1 Introduction

A central question regarding the interface between syntax and semantics is the mapping of the participants of an event to a verb’s syntactic argument positions and the degree to which this relationship is mediated by lexical entailments associated with those participants. Although considerable lexical semantic work has addressed this question from a variety of theoretical perspectives, the majority of this work has focused on Indo-European languages and phenomena typical of those languages (such as dative shift). In a separate vein, a large body of research on Bantu languages has focused on the question of the grammatical function of applied objects that are licensed by applicative morphemes. In this paper, I set out to link these two domains by reframing the discussion of so-called ‘object symmetry’, and to do so, I investigate the degree to which the lexical entailments associated with a given applied object correlate with the syntax of the applicative head. Ultimately, I make two interrelated claims about the syntax and semantics of applied objects, which bear not only on the empirical facts related to applicative morphology in Bantu but also the nature of the interface between syntax and semantics more broadly.

First, I show that formally there is no need to assume a correlation between thematic role and the syntactic structure (which thus derives the ‘(a)symmetry’ between objects on many views), and I then argue that applied objects should in fact not universally correspond to a particular syntax based on their meaning. Building on previous work in which applicative heads are claimed to differ in their position in relation to the V head in a division known as ‘high’ and ‘low’ applicatives, I assume (with various others) that high applicatives are symmetrical and low applicatives are asymmetrical, but I propose that languages vary in which type of applicative appears with either high or low structures. Crucially, the pairing of high or low syntax with a particular applied object is not determined by the ‘thematic role’ (which I separately address) of the applied object, but rather is arbitrarily conventionalized in a particular language.

Second, building on decades of lexical semantic work that has raised many empirical and theoretical issues with the notion of thematic roles, I argue that the linking of particular applied object types to specific patterns of symmetry is not (and in fact, cannot be) driven by their thematic role; rather, the types of applied objects that are observed arise from combinations of other facts about the applied object. I claim that two aspects of Bantu applied objects can capture the most frequently discussed applied object types in these languages: animacy of the applied object and morphological marking with locative class prefixes. I argue that particular combinations of animacy/locative marking of a given applied object are linked to a particular applied object type (e.g. so-called ‘benefactive’ or ‘locative’ applicatives), which is in turn associated with one of the two possible applicative head types (high or low) in a given language. This allows us to investigate the syntax of applied objects without relying on the problematized notion of thematic roles.

This account makes various predictions about the syntax and semantics of applied objects: first, it predicts that the semantics of an applicative in a particular language does not necessarily pattern with any specific syntactic properties, and I show that this mismatch arises with Kinyarwanda (Bantu; Rwanda) applicatives, where despite being syntactically ‘high’, there are cases where the applicative is semantically ‘low’, which is a problem for previous accounts but follows from the analysis proposed here. Second, I assume an account in which high applicatives are symmetrical and low applicatives are asymmetrical, but by the nature of these structures, it is predicted that there should still be an asymmetry in c-command facts regardless of symmetry with other diagnostics. I present data from Kinyarwanda that show that this is borne out. Finally, on the view proposed here, it is expected that languages vary in the syntactic behavior different applied object types exhibit with regard to symmetry; crucially, there should be no universal tendencies based on the semantics of the applied object. With comparative data from several Bantu languages, I show that these various predictions indeed come to bear, and it emerges that the degree to which applied object type affects symmetry properties, it does not universally capture the variation among languages. Specifically, I show that there exist opposite symmetry patterns from different languages for each of the applied object types, which is problematic for accounts that assume that thematic role correlates with a particular grammatical function. On the framework outlined here, the observed cross-linguistic variation follows naturally.

The structure of the paper is as follows. In Section 2, I provide a brief overview of the literature on the syntax of applied objects in Bantu languages. In Section 3, I show there is no formal reason to assume that the semantics and syntax of an applicative must correlate, and I then propose a revised semantics for high and low applicatives that allows for variation in the semantic contributions of different applicative heads. Section 4 summarizes some of the main issues with thematic roles discussed in earlier lexical semantic work, and I show that, despite this, thematic roles have persisted (albeit often indirectly) as an explanatory device in much of the current work on applied objects. Bringing the points in Sections 3 and 4 together, I lay out three predictions of the analysis in Section 5. I conclude the discussion in Section 6 and point to questions that remain for future work on both applied objects and argument realization more generally.

2 Background: the syntax of applied objects

The applicative morpheme is traditionally understood as a verbal suffix that has the function of adding a new object to the argument structure of a verb and assigning a thematic role to that object (Dixon & Aikhenvald Reference Dixon, Aikhenvald, Bybee, Haiman and Thompson1997, Peterson Reference Peterson2007). Applicative morphology is found in many languages of the world, and Bantu languages have been of particular interest given the microvariation in the syntax of cognate applicative suffixes. Consider the data in (1) from Chicheŵa (Bantu; Malawi), where the applicative morpheme –ir adds an additional object mwana ‘child’ in (1b).Footnote [2]

When the applicative is used with transitive verbs such as ku-manga ‘to build’, the resultant verb in (1b) is a derived ditransitive with two objects. A heavily debated topic in the syntax of applicatives has been whether the grammatical function of the applied object (i.e. the object licensed by the applicative) is similar or different from the grammatical function of the verbal object (i.e. the object licensed by the non-applied transitive verb) and why such (a)symmetry may arise between the two (Kisseberth & Abasheikh Reference Kisseberth, Abasheikh, Cole and Sadock1977, Gary & Keenan Reference Gary, Keenan, Cole and Sadock1977, Kimenyi Reference Kimenyi1980, Perlmutter & Postal Reference Perlmutter, Postal and Perlmutter1983, Baker Reference Baker1988b, Bresnan & Moshi Reference Bresnan and Moshi1990, Alsina & Mchombo Reference Alsina, Mchombo and Mchombo1993, McGinnis Reference McGinnis2001, McGinnis & Gerdts Reference McGinnis and Gerdts2003, Ngonyani & Githinji Reference Ngonyani and Githinji2006, Jeong Reference Jeong2007, Zeller Reference Zeller2015, van der Wal Reference van der Wal, Sheehan and Bailey2017, Ackerman, Malouf & Moore Reference Ackerman, Malouf and Moore2017, inter alia). Several grammatical tests have been used to diagnose the grammatical function of the two ostensible objects.

One such diagnostic is whether either object can be the subject of a passive. In (2), we see two examples of passive counterparts to the sentence in (1b), as indicated by the passive suffix –idw on the verb ku-manga ‘to build’. The difference between the two sentences is that in (2a), the Beneficiary applied object is permitted as the subject of a passive, while the verbal object in (2b) is not.

Similarly, only the Beneficiary object can appear as an object pronoun on the verb, as in (3a); the verbal object in (3b), on the other hand, cannot be an object pronoun.

From diagnostics such as passivization and object markingFootnote [3] (as well as a variety of others, such as whether the argument can be extracted in a relative clause and restrictions of order between the two objects), the applied and verbal objects in (1b) are considered ‘asymmetrical’ (an observation for Chicheŵa going back to at least Baker Reference Baker1988b); the objecthood properties differ between the two, and the applied object has preference in positions generally reserved for the single object of a transitive verb. As I discuss in detail in Section 5.3, considerable variation has been observed across Bantu languages in the objecthood properties of applied objects, and several different ideas have been put forward to explain these patterns within and across languages, as I summarize in Section 2.1.

It is important to note that for some authors, such as Bresnan & Moshi (Reference Bresnan and Moshi1990), the crucial evidence of true ‘symmetry’ between the grammatical functions (in other words, that both have true access to objecthood diagnostics) is that both objects can undergo these diagnostics simultaneously – e.g. the verbal object is the subject of a passive while the applied object is object-marked. However, I contend that this is not necessary to show that two objects have the same or different status with respect to their grammatical functions, and subsequent work has shown that whether multiple objects show objecthood properties simultaneously is a separate parameter of variation (see, e.g. Marten, Kula & Thwhala Reference Marten, Kula and Thwhala2007). Thus, in this paper I define a symmetrical construction as one in which either object has access to objecthood diagnostics (referred to as ‘alternating’ in Alsina Reference Alsina1996) and an asymmetrical construction as one in which the verbal object is prevented from access to these diagnostics in the presence of an applied object. As discussed in detail in Section 5.3, it is crucially not the case that a language itself is symmetrical or asymmetrical (though this has sometimes been assumed), but rather, a specific applicative type in a given language is symmetrical or asymmetrical.

2.1 Previous approaches to the syntax of applied objects

The first wave of generative work on object symmetry analyzed applicativization as an operation that promotes an oblique to a full object (Gary & Keenan Reference Gary, Keenan, Cole and Sadock1977, Kisseberth & Abasheikh Reference Kisseberth, Abasheikh, Cole and Sadock1977, Kimenyi Reference Kimenyi1980, Dryer Reference Dryer and Perlmutter1983, Perlmutter & Postal Reference Perlmutter, Postal and Perlmutter1983). One claim is that there is no grammatical distinction between the applied and verbal objects in certain languages such as Kinyarwanda, where objects are generally assumed to be symmetrical (Gary & Keenan Reference Gary, Keenan, Cole and Sadock1977, but see Dryer Reference Dryer and Perlmutter1983 for some asymmetries in Kinyarwanda). Other languages such as Chimwi:ni (Bantu; Somalia) differ in that the two objects do not share the same syntactic behavior, and for these cases, Kisseberth & Abasheikh (Reference Kisseberth, Abasheikh, Cole and Sadock1977) propose that applicativization puts the verbal object en chômage, a special grammatical relation in Relational Grammar for objects that have been demoted from full object status. The chômeur is no longer able to undergo objecthood operations such as raising in passivization, thus capturing the asymmetries between the applied and verbal objects.

