Introduction

The United States stands alone among high-income nations with its high rates of firearm injury. Additional epidemiological analysis can help to evaluate and address this crisis.Reference Davis1 To guide future epidemiological studies and policy interventions, we propose applying the social ecological model for violence prevention to firearm injury.

Causes of Firearm Injury

In 2018, 39,740 people died from firearm-related injury — more than from motor vehicle-related injury.2 The primary causes of firearm-related injuries are suicide and homicide. The term firearm injury encompasses both fatal and non-fatal injury, which may lead to lasting functional impairment and psychological harm. This term does not even encompass the emotional and psychological injuries that may result from witnessing or being threatened with gun violence.

Firearm Suicide

Suicide is the principal cause of firearm-related mortality, representing at least 61% of firearm deaths in 2018.Reference Anglemyer, Horvath, Rutherford, Siegel and Rothman3 Firearm injury accounts for more suicides than all other modes of suicide combined, at least in part due to the lethality of firearms. In a 2014 meta-analysis, Anglemyer and colleagues found that the odds of dying by suicide were three times greater among those with firearm access than those without.4 Higher firearm prevalence is associated with higher rates of total and firearm suicide at the state level,5 a robust association even when adjusting for the prevalence of serious mental illness and substance use.Reference Miller, Lippmann, Azrael and Hemenway6 Risk for firearm suicide increases with ageReference Wintemute7 and gun ownership. White males have a greater risk of firearm suicide than Black or Hispanic males,Reference Riddell8 although this association is likely mediated, in part, by the higher prevalence of firearm ownership among white men.Reference Azrael9 Rurality is also associated with higher rates of firearm suicide, alongside higher rates of firearm ownership.Reference Branas10 Neuropsychiatric disorders, such as depression and bipolar disorder, as well as traumatic brain injury are associated with a greater risk for suicide.Reference Fazel and Runeson11 Static risk factors that predispose an individual to suicide, such as neuropsychiatric disorders or adverse childhood events, interact with precipitating risk factors, such as social isolation, stressful life events, and access to lethal means. Suicide attempt is often an impulsive act,Reference Deisenhammer12 therefore reducing access to lethal means, including limiting access to firearms, is a cornerstone of suicide prevention.Reference Barber and Miller13 While mental illness is an important risk factor for firearm suicide, most decedents do not have a known mental health condition.Reference Stone14

Firearm Homicide

Most homicides in the U.S. are committed with a firearm.15 Firearm homicide is most common among young males,16 and disproportionately affects Black males, who are subject to 9-57 additional firearm suicides per 100,000 per year relative to white men, depending on the state.17 Firearm homicides are con-centrated in urban areas.18 The proportion of individuals living in poverty and the proportion of males living alone are associated with higher rates of firearm injury; in contrast, increased social spending and economic opportunity are associated with lower rates of firearm injury.Reference Kim19 Therefore structural racism — defined as “the totality of ways in which societies foster [racial] discrimination, via mutually reinforcing [inequitable] systems … that in turn reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources” — may play an important role in health disparities in the burden of firearm homicide observed between Black and white individuals.Reference Bailey20 Although police-involved firearm deaths are excluded from most analyses of firearm homicide, police shootings contribute significantly to mortality among young Black men.Reference Edwards, Lee and Esposito21 The May 25, 2020 filmed murder of George Floyd in Minnesota by members of the Minneapolis Police Department has embodied this issue of structural racism, and galvanized discussion about police targeting Black people with especially violent responses for hundreds of years. The firearms murder on March 13, 2020 of Breonna Taylor, an emergency medical technician working for the University of Louisville Health, was another case in point, as she was shot eight times without cause in her own home.

