1. Introduction

The aim of this paper is to provide a new, unified, syntactically-driven analysis to the compositionality of indefiniteness, specificity and anti-specificity in Romance, with a special reference to Brazilian Portuguese (BP), Catalan (C), French (F), Italian (I) and Spanish (S). Our central research question is: what does the syntactic distribution and meaning of indefinite expressions in Romance reveal about their syntactic structure?

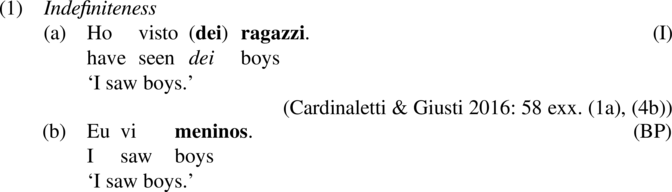

More specifically, we look at data such as those exemplified in (1)–(3) from I and BP.

We take these languages and these indefinite expressions as representative of the phenomena that we want to explore in this paper.

First, we investigate how indefiniteness is derived and expressed: either by means of des/de in F, dei/di in I or by means of bare plurals indefinites and bare mass nouns, both in argument position and in left-dislocated structures, in BP, C and S (Dobrovie-Sorin & Laca Reference Dobrovie-Sorin and Laca1996, Reference Dobrovie-Sorin, Laca, Godard and Abeillé2003; Gutiérrez-Rexach Reference Gutiérrez-Rexach2010; Leonetti Reference Leonetti1999; de Swart Reference de Swart2006; Dobrovie-Sorin & Beyssade Reference Dobrovie-Sorin and Beyssade2012; Laca Reference Laca, Kabatek and Wall2013; Cardinaletti & Giusti Reference Cardinaletti and Giusti2016, Reference Cardinaletti, Giusti, Everaert and van Riemsdijk2017; and others).

Second, we investigate how a specific indefinite reading is derived and expressed, due either to the presence of a quantifier expression (e.g. uns in BP) that introduces the reference to a quantized DP (Krifka Reference Krifka, Bartsch, Von Benthem and Van Emde Boas1989, Reference Krifka, Sag and Szabolcsi1992) or to the identification of the referent via a semantic function (e.g. a choice function, Reinhart Reference Reinhart1997, Winter Reference Winter1997; or a Skolem function, Steedman Reference Steedman2003, Reference Steedman2006) that guarantees a specific referential interpretation for des/dei phrases (Dobrovie-Sorin & Beyssade Reference Dobrovie-Sorin and Beyssade2012, Cardinaletti & Giusti Reference Cardinaletti and Giusti2016).

Third, we investigate how an anti-specific reading is derived and expressed (e.g. the existential quantifiers alcun(i) (I)/algun((o)s) (BP, C, S)/quelqu(es) (F); see Eguren & Sánchez Reference Eguren and Sánchez2007; Martí Reference Martí2008a, Reference Martíb, Reference Martí, Giannakidou and Rathert2009; Alonso-Ovalle & Menéndez-Benito Reference Alonso-Ovalle and Menéndez-Benito2010; Giannakidou & Quer Reference Giannakidou and Quer2013; Jayez & Tovena Reference Jayez, Tovena, Ebert and Hinterwimmer2013; Etxeberria & Giannakidou Reference Etxeberria and Giannakidou2017; and others). This reading has also been associated with semantic evidentiality (Jayez & Tovena Reference Jayez, Tovena, Ebert and Hinterwimmer2013), in the sense that the epistemic agent does not know (Alonso-Ovalle & Menéndez-Benito Reference Alonso-Ovalle, Menéndez-Benito, Aloni, Franke and Roelofsen2013) and has no direct evidence of which entity or entities satisfy the description provided by the sentences, or (s)he does not want to make explicit to the interlocutor the fact that (s)he has this knowledge.

Our specific goal is to address the following two fundamental questions: (i) What is the syntactic structure of the various indefinite expressions in (1)–(3), despite their superficial forms observed in the Romance languages here considered? and (ii) How can the different readings in (1)–(3) be derived in grammar at the syntax–semantics interface? We understand that this syntactic-semantic approach has the advantage of allowing us to reveal how syntactic structure can determine the meaning of different forms of indefiniteness.

To address these questions we are going to propose an analysis that explains the availability of the aforementioned indefinite in Romance as follows: (i) indefiniteness is derived by adjoining an abstract operator de to a definite D(eterminer), with the result that it shifts a definite reading to an indefinite one, and turns an entity into a property-type expression; (ii) quantificational indefiniteness is derived by merging a quantifier that is lexically encoded for specificity (e.g. specific quantifiers such as certains in F, cierto in S, and non-specific quantifiers such as plusieurs in F, varios in S) with an indefinite D, with the result that it turns a property into a generalized quantifier;Footnote 3 and (iii) anti-specificity is derived by adjoining an abstract operator alg to a quantifier with an interpretable specificity feature, with the result that a modified generalized quantifier is obtained: alg shifts its meaning by eliminating the reference value of the individuals quantified over and by considering an alternative set whose value is not available to the speaker in the world being described.Footnote 4 We also aim to show (iv) that the role of the operator de with respect to definiteness is parallel to the role of alg with respect to specificity, the difference being that the former applies to definite DPs and shifts their definiteness to indefiniteness, while the latter applies to specific QPs and shifts their specificity to anti-specificity.Footnote 5

As will be seen, our analysis postulates a syntactically-driven indefiniteness hierarchy that accounts for the compositionality of the various meanings presented in (1)–(3). The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the background assumptions on which we build the analysis just exposed.

