About This Column

James G. Hodge, Jr., J.D., LL.M., serves as the section editor for Public Health and the Law. He is the Professor of Public Health Law and Ethics at the Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law and Director of the Center for Public Health Law and Policy (CPHLP) at Arizona State University.

In two prior parts previously published in the Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics, the straight-forward concept of “constitutional cohesion” is introduced and explained.Reference Hodge and Hodge1 Succinctly stated, though often viewed and analyzed separately, structural-and rights-based constitutional norms are highly interdependent. As Professor Akhil Reed Amar noted in 1998, “[s]tructure and rights [are] tightly intertwined in the original Constitution and in the original Bill [of Rights], which themselves [are] tightly intertwined.”Reference Amar2 Thus, structural principles of federalism and separation of powers have similar constitutional purposes as due process and other individual rights. They are all designed to limit governmental vices (e.g., oppression, overreaching, malfeasance, tyranny).Reference Brown3

The theory of constitutional cohesion is not ground-breaking,Reference Black4 but its modern applicationsReference Varol5 may be essential to counter significant public health law and policy challenges.Reference Hodge6 A driving premise is that structural principles or individual rights can be wielded effectively and interchangeably to improve health. Conversely, constitutional cohesion may defeat or compromise public health legal efforts. Multiple state health and safety laws supportive of civil liberties, for example, have been invalidated over decades under the guise of preemption and federalism.Reference Schapiro7