While women experience a lower rate of firearmrelated injury than men, contributing factors are somewhat different. Intimate partner violence is experienced by women at higher rates than menReference Miller and McCaw22 and firearm accessibility is a risk factor for intimate partner homicide.Reference Campbell23 Firearm injury is the second-leading cause of death among children and adolescents (ages 1-19), particularly by homicide.Reference Cunningham, Walton and Carter24 Firearm homicides among children are associated with criminal- or gang-related activities as well as family violence.Reference Fowler25

Social Ecological Model of Firearm Injury

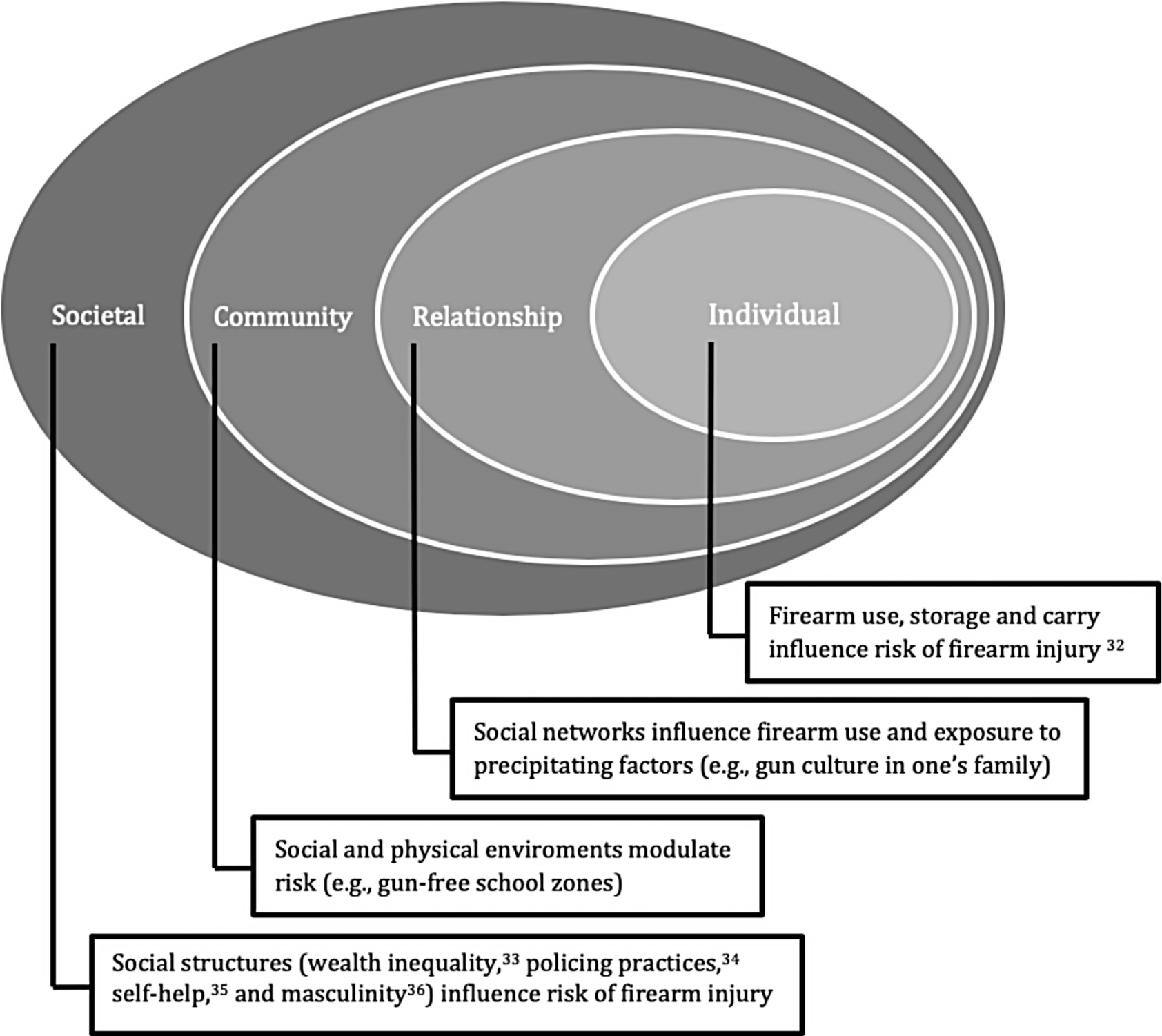

The social ecological model (SEM) is a conceptual framework widely utilized in public health which posits that health outcomes result from individual and environmental factors, which modify risk for the outcome. Risk and protective factors are organized in four levels: the individual, relationship, community, and societal. The SEM has been applied to diverse public health problems including HIV/AIDS risk assessmentReference Baral26 and vaccine promotion,Reference Kolff, Scott and Stockwell27 as well as violence prevention. The World Health Organization proposed the use of the SEM for violence prevention in its 2002 World Report on Violence and Health.Reference Krug28 This approach is also supported by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.29

