1 Introduction

As observed by a number of scholars, object negative quantifiers seem to misbehave when submitted to some of Klima’s (Reference Klima, Fodor and Katz1964) diagnostic tests for sentential negation, while this is not the case for subject and adjunct negative quantifiers. Ross (Reference Ross, Gross, Halle and Schützenberger1973), McCawley (Reference McCawley1988/1998), Horn (Reference Horn1989), Moscati (Reference Moscati2006) and, more recently, De Clercq (Reference De Clercq, An and Kim2010a, Reference De Clercqb) and De Clercq, Haegeman & Lohndal (Reference De Clercq, Haegeman and Lohndal2012), for instance, point out that postverbal negative quantifier objects such as nobody in (1) can take a negative tag question.

This is unexpected, as negative quantifiers introduce an instance of logical negation that makes the proposition negative (Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1973). Therefore, a sentence such as (1) should take a positive tag question.

Before proceeding further, let us clarify that English tag questions can be of two kinds depending on whether the polarity of the antecedent clause is reversed in the question tag or not (Klima Reference Klima, Fodor and Katz1964, Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985, McCawley Reference McCawley1988/1998, among others). While in reverse polarity question tags the antecedent clause and the tag have different polarity, thus resulting in the two combinations in (2), in reduplicative question tags (Brasoveanu et al. Reference Brasoveanu, De Clercq, Farkas and Roelofsen2014) – also known as constant question tags in Tottie & Hoffmann (Reference Tottie and Hoffmann2006) – the polarity of the antecedent clause and that of the tag is the same.

This should give rise to two possible combinations too, namely the ones in (3). However, only the combination in (3a) is regularly attested in English.

By contrast, question tags of the kind in (3b) are considered to be rare or occasional by Tottie & Hoffmann (Reference Tottie and Hoffmann2006), who report having found just two genuine examples of this kind of tag question in a corpus study that included the spoken component of the British National Corpus (10.36 million words) and the Longman Spoken American Corpus (5 million words).Footnote [2] Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985) and McCawley (Reference McCawley1988/1998) also mention that negative-negative question tags are not attested in actual use. Swan (Reference Swan2005: 481), for whom question tags of the kind in (3b) are also rare, claims them to sound aggressive.

In this paper, I argue that (1) must be distinguished from a genuine reduplicative question tag of the negative-negative kind in (3b). In other words, example (1) is unexpected under the assumption that the question tag is of the reverse polarity kind, (2), and has the function of seeking confirmation of the statement expressed in the antecedent main clause, which is a discourse function of reverse tag questions (Cattell Reference Cattell1973, McCawley Reference McCawley1988/1998, among others).

Returning to the example in (1), in an experimental study carried out by Brasoveanu et al. (Reference Brasoveanu, De Clercq, Farkas and Roelofsen2014) it was found not only that antecedent clauses with object negative quantifiers could take negative tag questions of the reverse polarity kind, but also that antecedent clauses with subject and adverb negative quantifiers did not, as they consistently triggered the use of positive polarity reverse tag questions in the same way negative control sentences did. This is shown in (4) and (5).Footnote [3]

McCawley ([Reference McCawley1988/]Reference McCawley1998: 607) discusses a second test where object negative quantifiers do not behave as expected from a linguistic expression that contributes sentential negation to the clause. He reports both either and too to be possible with object negative quantifiers, (6a, a

![]() $^{\prime }$

), while only either is grammatical with subject and adjunct negative quantifiers, (6b, b

$^{\prime }$

), while only either is grammatical with subject and adjunct negative quantifiers, (6b, b

![]() $^{\prime }$

) and (6c, c

$^{\prime }$

) and (6c, c

![]() $^{\prime }$

).

$^{\prime }$

).

In a similar vein, Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff1972: 364) observes that both so and neither are possible with object negative quantifiers, (7a, a

![]() $^{\prime }$

), while this is not the case with subject and adjunct negative quantifiers, (7b, b

$^{\prime }$

), while this is not the case with subject and adjunct negative quantifiers, (7b, b

![]() $^{\prime }$

) and (7c, c

$^{\prime }$

) and (7c, c

![]() $^{\prime }$

).

$^{\prime }$

).

Finally, when submitted to Klima’s (Reference Klima, Fodor and Katz1964) not even + X test, which is a possible continuation only for negative sentences, (8), negative quantifier objects, negative quantifier adjuncts and negative quantifier subjects behave alike, (9).

However, as pointed out by an anonymous referee, this test does not have a non-negative counterpart that parallels the negative question tag, too-licensing, and so-coordination in the other three tests, so such a test is not very informative as to what the difference might be in the syntax of object negative quantifiers on the one hand, and subject and adjunct negative quantifiers on the other.

It is the case, though, that, as shown in (10), when negation is of the kind that has traditionally been described as constituent negation (Klima Reference Klima, Fodor and Katz1964) (i.e. as non-sentential negation), the not even + X test fails, and the question tag is negative, too is licensed and coordination is with so.

Therefore, in this paper I take non-sentential negation to be the one that fails to reverse the truth-conditions of the proposition expressed by the clause. Given that English speakers consider (1) truth-conditionally equivalent to the main clause in (8b), I conclude that negative quantifiers introduce an instance of sentential negation regardless of the position they occupy. It is thus an aim of this paper to explain why sentential negation is not diagnosed as such by certain tests when encoded in object negative quantifiers.

Four potential explanations come to mind to account for the facts presented above: if a negative sentence such as (1) can take a negative reverse polarity tag question, license too and allow so-coordination, then (i) the sentence is not negative; (ii) the aforementioned Klima’s (Reference Klima, Fodor and Katz1964) tests may not be a good diagnostic for sentential negation; (iii) the sentence has not been typed as negative by the time the tests apply; and (iv) the syntactic structure that is relevant to the tests does not contain any negation.

The first of the above potential explanations is ruled out by the results of Klima’s tests when applied to negative quantifiers in syntactic positions other than that of object in (4)–(7), and by the judgments in (9). The second of the possible explanations, namely that Klima’s (Reference Klima, Fodor and Katz1964) tests may not be good diagnostics for sentential negation, overgeneralizes.Footnote [4] Leaving the not even + X test aside, the other three tests presented above are only problematic for object negative quantifiers, but provide a clear-cut result for adjunct and subject negative quantifiers. Thus, Klima’s tests cannot be rejected as diagnostics for sentential negation across the board.

