INTRODUCTION

Social exchange theory views interpersonal relationships as a balance model of giving and receiving (Homans, Reference Homans1958). Western scholars apply a social exchange perspective to delineate the exchange of resources between two parties in an organization and propose several constructs to describe the strength of exchange in the formal relationships, including leader-member exchange (abbreviated as LMX; Graen & Uhl-Bien, Reference Graen and Uhl-Bien1995; Sparrowe & Liden, Reference Sparrowe and Liden1997; Chen & Tjosvold, Reference Chen and Tjosvold2006), team-member exchange (abbreviated as TMX; Seers, Reference Seers1989; Seers, Petty, & Cashman, Reference Seers, Petty and Cashman1995), and coworker exchange (abbreviated as CWX; Sherony & Green, Reference Sherony and Green2002). However, the social concept of ‘guanxi’ (Chinese interpersonal relationships) should be considered when discussing Chinese coworker relationships since Chinese often mix formal working relationships with personal ones.

Guanxi is an indigenous Chinese construct defined as ‘an informal, particularistic personal connection between two individuals who are bounded by an implicit psychological contract to follow the social norm of guanxi’ (Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004: 306). Recently, the guanxi concept has received increasing attention and gains its status as a legitimate socio-cultural construct in Western mainstream literatures of sociology, social psychology, business, and management (Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004). The concept of guanxi is different from interpersonal relationships in Western societies. Confucius teachings have encouraged Chinese people to respect their elders and leaders (Huang, Reference Huang200), which leads to higher levels of power distance in organizational hierarchies in mainland China and Taiwan than those in the West (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1980).

This cultural difference results in divergent perspectives when discussing vertical and horizontal coworker relationships. The components/dimensions between LMX and TMX/CWX are similar in the emphasis placed on balanced reciprocity including mutual respect, trust, and obligation between two parties (Seers, Petty, & Cashman, Reference Seers, Petty and Cashman1995; Sherony & Green, Reference Sherony and Green2002). Alternatively, supervisor-subordinate guanxi (vertical) and colleague guanxi (horizontal) are distinct with differential expectations of behavioral norms (Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004). For example, the notions of loyalty, obedience, and respect are expected of the subordinate by the superior; while the notion of wisdom and leadership are expected of the superior by the subordinate.

Literature has well documented the supervisor-subordinate guanxi scale and its related work outcomes (Law, Wong, Wang, & Wang, Reference Law, Wong, Wang and Wang2000; Wong, Tinsley, Law, & Mobley, Reference Wong, Tinsley, Law and Mobley2003b; Chen & Tjosvold, Reference Chen and Tjosvold2006; Cheung, Wu, Chan, & Wong, Reference Cheung, Wu, Chan and Wong2009). However, the effect of guanxi between two colleagues has not received sufficient attention due to the absence of a suitable colleague guanxi measurement scale. Two studies dealt with the horizontal coworker relationship from a dyadic viewpoint (Sherony & Green, Reference Sherony and Green2002; Chen & Peng, Reference Chen and Peng2008). In terms of approaching colleague relationship based on social exchange theory, Sherony and Green (Reference Sherony and Green2002) investigated the CWX relationships on a dyadic level and found negative effects of a worker's CWX to the organization commitment. They also noted that ‘CWX perhaps would be a more powerful predictor of work attitudes if we could identify significant coworkers in the network’ (p. 547). The other study addressing the colleague relationship from guanxi concept, Chen and Peng (Reference Chen and Peng2008) provided evidence that coworker closeness is changeable by incidents, thus supporting the dynamic nature of colleague guanxi. The appeal of emphasizing dyadic and horizontal coworker relationships from a dynamic viewpoint necessitates the development of a scale for measuring guanxi intensity.

Recent studies recommend that guanxi be treated as a continuous variable and support the notion that guanxi is elastic, that it is dynamic and can wax and wane within a given guanxi relationship (Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004; Chen, Friedman, Yu, Fang, & Lu, Reference Chen, Friedman, Yu, Fang and Lu2009). Empirical studies have shown that the guanxi can increase or decrease due to positive or negative incidents when interacting (Chen & Peng, Reference Chen and Peng2008). For these reasons, the accepted rules of interpersonal interaction behind the guanxi concept may be a way to structure a model of guanxi intensity between two colleagues.

The central aim of our research thus deals with development of a reliable and valid guanxi scale based on guanxi rules and suggests a model of the guanxi construct with specific norms and obligations. This enables us to contribute to the extant literature in three ways. First, since guanxi is widespread in the Chinese business culture our study can stimulate more empirical inquiry into what Chen and Chen (Reference Chen and Chen2004) have noted ‘a few major weaknesses in the literature of Chinese guanxi theory and research concerned .. not on the construct building and operationalization’ (p. 309) by the testing of a guanxi measurement through the norms and obligations of interaction. Second, examining colleague guanxi in the Chinese context contributes to the Chinese management literature since guanxi plays a critical role in Chinese organizational life due to the relation-oriented nature of Chinese society (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987). Our development of a colleague guanxi scale can help explain the nature of guanxi dynamics of horizontal coworker relationships. Finally, a validated colleague guanxi scale uncovers emic (culturally specific) perspectives of the unbalanced reciprocity system to advance the understanding of this specific emic term by Westerners.

The following sections of this study describe the development of a guanxi scale for measuring guanxi perception of a specific colleague using the guanxi rules. We also discuss the antecedents of guanxi development and use guanxi as a predictor of attitudes between two colleagues. We conducted two studies in order to fulfill our research objectives. Study one was performed to develop and validate a colleague guanxi scale. Study two was performed to cross-validate relationships among guanxi and related constructs.

Literature REVIEW

Dyadic approach to guanxi concept

Numerous scholars have claimed that guanxi is a critical concept for business operations in mainland China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan (Alston, Reference Alston1989; Yeung & Tung, Reference Yeung and Tung199; Luo, Reference Luo1997). Fundamental to the value system of guanxi, the Chinese believe that the existence of an individual is identified by relationships with others (Brunner, Chen, Sun, & Zhou, Reference Brunner, Chen, Sun and Zhou1989) and consider guanxi as a foundation for developing interpersonal networks for support and protection.

Previous studies have used the common social identities to indicate the effects of guanxi dynamics on related work outcomes from two perspectives: network relationship (Hom & Xiao, Reference Hom and Xiao2011) and dyadic relationship (Tsui & Farh, Reference Tsui and Farh1997; Farh, Tsui, Xin, & Cheng, Reference Farh, Tsui, Xin and Cheng1998). One body of research on guanxi based on social network theory (e.g., Luo, Reference Luo1997; Hom & Xiao, Reference Hom and Xiao2011) considers guanxi as a practice that exists within current social networks in which trust and exchange between individuals is established, changed and lost, as the social network evolves to facilitate relational and economic certainty for individuals. Most Western theories focus on network structure and individuals’ positions in the network rather than on the content and process of dyadic relationships (Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004). However, the guanxi network is formed and aggregated by numerous single ties or connections, which means guanxi is essentially personal and operates between two parties (Alston, Reference Alston1989). When attempting to examine the effect of guanxi on attitudes or interactive behaviors at dyadic level, it is necessary to confirm the guanxi bases (ties) and guanxi intensity as it is perceived by an individual. Thus, the other body of research on guanxi is based on dyadic perspective. Chen and Chen (Reference Chen and Chen2004) provide reasons for emphasizing the eco-centered dyadic guanxi. First, guanxi dyads are fundamental units of guanxi networks (Fei, Reference Fei1939). In the classic model of differentiated order, Fei (Reference Fei1939) proposed an ego-centered network of guanxi and contended that the inter-connectedness among the various guanxi entities is not important as long as each entity is connected to the self. Second, Chinese guanxi has been invested with strong dyadic sentiment and obligations independent of shared group identity.