In a different framework, Baker (Reference Baker1988a, Reference Bakerb) argues that the differences in the symmetry patterns of thematic roles correspond to differences in the assignment of Case. Comparing instrumental and benefactive applicatives in Chicheŵa, Baker argues that Instrument applied objects are assigned inherent Case by the verb, while Beneficiary applied objects receive structural Case from a null preposition. Due to being assigned structural Case, two predictions arise regarding Beneficiary applied objects. First, arguments that receive structural Case must precede those that receive inherent Case. Furthermore, on the assumption that object markers are only permitted for arguments checked for structural Case, it is predicted that the Beneficiary can be object-marked, while the verbal object (which gets inherent Case) cannot. With instrumental applicatives, either the Instrument applied object or the verbal object can receive inherent Case, so word order is predicted to be free, and either object (but not both) is permitted to be object-marked on the verb. In short, Baker (Reference Baker1988b) captures the differences between Instrument and Beneficiary applied objects by proposing that the former can receive inherent Case, while the latter cannot.

In response to Baker, Alsina & Mchombo (Reference Alsina and Mchombo1990, Reference Alsina, Mchombo and Mchombo1993) argue instead that the distinction arises from the position of an applied object’s associated thematic role on the thematic role hierarchy in (4), adopted from Bresnan & Kanerva (Reference Bresnan and Kanerva1989). Using Lexical Functional Grammar’s Lexical Mapping Theory, which deconstructs grammatical functions via the features [

![]() $\pm$

o] for objective (whether the grammatical function is a type of object) and [

$\pm$

o] for objective (whether the grammatical function is a type of object) and [

![]() $\pm$

r] for restricted (whether the grammatical function is restricted to a specific set of thematic roles), they propose that while any internal argument can receive the intrinsic classification of [–r], any internal role hierarchically lower than Goal/Experiencer can alternatively have the intrinsic classification of [+o].

$\pm$

r] for restricted (whether the grammatical function is restricted to a specific set of thematic roles), they propose that while any internal argument can receive the intrinsic classification of [–r], any internal role hierarchically lower than Goal/Experiencer can alternatively have the intrinsic classification of [+o].

Given its position in the hierarchy, the Beneficiary applied object can only have the intrinsic classification of [–r], while the Instrumental object can be assigned either [–r] or [+o]. In an applied predicate, the Beneficiary is unrestricted (namely, it is the ‘core’ object) while the theme is the restricted object, meaning the Beneficiary applied object must precede the verbal object and can also be object-marked. With instrumental applicatives, on the other hand, either the Instrument applied object or the verbal object can receive either intrinsic classification, meaning that word order is free and both can be object-marked on the verb – thus capturing the Chicheŵa facts. On this view, the position of the thematic role of the applied object determines its intrinsic classification, which in turn derives the grammatical functions of the applied and verbal objects.

Bresnan & Moshi (Reference Bresnan and Moshi1990) expand on Alsina & Mchombo’s (Reference Alsina, Mchombo and Mchombo1993) analysis in an attempt to tackle variation of applicative behavior across different languages’ Beneficiary objects, and they propose a parameter of variation in which certain languages prohibit two arguments from having the object grammatical function. In the terminology of the Lexical Mapping Theory which they use, the constraint is that only one theta role can be intrinsically classified with the feature [–r] in some languages. This has the result of an asymmetry between the applied and verbal objects since only the applied object is unrestricted (e.g. able to be the subject of a passive). Other languages lack the restriction on the number of roles that may be assigned the [–r] feature, permitting that two roles may simultaneously be intrinsically classified with the [–r] feature; these latter languages are those where there is object symmetry and both the thematic and applied objects can be, e.g. subjects of passives. The generalization, then, is that languages parametrically differ in whether they allow multiple intrinsic classifications of [–r], and it is those languages that do not allow multiple [–r] classifications which have asymmetrical scenarios for benefactive applicatives.

Many recent approaches make use of Pylkkänen’s (Reference Pylkkänen2008) distinction between so-called ‘high’ and ‘low’ applicatives to capture object symmetry facts. In Pylkkänen’s original typology, these two types of applicative head differ in how the applied object is related to the verb. While the high applicative in (5a) relates an event to an individual, the low applicative head in (5b) relates two individuals.

The high–low typology was originally proposed to capture an array of facts separate from object symmetry. For example, because low applicatives relate two participants, Pylkkänen proposes that they are unable to combine with unergative verbs (which only have an external argument, and thus no verbal object).

Various approaches have adopted this distinction in capturing differences in objecthood between the applied and verbal object, but the details of what drives the difference between high and low applicatives are debated. Broadly, there have been three aspects of grammar that have been proposed to underlie object symmetry facts: phases, locality, and Case assignment. First, work by McGinnis (Reference McGinnis, Kim and Strauus2000, Reference McGinnis2001) and McGinnis & Gerdts (Reference McGinnis and Gerdts2003) invokes phases (cf. Chomsky Reference Chomsky and Kenstowicz2001) as a means for capturing symmetry patterns in Kinyarwanda. With the high applicative, the applied and verbal objects are in separate phases (on the stipulation that the sister to VP – and thus the high applicative head – is a phase boundary), while with the low applicative, both objects are in the same phase. A-movement respects locality; thus a lower argument can raise to the subject position with the high applicative because a phase-EPP feature can be added to the high applicative in the passive, allowing the lower argument to leapfrog over the higher one. Once the verbal object occupies a higher specifier of high applicative head, it is the closest DP to T, and it can move to spec-T. With the low applicative, on the other hand, the ApplP is not a phase, and no phase-EPP feature can be added. Hence, the lower object cannot raise higher than the applied object.

Another approach is that (a)symmetries arise from (anti-)locality conditions (Anagnostopoulou Reference Anagnostopoulou2003, Jeong Reference Jeong2007, Zeller Reference Zeller2015). For example, Jeong (Reference Jeong2007) argues for dispensing with the use of phases in ditransitive structures, and she instead proposes that anti-locality constraints alone can derive the distinction between high and low applicatives. Citing Grohmann’s (Reference Grohmann2003: 26) anti-locality hypothesis, which states that ‘movement must not be too local’, Jeong shows that with high applicatives, because the verbal object and applied object are in separate phrasal projections (i.e. separated by VP), the verbal object can adjoin to the outer specifier of HApplP. With LApplP, on the other hand, anti-locality prevents the lower verbal object from moving across the higher applied object since they are in the same projection. The default for Jeong, then, is that when high, the applicative is symmetrical and when low, the applicative structure is asymmetrical, though various language-specific facts, such as inherent Case assignment, may affect this picture (see pp. 42ff. for detailed discussion).

Finally, others have proposed that Case (and perhaps some interaction with locality) is what determines symmetry properties (Haddican & Holmberg Reference Haddican and Holmberg2012, Reference Haddican, Holmberg, Veselovská and Janebová2015, van der Wal Reference van der Wal, Sheehan and Bailey2017, Holmberg, Sheehan & van der Wal Reference Holmberg, Sheehan and van der Wal2019). For example, Holmberg et al. (Reference Holmberg, Sheehan and van der Wal2019) propose that symmetry in double object constructions arises from a combination of Case assignment and movement to the phase edge (assumed to be ApplP; see also McGinnis Reference McGinnis2001). For a symmetrical passive construction, the Appl head (which is High in the Pylkkänen sense given that it is external to the VP) can assign Case to either the Theme or the Recipient. When Case is assigned to the verbal object, the Recipient gets Case from T, which in turn attracts the Recipient to Spec TP; when Case is assigned to the Recipient, it becomes deactivated and leaves the verbal object with an unvalued uCase feature, and the Theme thus moves to the phase edge in the outer specifier of the Appl phrase. Variation in languages comes from this latter Case assignment possibility being disallowed for asymmetrical constructions.

What these three general views share is the assumption that there is a fundamental syntactic difference that underlies symmetrical and asymmetrical constructions, but what differs is how Case is assigned to the two objects, whether locality alone derives the differences, and/or whether the two objects are in the same phase. Behind many of these views is a crucial distinction between high and low applicative heads, with the general consensus (despite different grammatical facts that drive it) being that high applicatives put the verbal and applied objects in a situation that gives them equal access to positions that correspond to object status, while low applicatives put the verbal and applied objects in a situation that gives them unequal access to positions that correspond to object status. In the latter situation, it is only the applied object – by virtue of being higher in the structure – which is able to, for example, raise to be the subject of a passive.

