Introduction

The unwillingness of employees to speak up about issues, concerns, or ideas at work (i.e., employee silence) has received considerable research attention over the years (for a review, see Brinsfield, Edwards, & Greenberg, Reference Brinsfield, Edwards and Greenberg2009). Scholars have learned that employee silence may impact important organizational, group, and individual outcomes (e.g., reduced innovation, lower engagement, psychological/physiological problems, perpetuation of unethical behaviour; Argyris & Schön, Reference Argyris and Schön1978; Cortina & Magley, Reference Cortina and Magley2003; Clapham & Cooper, Reference Clapham and Cooper2005). Scholars have also learned that a wide array of factors may contribute to employee silence (e.g., employee silence motives, trust, implicit voice theories, psychological safety, leadership style LePine & Van Dyne, Reference LePine and Van Dyne1998; Morrison & Milliken, Reference Morrison and Milliken2000; Vakola & Bouradas, Reference Vakola and Bouradas2005; Detert & Edmondson, Reference Detert and Edmondson2011; Brinsfield, Reference Brinsfield2013). Moreover, as economic and social environments become more complicated, organizations are faced with increasing ambiguity, unforeseen ethical dilemmas, and a heightened need for rapid innovation and adaptation – in these environments it is even more imperative that employees do not feel reluctant to express themselves (Bennis, Goleman, & O’Toole, Reference Bennis, Goleman and O’Toole2008). Unfortunately, however, as Morrison and Milliken (Reference Morrison and Milliken2000) assert, a climate of silence often appears to be the norm.

Prior research has found that leader behaviours can have a significant impact on employees’ willingness to express themselves (e.g., Detert & Burris, Reference Detert and Burris2007; Walumbwa & Schaubroeck, Reference Walumbwa and Schaubroeck2009; Duan, Lam, Chen, & Zhong, Reference Duan, Lam, Chen and Zhong2010). These effects can occur for a number of reasons including leaders impacting the opportunities for, the perceived instrumentality of, and the perceived risks associated with, speaking up (see Ashford, Sutcliffe, & Christianson, Reference Ashford, Sutcliffe and Christianson2009). Moreover, much of this research has found that the more open and supportive the leader (as reflected in high trust, approachability, open to ideas, high leader–member exchange, etc.), the more positive will be the employee’s perceptions of opportunity, instrumentality, and safety, and the more likely she will be to speak up (see Morrison, Reference Morrison2011). However, the way that particular leader behaviours shape these perceptions is influenced by the context in which they are enacted (see Avolio, Sosik, Jung, & Berson, Reference Avolio, Sosik, Jung and Berson2003). For example, a leadership theory that suggests a democratic leadership style is ideal may not generalize to cultures where an unequal distribution of power is accepted as the norm (Dorfman & Howell, Reference Dorfman and Howell1988; Jung, Bass, & Sosik, Reference Jung, Bass and Sosik1995). Therefore, leader behaviours that attenuate employee silence in one context may not have similar effects in a context where those behaviours are perceived differently.

There is a long history of research that has examined how Chinese culture may differ from Western cultures (e.g., Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1980). One notable finding from this research is the greater extent to which authoritarian leadership practices (i.e., restricts autonomy, controls information, threatens punishment for disobedience; Aryee, Chen, Sun, & Debrah, Reference Aryee, Chen, Sun and Debrah2007) are expected, endorsed, and enacted in China (see Fu, Wu, Yang, & Ye, Reference Fu, Wu, Yang and Ye2008). Scholars contend this is due to the cultural traditions of paternalism, Legalism, and Confucianism that have nourished authoritarian leadership in China and continue to encourage its practice (Cheng, Chou, Wu, Hwang, & Farh, Reference Cheng, Shieh and Chou2004).

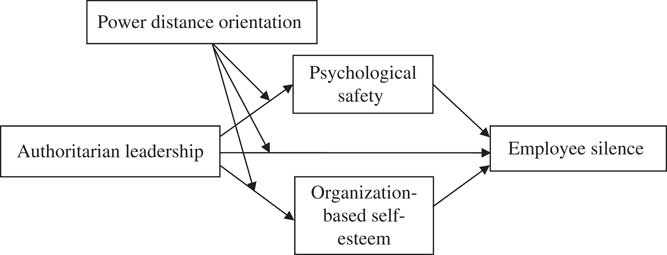

Based on the extant research on employee silence, the behaviours that exemplify authoritarian leadership would appear to be antithetical to those who encourage employee willingness to speak up. In China, however, it is not clear if this is the case because of the cultural traditions that underpin authoritarian leadership and shape how employees perceive and respond to it. We believe this represents a critical gap in our knowledge considering the prevalence of authoritarian leadership in China (see Farh, Cheng, Chou, & Chu, Reference Farh, Cheng, Chou and Chu2006) and the effects employee silence can have on individuals and organizations. Moreover, the person–environment (PE) fit literature provides reasons to suspect that the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence is not uniform across individuals. Instead, it is likely that differences in employees’ expectations and acceptance that power is distributed unequally will affect the direction and/or strength of this relationship. Therefore, in this study we examine the effect of authoritarian leadership on employee silence behaviour in Chinese state-owned manufacturing organizations. To deepen our understanding of the nature of this relationship, we also examine the moderating influence of power distance orientation (PDO), and the mediating roles of psychological safety and organization-based self-esteem (OBSE). We discuss next our theoretical rationale for examining each of these factors and present hypotheses regarding their relationships.

Theory and Hypotheses

The relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence

Cheng et al. defined authoritarian leadership as the ‘leader’s behavior that asserts absolute authority and control over subordinates and demands unquestionable obedience from subordinates’ (Reference Cheng, Shieh and Chou2004: 91). Tsui, Wang, Xin, Zhang, and Fu (Reference Tsui, Wang, Xin, Zhang and Fu2004) noted that an authoritarian leadership style emphasizes personal dominance over employees, makes unilateral decisions, and centralizes authority on her- or himself. Similarly, Aryee et al. (Reference Aryee, Chen, Sun and Debrah2007) noted that authoritarian leaders tend to initiate structure, provide the information, issue the rules, determine what is to be done, promise rewards for compliance, and threaten punishments for disobedience. This style of leadership stands in stark contrast to democratic and egalitarian styles of leadership wherein followers are encouraged to join in deciding what is to be done (Bass, Reference Bass1990; Aryee et al., Reference Aryee, Chen, Sun and Debrah2007).

