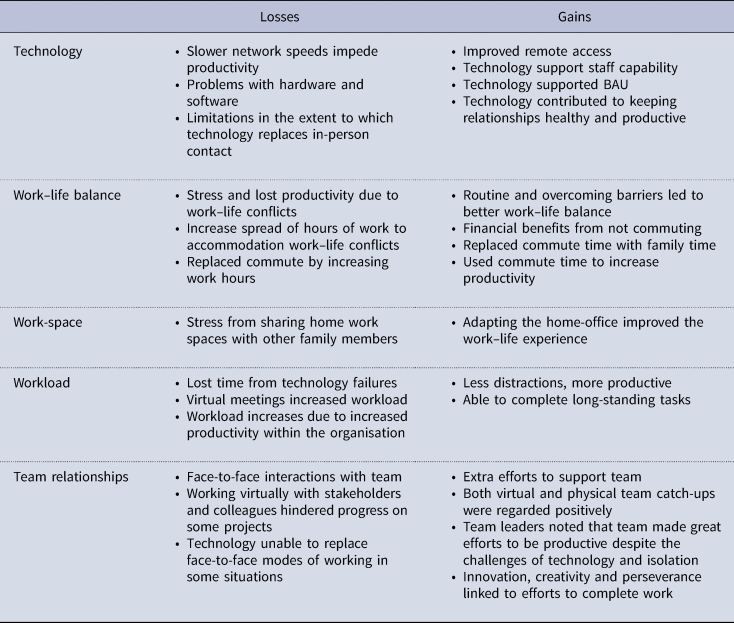

The diary study captured each team member's self-reported positive and negative experiences during the COVID-19 lockdown period. To respond to the RQs proposed in the study, the categories of the working environment, the work itself, the self and relationships were used. The analysis revealed that the experiences could be described using the following five themes: technology, work–life balance, the physical workspace, workload and team relationships. Within these themes, the perceived losses and gains of flexible work for employees and their managers were identified (see Table 1).

Table 1. Losses and gains associated with working remotely noted during the event

In addition to the perceived losses and gains noted by participants in the diary study (Table 1), it was noted that the impact of the challenges experienced changed over time. For example, a substantial challenge associated with changes in work dynamics during and post-COVID-19 (RQ1) was technology. This challenge was associated with the early period of change to flexible work which happened rapidly. Similarly, some respondents appeared to have initial difficulty working at home, especially where the home-office space was also being used by their partner. For some, this situation improved as new spaces and work patterns were adapted. Furthermore, work–life balance and work-to-family/family-to-work conflict issues were frequently noted in the diary comments and also changed over time. Typically, the earlier diary entries raised or alluded to the difficulties of working with both partners and children in the house concurrently which caused both stress and a reduction in work productivity. For some, this also resulted in working long hours and working during the night to make up for lost daytime productivity. Later diary entries, however, were more positive about work–life balance issues, as children returned to school and participants and their partners found routines for office sharing and identified the best times and locations to work effectively. These experiences exemplify the change from demands being viewed as unmanageable to manageable, such that obstacles were eventually overcome. As demands become more achievable over time, resources could be deployed more effectively.

Flexible working experiences described immediately after the event

To explore the challenges associated with changes in work dynamics during and post COVID-19 (RQ1), and understand the impact of remote working on productivity/performance (RQ2) and wellbeing (RQ3), the diary study identified five themes that captured the remote working experience. The analysis of the surveys and interview data collected immediately after the event revealed parallel themes. Therefore, the findings from the survey and interviews are presented using the same five themes: technology, work–life balance, the physical workspace, workload and team relationships. Hence, the survey and the follow-up interviews provided further insight into the themes identified through the diary study.

