Introduction

The microfoundations revolution has shed light on how individuals and teams contribute to firm heterogeneity (Ployhart & Hale, Reference Ployhart and Hale2014). Traditionally, scholars have examined organizational and environmental variables when exploring differences among firms. In doing so, they have noted that heterogeneity among firms is associated with various capabilities related to understanding the environment and moving and updating resources (Galvin, Rice, & Liao, Reference Galvin, Rice and Liao2014). Called dynamic capabilities, these refer to ‘the abilities of an organization to create, extend or modify their resource base intentionally’ (Helfat et al., Reference Helfat, Finkelstein, Mitchell, Peteraf, Singh, Teece and Winter2009, p. 1). However, despite reports of positive effects on organizational performance (Bitencourt, Santini, Ladeira, Santos, & Teixeira, Reference Bitencourt, Santini, Ladeira, Santos and Teixeira2019; Fainshmidt, Pezeshkan, Frazier, Nair, & Markowski, Reference Fainshmidt, Pezeshkan, Frazier, Nair and Markowski2016; Zhou, Zhou, Feng, & Jiang, Reference Zhou, Zhou, Feng and Jiang2019), competitive advantages (Di Stefano, Peteraf, & Verona, Reference Di Stefano, Peteraf and Verona2014; Peteraf, Di Stefano, & Verona, Reference Peteraf, Di Stefano and Verona2013), external fitness (Helfat & Peteraf, Reference Helfat and Peteraf2009), survival (Dixon, Meyer, & Day, Reference Dixon, Meyer and Day2014), and innovation outcomes (Mitchell & Skrzypacz, Reference Mitchell and Skrzypacz2015), the sources of firms' dynamic capabilities are unclear (Kurtmollaiev, Reference Kurtmollaiev2017; Salvato & Vassolo, Reference Salvato and Vassolo2014).

At the organizational level, scholars have explored variables such as access to tangible and intangible resources, firm strategies focused on knowledge management, and the establishment of institutional partnerships (Bitencourt et al., Reference Bitencourt, Santini, Ladeira, Santos and Teixeira2019). At this level, environmental changes are the source of dynamic capabilities when organizations respond to them. Hence, in stable environments, firms do not require dynamic capabilities. However, the organizational approach is unable to explain the complexity of dynamic capabilities (Felin, Foss, Heimeriks, & Madsen, Reference Felin, Foss, Heimeriks and Madsen2012). Similarly, the stimulus-response model invoked by organizational level explanations does not account for the innovative process; it posits that threats and opportunities are intrinsic to the business environment, and does not offer an explanation of the causal mechanism underlying the firm's response (Bendig, Strese, Flatten, da Costa, & Brettel, Reference Bendig, Strese, Flatten, da Costa and Brettel2018).

Nevertheless, firms face an unstructured business environment daily (Irwin, Drnevich, Gilstrap, & Sunny, Reference Irwin, Drnevich, Gilstrap and Sunny2022). Such environments do not present threats or opportunities; rather, they involve changes that can be interpreted as threats or opportunities through perceptual processes. Thus, exploring the sources of dynamic capabilities requires a microfoundations approach that incorporates the conceptual tools of the behavioral perspective to challenge the stimulus-response model (Felin, Foss, & Ployhart, Reference Felin, Foss and Ployhart2015; Felin et al., Reference Felin, Foss, Heimeriks and Madsen2012; Gavetti, Reference Gavetti2005; Helfat & Peteraf, Reference Helfat and Peteraf2015; Ployhart & Hale, Reference Ployhart and Hale2014).

According to the microfoundations approach, dynamic capabilities arise from actions and interactions among individuals. These capabilities are emergent phenomena that are articulated through psychological and social processes (Felin et al., Reference Felin, Foss, Heimeriks and Madsen2012; Hodgkinson & Healey, Reference Hodgkinson and Healey2011). In the articulation process, chief executive officers (CEOs) are a source of variability because they are responsible for building, integrating, and reconfiguring a firm's resources. In firms, they ‘orchestrate’ the resources and capabilities of their organizations to adapt to environmental changes (Kor & Mesko, Reference Kor and Mesko2013; Sirmon & Hitt, Reference Sirmon and Hitt2009).

Nonetheless, CEOs cannot create dynamic capabilities. Instead, they activate the underlying mechanisms that influence employees' performance conditions, facilitating social interactions and learning in the firm (Bendig et al., Reference Bendig, Strese, Flatten, da Costa and Brettel2018). In other words, CEOs play a pivotal role in developing dynamic capabilities and stimulating the conditions under which these capabilities can emerge. To stimulate the strengthening of dynamic capabilities, CEOs use their dynamic managerial capabilities (Adner & Helfat, Reference Adner and Helfat2003; George, Karna, & Sud, Reference George, Karna and Sud2022) supported by individual resources such as cognition, human capital, and social capital (Durán & Aguado, Reference Durán and Aguado2022; Lee & Yang, Reference Lee and Yang2014). For the purposes of this study, we emphasize the role of managerial cognition.

The contribution of managerial cognition has hitherto been hidden due to the high number of cognitive variables reported in the literature, including perceptual, attentional, attitudinal, and other cognitive styles. In this context, we assert that managerial cognition is not a single variable; rather, it encompasses a family of variables that could be articulated based on their function in the support of dynamic managerial capabilities. Therefore, it is necessary to assess the current state of research by identifying the cognitive variables reported in the literature and evidence of their association with dynamic capabilities. We have decided to adopt a meta-analytic approach because it can assist us in assessing the current research, examine the cognitive variables reported, and estimate the association of each variable with dynamic capabilities. In contrast to qualitative reviews, a meta-analysis is a type of quantitative literature review that allows the integration of results in the literature and the exploration of hypotheses that were not addressed in the primary research (Sartal et al., Reference Sartal, González-Loureiro and Vázquez2021). Additionally, it is useful for exploring the heterogeneity in the results of primary studies (Carlson & Ji, Reference Carlson2011; Sartal et al., Reference Sartal, González-Loureiro and Vázquez2021). Consequently, the aim of this study is to analyze the association between CEOs' managerial cognition and firms' dynamic capabilities.

To conceptualize the association between CEOs' managerial cognition and dynamic capabilities, we have adopted the model proposed by Bendig et al. (Reference Bendig, Strese, Flatten, da Costa and Brettel2018), which explains collective social phenomena through individual action and social interaction. According to this model, CEOs' traits trigger complex underlying mechanisms, facilitating the emergence of collective phenomena as the dynamic capabilities. We have focused the analysis on the trigger role of the CEOs, excluding the cognitive phenomena of top management teams because they are not considered in the model. They are incomparable to the individual cognition, and need to be subjected to separate analysis.

Overall, this study makes several contributions. First, it offers a theoretical model that builds bridges between managerial cognition, dynamic managerial capabilities, and dynamic capabilities. This is achieved by applying the model of Bendig et al. (Reference Bendig, Strese, Flatten, da Costa and Brettel2018). Second, this study offers a classification of cognitive variables reported in the literature in three types of dynamic managerial capabilities: managerial sensing, managerial seizing, and managerial reconfiguration. Third, it quantifies the relationship between CEOs' managerial cognition variables and dynamic capabilities as an overall construct for the three types of proposed dynamic managerial capabilities, and the individual correlation for each cognitive variable. Fourth, it explores moderator variables that can modify the strength of the correlation. And fifth, it illustrates the active role of CEOs in the emergence of dynamic capabilities, highlighting that their comprehension of the environment is related to the development of those capabilities. In sum, this paper locates CEOs' managerial cognition as a trigger of the causal mechanism that underlies dynamic capabilities, offering a new area for multidisciplinary studies using psychological and business variables in strategic management.

In the following sections, we describe the theoretical framework of dynamic capabilities, the microfoundations approach, and the concept of managerial cognition. We then move on to detailing our methodology and results before discussing our findings.