In terms of guanxi bases (ties), scholars of sociology and social psychology claim that guanxi originated from ancient Confucian ideology and is derived from Five Cardinal Relationships (named ‘wu lun’ in Chinese): ruler–subject, father–son, husband–wife, elder brother–younger brother, and friend–friend (Tsui & Farh, Reference Tsui and Farh1997). The fundamental Confucian assumption of human kind is that individuals exist in relation to others and modern Chinese societies (on the mainland or overseas) remain very relationship oriented (Redding & Wong, Reference Redding and Wong1986 in Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004).

However, the effect of guanxi bases may change over time because guanxi bases of initial acquaintances are relatively lean in interpersonal significance; whereas, the same bases of long-time partners may be pregnant with trust and qing (feeling) (Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004). To test these differences, it is essential to assess guanxi intensity in addition to identifying guanxi bases. For example, an analysis of the social psychology of Chinese concluded that Chinese tend to adopt multiple standards of behavior for interacting with the different persons around them (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987). Hwang explained, when one person interacts with another, the first question he or she would carefully consider is ‘What is the guanxi between us?’ and ‘How strong is our guanxi?’

Guanxi's unbalanced reciprocal system

Social exchange theory views interpersonal relationships as a balance model of giving and receiving (Homans, Reference Homans1958). The theoretical foundation of social exchange theory is the norm of reciprocity which is explained as: ‘The reciprocity norm usually refers to a set of socially accepted rules regarding a transaction in which a party extending a resource to another party obligates the latter to return the favor’ (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Hom, Tetrick, Shore, Jia, Li and Song2006: 378). Sahlins (Reference Sahlins1972) viewed reciprocal exchange as a continuum and proposed three reciprocal types including ‘negative reciprocity,’ ‘balanced’ reciprocity’ and ‘generalized reciprocity’ with three dimensions: immediacy of return, equivalence of returns, and interest. ‘Generalized reciprocity’ features an indefinite reimbursement period, undefined equivalency of return, and low self-interest suitably to describe the guanxi concept. Thus, according to the reciprocity norm proposed by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Hom, Tetrick, Shore, Jia, Li and Song2006) and Sahlins’ (Reference Sahlins1972) reciprocity typology, we consider guanxi is a special case of social exchange theory in that both emphasize the obligation in resource exchanges between two parties; nevertheless, the operations of the reciprocal system is different in values and the time frame of repayment (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987; Alston, Reference Alston1989; Liu, Reference Liu1993; Yeung & Tung, Reference Yeung and Tung1996; Hackley & Dong, Reference Hackley and Dong2001). For example, social transactions in the West are usually seen as isolated occurrences. The objective is to maintain balance in each transaction, with great emphasis placed on immediate gains from the interaction. In contrast, guanxi is maintained and reinforced through continuous long-term association, reciprocating givers with more favors (Hackley & Dong, Reference Hackley and Dong2001), and where reciprocation (‘bao’ in Chinese) is not as timely and equivalent as it is in the Western perspective (Liu, Reference Liu1993).

The unbalanced reciprocal system of guanxi can be explained by four reasons based on the Chinese culture roots of benevolence, complementarity, immeasurable affection, and long-term orientation. First, the unbalanced reciprocal system can be traced back to Confucianism, which encourages each individual to become a righteous person with virtue of benevolence (jen). There are two essential points of Confucian benevolence: loyalty (chung) and magnanimity (shu). Chung means doing one's best, while shu implies consideration (Lin & Ho, Reference Lin and Ho2009). Based on the two virtues, people should consider others’ feelings and repay favors and increase the value of the favor given (Yeung & Tung, Reference Yeung and Tung1996). The old Chinese ethical codes, ‘Receive a droplet of generosity; repay like a gushing spring’ and ‘Do not impose on others what you yourself do not desire’ are illustrative of the virtues.

Moreover, role obligation is also valued in Confucianism for maintaining the harmony of society. There are basically three kinds of guanxi relationships: family, familiar person and stranger (Tsui & Farh, Reference Tsui and Farh1997). An important Chinese cultural characteristic is to extend kin-relationships to people who are not kin (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Friedman, Yu, Fang and Lu2009). When extending from family to familiar relationship (quasi-family) renging and mianzi become the exchange rules (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987; Tsui & Farh, Reference Tsui and Farh1997). A singular feature of guanxi is that the weaker partner can call for special favors for which he/she does not have to equally reciprocate (Alston, Reference Alston1989). When the giver provides resources to the receiver in need, the giver requires face (respect, honor) by giving support to the receiver. This is the basic rationale of unbalanced reciprocity according to the symbiotic system of guanxi, in which the guanxi of both sides is complementary instead of being equal (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987).

In addition to instrumental reciprocity, the other critical ingredient of guanxi is affective attachment (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987; Yang, Reference Yang1994; Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004; Chua, Morris, & Ingram, Reference Chua, Morris and Ingram2009). One key feature of Chinese familial collectivism is that individuals are mutually dependent on each other not only for instrumental resources but also for socio-emotional support (Chua, Morris, & Ingram, Reference Chua, Morris and Ingram2009). Affective attachment refers to an emotional connection, understanding, and willingness to care for one another in any circumstance. They engage in such behavioral patterns to receive social rewards for fulfilling their role obligation. However, the immeasurability of affection represents the unequally reciprocation in guanxi relationships.

Finally, the long-term orientation is a cultural characteristic of China and East Asia (Hofstede & Bond, Reference Hofstede and Bond1988), resulting in the emphasis on a future relationship in guanxi reciprocity. The timing of reciprocity in Western society is considered to be immediate, short-term, or discharged within a certain period of time (Tsui & Farh, Reference Tsui and Farh1997). In the Chinese society ‘be my teacher for a day, be my teacher for a lifetime,’ that is, the concept of lifetime reciprocity, or even reciprocity in afterlife, if one thinks favors are too great to be discharged in this life. Thus, the return need not and in most cases should not always be immediate. Immediate repayment is the ‘worst and most foolish kind’ (Yang, Reference Yang1994: 144) because it closes rather than opens up relationships.

Guanxi's in-group identification

According to the differential order perspective (Fei, Reference Fei1939), the guanxi effect is similar to the in-group/out-group dichotomy of social identity theory. The concept of guanxi and in- and out-group membership both adhere to the idea of differentiating people into close and distant relationships. However, the ways to classify people into in- or out-groups behind these two concepts differ in two aspects: the criteria of identifying in-group membership and the orientation of in-group membership. First, the in-group membership of guanxi is based on common backgrounds such as birth place, alma matters (Tsui & Farh, Reference Tsui and Farh1997; Farh et al., Reference Farh, Tsui, Xin and Cheng1998) or the psychological distance between guanxi partners in the guanxi net and the location of self (Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004). By contrast, in- and out-group identity in Western culture is based on demographic features; for example, race, gender, age, and educational level (Tsui & Farh, Reference Tsui and Farh1997) or competence/reliability (Liu, Reference Liu1993). Second, the in-group concept of guanxi is directed toward dyad personal relationships and in- and out-group identity is directed toward a group. That is, Chinese nationals primarily define their self-concept in terms of connections and role relationships with significant others (relational self) rather than membership in symbolic groups (collective self) (Brewer & Chen, Reference Brewer and Chen2007: 137). Maintaining in-group reciprocal ties allow the Chinese to confirm self-identify. The perspective of differential order (named ‘schaxu geju’) (Fei, Reference Fei1939) is used to exchange favors according to their relational distances with one another.