Technology

The most frequently mentioned challenges were associated with technology. When employees commenced remote working during COVID-19, it was a new experience for everyone. One employee explained that ‘new technology with thousands of people connecting remotely’, meant that no-one knew, ‘if it would even stand up to large numbers of people connecting’ (Employee, Survey E4). One manager (Interview B1) captured the general feeling early in the COVID-19 response, saying that there, ‘was a bit of adjustment with the technology’. The challenges experienced early in the flexible remote working experience were mostly related to using new technology or using existing technology in new ways, such as the ‘different skill set[s] with different aged people’ and the ‘shift from human interaction to technology’ (Manager, Interview B1). For some individuals, such challenges were overcome through effective teamwork and technological support:

The technology initially was making us 25–50% less efficient. So we had to change processes about how we did things [and share] ideas for how to do things. Team was good and innovative. The tech people also got things sorted after a while which also helped. (Manager, Interview E1)

Once the change settled in, participants experienced various different challenges in the process of remote work itself. Most commented on the technological challenges in either collaborating with colleagues or external stakeholders while working from home. According to one manager (Interview E1), the technology was not sufficient to ‘deal with large datasets’, and an employee (Interview A2) said that ‘the virtual platform is just not set up for collaboration’ with external stakeholders. Another manager (Interview E1) explained that ‘On any given day, one of the team would have a data issue – NBN, our servers, etcetera’.

The IT support and efficiency in providing timely advice and assistance played a key role in enabling team members to work from home efficiently and effectively, and to deliver the expected outcomes. Experiencing IT issues with tight deadlines for deliverables, however, led to feelings of stress for some team members. One manager (Interview B1) highlighted, ‘Let's assume you have an issue at home, it's not easily resolved by actually going and seeing an IT person’. This is an example of resources not being as readily available in remote work as they are in face-to-face contexts, which can inhibit access to further resources such as time and information required to get a job done.

We are constantly on the phone with the IT people and they have worked hard to resolve the issues, but can take days or weeks to fix it. But no prob[lem]s in last few weeks. (Employee, Interview E4)

Over time, the impact of technology on the experience appeared to become more positive as the team became more skilled in how they used their personal and job resources, as well as more familiar with the capabilities of the wider team. In several cases, individuals were able to find and generate effective work-arounds.

Work–life balance

One of the main benefits of embracing flexible working arrangements is the work–life balance benefits, illustrated in the below quote:

The positive has been everyone being accommodating to flexible working and understanding that everyone has got life outside of the business whether its kids, study, which probably, before, people would just schedule things. (Employee, Interview E5)

Both employees and managers reported feeling that they had a better work–life balance while working remotely. A manager (Interview A5) explained, ‘Life has been more balanced working from home flexibly’ and an employee (Survey C5) said, ‘I actually found myself more balanced. I've just got home from going for a walk’. The flexibility of working remotely is further illustrated below:

A lot of us have found a lot of value in working from home. You just get the flexibility; you can make dinner while you're at home. You can put the washing on, and all that kind of stuff, and that is really helping people's mental health. (Manager, Survey A5)

In terms of RQ2 regarding the impact of remote working on productivity and performance, employees reported that they had more time with family when working from home, often as a result of time freed-up by not commuting and the ability to spend time with family members during work breaks, reflective of a series of resource gains. By splitting the work hours and completing the work both within and outside of traditional working hours, employees reported that they could maximise work productivity and time with family, signalling a skilled deployment of job and personal resources. For example, one employee (Survey C5), said, ‘I split my work hours to enable balance and make it work as others were having to home school kids’. This contributed to having work–life balance, thus, enjoying both family time and delivering efficient and quality work outcomes. This is further supported below:

The critical point was about the output in these two hours that was most important, not trying to do it all together. Then, a real sense of relief. I was a good dad and a good employee. (Manager, Survey A1)

Regarding the impact of remote working on wellbeing (RQ3), collectively, most employees expressed their feelings of happiness and satisfaction during the process of working flexibly from home. A number of team members, however, reported feeling overwhelmed and stressed about the heightened and competing demands they faced. When team members felt overwhelmed and unable to embrace the flexibility of working from home, they often reported a negative emotional response to their remote working experience. Emotional exhaustion and burnout seemed to be a reality for those who found the new demands unmanageable, or difficult to balance with the resources available. One employee (Interview A2) ‘took a leave day to cope with the added workload during WFH’.

