Introduction

In recent times there has been an increase of studies focussing on destructive leadership, such as abusive supervision and workplace bullying (Bowling & Beehr, Reference Bowling and Beehr2006; Mitchell & Ambrose, Reference Mitchell and Ambrose2007; Liu, Liao, & Loi, Reference Liu, Liao and Loi2012; Schyns & Schilling, Reference Schyns and Schilling2012). Similarly, there has been widespread coverage within New Zealand’s popular media regarding the psychological and economic cost of destructive leadership (Barton, Reference Barton2005; Tapaleao, Reference Tapaleao2010; Hueber, Reference Hueber2012; Gillies, Reference Gillies2013). This is concerning for organisations, as abusive supervision is a major predictor of employee turnover, which is highly costly (Waldman, Kelly, Arora, & Smith, Reference Waldman, Kelly, Arora and Smith2004). Not only does employee turnover result in an immediate loss of productivity, but the costs associated with hiring and training new staff can cost organisations greatly – as much as 5.8% of their annual operating budget (Waldman et al., Reference Waldman, Kelly, Arora and Smith2004). For this reason, it is important to understand what motivates employees to leave an organisation.

The present study focusses on abusive supervision, which relates to the extent to which supervisors engage in hostile verbal and nonverbal abuse towards employees (Tepper, Reference Tepper2000). Examples of this include being undermined and yelled at, or told you are ‘useless’ or a ‘waste of time’. The consequences of abusive supervision have been well examined, and include such deleterious effects as counter-productivity, increased turnover (Detert, Trevino, Burris, & Andiappan, Reference Detert, Trevino, Burris and Andiappan2007; Tepper, Reference Tepper2007; Shoss, Eisenberger, Restubog, & Zagenczyk, Reference Shoss, Eisenberger, Restubog and Zagenczyk2013), decreased job performance and team creativity (Harris, Kacmar, & Zivnuska, Reference Harris, Kacmar and Zivnuska2007; Liu, Liao, & Loi, Reference Liu, Liao and Loi2012).

The present study explores measures that may mitigate the effects of abusive supervision. It must be noted that tolerating abusive supervision is a violation of human rights, and the heart of the issue lies with the identification and elimination of abusive supervisors. However, given how difficult it can be to identify such negative behaviour (Rayner, Hoel, & Cooper, Reference Rayner, Hoel and Cooper2002; Harvey, Stoner, Hochwarter, & Kacmar, Reference Harvey, Stoner, Hochwarter and Kacmar2007), other avenues must be explored. For example, research by Harvey et al. (Reference Harvey, Stoner, Hochwarter and Kacmar2007) focussed on how positive affect (an individual’s sense of well-being and positive emotions) could be successfully used by individuals to lessen the impact of their abusive supervisors. Killoren (Reference Killoren2014) suggested that many victims of abuse find it hard to tell whether they are being abused, or whether the negative experience is normal. The abuser can be very subtle when they attack; for example, they can utter negative statements under their breath, or discuss something only the receiver takes offence at with the intention of harming them. Finally, many who are abused in this way are too ashamed to admit this is happening to them, which will often mean the abuse gets progressively worse, as the abuser gains more confidence and power (Killoren, Reference Killoren2014). It is therefore highly unlikely that workplaces can fully eliminate abusive supervision (Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Stoner, Hochwarter and Kacmar2007).

If an employee feels cared for by the organisation, they are more likely to feel valued and view the organisation more favourably (Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison, & Sowa, Reference Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison and Sowa1986). This support may diminish the negative effects of the individual abusive supervisor, although it has been suggested that further analysis is required (Hershcovis et al., Reference Hershcovis, Turner, Barling, Arnold, Dupré, Inness and Sivanathan2007). As such, the purpose of this study is to investigate the role of perceived organisational support (POS) in mediating the influence of abusive supervision on turnover intentions. The present study makes a number of contributions: (1) it explores the effect of abusive supervision on three under-studied populations: blue-collar workers, Māori employees, and Chinese employees within New Zealand; (2) it finds that the relationship between abusive supervision and turnover intentions is best understood as being partially mediated by POS, and that this holds across all three samples; and (3) it provides direction for organisations by understanding that the detrimental influence of abusive individuals may be mitigated through greater organisational support.

