INTRODUCTION

The study outlined here explores the strategic implementation of an organisation-wide wellness intervention, using a mindfulness framework, ‘Be Well at SSI’. The programme was developed in response to the findings of a workforce survey at Settlement Services International (SSI), as a systems-based approach to managing the demands of this high stress workplace in the human services sector.

The term human services is in common usage by various Australian governments at both the Federal and State jurisdictions and refers to a broad range of community services, the portfolio groupings of which vary by jurisdiction and may or may not include primary health. At the time of this study, various organisations in the human services sector were responding to an influx of refugees and people seeking asylum in Australia.

The subject organisation in this study, SSI, was affected more than most; as during its formative growth it was almost solely focused on addressing the settlement needs of this burgeoning group of vulnerable arrivals. The urgent requirements of this growing population contributed to a high-demand workplace, which can generate significant stress and anxiety for employees (Barratt-Pugh & Bahn, Reference Barratt-Pugh and Bahn2015). These factors potentially impact on employees’ health and sense of well-being (Noblet, Graffam, & McWilliams, Reference Noblet, Graffam and McWilliams2008).

Therefore, the Be Well programme of mindfulness-based interventions was implemented to address these emerging workplace stressors through a systems-based approach. The implementation of the programme was supported by changes to organisational culture and strategic policy. Elsewhere, workplace health promotion programmes have tended to target individuals and their coping skills (LaMontagne, Keegel, & Vallance, Reference LaMontagne, Keegel and Vallance2007), without addressing upstream stressors, such as high workloads and organisational culture and frameworks (Safe Work Australia, 2013).

A fundamental driver of SSI’s operational strategy is a commitment to supporting the performance capability and well-being of employees (SSI, People & Organisation Development Strategy, 2016).

In the context of the systems approach championed by Australian researchers (LaMontagne, Keegel, and Vallance, Reference LaMontagne, Keegel and Vallance2007), SSI’s commitment is expressed through various strategic policy (primary) interventions, including:

∙ performance and development (People and Culture Unit);

∙ case management supervision (Clinical Practice Unit);

∙ work health and safety (People and Culture Unit);

∙ Be Well at SSI (Worklife Wellness and SSI’s People and Culture Unit).

At SSI, each of these inter-related commitments moves from strategic policy (primary intervention) into operational practice (secondary interventions) via structured programmes and along referral pathways to remedial or therapeutic practice (tertiary interventions). The purpose and rate of staff participation in tertiary interventions, such as the Employee Assistance Program, in turn, inform the continuous improvement of policy and practice across the organisation.

Be Well, the focus of this study, raises the profile of wellness and helps to develop self-health management skills across SSI’s workforce. It aims to develop coping strategies as well as positive lifestyle choices and is embedded in SSI’s 2016 organisational development strategy. The evaluation of this programme, in reducing stress and improving satisfaction, is the subject of this paper.

Job stress and its effects

In general, healthy work environments are an essential ingredient in improving the health and well-being of Australians (Noblet & LaMontagne, Reference Noblet and LaMontagne2006; Noblet, Graffam, & McWilliams, Reference Noblet, Graffam and McWilliams2008; Pricewaterhouse Coopers, 2010). Job stress has been identified as both a significant risk factor in mental health conditions common amongst the adult population (Stansfeld & Candy, Reference Stansfeld and Candy2006; Gupta, Reference Gupta2008; Blake, Zhou, & Batt, Reference Blake, Zhou and Batt2013; Cleary, Dean, Webster, Walter, Escott, & Lopez, Reference Cleary, Dean, Webster, Walter, Escott and Lopez2014) and as a contributor to physiological conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, and other chronic conditions (LaMontagne, Keegel, & Vallance, Reference LaMontagne, Keegel and Vallance2007). Mental and physical health conditions of employees impact on their productivity, which can be viewed in terms of absenteeism and presenteeism (Pricewaterhouse Coopers, 2010). Research by Caverley et al (2007) found that the relative frequency of various physical and psychological symptoms was strongly correlated with both absenteeism and presenteeism. Ailments commonly included headache, migraine, back and neck pain, cold and flu, respiratory, and symptoms of anxiety and depression. The type and severity of symptoms were consistent across workers who chose to attend or not attend work (Caverley, Cunningham, & MacGregor, Reference Caverley, Cunningham and MacGregor2007).

Given the high workforce participation of adult Australians (Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2017), the workplace is recognised as an important setting in which to address the rising rates of ill health, both physiological and psychological, among the population. The impact of mental stress is significant. Over the past 10 years, mental stress compensation claims have constituted an average of 95% of all mental disorder claims creating the most expensive form of workers’ compensation claims due to the often lengthy periods absent from work, and the substantial economic impact from lost productivity in the workplace (Safe Work Australia, 2013). Additionally, it is reported that 70% of workers who report some experience of work-related mental stress do not apply for workers’ compensation (ABS, 2010), which suggests a significant impact on lost productivity that remains unaccounted. Results from a major Australian study commissioned by Medibank Private, ‘show a clear link between a worker’s health and productivity, with the healthiest employees nearly three-times more effective than the least healthy’ (2005). This report also estimates related financial costs of absenteeism to be $7 billion annually, and of presenteeism at around $25.7 billion annually (Medibank Private, 2005; Pricewaterhouse Coopers, 2010). Additionally, stress-related presenteeism and absenteeism are estimated to cost the Australian economy $14.8 billion per year in lost productivity (Medibank Private, 2008).

Workplace health, engagement and productivity

In research reported by Kuykendall, Tay, and Ng (Reference Kuykendall, Tay and Ng2015) and Bakker, Albrecht, and Leiter (Reference Bakker, Albrecht and Leiter2011) employee self-reported well-being at work is shown to be positively correlated with physiological health (Bakker, Albrecht, & Leiter, Reference Bakker, Albrecht and Leiter2011; Kuykendall, Tay, & Ng, Reference Kuykendall, Tay and Ng2015). One marker of well-being is the concept of work engagement, which has been defined as ‘… a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterised by vigour, dedication, and absorption’ (Schaufeli & Bakker, Reference Schaufeli and Bakker2010). Engagement increases productivity by way of a positive relationship to health and performance. Employees who are engaged report less psychosomatic illnesses, and have better self-rated health (Bakker, Reference Bakker2009; Bakker, Albrecht, & Leiter, Reference Bakker, Albrecht and Leiter2011). Engaged workers also show positive emotions that build enduring psychological resources (Fredrickson, Reference Fredrickson2001). Additionally, these workers have a capacity to create their own personal resources, including optimism, self-efficacy, resilience and an active coping style (Fredrickson, Reference Fredrickson2001).

