1 Introduction

The central topic of this paper is the criteria used for distinguishing syntactic categories and for assigning a particular phrase to a particular category in any given instance; for example, on what basis do we assign the phrase the dogs to category N (or D) as an NP (or DP) but the phrase ate biscuits to category V (as a VP)? Kornfilt & Whitman (Reference Kornfilt and Whitman2011: 1297–1298) distinguish two main approaches to defining syntactic categories, one of which they label ‘distributionalist’, the other ‘essentialist’. The former refers to the exclusive use of syntactic criteria to define categories, while the latter refers to the use of nonsyntactic criteria, such as lexical semantics, to define categories. These are not two mutually exclusive positions, of course, and some approaches to syntactic categories draw on both syntactic and nonsyntactic criteria; this is the case, for example, with Baker’s (Reference Baker2003) approach to the theory of categories.

The definition of syntactic categories is a huge topic with fundamental consequences for the theory of grammar, a comprehensive treatment of which is not possible within the confines of this paper. Here, I present a detailed exploration of the distributionalist approach to syntactic categorization, focusing on the definition of syntactic categories within a grammatical framework which is, in principle, fundamentally ‘distributionalist’: Lexical-Functional Grammar (LFG) (Kaplan & Bresnan Reference Kaplan, Bresnan and Bresnan1982; Dalrymple Reference Dalrymple2001; Bresnan et al. Reference Bresnan, Asudeh, Toivonen and Wechsler2016).

The criteria used for assigning a particular phrase to a particular category are most evident in cases of apparent mismatch, that is, when a phrase appears to show properties of more than one syntactic category. For example, in (1), the phrase his stupidly missing the penalty shows both nominal properties (possessive his used as if a subject noun phrase) and verbal properties (object the penalty, adverb stupidly):

Such ‘mixed projections’ have been the subject of recent work within LFG, revealing the use of three distributionalist criteria for distinguishing categories:Footnote [2]

Despite the widespread use of all three criteria as independently sufficient for syntactic categorization, I argue that the evidence of mixed projections requires only the first to be a necessary and sufficient criterion for syntactic categorization within a distributionalist approach.Footnote [3] Distribution and morphology are not sufficient conditions for categorization. This leaves internal syntax, that is, differences in the internal structural possibilities of different phrase types, as the central distributionalist criterion for distinguishing syntactic categories. The narrow consequences of this are that several phenomena that have been labelled as mixed projections in LFG are not, in fact, true instances of category mixing. The broader consequences reach beyond the confines of this paper, raising wider questions regarding the use of syntactic criteria in both purely and partially distributionalist approaches to syntactic categorization.

I begin in Section 2 by introducing the approach to syntactic categorization adopted in LFG. I then focus on three (supposed) mixed projection phenomena which have been the subject of analysis within LFG: the Arabic masdar, the English gerund and attributive participles in Sanskrit. The Arabic masdar is an example of a mixed projection which cannot be adequately analysed on the assumption that all three criteria above are independently sufficient for categorization: either distribution must trump internal syntax, or vice versa. Having proposed an analysis in which internal syntax trumps distribution, I then show that there is no need to treat distribution as a sufficient criterion for categorization in relation to the English gerund. In the case of attributive participles, both distribution and morphosyntax have been called upon as sufficient criteria for categorization, but I argue that this does not hold.

2 Syntactic categories in Lexical-Functional Grammar

2.1 Lexical-Functional Grammar

LFG is a strongly lexicalist, constraint-based framework for grammatical analysis. A crucial feature of LFG is the representation of different types of grammatical information in different ‘projections’. The central levels of syntactic representation are c(onstituent)-structure, for surface constituency relations and grammatical category information, represented using the familiar ‘tree’ diagram, and f(unctional)-structure, represented as an attribute-value matrix, for more abstract syntactic relations such as grammatical subject and object, and unbounded dependencies (such as between a fronted question phrase and its corresponding gap). F-structure is ‘projected’ from c-structure via a projection function,

![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$

, and c-structure nodes are annotated so as to constrain the formation of f-structure on the basis of c-structure. Example (3) shows the c-structure and f-structure for the sentence Henry likes trains, indicating the projection of f-structure from c-structure by means of the arrows between the two.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$

, and c-structure nodes are annotated so as to constrain the formation of f-structure on the basis of c-structure. Example (3) shows the c-structure and f-structure for the sentence Henry likes trains, indicating the projection of f-structure from c-structure by means of the arrows between the two.

The symbols

![]() $\uparrow$

and

$\uparrow$

and

![]() $\downarrow$

in the c-structure annotations in (3) are metavariables, defined as in (4), where

$\downarrow$

in the c-structure annotations in (3) are metavariables, defined as in (4), where

![]() $\ast$

refers to the current c-structure node and

$\ast$

refers to the current c-structure node and

![]() $\hat{\ast }$

refers to the mother of the current c-structure node.

$\hat{\ast }$

refers to the mother of the current c-structure node.

So the specification (

![]() $\uparrow$

subj)

$\uparrow$

subj)

![]() $=\downarrow$

on the specifier of IP in (3) constrains the formation of the f-structure such that the f-structure projected from the phrase in SpecIP (

$=\downarrow$

on the specifier of IP in (3) constrains the formation of the f-structure such that the f-structure projected from the phrase in SpecIP (

![]() $\downarrow$

) must serve as the value of subj in the f-structure projected from the mother IP node (

$\downarrow$

) must serve as the value of subj in the f-structure projected from the mother IP node (

![]() $\uparrow$

). Thus, the phrase in SpecIP serves as the subject of the main clausal predicate at f-structure, as shown in (3). The specification

$\uparrow$

). Thus, the phrase in SpecIP serves as the subject of the main clausal predicate at f-structure, as shown in (3). The specification

![]() $\uparrow =\downarrow$

states that the f-structure corresponding to the current node is the same as the f-structure corresponding to the mother of the present node. Structural headedness is understood in these terms: a head or co-head node will necessarily have the specification

$\uparrow =\downarrow$

states that the f-structure corresponding to the current node is the same as the f-structure corresponding to the mother of the present node. Structural headedness is understood in these terms: a head or co-head node will necessarily have the specification

![]() $\uparrow =\downarrow$

.

$\uparrow =\downarrow$

.

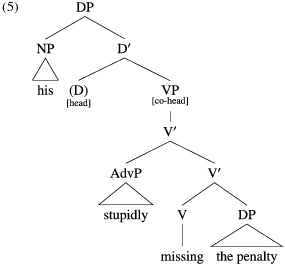

This notion of headedness is crucial to the analysis of mixed projections in LFG. In (1), the adverb and object suggest verbal structure, but the possessive phrase implies nominal structure. The analysis proposed by Bresnan et al. (Reference Bresnan, Asudeh, Toivonen and Wechsler2016: 311–319), essentially identical to that of Bresnan (Reference Bresnan2001: 289–296), involves a ‘head-sharing’ construction, whereby a VP serves as co-head complement within a DP (the DP is the ‘extended head’ of VP):

The D head (the categorial head) itself is absent (indicated in parentheses) but would, if present, be marked with

![]() $\uparrow =\downarrow$

.Footnote

[4]

As a co-head, the VP has the same annotation. In (5) and the subsequent trees, I indicate headedness with ‘[(co-)head]’ for explicitness.

$\uparrow =\downarrow$

.Footnote

[4]

As a co-head, the VP has the same annotation. In (5) and the subsequent trees, I indicate headedness with ‘[(co-)head]’ for explicitness.

