Introduction

Workplace gossip is described as ‘informal and evaluative talk from one member of an organization to one or more members of the same organization about another member of the organization who is not present to hear what is said’ (Brady, Brown, & Liang, Reference Brady, Brown and Liang2017, p. 3). It typically involves the details that are not confirmed as true (Foster, Reference Foster2004; Kuo, Chang, Quinton, Lu, & Lee, Reference Kuo, Chang, Quinton, Lu and Lee2015). Negative workplace gossip (NWG) is a more sensitive form of gossip (Grosser, Lopez-Kidwell, Labianca, & Ellwardt, Reference Grosser, Lopez-Kidwell, Labianca and Ellwardt2012).

Although some receivers of gossip could benefit from the gossipers from reflective learning (Bai, Wang, Chen, & Li, Reference Bai, Wang, Chen and Li2020), NWG is lumped together with behaviors such as berating someone, sabotaging someone's work, and giving the silent treatment (Tepper & Henle, Reference Tepper and Henle2011). Therefore, it gives rise to a range of adverse outcomes. The targets of NWG suffer emotional distress or job distress (Şantaş, Uğurluoğlu, Özer, & Demir, Reference Şantaş, Uğurluoğlu, Özer and Demir2018; Wu, Kwan, Wu, & Ma, Reference Wu, Kwan, Wu and Ma2018b) and reputation damage (Rooks, Tazelaar, & Snijders, Reference Rooks, Tazelaar and Snijders2011). Moreover, the NWG could hinder target employees' proactive behavior (Wu, Birtch, Chiang, & Zhang, Reference Wu, Birtch, Chiang and Zhang2018a, Reference Wu, Kwan, Wu and Ma2018b) and organizational citizenship behavior (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Birtch, Chiang and Zhang2018a), even leading to revenge against the organization (Şantaş et al., Reference Şantaş, Uğurluoğlu, Özer and Demir2018). The organization with NWG is also suffused by disharmony, hostility, and hate (Grosser et al., Reference Grosser, Lopez-Kidwell, Labianca and Ellwardt2012; Şantaş et al., Reference Şantaş, Uğurluoğlu, Özer and Demir2018).

Knowing these implications mentioned above for workplaces, this negative talk (NWG) needs to be discouraged or even banned (Grosser et al., Reference Grosser, Lopez-Kidwell, Labianca and Ellwardt2012; Tassiello, Lombardi, & Costabile, Reference Tassiello, Lombardi and Costabile2018). Recently, many studies have increasingly suggesting that managers should improve their management skills to reduce NWG spreading (Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Chang, Quinton, Lu and Lee2015; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Birtch, Chiang and Zhang2018a, Reference Wu, Kwan, Wu and Ma2018b). Unfortunately, little previous research has systematically explored the relation between leaders and NWG (Brady, Brown, & Liang, Reference Brady, Brown and Liang2017; Kim, Moon, & Shin, Reference Kim, Moon and Shin2019; Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Chang, Quinton, Lu and Lee2015; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Birtch, Chiang and Zhang2018a) and provided theoretical explanations and empirical evidence for coping with NWG occurrence (Kim, Moon, & Shin, Reference Kim, Moon and Shin2019). Also, existing research on workplace gossip tends to present an overly simplistic view (Tassiello, Lombardi, & Costabile, Reference Tassiello, Lombardi and Costabile2018). Thus, little is known about the mechanisms that drive the effect of leaders on NWG.

This study argues that authentic leadership can reduce employees' NWG. First, leadership is a contextual factor that explains and predicts employees' behavior in the work context. Leaders play a critical role in creating an organizational culture that promotes and supports the awareness and development of employee behavior (Schein, Reference Schein2010). So, there should be theoretical linkages among leadership, work climate, and employees' attitudes and behaviors (Boekhorst, Reference Boekhorst2015; Li, McCauley, & Shaffer, Reference Li, McCauley and Shaffer2017; Liden, Wayne, Liao, & Meuser, Reference Liden, Wayne, Liao and Meuser2014). Second, authentic leadership shows higher self-awareness, internalized morality, balanced processing of information, and relational transparency in the work interaction between leaders and subordinates (Walumbwa, Avolio, Gardner, Wernsing, & Peterson, Reference Walumbwa, Avolio, Gardner, Wernsing and Peterson2008). Similarly, authentic leaders speak with transparency and act in accordance with their beliefs (Avolio, Gardner, Walumbwa, Luthans, & May, Reference Avolio, Gardner, Walumbwa, Luthans and May2004; Lemoine, Hartnell, & Leroy, Reference Lemoine, Hartnell and Leroy2019). Thus, it is more likely to be a trigger that decreases employees' NWG directly and indirectly.

Furthermore, the research proposed that procedural and interactional justices play a significant role in linking authentic leadership and NWG. Authentic leadership highlights leaders' genuine and sincere expression and embraces transparent and adequate information at the workplace. Procedural justice is derived from the degree to which procedures (about pay, rewards, evaluation, etc.) are based on accurate information and widespread voice (Chan & Lai, Reference Chan and Lai2017; Colquitt, Reference Colquitt2001). Interactional justice depends on leaders' sufficient and sincere communication with their subordinates (Colquitt & Rodell, Reference Colquitt, Rodell, Cropanzano and Ambrose2015). Authentic leadership is a great incubator to foster and create procedural justice and interactional justice. Previously, scholars used fairness heuristic theory (Lind, Reference Lind, Greenberg and Cropanzano2001) in the context of justice in the workplace. For example, Colquitt, Conlon, Wesson, Porter, and Ng (Reference Colquitt, Conlon, Wesson, Porter and Ng2001) and Mohammad, Quoquab, Idris, Al Jabari, and Wishah (Reference Mohammad, Quoquab, Idris, Al Jabari and Wishah2019) find that employees' fairness heuristic develops trust about their organizations, positively impacting their work outcomes.

Similarly, Kong and Barsness (Reference Kong and Barsness2018), employing the fairness heuristic model, revealed that overall fairness was positively associated with employees' perceived leader's trustworthiness. Based on fairness heuristic theory (Lind, Reference Lind, Greenberg and Cropanzano2001), it is therefore argued that if an authority (i.e., authentic leader) treats subordinates in a procedurally and interactionally fair manner, such leaders will be perceived as trustworthy and will consequence in positive outcomes (Konovsky, Reference Konovsky2000). Based on these ideas, it is hypothesized that authentic leadership would restrain employees' NWG by creating or performing procedural and interactional justice.

While addressing the above research gaps, this study offers significant contributions. First, as little research has paid attention to understanding how to decrease the occurrence of NWG (Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Chang, Quinton, Lu and Lee2015), this study identifies several antecedents of NWG and provides empirical evidence to testify them. Second, the current paper makes a clear distinction between NWG about supervisors and NWG about coworkers and explored the different intermediary roles of procedural justice and interactional justice between authentic leadership and NWG about supervisors and the relationship of authentic leadership and NWG about coworkers. This study clarifies the relationship between leadership, justice, and NWG, some of the most critical variables in organizations. It helps expand the research on NWG and has important practical implications on how to suppress NWG in organizations.

Theoretical background and hypotheses

Fairness heuristic theory

Fairness heuristic theory (Lind, Reference Lind, Greenberg and Cropanzano2001) helps explain the relationship between workplace authorities (i.e., leaders) and employees. More specifically, it helps to elucidate how employees develop their justice perceptions in their work settings (Cropanzano, Rupp, Mohler, & Schminke, Reference Cropanzano, Rupp, Mohler, Schminke and Ferris2001). The fairness heuristic view is developed based on the group-value model (Lind & Tyler, Reference Lind and Tyler1988) and the relational model (Tyler & Lind, Reference Tyler and Lind1992). The group-value model reveals that individuals interpret treatment quality from ingroup authorities as relational information about their position in their valued group, which shapes their self-concept and influences their behaviors. Similarly, the relational model holds that an employee's judgment of fairness is related to his perceived relationship quality with the leaders. The leader's viewing him as a full member of society, his trust in the leader's ethics and benevolence, and his faith in the leader's neutrality affect his perception of fairness.

