INTRODUCTION

The 20th century was dominated by organizational entries into new markets, with multinationals changing the very face of global business. The 21st century instead appears to be encouraging a truly global village, in which few countries or businesses are isolated from international influences. Cross-cultural studies in turn can facilitate greater understanding among societies, and global managers can use them to evaluate new markets, design business strategies, and devise management practices. For employees, job seekers, and migrant workers, such studies offer a first step toward understanding the practices and values of other societies, as well as of multinationals that may have entered their domestic markets. Some of the earliest cross-cultural literature dates back to McClelland (Reference McClelland1961) and Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck (Reference Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck1961) in the social sciences; since then, it has featured landmark studies by Hall (Reference Hall1959, Reference Hall1960), Hofstede (Reference Hofstede1980, Reference Hofstede1991), Laurent (Reference Laurent1983), Trompenaars (Reference Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner1993; also see Smith, Dugan, & Trompenaars, Reference Smith, Dugan and Trompenaars1996; Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, Reference Tsang1997), Schwartz (Reference Schwartz1994), and House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, and Gupta (Reference House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman and Gupta2004).

In acknowledging how cultural dimensions might inform management practices in the 21st century (e.g., Cooke, Veen, & Wood, Reference Cooke, Veen and Wood2016; Farndale & Sanders, Reference Farndale and Sanders2016; Devinney & Hohberger, Reference Devinney and Hohberger2017), this article aims to expand understanding and illustrate the further use of cross-cultural studies, focused on the national culture and business environment of Pakistan, by revisiting and adding to the GLOBE study. The role of Pakistan and Pakistani workers in the global economy is considerable. Pakistan’s 2016 estimated gross domestic product (GDP) is $988.2 billion, ranking it 26 out of 230 countries (World Factbook, 2017a). The sixth most populated country in the world, it hosts a population of 188.02 million, and the Labour Force Survey estimates a working population of 59.7 million (Economic Survey, 2015). In recent years, Pakistan has made noteworthy economic growth (Reuters, 2016; World Bank, 2016a), and it has significant future potential for growth too (World Bank, 2016a; Cowen, Reference Cowen2017). Investments related to the one-belt-one-road and China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) initiatives are likely to make Pakistan a hub of economic activity among China, Central Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and beyond (Siddique, Reference Siddique2014; The Wall Street Journal, Reference Tosi and Greckhamer2015; Jamal, Reference Jamal2016; Kiani, Reference Kiani2016; World Bank, 2016a). That is, beyond Pakistan’s strong historical trade relations with the European Union, China, United Arab Emirates, United States, Saudi Arabia, India, Malaysia, Kuwait, Afghanistan, United Kingdom, and Germany (Economic Survey, 2015; World Factbook, 2017b), it is likely to expand its trade relations in breadth and depth.

To develop an understanding of the complexities of the culture and human resource (HR) management in Pakistan, this research extends the framework of the GLOBE study of cultural practices and values (House et al., Reference House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman and Gupta2004) to include Pakistan, which was not a participant in the original GLOBE project. We conduct a primary data analysis of the responses of 152 middle managers from Pakistan, together with secondary GLOBE data from 17,370 middle managers across 61 societies (House et al., Reference House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman and Gupta2004). The aim is to determine Pakistan’s score on the nine cultural dimensions of GLOBE, for use by further research, as well as to examine the impact of these cultural dimensions on HR practices in Pakistan. We also hope to encourage scholarly interest in cross-cultural management in Pakistan. The study offers a theoretically robust, practically useful overview of Pakistan for businesses operating in or planning to start trade relations with that country, as well as for those with employment relations with Pakistani individuals, expatriates, and potential expatriates.

GLOBE, CROSS-CULTURAL STUDIES, AND MANAGEMENT PRACTICES

Cross-cultural studies help enhance international understanding, encourage collaboration, and improve communication. In a recent retrospective article pertaining to culture, Kirkman, Lowe, and Gibson (Reference Kirkman, Lowe and Gibson2017) argue that revisiting conceptualizations of culture is helpful, not only to remind ourselves of the focus of cultural definitions and measurement but also to expand research beyond commonly studied cultural dimensions (Devinney & Hohberger, Reference Devinney and Hohberger2017).

The GLOBE project, published first in 2004 (House et al., Reference House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman and Gupta2004), offers a comprehensive picture of national cultures. Based on quantitative and qualitative research, this project measured nine major attributes of culture: performance orientation, in-group collectivism, institutional collectivism, gender egalitarianism, assertiveness, future orientation, power distance, humane orientation, and uncertainty avoidance. Several dimensions had been proposed or measured in previous studies; some of the most noted contributions were by Hofstede (Reference Hofstede1980, Reference Hofstede1991, Reference Hofstede2001), Schwartz (Reference Schwartz1994), Triandis (Reference Trompenaars1995), and Trompenaars (Reference Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner1993). In turn, various studies have debated (Jackson, Reference Jackson, Schuler and Werner2003; Aycan, Reference Aycan2005; Cooke, Veen, & Wood, Reference Cooke, Veen and Wood2016; Farndale & Sanders, Reference Farndale and Sanders2016) and repeatedly confirmed (Chiang, Reference Chiang2005; Pudelko, Reference Pudelko2005; Wilkinson, Eberhardt, McKaren, & Millington, Reference Wilkinson, Eberhardt, McKaren and Millington2005; Jackson, Schuler, & Werner, Reference Jackson2009; Chiang & Birtch, Reference Chiang and Birtch2010; Ollo-López, Bayo-Moriones, & Larraza-Kintana, Reference Ollo-López, Bayo-Moriones and Larraza-Kintana2011; Andreassi & Lawter, Reference Andreassi and Lawter2014; Festing & Knappert, Reference Festing and Knappert2014; Yahiaoui, Reference Yahiaoui2014; Donate, Pena, & Sanchez de Pablo, Reference Donate, Pena and Sanchez de Pablo2015) the influence of broad national characteristics on HR practices. A growing number of studies use the GLOBE dimensions, citing their theoretical comprehensiveness and methodological rigor (Javidan, Dorfman, Sully de Luque, & House, Reference Javidan, Dorfman, Sully De Luque and House2006). We accordingly rely on the GLOBE study’s proposed cultural dimensions for the foundation of this study. We provide a thorough description, which offers a fresh focus on these dimensions, and also analyze prior literature to detail the evidence regarding how these dimensions affect various management practices.