Kaplan (Reference Kaplan, Whitelock, Wood, Somers, Johnson and Bennett1987, Reference Kaplan, Huang and Chen1989) generalized the concept of projection functions, extending the scope of the framework to include additional projections representing different kinds of information, for example, s(emantic)-structure as an interface between syntax and semantics (Dalrymple et al. Reference Dalrymple, Lamping, Pereira, Saraswat, Kanazawa, Piñón and Henriette1996, Dalrymple Reference Dalrymple2001, Asudeh Reference Asudeh2012), p(rosodic)-structure for representing grammatically relevant prosodic information (Butt & King Reference Butt, King, Butt and King1998, Mycock Reference Mycock2006, Dalrymple & Mycock Reference Dalrymple, Mycock, Butt and King2011, Bögel Reference Bögel2015) and i(nformation)-structure for the representation of information structural properties of a sentence (Butt & King Reference Butt and King1997, King Reference King, Butt and King1997, Dalrymple & Nikolaeva Reference Dalrymple and Nikolaeva2011). In this paper, my primary concern is syntactic categories, for example, N (noun) and V (verb). LFG represents syntactic category information in the c-structure; c-structure nodes are labelled as, for example, NP or V

![]() $^{\prime }$

, according to category type and level of projection, based on a broadly X

$^{\prime }$

, according to category type and level of projection, based on a broadly X

![]() $^{\prime }$

-theoretic approach to phrase structure. Following Kaplan (Reference Kaplan, Huang and Chen1989), the relation between a c-structure node and its label is itself a projection, although it is not usually represented as such: the label of a particular node is projected from the node via a function

$^{\prime }$

-theoretic approach to phrase structure. Following Kaplan (Reference Kaplan, Huang and Chen1989), the relation between a c-structure node and its label is itself a projection, although it is not usually represented as such: the label of a particular node is projected from the node via a function

![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}$

.Footnote

[5]

This means that c-structure models only surface constituency relations, while syntactic category status is represented separately.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}$

.Footnote

[5]

This means that c-structure models only surface constituency relations, while syntactic category status is represented separately.

An LFG grammatical architecture, therefore, would include at least the projections in (6); the ‘string’, from which the c-structure is projected, represents the linguistic signal parsed into syntactic units.

The crucial point for the present topic is that different types of grammatical information are represented separately; even syntactic information is not treated as an undifferentiated whole. The use of projection functions to separate out grammatical information in this way means that the different structures, and the information contained within them, are relatively encapsulated. Syntactic categorization is therefore treated as a distinct aspect of grammar, obviously related to other aspects of grammar, but not merely an epiphenomenon of the interaction of those aspects. This makes LFG an ideal framework within which to examine the definition of syntactic categorization.

Most work in LFG assumes a finite set of major categories. For example, Dalrymple (Reference Dalrymple2001: 52–54) assumes five major lexical categories, N(oun), V(erb), P(reposition), Adj(ective) and Adv(erb) as well as the functional categories I and C.Footnote [6] Other functional categories are sometimes assumed in LFG work, for example, D, K (case) and Q(uantifier), as well as a number of ‘minor’ categories which cannot project phrases, for example, ‘Part’ (particles), and one or more exocentric categories, for example, S, which can contain a predicate along with any or all of its arguments, including the subject.

2.2 Decomposing categories

In this work, the only categories of concern are the major lexical categories N, V, P and A(dj/dv). Bresnan et al. (Reference Bresnan, Asudeh, Toivonen and Wechsler2016: 103) propose that the major lexical categories N, V, P and A can be analysed according to the following categorial feature matrix:Footnote [7]

‘Predicative’ categories require an external subject of predication, while only ‘transitive’ categories may govern objects. In addition to this, for Bresnan et al. (Reference Bresnan, Asudeh, Toivonen and Wechsler2016), categories are specified for the level of projection, 0, 1 or 2 (corresponding to X, X

![]() $^{\prime }$

or XP) and as functional (with two levels, F1 and F2) or not functional, which permits the inclusion of the functional categories I, C and D: I is [

$^{\prime }$

or XP) and as functional (with two levels, F1 and F2) or not functional, which permits the inclusion of the functional categories I, C and D: I is [

![]() $+$

predicative,

$+$

predicative,

![]() $+$

transitive] and F1, C is [

$+$

transitive] and F1, C is [

![]() $+$

predicative,

$+$

predicative,

![]() $+$

transitive] and F2, and D is [

$+$

transitive] and F2, and D is [

![]() $-$

predicative,

$-$

predicative,

![]() $-$

transitive] and F1. Thus, I and C are functional categories corresponding to the lexical category V in terms of the feature matrix, and D is a functional category corresponding to the lexical category N in the same terms. This feature matrix permits Bresnan et al. (Reference Bresnan, Asudeh, Toivonen and Wechsler2016) to state constraints on the possible combinations of functional and lexical heads; for example, they propose that NP, AdjP and PP may not function as a complement to IP or CP.

$-$

transitive] and F1. Thus, I and C are functional categories corresponding to the lexical category V in terms of the feature matrix, and D is a functional category corresponding to the lexical category N in the same terms. This feature matrix permits Bresnan et al. (Reference Bresnan, Asudeh, Toivonen and Wechsler2016) to state constraints on the possible combinations of functional and lexical heads; for example, they propose that NP, AdjP and PP may not function as a complement to IP or CP.

This is a somewhat restricted decomposition of syntactic categories, leaving no room for a distinction between Adj and Adv (as argued for by Payne, Huddleston & Pullum Reference Payne, Huddleston and Pullum2010) and saying nothing about minor or exocentric categories. More important for the present purposes, however, is the fact that the feature matrix in (7) is not intended as a way of deconstructing syntactic categories but only as a way of cross-classifying them in order to state restrictions on the combination of lexical and functional categories or, more generally, as a way of permitting some categories to be grouped together in distinction from other categories. That is, N, V, P and A remain, but we are now able to state, should we so desire, that V and A pattern together in a certain respect in contrast to N and P by virtue of their having the feature [

![]() $+$

predicative]. Underspecification in terms of the ‘F’ feature is not impossible: for example, English auxiliaries may appear either in I or C, and similarly Hristov (Reference Hristov2013) argues that some pronouns in English may be either N or D. However, underspecification in terms of the features distinguishing lexical categories is not admitted (and would in any case not be sufficient to deal with mixed projections).

$+$

predicative]. Underspecification in terms of the ‘F’ feature is not impossible: for example, English auxiliaries may appear either in I or C, and similarly Hristov (Reference Hristov2013) argues that some pronouns in English may be either N or D. However, underspecification in terms of the features distinguishing lexical categories is not admitted (and would in any case not be sufficient to deal with mixed projections).

2.3 Complex categories

Besides cross-classification across categories, there is another respect in which syntactic categories are not purely atomic in LFG. In any language, some members of a particular syntactic category are likely to differ from other members of the same category in respect of one or more properties. For example, category V in English is standardly assumed to contain both finite verb forms and nonfinite verb forms, for example, infinitives; it also contains intransitive, transitive and ditransitive verbs. The concept of complex categories (Butt et al. Reference Butt, King, Niño and Segond1999: 192) permits generalizations to be made over a subset of members of a category. For example, we might assume a phrase-structure rule, such as the following, for English:

Assume that at least all nonhead elements on the right-hand side of a phrase-structure rule are optional, that is, assume that this rule licenses either V NP or simply V as daughters of V

![]() $^{\prime }$

. If we have only an undifferentiated category V, then the rule in (8), besides licensing grammatical structures like VPs consisting only of an intransitive verb and VPs consisting of a transitive verb and an NP complement, also licenses VPs consisting of an intransitive verb followed by an NP object complement and VPs consisting of a transitive verb with no object complement. Of course, these ungrammatical possibilities can be ruled out at other levels of analysis: in LFG, the principles of completeness and coherence require that only and all subcategorized governable grammatical functions appear in an f-structure so that, for example, an NP object phrase could not appear if the governing verb does not subcategorize for one. Another possibility, however, is to distinguish different subcategories of category V, so as to distinguish transitive from intransitive verbs in the phrase-structure rules. Then, instead of (8), we can assume the following:

$^{\prime }$

. If we have only an undifferentiated category V, then the rule in (8), besides licensing grammatical structures like VPs consisting only of an intransitive verb and VPs consisting of a transitive verb and an NP complement, also licenses VPs consisting of an intransitive verb followed by an NP object complement and VPs consisting of a transitive verb with no object complement. Of course, these ungrammatical possibilities can be ruled out at other levels of analysis: in LFG, the principles of completeness and coherence require that only and all subcategorized governable grammatical functions appear in an f-structure so that, for example, an NP object phrase could not appear if the governing verb does not subcategorize for one. Another possibility, however, is to distinguish different subcategories of category V, so as to distinguish transitive from intransitive verbs in the phrase-structure rules. Then, instead of (8), we can assume the following:

It is still possible to refer to category V as a whole in a phrase-structure rule, if required; but distinguishing subcategories of V in this way rules out ungrammatical structures such as an intransitive verb plus an object in the phrase structure, rather than requiring reference to another level of analysis. Maxwell & Kaplan (Reference Maxwell and Kaplan1994) investigate the relative merits of treating such phenomena either in terms of phrasal constraints, as in (9), or in terms of functional constraints resolved by unification in the f-structure. They show clearly that distinguishing mutually exclusive classes of some major categories in the c-structure, rather than in the f-structure, is considerably more efficient in terms of parsing time. That is, from a processing perspective, it is far better to eliminate major sets of impossible structures in the context-free phrase-structure rules than in the unification-based feature structure. Thus, it is preferable, for example, to distinguish between transitive and intransitive verbs in the phrase structure than to leave it to the f-structure to rule out sentences like *Bill sneezed Colin and *Bill devoured. It is important to note that this does not mean there is not also a functional difference between transitive and intransitive verbs; they retain the same functional and semantic differences in terms of subcategorization, but it is computationally more efficient to distinguish them also at the phrase-structure level. I assume henceforth that this approach is practically advantageous, given the importance of constraining the processing inefficiency of unification in a unification-based framework like LFG.Footnote [8]

Going beyond processing, however, there are important theoretical considerations when it comes to deciding whether particular phenomena should or should not be modelled in the phrase structure as well as at some other level of the grammar. Just because a particular phenomenon can be modelled in the f-structure or even semantics does not mean it should necessarily be modelled only at that level. For example, the fact that only nouns can take determiners could be given a purely semantic explanation: the semantic contribution of a determiner is such that it can occur only with a noun and not with a verb, adjective, etc. But this fact could also be given a featural syntactic explanation (the featural contribution of a determiner is only compatible with noun phrases) and even a structural explanation (the phrase-structure rules only license Ds with NPs). In fact, all three levels of explanation may be valid: a phrase structural constraint on determiners seems eminently reasonable, but this no doubt correlates with a featural properties of noun phrases and with the semantics. Ultimately, it is preferable to model a phenomenon at multiple levels unless there are good reasons not to: there is a methodological danger in, for example, assigning purely to the semantics phenomena which could reasonably have both a syntactic and semantic explanation since it could be (and often is) the case that such assignments are made primarily to avoid a difficulty in the syntactic analysis, rather than on principled grounds.

Once again, processing considerations aside, it remains conceptually useful to be able to distinguish subcategories of larger syntactic categories, allowing us to increase the differentiation of syntactic categories without losing the ability to make generalizations over larger categories (such as V). It is important to note, however, that complex categories permit subcategorization within fully defined and fully distinct categories, for example, subcategories of N or V, but do not permit any kind of intermediate status between N and V.

2.4 Dual categoriality

The central issue for any approach to mixed projections is how to deal with their apparent dual categoriality. As illustrated in (5), the standard LFG approach involves a ‘head-sharing’ structure in which a verbal projection is embedded within a nominal projection. By the feature specifications discussed in the preceding section, D is a functional version of N and differs in categorial features from V. The structure in (5) is therefore a ‘mixed’ construction in a sense that a VP complementing I (as in (3)) is not: in the latter case, both projections share the same category features ([

![]() $+$

predicative,

$+$

predicative,

![]() $+$

transitive]) and differ only in terms of the functionality feature; in this case, the two projections crucially differ in terms of category features. The phrase is therefore partly nominal and partly verbal.

$+$

transitive]) and differ only in terms of the functionality feature; in this case, the two projections crucially differ in terms of category features. The phrase is therefore partly nominal and partly verbal.

The type of mixed construction seen in (5) involves a lexical category serving as a complement to a functional category. It is also possible, however, for a ‘mixed’ construction to involve a lexical category with a different lexical category as its extended head. Following Mugane (Reference Mugane1996) and Bresnan & Mugane (Reference Bresnan, Mugane, Butt, Dalrymple and King2006), ![]() nominalizations involve a VP with NP as its extended head:

nominalizations involve a VP with NP as its extended head:

In this example, the head of the phrase, ![]() ‘slaughterer’, is categorially a noun but also serves functionally as the head of the VP, which licenses the object phrase, here mbũri ‘goat’.

‘slaughterer’, is categorially a noun but also serves functionally as the head of the VP, which licenses the object phrase, here mbũri ‘goat’.

Other types of head-sharing construction have also been proposed. For example, Nikitina (Reference Nikitina2008) proposes that IP may take DP as an extended head, while Bresnan et al. (Reference Bresnan, Asudeh, Toivonen and Wechsler2016) allow the exocentric category S to take DP as extended head, and, similarly, Nikitina & Haug (Reference Nikitina and Haug2016) permit S to take NP as an extended head. These latter possibilities will be discussed below.

It is important to note that the LFG approach to mixed projections violates a strict approach to endocentricity, both in the fact that words may head phrases of different categories and in the fact that lexical phrases are permitted to lack an explicit head internal to the phrase. This is not to say that the approach is therefore not viable. Endocentricity is an important cross-linguistic tendency; in some grammatical theories, it is elevated to a syntactic universal but not within LFG. LFG adopts a relatively loose approach to X

![]() $^{\prime }$

theory, conforming wherever possible but treating X

$^{\prime }$

theory, conforming wherever possible but treating X

![]() $^{\prime }$

theoretic principles as violable where a particular language does not conform.Footnote

[9]

But the fact that endocentricity is a strong cross-linguistic tendency means that its violation in the case of mixed projections should be treated as marked. For example, in the Optimality Theoretic approach to LFG developed by Bresnan (Reference Bresnan, Dekkers, Leeuw and Weijer2000), endocentricity derives from a set of universal syntactic constraints; exocentric structures may occur where competing constraints are more highly ranked, but it remains the case that all else being equal, nonendocentric structures are dispreferred in comparison with endocentric structures.Footnote

[10]

Thus, in principle (again, all else being equal), mixed projections should be admitted only where an alternative, X

$^{\prime }$

theoretic principles as violable where a particular language does not conform.Footnote

[9]

But the fact that endocentricity is a strong cross-linguistic tendency means that its violation in the case of mixed projections should be treated as marked. For example, in the Optimality Theoretic approach to LFG developed by Bresnan (Reference Bresnan, Dekkers, Leeuw and Weijer2000), endocentricity derives from a set of universal syntactic constraints; exocentric structures may occur where competing constraints are more highly ranked, but it remains the case that all else being equal, nonendocentric structures are dispreferred in comparison with endocentric structures.Footnote

[10]

Thus, in principle (again, all else being equal), mixed projections should be admitted only where an alternative, X

![]() $^{\prime }$

theoretic, analysis accounts for the linguistic data less adequately.

$^{\prime }$

theoretic, analysis accounts for the linguistic data less adequately.

Bresnan (Reference Bresnan, Butt and King1997) contrasts her exocentric ‘head-sharing’ approach, illustrated in (5), with the ‘indeterminate category projection theory’ and ‘projection-switching’ approaches. Under an ‘indeterminate’ approach, the head would be underspecified such that its phrase could display features of more than one category; under ‘projection-switching’ approaches, as proposed, for example, by Abney (Reference Abney1987), Lapointe (Reference Lapointe, Kathol and Bernstein1993), Wescoat (Reference Wescoat1994), Hudson (Reference Hudson2003) and Malouf (Reference Malouf2000), the head of a mixed projection is assumed to have an intermediate (rather than indeterminate) or dual category status, which enables it to project up to a certain level as if it were one category (e.g. a verb) and above that level as another category (e.g. a noun).

