1 Introduction

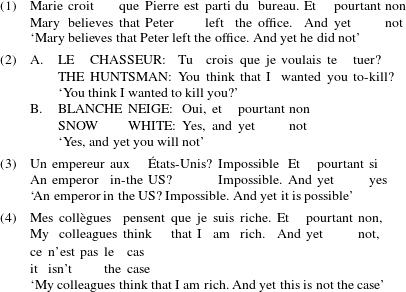

This paper provides an exploration into the semantic and discourse properties of the contrast brought about by the sequence et pourtant si/non in French. Some relevant examples for the proposed analysis are (1)–(6):Footnote [2]

However, the presence of et pourtant si/non is constrained as indicated in (5) and (6):

These examples are akin to those with the sequences pero no, però no, e invece no and si totusi (ba) da Footnote [3] found in other Romance languages such as Spanish, Catalan, Italian and Romanian in (7) to (10), respectively:Footnote [4]

However, contrary to the above data, a different strategy to convey the contrast brought about by et pourtant si/non in (1)–(4) and its equivalent in (7)–(10), respectively, is used in German, as exhibited by (11) below:

In (11), the negative contrast is expressed via an explicit sentence that can be glossed as ‘but that was not the case’.

A noteworthy feature of the discourses in (1)–(4) above is that some lexical material is left unpronounced after et pourtant si/non. Subsequently, the hearer must rely on other parts of the discourse, on contextual information or intonation so as to recover the missing antecedent.

In (1), the antecedent of et pourtant si/non is a proposition embedded under the propositional attitude verb croire (believe), which is a predicate expressing epistemic modality. In this example, the speaker suggests that the proposition under the scope of the modal predicate can be true and then rejects it via et pourtant non. This anaphoric ingredient is a most common feature of the use of et pourtant si/non. The dialogue in (2) includes a polar question to which a modalized answer is given and then rejected by et pourtant non, which also negates the embedded proposition in the scope of croire (believe). In (3), the answer to the question is the adjective impossible. The sequence et pourtant si both asserts the contents of the question and rejects the judgment of plausibility conveyed by the adjective. The contrast established by et pourtant si involves both what the proposition and the adjective express. Examples (5) and (6) are ruled out as they contain a contradiction. At this point, two significant questions arise: that of the nature of the missing part in the discourse and that of the element that conveys the contrast.

First, what is the nature of the missing part in discourses like (1), (2) and (4)?

Is the zero constituent in (12) a case of TP-Ellipsis, (12b), or a case of propositional anaphora (12c)?

Second, the presence of the Discursive Marker (from now on dm) pourtant is a clear indication of a contrast or direct opposition (Jayez Reference Jayez, Beyssade, Bonami, Hofherr and Corblin2003). Which are the contrasted elements? From the examples given in (1)–(4) above, there exists a contrast between two discursive segments with two different polarities, one of which is missing. Now, concerning the Polarity Particles (PolParts) si/non, the question that must be addressed is: Since they appear along with the dm pourtant, what is the element that conveys this contrast? Is it the dm pourtant or the PolPart? A related question is: How can the presence of non in (13a) and of its absence in (13b) be accounted for?

Is the information conveyed in (13a) and (13b) the same? More specifically, are the antecedents of the sequences et pourtant and et pourtant non identical?

This paper is an attempt to answer these questions, and it will make the following claims:

∙ The missing constituent following the sequence et pourtant si/non can be recovered and interpreted either as a case of ellipsis or propositional anaphora.

∙ Although the dm pourtant is not itself a modal, it appears to express a contrast between two modal expressions whose modal forces are ‘polar opposites’ given that they operate on different modal bases.Footnote [5] In the sequence et pourtant si/non the semantic contents of two discourse segments,

$S_{0}$ and

$S_{0}$ and  $S_{1}$, are given by the PolParts as they license this dm.

$S_{1}$, are given by the PolParts as they license this dm.∙ Polparts are instances of Verum Focus (from now on vf), in so far as they emphatically express the polarity of a proposition. They also express a semantic contrast between two propositions with contrasted polarity.

∙ The relevant antecedents of et pourtant si/non are propositions in the scope of an intensional operator, or in some cases, propositions in a modal context.

Thus, the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 is a description of the relevant properties of the dm pourtant. It is also argued there that PolParts si/non are emphatic elements in contexts such as those in (1)–(4), and a discussion follows about the free variation between si and oui. I then highlight the main differences between two approaches to vf, the focus approach and the non-focus approach. Section 3 discusses the status of the recovered elements in constructions involving et pourtant si/non as an instance of TP-Ellipsis or propositional anaphora. In Section 4, I will then be in a position to formulate my proposal based on vf and alternatives. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2 Pourtant , polparts and verum focus: an overview

This section presents a review of pourtant and PolParts clarifying their relevant properties. It also reviews the basic facts about Verum Focus that will be the plank of the treatment proposed in Section 4.

2.1 Pourtant as discourse marker

There is extensive literatureFootnote [6] on the dm pourtant, and I will not attempt to provide a comprehensive analysis. My purpose here is primarily to bring to light the significant properties of this dm. Syntactically, pourtant establishes a link between two elements, which very often express propositionsFootnote [7] and it may appear with connectives et (and) (cf. supra (1)–(4)) and mais (but) (Gettrup & Nølke Reference Gettrup and Nølke1984). Semantically, pourtant has been considered as a genuine concessive dm, for instance in Morel (Reference Morel1996: p. 52). In such contexts, dms cependant (however) or néanmoins (nevertheless) can be substituted to pourtant. Anscombre (Reference Anscombre2002) analyzes et in the sequence et pourtant as an opposition marker between two parts of an argumentation (Anscombre & Ducrot Reference Anscombre and Ducrot1983, Anscombre Reference Anscombre1983). Central to this approach is the fact that there are two types of counter-argumentation, direct and indirect.Footnote [8] Let ![]() $p$ connec

$p$ connec ![]() $q$ be a discursive sequence, where

$q$ be a discursive sequence, where ![]() $p$ is the antecedent and

$p$ is the antecedent and ![]() $q$ the consequent, and connec the connective linking them. There is an indirect counter-argumentation between

$q$ the consequent, and connec the connective linking them. There is an indirect counter-argumentation between ![]() $p$ and

$p$ and ![]() $q$ when

$q$ when ![]() $q$ is an argument for a conclusion

$q$ is an argument for a conclusion ![]() $r$ and

$r$ and ![]() $p$ an argument for

$p$ an argument for ![]() $\neg r$. In a direct counter-argumentation,

$\neg r$. In a direct counter-argumentation, ![]() $p$ is an argument for

$p$ is an argument for ![]() $\neg q$. These types explain one of the differences between mais (but) and pourtant (yet): whereas mais is appropriate in both types of counter-argumentation (14a), pourtant (yet) is only licit in contexts of direct counter-argumentation (14b).Footnote [9]

$\neg q$. These types explain one of the differences between mais (but) and pourtant (yet): whereas mais is appropriate in both types of counter-argumentation (14a), pourtant (yet) is only licit in contexts of direct counter-argumentation (14b).Footnote [9]

In (14a), ![]() $p$ is an argument for 〈smoking,cough〉, which is directly opposed to

$p$ is an argument for 〈smoking,cough〉, which is directly opposed to ![]() $q$: 〈smoking, do not cough〉. In (14b), however, the argumentation is indirect since

$q$: 〈smoking, do not cough〉. In (14b), however, the argumentation is indirect since ![]() $p$ is oriented toward a conclusion

$p$ is oriented toward a conclusion ![]() $r$: 〈I shall take dessert〉 whereas

$r$: 〈I shall take dessert〉 whereas ![]() $q$ is oriented toward

$q$ is oriented toward ![]() $\neg r$: 〈I shall not take dessert〉.

