1. Introduction

Based on data from BasaáFootnote 2 (Bantu), I discuss a relatively new topic in the morphosyntax of nominal constructions of African languages, which has however been addressed across various language families, as can be observed in (1a) for Warlpiri (Autralian), (1b) for German (Indo-European) and in (1c) for Japanese (Asian), among others.

The commonly used names for this construction include split topicalization (van Riemsdijk Reference van Riemsdijk and Benincà1989; van Hoof Reference van Hoof, Everaert and van Riemsdijk2006; Ott Reference Ott2011, Reference Ott2012, Reference Ott2015a), discontinuous noun phrases (Mchombo, Morimoto & Féry Reference Mchombo, Morimoto, Féry, Butt and King2005, Fanselow & Féry Reference Fanselow and Féry2006, Mchombo Reference Mchombo2006, Féry, Fanselow & Paslawska Reference Féry, Schwabe and Winkler2007, Cardoso Reference Cardoso, Martins and Cardoso2018), (XP-)split constructions (Fanselow & Ćavar Reference Fanselow, Ćavar and Alexiadou2002). In the constructions in (1), the head noun in boldface occurs in sentence-initial position and seems to have been separated from its modifier in boldface inside the clause.

The same phenomenon has been reported in some Bantu languages as illustrated in (2a) for Kiitharaka (Fanselow & Féry Reference Fanselow and Féry2006: 47) and (2b) for Chichewa (Mchombo Reference Mchombo2006: 151). See also Mchombo et al. (Reference Mchombo, Morimoto, Féry, Butt and King2005) for Chichewa.

In (2), the head noun in these two Bantu languages is allowed to occur in sentence-initial position while its modifer occurs inside the clause. Though Fanselow & Féry (Reference Fanselow and Féry2006: 47) mention the presence of this construction in other Niger-Congo languages, no illustration is provided in their work, unfortunately. In fact, only little attention has been paid to this phenomenon in African languages. The main goal of this paper is to bridge this gap by proposing a comprehensive analysis of this morphosyntactic phenomenon in Basaá, with a special accent focalization, topicalization, relativization and wh-questions, as shown, respectively, in (3). Note that the relative marker is optional, as indicated by parentheses.

One might assume that (4) represents the unmarked order, in which the head noun mámbɔ́t ‘clothes’ is modified by a quality adjective, a numeral and an indefinite on its right:

Following this assumption, the constructions in (3a)–(3c) show that (4) can change so that the string of words mambɔ́t malâm másámal ‘six nice clothes’ in sentence-initial position seems to have been detached from the postverbal modifier mápɛ́ ‘other’. The same observation holds for the distribution of the quantifier phrase mámbɛ̂ mámbɔ́t ‘which clothes’ and the postverbal indefinite mápɛ́ ‘other’ in the interrogative sentence in (3d).

After discussing the morphosyntax of these constructions and their semantic/pragmatic properties, I will provide evidence that the sentences in (3) are by no means derived from (4), despite appearances. I propose an approach in which the chunk of words in clause-initial position and the postverbal stranded modifier are underlyingly merged as two independent and symmetric DPs in a subject–predicate relation within a small clause (Moro Reference Moro1997, Reference Moro2000) complement of a lexically overt/covert verb. The surface word order is obtained by raising the subject of predication into some higher position under closest c-command for feature-checking, labelling and asymetrization purposes, except for topic fronting constructions. In this latter case, it is suggested that the topicalized constituent is not derived in a monoclausal structure, but a series of two parallel clauses, such that after clausal ellipsis of the first clause, the remnant (i.e. the topic) seems to stand in a structural discontinuity with its correlate found inside the juxtaposed clause, which is fully pronounced at PF (see Ott Reference Ott2015b). The advantage of this approach is that it nicely accounts for case marking and theta-role assignment, as well as for the absence of island and connectivity effects in topicalization. In short, split DPs under topicalization do not involve a small clause, while other split constructions do. In the latter, subject raising takes place under closest c-command between a probing head and the subject of predication (goal), following Chomsky (Reference Chomsky, Martin, Michaels and Uriagereka2000, Reference Chomsky and Kenstowicz2001), as a way to obtain an asymmetric syntactic structure and for the purpose of labelling. In Basaá, subject raising is preferred to predicate inversion (see e.g. Mathieu Reference Mathieu2004; Mathieu & Sitaridou Reference Mathieu, Sitaridou, Batllori, Hernanz, Picallo and Roca2005; Ott Reference Ott2011, Reference Ott2015a) because the subject is a full DP while the predicate is a reduced DP containing a null head modifier. The elided noun inside the reduced predicate is discourse-given and recoverable from the rich agreement morphology, as reflected on the stranded modifier.Footnote 3 Arguments in support of a small clause analysis derive from the various morphosyntactic and semantic/pragmatic mismatches between the continuous DP structure in (4) and their counterparts in (3). This approach capitalizes to a certain extent on previous works such as Mathieu (Reference Mathieu2004), Mathieu & Sitaridou (Reference Mathieu, Sitaridou, Batllori, Hernanz, Picallo and Roca2005), and Ott (Reference Ott2011, Reference Ott2012, Reference Ott2015a). However, the current implementation is not exactly similar to theirs. Throughout the paper, I will sometimes borrow from Ott’s analysis by using the term ‘symmetric’ noun phrases to refer to structures delineated in (3) with a sentence-initial DP and a DP-internal modifier inside the clause.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents some basic facts about word order, clause structure and nominal modification in Basaá. The analysis sheds light on postnominal and prenominal modification as well as noun/noun phrase (N/NP) ellipsis. Section 3 deals with the semantic/pragmatic mismatches between continuous noun phrases and split ones. These mismatches are discussed in focus, wh-question, relative clause and topic constructions. Section 3.6 presents the first interim conclusion. In Section 4, I address the syntactic properties of symmetric noun phrases, with a focus on island effects (Sections 4.1 and 4.2), the subject islands and oblique objects (Section 4.3), binding and reconstruction effects (Section 4.4), and noun class and number mismatches (Section 4.5). In Section 4.6, evidence is given, based on the DP hypothesis and lexical degeneration, that the phenomenon under study does not involve subextraction. Section 4.7 is concerned with multiple fronting constructions and the impossibility of inverted structures. Section 4.8 presents an interim conclusion. Section 5 very briefly presents some competing approaches and Section 5.1 presents the proposal for the syntactic derivation of symmetric noun phrases as realized in Basaá. The last section is the conclusion.

2. Preliminaries: Word order and clause structure

This section provides some basic facts about clause structure and word order within the nominal construction in Basaá. Basaá is a Narrow Bantu language spoken in Cameroon by about 300,000 speakers (Lewis, Simons & Fennig Reference Lewis, Simons and Fennig2018). The data explored in this paper are from the Mbene dialect as spoken in the Sanaga Maritime administrative division.

2.1. Basic clause structure

Basaá is a noun class language with a basic SVO word order (5a) and a rich morphological agreement system. It also allows pro-drop (5b).

2.2. Nominal modification and morphosyntactic agreement

As expected from a noun class Bantu language, modifiers of the noun agree in class and number with the head noun within the noun phrase. This morphosyntactic agreement is subject to some constraints in Basaá as will be seen in the following sections.

2.2.1. Postnominal modification

Recent works on nominal modification in the language include Makasso (Reference Makasso2010), Hyman, Jenks & Makasso (Reference Hyman, Jenks, Makasso, Orie and Sanders2013) and Jenks, Makasso & Hyman (Reference Jenks, Makasso, Hyman, Atindogbé and Grollemund2017). As illustrated in (6), postnominal modifiers agree with the head noun (here malaŋ ‘onions’) in class (class 6) and number (plural). No agreement is attested here with the prenominal definiteness markerFootnote 4 í, in (6a).

In fact, the prenominal definiteness marker always bears a high tone [ ́ ] and is invariable in Basaá. Put differently, the definiteness marker í is not gender-sensitive like postnominal modifiers. It always co-occurs with a postnominal demonstrative. When used in a nominal construction, the definiteness marker í indicates that the following head noun encodes definiteness or specificity. When the definiteness marker is dropped, as in (6b), its high tone spreads onto the first syllable of the following head noun ((5a) vs. (5b)). Sentences (6a) and (6b) can also be translated as ‘These specific six nice onions of mine’ and constitute felicitous fragment answers to ‘What did you sell?’.