For example, Lapointe (Reference Lapointe, Kathol and Bernstein1993) proposes that category labels are bipartite, the first part determining external syntactic properties such as distribution (2b) and the second determining internal syntax (2a). So, Lapointe argues for an intermediate category (a ‘dual lexical category’)

![]() $\langle \text{N}|\text{V}\rangle$

to account for the English gerund, which projects verbally (ensuring verbal internal syntax), except for its top layer (ensuring it has the distribution of a noun phrase), and the -ing suffix has a morphological function in deriving a category

$\langle \text{N}|\text{V}\rangle$

to account for the English gerund, which projects verbally (ensuring verbal internal syntax), except for its top layer (ensuring it has the distribution of a noun phrase), and the -ing suffix has a morphological function in deriving a category

![]() $\langle \text{N}|\text{V}\rangle$

from a plain category

$\langle \text{N}|\text{V}\rangle$

from a plain category

![]() $\langle \text{V}|\text{V}\rangle$

.

$\langle \text{V}|\text{V}\rangle$

.

More sophisticated projection-switching approaches remain the standard approach to mixed projections within mainstream transformationalist grammar. For example, Alexiadou, Iordăchioaia & Schäfer (Reference Alexiadou, Iordăchioaia, Schäfer, Sleeman and Perridon2011) analyse nominalizations in Romance and Germanic in terms of DP projections which contain verbal functional projections; so for them, the English gerund of the type seen in (1) (their ‘English verbal gerund’) has the following structure:

Within such an approach, nominalizations may vary as to how much verbal, and indeed nominal, structure is included in the projection. More verbal nominalizations contain more verbal projections; for example, Alexiadou et al. (Reference Alexiadou, Iordăchioaia, Schäfer, Sleeman and Perridon2011) analyse ‘Spanish verbal infinitives’ as projecting also a tense phrase in addition to the verbal projections in (11), whereas the purely nominal English gerund (their ‘English nominal gerund’, shown in (25a)) projects only to the VoiceP in terms of verbal projections, while also containing additional nominal projections, such as NumberP and nP.

Within LFG, such a variation in terms of the abstract verbal/nominal features of nominalizations would not ordinarily play out in the phrase structure but would be captured at the level of f-structure, where tense, aspect and such features are represented. Moreover, the possibility of head movement within transformationalist approaches means that structures such as those in (11) may be proposed without necessitating the head to surface at the bottom of the projection; as discussed below, this is not the case in LFG, which Bresnan (Reference Bresnan, Butt and King1997) takes as evidence (within the assumptions of LFG) against a projection-switching approach.

In the Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar analysis by Malouf (Reference Malouf1996, Reference Malouf2000), the mixed properties of the English gerund are accounted for by means of the multiple inheritance hierarchy for head values. The head value gerund is a subtype of both noun and relational. As a subtype of noun, its external distribution is that of an NP (it can ‘occur anywhere an NP is selected for’ (Malouf Reference Malouf1996: 262)) and does not necessarily correspond to the distribution of verbs (which are a separate subtype of relational). Adverbial modification applies to elements of category relational (which includes adjective). Since adjectives modify only c(ommon)-nouns, gerund phrases cannot be modified by adjectives. This is a sophisticated intermediate category analysis, the use of a multiple inheritance hierarchy permitting cross-classification across more than one grammatical category: it is possible to define a category that shares some features with nouns and some with verbs, without requiring it to be fully one or the other.

It would not be immediately possible to transfer Malouf’s proposal into LFG since LFG does not make use of multiple inheritance hierarchies and does not admit mixed categories in the sense of permitting categories which are partially of one superordinate category and partially of another superordinate category. On the other hand, it would conceivably be possible to model mixed projections using either a projection-switching approach similar to Alexiadou et al.’s (Reference Alexiadou, Iordăchioaia, Schäfer, Sleeman and Perridon2011) or an indeterminate approach. However, Bresnan (Reference Bresnan, Butt and King1997) argues strongly in favour of the ‘head-sharing’ approach on two grounds. First, there is strong evidence for the principle of ‘phrasal coherence’: in mixed projections, ‘the hybrid construction can be partitioned into two categorially uniform subtrees such that one is embedded as a constituent of the other’ (Bresnan Reference Bresnan, Butt and King1997: 4).Footnote [11] There are no clear counterexamples where, for example, a projection is mixed in such a way that no distinct verbal and nominal subtrees can be distinguished. This generalization rules out an approach to mixed categories involving an indeterminate, or underspecified, head.

Second, Bresnan (Reference Bresnan, Butt and King1997) argues that projection-switching, or intermediate, category approaches are inadequate because they require the head to be positioned in the lower projection (as in (5), where the head is in V, not D). It is important to note that this criticism applies only within the nontransformational assumptions of LFG. In a theory of phrase structure which permits movement, the surface position of the head may not correspond to its base position. But LFG assumes that constituent structure represents only the surface constituency. Thus, if we are dealing with a single projection, which at some point switches from one category to another or which displays some properties of one category and others of another while remaining a single projection, it is just a fact about phrase structure (so conceived) that the head must surface at the bottom of the projection concerned. Bresnan discusses a number of examples which show that in some languages, the head must surface in the higher projection of a head-sharing structure;Footnote [12] that is, the head cannot occur in the position expected under a projection-switching analysis. Thus, intermediate category analyses which require the head to be in the lower position are ruled out, and the head-sharing approach, which is in other respects largely equivalent, is in this respect preferable.

In this way, Bresnan’s head-sharing model could not unreasonably be seen as a nontransformational variant of the mainstream projection-switching approach. In both approaches, the phrase structure involves, for example, a verbal projection embedded within, for example, a nominal projection, with the lexical head serving as the head of both projections. Since in LFG the c-structure represents only the surface constituent structure, with no movement, this abstract headship must be represented at the level of f-structure (hence the definition of head and co-head in terms of the

![]() $\uparrow =\downarrow$

annotations), and the head must be permitted to appear (i.e. be generated) in the head of the higher phrase. The other main difference between the head-sharing model of Bresnan and a standard projection-switching approach is the larger inventory of functional heads assumed in mixed projections under the latter analysis; once again, this is due to the restriction of LFG’s c-structure to the representation of surface constituency relations, functional properties being represented at the level of f-structure. Thus, differences of framework aside, the head-sharing and projection-switching approaches are almost entirely equivalent.

$\uparrow =\downarrow$

annotations), and the head must be permitted to appear (i.e. be generated) in the head of the higher phrase. The other main difference between the head-sharing model of Bresnan and a standard projection-switching approach is the larger inventory of functional heads assumed in mixed projections under the latter analysis; once again, this is due to the restriction of LFG’s c-structure to the representation of surface constituency relations, functional properties being represented at the level of f-structure. Thus, differences of framework aside, the head-sharing and projection-switching approaches are almost entirely equivalent.

In this paper, I adopt the head-sharing approach of Bresnan (Reference Bresnan, Butt and King1997). As noted also by Hudson (Reference Hudson2003: 585) and Panagiotidis (Reference Panagiotidis2015: 136), the majority of theoretical models share fundamental similarities, and the differences between head-sharing and projection-switching are not crucial to the concerns of this paper. Rather, what is of primary interest is the criteria used to determine dual categoriality however that is modelled. In almost all previous approaches, for example, distribution is taken as sufficient evidence for categorization, such that a phrase with verbal internal syntax but with the distribution of a noun phrase must have mixed categorization. The question at hand is whether this holds.

3 The Arabic masdar

As discussed above, work on mixed projections in LFG reveals three criteria used for categorization: internal syntax, distribution and morphosyntax. In the default case, for example, in the case of unexceptional noun phrases or verb phrases, these criteria align, and so the question of whether each of these criteria is independently sufficient for categorization or whether one is crucial while the others merely happen to match up does not arise. It is only when we find a mismatch among these three properties that we can begin to investigate which are truly crucial to categorization. If we find a mismatch between two properties both of which are independently sufficient to justify a syntactic categorization, then we must be dealing with a phrase which has dual categoriality, that is, a mixed projection.

