Introduction

Background

The United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) define an active shooter incident (ASI) as “an individual actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people in a confined and populated area.”1 Active shooter incidents (ASIs) typically occur in soft targets, which the Oxford Dictionary defines as “a person or thing that is relatively unprotected or vulnerable, especially to military or terrorist attack.”2 Between 1966 and 2010 there were 154 active shooter incidents in hospitals in the United States, which represents 2.3% of all ASIs.Reference Coss, Rennie, Kelen, Catlett, Kubit and Hsieh3 Shootings were more common in larger hospitals and greater than half of these incidents occurred within the hospital itself, with 29% taking place in the emergency department (ED) and 19% in patient rooms. Of the shootings that took place in an ED, 23% of them involved the perpetrator using a security officer's gun.4 Although ASIs are distinct from workplace violence, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) report that approximately 75% of all assaults in the workplace occur in healthcare.Reference Foley and Phillips5

A June 2018 FBI report examining the psychological profiles of 63 active shooters found that the shooters “did not appear to be uniform in any way such that they could be readily identified prior to attacking based on demographics alone.”Reference Silver, Simons and Craun6 Aside from male gender, there was no single reliable profile of an active shooter, and the authors were surprised that there was an “absence of a pronounced violent criminal history in an overwhelming majority of the adult active shooters.”7 Despite the common narrative about these shooters, only 25% had a diagnosed mental illness, employment status turned out to be irrelevant, and nearly half were married.8

Current guidelines from federal law enforcement agencies recommend Run-Hide-Fight as the stepwise response during an ASI.Reference Maryniak9 In the event of an ASI, one should immediately try to evacuate the premises, i.e. “Run.” If you cannot run away, the next recommendation is to “Hide.” This may take the form of barricading oneself in a location in the most secure way possible. In the event one cannot hide, then you should prepare to defend yourself by fighting the attacker if approached, i.e. “Fight.”

Utilizing current bioethical principles, healthcare professionals (HCP) are responsible for providing care that is just, beneficent, and nonmaleficent, while respecting the right to self-determination (autonomy) of their patients.Reference Beauchamp and Childress10 Notwithstanding these principles, it still remains unclear what obligations, if any, HCPs have to care for patients under their care during an ASI. Throughout the history of medicine, HCPs have taken on health risks to themselves, oftentimes accepting it as part of their job. Although, unlike other ethical conundrums HCPs have faced, very little has been written about their duties during an event as volatile and violent as an ASI. Healthcare institutions and medical professionals have a duty to treat (and many argue, protect) all patients under their care, especially during times of need and/or in emergent situations.Reference Jacobs and Burns11 There are even legal and moral obligations for hospital emergency rooms rooted in the 1986 Emergency Medical Treatment & Labor Act (EMTALA), which have become entrenched in the moral fiber and ethics of the profession of Emergency Medicine through its various societies.12 Since EMTALA was written, though, the societal issue of ASIs has grown, with more events occurring between 2007-2013 (average 16.4 events/year) as compared to 2000-2006 (average of 6.4 events/year).13

This review aims to accomplish three objectives: To conduct a review of the literature, examining the responsibilities of healthcare professionals during an ASI at their hospitals; To determine the ethical obligations of healthcare professionals during an ASI at their hospitals; To make possible recommendations in order to prepare and respond to an ASI. Furthermore, we will argue that the ultimate moral and legal responsibility towards patients during an ASI should fall squarely on the healthcare institution and not the individual HCP.

This review aims to accomplish three objectives: To conduct a review of the literature, examining the responsibilities of healthcare professionals during an ASI at their hospitals; To determine the ethical obligations of healthcare professionals during an ASI at their hospitals; To make possible recommendations in order to prepare and respond to an ASI.

Methods

The authors followed the Preferred Reporting for Systematic Reviews Protocols (PRISMA) guidelines; however, found a dearth of literature covering this topic. Based on the results of the search, we converted the review to a narrative review.

Eligibility Criteria

Articles that addressed active shooter incidents in hospitals in the United States were screened for inclusion. Individual, departmental, or system-wide responses to the ethical obligations of healthcare professions was the primary outcome being addressed. All articles were limited to English language.