Abusive Supervision

Established by Tepper (Reference Tepper2000), abusive supervision can be defined as ‘subordinates’ perceptions of the extent to which supervisors engage in the sustained display of hostile verbal and non-verbal behaviours, excluding physical contact’ (p. 178). While Tepper (Reference Tepper2000) excludes physical abuse, it must be noted that physical abuse in the workplace does occur. For example, in some cases workers have been subject to ‘working in toxic and oftentimes sexually and physically abusive conditions, for poverty wages’ (Boje, Reference Boje1998: np). As such, physical abuse cannot always be excluded, as in Tepper’s definition of abusive supervision. Abusive supervision can also include a manager being rude, coercive, withholding essential information, taking credit for a subordinate’s success, and publicly criticising subordinates (Keashly, Reference Keashly1998; Zellars, Tepper, & Duffy, Reference Zellars, Tepper and Duffy2002; Tepper, Reference Tepper2007). Tepper (Reference Tepper2007) suggested that abusive supervision comprises four important characteristics: (1) it must not be of a physical nature; (2) the manager’s behaviour has to be deliberate; (3) it is based on a subordinate’s perceptions; and (4) it must contain sustained displays of hostility. As such, the manager having a one-off angry outburst would not, in and of itself, comprise abusive supervision (Tepper, Reference Tepper2007). Thus, abusive supervision can often be observed through non-physical acts such as threats, using derogatory names, engaging in repeated angry outbursts, humiliation, intimidation, or ridiculing a subordinate in front of others (Keashly, Reference Keashly1998; Zellars, Tepper, & Duffy, Reference Zellars, Tepper and Duffy2002; Tepper, Reference Tepper2007). Because of this, subordinates who are abused report feeling frustrated, alienated, and powerless (Tepper, Reference Tepper2000, Reference Tepper2007).

Definitions of abusive supervision stem from justice theories and the nature of reciprocity. The term justice is synonymous with morally right, honest, equitable, ethical, and fair behaviour (Waite & Hawker, Reference Waite and Hawker2009). So, abused subordinates who are undermined or humiliated at work are likely to regard such abuse as being ‘unfair’. Indeed, Tepper (Reference Tepper2000) found that abusive supervision was negatively related to all forms of organisational justice. Social exchange theory can also aid our understanding of a subordinate’s responses to abusive supervision (Tepper, Reference Tepper2000). Built on the norm of reciprocity, social exchange theory involves ‘give and take’ exchanges, and is a ‘two-sided, mutually contingent, and mutually rewarding process involving “transactions”, or simply “exchange”’ (Emerson, Reference Emerson1976: 336). According to justice theories such as equity theory, people generally believe that the outcomes of a social exchange should be fair and just for both parties, with outcomes proportional to inputs (Vaughn & Hogg, Reference Vaughan and Hogg2005). Therefore, good behaviour is likely to be responded to with good behaviour, and bad reciprocated with bad behaviour (Vaughn & Hogg, Reference Vaughan and Hogg2005; Walumbwa, Cropanzano, & Hartnell, Reference Walumbwa, Cropanzano and Hartnell2009).

Over time, an individual is likely to assess any disparity between their inputs and outputs, and their actions will reflect this. The larger the disparity between subordinate effort and supervisor response, the more the subordinate is likely to feel the relationship is unfair or inequitable, and the more they will feel distressed (Vaughn & Hogg, Reference Vaughan and Hogg2005). This notion was tested by Tepper (Reference Tepper2000), who found that subordinates’ perception of unfairness or injustice explained their responses to abusive supervision. Abusive supervision signals a negative social exchange, which is likely to result in feelings of injustice and distress (Tepper, Reference Tepper2000). Consequently, it is understandable that perceived injustices resulting from abusive supervision would translate into deleterious outcomes, including increased intent to leave (Tepper, Reference Tepper2000; Tepper, Duffy, Hoobler, & Ensley, Reference Tepper, Duffy, Hoobler and Ensley2004).

Subordinates who do not feel that their manager cares about them are unlikely to feel obliged to remain with the organisation, resulting in higher turnover intentions (Tepper, Reference Tepper2007). Recent meta-analysis shows the links between abusive supervision and turnover intentions. For example, Schyns and Schilling (2013) found a modest strength of relationship (r=0.22). This meta-analysis highlighted the lack of studies on the effect of abusive supervision on turnover when compared with other outcomes. The present study adds an interesting dynamic to existing research by testing these relationships on different employment sectors, ethnicities, and countries outside North America. Added to this, we focus on additional ways to indirectly reduce the negative consequences of abusive supervision through increased organisational support. The more organisations can contribute to the direct and indirect reduction of abusive supervision, the better. Aligned with the meta-analysis, we expect that the unjust treatment of subordinates will increase their desire to leave an organisation, leading to our first hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1: Abusive supervision will be positively related to turnover intentions.