Prior research has found that authoritarian leadership can have desirable and/or undesirable effects on followers. For example, Wu and Liao (Reference Wu and Liao2013) found that authoritarian leadership can reduce feelings of uncertainty and attenuate the negative effects of procedural and distributive injustice on job satisfaction. Cheng et al. (Reference Cheng, Shieh and Chou2004) found that authoritarian leadership was positively related to identification, compliance, and gratitude for employees who identified with traditional Chinese cultural values. Similarly, Farh et al. (Reference Farh, Cheng, Chou and Chu2006) found that authoritarianism had a negative effect on satisfaction with the leader for subordinates with a low endorsement of traditional Chinese values, but it had no such negative effect for those with a high endorsement.

More research on authoritarian leadership, however, has found it to be associated with less desirable outcomes. For example, studies have found that supervisors’ authoritarian behaviour evoked negative emotions in subordinates, such as anger, hostility, and fear (Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson1996; Wu, Hsu, & Cheng, Reference Wu, Hsu and Cheng2003; Farh et al., Reference Farh, Cheng, Chou and Chu2006). Others have found that authoritarian leadership can cause employees to suppress negative emotions which can have deleterious effects on well-being (Chu, Reference Chu2014). Authoritarian leadership has also been found to be negatively associated with team members’ commitment to, and satisfaction with, team leaders (Cheng, Huang, & Chou, Reference Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang and Farh2002), loyalty towards leaders, trust in leaders, and organizational citizenship behaviour (Cheng, Shieh, & Chou, Reference Cheng, Huang and Chou2002). Moreover, many of these same outcomes also have been shown to be associated with employee willingness to express themselves (e.g., Brockner et al., Reference Brockner, Ackerman, Greenberg, Gelfand, Francesco, Chen and Shapiro2001; Van Dyne, Ang, & Botero, Reference Van Dyne, Ang and Botero2003; Detert & Burris, Reference Detert and Burris2007; Kish-Gephart, Detert, Trevino, & Edmondson, Reference Kish-Gephart, Detert, Trevino and Edmondson2009).

Most conceptualizations and definitions of employee silence characterize it as the intentional withholding of meaningful information, including suggestions for improvement, questions, and concerns (see Morrison & Milliken, Reference Morrison and Milliken2000; Tangirala & Ramanujam, Reference Tangirala and Ramanujam2008; Duan & Huang, Reference Duan and Huang2013). Employee silence does not refer to the unintentional failure to communicate that might come from having nothing to say or mindlessness (Van Dyne, Ang, & Botero, Reference Van Dyne, Ang and Botero2003). Initial interest in employee silence arose because it was believed to be phenomenologically distinct from simply an absence of employee voice behaviour (see Pinder & Harlos, Reference Pinder and Harlos2001; Van Dyne, Ang, & Botero, Reference Van Dyne, Ang and Botero2003). Although, scholarly opinions differ on the validity and nature of this distinction (see Brinsfield, Reference Brinsfield2014; Morrison, Reference Morrison2011), there is evidence that an absence of employee silence is not necessarily indicated by the presence of voice behaviour (Van Dyne, Ang, & Botero, Reference Van Dyne, Ang and Botero2003; Brinsfield, Reference Brinsfield2013). Similarly, scholars have suggested that distinguishing silence from voice is important because their antecedents may differ. For example, proactive personality may be a positive predictor of voice because proactive people notice more things to speak up about. However, proactive people may also frequently remain silent for a variety of different reasons (Kish-Gephart et al., Reference Kish-Gephart, Detert, Trevino and Edmondson2009).

Several different explanations for employee silence have been identified in the literature. One of the most prevalent of these is silence based on the fear of consequences associated with speaking up. For example, Pinder and Harlos (Reference Pinder and Harlos2001) used the term quiescent silence to describe deliberate omission based on the fear of the consequences associated with speaking up. Similarly, Morrison and Milliken (Reference Morrison and Milliken2000) asserted that the emotion of fear is often a key motivator of organizational silence. Milliken, Morrison, and Hewlin (Reference Milliken, Morrison and Hewlin2003) found that 22.5% of participants reported fear of retaliation or punishment as a reason for not speaking up about concerns or problems in the workplace. Van Dyne, Ang, & Botero also proposed this dimension of employee silence and defined it as ‘withholding relevant ideas, information, or opinions as a form of self-protection, based on fear’ (Reference Van Dyne, Ang and Botero2003: 1367). This reason for silence is also similar to the type of workplace silence that Detert and Edmondson (Reference Detert and Edmondson2011) investigated with regard to implicit voice theories. These implicit voice theories represent taken-for-granted beliefs about when and why speaking up at work is risky or inappropriate. Five different implicit voice theories emerged from their research, all of which involve different beliefs about remaining silent in order to not appear threatening or offensive to one’s boss. Similarly, Brinsfield (Reference Brinsfield2013) also identified fear of consequences (i.e., defensive silence) as a common motive for remaining silent.

Reasons other than fear of consequences have also been identified. For example, Morrison and Milliken (Reference Morrison and Milliken2000) described a climate of silence as characterized, in part, by the shared belief that speaking up about problems is often not worth the effort. Pinder and Harlos (Reference Pinder and Harlos2001) conceptualized acquiescent silence based on a deeply felt acceptance of organizational circumstances and giving up hope for improvement. Milliken, Morrison, and Hewlin (Reference Milliken, Morrison and Hewlin2003) found that 25% of participants reported remaining silent due to feelings of futility. Similarly, Brinsfield (Reference Brinsfield2013) identified ineffectual and diffident motives for silence. The ineffectual motive is characterized as a general belief that speaking up would not be useful for achieving a desired change. The diffident motive concerns one’s insecurities, self-doubt, or uncertainties regarding the situation or what to say.