The third potential explanation, namely that the sentence has not been typed as negative by the time the tests apply is not new. In the particular case of the tag question test, Moscati (Reference Moscati2006) and De Clercq (Reference De Clercq, An and Kim2010a, Reference De Clercqb) explain the occurrence of negative tag questions with clauses containing object negative quantifiers as a consequence of the antecedent clause being typed as affirmative by default. In other words, when the tag question is merged to the antecedent clause, this has not been typed as negative yet. As will be seen, these two analyses face the same crucial problem: if the clause is typed as affirmative by default, it amounts to saying that the proposition is not negative at all. However, this goes against the speakers’ interpretation of a sentence such as (1) as

![]() $\neg p$

(and thus as truth-conditionally equivalent to the main clause in (8b)).

$\neg p$

(and thus as truth-conditionally equivalent to the main clause in (8b)).

Moscati (Reference Moscati2006) argues that negative tag questions co-occur with sentences with object negative quantifiers when Force, a left-peripheral functional projection above TP (and hence also above vP) dedicated to illocutionary force, has been valued as positive by default due to the restrictions imposed by the Phase Impenetrability Condition, formalized in (11).Footnote [5]

Moscati assumes that Force bears an uninterpretable and unvalued negative feature that probes for a matching interpretable feature. Negative quantifiers bear an interpretable and valued negative feature and, hence, can potentially serve as Goals for the Probe in Force. In Moscati’s account, however, the Phrase Impenetrability Condition prevents postverbal negative quantifiers (i.e. negative quantifiers inside VP) from valuing the uninterpretable negative feature in Force, as only the edge of vP is accessible to Force. Hence, the feature in Force is valued as positive by default and the negation is narrow in scope (i.e. it is constituent or non-sentential negation).

For the negative quantifier to convey sentential negation, an unvalued interpretable feature at the edge of vP should agree with the interpretable and valued negative feature of the postverbal negative quantifier. When this is the case, the Probe in Force can access it for valuation of its uninterpretable and unvalued feature as negative. This accounts for the diagnosis of the sentence as negative in (6a), (7a) and (9a) above, but predicts that the question tag with object negative quantifiers will always be positive, contrary to what has been seen in (1), and that clauses with object negative quantifiers will always have to license either and be continued with neither, contrary to what has been shown to be the case in (6a, a

![]() $^{\prime }$

) and (7a, a

$^{\prime }$

) and (7a, a

![]() $^{\prime }$

). In short, Moscati’s (Reference Moscati2006) analysis only works for examples such as (1), (6a

$^{\prime }$

). In short, Moscati’s (Reference Moscati2006) analysis only works for examples such as (1), (6a

![]() $^{\prime }$

) and (7a

$^{\prime }$

) and (7a

![]() $^{\prime }$

) insofar these are considered to be cases of constituent negation, but if they are, their meaning equivalence with a sentence such as John didn’t read anything (i.e.

$^{\prime }$

) insofar these are considered to be cases of constituent negation, but if they are, their meaning equivalence with a sentence such as John didn’t read anything (i.e.

![]() $\neg p$

) cannot be accounted for.

$\neg p$

) cannot be accounted for.

In a similar vein, De Clercq (Reference De Clercq, An and Kim2010a, Reference De Clercqb) assumes that clauses contain a Polarity head in the CP field that needs to be valued for polarity in the course of the derivation. For De Clercq, postverbal negative quantifier objects, which are inside vP, cannot value the polarity feature of the Polarity head in the CP, because they do not participate in the CP phase. Hence, the unvalued feature of the Polarity head is valued as affirmative by default. As discussed earlier for Moscati’s (Reference Moscati2006) account, De Clercq’s explanation cannot handle the fact that speakers interpret (1) as equivalent in meaning to John didn’t read anything (i.e. as

![]() $\neg p$

). In addition, recall that a negative tag question can be appended to (1) by some speakers but not by all. Hence, it is clear that object negative quantifiers would not be generally unable to type the clause as negative.

$\neg p$

). In addition, recall that a negative tag question can be appended to (1) by some speakers but not by all. Hence, it is clear that object negative quantifiers would not be generally unable to type the clause as negative.

Finally, the fourth possible explanation outlined above – namely that the syntactic structure that is relevant to the tests does not contain any negation – is the one I explore in this paper. In particular, I claim that the grammaticality that some speakers attribute to (1), (6a

![]() $^{\prime }$

) and (7a

$^{\prime }$

) and (7a

![]() $^{\prime }$

) follows from two facts: (i) that the syntactic structure that is relevant for the various operations (i.e. polarity reversal in tag questions, polarity licensing of either/too, and neither-/so-coordination) contains no negative feature in the grammar of speakers who accept (1), (6a

$^{\prime }$

) follows from two facts: (i) that the syntactic structure that is relevant for the various operations (i.e. polarity reversal in tag questions, polarity licensing of either/too, and neither-/so-coordination) contains no negative feature in the grammar of speakers who accept (1), (6a

![]() $^{\prime }$

) and (7a

$^{\prime }$

) and (7a

![]() $^{\prime }$

), and (ii) that the syntactic material that is relevant for polarity reversal, licensing of either/too, and neither-/so-coordination is TP.

$^{\prime }$

), and (ii) that the syntactic material that is relevant for polarity reversal, licensing of either/too, and neither-/so-coordination is TP.

In this paper, I also try to extend the analysis of the facts in (1), (6) and (7) to accommodate Postal’s (Reference Postal2004: 164) observation that both the ‘expression of agreement’ clauses Yes, I guess so and No, I guess not are fine with object negative quantifiers, while – as has already been shown to be the case in the question tag test, the either/so test, and the neither/so test – only an ‘expression of agreement’ clause with not is possible with subject and adjunct negative quantifiers, (12)–(14).