$\neg r$: 〈I shall not take dessert〉.

In the Gettrup & Nølke (Reference Gettrup and Nølke1984) approach, ![]() $p$ et pourtant

$p$ et pourtant ![]() $q$ expresses that

$q$ expresses that ![]() $p$ is not well founded (

$p$ is not well founded (![]() $p$ is true/correct but it should not be, because

$p$ is true/correct but it should not be, because ![]() $q$). For these authors, pourtant denotes a strong opposition, in which the assertion of

$q$). For these authors, pourtant denotes a strong opposition, in which the assertion of ![]() $q$ is highly unexpected. They conclude then that the existing contradiction between

$q$ is highly unexpected. They conclude then that the existing contradiction between ![]() $p$ and

$p$ and ![]() $q$ seems to convey the information that the main speaker’s goal is to reject

$q$ seems to convey the information that the main speaker’s goal is to reject ![]() $p$ (e.g. if someone asserts that

$p$ (e.g. if someone asserts that ![]() $q$, and entails that it contradicts

$q$, and entails that it contradicts ![]() $p$, then the speaker believes that

$p$, then the speaker believes that ![]() $p$ is false).

$p$ is false).

These approaches however, raise two important theoretical issues. First, both approaches rely heavily on the type of argumentative relation between ![]() $p$ and

$p$ and ![]() $q$ (and in some cases in connection with a conclusion

$q$ (and in some cases in connection with a conclusion ![]() $r$) in a discourse of type

$r$) in a discourse of type ![]() $p$ (et) pourtant

$p$ (et) pourtant ![]() $q$. Now, in examples such as those in (1)–(10),

$q$. Now, in examples such as those in (1)–(10), ![]() $q$ is missing and must be recovered. Consequently, in order to know the argumentative orientation that is obtained between

$q$ is missing and must be recovered. Consequently, in order to know the argumentative orientation that is obtained between ![]() $p$ and

$p$ and ![]() $q$ the context of

$q$ the context of ![]() $q$ must be accessible. In these examples,

$q$ must be accessible. In these examples, ![]() $q$ is anaphorically dependent on

$q$ is anaphorically dependent on ![]() $p$, more specifically on a part of

$p$, more specifically on a part of ![]() $p$. Hence, all potential antecedents are not appropriate and the argumentative orientation can be established only after reconstruction.

$p$. Hence, all potential antecedents are not appropriate and the argumentative orientation can be established only after reconstruction.

The second problem is that of denials. In Roulet et al. (Reference Roulet, Auchlin, Moeschler, Rubattel and Schelling1985: pp. 141–142) or Anscombre (Reference Anscombre1983: p. 70), it is argued that in factual readings,Footnote [10] pourtant is not compatible with the presence of the connective et (and). In support of their claim, Anscombre & Ducrot (Reference Anscombre and Ducrot1983: p. 89) give the following example:

Anscombre & Ducrot (Reference Anscombre and Ducrot1983: pp. 89–90) observe that this example is ambiguous between two readings. In one reading, speaker ![]() $B$ means to point to a contradictory fact: even though Pierre failed the exam, he does not seem affected, giving rise to the conclusion that Pierre is psychologically strong or careless. In another reading,

$B$ means to point to a contradictory fact: even though Pierre failed the exam, he does not seem affected, giving rise to the conclusion that Pierre is psychologically strong or careless. In another reading, ![]() $B$’s observation entails that

$B$’s observation entails that ![]() $A$ is wrong and that Pierre (probably) passed his exam. This reading corresponds to a factual refutation or denial in Anscombre (Reference Anscombre1983: pp. 70–71)Footnote [11] and in these contexts, et pourtant is infelicitous, whereas mais pourtant (but yet) is allowed, as exhibited by example (17) below:

$A$ is wrong and that Pierre (probably) passed his exam. This reading corresponds to a factual refutation or denial in Anscombre (Reference Anscombre1983: pp. 70–71)Footnote [11] and in these contexts, et pourtant is infelicitous, whereas mais pourtant (but yet) is allowed, as exhibited by example (17) below:

Now, following Anscombre & Ducrot (Reference Anscombre and Ducrot1983) and Anscombre (Reference Anscombre1983), if in factual refutation or denial contexts et pourtant is infelicitous, the sequence et pourtant si/non should be infelicitous too, since this sequence rejects a proposition in a given context. However, this is not the case. The same discourse with et pourtant non is perfect and furthermore, the ambiguity disappears making it clear that Pierre did not fail his exam:

This is evidence of the connection between pourtant and modality.Footnote [12] Although Jayez (Reference Jayez1988, Reference Jayez, Beyssade, Bonami, Hofherr and Corblin2003) and Martin (Reference Martin1987) do not deal with et pourtant si/non explicitly, they introduce the tool of modalization that I deem relevant for the analysis of et pourtant si/non proposed now: pourtant as assimilated to a modal operator that brings a discourse contrast.

In this analysis, the discursive antecedents of et pourtant si/non are considered as sequences under the scope of a modalized predicate (a case of modal subordination for Roberts (Reference Roberts1989, Reference Roberts, Yoon and Kathol1996)).Footnote [13] If the antecedent of et pourtant must be in a modal context, the question that arises is: Are (18a) and (18b) equivalent?

In the next section, I will argue that they are not equivalent. I will also show that PolParts are used emphatically and introduce verum (Höhle Reference Höhle and Jacobs1992), acting as common ground management.

2.2 Emphatic PolParts

In this section, I examine the contrasts between (19a,b) on the one hand and (20a,b) on the other.