POS

The importance of POS has emerged due to the observation that if an organisation shows concern towards their employees, then employees are likely to show commitment and focus in return (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison and Sowa1986; Eisenberger, Armeli, Rexwinkel, & Lynch, Reference Eisenberger, Armeli, Rexwinkel and Lynch2001). Rhoades and Eisenberger (Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002) defined POS as the ‘general belief that [an employee’s] work organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being’ (p. 698). Similarly to abusive supervision, POS is based upon employees’ subjective observations of actions by their organisation. Therefore, the sincerity, frequency, and extremity of statements made by the organisation are likely to influence employees’ appraisal of an organisation’s support. Stemming from organisational support theory, POS is examined through the lens of social exchange theory (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison and Sowa1986; Eisenberger, Fasolo, & Davis-LaMastro, Reference Eisenberger, Fasolo and Davis-LaMastro1990). Social exchange theory suggests that employees may provide hard work in exchange for tangible rewards and socio-emotional resources (Rhoades & Eisenberger, Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002; Haar, Reference Haar2006).

According to organisational support theory, employees believe an organisation has a general orientation towards them, including concern for their welfare, and recognition of their contributions, which they judge by the amount of favourable treatment they receive (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison and Sowa1986; Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski, & Rhoades, Reference Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski and Rhoades2002; Rhoades & Eisenberger, Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002). This suggests that employees assess the extent to which their employer cares about them, which may consequently affect their level of effort (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison and Sowa1986). Furthermore, Eisenberger et al. (Reference Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison and Sowa1986) suggested that POS ‘strengthens employees’ effort-outcome expectancy and affective attachment to the organization, resulting in greater efforts to fulfil the organization’s goals’ (p. 501). Therefore, high POS would raise an employee’s expectancy that the organisation would remunerate greater effort exerted towards meeting organisational goals.

Relating to abuse in the workplace, Hodson, Roscigno, and Lopez (Reference Hodson, Roscigno and Lopez2006) stated that ‘[b]ureaucratic, well-organised work sites … procedurally constrain managers from adopting abusive behaviors’ (p. 390), thus providing links between organisational factors and abusive behaviours by supervisors. With regard to abusive supervision, it seems logical that being undermined or yelled at would result in feeling unsupported. Eisenberger, Lynch, Aselage and Rohdieck (Reference Eisenberger, Lynch, Aselage and Rohdieck2004) investigated the negative reciprocity norm and revenge. They suggested that ‘belief in people’s general malevolence and cruelty encourages support of the negative norm of reciprocity as a strategy to prevent exploitation’ (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Lynch, Aselage and Rohdieck2004: 795). Furthermore, Eisenberger et al. (Reference Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski and Rhoades2002) suggested that a subordinate may view their supervisor as an agent acting on behalf of the whole organisation, and hence that POS may also reflect a subordinate’s view of their supervisor. More recently, this was highlighted by Shoss et al. (Reference Shoss, Eisenberger, Restubog and Zagenczyk2013), who found that ‘that abusive supervision was associated with lessened POS, which was related to employees’ counterproductive work behaviors and in-role and extrarole performance’ (p. 166). In many cases, an organisation that prides itself on high levels of support would not knowingly allow abusive supervision to take place. However, given the difficulty in identifying abusive supervision (Rayner, Hoel, & Cooper, Reference Rayner, Hoel and Cooper2002; Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Stoner, Hochwarter and Kacmar2007), it is still possible for such abuse to take place. Unfortunately, and consequently, we suggest that subordinates may regard abuse from a supervisor as an action from the whole organisation, thereby reducing their perception that the organisation is supportive.

Hypothesis 2: Abusive supervision will be negatively related to POS.

To an employee, high POS signifies that they are cared about and valued by the organisation. Therefore, according to social exchange theory, the employee is likely to develop feelings of ‘obligation’ and respond with positive work outcomes such as greater commitment (Haar & Spell, Reference Haar and Spell2004). In meta-analyses, POS had a small but statistically reliable negative relationship with turnover intentions (Rhoades & Eisenberger, Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002), while Riggle, Edmondson, and Hansen (Reference Riggle, Edmondson and Hansen2009) found a strong and negative relationship. This last meta-analysis comprised 167 studies over 20 years of POS research, and found POS explained 25% of the variance for turnover intentions. Eisenberger et al. (Reference Eisenberger, Fasolo and Davis-LaMastro1990) stated that POS would ‘promote the incorporation of organizational membership and role status into employees’ self-identity’ (p. 57). This is likely to create a sense of affiliation and loyalty to the organisation, thereby raising employees’ performance as they internalise and recognise organisation goals and values as their own. This makes POS a vital factor in achieving organisational outcomes. Given the established links between POS and turnover intentions, we also test the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3: POS will be negatively related to turnover intentions.

