I. Introduction

Despite the fact that death by neurologic criteria (typically termed “brain death”) is legal death throughout the United States, a number of recent lawsuits have questioned the legitimacy of determinations of death by neurologic criteria.Reference Lewis, Cahn-Fuller and Caplan1 Because of this, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) grew concerned that prolonged and highly publicized litigation questioning declarations of brain death could undermine public trust in medical determination of death.2 In response to these concerns, the AAN convened an interdisciplinary summit of representatives from healthcare specialty organizations with direct professional interest in brain death determination in October 2016.3

The summit attendees published a report of their discussion that was endorsed by eight medical stake-holder societies in the determination of death by neurologic criteria.4 These included: (1) the AAN, (2) American Academy of Pediatrics, (3) American College of Chest Physicians, (4) American College of Radiology, (5) American Neurological Association, (6) American Society of Neuroradiology, (7) Child Neurology Society, and the (8) Neurocritical Care Society. The report reviewed the 50-year history of using neurologic criteria to declare death in the United States and addressed (1) the need for systems to ensure that brain death determination is consistent and accurate and (2) the proper response to family objections to determination of death by neurologic criteria. The attendees identified several concrete steps needed to bolster public trust in use of neurologic criteria to declare death.

One key goal embraced at the summit was to advocate for a consistent statutory approach to brain death determination in all U.S. jurisdictions.Reference Lewis, Bernat and Blosser5 Since 1981, the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) has served as the legal foundation for the medical practice of determining death.6 However, in recent years, litigation challenging the use of neurologic criteria to declare death has questioned the authority of the UDDA.7 These developments have exposed unresolved ambiguities in the legal rules governing determination of death that must be addressed.

One key goal embraced at the summit was to advocate for a consistent statutory approach to brain death determination in all U.S. jurisdictions. Since 1981, the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) has served as the legal foundation for the medical practice of determining death. However, in recent years, litigation challenging the use of neurologic criteria to declare death has questioned the authority of the UDDA. These developments have exposed unresolved ambiguities in the legal rules governing determination of death that must be addressed.

In this article, we make the case for a Revised Uniform Determination of Death Act (RUDDA). In Section II, we review the history of laws governing neurologic criteria to declare death in the United States. In Section III, we summarize the contemporary statutes and case law bearing on neurologic criteria to declare death, paying close attention to variations among state laws and areas of ambiguity. Finally, in Section IV, we discuss proposed revisions to the UDDA and explain the need for these modifications to the bar, health professionals, and the public.

II. History of Laws Governing Use of Neurologic Criteria to Declare Death

After the medical community first created a standard for defining death by neurologic criteria, in the late 1960s, courts and legislatures began to provide legal support for death determined in this manner.Reference Lewis and Scheyer8 Unfortunately, states took many different approaches to provide legal authority to the use of neurologic criteria to determine death, creating significant variability and confusion. To rectify this, in recognition of the importance of uniformity in determination of death, in 1981, in consultation with the American Medical Association (AMA) and American Bar Association (ABA), a congressionally convened expert committee drafted and recommended that all states adopt the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA).9

A. Need for Legislation about Brain Death

Until the 1950s, the sole recognized method of determining death was observation of irreversible cessation of all circulatory and respiratory functions.Reference Bernat10 Introduction of mechanical ventilation, which facilitated gas exchange to maintain organ function despite the loss of a brain-initiated drive to breathe, prompted reconsideration of the traditional concept of death. In 1959, clinicians in Europe first reported and characterized a process of determining death by neurologic criteria.Reference Mollaret and Goulon11 Ten years later, in 1968, an ad hoc committee at Harvard Medical School published a report that in addition to the use of cardiopulmonary criteria to declare death, the medical community was prepared to adopt criteria for declaring death based on irreversible loss of brain function.12

Initially, some clinicians thought that the emerging medical consensus on using neurologic criteria to declare death might provide a sufficient foundation for a change in practice recognizing brain death as legal death.Reference Ryan13 Indeed, the Harvard ad hoc committee declared, “no statutory change in the law should be necessary since the law treats this question essentially as one of fact to be determined by physicians.”14

However, this assessment proved erroneous. First, physicians themselves wanted a higher level of legal clarity and certainty, validating the use of neurologic criteria to declare death, that only a statute can provide.Reference McCabe15 This was particularly true in the context of organ transplantation, because several physicians had been sued or criminally prosecuted for removing organs from people who were declared brain dead, but still had beating hearts.Reference Capron and Kass16

In addition to clinicians' desire for legal clarity, a consensus emerged among medico-legal experts that a law was necessary, because a change in the concept of death is not “entirely a medical matter.” Defining death involves value-laden judgments and has numerous emotional, social, economic and legal consequences including mourning, burial, taxation, inheritance and criminal prosecution.17

Therefore, as explained in 1981 by the President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research, while physicians could create the specific technical aspects of death determination, it was necessary for an “interdisciplinary, broadly-based public body” to consider the concept of death and the use of a new set of criteria to declare death on a societal level.18 “Society as a whole must judge that [the standards created by physicians] conform to the society's settled values and accepted conceptions of human existence and personal rights. This judgment will be most clearly expressed through the medium of the law of the land.”19

B. Road to Uniform Brain Death Legislation: History of Inconsistent Brain Death Laws

In the early 1970s, many states responded to requests for legislation on the determination of death, undertaking the challenge of embodying in law the medical consensus regarding the use of neurologic criteria to declare death. Unfortunately, there was no consistent legal formulation and many different approaches were taken. For example, Kansas enacted the first brain death statute in 1970, and several states followed its approach.Reference O'Hara20 The Kansas model was problematic, though, because it suggested that there were two types of death, rather than two ways to determine a single phenomenon of death.Reference Veith21 Over the ensuing decade, the ABA, the AMA and the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws separately proposed model statutes, but none of them attracted widespread adoption.22