Employees also reported feeling isolated, both personally and professionally. Professional isolation also brought with it a diminished sense of trust in co-workers and managers to maintain and fulfil their job responsibilities. This experience of being overwhelmed stemmed from both personal and work demands, and the need to balance both simultaneously.

For one manager (Interview A1), there were five people, including three children under five, in the house. He explained the effect that this had:

It didn't work. [We] tried to figure out ways of doing things. [We] tag teamed and had one watching kids while the other worked. Eight hours work, eight hours with kids, eight hours sleeping. So, not enough hours in the day… In the end, we gave up counting hours, it was about getting on top of the work (switching to outputs-based). Put a lot of pressure on the family.

Some team members felt an increase in work responsibilities, particularly through taking on responsibilities outside their own job requirements due to a breakdown in communication or a lack of trust in a co-worker to fulfil their responsibilities in the new, more flexible, work context. Other stressors related to childcare responsibilities and managing the distraction of partners also working from home and sharing working spaces.

The physical workspace

For some people the move to the home office was easier because they already had a workspace set-up, and for some the home workspace was considered better than their office workspace:

Absence of open planned office space helped work get done quicker as direct reports weren't around asking questions. I imagine this is what would happen if we had offices. (Manager, Survey A5)

In contrast, for others setting up a home office and buying necessary equipment during COVID-19 created additional stress in the beginning. Most, however, found that once they had set-up a suitable workspace, or created a workable compromise with family, the challenges were fewer:

I wasn't organised with a home office pre-COVID-19 (just used my laptop at home). House didn't have a dedicated office space (had to rearrange). (Manager, Survey A1)

For some team members, the obstacles prevailed and they were not able to find a workable compromise due to specific work or family requirements or external factors beyond their control. For example, one manager (Survey B1) found that their home office was not ‘set up for meetings’ and that noise was an ongoing issue with nearby construction activities.

Workload and productivity

In terms of the impact of remote working on productivity and performance (RQ2), respondents reported that even though the workload generally increased, they were able to balance this more effectively with life demands and achieve the same, or better, productivity at the end of the day:

I can actually be more productive instead of having that travel time to go and sit in a meeting room where I'm just on a laptop, where at home I've got big screens'. (Employee, Interview C3)

Productivity benefits came from having more distraction-free time to focus, no commute, and also from being able to choose times in the day that best suited them for completing tasks. One manager (Survey A5) reported a benefit of remote work as having, ‘alone time’ to complete work free of ‘distractions/interruptions from team members’. For others, external distractions such as noises from neighbours as well as boundary issues from the integration of work and family life had a negative impact on their work–life balance and wellbeing. One manager (Survey B1) stated that ‘construction has had significant impacts on stress’, explaining further in an interview that ‘the hardest piece was the building next door, they demolished that place literally on the Monday…. It's been machines, saws, nail guns, everything that you can ever think of’ (Manager, Interview B1). Not surprisingly, factors outside of one's control represented a significant barrier to embracing remote working. In these situations, team members often felt overwhelmed and even stressed about the multitude of hindrance demands facing them in this new flexible work context.

Some respondents experienced negative work–family and family–work conflicts, although these tended to be earlier on in their experience of remote working and improved as they, and their family members, adapted to the new working conditions. For many the competing priorities, distracting home environment, fixed mindset or unsuitable workspace did not enable them to successfully manage the boundary challenges and led to working longer hours, family conflict and increased stress.