Section 3 provides a new account of indefiniteness that builds on definite plural count nouns, analyzed by means of a morphosyntactic pluralizer feature adjoined to D (Cyrino & Espinal Reference Cyrino and Espinal2020), and on definite mass nouns, over which an operator de cancels definiteness (Hypothesis 1). This operator is spelled-out as de in some Romance languages and in some constructions, among which we refer to left-dislocated structures. With this approach we account for the data in (1). In this section we also address the question of why singular indefinites behave differently in Romance (Dobrovie-Sorin, Bleam & Espinal Reference Dobrovie-Sorin, Bleam and Espinal2006, Espinal Reference Espinal2010, Espinal & McNally Reference Espinal and McNally2011).Footnote 6

Section 4 presents a new syntactic analysis of quantificational indefiniteness and specificity according to which a quantifier (Q) lexically encoded as being either specific or non-specific is merged with an indefinite D in complement position (Hypothesis 2). We support this hypothesis in combination with both plural count nouns and mass nouns. We resort to scopal specificity (as expected from QPs), referential specificity and epistemic specificity to account for the data in (2), as well as for other specific readings of F des and I dei phrases in preverbal position.Footnote 7

Section 5 shows how anti-specificity is syntactically built up by means of an operator alg that adjoins to a Q encoding specificity and gives as output another Q deprived of specificity (Hypothesis 3). This operator is spelled-out in most Romance languages as alc-/alg-, but in F it is instantiated as quelqu-, thus accounting for the data in (3). We show that, being syntactically adjoined to Q, alg may have scope interactions with other quantifiers and, in spite of being semantically anti-specific, it may occur in syntactic topic position (Etxeberria & Giannakidou Reference Etxeberria and Giannakidou2017).

We conclude the paper with Section 6.

2. Background assumptions

The linguistic literature, especially the semantically-oriented part of it, has been very active in terms of the various readings outlined in Section 1. Still, to our knowledge, a common analysis that accounts for how these different meanings appear and are built syntactically has not yet been provided. Our paper aims to fill this gap by contributing in a novel way to the structure of indefinite expressions at the syntax–semantics interface. In order to do that, we first present some assumptions.

First, we assume that a nominal expression in Romance needs a DP structure (Abney Reference Abney1987) in order to be a syntactic and a semantic argument (Longobardi Reference Longobardi1994, Chierchia Reference Chierchia1998, Dobrovie-Sorin et al. Reference Dobrovie-Sorin, Bleam and Espinal2006, Ghomeshi, Paul & Wiltschko Reference Ghomeshi, Paul and Wiltschko2009, Dobrovie-Sorin & Beyssade Reference Dobrovie-Sorin and Beyssade2012, and others). This assumption follows from an attempt to explain the restricted distribution of bare arguments in Romance, in particular bare count singular nominals in object position and all sorts of bare nominals in subject position. An overt D has been postulated to correlate with an iota function (Partee Reference Partee, Groenendijk, de Jong and Stokhof1987) that turns property-type expressions (the denotation of bare common nouns) into entity-type expressions (the denotation of DPs). We also assume a multilayered DP structure (Zamparelli Reference Zamparelli1995/2000, Ihsane Reference Ihsane2008, Martí-Girbau Reference Martí-Girbau2010), but ours builds over the D head and the Q head, as will become explicit in Sections 3–5.

Second, bearing in mind Heim’s (Reference Heim, Portner, von Heusinger and Maienborn2011) assumption for languages without articles, according to which nominal expressions are simply indefinites, we assume that in languages with articles DPs in argument position are definite (i.e. there are no indefinite articles), and definiteness is shifted to indefiniteness by a dedicated grammatical process (an abstract operator that in some languages and in certain constructions takes the lexical exponent de at the time of lexical insertion).Footnote 8

Third, note that examples (1)–(3) contain plural expressions. We assume, following Cyrino & Espinal (Reference Cyrino and Espinal2020), that within the nominal domain, the pluralizer in Romance is syntactically adjoined to D (alternatively, a categorized d root), as in (4), and it is syntactically opaque; hence, the newly formed object has the same label as its host (D). As noted above, we are also assuming that the lowest D is definite, and it selects a nominal expression, represented in (4) by n.

According to this proposal, Number in Romance does not project a morphosyntactic functional head.Footnote 9 Furthermore, on the basis of puzzling data on plural marking in a variety of Romance languages (i.e. lack of plural agreement and partial plural marking; plural marking on pronouns, clitics and possessives; plural marking on relatives; etc.), Cyrino & Espinal (Reference Cyrino and Espinal2020) hypothesize that the pluralizer in unmarked cases is a modifying feature on D, and instantiations of plural marking within the nominal domain should be conceived as the output of morphophonological concord, a post-syntactic operation. As will become clear in Section 3 this syntactic structure – based on head modification – is the one on which our analysis of indefinite expressions in Romance is built.