One important thing about postnominal modifiers is that their ordering is not highly constrained. However, whenever a postnominal demonstrative and a possessive co-coccur in the same noun phrase, the former should follow the latter as in (6) and (7).

In short, a possessive never follows a demonstrative in the postnominalFootnote 5 position. A noun phrase in which the possessive follows the demonstrative is ruled out (see (8a)). This ordering constraint does not hold for the distribution of the demonstrative, qualifying adjectives and numerals.Footnote 6 As shown in (8b) and (8c), when the possessive is dropped, the ordering between the demonstrative and other modifiers is flexible.

Although all the grammatical noun phrases in (6)–(8) can be literally translated into English as ‘these six nice onions of mine’, it is worth mentioning that they do not have the same interpretation. The word order flexibility in postnominal modification phrase is linked to the predicative nature of modifiers in the sense that each modifier can function as a predicate, giving rise to a kind of successive complex predication. For instance, in the ordering [… [N–Adj] Poss] Num] Dem] delineated in (7a), the adjective is predicated to the head noun, forming the sequence [… [N–Adj]]. Then the possessive is merged as the predicate of the sequence [… [N–Adj]] forming [… [N–Adj] Poss]. Predicating the numeral to the complex [… [N–Adj] Poss] yields the sequence [… [N–Adj] Poss] Num]]. The final step consists in predicating the demonstrative to the complex [… [N–Adj] Poss] Num]] to form [… [N–Adj] Poss] Num] Dem]].

2.2.2. Prenominal modification

However, premodification is restricted to a certain class of modifiers. While a postnominal demonstrative in (6a) and (6b) is associated with a definite or specific reading on the head noun, its prenominal counterpart in (9a) encodes a contrastive interpretation (see also Hyman Reference Hyman, Nurse and Philippson2003, Hyman et al. Reference Hyman, Jenks, Makasso, Orie and Sanders2013, Jenks et al. Reference Jenks, Makasso, Hyman, Atindogbé and Grollemund2017). Thus, the noun phrase in (9a) can be used as a correction to the statement ‘she bought those six nice onions of mine’, where a near speaker demonstrative ‘these’ contrasts with a far speaker demonstrative ‘those’. A prenominal demonstrative can never co-occur with the definiteness marker í, as shown by the ungrammaticality of (9b) and (9c).

Simple numerals are disallowed in the prenominal position (see (10a) below), while a possessive can occur prenominally along with other postnominal modifiers, as illustrated in (10b). Just like a prenominal demonstrative, a prenominal possessive conveys a contrastive interpretation. It may be preceded by the definiteness marker í. As shown in (8a), postnominally a demonstrative is not allowed to precede a possessive modifier. However, prenominally a demonstrative may precede or follow a possessive: both (10c) and (10d) are grammatical, with a contrastive interpretation on the two modifiers.

In (10d), the definiteness marker í optionally precedes a possessive. Note that a preposed demonstrative and the definiteness marker are incompatible only when they are adjacent, as shown in (9b) and (9c). But if a possessive intervenes between the two, there is no illicitness as shown in (10d). Qualifying adjectives may also occur prenominally. A prenominal adjective, as seen in (11) below, is associated with a focus interpretation (marked by underlining in the English translation). Instead of undergoing agreement with the head noun, as is the case with its postnominal counterpart, a prenominal adjective (in bold) is, rather, the element that controls agreement on all the elements inside the noun phrase, with the exception of the noun (in italics).

According to Hyman et al. (Reference Hyman, Jenks, Makasso, Orie and Sanders2013), prenominal adjectives are nominal adjectives because they act as nominal heads. Thus they bear a fully-fledged noun class prefix, just like bona fide nouns in the language, and control agreement on all the modifiers inside the noun phrase structure. In (11a) for instance, the prenominal ɓalâm ‘nice’ bears the prefix ɓa which encodes class 2. It also controls agreement on the linking morpheme ɓá, the postnominal possessive ɓɛ̂m ‘my’, the demonstrative ɓáná ‘these’ and the numeral ɓásámal ‘six’. Only the noun málaŋ ‘onions’ evades this agreement. Nominal structures with a prenominal adjective behave like nominal compounds (see Hyman et al. Reference Hyman, Jenks, Makasso, Orie and Sanders2013 for more detail). Similarly, in (11b) the subject marker ɓá, which encodes subject–verb agreement, agrees not with the noun málaŋ ‘onions’, but with the prenominal adjective ɓalâm ‘nice’. The agreement patterns are supported by the incompatibility of the agreeing prefix ma, which agrees not with the prenominal adjective ɓalâm ‘nice’, but with the noun malaŋ ‘onions’. Should a prenominal demonstrative or possessive modifier be introduced in the noun phrase, agreement will still be controlled by the nominal adjective and not the noun. Consider the agreement patterns in (12) and (13) below, between postnominal adjectives in the (a) sentences and prenominal adjectives (boldface) in the (b) ones. The noun bíkaat ‘books’ is in bold in the (a) and italicized in the (b) sentences.

By virtue of being the head of the subject bíní bíkaat bilâm gwɛ̂m ‘these nice books of mine’ in (12a), the noun bikaat ‘books’ controls agreement not only on the prenominal demonstrative bíní ‘these’ but also on the postnominal adjective bilâm ‘nice’, the possessive gwɛ̂m ‘my’ and the numeral bítân ‘five’. Likewise, subject–verb agreement, as encoded by the subject marker bí, is controlled by the head noun bikaat ‘books’. In (12b), where the adjective ɓalâm ‘nice’ is prenominal, it is marked with different morphology and becomes the controller of agreement inside the noun phrase and inside the whole sentence. The same holds for the prenominal possessive construction in (13).

These interesting agreement patterns seem to support Hyman et al.’s (Reference Hyman, Jenks, Makasso, Orie and Sanders2013) proposal that nominal adjectives are nominal heads because they seem to behave like bona fide nouns (see Hyman et al. Reference Hyman, Jenks, Makasso, Orie and Sanders2013 for more detail).

2.2.3. Noun/noun phrase ellipsis and the ability to stand alone

One interesting property of nominal modification in Basaá, which is the core of the current discussion, is that modifiers of the head noun can stand in isolation in certain discourse contexts. Specifically, when the head noun is given or salient contextually, it can be elided, leaving its modifiers stranded. That N/NP ellipsis is possible in Basaá is supported by the following coordination and question–answer tests.

In (14a), where the head noun bikaat ‘books’ can be elided, the DP constituent bíkaat bilâm ‘nice books’ can be coordinated with the stranded adjective bībɛ́ ‘unpleasant’ without any resulting ungrammaticality. Sentence (14b) shows that a stranded adjective can be used as a fragment answer. Similarly, the fact that the size adjective mákɛ́ŋí ‘big’ in (15b) can stand alone as a correction to the DP mátówa matítígí ‘small cars’ shows that a nominal modifier can stand alone, contra Hyman et al.’s (Reference Hyman, Jenks, Makasso, Orie and Sanders2013: 161) prediction.

Noun/noun phrase ellipsis is not restricted to adjectives. It is possible for possessive and demonstrative modifiers to be used as sentence fragments as well. This is illustrated in (16)–(17).

Interrogative, numeral as well as colour adjective modifiers can also stand alone in the context of N/NP ellipsis, as shown in (18)–(20).

It could be hypothesized from these facts that there is a strong connection between the availability of morphological richness and N/NP ellipsis in Basaá. In fact, modifiers of the noun share the same phi-features, namely class and number information with the head noun. It is this strong morphological agreement that licenses N/NP ellipsis. For example, the omission of the head noun bitámb ‘shoes’ in (18) and (20) is linked to morphological richness as reflected on the stranded interrogative (18) and colour adjective (20) modifiers. These two modifiers bear the same morphological features as the head noun bitámb ‘shoes’. These features include class (class 8) and number (singular) information as reflected in the class prefix bi. Basaá is therefore a null head modifier language in the sense of Androutsopoulou (Reference Androutsopoulou, Lyle and Webster1997), Devine & Stephens (Reference Devine and Stephens2000), Mathieu (Reference Mathieu2004) and Mathieu & Sitaridou (Reference Mathieu, Sitaridou, Batllori, Hernanz, Picallo and Roca2005), because modifiers of the noun are allowed to strand without any support of an overt noun.