Search Strategy

A combination of key biomedical databases and general information databases were searched and included PubMed/Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science Plus, Journals @ Ovid, and ProQuest Central. In addition, the New York Academy of Medicine Grey Literature database was reviewed for information not found in biomedical databases. We also scanned online resources for additional information beyond the database searches including editorials, news media, and commentaries listed. We reviewed several bibliographies and used the “find similar articles” feature in many of the databases. We hand-reviewed all references of the obtained manuscripts specific to our review. The final search was completed May 2019.

Data Screening and Extraction

Records were exported from EndNote to Covidence, an online software program for managing systematic reviews. Two of the authors (AG and AM) screened and extracted the data. The literature was mostly qualitative and narrative data spanning the last 25 years. The initial search yielded 389 hits, of which 86 were relevant to our topic, and 36 were specific to this review, after further pruning the articles obtained, eliminating duplicates, the final count was 33 articles. The PRISMA flow diagram representing the process appears below in Figure 1.

Figure 1 PRISMA flow diagram

Results

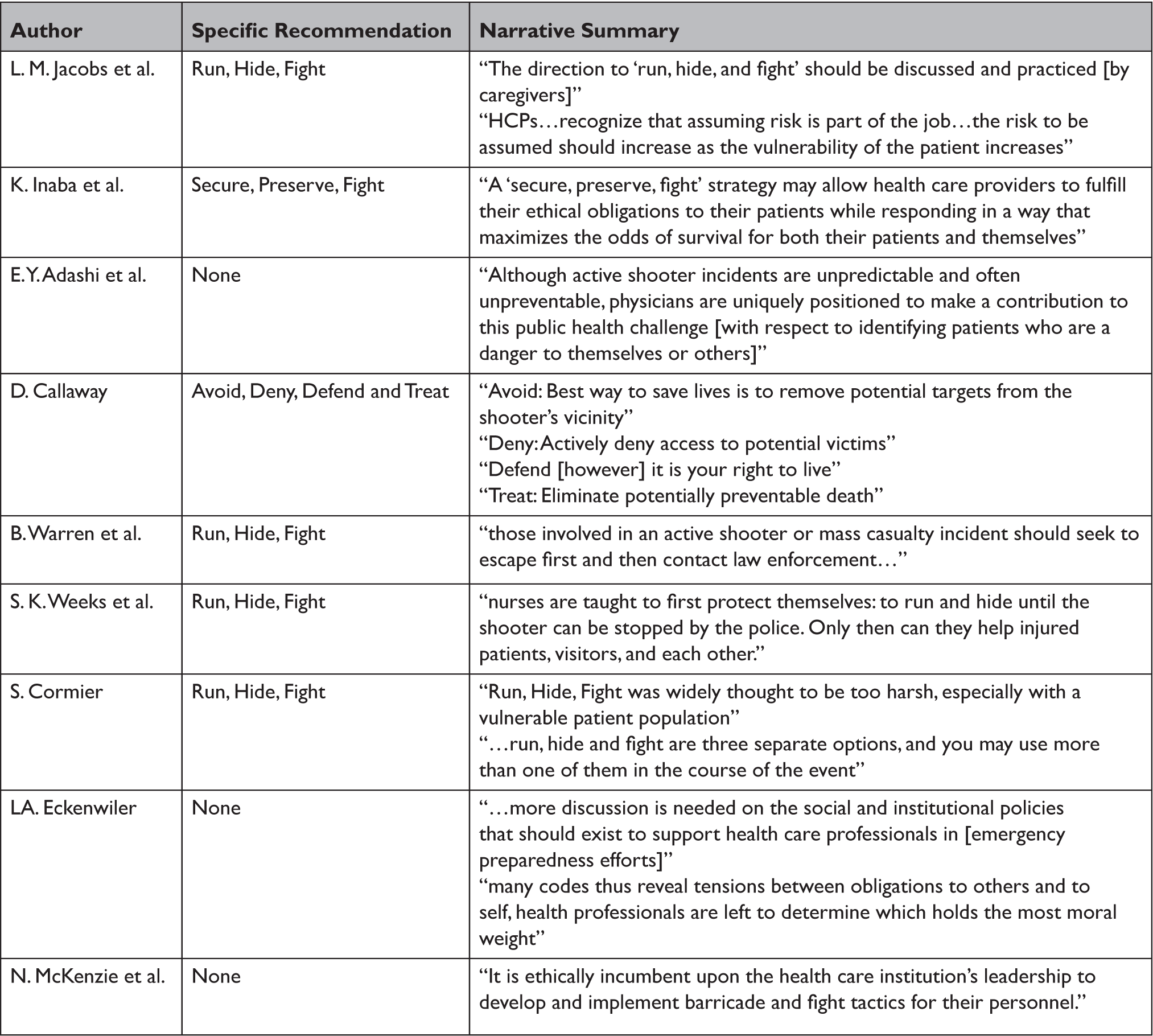

There is a paucity of data on the moral obligations of healthcare professionals and healthcare institutions during ASIs. We have summarized the findings in Table 2.

Table 1. Included Studies Addressing Active Shooter Incidents in Hospitals

Table 2. Specific Recommendations of Included Studies excluding Agency Recommendations