Bakker, Albrecht, and Leiter (Reference Bakker, Albrecht and Leiter2011) discuss the drivers of engagement as being increased social support, autonomy of job role, provision of opportunities for learning and development, as well as performance feedback from managers.

Work engagement has been found to be facilitated by resilience, indicating that engaged workers can more effectively adapt to changing environments. These workers are not only less susceptible to anxiety, but also show a positive engagement with the work and have an openness to experience (Bakker, Reference Bakker2009). Resilience is thought to buffer the impact of high emotional demands and maintain engagement when job demands are high (Bakker, Schaufeli, Leiter, & Taris, Reference Bakker, Schaufeli, Leiter and Taris2008; Bakker, Reference Bakker2009).

Psychological resilience has been characterised by (1) the ability to bounce back from negative emotional experiences and (2) by flexible adaptation to the changing demands of stressful experiences (Tugade & Fredrickson, Reference Tugade and Fredrickson2007). The capacity to regulate positive emotions is both unconscious and conscious. The experience of positive emotions arises as an unconscious result of physiological stimuli; and, importantly in this context, the quality of that experience and the capacity to consciously apply it, is able to be cultivated in everyday life (Tugade & Fredrickson, Reference Tugade and Fredrickson2007).

In summary, engaged workers cope well with their demands, have a capacity to mobilise their resources, have better resilience, stay healthy and perform well (Bakker, Reference Bakker2009). Self-reported well-being, as a predictor of health, is modifiable, and therefore can be targeted in workplace interventions (Tay & Kuykendall, Reference Tay and Kuykendall2013).

The need for a systems-based approach to workplace health promotion: Theoretical underpinnings

Workplace wellness programmes have been shown to: significantly improve measures of physiological and psychological well-being (Bradley, Horwitz, Kelly, & DiNardo, Reference Bradley2013); reduce costs associated with stress (Pricewaterhouse Coopers, 2010) and ill health (Makrides et al., Reference Makrides, Smith, Allt, Farquharson, Szpilfogel, Curwin, Veinot, Wang and Edington2011; Blake, Zhou, & Batt, Reference Blake, Zhou and Batt2013; Bolnick, Millard, & Dugas, Reference Bolnick, Millard and Dugas2013), and improve performance, productivity and turnover of staff (Gupta, Reference Gupta2008; Bradley et al., Reference Bradley2013; Dane & Brummel, Reference Dane and Brummel2014). However, the issue that remains is that many Australian and international workplace health promotion programmes target individuals and their coping skills (LaMontagne, Keegel, & Vallance, Reference LaMontagne, Keegel and Vallance2007), without addressing upstream stressors including high workloads and organisational culture and frameworks (Safe Work Australia, 2013). These interventions focus on individualised approaches, such as stress management classes or smoking cessation, without altering the workplace or its culture. In failing to address the systemic stressors, evidence suggests that the cumulative effects of each individualised programme is less than the sum of interventions, providing diminishing returns on each additional intervention (Beyond Blue, 2014). This has implications for employee participation, time requirements, prioritising and so forth, highlighting the need for a more comprehensive approach.

Australian researchers, LaMontagne, Keegel, and Vallance (Reference LaMontagne, Keegel and Vallance2007), proposed a theory of a comprehensive, systems-based approach to managing job stress and its effects, in which targeting primary prevention and integrating secondary and tertiary management is essential. In their theoretical model, primary prevention is proactive, with the goal to reduce potential risk factors and/or their impact. Secondary management is ameliorative, the goal of which is to equip workers with knowledge, skills and resources to help them cope better with stressful conditions. Tertiary management is reactive, and its goal is to treat, compensate and rehabilitate workers with lasting symptoms or disease (LaMontagne, Keegel, & Vallance, Reference LaMontagne, Keegel and Vallance2007).

A systemic approach is also proposed in a 2010 report on national developments, commissioned by Medibank Health Solutions, an affiliate of a major insurance company, titled: Workplace Wellness in Australia (Pricewaterhouse Coopers, 2010). It describes the evolution of workplace wellness in Australia, potential barriers and enablers for growth and sustainability. The report issues a ‘Call to Action’ for governments, insurers, employers and employees to make wellness ‘business as usual’ by integrating it within business/operational strategy. An earlier study (Noblet, Reference Noblet2003) suggests that to achieve sustained improvements in the health and productivity of employees, effective programmes must facilitate organisational change at the highest management level. Therefore, the investigation of appropriately comprehensive approaches to workplace wellness programmes is warranted.

Research by Baptiste (Reference Baptiste2008) suggests a clear link between employee well-being and enhanced productivity at work. This research found that management relationships, support and employees’ trust predicted well-being at work. By giving effect to the business case for employee well-being at work, managers can complement more traditional methods of improving employee productivity, which in turn enhance organisational effectiveness. Further, this research posits that failure to evaluate employee well-being comes at the cost of organisational sustainability, and employee and societal well-being (Baptiste, Reference Baptiste2008).

How systemic is SSI’s Be Well programme?

According to the systems approach (LaMontagne, Keegel, & Vallance, Reference LaMontagne, Keegel and Vallance2007) summarised above, interventions can be understood in three categories, primary, secondary and tertiary. This implies primary as an upstream prevention strategy, secondary as individual coping strategies and tertiary as rehabilitation or treatment.

Primary prevention in work health promotion is aimed at preventing exposure to upstream stressors in the workplace. At SSI, the original intention of conducting a workforce-wide health and wellness survey was, in part, to inform the new Chief Executive Officer (CEO)’s organisational development and operational strategy. As a result of the survey, SSI commissioned Worklife Wellness to develop the Be Well programme as a workplace wellness intervention, the goals and strategies of which are fully supported by the executive. This intervention is described below. Staff and management continue to be consulted at regular intervals on matters relating to their ongoing needs and interests and satisfaction with the programme. Consultation occurs by way of workforce surveys (refer to ‘Workplace health and wellness needs and interests survey’ section) and participant surveys (refer to ‘Workshop participation and satisfaction’ section); regular management briefings that draw on operational strategy; and monthly meetings of the staff-run Be Well Committee, who also inform the design and implementation of the programme and ensure it continues to be highly relevant to SSI’s workplace culture.