Classifications of coworker relationships

Coworker relationships can be separated into vertical (between supervisor and subordinate) and horizontal (between group members) relationships with different expectation of norms and behaviors (Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004; Chen & Peng, Reference Chen and Peng2008).

Research on vertical relationships has focused on the nature of LMX (Graen & Uhl-Bien, Reference Graen and Uhl-Bien1995; Sparrowe & Liden, Reference Sparrowe and Liden1997; Chen & Tjosvold, Reference Chen and Tjosvold2006) and supervisor-subordinate guanxi (Law et al., Reference Law, Wong, Wang and Wang2000; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Tinsley, Law and Mobley2003b; Chen & Tjosvold, Reference Chen and Tjosvold2006; Cheung et al., Reference Cheung, Wu, Chan and Wong2009). Chen and Tjosvold (Reference Chen and Tjosvold2006) posit that the distinct concepts of LMX and leader-member guanxi can enhance participative leadership. Research on horizontal relationships, on the other hand, has pointed out the value of investigating relationships among organizational members other than that of the leader and follower (Seers, Reference Seers1989; Sparrowe & Liden, Reference Sparrowe and Liden1997; Sherony & Green, Reference Sherony and Green2002). From a social exchange perspective, CWX have been suggested to have influence on employees’ work attitudes and performance (Seers, Reference Seers1989; Seers, Petty, & Cashman, Reference Seers, Petty and Cashman1995; Liden, Wayne, & Sparrowe, Reference Liden, Wayne and Sparrowe2000).

While there are several studies that offer scales for measuring supervisor-subordinate guanxi (vertical relationship) (e.g., Law et al., Reference Law, Wong, Wang and Wang2000; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Tinsley, Law and Mobley2003b), there is no guanxi scale to measure colleague guanxi (horizontal relationship) to our knowledge. TMX differs from colleague guanxi in several features. First, TMX does not deal with colleague relationship on a dyadic level; rather, it is designed to address an employee's exchange relationship with a peer group as a team (Seers, Reference Seers1989; Seers, Petty, & Cashman, Reference Seers, Petty and Cashman1995). Second, TMX and guanxi have distinct cultural origins; the former is developed and tested in a Western cultural context and guanxi is rooted in Chinese culture. Third, TMX focuses on the balanced reciprocity of resources between parties, while guanxi emphasizes an unbalanced reciprocal system embedded with specific rules. Thus, it is clear that TMX differs from colleague guanxi since it does not address dyadic relationships but focuses on the work team as the unit of analysis, such as the frequency and willingness of helping other team members get things done on the job or helping each others to be productive in a team (Seers, Petty, & Cashman, Reference Seers, Petty and Cashman1995). It appears that TMX cannot be used to measure the dyadic colleague guanxi intensity due to the asymmetry in levels of analysis, resources exchanged, and cultural differences.

Existing approaches to guanxi measurement

In terms of guanxi intensity, there are two fundamental approaches to the guanxi construct; one is categorical, and the other is dynamic (Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004). The categorical approach views guanxi as given particularistic ties. Some studies use guanxi ties (e.g., family, relative, same natal origin, same family name, former classmate, etc.) to examine the effects of guanxi, wherein two parties will give preferential treatment to each other (Farh et al., Reference Farh, Tsui, Xin and Cheng1998; Zhang & Yang, Reference Zhang and Yang1998). Jacobs (Reference Jacobs1979) posits, however, that a relational view of guanxi ties is inadequate for a full explanation of the many facets of guanxi.

Guanxi building depends not only on relational bases; it also includes the association between two parties (Liu, Reference Liu1993). Guanxi ties are infrequent among colleagues in a business organization (Chou, Reference Chou2002), and it may be inaccurate to assume that any kind of family tie is stronger than the familiar ties (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Friedman, Yu, Fang and Lu2009: 376). Cheng, Farh, and Chang (Reference Cheng, Farh and Chang2002) hold that the force of guanxi is dependent upon an individual's subjective nature rather than an objective determination of the guanxi tie. Thus, viewing guanxi from a dynamic approach and treating guanxi as a continuous variable (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Friedman, Yu, Fang and Lu2009) are probably more suitable than guanxi ties alone to explain the nuances of guanxi.

Following the dynamic approach of measuring guanxi intensity, some authors have taken a uni-dimensional approach of ‘informal interaction’ (Chen & Tjosvold, Reference Chen and Tjosvold2006; Law et al., Reference Law, Wong, Wang and Wang2000; Wong, Ngo, & Wong, Reference Wong, Ngo and Wong2003a) or ‘closeness’ (Cheng, Farh, & Chang, Reference Cheng, Farh and Chang2002; Cheung & Gui, Reference Cheung and Gui2006) to capture guanxi intensity. The advantage of using informal interaction is that it describes specific activities to increase the explicitness of guanxi measurement. Guanxi measures focusing on closeness emphasize the importance of intensity in guanxi scaling, however, these uni-dimensional approaches of ‘your closeness to the matchmaker’ or ‘your familiarity with the matchmaker’ (Cheung & Gui, Reference Cheung and Gui2006), may not be sufficient to explain the diverse meaning of guanxi. Viewing guanxi as a multidimensional construct is a more promising vehicle for capturing the fullness of the concept.

Research on guanxi as a multidimensional construct (Lee & Dawes, Reference Lee and Dawes2005) used three dimensions (i.e., face, reciprocal favor, and affect) to describe a client-salesperson guanxi (business relationship), while Wong et al. (Reference Wong, Tinsley, Law and Mobley2003) describe guanxi (superior–subordinate relationship) as having five dimensions comprised of social activities, financial assistance, giving priority to the guanxi person, celebration of special events, and mutual emotional support. These efforts at developing guanxi measures featuring informal interactions (behaviors/activities) provide a more concrete way to quantify the guanxi concept; however, attempting to capture all the behaviors or activities related to guanxi is a near impossible task. We turn to the rule approach as a basis for colleague guanxi measurement.

Components of the guanxi construct

Fulfillment and maintenance of the unbalanced reciprocal system requires that the interpersonal interaction be operated according to specific rules. The guanxi rules that guide the Chinese in their interactions are ‘renging,’ ‘mianzi/face,’ ‘reciprocity,’ and ‘bao/reciprocation’ (see Appendix A for a definition of each term). The former two factors are grounded in a theoretical model of norms for interpersonal interactions (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987) which can be used to manipulate the relational magnitude with related partners, while the latter two factors are based on an unbalanced reciprocal system of obligations for interaction (Liu, Reference Liu1993; Tsang, Reference Tsang1998). We expect if an employee's perception of interactions with a coworker fits these norms and obligations, he/she will have strong guanxi intensity with a specific colleague.

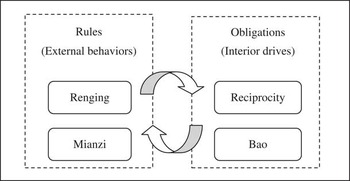

We then separate these guanxi rules into norms (exterior behaviors) and obligations (interior drives) and propose that renging and mianzi are classified as exterior behavioral rules which are manageable in that they can be used to build, maintain and strengthen relationships; while reciprocity and bao are inner drives which are generated after an evaluation of the relational obligations following the exterior behaviors. The conceptual model of guanxi is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Conceptual model of guanxi

Relative to exterior behaviors, Hwang (Reference Hwang1987) proposed renging and mianzi as appropriate guanxi rules for addressing situations of resource allocation. Renging could be seen as a resource for social exchange (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987), where the renging debt is an unpaid duty to reciprocate (King, Reference King1988) resulting from favor exchange in interpersonal associations. Mianzi is not specific to Chinese, however it is not emphasized in Western society (King, Reference King1988). The Chinese view mianzi as a critical element of guanxi and value mianzi of friends more than that of general others (Park & Luo, Reference Park and Luo2001). The idea of ‘saving face’ or ‘giving face’ is restricted to guanxi partners (Chen, Reference Chen1988).