Based on this prior research one might expect that these aforementioned reasons for silence could be exacerbated by authoritarian leadership. Authoritarian leaders expect unquestioning obedience, and hence, may signal to employees that challenging them would be met with retribution. The decision to remain silent in such situations can be explained by a wide range of theory that demonstrates that people are motivated to engage in behaviours that lead to desired outcomes or prevent undesired outcomes (e.g., approach-avoidance, expectancy theory, James, Reference James1950; Vroom, Reference Vroom1964). Hence, when people expect that speaking up will be met with an undesirable outcome (e.g., reprisal) they choose silence as the behavioural option (Morrison & Milliken, Reference Morrison and Milliken2000).

This reasoning is further reinforced by a wide range of research on the effects of supervisor and leader behaviours on employee voice and other related constructs (e.g., issue selling, whistle-blowing, spirals of silence; see Noelle-Neumann, Reference Noelle-Neumann1974; Ashford, Rothbard, Piderit, & Dutton, Reference Ashford, Rothbard, Piderit and Dutton1998; Detert & Burris, Reference Detert and Burris2007; Miceli, Near, & Dworkin, Reference Miceli, Near and Dworkin2008). Much of this work has focussed beliefs about the risks and efficacy associated with speaking up which stem from perceptions that one’s manager is approachable, fair, and interested in their input (Detert & Burris, Reference Detert and Burris2007; Morrison, Reference Morrison2011). Therefore, we propose

Hypothesis 1: Authoritarian leadership is positively related to employee silence behaviour.

Mediating roles of psychological safety and organization-OBSE

Psychological safety entails people’s feelings and judgements about the consequences of interpersonal risk-taking at work (see Kahn, Reference Kahn1990; Edmondson, Reference Edmondson1999). Although Edmondson’s definition of psychological safety as ‘a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking’ (Reference Edmondson1999: 354) represents a collective-level phenomenon, this construct has also been adapted to measure individual-level perception (e.g., Detert & Burris, Reference Detert and Burris2007). In this study, we are interested in individual-level perceptions of psychological safety.

Leadership behaviour affects psychological safety because leaders have the authority to administer rewards and punishments, and this power over subordinates’ promotions, pay, and job assignments makes leaders’ actions very salient as cues for acceptable behaviour (Depret & Fiske, Reference Depret and Fiske1993). Edmondson (Reference Edmondson2004) proposed three aspects of leader behaviour that will promote psychological safety: being available and approachable, explicitly inviting input and feedback, and modelling openness and fallibility – all of which appear to be antithetical to authoritarian leadership. In contrast, authoritarian leaders often emphasize their authoritative positions and abuse power to perform tasks regardless of subordinates’ feelings. They may excessively criticize or rebuke subordinates for minor mistakes as a warning to others. They rarely model openness, vulnerability, or admit mistakes (see Farh & Cheng, 2000). Such leadership behaviours send clear and threatening signals to subordinates, and generate a fearful working environment, creating low psychological safety (Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2008).

Psychological safety has been widely implicated in employee silence and voice (see Detert & Edmondson, Reference Detert and Edmondson2011). In fact, Kahn’s description of psychological safety as ‘feeling able to show and employ one’s self without fear of negative consequences to self-image, status, or career’ (Reference Kahn1990: 708), reflects the defensive motive for employee silence identified in the literature (see Van Dyne, Ang, & Botero, Reference Van Dyne, Ang and Botero2003; Brinsfield, Reference Brinsfield2013). Moreover, much of the prior research on employee voice and silence has explicitly or implicitly placed psychological safety as a mediator between antecedent variables and voice or silence behaviour (Detert & Edmondson, Reference Detert and Edmondson2011). This is because psychological safety can decrease the amount of risk perceived in the cost-benefit equation of the voice or silence decision (see Edmondson, Reference Edmondson2003). Detert and Burris (Reference Detert and Burris2007), for example, showed that employee perceptions of psychological safety mediated the positive relationship between managerial openness (i.e., subordinates’ perceptions that their boss listens to them, and gives fair consideration to the ideas presented) and employee voice. Research focussed specifically on employee silence has generally found a negative relationship between psychological safety and employee silence. For example, Brinsfield (Reference Brinsfield2013) found that psychological safety was negatively related to the relational, defensive, and diffident employee silence motives. Considering the potential for authoritarian leadership to impact psychological safety, and the subsequent impact of psychological safety on employee silence, we propose

Hypothesis 2: Psychological safety mediates the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence behaviour.

Self-esteem refers to an individual’s overall self-evaluation of his/her competencies (Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg1965), as well as an affective (liking/disliking) component (Pelham & Swann, Reference Pelham and Swann1989). Building on the concept of self-esteem, Pierce, Gardner, Cummings, and Dunham developed the concept of OBSE which they defined as ‘the degree to which organizational members believe that they can satisfy their needs by participating in roles within the context of the organization’ (Reference Pierce, Gardner, Cummings and Dunham1989: 625). It also entails the belief that one is a capable, significant, and worthy organization member (Pierce & Gardner, Reference Pierce and Gardner2004). Gardner, Van Dyne, and Pierce (Reference Gardner, Van Dyne and Pierce2004) suggest that organizational members can assess their value through the signals communicated by the organization and managers. Specifically, the characteristics of different management systems and practices will let employees construct different organizational experiences and form various levels of OBSE (Pierce & Gardner, Reference Pierce and Gardner2004). Because employees under authoritarian leadership are less likely to have any (real) authority, they are less likely see themselves as vital members of an organization. This may undermine their feeling of self-competence resulting in low OBSE (Yin, Wang, & Huang, Reference Yin, Wang and Huang2012).

Similarly, employees’ perception of self-value is negatively affected when there is less managerial recognition and appreciation (Lee & Peccei, Reference Lee and Peccei2007). Since authoritarian leaders expect employees to rigidly follow their directives, they are more likely to only praise employees when they are behaving in accord with these directives. This may lead to employees receiving recognition in a narrower band of controlled circumstances – subsequently, OBSE is diminished. Furthermore, autonomy has been linked to self-esteem across a range of psychological inquiry (see Tharenou, Reference Tharenou1979; Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan1987). Since authoritarian leaders limit employee autonomy, it is likely that this style of leadership further contributes to attenuated OBSE. Moreover, prior research has found self-esteem to be associated with employee voice and/or silence behaviour. For example, high self-esteem has been found to have a positive influence on people’s expressive behaviours (LePine & Van Dyne, Reference LePine and Van Dyne1998). Similarly, Pinder and Harlos (Reference Pinder and Harlos2001) proposed that lower self-esteem would lead to employee silence. Although OBSE is built upon individual-based self-esteem, it is anchored in an organizational frame of reference and is shaped by employees’ experience of working in specific organizations. Therefore, OBSE will have a more distinctive influence on work attitudes and behaviours than global self-esteem (Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Gardner, Cummings and Dunham1989).