What has not been the focus of previous work is the role of the meaning of the applied object in determining object symmetry facts; rather, thematic role is generally assumed to determine the categorization of a particular applied object as symmetrical or asymmetrical (though mediated through constructs like thematic role hierarchies or differences in Case assignment). My focus in the present paper is to analyze the semantic contributions of applicatives and how (and whether) thematic role can correlate with particular object symmetry facts. For the sake of exposition, I assume Pylkkänen’s (Reference Pylkkänen2008) distinction between high and low applicatives and Jeong’s (Reference Jeong2007) proposal that anti-locality captures the observed (a)symmetries; thus, the working assumption is that high applicatives are symmetrical and low applicatives are asymmetrical. While the choice of anti-locality as driving objecthood facts is not central to the discussion that follows and the analysis I sketch below is likely to be equally compatible with any of them, I note that among the previous accounts, the anti-locality view is the simplest in that it does not require any further stipulation beyond the syntactic structure of high and low applicatives – i.e. there is no need to propose phase boundaries or Case-assigning differences in addition to the syntactic facts that come for free from the syntax of high and low applicative heads.

Before moving on, it is worth noting that Ackerman et al. (Reference Ackerman, Malouf and Moore2017) criticize the view that symmetrical objects derive from a syntactic structure that is asymmetrical, as is the case with the structures in (5), where the high applicative puts the two arguments in an asymmetrical (c-command) relationship but results in the two being symmetrical in terms of their objecthood diagnostics. Ackerman et al. present evidence from the Kordofanian language Moro, and they suggest that there is no reason to assume an asymmetrical system. They capture this by proposing that for Moro, the argument with the most Proto-Agent properties will be mapped to Subject, and all remaining arguments are unordered in the predicate’s arg-st. In many ways, their criticisms fit with the points raised in this paper (especially their critical view of the overlinking of syntax and semantics, fitting with the point I make in the next section). However, they do not centrally discuss the variation among languages’ symmetry facts, and I show in Section 5.3 that asymmetry is the default in certain languages. Ultimately, while I implement the high–low distinction as a starting point for building an analysis, my focus is the lexical semantic component of the interface between the linking of semantic participants to syntactic arguments – a point which in principle can be implemented in any syntactic framework and is consistent with many of the facts that Ackerman et al. (Reference Ackerman, Malouf and Moore2017) present for Moro. I turn to my proposal in the next section.

3 Applicatives and the syntax–semantics interface

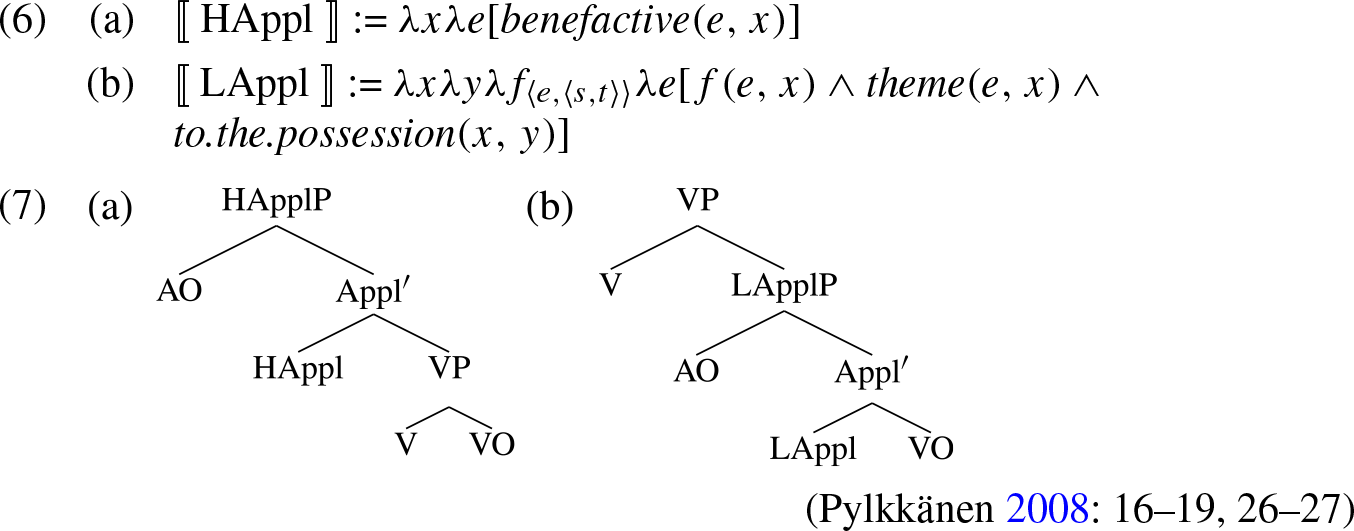

The typology between high and low applicatives was originally proposed by Pylkkänen (Reference Pylkkänen2008) to capture syntactic and semantic properties of different applied objects. Pylkkänen provides the denotations in (6a) and (6b) for high and low applicatives, respectively. The corresponding syntactic structures are repeated from (5) in (7a–b).

The high applicative head (6a) takes an argument and an event variable as input and states that the thematic role of the individual argument is a Beneficiary; Pylkkänen assumes it combines with the VP by event identification (cf. Kratzer Reference Kratzer, Rooryck and Zaring1996). The low applicative in (6b), unlike the high applicative, has two individual arguments – one corresponding to the applied object and the other to the verbal object. Pylkkänen argues that the semantics of the low applicative is not simply a general Beneficiary, but rather, the low applicative specifies a relation of transfer of the verbal object into the possession of the applied object – fitting with the fact that the denotation relates two individuals. The central claim of Pylkkänen’s analysis is that the syntactic structure and semantic interpretation of applicative heads vary in tandem; namely, the difference in syntax corresponds to a different semantics. I argue in this section that variation in the semantics of the applicatives does not in fact have to be linked to variation in the syntax, and, crucially, there is no formal restriction on the two being independent of one another.

With high applicatives, the applicative head introduces an argument that is external to the VP. Pylkkänen (Reference Pylkkänen2008: 5–6) draws the parallel between the nature of the high applicative and Kratzer’s (Reference Kratzer, Rooryck and Zaring1996) proposal that external arguments are licensed by a VP-dominating voice head. In order to tease apart the assumptions of the semantics of high applicatives, it is helpful to first consider the details of the analysis of external arguments proposed by Kratzer (Reference Kratzer, Rooryck and Zaring1996). She argues that external arguments are licensed by a separate head from the main verb (now often referred to as the ‘little-v hypothesis’), as in (8).

The intuition behind this analysis is that the external argument is not semantically linked to the main verb and is instead licensed by an external voice head.

A key piece of empirical evidence for the claim that external arguments are not arguments of the verb is that external arguments cannot form idioms with the verb to the exclusion of the internal object(s), often referred to as ‘Marantz’s Generalization’ (cf. Marantz Reference Marantz1984). Examples of such verb–object idioms are those in (9) and (10).

Kratzer points out that with certain verb–object idioms, the verb semantically selects for a property of the object, such as the verb kill on the ‘waste’ idiomatic interpretation in (11), where the object must have the property of being an interval of time.

The data in (11) show cases in which the verb conditions the interpretation of the object by requiring the object to be an interval of time (such that the time interval can be idiomatically ‘killed’). These kinds of conditions on internal arguments are frequent and, crucially, they are distinct from the relationship between the verb and the external object, which are claimed to be ruled out as a possible formation for idioms.Footnote [4]

Returning to the little-v hypothesis, Kratzer argues that if the external argument is specified as an argument of the verb, then there is no technical obstacle to a verb stating conditions about the external argument, and this is undesired if we want to capture the generalization that external arguments tend to not form idioms with the verb to the exclusion of the internal object(s).Footnote

[5]

If external arguments are arguments of the verb, there is nothing preventing conditions such as those in (12), where

![]() $f$

is a function that yields an output for the individuals

$f$

is a function that yields an output for the individuals

![]() $b$

(the referent of the subject) and

$b$

(the referent of the subject) and

![]() $a$

(the referent of the object).

$a$

(the referent of the object).

For Kratzer, conditions of the type in (12) are not desired if Marantz’s Generalization is to be maintained; if the external argument is an argument of the verb, there is nothing preventing the verb from specifying restrictions of the type in (12) on the external argument. However, if the external argument is not an argument of the verb, then no such conditions on the external argument should be possible. From this, she proposes that the semantic conditions on the external argument come instead from the voice head, thus separating the semantic relationship between the verb and external argument.

Wechsler (Reference Wechsler, Vulchanova and Afarli2005), however, shows that there is in fact no technical obstacle to reformulating the conditions in (12) in terms of the voice head Kratzer proposes. He gives the revised conditions in (13), which specify conditions on ‘the Agent of

![]() $e$

’, which refers to the external argument that on Kratzer’s approach is licensed outside the verbal projection via the voice head. Crucially, the conditions in (13) can be stated at the level of ‘big V’ – even when the external argument is licensed by voiceP.

$e$

’, which refers to the external argument that on Kratzer’s approach is licensed outside the verbal projection via the voice head. Crucially, the conditions in (13) can be stated at the level of ‘big V’ – even when the external argument is licensed by voiceP.