The fairness heuristic view posits that when employees experience a situation where justice-related information is not clear or insufficient to make a judgment, they process information heuristically. Furthermore, individuals care about perceived fairness since it helps them make sense of their organizational environment and whether they can trust their leaders or not (Kong & Barsness, Reference Kong and Barsness2018). In this regard, the current study contends that fairness assessments are particularly vital when individuals evaluate their supervisors, someone they are incredibly vulnerable to and frequently interact with (Jones & Martens, Reference Jones and Martens2009; Lind, Reference Lind, Greenberg and Cropanzano2001).

Subsequently, this perception substantially affects individuals' attitudes and behaviors (Huong, Zheng, & Fujimoto, Reference Huong, Zheng and Fujimoto2016; Lind, Reference Lind, Greenberg and Cropanzano2001). Hence, grounding on the fairness heuristic view, the current study argues that both the justice perceptions (i.e., procedural and interactional) will mediate the relationship between authentic leadership and employee's NWG.

Negative workplace gossiping

Workplace gossip is a complex goal-directed behavior (Beersma & Van Kleef, Reference Beersma and Van Kleef2012; Brady, Brown, & Liang, Reference Brady, Brown and Liang2017). It can occur with different functions under environmental ambiguity conditions (Michelson, Van Iterson, & Waddington, Reference Michelson, Van Iterson and Waddington2010). From the perspective of gossipers, they can release pent-up emotions or feelings of anxiety by gossip. Individuals can use gossip to affect others' attitudes, seek attention, and promote their status, self-interest, and self-image by commenting on others (especially belittling others). Also, as a type of informal communication, gossip is beneficial to exchange information with recipients and maintain the relationships between the gossiper and gossip recipients and their interpersonal trust (Martinescu, Janssen, & Nijstad, Reference Martinescu, Janssen and Nijstad2019). Prior studies largely noted two important targets of NWG that includes supervisors (Decoster, Camps, Stouten, Vandevyvere, & Tripp, Reference Decoster, Camps, Stouten, Vandevyvere and Tripp2013; Kim, Moon, & Shin, Reference Kim, Moon and Shin2019) and coworkers (Brady, Brown, & Liang, Reference Brady, Brown and Liang2017). Therefore, the researcher, for the current study, confined NWG to gossip about an individual supervisor and coworkers.

Although gossip has several functions for gossipers, NWG is often connected with the stigmatized talk (Michelson, Van Iterson, & Waddington, Reference Michelson, Van Iterson and Waddington2010) and leads to actual and potentially harmful consequences (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Birtch, Chiang and Zhang2018a, Reference Wu, Kwan, Wu and Ma2018b). It could not only harm gossip subjects' reputation, but also create a hostile work environment for employees. Therefore, in light of the universality and harmfulness of NWG (Grosser et al., Reference Grosser, Lopez-Kidwell, Labianca and Ellwardt2012), understanding or exploring how to weaken the occurrence of NWG has significant implications for gossip theory and practices. The existence of gossip is related to individuals and the organizational context. Grosser et al. (Reference Grosser, Lopez-Kidwell, Labianca and Ellwardt2012) provided several suggestions for improving the organization context, such as creating formal communication processes, fostering a culture of civility, promoting organizational justice, and providing mechanisms for coping with stress. These strategies related to the organizational norms and climate are created or fostered by its leaders. In this study, authentic leadership is viewed as a contextual variable to influence (i.e., weaken) NWG via procedural justice and interactional justice.

Authentic leadership and NWG

Authentic leaders have positive psychological states and internal ethical and moral standards (e.g., moral capacity, efficacy, and courage) to address ethical issues and achieve positive and sustained moral actions (Avolio & Gardner, Reference Avolio and Gardner2005). It involves self-awareness, relationship transparency, balanced processing, and an internalized moral perspective (Walumbwa et al., Reference Walumbwa, Avolio, Gardner, Wernsing and Peterson2008). Self-awareness is the state in which leaders have a correct understanding of their advantages (and disadvantages) and can gain insight into others. Relationship transparency is the state in which leaders always show their true (not false) self, and their behavior expresses their real thoughts and feelings, which can promote trust. Balanced processing refers to the state in which leaders objectively analyze relevant data before making a decision and accept an opinion that challenges their fixed position. Finally, an internalized moral perspective is an intrinsic, integrated form of self-regulation. Self-adjustment is determined by the leader's internal moral standards and values rather than being forced by groups, organizations, and social pressure. Hence, it is an inherent value in line with the leader's expressed decision-making behavior.

Authentic leaders make decisions based on their high moral standards (Walumbwa et al., Reference Walumbwa, Avolio, Gardner, Wernsing and Peterson2008). The subordinates imitate the behaviors of leaders, and their actions are based on positive beliefs. They would rather be helpers or constructive actors than scaremongers, avoiding damaging others for self-interest. In light of their firm moral belief, they view NWG about others as moral turpitude. Moreover, because authentic leaders are self-aware and pursue the objective analysis of relevant data before making a decision, they encourage employees to share information by various means such as voice or whistleblowing, even allowing their subordinates to challenge their status. Under such circumstances, employees have opportunities to express their ideas and feelings through convenient communication channels instead of NWG. Finally, authentic leadership behaviors demonstrate openness, information sharing, and transparency, creating a helping and trusting environment without mutual suspicion among employees (Hirst, Walumbwa, Aryee, Butarbutar, & Chen, Reference Hirst, Walumbwa, Aryee, Butarbutar and Chen2016). In such a climate, employees understand the importance of objectivity and are willing to speak freely through formal communication channels (Hsiung, Reference Hsiung2012). Since justice studies have long recognized that leaders’ fairness has a significant and positive influence on individuals’ feelings, thoughts, and actions, researchers, therefore, believe that under the influence of social learning and organizational climate, employees will consciously reduce their inappropriate behaviors and of course, they will reduce spreading NWG about supervisors and coworkers. Thus, researchers make the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1: Authentic leadership is negatively related to NWG about supervisors and coworkers.

Mediating roles of perceived procedural justice and interactional justice

Justice in organizational settings has been conceptualized in different ways (Chan & Lai, Reference Chan and Lai2017; Colquitt, Reference Colquitt2001). Historically, the scholars had an early emphasis on justice, and their ideas were thought to be related to the fairness of ends achieved, that is, distributive justice (Adams, Reference Adams1966; Leventhal, Reference Leventhal, Gergen, Greenberg and Willis1980). With the development of the understanding of organizational justice, scholars began to study the fair process, which can be used to achieve the fair ends, that is, the procedural justice (Greenberg, Reference Greenberg1990a, Reference Greenberg1990b; Leventhal, Reference Leventhal, Gergen, Greenberg and Willis1980). After that, scholars gradually realized that interactional justice, namely whether people are treated with respect (Bies & Moag, Reference Bies and Moag1986), is given candid communication and full explanation (Ambrose & Schminke, Reference Ambrose and Schminke2003) essential factor in determining fairness. Therefore, organizational justice can be described from the three aspects, distributive justice, procedural justice, and interactional justice (Cohen-Charash & Spector, Reference Cohen-Charash and Spector2002; Moorman, Reference Moorman1991).

In terms of functions, procedural justice and interactional justice are both associated with ensuring fairness in the implementation of decision-making (Tekleab, Takeuchi, & Taylor, Reference Tekleab, Takeuchi and Taylor2005), facilitating collaborative functioning (Dayan & Di Benedetto, Reference Dayan and Di Benedetto2008), and the formation of social exchange relationships at work (Aryee, Budhwar, & Chen, Reference Aryee, Budhwar and Chen2002; Masterson, Lewis, Goldman, & Taylor, Reference Masterson, Lewis, Goldman and Taylor2000). Many studies have demonstrated evidence for the positive influence of procedural justice and interactional justice on employees' job attitude and behaviors such as job satisfaction, job involvement (Clay-Warner, Reynolds, & Roman, Reference Clay-Warner, Reynolds and Roman2005; Khan, Abbas, Gul, & Raja, Reference Khan, Abbas, Gul and Raja2015), and employees' cooperation and helping behaviors (Schminke, Arnaud, & Taylor, Reference Schminke, Arnaud and Taylor2015). Similarly, injustice leads to emotional reactions such as distrust, anger, and frustration, in turn, leading to unethical behavior (Jacobs, Belschak, & Den Hartog, Reference Jacobs, Belschak and Den Hartog2014). In this study, it is expected that those two types of justice are related to employees' NWG about supervisors and coworkers.