Adding to this “cacophony” of statutory approaches, states did not follow any of the available models in a consistent manner.Reference Nipper23 First, some versions failed to mention the brainstem, suggesting that there was no difference between permanent unconsciousness due to loss of higher brain function and death.24 Second, some versions failed to reference the traditional cardiopulmonary criteria for death, creating uncertainty over their status. Third, some versions referred to organ donation, suggesting that determination of death by neurologic criteria was only relevant to donors, or, worse, was singularly motivated by organ donation.25 Fourth, some versions mentioned continuation of organ support after brain death, which implied that brain death is not death of a person.26 Finally, some versions advocated the use of different criteria to declare death for different purposes (e.g., inheritance, taxes, criminal trials, medical treatment).27

To be clear, there was no disagreement about the basic concept of brain death. Most states recognized brain death as death,28 yet the plethora of statutory models was confusing. Even worse, differences in statutory language suggested that a person could be simultaneously dead in one state, but alive in another state.

C. Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA)

By the late 1970s, key policymakers recognized that there were too many “variations among the laws of several states.”29 In response, in 1978, Congress enacted legislation creating the President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research (the Commission).30 The statute specifically charged the Commission to study “the matter of defining death, including the advisability of developing a uniform definition of death.”31

In 1981, the Commission published its report and proposed a model statute for determining death by the application of either of two alternative standards: (1) “irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory function” or (2) “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem” in “accordance with accepted medical standards.”32 Notably, the two criteria in the model statute are disjunctive. The satisfaction of either cardiopulmonary or neurologic criteria is sufficient to determine death. As such, if clinicians confirm cessation of all brain functions, then they should declare death, despite ongoing cardiopulmonary functions in the setting of artificial ventilation. Prudently, the Commission coordinated its work with authors of the existing statutes, resolving the confusion between different legal models for defining death.33

D. Importance of Uniformity in Determination of Death

Both Congress (in forming the Commission) and the Commission itself (in conducting its study) concluded that uniformity in the determination of death is highly desirable and that death should not be a negotiated standard. The same basic rule about who is dead, and who is not dead, should apply everywhere in the United States. An individual should not be simultaneously dead and alive pursuant to the laws of two different states. It should not be possible to “statutorily resurrect” a person from state A merely by applying law of state B.Reference Goldsmith34 The Commission repeatedly emphasized the importance of eliminating the “harm that is risked by diversity.”35 The Commission felt so strongly about the importance of uniformity that it was tempted to propose that the federal government enact a statute to preempt the field.36 However, the Commission ultimately concluded that principles of federalism required first attempting uniformity at the state level. It observed that federal legislation would be necessary only if state uniformity could not be achieved.

The Commission's view was not unique. The importance of uniformity in defining death was widely recognized. Some have even described it as “unconscionable” for different jurisdictions to treat death differently.37 Certainly, laws on many subjects diverge across jurisdictions. That usually just creates an inconvenience. In contrast, here, it has a “jarring effect.”38 “There is no question that the subject is one of basic importance to any society: who is alive and who is dead?”39 State-by-state variation is not justified on a matter that is so fundamental.40 As Capron and Kass observed in 1972:

Uncertainties in the law are, to be sure, inevitable at times and are often tolerated if they do not involve matters of general applicability or great moment. Yet the question of whether and when a person is dead seems the sort of issue that cannot escape the need for legal clarity on these grounds.41

In short, consistency among jurisdictions is paramount on “an issue as important as determining when a human being has died.”42

Identifying the difference between life and death is of the utmost importance.Reference Abram43 The stakes for making this distinction are high.44 Many important legal decisions turn on the occurrence of death.45 These include questions of criminal law (murder vs. aggravated assault), tort law (wrongful death vs. medical malpractice), family law (status of spouse and children), property law (estate tax, probate) and insurance law (payment of life insurance benefits, termination of health insurance payments). Moreover, even apart from law, the determination that death has occurred initiates actions and culturally determined behaviors of family members, physicians, clerics, and undertakers (e.g., grieving, burial, autopsy).46 If neighboring states had different criteria for death, confusion would result, and abuse would become possible.47

Furthermore, inconsistencies in the determination of death may increase public suspicion. This can also promote conflict in intensive care units.Reference Choi, Fredland, Zachodni and Lammers48 Nonuniformity reduces credibility and trust, because it makes the determination of death seem uncertain and fallible.49 “Variability contributes to doubt about the reliability and objectivity of the determination.”50 A disordered legal framework leads to a climate of general uncertainty, shaking public confidence.Reference Downie, Kutcher, Rajotte and Shea51

E. UDDA: Concept, Criteria and Standards

The UDDA was designed to mitigate these risks by assuring consistency in legal requirements for determining death. In designing the UDDA, the Commission distinguished four levels of generality or “levels of detail” that might be incorporated into the statute.52 First, on a basic conceptual level, the “death” of a person might be understood as the “permanent loss of consciousness” or, more narrowly as the “termination of integrated functioning of the organism as a whole,” each of which acknowledges that what we regard as “death” occurs before every cell in the body “dies,” leaving no sign of any bodily activity. Second, from a more technical perspective, death can be described as “irreversible cessation” of certain bodily functions (i.e., “irreversible cessation” of cardiopulmonary functions or, in the alternative, of all function of the “entire brain”). Third, on a more nuanced operational level, one can refer to the disappearance of specific physiological functions that are indicative of the irreversible loss of all function of the heart or brain, such as breathing or responsiveness to environmental stimuli. Fourth, on the most granular level, specific tests and procedures can be identified to determine when cardiopulmonary or neurologic functions have been irreversibly lost.

