WHY THE ETHICALITY OF ACCOUNTANTS IN SMALL ACCOUNTING FIRMS IS IMPORTANT

The ethicality of professional accountants is of concern for at least the following two reasons. First, the work of accountants can have direct ethical implications. For example, accountants have been suspected as a significant contributing factor underlying some of the recent corporate scandals (Dewing & Russell, Reference Dewing and Russell2003; Reinstein & McMillan, Reference Reinstein and McMillan2004; Brown, Reference Brown2005; Young, Reference Young2005) with researchers such as Clark, Dean, and Oliver (Reference Clark, Dean and Oliver2003) questioning the integrity of professional accountants working as auditors, executives and directors. Second, accountants are in a position to influence the behaviour of many other firms and individuals through the advice they provide or the audits they conduct. The influence of accountants on their clients is especially strong in the area of earnings management, an area where unethical practices have been noted, especially during the recent financial crisis, and an area of particular concern to standard-setters, regulators, and the accounting profession (Elias, Reference Elias2002).

The ethicality of accountants in small accounting firms is particularly important because the SMEs they typically service tend to rely heavily on their accountants for business advice. Carr, Cooper, Ferguson, Hellier, Jackling, and Wines (Reference Carr, Cooper, Ferguson, Hellier, Jackling and Wines2010) in a large-scale survey of accounting services in Australia report that public accountants provide a large range of professional services to their (mostly SME) clients, including accounting and tax compliance services, auditing and assurance, business planning and other management accounting services and referrals to providers of other types of services. In addition there is often a high level of trust, as Ian Ball, CEO of the International Federation of Accountants noted: ‘Accountants have a long-standing history as the trusted advisors for SMEs’ (Ball, Reference Ball2009). Such accountants tend to be located in small accounting firms.

To give some idea of the extent of the influence of accountants in small accounting firms, while they may be small (with, typically, <10 accountants per firm), there are many such firms. The last reliable figures we found were in a report from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (2003). Even then (at the end of June 2002) there were 9,860 accounting practices operating in Australia, employing 81,127 persons. Approximately 67% of these practices were small practices employing, on average, 3.5 people; including the proprietor or principal.

Questions about the ethicality of accountants, including those in small practices, take place in an environment where the nature of the accounting profession has moved from notions of social service to commercialised professionalism. Social service professionalism emphasises the public good nature of a service, while commercialised professionalism emphasises commercial issues such as efficiency and budget control. A more commercialised approach comes with demands for accountability. The ethicality of accounting firms is therefore subject to closer scrutiny (Hanlon 1977: 843–844, cited in Pierce, Reference Pierce2007); accountants need to behave and to be seen to behave in ethical ways in such an environment.

Finally, even discounting the influence of accountants on other firms, studying the ethicality of accountants in small accounting firms contributes important knowledge about the ethicality of SMEs in general, because such accountants represent a relatively large proportion of people working in the SME sector (Lee 1991: 193, cited in Pierce, Reference Pierce2007). As Hammann, Habisch, and Pechlaner (Reference Hammann, Habisch and Pechlaner2009) point out, the ethicality of SMEs in general is an area that has not received a great deal of attention in the literature, yet is important because SMEs play an important role in the economy.

EFFECTS OF EXPOSURE TO UNETHICAL PRACTICES ON THE PERSONAL ATTITUDES OF ACCOUNTANTS IN SMALL ACCOUNTING FIRMS

This paper uses a general measure of personal attitude of accountants towards practices of questionable ethicality as an indicator of the ethicality of the accountants. Details of the measure are presented in the Research Methods section below, but the measure is an average derived from attitudes towards a number of specific behaviours. Such a general attitude is likely to be an indicator of actual behaviour; if an individual has an attitude that is more accepting of practices with questionable ethicality in general, then they are more likely to engage in unethical practices. The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB, Ajzen, Reference Ajzen1985) provides some support for this line of thinking, although TPB is a model for predicting specific behaviours based on individuals’ attitude towards that specific behaviour.