Moreover, the study assumes that the relationship between authentic leadership and NWG will be elucidated, in part or in full, by employee's fairness perceptions. For instance, in the presence of authentic leadership in the work setting, employees may perceive the work climate as treating them fairly. Johnson and Chang (Reference Johnson and Chang2008) posit that employees are more likely to identify strongly with leaders who offer fair treatment. More clearly, this fairness perception significantly affects employees' attitudes and behaviors (Lind, Reference Lind, Greenberg and Cropanzano2001). Prior studies based on fairness theory show that employees responded with anger and resentment when leaders did not treat them fairly (Folger & Martin, Reference Folger and Martin1986) and decide whether to cooperate or not with others in the work context (Colquitt, Zipay, Lynch, & Outlaw, Reference Colquitt, Zipay, Lynch and Outlaw2018). Hence, it is suggested that favorable fairness perception regarding one's leaders, in turn, will negatively impact the employees' NWG about their supervisors and coworkers alike.

Procedural justice implies the impartiality of the process (policies, procedures, and criteria) by which results are determined. When employees perceive procedures as fair, they have a positive attitude toward the overall organization, repaying the organization (Cropanzano, Prehar, & Chen, Reference Cropanzano, Prehar and Chen2002). On the contrary, the unfairness of a process will make employees psychologically unbalanced and even angry, resulting in the occurrence of revenge motivation (Cropanzano, Bowen, & Gilliland, Reference Cropanzano, Bowen and Gilliland2007). Compared with other revenge acts (e.g., sabotage or destroying organizational property), spreading negative rumors about the organization is not visible and low risk. Therefore, this motivation may be acted on by spreading negative rumors about the organization (Bordia, Kiazad, Restubog, DiFonzo, Stenson, & Tang, Reference Bordia, Kiazad, Restubog, DiFonzo, Stenson and Tang2014).

Besides, to formulate a fair procedure, accurate and adequate information is essential (Chan & Lai, Reference Chan and Lai2017). Because a critical aspect of procedural justice allows participants to have input or a voice in the outcome (DeConinck, Reference DeConinck2010), procedural justice means openness of communication. When employees have job dissatisfaction or question the evaluation of their performance, they give feedback through a formal communication channel, not by gossip.

Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 2: Employees' perceptions of procedural justice are negatively related to NWG about supervisors and coworkers.

Interactional justice reflects the degree to which leaders give their respect and information when executing a program or a decision. Interactional justice is operationalized as one-to-one interaction between supervisors and their subordinates (Cropanzano, Prehar, & Chen, Reference Cropanzano, Prehar and Chen2002). Employees feel valued and respected by direct supervisors and have a high degree of trust in their relationships (Ellwardt, Wittek, & Wielers, Reference Ellwardt, Wittek and Wielers2012). In this relationship, employees and their supervisors are prone to help each other (Cropanzano, Prehar, & Chen, Reference Cropanzano, Prehar and Chen2002). Since NWG is harmful to gossip targets, those employees who have received interactional justice from their leaders, in turn, could try and reduce NWG about their supervisors. Also, the high degree of trust in the relationship helps employees relieve stress, and they will not spread NWG toward their coworkers.

Furthermore, the benign interaction between leaders and subordinates will evoke a sense of harmony and respect in the workplace. In harmonious and respectful relationships, employees should have more spontaneous and informal face-to-face communication (Dayan & Di Benedetto, Reference Dayan and Di Benedetto2008) to promote adequate information sharing rather than passing on the NWG.

In a recent investigation of nurses in South Korea, empirical evidence indicated that nurses perceived interpersonal justice and informational justice initiated by their immediate supervisor (e.g., the head nurse in the workplace) to be negatively related to NWG about their supervisor (Kim, Moon, & Shin, Reference Kim, Moon and Shin2019).

As discussed above, the following hypothesis is put forward:

Hypothesis 3: Employees' perceptions of interactional justice are negatively related to NWG about supervisors and coworkers.

Leaders behave as ‘climate engineers’ to shape employee perceptions of organizations by implementing organizational policies and model desired behavior (Hsiung, Reference Hsiung2012). Many studies have argued that leaders should have crucial influences on employees' perceptions of organizational justice (Kirkman, Chen, Farh, Chen, & Lowe, Reference Kirkman, Chen, Farh, Chen and Lowe2009; Xu, Loi, & Ngo, Reference Xu, Loi and Ngo2016). Authentic leaders show a high standard of morality and integrity, forming a highly ethical organizational atmosphere (Jensen & Luthans, Reference Jensen and Luthans2006; Wong & Cummings, Reference Wong and Cummings2009), so it can promote the subordinates' perception that the organization functions with fairness.

To be specific, authentic leaders listen to different opinions and revise their ideas before making decisions. In this process, subordinates can freely express their views and participate in the decision-making process, which helps construct an intelligent decision system and a set of fair operating rules (Hsiung, Reference Hsiung2012), promoting their perception of procedural justice (Masterson et al., Reference Masterson, Lewis, Goldman and Taylor2000).

Also, authentic leaders follow high ethical standards and treat employees with sincerity, strengthening the interpersonal justice perceived by employees. Authentic leaders disclose information and present an authentic self to subordinates. Those behaviors share real and adequate communication with the subordinates, which will enhance the informational justice perceived by employees. Therefore, authentic leadership will enhance the interactional justice perceived by the employees.

Thus, the following hypothesis is suggested:

Hypothesis 4: Authentic leadership is positively related to employees' perception of organizational justice, such as (4a) procedural justice and (4b) interactional justice.