Fourth, we assume a distinction between indefinite quantitative vs. partitive de (preposition) (Milner Reference Milner1978; Storto Reference Storto, Quer, Schroten, Scorretti, Sleeman and Verheugd2003; Ihsane Reference Ihsane2008; Martí-Girbau Reference Martí-Girbau2010; Cardinaletti & Giusti Reference Cardinaletti and Giusti2016, Reference Cardinaletti, Giusti, Everaert and van Riemsdijk2017; and others). We acknowledge that etymologically both uses of de derive from the Latin preposition de, which has a spatial meaning (i.e. it denotes a distancing from a source or origin). Additionally, we acknowledge that from the partitive construction the so-called partitive article (a contraction of the preposition de plus a definite article or preposizione articolata, Chierchia Reference Chierchia1997) was reinterpreted as the expression of indefiniteness in various Romance languages (e.g. Middle French, Carlier Reference Carlier2007, Carlier & Lamiroy Reference Carlier, Lamiroy, Luraghi and Huumo2014) following a grammaticalization chain (Heine Reference Heine1992).Footnote 10

Fifth, we share with Martí (Reference Martí2008b) the insight that an indefiniteness hierarchy and a decompositional analysis of the existential import of S unos and algunos are to be postulated in the nominal domain. However, our proposal differs from hers in that it focuses not on the lexical semantics of these indefinite quantifiers but on the syntactic hierarchical instantiation of functional elements conveying (in)definiteness, specificity and anti-specificity. We show in Table 1 a summary of only those aspects that we consider important for the reader interested in the topic of indefiniteness from both a semantic and a syntactic perspective, and that differentiate Martí’s approach from ours.

Table 1 Martí’s (Reference Martí2008b, Reference Martí, Giannakidou and Rathert2009) analysis vs. the present analysis.

In sum, in our study we argue that different indefinite readings are constrained by different functional categories, and in this syntactically-driven hierarchy we postulate a parallel between the derivation of anti-specific alg-phrases from Qs that encode specificity and the derivation of indefinite de-phrases from definite Ds. The latter is addressed in the following section.

3. Indefiniteness

Romance languages have different ways of expressing indefiniteness. F requires an overt indefinite marker de preceding definite plural count nouns and definite mass nouns.Footnote 11 The situation in I appears to show greater variation, as will become clear below. Still, the definite article in the two languages introduces a definite interpretation by means of which it denotes a function that takes a property and yields the unique object that has that property, whereas de – preceding what looks like a definite plural count noun or a definite mass noun – entails an existential reading, also entailed by bare nouns.Footnote 12 Consider the F and I definite vs. indefinite minimal pairs illustrated in (5)–(8), which show that de preceding a definite article conveys indefiniteness.

Other languages, such as BP, C and S, most commonly resort to bare plurals and bare mass nouns to refer to indefinite nominals in object position. See the S examples in (9), in which the expressions in bold denote a non-specific set of individuals (in the case of the bare plural) or a non-specific amount of matter (in the case of the bare mass noun).Footnote 14

However, note that even in those languages that usually express indefiniteness by means of bare plurals (e.g. BP, C, S), an overt marker de may show up following those quantifiers and nouns that select indefinite complements. Thus, collective and measure nouns also select for indefinite plural complements preceded by an overt marker de. Footnote 15

The indefinite marker de also shows up in fronted indefinite expressions, as illustrated in the clitic left-dislocation examples in (11) for C. Note that this indefinite expression is associated with the object of either a quantifier, a cardinal or a transitive verb.

Concerning indefinite mass nouns and indefinite plural count nouns, it is also of interest to highlight the microvariation to be found in Italo-Romance varieties (Cardinaletti & Giusti Reference Cardinaletti, Giusti, d’Alessandro and Pescarini2018): bare di + null article (12a), null di + null article (12b), null di + definite article (12c) and di + definite article (12d), which are all interpreted as conveying indefiniteness.

All the preceding data support the hypothesis that de in the Romance languages under study is a marker of indefiniteness. Furthermore, it shows that de may or may not be overtly realized. To account for this variation in the expression of indefiniteness (a marker de – either overt or covert – in combination with a definite article – either overt or covert – followed by a plural count noun or a mass noun) we propose our first hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1 In Romance the indefinite interpretation associated with nominal expressions is composed by merging an abstract operator de to a definite D.

In the case of indefinite bare plurals the operator de adjoins to a pluralized D, as represented in the structure in (13a).Footnote 16 In the case of indefinite mass nouns we assume the structure in (13b).

Structure (13a) must be read as follows. The definite D (i.e. a definite article) is modified twice: first it is pluralized, by being merged with [ipluralizer:pl] (see Section 2), and second it is deprived of definiteness by being merged with de. Structure (13b) shows that the definite D can also be modified only once, when number does not play a role. These syntactic structures account for the various indefinite nominal expressions discussed in this section, with the proviso that at the time of Allomorph Selection (i.e. Vocabulary Insertion) some Romance languages in some structures have available an overt de that is phonologically sensitive to the vocabulary item for the (pluralized) definite article it combines with, while others opt for zero insertion (Nevins Reference Nevins and Trommer2012). By means of this analysis we provide a new, unified derivation of indefinite expressions, no matter whether they take the form of de phrases, bare plurals or bare mass nouns.

At the level of logical form, de – parallel to ident (Partee Reference Partee, Groenendijk, de Jong and Stokhof1987) – shifts an entity ⟨e⟩ into a property ⟨e,t⟩, and is of type ⟨e ⟨e,t⟩⟩. According to this synchronic analysis of indefiniteness in Romance, de is neither a partitive preposition nor a partitive article but rather an operator that cancels the iota operator associated with the definite article (de: ι(x)[P(x)] ⟶ P(x)). This analysis predicts that under the effects of this type-shifting operation introduced by de, a definite nominal expression is shifted into an indefinite expression with a property-type denotation. Henceforth, we will refer to indefinite expressions as ‘de-phrases’.