The cultural dimension performance orientation reflects the extent to which a community encourages and rewards innovation, high standards, and performance improvement (Javidan, Reference Javidan2004). Performance orientation influences management practices, because societies with a higher performance orientation recruit and select employees on the basis of their education, prior experience, personality traits, and cognitive skills. In comparison, societies with a lower performance orientation employ softer criteria, such as social and interpersonal skills, social class, or age (Aycan, Reference Aycan2005; Rao, Reference Rao2009). Training and development also appear more valued in high performance orientation societies, with training based on the person’s past and desired future performance (Tsang, Reference Tsui, Wang and Xin1994; Wilkins, Reference Wilkins2001; Javidan, Reference Javidan2004). These societies emphasize results rather than people, set demanding targets, highlight results in performance appraisals, reward performance with individual financial bonuses, and consider feedback necessary for improvement (Javidan, Reference Javidan2004; Carr & Pudelko, Reference Carr and Pudelko2006).

Collectivism, one of the most researched and complex cultural dimensions (Earley & Gibson, Reference Earley and Gibson1998; Gelfand, Bhawuk, Nishi, & Bechtold, Reference Gelfand, Bhawuk, Nishi and Bechtold2004), has appeared in many past studies (Kluckhohn & Strodtbeck, Reference Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck1961; Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1980; Trompenaars, Reference Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner1993; Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1994; Triandis, Reference Trompenaars1995). On the basis of its research, the GLOBE study divided collectivism into institutional collectivism and in-group collectivism. Institutional collectivism is the degree to which organizational and societal institutional practices encourage and reward collective distributions of resources and collective action; in-group collectivism is the degree to which individuals express pride in, loyalty to, and cohesiveness with their organizations, groups, and families (Javidan, House, & Dorfman, Reference Javidan, House and Dorfman2004). Scholars identify differences across societies marked by collectivism versus individualism with regard to many facets of the organization. For example, research has examined the impact of collectivism on recruitment and selection (Sinha, Reference Sinha1997; Herrera, Duncan, Green, Ree, & Skaggs, Reference Herrera, Duncan, Green, Ree and Skaggs2011; Manroop, Boekhorst, & Harrison, Reference Manroop, Boekhorst and Harrison2013; Cooke, Veen, & Wood, Reference Cooke, Veen and Wood2016), promotion (Aycan, Reference Aycan2005; Sekiguchi, Reference Sekiguchi2006), performance appraisals (Amba-Rao, Petrik, Gupta, & Von der Embse, Reference Amba-Rao, Petrik, Gupta and Von der Embse2000; Aycan, Reference Aycan2005; Varma, Pichler, & Srinivas, 2005; Chiang & Birtch, Reference Chiang and Birtch2010, Reference Chiang and Birtch2011; Yahiaoui, Reference Yahiaoui2014; Hossain, Abdullah, & Farhana, Reference Hossain, Abdullah and Farhana2015), compensation (Gomez-Mejia & Welbourne, Reference Gomez-Mejia and Welbourne1991; Luis & Mejia, Reference Luis and Mejia1991; Schuler & Rogovsky, Reference Schuler and Rogovsky1998; Aycan, Kanungo, & Sinha, Reference Aycan, Kanungo and Sinha1999; Chiang, Reference Chiang2005; Yeganeh & Su, Reference Yeganeh and Su2011; Yahiaoui, Reference Yahiaoui2014), teamwork (Chen, Zhang, Zhang, & Xu, Reference Chen, Zhang, Zhang and Xu2016), and CEO or top manager pay (Tosi & Greckhamer, Reference Triandis2004; Pudelko, Reference Pudelko2005). Although institutional and in-group collectivism are rarely studied as separate dimensions, developing a better understanding of the notion of collectivism remains important for determining successful management practices across societies.

A fourth dimension, gender egalitarianism, entails the degree to which the collective minimizes gender inequality (Emrich, Denmark, & Hartog, Reference Emrich, Denmark and Hartog2004). This dimension suggests some overlap with Hofstede’s (Reference Hofstede1980) masculinity dimension, which considered two aspects: the extent to which a society appreciates masculine values, such as assertiveness and competition, and the differences in the degree to which either gender exhibits such behavior. In the GLOBE study, gender egalitarianism instead measures the equality of treatment of persons of both genders. For organizations, this dimension can indicate whether men and women achieve equal representation in organizations across all levels (Javidan, House, & Dorfman, Reference Javidan, House and Dorfman2004). Whereas the cultural dimension of gender egalitarianism has received limited attention in management research, society’s appreciation for aggressive or caring behavior, associated more with the assertiveness dimension, has received more attention.

This assertiveness dimension reflects the degree to which people are assertive, confrontational, and aggressive in relationships with others (Javidan, House, & Dorfman, Reference Javidan, House and Dorfman2004). According to Hartog (Reference Hartog2004), an assertive society values competition, tough behavior, success, and progress. Such societies believe in a just world and stress equity, competition, and performance. Non-assertive societies instead value modesty, tenderness, and cooperation, whereas competition is associated with defeat and punishment. Trust derives from predictability; there is a greater emphasis on loyalty and integrity. Tradition, seniority, and experience are important. Communications with others involve ambiguity and subtlety, mainly to save face. In HR research since the GLOBE project, this assertiveness orientation has been found to influence recruitment and selection (Pudelko, Reference Pudelko2005; Leat & El-Kot, Reference Leat and El-Kot2007; Chiang & Birtch, Reference Chiang and Birtch2010, Reference Chiang and Birtch2011), interactions, ratings given in appraisals (Chiang & Birtch, Reference Chiang and Birtch2010), reward preferences (Leat & El-Kot, Reference Leat and El-Kot2007), and communication styles (Ollo-López, Bayo-Moriones, & Larraza-Kintana, Reference Ollo-López, Bayo-Moriones and Larraza-Kintana2011; Silva, Roque, & Caetano, Reference Silva, Roque and Caetano2015).