As applied to violence prevention, the individual level of the SEM includes individual factors that influence the risk of being a victim of violence; the relationship level includes characteristics of one's social network of family, friends, and peers; the community level includes the social and physical environment of neighborhoods, schools, and businesses; and the societal level includes policy, economic, and cultural factors that modify risk.30 Allchin and Kaskie have each proposed an SEM to stem firearm suicide; the former focuses on limiting access to lethal means, while the latter focuses on limiting suicide in older age. The specificity of each lends valuable insights about how to reduce risk of firearm suicide.Reference Allchin, Chaplin, Horwitz, Kaskie, Leung and Kaplan31 Building on this previous work, we propose an SEM of firearm injury that captures all modes and intentions. This expanded SEM provides a useful framework for guiding firearm policy analysis and future epidemiological studies of firearm injury prevention (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The Social Ecological Model Applied to Firearm Injury and Death

Laws and policies can influence risk at various levels of the model. Below we provide examples that illustrate how laws can modulate risk at various levels of the SEM. These particular laws and policies were selected for this analysis because they represent core issues surrounding gun ownership and use in U.S. society.

Social Ecological Model: Individual Level

Stand Your Ground (SYG)

Historically, U.S. law has enforced a “duty to retreat” on individuals before permitting their use of force to defend themselves or others from harm, except when in their home. SYG laws have reversed this “duty to retreat,” legalizing the use of deadly force to defend oneself or others regardless of whether it is possible to retreat. Florida was the first state to implement an SYG law in 2005. Humphreys et al. found that implementation of Florida's SYG law was associated with a 31.6% increase in firearm homicide.Reference Humphreys, Gasparrini and Wiebe37 Other studies have noted that the increase in firearm homicide has been greater in counties that were suburban, predominantly white, higher-income, and had lower rates of homicide prior to the enactment of the SYG law;Reference Ukert, Wiebe and Humphreys38 and that adolescents also experienced an increase in firearm homicide.Reference Esposti39 Florida also provides an important example of how SYG Laws can exacerbate racial disparities in health. Degli et al. found that Black adolescents made up a greater proportion of firearm homicide victims after the enactment of Florida's SYG law compared to before.40 An SYG case study is the February 26, 2012 unprovoked firearm murder of Trayvon Martin by self-appointed vigilante George Zimmerman, with subsequent acquittal of the white murderer of the Black 17-year old. Systemic racism is apparent in the application of the law; the odds of convicting a defendant of homicide were two times greater in cases where the victim was white compared to cases where the victim was non-white.Reference Ackermann41

The finding that SYG laws are associated with increased rates of homicide is not consistent across states, however. Two studies evaluating SYG Laws in TexasReference Ren, Zhang and Zhao42 and ArizonaReference Chamlin43 found no association with increased homicide. Cross-sectional studies examining the relationship between SYG laws and firearm injury have found significant associations,Reference Kalesan, Crifasi and Castillo-Carniglia44 while others have not.Reference Knopov45 The inconsistent findings of cross-sectional studies may be due to true heterogeneity in the impact of SYG laws on individual states, or may reflect methodological differences in data sources, time periods studied, and selection of confounding variables in their models. Importantly, while there is emerging evidence that SYG laws are associated with increased incidence of firearm homicide, there is no evidence that SYG laws are associated with reduced incidence of burglary, robbery, or assault.Reference Cheng46 These findings suggest that SYG laws fail to accomplish their stated goal of deterring crime.