Checking emails after dinner. Answering emails when we wouldn't normally answer emails. I should have told the team to switch off – but the workload is led by the business, who don't stop requiring things done. (Manager, Interview E1)

Workload increases were reported by the majority of employees. One manager (Interview E1) estimated that there was a ‘30% increase in workload due to COVID-19’ and another said, ‘COVID dramatically increased workload’ (Manager, Interview A1). Employees also commented on workload increases saying that they were, ‘working extra hours without even noticing’ (Employee, Interview A2) and ‘less travel means workload increased. Working 10 h days’ (Employee, Interview E4). It appears that for most employees the workload remained steady or increased as a result of increased activity in other areas of the organisation. As one manager explained (Interview E1), the ‘workload went up because people in other groups were getting to work on things because COVID-19 gave them the time’.

Personal resources of stoicism and pragmatism were evident where employees reported the need to ‘just get things done’ in regard to achieving required outputs. One employee (Interview E4) explained that ‘even when the system goes slow you keep on persevering. That bloody-minded approach is instilled in the team’. Hence, perseverance appeared to play a role here too, with team members reporting the importance of maintaining composure and focus in order to find workarounds, and new ways of meeting job demands. For some employees the increased access to work systems afforded by the technology together with a reduction in commute time led to working longer hours. For example, one employee (Survey E7) reported that they were able to ‘start work a little earlier one day and stay online a little [sic] later. If I had been working in the office then the commute home (by bike) would have been past sunset and not ideal’. Similarly, a manager (Interview B1) reported working longer hours, saying, ‘You can find yourself sitting there for ten hours a day, next to the desk and working at 8:30 at night just because the laptops there’.

Workload did not follow the pattern of the other themes which were more intense at the start but then reduced over time. According to the team, they remained productive during the period due to strong leadership, teamwork and the individual qualities that team members have which enabled them to embrace the flexibility of working remotely, despite the increased challenges and demands.

Team relationships

Team dynamics were crucial in ensuring that the work of the team continued efficiently and effectively during and immediately after the event. Both managers and team members emphasised the strong team dynamics and the role team members played in supporting each other, in finding innovations to overcome adversity in relation to working constraints, and in finding the best ways to get things done within the constraints of the flexible remote work environment.

The team was able to continue to operate, even without working in office with face-to-face engagement. Collaboration still happened without those ad hoc conversations. Technology helped, but also the drive within people to find different ways to work and keep working. (Manager, Interview A1)

It was also noted by several respondents that team members made a big effort to stay in touch and catch-up informally, where they would not have under normal working conditions, aiding morale and team relations.

Around the middle of May, I organised a lunch in the local park – the team all worked nearby. We all had lunch in the park and socialised. Good team bonding – talked about non-work issues. (Manager, Interview E1)

One employee (Survey D5) described the ways in which technology was used for collaboration saying, ‘The team set up other communication avenues (WhatsApp) to maintain connection and team members offered support of working from home with little ones’. Support from both the organisation and co-workers enabled team members to embrace the flexibility and adapt to the remote working environment. Support came in the form of strong leadership from line managers, whereby managers trusted team members to work well autonomously:

My boss allows us to be autonomous [and has] trust that we are all doing our job. (Manager, Interview A5)

Good performance was also recognised by line managers which helped employees stay motivated in the new, and for some – foreign, working environment. This finding is consistent with the comments of both leaders and team members in the diaries, collected during enforced remote working, showing that these perceptions and experiences endured over time.