The future orientation culture dimension refers to the extent to which people engage in more future-oriented behaviors, such as delaying gratification, planning, and investing in the future (Javidan, House, & Dorfman, Reference Javidan, House and Dorfman2004). Generally speaking, cultures with high future orientations have the desire and capability to identify goals for the future and plan in a systematic and disciplined fashion to achieve those future aspirations. They also tend to have the discipline and self-control required for planning and execution, but this trait implies that they may neglect existing personal and social relationships. In contrast, cultures with low future orientations prefer to enjoy the present. They may not devote much attention to designing or executing plans for the future or reflecting on how their current behavior will influence their future (Keough, Zimbardo, & Boyd, Reference Keough, Zimbardo and Boyd1999; Ashkanasy, Gupta, Mayfield, & Trevor-Roberts, Reference Ashkanasy, Gupta, Mayfield and Trevor-Roberts2004). Thus, a high future orientation has positive consequences for project preparation, training, and development initiatives (Tsui, Wang, & Xin, 2006; Liu, Li, Zhu, Cai, & Wang, Reference Liu, Li, Zhu, Cai and Wang2014).

Another cultural dimension of the GLOBE study is power distance, or the degree to which members of a collective expect power to be distributed equally in a society (Javidan, House, & Dorfman, Reference Javidan, House and Dorfman2004). The concept of power distance also exists in other studies (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1980; Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1994). As noted for collectivism, extant research indicates differences in the effectiveness of HR practices according to power distance levels. For example, processes such as 360° feedback or general employee feedback are less appealing or effective in high power distance societies, because by nature, these methods require more participation across hierarchal levels (Davis, Reference Davis1998; Fletcher & Perry, Reference Fletcher and Perry2001; Kazlauskaite & Buciuniene, Reference Kazlauskaite and Buciuniene2010; Ollo-López, Bayo-Moriones, & Larraza-Kintana, Reference Ollo-López, Bayo-Moriones and Larraza-Kintana2011; Sartorius, Merino, & Carmichael, Reference Sartorius, Merino and Carmichael2011; Zhang & Begley, Reference Zhang and Begley2011; Singh, Mohamed, & Darwish, Reference Singh, Mohamed and Darwish2013; Chen, Zhang, & Wang, Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014; Jiang, Colakoglu, Lepak, Blasi, & Kruse, Reference Jiang, Colakoglu, Lepak, Blasi and Kruse2014), seeking feedback from subordinates may appear to undermine a supervisor’s authority (Gregersen, Hite, & Black, Reference Gregersen, Hite and Black1996; Silva, Roque, & Caetano, Reference Silva, Roque and Caetano2015), and appeal processes may seem unsuitable because they challenge authority (Fletcher & Perry, Reference Fletcher and Perry2001). Power distance also influences the design of training (Wang, Wang, Ruona, & Rojewski, Reference Wang, Wang, Ruona and Rojewski2005; Festing & Barzantny, Reference Festing and Barzantny2008; Fu & Kamenou, Reference Fu and Kamenou2011; Ollo-López, Bayo-Moriones, & Larraza-Kintana, Reference Ollo-López, Bayo-Moriones and Larraza-Kintana2011), compensation, appraisals (Schuler & Rogovsky, Reference Schuler and Rogovsky1998; Chow, Lo, Sha, & Hong, Reference Chow, Lo, Sha and Hong2006; Singh, Mohamed, & Darwish, Reference Singh, Mohamed and Darwish2013; Festing & Knappert, Reference Festing and Knappert2014), communication (Chen, Zhang, & Wang, Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014; Yang, Zhou, & Zhang, Reference Yang, Zhou and Zhang2015), and career development (Aycan & Fikret-Pasa, Reference Aycan and Fikret-Pasa2003; Chow, Lo, Sha, & Hong, Reference Chow, Lo, Sha and Hong2006; Festing & Barzantny, Reference Festing and Barzantny2008; Fu & Kamenou, Reference Fu and Kamenou2011) initiatives.

Humane orientation is the degree to which a society encourages and rewards people for being fair, altruistic, generous, caring, and kind to others (Javidan, House, & Dorfman, Reference Javidan, House and Dorfman2004). In humane-oriented societies, the focus on others, including family, friends, community, and strangers, is more important than on the self. Values of altruism, benevolence, kindness, love, and generosity have higher priority, and needs to belong and affiliate motivate people (Kabasakal & Bodur, Reference Kabasakal and Bodur2004). Management literature has paid limited attention to this cultural dimension.

The final dimension, uncertainty avoidance, is the extent to which a society, organization, or group relies on social norms, rules, and procedures to alleviate the unpredictability of future events (Javidan, House, & Dorfman, Reference Javidan, House and Dorfman2004). Sully de Luque and Javidan (Reference Sully de Luque and Javidan2004) describe uncertainty avoidance at three levels: at the individual level, it indicates tolerance for ambiguity, extraversion, flexibility, and independence. It therefore promotes feedback-seeking from superiors, peers, and subordinates, as well as questions and observations (Sully de Luque & Sommer, Reference Sully de Luque and Sommer2000). At the organizational level, greater uncertainty avoidance results in more feedback and preparation, as well as more planned and controlled innovation. Finally, at the national level, seniority-based, rather than performance-based, compensation systems tend to be more prevalent in countries marked by high uncertainty avoidance (Schuler & Rogovsky, Reference Schuler and Rogovsky1998; Chiang, Reference Chiang2005; Lertxundi & Landeta, Reference Lertxundi and Landeta2011). High uncertainty avoidance societies also often offer childcare assistance and career break schemes (Schuler & Rogovsky, Reference Schuler and Rogovsky1998).