With respect to guanxi obligations (interior drives), previous guanxi research emphasizes reciprocal obligation when defining guanxi (Tsang, Reference Tsang1998; Pearce & Robinson, Reference Pearce and Robinson2000). Guanxi partners are usually obligated to respond to requests for assistance from each other (Tsang, Reference Tsang1998) and favors received can be stored and are expected to be repaid with more favors at the right time (Liu, Reference Liu1993). We suggest that the obligated reciprocity and bao/reciprocation are generated intrinsically and can be viewed as drives within the reciprocal obligation system.

In terms of reciprocity, members can receive resources from the guanxi network and have an obligation to share resources and provide voluntary assistance (Tsang, Reference Tsang1998). The resources in guanxi are further defined as gifts or favors exchanged for mutual benefit based on a reciprocal obligation to respond to requests for help (Pearce & Robinson, Reference Pearce and Robinson2000). Inability or unwillingness to respond to others’ requests will impair their guanxi maintenance (Tsang, Reference Tsang1998). The other facet of the unbalanced reciprocal system is bao (reciprocation), which is also used to maintain the harmony of guanxi (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987). It surfaces when someone perceives that others are being nice, and will seek to repay those individuals with even more favors, rather than merely seek to achieve a balance of mutual interest. If favors are not reciprocated, guanxi will deteriorate, making it difficult to maintain social harmony of interpersonal relationships.

Underpinning the unbalanced reciprocal system (see Figure 1), guanxi partners bond each other through obligations to exchange favors (Alston, Reference Alston1989). Any kind of favor receiving will spontaneously accrue a renging debt thus resulting in interior drives of reciprocity and bao. When an individual does something meaningful for the other, the beneficiary is obligated to return more favor to the giver (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987) and provides voluntary assistance to the giver in need. That is, the exterior behaviors of renging and mianzi will initiate the motivations of reciprocity and bao. However, if a renging debt is not reciprocated, the giver will feel disrespected by the beneficiary thus resulting in a loss of face (mianzi) (Park & Luo, Reference Park and Luo2001). The four critical dimensions of the guanxi concept form the underpinning for measuring guanxi intensity. We then define guanxi as ‘a dyadic connection between two individuals, built on interactive experience, imbued with an unbalanced reciprocal system that follows specific rules of renging, mianzi, reciprocity, and bao.’

Guanxi reality in China

The Chinese society of mainland China and Taiwan are similar in holding the same historical culture. The Chinese motto: ‘If you don't have a connection, find one. Once you have found the connection, you can depend on it to resolve your problems,’ reflecting the Chinese relation orientation. Under this belief, the behavioral model of guanxi is similar in mainland China and Taiwan where people consider guanxi is manipulated to receive resources. There is a basic interpersonal model of face and favor in Chinese society (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987) that helps to explain the practice of guanxi. To strive for social resources controlled by a particular allocator (e.g., money, goods, information, and status), an individual may adopt several strategies to enhance his or her influence over the allocator by visiting, giving gifts, or inviting the other person to banquets as weddings, funerals, or birthday parties in one's family and festivals in one's home village (Huang, Reference Huang2000).

The interpersonal model can be extended to business and management practices in China. For example, guanxi has long been recognized as one of the major factors for success when doing business in China (Yeung & Tung, Reference Yeung and Tung1996; Luo, Reference Luo1997). In both mainland China and Taiwan, business people first strive to build up personal relationships with a potential customer, and once admitted to a guanxi relationship, business follows. In contrast to the Chinese way of conducting business, Western business practices tend to begin with transactions; if successful, a personal relationship may follow (Luo, Reference Luo1997). In addition, Luo (Reference Luo1997) found a direct correlation between a corporation's level of guanxi connections and its sales growth in China. Furthermore, Chen and Tjosvold (Reference Chen and Tjosvold2006) showed that foreign managers can use personal guanxi to increase Chinese employee effectiveness. By balancing personal guanxi with organizational performance standards, managers may contribute to alleviate some of the negative consequences of guanxi (Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004).

While the Chinese in East Asia from Taiwan, mainland China, and Hong Kong are all deeply rooted in traditional Chinese culture, there are differences in political, economic, and values systems (Hofstede & Bond, Reference Hofstede and Bond1988). The Taiwanese sample used is well suited for developing a colleague guanxi scale in that Confucian philosophy is preserved in Taiwan through the education system. The Book of Analects, containing sayings and doings of Confucius by his followers are included in the textbooks of Taiwanese national education systems. Confucius’ teachings have encouraged Chinese people to respect their elders and leaders (Huang, Reference Huang2000), which leads to higher power distance in organizational hierarchies in Taiwan than those in the West (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1980).

In the empirical studies using Taiwanese samples, Farh, Earley and Lin (Reference Farh, Earley and Lin1997) developed an indigenous measure of organizational citizenship behavior and found two emic dimensions of ‘interpersonal harmony’ and ‘protecting company resources’ not present in the Western organizational citizenship behavior scale. Lin and Ho (Reference Lin and Ho2009) sampled workers from Taiwan, mainland China, and Hong Kong and found that the level of long-term orientation and emphasis on reciprocity and reciprocation are higher in Taiwan samples than in mainland China or Hong Kong samples.

STUDY 1

Development and validation of the colleague Guanxi scale

To develop a scale to measure guanxi intensity we reviewed the literature to form an operational definition for each guanxi dimension (Churchill, Reference Churchill1979). We then conducted interviews to generate the items of the colleague guanxi scale. The Delphi method was used to confirm the veracity of each guanxi dimension and its corresponding items. Finally, empirical testing was performed to verify the reliability and validity of the scale for the further empirical test in Study 2.

Item generation

Thirty full-time employees of 10 organizations in Taiwan whose working experience exceeded 3 years were asked to participate in our study. The group was 50% male with an average age 33.8 years. Interviews with each participant were used to generate items for the questionnaire based on the four guanxi dimensions. We provided participants with the operational definitions of each dimension (see Appendix A) and asked them to describe two behaviors for each dimension they would do for a close colleague. We obtained from this process a total of 240 statements describing the state of colleague guanxi. One of the authors paraphrased each of these behaviors or behavioral intentions into sentences. Three of the authors of this study then examined these sentences. Redundant, ambiguous, and some unsuitable items were eliminated in the initial screening. There were 25 items left, exemplifying the four dimensions of the guanxi construct which were distributed as follows: renging (6 items), mianzi (10 items), reciprocity (5 items), and bao (4 items).

The Delphi method (Lindstone & Turoff, Reference Lindstone and Turoff1975; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell1992) was used to verify the adequacy of the dimensions and their corresponding items of guanxi. Five middle or top managers enrolled in an executive master of business administration program and five people holding a PhD in a management field were invited to form a Delphi panel to rate the 25 items. Panel members were given a structured questionnaire and were instructed to rate the items based on the relatedness of each item to a specific dimension (1 = not at all, 7 = completely agree). The mean scores and deviations for all items on each of the dimensions were calculated.