Theoretical framework

Dynamic capabilities

The dynamic capabilities framework extends the theoretical arguments of the resource-based view (Nelson & Winter, Reference Nelson and Winter1982), pointing out that rare, valuable, inimitable, and irreplaceable resources can be created by the same organization (Ambrosini & Bowman, Reference Ambrosini and Bowman2009; Galvin, Rice, & Liao, Reference Galvin, Rice and Liao2014). Dynamic capabilities are ‘the ability of an organization to create, extend or modify their resource base intentionally’ (Helfat et al., Reference Helfat, Finkelstein, Mitchell, Peteraf, Singh, Teece and Winter2009, p. 1). According to Helfat et al. (Reference Helfat, Finkelstein, Mitchell, Peteraf, Singh, Teece and Winter2009), the term ‘create’ includes all forms of resource creation, including obtaining new resources, acquisitions, alliances, innovation, and entrepreneurial activities. The term ‘extend’ refers to enlarging the current resource by adding more of the same; for instance, promoting the growth in an ongoing business. Finally, ‘modify’ refers to changes made in the business, including the destroying, selling, closing, or discarding of resources. In sum, dynamic capabilities are a mechanism for enhancing consistency between organizational resources and changes in the environment, allowing future adaptation (Teece, Reference Teece2014).

Teece (Reference Teece2007) classifies dynamic capabilities into three categories: sensing, seizing, and reconfiguration. The sensing capability captures changes in the environment that may be interpreted as opportunities or threats; seizing focuses on the mobilization of resources to exploit opportunities; and finally, the reconfiguration capability enables a continuous renewal of resources to maintain benefits sustainably. It also encompasses enhancing, combining, protecting, and reconfiguring the business assets.

A prominent feature of dynamic capabilities is that they are developed through the history of the organization, and thus are hard to imitate (Teece, Reference Teece2007, Reference Teece2014). Although competitors can generate similar capabilities, it is not possible to replicate them in their entirety, inasmuch as they are developed and articulated by tacit knowledge components that cannot be easily transferred (Nonaka, Hirose, & Takeda, Reference Nonaka, Hirose and Takeda2016).

Although the effects of dynamic capabilities on organizational performance and adaptation have been reported in prior studies (Bitencourt et al., Reference Bitencourt, Santini, Ladeira, Santos and Teixeira2019; Fainshmidt et al., Reference Fainshmidt, Pezeshkan, Frazier, Nair and Markowski2016), the current discussion centers around the origins of these valuable capabilities (Kurtmollaiev, Reference Kurtmollaiev2017). Scholars have repeatedly reported positive effects on the performance, adaptation, and creation of competitive advantages. Several moderators have also been identified, such as the size of the organization (Fernandes, Ferreira, Prado Gimenez, & Rese, Reference Fernandes, Ferreira, Prado Gimenez and Rese2017; Fernández-Ortiz & Lombardo, Reference Fernández-Ortiz and Lombardo2009) and environmental dynamism (Frank, Guettel, & Kessler, Reference Frank, Guettel and Kessler2017; Singh, Charan, & Chattopadhyay, Reference Singh, Charan and Chattopadhyay2022; Wilhelm, Schlömer, & Maurer, Reference Wilhelm, Schlömer and Maurer2015). Nonetheless, the sources of these dynamic capabilities have not been defined. In this paper, we use a microfoundations approach to study the sources of these capabilities.

Microfoundations of dynamic capabilities

Scholars have proposed two explanations for the sources of dynamic capabilities: those that use organizational-level variables and microfoundations explanations based on individual variables and social interactions (Salvato & Vassolo, Reference Salvato and Vassolo2014). At the organizational level, dynamic capabilities are firms' responses to environmental changes. Accordingly, Bitencourt et al. (Reference Bitencourt, Santini, Ladeira, Santos and Teixeira2019) used a meta-analytic study to synthesize the major organizational-level variables that predict the development of dynamic capabilities. They note that access to tangible and intangible resources, firm strategies focused on knowledge management, and the creation of institutional partnerships promote dynamic capabilities, with moderate correlation coefficients between .34 and .41.

On the other hand, the microfoundations approach states that the sources of dynamic capabilities are in the individual variables and social interactions among individuals. Specifically, with regard to managerial cognition, research has evidenced that CEOs' interpretations of business environments (Roundy, Harrison, Khavul, Pérez-Nordtvedt, & McGee, Reference Roundy, Harrison, Khavul, Pérez-Nordtvedt and McGee2018) and managerial attention (Eggers & Kaplan, Reference Eggers and Kaplan2013) are related to the development of dynamic capabilities. However, some contradictory results have been left unexplained. For instance, Garrett, Covin, and Slevin (Reference Garrett, Covin and Slevin2009) state that the perception of the environment and the perception of being a pioneer in the market exhibit a negative relationship with dynamic capabilities, but Simon and Shrader (Reference Simon and Shrader2012) point out a positive relationship. Furthermore, Dibrell, Craig, and Hansen (Reference Dibrell, Craig and Hansen2011) report a non-significant relationship between managerial attitudes about the business environment and innovation, but Yang, Wang, Zhou, and Jiang (Reference Yang, Wang, Zhou and Jiang2018) identify a positive relationship.

Nonetheless, when these two types of explanations are compared, a microfoundations approach offers a number of advantages. First, all social systems, including organizations, consist of people and exist because of people (Felin & Foss, Reference Felin and Foss2005). Organizational-level explanations overlook the fact that behind each organizational variable lies a micro-founded phenomenon. Even though knowledge management and the creation of institutional partnerships have been acknowledged by Bitencourt et al. (Reference Bitencourt, Santini, Ladeira, Santos and Teixeira2019) as predictors of dynamic capabilities, these variables are outcomes of the managerial decision-making process and the social interaction between organizational agents such as CEOs, employees, and teams. Hence, we must explore the sources of dynamic capabilities in individuals and their interactions, and not only in organizational variables (Kurtmollaiev, Reference Kurtmollaiev2017).

Second, organizational-level explanations do not solve the problem of agency: specifically, where to look for dynamic capabilities (Kurtmollaiev, Reference Kurtmollaiev2017). Organizational-level explanations suppose that sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring are actions carried out by an agent called an ‘organization,’ a theoretical view which is both ambiguous and inexact. It is a reification of organizations. On the other hand, the microfoundations approach recognizes the role of individuals within organizations, their resources, and their social interactions, which are the building blocks of dynamic capabilities (Felin, Foss, & Ployhart, Reference Felin, Foss and Ployhart2015; Miron-Spektor, Ingram, Keller, Smith, & Lewis, Reference Miron-Spektor, Ingram, Keller, Smith and Lewis2018; Ployhart & Hale, Reference Ployhart and Hale2014; Teece, Reference Teece2007; Winter, Reference Winter2013). The answer to the problem of agency is to ascertain the agents responsible for organizational changes and their social dynamics. Consequently, the role of CEOs is predominant because of their senior level of influence provided by the institutional hierarchy (Kurtmollaiev, Reference Kurtmollaiev2017).

Furthermore, the conceptualization of the mechanisms underlying organizational variables are described by Bendig et al. (Reference Bendig, Strese, Flatten, da Costa and Brettel2018), applying Coleman's (Reference Coleman1990) model, which establishes that collective social variables may be grounded in individual actions and social interactions between individuals. Hence, the microfoundations approach tries to unravel the underlying constituents of collective phenomena, opening the black box (Abell, Felin, & Foss, Reference Abell, Felin and Foss2008; Fellin et al., Reference Felin, Foss and Ployhart2015). Thus, Bendig et al. (Reference Bendig, Strese, Flatten, da Costa and Brettel2018) apply Coleman's model to understand the role of CEOs in the development of dynamic capabilities. According to that study, CEOs foster the conditions to allow the emergence of collective phenomena. In the case of dynamic capabilities, CEOs cannot create these organizational capabilities; rather, they mobilize their firm's resources, enabling the development of complementarities and the emergence of aggregated organizational phenomena as dynamic capabilities.