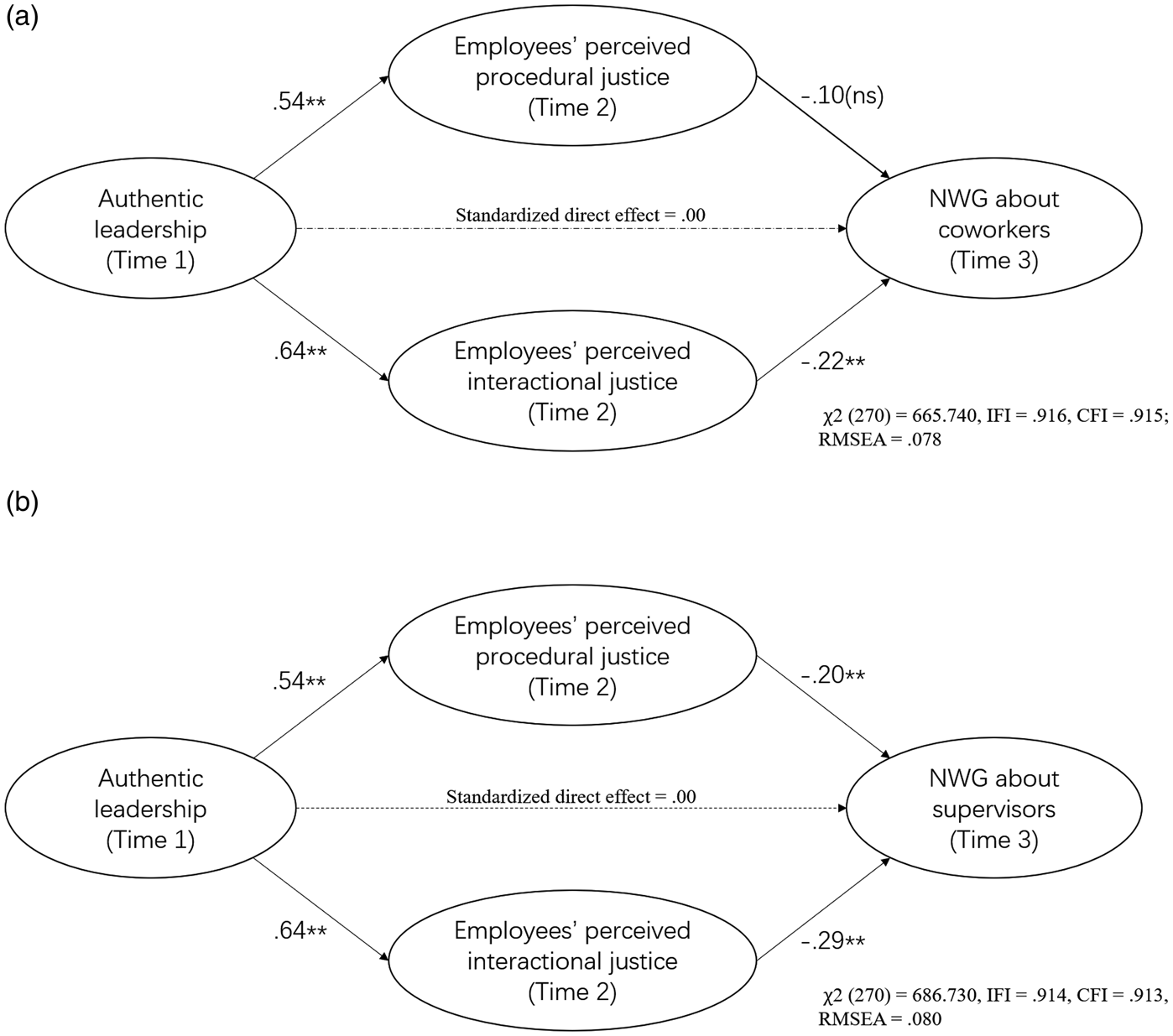

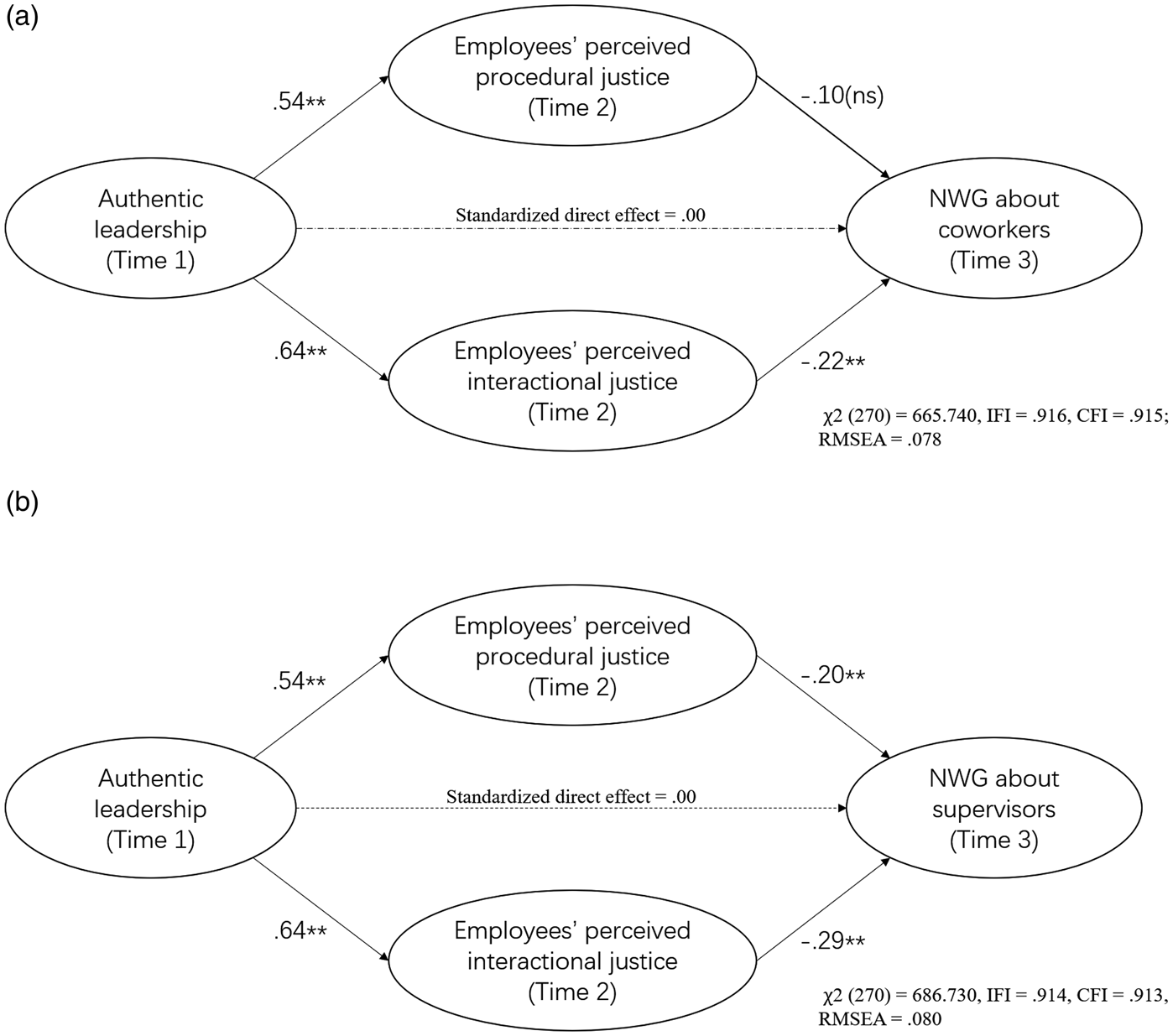

Given the above relationships, the question arises as to whether employees' perceptions of procedural justice and interactional justice mediate the relationship between authentic leadership and NWG. Employees who are highly influenced by authentic leaders may reduce the spreading of NWG. In addition, authentic leaders foster or create procedural and interactional justice, which constructs a fair, satisfying, open, and transparent workplace with low NWG results. To summarize, it is suggested that by leading and performing authentically, leaders contribute to employees' justice perception (procedural and interactional), which may reduce NWG about supervisors and coworkers in the workplaces.

Moreover, the mediating role of justice perceptions (i.e., procedural and interactional) can be explained through the lens of fairness heuristic theory (Lind, Reference Lind, Greenberg and Cropanzano2001; Van den Bos, Lind, & Wilke, Reference Van den Bos, Lind, Wilke and Cropanzano2001). According to this view, as individuals navigate through their work environment, they develop fairness perceptions (procedural and interactional perceptions) as they encounter justice-related information. Consequently, individuals use fairness perceptions to decide whether to trust the organizational authorities (i.e., leadership) and then reciprocate accordingly. Based on the prior discussion and grounded in the fairness heuristic view, this study argues that the perception of both procedural and interactional justice can mediate the association between authentic leadership and employees' NWG. Based on this assumption, the following hypotheses are proposed (Figure 1):

Hypothesis 5: Employees' perception of procedural justice mediates an association between authentic leadership and NWG about supervisors and coworkers.

Hypothesis 6: Employees' perception of interactional justice mediates an association between authentic leadership and NWG about supervisors and coworkers.

Figure 1. Research model.

Method

Sample and procedure

The participants were employees working in a large information technology (IT) corporation in China. This study adopted three phases of data collection to reduce the common method variance (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003) and explore the causal relationship among authentic leadership, employees' perception of justice, and negative gossip. In order to reduce the social desirability response bias (especially for evaluating NWG about supervisors and coworkers), the process of collecting data emphasized confidentiality and anonymity. Each employee was reminded to use the same code or alias in all three questionnaires. Following Cheng, Bai, and Yang (Reference Cheng, Bai and Yang2019), the researchers made all participants aware that they were doing an anonymous survey, placed each of the questionnaires in a blank envelope to make all anonymous without assigning any identifiable code, and reminded each employee to use the same code or alias in all three questionnaires. In addition, to enhance the target respondents' enthusiasm and earnest efforts, one fine gift was put into the envelope with the questionnaire in each wave survey. The human resource staff accompanied us to distribute and collect the questionnaires.