Studies have already confirmed a positive correlation between OBSE and employee voice behaviour (e.g., LePine & Van Dyne, Reference LePine and Van Dyne1998; Liang, Farh, & Farh, Reference Liang, Farh and Farh2012). One reason for this is that OBSE can make employees feel more responsible for expressing opinions and making suggestions (Liang, Farh, & Farh, Reference Liang, Farh and Farh2012). People with high OBSE are also more likely to believe that their perspectives are correct and that their speaking up will have a positive impact (Pierce & Gardner, Reference Pierce and Gardner2004). As a result, high OBSE will result in a lower level of employee silence. Considering the potential for authoritarian leadership to impact OBSE, and the subsequent impact of OBSE on employee silence, we propose

Hypothesis 3: OBSE mediates the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence behaviour.

PDO as a moderator

Power distance is defined as the extent to which a society accepts that power in institutions and organizations is distributed unequally (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001). Researchers also have found that power distance has large variation over individuals in society and these differences affect many outcomes (e.g., Clugston, Howell, & Dorfman, Reference Clugston, Howell and Dorfman2000). The term PDO is used to refer to power distance at the individual level of analysis and to distinguish it from power distance at the societal level of analysis (see Kirkman, Chen, Farh, Chen, & Lowe, Reference Kirkman, Chen, Farh, Chen and Lowe2009). Moreover, some scholars argue that a focus on an individual level is more appropriate when a society is in a time of transition (see Chen & Aryee, Reference Chen and Aryee2007).

PDO has been found to influence how individuals perceive and react to authority (e.g., Kirkman et al., Reference Kirkman, Chen, Farh, Chen and Lowe2009). From a theoretical perspective, much of the reasoning for this stems from the extent that follower’s values and expectations align or ‘fit’ with those of the leader. This line of reasoning also is consistent with findings from the PE fit literatures showing the effects of fit on a broad range of outcomes (e.g., well-being, commitment, satisfaction, uncertainty, etc.; see Kristof-Brown & Billsberry, Reference Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman and Johnson2013).

Because high PDO followers’ values and expectations are more in alignment with authoritarian leadership practices (see Javidan, Dorfman, de Luque, & House, Reference Javidan, Dorfman, de Luque and House2006), they are more likely to defer to the leader’s judgement, less likely to challenge the leader, and more likely to withhold their viewpoints (see Van Dyne & LePine, Reference Van Dyne and LePine1998; Javidan et al., Reference Javidan, Dorfman, de Luque and House2006; Li & Sun, Reference Li and Sun2015). We therefore propose

Hypothesis 4: PDO moderates the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence behaviour. That is, when employee PDO is high, the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence behaviour is stronger.

The moderated-mediation model

In addition to the moderating effect of PDO hypothesized above, PDO may also affect the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence via the mediating roles of psychological safety and OBSE. The reason this may occur with regard to psychological safety also is grounded in research on person–environment fit and other types of supervisory behaviours. For example, Tepper (Reference Tepper2007) suggested that abusive supervision may be less impactful for individuals with a high PDO. The rational for this is since abusive supervision is more common in high power distance cultures (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1980) it is less likely to be viewed as violating relational bonds (Tyler, Lind, & Huo, Reference Tyler, Lind and Huo2000). This reasoning is further supported by findings that employees with a low PDO value dignified and respectful treatment from their leaders more than those with a high PDO (Tyler et al., Reference Tyler, Lind and Huo2000). Similarly, research on supervisor–subordinate fit suggests that low PDO individuals may feel more threatened by authoritarian leadership because it is less aligned with their values and expectations (Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman, & Johnson, Reference Kristof-Brown and Billsberry2005). Moreover, individuals who possess similar values tend to share common aspects of cognitive processing and common methods for interpreting events that help them reduce uncertainty, conflict, and other negative aspects of work interaction (Ostroff, Shin, & Kinicki, Reference Ostroff, Shin and Kinicki2005).

PDO should also moderate the mediating effect of OBSE on the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence. The rationale for this also is based on findings in the PE fit literature. For example, Roberts, and Robins, (Reference Roberts and Robins2004) in a longitudinal study found that higher PE fit was related to increases in self-esteem. Similarly, Naus, van Iterson, & Roe (Reference Naus, van Iterson and Roe2007) found that value incongruence between personal and organizational values was related to decreases in OBSE. Their rationale for this finding was that incongruence between personal and organizational values, along with reduced autonomy, could inhibit the employee from acting in a self-expressive and self-consistent manner (Korman, Reference Korman2001). Similarly, value congruence between an employee and their organization may enhance an employee’s perception of fairness. This may lead to the employee feeling valued and respected, which may increase their self-esteem (see Blader & Tyler, Reference Blader and Tyler2005). Considering that employees often see their supervisors and the organization as having similar identities (Eisenberger, et al., Reference Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales and Steiger-Mueller2010), these findings should be applicable to the fit between an employee and their leader.

Based on the above reasoning, and combining with Hypotheses 2 and 3, we contend that PDO moderates the mediating effect of psychological safety/OBSE on the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence behaviour, thus two moderated-mediation relationships are formed. We therefore propose:

Hypothesis 5a : PDO moderates the mediating effect of psychological safety on the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence behaviour. The mediating effect via psychological safety is stronger at low levels of PDO.

Hypothesis 5b : PDO moderates the mediating effect of OBSE on the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence behaviour. The mediating effect via OBSE is stronger at low levels of PDO.

Based upon our hypotheses, we present the following model as our conceptual framework (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Hypothesized model of the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence behaviour.