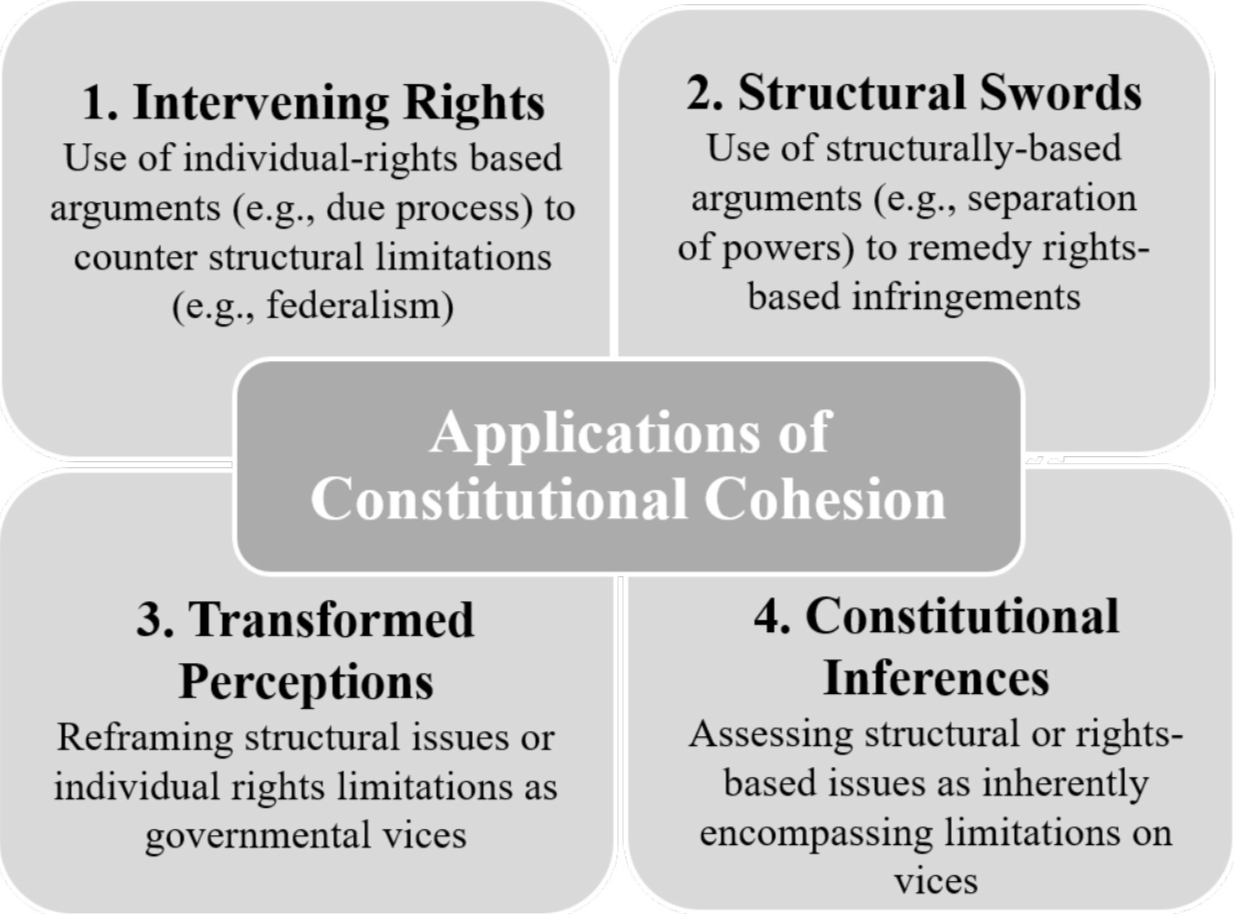

Despite the risks of adverse consequences, applications of constitutional cohesion in promoting the public's health are an acceptable gamble against a bevy of legal and political affronts. As per Figure 1, four key applications emerge.

Figure 1

The first three of these applications reflect fairly-settled, albeit under-utilized, law. The latter application, Constitutional Inferences, presents more amorphous opportunities to interject constitutional norms into modern laws. It presupposes constitutional limits for any identified governmental vice, even if the limits are not explicitly framed in rights-based protections or structural principles. Consequently, unstated rights flow not only from express language in the Bill of Rights, but also from the very structure of the Constitution itself.

Constitutional interpretations against governmental infringements may take many forms via this application. As examined below, new rights may emerge from cobbled interpretations of a penumbra of rights (a.k.a. “auxiliary righting”) or expanded conceptions of existing rights (a.k.a. “creative righting”). Less well explored is the distinct, ethereal concept of what we identify here as “ghost righting,” or the generation of rights-based interventions arising from or embedded within structural foundations or unstated Constitutional norms. At a minimum, ghost righting presents another novel way to generate rights-based objections to substantial legal threats to communal health. At its apex, however, the concept may help usher in a new constitutional right to public health.

Crafting Rights-Based Norms from Existing or Expanded Constitutional Principles

That governmental vices may be addressed through individual rights not clearly enunciated in Constitutional text is fairly settled and non-controversial. Prominent examples include individual rights to privacy and rights to bear arms crafted by the U.S. Supreme Court to combat what it identifies as governmental vices.

Auxiliary Rights

While privacy rights evolved from initial conceptions dating back to the late 19th century,Reference Warren and Brandeis8 the Supreme Court did not explicitly acknowledge a standalone “right to privacy” until 1965 in Griswold v. Connecticut,9 when it struck down a state law prohibiting birth control. As Justice Douglas (writing for the majority) explained, privacy rights are not explicitly framed in the Constitution. Rather, they are undergirded via the 1 st, 3rd,, 4th, 5th, 9th, and 14th Amendments which collectively provide “penumbras” from which “zones of privacy” originate.10 In this way, the Court examined the Constitution as a cohesive whole instead of a mere collection of principles, much like the Framers, to craft auxiliary privacy rights otherwise unstated textually. Modern privacy rights buttress reproductive and other freedoms11 with significant corollary public health benefits.

Creative Righting

In 2008 the Court's interpretation of the right to bear arms in District of Columbia v. Heller 12 led to a substantial reassessment of the 2nd Amendment. Justice Scalia bifurcates the Amendment's (1) prefatory clause (“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the Security of a free State”) from the (2) operative clause (“the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed”). Dismissing the former clause as nonessential (despite established precedence13), he argues that the operative language creates a right to self-defense at home with a lawful firearm. In dissent, Justice John Paul Stevens suggests the “Court appear[s] to have fashioned [its interpretation] out of whole cloth.”14 Later, in 2018, retired Justice Stevens calls for a complete repeal of the 2nd Amendment given the escalation of gun-related deaths in the U.S.Reference Stevens15

Ghost Righting

This concept exceeds the prior two examples of Constitutional inference. Like spirits themselves, its manifestations exist but are rarely seen. Perhaps the most notable example extends from the Court's multi-faceted recognition of the right to travel (or prohibit travel among foreigners as per ongoing litigation related to President Trump's proposed “Muslim” ban).Reference Liptak and Shear16 Like privacy, nowhere in the language of the Constitution is there explicit reference to rights to travel. In Saenz v. Roe (1999), however, the Court explains how the right has three components, two of which have textual sources.17 First, U.S. citizens have a right “to be treated as a welcome visitor … when temporarily present” in another state under Article IV's privileges and immunities clause. Second, they have a right to be treated like other citizens who are permanent state residents pursuant to the 14th Amendment's privileges and immunities clause.