To articulate my proposal I make a number of theoretical assumptions, which are outlined in Section 2. First, I assume that English negative quantifiers are non-atomic complex syntactic objects that contain a negative component and an existential quantifier that only become a single lexical unit at the PF interface (Klima Reference Klima, Fodor and Katz1964, Jacobs Reference Jacobs1980, Ladusaw Reference Ladusaw, Barker and Dowty1992, Rullmann Reference Rullmann1995, Larson, den Dikken & Ludlow Reference Larson, den Dikken and Ludlow1997, Sauerland Reference Sauerland and Sauerland2000, Penka & Zeijlstra Reference Penka and Zeijlstra2010, Penka Reference Penka2011, Iatridou & Sichel Reference Iatridou and Sichel2011, Temmerman Reference Temmerman2012, among others). Second, I follow Temmerman (Reference Temmerman2012) in analyzing English negative quantifiers as multidominant phrase markers. Third, in line with Lasnik (Reference Lasnik1972), van Craenenbroeck (Reference van Craenenbroeck2010) and Temmerman (Reference Temmerman2012), among others, I assume that two positions are available for negation in English: PolP2 is above vP (i.e. in the TP-domain), and PolP1 is above TP (i.e. outside the TP-domain), (15).Footnote [6]

Given that negation is considered sentential if it takes scope above the main predicate of the clause (see Acquaviva Reference Acquaviva1997 and Penka Reference Penka2007), both positions for negation in (15) are taken to be suitable for the expression of sentential negation. In this paper, nonetheless, I show that encoding negation in one position or another has relevant consequences for the syntax of tag questions, neither-/so-coordination, either-/too-licensing, and expression of agreement clauses.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, I outline the assumptions made on (i) the internal structure of negative quantifiers in English, (ii) their multidominant nature as a result of Parallel Merge (Citko Reference Citko2005, Reference Citko and Boeckx2011), and (iii) the structure of tag questions, and of coordinated clauses. In Section 3, an analysis is put forward for the unexpected behavior of tag questions with sentences containing an object negative quantifier, as well as for the behavior of clauses with object negative quantifiers with respect to neither-/so-coordination and either-/too-licensing that relies on the theoretical assumptions presented in Section 2. The case of ‘expression of agreement’ clauses is also briefly discussed. Section 4 concludes.

2 Theoretical considerations

In this section, I address four issues that are central to the account that is put forward in Section 3. In Section 2.1, negative quantifiers are shown to be decomposable into a negative component and an existential quantifier. In Section 2.2, a third type of Merge (i.e. Parallel Merge) is presented. Parallel Merge combines properties of the other two types, namely Internal and External Merge, and results in multidominance (i.e. a daughter node having two mother nodes), which has been claimed to be a property of English negative quantifiers (Temmerman Reference Temmerman2012).Footnote [7] In Section 2.3, Sailor’s (Reference Sailor2009, Reference Sailor2012) analysis of tag questions as full CPs with VP-ellipsis is outlined, and in Section 2.4, I show that only material inside TP is relevant for the syntax of question tags. In Section 2.5, I build on Krifka’s (Reference Krifka2016) claim that reverse polarity question tags are related to their antecedent clause by means of disjunction. Finally, in Section 2.6, I present some assumptions on the nature of coordination based on Munn (Reference Munn1993) and Progovac (Reference Progovac1998a, Reference Progovacb), which are relevant to the licensing of too and either, and to so- and neither-coordination.

2.1 On the internal structure of negative quantifiers

Negative quantifiers (e.g. English no, nobody or nothing, or German kein ‘no’) have been analyzed in the literature as decomposable into a negative part and an existential part (Klima Reference Klima, Fodor and Katz1964, Jacobs Reference Jacobs1980, Ladusaw Reference Ladusaw, Barker and Dowty1992, Rullmann Reference Rullmann1995, Larson et al. Reference Larson, den Dikken and Ludlow1997, Sauerland Reference Sauerland and Sauerland2000, Penka & Zeijlstra Reference Penka and Zeijlstra2010, Penka Reference Penka2011, Iatridou & Sichel Reference Iatridou and Sichel2011, Temmerman Reference Temmerman2012, Tubau Reference Tubau2016, among others).Footnote [8] These two parts enter the derivation separately and may become a complex object in the syntax, and a single lexical item at PF (Klima Reference Klima, Fodor and Katz1964, Jacobs Reference Jacobs1980, Rullmann Reference Rullmann1995, Iatridou & Sichel Reference Iatridou and Sichel2011, Zeijlstra Reference Zeijlstra2011, Temmerman Reference Temmerman2012).

In support of a decompositional view of negative quantifiers, Jacobs (Reference Jacobs1980, Reference Jacobs1982, Reference Jacobs, von Stechow and Wunderlich1991) discusses the existence of Split Scope readings (already observed by Bech Reference Bech1955/57), which may emerge for the negative quantifier kein when it interacts with other scope-taking operators. Split Scope readings, which have also been reported to be available in Dutch (Rullmann Reference Rullmann1995), and English (Potts Reference Potts2000), are illustrated in (16).

As can be seen, the negative quantifier can take wide scope with respect to need, (16b), but not narrow scope, (16c). Split Scope, with negation scoping over need and the existential part under it, (16a), is also an available reading.Footnote [9]

Split Scope readings of negative quantifiers, however, have also been accommodated in semantic accounts of quantification that did not assume negative quantifiers to be decomposable. Geurts (Reference Geurts1996), for example, assumes negative quantifiers to form a semantic unit, and Split Scope readings to be the result of quantification over kinds à la Carlson (Reference Carlson1977), while De Swart (Reference De Swart, von Heusinger and Egli2000) argues Split Scope readings to follow from quantification over properties.Footnote [10] More recently, Abels & Martí (Reference Abels and Martí2010) put forward a unified account of Scope Splitting for negative quantifiers in intensional contexts, comparative quantifiers, and numerals, where Split Scope readings follow from quantification over choice functions. For reasons of space, I cannot discuss each of these accounts in detail here and thus direct the reader to the original sources for further reading, as well as to Penka (Reference Penka2007, Reference Penka2011) for some criticism of the first two.

Given that the existence of Split Scope readings with negative quantifiers cannot be seen as a conclusive argument for a decompositional approach to negative quantifiers, let us discuss some further evidence coming from the behavior of negative indefinites under ellipsis. As shown in Temmerman (Reference Temmerman2012: 50), not … any can antecede the ellipsis of no in clausal ellipsis, but not in verbal ellipsis.

For the elliptical answer in (17), four different underlying structures are possible depending on a number of different assumptions made on the ellipsis literature; they are presented in (18). The strike-through indicates that the syntactic material has been elided and is not phonologically realized.