In Figure 1, we depict the model proposed by Bendig et al. (Reference Bendig, Strese, Flatten, da Costa and Brettel2018). CEOs' managerial cognition is a type of CEO trait comprising perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes, which influences a CEO's managerial actions. Due to the hierarchical position of CEOs, they can mobilize firm resources that influence the conditions under which employees work, thus fostering learning and coordination among individuals. Furthermore, dynamic capabilities emerge from the coordination among such individuals. Therefore, to understand the association of firm resources and dynamic capabilities, the path of the micro-founded causal mechanism activated by CEOs must be explained. Bendig et al. (Reference Bendig, Strese, Flatten, da Costa and Brettel2018) test this model, revealing that a CEO's personality influences dynamic capabilities through the firm's knowledge capital.

Figure 1. Model of Bendig et al. (Reference Bendig, Strese, Flatten, da Costa and Brettel2018).

Note. This model describes the micro-founded mechanism underlying dynamic capabilities. Adapted from Bendig, Strese, Flatten, da Costa, and Brettel (Reference Bendig, Strese, Flatten, da Costa and Brettel2018).

Dynamic managerial capabilities

Subsequently, CEOs in the dynamic capabilities framework are crucial because they are responsible for identifying opportunities and threats, making decisions about the mobilization of resources and productive capabilities, and continuously updating organizational resources and capabilities (Adner & Helfat, Reference Adner and Helfat2003; Kor & Mesko, Reference Kor and Mesko2013). Their managerial actions foster conditions for the rise of collective phenomena. Their institutional role calls on them to ‘orchestrate’ the resources and capabilities of their organizations to adapt to environmental changes (Kor & Mesko, Reference Kor and Mesko2013; Sirmon & Hitt, Reference Sirmon and Hitt2009). Also, from the entrepreneurial approach George, Karna, and Sud (Reference George, Karna and Sud2022) claim that dynamic managerial capabilities perspective is a better alternative for entrepreneurial research than dynamic capabilities framework because it is focused on the role of the managers.

Following this assertion, dynamic capabilities involve the actions of CEOs and require them to display specific managerial actions, which Adner and Helfat (Reference Adner and Helfat2003) describe as dynamic managerial capabilities. These are ‘capacities with which managers build, integrate and reconfigure organizational resources and capabilities’ (Adner & Helfat, Reference Adner and Helfat2003, p. 1012). Thus, CEOs use their managerial capabilities to stimulate the building of dynamic capabilities. According to Helfat and Peteraf (Reference Helfat and Peteraf2015), they can be divided into three types: managerial sensing, managerial seizing, and managerial reconfiguration.

To display dynamic managerial capabilities, CEOs apply their individual psychological and social resources (Helfat & Martin, Reference Helfat and Martin2015). Adner and Helfat (Reference Adner and Helfat2003) also divide these managerial resources into three groups: managerial cognition, social capital management, and managers' human capital. Therefore, dynamic managerial capability is a formative construct where resources converge (Coltman, Devinney, Midgley, & Venaik, Reference Coltman, Devinney, Midgley and Venaik2008). Such individual resources would account for the diverse skill levels of CEOs in sensing (lost) opportunities and threats, seizing, and reconfiguring (Corrêa, Good, Kato, & Silva, Reference Corrêa, Good, Kato and Silva2019; Mostafiz, Sambasivan, & Goh, Reference Mostafiz, Sambasivan and Goh2019). In this study, we focus on managerial cognition. For an explanation of managerial social capital and managerial human capital, see Adner and Helfat (Reference Adner and Helfat2003) and Helfat and Martin (Reference Helfat and Martin2015).

Managerial cognition

The concept of cognition has been used in two ways in the management literature: mental processes and mental structures (Helfat & Peteraf, Reference Helfat and Peteraf2015). These concepts are disparate but complementary. Mental processes refer to any mental function involved in the acquisition, storage, performance, handling, processing, and use of knowledge; these can be mental activities such as attention, perception, learning, and problem-solving (VandenBos, Reference VandenBos2007). On the other hand, mental structures have been associated with several terms such as mental frames, mental models, and schemes. Nonetheless, these all denote ways of structuring the knowledge stored in the mind (Helfat & Peteraf, Reference Helfat and Peteraf2015). For this study, Bartlett's classical definition was adopted. Mental structures are representations of knowledge about an entity or situation, their qualities, and their relationships. This concept seeks to capture the abstractions that individuals have developed about the world and stored in their memory (Bartlett, Reference Bartlett1932).

In managerial cognition, it is impossible to separate structures and mental processes. For this reason, Kaplan (Reference Kaplan2011) defines it as the way in which CEOs notice and interpret changes in the organizational context, shaping their decisions and strategic actions. Observing a change and interpreting it requires both mental processes, such as perception and attention, and mental structures that managers have previously constructed. Hence, managerial cognition is used by CEOs in their managerial activities.

Managerial activities require the interpretation of the business environment and the transmission of this to other individuals in the organization. This process is described by Gioia and Chittipeddi (Reference Gioia and Chittipeddi1991), who claim that CEOs' managerial activities extend from the creation of meaning, called ‘sense-making,’ to transferring this sense to others, which is called ‘sense-giving.’ In sense-making, perception and attention to the environment are the essential cognitive processes, whereas social cognition, language, and communication are relevant in sense-giving (Helfat & Peteraf, Reference Helfat and Peteraf2015). In other words, when CEOs cope with uncertainty and environmental ambiguity, they develop mental structures that represent the internal and external environments of the organization. These structures allow them to design strategies and subsequent actions. In addition, social interactions are used to influence the creation of meaning for their peers and employees (influencing the sense-making of others) in a process of meaning transference (sense-giving).

In sense-making, CEOs face unstructured and ambiguous environmental changes that require interpretation (Plambeck, Reference Plambeck2012; Plambeck & Weber, Reference Plambeck and Weber2010). There are no opportunities or threats in the environment per se; their designation as such requires the interpretation of the CEO (Roundy et al., Reference Roundy, Harrison, Khavul, Pérez-Nordtvedt and McGee2018). Subsequent to this, CEOs transmit their interpretations to workers and other principal stakeholders responsible for mobilizing organizational resources.