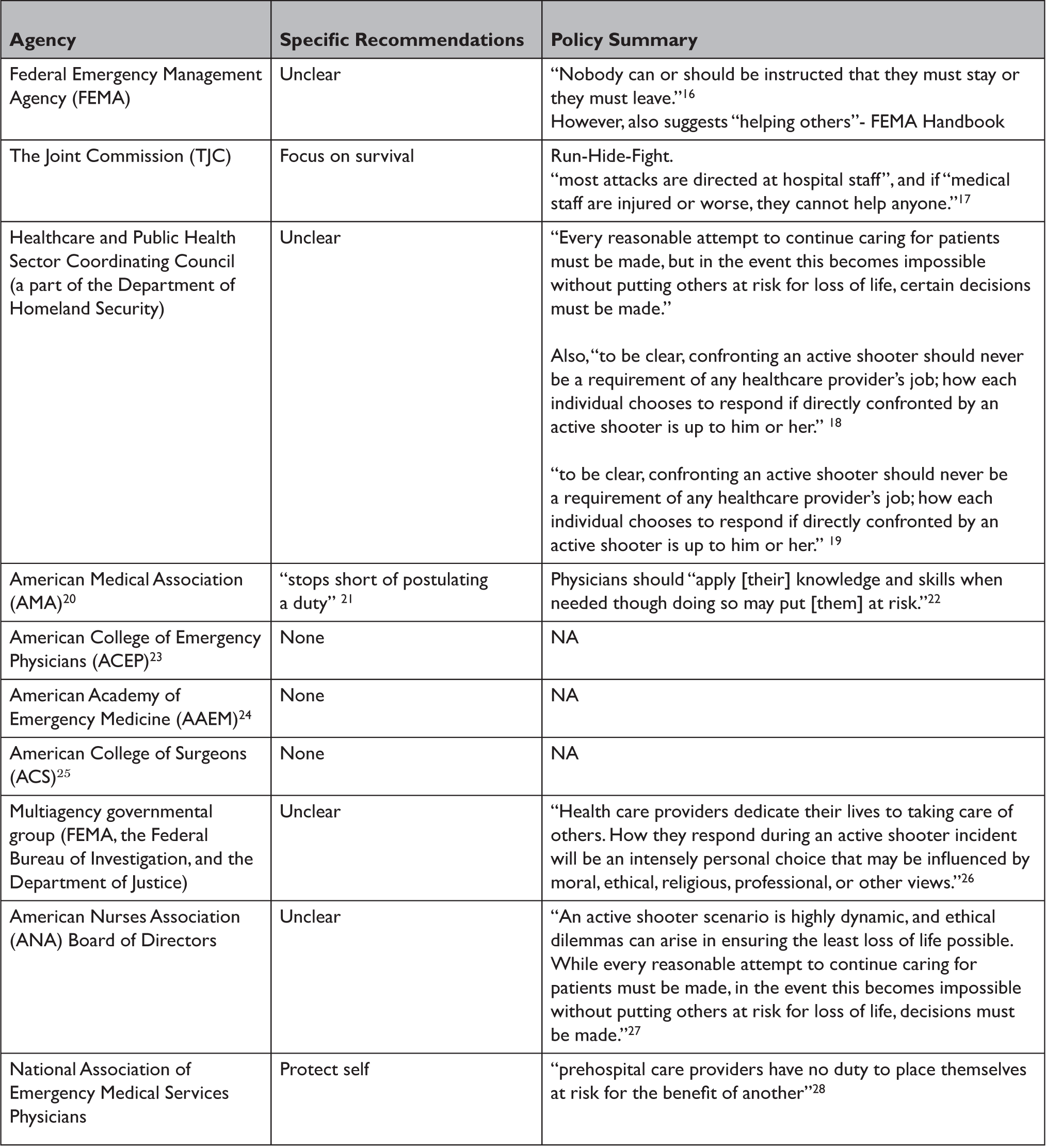

The guidance provided by governmental bodies and professional associations is summarized below in Table 3. Generally, there is an emphasis on the need for HCPs to focus on their own survival with limited emphasis on their responsibilities to protect patients from an active shooter. As further stated by Eckenwiler, “Ethics codes generally give less explicit directives but can make strong moral claims on health professionals… While many codes thus reveal tensions between obligations to others and to self, health professionals are left to determine which holds the most moral weight.”Reference Eckenwiler14

Table 3. Specific Agency Recommendations during an Active Shooter Incident

#-In the 1847 AMA Code of Medical Ethics, the AMA had previously taken a stance in its recommendations for physicians working during a crisis, stating “when pestilence prevails, it is [physicians'] duty to face the danger, and continue their labors for the alleviation of suffering, even at the jeopardy of their own lives.”Reference Baker29 This language has since been removed from the AMA's Code.

Limitations

This study was limited by several factors: first, there is very limited quantitative research on this topic, consequently we were left with a large number of editorials, commentaries, opinion reviews, and very few cross-sectional studies; which were mostly small sample studies. Several of the articles reviewed were from internet sources which poses a challenge to their scientific vigor.

Discussion

Lately, there has been greater discussion of whether HCPs confronted with an ASI at their place of work should first seek to protect patients and then themselves.Reference Inaba, Eastman, Jacobs and Mattox15 This moral dilemma translates to whether the duty to care for (and possibly, to protect) patients can be outweighed by the right to protect one's self from harm. Some authors have suggested that the healthcare professional's responsibility is to first save themselves in an ASI although they are ultimately still responsible for the welfare of their patients-“We are expected not only to survive, but to turn right around, respond, and treat casualties.”Reference Palmer30 Iserson et al. addressed the moral obligations of EPs during a disaster, stating the following:

For all of the above reasons — the great needs of patients, the special expertise of health care professionals, the professional duty of beneficence, the special societal support given to health care professionals, and the duty to accept a fair share of workplace risks — we are persuaded that there is a prima facie moral duty to work in medical disasters and at other times of great social need. By saying that this duty is “prima facie,” we acknowledge that it is a significant, but not an absolute, moral duty. We recognize, in other words, that this moral duty to work during a disaster may, in certain circumstances, be overridden by other professional and personal duties or rights.Reference Isserson31

The bioethics literature has yet to provide clear guidance on the obligations in ASIs. To name a few, Deontology, which is the study of a person's duty or moral obligation, fails to provide specific answers or guidance for this concern. Virtue ethics demands moral characteristics, which although viewed as noble and admirable to some are not universally accepted prerequisites for all practitioners of medicine. Consequentialism, which is defined as the doctrine that the morality of an action is to be judged solely by its consequences, immediately loses as a moral source for answers because of the inherent uncertainty of ASIs. The Principlism movement brought forth by Beauchamp and Childress with its four principles, is patient-centric in nature, but inadequate in guiding physicians' moral choices in an ASI.32 Our literature search yielded some case-based (casuistry) discussions on ASIs, but these also fail to provide specific guidance for the HCP in resolving the moral dilemma. Lastly, analysis of Codes and Oaths of various governmental agencies and professional organizations reveals mostly self-protective recommendations, although many generally acknowledge an obligation to patients. We believe the following conclusion from Iserson et al. is most instructive, “However noble it seems to appeal to values, religion, virtues, professionalism, and ethical theory, fear, the ‘apprehensive feeling toward anything regarded as a source of danger,’ often determines people's actions in crises that encompass significant risk, such as during epidemics.”33