There are likely to be many factors that affect personal attitude of accountants towards practices of questionable ethicality. For example, it is likely that personal attitude is a reflection of an individual’s values. It is also possible that environmental effects such as exposure affect personal attitudes. It is this latter effect that this paper explores.

Support for an effect of exposure on personal attitude comes indirectly from theories relating to the way peer pressure and norms affect behaviour. The work of psychologists such as Gigerenzer (Reference Gigerenzer2010) shows that heuristics such as the imitate-your-peers heuristic can be a powerful influence on moral behaviour. Similarly, the influence of social norms on behaviour has a long history in sociology (Hechter & Opp, Reference Hechter and Opp2001). Institutional Theory (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983) also is about the effect of peer pressure, albeit at the institutional level. As a reaction to peer pressure individuals may engage in unethical behaviour as an in-group member and doubtful business practices can be normalised and habitualised (Gino, Ayal, & Ariely, Reference Gino, Ayal and Ariely2009; Palazzo, Krings, & Hoffrage, Reference Palazzo, Krings and Hoffrage2012). Gino, Ayal, and Ariely (Reference Gino, Ayal and Ariely2009: 398) summed it up nicely as ‘dishonesty behaviour can be contagious’.

All of the above theories about the effects of peer pressure and norms deal primarily with the effects on specific behaviours (or processes and structures in the case of Institutional Theory). However, it is likely that such norms are reflected in indicators of behaviour such as the general measure of personal attitude used in this paper. That is, if people are exposed to unethical behaviours it is more likely that will develop a personal attitude that is more accepting of unethical practices. Accountants, in the course of their normal business, are likely to be exposed to such behaviours (Liyanarachchi & Adler, Reference Liyanarachchi and Adler2011).

There is a contrary argument regarding the effect of exposure. Researchers such as Schminke, Arnaud, and Kuenzi (Reference Schminke, Arnaud and Kuenzi2007) argue that exposure to moral dilemmas may be used in training to help individuals recognise the existence of moral issues (moral sensitivity) and develop the ability to follow through with the morally correct course of action (moral character). In the research reported in this paper no information was collected regarding the way exposure was subsequently handled in the firm; while it is likely that some exposure would be discussed and used in ethical training in the firm the majority would probably not. Therefore we expect that in the current research accountants who were exposed to more questionable events will be more accepting of ‘bad’ behaviour:

Hypothesis 1: Accountants in small accounting firms who are exposed to more events involving questionable ethics will also have a lower attitude towards behaving ethically (i.e., they will be more accepting of unethical behaviour).

The measure of exposure to practices of questionable ethicality used to test this hypothesis is explained in detail in the research method section below, but it was not simply the total number of events that the accountants had encountered. Instead, the measure of exposure was a measure of the breadth of exposure to events of different types, using a set of scenarios designed to cover a broad range of ‘bad’ practices.

Prior studies link variables other than exposure to personal attitude towards ethical behaviour, though many extend beyond mere attitude to actual behaviour. For example, Ede, Panigrahi, Stuart, and Calcich (Reference Ede, Panigrahi, Stuart and Calcich2000) found a positive relationship between age and ethical practices, but no relationship between sex and ethical behaviour. Serwinek (Reference Serwinek1992) examined the effects of several variables such as age, sex, marital status and education on ethics but only found age to be a significant predictive variable. Andreoli and Lefkowitz (Reference Andreoli and Lefkowitz2009) found that age, sex, and ethnicity were unrelated to personal misconduct or observed misconduct by others, but found that various organisational characteristics such as size and type and ethical climate were related to this type of misconduct. Ashkanasy, Falkus, and Callan (Reference Ashkanasy, Falkus and Callan2000) found various variables, such as the individual’s role and level within the organisation as well as organisational variables such as the extent to which the firm’s formal code of conduct is used in the organisation, were related to ethical tolerance. However, many of these variables are not important for accountants in small accounting firms. In particular, since accountants in small firms are often an owner or partner, a variable such as individual’s role and level within the organisation is irrelevant. For a similar reason organisational variables such as ethical climate or the extent to which the firm’s formal code of conduct is used are less relevant in this study because they are under the control of the owners/partners themselves. In this current study, size is also not important because all the firms are small. Therefore, only Age and Sex are included. These are included only as control variables; we make no specific hypotheses regarding these variables. The path diagram shown in Figure 1 summarises the research hypothesis and includes the two control variables.