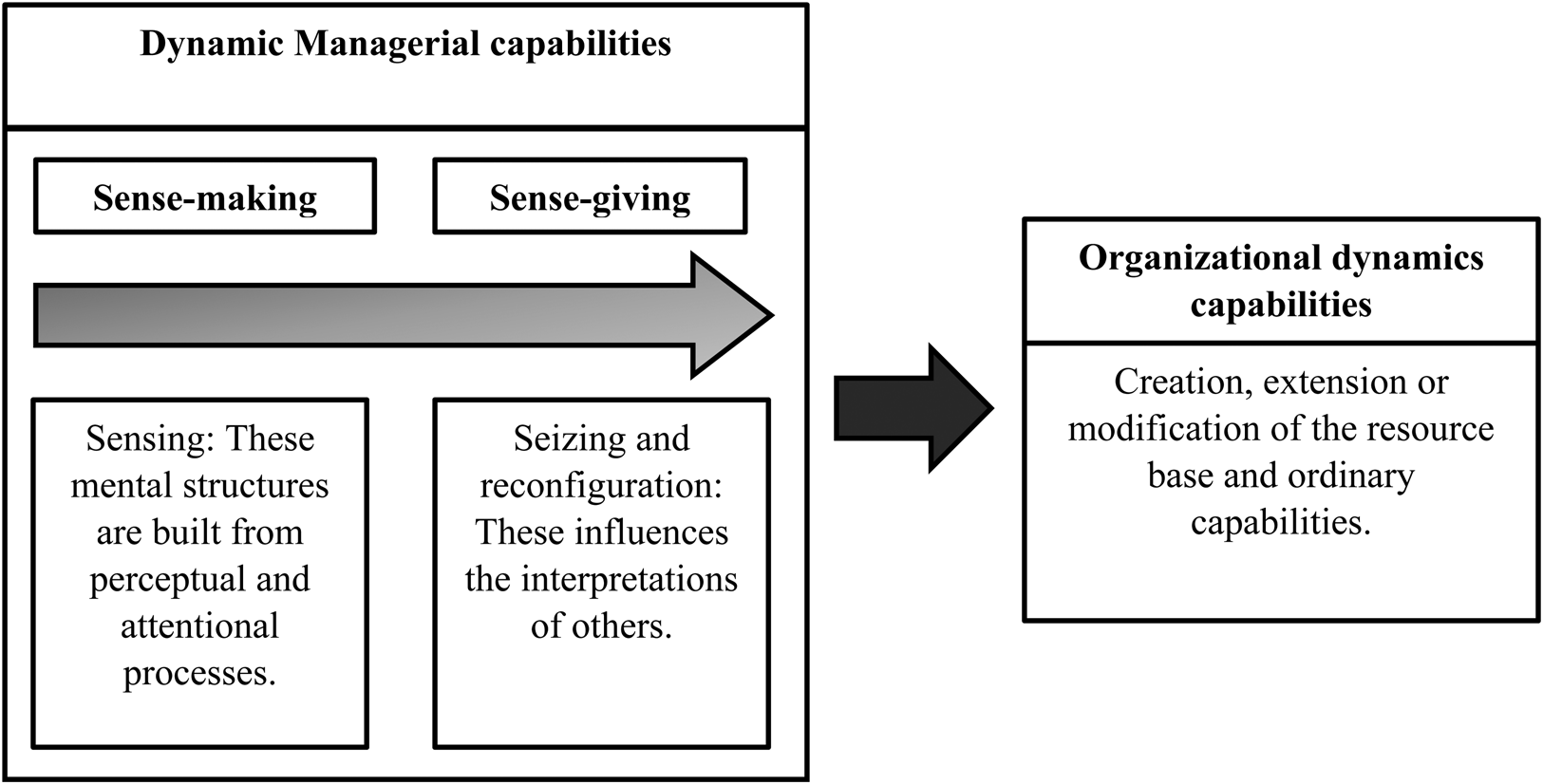

Therefore, we propose a conceptual intersection between the process described by Gioia and Chittipeddi (Reference Gioia and Chittipeddi1991) and the three dynamic managerial capabilities of Helfat and Peteraf (Reference Helfat and Peteraf2015). While managerial sensing proposed by Helfat and Peteraf (Reference Helfat and Peteraf2015) is related to the sense-making process described by Gioia and Chittipeddi (Reference Gioia and Chittipeddi1991), managerial seizing and reconfiguring match with sense-giving, which involves influencing the interpretations of others to mobilize them. This conceptual intersection reveals that dynamic capabilities have a micro-founded mechanism that is triggered by the managerial cognition. In deploying dynamic managerial capabilities, CEOs read their environment, shape or modify their mental structures from attentional and perceptual processes, mobilize firm resources, and transmit their interpretations to others, influencing the mental structures and activities of employees, thereby stimulating them for a particular purpose. Kor and Mesko (Reference Kor and Mesko2013) summarize this idea by stating that the CEO is a master ‘orchestrating’ a great symphony and that the music sheet is the mindset; Figure 2 summarizes this mechanism.

Figure 2. Mechanism to generate dynamic organizational capabilities.

Note. The figure describes the mechanism by which cognitive resources are used in dynamic managerial capabilities and in turn they generate organizational capabilities.

However, CEOs have distinct ways of creating and transmitting meaning, this is thus a source of variability within dynamic capabilities. They have unique interpretations of the environment, and different abilities to transmit information to others (Adner & Helfat, Reference Adner and Helfat2003; Helfat & Peteraf, Reference Helfat and Peteraf2015). This conceptual approach has been supported in the literature. For instance, Hambrick and Mason (Reference Hambrick and Mason1984) argue that organizations reflect the values and cognitive basis of individual CEOs. Recently, Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Wang, Zhou and Jiang2018) stated that CEOs' design strategies are based on their cognitions and perceptions. It is subsequently crucial to understand how these cognitions enable them to adopt particular strategies.

Nonetheless, the role of managerial cognition in each managerial dynamic capability is different. We propose that each kind of managerial dynamic capability is supported by different cognitive variables. In managerial sensing, perceptual and attentional processes are relevant, since they allow the sense-making process of environmental changes (Helfat & Peteraf, Reference Helfat and Peteraf2015). Baron (Reference Baron2006) points out that pattern recognition is a key cognitive element in sensing opportunities and threats, and that this is the outcome of CEOs' perceptual process. However, these patterns depend on the mental model previously structured. The timely identification of patterns can translate into a competitive advantage for organizations by capturing an environmental signal before their competition does.

Consequently, it is expected that cognitive resources that support CEOs' managerial sensing enable them to focus on abilities to detect opportunities and threats in the environment, which would be expected to further develop dynamic capabilities in their organizations. This argument leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Cognitive variables to support managerial sensing are significantly related to the development of dynamic capabilities.

In the case of managerial seizing, Helfat and Peteraf (Reference Helfat and Peteraf2015) state that problem-solving is an important cognitive process, given that it allows the coupling of resources and distinct ways of facing environmental demands. Likewise, the tendency to think quickly by applying heuristic rules or to think slowly with more complex processes affects the time needed to adequately respond to environmental challenges, as well as biases in the decision-making process (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011).

Following this argument, Wiesenfeld, Reyt, Brockner, and Trope (Reference Wiesenfeld, Reyt, Brockner and Trope2017) ascertain that the level of abstraction used by CEOs in strategy planning influences goals. If the level of abstraction is high, the mental model will be more complex and the goals set will be of greater value; that is, greater time and effort will be needed. Conversely, if the level of abstraction is low, short and quick goals will be set. Thus, the abstraction level of CEOs' mental model is related to the strategies used to mobilize organizational resources.

Therefore, it is expected that the cognitive resources of CEOs that support the managerial seizing capability will be related to the mobilization of organizational resources to exploit opportunities. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2: Cognitive variables to support managerial seizing are significantly related to the development of dynamic capabilities.

Finally, in managerial reconfiguration, mental structures regarding the sustainable coordination of resources and capabilities to maintain a competitive advantage have the greatest importance. The case of Polaroid illustrates this point. Although Polaroid was an organization with extraordinary capacities, as a market leader with access to multiple resources, it was close to going bankrupt because of the CEO's interpretation of the effect of digital technology on the photographic camera market (Tripsas & Gavetti, Reference Tripsas and Gavetti2000). Mental structures that allow CEOs to understand current and future environmental demands allow them to align organizational resources and keep sustainable advantages in the market. Consequently, a final hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3: Cognitive variables to support managerial reconfiguration are significantly related to the development of dynamic capabilities.

Methodology

Sample

A search was performed in WOS, Scopus, Proquest, and EBSCO for quantitative papers published in peer-reviewed journals related to business and management. The search included papers up to May 31, 2021.

Figure 2 summarizes the selection process through three filters. First, abstracts, titles, and keywords were reviewed. It was not mandatory that the abstract used the word ‘cognition.’ Other terms such as ‘perception,’ ‘attention,’ ‘reasoning,’ ‘problem-solving,’ ‘mental schema,’ and ‘mental model’ were also admissible. The use of the term ‘organizational capability’ was not imperative, therefore, words such as ‘organizational capacity,’ ‘organizational learning,’ ‘innovation,’ ‘absorption capacity,’ ‘organizational strategy,’ ‘strategic renewal,’ and ‘competitive advantage’ were admitted.

After the first filter, 270 papers were selected. The papers were read in depth to identify whether they adhered to the following inclusion criteria. First, the managerial cognitive measure had to be in relation to the CEO or decision maker. Measures of medium or low decision makers were excluded. Second, managerial cognitive variables had to be individual. All team variables such as shared cognition or team mental models were excluded. To this end, researchers read the definition and operationalization of the variables to make a decision. Finally, papers had to provide the Pearson correlation between CEOs' cognitive variable and organizational capacity. If this correlation was not given, the paper was removed. Regression models or dichotomous correlations were excluded. Using this filter, there was no guarantee that organizational capability was dynamic; this was completed using the next filter.

After completing these processes, 69 papers were selected but not all were used in the meta-analysis, given that only some of them measured dynamic capabilities. Two external reviewers assessed whether these papers measured this variable. Reviewers were trained and used in the following classification criteria.