In conclusion, the availability of N/NP ellipsisFootnote 7 in Basaá is related to the salience of the elided noun in the discourse and the morphological richness of the stranded modifier associated with it. In what follows, I build on these elliptical constructions to claim that nominal structures with stranded nominal modifiers are reduced DPs, the noun/NP of which is subject to ellipsis.

3. The semantics/pragmatics of symmetric noun phrases

This section examines the different discourse conditions in which symmetric noun phrases arise in Basaá. As has been established cross-linguistically, these constructions are used only in specific discourse contextsFootnote 8 such as passivization, wh-questions (Obenauer Reference Obenauer1976), relativization, focalization and topicalization (Kirkwood Reference Kirkwood1970, Reference Kirkwood1977; Fanselow Reference Fanselow1988; van Riemsdijk Reference van Riemsdijk and Benincà1989; Fanselow & Ćavar Reference Fanselow, Ćavar and Alexiadou2002; Butler & Mathieu Reference Butler and Mathieu2004; Mchombo et al. Reference Mchombo, Morimoto, Féry, Butt and King2005; Fanselow & Féry Reference Fanselow and Féry2006; Féry et al. Reference Féry, Fanselow and Paslawska2007; Ott Reference Ott2011, Reference Ott2012, Reference Ott2015a; Cardoso Reference Cardoso, Martins and Cardoso2018). Basaá is no exception.

Although previous studies have explored split constructions extensively, few have elaborated on whether or not split nominal constructions share semantic/pragmatic commonalities with their non-split counterparts (but see Obenauer Reference Obenauer1976, Reference Obenauer1983; de Swart Reference de Swart1992 and Mathieu Reference Mathieu2004). In this section I argue that symmetric DPs differ from their continuous counterparts pragmatically and semantically. The logical consequence of this being that nominal constructions with symmetric DPs should not be taken as syntactically derived from their continuous counterparts via a subextraction mechanism.

3.1. Focalization

Symmetric noun phrases can be associated with a focus interpretation, as illustrated in (21), where the noun phrase bíkaat bilâm bísámal ‘six nice books’ occurs continuously as a single constituent in the postverbal position. In (21b), the whole constituent made of the head noun bíkaat ‘books’ and all its modifiers is fronted for the purpose of focalization (underlining indicate focus in the English translation). In (21c), the head noun bíkaat ‘books’ and the quality adjective bilâm ‘nice’ have been fronted for the purposes focalization while the numeral modifier bísámal ‘six’ is stranded postverbally. The symbol # used here and throughout the paper indicates unattested interpretation.

Note that though (21b) and (21c) contain almost the same lexical elements, they differ considerably in interpretation. While (21a) and its counterpart in (21b) are ambiguous, sentence (21c) allows only one reading. In other words, (21b) conveys three different readings. First of all, it is true in every situation where somebody went to a shop and saw different items such as pens, books, bags, etc. and decided to buy only six nice books and nothing else. In this case, six nice books contrasts with other items such as pens, bags, etc. Secondly, (21b) holds in every situation where somebody went to a shop and saw a set of nice and unpleasant books. They decided to buy six nice ones, though the possibility of buying a different number of unpleasant ones is not excluded. Sentence (21b) holds in every context where someone went to a shop and saw only nice books and decided to buy six of them. In contrast, sentence (21c) can only be used in one context, precisely as a corrective reply to the statement ‘I heard that you bought six unpleasant books’ or ‘have you bought six unpleasant books or six nice ones?’. In this case, the numeral bísámal ‘six’ is taken as given information in the discourse whereas the adjective bilâm ‘nice’ can be associated either with new or given information with a contrastive interpretation in the sense of É. Kiss (Reference Katalin1998 and subsequent work). The Basaá data contradict a widely-held view that parts of a split are triggered by an asymmetric information structure (Pittner Reference Pittner1995, Féry Reference Féry, Schwabe and Winkler2007, Féry et al. Reference Féry, Fanselow and Paslawska2007, but see Ott Reference Ott2011 for an alternative view).On this view, in most cases, the fronted element has a topic interpretation, while the remnant is associated with focal information. According to these authors, a split construction arises as a way ‘to separate two accents which would be adjacent in an unmarked word order’ (Féry Reference Féry, Schwabe and Winkler2007: 69).Footnote 9 However, in the Basaá constructions in (21c) the fronted material is focal and can be new or given, while the modifier inside the clause represents given information.

3.2. Wh-questions

Starting from sentence (22a), the head noun bíkaat ‘books’ and its modifiers bímbɛ̂ ‘which’ and bikojɓágá ‘red’ co-occur postverbally as a single noun phrase. This word order is maintained in the wh-fronting construction in (22b). In contrast, in (22c) the noun bíkaat ‘books’ is fronted along with the interrogative word bímbɛ̂ ‘which’ while the colour adjective bikojɓágá ‘red’ remains in situ.

There is a clear semantic distinction between the sentences with continuous noun phrases in (22a)–(22b) and their counterpart in (22c). The presupposition associated with (22a) and (22b) is that all the books of the set are red. The question is about the identity (biology, physics, etc.) of the red books. But in (22c), there is a set of different books that have different colours. Here, the question is about the identity of the books x of the set of different books such that x have a red colour.

The unifying factor between the sentences in (22) is at the level of d-linking, triggered by the presence of the D-linked interrogative phrase bímbɛ̂ ‘which’ in the phrase bímbɛ̂ bíkaat bíkojɓágá ‘which red books’ in (22a) and (22b), and in the phrase bímbɛ̂ bíkaat ‘which books’ in (22c). The presence of this D-linked interrogative phrase implies that red books in the case of (22a) and (22b) or simply books in the case of (22c) has already been mentioned in a previous discourse. Hence, the wh-phrase ranges over a discourse-salient set of alternatives. By uttering the sentences in (22), the speaker is inquiring either about the identity of the red books, as in (22a)–(22b), or simply about the identity of the books x out of a set of different books, such that x have a red colour. Therefore, in these two readings both the books and the colour (red) represent given information. This indicates that no asymmetric information structure exists between the fronted nominal and the colour adjective inside the clause in (22c).

The interpretative mismatches attested between the continuous noun phrase in (22a) and (22b) and the construction in (22c) suggest that these constructions do not have the same syntactic structure. The split in (22c) cannot be derived from the continuous noun phrase in (22a) and (22b). Although the phenomenon in (22c) has been reported cross-linguistically (see Obenauer Reference Obenauer1976, Reference Obenauer1983; Fanselow & Ćavar Reference Fanselow, Ćavar and Alexiadou2002; Butler & Mathieu Reference Butler and Mathieu2004; Fanselow & Féry Reference Fanselow and Féry2006; Féry et al. Reference Féry, Fanselow and Paslawska2007 for Germanic, Romance and Slavic), to my knowledge, no attention has been paid from the perspective of African languages to the possible semantic/pragmatic relationship between continuous noun phrases their split counterparts.

3.3. Topicalization

It is not uncommon to find cases whereby a speaker makes use of these constructions to express contrast in terms of incompleteness or continuation in relation to some salient entities that have been mentioned in the discourse. Besides, these constructions can also be used in relation to an already mentioned entity without any contrastive effects. I refer to the former situation as contrastive topicalization (Büring Reference Büring1997, Reference Büring2003; Tamioka Reference Tamioka, Zimmermann and Féry2010) while the latter is simply referred to as aboutness topicalization in the sense of Reinhart (Reference Reinhart1981). To begin with, a sentence such as (23) can be associated with a wide range of readings as shown in (i)–(iii).

The reading in (23i) can be obtained as a partial answer to the question ‘what did you do with the items you received?’ where the phrase bitámb bilâm bikojɓágá ‘nice red shoes’ contrasts with other possible salient alternatives (e.g. clothes, books, bags, etc.) in the discourse. In this context, the phrase bitámb bilâm bikojɓágá ‘nice red shoes’ represents an incomplete or partial answer. The reading in (23ii) holds in every context where there is a set of ‘nice red shoes’ and ‘nice black ones’ such that ‘red’ contrasts with ‘black’. The ‘nice red shoes’ are identified as a subset of the set {nice red shoes, nice black shoes} for which the act of selling holds. Similar results are obtained in (23iii), where nice red shoes and unpleasant red ones are salient alternatives that contrast with each other in the discourse.

The following example shows that though (23) and (24) contain the same lexical material and are interpreted as contrastive topic constructions, they differ considerably:

Only the reading analogous to (23iii) is possible in (24). Thus, (24) is felicitously interpreted in a situation where the phrase ‘nice shoes’ contrasts with ‘unpleasant ones’.