Note that the structure in (18a) is ungrammatical due to lack of NPI-licensing; in (18b) a universal quantifier intervenes between negation and the NPI, with the structure thus violating the Immediate Scope Constraint; but (18c, d) are convergent and, crucially, confirm that not … any can be an antecedent of no in elliptical clauses.

Concerning verbal ellipsis, as shown in (19) and (20), not … any cannot antecede the ellipsis of no, (19d) and (20d).

Furthermore, an object negative indefinite cannot scope out of a VP-ellipsis site, (21) and (22).

In (21), a reading where negation scopes higher than the modal is not attested. In (22a), negation can have high scope (‘Mary doesn’t look good with any clothes’), or not (‘Mary looks good without any clothes’), but in (22b), only a reading where negation is non-sentential is available.

Temmerman (Reference Temmerman2012: 91) accounts for the ellipsis facts presented above as indicating that negative quantifiers result from an operation that allows the two components of a negative quantifier to become a single lexical unit. Such an operation is known as Fusion Under Adjacency (FUA), and was originally put forward by Johnson (Reference Johnson2010, Reference Johnson2012). FUA applies when two terminals are adjacent at Spell-Out (i.e. linearized next to each other, with no other terminal intervening between the two). Being a PF-phenomenon, ellipsis prevents negative quantifiers from being formed at PF.

According to Temmerman (Reference Temmerman2012: 85–86), a negative quantifier such as nobody, for example, would be built in two steps.

First, a D a (ny) would merge with the N body, as in (23a), and then Neg not would merge with the resulting DP, as in (23b).

How the structure in (23b) merges with the verb, and how negation and the existential DP end up being linearized as adjacent so they can undergo FUA at PF is explained in Section 2.2 after the concepts of Parallel Merge and multidominance have been presented.

2.2 Parallel Merge and multidominance

According to Chomsky (Reference Chomsky and Kenstowicz2001, Reference Chomsky2005), Merge can be of two types, External and Internal. While the former allows two independent lexical items (

![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x03B1}$

and

$\unicode[STIX]{x03B1}$

and

![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x03B2}$

) to be joined into one syntactic object, as in (24a), the latter allows a copy of

$\unicode[STIX]{x03B2}$

) to be joined into one syntactic object, as in (24a), the latter allows a copy of

![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x03B1}$

or

$\unicode[STIX]{x03B1}$

or

![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x03B2}$

to be remerged with the syntactic object resulting of External Merge of

$\unicode[STIX]{x03B2}$

to be remerged with the syntactic object resulting of External Merge of

![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x03B1}$

and

$\unicode[STIX]{x03B1}$

and

![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x03B2}$

, as in (24b).

$\unicode[STIX]{x03B2}$

, as in (24b).

Parallel Merge (Citko Reference Citko2005), seen in (24c) above, is a combination of the other two types, as it allows

![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x03B2}$

, which is part of the complex syntactic object

$\unicode[STIX]{x03B2}$

, which is part of the complex syntactic object

![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x03B1}$

(as in Internal Merge) to merge with an independent syntactic object

$\unicode[STIX]{x03B1}$

(as in Internal Merge) to merge with an independent syntactic object

![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x03B3}$

(as in External Merge). The result of Parallel Merge is a multidominant structure, (24c), where

$\unicode[STIX]{x03B3}$

(as in External Merge). The result of Parallel Merge is a multidominant structure, (24c), where

![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x03B2}$

has two mothers,

$\unicode[STIX]{x03B2}$

has two mothers,

![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x03B1}$

and

$\unicode[STIX]{x03B1}$

and

![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x03B3}$

.

$\unicode[STIX]{x03B3}$

.

In line with Johnson (Reference Johnson2010), Temmerman (Reference Temmerman2012: 87) assumes that English object negative quantifiers undergo Parallel Merge with V. That is, given a structure such as (23b) above, V would not select NegP, the complex negative object. Rather, the verb would select an object DP, which corresponds just to the existential part of the negative quantifier. This is illustrated in (25).

The main implication of such an analysis is that Neg, the negative component of the negative quantifier, is not part of the VP, the complement of the phase head v, which is Transferred upon completion of the vP phase.Footnote [12] If NegP is not Transferred when the vP phase is completed, it will then be able to participate in a higher phase and have scope over v, with negation taking sentential scope. Recall that according to Penka (Reference Penka2007: 11), who in turn follows Acquaviva (Reference Acquaviva1997), negation is assumed to be sentential if it scopes over the event expressed by the verb.

According to Temmerman (Reference Temmerman2012: 90), once the VP has been Transferred, a Polarity head merges with vP, and NegP can merge in its Specifier. However, as it is a complex Specifier, it is assumed, following Uriagereka (Reference Uriagereka, Epstein and Hornstein1999), that it is sent to the interfaces before merging with Polarity Phrase (PolP).Footnote [13]

In short, the DP in (25) above is linearized after the VP is Transferred, whereas NegP is linearized before it merges in the Specifier of PolP. Temmerman (Reference Temmerman2012: 90) gives the linearizations in (26) for VP and NegP, and the definition of the Adjacency condition on Fusion in (27).

As can be seen in (26), nothing intervenes between D and Neg, which allows these two terminals to undergo FUA (Temmerman Reference Temmerman2012: 91) and become a negative quantifier that contributes sentential negation to the clause in English.