In (19a,b) both occurrences of et pourtant and et pourtant non are possible and yet the missing part after et pourtant in (19a) and (19b) is not identical:

Even though the propositional content can be recovered without the presence of PolPart non, it differs in (19a) and (19b): in (19b) the context is intensional, whereas in (19a) the PolPart asserts the negation of the proposition embedded in the antecedent. Furthermore, as a contrast relation is a scalar relation, in (19b) the contrast is ‘weaker’ than in (19a). That is, the speaker in (19b) does not wish to commit himself to whether the antecedent is true or not, leaving its interpretation open. It can be observed that with et pourtant factual antecedents are licit, whereas et pourtant si/non requires an intensional environment, be it explicit or implicit:

In examples (21a,b) et pourtant and et pourtant non are not interchangeable: et pourtant is appropriate in (21a) but et pourtant non in (21b) brings to light a logical contradiction.Footnote [15]

Some significant consequences follow readily from the examples above as regards the differences between et pourtant and et pourtant si/non. The reconstruction of et pourtant is achieved via the implicit content (hence the numerous interpretative options) whereas et pourtant si/non only allows either a positive interpretation or its negative counterpart. These sequences do not convey the same information and therefore do not carry the same degree of certainty. One may express this roughly as:

We now turn to (20a,b). In (20b), there is first emphasis on the polarity of the assertion and second on the presence of a propositional content that conveys background information. The PolPart si can thus be appropriately regarded as the exponent of an emphatic assertion.Footnote [16] The following example illustrates this:

In (22A), ![]() $S$ conveys emphasis on the truth of the proposition ‘elle viendra à la soirée’ (she will turn up at the party) whereas in (22A’),

$S$ conveys emphasis on the truth of the proposition ‘elle viendra à la soirée’ (she will turn up at the party) whereas in (22A’), ![]() $S$ does not. Furthermore, contrary to (22), the sequence we study here needs some kind of information formerly introduced in the discourse whose polarity is denied.Footnote [17] All other alternative propositions in the discourse are then canceled.

$S$ does not. Furthermore, contrary to (22), the sequence we study here needs some kind of information formerly introduced in the discourse whose polarity is denied.Footnote [17] All other alternative propositions in the discourse are then canceled.

The label Verum Focus (vf) or polarity focus (Höhle Reference Höhle and Jacobs1992) captures the informal intuition associated with emphasis: these terms refer to the fact that a sentence polarity is highlighted without changing its truth conditions. In (20b), the missing proposition has already been mentioned, but its content has not yet been asserted as it is in the scope of a modal operator (in an intensional context). In other words, the discourse fragment is presented as a possibility and subsequently is not considered as part of the background: et pourtant si/non is a way of emphasizing a proposition ![]() $p$ that is discursively salient and strongly asserted, although they are not prosodically focalized expressions. Following Laka (Reference Laka1990), we consider that negative markers such as non license a zero constituent

$p$ that is discursively salient and strongly asserted, although they are not prosodically focalized expressions. Following Laka (Reference Laka1990), we consider that negative markers such as non license a zero constituent ![]() $\emptyset$. Laka analyzes these markers as polarity markers heading a Polarity category (

$\emptyset$. Laka analyzes these markers as polarity markers heading a Polarity category (![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F4}$P) as illustrated below, in which

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F4}$P) as illustrated below, in which ![]() $\emptyset _{i}$ is an accessible constituent in the discourse:

$\emptyset _{i}$ is an accessible constituent in the discourse:

The analysis of the semantic contribution of PolParts is provided in Section 3. I must first discuss the free variation between si and oui and second, present a detailed analysis of vf.

2.3 Free variation between si and oui

The so-called response particles oui, si and non Footnote [18] have traditionally been considered as markers of agreement or disagreement with a proposition previously expressed. Oui expresses agreement with a positive question, si shows that there is disagreement with a negative question and non is a way of expressing either agreement if uttered as an answer to a negative question or disagreement if it follows a positive question. However, this is inadequate. Plantin (Reference Plantin1982: p. 263) points out that in negative contexts oui is sometimes possible. This is the case when it expresses agreement, contrary to si, which expresses the refutation of an assertion.

Examples of this are given in (23):

In (23Y,Y’) both oui and non express agreement with ![]() $x$’s negative assertion. However, they semantically differ in that oui asserts

$x$’s negative assertion. However, they semantically differ in that oui asserts ![]() $\neg p$, whereas non refutes

$\neg p$, whereas non refutes ![]() $p$. Only (23Y”) expresses disagreement with

$p$. Only (23Y”) expresses disagreement with ![]() $x$’s assertion in rejecting

$x$’s assertion in rejecting ![]() $\neg p$,

$\neg p$, ![]() $p$ representing the proposition ‘ce mur n’est pas blanc’ (this wall is not white).

$p$ representing the proposition ‘ce mur n’est pas blanc’ (this wall is not white).

Roelofsen & Farkas (Reference Roelofsen and Farkas2015) propose a classification of the distribution of response particles based on binary features. Whatever the value of the assertion, be it positive or negative, response particles may express two types of polarity. First, they may express absolute polarity, that is the polarity (positive or negative) of the answer, in which case their representation contains the features [+] or [-], and second, relative polarity in a system based on agreement/disagreement (depending on whether the polarity of the answer is similar or not with the proposition asserted). In the latter case, the semantic representation of a response particle contains the features [agree] or [reverse]. These sets of features can combine to form the following combinations in (24):

Then oui is a realization of [+], non a realization of [-] and si a realization of [reverse,+].

In Authier (Reference Authier2013: p. 348), the following possibilities for polarity particles oui/si/non in French are illustrated as follows:

However, one can observe that et pourtant oui is licit in contexts where si would be expected, that is when the antecedent is syntactically negative. This is exemplified in (28) below:

Several studies on contemporary French noticed that French native speakers move toward oui rather than si for syntactically negative preceding utterances (Wilmet Reference Wilmet1976, Plantin Reference Plantin1982, Kerbrat-Orecchioni Reference Kerbrat-Orecchioni2001, Hansen Reference Hansen2018).Footnote [19]

Recently, Pasquereau (Reference Pasquereau2017) pointed out that the same thing goes with embedded PolParts. These PolParts require agreement or disagreement (in case of disagreement, the polarities of the two discursive segments are different, which triggers the occurrence of an adversative marker such as mais (but)). Furthermore, Pasquereau argues that oui can become a strong Positive Polarity Item (from now on ppi) equivalent to si under particular discursive conditions. For instance, in (29), following Roelofsen & Farkas (Reference Roelofsen and Farkas2015), si is expected and oui should be ruled out as the antecedent is negative:

The representation proposed by Roelofsen & Farkas (Reference Roelofsen and Farkas2015) does not integrate the fact that the negative orientation of the antecedent can be either explicit or implicit. Furthermore, even if the antecedent is not negative oriented, there may be free variation between si and oui as exemplified in (30):

These examples are problematic for Roelofsen & Farkas (Reference Roelofsen and Farkas2015) as assigning the features [agree,+] to oui is tantamount to saying that oui and its antecedent share the same polarity. Among his conclusions, Pasquereau (Reference Pasquereau2017) argues that:

[…] embedded Polar Response Particles in French can be analyzed as always requiring that the utterance they are in contrast with the utterance that their antecedent is in.