As shown in (25) and (26), (23) and (24) can also be interpreted as aboutness topic constructions.

From a syntactic point of view, it can be noted that while the question under discussion in (25) requires a topic with a large syntactic structure i.e. bitámb bilâm bikojɓágá ‘nice red shoes’, its counterpart in (26) requires a topic with a smaller structure i.e. bitámb bilâm ‘nice shoes’. However, the fronting of the continuous noun phrase bitámb bilâm bikojɓágá ‘nice red shoes’ requires a resumptive pronoun inside the clause, while the fronting of its counterpart bitámb bilâm ‘nice shoes’ with a DP-internal null head modifier bikojɓágá ‘red’ does not allow resumption. This indicates that the two constructions have different syntactic sources, as will be discussed in detail in Section 5.

Last but not least, another interesting aspect about Basaá is that the phenomenon under discussion also allows for topic constructions with genus-speciesFootnote 10 effects. In other words, there are structural configurations in which the topicalized DP and its correlate inside the clause appear in a super-ordinate/hyponym relation (Mchombo Reference Mchombo2006: 149–150). These effects have been reported crosslinguistically (e.g. van Riemsdijk Reference van Riemsdijk and Benincà1989 for Chinese and Japanese; Mchombo Reference Mchombo2006 for Chichewa; Ott Reference Ott2011, Reference Ott2015a for German).

In (27a), the noun dinuní ‘birds’ denotes a superordinate or general term whose meaning is specified by the hyponym ŋgôs ‘parrots’, while the reverse word order is disallowed as shown in (27b).

This construction has been referred to in the literature as aboutnessFootnote 11 topic topicalization (Badan & Del Gobbo Reference Badan, Gobbo, Benincà and Munaro2010), or gapless splits (see Fanselow & Ćavar Reference Fanselow, Ćavar and Alexiadou2002; Puig Waldmüller Reference Puig Waldmüller2006; Nolda Reference Nolda2007; Ott Reference Ott2011, Reference Ott2012, Reference Ott2015a). As shown in (28), under no circumstances can the super-ordinate and its hyponym form a single syntactic unit (see Mchombo Reference Mchombo2006 for similar results in Chichewa).

These facts show that the sentence-initial constituent and its counterpart inside the clause in (27a) are not related syntactically.

3.4. Relativization

Relativization is another construction where the head of a relative can be fronted alone or along with some modifier(s), leaving other modifiers in isolation inside the clause (see also Butler & Mathieu Reference Butler and Mathieu2004 for Imbabura Quechua, Mohawk and Japanese; Cardoso Reference Cardoso, Martins and Cardoso2018 for Early Stage Portuguese). Let us consider the sentence in (29a) as the basic form in which the head noun ɓodaá ‘women’ and the modifiers ɓalâm ‘nice’ and ɓásámal ‘six’ co-occur as a single constituent. When this constituent is fronted, as in (29b), it is ambiguously interpreted as a restrictive relative clause with either a broad reading on ‘six nice women’ or a narrow reading on ‘nice women’. Conversely, in (29c), where the head noun ɓodaá ‘women’ and the numeral ɓásámal ‘six’ are fronted for the purpose of relativization, with the quality adjective ɓalâm ‘nice’ stranded, only a narrow reading is possible. More precisely, (29c) is true in every context where less than six women were called out of a set of six.

These semantic mismatches between the relative clause in (29b) and its counterpart in (29c) suggest that the continuous noun phrase in the former and the split in the latter do not have the same underlying structure. The absence of such structural connectedness is also attested in passive and active constructions,Footnote 12 but cannot be discussed here for reasons of space.

3.5. Interim conclusion

The preceding discussion has revealed that nominal constructions in which the head noun and some of its modifiers are fronted as a single constituent differ in meaning from their counterparts in which a fronted nominal chunk seems to have been separated from a DP-internal nominal modifier. The following section is concerned with the syntactic properties of symmetric noun phrases and provides evidence that the fronted nominal chunk and the stranded nominal inside the clause do not form a constituent in the underlying syntactic structure.

4. The syntactic properties of symmetric noun phrases

In this section, I discuss the constraints that underlie noun phrases with apparent discontinuity. The different properties to be discussed include island and reconstruction effects, noun class and number mismatches, multiple and inverted constructions (known in the literature as multiple and inverted splits).

4.1. Ross’s (Reference Ross1967) islands

Focus fronting (see (30a)), wh-fronting (see (30b)) and relativization (see (30c)) out of a complex NP (and other syntactic islands; Ross Reference Ross1967) are disallowed in constructions with symmetric noun phrases (see van Riemsdijk Reference van Riemsdijk and Benincà1989; Ott Reference Ott2011, Reference Ott2015a, among others, for crosslinguistic evidence). However, there are no detectable island effects for topicalization in the same context, as shown in (30d). In the following examples, the underscore ___ notation indicates the original position of the extracted element(s), and square brackets [ ] indicate islands. Because topics are insensitive to islands, I assume they have no syntactic connection with the host clause, which therefore contains no sign of extraction.

As shown in (31), the same results obtain with respect to the Coordinate Structure Constraint.

4.2. Genitive phrase islands

Genitive phrases are islands for syntactic movement in Basaá. Thus, wh-movement (32b), focalization (32c), relativization (32d), and passivization (32e) out of a genetive phrase are probibited, while topicalization is acceptable in the same context, see (32f). In the latter case, the topicalized noun malêt ‘teacher’ should be resumed sentence-internally by the complex mê (lit. ‘of his’), indicating that the topicalized constituent arrives at the clause-initial position by internal merge (movement). The genitive phrase is represented in square brackets.

The data pattern in (33) then indicates that split noun phrases formed by wh-fronting (33b), focus fronting (33c), relativization (33d) and passivization (33e) involve movement, while those formed by topicalization as in (33f) do not.Footnote 13

As predicted by this analysis, the island effects in (33b–e) are avoided if the syntactic configuration that forms the island is fully extracted:

As seen in (34), the fronted constituent (shown in square brackets) is coindexed with a trace inside the sentence while the stranded adjective forms an independent constituent. Crucially, the grammaticality of the examples in (34) also indicates that the stranded adjective inside the clause and the fronted material are two independent constituents. This state of affairs suggests that the island in these cases involves two nominals connected by the linking morpheme only. I will argue in section five that the syntactic structure for (34) is roughly that in (35), where DP1, containing the head noun (and its modifiers), originates as the subject of a small clause prior to movement. DP2 is the predicate of this small clause and contains an elliptical head noun and a stranded modifier (e indicates ellipsis).

4.3. The subject island and oblique objects

As with genitive islands, extraction out of a subject in regular cases is banned, as seen in (36b), while a split construction is perfectly acceptable in the same context, as in (36c).

Similarly, extraction of an oblique object is ungrammatical, as seen in (37b), while a split is perfectly correct, as in (37c).

These facts are similar to the ones discussed above in terms of constituency and island (in)sensitivity, partly supporting Fanselow & Ćavar (Reference Fanselow, Ćavar and Alexiadou2002) and Ott (Reference Ott2015a), who show convincingly that split noun phrases are insensitive to some constraints that constrain regular cases of extraction in German.

4.4. Binding and reconstruction effects

The following examples indicate that the relationship between the fronted constituent and the remnant inside the clause exhibits connectivity effects for Principle A. This holds only for focus fronting (38b), wh-fronting (38c), and relative clause (38d) constructions. The same effects are not present in topicalization (38e). Sentence (38a) is considered as the input.

The reflexixe njɛ́mɛdɛ́ ‘herself’ inside the DP bítitî gwê bilâm bísámal njɛ́mɛdɛ́ ‘six nice pictures of herself’ is bound by the matrix subject Bella not only in the input sentence in (38a), but also in the focus, wh-question and relative clause constructions. Conversely, binding between the matrix subject Bella and the reflexixe njɛ́mɛdɛ́ is impossible in topicalization (38e). These facts can be readily understood if the split constructions in (38b–d) are formed through movement, while the topic fronting construction is not.Footnote 14

Connectivity effects are also detectable for variable binding in focus fronting (40b), wh-movement (39c), relativization (39d), but unattested in topicalization (39e).