Assessed one dimension at a time, these dimensions provide insight into cultures when considered separately. However, for a more comprehensive picture of a particular culture, the scores on practices (and values) for all nine dimensions should be considered together. It is also important to consider how the cultural values and practices of the nine dimensions may correlate. For example, societies in the GLOBE sample that value preparing for the future tend to value performance, as indicated by the positive correlation (0.41, p<.05) between future orientation values and performance orientation values at the societal level (Ashkanasy et al., Reference Ashkanasy, Gupta, Mayfield and Trevor-Roberts2004). Societies in the GLOBE sample that score lower on assertiveness practices also tend to score higher on humane orientation practices, exhibited in the negative correlation (–0.42, p<.05) between assertiveness practices and humane orientation practices at the societal level (Hartog, Reference Hartog2004). Thus each society presents unique challenges and opportunities, based on a combination of cultural dimensions.

In turn, studies of management practices often show that operating businesses in, for example, China differs from operating businesses in the United States, the Netherlands, or other Western societies (Xu Lu, Reference Xu Lu2003; Wang, Wang, Ruona, & Rojewski, Reference Wang, Wang, Ruona and Rojewski2005; Wilkinson et al., Reference Wilkinson, Eberhardt, McKaren and Millington2005; Tsui, Wang, & Xin, 2006; Fu & Kamenou, Reference Fu and Kamenou2011; Chen, Zhang, & Wang, Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Li, Zhu, Cai and Wang2014; Yang, Zhou, & Zhang, Reference Yang, Zhou and Zhang2015). India also offers cultural challenges entirely unique from those of China or Anglo-Saxon countries (Sinha, Reference Sinha1997; Amba-Rao et al., Reference Amba-Rao, Petrik, Gupta and Von der Embse2000; Varma, Pichler, & Srinivas, 2005; Singh, Mohamed, & Darwish, Reference Singh, Mohamed and Darwish2013). Furthermore, United States, German, and French organizations vary in their practices (Festing & Barzantny, Reference Festing and Barzantny2008; Festing & Knappert, Reference Festing and Knappert2014; Yahiaoui, Reference Yahiaoui2014), as do Canadian and South Korean (Dastmalchian, Lee, & Ng, Reference Dastmalchian, Lee and Ng2000), Egyptian (Leat & El-Kot, Reference Leat and El-Kot2007), and Turkish (Aycan & Fikret-Pasa, Reference Aycan and Fikret-Pasa2003) groups. Together, growing research on wider ranges of countries and broader dimensions offers cross-cultural insights that are more complex than early conceptualizations provided. With this research project, we extend this effort further, into Pakistan, by assessing its society according to GLOBE’s cultural dimensions.

METHODOLOGY

Measures

The GLOBE questionnaire contains ~190 complex questions about opinions and values, and focuses on nine major attributes of culture and six global leadership competencies; the current study centers on the cultural dimensions (GLOBE, 2016). The cultural dimension survey questions consist of two sections: how cultural practices are perceived by each respondent (as is) and how each respondent desires these practices to be (should be). The former are labeled cultural practices; the latter are labeled cultural values. Furthermore, the study measures these cultural practices and values for both the society and the organization through two closely linked questionnaires. Thus each cultural dimension comprises four types of questions: organizational practices (as is), organizational values (should be), societal practices (as is), and societal values (should be). In the original GLOBE study, half the respondents from each country complete the questionnaire for organizational practices and values, and the other half complete the one for societal practices and values (Hanges & Dickson, Reference Hanges and Dickson2004); the same practice was followed in Pakistan.

Each of the four areas comprise of 34–41 items that measure the nine cultural dimensions. The range of items for each cultural dimension varies from 3 to 6. All items use 7-point measurement scales, whose output labels vary according to the items. Further methodological information, including details about the scale development, construct specification, dimension specification, item generation, item review, and pilot testing of the questionnaire, is available in Hanges and Dickson (Reference Hanges and Dickson2004). The questionnaires used by both the original and current study can be downloaded from the GLOBE website (GLOBE, 2016).

Participants and procedure

In the original GLOBE study, the number of respondents per country ranged from 27 to 1,790 (Hanges & Dickson, Reference Hanges and Dickson2004). A member of the original GLOBE team who led the statistical analyses for the project recommended a preferred sample of 150 per country. Thus, for our investigation of Pakistan, our target was 150 respondents. In accordance with the Phase 2 criteria of the GLOBE study, middle managers representing local organizations (i.e., not multinationals) working in the food processing, financial services, and telecommunication services industries participated. The selection of these three industries reflected the belief that they should be present in almost all countries, and they systematically differ enough from one another to create an overall sample of dynamic, traditional, and high-technology organizations (Brodbeck, Hanges, Dickson, Gupta, & Dorfman, Reference Brodbeck, Hanges, Dickson, Gupta and Dorfman2004). Sub-cultures certainly exist within countries; the data in Pakistan predominantly were collected from multiple large cities in the province of Punjab (most highly populated province), with some surveys completed in organizations in southern Khyber Paktunkhua, to ensure that some variation in sub-cultures is covered.

The national language of Pakistan is Urdu, but the official language, in which most of the business is conducted, is English. All higher education is also in English. Considering the target respondent group of middle managers, this study uses English-language questionnaires. However, because of the length and complexity of the questions, each survey was completed as a structured interview or in the presence of a trained researcher. The respondents completed the questionnaire, and the researchers kept a copy of an Urdu version with them to ensure that respondents could easily understand the key concepts. Each questionnaire took an average of 90 minutes to complete. The achieved sample size is 152. In total, 85% of the sample was male, and the average age of the respondents was 34.5 years (SD=10.5 years).

To create an understanding of Pakistani culture, this investigation calculated composite scales for each cultural dimension (3–6 items each) for Pakistan using GLOBE procedures (GLOBE, 2016). Then, mean scores for all nine cultural practices scores were calculated. As discussed, the exploration of each cultural dimension relied on four sets of questions (Figure 1). Scores for Pakistani practices (as is) and values (should be) were then compared with the respective scores of the 61 other societies. The gap between Pakistani practices and values was assessed at organizational and societal levels, which also indicated the gap between Pakistani organizational and societal practices and values.