SYG laws modulate risk at several levels. At the individual level, SYG laws may influence an individual's decision to carry a firearm for self-defense as well as their assessment of when it is legal to use their firearm. SYG laws remove penalties for the use of lethal force for highly subjective causes (“feeling threatened”); this may predispose individuals to preemptive violence.Reference Loftin47 SYG may act at the relationship level as well. For example, an individual may use a firearm in a physical altercation in part because he is aware that the other individual would be legally justified in doing the same, like a duel or gunfight, with minimal fear of legal consequences.

SYG laws also modulate risk at the societal level because they interact with societal norms. These laws may influence, and be influenced by, social norms around self-help, where an individual must rely on himself to carry out justice. The Trayvon Martin murder,Reference Coates48 as well as the research findings of Esposti49 and Ackermann,50 highlight how SYG laws interact with structural racism to harm people of color. Lobbying and affinity organizations such as the National Rifle Association have promoted SYG laws successfully in 27 states as of June 2020.

Universal Background Checks

Universal Background Check (UBC) laws may be understood as interacting at both the individual level and the societal level. Federal law mandates background checks on individuals who purchase firearms from licensed firearm dealers, conducted via the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS).Reference Jehan and Lee51 However, background checks are not federally mandated for private sales, with one out of five firearm owners reporting firearm acquisition without a background check.Reference Miller, Hepburn and Azrael52 Seventeen states have passed UBC legislation or require state-issued permits as of June 2020, mandating background checks for all firearm sales including those between private parties.53 An additional six states have such provisions for handguns only.

State-level cross-sectional and quasi-experimental longitudinal analyses have found a significant association between the presence of UBC legislation and a lower firearm mortality rate, driven by a lower firearm homicide rate.Reference Goyal54 However, Crifasi et al. and Castillo-Carniglia et al. both reported that UBC legislation was not associated with lower firearm mortality rates, possibly due to differences in study population (large urban counties and the state of California, in contrast to all 50 states).Reference Castillo55 The NICS is limited by voluntary state reporting mechanisms, so data are incomplete.56 Locally conducted UBCs may benefit from more complete data, and these have been associated with lower firearm mortality rates,Reference Sumner, Layde and Guse57 supporting improvement in UBC mechanisms to ensure data completeness.

Social Ecological Model: Relationship Level

Child-Access Prevention (CAP)

CAP laws seek to hold a firearm owner criminally liable if their firearm is involved in the injury of a child or is inappropriately accessed by a child. CAP laws are a heterogenous group of legislation that vary between states in several ways. Laws vary widely by scope, severity of penalty, and maximum applicable ages.58

CAP laws interact at the relationship level, modulating risk to children by seeking to influence behavior of the parents and other adults in the child's primary social network. By encouraging safer firearm storage practices among adults, CAP laws seek to prevent children from accessing firearms during times of crises or engaging in high-risk firearm behaviors such as unsupervised use of firearms or playing with firearms.

There is robust evidence that CAP laws are associated with a reduction in pediatric firearm injury.Reference Cummings, DeSimone, Markowitz, Xu, Hamilton, Hepburn and Webster59 This association has been found in both cross-sectional studies that compare rates of injury between states with and without CAP laws60 and quasi-experimental studies that compare the difference in rate of injury before and after CAP law enactment with difference in rate of injury in states that did not enact CAP laws.61 Individual studies have found an association between the presence of a CAP law and reductions in pediatric firearm suicide,62 unintentional firearm death,63 firearm homicide,Reference Azad64 and nonfatal firearm injury.65

While a few studies have not found a significant association between CAP laws and reduction in firearm injury, there are notable methodological flaws. For example, Lee et al. selected hospitalizations for firearm injury in those aged 0-20Reference Lee66 even though most of these individuals are older than the maximum age covered by CAP laws. Therefore, the current body of evidence supports the presence of an association between CAP laws and reductions in pediatric firearm injury.

Extreme Risk Protection Orders

Extreme Risk Protection Order (ERPO) laws permit families, household members, law enforcement officers, and — in certain states — health care professionals to petition courts to remove firearms temporarily from an individual's possession. ERPO laws, colloquially described as “red flag” laws, are becoming increasingly common in the U.S. As of July 2020, 19 states and the District of Columbia had enacted ERPO or similar laws; nearly all were passed within the past five years.Reference Rowhani-Rahbar67

ERPO laws interact at the relationship level, modulating risk to the firearm owner through intervention at the relationship level. For example, a woman may believe her brother is temporarily at risk of harming himself. She can file an ERPO petition to request that the court order that the firearm be temporarily removed from her brother's possession.