Two predictions follow from our analysis of de as an operator of type ⟨e ⟨e,t⟩⟩. On the one hand, since de-phrases denote properties they should only be able to have an anaphoric relationship with property-type denoting clitics. On the other hand, since de-phrases denote properties they should only be able to license a narrow scope reading. Both predictions are borne out.

In constructions that contain indefinite complements and dislocated indefinite expressions, a dedicated indefinite clitic (ne/en) is needed for anaphoric reference in those languages that have another series of clitics for reference to definite plural accusative nominals (Kayne Reference Kayne1975 for F, Cordin Reference Cordin and Renzi1988 for I, and Todolí 2002 for C).Footnote 17

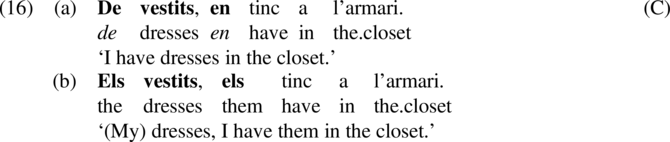

See, in particular, the minimal pair in (16), which contrasts an indefinite with a definite dislocated constituent.

It is important to emphasize that the clitic ne/en does not convey a partitive meaning in any of the above examples, it simply resumes a de-phrase.Footnote 18 Indefinite plural count nouns and mass nouns being property-type expressions (as follows from the structures in (13) above), the only possible clitic that is allowed in this context is a property-type anaphora (Espinal & McNally Reference Espinal and McNally2011, Laca Reference Laca, Kabatek and Wall2013).Footnote 19 By contrast, definite DPs show an anaphoric relationship with entity-type pronouns such as the accusative els ‘them’, illustrated in (16b).

Let us now move on to our second prediction. As commonly claimed in the literature (Dobrovie-Sorin & Laca Reference Dobrovie-Sorin and Laca1996, Reference Dobrovie-Sorin, Laca, Godard and Abeillé2003; Cardinaletti & Giusti Reference Cardinaletti and Giusti2016), those Romance languages that allow bare plurals only license a narrow scope interpretation of the bare plural under negation, even if they are topicalized (Laca Reference Laca, Kabatek and Wall2013), as illustrated in (17b), the reason being that property-type expressions are weak and therefore do not allow wide/strong readings. Our analysis in (13) provides a syntactic explanation for this weakness.

In F, where the presence of de does not alternate with a bare plural, the unmarked interpretation is also narrow scope (18a) (Delfitto Reference Delfitto, Hulk, Malka and Schroten1993, Cardinaletti & Giusti Reference Cardinaletti and Giusti2016), exactly like S bare plurals in (17a, b). In I, where bare plurals alternate with dei phrases in object position, different forms convey differences in meaning: the bare plural only licenses a narrow scope interpretation under negation (17c), whereas the dei phrase is ambiguous between a wide and a narrow scope reading (18b) (Chierchia Reference Chierchia1997: 91 ex. (35c), Zamparelli Reference Zamparelli2008, Cardinaletti & Giusti Reference Cardinaletti and Giusti2016, Giusti Reference Giusti2021).Footnote 20

Recall that the operator de applies to plurals and mass nouns, and cannot repair the wide/strong indefinite reading, for which un((o)s)/um(s) is available in Romance. This raises the question of why we observe differences in scope among the Romance languages under study here. We hypothesize that the existing differences derive not from different formal properties of the operator de (to which we uniformly assign the syntactic structure in (13)) and the semantic type ⟨e ⟨e,t⟩⟩, but from the co-existence of alternating forms in the languages analyzed. In BP, C and S bare plurals have narrow scope under negation because un((o)s)/um(s) indefinites have additional formal features and take a default wide scope.Footnote 22 In F de phrases take a narrow scope reading with respect to negation, and it alternates with un, which takes a wide scope reading; des phrases cannot take narrow scope with respect to sentential negation in Standard F because they are specified differently from de phrases, even though they can be interpreted in the scope of negation in some F dialects (Stark & Gerards Reference Stark and Gerards2021).Footnote 23 In I, bare plurals take narrow scope under negation, while singular un and dei phrases have a default wide scope, without excluding a narrow scope, as also occurs in some I dialects (Cardinaletti & Giusti Reference Cardinaletti, Giusti, d’Alessandro and Pescarini2018).

We therefore predict that, in spite of the fact that de is overtly instantiated in (18) but not in (17), a de operator is responsible for the indefinite, weak reading of both bare plurals and de/des/dei indefinites.

To sum up, in this section we have argued that indefiniteness in Romance is syntactically encoded by means of a de operator adjoined to a definite (pluralized) D. Semantically, this operator cancels the effects of the iota operator introduced by the definite article, turning an entity into a property, with the predictions that pronominalization by en and narrow scope readings are expected. This operator may be instantiated overtly as de in all the Romance languages we have considered.

4. Quantificational indefiniteness and specificity

In this section we have two goals. First, we aim to show that weak quantifiers select for indefinite de-phrases at syntax, no matter whether de is overt at Spell-Out or not. Second, we show that indefinite expressions may convey either scopal specificity (as expected from quantificational expressions), referential specificity (as expected when the referent of an indefinite is functionally dependent on some discourse participant or on another expression in the sentence), or epistemic specificity (as expected when the referent of the indefinite expression is dependent on the speaker’s knowledge). In other words, we propose a novel analysis whereby the specificity seen on indefinite expressions can be derived from a syntactic structure in which weak quantifiers select for indefinite de-phrases, no matter whether de is overt or not; these quantifiers turn properties into generalized quantifiers.