Mediating effects of POS

As stated earlier, there is a need for studies of abusive supervision to explore ways in which organisations can deal with these issues of abuse. We therefore test the potential mediating effects of POS. Related to social exchange theory is the concept of macromotives, which Konvosky and Pugh (Reference Konvosky and Pugh1994) defined as a set ‘of attributions that characterize people’s feelings and beliefs about their exchange partners’ (p. 658). The nature and strength of social exchanges and the associated obligations may therefore be dependent upon the quality of an existing employee-organisation relationship (Lambert, Reference Lambert2000). For example, if the underlying relationship is negative, an employee may be unlikely to reciprocate the organisation positively in return for some benefit. Therefore, macromotives may be critical in setting the tone of an employee–organisation relationship.

Understanding the relationship between an employee’s perceptions of organisational support and job attitudes (i.e., turnover intentions) may be of particular benefit to an organisation, such that they can determine where best to spend their resources, in order to encourage a positive social exchange. For example, if abusive supervision results in higher turnover intentions irrespective of the support provided by an organisation, then enhancing factors to increase POS may be wasted. However, if POS leads to a reduction in the strength of the relationship between abusive supervision and turnover intentions, then focussing on POS is warranted. Furthermore, POS has been suggested as being an ideal construct for examining the underlying effect of these macromotives (Konvosky & Pugh, Reference Konvosky and Pugh1994; Lambert, Reference Lambert2000).

Testing the mediating effects of POS is warranted due to its established nature as a predictor of turnover intentions (Rhoades & Eisenberger, Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002; Riggle, Edmondson, & Hansen, Reference Riggle, Edmondson and Hansen2009). Moreover, POS has been shown to play a mediating role with many job outcomes (Moorman, Blakely, & Niehoff, Reference Moorman, Blakely and Niehoff1998; Masterson, Lewis, Goldman, & Taylor, Reference Masterson, Lewis, Goldman and Taylor2000; Rhoades, Eisenberger, & Armeli, Reference Rhoades, Eisenberger and Armeli2001; Allen, Shore, & Griffeth, Reference Allen, Shore and Griffeth2003). For example, multiple studies have found that POS mediated the relationship between organisational justice and turnover intentions (Masterson et al., Reference Masterson, Lewis, Goldman and Taylor2000; Loi, Hang-yue, & Foley, Reference Loi, Hang-yue and Foley2006). These results highlight the importance of a social-exchange approach, and suggest the importance of justice perceptions, upon which abusive supervision is based, in testing the relationship between abusive supervision and turnover intentions. A study by Eisenberger et al. (Reference Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski and Rhoades2002) focussed on the relationship between POS, perceived supervisor support and turnover. They stated that ‘supervisors, to the extent that they are identified with the organization, contribute to perceived organizational support, and, ultimately, to job retention’ (p. 572). However, a later study by Maertz, Griffeth, Campbell, and Allen (Reference Maertz, Griffeth, Campbell and Allen2007) appears to contradict some of these findings. They suggested that perceived supervisor support had independent effects on turnover that POS did not mediate. Despite these inconsistent findings, the studies that focused on POS, supervisors and turnover offer theoretical backing for the relationships tested within this study. The present study aims to add some clarification to this relationship by widening the participants surveyed to a diverse range of employees (i.e., ethnically diverse and blue-collar workers).

Since abusive supervision is associated with injustice and negative social exchanges, we suggest that abusive supervision will lead to an increased desire to leave the organisation. However, we suggest under macromotives theory that POS will intervene in this relationship, reducing its strength. Testing POS also allows us to explore the argument of Hershcovis et al. (Reference Hershcovis, Turner, Barling, Arnold, Dupré, Inness and Sivanathan2007), who suggested that organisational-level constructs could diminish the effects of supervisors. This leads to our last hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4: POS will mediate the relationship between abusive supervision and turnover intentions.

Method

Schyns and Schilling (2013) noted the need for more abusive supervision studies to focus on different employee types and ethnicities. Also, Nuzzo (Reference Nuzzo2014) argues that empirical studies and statistical tests require greater replication to provide greater confidence. In response, we undertook data collection from three distinct groups to test our hypothesised relationships focussing on profession and ethnicity: (1) blue-collar workers, (2) Māori employees (the indigenous people of New Zealand), and (3) Chinese employees. We suggest these provide unique groups that will aid in generalising the findings beyond homogenous samples (e.g., North American employees).

Sample and procedure

Study one examined blue-collar workers who worked in a large metropolitan city of New Zealand. Participants were recruited from a construction company, and were involved in a range of industries, including primary products, construction, skilled labour, and other related work. All workers in the sample were blue-collar employees who typically worked outdoors. Jobs commonly included manual labour (e.g., heavy lifting) and skilled labour (e.g., forklift driving). From 180 workers, 100 responses were received (56% response rate). On average, participants were 41 years old, male (89%), and represented a wide range of ethnicities.