Like Temmerman (Reference Temmerman2012), who aligns with a number of other scholars (Cormack & Smith Reference Cormack, Smith, Barbiers, Beukema and van der Wurff2002, Butler Reference Butler2003, Holmberg Reference Holmberg, Pica and Rooryck2003, among others) in assuming that two positions dedicated to polarity exist in English – one above vP and one above TP – I also take sentential negation in English to be ultimately related to a TP-internal and to a TP-external position (see (15) above). That is, the uninterpretable polarity feature (i.e. [upol: ]) that needs to be valued for clause-typing (see Tubau Reference Tubau2008; De Clercq Reference De Clercq, An and Kim2010a, Reference De Clercqb; see also Haegeman Reference Haegeman1995, Kato Reference Kato, Horn and Kato2000, Biberauer & Roberts Reference Biberauer, Roberts, Larrivée and Ingham2011, and De Clercq, Haegeman & Lohndal Reference De Clercq, Haegeman, Lohndal and Lohndal2017) can either be in the TP-domain (if encoded in PolP2, above vP), or outside the TP-domain (if encoded in PolP1, above TP). Assuming the feature [upol: ] in Pol1 and Pol2 to be a Probe, and the negative feature of Neg (i.e. [pol:neg]) to be a Goal, clause-typing of a sentence as negative is the result of an Agree relation between Pol1/Pol2 and Neg.Footnote [14]

In Section 3, I return to this issue, showing that two possible derivations for a clause with an object negative quantifier exist, which follow from whether PolP1 and PolP2 are the relevant positions for negation. According to Temmerman (Reference Temmerman2012) – who in turn follows Iatridou & Sichel (Reference Iatridou and Sichel2011) – the scopal relation of negation with other scope-taking operators determines the choice of which of the two PolPs is active. Crucially, though, in the absence of other scope-taking operators, the choice of PolP1 and PolP2 is free (Temmerman Reference Temmerman2012: 80). What I show in this paper is that when negation is expressed by means of an object negative quantifier, the activation of PolP1 or PolP2 has visible consequences for (i) the choice of a positive or a negative reverse polarity tag question; (ii) the choice of neither- or so-coordination; (iii) the licensing of either and too; and (iv) the choice of ‘agreement of expression’ clauses.

2.3 Tag questions and VP-ellipsis

In this section I review the work by Sailor (Reference Sailor2009, Reference Sailor2012), who gives evidence in favor of analyzing English tag questions as yes/no-questions (i.e. full CPs) that have undergone VP-ellipsis (VPE, henceforth). The first part of this assumption is in line with much older work by Huddleston (Reference Huddleston1970), Bublitz (Reference Bublitz1979), McCawley (Reference McCawley1988/1998) and Culicover (Reference Culicover1992), among others, whereas the second part – namely that tag questions are instances of VPE (Merchant Reference Merchant2001) – is based on the observation that they behave like other clauses with VPE with respect to the distribution of auxiliaries and their stranding possibilities.

As seen in (28a, b) below, Sailor (Reference Sailor2009: 28) shows that the T head in the antecedent clause cannot be elided in the clause with VPE. The examples in (28c, d) show that the same is true for tag questions.

In addition, if negation is present, as in (29), it has the same distribution in clauses with VPE, (29a), and in tag questions, (29b).

With respect to perfective have, it is shown in (30) that, again, the conditions for stranding are the same in VPE and tag questions.Footnote [15]

Non-finite progressive be, which, according to Sailor (Reference Sailor2009: 30), is known to optionally elide in VPE clauses, as in (31a), displays the same behavior in tag questions, as in (31b).

This also extends to VPE clauses and tag questions with multiple stranded auxiliaries, as shown in (32).

Conversely, progressive be must be elided both in VPE clauses, as illustrated in (33a, b), and in tag questions, as illustrated in (33c, d).

In short, it can be concluded that there is evidence in support of the claim that tag questions are full CPs that are subject to VPE. In this paper, however, I depart from Sailor (Reference Sailor2012), as well as from McCawley (Reference McCawley1988/1998), in that I do not assume tag questions to be adjoined to the antecedent clause (also a CP). Rather, inspired by Krifka (Reference Krifka2016), I propose, that the TP of the question tag and the TP of the antecedent clause are coordinated by means of a (silent) disjunctive conjunction or. I expand on this issue and give the assumed clause structure in Section 2.4.

As discussed in Sailor (Reference Sailor2009), it seems that the derivation of tag questions is not a process of literally copying material from the antecedent clause. As is shown by the examples in (34), from McCawley (Reference McCawley1988: 482, quoted in Sailor Reference Sailor2009: 18–22), tag questions might not be identical to their antecedent.

In particular, (i) tag questions can take coordinated clauses as their antecedent, (34a); (ii) host clauses with modal verbs may occur with tag questions that do not contain the same modal as their antecedent, (34b); (iii) the subject in a tag question with a host clause containing a collective noun triggering singular verb agreement might be plural, (34c); (iv) there can be the subject of a tag question, while it is not the subject of the host clause, (34d); (v) it can be the subject of a tag question, while it is not the (focused) subject of the host clause, (34e).

The data in (34) are taken to indicate that tag questions might be ‘sensitive to other levels of representation beyond the surface antecedent they are construed with’ (Sailor Reference Sailor2009: 35). However, as far as polarity is concerned, I claim that reverse polarity tag questions (i.e. those that reverse the polarity of the antecedent clause) are positive if a negative feature is merged inside TP, and negative if it is not. In the next section, I provide some evidence to support the claim that only material in TP (and not outside it) is relevant for the derivation of tag questions.

2.4 Tag questions and sentence adverbs

To support the (otherwise stipulated) claim that reverse polarity tag questions only take into account material that is inside TP, in this section I explore the compatibility of sentence adverbs such as certainly and probably with tag questions. Shu (Reference Shu2011) has recently analyzed sentence adverbs as C elements in spite of the fact that they can take several positions in the clause (Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1972), hence giving the false impression that they are genuine TP-elements. Hence, if it is true that tag questions are blind to material outside TP, tag questions should be blind to sentence adverbs.

As shown in (35) and (36) (which are Sailor’s (Reference Sailor2009) examples in (29) and (33) above to which the sentential adverbs certainly and probably have been added, respectively) sentential adverbs are compatible with VPE clauses.

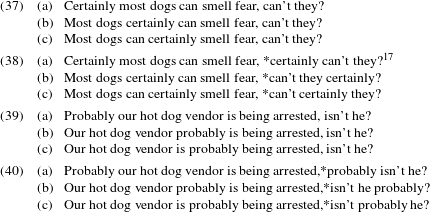

However, as shown in (37)–(40), sentence adverbs are irrelevant for tag questions.

2.5 Clauses with question tags as multidominant disjunction structures

In Krifka (Reference Krifka2016), reverse polarity question tags are analyzed as the disjunction of two speech acts: an assertion expressed by the antecedent clause, and a yes/no-question. Building on this idea, I propose that the syntax of question tags is the one in (41).