In sum, the Commission dismissed the first level as inappropriate for legislation, because it is too philosophical and theological. It also dismissed the third and fourth levels as too medical and technical to be included in a statute. That level of detail is best committed to the discretion of the medical profession in deciding which functions or capacities are definitively indicative of the permanent and irreversible cessation of cardiopulmonary or neurologic functioning. The Commission settled on the second level for “defining” death, concluding that the role of law is to “establish” the legal requirements for death, while the role of physicians is to determine, based on evolving knowledge, how to “apply” or, operationalize, the legal definition.53 The task of the legislature is not to do the work of physicians in developing the medical standards for determination of death, but, rather, to denote the general condition which society will regard as “dead” for legal purposes.54

The Commission concluded it was sufficient to “restrict the compass” within which physicians would make their choices by establishing “general physiological” criteria for death.55 It further concluded that requiring that the determination of death accord with “accepted medical standards” was sufficient, because that brings to bear all the usual methods and procedures for assuring accuracy in medical diagnosis.56 “Once the public has set its goal, specialists in the field can be delegated the responsibility of elaborating the means toward it.”57

Accordingly, the UDDA leaves physicians and other biomedical specialists discretion to “fill in” the technical details.58 The Commission determined that it was not only unnecessary, but also misguided, to enshrine any particular medical standards into a statute, because specific medical standards could easily change with advances in biomedical knowledge and refinements in technique.Reference Bernat, Culver and Gert59 With the advance of science, new standards and tests could be “repeatedly generated.”60

F. Conscience Clause

The UDDA establishes only the physiological criteria for determining death. The Commission considered addressing other matters like conscience-based objections to the use of neurologic criteria to determine death. But it rejected the proposal to do so after concluding that “such a provision has no place in a statute on the determination of death.”61 Worse, “were a non-uniform standard permitted, unfortunate and mischievous results are easily imaginable.”62 Nevertheless, the Commission conceded that room remains for reasonable accommodation of the wishes of family members after determination of death.63

III. Contemporary Statutes Governing Brain Death Determination

It has been 60 years since the introduction of the idea of brain death, 50 years since the proposal of the first standards for brain death determination in the United States, and nearly 40 years since promulgation of the UDDA.64 Brain death is legal death throughout the United States. The ability to use neurologic criteria to declare death is incorporated in general statutory law in 48 states; the remaining states judicially adopted the UDDA.65

Despite this, the UDDA's goals are not being met. The complete language of the UDDA is included in only two-thirds of state laws.66 Additionally, interpretation and judicial application of the UDDA vary from state to state in material ways. These variations include: (1) legal criteria for determination of death; (2) accepted medical standards for determination of death by neurologic criteria; (3) response to family objections to determining brain death; and (4) response to family objections to terminating organ support after determination of brain death.

A. Legal Criteria for Determination of Death

There are two sources of variability and uncertainty in the legal criteria for determination of death. First, the language describing the legal criteria for determination of death in state laws is not uniform. Second, and perhaps more importantly, the meaning of “all functions of the entire brain” is ambiguous.

Some states do not include the full language of the UDDA in their determination of death statutes. In these states, the wording deviates from the UDDA in two ways.67 First, the phrase “irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory function” is not included in Arizona or North Carolina.68 Arizona's statute merely indicates that a determination of death must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards, while North Carolina's mentions both accepted medical standards and irreversible cessation of total brain function, but does not mention cardiopulmonary criteria for death. Second, the phrase “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem” is not included in six states (five refer to the entire brain, but do not specifically mention the brainstem).69

Additionally, the definition of “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem” is not as straightforward as it might seem. What does “functions” actually mean? And what does “entire brain” refer to? From a purely biological standpoint, this phraseology has proven to be somewhat vague and contentious, particularly with respect to consideration of hormonal function due to activity of the pituitary gland and hypothalamus. Clinicians generally acknowledge that hormonal activity may persist after brain death.Reference Wijdicks, Varelas, Gronseth, Greer, Nakagawa, Ashwal, Mathur and Mysore70 For example, after brain death, the reported rates of diabetes insipidus, which results from failure of the pituitary gland to secrete antidiuretic hormone, range from 9-90%.Reference Shah, Bronheim, Fisher, Alexander, Ali, Wong, Tan, Goh, Zambergs and Vyas71 But if the pituitary gland is still secreting antidiuretic hormone, does that mean a portion of the brain is still functional? In short, are the pituitary gland and hypothalamus part of the entire brain?

If the answer is yes, then the accepted medical standards for declaration of brain death are not consistent with the legal requirements for declaration of death. Even if the answer is no, the mere fact that the question needs to be posed demonstrates that there is confusion about the legal description of the regions of the brain that must be nonfunctional for death to be declared.Reference Dalle Ave and Bernat72

Although the question about hormonal activity has evoked ongoing disputation in the bioethics literature for several decades, it had little practical legal significance until recent litigation.73 For example, in McMath vs. Rosen, the family's legal position that Jahi McMath was alive turned in large part on continued hormonal function manifested by menstruation.74

B. Accepted Medical Standards for Determination of Death by Neurologic Criteria

The UDDA requires that clinicians determine death “in accordance with accepted medical standards.”75 But 13 states use variations of this phrase.76 One state (Georgia) does not reference medical standards at all.77 Alternative phraseology includes “currently accepted medical standards,” “ordinary standards of current medical practice,” “usual and customary standards,” and “generally accepted medical standards.”78

Even when states include the UDDA's exact wording describing the standards to employ when determining death in their statutes, there is confusion about what standards constitute the “accepted medical standards.” As mentioned, the drafters of the UDDA chose not to prescribe specific medical standards for determination of death.79 The Commission believed that the phrase “accepted medical standards” would sufficiently guide clinicians and courts about the manner to declare brain death legally while providing latitude for medical standards to change.80 This decision has led to three implementation challenges: (1) What professional body or bodies are responsible for identifying the “accepted medical standards”? (2) What professional or regulatory body or bodies are responsible for training and certifying practitioners who are qualified to carry out brain death determinations in accord with these standards? and (3) What professional or regulatory body or bodies are responsible for quality assurance in their administration?