Figure 1 Four categories of questions for each cultural dimension

RESULTS

Understanding Pakistani culture

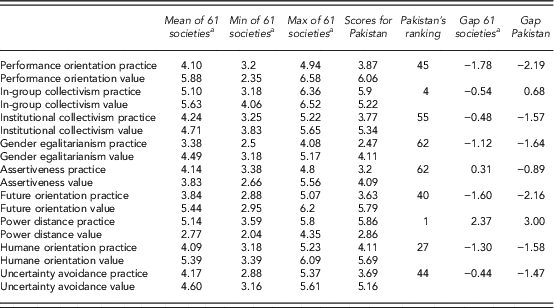

Table 1 summarizes the mean scores for all nine societal cultural practices and values of Pakistan and the 61 GLOBE societies. It also ranks Pakistan’s mean scores, which provides an analysis of the gap between its practices and values. Because the unit of analysis is each country, the min–max appears only for the 61 society data set; Pakistan appears as an additional case for comparison. Table 2 summarizes the mean scores for the societal and organizational practices and values of Pakistan and the gaps among them. The results pertaining to societal and organizational practices and values are discussed in detail subsequently.

Table 1 Comparison of societal cultural practices and values: Pakistan versus GLOBE

Notes: Higher scores indicate greater performance orientation, future orientation, assertiveness, collectivism, power distance, humane orientation, and uncertainty avoidance. Lower scores indicate greater male domination for gender egalitarianism.

a Analysis of the original GLOBE data set, courtesy of the GLOBE team.

Table 2 Comparison of Pakistani societal and organizational mean scores

a Cultural dimensions for which the gap between societal and organizational scores is greater than 1 appear in bold.

Performance orientation

The GLOBE performance orientation society practice score reaches an average rating of 4.10, with a range of 3.20–4.94 on the 1–7 scale. The society value scores average 5.88, with a range of 2.35–6.58 (Table 1). Pakistan, with its performance orientation practice score of 3.87 (Table 1), has a ranking of 45 among 62 countries (Table 1). Thus its current practices locate it at a medium to low level with regard to its focus on performance orientation. The performance orientation value score of 6.06 indicates a gap equal to 2.19 between practices and values in Pakistan and thus a strong desire for the society to be more performance oriented (Table 1).

Collectivism

The mean practice score for 61 societies on institutional collectivism is 4.24 (range 3.25–5.22), and that for in-group collectivism is 5.10 (range 3.18–6.36) (Table 1). Thus, the overall scores are higher for in-group collectivism than institutional collectivism in the GLOBE study, a pattern that also exists in the data from Pakistan (Table 1). Pakistan’s institutional collectivism practice mean score is 3.77, ranking it 55 among the 62 societies. Thus, the society does not encourage the collective distribution of resources or collective actions; however, the mean of 5.90 puts it in fourth place for in-group collectivism practices (Table 1).

The institutional collectivism values score of 5.34 is 1.57 points higher than the practice score (Table 1). In contrast, there is a small gap of just –0.68 between the in-group collectivism practice and value scores (Table 1). These calculations suggest that Pakistani society desires an increase in institutional collectivism but also persistence in its strong in-group ties with organizations and families, seeking to reduce in-group collectivism only marginally. The in-group collectivism societal practice scores for Pakistan are among the highest, such that the 1.22 gap for in-group collectivism between societal and organizational practices (Table 2) indicates that the bond with the family as a group is much stronger than the bond with coworkers or an in-group at work.

Gender egalitarianism

For gender egalitarianism, a minimum score of 1 indicates preferential treatment for men, and a maximum score of 7 indicates favored treatment for women. The GLOBE study’s gender egalitarianism practice score across 61 societies equals 3.38 (Table 1), with a range of 2.50–4.08 (Table 1), indicating largely gender-differentiated societies. The mean score of 4.49 for the gender egalitarianism value indicates a greater desire to create opportunities for women.

Pakistan’s gender egalitarianism societal practice score of 2.47 is the lowest among the 62 countries, which indicates a very male-dominated society (Table 1). This domination also emerges in the organizational practice score (Table 2). Yet the gender egalitarianism value scores of 4.11 and 3.85 for society (Table 1) and organizations (Table 2), respectively, suggest a strong desire to create a more balanced society in Pakistan.

Assertiveness orientation

The GLOBE’s assertiveness orientation practice score for 61 societies averages 4.14 (range 3.38–4.81). The mean value scores equal 3.83 (range 2.66–5.56) (Table 1), which implies that people would prefer less assertive behaviors. Pakistan’s GLOBE assertiveness orientation practice score of 3.2 ranks it last in the list of 62 countries; it is a non-assertive society. The gap between the practice and value scores is –0.89, calculated on the basis of Pakistan’s 4.09 assertiveness orientation value score (Table 1). This dimension represents one of the smallest gaps we find; Pakistanis do not prefer to be more assertive but rather are content to continue as a society that values cooperation and avoids confrontation. Although the society score for assertiveness practice is the lowest in Pakistan, the 1.2 gap between societal and organizational practices reflects greater assertiveness in organizations than in society (Table 2).

Future orientation

The average future orientation score for societal practices across 61 societies reaches 3.84 (range 2.88–5.07), thus indicating that most societies have a moderate future orientation level (Table 1). Pakistan, which scores 3.63 and ranks 40 of 62 countries, exhibits a medium–low future orientation. The 2.16-point gap between future orientation practice and value scores is significant, as calculated on the basis of Pakistan’s 5.79 score on future orientation value. Pakistan stands among the countries with the highest scores for future orientation values. Although this society is not particularly future oriented in its practices, its organizations are more so, as indicated by the gap of 1.27 between organizational and societal practices (Table 2).