The grammaticality of (39b)–(39d) on the bound reading of the pronoun indicates that the quantified subject híkií ŋúdú ‘every student’ can bind the pronominal element gwê ‘his’ contained in the fronted DP bikaat gwê bilam ‘his nice books’. This can be understood if the fronted DP reconstructs to its canonical position in the c-command domain of the quantified subject híkií ŋúdú ‘every student’. Conversely, if topic fronting is not derived through movement, as suggested above, then the impossibility of the bound reading in (39e) is expected.

4.5. Noun class and number mismatch

This section discusses constructions in which a fronted DP with plural morphology co-occurs in the same clause with a stranded modifier which bears singular morphology. I discuss this morphological mismatch and use it as additional evidence for the view that no syntactic connectedness relates the clause-initial DP and the remnant inside the clause. This morphological mismatch is present in focus fronting, wh-question, relative clause and passive constructions. In the baseline sentence in (40), the singular noun híɓɛŋ ‘pigeon’ belongs to class 19 in the Basaá noun class system. The postmodifiers hilâm ‘nice’ and hjádá ‘one’ agree with this noun in class and number.

In (41), the topicalized plural DP diɓɛŋ dilâm ‘nice pigeons’ co-occurs with the singular numeral modifier hjádá ‘one’ inside the clause.

This morphological mismatch suggests that the fronted plural DP diɓɛŋ dilâm ‘nice pigeons’ and the remnant hjádá ‘one’ are not related syntactically. This is further supported by the ungrammatical sentence (42), in which the plural DP diɓɛŋ dilâm ‘nice pigeons’ and the singular modifier hjádá ‘one’ co-occur adjacently as a single constituent.

The same morphological mismatch is found in focus, relative clause and wh-question constructions, as illustrated in (43), with (39a) taken as the input sentence.

The above sentences suggest that the sentence-initial plural DP and the sentence-internal singular DP are merged independently: no subextraction occurs in these constructions. Similar morphological mismatches have been discussed cross-linguistically (e.g. Haider Reference Haider and Abraham1985; Fanselow Reference Fanselow1988; Fanselow & Ćavar Reference Fanselow, Ćavar and Alexiadou2002; Ott Reference Ott2011, Reference Ott2015a) and presented as arguments against the view that the fronted DP and the remnant inside the clause form a single constituent underlyingly.

4.6. The DP hypothesis, lexical degeneration and the impossibility of subextraction

At first glance, it is tempting to suggest that a passive construction such as (44b) is derived by simply subextracting the chunk mambɔ́t malâm ‘nice clothes’ from the continuous noun phrase mámbɔ́t malâm mapɛ́ ‘other nice clothes’ (44a) as depicted in (45), where ___ indicates the original position of the chunk mambɔ́t malâm ‘nice clothes’ prior to extraction. Strikethrough indicates the original position of the lexical verb prior to movement to Voice, the head of VoiceP.

If movement is restricted to heads and maximal projections (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1986), the fact that in (45) the head noun moves along with one modifier, leaving the stranded indefinite modifier mápɛ́ ‘other’ behind, poses a theoretical problem: such movement targets neither a maximal projection nor a head. This is conceptually problematic as movement targets an X′ category, as proposed in van Riemsdijk (Reference van Riemsdijk and Benincà1989). If we adopt instead a version of the DP hypothesis according to which adjectives and other nominal modifiers such as demonstratives are specifiers of functional projections within the extended nominal projection (e.g. Cinque Reference Cinque, Cinque, Koster, Pollock, Rizzi and Zanuttini1994; Brugè Reference Brugè and Cinque2002; Laenzlinger Reference Laenzlinger2005a, Reference Laenzlingerb), then adjunction of adjectives to NP is banned, as in Kayne (Reference Kayne1994). Rather, adjectives are merged as specifiers of functional projections in-between the functional domain headed by D and the lexical layer headed by the lexical noun. This approach seems to undermine the structure in (45) adequately. In line with the specifier-based approach and the N-raising analysis of Cinque (Reference Cinque, Cinque, Koster, Pollock, Rizzi and Zanuttini1994), the lexical noun mambɔ́t ‘clothes originates as the head of the lowest NP below the functional projections containing the modifiers mapɛ́ ‘other’ and malâm ‘nice’ as depicted in (46).

The surface order mámbɔ́t malâm mapɛ́ ‘other nice clothes’ in (44a), as depicted in (46) is obtained through cyclic head raising (Cinque Reference Cinque, Cinque, Koster, Pollock, Rizzi and Zanuttini1994) to D of the head noun mámbɔ́t ‘clothes’ via the intermediate functional head positions, the specifiers of which are occupied by the modifiers mapɛ́ ‘other’ and malâm ‘nice’. This successive cyclic N-movement is allowed as long as no intervening head blocks it. If (46) is derived along these lines, then there is no principled way to allow subextraction of the chunk mambɔ́t malâm ‘nice clothes’ out of the DP and the stranding of the modifier mapɛ́ ‘other’, as in (45). Therefore, even the Cinquian approach is undermined by the Basaá empirical data.

Another argument against subextraction is lexical degeneration. In the quantified noun phrase liɓím lí bíkaat (lit. ‘a good number of books’) in (47), the lexical item liɓím (lit.‘a good number’) and the noun bíkaat ‘books’ form a continuous noun phrase along with the linking morpheme lí as shown in (47a).

In the passive (47b) and focus (47c) constructions above, the noun bikaat ‘books’ has been fronted alone, while the nominal modifier liɓím ‘a good number’ is stranded. The linking morpheme lí is disallowed in the split constructions in (47b) and (47c). This indicates that there is a lexical degeneration or loss of this functional morpheme in the split forms: the linking morpheme cannot be left adjacent to the fronted noun bikaat ‘books’. Similarly, it cannot occur on the right of the stranded modifier liɓím ‘a good number’, as in the continuous noun phrase in (47a). This constitutes a major challenge to a movement analysis based on subextraction, which would certainly resort to postsyntactic mechanisms to account for this phenomenon. Lexical degeneration remains problematic on the assumption that the fronted constituent and the remnant are not parts of a single source constituent in the split, making it difficult to explain why and how the linking morpheme gets deleted in the split forms. I conclude that the phenomenon under study in Basaá cannot be considered an instance of a discontinuous noun phrase as in Tappe (Reference Tappe, Bhatt, Löbel and Schmidt1989), van Riemsdijk (Reference van Riemsdijk and Benincà1989), Diesing (Reference Diesing1992), Franks & Progovac (Reference Franks, Progovac, Fowler, Cooper and Ludwig1994), Kniffka (Reference Kniffka1996) and Sekerina (Reference Sekerina1997), where the subparts of the split form a single source constituent underlyingly, with the discontinuous noun phrase formed by subextration. Instead, the view defended in this paper is that the fronted nominal and the null head modifier inside the clause are related through a subject–predicate relation within a small clause (Moro Reference Moro1997, Reference Moro2000, Den Dikken Reference Dikken, Alexiadou and Wilder1998), with subsequent raising of the subject under closest c-command. As a result, no violation of structure dependency arises, despite appearances.

4.7. Multiple fronting and inversion

In this section, I show that so-called multiple splits (see e.g. Pafel Reference Pafel, Lutz and Pafel1996, Fanselow & Ćavar Reference Fanselow, Ćavar and Alexiadou2002, van Hoof Reference van Hoof, Everaert and van Riemsdijk2006, Féry et al. Reference Féry, Fanselow and Paslawska2007, Ott Reference Ott2011) are also present in Basaá, whereas inverted splits are unattested. In (48a), the noun mambɔ́t ‘clothes’ is preceded by the demonstrative máná ‘these’ and followed by the quality and indefinite adjectives malâm ‘nice’ and mapɛ́ ‘other’, respectively.

In the multiple fronting construction in (48b), the chunk máná mambɔ́t ‘these clothes’ is topicalized and precedes the focalized adjective malâm ‘nice’. The null head indefinite modifier mápɛ́ ‘other’ remains in-situ. The illicitness of (48c) is linked to the fact that the topic is preceded by the focus. Note that this topic–focus hierarchy is not only attributed to the nature of the construction under study, but also to the Basaá grammar as a whole. In Basaá, topic should always precede focus (Bassong Reference Bassong2010, Reference Bassong2014)Footnote 15 as illustrated in (49), where the topic makebla malâm ‘nice presents’ should precede (see (49b)) and not follow (see (49c)) the focus mudaá ‘woman’.