A 2015 decision by the Supreme Court of Nevada illustrates the first problem. In this case, there was evidence that Aden Hailu, the patient in question, was determined dead by neurologic criteria using the standards for determination of death published by the AAN. Nevertheless, the court ruled that the hospital did not demonstrate that the AAN standard was the “accepted medical standard.”81 Rather, it noted that because the Harvard standard was the original standard for determination of brain death, and because the hospital did not demonstrate otherwise, the court considered the Harvard standard to be the accepted medical standard.82

In response to the Hailu decision and other litigation contesting brain death determinations, the attendees at the AAN summit discussed what standards constitute “accepted medical standards.”83 The summit attendees recognized the accepted medical standards for determination of brain death in the United States to be (1) the 2010 AAN standard for determination of brain death in adults, and (2) the 2011 Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and Child Neurology Society (CNS) standard for determination of brain death in pediatric patients.84 Other medical organizations with expertise in brain death, including the American College of Chest Physicians and the Neurocritical Care Society also acknowledged these guidelines as the accepted medical standards.85

The Nevada legislature responded to the Hailu case by revising the state's statute governing the determination of death.86 The amended statute refers explicitly to the AAN and SCCM/AAP/CNS standards, and any subsequent revisions of either document by these societies or their successor organizations.87 New Jersey is the only other state that mentions the AAN standard, but it does so in a much less definitive manner, stating that clinicians should make determinations of brain death using currently accepted medical standards, “including, without limitation, guidelines adopted by the American Academy of Neurology.”88

In addition to the fact that only two state laws acknowledge the AAN and SCCM/AAP/CNS standards as the “accepted medical standards,” no regulatory body is charged specifically with the task of monitoring physician practice. As a result, hospital protocols for determination of brain death often deviate from these standards.Reference Greer, Wang, Robinson, Varelas, Henderson and Wijdicks89 While this problem is not attributable to a flaw in the UDDA itself, it highlights the critical importance of professional/regulatory oversight in ensuring the integrity of the process of brain death determinations.

Research has demonstrated that practice varies significantly in a number of areas: (1) the need to exclude effects of sedative/paralytic medications or severe electrolyte/acid-base/endocrine derangements before conducting a brain death determination; (2) required minimum blood pressure and temperature to perform a brain death determination; (3) clinical components of a brain death determination; (4) techniques to perform apnea testing; and (5) requirement for ancillary testing. One important policy question — both for professional/regulatory bodies and state legislatures — is whether government oversight needs strengthening to assure quality and consistency in brain death determinations. Attendees at the AAN summit believe this is necessary.90

C. Management of Family Objections before Determination of Death by Neurologic Criteria

The need for consent prior to brain death determination is a topic of continuing debate in both medical and legal commentaries.Reference Lewis, Adams, Varelas, Greer, Caplan, Lewis, Adams, Chopra, Kirschen, Lewis, Greer, Lewis, Greer, Truog, Tasker, Truog and Tasker91 It is also increasingly the subject of litigation.92 The 1981 President's Commission believed that statutes governing the determination of death should not address family objections to the concept of brain death.93 As a result, most state statutes are silent on whether it is necessary to obtain a family's consent to perform a determination of brain death.

However, the majority of clinicians do not classify determination of death as a medical procedure and believe that, as such, it is not necessary to get consent.Reference Rady, Verheijde and Tibballs94 A 2015 survey of 201 adult neurologists found that 78% thought that clinicians do not need to obtain consent prior to brain death determination. Similarly, a 2016 survey of 197 pediatric intensivists and neurologists found that 72% thought consent was unnecessary.95 Additionally, a 2016 review of institutional protocols on determination of brain death in adults found that only one-third of protocols indicated that clinicians should contact a person's family before determining brain death.Reference Lewis, Varelas and Greer96

In addition to the fact that only two state laws acknowledge the AAN and SCCM/AAP/CNS standards as the “accepted medical standards,” no regulatory body is charged specifically with the task of monitoring physician practice. As a result, hospital protocols for determination of brain death often deviate from these standards. While this problem is not attributable to a flaw in the UDDA itself, it highlights the critical importance of professional/regulatory oversight in ensuring the integrity of the process of brain death determinations.

A few states have confirmed that family consent is not required. New York State regulations indicate that it is necessary to make reasonable efforts to notify a patient's next-of-kin before conducting a determination of brain death.97 However, the agency's binding interpretive guidance explicitly states that it is not necessary to obtain family consent.98 Similarly, Nevada's recent statute specifically states that consent is not required for determination of brain death.99 Judicial rulings in Virginia also hold that consent is not required.100

In stark contrast to what appears to be common practice (and common legal understanding, even in the absence of a statute), judicial rulings in some states have held that clinicians may not perform a brain death determination without family consent. For example, a Montana court observed that the UDDA does not “specifically grant the right to doctors or other health care providers to conduct a brain death determination. The legislature could have grant[ed] medical personnel (rather than patients or their surrogates) the authority, [but] chose not to do so.” Accordingly, when a mother objected to determination of brain death on her son, the court ruled that the patient's “mother has the sole authority [to decide]… whether any future brain functionality examinations should be administered.”101 Courts in California and Kansas have issued similar rulings.102

D. Management of Family Objections to Terminating Organ Support after Determination of Brain Death

Although the Commission did not think conscience-based objections should be included in statutes defining death, they were not against accommodating objections after determination of death.103 Over the ensuing decades, pressure for accommodation has steadily grown. States, hospitals, and physicians provide accommodation in different ways.Reference Lewis, Chopra and Kirschen104

New Jersey's statute states that “death of an individual shall not be declared upon the basis of neurological criteria…when the licensed physician authorized to declare death has reason to believe…that such a declaration would violate the personal religious beliefs of the individual.”105 The language of this statute is somewhat left up to interpretation: in the setting of such an objection, should a clinician in New Jersey perform a determination of brain death, but stop short of making a declaration of brain death and instead continue organ support until cardiopulmonary arrest? Or, should they not perform a determination of brain death and simply continue treatment until cardio-pulmonary death? Either way, this statute, in effect, leaves the choice between the use of cardiopulmonary criteria or neurological criteria in the declaration of death up to the family.