The preventative narrative of wellness is promoted and sustained at SSI through tailored communications campaigns that link to the organisation’s operational strategy and improve the targeting of messaging. The programme’s tagline, ‘Building wellness together’, encapsulates the wellness culture, which in turn provides the impetus for positive lifestyle choices and workplace behaviours. Importantly, the Be Well programme is embedded in SSI’s employee performance management framework to guide supervisory conversations about positive behaviour change as well as the development of relevant leadership and relationship capabilities throughout the organisation (Baptiste, Reference Baptiste2008).

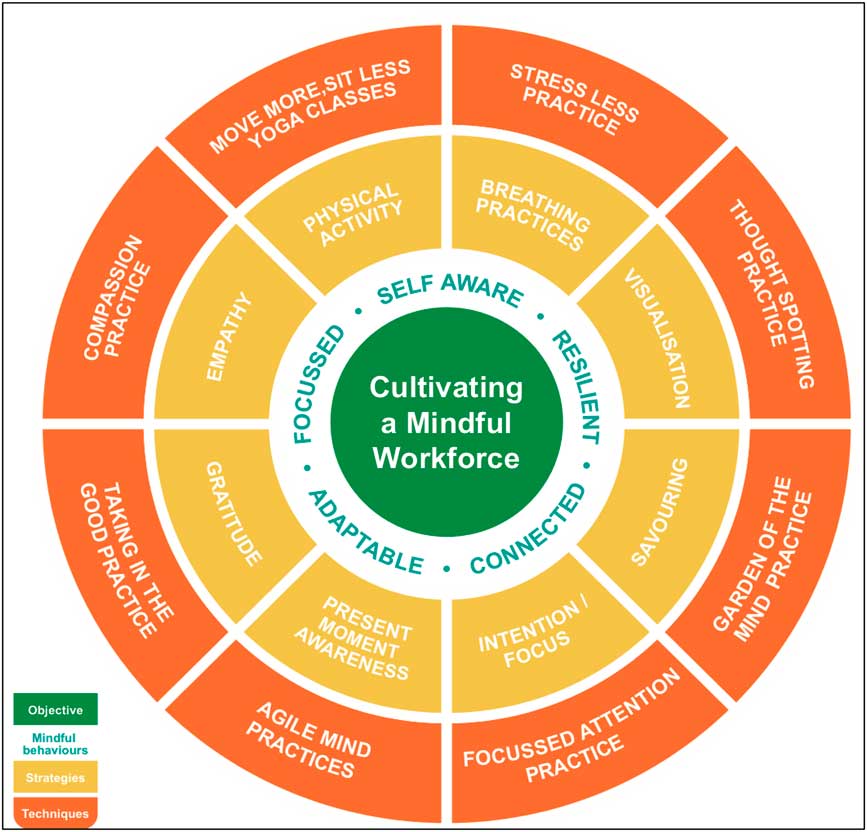

The aim of secondary interventions is to help workers develop better coping skills and be able to respond more appropriately to stressful situations. Strategies include skills development training in areas such as stress management, healthy eating and exercise programmes, as well as interpersonal communications and personal productivity. All training is underpinned by the mindfulness strategies outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Be Well – a multidimensional model of mindfulness in the workplace

The reactive nature of tertiary interventions with a treatment or rehabilitative focus suggests more therapeutic approaches, such as external Employee Assistance Programs. Whilst the Be Well programme at SSI does not directly provide such services, referral pathways are promoted in seminars and induction strategies. Consistent with the systems approach developed by LaMontagne, Keegel, and Vallance (Reference LaMontagne, Keegel and Vallance2007), organisational information about the Be Well programme and activities in this category inform the policies and programmes of higher level interventions, such as clinical supervision, leadership development, and work health and safety strategies. SSI ensured that all executive and management staff attend the Be Well programme and support and accommodate the systemic implementation of strategies promoted by the programme. Managers’ performance reviews are measured with regard to use and support of the programme and address the upstream factors that facilitate the implementation of strategies. This iterative information flow is facilitated via various methods, including personal stories and testimonials; close collaboration between the consultants and the People and Culture team; regular executive briefings; as well as the aforementioned integration of Be Well into SSI’s performance management framework.

In summary, the Be Well programme at SSI integrates across all three levels of the systems approach to health promotion programmes (Noblet & LaMontagne, Reference Noblet and LaMontagne2006; LaMontagne, Keegel, & Vallance, Reference LaMontagne, Keegel and Vallance2007).

Mindfulness and wellness

Mindfulness is closely associated with the ancient contemplative traditions of yoga and Buddhism, both of which draw distinctions between the state of mindfulness in meditation, and is defined as the ability to be mindful in a time limited context (Jislin-Goldberg, Tanay, & Bernstein, Reference Jislin-Goldberg, Tanay and Bernstein2012); and includes the practise of mindfulness, that is, learning to focus attention on observing the present experience, without judgement (de Manincor, Bensoussan, Smith, Fahey, & Bourchier, Reference de Manincor, Bensoussan, Smith, Fahey and Bourchier2015). Ultimately, the basic movement of mindfulness, which is common to both yoga and Buddhist traditions, involves anchoring one’s attention, keeping it there, noticing when the mind wanders, bringing it back and starting again (Goleman, Reference Goleman2013). Active meditation techniques are useful in giving the mind something to do or focus on, for example counting, repeated words or phrases, visualisation and guided meditations (de Manincor et al., 2016); as well as breathing and body scans, loving-kindness and observing-thought meditations (Kok & Singer, Reference Kok and Singer2016). A further range of related tools and techniques are outlined in Figure 1.

In recent years, interventions using mindfulness-based techniques have been shown to reduce stress (Asuero, Queraltó, Pujol-Ribera, Berenguera, Rodriguez-Blanco, & Epstein, Reference Asuero, Queraltó, Pujol-Ribera, Berenguera, Rodriguez-Blanco and Epstein2014), reduce negative feelings and improve resilience and coping (Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, Reference Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt and Walach2004; Dane & Brummel, Reference Dane and Brummel2014).