In (41), multidominance allows the TP in the antecedent clause and the TP in the tag question to be selected by C, as is expected if the antecedent clause and the tag question are two full CPs. Note, as well, that multidominance explains why two phrase markers with different semantics (an assertion in the case of the antecedent clause, and a yes/no-question in the case of the tag question) can be coordinated: if the coordinates are the TPs of the antecedent clause and the tag question rather than full CPs, identity is maintained. In short, the structure in (41) is compatible with Sailor’s (Reference Sailor2009, Reference Sailor2012) claim that question tags are full CPs, and also with the observation made in Section 2.4 that only material in the TP of the antecedent clause is relevant for the tag question.

I attribute the mechanism of polarity reversal to the effect of the disjunctive conjunction or, which is not phonologically realized in question tags. While it was assumed in Section 2.2 that clause-typing obtains with the valuation of a polarity feature either in Pol2 (above vP) or in Pol1 (above TP), I further assume that valuation of the uninterpretable feature [upol: ] takes place when the tag question has already been coordinated with the TP of the antecedent clause. Hence, the disjunctive conjunction or causes the question tag to differ in polarity from the antecedent clause, but it does so by examining the features that are part of the TP of the antecedent clause. If a negative feature is part of the TP, then the tag question is positive. If a negative feature is not part of the TP, then the tag question is negative. In Section 3, I suggest that it is possible for object negative quantifiers to type the antecedent clause as negative but with a negative feature not being part of the antecedent clause TP. This results in a negative sentence being tagged with a negative tag question, i.e. the puzzling example in (1). Likewise, I also explain why this is not a possibility for subject and adjunct negative quantifiers, which always occur with positive tag questions.

2.6 On coordination

Following Munn (Reference Munn1993) and Progovac (Reference Progovac1998a, Reference Progovacb), the coordinator and is assumed to be a head (henceforth &) that takes the first conjunct as a Specifier and the second as its complement. Symmetric coordination with & involves conjunction of CPs according to Bjorkman (Reference Bjorkman, Fainlaib, LaCara and Park2010), but this claim is to accommodate the fact that the complementizer that can be overt before each of the conjuncts. However, note that in a multidominant approach to coordination, this is possible even if the conjuncts are TPs rather than CPs. It is plausible, therefore, to assume the structure in (42) for coordinated clauses.

The structure is consistent with what has been assumed for tag questions in (41).

3 Misbehaving object negative quantifiers: Towards solving the puzzle

3.1 Object negative quantifiers and tag questions

As discussed in Section 1, it has been reported in the literature that, at least for some speakers, a clause containing an object negative quantifier can take a negative reverse polarity tag question. This is unexpected, as reverse polarity tag questions precisely contrast in polarity with the antecedent clause. That is, if the clause is positive, the question tag is negative, whereas if the antecedent clause is negative, the question tag is positive.

In this section I try to provide an answer to the two main questions raised by the data in (1), (4), and (5) above: (i) How is it possible that a negative tag question can occur with an antecedent clause that is negative by virtue of containing an object negative quantifier? (ii) Why is this uniformly not possible with subject or adjunct negative quantifiers? In order to devise the present analysis, four assumptions have been made. First, negative quantifiers have been taken to be complex syntactic objects, where the negative part is independent from the existential part in spite of the fact that they can end up forming a single lexical unit (i.e. a negative quantifier of the no-series).

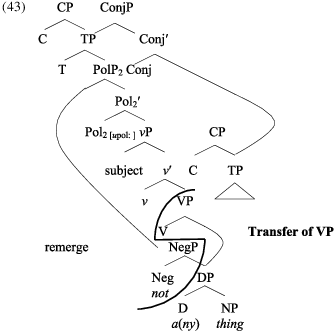

Second, object negative quantifiers are multidominant phrase markers where only the existential DP (but crucially not Neg) is c-selected by the verb. This results in VP only dominating the existential DP but not Neg. Thus, when VP, which is the complement of the phase head v, is sent to the interfaces once the vP phase is completed, only the existential DP, but not Neg, is Transferred. The Transfer domain is indicated in the trees in (43) and (44) below with a thick black line. Multidominance, hence, grants Neg the possibility to participate in a higher phase after VP has been Transferred.

Third, I have identified two positions that are available to negation in English. PolP2, which is above vP, is TP-internal, and PolP1, which is above TP, is TP-external.

Finally, tag questions have been assumed to be full CPs with VPE, and I have claimed that only material inside TP is visible to tag questions. This observation is compatible with the proposal that antecedent clauses and tag questions are syntactically linked by means of a silent disjunctive conjunction that coordinates TPs. Multidominance allows both the antecedent clause and the question tag to be full CPs whose TP complements are coordinated. With such a structural relation between the antecedent clause and the tag question, polarity reversal crucially depends on whether a negative feature is found inside the TP or not. With all this in mind, the derivation of sentences with negative quantifiers is discussed. Section 3.1.1 is devoted to object negative quantifiers, and Section 3.1.2 to subject and adjunct negative quantifiers.

3.1.1 Tag questions with negative quantifiers in object position

In this section I attribute the fact that some speakers can use a negative reverse polarity tag question with a negative antecedent clause to the existence of two different grammars that can be used to derive negative sentences with an object negative quantifier. Both grammars share the clausal structure given in (41) above, and involve Parallel Merge and multidominance for the derivation of object negative quantifiers, along the lines of what was shown in (24). Conversely, the two grammars differ in which polarity head (Pol1 or Pol2) is used to reverse the truth-conditions of the proposition. In one of the grammars (let us call it Grammar A), it is the TP-internal PolP2; in the other one (Grammar B), it is the TP-external PolP1. As shown in (43), negation remerges in Spec, PolP2 in Grammar A (i.e. negation remerges in a TP-internal position) and values the [upol: ] feature of Pol2 as [upol:neg]. Note that when PolP2 is active, PolP1 is not and vice versa.

By contrast, in Grammar B, in (44), PolP

![]() $_{1}$

is active.

$_{1}$

is active.