The Delphi procedure consisted of two rounds, which took place over a 2 month period (Holden & Wedman, Reference Holden and Wedman1993). Judges rated the items on two criteria; (a) consistency (standard deviation is less than 0.5) and (b) importance (mean is more than 5.0). The means and quartile deviations of items from the first round were counted and presented in the second round questionnaire. There were nine items that failed to reach consensus during the first round. Results from the first round were shared with second round participants before the second round. These discussions resulted in eight items that did not reach the convergence criteria of a mean score of <5.0 and a quartile deviation of more than 1.0 in the second round. The remaining 17 items were therefore confirmed for further analyses. These items are shown in Appendix B.

Data collection (first data set)

Judgmental sampling was used to obtain a sample size suitable for the primary stage of an exploratory study when researchers want to select a specific sample (Cooper & Schindler, Reference Cooper and Schindler2003). This type of sampling technique is also known as purposive sampling and authoritative sampling (Castillo, Reference Castillo2009). Judgmental sampling is a selection process which involves a subjective selection of potential respondents based on researchers’ knowledge and professional judgment about some appropriate characteristics required for the sample members (Zikmund, Reference Zikmund2003; Castillo, Reference Castillo2009). The sample was not restricted to any specific industry or institution due to the pervasive nature of the guanxi concept.

After receiving the agreement of 20 companies to participate in this study, research assistants delivered the questionnaires to the organizations. The presence of researchers can facilitate data collection (Chen & Tjosvold, Reference Chen and Tjosvold2006); accordingly, a member of the research team visited the participating companies to explain the purpose of the study. They also collected the completed survey to reinforce that responses would be kept confidential. The sampled companies consisted of various industries, including banking, insurance, real estate, automobile, restaurant/hotel, hospital, electronics, and food. A total of 600 were distributed and 535 were returned, for a response rate of 89.17%. Unqualified samples (e.g., data with missing values) were removed, leaving 416 valid data sets for a useable response rate of 69.33%.

In the final sample there were 203 (48.80%) males and 213 (51.20%) females, of which 74.28% were between the ages of 20 and 40 years. The average educational level was a bachelor's degree, for 290 (69.71%) of the total sample. The majority of the participants worked in the service industry (55.77%) followed by manufacturing (17.55%), while 303 participants were from private companies (72.84%). Three hundred and ten respondents (74.52%) were junior workers in their organizations, with an average seniority of 5.90 years.

Item purification

Item analysis

We used the internal consistency coefficient and critical ratio to check item quality. For all items of colleague guanxi the response format was from 1, ‘strongly disagree,’ to 7, ‘strongly agree.’ The sample was divided into high- and low-score groups based on the total guanxi scale score. The lowest 25% of those sampled became the low-score group, and was coded ‘1,’ while the highest 25% of those sampled were selected as the high-score group, and was coded ‘3,’ and other responses were coded ‘2’. T-tests were then used to check the differences of each item scores between the high-score and low-score groups. The result indicates that the corrected item-total correlations were between 0.39 and 0.86, and all exceeded 0.35, while the critical ratios (t-values) were between 8.68 and 20.67. The t-values of all the items were statistically significant. In sum, the result shows that the scale fits the criteria of the item analysis.

Reliability analysis

The internal consistency of each guanxi dimension was estimated with coefficient alpha, which were calculated separately for the items that comprises the four guanxi factors. A large coefficient α (Cronbach's α>0.70 for the exploratory measure; Nunnally, Reference Nunnally1978) provides an indication of strong item covariance or homogeneity and that the domain of a concept has been adequately captured by the selected items (Churchill, Reference Churchill1979: Reference Wu, Hom, Tetrick, Shore, Jia, Li and Song68). The Cronbach's α for renging, mianzi, reciprocity, and bao was 0.81, 0.88, 0.93, and 0.85, respectively (see Table 1). The results indicate that our colleague guanxi scale is reliable in measuring the guanxi factors.

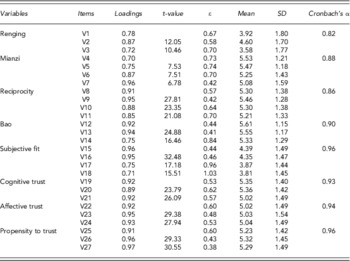

Table 1 Study 1 –reliability and CFA of colleague guanxi scale

Notes. χ2 = 182.261, df = 71; RMSEA = 0.063, GFI = 0.94; CFI = 0.98; IFI = 0.98.

BAO = reciprocation; CFA=confirmatory factor analysis; MIN = mianzi; REC = reciprocity; REN = renging.

Confirmatory factor analysis among horizontal colleague guanxi factors

To further validate the construct domain of colleague guanxi, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis to assess whether each item is loaded on its corresponding guanxi dimensions for two reasons. First, we developed the colleague guanxi scale on the basis of theoretical guanxi rules (e.g., Hwang, Reference Hwang1987; Liu, Reference Liu1993; Tsang, Reference Tsang1998; Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004) to form the structure model of guanxi construct; second, the generated items of each dimension had been confirmed by the Delphi method. Therefore, it was necessary to examine if it was appropriately organized.

Using AMOS's maximum likelihood procedure, three items were eliminated because the factor loading was <5.0 (the loading of BAO4 was 0.41) or the items’ residuals are highly correlated to items of bao (i.e., REC5 and REC6). This resulted in a 14-item guanxi measure with 3 items on renging, 4 items on mianzi, 4 items on reciprocity, and 3 items on bao. A re-examination of the items on each factor confirmed that all four factors have a clear conceptual meaning. The results of factor loadings and fit indexes are detailed in Table 1, demonstrating that the four-factor model fitted the data well (χ2 = 182.26, df = 71; RMSEA = 0.063, GFI = 0.94; CFI = 0.98) and reached the convergent validity for significant factor loadings (γ > 0.50).

To test discriminant validity among the four factors of horizontal colleague guanxi scale (named HCG hereafter), we then compared the hypothesized model with seven alternative models (six three-factor models and a one-factor model). Comparisons of this four-factor model with three- and one-factor models, as shown in Table 2, indicate that none of the dimensions were redundant. The change of χ2 was significant, indicating a worse fit than the four-factor model. The competing one-factor measurement model did not fit our data (χ2 = 1551.69, df = 76; RMSEA = 0.220, GFI = 0.61; CFI = 0.69).

Table 2 Study 1 – discriminant validity analysis results

Notes. BAO = bao; MIN = mianzi; REC = reciprocity; REN = renging; SIG = social interaction guanxi.

n = 416; ***p < .001.

Discriminant validity with social interaction guanxi (SIG)

We used the subordinate–supervisor guanxi scale proposed in Law et al. (Reference Law, Wong, Wang and Wang2000) as a comparative scale. The subordinate–supervisor guanxi scale is directed to supervisor-subordinate dyadic relationship, we, therefore, rephrased the items of the subordinate–supervisor guanxi scale to measure the frequency of social interaction between two colleagues (SIG). To test the discriminant validity between the HCG and SIG, we estimated the hypothesized five-factor model (four factors for guanxi and one for SIG). The SIG scale stresses the informal interactions, while our HCG scale focuses on the normative behaviors and obligations of guanxi.

We then compared this hypothesized model with three alternative models. These alternative models tested whether SIG was different from any of the four guanxi factors. As shown in Table 2, significant χ 2 difference tests showed that the five-factor fits better than all four alternative four-factor models, in which SIG is considered the same as one part of our guanxi model. The correlations between the four guanxi factors of renging, mianzi, reciprocity, and bao with SIG are 0.65, 0.58, 0.61 and 0.47, respectively. These comparison tests suggest that the discriminant validity between the four dimensions of HCG and SIG is due to the traditional Chinese rules.