The benefits of mindfulness to mental health are well established in the literature (Zylowska, Smalley, & Schwartz, Reference Zylowska, Smalley and Schwartz2009; Bohlmeijer, Prenger, Taal, & Cuijpers, Reference Bohlmeijer, Prenger, Taal and Cuijpers2010; Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt, & Oh, Reference Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt and Oh2010; Goleman, Reference Goleman2013; Khoury et al., Reference Khoury, Lecomte, Fortin, Masse, Therien, Bouchard, Chapleau, Paquin and Hofmann2013; Cook-Cottone, Reference Cook-Cottone2015; de Manincor et al., Reference de Manincor, Bensoussan, Smith, Fahey and Bourchier2015, Reference de Manincor, Bensoussan, Smith, Barr, Schweickle, Donoghoe, Bourchier and Fahey2016; Jorm, Reference Jorm2015; Marwaha, Balbuena, Winsper, & Bowen, Reference Marwaha, Balbuena, Winsper and Bowen2015; Crowe, Jordan, Burrell, Jones, Gillon, & Harris, Reference Crowe, Jordan, Burrell, Jones, Gillon and Harris2016). With regard to generalisability, a meta-analysis by Grossman et al., demonstrates that mindfulness was effective in a wide variety of illness and clinical scenarios as well as in nonclinical settings (Grossman et al., Reference Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt and Walach2004). Mindfulness techniques have a proven effect on stress reduction (Aikens et al., Reference Aikens, Astin, Pelletier, Levanovich, Baase, Park and Bodnar2014; Asuero et al., Reference Asuero, Queraltó, Pujol-Ribera, Berenguera, Rodriguez-Blanco and Epstein2014; Dane & Brummel, Reference Dane and Brummel2014); the development of positive affect (Jislin-Goldberg, Tanay, & Bernstein, Reference Jislin-Goldberg, Tanay and Bernstein2012) as well as positive emotions (Fredrickson, Reference Fredrickson1998, Reference Fredrickson2001); and the promotion of resilience (Tugade & Fredrickson, Reference Tugade and Fredrickson2007); and, therefore, have the potential to amplify the positive impact of workplace wellness interventions.

In the study reported here, a comprehensive mindfulness-based workplace wellness programme was implemented in a new and rapidly expanding organisation, SSI. Located in New South Wales, Australia, SSI is a community-based not-for-profit organisation working with vulnerable communities and providing services in the areas of refugee and migrant settlement, asylum seeker assistance, housing, multicultural foster care, disability support and employment services in NSW (SSI, 2015). However, in 2012, the organisation’s primary purpose was the settlement of refugees and asylum seekers. SSI is a high-demand work environment (Kalia, Reference Kalia2002; Caulfield, Chang, Dollard, & Elshaug, Reference Caulfield, Chang, Dollard and Elshaug2004; Medibank Private, 2008) in terms of client needs and in the nature of its early and rapid expansion to accommodate contractual requirements. As such, the holistic philosophy of the Be Well programme and the specifics of the programme’s interventions received strong endorsement from the CEO and the Board of SSI, who supported the proposal to develop a wellness culture as part of strategic operations that would enhance employee engagement, productivity and resilience.

An important feature of the workplace at the commencement of the Be Well intervention was its service delivery to refugee populations, of whom a proportion had experienced trauma in their homelands or in transit to Australia. It is widely recognised that employees working with vulnerable or traumatised clients are at risk of stress, illness, burnout or, more seriously, work induced trauma (Griva & Joekes, Reference Griva and Joekes2003; Hensel, Ruiz, Finney, & Dewa, Reference Hensel, Ruiz, Finney and Dewa2015; Lusk & Terrazas, Reference Lusk and Terrazas2015). Whilst the organisation has since expanded its programme capacity and target populations to migrant populations more generally, the Be Well programme continues to address this risk through an ongoing programme that emphasises self-care, downtime and practical strategies that build resilience and enhance engagement and productivity at work.

ABOUT THE WORKPLACE: SETTLEMENT SERVICES INTERNATIONAL

SSI was established in 2000 as an umbrella organisation for 11 NSW Migrant Resource Centres (MRCs), which were located across the Sydney metropolitan area as well as in Newcastle and Wollongong. In 2011 SSI successfully tendered to deliver Humanitarian Settlement Services to refugees settling in Central and South West Sydney, North West Sydney and Western New South Wales.

Operating in a highly politicised space, the SSI Board resolved early to ensure its clients – many of whom had experienced torture and trauma in their homelands and great hardship on their journey to find new lives in Australia – were settled in welcoming communities (SSI, 2012). This powerfully held conviction continues to guide the service ethos at SSI.

In April 2011, within 2 weeks of signing a 5 year contract with the (then) Department of Immigration and Citizenship, SSI had 180 clients, many of whom had exited immigration detention centres. In the 5 months following, SSI recruited 120 new staff. A new corporate headquarters was acquired to house corporate services and programme administrators, whilst some employees (case managers) were co-located within MRCs across the metropolitan area. Client numbers rose to over 4,000 in the first 12 months.

Since 2012, the organisation has been characterised by rapid growth in its staff and diversification of service delivery; the workforce has grown from 173 to more than 500.

In April 2014, the workforce had grown to 396 in total and was located in 17 sites, most of which were in Western Sydney. This represents a 345% increase in permanent employees (and fixed term contractors), and a 4% increase in casual/contractors and bilingual employees. Overall staffing had increased by 229% in just 2 years (SSI, 2014-15).

ABOUT WORKLIFE WELLNESS

The rationale for the Be Well programme model

During SSI’s phase of organisational expansion from 2012 to 2014, Worklife Wellness was engaged to develop and implement the Be Well programme, which included six training modules delivered in workshops to staff. Worklife Wellness drives positive change through mindfulness-based health and productivity programmes that are tailored to an organisation’s unique needs. Worklife Wellness programmes are underpinned by an evidence-based and comprehensive system-based approach to workplace health promotion that aims to provide sustained change and deliver a return on investment. The comprehensive approach has been shown to strengthen engagement, increase productivity and build resilience (Noblet, Reference Noblet2003). The literature suggests that work engagement is a significant and practical measure for workplace health promotion (Torp, 2013), and is significantly correlated with reduced depression (Torp, 2013; Bakker, 2011, 2008); resilience is associated with the practise of mindfulness-meditation techniques (Tugade & Fredrickson, Reference Tugade and Fredrickson2007) and productivity with the reduction of absenteeism (Colley, Reference Colley2006); all of which are evident in or as a result of the Be Well programme.

To drive workforce engagement in the programme at SSI, the CEO made ‘Work Well’, one of the Be Well training modules, mandatory. The half day Work Well training module mapped the link between stress management, personal productivity and strengthening coping skills through mindfulness.