What is highly relevant here is the contrast condition on PolParts. This phenomenon was clearly formalized by Authier (Reference Authier2013) for ellipsis in non-embedded contexts:

Authier concludes that in ellipsis contexts, the polarity marker si does not instantiate the feature [reverse] but rather is used:

‘to express the contrastive (rather than contradictory) nature of the polarity of the conjunct that hosts it relative to that expressed by the first conjunct’ (Authier Reference Authier2013: p. 365)

In order to capture this fact, Authier establishes two conditions for contrastive polarity ellipsis as that in (32): (i) access to a quaestio, which provides the positive expected alternative as antecedent for the ellipsis conjunct, and (ii) mais (but) licenses contrastive polarity in conjunctions. Thus, (31) is analyzed as in (32)Footnote [20]

The same goes for example (33) below:

In accordance with Authier (Reference Authier2013) for ellipsis contexts and Pasquereau (Reference Pasquereau2017) for embedded PolPArts, constructions with et pourtant si/non provide additional evidence that PolParts have a contrastive function in assertive contexts. What is relevant in these sequences is a semantic contrast and not a reaction to assertions. Put differently, the disagreement about two propositions is expressed by polarity opposition, and it is this disagreement that licenses pourtant.

2.4 Verum Focus

The facts presented above (Section 2.2) provide support for the view that PolParts emphasize the polarity of a sentence. Thus, a PolPart can be considered as an exponent of vf. From this point of view, si/non is akin to the process of do-support in English (Wilder Reference Wilder2013). The first author who identified vf was Höhle (Reference Höhle and Jacobs1992). Lohnstein (Reference Lohnstein, Féry and Ishihara2016) notes that Höhle considers vf as a predicate rather than as an illocutionary operator. Putting to rest the hypothesis that vf could be an illocutionary operator, Höhle analyzes vf as a truth predicate (i.e. ‘it is true that’)Footnote [21] that has scope over a proposition. In declarative sentences, vf asserts the truth value of a proposition, and as noted in Gutzmann & Castroviejo (Reference Gutzmann, Castroviejo, Bonami and Hofherr2011), the position verum can be instantiated by various types of lexical material depending on languages as exemplified in (34) below, with English, Spanish or French (34B2,B3,B4) respectively:

According to Höhle, filling the position verum is a way of stressing that the content expressed in a proposition ![]() $p$ is true: consequently, Gutzmann & Castroviejo (Reference Gutzmann, Castroviejo, Bonami and Hofherr2011: p. 151) propose the following semantics for verum:

$p$ is true: consequently, Gutzmann & Castroviejo (Reference Gutzmann, Castroviejo, Bonami and Hofherr2011: p. 151) propose the following semantics for verum:

Several approaches are taken in order to account for vf. In a review of the literature, Gutzmann, Hartmann & Matthewson (Reference Gutzmann, Hartmann and Matthewsonsubmitted) consider two of these approaches, vf as an instance of focus (this is the focus accent thesis (fat)) (Wilder Reference Wilder2013, Samko Reference Samko2016, McCloskey Reference McCloskey, Aboh, Puskàs and Shönenberger2017, Goodhue Reference Goodhue2018) and vf as a lexical operator introduced at LF (this is the lexical operator thesis (lot)) (Romero & Han Reference Romero and Han2004, Gutzmann & Castroviejo Reference Gutzmann, Castroviejo, Bonami and Hofherr2011, Gutzmann et al. Reference Gutzmann, Hartmann and Matthewsonsubmitted). Gutzmann et al. (Reference Gutzmann, Hartmann and Matthewsonsubmitted) summarize the fat and the lot in (35) and (36), respectively:

∙ [fat thesis] (Gutzmann et al. Reference Gutzmann, Hartmann and Matthewsonsubmitted: pp. 5–6)

∙ [lot thesis] (Gutzmann et al. Reference Gutzmann, Hartmann and Matthewsonsubmitted: p. 41)

I discuss these two approaches below and briefly assess them.

2.4.1 Focus account

Theoretical accounts in which vf is analyzed in terms of focus claim that the syntactic head of a sentence is marked by a Polarity Focus (pf) (Laka (Reference Laka1990), cf. Section 2.1). Wilder (Reference Wilder2013) argues that pf requires the presence of a salient polarity antecedent in the alternative proposition to the proposition containing pf. However, pf cannot be used ‘out of the blue’, and other discursive factors constrain its distribution, among which, the fact that ![]() $p$ must be given.Footnote [24] As stated in Wilder (Reference Wilder2013: p. 154) in connection with emphatic do:

$p$ must be given.Footnote [24] As stated in Wilder (Reference Wilder2013: p. 154) in connection with emphatic do:

The proposition expressed by the antecedent utterance is not (necessarily) a focus alternative of the do-clause. Rather, the antecedent utterance, together with the rest of the discourse context, evokes a set of alternative propositions [![]() $p,\neg p$], one of which is the proposition expressed by the do-clause. This alternative set can be conceived of as corresponding to the meaning of a yes–no question, which the affirmative emphatic do assertion answers, eliminating its negative alternative.

$p,\neg p$], one of which is the proposition expressed by the do-clause. This alternative set can be conceived of as corresponding to the meaning of a yes–no question, which the affirmative emphatic do assertion answers, eliminating its negative alternative.

Samko (Reference Samko2016) provides a formal account of pf using Rooth’s alternative semantics (Rooth Reference Rooth, Hestvik and Berman1992a, Reference Roothb)Footnote [25] that adds a presuppositional operator ![]() ${\sim}$ at LF.Footnote [26] Samko (Reference Samko2016: pp. 119–120) claims that ‘the discourse conditions for sentences with focused S and a propositional-level

${\sim}$ at LF.Footnote [26] Samko (Reference Samko2016: pp. 119–120) claims that ‘the discourse conditions for sentences with focused S and a propositional-level ![]() ${\sim}$ are met only if there is an accessible antecedent for that sentence that has the same propositional content with the exception of polarity’. Samko’s example is given in (37):

${\sim}$ are met only if there is an accessible antecedent for that sentence that has the same propositional content with the exception of polarity’. Samko’s example is given in (37):

The embedded clause he did not raise taxes is an appropriate antecedent as it is a member of the focus value of did (![]() $\neg p$ and

$\neg p$ and ![]() $p$ each represent an alternative value for the other).

$p$ each represent an alternative value for the other).

This example illustrates the fact emphasized by Samko (Reference Samko2016: p. 133) that the antecedents for vf are often non-finite (e.g. complements of intensional verbs) or modals. However, vf does not necessarily require that it matches the form of its antecedent (as in (37)) as it is rather identified as a polar question in the discursive context.

The approach taken by Goodhue (Reference Goodhue2018) is in the line of focus-based approaches proposed by Wilder (Reference Wilder2013) and Samko (Reference Samko2016), where the polarity of a sentence (+,–)Footnote [27] heads the PolP. Goodhue proposes the condition below:

PF licensing condition: (Goodhue Reference Goodhue2018: p. 57)

Polarity focus is licensed by contrast between the pf utterance and a focus alternative with opposite polarity salient in the context.