First, papers had to report a measure of dynamic capability, excluding measures of ordinary capabilities. No measure of financial performance was allowed as an indicator of an underlying dynamic capability, following recommendations by Laaksonen and Peltoniemi (Reference Laaksonen and Peltoniemi2018), since this is a non-valid measurement of organizational capabilities and is supported by tautological reasoning. Improving on performance is not a measure of dynamic capabilities. Second, Helfat et al.'s (Reference Helfat, Finkelstein, Mitchell, Peteraf, Singh, Teece and Winter2009) definition of the concept of dynamic capability was used. Consequently, any measure of creation, expansion, or modification of the resource base was accepted. This validation test had an agreement coefficient of .83, according to Cohen's kappa index (Cohen, Reference Cohen1992). The measures of creation included the acquisition of new resources, alliances, innovation, and entrepreneurial activities; the measures of expansion included all of the extension of resources owned by the firm; and the measures of modification included changes in the business such as products, processes, flexibility, and business model.

The studies selected were reviewed by two experts in organizational strategy. They assessed whether the variables utilized in the papers were measures of dynamic capabilities. They also classified the dynamic capabilities in the three categories proposed by Teece (Reference Teece2007): sensing, seizing, and reconfiguration; this exercise achieved a Cohen's kappa index of .89. The final pool comprised of 27 papers, published between 2007 and 2021. Samples of CEOs used in the papers were from companies located in China, Ghana, New Zealand, Poland, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, South Korea, and the USA (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Flowchart selecting papers.

Note. Selection of papers analyzed using the flowchart PRISMA template.

Coding process

In each paper, bibliographical and methodological information (design, sample size, and measurement reliability) was extracted, with descriptive variables of the sample (about both the CEOs and the organizations), and the Pearson correlation between managerial cognition and dynamic capability was calculated.

Some variables were categorized to facilitate moderation analysis. Firm size was classified according to the European Union's taxonomy used in reports to the OECD (OECD Observer, 2000). Having fewer than 250 employees characterized small and medium enterprises (SMEs), and 250 or more employees characterized large organizations. Industrial sectors were categorized for technological dynamism. High dynamism sectors were characterized by fast technological change, higher spending on R&D, and more knowledgeable workers. They had higher levels of turbulence and emerging ideas to break the market (Simerly & Li, Reference Simerly and Li2000). Papers with samples in biotechnology, information and telecommunications, and hardware and software were classified as high dynamism. If a paper used samples from various sectors, the highest percentage of the sample in either high or low dynamism was used for the classification. The age of the CEO and the length of time that their firm had been in the market were analyzed as quantitative variables, whereas factors such as the sample country, firm size, sampling (random or not random), methodological design (cross-sectional or longitudinal), data collection (archive or self-report), and level of dynamism in the sector (high or low dynamism) were categorical.

Classification of cognitive variables

Three judges with expertise in organizational strategy and psychology carried out the classification of managerial cognitive variables in the three dynamic managerial capabilities. They hold PhDs in psychology, teaching, and research in management, respectively. Seventeen cognitive managerial variables were identified in the papers selected. The classification was performed three times, and the results were discussed consecutively to improve the classification. Finally, by using the Kappa Fleiss index, a rate agreement of .81 was achieved in the third round (Fleiss, Nee, & Landis, Reference Fleiss, Nee and Landis1979).

Data analysis

The Pearson's correlation coefficient between cognitive variables and dynamic capabilities was used as the effect size. Every correlation was corrected for reliability using the Hunter and Schmidt (Reference Hunter and Schmidt2004) procedure. However, archive data and non-obtrusive measures (indirect) did not report reliability values. In the first case, archive data were imputed by the common parameter of reliability of .8 followed in the management literature (Dalton, Daily, Certo, & Roengpitya, Reference Dalton, Daily, Certo and Roengpitya2003; Jiang, Lepak, Hu, & Baer, Reference Jiang, Lepak, Hu and Baer2012). The second, non-obtrusive measure was imputed using the average of reliabilities reported in the managerial capability to which the measure belonged.

A three-level random effects model was applied to synthesize the correlations (Cheung, Reference Cheung2014) inasmuch as each paper reported two or more effect sizes, which would violate the assumption of independence (Hunter & Schmidt, Reference Hunter and Schmidt2004). The three-level model overcomes this problem by estimating two sources of variance: inter-study and intra-study (Cheung, Reference Cheung2014; Van den Noortgate, López-López, Marin-Martinez, & Sánchez-Meca, Reference Van den Noortgate, López-López, Marin-Martinez and Sánchez-Meca2013; Wibbelink, Hoeve, Stams, & Oort, Reference Wibbelink, Hoeve, Stams and Oort2017). As a result, each correlation reported can be analyzed as a distinct effect without averaging the values of the same paper. The ‘metafor’ R package (Viechtbauer, Reference Viechtbauer2010) was used according to the tutorial by Assink and Wibbelink (Reference Assink and Wibbelink2016), which elaborates upon the use of the three-level model.

Once the analysis was completed, we built a structural equation model with meta-analytic data. This entailed a post-hoc analysis using the significant correlations identified. We used the univariate approach proposed by Viswesvaran and Ones (Reference Viswesvaran and Ones1995), conducting several univariate meta-analyses for each value of the correlation matrix. This matrix was used to estimate a structural model using the Lavaan package (Rosseel, Reference Rosseel2012). The sample size used in the model was the harmonic mean of the samples reported in the papers (n = 134).

Results

The database search identified 27 published articles and 101 correlations from 2007 to 2021, representing 6,153 CEOs. Table 1 summarizes bibliographic information, the country in which the research was conducted, sample size, cognitive variable, and dynamic capability measured.

Table 1. Studies used in the meta-analysis

Note. The complete reference of the items is in the list of references marked with *.