Study two specifically targeted Māori employees and purposive sampling was undertaken, as Māori make up only 13% of the New Zealand workplace. Fifty organisations participated in the study, and from a total pool of 400 Māori employees, 218 responses were received (54.5% response rate). Respondents ranged across a variety of industries, with an average age of 39.1 years old and the majority being female (65%).

Study three specifically targeted Chinese employees within New Zealand. Snowball sampling was undertaken to elicit responses from this minority group. From 500 distributed surveys, 114 responses were received (22.8% response rate). Participants from study three were around 25 years old (SD=6.1 years) and almost evenly split by gender (50.9% male).

Combined studies

We initially tested relationships for the three studies separately and this analysis showed comparable findings. Furthermore, each sample had measures that were highly robust individually and this did not change when combined. We therefore combined the three studies for analysis to make presenting the findings easier, although we also provide the individual studies for more in-depth information.

Measures

The present study does not directly measure justice theory and social exchange theory. We do however operationalise these theories through abusive supervision (justice theory) and POS (social exchange theory). All studies used identical scales and items in the survey. All items were coded on a 5-point scale ranging from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree. Abusive supervision was measured using six items from Tepper (Reference Tepper2000). Questions were asked with the stem ‘My supervisor…’ and included ‘tells me my thoughts or feelings are stupid’ and ‘ridicules me’. Although Tepper’s original measure included 15-items, various other studies of abusive supervision have employed shorter items. For example, studies have used five items (Mitchell & Ambrose, Reference Mitchell and Ambrose2007) and even three items (Detert et al., Reference Detert, Trevino, Burris and Andiappan2007). Mitchell and Ambrose (Reference Mitchell and Ambrose2007) built their five items by re-analysing the original data and determining two distinct factors, and like them, we focus on the active-aggressive abusive supervision dimension. We included a sixth item ‘reminds me of my past mistakes and failures’ and confirmed the new six-item measure with factor analysis (principal components, varimax rotation) and all six items loaded on a single factor (eigenvalues=4.915, accounting for 81.9% of the variance). Overall, the six-item measure had excellent reliability (α=0.96). POS was measured using five items by Eisenberger et al. (Reference Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison and Sowa1986). Following the stem ‘My organisation…’, samples items included ‘considers my goals and values’, and ‘values my contributions to its well-being’ (α=0.90). Turnover intentions were measured using four items by Kelloway, Gottlieb, and Barham (Reference Kelloway, Gottlieb and Barham1999). A sample questions is ‘I am thinking about leaving my organisation’ (α=0.95).

Measurement models

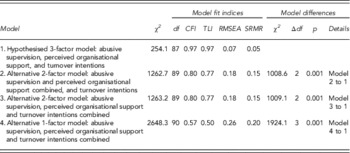

To confirm the separate dimensions of measures, items were tested by structural equation modelling (SEM) using AMOS. Williams, Vandenberg, and Edwards (Reference Williams, Vandenberg and Edwards2009) suggested the following goodness-of-fit thresholds as the most useful for analysis: the comparative fit index (CFI≥0.95), the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA≤0.08), and the standardised root mean residual (SRMR≤0.10). In addition, we added the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI≥0.95), as recommended by Beauducel and Herzberg (Reference Beauducel and Herzberg2006). The hypothesised measurement model and alternative models are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Results of confirmatory factor analysis for study measures

Overall, the hypothesised measurement model fit the data best (Hoyle, Reference Hoyle1995). To confirm this, the CFA was reanalysed following Hair, Black, Babin, and Anderson’s (Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010) instructions on testing comparison models. This showed that the alternative models were all significantly worse than the hypothesised model.

Analysis

Hypotheses were tested using SEM in AMOS to assess the direct and mediational effects of the study variables. We followed the Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation as described by Bauer, Preacher, and Gil (Reference Bauer, Preacher and Gil2006). We calculated the distribution of the mediation effect using the estimate and the standard error of the effect of the predictor (abusive supervision) on the mediator (POS), as well as the estimate and the standard error of POS on turnover intentions. The null hypothesis that POS does not significantly mediate the relationship between abusive supervision and turnover intentions is rejected when the distribution of possible estimates for m lies above or below zero. Bootstrapping has become an acceptable way to test mediation effects in studies using SEM (e.g., Roche, Haar, & Luthans, Reference Roche, Haar and Luthans2014).

Results

Descriptive statistics for the study variables are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Correlations and descriptive statistics of study variables

*p<.05, **p<.01.

Table 2 has correlations for each individual data set plus the combined data set that we will specifically report on. It shows abusive supervision is significantly correlated to POS (r=−0.48, p<.01) and turnover intentions (r=0.38, p<.01), while POS is also significantly correlated to turnover intentions (r=−0.46, p<.01). From the mean scores (all with midpoints of 3.0), we can see that abusive supervision is well below the midpoint (M=1.84), while POS is only slightly above (M=3.35), and turnover intentions are just below (M=2.89).