In the three-wave surveys (two 4-week intervals) of data distribution and collection, the surveyed company's top management and human resource managers provided us with strong support. Under the premise of meeting the research needs, researchers considered that the matching data could be recovered (the employee is at work when the questionnaire is sent and received three times) and that the cost could be saved as far as possible. As a result, 600 questionnaires were an appropriate volume in each wave survey.

At time 1, questionnaires were distributed to 600 employees who were selected by human resource managers. Participants were invited to rate the level of authentic leadership of their supervisors. In total, 527 employee participants completed the questionnaires, yielding an 89% response rate. At time 2, questionnaires relating to procedural and interactional justice were sent to 600 employees who were expected to be those employees to whom the questionnaire was sent for the time 1 data (although, are not sure who these 600 were). In total, 520 employees completed the questionnaires, yielding an 85.3% response rate. At time 3, similarly to earlier data collection, 600 employees were invited to rate the level of NWG about supervisors and coworkers. In total, 530 employees completed the questionnaires, with a response rate of 88.3%.

By checking the code or alias and the demographic information in each questionnaire, this research identified 240 validly matched questionnaires completed for all three phases. Table 1 provides a comprehensive view of these respondents' demographic information.

Table 1. Demographic profile of respondents (N = 240)

Measures

All items in this study were measured on Likert-type scales from 1 to 5. The survey adopted in this study used the Chinese language throughout. However, all the scales were initially constructed and developed in English (except for NWG about supervisors and coworkers, which were originally constructed in English and Chinese). The translation and back-translation procedure (Brislin, Reference Brislin1970) was used, and pretested key measures with a pilot sample of 94 employees. Appendix A shows a list of items.

Authentic leadership

Authentic leadership was measured at the individual level using a 14-item scale developed by Neider and Schriesheim (Reference Neider and Schriesheim2011). This global measure included four dimensions: self-awareness (three items: e.g., ‘My leader is clearly aware of the impact he/she has on others’), relational transparency (three items: e.g., ‘My leader openly shares information with others’), internalized moral perspective (four items: e.g., ‘My leader uses his/her core beliefs to make decisions’), and balance processing (four items: e.g., ‘My leader encourages others to voice opposing points of view’). Subordinates rated their supervisor's authentic leadership on a 5-point Likert scale anchored by 1 (strongly disagree) and 5 (strongly agree). The degrees of reliability for the ‘self-awareness,’ ‘relational transparency,’ ‘internalized moral perspective,’ and ‘balance processing’ were .79, .84, .79, and .86, respectively, while the Cronbach's alpha for the aggregated scale was .92.

Although the measure of authentic leadership viewed as the high-order construct best represented theoretical derivation of in current study (Braun & Nieberle, Reference Braun and Nieberle2017), the researchers also assess the suitability of treating the four dimensions separately or together as part of an overall authentic leadership factor. Following Braun and Nieberle (Reference Braun and Nieberle2017), the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for nested data compares three models: A single-factor model, an oblique first-order model, and a second-order model. Compared to the single-factor model (χ2 (77) = 257.568, IFI = .898, CFI = .897, RMSEA = .099), the results demonstrated better fit for the first-order model (χ2 (71) = 123.396, IFI = .970, CFI = .970, RMSEA = .056) and second-order model (χ2 (73) = 125.095, IFI = .971, CFI = .970, RMSEA = .055). The results did not show significant differences between the first-order and the second-order model. Therefore, the four dimensions did not analyze four dimensions separately.

Procedural justice

Procedural justice was measured using a seven-item scale developed by Colquitt (Reference Colquitt2001). Items asked to what extent employees could express their views and feelings during procedures, and to what extent the procedures were free of bias, were based on accurate information, and upheld ethical and moral standards. Items were scored on a five-point scale anchored by 1 (strongly disagree) and 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach's alpha for this scale was .92.

Interactional justice

Interactional justice was measured using a nine-item scale developed by Colquitt (Reference Colquitt2001). As principal component analysis revealed only one factor with an eigenvalue greater than 1.0, adopted the aggregated scale by averaging nine items' values. Employees were asked to assess the extent to which supervisors provided explanations of and justified their decisions and treated employees with dignity and respect. Items were scored on a five-point scale anchored by 1 (strongly disagree) and 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach's alpha for this scale was .95.

Negative workplace gossip

According to Brady, Brown, and Liang (Reference Brady, Brown and Liang2017), NWG includes two dimensions: NWG about coworkers and NWG about supervisors. NWG about coworkers was measured using a five-item scale developed by Brady, Brown, and Liang (Reference Brady, Brown and Liang2017). An example item was: ‘In the last month, how often have you questioned a coworker's abilities while talking to another work colleague?’ Items were scored on a five-point scale anchored by 1 (never) and 5 (always). The Cronbach's alpha for this scale was .88. NWG about supervisors was measured using a five-item scale developed by Brady, Brown, and Liang (Reference Brady, Brown and Liang2017). An example item was: ‘In the last month, how often have you asked a work colleague if they have a negative impression of something that your supervisor has done?’ Items were scored on a five-point scale anchored by 1 (never) and 5 (always). The Cronbach's alpha for this scale was .86.

Control variables

Following previous gossip and justice research, The following variables were controlled to separate out their influences on justice and NWG: age, gender, company tenure, educational level, position, and department size (Cropanzano, Prehar, & Chen, Reference Cropanzano, Prehar and Chen2002; Kim, Moon, & Shin, Reference Kim, Moon and Shin2019; Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Chang, Quinton, Lu and Lee2015).

Analytic strategy

Although those concepts (leadership, procedural justice, and NWG) seem to be multileveled by nature, researchers are interested in individuals' perceptions of authentic leadership, procedural justice, interactional justice in the current study. Therefore, the current study theorized and analyzed those variables as individual-level variables associated with their measures.

To test mediating effects (Hypotheses 5 and 6) of procedural justice and interactional justice on the relationship between authentic leadership and NWG about coworkers and supervisors, the study followed Zhao, Lynch, and Chen (Reference Zhao, Lynch and Chen2010) suggestion that only the statistically significant indirect effect should be taken as evidence for mediation and researchers should bootstrap the sampling distribution of the indirect effect. In view of the fact that the research model includes two mediators (multiple mediators), and need to estimate two specific indirect effects (from authentic leadership to NWG via (1) procedural justice and (2) interactional justice), instead of total indirect effects. Therefore, the PROCESS macro was used to conduct mediation analysis (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013; Memon, Cheah, Ramayah, Ting, & Chuah, Reference Memon, Cheah, Ramayah, Ting and Chuah2018). Before analyzing mediating effects, Hypotheses 1–4 was tested using multiple stepwise regression analysis with controls. This kind of method is beneficial for researchers to contrast other similar research topics where prior studies concern the relationships among some relevant variables – for example, transformational leadership and procedural justice (Kirkman et al., Reference Kirkman, Chen, Farh, Chen and Lowe2009), justice perceptions, and gossip (Kim, Moon, & Shin, Reference Kim, Moon and Shin2019) – using regression analysis (Gefen, Straub, & Boudreau, Reference Gefen, Straub and Boudreau2000). Finally, the entire observed covariance matrix's overall fit with the hypothesized model was also examined, using covariance-based structural equation model (SEM) techniques (AMOS).

Results

Construct validity and assessment of common method

The CFA was conducted using AMOS version 24 to test the construct validity. The measurement model consisted of five latent variables: authentic leadership (four indicators representing four dimensions), procedural justice (seven indicators), interactional justice (nine indicators), NWG about coworkers (five indicators), and NWG about supervisors (five indicators). The hypothesized five-factor model yielded a much better fit to the data χ2(394) = 848.032, IFI = .920, CFI = .919; RMSEA = .069. Moreover, all items loaded significantly on the respective latent factors, with standardized factor loadings ranging from .68 to .90, above the recommended level of .40. All values of composite reliability (CR) index exceeded .80, and all values of average variance extracted (AVE) index are higher than .50. Other alternative models were also examined to test the discriminate validity of those five variables. The one-factor model was obtained by loading all items into a latent factor, and the two-factor model, the three-factor model, and two four-factor models were obtained by combining variables with high intercorrelations. In Table 2, the results of the CFAs indicated that the five-factor model fitted the data better than any of the other alternative models. Thus, the discriminant and convergent validity of the five constructs were confirmed.