Outcomes: performance, work–life balance and wellbeing

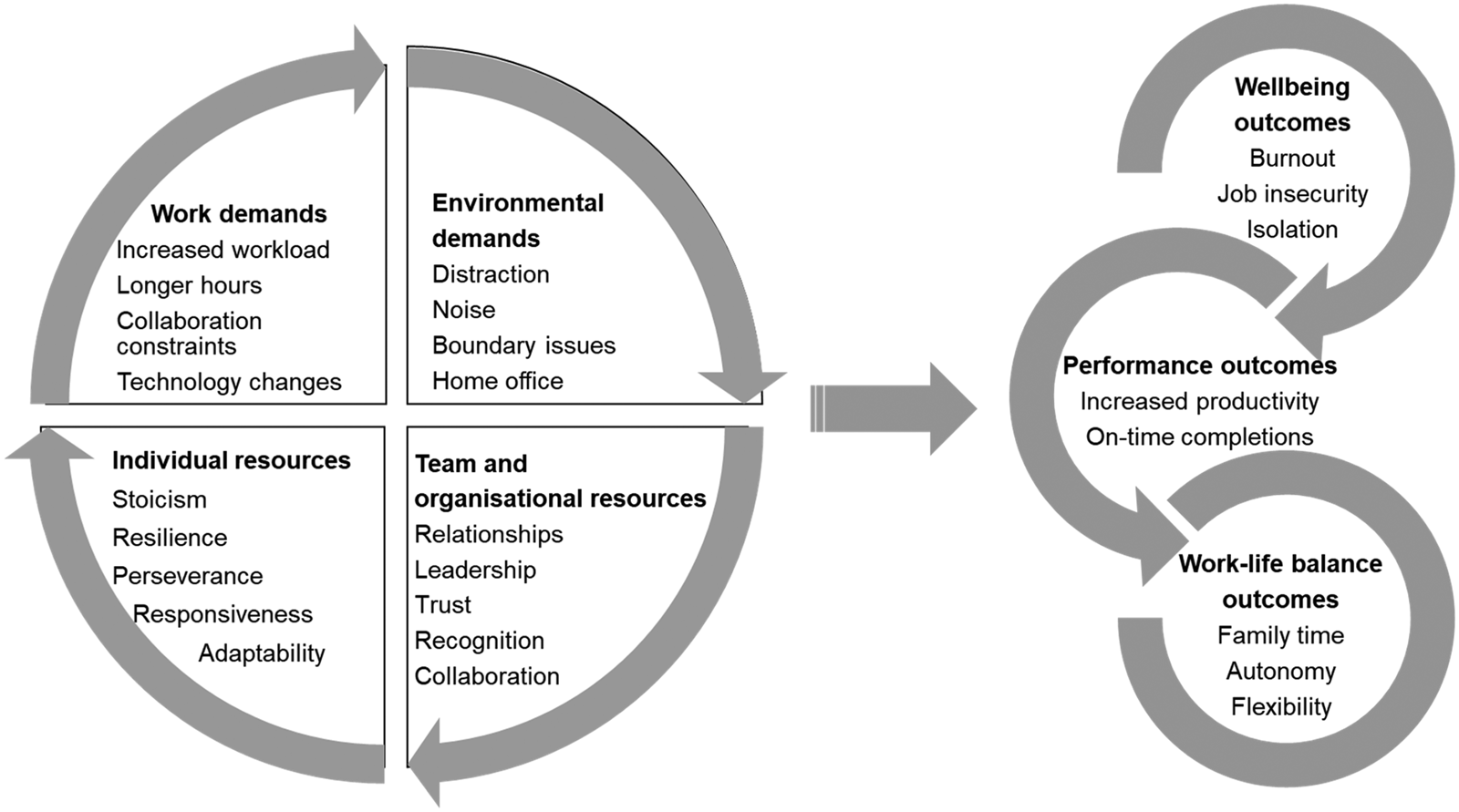

The five identified themes provided insight into the experience of flexible remote working. In regard to the impact of remote working on wellbeing (RQ3), further analysis revealed that these experiences can be understood in terms of work and environmental demands and available resources (Figure 1). The findings from this study suggest that in the context of remote flexible work demands, employees draw on available individual, team and organisational resources in an effort to maintain BAU productivity levels.

Fig. 1. Flexible remote work demands-resources model.