Similarly, Illinois law requires consideration of religious beliefs when determining time of death.106 How ever, unlike New Jersey, there are no implementing regulations, no judicial interpretation, and no other guidance. Yet, the plain language of the statute gives clinicians discretion to continue organ support by delaying the declaration of death later than the time that they determine death by neurologic criteria.

Out of deference to individuals who have religious objections to use of neurologic criteria to declare death, two other states offer legal accommodation to those who believe that death occurs only when the heart stops beating.107 California and New York instruct clinicians to provide reasonable accommodation to families who voice religious objections to use of neurologic criteria to declare death.108 They leave the definition of “reasonable” up to individual institutions.109

Throughout the rest of the country, the law is silent about how to manage family objections to use of neurologic criteria to declare death.110 Notably, because New Jersey's law is unique, families who object to use of neurologic criteria to declare death or to discontinuation of organ support after brain death determination sometimes try to transfer their family member to a hospital there.Reference Vazquez, Mozumder and Sanchez111 In a highly publicized case in 2014, the family of Jahi McMath successfully managed to transfer her from California to New Jersey after declaration of death by neurologic criteria.112

As one would expect, surveys of neurologists and intensivists in the United States demonstrate that families raise objections to use of neurologic criteria to declare death throughout the country, not just in California, Illinois, New Jersey, and New York.113

Given the heterogeneity of laws governing family objections to determination of death by neurological criteria and to termination of organ support after declaration of death, it should come as little surprise that institutional protocols and practices also vary widely.114 A 2016 review of brain death protocols from around the United States showed that a third of protocols from California/Illinois/New York and a majority of protocols from the rest of the country provided no information whatsoever about how to handle a situation in which a family voices a conscience based objection to brain death determination.115

Among the protocols that provided any guidance, instructions differed on a multitude of issues including: (1) the length of time to continue support after brain death determination, (2) code status if a determination is delayed or organ support is continued after brain death, and (3) the official time of death if organ support is continued after brain death. Some recommended deferring to the family's beliefs and awaiting asystole. Others suggested transferring care to another facility, obtaining a second opinion, or extubating against the family's wishes.116

Confluent with institutional protocol variations on this issue, surveys demonstrate that physicians handle family objections in a variety of ways including: (1) delaying the determination (discussed above), (2) transferring to other facilities, (3) continuing support indefinitely, (4) providing support for a fixed time, or (5) discontinuing support despite a family's objections. Even when support is continued, the specific therapies provided (nutrition, fluids, blood pressure medications, antibiotics, etc.) vary.117

Finally, the party responsible for financial coverage for ongoing treatment after brain death is not always clear. In New Jersey, insurance companies must cover continuation of organ support in the setting of religious objection to the use of neurologic criteria to declare death.118 However, this is not the case in other states. Because families are frequently unable/unwilling to pay out of pocket, hospitals may need to assume direct financial responsibility. In an attempt to address this aspect of objections to determination of death by neurologic criteria, Nevada's recently revised statute governing determination of death states that the cost of continuing organ support after determination of death by neurologic criteria may become the responsibility of a patient's family. Few other states provide legal guidance about this.119

IV. The Future of Laws about Death by Neurologic Criteria

Having addressed the history and current status of laws about death by neurologic criteria, we turn to the steps needed to remedy the ambiguities and variabilities governing these determinations.

However, before doing so, it is worth describing the pivotal initiatives the AAN is organizing to assure accuracy in the medical determination of death by neurologic criteria and to reinforce public trust in brain death determinations. Their actions include: (1) developing educational initiatives and credentialing processes for physicians performing brain death determinations; (2) advocating for uniformity and regulatory oversight of institutional brain death policies; and (3) encouraging collaboration between adult and pediatric physicians to formulate a single standard for brain death determination.120