Power distance

In the original GLOBE study, power distance practices achieved a mean score of 5.17 (range 3.59–5.80), and the mean value was 2.77 (range 2.04–3.65) (Table 1). With its power distance practice mean of 5.86, Pakistan ranks higher than any other society measured as part of the original GLOBE study (Table 1). Pakistan’s power distance mean value score is 2.86, which creates a gap of –3.00 between practice and value (Table 1) – the largest gap across all nine cultural dimensions in the Pakistan data set. That is, respondents really want to reduce power distance in their society. Although Pakistan scored highest on power distance practices, it also exhibits a great gap (1.5) between societal and organizational practices (Table 2), reflecting a slightly lower power distance culture created in organizations, mostly by educated city dwellers working in large organizations, and society at large.

Humane orientation

For the GLOBE humane orientation practice, respondents reported a mean of 4.09 across 61 societies. Pakistan, with a score of 4.11, is close to the average and ranks 27 among 62 societies (Table 1). For this cultural dimensions, as societal practice scores increase, the value scores decrease. However, Pakistan’s humane orientation value score of 5.69 ranks it fifth among the GLOBE societies (Table 1). That is, despite its approximately average practice ranking, the society still desires to be more fair, altruistic, caring, and kind.

Uncertainty avoidance

Finally, across 61 societies, the uncertainty avoidance societal practice score has an average value of 4.17 (range 2.88–5.37). The mean uncertainty avoidance value score is 4.60 (range 3.16–5.16) (Table 1). With an uncertainty avoidance practice score of 3.69, Pakistan ranks 44 among 62 societies; its lower score and higher ranking indicates lower uncertainty avoidance. The uncertainty avoidance value score is 5.16 (Table 2), revealing a desire to avoid uncertainty and seek orderliness, consistency, structures, and procedures.

DISCUSSION

The practice and value scores of Pakistan on the nine GLOBE cultural dimensions provide an overview of Pakistani culture. It scores notably high on power distance and in-group collectivism but low on assertiveness and gender egalitarianism. This finding implies that Pakistan as a society accepts an unequal distribution of power; in which people express pride in, loyalty to, and cohesiveness with their families and society; where people avoid assertive, confrontational, or aggressive behavior; and that acknowledges clear differences in gender roles in society. Considering the values scores reported for the Pakistan sample, the results also indicate a desire to create a more egalitarian society, in which power is shared more equally and differences between genders diminish. However, people appear to treasure the lack of assertiveness and high in-group loyalty of their society and want to retain these cultural values.

What assistance can information about the culture of Pakistan offer to investors, potential investors, corporations, and expatriates? In line with previous research regarding the implications of national culture dimensions for management, this study outlines a brief discussion. In particular, as a society with high in-group collectivism scores, Pakistan prizes loyalty to in-groups, families, and organizations. People do not want to alter this societal value; they want to keep their strong in-group bonds, particularly with families. At the organizational level, this bond is weaker than at the societal level, and people would prefer to reduce it. However, it may not be possible to alter organizational practices and values without changing societal practices.

Collectivist societies, such as China, Russia, and Korea, place heavy reliance on personal references and recommendations, and authors have debated the ethical relativism of such practices (Dunfee & Warren, Reference Dunfee and Warren2001; Ledeneva, Reference Ledeneva2008, Reference Ledeneva2009; Luo, Reference Luo2011; Horak, Reference Horak2017; Horak & Taube, Reference Horak and Taube2015). Such high in-group collectivism practices also exist in Pakistan (Khilji, Reference Khilji2002; Khilji & Rao, 2013; Saher & Mayrhofer, Reference Saher and Mayrhofer2014). Several Western European multinationals that are operating in Pakistan have noted that over time, their recruitment and selection processes have acquired a local flavor, such that they devote greater attention to personal recommendations and references. However, companies with strong organizational cultures continue to practice hybrid versions of recruitment and selection processes. In our interviews with current managers, some of them mentioned their continued efforts to maintain fair and transparent procedures but use personal recommendations as an additional criterion for short-listing. Others cited personal recommendations and references as particularly helpful, because of the lack of standardized academic and vocational qualifications in Pakistan.

In addition, with high in-group collectivism, training and development is more likely to be a reward for maintaining good relations with higher management or a tool to maintain employee commitment (Sinha, Reference Sinha1997; Wilkins, Reference Wilkins2001; Fu & Kamenou, Reference Fu and Kamenou2011; Sartorius, Merino, & Carmichael, Reference Sartorius, Merino and Carmichael2011). Promotions may be influenced by favoritism for in-group members rather than performance (Aycan, Reference Aycan2005; Sartorius, Merino, & Carmichael, Reference Sartorius, Merino and Carmichael2011), and in Pakistan, such practices exist (Khilji, Reference Khilji2002; Husain, Reference Husain2012). Performance ratings are also influenced by interpersonal relations, similar to other collectivist societies such as Bangladesh, India, and Tunisia, where ratings of low performers are consistently inflated by raters who possess positive interpersonal affect toward those employees (Varma, Pichler, & Srinivas, 2005; Yahiaoui, Reference Yahiaoui2014; Hossain, Abdullah, & Farhana, Reference Hossain, Abdullah and Farhana2015).

The distribution of pay and rewards on the basis of individual or group achievements, or the design of an economic system based on individual or collective interests, relates to institutional rather than in-group collectivism. Studies that treat collectivism as a single dimension, in line with Hofstede (Reference Hofstede1980), note the greater use of performance-related pay related to individual rather than group performance in individualistic societies (e.g., Gomez-Mejia & Welbourne, Reference Gomez-Mejia and Welbourne1991; Schuler & Rogovsky, Reference Schuler and Rogovsky1998; Chiang, Reference Chiang2005; Sartorius, Merino, & Carmichael, Reference Sartorius, Merino and Carmichael2011). Pakistan’s institutional collectivism societal ranking is low, with only a narrow difference between societal and organizational scores. Thus, despite its high in-group collectivism ranking, initiatives based on organizational- or societal-level rewards are less acceptable.