In (10a), repeated here as (19a), we have illustrated the possibility that an overt de introduces the indefinite complement of a quantifier and this happens in languages (e.g. BP, C, S) that usually express indefiniteness by means of bare plurals, thus following the same pattern found in F (19b).

If we consider C, we find that only weak quantifiers (those allowed in existential sentences, Milsark Reference Milsark1974) select for indefinite de-phrases, although some of them require an overt de preceding the indefinite complement, others have an optional de, and still others lack an overt de, as illustrated in (20).Footnote 24

Incidentally, Kayne (Reference Kayne1975: 120) already postulates a structure that contains a covert marker de for the structures in (21), and Gerards & Stark (Reference Gerards and Stark2021: 11) mention the existence of overt de phrases after numerals in colloquial varieties of F, as in (22), an example originally from Bauche (Reference Bauche1951).

To account for these data, we postulate that weak quantifiers and cardinals select for indefinite de-phrases, as postulated in our second hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2 The quantificational reading of indefinite expressions is obtained by a quantifier that selects for a de-phrase.

Accordingly, we postulate that the de-phrase is merged in the complement position of a quantifier, as represented in (23). Structure (23a) represents quantified indefinite plural count nouns, whereas structure (23b) represents quantified indefinite mass nouns.

Two caveats are in order here. First, recall that in the Romance paradigm there are two sets of languages: those that have a quantifier un (for singular and plural) and those that lack this vocabulary item (for the plural). For both groups of languages, we postulate the same structure. The Q head in (23a) hosts different quantifiers, some of which encode specificity (F certains; S ciertos) or non-specificity (F plusieurs, beaucoup; S varios, muchos, cardinals), while still others (BP, C and S uno((o)s)) can generally be interpreted either as specific or as non-specific (Enç Reference Enç1991: 4).Footnote 25

Second, the Q head hosts quantifiers that can also be modified by a pluralizer, in such a way that their singular and plural number marking is guaranteed. Recall from Section 3 that de-phrases are plural in default cases. Therefore, we postulated in structure (13a) of that section that the modifying feature of the definite determiner was [ipluralizer:pl]. We now postulate that Q may also be modified by an interpretable pluralizer feature, which is valued for singular or plural: [ipluralizer:{sg,pl}]. In this kind of structure, the two pluralizer features must match in value, otherwise the derivation would crash, as illustrated in (24) for Catalan.

Hence, the de-phrase in this case must be unvalued for this modifying feature, as represented in (25): [ipluralizer: ].Footnote 26

Semantically, in (23a, b) and (25) the Q turns the property-denoting de-phrase into a generalized quantifier, and therefore it is of type ⟨⟨e,t⟩,⟨⟨e,t⟩t⟩⟩. This function is what accounts for the fact that while indefinite de-phrases have narrow scope (see Section 3), those indefinite expressions that are existentially quantified admit wide and narrow scope.

Two predictions follow from this analysis of quantificational indefinites that should be contrasted with the predictions that follow from our analysis of indefiniteness in the previous section. On the one hand, it is expected that both wide and narrow scope readings are available, in combination with other quantifiers and operators. On the other hand, since quantifier expressions denote sets of sets it is expected that they might introduce a discourse relationship with entity-type anaphors. Both predictions are borne out.

Specific quantifiers (e.g. BP certo(s), S cierto(s), F certain(s) ‘some, certain’) entail the existence of a specific set of individuals x (as illustrated in the standard analysis: λP.λQ.∃x[P(x)∧Q(x)]). Consider the examples in (26), which show a specific quantifier in subject position that entails wide scope with respect to the negative operator.Footnote 27

By contrast, indefinite expressions introduced by BP, C and S un(o)s in object position, in sharp contrast with indefinite bare plurals (17), are generally interpreted as specific or as non-specific and license both a wide and a narrow scope interpretation with respect to negation.Footnote 28

Since scope ambiguity is a characteristic of quantifier expressions (but not of pure indefinites), our proposal, namely that the indefinite expressions headed by un(o)s have a quantificational status, rather than having an article status, as commonly claimed in traditional grammars, has the advantage of accommodating these facts more naturally.

The second prediction relates to referential anchoring in discourse. When quantified and cardinal indefinites are left-dislocated, accusative definite clitics – but not the clitic en/ne – must be used in those languages that have the two series of pronouns (e.g. C, F and I), as illustrated in (28). The reason behind this difference is that, whereas de-phrases denote properties, quantifier expressions refer to sets of sets. The definite pronoun usually requires a strong antecedent with which it is coreferential. However, when the antecedent is a quantitative expression, it is considered a weak antecedent of the pronoun (Enç Reference Enç1991), as such a quantitative expression is referentially anchored to a salient discourse participant or another discourse referent (von Heusinger Reference von Heusinger, von Heusinger, Maienborn and Portner2011), and it is resumed by an entity-type anaphora.

In Section 3, we saw that our proposal predicted the use of a dedicated clitic en to refer to left dislocated indefinites (see (14), (15) and (16a) above). Given that in (28) we find quantified indefinites, we do not expect the same clitic. Therefore, by postulating a syntactic and a semantic difference between de-phrases and quantificational indefinites, our proposal also explains the choice of the clitics en/les for different types of indefinite expressions.

Next, we consider what happens in the case of Romance languages such as F and I that do not have an overt quantifier un(o)s for the plural. If des/dei phrases are the overt spell-out of indefiniteness, as argued in Section 3, can these expressions convey a specific reading?