Methods

Sample and procedures

Participants are from 16 state-owned manufacturing enterprises in the following five cities: Beijing, Rizhao, Weifang, Chongqing, and Xuzhou. The rationale for examining state-owned manufacturing enterprises is that they tend to maintain more traditional management style, and in particular, authoritarian leadership (see Bloom, Genakos, Sadun, & Van Reenen, Reference Bloom, Genakos, Sadun and Van Reenen2012). We distributed 430 questionnaires, of which 390 (90.7%) were completed and returned. After removing incomplete questionnaires, 324 (83.08%) valid questionnaires remained. Participation in the survey was voluntary. Participant characteristics are 221 (68.2%) male, average age is 28.5 years (SD=5.04) with a minimum of 22 and a maximum of 50 years old. The mean tenure with the organization is 4.03 years with a minimum of 1 year and a maximum of 25 years. They are either factory workers or base-line clerks. The education level is mainly college and above (314 participants, 96.9% of valid questionnaires; high school and below is 10 with the rate of 3.1%; junior college is 50 with the rate of 15.4%; bachelor is 161 with the rate of 49.7%; master and above is 103 with the rate of 31.8%).

We conducted consultations with the heads of HR and departments where we explained the research objectives and process. After gaining consent, we then distributed two different questionnaires. The first questionnaire included questions about the antecedent and control variables. This questionnaire was completed and collected at this time. The second questionnaire was in a sealed envelope and participants were told not to complete it for 3 weeks. Based on consultations with our contacts at the various organizations, we decided to distribute both surveys at the same time (instead of 3 weeks apart) to reduce inconvenience to the management and respondents at the respective organizations. This questionnaire included questions about the dependent variable (i.e., employee silence behaviour). We reminded participants when to complete the second questionnaire by text message or email. This data collection procedure was used to reduce common method bias (see Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). Numbers were assigned to each set of questionnaires to enable matching the two questionnaires for each participant. During the distribution process, participants were reminded to carefully read the instructions, and were told that ‘there is no right or wrong answer to the question,’ ‘this questionnaire is only for the purpose of academic research,’ ‘the questionnaire results are analyzed as a whole and not for the study of any particular case or company,’ ‘the questionnaire is anonymous and the data are not revealed to a third party.’

Measures

Authoritarian leadership

We used Zhou and Long’s (Reference Zhou and Long2007) 5-item scale, which has previously been examined in a Chinese context. This scale is based upon Cheng, Chou, and Farh’s (Reference Cheng, Chou and Farh2000) authoritarian leader dimension in the paternalistic management table (PLS) (The model fit of CFA for PLS is CFI = 0.94, IFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.13, RMR = 0.05). Sample items include, ‘In meetings, it is always according to his (her) will to make the final decision,’ and ‘He/she never reveals information to us.’ Likert 5-point scale is used to record the responses from 1=‘never’ to 5=‘always’. The Cronbach’s α is 0.78.

Psychological safety

We used a 5-item personal psychological safety scale developed by Liang, Farh, and Farh (Reference Liang, Farh and Farh2012), which is based on Edmondson’s (Reference Edmondson1999) group psychological safety. Sample items include, ‘I can express my real feelings about work’ and ‘Nobody in my unit will pick on me even if I have different opinions.’ Likert 5-point scale is used to record the responses from 1=‘completely disagree’ to 5=‘completely agree’. The Cronbach’s α is 0.71.

OBSE

We used Liang, Farh, and Farh (Reference Liang, Farh and Farh2012) 7-item measurement, which has been examined in China and is based upon the original scales of Pierce et al. (Reference Pierce, Gardner, Cummings and Dunham1989). Sample items include ‘In my company (work unit), I am important,’ and ‘In my company (work unit), others take me or my work suggestions seriously.’ A Likert 5-point scale was used to record the responses from 1=‘completely disagree’ to 5=‘completely agree’. The Cronbach’s α is 0.80.

PDO

We used six items from Dorfman and Howell’s (Reference Dorfman and Howell1988) scale. Sample items include ‘When making decisions, most managers do not need to consult with subordinates,’ and ‘When dealing with subordinates, managers often use power and authority’. Likert 5-point scale was used to record the responses from 1=‘completely disagree’ to 5=‘completely agree’. The Cronbach’s α is 0.72.

Employee silence behaviour

In response to arguments that silence is distinct from simply an absence of voice (e.g., Van Dyne, Ang, & Botero, Reference Van Dyne, Ang and Botero2003), we used Detert and Edmonsdson’s (Reference Detert and Edmondson2011) employee silence behaviour scale. Sample questions include ‘I keep ideas for developing new products or services to myself,’ and ‘I keep quiet in group meetings about problems with daily routines that hamper performance.’ A Likert 5-point scale was used to record the responses from 1=‘never’ to 5=‘always’. The Cronbach’s α is 0.84.

Controls

We controlled for three demographic variables (gender, educational background, and tenure) that might potentially confound the results. Previous research has shown that women are often more likely than men to withhold opinions and information in work settings (see Molseed, Reference Molseed1989). Therefore, we controlled for gender which we coded 1 for ‘male’ and 0 for ‘female.’ Because employees with longer tenure may feel more comfortable speaking up (Stamper & Van Dyne, Reference Stamper and Van Dyne2001), we also controlled for organizational tenure which we measured by number of years. Because employees with higher education may feel more confident or have more ideas they would like to express (e.g., Frese, Teng, & Wijnen, Reference Frese, Teng and Wijnen1999), we also controlled for education. We coded 1 for ‘high school and below,’ 2 for ‘some college,’ 3 for ‘bachelor,’ and 4 for ‘masters and above.’ We then used dummy coding for this variable, setting ‘high school and below’ as the baseline to examine the effects of other three categories.

We translated the PDO scale and employee silence behaviour scale into Chinese using established cross-cultural translation and back-translation processes (see Brislin, Reference Brislin1986). The remaining scales are originally in Chinese.