The conditions in (13) specify properties of the external argument by making reference to the ‘Agent of

![]() $e$

’. Having the selectional restrictions mediated through the event argument in (13) has the same effect as Kratzer’s undesired restrictions in (12), showing that the little-v hypothesis does not solve the problem it sets out to solve. More broadly, we can conclude from this that semantic conditions can be stated about arguments that do not directly combine with a particular head, and therefore it is not necessarily the syntactic structure itself which restricts the stating of particular conditions on certain arguments.

$e$

’. Having the selectional restrictions mediated through the event argument in (13) has the same effect as Kratzer’s undesired restrictions in (12), showing that the little-v hypothesis does not solve the problem it sets out to solve. More broadly, we can conclude from this that semantic conditions can be stated about arguments that do not directly combine with a particular head, and therefore it is not necessarily the syntactic structure itself which restricts the stating of particular conditions on certain arguments.

Returning to the high–low typology, the semantics in (6) rely on similar assumptions to the little-v hypothesis; namely, by virtue of the high applicative being external to the VP, the applied and verbal objects are in separate domains, and it has been generally assumed that the transfer-of-possession reading is not available with the high applicative. However, in the same way Wechsler (Reference Wechsler, Vulchanova and Afarli2005) shows that there is no formal obstacle to stating conditions about the external argument on a little-v account, there is no technical reason that the transfer-of-possession reading cannot be indicated on the high applicative, despite the widespread assumption that this is the case. Specifically, nothing prevents us from proposing the condition in (14) on the meaning of a high applicative, wherein

![]() $a$

is the argument licensed by the applicative and

$a$

is the argument licensed by the applicative and

![]() $f$

is a relation contributed by the applicative.

$f$

is a relation contributed by the applicative.

Here, the interpretation of the high applicative is contingent upon the applied object (

![]() $a$

) receiving the ‘Theme of

$a$

) receiving the ‘Theme of

![]() $e$

’. Thus, despite the fact that the high applicative does not license the Theme, nothing formally prevents specifying a transfer-of-possession reading, comparable to the way that nothing prevents the main verb from specifying conditions on the external argument in (13).

$e$

’. Thus, despite the fact that the high applicative does not license the Theme, nothing formally prevents specifying a transfer-of-possession reading, comparable to the way that nothing prevents the main verb from specifying conditions on the external argument in (13).

Compositionally, one way to capture the generalization in (14) is to define a Recipient role that states that the participant receives some entity, though it is crucial that the meaning also indicate which entity undergoes transfer of possession. To resolve this, a further condition needs to be stated that any item received must be the Theme of the verb (capturing the intuition that the Recipient comes into possession of the Theme and not just any item – the same relation as Pylkkänen’s ‘to the possession’). The denotation of a high applicative with a transfer-of-possession reading would therefore be the following:

The composition of the head in (15) proceeds exactly as the high applicative in Pylkkänen’s proposal, but with the crucial difference being that this high applicative specifies transfer of possession of the Theme to the Recipient.

Conversely, there is no formal barrier that prevents the low applicative from having a general Beneficiary reading, as in the denotation in (16):

The denotation in (16) is that of a general Beneficiary reading, and it is equally compatible with the low applicative syntax in (7b) as the denotation Pylkkänen gives in (6b) for the transfer-of-possession reading.Footnote [6]

Given that any syntactic structure can in principle be associated with any semantics, the null hypothesis is that there should not be a correlation between the syntax of an applicative and its interpretation. Therefore, high and low applicatives can be associated with either a general Beneficiary or transfer-of-possession Beneficiary reading:

To summarize, a particular applicative head can in principle have either a general Beneficiary or transfer-of-possession reading, with no formal requirement that a high or low applicative be linked to a specific semantics.

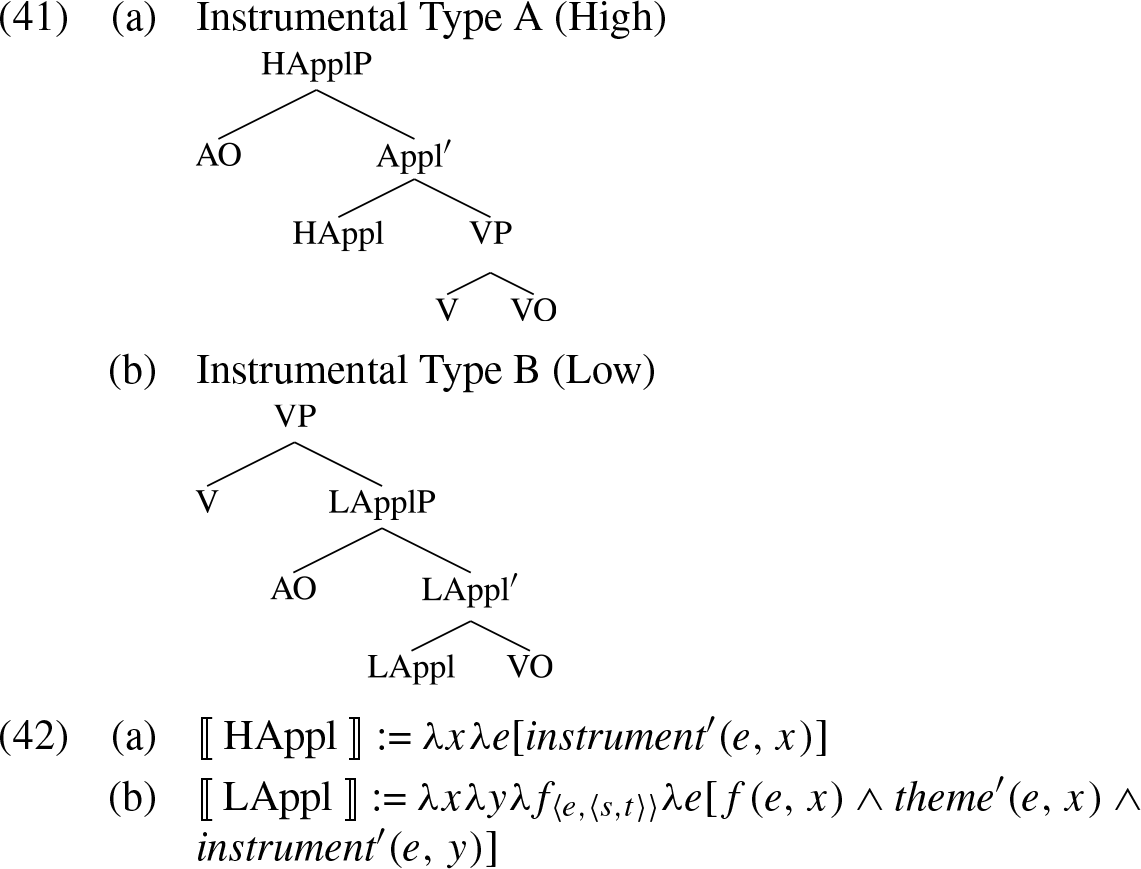

So far, the discussion has centered around benefactive applicatives, which were the focus of the original proposal for the high–low typology in Pylkkänen (Reference Pylkkänen2008). However, most Bantu languages have an applicative morpheme that licenses a variety of roles (though I revisit the notion of thematic roles in the next section). Expanding the discussion of the semantics from just benefactive applicatives, I propose that either high or low applicative syntax can in principle be associated with any thematic applicative type, such as Instrument, Locative, etc. Taking Instrument applied objects as an example, the denotations in (19) indicate the possible semantics of a high or low applicative morpheme associated with an Instrument role (and mutatis mutandis for other roles, like Locative).

In (19), a denotation for an instrumental applicative exists for both a high and a low applicative structure.

With this background, I propose that in a given language, a particular applicative type (e.g. benefactive, instrumental, etc.) is arbitrarily linked to either a high or a low structure and will in turn be symmetrical or asymmetrical, given the assumption regarding anti-locality discussed in Section 2.1 that high applicatives are symmetrical and low applicatives are asymmetrical. For example, a benefactive applicative could be high in one language and low in another, yet in both languages have a general benefactive reading. Furthermore, the categorization of one applicative type, such as benefactive, has no bearing on another, such as the instrumental. I discuss the predictions about the variation in object symmetry facts across Bantu languages in more detail in Section 4.3.

Some of the ideas of this proposal are reminiscent of those in Wood & Marantz (Reference Wood, Marantz, D’Alessandro, Franco and Gallego2017), who note that the same meanings can be expressed by different functional heads and vice versa. They argue that various types of argument-licensing heads (e.g. little-v, appl, voice, etc.) can be reduced to a single argument introducer, i*, and the observed differences in these heads arise from differences in the syntactic context in which i* appears (see Wood Reference Wood2015 for an overview of the semantics they assume). The interpretation of a particular head is determined by its position in the syntax at LF. While their ultimate goals and conclusion are quite different, the present paper argues for the parallel intuition that argument-licensing heads (here, high and low applicative heads) are not universally tied to a particular semantics.

Before moving forward, it is worth nothing that while I formulate this proposal in terms of Minimalist research on high and low applicative heads, the problems I lay out here pose similar issues for other frameworks. For example, in Lexical Functional Grammar (LFG), Alsina & Mchombo (Reference Alsina, Mchombo and Mchombo1993) link thematic role directly to the mapping of particular arguments, but the claim here is that a specific meaning (including thematic role) cannot be tied universally to a particular syntax of a given applicative type (see Jerro Reference Jerro, Boyer, Kramer and Zsiga2015 for issues specific to LFG and a possible solution). The crucial point for any framework is that there is no inherent link between the semantic contribution of the applicative and its syntactic structure.

