Introduction

On August 1, 2018, a ninety-five-page document went viral on social media in China and immediately garnered domestic and international attention.Footnote 1 Its authors accused a high-ranking Chinese Buddhist monk named Xuecheng of sexual harassment (xing saorao 性騷擾) and assault (xingqin 性侵) of multiple ordained Buddhist nuns, of approving illegal construction of new buildings in his monastery without permits from the city, and of embezzling monastery funds. The accused was the abbot of the Longquan 龍泉 monastery, a Chinese Buddhist monastery located on the outskirts of Beijing. In just over a decade, this monastery had earned an international reputation for recruiting highly educated intellectuals from prestigious academic institutions in China to become ordained Buddhist monks and nuns. Its successful use of social media, advanced technology, and artificial intelligence also helped establish its public identity as a prominent Buddhist institution in contemporary China.Footnote 2 The two authors who put forward these accusations, monks Xianqi 賢啟 and Xianjia 賢佳, had both served on the administrative team at the monastery. In addition to being the abbot of this leading Chinese Buddhist monastery, the accused was at the time also the president of the Buddhist Association of China (Zhongguo fojiao xiehui 中國佛教協會), the highest state-recognized Buddhist organization overseeing national Buddhist affairs in China. Current discussions on this case center on its connection with recent advancements in the #MeToo movement in China,Footnote 3 which peaked a few weeks earlier, in summer 2018, when a series of allegations of sexual harassment and assault were made against high-profile scholars, well-known activists from nongovernmental organizations, and influential journalists. Circumscribing this case exclusively within the context of the sexual harassment movement, however, obscures its significance for the broader field of legal interplay between religion and the state in China.

Negotiation over the jurisdictional boundary between the state and religious establishments is central in defining the legal relationship between the two. One thesis considered the Buddhist clergy's submission to the jurisdictional governance of the state a distinctive feature in the Chinese transformation of Buddhism. Kenneth Ch'en, an influential proponent of this thesis, argued that the Buddhist clergy in China betrayed Indian tradition in the process of taking root in Chinese society.Footnote 4 Evidence of this betrayal was the Chinese Buddhist clergy's abandonment of the Indian tradition requiring royal kings to pay homage to ordained Buddhists. The tradition of royal rulers paying homage to ordained Buddhists, according to Anthony C. Yu, illustrates the Indian Buddhist monastic community's “essential independence” from the state.Footnote 5 Yet Yu challenges the validity of this thesis in terms of the clergy's jurisdictional submission to the state. He argues that even if the Buddhist clergy “might have indeed come to terms by and large with the supremacy of state,” some individual Buddhists were exceptions. One was the pilgrim monk Xuanzang 玄奘 (602–664), who willingly risked violating the state border-control law to travel to India when border crossing was prohibited in early Tang.Footnote 6 To Yu, such incriminating actions by individual Buddhists indicates a belief in “a demand, a summons, and a law that were higher than any norm or form of authority sanctioned” by the individual's native traditions.

Another thesis highlights the contrast between harsh state controls on religion in law and lax enforcement in practice. Writing in 1968, Holmes Welch saw this contrast in the late Qing, during which extremely harsh state laws on Buddhism were rarely implemented in legal practice, which left ordained Buddhists in a legal vacuum.Footnote 7 Citing missionary reports of ordained Buddhist offenders who had been spared from punishment,Footnote 8 Welch suggested that a criminal can escape from prosecution by entering the Buddhist order, a fantasy most elaborately entertained in classical Chinese literature such as the fourteenth-century novel Water Margin (Shuihu zhuan 水滸傳), where the murderer Lu Da 鲁達 escapes from prosecution by entering a Buddhist monastery to become an ordained Buddhist monk named Zhishen 智深. He presented two reasons for this laxity in the enforcement of state laws on ordained Buddhist offenders:Footnote 9 (1) law enforcement officials might be less antagonistic to Buddhism, and (2) the legal authority of law enforcement offices staffed by Buddhist monastic officials was powerless and weak. Nevertheless, Welch believed that this contrast between harsh law and slack implementation of law operated in favor of the state. This flexibility allowed the state to show benevolence toward ordained Buddhist offenders but also reserve the right to lawfully prosecute any monk who might become “even slightly involved in something heretical or subversive” because the “district magistrate could consult the code and strike him down with at least twenty dire regulations that he had been breaking (like most other monks) throughout his career.”Footnote 10