Results

Examining common method bias

To examine the influence of common method bias, we randomly divided the data (N=324) into two equal parts. One part (N=162) was used in exploratory factor analysis for Harman’s single-factor test, which indicated Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin=0.79, Bartlett’s test of Sphericity of 1,822.65 (p<.001), five factors were distributed independently, and no common factor could explain the most variance (43.43% for the first factor). Since Harman’s single-factor test is not a robust method to test common method bias (Podsakoff, et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003), AMOS 7.0 was used for confirmatory factor analysis on the remaining data (N=162). This analysis confirmed that the five-dimensional model comprised of the original five variables provided the best degree of fit (CFI=0.93, IFI=0.89, RMSEA=0.07, RMR=0.08, χ2/df=1.82, p<.001). These results suggest that common method bias is not significant in our study.

Correlation and descriptive analysis

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, coefficient α’s, and correlation matrix for all measures. All measures demonstrated suitable reliability (Nunnally & Bernstein, Reference Nunnally and Bernstein1994). The relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence behaviour was significant (r=0.46, p<.001). The relationships between employee silence behaviour, and both psychological safety (r=−0.42, p<.001) and OBSE (r=−0.21, p<.001), were significant. The relationships between authoritarian leadership, and both psychological safety (r=−0.44, p<.001) and OBSE (r=−0.17, p<.01), also were significant.

Table 1 Means, standard deviations, coefficient α’s and correlations among scales

Note. α reliabilities are shown on the diagonal in parentheses.

All control variables were included in this analysis, but were nonsignificant and therefore not shown.

N=324.

***p<.001; **p<.01.

Regression analyses of direct effects

Table 2 presents results of regression analyses to test Hypotheses 1–3. In Models 1, 5, and 7, only the demographic factors are included in the analyses. In Model 2, the regression analysis indicates a positive relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence behaviour (β=0.48, p<.001), therefore Hypothesis 1 is supported. In Models 6 and 8, the regression analysis indicates a negative relationship between authoritarian leadership and psychological safety (β=−0.45, p<.001)/OBSE (β=−0.15, p<.01).

Table 2 Regression and mediation analyses

Note. N=324.

***p<.001; **p<.01.

All control variables were included in this analysis, but only tenure was significant and others not shown.

Next, in Model 3, the regression analyses indicates a negative relationship between psychological safety and employee silence behaviour (β=−0.26, p<.001) when controlling for authoritarian leadership and therefore Hypothesis 2 is supported. In Model 4, the regression analyses indicates a negative relationship between OBSE and employee silence behaviour (β=−0.09, p<.1) when controlling for authoritarian leadership and therefore Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Moderating effect of PDO

Since the actual samples selected may not satisfy the principle of normal distribution, we used a Bootstrap method. By selecting samples again and again, the Bootstrap method is able to estimate the confidence interval (CI) of the indirect effect. We used the procedure developed by Preacher and Hayes (Reference Preacher and Hayes2008). The frequency number of sampling in the Bootstrap method is set as 5,000, and when 0 is excluded from the 95% interval, the effect is shown as significant.

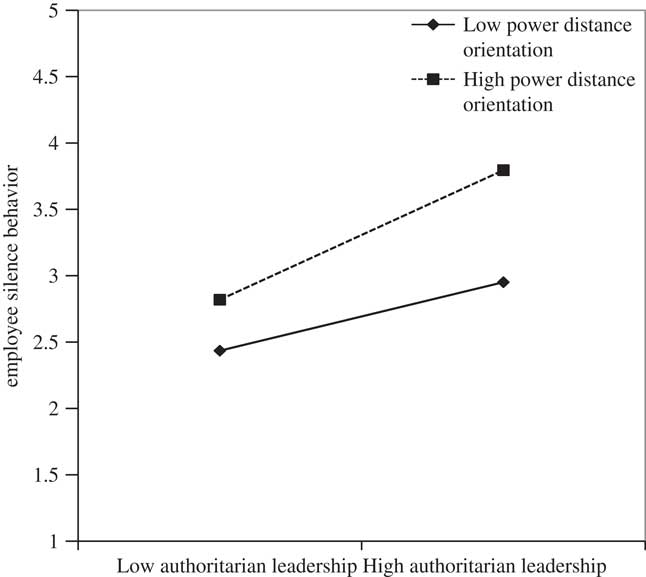

Bootstrap analysis revealed that the interactive effects of authoritarian leadership and PDO on employee silence behaviour (interaction’s B=−0.17, SE=0.07, CI=[0.03, 0.31]) is significant. The results indicate that the direct relationships between authoritarian leadership and employee silence behaviour is different at different levels of PDO (higher than the average, average, lower than average). When PDO is high (conditioned direct effect=0.52, SE=0.08, CI=[0.36, 0.68]), this direct relationship is stronger than when PDO is low (conditioned direct effect=0.27, SE=0.07, CI=[0.14, 0.40]).

To further examine this moderating effect, we adopted Aiken and West’s (Reference Aiken and West1991) simple slope analysis procedure. We separated the moderating variables that are 1 SD higher and lower than the mean into two respective groups. We then conducted regression analysis at the two levels (see Figure 2). The results indicate that, when employees have lower PDO, the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence is weaker (β=0.16, p >.05). In contrast, when employees have higher PDO, this relationship becomes stronger (β=0.53, p<.001). Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is supported.

Figure 2 The relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence behaviour at different levels of power distance orientations (testing Hypothesis 4).

Moderated-mediation model test

Bootstrap analyses reveal that PDO moderates the mediating effect of psychological safety and OBSE between authoritarian leadership and employee silence behaviour (psychological safety: interaction’s B=0.23, SE=0.07, CI=[0.09, 0.36]; OBSE: interaction’s B=0.22, SE=0.07, CI=[0.08, 0.36]). The results indicate that the indirect relationships between authoritarian leadership and employee silence behaviour via psychological safety and OBSE are different at different levels of PDO (lower than the average, average, higher than average). When PDO (psychological safety: conditioned indirect effect=0.07, SE=0.03, CI=[0.03, 0.14]; OBSE: conditioned indirect effect=−0.01, SE=0.01, CI=[−0.04, 0.02]) is high, this indirect relationship via the mediating factors is weaker than when PDO is low (psychological safety: conditioned indirect effect=0.16, SE=0.04, CI=[0.09, 0.24]; OBSE: conditioned indirect effect=0.06, SE=0.02, CI=[0.03, 0.12]). Therefore, Hypotheses 5a and 5b are supported.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence behaviour in Chinese state-owned organizations. Our results indicate that authoritarian leadership is positively related to employee silence behaviour. That is, the stronger an employee’s perception that they report to an authoritarian leader, the more likely they are to engage in employee silence behaviour. In addition, we examined the mediating roles of psychological safety and OBSE, and the moderating influence of PDO on this relationship. We found that both psychological safety and OBSE mediated the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence. In addition, we found that the direct relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence was stronger for employees with a high, as opposed to a low, PDO. Interestingly, we found that the mediating roles of both psychological safety and OBSE were stronger for employees with a low, as opposed to a high, PDO. We next discuss the theoretical and practical implications of our findings.