4 Types of applied objects

In previous literature on object symmetries (see citations in Section 2.1), the notion of thematic role has been central (explicitly or implicitly, depending on the framework) in deriving the patterns of (a)symmetry, but in this section I show that a separate literature has raised several issues with the assumption that thematic roles should serve as a theoretical basis for deriving argument realization. I present several of these points, and then I propose a preliminary categorization of applied objects that obviates the need for relying on thematic roles in analyzing object symmetries in Bantu languages.

4.1 Problems for thematic roles

The use of thematic roles for deriving argument realization goes back to the earliest days of generative grammar (e.g. Fillmore Reference Fillmore, Bach and Harms1968, Reference Fillmore, Jacobs and Rosenbaum1970, Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1972, Reference Jackendoff1976). However, considerable research has shown that using thematic roles as a means for deriving argument structural generalizations results in various problems (see, e.g. Zubizarreta Reference Zubizarreta1987, Rappaport & Levin Reference Rappaport, Levin and Wilkins1988, Dowty Reference Dowty, Chierchia, Partee and Turner1989, inter alia), and instead, the mainstay of work on the semantics of argument realization looks at how the event structure and the lexical entailments of individual participants (as defined by a particular verb) derive the mapping of verbal arguments. Levin & Rappaport Hovav (Reference Levin and Hovav2005: 38–49), and the literature cited therein, summarize a variety of issues that the literature has brought forward against the use of thematic roles. While I cannot dedicate a full exposition of the many issues raised by this literature here, I discuss three main issues raised in earlier work.

First, it is difficult to define the boundaries of distinct thematic roles, and there is little consensus as to what the appropriate boundaries are. For example, Dowty (Reference Dowty1991: 553–555) discusses the issue of what he calls ‘role fragmentation’. He cites various authors who have subdivided the space of the Agent role into several (different) numbers of more finely defined sub-Agent roles, such as ‘Actor’, ‘Initiator’, ‘Volition’, etc. For example, Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff1983) proposes two roles, Cruse (Reference Cruse1973) splits Agent into four main roles, and Lakoff (Reference Lakoff1977) offers around fourteen roles. The question that Dowty poses is then: What is the nature of ‘Agent’ in light of finer distinctions? A parallel issue comes from data such as that in (20), which show that certain verbs, like ‘come’, appear with a Path role as well as different subcomponents of Path such as Source, Goal, and Route.

Data such as those in (20) further suggest that there is an open question as to what granularity of meaning should be associated with thematic roles; in other words, if it is assumed that Path is a primitive thematic role, then notions like Source, Route, and Goal should in principle not be related. Similarly, Croft (Reference Croft1991: 157–158) makes the point that while the role of Goal is often thought to subsume Allative, Recipient, and Beneficiary roles, these are generally also treated as separate roles in their own right.

Second, there is no one-to-one correspondence between thematic roles and grammatical functions, though such a correspondence has been generally assumed or explicitly argued to be a core component of grammar, such as via the Theta Criterion (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1981: 35) or Function-Argument Biuniqueness (Bresnan Reference Bresnan, Hoekstra, van der Hulst and Moortgat1980: 112). Various empirical issues arise with the assumption that each argument only has one role (see, e.g. Gruber Reference Gruber1976, Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1972, Reference Jackendoff1976, Reference Jackendoff1983, Dowty Reference Dowty1991). For example, some verbs, such as ‘hand’ and ‘buy’, have subjects that simultaneously have both Agent and Source/Goal roles.

In both sentences in (21), the subject is both the Agent and Source (21a) or Goal (21b) of the transfer of the Theme. These data thus show that multiple thematic roles can in fact appear with a single argument, contra the expectations of certain formulations of constraints like the Theta Criterion. Although there are ways to modify such proposals (e.g. Higginbotham Reference Higginbotham1989, Hornstein Reference Hornstein1999), the fact that there is not a one-to-one mapping puts into question the broader utility of thematic roles.

Ultimately, the biggest issue is that thematic roles by themselves provide no real insight into the broader generalizations that derive argument realization (in Levin & Rappaport Hovav’s Reference Levin and Hovav2005 terms, thematic roles lack ‘explanatory effectiveness’). Rappaport & Levin (Reference Rappaport, Levin and Wilkins1988) use the case study of English locative alternation verbs (e.g. ‘spray’, ‘load’) to show that thematic role lists abstract away from the verb in a way that fails to capture the appropriate semantic generalizations of the alternation, and this leads them to the conclusion that thematic roles are derivative notions that lack any explanatory value in themselves. Ultimately, the cited criticisms above (in addition to the lack of any clearly definable independent notion in the grammar), suggest that thematic roles are only useful insomuch as they are a convenient shorthand in discussing the correspondences between the semantic nature of arguments and argument positions in the syntax.

Due to these and other considerations, most approaches to the lexical semantics of argument realization have largely abandoned the centrality of thematic roles in driving the mapping between the syntax and the semantics; instead, argument realization is based on entailments of the verb as coded by a verbal root and template (Lakoff Reference Lakoff1965, Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1990, Reference Jackendoff1996, Dowty Reference Dowty1979, Rappaport & Levin Reference Rappaport, Levin and Wilkins1988, Hale & Keyser Reference Hale, Keyser, Hale and Keyser1993, Reference Hale, Keyser, Mendikoetxea and Uribe-Etxebarria1997, Levin & Rappaport Hovav Reference Levin and Hovav1995, Wunderlich Reference Wunderlich1997, Rappaport Hovav & Levin Reference Rappaport Hovav, Levin, Butt and Geuder1998, Harley Reference Harley, Pica and Rooryck2003, Reference Harley, Hinzen, Machery and Werning2012, Koenig & Davis Reference Koenig and Davis2006, Ramchand Reference Ramchand2008, inter alia) and/or based on specific entailments associated with the arguments (Ladusaw & Dowty Reference Ladusaw, Dowty and Wilkins1988, Dowty Reference Dowty, Chierchia, Partee and Turner1989, Reference Dowty1991, Primus Reference Primus1999, Beavers Reference Beavers2010, Grimm Reference Grimm2010, Reference Grimm2011, Jerro Reference Jerro2016b inter alia). While the use of roles as descriptive labels or as clusters of entailments (e.g. Dowty’s Reference Dowty, Chierchia, Partee and Turner1989 L-thematic roles) persists, what has been shown to be problematic is the basing of syntactic generalizations on particular role labels. I argue in the next subsection that this erroneous assumption has continued in the domain of determining the objecthood status of the applied object in Bantu applicative constructions.

4.2 Thematic roles and object (a)symmetries

Many previous approaches to analyzing object asymmetries have relied to some degree on the notion of thematic roles. Some have done so explicitly, such as Alsina & Mchombo (Reference Alsina, Mchombo and Mchombo1993) and related work, who tie the mapping of grammatical function directly to thematic roles via generalizations linked to a thematic hierarchy. Given their reliance on the notion of thematic roles for deriving the object asymmetries, such approaches are incompatible with the literature discussed in Section 4.1.Footnote [7]

In other work, thematic roles are employed to determine the syntactic structure of a given argument-licensing head, and in turn, the syntactic structure determines symmetry facts (cf. the discussion of high and low applicatives in Section 2.1). For example, Marantz (Reference Marantz and Mchombo1993: 123–125) puts forward the view that semantics is linked to the order of composition in the syntax; for example, he assumes that Beneficiaries (among other roles) are always external to the event while Instruments are within the event. Thus, his claim is that certain thematic roles should necessarily appear in specific syntactic positions, which is incompatible with a view that aims to eliminate thematic roles as an explanatory tool. Similarly, Pylkkänen (Reference Pylkkänen2008: 75–77) makes the assumption that locative applicatives are associated with low applicative syntax.Footnote [8] Given that many current accounts of object asymmetries use the high–low typology as a starting point, an approach that assumes that thematic role type determines whether an applicative is high or low is in conflict with the literature summarized in Section 4.1.

If we abandon the centrality of thematic roles (as I propose) in determining the argument realizational properties of a particular argument, how do we account for the fact that generalizations of applied objects in Bantu languages do in fact differ according to putative ‘thematic role’? For example, in Section 2.1, I discussed work by Baker (Reference Baker1988b) and Alsina & Mchombo (Reference Alsina, Mchombo and Mchombo1993), which showed that Chicheŵa has benefactive applicatives that are asymmetrical, but instrumental applicatives that are symmetrical; the question is, then, what determines this categorization if thematic roles cannot be called upon to derive argument structure. I propose that earlier categories can be deconstructed based on morphological and semantic properties of the applied object. I outline this proposal in the next subsection.