Notwithstanding the above, most medical ethicists believe HCPs have a professional and moral duty to care for their patients. This is not only adopted in the AMA Code of Ethics, but in numerous subspecialty organizations as well.34 Pellegrino suggests that HCPs have taken an oath, which demonstrates the gravity of their calling, and further purports, that the nature of illness, the non-proprietary character of medical knowledge, and the oath of fidelity to the patients' interest, all generate strong moral obligations.Reference Pellegrino35 However, it seems unlikely that an oath is a sufficient and legally binding contract for physicians or that it even generates a strong moral obligation. The generally accepted legal definition of an oath or its non-religious equivalent, an affirmation, is a “declaration made according to law, before a competent tribunal or officer, to tell the truth.”36 However, there is no such tribunal or officer individually certifying physicians' oaths or affirmations in medical schools or residencies in the U.S. Additionally, the recitation of an oath has become more of a ceremonial rather than a substantive act in the career of medical practitioners. Hence, holding a physician to an oath is unlikely to persuade those unwilling or unable to put their lives in danger.

Inaba et al. stressed the conundrum faced by medical professionals who recognize a responsibility to patients and are also given directives to “Run” first: “matters are further complicated by the fact that healthcare professionals have a moral and ethical duty not to abandon their patients, which directly conflicts with the primary directive to run.”37 Inaba et al. also pointed out some of the logistical issues with an ASI in a healthcare facility. Unlike a school or other non-healthcare venue, hospitals are filled with infirm and debilitated patients who may not be able to heed the FBI's recommended “Run, Hide, Fight” mantra. Inaba et al. suggest that healthcare institutions follow “Secure, Preserve, Fight” instead: “for professionals providing essential medical care to patients who cannot run, hide, or fight owing to their medical condition or ongoing life-sustaining therapy, a different set of responses should be considered — secure the location immediately, preserve the life of the patient and oneself, and fight only if necessary.”38 This recommendation is instructive as there is no encouragement to escape when possible nor to necessarily put one's self in harm's way, but to either secure patient care areas to limit ingress or egress of a shooter or avoid such areas, and return when safe to render care to the infirm. Inaba et al.'s recommendation shares with others a soft-pedal of the responsibility to stay with patients who cannot “run”: they encourage that their recommended set of responsibilities should be “considered.” This recommendation matches a recent study on the response of healthcare students during an ASI: a “significant majority of interprofessional health care students…declared they would act to protect themselves and their patients during an active shooter event” and reject the provider-centric recommendation to “run” as a first option.Reference McKenzie39

In our view, the latitude of Inaba et al.'s recommendation is appropriate. Ethics may prepare one to make good judgments about what one ought to do, but such preparation will remain too abstract and high-level for decisions in the heat of a moment defined by extreme uncertainty and ignorance (and of course, fear). It is enough for the healthcare professional to know that they will be making a judgment that attempts to balance their responsibilities to care for their patients in the moment with their responsibility to survive so that they can continue to care for patients in the future. Instead of HCPs, the first focus of responsibilities regarding ASIs rests on the organizations within which these situations are likely to arise. In order to secure an area during an ASI, appropriate institutional resources need to be dedicated to such a project, i.e. barrier entry systems and system designs limiting access points.Reference Braun40 Providing clear guidance about responsibilities to individuals who will be in positions of limited information and significant (and changing) risks will be difficult at best. The focus on organizations is important because the safety and wellbeing of patients and staff falls principally on the organization itself. In respecting the rights of persons to a safe setting, there is a duty to provide a safe environment, which is why most recommendations in the literature for the management of ASIs have tended to focus primarily on increased security and other protective measures. As further elucidated by Eckenwiler:

It appears, at least at present, that requirements and entreaties for health professionals to face the grave dangers presented by bioterrorism or weapons of mass destruction fail to meet the ethical principle of proportionality, which holds that policies and practices are ethically justifiable when the risks of harm are minimized and reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits. To be sure, the expertise of health professionals would bring great benefit to public health in a disaster. Yet, without adequate resources, health professionals' capacities to protect their own bodily integrity in a crisis is severely impaired. This in turn poses serious risks for the health of the public.41

An ASI is not under the control of a physician, and although patients (and staff) have a right to safety, it is the institution, not the physician, who has a duty to provide for their safety.

Many authors have compared the ethics and obligations of HCPs in an ASI with other potentially life harming events to the HCP. Thirty years ago, substantive questions were raised about physician responsibilities to put themselves at risk in light of the HIV/AIDS crisis in the United States. Edmund Pellegrino's (1987) response to these questions emphasized and argued for the special obligations medical practitioners accept by becoming part of a medical profession. His arguments reflect the general view that HCPs, by becoming part of the profession, accept that they have responsibilities beyond what is required of the average person or citizen.42 In 2014, the spread of the Ebola virus brought these issues back to the surface once again, but in a situation with more substantial risks of harm and death. Specifically, healthcare workers treating patients sickened by Ebola were 21-32x more likely to contract the disease, and this was fatal 2/3 of the time per the WHO. These grave risks have explained why there was difficulty in recruiting physicians to help. The increased and mortal risk of Ebola demonstrated that the duty to care at the risk of personal harm was not interpreted by physicians as unmitigated. To explain this limit on what has been typically understood as a foundational responsibility of HCPs, Yakubu et al. call the obligation to care despite risks of harm to self a “professional” but not a “moral” obligation.Reference Yakubu43 Perhaps acknowledging that a professional obligation cannot in and of itself mandate a duty to treat given the risks of harm to the HCP. Whereas those HCPs who choose to help do so at the behest of their own personal moral code.

Historically (and again with the Ebola virus), infectious diseases provide the context of the question about HCPs responsibilities to help others in the face of threats to their personal well-being. And there are some valuable corollaries between an ASI and an infectious disease outbreak or epidemic. Both involve threats to well-being and, perhaps, life. From both situations, the practitioner could “run away” either figuratively or literally. And in both situations physicians and other medical practitioners are in a unique position to provide help and to protect the well-being of patients and others. However, the differences are more profound. Most notable are the differences between the unique positions of HCPs in cases of infectious disease and ASIs. In cases of infectious disease, the practitioner's unique position is due in large part to the specialized training they have received. Pellegrino highlights the significance of this training in establishing the responsibilities of physicians to help others even when it puts themselves at risk.44 In ASIs, however, only the details of their circumstance put them in a unique position, i.e. that they work at that particular hospital on that particular day in that particular area under the siege of an active shooter. Additionally, in ASIs, the medical practitioner's expertise does nothing to put them in a unique position to help or protect. Although they are uniquely qualified to help after the damage has been done, their medical expertise does not provide special help in dealing with an active shooter. Importantly then, if HCPs have a responsibility to help and protect patients in ASIs, and this responsibility arises from their unique position, this same responsibility would apply to everyone else who happens to be in that hospital, on that day, and in that area.

Second, the uncertainties that accompany an infectious disease epidemic are less dynamic than those that accompany an ASI. Once an epidemic level spread of an infectious disease has been realized, the general nature of the disease, the disease vectors, and the range of harms to infected individuals have usually been identified. The degree of risk and the harms associated with that risk can be relatively well-defined, as they were for the Ebola Virus outbreak. In ASIs, however, no set of universal precautions will limit likely exposure to harm. The vectors of harm, the spread of that harm, and the risks to individuals remain unknown and unknowable within the situation. Indeed, even attempts to flee could take the practitioner into the line of fire rather than away from it.