Study 1 purified our guanxi measure and confirmed the reliability, convergent and discriminant validity of the HCG scale. The second study was designed to cross-validate the scale on another sample and show the nomological validity of the scale by embedding it in a model of similarity (similar attitudes and values), cognition (cognitive trust), and affection (affective trust).

STUDY 2

Cross-validation of the guanxi scale

The proposed structural relationships between guanxi and related constructs that form a nomological network are shown in Figure 2. According to social attraction theory, similarity in attitudes, values, and beliefs may facilitate interpersonal attractions (Newcomb, Reference Newcomb1956). The similarity-attraction paradigm suggests that individuals are more attracted to, and have more positive attitudes about similar others (Byrne, Reference Byrne1971). Research suggests that similarity in attitude has more impact on interpersonal attraction than similarity in personality, race, or demography (Glaman, Jones, & Rozelle, Reference Glaman, Jones and Rozelle1996). Moreover, value congruence may enhance interpersonal interactions in the workplace by increasing the predictability of the behaviors of others (Adkins, Ravlin, & Meglino, Reference Adkins, Ravlin and Meglino1996). Thus, it is argued that similarity is the source of interpersonal attraction (Williams & O'Reilly, Reference Williams and O'Reilly1998), and that similarity in attitudes or values increases interpersonal attraction and affection (Byrne, Clore, & Worchel, Reference Byrne, Clore and Worchel1966; Riordan, Reference Riordan2000). We proposed that the similarity in attitudes and values cognized by an individual (i.e., subjective fit) helps to generate interpersonal attraction among colleagues and thus facilitates their interactions and associations for guanxi development.

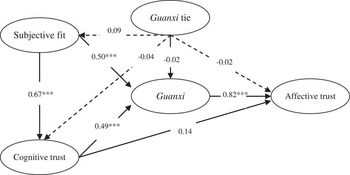

Figure 2 The structural model of a proposed nomological network for guanxi.

Notes. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; χ2 = 233.17, df = 81; RMSEA = 0.081, GFI = 0.90; CFI = 0.96

Prior research has found that guanxi generates a positive effect on trust (Farh et al., Reference Farh, Tsui, Xin and Cheng1998; Wong, Ngo, & Wong, Reference Wong, Ngo and Wong2003a; Lee & Dawes, Reference Lee and Dawes2005). In order to increase the precision of our structural model, we specified that guanxi will influence an organizational member's affective trust toward coworkers since affections develop after interacting over time (McAllister, Reference McAllister1995). When people are successful in establishing higher guanxi intensity with another, their attitude toward that person will be more positive (e.g., affective trust). The partner with strong guanxi will be considered as an insider and will receive more trust. We hypothesized that guanxi have a direct effect on affective trust in a colleague.

We also tested a structural path from cognitive trust to affective trust based on findings that high cognitive trust leads to strong affective trust of a colleague (McAllister, Reference McAllister1995). Cognitive trust reflects one's competencies and a sense of responsibility (Cook & Wall, Reference Cook and Wall1980; McAllister, Reference McAllister1995) instead of assessing the interpersonal relationship. An organizational member will develop a basic cognition of a coworker's working ability and reliability after working with that person over time. In general, organizational members are more willing to cooperate with a colleague who is recognized as reliable for instrumental motivation of guanxi (Lee & Dawes, Reference Lee and Dawes2005). Yang, Van de Vliert, Shi and Huang (Reference Yang, Van de Vliert, Shi and Huang2008) also found that except for friendship, the disputer's competence will influence employees’ minds about how to handle dispute between their colleagues. We thus argued that cognitive trust is a basic consideration before taking further action of building colleague guanxi.

Guanxi tie is argued to have a positive influence on trust (Farh et al., Reference Farh, Tsui, Xin and Cheng1998); however, the effect of guanxi ties in the development of interpersonal relationships is also doubted by other scholars (Jacobs, Reference Jacobs1979; Law et al., Reference Law, Wong, Wang and Wang2000; Dunfee & Warren, Reference Dunfee and Warren2001). We added the guanxi ties as a control variable in the proposed nomological network of guanxi shown in Figure 2.

Method

Procedure (second data set)

Purified items (see Study 1) with other established measures were administered to participants from ten organizations in Taiwan. Under the judgmental sampling method participation of the 10 organizations was facilitated by executive master of business administration students who voluntarily participated in this study. After following up with these organizational contacts, surveys were administered to 300 employees recruited by our contacts in the 10 organizations. Research assistants delivered 30 questionnaires to each of the 10 participating organizations. Respondents were asked to select one of their colleagues in the same position as the object person for evaluation. To reduce potential concern for being involved in evaluating others and being evaluated themselves, participants were told that their responses would be confidential. They were also informed that their supervisors supported their participation in the study. After the explanation of the process, respondents were allotted ~30 min to finish the questionnaires. Completed questionnaires were immediately collected by the assistants.

A total of 294 surveys were received, resulting in a completion rate of 98%. This high response rate was possibly because the questionnaires were collected on the spot instead of through mailing. Ten questionnaires were eliminated due to unusable responses resulting in 284 valid questionnaires. One hundred twenty-five respondents were from the services industry (44.01%), 80 respondents were from manufacturing (28.17%), and 60 respondents were from public-owned organizations (21.27%).

Participants

The sample was near gender balanced (47.62% were male), 197 respondents were between 20 and 40 years of age (63.37%), 194 respondents had a bachelor's degree (68.31%) and 51 respondents had either a master's degree or a doctorate (17.96%). Two hundred and four respondents were junior workers in their organizations (71.83%), with an average tenure of 7.06 years.

Measures

The questionnaire included (a) the 14-item guanxi measure developed in Study 1, (b) the 6-item scale measuring cognitive trust and affective trust translated by Chen (Reference Chen2000), Cronbach's α = 0.91 and 0.89, respectively, (c) the 4-item measure of similarity in attitudes and values between colleagues cognized by respondents from the subjective fit scale (Chen, Reference Chen2000, Cronbach's α = 0.80), (d) guanxi ties as a objective variable to show the relational bases between two colleagues, and (e) a 3-item measure of an individual's propensity to trust referring to interpersonal trust scale (Rotter, Reference Rotter1967) as a common factor.

Cognitive trust was measured by responses to the following items: (a) I have confidence in his/her work quality; (b) His/her attitude toward work is serious; (c) His/her working ability is undoubted. Affective trust was measured by: (a) I am willing to share my thoughts, feelings, and hopes with him/her; (b) When I encounter problems in my job, I am willing to tell him/her and I also know that he/she is willing to listen to me; (c) I know he/she will give me constructive suggestions and show concern for me when I share problems in my job with him/her. The items on the scale of subjective fit were: (a) Our values are similar; (b) We see things from similar perspective; (c) We have common interests; (d) We have the same hobbies. For all items above the response format was from 1, ‘strongly disagree,’ to 7, ‘strongly agree.’

To address the common method variance (CMV), we examined an objective indicator named guanxi ties and a common factor called trust propensity. The examples of guanxi ties were family/relative, same last name, same natal origin, former classmate, former colleague, former teacher/student, former boss/subordinate, and former neighbor (Farh et al., Reference Farh, Tsui, Xin and Cheng1998). Situations with one or more of these eight guanxi ties in the respondent's relational bases with the object were coded ‘1’ and others were coded ‘0’. The items of trust propensity scale were: (a) In dealing with strangers one is better off to be cautious until they have provided evidence that they are trustworthy; (b) In a competitive environment one is better off to be cautious because other people may use you for their sake; (c) It is better to believe that people is selfish in nature no matter what they say. The response format of trust propensity was from 1, ‘strongly disagree,’ to 7, ‘strongly agree.’