Thus, negation remerges in Spec, PolP1 and values the [upol: ] feature of Pol1 as [upol:neg]. The result is that the main clause is typed as negative but, crucially, there is no negative feature in any position inside the TP (as PolP1 is in a TP-external domain), which results in the (silent) or conjunction reversing positive polarity rather than negative. The question tag is, hence, negative. In both grammars, the Goal, negation, remerges in a position that allows the Probe (either Pol2 or Pol1) to have its [upol: ] feature checked.Footnote [18]

Given that negative quantifiers are decompositional, there is also the possibility that the negative part and the existential part of a negative quantifier merge in the structure independently from one another and surface discontinuously. That is, the host clause of the example in (1), repeated here as (45a) for convenience, could have also been Spelled-Out, as in (45b).

In (45b), negation would be first-merged in the vP-edge (i.e. inside the TP), thus being in the c-command domain of either PolP1 or PolP2, and making it possible for negation to remerge in a higher position than the one it has been first-merged (either Spec, PolP2 or Spec, PolP1 whenever the choice is free). The consequence of having negation first-merged in the vP-edge (i.e. TP-internally), however, is that a sentence such as (45b) can only take a positive reverse polarity question tag, as shown in (46).

This is indeed the case for all speakers of English independently of whether they use Grammar A or Grammar B for the syntax of object negative quantifiers.

3.1.2 Tag questions with negative quantifiers in subject and adjunct position

In this section I address why, unlike object negative quantifiers, subject and adjunct negative quantifiers only take a positive tag question in English. I argue that this is due to the fact that a restriction applies to negative quantifiers in the two syntactic positions under consideration that makes them essentially different from object negative quantifiers.

Following Temmerman (Reference Temmerman2012), who in turn follows Uriagereka (Reference Uriagereka, Epstein and Hornstein1999), I assume that complex left-branching phrase markers have to be Transferred before merging into the derivation (see footnote 13). Therefore, if a structure such as (23b) above, repeated here as (47) for convenience, is to be merged in Spec, vP, or adjoined to vP, it first needs to be Transferred and an interpretable negative feature is necessarily part of the TP.Footnote [19]

Something similar happens with adjunct negative quantifiers.Footnote [20] Let us assume that the adjunct negative quantifier in (2a), repeated here as (48), can be analyzed as in (49).

Given that (49) is, like (47), a complex syntactic object and, as such, it is Transferred before being merged as a vP-adjunct, an interpretable negative feature is found in the TP-domain, and so, the tag question has to be positive. Therefore, the two grammars postulated in Section 3.1.1, which may result in the opposite selection of reverse polarity tag questions for object negative quantifiers, converge into just one grammar in the case of subject and adjunct negative quantifiers. In both grammars, [upol: ] in Pol1 and Pol2 is valued by Agree with Neg in the vP.

Note that, as has been shown to be the case for object negative quantifiers in Section 3.1.1, it is also possible for negation not to merge with an existential at all. Rather, negation can first-merge in the edge of the vP, while the existential first-merges as the complement of V, thus resulting in the two parts of a potential negative quantifier being Spelled-Out independently from one another. This is shown in (50) for adjuncts.

As was also the case for (47), the tag question is necessarily positive, (51).

In short, in this section, I have assumed that the fact that negation and the existential quantifier are independent lexical items allows them to surface discontinuously, or as a single lexical item (i.e. as a negative quantifier). If negation is first-merged in the vP-edge and not with the existential, the antecedent clause takes a positive reverse polarity tag question, as there is a negative feature inside the TP.

Conversely, if negation is first-merged with the existential quantifier, the resulting syntactic object will be Spelled-Out as a negative quantifier. Being complex syntactic objects, subject and adjunct negative quantifiers will have to be Transferred before they merge in the vP. Hence, the presence of a negative feature inside the TP is guaranteed, imposing a positive question tag for all speakers.

The multidominant nature of negative quantifiers, however, interacts with the properties of the relevant polarity head when the quantifiers occur in object position. I have assumed that two different grammars are possible for English speakers. In one of the grammars (Grammar A), polarity is encoded in Pol2. This deactivates Pol1 as a Probe and forces the negative component in the negative quantifier to remerge in Spec, PolP2, in the TP-domain. As there is a negative feature inside the TP, the question tag has to be positive for speakers with this grammar. In the other grammar (Grammar B), by contrast, polarity is encoded in Pol1, which forces negation to remerge in Spec, PolP1, outside the TP-domain. The antecedent clause, then, is typed as negative, but the question tag is going to be negative, too, as there is no negative feature inside the TP, which is the part of structure that the question tag is sensitive to.

3.2 Neither-/so-coordination and either-/too-licensing

In this section, the analysis put forward in Section 3.1 is extended to account for the neither-/so-coordination facts described in (7) above, according to which an object negative quantifier can coordinate with a neither- or so-clause, whereas subject and adjunct negative quantifiers are only fine with a coordinated neither-clause. In a similar vein, I also try to account for the facts related to either-/too-licensing, like those in (6) above, according to which a clause with an object negative quantifier can license both either and too, but this is not the case with subject and adjunct negative quantifiers.

Let us address neither-/so-coordination first. Continuing to assume the existence of two different grammars, Grammar A and Grammar B, which diverge with respect to which Pol head is active (either Pol2, in the TP-domain, or Pol1, outside the TP-domain), so-coordination should be possible in Grammar B, as negation remerges in a position outside the TP. That is, if the negation in the object negative quantifier remerges in Spec, PolP1, the TP that sits in the Specifier of &P contains no negation and, hence, coordination must be with so. The structure is given in (52), where all the TP – except for the subject – in the coordinated so-clause is elided.

If, by contrast, negation remerges in Spec, PolP2 of the first conjunct (Grammar A), then there is a negative feature in the TP-domain and neither is required in the second conjunct CP for coordination. This is also what happens with subject and adjunct negative quantifiers. As discussed in the previous sections, these involve complex Specifiers that are Transferred prior to Merge, thus imposing an interpretable negative feature inside the TP that then values the [upol: ] feature of either Pol2 or Pol1 via Agree. Thus, neither-coordination is required in both grammars when the negative quantifier is in subject or in adjunct position.

With respect to either-/too-licensing, both polarity items are possible in clauses containing an object negative quantifier, (6a, a

![]() $^{\prime }$

). Again, this is predicted if negation can be inner (i.e. TP-internal, as in Grammar A), which licenses the negative polarity item either, or outer (TP-external, as in Grammar B), which makes it possible for the positive polarity item too to be licensed.