Another possible comparison we can draw to ASIs is the expected response during a natural disaster. If an earthquake, fire, flood, or other similar disaster were to befall a hospital full of patients, there is no question that the hospital and HCPs would be obligated to protect patients from harm. As the bioethicist Bob Baker suggests, “The duty of care requires taking some non-medical risks to save one's patients, but not risks so great that they are likely to end in the deaths of both physician and patient.”45 We agree, however in our view, such obligations arise from the HCPs presence during the event as well as their likely greater familiarity with protocols for evacuation at that particular hospital. Similarly, the insignificance of medical expertise in protecting patients in ASI and the dynamic uncertainty of ASIs categorizes these obligations less as obligations of HCPs per se, but as individuals who happen to be in a position to help in some more or less limited ways.

The dynamism of ASIs precludes an algorithm or even steps to guide HCPs and others in these situations. Further, the unimportance of medical expertise in addressing the threats of the situation lead us to conclude that the obligations of HCPs in ASIs are no different than the obligations of other individuals who happen to find themselves in this tragic circumstance.

Given that oftentimes ethics intersects with legal statutes and guidelines, an analysis of the legal obligations of HCPs during an ASI may be instructive. Legal precedents exist governing the duty of physicians to treat patients in everyday and extreme scenarios such as pandemics, which can help guide the duty of physicians in an ASI given the threat to a provider's safety that inherently exists in these situations.

In a 2010 Canadian Medical Association Journal article surrounding physicians' legal duty of care during a pandemic, Davies and Shaul state that “physicians owe a duty of care only to their existing patients, even in an emergency” because in that case a physician-patient relationship already exists. However, it can be presumed that in the case of an active shooter, HCPs will not just pick their own patients to save over others. In most western countries, in the event a physician comes to a person's aid during an emergency, a physician-patient relationship is created “and therefore [has] assumed the resulting liability.” However, in such cases liability of physicians is usually “limited to that of gross negligence or acts that are committed in bad faith,” which is consistent with the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness (PREP) Act in the United States. This act provides immunity from liability except for willful misconduct to those combating a public health emergency.Reference Davies and Shaul46 This is also consistent with the Good Samaritan doctrine that exists in all U.S. jurisdictions as a common law which shields healthcare providers who volunteer their services in an emergency situation from liability.Reference Rosenbaum, Harty and Sheer47 Current U.S. law “protects practitioners from being held to standards of conduct that are not reasonable under the circumstances, including severe constraints prevalent in disasters.”Reference Bensimon48 Therefore, if a physician came to the aid of a victim in an active shooter situation they would be establishing a physician-patient relationship thereby assuming liability; however given that the situation would be deemed an emergency or disaster scenario, it would follow that they would be liable only in the event of gross negligence or if acting in bad faith.

As was alluded to earlier, there are certain acceptable hazards with being an HCP and “when physicians join the healthcare profession, they implicitly accept a level of risk associated with the profession.”49 It is reasonable to assume that physicians in a position in the front line of the hospital, such as emergency medicine, understand the possibility of caring for patients in a pandemic when joining the healthcare profession, but it is unlikely that same emergency physician would consider an ASI to be an acceptable hazard of their profession. That said, there are protections for employees from dangerous working environments under the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 mandates that employers provide their employees with a place of employment that is “free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm.”50 An employee does have the right to refuse work but only when the following conditions are met: 1) they have asked the employer to eliminate the danger and they have failed to do so; 2) the employee believes that an imminent danger exists; 3) a reasonable person would agree there is real danger; and 4) there is no time to request OSHA inspection.Reference Simonds and Sokol51 If an employee were to refuse work secondary to the dangerous condition, the employee “would be protected against subsequent discrimination.”52 Given the now federally mandated training and awareness that healthcare employees must obtain on ASIs, it would be hard to argue that an ASI is not considered a “recognizable hazard.” It is reasonable to conclude that existing Good Samaritan laws should provide legal protection to physicians who volunteer their services during an active shooter incident, but OSHA laws may protect those who deem the environment too unsafe to respond.