In other words, pf is felicitous only if a discursive antecedent is salient. The emphatic effect on the truth value of a proposition ![]() $p$ is the result of the pragmatic implication that

$p$ is the result of the pragmatic implication that ![]() $\neg p$ (the alternative with opposite polarity) is false, thereby creating a contrast between the two propositions: one is asserted and the other is rejected. This analysis is akin to that of Gutzmann et al. (Reference Gutzmann, Hartmann and Matthewsonsubmitted) (cf. 2.4.2). However, in Goodhue’s analysis, the emphatic effect of the pf is the truth of a proposition. Two other points are worth noticing: first the focus introduces the presupposition (in the sense of Rooth (Reference Rooth1992b)) that a salient antecedent is necessary, and second the emphatic effect results from both the marked focus and the implication that alternative proposition is false, hence the contrast.Footnote [28]

$\neg p$ (the alternative with opposite polarity) is false, thereby creating a contrast between the two propositions: one is asserted and the other is rejected. This analysis is akin to that of Gutzmann et al. (Reference Gutzmann, Hartmann and Matthewsonsubmitted) (cf. 2.4.2). However, in Goodhue’s analysis, the emphatic effect of the pf is the truth of a proposition. Two other points are worth noticing: first the focus introduces the presupposition (in the sense of Rooth (Reference Rooth1992b)) that a salient antecedent is necessary, and second the emphatic effect results from both the marked focus and the implication that alternative proposition is false, hence the contrast.Footnote [28]

2.4.2 Non-focus account

Romero & Han (Reference Romero and Han2004) analyze verum in polar questions as an epistemic conversational operator ‘used not to assert that the speaker is entirely certain about the truth of ![]() $p$, but to assert that the speaker is certain that

$p$, but to assert that the speaker is certain that ![]() $p$ should be added to the Common Ground (cg)Footnote [29], (Romero & Han Reference Romero and Han2004: p. 627). The semantics of verum is then as in (38) below:Footnote [30]

$p$ should be added to the Common Ground (cg)Footnote [29], (Romero & Han Reference Romero and Han2004: p. 627). The semantics of verum is then as in (38) below:Footnote [30]

This semantics expresses that there is a partition between [verum ![]() $p$,

$p$, ![]() $\neg$verum

$\neg$verum ![]() $p$] when the speaker holds a belief prior to expressing the truth or falseness of

$p$] when the speaker holds a belief prior to expressing the truth or falseness of ![]() $p$ and that this belief is contradicted. Otherwise, there would be no point in emphasizing the certainty of this belief. For instance,

$p$ and that this belief is contradicted. Otherwise, there would be no point in emphasizing the certainty of this belief. For instance,

Gutzmann & Castroviejo (Reference Gutzmann, Castroviejo, Bonami and Hofherr2011) analyze vf as a ‘use-conditional operator’ the nature of which is not semantic (the truth conditions of the proposition are not changed) but conversational as it updates ![]() $?p$ of the qud. In doing so, the speaker emphasizes the truth of

$?p$ of the qud. In doing so, the speaker emphasizes the truth of ![]() $p$, that is, the pragmatic effect resulting from the speaker’s wish to update

$p$, that is, the pragmatic effect resulting from the speaker’s wish to update ![]() $?p$ using an operator added to the assertion of

$?p$ using an operator added to the assertion of ![]() $p$:

$p$:

Gutzmann & Castroviejo (Reference Gutzmann, Castroviejo, Bonami and Hofherr2011) agree that (40) has the same effects as a focus-based approach (i.e. a verum-marked utterance is an answer to a question it is an antecedent of (cf. Section 2.4.1)). In order to restrict the semantics of verum, Gutzmann et al. (Reference Gutzmann, Hartmann and Matthewsonsubmitted: p. 42) increase the attitudinal role of the speaker in the form of a wish to downdate the qudFootnote [31] (following Gutzmann & Castroviejo (Reference Gutzmann, Castroviejo, Bonami and Hofherr2011)), yielding the semantics expressed in (36).

I address now the theoretical issue of whether et pourtant si/non is a case of TP-Ellipsis or propositional anaphora.

3 TP-ellipsis or propositional anaphora?

3.1 English vs German

Before providing a detailed theoretical consideration of the anaphoric nature of et pourtant si/non, a brief analysis of the German data is in order.Footnote [32] German (11), repeated here in (41) for the sake of commodity, is a case of propositional anaphora:

In (41), the semantic content of the sequence Das war aber nicht der Fall (that was not the case) is the proposition under the scope of the propositional attitude verb denkt (believe) and (41) is then a case of propositional anaphora. This phenomenon is also illustrated by (42) and (43) below:

Krifka (Reference Krifka and Snider2013) claims, contra Kramer & Rawlins (Reference Kramer, Rawlins, Lima, Mullin and Smith2011),Footnote [33] that PolParts yes/no are propositional anaphors that pick up propositional discourse referents, thus behaving like that or so. He also notices that there are other ways of reacting to an assertion, such as maybe, sometimes, right, wrong etc. He concludes that yes/no are anaphors that pick up propositional discourse referents connected to speech acts.Footnote [34] PolParts are then assigned to the syntactic category ActP and indicate the speaker’s commitment to the proposition asserted. The semantics suggested by Krifka accounts for the difference between English and German in the following way:

In German, Ja (yes) picks up a propositional discourse referent that will be asserted, whereas in English yes/no the assertion is part and parcel of their meaning. German doch (French si) requires the presence of a negated propositional referent in the discursive context. This presupposes the presence of two salient propositional discourse referents, one being the negation of the other, and doch taking up the non-negated referent and asserting it. Gutzmann (Reference Gutzmann, Bayer and Struckmeier2017: p. 167) analyzes ja as ‘a typical example of a propositional particle. It combines with a proposition and yields an independent use-conditional comment to it without changing the rest of the propositional content’,Footnote [35] as illustrated by (44).

I now turn to the study of the anaphoric status of et pourtant si/non using relevant diagnostics to decide whether et pourtant si/non is a case of TP-ellipsis or propositional anaphora.