4.3 Applied object types in Bantu: a preliminary typology

I propose that what have been considered thematic roles of applied objects can be categorized via a reduction to two binary oppositions of whether the applied object is marked with a locative class marker and whether the applied object is animate. While previous work has made reference to other kinds of ‘thematic role’ types of applicatives, such as Reason and Goal applicatives, I focus here on what Schadeberg (Reference Schadeberg, Nurse and Philippson2003: 74) refers to as the ‘core’ roles of Bantu applied objects: Benefactive, Locative, and Instrumental (see also Ngonyani Reference Ngonyani1998). I leave other applied object types to future research. Note that the categorization of applied object types can only be coming from the applied objects themselves since most Bantu languages have a system in which all applied objects are licensed by the same form (a synchronic variant of ![]() ; see Meeussen Reference Meeussen1967, Schadeberg Reference Schadeberg, Nurse and Philippson2003, Good Reference Good2005, Pacchiarotti Reference Pacchiarotti2017, inter alia for discussion of the historical reconstruction of Proto-Bantu verbal extensions).Footnote

[9]

I now turn to laying out how applied objects in Bantu can be categorized in a way that does not rely on thematic roles.

; see Meeussen Reference Meeussen1967, Schadeberg Reference Schadeberg, Nurse and Philippson2003, Good Reference Good2005, Pacchiarotti Reference Pacchiarotti2017, inter alia for discussion of the historical reconstruction of Proto-Bantu verbal extensions).Footnote

[9]

I now turn to laying out how applied objects in Bantu can be categorized in a way that does not rely on thematic roles.

First, Locative applied objects are marked with locative noun class prefixes in many Bantu languages. A large body of work on Bantu has discussed the morphosyntactic nature of locative phrases, which – unlike the European systems of marking location via case and/or prepositions (see, e.g. van Riemsdijk Reference van Riemsdijk, Pinkster and Genee1990, Rooryck Reference Rooryck, Thráinsson, Epstien and Peter1996, Koopman Reference Koopman and Koopman2000, Svenonius Reference Svenonius, Reuland, Bhattacharya and Spathas2007, van Riemsdijk & Huijbregts Reference van Riemsdijk, Huijbregts, Karimi, Samiian and Wilkins2008) – appear with a locative prefix and are arguments in some languages and prepositional adjuncts in others (Welmers Reference Welmers1973, Bresnan & Kanerva Reference Bresnan and Kanerva1989, Bresnan Reference Bresnan1994, Bresnan & Mchombo Reference Bresnan and Mchombo1995, Rugemalira Reference Rugemalira2004, Riedel & Marten Reference Riedel and Marten2012, Guérois Reference Guérois2016, Zeller & Ngoboka Reference Zeller and Ngoboka2018). Unsurprisingly, for languages in which locative phrases behave more like prepositional adjuncts, they do not pattern with the verbal object and are generally restricted – see, e.g. Marten Reference Marten, Breitbarth, Lucas, Watts and Willis2010 on preposition-like locatives in Siswati (Bantu; Eswatini, South Africa).

In other languages, and what is the focus of the present discussion, the locative phrase behaves like an argument of the verb. For example, in Kinyarwanda, considerable evidence has shown that locative phrases (marked by locative class prefixes ku ‘class 17’, mu ‘class 18’, and i ‘class 23’) are arguments of the verb (Ngoboka Reference Ngoboka2016, Jerro Reference Jerro2016b, Reference Jerro2020a, Zeller & Ngoboka Reference Zeller and Ngoboka2018). One piece of evidence is that the number of locatives permitted within a single clause is restricted. If locatives are adjuncts, it should be possible to have multiple locative phrases; the data in (22), however, show that this is not the case.

In (22a), the verb kw-ambuka ‘to cross’ has a single locative object. If locatives are indeed adjuncts, one would expect that another locative could be added, but (22b) shows that this is not possible. This restriction is not semantic or pragmatic; an additional locative is in fact possible if licensed by the locative applicative, as in (22c). What is crucially not permitted is the stacking of multiple locative phrases, which is what should be possible if locatives are indeed adjuncts in this language. Other forms of evidence for locatives as arguments in Kinyarwanda are that they can be replaced by object markers, they can be the subject of a passive, and they can be replaced by verbal locative clitics; I do not discuss these facts in detail here, but refer the reader to Ngoboka (Reference Ngoboka2016), Jerro (Reference Jerro2016b, Reference Jerro2020a), and Zeller & Ngoboka (Reference Zeller and Ngoboka2018) for further discussion.

I propose that the presence of the locative prefix (such as mu in (22)) before the noun in locative phrases formally marks the NP in a way that makes these applied objects distinct from other NPs in the applied object position. On this view, the categorization of Locative applied objects arises via the formal presence of the locative prefix, and without the locative class prefix on the applied object, the phrase cannot be categorized as the locative applied object.

The second distinction that is pertinent to the categorization of applied objects in Bantu is that unmarked (i.e. non-locative) applied objects are distinguished between being animate and inanimate, which in Bantu is both a semantic and a morphological distinction. Specifically, in most Bantu languages, humans are overwhelmingly marked by classes 1 and 2 prefixes, which are generally a synchronic variant of Proto-Bantu ![]() and *bá–, respectively (Meeussen Reference Meeussen1967: 97). Animacy is an oft-cited factor in argument prominence with respect to applied objects in specific languages, especially with respect to determining word order (Hawkinson & Hyman Reference Hawkinson and Hyman1974, Morolong & Hyman Reference Morolong and Hyman1972, Hyman & Duranti Reference Hyman, Duranti, Hopper and Thompson1982, Aranovich Reference Aranovich, Butt and King2009). In Sesotho (Bantu; Lesotho, South Africa), for example, if there is a difference in animacy (e.g. one human and one non-human) between the two post-verbal dependents, the human noun must immediately follow the verb, regardless of the grammatical function of the argument (Morolong & Hyman Reference Morolong and Hyman1972). On the other hand, in Shona (Bantu; Zimbabwe), when the applied and verbal objects are both human, the Beneficiary applied object must precede the verbal object, as in (23).

and *bá–, respectively (Meeussen Reference Meeussen1967: 97). Animacy is an oft-cited factor in argument prominence with respect to applied objects in specific languages, especially with respect to determining word order (Hawkinson & Hyman Reference Hawkinson and Hyman1974, Morolong & Hyman Reference Morolong and Hyman1972, Hyman & Duranti Reference Hyman, Duranti, Hopper and Thompson1982, Aranovich Reference Aranovich, Butt and King2009). In Sesotho (Bantu; Lesotho, South Africa), for example, if there is a difference in animacy (e.g. one human and one non-human) between the two post-verbal dependents, the human noun must immediately follow the verb, regardless of the grammatical function of the argument (Morolong & Hyman Reference Morolong and Hyman1972). On the other hand, in Shona (Bantu; Zimbabwe), when the applied and verbal objects are both human, the Beneficiary applied object must precede the verbal object, as in (23).

In short, the animacy of the verbal and applied objects has been shown to affect the syntactic prominence, discourse prominence, and/or word order facts of the post-verbal dependents.

What I argue is that beyond the cases where animacy has been shown to determine the word order between applied and verbal objects, animacy additionally plays a role in the categorization of applied object types. As mentioned above, a key difference between locative phrases on the one hand and ‘Beneficiary’ and ‘Instrumental’ objects on the other is the fact that the latter two types are not formally marked to indicate their semantic contribution in the way that locative phrases are unambiguously marked as indicating a location.Footnote [10] The two non-locative thematic types of applicative differ in the animacy associated with the noun; prototypically, Beneficiaries are animate and Instruments are inanimate. I propose that these properties categorize the applied object as a particular applicative type (and, crucially, not a notion of thematic role).

Thus, a three-way typology emerges among applied object types: marked nouns (‘Locative’), unmarked animate nouns (‘Beneficiary’), and unmarked inanimate nouns (‘Instrument’).

The larger point made in this section is that not only is there no inherent tie between the syntax and thematic role as argued in Section 3, but further, the linking of a grammatical notion of ‘thematic role’ is problematic in the first place. Instead, the different types of applied objects in Bantu are categorized among themselves via a specific set of morpho-semantic properties, and it is via this categorization that a given applied object is linked to a particular syntax. In turn, whether an applied object type in a language is high or low captures its symmetry properties, with the working hypothesis being that the high applicative will be symmetrical and the low applicative will be asymmetrical. In the next section, I outline three predictions that follow from this analysis. For the rest of this discussion, I will continue to use the traditional labels (Beneficiary, Instrument, and Locative) for these three applied object types, but I do not assume any relationship to their use as thematic roles.

5 Predictions of the analysis

In the previous sections, I have made two interrelated claims regarding the relationship between the syntax and semantics of argument realization within the domain of Bantu applicative morphology. First, I argued that formally there is no necessary correlation between the semantics of a particular applied object and its syntactic structure as defined by its objecthood properties. Second, I argued that thematic roles should not be relied upon to derive syntactic facts about the mapping of arguments and that applied object types are in fact derived from morpho-semantic properties of the applied object. Taken together, these two claims make various predictions about the syntax and semantics of applied objects. I discuss three predictions in this section: (i) semantic and syntactic diagnostics for high and low applicative status need not align, (ii) asymmetrical c-command is expected for languages that are otherwise symmetrical, and (iii) there is no universal correlation between ‘thematic role’ and object symmetry.