The case in 2018 provides a unique opportunity to examine the extent to which theories on the state-religion relationship in late imperial times apply to contemporary China.Footnote 11 For an ordained Buddhist monk, having sexual intercourse under any circumstance violates one of the four fundamental precepts of “defeat” (Sanskrit pārājika) in the Buddhist canon law, and in theory he should be expelled from the Buddhist monastic community.Footnote 12 In the contemporary context, an ordained Buddhist monk who had sexually harassed or assaulted others also violates the state law of China. As such, both the state and the Buddhist clergy can claim jurisdiction over anyone accused of these allegations. The actual handling of such allegations would therefore illustrate how the tension over the jurisdictional boundary between the Buddhist establishment and the state plays out in legal practice in contemporary China. Such an examination is feasible because the legal authorities handling this case reached an initial conclusion of their investigation within a month of this revelation to the public and made certain information regarding legal procedures publicly available.

Four institutional powers are at the center of the interplay between the state and the Buddhist establishment in the adjudication of Xuecheng: his hosting monastery, the state court, the police, the Buddhist Association of China staffed by state-approved monastic officials, and the State Administration for Religious Affairs staffed by state-appointed lay officials. In this article, I trace the procedures and relationships operating today in Xuecheng's case to the Republican era and before. I do so because the state governance of Buddhism in contemporary China closely parallels governance of Buddhism in imperial and Republican China. Indeed, Xuecheng's case parallels the adjudication of clerical offenses and offenders in imperial China. Elsewhere, I have shown that the state and Buddhist clergy collaboratively established a tripartite legal system with the introduction of hybrid laws and courts beginning in the fourth century to replace dichotomous lay and monastic courts and laws.Footnote 13 I offer the analysis in this article to further understanding of how the legacy of the state's governance of Buddhism and the efficacy of the Buddhist clergy's jurisdictional self-governance in imperial and Republican China continue to prevail in contemporary China. The combination of ordained Buddhists’ collective denunciation of personal clerical privileges in 1929 and the subsequent loss of the opportunity to legalize the Buddhist Association of China's jurisdictional power over internal disputes within the Buddhist clergy in the association's charter of rules for its members in 1936 have long shaped the legal governance of Buddhism in modern and contemporary China. Consequently, the Buddhist Association of China waited until the 1990s to demonstrate a renewed interest in seeking limited jurisdictional power for self-governance, power that it had lost in the Republican era. Despite the substantial changes that have taken place in China's legal system over the last century or more, the state not only continues to use a third-party intermediary for adjudicating Buddhist clerical offenders, but it exercises jurisdictionally harsh, yet practically lax, legal governance over Buddhism in contemporary China, much as Welch described it doing in the late Qing.

The Allegations

The ninety-five-page document begins with a summary of the allegations, followed by a petition for a state-led investigation, and ends with five attachments containing supporting evidence. Sexual misconduct by an ordained Chinese Buddhist monk violates both the Buddhist monastic law and state law, and in what follows I present the chronology of the allegations of sexual misconduct as they were set forth in the document.

The document reports that at least three nuns were victims. Nun A reported verbal sexual harassment via text message from the accused, but no sexual intercourse. Nun A was born in 1984 in Guangxi Province. On April 25, 2014, she became a resident volunteer at Longquan monastery. On October 2, 2015, she became a lay steward (Sanskrit kalpikāraka, Chinese jingren 淨人) at Longquan monastery's Jile 極樂 nunnery, a subordinate nunnery in Fujian Province. She received her novice nun ordination on March 16, 2016, at her hosting nunnery. Six months later, on October 16, 2016, she and seventy-seven fellow novice nuns from the same nunnery received full-nun ordination at the Zhongde 種德 chan monastery in Fujian province. On December 21, 2017, she and a fellow nun, Nun B, from the same nunnery were selected to study English in Beijing for three months before traveling abroad to work on a project to expand Longquan monastery's influence globally. They arrived in Beijing on December 25, 2017, and stayed at the Rixin Dharma Center (Rixin jingshen 日新精舍). A text message exchange began between Nun A and the accused on December 26, 2017, and lasted until she terminated it on January 11, 2018. Her reflection and the retrieved text messages with the accused indicate that in those two weeks, the accused forcibly demanded sexual favors ranging from touching to sexual intercourse.