The Be Well programme

The Be Well programme represents a comprehensive and integrated approach to workplace health promotion, which is supported by the literature (DeFrank & Cooper, Reference DeFrank and Cooper1987; Noblet & LaMontagne, Reference Noblet and LaMontagne2006; LaMontagne, Keegel, & Vallance, Reference LaMontagne, Keegel and Vallance2007; Torp, Grimsmo, Hagen, Duran, & Gudbergsson, Reference Torp, Grimsmo, Hagen, Duran and Gudbergsson2013).

Six separate training modules, described below, were developed to facilitate participants’ development of more psychological and emotional resilience (Tugade & Fredrickson, Reference Tugade and Fredrickson2007; Cohn & Fredrickson, Reference Cohn and Fredrickson2010) and to build personal productivity by improving coping skills and enhancing physical and emotional well-being (Fredrickson, Reference Fredrickson2003; Martin, Reference Martin2005; Cameron, Mora, Leutscher, & Calarco, Reference Cameron, Mora, Leutscher and Calarco2011).

Be Well: A multidimensional model of mindfulness in the workplace

The Be Well model (illustrated in Figure 1) puts the goal of cultivating a mindful workforce at its centre, and encircles the goal with five characteristics of a mindful workforce that have been extrapolated from the literature: focused, self-aware, resilient, connected and adaptable (Rettie, Reference Rettie2003; Tugade & Fredrickson, Reference Tugade and Fredrickson2007; O’Connell, McNeely, & Hall, Reference O’Connell, McNeely and Hall2008; Dickenson, Berkman, Arch, & Lieberman, Reference Dickenson, Berkman, Arch and Lieberman2012; Vago & Silbersweig, Reference Vago and Silbersweig2012). The next circle identifies eight evidence-based strategies; specifically, savouring (Tugade & Fredrickson, Reference Tugade and Fredrickson2007; Bryant, Chadwick, & Kluwe, Reference Bryant, Chadwick and Kluwe2011; Jose, Lim, & Bryant, Reference Jose, Lim and Bryant2012; Smith & Hollinger-Smith, Reference Smith and Hollinger-Smith2015), visualisation and/or gratitude (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, Reference Sheldon and Lyubomirsky2006; Waters, Reference Waters2012); present moment awareness, intention/focus (Killingsworth & Gilbert, Reference Killingsworth and Gilbert2010; Heydenfeldt, Herkenhoff, & Coe, Reference Heydenfeldt, Herkenhoff and Coe2011; Froeliger, Garland, & McClernon, Reference Froeliger, Garland and McClernon2012; Kok & Singer, Reference Kok and Singer2016), empathy (Shapiro, Schwartz, & Bonner, Reference Shapiro, Schwartz and Bonner1998; Block‐Lerner, Adair, Plumb, Rhatigan, & Orsillo, Reference Block‐Lerner, Adair, Plumb, Rhatigan and Orsillo2007; O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Rangan, Berry, Stiver, Rick, Ark and Li2015), physical activity such as yoga (Froeliger, Garland, & McClernon, Reference Froeliger, Garland and McClernon2012; de Manincor et al., Reference de Manincor, Bensoussan, Smith, Fahey and Bourchier2015) and breath regulation (Jerath, Edry, Barnes, & Jerath, Reference Jerath, Edry, Barnes and Jerath2006; Cameron et al., Reference Cameron, Mora, Leutscher and Calarco2011; Froeliger, Garland, & McClernon, Reference Froeliger, Garland and McClernon2012).

These strategies guide the application of related tools and techniques in the outer circle, the inspiration for all of which was drawn from respected sources and adapted for use in the workplace by the consultants who are both qualified and highly experienced teachers and teacher trainers in the classical hatha yoga tradition. The practices include yoga postures that have been modified to mitigate the effects of sedentary work; yogic breathing techniques applied in the context of stress reduction (Jerath et al., Reference Jerath, Edry, Barnes and Jerath2006); a savouring practice, Taking in the Good, drawn from neuroscience (Hanson, Reference Hanson2009); traditional Buddhist practices designed to cultivate compassion (Jazaieri et al., Reference Jazaieri, Jinpa, McGonigal, Rosenberg, Finkelstein, Simon-Thomas, Cullen, Doty, Gross and Goldin2013); Thought Spotting, a practice designed to ameliorate the effects of a wandering mind (Kam, Reference Kam2014); the Garden of the Mind metaphor is applied to a gratitude and appreciation practice (Emmons, Reference Emmons2003; Waters, Reference Waters2012); various traditional and adaptive practices are deployed under the banner of Focussed Attention, including the Agile Mind (Dickenson et al., Reference Dickenson, Berkman, Arch and Lieberman2012; Fergus, Wheless, & Wright, Reference Fergus, Wheless and Wright2014; Marzetti, Di Lanzo, Zappasodi, Chella, Raffone, & Pizzella, Reference Marzetti, Di Lanzo, Zappasodi, Chella, Raffone and Pizzella2014).

It is evident from the literature that the techniques documented here, whilst drawn from neuroscience and the contemplative traditions, are continually evolving through professional practice, experience and evaluation.

The Be Well programme incorporates various mindfulness approaches and offers workers tools to help them refine their mind and behaviours. This accessible toolkit provides participants with techniques that can help them cultivate a sense of well-being and, with practise, become more familiar with their own mental landscape and patterns of behaviour (Vago & Silbersweig, Reference Vago and Silbersweig2012).

Cultivating a mindful workforce

The Be Well programme translates knowledge about mindfulness and positive psychology into an organisational intervention that seeks to cultivate a more mindful workforce whose achievements are reported in this study according to three primary indicators:

(a) Productivity/organisational effectiveness: positive emotions are the possible missing links between the individual’s momentary experiences and long-range indicators of optimal organisational functioning, including satisfaction, motivation and productivity in the workplace (Fredrickson, Reference Fredrickson2003; Martin, Reference Martin2005); which is supported by evidence that human productivity and performance are elevated by the positive more than the negative (Cameron et al., Reference Cameron, Mora, Leutscher and Calarco2011).

(b) Resilience and self regulation: are defined as the ability to marshal positive emotions to guide coping behaviour, allowing for reduced distress and restored perspective (Tugade & Fredrickson, Reference Tugade and Fredrickson2007); and to effectively modulate one’s behaviour (Vago & Silbersweig, Reference Vago and Silbersweig2012).