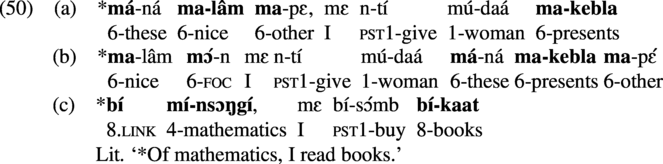

Unlike Croatian, Estonian,German, Polish, Serbian (Fanselow & Ćavar Reference Fanselow, Ćavar and Alexiadou2002, Fanselow & Féry Reference Fanselow and Féry2006), French, Classical Greek (Mathieu Reference Mathieu2004), Chichewa (Mchombo et al. Reference Mchombo, Morimoto, Féry, Butt and King2005, Mchombo Reference Mchombo2006) and Early Stage Portuguese (Cardoso Reference Cardoso, Martins and Cardoso2018), where modifiers and complements of the head noun can be fronted leaving the latter in situ, Basaá does not allow such a reverse word order. Under no circumstances can null head modifiers or complements of the head noun be fronted leaving the head stranded. This is illustrated in (50).

The illicitness of these sentences boils down the fact that in Basaá N/NP ellipsis is dependent on discourse structure requirements. More precisely, N/NP ellipsis is possible only when the elided noun is e-given i.e. if it is given or salient in the discourse. When this condition is not met, ungrammaticality arises. The grammaticality of sentences such as (48) and (49b) among others follows from this requirement. In these grammatical cases, the fronted element is the head noun or the head noun along with its modifier(s) while the stranded remnant stays in situ. This suggests that there is crosslinguistic variation: some languages like Croatian, French, German, Classical Greek, etc., which are reported to be morphologically rich, allow inverted splits while others, such as Basaá, do not, despite their strong morphological richness.Footnote 16

4.8. Interim conclusion

I have shown that split noun phrases in focus fronting, wh-fronting and relative clauses exhibit reflexes of syntactic movement, as evidenced by island and binding reconstruction effects (Section 4.1 to Section 4.3). Because topic fronting is island-insensitive and exhibits no binding reconstruction effects, topicalization seems not to be derived by internal merge of the topic in the clausal left periphery. Morphological mismatches between the clause-initial DP constituent and its reduced DP counterpart inside the clause provided a strong empirical argument against syntactic connectedness between the fronted constituent in clause-initial position and the stranded remnant inside the clause. I also provided a conceptual argument to this effect, based on the impossibility of a subextraction analysis. These constructions are therefore by no means instances of syntactic discontinuity. It was also shown in Section 4.6 that multiple fronting is possible in a topic–focus hierarchy while inverted structures (known as inverted splits) are disallowed due to the licensing requirements on N/NP ellipsis.

In the following section, I partly capitalize on Mathieu (Reference Mathieu2004) and Ott’s (Reference Ott2011, Reference Ott2012, Reference Ott2015a) proposals, according to which the fronted constituent and the remnant inside the clause are syntactically independent, but semantically related in a predicate relation inside the VP. Building on Ott, and given that this initial merge position is syntactically unstable, syntactic movement needs to occur for the purpose of feature-checking, labelling and asymmetrization.

5. The competing approaches

I will not discuss the various proposals in the literature to account for the syntax of the phenomenon under study. For an in-depth investigation on the topic, I refer the reader to Tappe (Reference Tappe, Bhatt, Löbel and Schmidt1989), van Riemsdijk (Reference van Riemsdijk and Benincà1989), Diesing (Reference Diesing1992), Franks & Progovac (Reference Franks, Progovac, Fowler, Cooper and Ludwig1994), Kniffka (Reference Kniffka1996) and Sekerina (Reference Sekerina1997) for a simple movement analysis, to Hale (Reference Hale1983) and Jelinek (Reference Jelinek1984) for a base-generation approach, to Fanselow & Ćavar (Reference Fanselow, Ćavar and Alexiadou2002) for a copy and deletion approach, to Mathieu (Reference Mathieu2004), Mathieu & Sitaridou (Reference Mathieu, Sitaridou, Batllori, Hernanz, Picallo and Roca2005), and Ott (Reference Ott2011, Reference Ott2012, Reference Ott2015a) for a predication approach, and to Cardoso (Reference Cardoso, Martins and Cardoso2018) for a remnant movement analysis.

5.1. The proposal

In the last decade, Ott (Reference Ott2011, Reference Ott2012, Reference Ott2015a) has proposed an approach in which the NP in clause-initial position has a topic reading while the remnant inside the clause is a term-denoting DP. Both NP and DP are predicatively related underlyingly in a symmetric structure which is syntactically unstable. According to him, a German sentence such as (51) is derived as in the simplified structure in (52).

According to Ott, Seltene Raubvoþgel ‘rare birds of prey’ is an NP while ein paar Bussarde gesehen ‘a couple of buzzards’ is a DP. The two are initially merged as predicate and subject in an argument/adjunct position within the VP. Following Chomsky (Reference Chomsky2013), Ott suggests that this original merge position is locally unstable because it has no detectable head (label). As a result of this instability, predicate inversion in the sense of Moro (Reference Moro1997, Reference Moro2000) and Den Dikken (Reference Dikken, Alexiadou and Wilder1998) must apply by moving the predicateFootnote 17 NP to the left periphery of the clause, yielding split topicalization whereby the fronted predicate and the remnant subject inside the clause end up being syntactically asymmetric.

My analysis mostly borrows from Mathieu (Reference Mathieu2004), Mathieu & Sitaridou (Reference Mathieu, Sitaridou, Batllori, Hernanz, Picallo and Roca2005) and Ott (Reference Ott2011, Reference Ott2012, Reference Ott2015a) in terms of constituent independency (see also Fanselow Reference Fanselow1988) and the search of syntactic asymmetry (Ott Reference Ott2015a and related work). However, deviating from their analyses, I propose a clause structure in which a lexical verb (overt/covert) selects a small clause (SC) complement with a subject–predicate structure in which a subject DP1 and its reduced DP2 counterpart in the predicate position are initially merged symmetrically. This is illustrated in the simplified structure in (53), where angle brackets indicate movement.

Note that DP2 is the remnant that can be made up of one or more than one modifier and an elliptical N head (represented by e). Recall from Section 2.2.3 that DP2 is reduced as a consequence of N/NP ellipsis. As opposed to Ott’s predicate inversion strategy, I propose that the constituent which undergoes movement is the subject DP1 rather than the reduced predicate DP2. The fronting of DP1 is motivated by two factors. First of all, it follows from an Agree relation between a probing head with uninterpretable features and DP1 (goal) with matching features under closest c-command (Chomsky Reference Chomsky, Martin, Michaels and Uriagereka2000, Reference Chomsky and Kenstowicz2001).

Secondly, following Chomsky (Reference Chomsky2013) and as recently developed by Ott (Reference Ott2015a) and related work, I suggest that the underlying structure of a split involves a predication relation between a subject DP1 and a predicate DP2 within a VP-internal argument position that is label-less initially and syntactically unstable as shown by the symbol ? in (55a). For the configuration {DP1 DP2} to enter into thematic interpretation, it needs to be assigned a label by moving either DP1 or DP2. Being the closest goal to a matching probe, DP1 undergoes movement for the purpose feature-checking, which also enables asymmetrization and labelling, as shown in (55b). In other words, once DP1 raises into a dedicated checking position (to be determined in the following sections) via the vP edge, the initial configuration {DP1 DP2}, now labelled as DP becomes accessible to thematic interpretation as in Ott (Reference Ott2015a).

How (53)–(55) are implemented for Basaá is the subject matter of the following sections.

5.1.1. The derivation of focus constructions

Two main phrasal movements are involved in the derivation of the focus construction. They include A-movement of DP1 into the main TP and A′-movement of a null operator into the embedded Spec–CP of a headless relative clause. Before discussing focus fronting with split noun phrases, I will talk about the derivation of ordinary focus fronting (see Bassong Reference Bassong2014, Reference Bassong2019; Hamlaoui & Makasso Reference Hamlaoui and Makasso2015 for recent analyses of focus fronting in Basaá).

5.1.1.1. Deriving ordinary focus fronting

Sentence (56b), derived from the basic structure in (56a) is an instance of ordinary focus fronting. Small capitals in the translation sentences in (56) and (57) and similar examples indicate focus.

Focus fronting in Basaá exhibits properties of long-distance dependency such as unboundedness (57a), parasitic gaps (57b), island sensitivity (58) and reconstruction effects (59).