The default approach in the existing work on mixed projections is that all three criteria under consideration are independently sufficient for categorization. However, the evidence of the Arabic masdar shows that this cannot be maintained.Footnote [13] The Arabic masdar seems to be a clear instance of a mixed projection; there are two possibilities for its internal syntax, and at least one of these unambiguously involves both nominal and verbal internal syntax. However, if morphosyntax, internal syntax and distribution are all taken as independently sufficient for categorization, it becomes impossible to provide a plausible account. I begin by discussing the recent analysis of Börjars et al. (Reference Börjars, Madkhali, Payne, Butt and King2015), who attempt to deal with the problem by disregarding the criterion of internal syntax. I show that their proposals do not provide an adequate account of the data, and I propose an alternative solution, which privileges internal syntax over distribution and morphosyntax.

Data regarding the Arabic masdar formation is provided by Fassi Fehri (Reference Fassi Fehri1993) and Ryding (Reference Ryding2005: 75–83). Börjars et al. (Reference Börjars, Madkhali, Payne, Butt and King2015) distinguish two types of ‘mixed’ masdar construction in Arabic, although they ultimately provide one analysis that covers both. Type A is the more verbal: it can govern an accusative case object, can be modified by adverbs and cannot be modified by adjectives:

Despite these verbal features, the phrase also has nominal features. The masdar itself shows nominal morphosyntax, being marked for case. In terms of internal syntax, the first two words in (12) exemplify the ‘construct state’ construction, which is a typical feature of noun phrases. The distribution of the masdar phrase is the same as ordinary noun phrases. For example, masdar phrases can function as subjects (13) and objects of verbs and as objects of prepositions (14):Footnote [14]

Finite and other nonfinite verb phrases cannot occur in these positions.

The type B masdar construction is more nominal: it shows exactly the same nominal distribution and morphosyntax and possibility of the construct state, but, in addition, it does not permit objects and does permit adjectival modification; the only verbal feature of the construction is that it also allows adverbial modification.

Börjars et al. (Reference Börjars, Madkhali, Payne, Butt and King2015) argue that both types A and B can be analysed in an entirely nominal structure. Since this seems most remarkable in the case of type A, I will focus on this type initially and consider type B subsequently.

The type A Arabic masdar is mentioned by Bresnan (Reference Bresnan, Butt and King1997), who implies a mixed projection analysis. Börjars et al. (Reference Börjars, Madkhali, Payne, Butt and King2015) discuss a number of possible ways in which a traditional mixed projection analysis could be implemented but argue that none are satisfactory. The crucial problem is that the Arabic masdar appears to violate Bresnan’s ‘phrasal coherence’ constraint, mentioned above: the nominal part of the projection does not constitute a ‘categorially uniform subtree’ taking the verbal projection as an embedded constituent but rather appears to be split by the verbal projection. So, if we take distribution to be a sufficient criterion for categorization, then the Arabic masdar phrase must be nominal at the top level; if we take morphosyntax and the internal syntax in the immediate vicinity of the masdar as a sufficient criterion for categorization, then the masdar itself must be of category N, immediately surrounded by a nominal phrase. Yet, the evidence of the wider internal syntax of the phrase requires (assuming that internal syntax is a sufficient criterion for categorization) a verbal projection above the nominal projection at the base of the phrase. That is, if we take all three criteria for categorization to be sufficient, we are forced to accept a structure which can be schematically represented as in the following example:Footnote [15]

As discussed by, for example, Panagiotidis (Reference Panagiotidis2010), such a structure is impossible. Börjars et al. (Reference Börjars, Madkhali, Payne, Butt and King2015) note that such a structure would be unparalleled and therefore relax the criteria for categorization in order to produce a more acceptable structure. They do not question the assumption that morphosyntax and distribution are sufficient evidence for categorization, meaning that the masdar phrase must be nominal at the top and at the bottom. Given that, the only way to avoid the implausible structure in (16) is to discount the criterion of internal syntax and to analyse the phrase as nominal all the way through, despite the fact that it can contain objects and adverbial modifiers.Footnote [16]

Börjars et al. therefore argue that differences in internal syntax do not serve to distinguish categories; for example, they claim that object phrases and adverbial adjuncts can appear inside NPs just as they can within VPs. The structure they propose for the phrase in (12) is given below:Footnote [17]

In this structure, adverb phrases are licensed as adjuncts within NPs and objects are licensed as complements of N. Thus, distribution and, to an extent, morphosyntax are given priority over internal syntax in their analysis: verbal internal syntax does not necessitate a verbal projection, largely because of the distributional facts (because the nominal distribution rules out a verbal projection when taken together with the nominal internal syntax at the base of the phrase).

Turning now to the type B masdar, Börjars et al. (Reference Börjars, Madkhali, Payne, Butt and King2015) propose that the same set of rules that license the type A masdar, together with general rules of noun phrase formation (such as adjectival modification), license the type B masdar, which is, under their analysis, fully nominal just like the type A masdar:

While Börjars et al.’s proposal provides a categorially uniform, and thus in certain respects attractive, analysis of the Arabic masdar, it suffers from both theoretical and empirical weaknesses. On the empirical side, the rules provided by Börjars et al. (Reference Börjars, Madkhali, Payne, Butt and King2015), and illustrated in the trees above, fail to capture an important constraint on the type B masdar: adjectival modifiers must appear closer to the head than adverbial modifiers. Börjars et al. (Reference Börjars, Madkhali, Payne, Butt and King2015) treat both adjectival and adverbial modifications by means of adjunction inside NP, so they cannot constrain the order of such adjuncts structurally.

Moreover, the crucial structural restriction distinguishing the type A and type B masdars is not accounted for under Börjars et al.’s proposal: adjectives and objects may not appear within the same masdar phrase. The type A masdar may have objects but not adjectives, while type B may have adjectives but not objects. This constraint is not accounted for structurally by Börjars et al.: in principle, any noun phrase may be modified by an adjective (or an adverb) or govern an object. Börjars et al. (Reference Börjars, Madkhali, Payne, Butt and King2015) assume that the restriction on adjectival modification can be enforced by the semantics: the semantic core of the type A masdar is inherently more propositional, making it inappropriate for modification by adjectives. But this does not in itself explain why objects are possible only with the more propositional type A, nor does the very reasonable suggestion that there is a semantic angle to the restriction necessarily eliminate the advantage of providing a syntactic account.Footnote [18]

On a more theoretical level, if we eliminate internal syntax as a criterion for distinguishing between categories, we run into the problem of how to capture the usual internal syntactic distinctions between categories. For example, the fact that the vast majority of noun phrases cannot govern structural objects and cannot be modified by adverbs can no longer be accounted for structurally. Rather, Börjars et al. (Reference Börjars, Madkhali, Payne, Butt and King2015) assume that subcategorization and/or semantics will effect the constraints (for example, adverbs are only semantically appropriate as modifiers of words with an event argument). While theoretically possible, the huge proliferation of ungrammatical phrase structures licensed by Börjars et al.’s proposal, such that any noun could appear with a structural object and adverb modifier (until ruled out by functional/semantic considerations), runs counter to the principle, discussed above, that it is better to rule out impossible structures in the context-free phrase-structure component of the grammar.

For a plausible analysis of the Arabic masdar, we cannot maintain that internal syntax, distribution and morphosyntax are all independently sufficient for categorization. Since the rejection of internal syntax as a criterion, as proposed by Börjars et al. (Reference Börjars, Madkhali, Payne, Butt and King2015), does not lead to an adequate analysis, it is necessary to seek an alternative. Let us assume that internal syntax is crucial to categorization. We will therefore assume that the phrase-structure rules distinguish different categories in terms of the types of specifiers, complements and adjuncts that they admit. So I assume standard phrase-structure rules for noun phrases which license determiners, adjectival modification, but not (general) adverbial modification or object complements, whereas the standard phrase-structure rules for verb phrases license/exclude the converse.