First, consider the facts in F. Even though a de phrase in object position is associated with a weak reading and may only have narrow scope (see ex. (18a) above), des indefinites have also been argued to be associated with a strong – albeit marginal – reading when they occur in sentence-initial position and combine with stage-level predicates (29a), appear in contrastive contexts (29b), are interpreted like certains (29c) and lie outside the scope of negation (29d). The examples in (29a, b, c) are extracted from Dobrovie-Sorin & Beyssade (Reference Dobrovie-Sorin and Beyssade2012: 72 exx. (97), and footnote 3 on page147), whereas (29d) comes from Carlier (Reference Carlier2020: slide 21 ex. (26)).Footnote 29

Note that in the last example the definite pronoun ils has a discourse relationship with the antecedent des Juifs, which has wide scope with respect to negation. Postverbal indefinite des phrases in direct object position can be also associated with a specific reference in specificity-inducing contexts, such as the restrictive relative clause (see also Ihsane Reference Ihsane2008, Carlier Reference Carlier2020).

This example suggests that the specific denotation of des voisins may be due to a covert existential quantifier (note that this expression would be translated with a quantifier unos following the so-called differential object marking a in S: En el restaurante saludé a unos vecinos que también conoces: Paul y Eric; Leonetti Reference Leonetti2004).Footnote 30 Alternatively, the specific referential reading can be the result of applying a Skolemized choice function (i.e. a function that takes a set denoted by the descriptive content of the noun as its argument and yields an element or some specific elements from that set), thus relating the specific referential reading with the speaker’s referential intent (von Heusinger Reference von Heusinger2002, Reference von Heusinger, Comorovski and von Heusinger2007, Reference von Heusinger, von Heusinger, Maienborn and Portner2011). A specific referential reading of the indefinite des phrase also predicts the possibility of an anaphoric relationship with an accusative pronoun. (See the contrast between (31) and (14a) in the previous section.)

In I, dei-phrases allow both wide and narrow scope in postverbal position, exactly like what was observed for BP, C and S un(o)s in (27).

As mentioned for F des phrases, dei phrases in sentence-initial position are accepted with restrictions by native speakers. Thus, (33b) – with a non-specific reading – is preferred over (33a). However, dei phrases are assigned a specific reading when they occur in combination with causative verbs (34).

Two analyses can account for the strong wide reading of indefinite dei phrases. On the one hand, one might postulate that the Q in the structures in (23) can be null.Footnote 31 Note, however, that the coordination test in (35) (Chierchia Reference Chierchia1997: 92 exx. (38b–d)) shows that an overt Q cannot be coordinated with a null Q. Dei, unlike uno and molti, cannot be considered itself a Q, even if it is associated with a small quantity meaning (Cardinaletti & Giusti Reference Cardinaletti, Giusti, d’Alessandro and Pescarini2018, Giusti Reference Giusti2021).

On the other hand, one might postulate that the referential specificity of a dei indefinite is the output of a choice function that takes a set denoted by the descriptive content of the noun and assigns a specific element or some specific elements out of that set. Being either quantificational or Skolem terms, in (36a) an anaphoric relationship is obtained between the two instantiations of the pronoun loro, the null pronoun in subject position of hanno detto, and the weak antecedent dei marziani. Similarly, in (36b) the indefinite expression dei biscotti is referentially anchored to a salient discourse referent or to some particular individuals that the speaker has in mind, thus allowing the definite pronoun li within the sentence.

To sum up, in this section we have shown that weak quantifiers select for indefinite de-phrases in Romance, no matter whether de is overt at Spell-Out or not. Second, we have shown that weak indefinite expressions (des/dei phrases) may convey either scopal specificity (as expected from their being quantificational indefinites), referential specificity and epistemic specificity (as derived from their being Skolem terms), which correlate with wide scope and resumption by means of entity-type clitics. Note that the possibility that des/dei phrases in F and I, but not bare plurals, can be associated with referential specificity derives from the fact that in these languages there is not a dedicated form un(o)s to encode quantificational specificity, unlike the set of vocabulary items of other Romance languages such as S, C and BP. We assume that this contrast is related to the different diachronic paths these languages took (see footnote 28).

5. Anti-specificity

In the previous section we have shown how our analysis of quantificational specificity builds on the syntactic analysis of indefiniteness discussed in Section 3. In this section we focus on the derivation of quantificational anti-specificity.

Anti-specific indefinite quantifiers denote sets of sets, but the speaker presents himself/herself either as ignorant about which individuals are members of that set of sets, or as assuming that their identification is not relevant to the addressee at the time of the conversation. In either case the exact denotation of the indefinite expression is unavailable in context.

An anti-specific reading is normally associated with the examples presented in (3) for I and BP, here repeated as (37), and in (38) for F. These examples illustrate overt anti-specific quantifiers (see footnote 2, though).

The indefinite nominal expressions in bold in (37) and (38) have been characterized in the literature as showing either lack of epistemic specificity (Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath1997, Farkas Reference Farkas2000), anti-specificity (Jayez & Tovena Reference Jayez, Tovena, Ebert and Hinterwimmer2013) or referential vagueness (Aloni Reference Aloni2011, Giannakidou & Quer Reference Giannakidou and Quer2013). We align with Jayez and Tovena and claim that these quantifiers are anti-specific indefinite quantifiers, used to refer to an undetermined individual satisfying the descriptive content of the noun, thus reflecting the speaker’s ignorance (Farkas Reference Farkas2020) regarding which individual satisfies the description provided by the sentence.Footnote 33

In F and I the contrast between specificity and anti-specificity, reflecting speaker’s knowledge vs. speaker’s ignorance, can be covertly expressed, as illustrated in the minimal pair in (39) for F.