5.1 A mismatch between syntax and semantics: evidence from Kinyarwanda

The proposed analysis (particularly, the discussion in Section 3) claims that the syntax and the semantics of the high and low applicatives should not be correlated; any semantics can in principle be associated with either a high or a low structure. The prediction, then, is that there should be cases where the syntactic and semantic properties attributed to Pylkkänen’s original high and low applicative heads do not match. In this section, I present data from the Kinyarwanda benefactive applicative, which show that this expectation is borne out (see Ackerman et al. Reference Ackerman, Malouf and Moore2017: 28–30 for a comparable point about syntax/semantics mismatches in the Kordofanian language Moro).

Given the traditional assumptions of high and low applicatives, high applicatives can appear with unergative and stative verbs, while low applicatives cannot (cf. Pylkkänen Reference Pylkkänen2008: 18ff). In Kinyarwanda, the benefactive can appear with both unergative and stative verbs, as in (24) and (25). This suggests that the applicative is high.

While the ability for the applicative morpheme to appear with unergatives and statives in (24) and (25) suggests that the Appl head is high in Kinyarwanda benefactive applicatives, the transfer-of-possession reading in (29) is a classic property of low applicatives.Footnote [11]

Thus the benefactive applicative in Kinyarwanda has properties of both a high and a low applicative in the original typology – a problem for the original proposal.

One solution would be to claim that the transfer-of-possession reading and the true Beneficiary readings are licensed by homophonous applicative heads, which are low (when there is transfer of possession) and high (when there is not). This approach would make the prediction, however, that the Recipient reading (by virtue of being associated with a low applicative) should be asymmetrical (on the assumption that high applicatives are symmetrical; see Section 2.1). However, this prediction is not borne out: in (27a), both objects are acceptable as the subject of the passive, and in (28), both objects may be marked as an object marker on the verb – crucially, with the transfer-of-possession reading.

The data in (27a) and (28) show that assuming a transfer-of-possession reading is restricted to a low applicative head is incongruous with the proposal that low applicatives are asymmetrical. Thus, the best alternative is that the benefactive applicative is high in Kinyarwanda, regardless of a transfer-of-possession reading.

As an aside, recent work has rethought how transfer of possession is introduced into the argument structure (see especially, Beavers & Koontz-Garboden Reference Beavers and Koontz-Garboden2017, Reference Beavers and Koontz-Garboden2020), as part of a larger point that roots can in fact contribute template-like entailments such as cause and become (Beavers & Koontz-Garboden Reference Beavers and Koontz-Garboden2018, Jerro Reference Jerro2018, Beavers, Everdell, Jerro, Kauhanen, Koontz-Garboden, LeBovidge & Nichols Reference Beavers, Everdell, Jerro, Kauhanen, Koontz-Garboden, LeBovidge and Nichols2020).Footnote [12] Building on work by Rappaport Hovav & Levin (Reference Rappaport Hovav and Levin2008) and Beavers (Reference Beavers2011) on the semantics of ditransitive verbs in English, Beavers & Koontz-Garboden (Reference Beavers and Koontz-Garboden2017) show that – unlike previous approaches wherein caused possession can only be licensed by the template (Arad Reference Arad2005, Embick Reference Embick2009, Dunbar & Wellwood Reference Dunbar and Wellwood2016) – verbal roots can in fact contribute entailments such as cause; in the context of the present discussion, this means that what Pylkkänen (Reference Pylkkänen2008) calls transfer of possession does not come from an applicative head (which is part of the verbal template), but from those verbal roots that independently entail caused possession.

For Kinyarwanda, there is evidence that this is correct; it is only certain verbs that allow the Recipient reading of the Beneficiary – specifically those roots that independently entail a third participant which is a Goal or Recipient, such as k-ohereza ‘to send’ and ku-jugunya ‘to throw’. For example, in (26) – repeated from (29) – the subject of the verb k-ohereza ‘to send’ is sending money to the speaker’s parents, who are the prospective recipients of the money.

The verb ku-mena ‘to break’ in (30), on the other hand, cannot have a recipient reading; the applied object can only be interpreted as a deputative benefactive reading (i.e. on behalf of someone else).

The contrast in the ability to have a Recipient interpretation of the applied object between k-ohereza ‘to send’ and ku-mena ‘to break’ suggests that roots vary in whether they permit the transfer-of-possession reading. From this, the contribution of the applicative head is more general than previously assumed: it contributes a third participant, which subsumes Beneficiary and Recipient, and the specific interpretation comes from the verbal root. While I leave a detailed analysis of these facts for future work, this further suggests that transfer of possession cannot reliably diagnose the syntactic structure of templates across verbs since the entailments specific to transfer of possession are in fact contributed on a root-by-root basis. This supports the larger point that the applicative head being high or low does not correlate with the semantics of the applied object.

5.2 Asymmetric c-command and objecthood: evidence from Kinyarwanda

While the focus so far has been on the dissimilarities between high and low applicatives in terms of their syntactic structure, there is one fact in which both high and low applicatives are the same: they both involve the applied object asymmetrically c-commanding the verbal object. This means that regardless of the other symmetry facts that are present in a particular language, there should always be asymmetrical c-command between the applied and the verbal object. This is most clearly tested in a language that has predominantly symmetrical patterns for a particular applicative. Kinyarwanda is such a language; the data in (32)–(34) indicate that the benefactive applicative is symmetrical in this language (thus corresponding to a high applicative, on the view put forward in Section 2.1). In (32), either the applied object or the verbal object can be the subject of a passive; cp. the base sentence in (31). Similarly, (33) shows that either can be extracted as the head of a relative clause. The examples in (34) further show that either can be an object marker on the main verb.

These diagnostics indicate a situation in which there is symmetry between the applied and verbal objects in Kinyarwanda benefactive applicatives.

The benefactive applicative in Kinyarwanda is a high applicative head, which captures the symmetry in (32)–(34), but by nature, the applied object is merged higher than the verbal object, which makes the prediction that c-command facts should be asymmetrical despite there being symmetry otherwise. Using the binding of pronouns by the quantifier buri ‘every’ (a classic c-command diagnostic; Barss & Lasnik Reference Barss and Lasnik1986), we see that this asymmetrical scenario is borne out. In (35a), the applied object can bind into the verbal object, but the opposite is not possible, as in (35b)–(35d).Footnote [13]

In (36a), a similar situation is found with what Barss & Lasnik (Reference Barss and Lasnik1986) call ‘Superiority’ (who adopt the term from Chomsky Reference Chomsky, Anderson and Kiparsky1973); here only the applied object can be fronted in a situation in which both objects are question words, as in (36a). Thus, we again see a c-command asymmetry between the two objects.

Given standard assumptions about c-command, the pronoun binding and superiority data indicate that the applied object asymmetrically c-commands the theme, as expected from the structures in (5). Other diagnostics in Kinyarwanda – such as passivization, object marking, and word order – are symmetrical.Footnote [14] This follows from the present account since high and low applicatives have the same c-command relationship between the applied and verbal arguments, and therefore, the c-command relationship is predicted to be asymmetrical regardless of their symmetry properties with objecthood diagnostics.Footnote [15]

5.3 Cross-linguistic variation

Given the claim in Section 3 that there is no universal link between the applied object type and high or low applicative heads, it is expected that there is no universal link across languages that a particular applied object type will necessarily be symmetrical or asymmetrical.

For each applied object type, there are predicted to be two languages: one which links that applied object type to a high structure and one which links it to a low structure. As was shown in Section 3, benefactive applicatives (categorized by being unmarked, animate applied objects) can in principle be high or low, as in (37), with the semantics in (38a) for high applicatives and (38b) for low applicatives.Footnote [16]

The proposal that the high applicative derives object symmetry and the low applicative derives asymmetry predicts that there should be languages with benefactive applicatives that are symmetrical and languages with benefactives that are asymmetrical. Recall that the beneficiary semantics are identical for both, with the denotations in (38a) and (38b) differing only in how the meanings are composed. This prediction is borne out; in fact, this observation goes back to the seminal cross-linguistic work of Bresnan & Moshi (Reference Bresnan and Moshi1990), who show that languages vary in their symmetry properties, showing variation in benefactive applicatives in a host of languages. Consider the data in (39) and (40) from Chicheŵa and Lubukusu (Bantu; Kenya), respectively. While the benefactive in Chicheŵa is asymmetrical with passivization, it is symmetrical with Lubukusu.

These data (which were elicited to be identical in both languages to rule out any possible confounding factors) show the predicted variation; there exists a benefactive applicative with symmetry in one language but asymmetry in the other. Specifically, while Chicheŵa has an asymmetrical benefactive in (39), Lubukusu has a symmetrical benefactive in (40). Chicheŵa, then, has the benefactive applicative of the type in (37a), while Lubukusu has the benefactive applicative of the type in (37b) – thus both possible types are attested. This variation is found more broadly in other Bantu languages: like Lubukusu, Kinyarwanda (Gary & Keenan Reference Gary, Keenan, Cole and Sadock1977, Kimenyi Reference Kimenyi1980), Kihaya (Tanzania; Byarushengo, Duranti & Hyman Reference Byarushengo, Duranti and Hyman1977), Kimeru (Kenya; Hodges Reference Hodges1977), and Luyia (Kenya; Gary Reference Gary1977) have been described as symmetrical in the benefactive (as cited in Bresnan & Moshi Reference Bresnan and Moshi1990: 47), while other languages like Chimwi:ni (Kisseberth & Abasheikh Reference Kisseberth, Abasheikh, Cole and Sadock1977) and Hibena (Tanzania; Hodges & Stucky Reference Hodges and Stucky1979) have been described as patterning with Chicheŵa in being asymmetrical with benefactives.