Table 2. Results of CFA

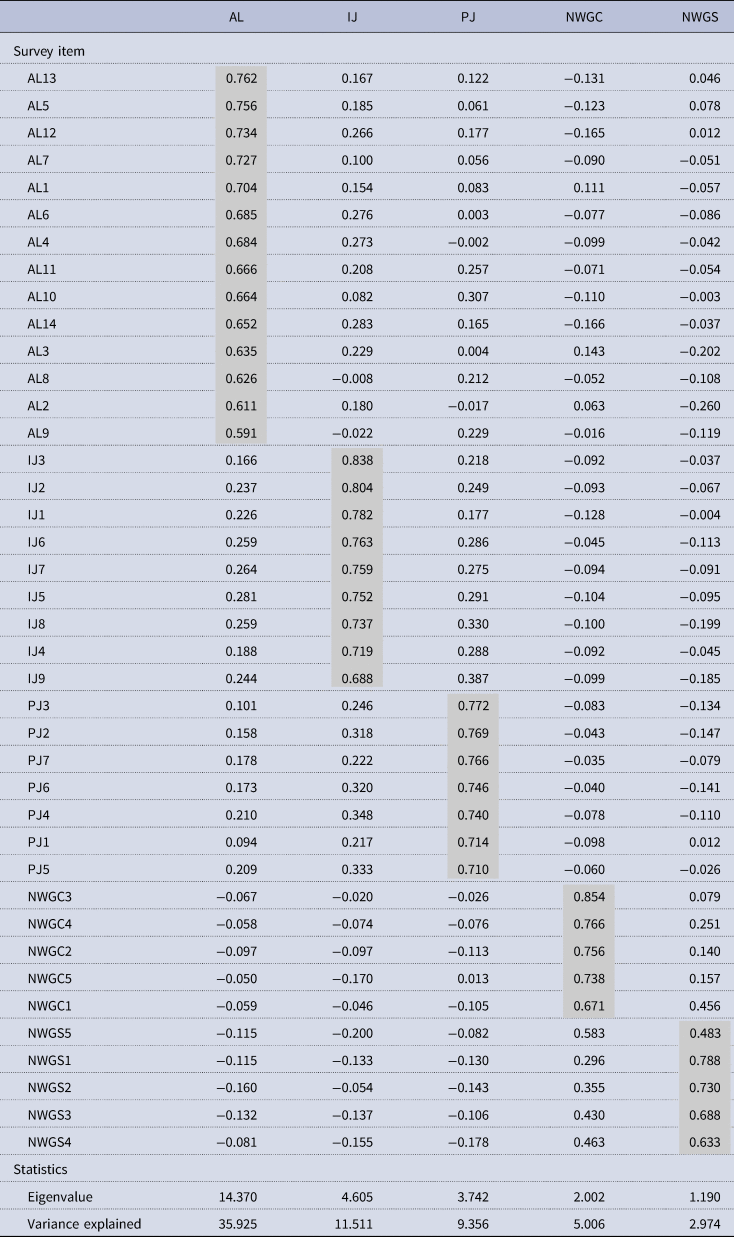

Because all the variables in this study were measured from the employee's perspective, it possibly raised the possibility for common method bias. This study conducted two remedies to test the bias: Harman's single-factor test and controlling for the effects of a single unmeasured latent method factor (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). First, the measures of five variables (authentic leadership, procedural justice, interactional justice, NWG about coworkers, and NWG about supervisors) were subjected to exploratory factor analysis (principal components) with oblique rotation (see Appendix B). The five factors collectively account for 64.8% of the total variance. The first factor explained 35.9% of the variance, which is less than the 50% benchmark used in Harman's single-factor test, suggesting that common method variance was not present in the data (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). Second, a single common method factor approach was used. The CFA was conducted. All items of the five scales were loaded on their respective factors (the five factors), and all those items were loaded on one created common method factor. The fit indices of this model (χ2(393) = 844.180, IFI = .920, CFI = .919; RMSEA = .069) were similar to those found in the hypothesized measurement model (χ2(394) = 848.032, IFI = .920, CFI = .919; RMSEA = .069). The results showed that the addition of a common method factor did not improve model fit. In general, common method bias did not represent a grave threat to the validity of research findings.

Descriptive statistics

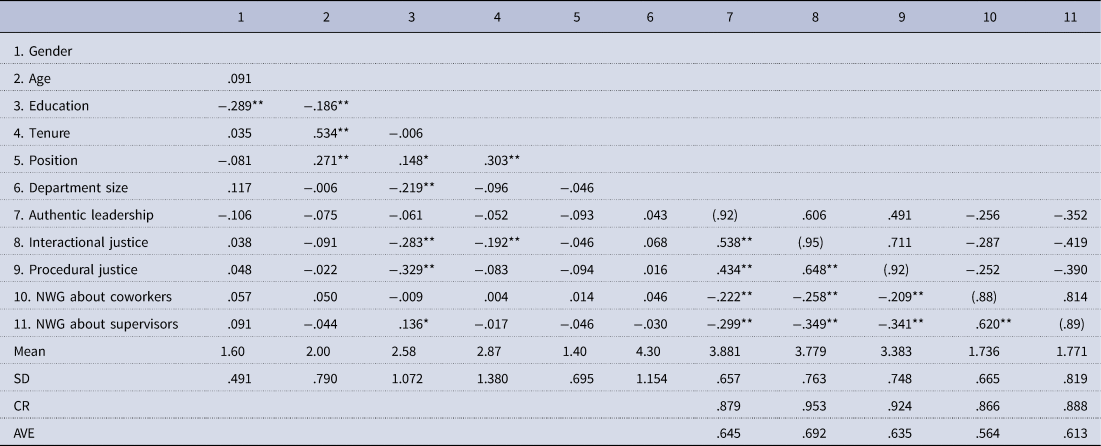

Table 3 reports the means, standard deviations, CR, AVE, and correlations of the variables. All results were in the expected direction. Specifically, procedural justice and interactional justice were significantly related to authentic leadership (independent variable) and NWG about supervisors and coworkers (dependent variables). This indicated that it was appropriate to proceed with formal mediation analysis, consistent with the study's theoretical expectations.

Table 3. Means, standard deviations, and correlations among the study variables

Gender: 1 = ‘male’, 2 = ‘female’; Education: 1 = ‘middle school’, 2 = ‘high school’, 3 = ‘college’, 4 = ‘Bachelor degree’, 5 = ‘Master or over’; Position: 1 = ‘general staff’, 2 = ‘first-line manager’, 3 = ‘middle manager’, 4 = ‘top manager’.

Internal reliabilities for the construct are shown in parentheses on the diagonal. The correlations of variables in measurement model are shown above the diagonal.

Note. N = 240.

**p < .01, *p < .05.

Hypothesis testing

Multiple linear regression analysis was used to test all main effect hypotheses (see Table 4). Hypothesis 1 proposed that authentic leadership is negatively related to NWG. As shown in Table 4, in models 6 and 9 there were significant relationships between authentic leadership and NWG about supervisors (β = −.29, p < .001) and coworkers (β = −.22, p < .01). Hence, Hypotheses 1 was fully supported.

Table 4. Regression results

Note. N = 240.

***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05, †p < .06.

Hypothesis 2 predicted the negative effect of employees' perception of procedural justice on NWG. The results in Table 4 show that employees' perception of procedural justice is significantly related to NWG about supervisors (β = −.17, p < .05) (see model 7), but is not significantly related to NWG about coworkers (β = −.07, n.s.) (see model 10). Hence, Hypothesis 2 was partly supported.

Hypothesis 3 predicted the negative effect of employees' perception of interactional justice on NWG. The results in Table 4 show that the hypothesis was supported. The results in Table 4 show that employees' perception of interactional justice is significantly related to NWG about coworkers (β = −.20, p < .05) (see model 10), and the relationship between employees' perception of interactional justice and NWG about supervisors is marginally significant (β = −.17, p < .06) (see model 7). No collinearity problems were found.