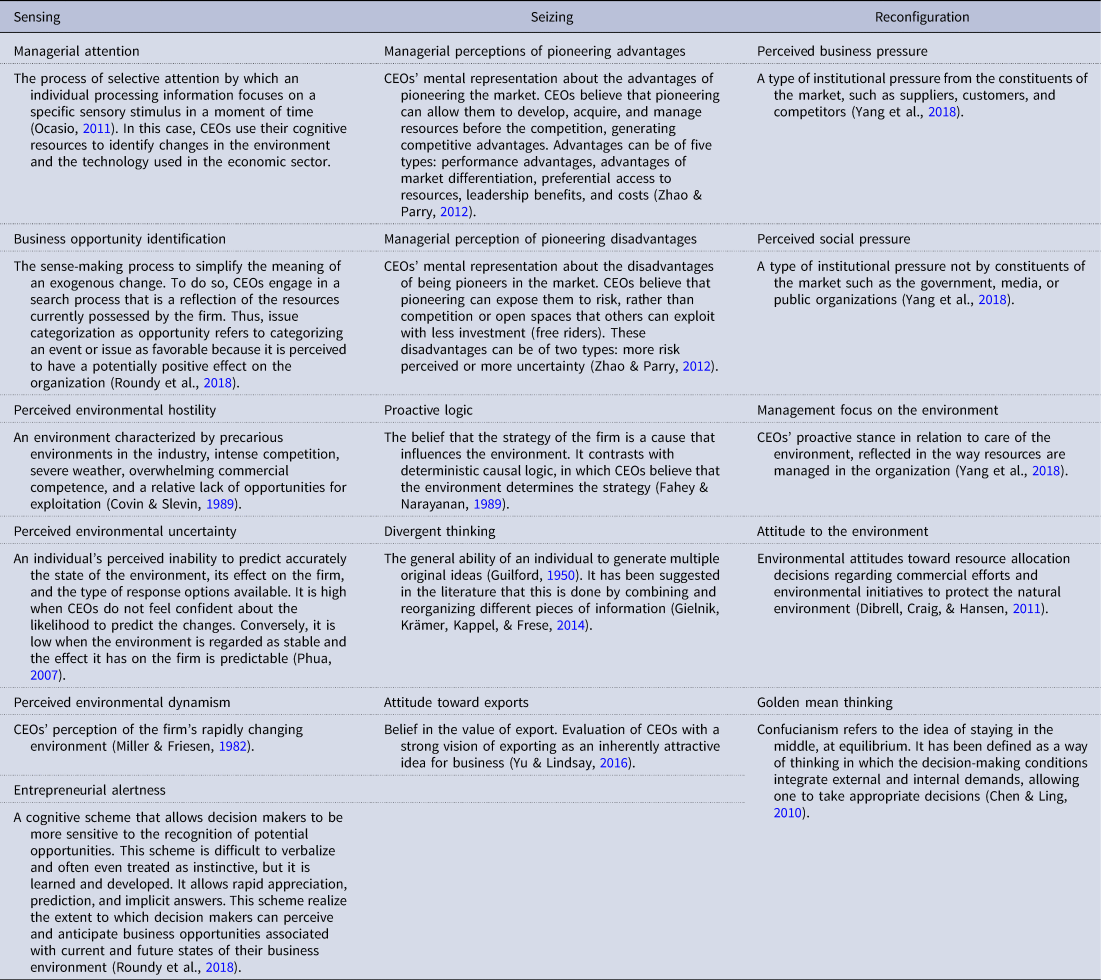

After careful consideration, an inter-judge agreement exercise was used to classify the cognitive variables in the three types of dynamic managerial capabilities. Table 2 illustrates each definition of the cognitive variables and their respective classifications.

Table 2. Classification of cognitive variables

Note. Definitions are extracted from the articles identified in the systematic search of databases.

The conceptual guides by Helfat and Peteraf (Reference Helfat and Peteraf2015) exploring managerial capacities were used in the classification process. Managerial sensing is CEOs' capacity to scan the environment to recognize opportunities or threats in an unstructured and uncertain context. The support of this managerial capacity is the ability to interpret information (Helfat & Peteraf, Reference Helfat and Peteraf2015). Based on this conceptual scope, the cognitive variables associated with scanning the environment or interpreting environmental changes were classified as cognitive resources of managerial sensing.

As Helfat and Peteraf (Reference Helfat and Peteraf2015) highlighted, perception and attention should be part of this managerial capacity, since they are the psychological processes responsible for scanning and interpreting the environment. Consequently, we observed that the cognitive variables in this category are perceptual or attentional processes. The variables identified were managerial attention, perceived business opportunity, perceived environmental hostility, perceived environmental uncertainty, perceived environmental dynamism, and entrepreneurial alertness.

Managerial seizing is defined by Helfat and Peteraf (Reference Helfat and Peteraf2015) as the ability of CEOs to develop new products, processes, or services to take advantage of the opportunities. Therefore, CEOs develop a business model that strategically exploits the opportunity and investment resources. If the focus of managerial sensing is the interpretation of the environment, then the seizing is the mobilization of resources to take advantage of opportunities or threats identified.

Cognitive variables to support managerial seizing are mental structures that enable or inhibit the exploitation of opportunities, so they are particular ways in which CEOs approach opportunities. These refer to unique belief systems that affect the probability of mobilizing the organization's resources to exploit opportunities. Depending on their content, these cognitive variables enable or obstruct the mobilization of resources. An additional mention should be made of divergent thinking, a cognitive variable also classified as a resource of managerial seizing. Divergent thinking is not a belief system, but a style of thinking enabling the rise of original ideas that could be transformed into innovations and market advantages. This would be the support of alternative business models that exploit opportunities. Thus, cognitive variables in this category were managerial perceptions of pioneering advantages, managerial perceptions of pioneering disadvantages, proactive logic, divergent thinking, and attitude toward exports.

Finally, managerial reconfiguration is CEOs' ability to align tangible and intangible strategic assets that enable growth and sustainable profit. It refers to CEOs' capacity to ‘orchestrate assets,’ which involves the selection, configuration, alignment, and modification of tangible and intangible assets for a strategic purpose (Kor & Mesko, Reference Kor and Mesko2013; Sirmon & Hitt, Reference Sirmon and Hitt2009). In this category, we classify cognitive variables that support beliefs about the match between organizational resources and environmental changes. However, golden mean thinking is different. This variable has been studied by academic researchers in China; it refers to the ‘golden rule’ proposed in Confucianism for seeking balance and moderation, avoiding extremes. Moreover, it has been classified in this category because it captures CEOs' capacity to integrate external conditions and internal demands, thus maintaining a balance. In sum, the variables classified as resources of managerial reconfiguration were perceived pressure, perceived social pressure, management focus on the environment, attitude to the environment, and golden mean thinking.

The complexity of CEOs' mental models is a variable unclassified in any managerial capacity because it transverses all of them. This variable captures the breadth and variability that the CEOs' mental structure has over its context, commonly understood by the presence of many concepts and their interrelationships. They are usually studied with mind maps in which the CEOs depict concepts and the relationships between them. This variable was not included in any managerial capacity and was meta-analyzed independently.

On the other hand, we identified several dynamic capabilities, such as pioneering, absorption capability, strategic change decisions capability, diversification, innovation, capability of firm change, flexibility, organizational ambidexterity, firm-level entrepreneurship, and the speed of strategic response. These capabilities demonstrate the organizational capacity to explore the business environment and change internal resources and ordinary capabilities. In the next section, we describe the correlations between cognitive variables and these dynamic capabilities.

Meta-analysis

Correlation between CEOs' managerial cognition and dynamic capabilities was significant and positive, r(101) = .18, p < .001, 95% confidence interval [.08, .28], with a higher heterogeneity in both inter-studies = .024, p < .001, I 2 = 37.87%, and intra-studies = .036, p < .001, I 2 = 56.10%. There was a small positive relationship between CEOs' cognitive variables and dynamic capabilities according to Cohen (Reference Cohen1992). There was no evidence of publication bias using the Egger, Smith, Schneider, and Minder (Reference Egger, Smith, Schneider and Minder1997) procedure; the intercept did not significantly deviate from zero, z = −.21, p = .83.

This correlation should be carefully interpreted because it aggregates the differential effects of the cognitive variables in each managerial dynamic capability. Table 3 summarizes the results in each managerial capability and the cognitive variables that support them.

Table 3. Results of the meta-analysis

Note. To calculate the correlation in sensing and seizing the negatives variables perception of hostility and pioneering disadvantages were reversed. Using ‘–’ indicates no value calculated.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

As an additional robustness check, we explore the differences among the measures of creation, expansion, and modification. We identify 50 measures of creation, 19 measures of expansion, and 32 of modification. A comparison among them did not show any significant differences, F(2, 98) = .4816; p = .6193 [r_create = .165; r_extend = .280; r_modify = .160].

Dynamic managerial capability of sensing

The cognitive variables to support the managerial capability of sensing showed a significant positive correlation with the dynamic capabilities, r(61) = .19, p < .001, which supports hypothesis 1. Those organizations managed by CEOs with greater resources to identify opportunities and threats showed more dynamic capabilities. Additionally, there was no evidence of publication bias, z = .77, p = .44.

This correlation was supported by variables involved in the identification of opportunities, such as the perception of business opportunities and entrepreneurial alertness, while the variables related to the negative perception of changes, such as perceived environmental hostility, were not significant. The perception of business opportunities, r(15) = .34, p < .001, and entrepreneurial alertness, r(5) = .39, p = .028, had a moderate effect, hence the environmental changes interpreted as opportunities are associated with greater dynamic capabilities.

Variables related to the prediction of environmental change were significant. The perceived environmental uncertainty, r(17) = .08, p = <. 001, and the perceived dynamism, r(11) = .09, p = .033, exhibited a small positive relationship. Therefore, environmental changes with unpredictable effects could force CEOs to strengthen their dynamic capabilities as a strategy to improve control and decrease ambiguity.

Managerial attention did not show any significant effect, r(8) = .26, p = .072. However, this result must be interpreted with caution because of the non-obtrusive measures used in the studies of managerial attention, namely the word count in the letters that CEOs send to stakeholders, because they lack evidence of validity.

Finally, as noted previously, the perception of hostility, r(5) = −.03, p = .824, did not have any significant effect on dynamic capabilities, so negative perception of the environment does not strengthen or weaken the dynamic capabilities of the organization.