The experiences described by respondents demonstrated an ability to adapt to the new work environment, for example:

I was always a non-believer in working from home, but within a week I was converted to the view that the team could do so. (Manager, Interview E1)

In some cases, the experience created an opportunity for personal growth, with some employees and managers reporting that the experience led to a shift in their mindset about flexible remote work practices. For some their negative attitudes to flexible and remote working arrangements prior to the experience were challenged, and ultimately changed. This is exemplified by one manager (Interview E1) who said, ‘I was of the view that working from home wasn't effective, but now I've completely changed my view’, and an employee (Interview E4) who said, ‘I wasn't a fan for working from home pre then. I'm old school. But since then I've found working from home not too different’. Again, these findings align well with those from the diaries, showing these perceptions and experiences endured over time:

The office environment will change in the future. A lot of people reluctant to go back into work in the office. I probably will go back, but will work from home more than I have ever done so in the past. (Employee, Interview E4)

Overall, the findings show that, over time, team members adapted to the flexible work environment and valued the increased productivity it brought. These findings provide scope for HRM to consider work processes and policies that provide for longer-term integration of remote flexible work, and the implications of these processes and policies for the future flexible workspaces. Moreover, the findings suggest that the outcomes were influenced by how managers and employees balanced the work and environmental demands of flexible remote work, with the individual, team and organisational resources available to them.

Discussion

Utilising COR and the challenge–hindrance framework, this study revealed pivotal insights into the experiences of working from home as a result of the COVID-19 restrictions. In particular, it highlighted the influence of resources, both job and personal, on the way individuals managed remote work situations. COR's corollaries 2 and 3 are relevant to our findings, and further illustrate the association between resources and work experiences. Corollary 2 relates to resource ‘loss cycles’ whereby a loss of resources, for example, a lack of technological support, contributed to stress as well as perceived productivity loss. Corollary 3, on the contrary, concerns resource ‘gain spirals’. In such situations, a supportive manager or cohesive team can prompt effective communication and support further access to and exchange of helpful job resources. This research on forced flexibility during COVID-19 restrictions highlights the unique experiences of employees working in the resources sector, including the factors that supported and/or hindered wellbeing and productivity. In doing so, applies and extends COR theory and the challenge–hindrance framework. Since remote work is likely to become increasingly commonplace for organisations globally, our findings are likely to have ongoing relevance (Eddleston & Mulki, Reference Eddleston and Mulki2017; Ozimek, Reference Ozimek2020).

This study was undertaken during a pivotal period of the COVID-19 pandemic, where remote working was no longer a flexible option, but a business continuity requirement. As such, our findings reveal insights related to remote working, and virtual workspaces, beyond just a ‘nice to have’ flexible work option (Shockley & Allen, Reference Shockley and Allen2010). Our qualitative findings shed light on remote working experiences during a specific period of forced flexibility. This is an important contribution given remote work will continue for workplaces in the future, regardless of the pandemic.

The current study also identifies some of the risks and challenges of remote work to wellbeing and productivity, such as maintaining work–life balance and managing external distractions. Key resources in the form of support, relationships and effective technology, help to manage these challenges, and enable employees to work from home effectively and support wellbeing. In analysing and presenting the above findings, we applied COR theory and the challenge–hindrance framework to explore the role of resource gains and losses in enabling (or hindering) wellbeing and productivity.

In the diary study, employees reflected on their experience in terms of four aspects of the work system: the working environment, the work itself, the self and relationships. Analysis of their diary entries revealed five themes, all of which were raised in the subsequent CIT and interview study, where respondents also discussed the challenges associated with technology, work–life balance, the physical workspace (i.e., home office), workloads and team relationships. The interviews enabled a deeper discussion about the challenges experienced which provided insights into the impact of the changed working conditions due to COVID-19, and how these conditions impacted work–life balance, performance and employee wellbeing.