The difference in the scores of the two dimensions of collectivism can also be understood by the strong preferences of individuals toward their family, social sect, religious sect, or residents of the same region (Duncan, Reference Duncan1989; Khilji, Reference Khilji2002; Rahman, Reference Rahman2012; Khilji & Rao, 2013; Saher & Mayrhofer, Reference Saher and Mayrhofer2014). The lack of practice or desire for a broad distribution of resources and collective action results from the feudal system that has long existed in Pakistan, in which landlords have controlled large swaths of agricultural land (Husain, Reference Husain2002; Rahman, Reference Rahman2012). Thus, acceptance of the unequal distribution of collective resources aligns with Pakistan’s high power distance score.

Societies or organizations with high power distance also tend to exhibit greater acceptance of formal authority derived from positions of power and status. For example, in China, seniors and supervisors are trusted for their wisdom and expertise (Cooke, Reference Cooke2012). Rather than a joint assessment of needs by managers and employees, decisions about training for employees are made unilaterally by managers or supervisors (Wilkins, Reference Wilkins2001; Festing & Barzantny, Reference Festing and Barzantny2008; Fu & Kamenou, Reference Fu and Kamenou2011; Fregidou-Malama & Hyder, Reference Fregidou-Malama and Hyder2015). Career plans reflect supervisors’ or elders’ advice (Aycan & Fikret-Pasa, Reference Aycan and Fikret-Pasa2003; Festing & Barzantny, Reference Festing and Barzantny2008; Fu & Kamenou, Reference Fu and Kamenou2011). Processes that require participation across hierarchical levels, such as those that ask employees to share their opinions or provide information about their jobs to superiors, seem less suitable (Chen, Zhang, & Wang, Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014; Yang, Zhou, & Zhang, Reference Yang, Zhou and Zhang2015), as are initiatives such as 360° feedback (Davis, Reference Davis1998; Fletcher & Perry, Reference Fletcher and Perry2001). Differences in pay and benefits and different criteria for compensating top- versus lower-level employees also are more readily accepted (Luis & Mejia, Reference Luis and Mejia1991). Employee share options and ownership plans are less prevalent (Schuler & Rogovsky, Reference Schuler and Rogovsky1998).

The impact of power distance on HR practices in Pakistan is not clear. Although the societal power distance scores for Pakistan appear high, scores from the organization level indicate less acceptance of unequal distributions of power. The results also signal strong desires to change this facet of societal culture and to adjust the organizational culture to create more equality in both society and organizations. Thus, organizations that want to create a low power distance culture might be able to do so, though they need to invest in training to change mindsets and explain processes such as participative management.

The practice of and desire for low assertiveness levels offers another important element for understanding human behavior in Pakistan. People are not assertive and tend to avoid confrontations. In line with Hartog’s (Reference Hartog2004) summary of the key characteristics of an assertive society, in Pakistani society, people believe their control over their own fate is limited, so demanding targets, as well as the rewards or penalties related to such targets, are not widely favored. The link of assertiveness to both high- and low-context cultures (Hall, Reference Hall1959), and communication (Hartog, Reference Hartog2004) suggests that communication in Pakistan includes subtle and ambiguous language that avoids confrontation. However, no past studies have explored this dimension. The limited international literature on this topic indicates that assertiveness has significant implications for selection procedures (Pudelko, Reference Pudelko2005; Chiang & Birtch, Reference Chiang and Birtch2010, Reference Chiang and Birtch2011), feedback in appraisals (Hartog, Reference Hartog2004; Varma, Pichler, & Srinivas, 2005; Chiang & Birtch, Reference Chiang and Birtch2010), and communication in day-to-day work (Ollo-López, Bayo-Moriones, & Larraza-Kintana, Reference Ollo-López, Bayo-Moriones and Larraza-Kintana2011; Silva, Roque, & Caetano, Reference Silva, Roque and Caetano2015), as well as forecasting and target setting.

From a business performance perspective, examining the cultural dimension of performance orientation, as often reflected in bottom line figures, may be relevant. In the overall GLOBE sample, societies indicate a 0.32 correlation between performance orientation practices and GDP per capita (Javidan & Hauser, Reference Javidan and Hauser2004). The GLOBE study relies on other economic indicators as well, by combining items from the Human Development Report (UNDP, Reference Varma, Pichler and Srinivas1998), World Competitiveness Yearbook (International Institute for Management Development, 1999), and Global Competitiveness Rankings calculated by the World Economic Forum (1998). According to these data, correlations ranging from 0.29 to 0.61 exist between performance orientation societal practice scores and economic indicators, such as economic prosperity, government support for prosperity, and the World Competitiveness Index (Javidan, Reference Javidan2004).

Pakistan exhibits a medium to low-performance orientation practice score but also reports a strong desire to be more performance oriented, at both societal and organizational levels. Javidan (Reference Javidan2004) suggests that societies with lower performance orientation scores focus more on who people are, rather than what they do. To increase its performance orientation levels, Pakistani society would need to shift its values toward something other than social class, which has long been part of the societal fabric (Khilji, Reference Khilji2002; Husain, Reference Husain2012; Rahman, Reference Rahman2012). In addition, management practices for selection, training, rewards, and appraisals would need to align with more performance-oriented factors. At first glance, some performance-oriented practices may appear to conflict with the high in-group collectivism and low assertiveness cultural practices and values of Pakistan, as discussed in the preceding sections. However, no correlation arises for performance orientation with assertiveness or with in-group collectivism (House et al., Reference House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman and Gupta2004). Also, societies with low assertiveness, like Japan, and high in-group collectivism, like China, have prospered economically. This finding reiterates the need to assess the practice (and value) scores for all nine dimensions simultaneously to develop a comprehensive picture of a particular culture.

Performance orientation practice scores correlate with future orientation (0.63) and uncertainty avoidance (0.58) in the GLOBE study (House et al., Reference House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman and Gupta2004). This is reflected in the scores of Pakistan, as the Pakistani society currently exhibits average to below average future orientation and uncertainty avoidance. However, the organizational scores indicate a significant gap with societal practice scores in Pakistan. That is, the society may be lacking in long-term planning and execution, but its organizations are performing better and express a strong desire to improve further.