Dynamic managerial capability of seizing

The cognitive variables to support the managerial capability of seizing had a positive and significant effect, r(30) = .15, p = .007. Hypothesis 2 was thus supported. Specifically, CEOs that typically had more resources to seize opportunities showed more dynamic capabilities in their firms. Again, there was no evidence of publication bias, z = .38, p = .710.

The analysis of the cognitive variables individually revealed that the managerial perception of pioneering disadvantages had a significant effect, r(6) = −.18, p < .001. Meanwhile, the managerial perception of pioneering advantages, r(16) = 14, p = .139, proactive logic, r(3) = .08, p = .688, and managerial attitude toward exports, r(4) = .24, p = .196, did not have any significant effect. Divergent thinking had only one effect reported, so it was not possible to calculate any intervals or significance tests.

Dynamic managerial capacity of reconfiguring

The cognitive variables to support the managerial capability to reconfigure also had a positive, small, and significant effect, r(5) = .19, p = .016, so that higher cognitive resources were associated with more dynamic capabilities, thus supporting hypothesis 3. A study publication bias was conducted, but no evidence was found of this, z = 1.61, p = .107. In this case, it was not possible to analyze each cognitive variable comprising this capability because there was only one effect for each variable; it was also not possible to calculate any intervals or significance tests.

The analysis of CEOs' strategic mental model complexity, a cross-cognitive variable at the three managerial capacities, was not significant, r(5) = −.46, p = .273. Furthermore, although the estimated correlation value was higher than other cognitive variables, it had few correlations reported among papers.

Finally, we studied the differential effect on the three types of dynamic capabilities. Managerial sensing had a significant correlation with sensing, r(17) = .23, p = .002, and seizing, r(22) = .18, p = .008, but it was not significant with reconfiguration, r(22) = .170, p = .385. On the other hand, managerial seizing was not significantly correlated with sensing, r(2) = .34, p = .443, but it was correlated with seizing, r(27) = .14, p = .044. We had only one correlation between managerial seizing and reconfiguration that impeded the estimation. Lastly, we are also unable to estimate the association between managerial reconfiguration with sensing and reconfiguration. We did not find correlations between managerial reconfiguration with sensing, and we had only one correlation between managerial reconfiguration with reconfiguration. In the case of managerial reconfiguration, we could only estimate the correlation with seizing that was not significant, r(4) = .19, p = .080.

Post-hoc analysis

As a final analysis, we built a model to integrate the significant correlations identified. As a result, we use four variables in the model: managerial sensing, managerial seizing, sensing, and seizing. Managerial reconfiguration and reconfiguration were not used in the model because they were not significantly correlated or had no correlation reported with sensing and reconfiguration. Figure 4 displays the results thereof.

Figure 4. Post-hoc analysis.

Note. Direct effect of managerial sensing on seizing was significant β = .18, but the effect disappear in the model. There is a total mediation effect. Indirect effect = .069, z = 2.048, p = .043. *p < .05, ***p < .001.

We found evidence of a total mediation of managerial sensing on seizing through sensing. Managerial sensing had a significant direct effect on sensing, β = .19, p = .023, and a significant indirect effect on seizing, β = .069, p = .043. The previously described direct effect of managerial sensing on seizing disappeared in the mediation analysis. In contrast, managerial seizing was not significant on sensing, β = .16, p = .058, or seizing, β = .11, p = .155. Again, the direct effects of managerial seizing on seizing demonstrated in the previous analysis disappear in the model. Additionally, according to Teece (Reference Teece2007), there is a continuity process among sensing and seizing. This direct effect was significant, β = .36, p < .001, in the analysis. Finally, there are no conceptual reasons to establish a direct effect between managerial sensing and managerial seizing. Consequently, we study their covariance. We did not find evidence of an association between managerial sensing and managerial seizing; the estimated value was not significant, ϕ=.060, p = .488.

Moderation analysis

Managerial sensing and managerial seizing showed heterogeneity in their correlations, so it was imperative to explore the inter- and intra-study variances with a moderation analysis. Tables 4 and 5 summarize the results by categorical variable moderation, and the quantitative moderators are reported in the text.

Table 4. Moderation in managerial sensing capability

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Table 5. Moderation in managerial seizing capabilities

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

We did not find evidence of moderation on managerial sensing; no variable reported in Table 4 turned out to be significant. Quantitative moderators, age of the CEO [F(1, 28) = 1.11; p = .309], and organizational age [F(1, 51) = .33; p = .566] did not have a significant effect. In contrast, the moderation analysis in the managerial capability of seizing learned that the type of data collected had a moderating effect, F(1, 29) = 4.88, [r_Archive = −.15; –r_Self-report = .17], p = .047. However, this result requires careful interpretation, given that 29 correlations used self-report and only one used archive data. Regarding quantitative moderators, it was only possible to test the age of the CEO [F(1, 14) = .56; p = .465], which did not show any significant effect.

Discussion

Since managerial cognition is a broad conceptual category with several variables, in this study we have organized CEOs' managerial cognition variables as reported in the literature in three types of dynamic managerial capabilities called managerial sensing, managerial seizing, and managerial reconfiguring. We argue that CEOs' managerial cognition supports these dynamic managerial capabilities. Furthermore, we have estimated the association of each cognitive variable and each dynamic managerial capability with firms' dynamic capabilities. Subsequently, we discuss the findings of each dynamic managerial capability.

First, managerial cognition to support managerial sensing is significantly associated with the development of dynamic capabilities. Four of the cognitive variables that support it were significant. Moreover, this category is the most widely studied in the literature since over 60% of the correlations analyzed correspond to this managerial capability. Managerial sensing is composed of perceptual variables that allow the interpretation of environmental changes (Plambeck, Reference Plambeck2012; Plambeck & Weber, Reference Plambeck and Weber2010). These variables allow CEOs to interpret the environmental changes as opportunities or threats. According to the results, three types of interpretations of the environment could be performed by the CEOs: those focused on the positive interpretation, those that interpreted the environment as uncertain, and the negative interpretation of the environment.

Concerning the first type of interpretation, we can assert that it is a better strategy for the CEOs ‘to see the glass [as] half full’ by building positive interpretations around the environment as they are positively associated with the development of dynamic capabilities. Implementing the managerial sensing capability relies on perceptual processes, especially those that identify environmental opportunities such as business opportunity identification and entrepreneurial alertness. In the second type of interpretation, we found that the variables related to the uncertainty of the environment, including perceived environmental uncertainty and perceived dynamism. When CEOs perceive the environment as uncertain, they are motivated to activate the mechanism depicted by Bendig et al. (Reference Bendig, Strese, Flatten, da Costa and Brettel2018), increasing the firm's dynamic capabilities. Finally, the negative interpretations of the environment are not associated with dynamic capabilities.

The cognitive variables to support the managerial capability of seizing are significantly associated with the development of dynamic capabilities. However, the estimated correlation was lower than the other managerial capabilities. Only the managerial perception of pioneering disadvantages proved to be significant. This result has two readings. On the one hand, although CEOs' managerial cognition triggers the micro-founded mechanism to foster dynamic capabilities (Bendig et al., Reference Bendig, Strese, Flatten, da Costa and Brettel2018), contribution to managerial seizing is relatively unimportant, given that it does not account for the ability to mobilize resources. As Gioia and Chittipeddi (Reference Gioia and Chittipeddi1991) pointed out, sense-making is not sufficient inasmuch as a process of sense-giving is needed to mobilize other individuals, and this process is not captured by CEOs' cognitive variables. It requires other approaches that involve social interactions and leadership skills. On the other hand, the second reading of this result highlights that the focal task of managerial seizing is enabling or inhibiting resource mobilization. In our analysis, we show evidence of the inhibition function of managerial seizing related to delaying resource commitment, but we cannot identify any cognitive variable related to this enabling function. We encourage future research to study additional cognitive variables related to the enabling process. For instance, Helfat and Peteraf (Reference Helfat and Peteraf2015) propose that problem-solving is a relevant variable in managerial seizing but there is not sufficient evidence to support this hypothesis. Moreover, as we describe in the results, divergent thinking has only been reported in the literature once, therefore, we cannot discard its association with dynamic capabilities.