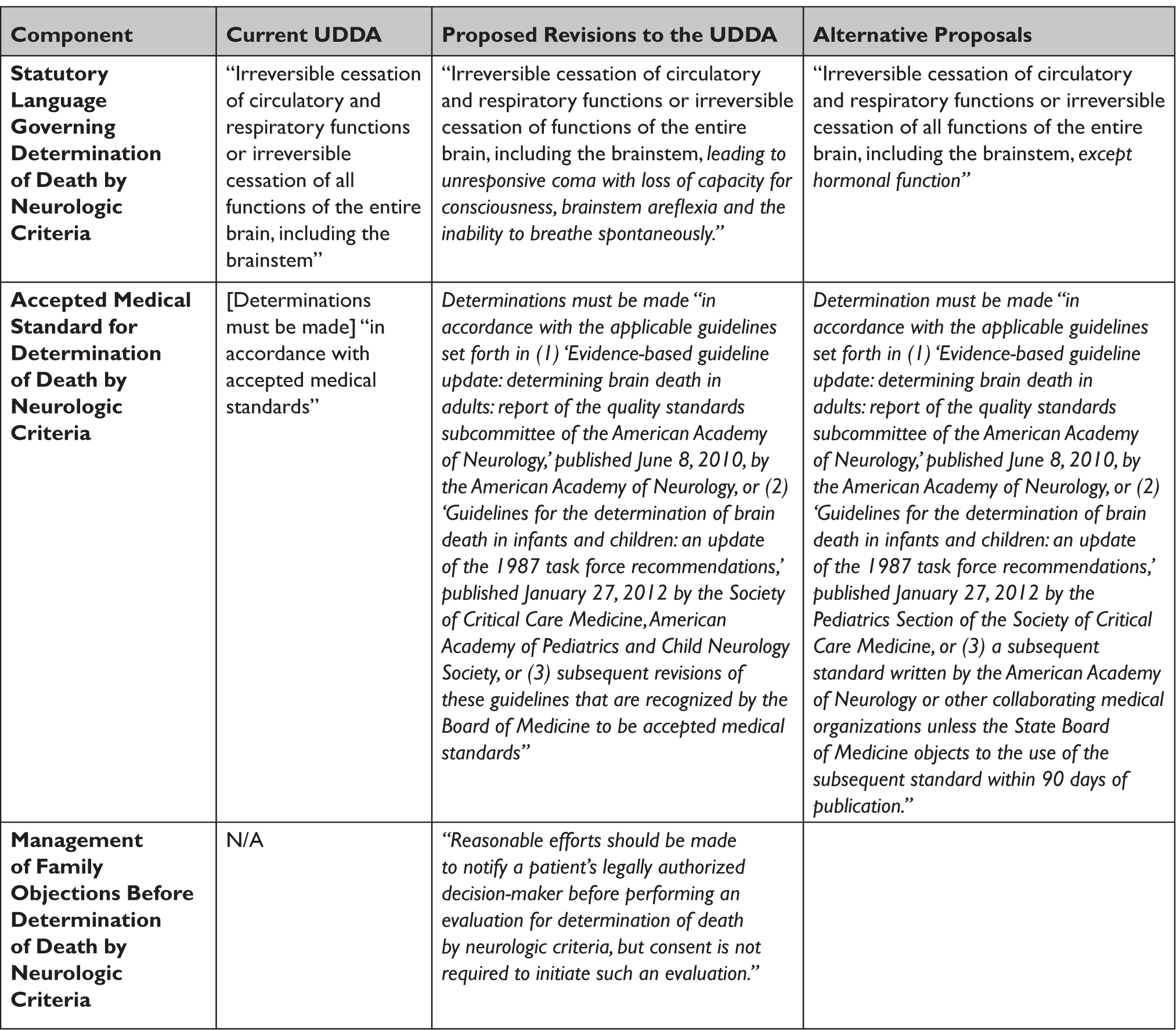

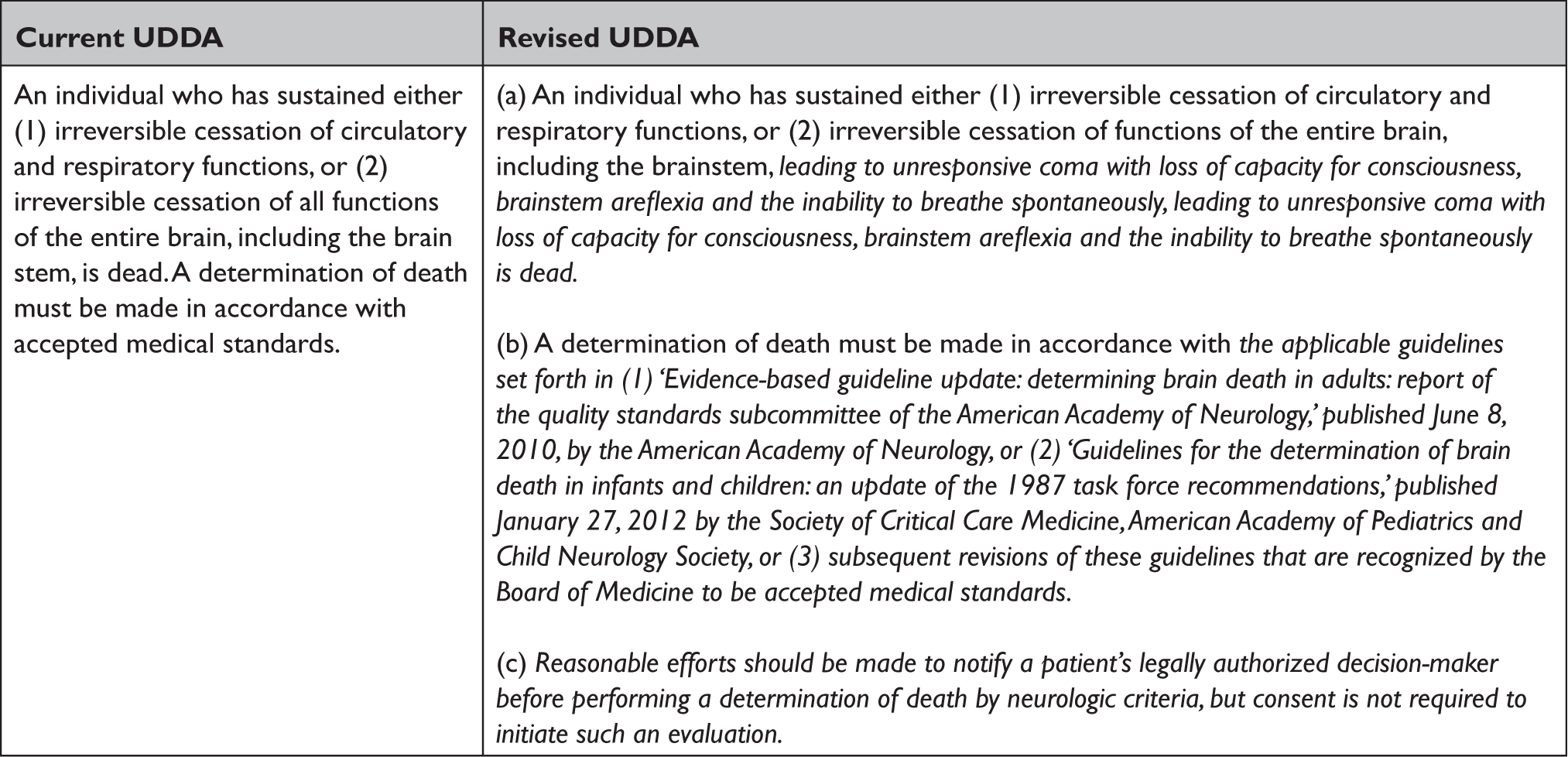

To complement the actions being taken by the medical community, legal experts and policymakers should collaborate to promote clarity and uniformity in state laws on determination of death. This includes (1) addressing the aforementioned variation in the statutory language governing the determination of death; (2) identifying the “accepted medical standards” for making brain death determinations; and (3) providing a clear plan for management of family objections to use of neurologic criteria to declare death. Accomplishing this requires a model for a Revised Uniform Determination of Death Act (RUDDA; see Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Current and Revised UDDA Components