Theoretical implications

It would be easy to simply assume that authoritarian leadership makes employees more likely to engage in employee silence behaviour. After all, there is a considerable amount of research on employee voice, employee silence, and related constructs (e.g., whistle-blowing, spirals of silence, principled organizational dissent, etc.; for a review, see Brinsfield, Reference Brinsfield2013) that suggests that the behaviours exemplified in authoritarian leadership (e.g., controlling, threatening, domineering) inhibit employees’ willingness to express themselves. Leadership, however, in an inherently contextual phenomenon – and most of what we know about its effects on employee silence is based on research conducted in a Western context. The types of behaviours that exemplify authoritarian leadership are typically viewed pejoratively by employees in Western contexts. Although we are unable to test cross-cultural differences in this study, there are reasons to suspect that this may not be the case in a traditional Chinese context (see Avolio et al., Reference Avolio, Sosik, Jung and Berson2003). Traditional views of leadership in China often expect and endorse this style of leadership. Therefore, authoritarian leadership is a culturally distinct type of leadership, and its effects should not be assumed to parallel those of ostensibly similar leader behaviours in other contexts.

The culturally dependent nature of authoritarian leadership notwithstanding, leadership scholars have long acknowledged that there are ‘universals’ (i.e., consistent across cultures; see Bass, Reference Bass1997) when it comes to the effects of some leader behaviours. Based on our findings, it appears that leader behaviours that emphasize personal dominance, centralization of authority, unilateral decision making, etc. contribute to employee silence even in a context where those behaviours are expected and endorsed. These findings, in and of themselves, are noteworthy considering the potential for context to alter followers’ perception of, and reactions to, leader behaviours. This, however, is not the whole story. To better understand the nature of this effect, we also examined factors that intervene in, and affect the direction and/or strength of, this relationship.

Mediating and moderating factors

As Detert and Edmondson (Reference Detert and Edmondson2011) pointed out, much of the prior research on employee voice and silence has either implicitly or explicitly placed psychological safety as a mediating factor between some independent variable and voice or silence behaviour. Prior research has shown that the types of behaviours exemplified in authoritarian leadership may negatively impact followers’ perception of psychological safety (see Detert & Burris, Reference Detert and Burris2007) and hence, employee willingness to speak up. However, from this prior research it was unclear if authoritarian leadership would have this effect in a context where it is expected and endorsed, and hence may not be viewed as violating relational bonds (Tyler et al., Reference Tyler, Lind and Huo2000). This ambiguity is partly based on research pointing to the double-edged nature of PDO. One the one hand, a high PDO can make followers less likely to challenge a leader and more likely to defer to the leader’s judgement when they disagree with the leader (see Javidan et al., Reference Javidan, Dorfman, de Luque and House2006). On the other hand, a high PDO can mitigate the typically negative effects of uncivil, unfair, and unsupportive leader behaviours (Lee, Pillutla, & Law, Reference Lee, Pillutla and Law2000; Brockner, et al., Reference Brockner, Ackerman, Greenberg, Gelfand, Francesco, Chen and Shapiro2001; Kirkman et al., Reference Kirkman, Chen, Farh, Chen and Lowe2009) because these behaviours are not seen as violating relational bonds (see Tyler et al., Reference Tyler, Lind and Huo2000). These potential ambiguities notwithstanding, our findings do indicate that authoritarian leadership reduces perceptions of psychological safety and subsequently increases employee silence. Considering the nature of authoritarian leadership, we think it would be easy to assume that its effect on employee silence is wholly due to employees’ beliefs that it is unsafe to speak up. However, the mediating effect of psychological safety only explains part of the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence behaviour.

Pioneering scholars acknowledged that fear of consequences associated with speaking up is only one of a variety of possible reasons or motives for employee silence behaviour (e.g., Milliken, Morrison, & Hewlin, Reference Milliken, Morrison and Hewlin2003). Recent empirical research has revealed that the underlying motives for employee silence are even more nuanced and varied than previously acknowledged (Brinsfield, Reference Brinsfield2013). In fact, Brinsfield (Reference Brinsfield2013) found six distinct motives for employee silence (i.e., deviant, relational, defensive, diffident, ineffectual, and disengaged). The defensive silence motive, described as primarily based on fear of extrinsic consequences associated with speaking up, is conceptually related to psychological safety. Two of the other silence motives (i.e., diffident, ineffectual) appear more conceptually related to our other mediating factor (i.e., OBSE).

Prior research has also shown that the types of behaviours exemplified in authoritarian leadership may negatively impact followers’ self-esteem (see Pierce & Gardner, Reference Pierce and Gardner2004). From this prior research it was unclear if authoritarian leadership would have this effect considering that it is expected and endorsed in traditional Chinese contexts. As with psychological safety, this ambiguity is partly based on research pointing to the double-edged nature of PDO as described earlier. However, our findings do indicate that authoritarian leadership reduces perceptions of OBSE and subsequently increases employee silence. Therefore, these findings advance our understanding of the impact that authoritarian leadership has on psychological safety and OBSE, and subsequently on employee silence behaviour. In addition, these findings also augment our understanding of the different underlying motives (i.e., defensive, diffident, ineffectual) that may be influenced by authoritarian leadership and subsequently influence employee silence behaviour – albeit we recognize that these mediating factors and silence motives are not precise equivalents.