Measurement model

To cross-validate the factor structure of the guanxi scale, we did a confirmatory factor analysis of the 14 guanxi items with the three cognitive trust items, the three affective trust items, and the four subjective fit items using AMOS 7.0. The overall guanxi construct is specified as the underlying factor formed by its four dimensions. As in Study 1, results generally supported the discriminant validity of the guanxi measure. Overall χ2 of the model was 501.15 with 175 degrees of freedom. The model showed a comparative fit index of 0.94, a goodness of fit index of 0.86, and a root mean square error of approximation of 0.079. These goodness-of-fit indices support the notion that the measurement model fit reaches an acceptable level.

Reliability analysis

The internal consistency of each of the dimensions was estimated with coefficient α. Coefficient α's were calculated separately for the four guanxi factors and related constructs. In Table 3, The Cronbach's α for each guanxi dimension was between 0.82 and 0.90; for subjective fit was 0.93; for cognitive trust and affective trust were 0.93 and 0.95, respectively; and for trust propensity was 0.96.

Table 3 Measurement model analysis

Note. χ2 = 501.15, df = 175; RMSEA = 0.079, GFI = 0.86; CFI = 0.94.

Validity analysis

There were three categories of validity test completed on the data: (a) convergent validity, (b) discriminate validity, and (c) nomological validity. Hair, Anderson, Tatham and Black (Reference Hair, Anderson, Tatham and Black1998) suggest three criteria to check for convergent validity. The criteria are (a) all the standardized item loadings must exceed 0.70 and reach statistical significance, (b) composite reliability should exceed 0.60, and (c) average variance extracted should exceed 0.50. The results shown in Table 3 and Table 4 indicate most of the standardized loadings of items exceeded 0.70 and were statistically significant, the composite reliability of all factors exceeded 0.60, and the average variance extracted exceeded 0.50. The results support the convergent validity of our colleague guanxi measure. In Table 4, the correlation coefficients between a construct and other constructs were generally less than the square root of its average variance extracted shown in boldface diagonal values, indicating each construct is separate from other constructs (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981). The results supported the discriminant validity of these measures and also showed that the colleague guanxi is a construct distinct from subjective fit, cognitive trust, and affective trust.

Table 4 Correlations of constructs and discriminant analysis

Note. The boldface diagonal values are the square roots of AVE of each variable.

Full model analysis

After confirming the reliability and validity of the measurement model, we examined the nomological network of the colleague guanxi concept by combining the 14 guanxi items into four indicators by averaging. We then utilized these four indicators to demonstrate the colleague guanxi intensity for a full model analysis.

Figure 2 shows the path coefficient estimates for the nomological model of guanxi, with acceptable goodness of fit (χ2 = 233.17, df = 81; RMSEA = 0.081, GFI = 0.90; CFI = 0.96). The hypothesized paths were significant and in the predicted direction. The colleague guanxi was positively related to the degree of subjective fit (β31 = 0.50***, t = 12.89). Two parties with more similar attitudes and interests easily build and maintain higher guanxi intensity. This finding corresponds to the similarity-attraction paradigm, where the degree of interpersonal attraction increases when the attitudes and values of two parties are similar (Byrne, Clore, & Worchel, Reference Byrne, Clore and Worchel1966). Moreover, the influence of cognitive trust on perceived guanxi was confirmed (β32 = 0.49***, t = 7.50). A person holding cognitive trust in a specific colleague by recognizing a colleague's working ability and reliability will be more willing to interact with that colleague for the instrumental motivation of guanxi (Lee & Dawes, Reference Lee and Dawes2005).

In terms of affective trust in the colleague relationships, cognitive trust is positively related to affective trust, but did not reach statistical significance (β42 = 0.14, t = 1.69, 0.10 > p > .05). Our results demonstrate however, that colleague guanxi exerts a positive influence on affective trust (β31 = 0.82***, t = 8.36). When guanxi rules are well executed between colleagues for a period of time, they will be more willing to share their problems and expect positive responses. Furthermore, we can say that the effect of guanxi on affective trust is stronger than that of cognitive trust. This result sheds light on the role of guanxi in interpersonal trust. That is, for Chinese colleague relationships, the interpersonal affections are probably generated through interactions in guanxi-style rather than merely cognition of someone's competence.

Finally, we also tested an alternative model of viewing the colleague guanxi as an outcome variable by reversing the path between guanxi and affective trust. The alternative model (χ2 = 298.03, df = 81; RMSEA = 0.097, GFI = 0.88; CFI = 0.94) did not fit the data as well as the proposed baseline model.

Common method variance

Our four major variables (i.e., colleague guanxi, subjective fit, cognitive trust, and affective trust) were collected from the same source, which may result in inflated correlations between variables. To address the CMV among these variables, we conducted Harman's one factor test suggested by Podsakoff and Organ (Reference Podsakoff and Organ1986) and confirmed that the one-factor model did not fit the data well (χ2 = 2561.31, df = 248; RMSEA = 0.182, GFI = 0.52; CFI = 0.67).

To further control this bias we incorporated an unmeasured and objective indicator into the hypothesized model (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). The guanxi ties here was viewed as a control variable by placing it as an antecedent to all other variables. The results showed that all of the paths from guanxi ties to other variables were not significant (all p > .10), which implies that the prior relational base is not a predictor for the interpersonal trust and guanxi intensity. Guanxi ties are infrequent among colleagues in our sample corresponding to the opinion of Chou (Reference Chou2002) and have limited influence in work relationships (Jacobs, Reference Jacobs1979; Liu, Reference Liu1993; Cheng, Farh, & Chang, Reference Cheng, Farh and Chang2002).

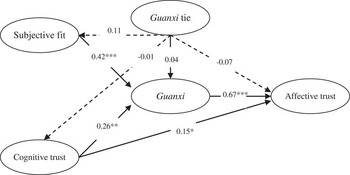

Finally, we further test the nomological network of guanxi by considering a common factor to partial out the method variance. We took the latent variable of trust propensity as a predictor to all items of latent variables without changing the hypothesized relationships of other latent variables. The results indicated that the trust propensity was significantly correlated to all of the observed variables (standardized coefficients were from 0.51 to 0.79; p < .001), which means the variable of trust propensity can be viewed as a common factor to all the items. After controlling the possible effect of common method variance to our model, the hypothesized relationships between the latent variables remain the same and the deflation of path coefficients seems more reasonable and realistic (see Figure 2 and Figure 3 for comparison).

Figure 3 The structural model of a proposed nomological network for guanxi under the effect of common factor. Notes. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; χ2 = 264.06, df = 112; RMSEA = 0.069, GFI = 0.91; CFI = 0.97

DISCUSSION

The current findings add important conceptual and empirical insights into the literature on guanxi. First, we propose the guanxi model based on critical rules of Chinese interpersonal interactions and confirmed the reliability and validity of the horizontal colleague guanxi scale (HCG) in Study 1. Second, a result of the intense colleague guanxi in this study is the enhanced effectiveness of affective trust between two colleagues and its role in mediating the cognition (subjective fit and cognitive trust) to affection (affective trust).

It is important to note that after controlling for the effects of a prior relational base (i.e., guanxi ties) and a common factor (i.e., trust propensity) the proposed baseline model is still supported by our results. For the Chinese employees, guanxi therefore is a critical variable for predicting an individual's attitudes toward colleagues. In sum, we expand the theory about guanxi by explaining the mechanisms that stimulate the formation of guanxi and make guanxi influential in horizontal colleague relationships in an organization.