Table 2. Current and Revised UDDA

A. Statutory Language Governing Determination of Death by Neurologic Criteria

There appears to be conflict between the language of the UDDA (which includes the phrase “all functions of the entire brain”) and accepted medical standards (which do not require demonstration of pituitary/hypothalamic dysfunction to declare death by neurologic criteria).121

While accepted medical standards do not measure pituitary or hypothalamic function, multiple studies have demonstrated that these functions persist in 10-91% of people declared dead by neurologic criteria.122 This causes confusion because the UDDA requires that death by neurologic criteria be based on “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem.” In short, the language of the UDDA seems to preclude a declaration of death in a case where pituitary/hypothalamic function persists.123 However, the authors of the UDDA do not appear to have intended the phrase “all functions of the entire brain” to encompass functions of the pituitary gland and hypothalamus; in their 188-page report, they mentioned “coma” 120 times, “brainstem” 22 times, and “apnea” nine times. But not once did the Commission mention any terms to describe pituitary/hypothalamic/hormonal function.”124

Nonetheless, this situation has prompted concern in both the medical and legal communities that the prevailing medical standards do not comport with the legal requirements for death by neurologic criteria.125 The customary interpretive move designed to harmonize the clinical practice with the statutory language is to interpret the phrase “all functions of the entire brain” to refer to all functions of the central nervous system responsible for continued functioning of the “organism as a whole.” While this argument may be conceptually persuasive, it may not be endorsed by a court charged with interpreting the statutory phrase that actually appears in the UDDA: “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain.”126

In our view, the safest way forward is to amend the UDDA. There are two ways to do so. The first, most principled, and most philosophically satisfying way of addressing the problem is to modify the text to clarify which functions matter and why. To be specific, this would involve removing the elusive term “all” and replacing it with “irreversible cessation of functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem, leading to unresponsive coma with loss of capacity for consciousness, brainstem areflexia, and the inability to breathe independently.”

Notably, the authors of the UDDA considered taking this type of nuanced approach by referring to the disappearance of specific physiological functions that are indicative of the irreversible loss of all function of the heart or brain. But they ultimately rejected this approach as too technical.127 In hindsight, though, the ardent debate about the meaning of “all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem,” may demonstrate that a more “technical” approach to the language of the UDDA is now warranted. We embrace this view without scientific or clinical reservation.

Another option to consider would be to modify the statutory criteria for declaring death to refer to “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem, except hormonal function.” This language would clarify the law and bring it in line with medical standards while requiring minimal changes to the UDDA.

Finally, it should be emphasized that, whether or not the language of the UDDA is modified, it is also possible to clarify the meaning of “all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem” by more clearly specifying the medical standard for determination of death by neurologic criteria in the UDDA itself. Doing so would offer additional benefits, as detailed below.

B. Accepted Medical Standard for Determination of Death by Neurologic Criteria

The identity of “accepted medical standards” should be clearly stated in law and not be left to case-by-case trial court rulings. Furthermore, adherence to this standard must be required for all medical determinations of death by neurologic criteria and all legal discussions of death by neurologic criteria.

Medical stakeholders in brain death determination accept the 2010 AAN and 2011 SCCM/AAP/CNS standard for determination of death by neurologic criteria.128 Legislatures should refer explicitly to these standards by name in statutes about death. In this respect, Nevada's revised statute serves as a model for other states because it specifically refers to these standards.129 It specifies that a declaration of brain death must be made:

in accordance with the applicable guidelines set forth in: 1) ‘Evidence-based guideline update: determining brain death in adults: report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology,’ published June 8, 2010, by the American Academy of Neurology, or any subsequent revisions approved by the American Academy of Neurology or its successor organization; or 2) ‘Guidelines for the determination of brain death in infants and children: an update of the 1987 task force recommendations,’ published January 27, 2012 by the Pediatric Section of the Society of Critical Care Medicine, or any subsequent revisions approved by the Pediatric Section of the Society of Critical Care Medicine or its successor organization.130

Aside from embracing these two existing standards as the “accepted medical standards,” the Nevada legislature also recognized that some mechanism is needed to allow the legal criteria for death to evolve in tandem with changes in the medical standard. In order to accomplish this, the legislature specifically referenced future versions of the two standards. It is worth noting that this approach (automatically embracing future changes to current standards adopted by the professional organizations, without any further legislative action) is likely to be invalidated by some state supreme courts as an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power to a private organization.131

In consideration of this concern, we recommend that state legislatures consider two alternative approaches. One is explicit delegation of authority to an administrative agency to review and update the medical practice standards. Under this “agency delegation” approach, the legislature would explicitly adopt the current standards by statute (as Nevada did) but would delegate the authority to update the standards to a state administrative agency, such as the Board of Medicine, within reasonable constraints.132 This approach avoids the approach of giving a binding effect in advance to a document that does not exist with content that cannot be known until the designated organizations act. Accordingly, a statute adopting this agency delegation approach would state that a declaration of brain death must be made:

in accordance with the applicable guidelines set forth in: (1) ‘Evidence-based guideline update: determining brain death in adults: report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology,’ published June 8, 2010, by the American Academy of Neurology, or (2) ‘Guidelines for the determination of brain death in infants and children: an update of the 1987 task force recommendations,’ published January 27, 2012 by the Society of Critical Care Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics and Child Neurology Society, or (3) subsequent revisions of these guidelines that are recognized by the Board of Medicine to be accepted medical standards.