(c) Work engagement: positive, fulfilling, motivated and work-related well-being that is characterised by vigour, dedication, absorption (Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá, & Bakker, Reference Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá and Bakker2008; Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Schaufeli, Leiter and Taris2009; Bakker, Reference Bakker2011); psychological capital and positive emotions (Avey, Wernsing, & Luthans, Reference Avey, Wernsing and Luthans2008).

STUDY AIM AND OBJECTIVES

The project reported here aims to examine the effect of adding mindfulness to a comprehensive approach to workplace wellness, in terms of reducing sick leave and improving satisfaction compared with stress for workers at SSI, in a high-demand workplace in the human services sector. The research has three objectives. To examine the effectiveness of Be Well, a mindfulness-based wellness programme, in promoting productivity by reducing absenteeism, and building resilience through improved engagement. These outcomes are measured by

(a) sick leave taken by employees in 2014 compared with baseline measures in 2012 as a measure of reduced absenteeism and improved productivity (Shain, Reference Shain2004);

(b) validated questionnaires: Stress satisfaction offset score (SSOS) and Business Health Culture Index (BHCI) in 2014 compared with baseline results from 2012 as a measure of stress compared with satisfaction;

(c) employees’ self-reported satisfaction and engagement with each of the six training modules included in the Be Well programme.

METHODOLOGY

To determine the health-related needs and interests of SSI employees, Worklife Wellness conducted an initial workforce-wide survey in 2012. The Be Well programme was designed to respond to the results of this survey, producing a holistic, systems-based intervention, which incorporated six training modules (see online Appendix A) held in-house at SSI over the course of a 20-month period. The core training module, Work Well, was mandatory for all staff; participation in all other modules was voluntary. SSI encouraged executive and management staff to attend the Be Well programme and support the systemic implementation of strategies promoted by the programme. Performance reviews were measured with regard to use and support of the programme and addressing the upstream factors that facilitated the implementation of strategies.

Two Health and Wellness Surveys (see point (a) below) were sent by email to all staff at two time points; at baseline and at follow up 20 months later. Each survey was open to respondents for a 2-week period. The first baseline survey was sent by email to all staff in April 2012, and the second follow up Health and Wellness Survey was sent in September 2014.

The data were collected via an online survey tool ‘Survey Monkey’, and de-identified data were extracted onto an excel spreadsheet for analysis.

We report on changes over time to sick leave as a proxy measure of wellness or productivity; we also report on the degree of changes in stress and satisfaction via the SSOS, following the implementation of the Be Well programme.

Analysis

The analysis of survey and questionnaire data was performed using statistical package SPSS version 22 (IBM Corp, 2013). Analysis of the data included descriptive statistics to describe the population, t-tests for continuous outcome variables, and χ2 analysis for categorical outcomes. Where the data is nonparametric, a log-transformation is used and a nonparametric test was performed. For regression analysis, the significant results of a univariate analysis were used to construct a multivariate model for examination of what modules from the programme had the most impact on the questionnaire data contained in the SSOS/BHCI.

The SSOS is a validated questionnaire (Shain, Reference Shain1999, Reference Shain2004) that was developed as an initial and brief assessment of health risks, both physical and mental, relating to the work conditions of demand, control, effort and reward. Questions relating to demand and effort are the stress indicators, and those relating to control and reward are indicative of satisfaction.

While the SSOS is an individual measure, the mean or average score can be calculated for the workforce or group as a whole to indicate the BHCI. The BHCI at the organisational level is a simple measure of the extent to which the health culture of an organisation is working for or against its business objectives. Health culture in this context is an examination of the relationship between certain stressors and satisfiers at work. The BHCI can be viewed as a foundation of information on which to work to improve the health and productivity of the organisation. The SSOS is a useful tool and can be viewed at the individual level, team level and then directed towards authentic leadership as the organisation matures and develops.

Sick leave entitlements were compared between 2012 and 2014 as a downstream indicator of workplace stress and absenteeism. As these were from potentially different populations a sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine if the population distributions were statistically different or not in the 2 years, and therefore reliably comparable over the two time points.

Individual factors in the survey or individual workshops were examined for a statistical relationship with the SSOS as a measure of stress/satisfaction.

Ethics requirements

The reporting of these study results is approved by the affiliated University of Notre Dame Australia’s (UNDA) ethics committee (ethics approval number 015052S).

Workplace Health and Wellness Needs and Interests Survey

Using an online survey tool, the authors developed a workplace health and wellness needs and interests survey. All SSI employees were encouraged by the CEO to participate. Aware that the survey could not take too long to complete, it was limited to 50 questions. This included two logic questions enabling respondents to skip topics not pertinent to them (for instance, smoking and alcohol consumption).

After reviewing several needs and interest surveys, the Victorian WorkSafe Workplace Health and Wellbeing Needs Survey was chosen as the most relevant (Victoria WorkSafe, 2010). The survey structure was logical and the questions clear. It also addressed health topics and issues relevant to Australian population health indicators (Begg, Barker, Stevenson, Stanley, & Lopez, Reference Begg, Barker, Stevenson, Stanley and Lopez2007). These include healthy eating and weight, physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption and mental health. The WorkSafe survey included several questions about respondents’ involvement preferences that would help inform programme implementation. These freely available and validated resources are part of Victoria’s comprehensive WorkHealth programme, which are user-friendly and tailored for Australian workplaces (Victoria WorkSafe, 2010).

Evaluation

The main outcome measures used to evaluate the programme were:

∙ amount of sick leave taken in 2014 compared with 2012;

∙ self-reported stress – measured by SSOS/BHCI scores (Shain, Reference Shain2004);

∙ self-reported engagement with training modules;

∙ measurement of association of training modules attended with SSOS.

Sick leave measures were drawn from organisationally reported sick leave in 2014 after the programme’s implementation, compared with sick leave prior to implementation in 2012. The organisation’s head of People and Culture provided general demographic information and sick leave data for this evaluation. Sick leave data was calculated as an average per office location (refer Table 1).

Table 1 Average sick leave for individual sites

The SSOS (Shain, Reference Shain2004) has been applied in the workforce surveys to calculate the four conditions of organisational culture, which disproportionately contribute to stress and satisfaction outcomes in employees: control, demand, effort and reward. The four related factors of demand, control, support and engagement inform the comprehensive workplace health promotion approach, cited above.