The internal syntax of the construct state suggests that the base of the masdar phrase is nominal, and the nominal morphosyntax of the masdar supports this. The evidence for verbal internal syntax, that is, the possibility of an object phrase with the type A masdar and the possibility of adverbial modification with both types, requires also a verbal projection dominating the nominal projection. Given that we do not want a further nominal projection on top of this, we can have no more structure than this: the masdar phrase is a mixed projection, NP at the bottom, VP at the top. That is, I propose the following in place of (17):

The internal structure of this phrase fits the data, and standard LFG phrase-structure assumptions, perfectly. The adverbial modifier is an adjunct within the verbal projection. The object phrase is a sister to the position which would be the lexical head of the VP, if it were not empty; to this same (null) position, the embedded NP co-head phrase is a sister, just as expected for a co-head phrase.

The only unusual aspect of this analysis is the category of the top node. The distribution of the masdar phrase is nominal, yet this phrase is a VP. The necessary conclusion, then, is that if internal syntax is crucial to categorization, distribution cannot be crucial to categorization. We are left, then, with an analysis which requires a subset of VPs (those headed by masdars) to have the distribution of noun phrases.

Ordinarily, perhaps, distributional identity is correlated with categorial identity, which explains the widespread sense that distribution is a useful criterion for categorization. However, in a constraint-based framework, there is no reason why this should necessarily be the case. As discussed, for example, by Pollard (Reference Pollard1996), it is important to draw a conceptual distinction between the means used to capture syntactic generalizations (such as phrase-structure rules and functional descriptions) in a grammar and the syntactic structures licensed by that grammar.Footnote [19] The grammar consists fundamentally of a set of constraints; the constraints are the crucial element, not the resulting structures. Grammatical structures are required to satisfy the constraints, but there is no requirement that any structure should necessarily visibly reflect every constraint that it satisfies.

In LFG, the phrase-structure tree (the c-structure) is one part of the syntactic structure licensed by the grammar, the part which models surface phrasal constituency. The primary means for capturing syntactic generalizations are the phrase-structure rules. Only to the extent that the c-structure directly reflects the generalizations made in the phrase-structure rules does the c-structure itself represent those generalizations, and there is no requirement that any one rule should be directly reflected in the c-structure. In fact, the LFG formalism specifically licenses a distinction between phrase-structure rules and associated phrase-structure trees, in the form of metacategories and phantom nodes (Dalrymple Reference Dalrymple2001: 94–95). It is the concept of metacategories which are of relevance here. The most obvious use of a metacategory is to generalize over more than one category which can appear in the same position. For example, English verbs like consider can take predicative complements of at least four different categories:

All four structures can be accounted for using the same phrase-structure rule (22), granted the metacategory definition in (21).

A metacategory definition serves to capture syntactic generalizations just as an ordinary phrase-structure rule does, but the difference is that the metacategory definition does not result in a corresponding representation in the phrase-structure tree.Footnote

[20]

The situation with the Arabic masdar, under the analysis proposed here, is equivalent: masdars share their distribution with noun phrases but are not noun phrases themselves. If we use a complex category

![]() $\text{V}_{[\text{msd}]}$

to distinguish masdar VPs from finite VPs, we can capture the identity of distribution between NPs and masdar VPs unproblematically using a metacategory:

$\text{V}_{[\text{msd}]}$

to distinguish masdar VPs from finite VPs, we can capture the identity of distribution between NPs and masdar VPs unproblematically using a metacategory:

This constraint enables the identity of distribution between masdar VPs and noun phrases to be captured in the PS rules, just as well as it could under an analysis in which the masdar phrase was an NP at its head, but with the additional advantage that it does not require the masdar phrase itself to be an NP at its head, a requirement which we have seen leads to analytical difficulties.

As discussed above, the proposal of Börjars et al. (Reference Börjars, Madkhali, Payne, Butt and King2015) suffers from two empirical weaknesses: it provides no account of the constraint that adjectival modifiers must appear closer to the head than adverbial modifiers and it provides no account of the fact that objects and adjectival modifiers may not co-occur in the same phrase. Under the analysis proposed here, the first constraint follows unproblematically. AdvP adjuncts are licensed within VP, while AdjP adjuncts are licensed within NP, meaning that the latter are necessarily closer to the head than the former. The type B masdar (15), which permits both adjectival and adverbial modification, must therefore also be a mixed projection, with the same VP-over-NP structure as the type A masdar:

Once again, the structure of this phrase fits standard phrase-structure assumptions. The oblique complement is sister to the empty verbal head, as is the co-head NP. The adjectival modifier occurs within the NP, which means it necessarily precedes the adverbial modifier within VP. Once again, the nominal distribution of this VP must be captured in the phrase-structure rules; the same constraint (23) which captures the distribution of the type A masdar applies equally to type B.

In fact, just as assumed by Börjars et al. (Reference Börjars, Madkhali, Payne, Butt and King2015), there is no need to treat the type A and type B masdars as differing in any way at the level of phrase structure. The superficial difference between them, that type A may have an object and may not be modified by adjectives, while type B may be modified by adjectives but may not have an object, can be captured by a co-occurrence constraint preventing adjectives and objects from appearing together in the same phrase. Under Börjars et al.’s approach, there is no way to model the constraint in the syntax, hence, their relegation of the phenomenon to the semantics. Under the analysis proposed here, however, this constraint can be captured with relative ease: objects must occur closer to the head than adjuncts. Since in the structures proposed above ((19) and (24)) objects can only occur within the verbal part of the projection and AdjP adjuncts only within the nominal part, if an object and an adjective were to co-occur, the adjective would necessarily occur closer to the head than the object. The proposed constraint, which rules out such a structure, correlates with the semantics: objects are core arguments, more central to the meaning of a predicate, and hence more naturally appear closer to the head, in structural terms, than an adjunct.Footnote [21]

Thus, the mixed projection analysis proposed here, which takes internal syntax as of primary importance for categorization, provides a more thorough account of the Arabic masdar data than the proposal of Börjars et al. (Reference Börjars, Madkhali, Payne, Butt and King2015), which downplays the evidence of internal syntax for categorization, depending rather on distributional and morphosyntactic criteria.

4 The English gerund

The evidence of the Arabic masdar shows that it is not possible for all three criteria in (2) to be independently sufficient for categorization. My proposed analysis of the Arabic masdar takes internal syntax to be crucial for categorization, with the consequence that distribution is not a sufficient criterion for categorization. Distribution has been taken as a sufficient criterion in work on other mixed categories, including the English gerund in -ing. In this section, I show what the consequences of my proposals are for the analysis of the English gerund.

4.1 Introduction

The standard LFG approach to mixed projections was developed by Bresnan (Reference Bresnan, Butt and King1997, Reference Bresnan2001: 289–296) and Bresnan & Mugane (Reference Bresnan, Mugane, Butt, Dalrymple and King2006), who discuss the English gerund in -ing, undoubtedly the most commonly discussed mixed projection.Footnote [22] In fact, the English gerund is a particularly complicated example because there are three different phrasal configurations in which the gerund may appear. The English gerund can display entirely nominal, entirely verbal or ‘mixed’ phrasal structure:

I refer to these as types A, B and C, respectively. In all these examples, the gerund heads a phrase which functions as a subject of the sentence. In type A (25a), the syntax of the phrase headed by missing is entirely nominal: the semantic object of missing appears as a prepositional complement, as is standard for complements of nouns; missing is premodified by an adjective, as only nouns can be; the phrase also contains a possessor phrase, a possibility only found within nominal projections. Although the form missing is derived from the verb miss, the exclusively nominal syntax of the phrase means that missing here can be unambiguously analysed as a noun, that is, of category N, heading an entirely unremarkable NP.Footnote [23]

The type A gerund type seen in (25a) is therefore not a mixed projection and will not be considered further. In contrast, the syntax of the phrase headed by missing in (25b) is entirely verbal: the semantic object appears in the same form as an object of a finite verb, that is, ‘bare’ (not embedded under a preposition); the semantic subject likewise appears in the ‘bare’ form, with oblique/accusative ‘case’; the modifier is an adverb. I call this type B; it is commonly referred to as the “Acc-ing” construction. This type will be discussed below where I argue, contrary to standard analyses, that it is not a mixed projection.