This approach represents a commonplace delegation of regulatory authority to an administrative agency obligated to follow statutorily required lawmaking procedures and norms. Moreover, the legislature itself will have ample opportunity to substitute its own judgment for that of the agency if it chooses to do so. We endorse this approach.

If the legislature were unwilling to delegate this authority to the Board of Medicine (or an equivalent regulatory agency), a more cumbersome approach could be used. Under what we will call the “notice and opportunity for legislative review” approach, the legislature would reserve the opportunity to review successor versions of the medical practice standards before they take effect. Using this approach, the state legislature would: (1) adopt the current versions of the standards, as did Nevada; (2) require the Board of Medical Practice (or an equivalent state administrative agency) to monitor actions by the AAN and other collaborating medical organizations; (3) require that agency to notify the appropriate leaders of the legislative body whenever the standards have been updated by the AAN and their collaborating organizations; and (4) specifically declare that the revised standards will take effect within 90 days of such notice unless the legislature takes contrary action before the expiration of that period. Whether this “notice and opportunity to review” approach would be upheld by state courts remains to be seen, but it is more likely to be upheld than the Nevada approach.133

C. Management of Family Objections before Determination of Death by Neurologic Criteria

The UDDA is silent regarding the need for consent prior to determination of brain death. But leaving this issue up to clinicians and the courts has led to considerable confusion and variability. To provide certainty and clarity, a few states have addressed notification and consent for brain death testing.

Nevada's new statute states that “a determination of death … is a clinical decision that does not require the consent of the person's authorized representative or the family member with the authority to consent or withhold consent.”134 However, the statute says nothing about whether families should be notified of the intent to conduct a brain death determination. In New York, by contrast, the guidelines for determining brain death require that diligent efforts be made to notify family members about performance of a determination of brain death while stating explicitly that consent is not required for a determination of brain death.135

We agree with the New York approach. Even if families have no veto over the decision to perform a death determination, respect for the feelings of family members requires that they be informed of the impending determination of death. Accordingly, we recommend amending the UDDA to state that “reasonable efforts should be made to notify a patient's legally authorized decision-maker before performing a determination of death by neurologic criteria, but consent is not required to initiate such an evaluation.” This formulation emphasizes that family awareness about performance of a brain death determination is important, but that practitioners do not need permission to perform an assessment for the purpose of determining whether a person is alive or dead.

D. Management of Religious Objections to Declaration of Death by Neurologic Criteria

The UDDA does not address issues relating to objections to the use of neurologic criteria to declare death or to the withdrawal of organ support after a determination of brain death, although the Commission acknowledged that hospitals are free to accommodate family objections.136 Despite the increasing frequency of family objections both to the use of neurologic criteria to declare death and to the withdrawal of organ support, most of which are based on religious beliefs, there is a lack of definitive legal guidance about how to handle these objections. At present, there is substantial variation in state statutes and judicial rulings concerning management of these objections, resulting in variable and unpredictable decisions by hospital administrators, hospital ethics committees, and physicians.137

How much accommodation of these objections should be permissible by law? There are four options. First, there is the approach taken in New Jersey, which prohibits providers from declaring death until irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory function has occurred if a patient has religious or moral beliefs that death by neurologic criteria is not death.138 Second, there is the approach taken in California and New York, which does not impact the occurrence or time of death, yet encourages providers to “reasonably accommodate” religious objections.139 Third, there is the approach taken in Illinois, where providers are told that religious and moral beliefs should be taken into consideration when determining time of death.140 Lastly, states could take an approach not currently explicitly stated anywhere in the country, and declare that religious and moral beliefs should not be taken into consideration either when determining occur-rence or time of death or when determining whether to continue organ support.

Ideally, legislatures in the 50 states would embrace a common position on managing religious objections to brain death determinations, thereby standardizing the process of declaring death throughout the United States. However, even in the absence of national uniformity, legal clarity is of paramount importance. One possible framework for a consensus-building process is to convene a representative group of religious leaders, health care professionals, bioethicists, health lawyers, and legislators, perhaps under the umbrella of an interdisciplinary organization that operates at the intersection of these professions, such as the Hastings Center.

Such a national expert body might be charged with formulating clear guidance for practitioners on their legal and ethical obligations in the setting of religious objections to brain death with respect to (1) whether or not a brain death determination should be performed, (2) which (if any) treatments should be continued after brain death determination and how long they should be continued, (3) whether the time of death should be recorded as the time the death by neurologic criteria determination was completed or the time of cardiopulmonary death, and (4) who is responsible to pay for treatment rendered after death by neurologic criteria is established.Reference Flamm, Smith, Mayer, Johnson, Kahn, Luce, Bosek, Anderson, Vernaglia, Morrigan, Bard, Smith, Flamm, Berner, Gaeta, Olick, Braun and Potash141

In the absence of a uniform national position on accommodation of religious objections in brain death determinations, at a minimum, each state must take steps to provide clear legal guidance on each of four aforementioned questions and address the inevitable conflicts that will arise when families seek to move a patient to a more accommodating state. Notably, this unfolding process will occur in the context of ongoing constitutional litigation.142

V. Conclusion

Death must be determined in a standardized manner, both medically and legally. In order to maintain public trust in the determination of death by neurologic criteria; the medical community and legal policymakers must work to rectify variability in death determination. The AAN is leading a coalition of medical organizations to carry out a comprehensive strategy to address this problem. Legislatures must do their part by revising the UDDA as recommended in this article.