Note that (39a) would be translated as unos in S, whereas (39b) would be translated as algunos. Footnote 34 In the former example the specific interpretation of the des phrase is due to the entailment that a set of individuals exists that is known by the speaker and that makes the reference of this expression quantized (Krifka Reference Krifka, Bartsch, Von Benthem and Van Emde Boas1989, Reference Krifka, Sag and Szabolcsi1992; Ihsane Reference Ihsane2021a). By contrast, in the latter example the speaker is ignorant about who constitutes the reference of the set of students that cheated in the exam.

What is important for our purposes is the fact that in the above examples the indefinite quantifiers alcuni/alguns/quelques, as well as their covert counterparts in F and I, are used when the speaker is ignorant (Alonso-Ovalle & Menéndez-Benito Reference Alonso-Ovalle, Menéndez-Benito, Aloni, Franke and Roelofsen2013, Farkas Reference Farkas2020) or does not have the intent to refer to any particular set of individuals, and there is no referential anchoring in context to such a set. Hence, absence of specificity and absence of referential intent (von Heusinger Reference von Heusinger2000a, Reference von Heusingerb, Reference von Heusinger, von Heusinger, Maienborn and Portner2011) appear to be the hallmark of anti-specific indefinites. Consider in this regard the examples in (40). These examples show that it is false that algunos must be linked to a previously introduced context-sensitive set (Gutiérrez-Rexach Reference Gutiérrez-Rexach2001, Reference Gutiérrez-Rexach2010; Martí Reference Martí2008b, Reference Martí, Giannakidou and Rathert2009). (40a) can be part of the description of a village we do not know anything about, whereas (40b) can be the headline of a news about a Parliament meeting. In these situations, the domain, but not the set of entities being referred to by the indefinite expressions in preverbal subject position, can be assumed to be discourse linked (Pesetsky Reference Pesetsky, Reuland and ter Meulen1987).

In both examples the choice of algunos (versus other available indefinite quantifiers in the language) conveys the meaning that the speaker, even though (s)he might be able to identify the entities that satisfy the claim, does not want to make the hearer aware of this identification. It might also be the case that the speaker is ignorant about the reference of these entities. Our hypothesis concerning the speaker’s ignorance associated with indefinite expressions headed by the Q algunos is that they denote sets of individuals whose reference is not part of the speaker’s epistemic state. That is, whereas indefinite expressions headed by the Q un(o)s may denote a specific set of individuals that are part of the speaker’s epistemic state, the alg- component leads to elimination of this specificity. Following Stephenson’s (Reference Stephenson2007) analysis of epistemic modals, we represent the meaning of alg- as follows (Stephenson’s judge is, for the present purposes, identified with the speaker): alg forces to consider a world where some entities exist that is not part of the epistemic state of the speaker (or part of the shared knowledge with the hearer, for which the * symbol is used).Footnote 35

Supposing that D⟨e⟩ contains three individuals {a, b, c}, then by using a specific unos the speaker knows and has the intent to refer to a specific subset of the set of possible combinations of the members of D (i.e. {{a,b} ∧ {b,c} ∧ {a,c}} in w'. By contrast, by using algunos reference is made to a set of individuals in w" that the speaker is ignorant about (i.e. it is not part of his epistemic state or the epistemic state shared with the hearer). Therefore, the set of individuals D'⟨e⟩ referred to in w" is distinct from D, which means that it can be larger than D or an unknown subset of D. Under this approach the referential vague indefinites in the previous examples introduce alternative values in the domain (i.e. indeterminacy of discourse referents) without an implicature of domain exhaustification.Footnote 36

From a morphosyntactic perspective we postulate our third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 The anti-specific reading of indefinite expressions is obtained by adjoining an operator alg to a quantifier inherently valued for specificity, with the result that the modifying operator deprives the quantificational phrase of this property.

Hence, we postulate that, by adjoining to Q, the operator alg cancels specificity. Consider the structure in (42).

Both the Q that encodes specificity (see Section 4) and the operator alg that cancels it can be null. To account for this variation, we claim that at the last stage of the mapping from syntax to phonology (Nevins Reference Nevins and Trommer2012; i.e. at the stage of exponence and allomorph selection of Vocabulary Insertion), different languages make different choices for the alg operator: while BP, C, I and S have the vocabulary item alg-, F has quelqu-, and both F and I can even have a null realization.Footnote 37

The syntactic structure in (42) represents the idea that whereas indefiniteness builds on definiteness (i.e. de is adjoined to D, with the effect of canceling the definiteness of D), anti-specificity builds on specificity (i.e. alg is adjoined to Q, with the effect of canceling the specificity of Q). In other words, by eliminating the reference value of the individuals quantified over, alg behaves similarly to the operator de that cancels definiteness at the lower determiner level and at the same time it introduces a higher layer in the syntactic indefinite hierarchy.Footnote 38

Two predictions follow from the present analysis of quantificational anti-specificity. First, because it is syntactically adjoined to Q, alg can show scope interactions with other quantifiers. Second, in spite of being semantically anti-specific, alg can occur in syntactic topic position.

The structure in (42) represents the idea that alg is a structural modifier of Q. As such, indefinite anti-specific quantifiers admit wide and narrow scope with respect to other quantifiers, exactly like other quantificational expressions.