The BHCI (Shain & Suurvali, Reference Shain and Suurvali2001) is the average SSOS for the workforce as a whole. It is simply the sum of SSOS for all respondents divided by the number of employees to derive the point estimate for the workplace.

Workshop participation and satisfaction

Since 2012 online training evaluations have been collected from training participants. Just over half (51%) of the employees attended more than one event, and just under half (49%) attended one training event only (modules for training events are described in the online Appendix A).

Table 2 shows participation rates for the training events. These results show that as of 13 April 2014, 294 staff had participated in at least one of the Be Well training courses and, of these, 157 (54%) had attended multiple (between 2 and 6) training events.

Table 2 Be Well – key tndicators of training efficiency (participation)

Includes Be Well core modules×6 only. Excludes Senior Leadership Team Management Retreat, nontraining events, and other bespoke training activities.

Table 3 shows that the 407 participants (68.5% of 594) who responded to the training evaluations reported outstanding levels of satisfaction on all three primary indicators of training effectiveness for each of the modules or training events. Significantly, this table shows that an average of 96.8% of Be Well participants (across all training modules) reported that the training had prompted them to change the way they do things.

Table 3 Be Well – key indicators of training effectiveness (satisfaction)

Employee demographics

In April 2012, SSI employed 173 staff in 10 sites across Western Sydney, the majority of whom had been recruited in the preceding 12 months. In April 2014, the workforce was 396 in total and located in 17 sites, most of which remain in Western Sydney. This represents a 345% increase in permanent employees (and fixed term contractors), 4% increase in casual/contractors and bilingual employees. Overall staffing has increased by 229% in just 2 years. In 2012, the average age was in the range of 20–29. However, by 2014 the average age was in the range of 30–39 (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Average age of Settlement Services International employees 2012 and 2014

Of the 2014 respondents 65% were female, and 35% male, which is largely representative of the organisation’s demographic. It was evident that the respondents were mainly nonsmokers, the rate of which roughly reflected the Australian average (ABS, 2015); had high educational attainment; represented all age demographics; and the majority had worked at SSI for longer than a year. The numbers of those born in Australia increased since 2012. Diversity in the workforce has remained strong with over 20 countries of birth and 52 language groups represented in the 2014 data.

While potentially a different cohort, the employees in 2012 were similar to the employees in 2014 in the proportion of those who smoked, consumed alcohol, and the relative proportions of males and females. These potentially confounding factors were not significantly different between the two cohorts studied.

The majority of respondents were from four main offices, and the remaining 21.6% were from the 10 satellite offices. Given that there are two office sites in one location, accommodating the largest number of employees (139), the higher proportion of responses in a single location is to be expected (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Location of respondents

RESULTS

These results report on the Be Well programme, and are examined in three parts. First, using sick leave data for all employees, we examined rates of sick leave at two times: baseline data in 2012 and subsequent to the introduction of the Be Well programme in 2014. Second, using the results from a validated questionnaire (Shain, Reference Shain2004), we examined reported stress levels for individuals using the SSOS, and the related measure at the business level, using the BHCI. Finally, to examine self-reported satisfaction and engagement with each of the training modules we examined participant scores for each individual module.

Primary outcomes

Sick leave measures

Sick leave was employed as a proxy measure for workplace stress in the study. Across 11 sites, average sick leave per person was calculated at baseline in 2012, and again at follow up in 2014. There was variation across the sites ranging from an average of 0.26 days per person to 0.95 days per person taken as sick leave in 2012. In 2014, average sick leave per person ranged from 0.03 to 0.1 days per person across the 11 sites.

Using a t-test to compare the mean difference in average overall sick leave taken, we compared the average across all of the 11 sites in 2012 (0.55 days), to the average in 2014 (0.06 days). The results demonstrate a significant reduction in sick leave taken in 2014 compared with 2012 (mean difference=0.49 (95% CI 0.34, 0.64) p<.001) (Table 4).

Table 4 t-Test comparison of average sick leave across all sites 2012 versus 2014

Stress satisfaction offset score

The SSOS and BHCI were used to examine reported levels of stress at both the individual employee level (SSOS), as well as at the business level (BHCI). To determine if any reduction in stress was evident, we examined baseline scores obtained in 2012 and compared these with post-intervention scores in 2014.

Participants ranked their responses on a scale of −2 to +2, where −2 to −0.1 correlates to greater perceived stress, and where +0.1 to +2 correlates to greater perceived satisfaction. A score of 0 indicates equal stress and satisfaction (see Table 5). Whilst the number of respondents is quite different in each sample, an analysis of variance showed a normal distribution in both sample populations.

Table 5 Stress satisfaction offset score 2012 and 2014

In 2012 the mean SSOS, indicating the BCHI, was 0.82. People reported that, on average, they were between equal stress and satisfaction and slightly more satisfaction than stress. In 2014, the mean score, or BCHI, was 1.23 showing that on average, people were between slightly more satisfaction than stress, and more satisfaction than stress. These results are shown in Table 5.

We compared the change in the BCHI from 2012 to 2014. Using a t-test to compare means there was an average increase from 0.82 to 1.23, indicating an increase of 0.41 (p<.05) between 2012 and 2014 results. This confirms that since 2012, work-related stress has been significantly reduced and job satisfaction increased at SSI.

Secondary outcomes

Self-reported engagement with training modules

Workshop participation rates and the perceived usefulness rating of each workshop were analysed and mapped to the individual and business level SSOS (see Table 5).

All respondents (100%) rated each of the Be Well activities as helpful in some way (between somewhat helpful and very helpful). The six most well attended activities were: Work Well; Stress Less; Supervision in Focus; Communicating Clearly; Yoga; and Move Toward Your Goals.

The average score for each workshop was also calculated (Table 6). The helpfulness of each of these six activities was confirmed with an average score of 3 and over. The remaining workshops or initiatives had an average score of 2.73 or more. These results show a high satisfaction with the workshops offered and were applied in the planning process to ensure a focus on activities with the highest impact.

Table 6 Activity participation and helpfulness

Using univariate analysis, those workshops that had a significant relationship with the SSOS were analysed. Further, multivariate analysis was used to build a model of the factors that most significantly contributed to the increased SSOS results.

Factors that had a significant correlation with reduced stress and increased job satisfaction included participation in: Yoga; Move Toward Your Goals; Stress Less; and Work Well.

Through statistical modelling of variance (multivariate analysis) the three factors most predictive of a reduced stress and higher job satisfaction were participation in Stress Less, Yoga and Work Well (see Table 7).