Finally, the cognitive variables to support the reconfiguration are related to dynamic capabilities, although it is less commonly explored in the literature as a category. Discussions about reconfiguration are limited by the few studies exploring it; therefore, the cognitive approach to the reconfiguration is thus a gap in the literature. We also suggest a different approach regarding these findings. Extant efforts in the literature have been focused on sensing and seizing because CEO involvement in the reconfiguration is lower. Thus, it concerns top and middle managers, whereas CEOs have a non-direct effect on reconfiguration. These assertions require additional research to identify the role of the CEO in reconfigurations. Nonetheless, based on the current state of the research and the findings of this meta-analysis, we ascertain that CEOs' comprehension of the current and future challenges of the environment influence the enhancing, combining, protecting, and reconfiguring of business assets. In addition, the strength of its correlation is similar to managerial sensing, indicating the active role of CEOs.

The analysis of the association of the dynamic managerial capabilities with the three types of dynamic capabilities reveals additional details. Managerial sensing had a significant relation with sensing and managerial seizing was related to seizing. Unfortunately, we cannot offer support for the relationship between managerial reconfiguration and reconfiguration because only one correlation was reported in the papers. Nonetheless, an overall analysis of the associations between managerial capabilities and dynamic capabilities using the structural model shows the relevance of managerial sensing. Indeed, it had a direct effect on sensing but an indirect effect on seizing, while the effect of managerial seizing disappeared. From the cognitive approach the relevance of managerial sensing in the development of dynamic capabilities is manifested. It can be understood as a sign of the relevance of the CEOs in the interpretation of the environment, therefore, CEOs' core task is to filter external information and make sense of it.

In Figure 5, we propose an integrative model of the findings and draw two research lines regarding dynamic managerial capabilities. Both depicted dynamic managerial capabilities as triggers of the underlying mechanism proposed by Bendig et al. (Reference Bendig, Strese, Flatten, da Costa and Brettel2018). In line with managerial sensing, there are a robust number of cognitive variables to support it and an association with sensing and seizing. On the other hand, managerial seizing has only one cognitive variable to support it; we also found an association with seizing. Again, we highlight the absence of studies regarding to reconfiguration, thus impeding its description.

Figure 5. Integrative model of the findings.

Note. This model summarizes the main findings of the meta-analysis. Dynamic managerial capabilities are supported by the cognitive variables that were significant. Managerial reconfiguration is not represented because it has insufficient studies.

Finally, moderators did not show evidence of an effect on both managerial sensing and managerial seizing. To discuss this result, we have classified the set of moderators explored into two categories: moderators addressed by the theory and methodological moderators. In the set of moderators addressed by the theory, we explored firm size and environmental dynamism because only they offer the information needed to conduct a heterogeneity analysis; however, we can also suggest other moderator variables that were not explored in this research. Firm size and environmental dynamism are distant from the CEOs and their effects on managerial cognition could be mediated by variables closer to them. Hence, we suggest that variables closer to CEOs, such as age, gender, educational degree, or labor experience, could offer support in the explanation of intra-study heterogeneity. In this sense, we assert that a possible source of variability lies within the same concept of dynamic managerial capabilities. As Adner and Helfat (Reference Adner and Helfat2003) state, the social capital and human capital of CEOs are two additional resources to support dynamic managerial capabilities (Durán & Aguado, Reference Durán and Aguado2022; Lee & Yang, Reference Lee and Yang2014). Therefore, it is relevant to explore their interaction with managerial cognition. At an individual level, human capital variables could be a plausible option to identify moderators because changes in the experience and skills of CEOs could be associated with changes in managerial cognition. The social capital of CEOs could also interact with cognitive variables and modify their effects because it is a source of strategic information that transforms the point of view of the CEOs.

In contrast, there do not seem to be any additional methodological moderators to explore. The set of moderators explored in this study cover relevant factors of the methodology of the studies included. We can assert that the explanation of intra-study heterogeneity detected is associated with moderators, as addressed by the theory.

Limitations

This meta-analysis is not without its limitations. First, the studies included were correlational, thus it is not possible to establish cause–effect inferences. Furthermore, the studies analyzed use cross-sectional designs and have the same source for independent and dependent variables, further compounding its inability to make causal inferences. In addition, the results cannot discount reverse causality between the variables, in that dynamic capabilities improve managerial cognition variables, inasmuch as CEOs have a learning context with experiences, information, and feedback that strengthen their capabilities. Understanding and addressing the impact of this issue requires more robust research designs.

Second, it was not possible to account for variability in managerial sensing, seizing, and reconfiguration with the moderating variables used; other variables would need to be identified to explain this heterogeneity. Finally, the studies in the sample are biased toward the USA and China; other areas such as Europe, Africa, and Latin America are not adequately represented in the results. Different countries' macro-economic conditions might impact key findings and, again, this warrants attention. And third, we have studied the first and the last ties of the causal mechanism depicted by Bendig et al. (Reference Bendig, Strese, Flatten, da Costa and Brettel2018); however, the micro-employee level is not analyzed.

Theoretical implications

The main theoretical contribution of this study is the identification and organization of CEOs' cognitive variables, as reported in the literature. This contribution allows the construction of a conceptual framework that recognizes that cognitive variables are incomparable between them because they have dissimilar functions. With an overall view of the cognitive variables studied in the literature, we have identified gaps for future research. Three gaps are evident: the cognitive variables related to the enabling processes in managerial seizing, additional cognitive variables to support managerial reconfiguration, and the association between managerial reconfiguration with the firm's reconfiguration. In addition, the classification of the cognitive variables contributes to solving the ambiguity present in the empirical results in the literature. CEOs' managerial cognition does not exhibit contradictory results; there are several variables that are positive, negative, or unrelated to different types of dynamic capabilities. For instance, we have shown that positive interpretations of the environment are related to the development of dynamic capabilities; in contrast, negative interpretations are not related.

A third theoretical implication is the approach to dynamic managerial capabilities as a formative construct. As organizations exploit their capacities to transform resources in products, CEOs use their managerial capabilities to transform their individual resources to perform their institutional tasks. Therefore, since managerial cognition is a resource, scholars can explore the origin of these resources and identify how they can be best leveraged, optimized, and increased. This study also contributes to the identification of the sources of dynamic capabilities. Our results offer evidence that variables at an individual level have a relationship with organizational capabilities. Hence, sources of dynamic capabilities might be explored at an individual level. Nonetheless, a microfoundations approach does not ignore interactions with organizational variables, but they are moderators or conditions that modify the effects of individual and team variables.

Finally, although this study summarizes the managerial cognitive variables explored in the literature, it does not represent all the possible cognitive variables that could be studied. Emotional variables have not been explored, and therefore emotional regulation, moods, and emotional traits need to be studied, correspondingly. Likewise, other cognitive variables such as reasoning, meta-cognition, memory, and decision bias need to be investigated.

Practical implications

This study offers two main practical contributions. First, CEOs' comprehension of the environment is related to organizational adaptation. Following this line of study, investments in training and other ways to update CEOs' mental structures enable sense-making changes and generate a new understanding of the environment. The second contribution addresses CEOs in SMEs. Managerial cognition has a prominent effect on SMEs because they lack other resources; therefore, CEOs' comprehension is a cornerstone of organizational adaptation. If CEOs do not understand the business environment, especially in SMEs, they are operating blindly in the market. In sum, updating CEOs' mental structures that account for environmental changes is a good strategic decision to improve organizational adaptation.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis organizes the managerial cognitive variables reported in the literature and estimates their correlation with dynamic capabilities. This endeavor sheds light on the state of the art in this domain, furthering collective understandings. Managerial cognition is a source of variability in the development of dynamic capabilities, especially those cognitive variables that support managerial sensing.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2022.24

Financial support

This study was supported by the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana and Administrative Department of Science, Technology and Innovation (Colciencias) in Colombia.

Conflict of interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.