Although the vast majority of ERPO laws are recent, with most having gone into effect since 2016,68 studies of ERPO laws in ConnecticutReference Swanson69 and IndianaReference Kivisto and Phalen70 suggest that they represent promising, effective tools to reduce risk of firearm injury. Additional cross-sectional studies in California and Washington provide detail about the characteristics of the respondents, the petitioners, and the bases for their ERPO petitions. In both states, law enforcement officers represented the vast majority of petitioners. In California, respondents were most often white men, corresponding to the demographics of firearm owners in the state.Reference Pallin71 In Washington, the petitioner in over half of all cases reported that the respondent had a history of suicidal ideation.72

Social Ecological Model: Community Level

School Weapons Ban

High-profile mass shootings such as those in Columbine High School (Colorado in 1999), Virginia Tech University (Virginia in 2007), Sandy Hook Elementary School (Connecticut in 2012), and Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School (Florida in 2018) propelled firearm injury into the spotlight. The sheer rapidity with which children, adolescents, young adults, and teachers could be murdered with modern assaultstyle weapons has been highlighted over the past two decades. The Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1995 sought to prohibit possession or discharge of a firearm within a school zone. Firearm regulation in early care and education settings uses a similar approach.Reference Benjamin-Neelon and Grossman73 Both policies can be classified as community-level interventions, as they seek to create firearm-free environments for children. While school-associated violent deaths are rare events, school weapons bans are illustrative of how legislation may interact at the community level to influence the availability of firearms in an environment and reduce firearm risk.

The SEM provides a framework for considering how legislation modulates firearm risk. In order to address firearm violence comprehensively, legislators should design policies that intervene at multiple levels of the SEM. In designing these policies, legislators may consider how factors such as state boundaries complicate how policies act at varying levels of the SEM. Legislators may also wish to consider legislation that incentivizes behavior that decreases firearm risk, rather than prohibiting behavior that increases risk.

Social Ecological Model: Societal Level

Typically, legal policy is uniformly assigned to the societal level of the SEM. We propose that laws that act primarily on the structural determinants of violence should be classified as acting at the societal level. Examples include policies that impact economic, health, educational, and criminal justice structures that modulate risk of violence. In addition, funding priorities can modulate risk. Policies designed to decrease firearm risk, such as training healthcare professionals to engage in lethal means safety counseling, can only succeed if they are sufficiently funded.74

Conclusions

Patterns of firearm injury have complex causal pathways. Similarly, firearm legislation may act upon these pathways in different ways to modulate risk. The SEM highlights the complex interactions between social structures, legal policy, social networks, and individual behavior, and provides a framework for assessing these interactions. We have provided an introduction to the SEM and how it may be employed to assess firearm legislation.

The SEM provides a framework for considering how legislation modulates firearm risk. In order to address firearm violence comprehensively, legislators should design policies that intervene at multiple levels of the SEM. In designing these policies, legislators may consider how factors such as state boundaries complicate how policies act at varying levels of the SEM. Legislators may also wish to consider legislation that incentivizes behavior that decreases firearm risk, rather than prohibiting behavior that increases risk.

The use of the SEM model is also beneficial because it borrows a framework familiar to public health, social and behavioral science, and medical professionals, thus encouraging cross-disciplinary engagement with law and policy. Legislators and public health practitioners may consider the SEM when drafting laws and designing studies. Additional research can clarify how laws and policies modify risk at various levels of the model, in order to inform future legislation.

Conscientious multidisciplinary collaboration can promote evidence-based solutions to firearm injury in the United States.Reference McGinty75 The application of the SEM to firearm injury may guide collaborative efforts between these stakeholders to reduce our nation's high burden of firearm injury.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professors Abbe Gluck and Ian Ayres for their counsel. Allison Durkin and Christopher Schenck contributed equally to the article.