Theoretical and practical implications

The guanxi scale developed in this study synthesizes current guanxi definitions and measurements of guanxi. The scale for measuring colleague guanxi presented in this study is oriented toward Chinese rules and obligations (i.e., renging, face, reciprocity, and bao) rather than affections, which distinguishes it from the Western affective approach (e.g., love, familiarity, and affections) or the attitudinal approach (e.g., like, satisfaction, and trust). Therefore, the colleague guanxi scale manifests the unique characteristics of the guanxi concept.

Research on Chinese guanxi has often focused on instrumental benefits and obligations rather than true affective expressions or emotions. Our findings supplement the existing views of the implicit and complex nature of guanxi. We construct a model to present the mixed features (instrumental and expressive) of guanxi by showing that guanxi can bridge the interpersonal interaction from the state of cognitive evaluation to that of affective relationship.

In this study we treat guanxi as a neutral term (Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004) used to evaluate the intensity of guanxi rules performed in a horizontal colleague relationship. We suggest future research to identify the Chinese affections to see whether they are involved in guanxi rules or are apart from the guanxi concept, for example, how to identify a gift-giving or a face-saving behavior is out of a true sincerity or instrumental purposes. Further empirical studies may also try to apply the colleague guanxi scale in managerial contexts. For instance, two types of interpersonal exchanges exist, economic, and social (King, Reference King1988), and this study provides useful perspectives on such social exchanges.

In terms of practical implications, the most notable difference in managerial practices between Western cultures and Chinese/Asian cultures is that the former stresses formal contracts and process while the latter stresses personal guanxi (Davies, Leung, Luk, & Wong, Reference Davies, Leung, Luk and Wong1995). This culture difference results in the mix of formal work relationship with social ones by Chinese employees. Our study explicates the nature of the guanxi dynamics of horizontal colleague relationships in an organization and advances the understanding of this specific emic term by Westerners. For the well-developed colleague guanxi, the formal and social exchanges are pervaded with guanxi rules which coexist and co-act to establish the affective trust between two colleagues.

Finally, King (Reference King1988) noted that according to the structure of differential treatment, which is part of the cultural logic of Chinese ethical relationships, the Chinese feel obliged to help relatives and friends. This study adds to that notion by explaining why private affairs override public ones, or why the morality of returning favors outweighs objective morality, owing to a refusal to assist relatives and friends being perceived as a type of ‘ruthlessness.’ In addition to morality issues, guanxi may be helpful for individual career development, especially in the Chinese society. However, with the internal management of organizations, the negative effects of guanxi deserve further consideration.

Generalization of the horizontal colleague guanxi scale

The horizontal colleague guanxi scale developed in this study is based on Chinese guanxi rules of interpersonal interaction. We believe this guanxi scale is an emic construct to be culture-specific and unique to the Chinese contexts. Owning to the lack of comparable values or cultural background, the implied meaning of these items might be difficult to accept by Westerners. That means if researchers want to discuss the effects of guanxi in an organization, the colleague scale is more suitable in Chinese contexts where people endorse common cultural values or beliefs.

However, there is no emic term presented in the items of our colleague guanxi scale. If researchers want to approach the cross-cultural research, this guanxi scale may also be tested in an organization outside the China where there are employees holding different cultural values. As Farh, Earley and Lin (Reference Farh, Earley and Lin1997) presumed that people exposed to a common environmental setting (e.g., being raised in mainland China or Taiwan) develop a shared understanding of the world around them, share specific values, and can be distinguished from others who do not share these values. Thus, the term ‘cross-cultural’ has been used to depict differences in individuals’ values about cultural dimensions, regardless of whether they are co-acting or have a common nationality (Farh, Earley, & Lin, Reference Farh, Earley and Lin1997).

Limitations

Several limitations of the current research are noteworthy. First, we obtained the data at one point in time; thus the cross-sectional nature limits causal assertions. Longitudinal study may address how the relationships of guanxi are increased by cognitive processes and lead to the attitudes toward a colleague over time.

Second, the data for this study came from Taiwan local firms, which may have special characteristics that influenced the results. Further research should consider conducting studies in foreign-owned companies in order to ensure the generalizability of the research findings in this study. It might also be beneficial to study cross-cultural influence on the effects of guanxi on work outcomes. Guanxi itself is a very general phenomenon, not limited to Taiwan. We speculate that similar effects may also exist in employees who hold similar cultural values, especially in collectivist cultures based on Confucianism that values personal relationship.

Finally, surveys with variables that come from the same source are said to be vulnerable to the problem of CMV. In order to deal with CMV concern, first, we used an objective indicator to show that a scarcity of former ties leads to the insignificant relationships between guanxi ties and other related variables. Second, we added a common factor into our model, called trust propensity, and were able to empirically show that the variable of propensity to trust others is significantly related to all of the observed variables. Further, that when partialling out the method variance, the proposed relationships of the hypothesized model remain stable (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). Third, there are two guanxi factors (i.e., renging and mianzi) based on actual behaviors and one variable evaluated by an actual situation (i.e., guanxi ties), that is, the variables rated by the participants are not all conceptual; rather, they have an objective feature. Fourth, we also tested alternate models including a one-factor model and a path reversed model to confirm the proposed model structure. Last, the convergent and discriminant validity of the colleague guanxi scale was confirmed by two studies. As presented earlier, the multifactor structures of the data from both the first and the second studies seemed to refute the existence of a single, dominant factor due to common method variance. Therefore, the results may not be seriously affected by CMV.

CONCLUSION

This study develops a scale for measuring the intensity of horizontal colleague guanxi reflective of Chinese cultural characteristics. We point out a prospective way to operationalize this construct by examining the exterior behaviors (norms of renging and mianzi) and the interior drives (obligations of reciprocity and bao) in dyadic relationships. The guanxi concept was tested in Chinese organizational settings, rather than developing a concept specific to the organizational environment, and offer evidence that describing guanxi by rules/obligations is a suitable way to measure colleague guanxi intensity. The items for the guanxi intensity scale do not involve moral content (right or wrong) or attitudes (like or dislike), but are neutral descriptions of interactions between two parties according to guanxi rules. The empirical results verify that guanxi is a multidimensional construct that exists in Chinese working environments, that follows specific rules for building and maintaining guanxi.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editor and anonymous referees for their helpful comments. The authors greatly appreciate the support of the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, ROC.

Appendix A: Operational definitions of guanxi dimensions

Appendix B: Items in the horizontal colleague Guanxi scale

Renging

1. Sometimes he/she gives me small gifts.

2. He/she frequently takes care of me, such as reminding me about details related to my job.

3. He/she has made considerable efforts such as using their personal knowledge, cash, or connections to tide me over.

Mianzi

4. I never embarrass him/her in public.

5. I respect his/her feelings.

6. He/she never embarrasses me in public.

7. He/she does not respect my feelings.*

Reciprocity

8. When he/she is in trouble, I will exert myself to help.

9. I will voluntarily give him/her a help when he/she is in need.

10. I am willing to use my personal networks to help him/her.

11. I will exert myself to assist him/her in completing jobs that are not mine.

12. He/she will exert himself to assist me in completing work tasks for which he/she is not responsible. X

13. I feel it is hard to refuse his/her request. X

Bao

14. If I receive favors from him/her, I don't always pay them back.*

15. If I receive favors from him/her, I make certain to return them in future.

16. I believe that I must attempt to repay and increase the value of favors even when I am unable to do so immediately.

17. I expect him/her to do me a favor in return for favors I have done for him/her. X

Note: *reverse item; X deleted from the scale finally.