Figure 1 Path diagram indicating relationships among variables

Research Method

Participants

The research involved the administration of two survey questionnaires to small accounting firms in 2007 and 2008. The list of ‘Auditors or Accountants small business’ in the Australian Yellow Pages was used to identify potential participants for the 2007 survey. The list did not include new businesses less than 3 years old. Closed businesses may have been included. A total of 2171 survey questionnaires were mailed along with a covering letter outlining the aims of the study and guaranteeing its confidential nature. The letters were specifically addressed to the owner or the principal partner in the firm. Participation in the study was voluntary, and neither individual respondents nor their firms could be identified. Some businesses were no longer operating, and some contact details were out of date. As a result, 321 unopened letters were returned, leaving 1850 firms that were contacted. Return of the completed survey questionnaire was taken as consent. A total of 265 useable responses were obtained (14.3%).

For the 2008 survey, 2000 addresses were selected at random from the list of businesses in the Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification (ANZSIC) category 7842 (Accounting Services) on the Australia on Disc Business edition 2008, excluding businesses in the top 100 list of accounting firms published by Business Review Weekly. Eighteen business addresses were duplicated and 409 of the mailed questionnaires were returned ‘return to sender’. A total of 259 usable responses were obtained from the remaining 1573 questionnaires (16.5%).

Scales employed in the study

In this paper the measures of exposure to and personal attitude about practices of questionable ethicality were derived using a set of short vignettes that each described a practice of questionable ethicality. These items were sourced from survey questionnaires developed by Longenecker, McKinney, and Moore (Reference Longenecker, McKinney and Moore1989), Longenecker, Moore, Petty, Palich, and McKinney (Reference Longenecker, Moore, Petty, Palich and McKinney2006), Hornsby, Kuratko, Naffziger, LaFollette, and Hodgetts (Reference Hornsby, Kuratko, Naffziger, LaFollette and Hodgetts1994) and Wu (Reference Wu2002). A total of 16 vignettes were originally sourced, but during evaluation by a panel of knowledgeable individuals (faculty members who teach business ethics) the panel determined that only 13 were needed to cover the range of practices relevant for accountants in small accounting firms. These 13 vignettes are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Items describing behaviours of questionable ethicality

In the 2007 questionnaire respondents were asked to rate their acceptance of each these 13 scenarios on a 5-point Likert scale from 1=very unacceptable to 5=very acceptable with 3=neutral. In the 2008 questionnaire respondents responded on a slightly different (7-point) scale with 1=never acceptable to 7=always acceptable and no clear neutral value. The lack of a clear neutral value in the 2008 data made the scales difficult to compare, so we were unable to combine the data for the 2 years for analysis. We therefore tested our research hypothesis using the 2007 data and the 2008 separately.

For both sets of data, a score for ‘Personal attitude towards questionable ethical behaviour’ was obtained by reverse-coding the scores and computing the mean of the 13 scores for each individual participant. The score was out of 5 for 2007 and out of 7 for 2008. In both cases a higher score indicated a ‘better’ personal attitude towards behaving ethically; a lower score indicated an attitude that is more accepting of unethical practices.

The measure of exposure to practices of questionable ethicality was determined as follows. For each of the 13 items in Table 1, participants were asked whether they had or had not observed the type of practice described (0=No, 1=Yes). The total number of ‘yes’ responses (out of 13) was used as a measure of each individual’s exposure. Thus the measure of exposure is a measure of the breadth of practices encountered, rather than a measure of the total amount of exposure. A low score indicated that the respondent had encountered only a small number of different types of ‘bad’ practices; a higher score indicated exposure to a broader range of such practices.