These facts follow Bassong (Reference Bassong2014, Reference Bassong2019) and contradict Hamlaoui & Makasso’s (Reference Hamlaoui and Makasso2015) claim that focus fronting in Basaá lacks island and connectivity effects. I suggest that in focus fronting, the focalized constituent is underlyingly merged inside a small clause as the subject of predication while a headless relative clause is merged as the predicate as in Belletti (Reference Belletti and Belletti2009). I also suggest, as in Ott (Reference Ott2015a) and related work, that this original configuration is syntactically unstable and needs to be asymmetrized by movement. A null copula which is the equivalent of be-like copula in the sense of Belletti is a kind of light verb which selects a small clause complement, as shown in (60). This copula starts in V and ends up under the main T head. DP1, the subject of predication, raises into the matrix TP position to satisfy the EPP requirements.

According to Bassong (Reference Bassong2019), subject raising arises in the absence of an expletive subject that would otherwise fulfil the EPP requirements. DP2 contains a headless relative in which operator movement takes place. More precisely, following (60), sentence (61a) is derived as illustrated in (61b).

As shown in (61b), DP1 and DP2 are unrelated syntactically but semantically related in a subject–predicate relation inside a small clause, the complement of the null copula ꝋ. The syntactic configuration of this small clause is unstable and needs to be labelled. DP1 raises to the subject position of the matrix TP (via the vP edge; little vP is intentionally omitted from the diagram) for the purpose of asymmetrization and labelling while a null operator inside the headless relative moves into Spec–CP via Spec–FocP. I assume that the null operator inside the headless CP and the subject of predication are semantically identical, i.e. they have matching features. As such, the availability of connectivity effects arises as a result of feature matching between the raised subject and the null operator. The fact that a predication relation holds between the raised subject and the predicate and that there is feature identity between the two constituents explains why reconstruction is possible. I will adopt the same analysis in the following section.

5.1.1.2. Deriving focus fronting with symmetric noun phrases

Let us begin with the following sentence:

The fronted DP1 originates as the subject of predication while the remnant mápɛ́ ‘other’ is contained in the predicate DP2, the complement of which is a headless relative clause. This original merger position is syntactically unstable as it has no detectable label (Chomsky Reference Chomsky2013). CP, the complement of D2 is a headless relative containing the modifier mápɛ́ ‘other’

As is the case with ordinary focus fronting seen in (61) above, the verbal element that selects the small clause in focus constructions is phonologically silent and represented by the light verb ø. The derivation of focus fronting with symmetric noun phrases is peculiar in the sense that it involves two levels of predication. The first one is contained in the matrix clause and is selected by a null copula. The second one inside a headless relative is selected by the verb sɔ́mb ‘buy’. One ends up with two parallel structures containing each a syntactically unstable configuration. Adopting Ott’s analysis, I assume that each of these configurations is unstable and needs to be asymmetrized by movement. In the matrix clause, the subject, DP1 mambɔ́t malâm ‘nice clothes’, in the high predication moves into the main TP position by virtue of being the closest category to the T head for the purpose of the EPP. This symmetry-breaking movement à la Ott is followed by labelling the initial small clause as DP. I assume that movement into the main and embedded clauses takes place simultaneously. In this case, the same scenario takes place inside the headless relative clause. More precisely, I assume that a null operator and the null head modifier mápɛ́ ‘other’ enter in the same predication relation as in the matrix clause. As the original merger position between a null operator in the subject position and the stranded modifier in the embedded clause is unstable, the former needs to move to the C-phase for the sake of asymmetrization and checking.

As for the simplified structure of DP2 containing the relative clause, I follow Kayne’s (Reference Kayne1994) head raisng analysis of relative clauses according to which a functional D category selects a CP complement. With this in mind, a CP-internal movement operation normally targets a headless/elliptical NP and a null relative operator. Globally, the syntax of focus fronting with an apparent discontinuity is a bit intricate as it involves two parallel syntactic configurations, each one having a subject predicate structure that is syntactically unstable. I assume that symmetry-breaking movement, the labeling and checking operations in both cases arise simultaneously under closest c-command.

5.1.2. The derivation of relative clauses and wh-questions

The syntactic derivation of relative clauses is almost the same as the previous ones. The difference can be observed in (65). Consider example (64).

I adopt Kayne’s (Reference Kayne1994) head raising analysis of relative clauses (see Jenks et al. Reference Jenks, Makasso, Hyman, Atindogbé and Grollemund2017 for a study of relative clauses in Basaá) and the tenet that the fronted constituent and the stranded modifier inside the clause are linked semantically under predication in a syntactically unstable configuration. As shown in (65), the verb kosna ‘receive’ selects a small clause complement, the subject of which is DP1 containing bitámb bilâm ‘nice shoes’ and the relative marker (operator) bí. The predicate is DP2 containing the stranded modifier bisámal ‘six’. A functional D head occupied by the definiteness marker í selects a CP complement.

The final stage in (65) is obtained by leaving the stranded numeral bísámal ‘six’ in situ and raising the subject DP1 to Spec–CP for the purpose of asymmetrizing an initially unstable structure and as a consequence of Agree under closest c-command. Closest c-command holds between the raised constituent and the C head whose (OP)erator features are uninterpretable. In line with (54), DP1 is the closest goal whose features match and value the uninterpretable operator features on C. Once DP1 is raised into Spec–CP, these features are checked and deleted.

Similarly, and while keeping with the small clause hypothesis, I propose that in (66), the quantifier phrase/DP1 mámbɛ̂ mámbɔ́t ‘which clothes’ and the modifier mápɛ́ ‘other’ are underlingly merged in a subject–predicate relation which is syntactically unstable as illustrated in (67).

First of all, I assume that the head C of CP is a probe endowed with uninterpretable operator features. Secondly, the initial merger position between DP1 and DP2 before movement is unstable and lacks a label. The uninterpretable features under C need to be valued by a category with matching features. Under minimalist assumptions, the closest phrasal category that meets these requirements in (67) is the quantifier phrase mámbɛ̂ mámbɔ́t ‘which clothes’. Once an Agree relation has been established between C and mámbɛ̂ mámbɔ́t ‘which clothes’ under closest c-command, the latter is attracted by C into its specifier position for checking purposes, yielding the sentence in (67), whereby the quantifer phrase mámbɛ̂ mámbɔ́t ‘which clothes’ is clause-initial while the null head modifier mapɛ́ ‘other’ occurs inside the clause. A′-movement of the quantifier phrase into Spec–CP is then followed by the labelling of the small clause as a DP category which contains DP2 and a copy of DP1.

5.1.3. The derivation of topic constructions

Based on the absence of island, binding and reconstruction effects, I showed that topic constructions as discussed here do not exhibit reflexes of syntactic movement. Furthermore, arguments were provided from genus-species effectsFootnote 18 and morphological mismatches (see Section 4.4) that topics in the construction under study are base-generated in the clausal left periphery rather than moved there. Though a base-generation analysis seems to follow from these semantic and syntactic arguments, there still remains a striking question as to the licensing of the base-generated DP in the left periphery. Case and theta-role facts make it difficult to handle these constructions as involving just a simple base-generation. The facts discussed here can be handled at least from two diverging approaches, namely Cinque’s (Reference Cinque1977, Reference Cinque, Ehlich and van Riemsdijk1983) and more recently Ott’s (Reference Ott2015b). From the perspective of Cinque, as these topic constructions show neither syntactic connectedness nor connectivity effects, they cannot be conceived of as being part of core sentence grammar. Rather, they can be taken as extra-sentential constituents akin to parentheticals. As such, they can be analysed as instances of hanging topics and not part of sentence grammar.

The sentences in (68a) and (68b) can be syntactically derived as sketched out in (69a) and (69b), respectively. The Ω symbol acts as a discourse category which projects an ΩP above CP.