We conducted ANOVA to test for differences between the three samples. Analysis showed there were no significant differences towards turnover intentions between the three samples, but there were towards abusive supervision and POS. Ad hoc analysis using Tukey HSD showed that sample three (Chinese employees) reported significantly higher abusive supervision (M=2.4) compared with sample 1 (blue-collar workers, M=2.0) and sample 2 (Māori, M=1.8). Furthermore, sample 1 reported significantly lower POS (M=2.8) than samples 2 and 3 (both M=3.6).

Regarding testing the relationships, three alternative structural models were tested to determine the optimal model based on the data: (1) a partial mediation model, where abusive supervision predicted turnover intentions and POS, and where POS also predicted turnover intentions; (2) a direct-effects-only model, where abusive supervision predicted turnover intentions and POS only; and (3) a full mediation model, where abusive supervision predicted POS only, and in turn, POS predicted turnover intentions only.

The three structural models and comparisons between them are shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Model comparisons for structural models

We tested comparison models (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010) and found that model one (partial mediation model) is superior to the other models. The final structural model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Final mediation model

Structural models

Aligned with the recommendations of Grace and Bollen (Reference Grace and Bollen2005), unstandardised regression coefficients are presented. Figure 1 (combined sample) shows that abusive supervision is significantly linked with turnover intentions (path coefficient=0.29, p<.001) and POS (path coefficient=−0.31, p<.001). Furthermore, POS is also significantly linked with turnover intentions (path coefficient=−0.70, p<.001). Overall, these findings support Hypotheses 1, 2 and 3. To confirm the mediation effects of POS on the direct effects of abusive supervision on turnover intentions (Hypothesis 4) we calculated Monte Carlo tests (at 20,000 repetitions). This provided support for this mediation effect (Bauer, Preacher, & Gil, Reference Bauer, Preacher and Gil2006): LL=0.133, UL=0.3191 (p<.05), supporting Hypothesis 4. Overall, the structural model provides strong support for predicting POS (r 2=0.22) and turnover intentions (r 2=0.27).

As shown in Table 2, the study variables are all significantly correlated to each other at similar levels in the individual samples and in the combined sample (all p<.01 in individual and combined samples). To further confirm these effects, we find the mediation effects (Bauer, Preacher, & Gil, Reference Bauer, Preacher and Gil2006) for each sample (with Monte Carlo tests at 20,000 repetitions), which confirm that the mediation effects are supported in each individual sample as well: sample 1=LL=0.2517, UL=0.8235 (p<.05), sample 2=LL=0.1911, UL=0.5562 (p<.05), and sample 3=LL=0.0064, UL=0.2155 (p<.05).

Discussion

Exploration of abusive supervision has indicated that it is a prevalent problem, which has been linked to damaging effects for both employees and employers (Tepper, Reference Tepper2000, Reference Tepper2007). However, thus far research has largely focussed on the effects of abusive supervision, leaving methods of mitigating the phenomenon relatively unexamined. Reducing the stress and anxiety associated with abusive supervision could be of significant benefit to an organisation, especially as organisations strive to encourage efficiency within their workforce. For example, finding ways to improve employee retention may be vital for organisational success. Therefore, not only did this study aim to examine the effect of abusive supervision on an employee’s turnover intentions, but also the potentially mediating role of POS. It must be noted that tolerating abuse is unacceptable. However, given that abuse is very hard to detect (Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Stoner, Hochwarter and Kacmar2007), we suggest that other forms of support could diminish these negative effects.

Overall, the results of this study support our proposition that, while abusive supervision would increase turnover intentions, this relationship would be somewhat mitigated (mediated) by POS. However, abusive supervision was also found to reduce POS and to increase turnover intentions even while POS reduced them. This shows that abusive supervision can play a significant role in employees’ turnover intentions. Given the wide range of outcomes also influenced by POS (Rhoades & Eisenberger, Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002; Riggle, Edmondson, & Hansen, Reference Riggle, Edmondson and Hansen2009), it seems that, while a highly supportive organisation may play a part in reducing abusive supervision’s influence on turnover intentions, it does not fully mediate this relationship. These findings suggest that a subordinate may view their supervisor as representative of the whole organisation (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski and Rhoades2002), as abuse from a supervisor not only signals their supervisor does not care, but may also suggest that the organisation does not care about them either.