The themes and the accompanying illustrative quotes highlight some of the conditions whereupon mutual gains can be achieved between employees and the HRM function in the context of remote work (Whyman & Petrescu, Reference Whyman and Petrescu2014). In the first instance, the identification of environmental hazards (such as noise, distractions and ergonomics in home office set-up) were highlighted by respondents as having potential to significantly affect their work and wellbeing while working. Some respondents noted that their home set-up was much more conducive to work and wellbeing when compared to their office set-up. In such cases, the environment can be conceptualised through the lens of COR as a resource that acts to mitigate the emotional and physical strain and stress of work (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001). Notwithstanding, this mutual gain (where both the employee and organisation benefit) is contingent on the provision of an environment (and associated resources) that is conducive for work; and it is apparent from much of the data that some respondents in the sample did not have access to such an environment. For them, this poor(er) working environment led to resource loss, as they juggled competing commitments, distractions and other inhibitors to work which in turn made demands seem unmanageable, rather than positively challenging. At the same time, the data did track cases where employees themselves innovated and found workarounds, to buffer any resource loss and maintain/improve productivity.

This study shows that when employees contribute through innovations and workarounds, and HR contributes with appropriate support and resources for remote work, this mutual contribution supports mutual gain outcomes. As such, both parties are driven to achieve a productive work arrangement which is conducive to and considerate of employee wellbeing. In relation to the work–life balance and boundary management themes, the findings highlighted circumstances whereupon employees altered the time that they undertook work so as to fit in their caring responsibilities in a shared working space. However, this created tensions when, for example, they received a work-related call during this time. From a mutual gains and contributions perspective, while it is challenging to conceive of HR having provision to set circumscribed times for calls and meetings for each individual employee within a team so as not to violate a particular work–life boundary, it is apparent in the data that a new culture of trust and tolerance was ceded as a result of this event. This culture of trust and tolerance manifested itself across much of the team, and meant that employees felt safe to navigate their work-and-life conflicts as they arrived, and in concert with their team members. This shows a resource (nested within the social climate of the work team) that, when present, enabled mutual gains. Related to this, the administration of technological tools to aid connection and workflow was another enabling factor where mutual gains could be achieved. The importance of physical, psychological and social resources has been highlighted and supported in relation to employees' wellbeing in a study by Herttuala, Kokkinen, and Konu (Reference Herttuala, Kokkinen and Konu2020). Specifically, having access to different types of resources that can help employees address their work challenges has an impact on their wellbeing, while loss of resources or having access to fewer resources in the face of challenges is a serious threat to employees' wellbeing.

Indeed, the success of the enforced home working period as a business continuity effort was in large part a consequence of leaders' ability to adapt behaviours and practices to managing remote teams, the application of a higher trust and relationship-focused leadership approach, clear and effective communication practices and a culture of performance that gets the job done whatever adversity arises. Managers reported an increase in their workload due to COVID-19 because managers play a crucial role in the organisation and possess large amounts of responsibility including setting directions for their employees and communicating with them regarding the delivery of tasks (Salmela-Aro, Rantanen, Hyvonen, Tilleman, & Feldt, Reference Salmela-Aro, Rantanen, Hyvonen, Tilleman and Feldt2011). Support for new and untested technologies also mattered (Chen, Westman, & Eden, Reference Chen, Westman and Eden2009). Lessons from the case study could well benefit other organisations in preparation for any future disruptions or moves towards greater workforce flexibility.

Organisational support should also involve training for effective flexible working for both team leaders and team members. This could include key information on how best to lead remote teams, including the importance of demonstrative trust and appropriate ways to manage performance through goal setting and an outputs-based approach (see Cascio, Reference Cascio2000), remote communications with team members and stakeholders, managing team relationships and morale, setting boundaries during extended remote working periods and working as part of a virtual team. Although much of this was instinctively done very well by both managers and team members, adaptation took time and relied on the innovation and ‘bloody-mindedness’ of teams to get the job done.

Although remote working under COVID-19 conditions was relatively successful (often to the surprise of previously sceptical managers and team members), it is important to recognise things that did not work so well from a team and individual-level perspective. These include problems due to a lack of preparedness, sub-optimal working conditions in the home environment, increased workloads, poor boundary management between work and non-work-life and resistance to working remotely and in isolation from colleagues. The types of concerns raised in this study should be explored further with HRM promoting two-way discussions within teams and supporting the generation and implementation of appropriate solutions.