In (69), the topicalized constituent is structurally unrelated to the host CP as no syntactic dependency holds between the topic and the host clause. In the spirit of Cinque (Reference Cinque1977), the nominal element inside the clause is a kind of epithet that represents a description of the topic. In Cinque’s (Reference Cinque1990) terms, only a binding chain relates the hanging topic to its correlate inside the host clause via coindexation and through theta-role identity between the left dislocated constituent and the clause-internal remnant. Though this approach can account for the empirical facts, it nevertheless leaves two unanswered questions. Following Ott (Reference Ott2015b: 231), the first challenge to Cinque’s approach concerns case and theta-roles assignment. It remains difficult to explain how the extra-sentential constituent happens to share the same theta role and case.Footnote 19 Another issue raised by Ott concerning the analysis along the lines of (69) deals with binding. He points out that the non-local binding relation between the extra-sentential constituent and the epithet inside the clause corresponds to no known type of syntactic binding in the literature. Based on this and other problems related to the Cinquean approach, Ott (Reference Ott2015b)Footnote 20 proposes an alternative in terms of sentence ellipsis and linear juxtaposition.

According to Ott (Reference Ott2015b), in cases like (68) above, the fronted topic and its correlate are separately merged in two juxtaposed and parallel CPs, as sketched out in (70).

The simplified structure in (70a) shows that both CP1 and CP2 are complete clauses containing the verbal predicate tɛ́hɛ́ ‘see’. The latter assigns case and theta roles. Recall that CP1 and CP2 are juxtaposed in the discourse and parallel. Parallelism is explained by the fact that both clauses have an identical syntactic structure and contain almost the same lexical material. The semantic difference between the topic in CP1 and its correlate within CP2 is that the former denotes a superordinate term while its correlate inside the host clause is a hyponym. At the base, the hypernym dinuní dilâm ‘nice birds’ in CP1, and its epithet ŋgos ‘parrots’ inside CP2 are selected by the predicate tɛ́hɛ́ ‘see’ and assigned case and theta role in an identical way. The second step consists in fronting the topic to the left periphery of CP1 and triggering backward ellipsis of the IP from which extraction has taken place. Ellipsis arises in order to avoid the repetition of the same lexical material at PF (Ott Reference Ott2015b). Backward ellipsis of IP makes CP1 cataphoric in the sense of Ott (Reference Ott2015b) and is similar to previous work on clausal ellipsis (e.g. Ross Reference Ross, Binnick, Davison, Green and Morgan1969; Merchant Reference Merchant, Alexiadou, Fuhrhop, Law and Kleinhenz1998, Reference Merchant2001, Reference Merchant2004; Brunetti Reference Brunetti, Garding and Tsujimura2003). The difference between CP1 and CP2 is that the former contains the topicalized material and an unpronounced IP. The juxtaposed CP containing the epithet is fully realized at PF. The unpronounced IP inside CP1 is easily recovered under identity between CP1 and CP2. Following Ott, no syntactic connection exists between the two clauses. Both ae simply linked by means of cataphoric ellipsis and anaphoricity between the topic and its correlate. The latter is a free nominal expression which is connected cross-sententially to the topic. This approach is appealing in many respects. First of all, it shows that the target of ellipsis is a constituent after movementFootnote 21 has taken place. Secondly, it nicely shows how theta-role and case marking work, weakening the possibility of theta-role sharing. Thirdly, the presence of an intonation break (represented by a comma) between the topic and the host CP2 seems to support an analysis along the lines of parenthetical prosody crosslinguistically.Footnote 22 Last but not least, Ott’s account nicely shows that the clausal left periphery can involve juxtaposition in the discourse as well, hence the absence of island and connectivity effects which are the hallmarks of syntactic dependency.

If the preceding analysis holds, then topicalization does not need to be derived from a predication structure like other constructions. An analysis based on ellipsis and juxtaposition sufficiently accounts for the empirical facts. In fact, an analysis along the lines of the small clause is simply weak because it is unable to account for the data under study. Adopting such an analysis suggests that (71a) and (71b) would be derived as indicated in (72).

Given the unavailability of syntactic connectedness between the topic and the remnant inside the clause, one would suggest that in (71a) and (71b), the DP dinuní dilâm ‘nice birds’ is base-generated in Spec–CP or Spec–TopP (Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997 and subsequent work) while a null pronominal element under DP1 is merged in the subject position of the small clause. The clause-internal DP2 ndígí hjádâ/ndígí ŋgos ‘only one/parrots’ is merged as the predicate of the small clause. In this case, a predication relation would be established between a null pronominal subject co-indexed with the topic and the predicate DP2 ndígí ŋgos ‘only parrots’ or ndígí hjádá ‘only one’. The absence of syntactic connectedness between the topic and the null pro raises a question with respect to case and theta-role marking as already discussed.

An analysis along these lines also faces a major challenge with respect to multiple fronting constructions like (73), where the topicalized constituent máná mambɔ́t ‘these clothes’ is followed by the focalized adjective malâm ‘nice’.

Along the lines of the small clause hypothesis, it follows from (73) that once the topicalized DP máná mambɔ́t ‘these clothes’ has been base-generated in the left periphery as in (74), the reduced DP1 containing the stranded adjective malâm ‘nice’ originally merges as the subject of the small clause prior to its movement into Spec–TP for the purposes of the EPP. The predicate DP2, the head of which selects a headless relative clause (CP) contains the modifier mápɛ́‘other’.

In (74), the null verbal copula selects a small clause containing the stranded adjective malâm ‘nice’ in the subject position and the predicate DP2 containing a headless relative clause in a way that is analogous to the proposal in Sections 5.1.2.1 and 5.1.2.2. The null head modifier malâm ‘nice’ raises into the main TP for the purpose of EPP and asymmetrization. Similarly, a null operator and the remnant mápɛ́ ‘other’ are merged inside the lowest small clause selected by the lexical verb sɔ́mb ‘buy’. A null operator moves into Spec–CP via Spec–FocP inside the predicate of the small clause. The derivation in (74) undermines (72) because the former shows that there is no slot to accommodate the null pronominal element which is co-indexed with the fronted topic (72). Clearly, once the null head adjectival modifier malâm ‘nice’ is merged as the subject of predication, no slot is left for the null pronominal. This indicates that (72) is problematic and should be revised. The structure in (74) is also problematic because it is monoclausal. The topic is base-generated in the left periphery. An analysis along the lines of clausal ellipsis and endorphoric linkage (Ott Reference Ott2015b) can adequately solve this problem.

In a multiple fronting construction such as (73) repeated as (75) and following Ott (Reference Ott2015b), the derivation will proceed as in (76).

After CP1 and CP2 have been linked in the discourse, the constituent máná malaŋ ‘these onions’ is merged inside the VP contained in CP1. The same operation takes place simultaneously in CP2 where the small clause containing the null head modifier malâm ‘nice’ and the DP containing a headless relative clause are assigned case and theta roles. As the small clause containing the modifier malâm ‘nice’ in the subject position and the DP2 predicate is syntactically unstable, the stranded adjective malâm ‘nice’ raises into Spec–TP for the purpose of the EPP asymmetrization. This renders the fronted adjective malâm ‘nice’ asymmetric with the DP that contains a headless CP. I assume that the stranded modifier mápɛ́ ‘other’ in the headless CP is the predicate of a null operator inside another small clause selected by the lexical verb sɔ́mb ‘buy’. Given the syntactic instability of this initial configuration, the null operator raises into CP via FocP to make the structure asymmetric. Topic fronting of the DP máná malaŋ ‘these onions’ takes place inside CP2, followed by backward ellipsis of IP containing a silent copy of the extracted topic. Recall that backward ellipsis of TP inside CP1 takes place under identity with its counterpart inside CP2 as a way to avoid repetition of the lexical material inside CP2. After ellipsis, one ends up with a structure whereby the topicalized constituent máná malaŋ ‘these onions’ in Spec–CP/TopP seems to stand in discontinuity with the stranded modifiers malâm ‘nice’ and mápɛ́ ‘other’ inside the host clause.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, I have documented as well as comprehensively analysed some puzzling nominal constructions commonly known as split/discontinuous noun phrases or split topicalization. Based on data from the Bantu language Basaá, I have argued that split nominals, as realized in focus, relative clause and wh-movement constructions, involve a predicative structure between syntactically independent constituents, notably a clause-initial DP and a stranded null head modifier inside the clause. In these constructions, DP constituents are semantically linked underlyingly in a subject–predicate relation in a syntactically unstable configuration, the surface word order of which yields an apparent discontinuous nominal construction. This apparent discontinuity arises under closest c-command for the purpose feature-checking, labelling and asymetrization. It was argued that topic constructions are not derived from a predicative source, but are obtained by means of sentence juxtaposition in the discourse and clausal ellipsis. This analysis is supported by a number of semantic/pragmatic and morphosyntactic mismatches attested between these nominal constructions and continuous noun phrases.