While Bresnan & Moshi (Reference Bresnan and Moshi1990) focus on benefactive applicatives, the variation in whether a particular type of applied object is (a)symmetrical shows similar variation with other types of applied objects. As with the benefactive applicative, the instrumental applicative is also available in either high or low structures, as in (41), with the corresponding semantic denotations in (42).

Consider the following instrumental applicative data, which again compare Chicheŵa and Lubukusu, but here, the pattern is the opposite: Lubukusu has the asymmetrical scenario with the instrumental applicative in (44), while the cognate sentence in Chicheŵa in (43) is symmetrical (see also Baker Reference Baker1988b, Alsina & Mchombo Reference Alsina and Mchombo1990, and Alsina & Mchombo Reference Alsina, Mchombo and Mchombo1993 for a description of the instrumental applicative being symmetrical).Footnote [17]

These data show that the opposite pattern from benefactive applicatives is observed for instrumental applicatives in Chicheŵa and Lubukusu: while the instrumental applicative is symmetrical in Chicheŵa, it is asymmetrical in Lubukusu.

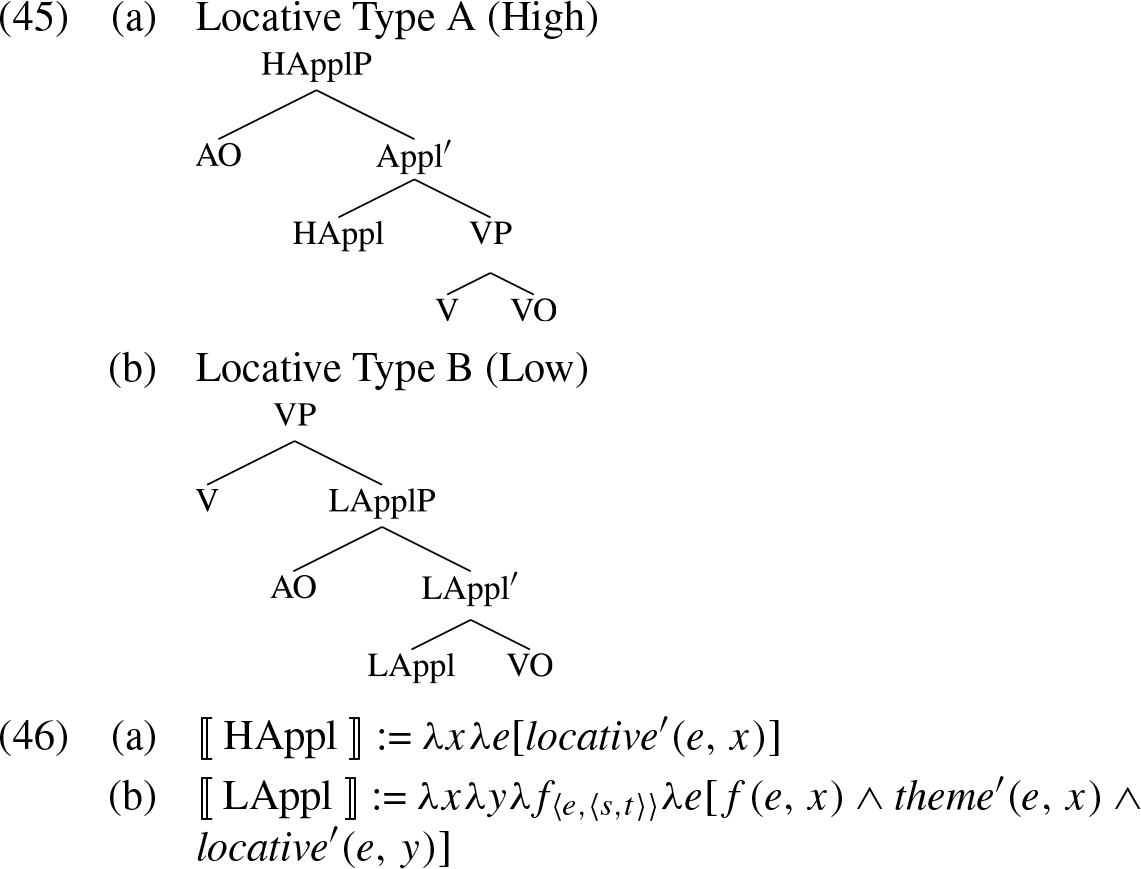

The third applied object type I discuss is locative applicatives. As mentioned in Section 4.3, there is considerable variation across Bantu as to whether locatives are class-marked nominals or prepositions, but for many languages, locatives are licensed by applicatives and can thus be assumed to be arguments, at least in those languages. Given this, locative applicatives are predicted to vary in comparable ways to other applied object types. The structures in (45) indicate the two possible kinds of locative applicative that in principle exist.

The predicted variation with locatives is borne out with the object marking data in (47)–(49), where Kinyarwanda shows an example of a symmetrical locative, while Lubukusu and Chicheŵa both show examples of asymmetrical locatives.Footnote [18] Note that for Kinyarwanda, agreement with locative classes is neutralized, and all locative classes (16–18 and 23) trigger class 16 agreement – a feature of various ‘Great Lakes’ Bantu languages (Batibo Reference Batibo1985, Maho Reference Maho1999).

As with benefactive and instrumental applicatives, there exists a language for which the locative applicative is symmetrical and for which it is asymmetrical.

The fact that there exists a language that is symmetrical and asymmetrical for each of the three core applicative types is evidence that there is no universal link between the applied object type and a particular symmetry pattern. This was shown explicitly here by giving evidence from the three core types of applicatives in Bantu (benefactive, locative, and instrumental), which are categorized by their morpho-semantic type, as discussed in Section 4.3. Unlike other approaches, this analysis assumes no inherent link between the applied object type and its syntactic position, and thus the two are expected to (and, indeed, do) vary among languages. While other accounts have observed many of these facts independently, they have attempted to link the symmetry properties to universal generalizations about, for example, thematic role, which fails to capture the cross-linguistic variation described here.

6 Conclusion and directions for future work

In this paper, I have argued against a strict correlation between semantics and syntactic structure with respect to applicative morphology. Ultimately, I have proposed that the two must be allowed to operate independently, and I have shown that formally there is no restriction in doing so. Specifically, I have made two broad claims. First, I have argued that the relationship between the syntax of a particular argument and its semantic meaning is not necessarily correlated in the case of applied objects. Second, I have shown that there has been a reliance on the semantic nature of the applied object (via its categorization by thematic role) to derive object asymmetries in Bantu applied objects, and – citing work on the lexical semantics of argument realization – I have argued that generalizations built on thematic role (directly or indirectly) cannot capture the observed variation in Bantu applied objects. I propose instead that what have been treated as thematic role labels are better categorized by specific morphological and semantic aspects of the applied object. This approach makes various predictions about the syntactic and semantic properties of the benefactive applicative, the c-command facts in otherwise symmetrical languages, and it also fits with the variation found with the object symmetry facts among various Bantu languages. By nature, many of the morphosyntactic facts presented are unique to the Bantu languages, such as the nature of locative prefixes and the marking of noun classes more generally. I expect, however, that studies of (a)symmetries in other language families would show comparable kinds of syntactic and semantic variation. I leave this interesting question to future research.

While I have laid out a general framework for discussing the semantic and syntactic nature of applied objects in Bantu languages, there are many other language-specific facts that intersect with the framework proposed here. A mélange of syntactic, semantic, and discursive components of the grammar should be investigated in understanding the object symmetry facts in a given language, and this kind of multivariate approach has been widely assumed to be the case for other languages; for example, in English, it has been argued that argument realization patterns of the dative alternation are affected by various interrelated factors such as verb class (Rappaport Hovav & Levin Reference Rappaport Hovav and Levin2008, Beavers Reference Beavers2011), information structure (Goldberg Reference Goldberg, Bourns and Myers2014), or a mix of various factors such as noun animacy, NP weight, pragmatics, etc. (Bresnan, Cueni, Nikitina & Baayen Reference Bresnan, Cueni, Nikitina, Baayen, Bouma, Kraemer and Zwarts2007). For Bantu languages, recent work has started to look at other influencing factors on object symmetry, such as the role of pronominal arguments (Baker, Safir & Sikuku Reference Baker, Safir, Sikuku, Arnett and Bennett2012) and how dislocation constructions affect symmetry (Zeller Reference Zeller2015). Jerro (Reference Jerro2019) proposes that verb class affects the behavior of objecthood facts in Lubukusu, and other work has shown that information structure is a core component to argument realization across the family (see, e.g. van der Wal Reference van der Wal2016 and van der Wal & Namyalo Reference van der Wal, Namyalo, Payne, Pacchiarotti and Bosire2016). Finally, variation in inherent Case assignment may also play a role in the behavior of arguments within Bantu (Diercks Reference Diercks2012, Halpert Reference Halpert2012). How these various grammatical facts come together around applied objects in Bantu is an area ripe for future work, and I believe these can be framed around the ideas presented here.