Hypotheses 4a and 4b proposed that authentic leadership is positively related to employees' perceptions of procedural justice and interactional justice. As shown in Table 4, the two hypotheses were supported. Authentic leadership was a strong predictor for employees' perceptions of procedural justice (β = .42, p < .001) (see model 2) and interactional justice (β = .52, p < .001) (see model 4).

Hypotheses 5 and 6 proposed that the justice dimensions mediate the association between authentic leadership and NWG. The three-step approach proposed by Baron and Kenny (Reference Baron and Kenny1986) was conducted to test the mediation. Although both of the mediators (employees' perceptions of procedural justice and interactional justice) and the independent variable (authentic leadership) are included in the models, the coefficient for authentic leadership is not significant (see models 7 and 10 in Table 4). The results show employees' perceptions of procedural justice and interactional justice are two underlying mechanisms that mediate the relationship between authentic leadership and NWG about supervisors. However, employees' perception of interactional justice is the mediator mediating the relationship between authentic leadership and NWG about coworkers, but the perception of procedural justice doesn't work as a mediator between the authentic leadership and NWG about coworkers (β = −.07, n.s, in model 10). In addition to the above analysis, the SPSS macro, PROCESS (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013), provided important information when examined the indirect effect of authentic leadership on NWG about coworkers and NWG about supervisors. The results in Table 5 show that the indirect effects of authentic leadership through employees' perception of interactional justice were significant for NWG about coworkers (b = −.1150, SE = .0420, 95% confidence interval (CI) [−.2039, −.0372]) and for NWG about supervisors (b = −.1285, SE = .0475, 95% CI [−.2330, −.0461]); the indirect effect of authentic leadership through employees' perception of procedural justice for NWG about supervisors is significant (b = −.0712, SE = .0345, 95% CI [−.1512, −.0135]) and for NWG about coworkers is not significant. Hence, Hypothesis 5 was partly supported, and Hypothesis 6 was fully supported.

Table 5. Indirect effect of authentic leadership on dependent variable

To enhance the robustness of the hypotheses test, this research used covariance-based SEM techniques (AMOS) to examine the overall fit of entire observed covariance matrix with the study hypothesized model. The SEM proposed showed goodness-of-fit indices, and it may be considered satisfactory (Figure 2). The results of relationships between variables in SEM are in accordance with those in the prior regression analysis; only the negative relationship between procedural justice and NWG about supervisors was more significant (β = −.20, p < .01).

Figure 2. Diagram of paths of SEM.

Discussion

To fill the gap of knowledge about how authentic leadership decreases NWG, this study investigates the function of authentic leadership's influence on employees' NWG through the role of employees' perception of justice. Based on fairness heuristic theory (Lind, Reference Lind, Greenberg and Cropanzano2001), the current results indicate that employees' perceptions of procedural and interactional justice act as two mediators in the relationships between authentic leadership and NWG. Specifically, the study hypothesis ‘Authentic leadership is negatively related to NWG about supervisors and coworkers’ was supported, which reveals that in the presence of authentic leadership, employees NWG are more likely to reduce about their supervisors and coworkers. Next, the study hypothesis ‘Employees’ perceptions of procedural justice are negatively related to NWG about supervisors and coworkers’ was found partially support, whereas ‘Employees’ perceptions of interactional justice are negatively related to NWG about supervisors and coworkers’ was fully supported.

Furthermore, the study hypothesis ‘Authentic leadership is positively related to employees’ perception of organizational justice, such as (4a) procedural justice and (4b) interactional justice’ was also supported. Finally, with regard to the mediation hypothesis, ‘Employees’ perception of procedural justice mediates an association between authentic leadership and NWG about supervisors and coworkers,’ the study results support the indirect link between authentic leaders with NWG about supervisors but not with coworkers. However, concerning the hypothesis ‘Employees’ perception of interactional justice mediates an association between authentic leadership and NWG about supervisors and coworkers,’ interactional justice perception was found to mediate the relationship between authentic leadership-NWG (about supervisors and coworkers). The findings provide several important theoretical and practical implications.

Theoretical implications

This study sheds new light on the investigation of authentic leadership and employees' negative behavior (NWG). As authentic leadership, being a ‘highly developed organizational context,’ can influence or formulate employees' self-awareness and self-regulated behaviors (Avolio & Gardner, Reference Avolio and Gardner2005) and foster employees' positive self-development. For example, most previous studies linked authentic leadership to employees' positive or proactive behaviors such as voice, internal whistleblowing (Liu, Liao, & Wei, Reference Liu, Liao and Wei2015), creativity (Lyubovnikova, Legood, Turner, & Mamakouka, Reference Lyubovnikova, Legood, Turner and Mamakouka2017), and organizational citizenship behavior (Avolio et al., Reference Avolio, Gardner, Walumbwa, Luthans and May2004). However, less attention has been paid to the value of authentic leadership in restricting employees' negative behavior. Responding to this gap, the current study explored whether authentic leaders restrict employees' negative behavior (mitigating negative gossip).

In line with prior empirical findings (i.e., Kampa, Rigotti, & Otto, Reference Kampa, Rigotti and Otto2017; Laschinger, Wong, & Grau, Reference Laschinger, Wong and Grau2013), the results showed a negative relationship between authentic leadership and NWG. Therefore, this study findings further demonstrate authentic leadership's efficacy, which is a genuine, just, moral, and information sharing leadership. It enriches the existing literature by providing a greater understanding of authentic leadership's value in reducing employees' unethical or negative behaviors.

This study deepens the research on the process of how authentic leadership can reduce the employee's negative behaviors. This study identified antecedents of NWG and explored the mechanisms that authentic leadership influences the NWG based on fairness heuristic and justice theoretical lens. As procedural and interactional justice mediated the relationship between authentic leadership and NWG about supervisors and interactional justice also functions as a mediator between authentic leadership and NWG about coworkers, this means employees' perceptions of justice could be an effective mechanism to understand the process that authentic leadership influences the NWG.

Moreover, this research clarifies the different types of gossip: NWG about supervisors and NWG about coworkers and tests the mediation effects of interactional justice and procedural justice to the relationship between authentic leadership and NWG about supervisors and NWG about coworkers. This research shows the differences of the mediating effects of procedural and interactional justice between authentic leadership and NWG about supervisors and NWG about coworkers. Specifically, the current findings underscore the significance of interactional justice at work. Interactional justice not only mediates the relationship between authentic leadership and NWG about supervisors, but also the relationship between authentic leadership and NWG about coworkers. Authentic leadership cares about the employees, respects them, communicates with them, and makes them perceive interactional justice. According to the agent-dominance model (Jones, Fassina, & Uggerslev, Reference Jones, Fassina and Uggerslev2006), employees' perception of interactional fairness causes variance in both group-focused and supervisory-focused outcomes. Using the agent-dominance model, Al-Atwi (Reference Al-Atwi2018) also shows that leaders' interactional justice affects the employees' relational identification and work-group identification through personalized and depersonalized mechanisms. The employees' relational identification will reduce the employees' NWG about supervisors, and their work-group identification will alleviate the employees' NWG about coworkers.

However, procedural justice just mediates the relationship between authentic leadership and NWG about supervisors, while it doesn't mediate the relationship between authentic leadership and NWG about coworkers. According to the social exchange and the norm of reciprocity view, when authentic leadership listens to the employee and keeps the information transparent to the employees, the leaders create the environment of procedural justice, which will strengthen the employees' identification with the organization and make the employees want to give back to the organization. As leaders are the representatives of the organization, the employees will decrease the NWG about supervisors. However, the results indicate that authentic leaders do not impact NWG about coworkers via procedural justice. One of the reasons for this result might be that procedural justice represents the organization rather than employees' groups; therefore, procedural justice may not link directly to group-focused outcomes (e.g., NWG about coworkers), and it cannot mediate between authentic leadership and NWG about coworkers. Rupp and Cropanzano (Reference Rupp and Cropanzano2002) reported that procedural justice was unable to predict the organizational citizenship behavior through social exchange theory, which also supports this research's conclusion (Rupp & Cropanzano, Reference Rupp and Cropanzano2002). The findings reveal the different mechanisms of authentic leadership on NWG about supervisors and NWG about coworkers, deepening theoretical research on NWG. Future research should explore other theories to understand the relationship between procedural justice and NWG about coworkers, such as mediators or moderators.