We next show that anti-specific quantifiers may occur as topics.Footnote 39 This is something unexpected since, by definition, topics introduce a referential anchoring to a particular individual previously introduced in the discourse, and therefore are expected to convey specificity (Cohen & Erteschik-Shir Reference Cohen and Erteschik-Shir2002). Consider in this respect the data in (44) (from Etxeberria & Giannakidou Reference Etxeberria and Giannakidou2017: 18 exx. (63) and (61)).

Note that in (44a, b) algunos alumnos is strictly speaking not D-linked (Pesetsky Reference Pesetsky, Reuland and ter Meulen1987) to a previous discourse antecedent: both speaker and hearer can make similar assumptions about the domain (that is, talking about students can be considered ‘familiar’ with respect to their most accessible context), but the set of students is not shared by speaker and hearer precisely because of the fundamental status of algunos. Still, this indefinite phrase constitutes the topic of the sentence: it is used to talk about a domain of individuals in the common ground that the sentence is about. This is proved by the fact that unaccusative verbs such as llegar ‘to arrive’ usually combine with postverbal indefinite subjects, but in these examples algunos alumnos occurs in preverbal position.Footnote 40

Therefore, we agree with Etxeberria & Giannakidou (Reference Etxeberria and Giannakidou2017) that in (44a) the set of entities denoted by the indefinite expression is not context-dependent, and it contributes a presupposition of referential vagueness, since instructor B does not know the reference of all the individuals satisfying the existential claim. As such, it can be followed by an expression such as y no sé quién más ‘and I don’t know who else’ (44a) that overtly states the speaker’s ignorance, but crucially it cannot be followed by a list of names that exhausts all the referents in discourse (44b). Thus, the coda in (44a) implies that the names of the students are a proper subset of the total set of individuals that arrive late, and it makes explicit that the speaker is not interested in (or he is ignorant of) the identity of the particular individuals that form that set. In this way the well-formedness of this example is due to the fact that the only possible interpretation it has is that there are various subpluralities of individuals available, and the coda guarantees reference to a set of individuals that is not identified by the speaker, instructor B. Note that this reading is not available in (44b).

Before we close this section, it should also be noted that, under the present analysis of anti-specificity, the operator alg is at the top of an indefiniteness hierarchy to ensure that it cancels specificity by turning reference to a specific set of entities into reference to a set of individuals for which the reference value is not part of the speaker’s epistemic state. In semantic terms it type-shifts a generalized quantifier (the one conveying specificity) into a modified generalized quantifier (conveying anti-specificity), and it is of type ⟨⟨⟨e,t⟩t⟩,⟨⟨e,t⟩t⟩⟩.

Finally, note that Martí’s (Reference Martí, Giannakidou and Rathert2009) claim that algunos contributes a partitive implicature (or partitive effect) follows straightforwardly from our proposal that alg (in a sentence such as Algunos alumnos han llegado tarde ‘Some students arrived late’) not only entails the existence of a set x, but it also entails that the domain D' that x belongs to is either larger than D (D⊆D') or an unknown subset of D (D'⊆D), thus conveying a partitive effect.

To sum up, in this section we have argued that alg, which encodes speaker’s ignorance, is an operator head-adjoined to a Q encoded for specificity. The output of this operation is a modified generalized quantifier deprived of specificity.

6. Conclusions and further predictions

In this paper we have addressed the expression of indefiniteness, specificity and anti-specificity in five Romance languages, namely BP, C, F, I, and S.

Our analysis postulates a new, unified, syntactically-driven approach to an indefiniteness hierarchy of functional heads that accounts for the compositionality of the various meanings associated with indefinite expressions.

We have argued that indefiniteness in Romance builds on definite plural nominals, and that an operator de cancels definiteness by modifying a definite plural D. This operator de semantically shifts entity-type expressions into property-type expressions, and morphophonologically speaking can be instantiated as de in some Romance languages and in some constructions, while in others it has a zero realization. We have extended this analysis to indefinite mass nouns.

We have introduced a new syntactic analysis of specificity according to which weak quantifiers are merged with indefinite de-phrases. Semantically, they shift property type expressions into generalized quantifiers. In addition to scopal specificity, we have shown that some weak indefinites (i.e. F and I des/dei phrases) may also license a strong referential or epistemic reading via a Skolemized choice function.

Building on specificity, we have also argued that in our syntactically-oriented approach, anti-specificity is created by means of an operator alg that interacts with a Q that encodes specificity and cancels it. This operator semantically takes a generalized quantifier as input and yields a modified generalized quantifier as output.

We conclude by pointing out that, in addition to the general predictions on how indefiniteness, specificity and anti-specificity are syntactically structured and expressed in Romance, our analysis also makes interesting predictions for two unrelated phenomena: the expression of standard partitivity and pseudopartitivity in Romance.

Assuming that a partitive head is a bi-relational abstract functional head that mediates between definite nominal complements that denote the whole and nominal phrases that denote proper subparts (Barker Reference Barker1998, Zamparelli Reference Zamparelli2008), we predict that in the specifier position of standard partitives only those quantificational structures (denoting either specificity or anti-specificity) are allowed, but not indefinite de-phrases, since the latter are not quantificational. We also predict that in the complement position of pseudopartitives only an indefinite de-phrase is allowed, but not quantificational structures. Both predictions appear to be borne out (Espinal & Cyrino Reference Espinal and Cyrino2021).

Overall, our syntactically-driven analysis is able to provide in a novel way a comprehensive understanding of the compositionality of meaning that different types of indefinite expressions have in Romance. Thus, it contributes to the ongoing discussion about the relevance of the study of meaning at the syntax–semantics interface.