The present study also follows recommendations from Tepper (Reference Tepper2007), who discussed the need to focus on national cultural differences towards abusive supervision. Similar calls were made by Snell, Wong, Chak, and Hui (Reference Snell, Wong, Chak and Hui2013) who stated that ‘cross-cultural research could establish whether large power distance and other cultural and institutional factors render Asian employees especially vulnerable’ (p. 252) to factors leading to abusive supervision. Given that international cultural differences are equally important (Cohen, 2007), we have provided insight into abusive supervision in this context. We also respond to the call from Wei and Si (Reference Wei and Si2013) for greater studies of Chinese employees, to broaden our understanding of abusive supervision.

These results are congruent with the literature that has shown direct relationships between abusive supervision and increased intention to quit (Keashly, Trott, & MacLean, Reference Keashly, Trott and MacLean1994; Tepper, Reference Tepper2000). Furthermore, testing POS as a potential mediator, and finding support for its effects, bears out the notion of macromotives. Hence, we find that underlying feelings of support (i.e., POS) can play a role in overriding the potential detrimental influence of abusive supervision on turnover intentions. Given that full mediation effects were not found, this study shows that macromotives may only reduce rather than completely eliminate the effects of abusive supervision. This provides greater clarity to the work of Hershcovis et al. (Reference Hershcovis, Turner, Barling, Arnold, Dupré, Inness and Sivanathan2007) and suggests that the overarching role of the organisation may not be sufficient to override the more immediate influence of the supervisor. This is important given that these effects held across all three samples. As such, while the macromotives approach was supported, it is evident that the prevailing support of the organisation may not be sufficient to override employees’ perceptions of being abused by their supervisor.

The results of this study highlight the importance of organisational justice and social exchange perspectives. Abusive supervision has been shown to be a pertinent issue (Tepper, Reference Tepper2007), and, as such, research has shifted its focus towards the causes of abusive supervision, in order to mitigate the frequency with which it occurs. Thus far, antecedents of abusive supervision which have been studied include supervisor’s perception of justice (Hoobler & Brass, Reference Hoobler and Brass2006; Tepper et al., 2006), supervisor disposition (Hoobler & Brass, Reference Hoobler and Brass2006), and subordinate disposition (Tepper et al., 2006). For this reason, it seems that abusive supervision is part of a complex web of interactions, and that pinpointing one trigger for abusive supervision may be impossible. Furthermore, as these are constructs over which an organisation may have little control, it suggests that an organisation may need to look to other strategies to reduce abuse. This highlights the importance of the results at hand, which suggest that POS can partially reduce the relationship between abuse and turnover intentions. This result also supports Dawley, Andrews, and Bucklew (Reference Dawley, Andrews and Bucklew2008), who found that POS was the most powerful predictor of organisational outcomes. While the present study emphasises the importance of eliminating abusive supervision, it also highlights the need for organisations to increase support in order to mitigate the effects of abusive supervision that is not visible. Higher levels of organisational support, regardless of the presence of abusive supervisors, will benefit all employees’ workplace and well-being outcomes. It must also be noted that organisations have control over who they hire and promote to supervisory positions. It is important to use a rigorous HR process when selecting potential supervisors in order to reduce the risk of promoting abusive employees. Employees who display abusive traits towards co-workers need to be identified in order to stop this behaviour, and also limit their future role as supervisors unless corrective action occurs.

The present study also makes an important contribution by enhancing the generalisability of abusive supervision studies. All three samples here are under-studied and, given that the effects here show support for established relationships between abusive supervision and POS towards turnover intentions, both these literatures’ generalisabilities are enhanced. In addition, our approach of testing POS as a mediator appears well supported and, again, builds on the literature through testing very distinct samples. Finally, while abusive supervision scores were similar to the prevailing literatures, it is worth highlighting that the ANOVA analysis showed that sample three (Chinese employees) reported significantly higher abusive supervision and lower POS scores than the other two samples. Perhaps these scores reflect a lack of understanding of the New Zealand workplace, or detrimental treatment of these employees. Chinese immigrants are an important and growing population within the New Zealand workplace (Brougham, Reference Brougham2011), and, as such, additional research into the reasons for this should be investigated.

Practical implications

Organisations could benefit by examining the level of POS experienced by subordinates, and invest in resources that would enable them to increase employees’ support perceptions. Studies regarding POS have found that antecedents include development of supportive organisational policies, practices, workplace norms; distribution of discretionary resources and assistance; and favourable job conditions (Eisenberger, Cummings, Armeli, & Lynch, Reference Eisenberger, Cummings, Armeli and Lynch1997), among others. Therefore, an organisation may wish to consider implementing policies that would enhance POS, including providing development opportunities, promotions, flexible work schedules, and work-family practices (Haar & Spell, Reference Haar and Spell2004). Organisations may also want to consider providing training for managers to be more supportive. The effectiveness of training was illustrated in a quasi-experiment by Gonzalez-Morales, Kernan, Becker, and Eisenberger (Reference Gonzalez-Morales, Kernan, Becker and Eisenberger2012), wherein they found that training supervisors to be more supportive had a positive effect on POS (as cited in Shoss et al., Reference Shoss, Eisenberger, Restubog and Zagenczyk2013). This highlights the point that supervisors are fundamental in the support process. A recent meta-analysis by Kossek, Pichler, Bodner, and Hammer (Reference Kossek, Pichler, Bodner and Hammer2011) showed the importance of the supervisor in creating broader support perceptions (including POS). Furthermore, manager training around the costs of abusive supervision may also be beneficial.