Unfortunately, our review of the literature led to more questions than it provided answers. How is an individual supposed to react in this situation? What is an HCP's moral and professional obligation to their patients at that moment? If an HCP follows the “Run-Hide-Fight” paradigm, are they abandoning their patients? If federal guidelines recommend running away from the facility, then it leaves patients not only defenseless and unprotected, but without medical attention until an “all clear” can be provided by law enforcement.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, our review of the literature led to more questions than it provided answers. How is an individual supposed to react in this situation? What is an HCP's moral and professional obligation to their patients at that moment? If an HCP follows the “Run-Hide-Fight” paradigm, are they abandoning their patients? If federal guidelines recommend running away from the facility, then it leaves patients not only defenseless and unprotected, but without medical attention until an “all clear” can be provided by law enforcement. This may be an inordinate amount of time for patients who are newly wounded or previously critically ill. Hence, of the options presented we must join the several authors who reject “Run-Hide-Fight” as a mandate for the healthcare environment during an ASI. Accordingly, we endorse “Secure, Preserve, Fight” as advocated by Inaba et al., as this recommendation is most in line with the professional obligation of HCPs to their patients as well as the expected societal moral obligations to not run away from the healthcare facility thereby leaving vulnerable persons unprotected. At the same time, we lack strong justification to describe “Secure, Preserve, Fight” as mandated or morally obligatory for HCPs in all circumstances. But our endorsement of this aspirational standard entails a greater responsibility for healthcare institutions to provide resources to provide securable areas during an ASI, as well as facilitating HCPs' duty to treat.

As to the question of abandonment, the guidance provided by federal regulatory agencies and most professional societies states that no HCP can be forced to stay during an ASI, and hence they will not be abandoning their patients if they decide to run away. When an active shooter enters a hospital, HCPs must make difficult ethical decisions in a chaotic moment that could put their lives at danger, and which will not only affect their lives but the lives of their loved ones and co-workers as well. It seems the one consistent answer we can surmise is that there will be some individuals who will choose to put their lives in danger during an ASI despite these risks. The premise that some individuals may or will do this does not relieve the organization from its responsibilities to limit the risk to patients and staff.

An ASI is extremely difficult to manage for all involved and is further complicated when it occurs in a healthcare setting. The vulnerabilities of patients at their physical and mental worst prompts the courageous amongst us to want to help no matter what the consequences to their own lives may be. As Iserson concluded,

The decision to stay or leave will ultimately depend on individuals' risk assessment and their value systems. Professional ethical statements about expected conduct establish important professional expectations and norms, but each individual will interpret and apply them according to his or her own situation and values. Recent historical precedent suggests that many physicians and other health care providers will courageously care for the sick and needy, even at great risk to themselves.53

This review leads us to surmise that HCPs have professional obligations to care for their patients in an ASI, which makes running away a difficult option to accept. During an ASI this obligation is not necessarily lessened. Hospitals are unique environments designed to allow free access to most of the public. As a result, this leads to several unique vulnerabilities and infrastructural challenges that need to be addressed by the healthcare institutions themselves. As many authors, such as Eckenwiler state, institutions have an ethical obligation to protect their patients and staff from workplace violence and emergencies through a multi-faceted approach. Reliance on the few individually-motivated HCPs akin to a Bruce Goldfeder,54 will essentially be playing Russian roulette with the lives of staff, patients, and families. Each hospital's Emergency Management Committee needs to regularly update and educate hospital staff about active shooter response plans. Many authors have recommended that hospital administrators consider training key staff in the use of antiballistic armor or employing properly trained and equipped hospital security guards until law enforcement arrives in the event of an ASI. Most importantly, there needs to be a change in the culture, from one where security personnel are thought to be the sole responsible parties for a safe and secure environment to one where safety is everyone's responsibility. HCPs need to all be aware of their environment and those in it at every moment and in every location. They would be well served with training to read behavioral clues and in de-escalation strategies for potentially dangerous situations.55

In conclusion, after an extensive literature review and bioethical analysis, the decision to remain or flee during an ASI is personal and one no professional, federal, or regulatory agency can mandate. Those who choose to stay do so based on their own personal moral code and duty to serve during crisis situations.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Professors Rosamond Rhodes and Robert Baker for their unwavering support in the writing and editing of this manuscript, without which this work would not have been possible.