$^{\prime }$

). Again, this is predicted if negation can be inner (i.e. TP-internal, as in Grammar A), which licenses the negative polarity item either, or outer (TP-external, as in Grammar B), which makes it possible for the positive polarity item too to be licensed.

3.3 ‘Expression of agreement’ clauses

In this section, I briefly discuss the data involving ‘expression of agreement’ clauses presented earlier in (12)–(14). As was shown in (12a, b), clauses with object negative quantifiers agree both with Yes, I guess so and with No, I guess not ‘expression of agreement’ clauses.

Like for the other three sets of unexpected facts (namely (i) the occurrence of negative tag questions with object negative quantifiers, (ii) the possibility for a sentence containing an object negative quantifier to be coordinated with a so-clause, and (iii) the possibility for too to be licensed in a sentence containing an object negative quantifier), it is possible to accommodate the data in (12) within the two-grammars account. Assuming that ‘expression of agreement’ clauses constitute a CONFIRM speech act (see Krifka Reference Krifka2013), and that this involves expressing the same commitment expressed by the ASSERT speech act in the antecedent clause (see Farkas & Bruce Reference Farkas and Bruce2010), CONFIRM can apply to an ASSERT speech act that takes the TP as the propositional discourse referent (see González-Fuente et al. Reference González-Fuente, Tubau, Espinal and Prieto2015). In our analysis, this means that the propositional discourse referent on which ASSERT applies can be either

![]() $\neg p$

(if negation is TP-internal) or p (if negation is TP-external).

$\neg p$

(if negation is TP-internal) or p (if negation is TP-external).

In other words, given Speaker A’s utterance in (12), which contains an object negative quantifier, if Speaker B interprets the utterance as having been generated with Grammar A, where Pol2 is active and, hence, negation is TP-internal, the CONFIRM operator applies to ASSERT

![]() $\neg p$

, thus requiring the ‘expression of agreement’ clause No, I guess not, (53) (the strikethrough indicating ellipsis).

$\neg p$

, thus requiring the ‘expression of agreement’ clause No, I guess not, (53) (the strikethrough indicating ellipsis).

By contrast, if Speaker B interprets the utterance as having been derived by means of Grammar B, where Pol1 is active, CONFIRM applies on ASSERT p (since TP, the propositional discourse referent, contains no negation). This means that the ‘expression of agreement’ clause Yes, I guess so will be required, (54).

4 Conclusion

In this paper, I have provided an explanation as to why for some speakers of English negative sentences containing an object negative quantifier (but not a subject negative quantifier, or an adjunct negative quantifier) can (i) co-occur with a negative reverse polarity question tag, (ii) be coordinated with a neither-clause, (iii) license the polarity item too, and (iv) occur with a Yes, I guess so ‘expression of agreement’ clause. I have claimed that these facts can be accommodated within a decompositional and multidominant approach to negative quantifiers in English on the assumption that two distinct positions for the expression of negation (one below TP and one above) exist, which results in two grammars available to English speakers.

The analysis of negative quantifiers as decomposable into a negative and an existential part allows negation to enjoy (re)merging flexibility, while the existence of two possible grammars explains that for some speakers an asymmetry exists between object negative quantifiers, on the one hand, and subject and adjunct negative quantifiers on the other. While sentences with subject and adjunct negative quantifiers uniformly (i) select a positive reverse polarity question tag, (ii) occur with a neither-coordinated clause, (iii) license either, and (iv) are followed by a No, I guess not ‘expression of agreement’ clause, sentences with object negative quantifiers may (i) occur with negative question tags, (ii) occur with a so-coordinated clause, (iii) license too, and (iv) be followed by a Yes, I guess so ‘expression of agreement’ clause for some speakers.

The existence of Grammar A and B has been claimed to follow from the availability of two different positions for negation in English (one below TP, and one above TP). As discussed in this paper, such difference has consequences not only for the choice of the polarity of question tags when associated to antecedent clauses that contain object negative quantifiers, but also for neither-/so-coordination, either-/too-licensing, and the choice of ‘expression of agreement’ clauses. If it is the case that Pol1 is the active polarity head, a negation that is ultimately part of a negative quantifier values the feature [upol: ] in Pol1 by remerging TP-externally (i.e. by remerging in Spec, PolP1), which results in object negative quantifiers typing the clause as negative without their negative feature being part of the TP. Furthermore, in both grammars, subject and adjunct negative quantifiers have to be Transferred before merging in Spec, vP (subjects) or at the edge of the vP (adjuncts) by virtue of being complex syntactic objects. This results in a negative feature always being part of the antecedent clause TP in both grammars and, hence, a completely uniform and expected behavior of subject and adjunct negative quantifiers with respect to polarity.

As it has been assumed that the antecedent clause and the question tag, on the one hand, and the two conjunct clauses in neither-/so-coordination, on the other, relate by means of coordination of their TPs, only material that sits inside the antecedent/first conjunct clause TP can be relevant for the second conjunct (i.e. the question tag, and the neither/so coordinated clause). In particular, I have assumed that question tags are full CPs with VPE, and that the TP of the antecedent clause and the TP of the question tag are coordinated by means of a silent disjunctive conjunction or that is responsible for the two coordinates having opposite polarities. For neither-/so-clauses I have assumed and to be the head of the &P projection, thus resulting in a structure that is comparable to the one assumed for clauses with tag questions. This is the reason why only a grammar that allows the negative component of a (decompositional and multidominant) object negative quantifier to remerge directly outside the TP (i.e. in Spec, PolP1) can derive a negative antecedent clause containing an object negative quantifier with a negative reverse polarity question tag, or with a so-coordinated clause. In a similar vein, I have also discussed the asymmetry of either-/too-licensing for object negative quantifiers on the one hand, and for subject and adjunct negative quantifiers on the other as resulting from the possibility of having inner vs. outer negation (understood as TP-internal vs. TP-external negation).

Finally, I have also briefly shown that it is possible to make this analysis compatible with the facts observed with ‘expression of agreement’ clauses, which involve the CONFIRM and ASSERT speech acts. Given that TP is the propositional discourse referent onto which the ASSERT operator applies, whether negation is TP-internal or TP-external when object negative quantifiers are involved becomes relevant. Again, subject and adjunct negative quantifiers expectedly do not show the asymmetry that is observed with object negative quantifiers, as they always involve an interpretable negative feature inside the TP.