From an HR perspective, it seems that turnover may just be one of the detrimental costs of abusive supervision. Organisations that strive to optimise their HR in order to set themselves apart from their competitors will find the retention of staff to be crucial for success, particularly to improve the collective knowledge of their employees (Park, Gardner, & Wright, Reference Park, Gardner and Wright2004). Indeed, Park, Gardner, and Wright (Reference Park, Gardner and Wright2004) stated that ‘firms with stronger, more complex HR capabilities devolved into the broader organisation will adapt, thrive, and achieve competitive advantage relative to competitors’ (p. 271). A more proactive approach might see HR conducting continual evaluations (e.g., 360o feedback), as this may provide clearer evidence of abusive supervision, and provide HR with more timely information, in order to conduct an intervention to stop such abuse. Educating managers on company beliefs, policies, and procedures, as well as making them accountable for their decisions and actions, could also be of benefit (Park, Gardner, & Wright, Reference Park, Gardner and Wright2004). Given the destructive nature of abusive supervision and costs associated with turnover (including hiring and training new staff, and loss of productivity), HR managers should pay greater attention to this phenomenon in the workplace.

Limitations

The present study does have some limitations, especially the use of self-reports in all three studies. Abusive supervision is likely to be a delicate issue with employees, and while confidentiality was ensured, participants may have altered their responses, especially if they feared their responses to the surveys would be ‘found out’ by their supervisors. Another limitation is the potential for common-method variance (CMV; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). While Spector (Reference Spector2006) noted that the effects of CMV may actually be very small, Kenny (Reference Kenny2008) notes the use of SEM mitigates this issue. For example, Haar, Russo, Sune, and Ollier-Malaterre (Reference Haar, Russo, Sune and Ollier-Malaterre2014) used SEM to confirm the distinct nature of their measures, which aligns with the Harman’s One-Factor test where a single construct does not emerge (Podsakoff & Organ, Reference Podsakoff and Organ1986), thus providing limited evidence of CMV. Similarly, Judd and Kenny (Reference Judd and Kenny1981) asserted that SEM would be advantageous when conducting mediation models, while Williams, Vandenberg, and Edwards (Reference Williams, Vandenberg and Edwards2009) argued that SEM allows for greater confidence relating to causality and potential mediation effects. Hence, the use of SEM strengthens confidence in this study’s findings. Furthermore, given that the three studies separately replicated the overall effects presented here, this produces strong confidence that these effects are accurate. The dual sample and advanced statistical analysis provide strong support for the results presented.

Importantly, Tepper (Reference Tepper2007) suggested research needed to be carried out in other countries, as most research in this domain to date has been conducted in the United States (Shoss et al., Reference Shoss, Eisenberger, Restubog and Zagenczyk2013). Therefore, this research further contributes to the research domain by adding a New Zealand context and by providing three diverse employee samples, thus improving the generalisation of findings. Furthermore, this is the first time research has addressed the effect of abusive supervision on indigenous people (Māori) and on specific cultural groups working outside their home country (China), further enhancing the contributions of the paper. Finally, we used a newer six-item measure building on the five-item measure by Mitchell and Ambrose (Reference Mitchell and Ambrose2007) and we re-analysed the data with their five items and found no difference in findings, supporting our six-item construct.

Conclusion

This study presents the first look at abusive supervision in a New Zealand context, with samples of Māori, Chinese, and blue-collar employees. Support was found for the theory that abusive supervision has a negative effect on turnover intentions, suggesting that abusive supervision signals an inequitable social exchange with subordinates, which ultimately encourages them to seek employment elsewhere. Moreover, this research added to the research domain by examining the mediating role of POS, and confirmed that POS may potentially mediate the relationship between abusive supervision and turnover intentions. Consequently, support gained from the whole organisation may enable employees to feel cared about and increase their general sense of well-being, and thus help eliminate the harmful effects associated with abusive supervisors. This finding, further highlighting the vital role POS can play, should encourage organisations to improve POS in order to help mitigate the effects of abusive supervision in the workplace.

Acknowledgement

This project was funded with a Marsden Grant, contract number X957.