This discussion would not be complete without commenting on the low gender egalitarianism score, which indicates whether women have similar opportunities as men, or if there is male domination, in both society and organizations. The labor force participation rate of women in Pakistan is an estimated 25% (World Bank, 2016b), clearly highlighting the gender gap in employment. In our sample of middle managers, only 15% of the respondents were women. This reflects the highly gendered roles in South Asia, including Pakistan, that have been highlighted previously (Murray, Reference Murray2013; Pio & Syed, Reference Pio and Syed2014). In the current study, reported practices in the dynamic telecommunications sector are rather more egalitarian, which may indicate a drive to change. Overall, the scores imply a strong desire to create a more egalitarian society, at least among the educated middle class, which mainly constitutes our sample.

Limitations and further research

This study collected data from Pakistani middle managers, using the GLOBE survey, and then compared these data with the overall GLOBE data set (House et al., Reference House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman and Gupta2004). Some key limitations thus include that the data collection in Pakistan occurred a few years after the data collection in other countries. However, cultural values tend to remain relatively stable over long periods, so the gap of a few years should not affect the comparison (Rokeach, Reference Rokeach1979; Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1980). Also, the analysis uses the scales developed by the GLOBE team, and this study did not undertake an exploratory factor analysis, because one of its key purposes is to compare Pakistan with 61 other societies that had completed GLOBE scales. Furthermore, the sample size of 152 is not representative of the entire population of Pakistan, though it is considered appropriate for cross-cultural research (Hanges & Dickson, Reference Hanges and Dickson2006). This study makes reasonable generalizations about society based on this sample. Given the challenges associated with the length of the study (190 complex questions, 90 min to complete), the sample size also is venerable.

Many avenues for further research also emerge; we present four critical areas. First, the unique and complex design of the GLOBE study, based on cultural practices and values, reflects how things currently are and how people wish they were, in society and organizations. Wide practice–value gaps, which in Pakistan are prominent for power distance, performance orientation, future orientation, and gender egalitarianism, need to be explored by in-depth studies, particularly those focused on change management. The vast society–organization practice gaps for power distance, future orientation, in-group collectivism, assertiveness, and uncertainty avoidance also reveal research avenues for management scholars studying organization–environment interactions. For example, for in-group collectivism, the society–organization gap reveals that the societal practice score is higher than the organizational score, and the value scores show that people would prefer to maintain the high society score, while reducing the organizational in-group collectivism score even further. In-depth qualitative studies can explore the complex challenges and opportunities that these findings represent.

Second, we inferred the impact of cultural dimensions on HR practices in Pakistan by using the results of cross-cultural research carried out in other countries, as well as work published about Pakistan’s economy and culture in other disciplines; a limited number of studies focus directly on this topic. Thus, more work, including in-depth case studies, qualitative discussions, and surveys, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of management in Pakistani culture. For HR, studies should test the impacts of high and low cultural practice and value scores on recruitment and selection, training, performance management, compensation, communication, and talent management. Focusing on a combination of cultural dimensions can provide a more comprehensive picture. Furthermore, independent studies within Pakistan or cross-country comparative studies could expand the body of knowledge. For example, Pakistan has a low assertiveness score; in the original study, other societies with low assertiveness scores included Sweden, New Zealand, and Switzerland, whereas Albania, Nigeria, the United States, and Germany ranked among the most assertive (Hartog, Reference Hartog2004). Pakistan also has a low gender egalitarianism score, whereas in the original study, Hungary, Poland, and Denmark offered the least gender-differentiated practices (Emrich, Denmark, & Hartog, Reference Emrich, Denmark and Hartog2004). Designing cross-country comparisons with such country samples can highlight the impacts of culture on management.

Third, in our attempt to identify empirical studies that describe how the GLOBE cultural dimensions influence various HR practices, we found that some cultural dimensions, particularly power distance and collectivism, have received ample attention from cross-cultural scholars, producing a larger body of knowledge about the impact of these dimensions on various HR practices. For collectivism, the focus has been on general collectivism, as opposed to in-group or institutional forms of collectivism. Uncertainty avoidance, performance orientation, assertiveness, and future orientation have received more limited attention; the cross-cultural studies we reviewed did not include the gender egalitarianism and humane orientation dimensions at all. We thus reiterate the suggestion by Devinney and Hohberger (Reference Devinney and Hohberger2017) that clarity regarding the impact of cultural dimensions on management could be achieved by expanding beyond commonly studied cultural dimensions. We also support the recommendation of McKeown and Petitta (Reference McKeown and Petitta2014), who call for a more complex understanding of the international, interconnected, yet unique context of management studies.

Fourth, this study provides data about the cultural dimensions of Pakistan. Further work can be carried out to detail potential differences in the cultures of the main provinces of Pakistan: Punjab, Sindh, Khyber Paktunkhua, and Baluchistan, as well as the newly formed province of Gilgit-Baltistan. Such an effort could reveal differences and similarities in regional cultures.

CONCLUSION

Understanding the cultural compatibility of HR practices with a country’s culture is vital for effective management in the increasingly global economy. As Pakistan becomes a more important player in the global economy, it is pertinent to extend the GLOBE study by including Pakistan. Its high power distance, high in-group collectivism, and low assertiveness values create unique challenges and opportunities for businesses, especially because these values differ significantly from the dominant management practices of the Anglo-Saxon cluster. Although Pakistani society seeks to change some cultural values, such as reducing power distance and increasing gender egalitarianism, its desire to preserve in-group collectivism and low assertiveness indicates that any contradictory management practices would be difficult to implement. Thus, the insights provided about Pakistani culture and management provide new and more detailed guidance to investors, potential investors, and employers of Pakistani expatriates, who can gain a better understanding of Pakistani values and culture. This study also opens avenues for further research into Pakistan, using the GLOBE dimensions.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank members of the GLOBE team, particularly Mansour Javidan for his support in completing the project. The authors also thank the team of Pakistani researchers who invested their time to collect data for this project, and the Pakistani participants of the study for completing the questionnaire.