By studying the relationship of different dimensions of justice and employees' negative gossip, this study has demonstrated that employees' perceptions of procedural and interactional justice are differently related to the outcome variables (NWG about supervisors and coworkers). This enriches the justice literature and responds to the call from prior researchers who suggested a relationship between (in)justice and gossip (Grosser et al., Reference Grosser, Lopez-Kidwell, Labianca and Ellwardt2012; Kim, Moon, & Shin, Reference Kim, Moon and Shin2019; Şantaş et al., Reference Şantaş, Uğurluoğlu, Özer and Demir2018).

Practical implications

Although workplace gossip, as a fundamental human activity, will never be wholly eliminated (Grosser et al., Reference Grosser, Lopez-Kidwell, Labianca and Ellwardt2012), minimizing NWG about supervisors and coworkers is possible. This study provides some implications for managerial practice.

This study identified several factors that constrained NWG. The first concerns authentic leadership. As an authentic leader plays a critical role in influencing employees' NWG, an organization may opt to invest in training programs for existing leaders to improve their authentic values and behavior or identify, select, and promote people who demonstrate honesty and integrity as leaders. Meanwhile, current leaders should pay attention to their cultivation of the qualities of authentic leadership.

Existing leaders must strengthen their understanding of ethical norms and regulate their behaviors within ethical requirements. At the same time, current leaders can self-reflect, recognize their strengths and weaknesses, and continuously improve themselves. When making decisions, current leaders have to collect multiple pieces of information and increase their transparency. When communicating with colleagues, leaders must also be sincere, not falsify, and not engage in intrigue.

This research shows that NWG may occur in an atmosphere where employees have a low sense of procedural justice and interactional justice. Therefore, organizations and leaders should pay attention to employees' sense of fairness to organizational policies, procedures, and rules, as well as any sense of injustice in supervisors' behaviors. The organization should create an open communication channel that permits employees to express their authentic voices and feelings before making decisions. More importantly, leaders must walk the talk and improve their communication skills, keeping up effective communication with their subordinates, which shapes employees' perceptions of justice.

Limitations and directions for future research

This study has a few limitations which could be overcome through more research. First, data analyses were based on a sample from an IT corporation in China, limiting the external validity of the current findings. Future research should use a diverse representative sample. Second, although the study measured the independent variable (authentic leadership), mediating variables (employees' perceptions of procedural justice and interactional justice) and outcome variables (NWG about supervisors and coworkers) with a 1-month time lag, common method bias issues might remain.

The research found that employees' perceptions of procedural and interactional justice played a part mediating role in the relationship between authentic leadership and NWG. Although the study used the psychological term of employees' perception, the nature of the two types of justice is related to information sharing and adequate communication (Chan & Lai, Reference Chan and Lai2017). Future research should directly explore the functions of those activities within the field of gossip. Moreover, considering the opposite of justice, other variables, such as employees' perception of organizational politics (Cheng, Bai, & Yang, Reference Cheng, Bai and Yang2019), may be a predictor of NWG.

The research shows that authentic leadership can effectively reduce NWG. Future research to deepen and widen authentic leadership's current understanding could find other negative employees' behaviors as potential outcome variables.

The determinants of other forms of negative gossip, such as NWG about the organization, and several concrete types of workplace gossip could be explored in future research. Specially speaking, according to Brady, Brown, and Liang (Reference Brady, Brown and Liang2017), for different gossip subjects, the reasoning for gossip occurrence may vary. Furthermore, as less existing research has paid attention to positive gossip, which is very different from negative gossip, there remains many research opportunities for future investigation.

Conclusion

As gossiping is an inevitable phenomenon, which significantly influences several workplace outcomes, it is essential to know what factors stimulate NWG and how it can be appropriately managed. Our research extends fairness heuristic view and justice research to employees' workplace gossip and shows that authentic leadership is inversely related to negative gossiping at work. Furthermore, the findings proposed that both procedural justice and interactional justice perception work as an underlying mechanism between authentic leadership and NWG about their supervisors and coworkers. Since there are deleterious outcomes of NGW in the workplace, more studies are needed to explore the factors and mechanisms inhibiting NGW, thereby helping organizations counter negative gossiping in the workplace effectively.

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by ‘the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities’ (grant number: 20720181092).

Appendix A: Measurements

Authentic Leadership from Neider and Schriesheim (Reference Neider and Schriesheim2011)

Factor 1: Self-awareness

AL1. My leader describes accurately the way that others view his/her abilities.

AL2. My leader shows that he/she understands his/her strengths and weaknesses.

AL3. My leader is clearly aware of the impact he/she has on others.

Factor 2: Relational transparency

AL4. My leader clearly states what he/she means.

AL5. My leader openly shares information with others.

AL6. My leader expresses his/her ideas and thoughts clearly to others.

Factor 3: Internalized moral perspective

AL7. My leader shows consistency between his/her beliefs and actions.

AL8. My leader uses his/her core beliefs to make decisions.

AL9. My leader resists pressures on him/her to do things contrary to his/her beliefs.

AL10. My leader is guided in his/her actions by internal moral standards.

Factor 4: Balanced processing

AL11. My leader asks for ideas that challenge his/her core beliefs.

AL12. My leader carefully listens to alternative perspectives before reaching a conclusion.

AL13. My leader objectively analyzes relevant data before making a decision.

AL14. My leader encourages others to voice opposing points of view.

Procedural Justice from Colquitt (Reference Colquitt2001)

The following items refer to the procedures used to arrive at your outcome. To what extent:

PJ1.Have you been able to express your views and feelings during those procedures?

PJ2.Have you had influence over the (outcome) arrived at by those procedures?

PJ3.Have those procedures been applied consistently?

PJ4.Have those procedures been free of bias?

PJ5.Have those procedures been based on accurate information.

PJ6.Have you been able to appeal the (outcome) arrived at by those procedures?

PJ7.Have those procedures upheld ethical and moral standards?

Interactional Justice from Colquitt (Reference Colquitt2001)

The following items refer to (your supervisor who enacted the procedure). To what extent:

IJ1. Has (he/she) treated you in a polite manner?

IJ2. Has (he/she) treated you with dignity?

IJ3. Has (he/she) treated you with respect?

IJ4. Has (he/she) refrained from improper remarks or comments?

IJ5. Has (he/she been candid in(his/her) communications with you.

IJ6. Has (he/she) explained the procedures thoroughly?

IJ7. Were (his/her) explanations regarding the procedures reasonable?

IJ8. Has (he/she) communicated details in a timely manner?

IJ9. Has (he/she) seemed to tailor (his/her) communications to individuals’ specific needs?

Negative Workplace Gossip about a supervisor (NWGS) from Brady, Brown, and Liang (Reference Brady, Brown and Liang2017)

In the last month, how often have you.

NWGS1. asked a work colleague if they have a negative impression of something that your supervisor has done.

NWGS2. questioned your supervisor's abilities while talking to a work colleague.

NWGS3. criticized your supervisor while talking to a work colleague.

NWGS4. vented to a work colleague about something that your supervisor has done.

NWGS5. told an unflattering story about your supervisor while talking to a work colleague.

Negative Workplace Gossip about coworkers (NWGC) from Brady, Brown, and Liang (Reference Brady, Brown and Liang2017)

In the last month, how often have you.

NWGC1. asked a work colleague if they have a negative impression of something that another co-worker has done.

NWGC2. questioned a co-worker's abilities while talking to another work colleague.

NWGC3. criticized a co-worker while talking to another work colleague.

NWGC4. vented to a work colleague about something that another co-worker has done.

NWGC5. told an unflattering story about a co-worker while talking to another work colleague.

Appendix B

Table B1. Exploratory factor analysis