The Court also recognizes that citizens have rights to ingress and egress across state borders. Yet, it does not identify a specific Constitutional source for this “elusive” component,18 concluding instead that it “may have been ‘conceived from the beginning to be a necessary concomitant of the stronger Union the Constitution created.”19 In Attorney General of New York v. Soto-Lopez, Justice Brennan noted in dicta the right to ingress and egress is “inferred from the federal structure of government adopted by our Constitution.”20 Such acknowledgments evince a clear case of “ghost righting:” unwritten individual rights arising from the very structure of the Constitution, with public health implications. Rights to ingress and egress necessitate balancing individual and communal interests across diverse policies related to sex offender registries, juvenile curfews, drug and gun free exclusion zones, and emergency evacuations/relocations.Reference Eaton, Gee and Wilhelm21

Crafting a Ghost Right to Public Health

Whether applied facets of constitutional cohesion strike at the heart or approach the edge of governmental acts or omissions, delineating and eliminating vices that encumber population health are consummate goals at every level of government. Among the highest functions of government is the need to protect public health and safety on which so many other freedoms rely. Failing to promote basic public health services for all is more than a health justice or equity issue. It is a governmental vice. And, as with any vice, there must be a constitutional remedy even if it is unstated or unidentified to date.

The shadow of a ghost right to public health manifests in the Court's recognition of governmental obligations to protect the health of specific populations, particularly prisoners and wards of the state. Denying medical services to prisoners is an affront to human dignity22 in violation of the 8 th Amendment.23 Consistent with substantive liberty interests, government must also provide appropriate medical care for persons involuntarily committed via quarantine, isolation, or for mental health purposes.24

Of course the Court has historically refused to interpret the U.S. Constitution as including anything that approaches a positive right to health for all. In Maher v. Roe (1977),25 it held that “[t]he Constitution imposes no obligation on the States to pay… any of the medical expenses of indigents.” Later the Court found the Due Process Clauses “generally confer no affirmative right to governmental aid” for individuals26 or third parties.27 Principles of equal protection may support nondiscriminatory access to specific governmental medical services,Reference Stacy28 but do not require government to fund services in the first place.29 In 2013, the Court flatly rejected a statutory basis for American courts to hear claims against parties alleged to have committed human rights abuses (including violations of rights to health) abroad.30 Later, in 2018, it would deny access to courts for similar suits against foreign corporations.31

Amidst this jurisprudence “black hole,”Reference Wing32 proposals have regularly emerged for federal Constitutional or Congressional recognition of “rights to health.”33 Multiple states recognize health rights in some way through their state constitutions.Reference Leonard34 New York's constitution provides that “[t]he protection and promotion of the health of the inhabitants of the state are matters of public concern.”35 Hawaii's constitution reads “[t]he State shall provide for the protection and promotion of the public health.”36 Montana's constitution states that “[a] ll persons…have certain inalienable rights [including] to…[seek] their… health…in all lawful ways.”37 Though purposeful, each of these provisions falls short of enunciating an affirmative right to public health.Reference Leonard38 Some activist groups have therefore proposed sets of state constitutional amendments to solidify positive rights to health care.Reference Rüegg39 The effects of these constitutional platitudes on public health promotion are not well known. One 2015 study links stronger state right to health provisions and subsequent decreases in infant mortality.Reference Matsuura40

Absence of rights and protections from constitutional parlance does not always mean they do not exist. As Akhil Reed Amar posits, “[i]f rights can be unenumerated, is it possible to imagine entire constitutional amendments that are unwritten?”Reference Amar41 Wendy Parmet and others purport that the Framers' expectation that government protect the public's health obviated any need for constitutional mandates.Reference Parmet42 This may help explain the absence of affirmative Constitutional language effectuating public health protections. However, it does not resolve the resulting vice stemming from governmental failures to provide for even base levels of public health services. Crafting a purposeful right to public health starts with the recognition of this vice. Principles of constitutional cohesion suggest the recognition of a vice lends to structural or rights-based objections to counter it. Consistent with the theory of ghost righting, it follows that a positive right to public health assuredly exists, waiting for an opportunity to appear to advance the health of all Americans.

Crafting a purposeful right to public health starts with the recognition of this vice. Principles of constitutional cohesion suggest the recognition of a vice lends to structural or rights-based objections to counter it. Consistent with the theory of ghost righting, it follows that a positive right to public health assuredly exists, waiting for an opportunity to appear to advance the health of all Americans.