Similar to most psycho/behavioural constructs, the effects of authoritarian leadership on employee silence behaviour do not operate uniformly across individuals. Finding that PDO moderates the direct effect of authoritarian leadership on employee silence behaviour suggests that greater concordance between the values and expectations of authoritarian leaders and followers leads to higher levels of silence. Although most of the research on employee silence (and related constructs) suggests that greater levels of silence are undesirable, whether or not this is the case depends on perspective and context. When working for an authoritarian leader, it is likely that greater silence may indeed be beneficial for the follower. This is because authoritarian leaders value and expect deference to their authority and decisions. This also is consistent with the majority of the findings in the PE fit literature that suggests that higher levels of fit are usually beneficial for the individual. From a business unit or organizational perspective, however, higher fit, and subsequently more silence, may lead to negative consequences such as impaired decision making, reduced innovation, and perpetuation of unethical behaviour.

In addition to the above findings, we also found that PDO impacted the strength of the mediating effects of both psychological safety and OBSE. That is, the mediating effects of psychological safety and OBSE were stronger for employees with lower (as opposed to higher) levels of PDO. These findings further point to the double-edged nature of PDO as it relates to authoritarian leadership and employee silence. When looking only at the direct relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence, our findings indicate that a high PDO exacerbates the effects of authoritarian leadership on employee silence. However, our findings reveal a deeper complexity to the role of PDO as a high PDO buffers the effects of authoritarian leadership on factors that contribute to employee silence.

Practical implications

In terms of the practical implications, it would be naive to think that authoritarian leadership is going away any time soon, especially considering it is rooted in centuries of tradition in China. Similarly, it is tempting to think that authoritarian leaders want to keep their employees feeling unsafe or unassured, but considering the tradition associated with authoritarian leadership, we think this belief also is naive. Authoritarian leaders are not necessarily bad people, who are simply power hungry and domineering. Therefore, research that highlights the consequences of authoritarian leadership in China should help these leaders more fully understand the implications of this approach. This is perhaps especially important with an outcome as ambiguous and covert as employee silence – after all, an authoritarian leader who confronts silence from her or his employees could easily think that all is well.

If the goal is to reduce employee silence behaviour (which is not always the case), the moderating and mediating factors examined in this study provide some important insights for managers. On the one hand, managers could select employees with lower PDO, as their personal discord with the tenets authoritarian leadership will make it less likely that they will simply buy in to the notion that they should suppress their ideas and opinions in deference to their leader. For this tactic to be effective, however, steps will need to be taken to overcome the higher tendency of low PDO followers to feel threatened or unassured by an authoritarian leader. One way this could be accomplished is by explicitly surfacing paradigmatic assumptions surrounding authoritarian leadership. This is because when employees understand that authoritarian leadership is more about tradition and culture, and less about a specific leader’s desire for power and dominance, they may be less likely to view this approach as violating relational bonds, and therefore less of a personal threat to their safety and value. In addition, organizations could offer employees more support and encouragement in developing their ideas, and provide coaching, and learning opportunities to make employees feel more valued and safe.

For employees high in PDO, steps could be taken to alter their beliefs of what it means to be a loyal follower to an authoritarian leader, whereas cultural tradition evokes remaining silent in deference to an authoritarian leader, these employees could be instructed that respectful expression of ideas, opinions, and concerns can be accomplished without disrespecting or threatening the leader. For this to work, however, authoritarian leaders will also need to be willing to be more open and receptive to this input. We recognize that this may be easier said than done, but authoritarian leaders need to adapt to a changing world – and we believe this can be accomplished without completely relinquishing a valued and honoured tradition.

Limitations and future research

Although this research has provided novel findings and recommendations, there are methodological limitations and areas for additional research that need to be considered. First, our sample was for state-owned enterprises in the manufacturing sector – private businesses, foreign enterprises, and other sectors were not included. This may limit the generalizability of our findings for these other contexts. Second, all the variables in this research were assessed via self-report measures, although we did utilize two waves of data collection to attenuate common method bias. Third, this research focusses on individual-level silence behaviour, power distance, and psychological safety, it does not consider the group, organizational, or cultural levels of these phenomena, which may be particularly important in China considering the high power distance nature of this culture. Fourth, it is impossible for us to discern to what extent employee silence behaviour is affect-driven, and to what extent it is judgement driven – especially considering that our mediating factors have both affective and cognitive components that are not clearly delineated in the measures we used. And fifth, our data did not enable us to discern the effects of some followers being nested with the same leader – hence future multilevel modelling to untangle these effects is needed.

Considering the above limitations, future studies may consider expanding the scope by examining different types of enterprises that may not be as rooted in traditional Chinese culture and values (e.g., technology sector). Considering the important role that psychological safety plays in employee silence, more work is needed which examines how different facets of psychological safety (e.g., participative psychological safety; West, Reference West1990) are influenced by authoritarian leadership, and subsequently influence employee silence behaviour. Research that examines the reciprocal nature of the relationship between employee silence and authoritarian leadership, psychological safety, and self-esteem may also be informative. For instance, prior research has shown that feeling unable to speak up may lead to psychological and physiological harm (e.g., Cortina & Magley, Reference Cortina and Magley2003). We also believe that research on employee silence at different levels of analysis should be undertaken. Based on the extant research it is not clear to what extent employee silence can manifest at group, organizational, or even cultural levels of analysis. Let alone what antecedent and outcomes may be associated with employee silence at these different levels of analysis. Research that more precisely tests some of our theoretical assertions is also needed. For instance, experimental designs that specifically test the effects of PDO on the relational bonds between authoritarian leaders and followers could help verify the psychological processes involved. Finally, research that examines the specific events that are associated with authoritarian leadership, and the discrete emotions and judgements these events elicit, and how these contribute to employee silence motives and behaviour, will help us better understand the nature of these relationships.

Conclusion

Based on this study, we conclude that authoritarian leadership has a positive direct effect on employee silence behaviour, and this relationship is moderated by followers’ PDO. That is, the strength of this direct effect is stronger for followers with a high (as opposed to low) PDO. In addition, we found that the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence is partly mediated by both psychological safety and OBSE. Moreover, the strength of these mediating effects are stronger for followers with a low (as opposed to high) PDO. This research not only advances our understanding of the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee silence, but also enhances our understanding of the psychological processes involved.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the National Science Foundation of China for the support (no. 71372180).