3.2 Diagnostics

Since Hankamer & Sag (Reference Hankamer and Sag1976), it has generally been admitted that TP-ellipsis and propositional anaphora differ in that the former allows extraction out of the ellipsis site, whereas the latter does not. Another well-known test for distinguishing them is the so-called Missing Antecedent Test (Hankamer & Sag Reference Hankamer and Sag1976, Grinder & Postal Reference Grinder and Postal1971, Bresnan Reference Bresnan1971). We will consider here two other diagnostics: cataphoric anaphora and quantifier inversion (Cecchetto & Percus Reference Cecchetto, Percus and Frascarelli2006).Footnote [36]

extraction

Extraction out of ellipsis site is licit for TP-Ellipsis, and it is impossible for propositional anaphora:

From (45b,c), it can be concluded that et pourtant si is neither a case of TP-Ellipsis nor propositional anaphora.Footnote [37]

missing antecedent phenomenon (map)

Consider (46) in which he picks up its antecedent from the ellipsis site:

In (46), he introduces a new entity, which cannot be identified from the antecedent but it has to be recovered from the target clause. This criterion, first presented in Grinder & Postal (Reference Grinder and Postal1971: p. 278), was discussed by Bresnan (Reference Bresnan1971), who argues that some antecedents in null-complement contexts can be analyzed as the conjunction of three factors: lexical semantics, discourse and intensional (modal) contexts. Modality is thus relevant in that a modal context can license VPE-like effects, such as missing antecedent, which can occur even in constructions that behave like null-complement anaphora otherwise. The example in (47) illustrates this phenomenon:

We have observed that even in modal contexts, there is no agreement among our informants about the acceptance of (47), but all our informants readily accepted sentences in (48):

As et pourtant si passes the missing antecedent test only partially, it can be concluded that it is either a case of TP-Ellipsis or propositional anaphora.Footnote [38]

cataphoric reference

Cataphoric reference is allowed when PolParts are involved in TP-ellipsis (49a), but is impossible with et pourtant si/non constructions (49b):

Examples in (49) suggest then that et pourtant si/non is neither a case of TP-Ellipsis nor propositional anaphora.

quantifier order

Cecchetto & Percus (Reference Cecchetto, Percus and Frascarelli2006) observe that in a sentence like (50), the elliptical part (50a) and its non-elliptical counterpart (50b) both can receive two readings, depending on the order of quantifiers:

They also observe that in propositional anaphora, there is only one possible reading as illustrated in (51):

In (51), the reading in which all planes have been inspected by technicians is ruled out. The same goes for the French counterparts of (50) and (51) illustrated in (52):

Interestingly, et pourtant si/non allows both readings. This is illustrated in (53a,b) below:Footnote [39]

This is not unexpected as in (50) or (51), the antecedent is the VP, which excludes the subject constituent from possible antecedent candidates, whereas in (53) et pourtant si relates to the whole proposition. What is common in both cases is that whatever the interpretation chosen, it must be picked up by the anaphoric element, satisfying a parallelism requirement (Darlrymple, Shieber & Pereira Reference Darlrymple, Shieber and Pereira1991, Fox Reference Fox2000, Asher et al. Reference Asher, Hardt and Busquets2001, Merchant Reference Merchant2001).Footnote [40] Although two interpretations are possible in the examples in (54),Footnote [41] a continuation of the sentence can disambiguate between the two readings as illustrated in (54) below:

Regarding quantifier inversion, et pourtant si/non can be either a case of TP-Ellipsis or propositional anaphora.

All this can be summed up in Table 1:

Table 1 Tests for ‘et pourtant si/non’.

The result of the discussion of this section is that it appears that et pourtant si/non can make use of either TP-Ellipsis or propositional anaphoraFootnote [42] strategy. There is an interesting parallelism with the arguments presented too in Authier (Reference Authier2011) regarding modal ellipsis in French, also allowing both processes.Footnote [43]

Interestingly, in Serbo-Croatian there is no equivalent for et pourtant si/non. Two strategies are used there: either ellipsis (55) or the equivalent for anaphoric so (56):Footnote [44]

This array of facts suggests that et pourtant si/non can make use of either strategy: TP-Ellipsis or propositional anaphora. My proposal can now be worked out through in some detail.

4 The proposal

4.1 Assumptions

Wilder (Reference Wilder2013), Samko (Reference Samko2016) and Goodhue (Reference Goodhue2018) argue that a polar question ![]() $?p$ is the explicit or implicit antecedent of pf. In the same line of thought, Gutzmann et al. (Reference Gutzmann, Hartmann and Matthewsonsubmitted: p. 42) argue that: ‘If a speaker uses verum to explicitly mark that she wants to prevent that the qud is settled toward

$?p$ is the explicit or implicit antecedent of pf. In the same line of thought, Gutzmann et al. (Reference Gutzmann, Hartmann and Matthewsonsubmitted: p. 42) argue that: ‘If a speaker uses verum to explicitly mark that she wants to prevent that the qud is settled toward ![]() $\neg p$, then

$\neg p$, then ![]() $\neg p$ should already have been proposed (by an utterance of

$\neg p$ should already have been proposed (by an utterance of ![]() $\neg p$, for instance) or, at least, this possibility should have been raised in the discourse context (by a biased question, for instance)’. This makes a correct prediction in a dialogue like that in (57) but does not account for (58):

$\neg p$, for instance) or, at least, this possibility should have been raised in the discourse context (by a biased question, for instance)’. This makes a correct prediction in a dialogue like that in (57) but does not account for (58):

Thus, it is not the qud or even its orientation that is relevant in the occurrence of et pourtant si/non but what is relevant is the fact that the antecedent is intensional, hence the possibility of the positive or negative orientation of the question. In (57), the speaker of ![]() $Q$ carries an epistemic bias toward

$Q$ carries an epistemic bias toward ![]() $p$ (is satisfied).Footnote [45]

$p$ (is satisfied).Footnote [45]

The sequence et pourtant si/non updates the qud with ![]() $\neg p$. This inference is missing in (58), where the question evokes a couple of alternatives [

$\neg p$. This inference is missing in (58), where the question evokes a couple of alternatives [![]() $p,\neg p$] (i.e. you are satisfied, you are not satisfied). The Romero & Han (Reference Romero and Han2004) proposal suggests that the representation for (58) is as follows:

$p,\neg p$] (i.e. you are satisfied, you are not satisfied). The Romero & Han (Reference Romero and Han2004) proposal suggests that the representation for (58) is as follows:

Consider the following dialogue in (60):

I thus claim that the function of et pourtant si/non is not so much to evoke the qud as to update the cg via two states of belief that are not contradictory.

As already noticed (Section 2.2), the main difference between et pourtant and et pourtant si/non is that the former simply expresses what is possible, whereas the latter emphasizes the truth of a propositional content. Now the sequence et pourtant si/non instantiates some missing material in which only PolParts represent the new information. Consequently, a linguistic antecedent explicitly realized in the discourse is necessary so as to give the given Footnote [46] status to a propositional content. This is the way in which si/non updates the background (Stalnaker Reference Stalnaker2002) and this is the reason why et pourtant si/non is infelicitous ‘out of the blue’:

Only antecedents under the scope of a modal verb or in an intensional environment license et pourtant si/non (cf. Section 2.4.2). Consider (62):