The unambiguously ‘mixed’ construction is type C (commonly referred to as the ‘Poss-ing’ construction), exemplified in (25c = 1): the internal syntax of the phrase headed by the gerund is mixed, in that the phrase contains elements which are specific to DPs in English (possessive modifier) and elements which are specific to VPs in English (object and adverb modifier); the distribution of the phrase is at least superficially nominal since it can function as a subject (as in the example provided), object or other grammatical function or, indeed, can appear in any of the positions in a clause that an ordinary noun phrase can; in terms of morphology, the type C gerund in -ing cannot show plural marking (*their missings the penalties vs. type A their missings of the penalties) and does show the same kind of tense/aspect distinctions as finite verb sequences (cf. his having missed the penalty…), which suggests closer affinities with the verbal system than the nominal system. The analysis proposed by Bresnan et al. (Reference Bresnan, Asudeh, Toivonen and Wechsler2016: 311–319) was given in (5) and is repeated in (27).

4.2 Distribution and the type B gerund

As discussed above, I take internal syntax to be crucial to categorization. Therefore, the fact that the type C gerund shows both nominal and verbal internal syntax means that it must be treated as a mixed projection, just like the Arabic masdar. I therefore accept Bresnan et al.’s analysis (27) for the type C gerund.

On the other hand, the type B gerund is consistently verbal in terms of its internal syntax as well as sharing the same verbal morphosyntactic properties as the type C gerund. The following table compares the relevant properties of the Arabic masdar and the type B and type C gerunds:

The type C gerund shows two distinct types of property ‘mixing’: first, the three criteria in (2) point in different directions, for example, distribution points towards nominal status and morphosyntax points towards verbal status; second, the criterion of internal syntax itself points in more than one direction. In this way, the type C gerund is similar to the Arabic masdar, the only difference being that with the former, the evidence points to NP-over-VP, while with the latter, the evidence points to VP-over-NP. In contrast to these constructions, the type B English gerund construction (25b) is more consistently verbal: it is morphologically verbal in exactly the same way as the type B gerund, and its internal syntax is purely verbal. Its only potentially nonverbal property is its distribution: it shows the same apparently nominal distribution as the type C gerund. Despite these differences, Bresnan et al. (Reference Bresnan, Asudeh, Toivonen and Wechsler2016: 318) treat the type B gerund via the same kind of head-sharing analysis as the type C construction (25c), the only difference being the category of the co-head phrase:

As with (5), the gerund appears in the head of a VP, with object complement like any transitive V, but in this case, the VP and accusative case subject phrase him together constitute a clausal phrase S, which serves as co-head complement of (absent) D in the higher DP. Thus, the phrase as a whole is a DP, headed by a V in an embedded VP, just as in (5). It is clear that the DP node and, therefore, the mixed projection analysis altogether depends entirely on the assumption that nominal distribution is sufficient evidence for a nominal projection in the phrase structure.

The S node in (29) is an exocentric category, often utilized within LFG for phrases containing a verb (phrase) and the verb’s subject. Thus, the analysis shown in (29) involves two instances of exocentricity: the exocentricity of S and the exocentricity of the extended head structure. The use of S is not strictly relevant for the present discussion, and it could be eliminated by licensing the subject phrase in SpecVP and thus having simply a VP complement of D. Under Bresnan et al.’s proposal, the S node is required only if there is an accusative case subject; if there is no subject, there is simply a VP with DP as extended head (ambiguous between the (25b) and (25c) types). Bresnan et al. (Reference Bresnan, Asudeh, Toivonen and Wechsler2016: 318) derive the S-less structure by Economy of Expression, a derivational process which effectively ‘prunes’ unnecessary nodes from trees. Given the rejection of Economy of Expression by Dalrymple, Kaplan & King (Reference Dalrymple, Kaplan and King2015), it is preferable to follow Seiss (Reference Seiss, Butt and King2008) in assuming that the daughter of DP in the type B gerund is consistently a VP, with the subject phrase appearing in SpecVP as in (30).

Nevertheless, the category of the verbal node is not the crucial point here. What matters is the top DP node: the internal syntax of the phrase is entirely verbal (or clausal): there can be no adjectival modifier, determiner or possessor phrase. Given that there are no explicit morphological properties of the gerund that require a DP node, it is clear that the DP node is assumed purely to account for the distribution of the phrase, that is, distribution is taken as a sufficient criterion for postulating a syntactic category.

There exist a number of similar proposals for mixed projection analyses that take distribution as a sufficient criterion for categorization. For example, as discussed in more detail below, Bresnan (Reference Bresnan, Butt and King1997) and Spencer (Reference Spencer, Butt and King2015) propose that attributive participle clauses, which show the internal syntax of a VP but the distribution and agreement features of an Adj, are best analysed via a mixed projection in which a VP functions as a complement to AdjP. Similarly, Haug & Nikitina (Reference Haug and Nikitina2016: 15) assume a head-sharing construction for a participle construction in Latin (the ‘dominant’ participle construction) which shows the external syntactic distribution of a noun but whose internal syntactic structure is that of an S.Footnote [24] Since Latin lacks a DP, they assume an S as a co-head complement of an NP:

The NP projection above S in (32) might predict that the phrase itself could contain nominal syntactic structure, but this is not the case. The dominant participle phrase as a whole, that is, what Nikitina & Haug (Reference Nikitina and Haug2016) and Haug & Nikitina (Reference Haug and Nikitina2016) demonstrate is an S, cannot be modified by an adjective, for example. Again, the only justification for the NP projection above S is the distribution of the phrase.

Distribution alone, then, is taken as sufficient evidence for categorization within LFG work on mixed projections. But as I have shown above, this assumption cannot be maintained in the case of the Arabic masdar. In that case, it appeared preferable to disregard the evidence of distribution, which can be accounted by other means, in favour of internal syntax as the primary criterion for categorization. The same argument can, in fact, be made for the English type B gerund.

A number of authors, including Abney (Reference Abney1987) and recently Pires (Reference Pires2007: 167–168), note certain differences between the type B and type C gerunds which bring into question the assumption that both involve a nominal projection at the top level. Specifically, the type B gerund shares certain properties with finite clauses which are not found with the type C gerund (poss-ing). For example, the type B gerund is compatible with wh-extraction, expletive subjects and certain adverbs, which are not possible with the type C gerund (examples from Pires Reference Pires2007):

Gerunds without an overt subject, which are superficially ambiguous between type B and type C, pattern with type B in all cases where the difference is not neutralized. None of this data can be accounted for under the proposals of Bresnan et al. (Reference Bresnan, Asudeh, Toivonen and Wechsler2016), according to which both types are mixed projections with the same top node. However, if we abandon the assumption that nominal distribution is sufficient evidence to require a nominal projection, it is possible to treat the type B gerund (including gerunds without overt subjects) as a purely verbal projection. Then the fact that the type C gerund is less clause-like than the type B gerund can follow from the fact that type C, but not type B, is at the top level a nominal projection. That is, instead of (30), I propose the following for the type B gerund:

Differences of theory aside, this is similar to the proposal of Pires (Reference Pires2001, Reference Pires2006, Reference Pires2007), according to which the type B gerund (his ‘clausal gerunds’) projects to a TP at the top level. What remains to be accounted for, under this proposal, is the identical distribution of gerunds and noun phrases. Under proposals where both type B and type C gerunds are mixed projections, nominal at the top level, their distribution falls out naturally. If this distribution is not accounted for by categorization, it must be accounted for in some other way. Within a minimalist framework, Pires (Reference Pires2007) assumes that the type B gerund, analysed as a TP, has the distribution of a noun phrase because it is assigned a case feature which requires checking.