Finally, an important outcome to acknowledge is the change in attitudes towards remote working from many of the respondents to our study, managers included, that was brought about through the experience of achieving positive outcomes and improved work–life balance. Several respondents admitted to being highly sceptical of working from home arrangements for reasons of trust, performance, collaboration and distractions. Yet, participation in remote working, and the associated adaptation to ensure the maintenance of performance, brought about a change in attitude and a determination to work remotely at least part of the time in the future as part of a balanced, productive and healthy work-life. Sound HRM policy in this area is essential to ensure flexible workspaces provide the mutual gains sought by employees and employers now and into the post COVID-19 flexible workspace.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size. Another and related limitation is the confined research context, concentrated in the resources sector of Australia. Although this context provided a rich and unique insight into the resources and challenges available and provided in the resources sector, it does limit the representativeness and generalisability of the research.

Implications

Organisations ought to communicate future changes and requirements, as well as contingency plans, when it comes to remote work. COVID-19's forced flexibility meant that several organisations could not plan for an organisation-wide remote work strategy. This study's findings and insights can work to inform organisations and HR managers about employee (and manager) experiences of switching to remote work and the importance of adequate resourcing (including but not limited to planning and communication).

Organisations may also benefit from adapting a more inclusive approach by supporting all employees and considering employees' differing family circumstances (Kim & Mullins, Reference Kim and Mullins2016). This involves not only a recognition of individual differences, but also an awareness that such differences are respected and valued. Focusing on relationship-oriented HR systems, which consist of a relational perspective focused on building relationships between employees, may be beneficial to overcome negative consequences that sudden and unpredicted events such as COVID-19 pandemic can have on employees' wellbeing (Carnevale & Hatak, Reference Carnevale and Hatak2020; Kehoe & Collins, Reference Kehoe and Collins2017).

Organisations and their managers should not underestimate the importance of team relationships, dynamics, collaborative capacity and trust in supporting the effectiveness of remote working on organisations (Horwitz, Bravington, & Silvis, Reference Horwitz, Bravington and Silvis2006). Line managers are likely to be crucial in modelling flexible working (Sims & Manz, Reference Sims and Manz1982), and sharing the associated challenges they experience, which may further legitimise this form of working for employees and normalise the existence of challenges and demands that may require managerial or instrumental support to overcome. Furthermore, individual capacities matter too, such as adaptive mindsets, resilience and self-discipline, enabling innovative workarounds and adaptation to changing demands.

More specifically, HR departments should ensure capacity to review the effectiveness of flexible working practices and policies. This is critically important in evaluating the (im)balance in demands (i.e., workload and childcare) and resources (e.g., supervisor support and technology) associated with flexible working, and remote work in particular (ten Brummelhuis, Haar, & van der Lippe, Reference ten Brummelhuis, Haar and van der Lippe2010; ter Hoeven & van Zoonen, Reference ter Hoeven and van Zoonen2015). Rigorous review and evaluation will also help to inform the nature of support required to maintain wellbeing and productivity (Williams, Reference Williams2017). Desired support mechanisms are likely to vary depending on employee needs and circumstances, and other organisational and occupational characteristics (Lambert, Marler, & Gueutal, Reference Lambert, Marler and Gueutal2008). Review and evaluation of flexible and/or remote work practices need to be conducted in a long-term manner, giving work arrangements adequate time to mature.

Conclusion

This paper set out to explore the challenges associated with the work dynamic changes during and post-COVID-19, and to understand how remote working impacted the maintenance of wellbeing and productivity. It has concerned itself with a unique period in time but its findings have pointed not only to clear implications of the forced flexibility of remote work as a result of COVID-19, but also for these practices in the future.