In accordance with Wilder (Reference Wilder2013), I argue that the proposition expressed by the antecedent of et pourtant si/non, together with the discursive context, evokes a set of alternative propositions. Contrary to most approaches, I contend that resorting solely to an answer to the qud fails to countenance the requirements of the environment of this type of construction. A finer-grained approach of anaphoric contexts, including PolParts, as introduced by Hardt & Romero (Reference Hardt and Romero2004) seems more relevant, both empirically and conceptually. More specifically, Hardt & Romero (Reference Hardt and Romero2004) distinguish between the contrast brought about by a polarity focus and that brought about by a modal-like operator verum, whose meaning is ‘it is true that’ or ‘it is for sure that’.Footnote [47] The difference lies in the emphasized element and in the set of alternatives. Additionally, Hardt & Romero (Reference Hardt and Romero2004) also point out that among the two sets of alternatives generated by the focalized auxiliary (did, didn’t), the polarity set is more economical (i.e. its interpretation is the default interpretation) as the verum operator requires a more complex environment. More specifically, the operator verum is chosen in contexts in which there is an epistemic bias, and typically, in the constructions analyzed in this paper, a modalized element is present in one of two discursive segments biased by the pourtant marker defined as follows:

pourtant and modalization

[[pourtant ![]() $(S_{0},S_{1})$ ]] = discourse contrast between

$(S_{0},S_{1})$ ]] = discourse contrast between ![]() $S_{0}$ et

$S_{0}$ et ![]() $S_{1}$ such that a proposition

$S_{1}$ such that a proposition ![]() $p$ is associated to

$p$ is associated to ![]() $S_{0}$, anchored in a possible world (or state or belief)

$S_{0}$, anchored in a possible world (or state or belief) ![]() $w$, and a proposition

$w$, and a proposition ![]() $q$ associated to

$q$ associated to ![]() $S_{1}$, anchored in a possible world (or state of belief)

$S_{1}$, anchored in a possible world (or state of belief) ![]() $w^{\prime }$, and

$w^{\prime }$, and ![]() $q$ non-monotonically entails

$q$ non-monotonically entails ![]() $\neg p$ (

$\neg p$ (![]() $q\mid \backsim \neg p$).Footnote [48]

$q\mid \backsim \neg p$).Footnote [48]

I thus assume that PolParts si/non in the sequence et pourtant si/non introduce a discursive segment ![]() $S_{1}$ in which a missing content

$S_{1}$ in which a missing content ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ has to be anaphorically recovered from an adequate antecedent in the same discourse. This is in keeping with Authier thesis according to which in anaphoric contexts, PolParts are not used to contradict a proposition but to mark the polarity contrast between two propositions. In the case of et pourtant si/non, the contrast is between a discursive segment in an intensional modal environment and an assertion that triggers a set of alternatives. As was seen previously (Section 2.3), the connector mais (but) licenses the contrast between two conjoined elements. The same goes for the dm pourtant.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ has to be anaphorically recovered from an adequate antecedent in the same discourse. This is in keeping with Authier thesis according to which in anaphoric contexts, PolParts are not used to contradict a proposition but to mark the polarity contrast between two propositions. In the case of et pourtant si/non, the contrast is between a discursive segment in an intensional modal environment and an assertion that triggers a set of alternatives. As was seen previously (Section 2.3), the connector mais (but) licenses the contrast between two conjoined elements. The same goes for the dm pourtant.

contrast condition:Footnote [49]

et pourtant si/non (i) introduces a proposition ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$, which is contrasted with a preceding proposition

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$, which is contrasted with a preceding proposition ![]() $A$.

$A$. ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ is felicitously contrasted with

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ is felicitously contrasted with ![]() $A$ iff

$A$ iff ![]() $[[A]]^{o}$ implies or falls within the focus semantic value of

$[[A]]^{o}$ implies or falls within the focus semantic value of ![]() $[[\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}]]^{f}$. (ii) The speaker is certain that

$[[\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}]]^{f}$. (ii) The speaker is certain that ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ should be added to the cg.Footnote [50]

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ should be added to the cg.Footnote [50]

Thus, contra Anscombre (Reference Anscombre2002) (cf. Section 2.1), I assume that ‘et’ (and) in et pourtant is not the marker of an opposition between two terms in an argumentation. A cogent argument against Anscombre’s claim is that pourtant cannot be omittedFootnote [51] as illustrated in (63):

I thus argue that the function of et in these sentences is to specify the way in which the two discursive segments are linked together, so as to maintain topic continuity.Footnote [52] Additionally, since the antecedent proposition does not assert a content ![]() $p$, the use of et portant si/non is semantically motivated by the wish of the speaker to add a content

$p$, the use of et portant si/non is semantically motivated by the wish of the speaker to add a content ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ to the cg.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ to the cg.

We will now proceed to examine some relevant examples.

4.2 Analysis of relevant examples

In most cases, the antecedents of et pourtant si/non are propositions in the scope of an epistemic or modal operator (e.g. devoir, (should), pouvoir (might), sembler (seem) or a propositional attitude predicate penser (think), croire (believe), dire (say)). In an example like (64), what is relevant is the set of alternatives built from the epistemic operator verum.

Contrary to this, the examples in (65) illustrate a contrast between two polarities. In these examples, the negation is expressed lexically by the morphologically complex adjectives impossible, improbable, incroyable (unbelievable)…, in which the negative affix in– or one of its allomorphs is attached to an adjective base. In all the examples of our corpus, adjectives are epistemic adjectives.

These epistemic adjectives take propositional arguments, and consequently they do not predicate over individuals (of type (![]() $\langle s,\langle e,t\rangle$)) but propositions (of type (

$\langle s,\langle e,t\rangle$)) but propositions (of type (![]() $\langle \langle s,t\rangle ,t\rangle$)). In (65), the set of alternatives is

$\langle \langle s,t\rangle ,t\rangle$)). In (65), the set of alternatives is ![]() $\{p,\neg p\}$ and this is a case of polarity focus represented below:Footnote [57]

$\{p,\neg p\}$ and this is a case of polarity focus represented below:Footnote [57]

This provides an explanatory account of the infelicitous examples in (66):

Another type of example where the use of et pourtant si/non is accounted for by polarity focus is illustrated in (67):

I will represent the relevant part of this example as in (68):

As was seen in example (60), et pourtant si/non can be used as a reaction to a modalized answer to a polar question. Consider (69):

In this example, the answer is modalized: dans un sens (in a way, a priori, as far as I can see, etc. are all compatible both with il semble que (it seems that)Footnote [60] and with the opposition marker pourtant). The modalized answer expresses that ‘it is possible that ![]() $p$, it is possible that

$p$, it is possible that ![]() $\neg p$’. Following Krifka (Reference Krifka, Féry and Sternefeld2001), a polar question like (69) would be represented as follows:

$\neg p$’. Following Krifka (Reference Krifka, Féry and Sternefeld2001), a polar question like (69) would be represented as follows:

These biased answers license et pourtant si/non, and a non-modalized answer with et pourtant si/non would be infelicitous. This is illustrated in (71):

The discourse in (72) is ambiguous as there are three candidate antecedents for et pourtant si depending on the accessible proposition: (i) the object argument of the verb soutenir (argue, claim), which expresses the speaker’s attitude (he could not have thrown himself under the car); (ii) the complement of the modal pouvoir (could) : ’have throw himself under the car’; or (iii) the second term of the relation triggered by puisque (since) : ’he had not been on the street’:

Two sets of alternatives are possible:

The problem is to find the most appropriate of the two sets of alternatives for (72). Under the present approach, contextual inferences (Rooth Reference Rooth, Hestvik and Berman1992a, Hardt & Romero Reference Hardt and Romero2004) can be used. For instance, in (72) this inference is: ‘![]() $x$ is not in the street’

$x$ is not in the street’ ![]() $\Rightarrow$ ‘

$\Rightarrow$ ‘![]() $x$ cannot throw himself under the car’. In this case, the inference is primarily based on the polarity-focus contrast and the contrastive interpretation based on verum is derived (i.e. he may or he may not throw himself under the car).Footnote [64]

$x$ cannot throw himself under the car’. In this case, the inference is primarily based on the polarity-focus contrast and the contrastive interpretation based on verum is derived (i.e. he may or he may not throw himself under the car).Footnote [64]

4.3 Complex cases

Under the present approach, the analysis of alternatives should account for examples such as (74), in which the sequence et pourtant si/non is incompatible with the modal verb faillir (almost, nearly).Footnote [65] Note, however, that it is not possible to suggest that as the action denoted by the infinitive form of the verb tomber (fall) did not take place, et pourtant non would be redundant and et pourtant si would be contradictory. The reason is that in some cases (cf. 74b), the action may have started, and yet et pourtant si is disallowed:

Since faillir is a modal verb, in our approach, there is a set of alternatives built on the operator verum: verum: ![]() and

and ![]() that upgrade the cg. My hypothesis is that the very semantics of faillir (which presupposes that its complement is false) forces a reading in which the truth of

that upgrade the cg. My hypothesis is that the very semantics of faillir (which presupposes that its complement is false) forces a reading in which the truth of ![]() $\neg p$ is added to the cg.Footnote [66] If this is followed by et pourtant non, the truth of this assertion is emphasized, which is odd or slightly paradoxical as illustrated by (75) below:

$\neg p$ is added to the cg.Footnote [66] If this is followed by et pourtant non, the truth of this assertion is emphasized, which is odd or slightly paradoxical as illustrated by (75) below:

Note however that a continuation of the discourse with et pourtant coherent with the discursive segment containing faillir is felicitous:Footnote [67]

I turn now to the contrast between et pourtant si/non and antecedents that have the form of counterfactual conditionals (Lewis Reference Lewis1973), such as that in (77). Counterfactuals can be generically expressed as ‘if ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ had taken place, it would have been the case that

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ had taken place, it would have been the case that ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$’, which presupposes that

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$’, which presupposes that ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ did not take place in the actual world. Notice the contrast between (77a,b):

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ did not take place in the actual world. Notice the contrast between (77a,b):

In (77a) the constraints are in the epistemic state of the speaker, and the speaker contradicts himself. In (77b) the contrast condition is respected (i.e. [[[I will come to the party]]] ∈ F([My brother won’t 〈come to the party〉])).Footnote [68]

How is it possible to account for the choice of the relevant antecedent in (78)?

The choice of the relevant antecedent in counterfactuals is driven by the focalized constituent and the packaging of the information in the conditional sentence. In (79a) the apodosis is focalized whereas in (79b) it is the protasis that is focalized:

In the analysis of counterfactuals, the consequent must be assessed in connection with the possible worlds (or situations) in which Pierre called (79a) and in which Marie called (79b). It is in these situations that it can be said that the content of the counterfactual is true. In example (79a) the contrast is in accordance with what is expected as it is based on polarity focus: ![]() .

.

Conversely, in (79b) if the consequent was the alternative to et pourtant non, there would be a contradiction (Marie calls me up ![]() I am glad).Footnote [69] The same problem arises in dialogues as that exemplified in (80):

I am glad).Footnote [69] The same problem arises in dialogues as that exemplified in (80):

Following the approach taken here, the antecedent of et pourtant non is the embedded proposition that is under the scope of the propositional attitude predicate, here the whole counterfactual proposition ![]() $p$, and this leads to the definition of the set of alternatives:

$p$, and this leads to the definition of the set of alternatives:

As was seen before in examples (29) and (30), repeated here in (82a,b) for the sake of simplicity, PolParts can appear in embedded clauses:Footnote [71]

As argued in Authier (Reference Authier2013: p. 371), French polarity particles oui/non mark the left edge of a TP elision site. Following Authier (Reference Authier2013), in the example in (83) the PP to his son represents a clitic left dislocation and thus must be linked to a silent copy lower than Top P in the structure.

From this point of view, similar sentences with et pourtant si/non are given below:

My feeling is that the present approach, which targets the properties of the sequence et pourtant si/non, could be extended to cover these cases and provide the adequate tools for an analysis of this distribution of PolParts.Footnote [72]

5 Conclusions

The results of the present study can be summarized as follows.

In the line of thought of Jayez (Reference Jayez1988) and Martin (Reference Martin1987), I have shown that although the dm pourtant is not itself a modal, it appears to express a contrast between two modal expressions whose modal forces are ‘polar opposites’ given that they operate on different modal bases that are not contradictory.

The evidence is mixed as to the anaphoric status of et pourtant si/non: it displays some properties not only of TP-Ellipsis but also of propositional anaphora, and consequently the antecedent of et pourtant si/non can be recovered by means of either type of anaphoric process. The occurrence of the sequence et pourtant si/non is constrained by the presence of a modalized environment. This suggests an interesting parallelism with the results found in Authier (Reference Authier2011) regarding modal ellipsis in French.

The free variation between oui and si in et pourtant si shows that the feature [reverse] is not a relevant factor. This result contradicts the prediction made by the classification proposed by Roelofsen & Farkas (Reference Roelofsen and Farkas2015), but it is in accordance with the Authier analysis of TP-ellipsis, where contrast is the relevant feature. I consequently argue that in some contexts, oui is a strong PPI. However, this is not equivalent to saying that there are two sets of PolParts, one for answers to polar questions and the other for assertions. This rather supports the view that different types of constraints apply to the same item, depending on its use.

The sequences et pourtant si/non, oui and si/non are instances of vf that emphatically mark the polarity of a proposition by opposing it to another proposition, which is both salient and accessible in the discourse. This is how PolParts upgrade the cg.

In Hardt & Romero (Reference Hardt and Romero2004), it is suggested that the construction of sets of alternatives based on polarity focus is preferred to that based on verum, unless there is an epistemic bias. Interestingly, our results provide support for the second option: that in which the antecedent is under the scope of a modal operator. Furthermore, the polarity contrast allowed us to account for some examples in which this factor is more salient, and this consequently led us to offer a new contribution to the debate about the nature and status of vf.

I provided support for an analysis of vf in the framework of alternative semantics. This analysis showed too that the scope of an epistemic operator (Romero & Han Reference Romero and Han2004) and the conditions of use were relevant factors in anaphoric contexts. In these contexts, the adequate antecedent can be recovered by the construction of alternatives based on focus, which is not possible in an analysis based solely on lexical insertion and upgrading of the qud by conditions governing the felicitous use of a form in discourse.