Table 7 Multivariate model predicting stress satisfaction offset score

Future workplace health and wellness activities

Participants were presented with a list of nine future wellness training activities, to which 221 people responded, and participants could nominate their attendance preferences. The five workshops with the highest response rates were: sleeping better naturally (n=112, 50.7%); eating for wellness (n=111, 50.2%); building emotional resilience (n=107, 48.4%); practical stress management tools (n=99, 44.8%); and mindfulness training (n=96, 43.4%) (for a full list of responses, see Figure 4). The workshop with the highest response rate was ‘sleeping better naturally’. In response to Q.19, Do you feel rested when you wake up in the morning (n=111, 45.5%) respondents stated that they did not feel rested when they woke up in the morning. These respondents were statistically more likely to identify that the Sleeping Better naturally workshop was of interest. As a further stress reduction measure, enhancing sleep quality may be an important indicator of stress levels for SSI employees, and a good target for future workshops.

Figure 4 Interest in attending future Be Well training

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This study aimed to evaluate the effects of introducing a systems-based workplace wellness programme ‘Be Well’ to the SSI workforce. It demonstrated significant reductions in sick leave and increased satisfaction compared with stress scores for employees. It provides an effective example of a systems-based approach to wellness interventions that may be generalisable across the human services sector.

The results from this study contribute to the evidence for a workplace wellness intervention using a systems-based approach in the human services sector. At the organisational level, the improvement in the BHCI suggests that SSI’s culture is aligned with its business objectives, and has successfully incorporated changes in strategic policy and operational strategy.

The systems-based approach to workplace wellness, as advocated by Noblet addresses upstream stressors and incorporates organisational change at the management level (Noblet, Reference Noblet2003). This has been shown to be more effective than health promotion that targets individuals and their coping skills (Noblet, Reference Noblet2003; LaMontagne, Keegel, & Vallance, Reference LaMontagne, Keegel and Vallance2007; Safe Work Australia, 2013). Noblet’s work describes how the characteristics of ‘social support’ and ‘job control’ account for most of the variance in job satisfaction (Noblet, Rodwell, & McWilliams, Reference Noblet, Rodwell and McWilliams2001; Noblet, Reference Noblet2003). In their 2008 paper, Noblet et al., found that these characteristics, along with some sector-specific stressors, should be targeted by programmes to address negative effects of large-scale organisational change (Noblet, Graffam, & McWilliams, Reference Noblet, Graffam and McWilliams2008). However, these studies provided no programme to address the issues.

Mindfulness techniques have also been shown to be effective in reducing the physiological impacts of workplace stress, and effective in building resilience among workers (Grossman et al., Reference Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt and Walach2004; Asuero et al., Reference Asuero, Queraltó, Pujol-Ribera, Berenguera, Rodriguez-Blanco and Epstein2014; Dane & Brummel, Reference Dane and Brummel2014). However, systematic approaches to workplace wellness programmes using mindfulness have not been previously addressed.

The Be Well programme has been instrumental in improving employees’ responses to stress and taking positive steps towards changing modifiable health behaviours and outcomes. Given the substantial burden of mental health costs in the workplace (Safe Work Australia, 2013), and its implications for the human services sector, Be Well adds significantly to the evidence for a systems-based wellness intervention.

The strengths of this research are in the broad inclusion of participants, the high response rate, the diversity of backgrounds and the stressful nature of the work. This has broad applicability and generalisability for other workplaces in Australia and internationally.

Limitations include the study’s ability to take only indirect measures of stress by the use of sick leave data. The outcomes taken in conjunction with stress and satisfaction scores and managers’ survey responses is seen as a holistic picture of the greater effects of the Be Well programme. Reducing absenteeism is one of the goals of the programme and an indicator of wellness and, therefore, productivity, although it is not a direct measure of wellness. However, reduced worker turnover and sick leave indicate greater levels of satisfaction.

Being a pragmatic study, using evaluation data drawn from a rapidly expanding workforce, the sample in 2012 compared with 2014 were not necessarily the same cohorts. Nonetheless, we can see from the population data that these participants did not significantly differ in 2014 from 2012 in terms of gender, smoking and alcohol status.

Other limitations are that some workshops were less well attended, such as Team Leader Communication, as it was not indicated for all staff. This may have led to small numbers for the specific analysis and consequently may not have shown a relationship. A larger sample of team leaders and managers is required for a more robust analysis of those results.

As indicated by the Australian Government’s Mental Health Commission (Harvey, Joyce, Tan, Johnson, Nguyen, & Modini, Reference Harvey, Joyce, Tan, Johnson, Nguyen and Modini2014), developing a mentally healthy workforce requires commitment across public and private sectors at all levels of the workplace, and focuses on working flexibly, building resilience, developing better work cultures and supporting employees with early intervention and recovery strategies.

The Be Well programme has broad applicability as it is able to be scaled and tailored according to workforce survey results and has addressed the key aspects of building a mentally healthy workplace with an effective and comprehensive evidence-based programme incorporating mindfulness techniques.

Increased demand for human services in Australia, and internationally, requires a thoughtful management approach to mitigate risks to employees and to enable the provision of high level services to potentially vulnerable clients.

The comprehensive mindfulness programme, Be Well, provides a systems-based approach to workplace wellness. The programme recognises that employees require control over aspects of their work and work–life engagement to offset high demand in their roles. This is increasingly relevant in a globalised work arena. The programme addresses upstream stressors by (a) acknowledging the responsibility of management for implementing an appropriate policy framework, (b) providing training in mindfulness-based tools and techniques at the individual level to reduce stress, (c) providing access to rehabilitation or treatment services. This study offers a unique contribution to the workplace wellness agenda through a systems-based approach and the use of mindfulness-based tools. The literature has so far examined each of these contributions individually, however this study shows the effects of a combined programme to reduce stress and absenteeism, and improve work satisfaction.

The programme has shown potential to minimise costs due to reduced absenteeism, and therefore increased productivity in this high stress workplace. This case study provides a valuable addition to the evidence and informs the implementation of sustainable programmes in the public and not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Executive at SSI, the Board of Directors and management team for their support and assistance.

Financial Support

Worklife Wellness was commissioned by SSI to design and develop a programme to improve the health and well-being of employees. This study has received no financial contribution.

Conflicts of Interest

Worklife Wellness is contracted to provide the Be Well programme at SSI and as such has an interest in the study.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2017.41