A similar approach could be taken within the LFG framework adopted here; for example, type B gerunds could be lexically associated with a specification requiring the presence of a case feature at f-structure, which could only be supplied if the gerund phrase occurred in a relevant argument position. However, such an approach would not generalize to the analysis of participial clauses, discussed in the next section, which I analyse as verb phrases which share their distribution with adjectival and other modifying phrases.

I therefore adopt the same analysis proposed for the Arabic masdar above: if we distinguish the grammar, as a set of constraints on structures, from the structures themselves, then it is unproblematic to capture the identical distribution of type B gerund and noun phrases, by defining a metacategory which ranges over both phrase types, for example:

This constraint captures the nominal distribution of the type B gerund just as well as a mixed projection analysis involving a DP node, but has the advantage that it does not require that DP node to appear in the structure itself, accounting for the differences between the types B and C gerunds mentioned above. If both types have the same mixed projection structure, then these differences cannot easily be accounted for, but if the former is a mixed, partially nominal projection, while the latter is a purely verbal projection, the differences fall out naturally.

Of course, a set of phrase-structure rules which accurately models the distribution of noun phrases and gerunds is likely to require more than one metacategory which generalizes over these two types of phrase and one or more other phrase types. For example, one of the possible positions in which DPs and gerunds may appear, the subject position SpecIP, may also host phrases of other lexical categories, including APs, PPs and CPs:

Examples (36b, d, f) show that the position of the relevant phrases in (36a, c, e) is SpecIP, rather than a position further to the left.Footnote

[25]

Thus, the phrase-structure rule which makes generalizations over the SpecIP position will most appropriately be stated using a metacategory which ranges over at least the categories DP, AP, PP, CP and

![]() $\text{VP}_{[\text{ger}]}$

. In contrast, the phrase-structure rule which makes generalizations over the core direct object position (first complement of V) will most appropriately be stated using a metacategory which ranges over DP, CP and

$\text{VP}_{[\text{ger}]}$

. In contrast, the phrase-structure rule which makes generalizations over the core direct object position (first complement of V) will most appropriately be stated using a metacategory which ranges over DP, CP and

![]() $\text{VP}_{[\text{ger}]}$

but not AP and PP.Footnote

[26]

$\text{VP}_{[\text{ger}]}$

but not AP and PP.Footnote

[26]

Thus, metacategory definitions have considerable use in grammar to model restrictions on phrase types in different positions, and, therefore, their use for mixed projections does not constitute an additional complication.

Besides the empirical evidence in favour of a structural distinction between type B and type C gerunds, there is also a theoretical argument. I argued above that exocentricity can be analysed as a marked possibility, cross-linguistically, which may be understood in terms of constraints which, all else being equal, rule out exocentric structures, including mixed projections.Footnote [27] Therefore, a grammar which necessitates fewer exocentric structures may be preferred, all else being equal. As there is no evidence specifically favouring the mixed (and therefore exocentric) analysis of the type B gerund, it seems fair to conclude that all else is equal and that the exocentric, mixed projection analysis of the type B gerund is to be dispreferred. This claim extends well beyond the analysis of the English gerund, of course. It entails that in all instances in which there is a difference between the distribution and the internal syntax of a particular phrase type, it is better not to analyse this in terms of a mixed projection, but rather assume an endocentric, internally consistent projection for the phrase itself, and to account for its distribution by other means.

To summarize my proposals for the English gerund, then: first, the type C gerund (poss-ing) is a true mixed projection, as evidenced by its mixed internal syntax. This can be modelled in LFG by means of a head-sharing structure, as proposed by Bresnan (Reference Bresnan, Butt and King1997) and shown in (37).

Second, the type B gerunds, under which heading I include both structures with an ‘accusative’ case subject (acc-ing) and those with no explicit subject, are not mixed projections, but pure verbal projections which share their distribution with that of noun phrases. They are formed like any other verb phrase, with the exception of the VP-internal subject, which is lexically licensed by the gerund form of the verb.

As a full illustration, I give the relevant phrase-structure rule, metacategory definition, lexical entry and c-structure/f-structure representation for the sentence in (25b).

5 Attributive participles

The evidence of the Arabic masdar suggested that distribution is neither a sufficient nor a necessary criterion for syntactic categorization, whereas internal syntax is crucial for categorization. The evidence of the English gerund supports this, insofar as an analysis in which the type B gerund is not a mixed projection fares better in accounting for the syntactic differences between type B and type C. The case of attributive participles is similar but also brings into question the importance of the third criterion for categorization given in (2), morphosyntactic properties.

5.1 Another mixed projection?

Spencer (Reference Spencer, Butt and King2015) discusses ‘Indo-European type’ participles in Sanskrit, as treated by Lowe (Reference Lowe2015), and also in Lithuanian, proposing an analysis that is, in many respects, the same as that proposed for German participles by Bresnan (Reference Bresnan, Butt and King1997: 2–3). All these participles are diachronically related and are of the same ‘subject-oriented’ type; that is, to the extent that an attributive participial clause can be treated as a reduced relative clause, it is necessarily the subject that is relativized on. The participle agrees with and attributively modifies a noun, which is identified with the gapped subject of the participial clause. Example (43) shows an attributive participle in Sanskrit, (44) one from Lithuanian and (45) one from German.

These participles can also have other uses. For example, as discussed by Lowe (Reference Lowe2015), Sanskrit participles can also be used predicatively, that is in ‘converbal’ or clausal adjunct use. The attributive use is the most canonically adjectival use of participles, but adjectives can also, to a slightly more limited extent, be used as clausal adjuncts; so in both uses, participles appear to display adjectival distribution. I focus on attributive participles here, following Spencer (Reference Spencer, Butt and King2015) and Bresnan (Reference Bresnan, Butt and King1997).

Morphologically, participles are mixed in the sense that they combine a verbal stem with an adjectival suffix. Distributionally, they are at least superficially most similar to adjectives. However, the internal syntax of the participle phrase is exclusively verbal. Participles to transitive verbal stems may take objects, in the same case as, and entirely indistinguishable from, the object of a corresponding finite verb form; accusative case objects appear in (43) and (45). Likewise, participles may be modified by adverbs but never by adjectives. Considering the three criteria defined in (2), the English type B gerund is purely verbal in respect of two of the three criteria, while attributive participles are purely verbal only in relation to one of the three:

Spencer (Reference Spencer, Butt and King2015) assumes that the adjectival distribution and mixed morphosyntactic properties of attributive participles justify a mixed projection analysis. Spencer notes that this could be formalized by means of the standard head-sharing approach seen with the type C English gerund above (i.e. in this case, a VP embedded within an AdjP), but he proposes an alternative, intermediate category analysis. Spencer (Reference Spencer, Butt and King2015) adopts the morphological model of Spencer (Reference Spencer2013), adapted to LFG, involving a semantic argument structure representation in the morphology of a word which maps to c-structure and f-structure and (among other things) determines the category of the word. The argument structure of a verb has an event semantic function (SF) role ev, while adjectives have a modifier SF role a-mod. The morphological process that derives (or inflects) a participle from a verb creates a composite SF role ![]() This composite SF role projects to c-structure and f-structure in such a way that participles display both adjectival and verbal morphosyntax. In terms of syntactic category, Spencer (Reference Spencer, Butt and King2015) proposes that the composite SF role maps to an intermediate category, which he labels ‘V2A’ (for ‘verb-to-adjective transposition’).

This composite SF role projects to c-structure and f-structure in such a way that participles display both adjectival and verbal morphosyntax. In terms of syntactic category, Spencer (Reference Spencer, Butt and King2015) proposes that the composite SF role maps to an intermediate category, which he labels ‘V2A’ (for ‘verb-to-adjective transposition’).