RESULTS

Table 2 presents descriptive summaries of the data.

Table 2 Descriptive statistics for variables in the study

In both 2007 and 2008 the average age of the respondents was over 40, which makes it likely that most respondents had sufficient work and life experiences to relate to the ethical questions asked in the survey questionnaire. It also appears that the respondents did not have extensive exposure to questionable ethical behaviour, with a mean score of 5.2 out of a possible maximum of 13 in 2007 and a mean of only 3.4 of out 13 in 2008.

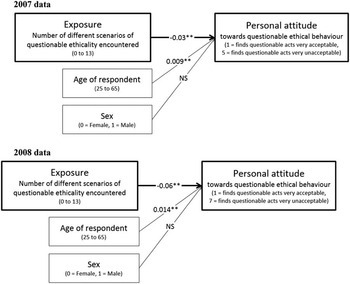

The results from the regressions used to investigate the model shown in Figure 1 is summarised in the path diagrams in Figure 2. The path coefficients are the unstandardised (b) regression coefficients. The level of significance is indicated as: ns=Not significant, significant *p <0.05, **p<0.01.

Figure 2 Path diagrams summarising regression results

DISCUSSION, LIMITATIONS, AND CONCLUSION

Figure 2 shows that, as hypothesised, exposure to a broader range of practices of questionable ethicality is significantly negatively related to personal attitude towards questionable ethical behaviour. This result is found in both years. That is, the findings indicate that if an accountant in a small accounting firm is exposed to a broader range of practices of questionable ethicality, then they also tend to have an attitude that finds such practices more acceptable. It seems that Gino, Ayal, and Ariely’s (Reference Gino, Ayal and Ariely2009: 398) summary ‘dishonest behaviour can be contagious’ quoted previously may apply also to accountants in small accounting firms.

Sex was not a significant predictor of ‘Personal attitude towards questionable ethical behaviour’, suggesting that both sexes hold similar attitudes towards questionable ethical behaviour. The age of respondents is positively related to personal attitudes towards questionable ethical behaviour (b=0.009 in 2007, b=0.014 in 2008, p<0.01 in both years), suggesting that, perhaps, older people tend to develop an attitude that is less accepting of unethical behaviour.

It is important to note that in this study the exposure variable is a measure of the breadth of exposure, not a measure of total exposure. For example, it is possible that a respondent who had been exposed to a ‘padding expense account’ scenario (item 1 in Table 1) had actually been exposed to that practice many times. Presumably more exposure like this would serve to enhance any peer-pressure or norm effect. Further research is indicated.

It is also likely that more precise information about the nature of any exposure is important. For example Gino, Ayal, and Ariely (Reference Gino, Ayal and Ariely2009) demonstrate that respondents may react differently to observed bad practices depending whether the practices occurred within their peer group – possibly other accountants – or by outsiders. Gino, Ayal, and Ariely (Reference Gino, Ayal and Ariely2009) also demonstrate that saliency of dishonestly affects subsequent reactions. Further research is needed to incorporate such nuances into the research model investigated in this current research.

The current research could be extended to incorporate information about how any exposure was handled within the firm to take into account the use of the exposure in a constructive way, such as in training as suggested previously (Schminke, Arnaud, & Kuenzi, Reference Schminke, Arnaud and Kuenzi2007).

Further research is needed to assess how personal attitudes of individual accountants might actually be reflected in behaviour in the firm. For example, while an individual owner/partner of a small accounting firm may personally have an attitude that is more accepting of unethical practices, the actions they take in the firm level may be less tolerant; it is possible that exposure to unethical practices will encourage an owner/partner to put in place policies and trainings to strengthen ethical behaviour across the firm, in an attempt to protect the firm.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from CPA Australia in 2007. The authors are grateful for the contribution made by Dr. Connie Zheng towards the first draft of the paper. Authors acknowledge the contribution made by participants of the Eighteenth Annual International Conference Promoting Business Ethics at the Manhattan campus of St. John’s University, 2011.