Nun A initially tried to seek help from fellow Buddhists in order to resolve this issue in-house within the Buddhist clergy. She contacted monk Xianqi, one of the two authors of the document, and asked for assistance to escape from the Dharma Center in Beijing. On February 14, 2018, after fleeing, she wrote a reflection of the sexual harassment she had just experienced. Monk Xianqi, whom she approached for help, reported that he sought an internal solution within Longquan monastery's administration. On February 17, 2018, he circulated a written petition among the administrators at Longquan monastery, with the aim of helping the accused recognize his misconduct and confess. But this failed.

Two more allegations of sexual harassment against Xuecheng surfaced four months later. On June 25, 2018, Buddhist nun, Nun C, who was identified as a sexual assault victim of the accused, revealed her experience to monk Xianjia, the other author of the document, and several other monk administrators at Longquan monastery. Nun C also reported witnessing the accused sexually assault another unidentified nun, a likely reference to Nun B, who was mentioned in the attached text message dated January 7, 2018.

After failing to obtain a resolution within the monastery, the victims and their supporters sought intervention from outside the monastery. On June 29, 2018, Nun C, accompanied by Xianqi and three other monks, attempted to file a complaint of sexual assault against the accused at the local police station in Haidian district. On August 1, 2018, about a month later, the ninety-five-page document appeared on social media and went viral. On the same day, Longquan monastery issued an official statement denying all charges against its abbot and accused the two monks who had accused Xuecheng of making false accusations and forging evidence.Footnote 14 While discussion on this case swirled both online and offline, these monks and nuns sent a copy of the document to the State Administration for Religious Affairs in Beijing, a government office overseeing national religious affairs that is staffed by state-appointed lay officials. On August 2, 2018, this office officially announced that it had received the document and had begun an investigation into it.

How are sexual offenses regulated in state law in contemporary China? What is the role of the State Administration for Religious Affairs and why was it chosen to investigate this case? And what is the role of the Buddhist Association of China and its legal authority over religious matters? These questions guide the discussion that follows. Before introducing and assessing the legal procedures used in adjudicating this case, I will describe the legal context of sexual harassment in contemporary China, the Buddhist Association of China, and the State Administration for Religious Affairs.

The Legal Context in Contemporary China

In contemporary China, sexual harassment is considered a civil offense. This term first appeared in the Law of the People's Republic of China on the Protection of Women's Rights and Interests (Zhonghua renmin gongheguo funü quanyi baozhang fa 中華人民共和國婦女權益保障法), revised and passed on August 28, 2005. Article 40 from this law prohibits sexual harassment against women and provides victims the right to submit a complaint to their employer or other relevant offices. Four years later, on May 21, 2009, a proposal from the city of Beijing on implementing the law there provided a more detailed description of sexual harassment and recommended more specific venues for dealing with it.Footnote 15 Article 38 in this proposal prohibits anyone from sexually harassing women verbally, including through texts, images, or electronic information, or by making bodily contact. It also provides victims with two options: they can either make an official complaint to their employer, the employer of the victimizer, or the All-China Women's Federation (Funü lianhehui 婦女聯合會) in the city and other relevant offices, or initiate a lawsuit in court. Most recently, Draft of the Civil Code: Section on Personality Rights (Minfadian rengequan bian cao'an 民法典人格权编草案) submitted to the national meeting of the National People's Congress on August 27, 2018, explicitly defines sexual harassment as verbal or physical sexual advances against the victim's will and enables victims to file civil lawsuits against their victimizers.

The legal options available to nun victims of sexual crimes, however, are hindered by extra restrictions found in Buddhist monastic law. First of all, Buddhist monastic law prohibits nun victims of violent assault from filing lawsuits in lay court. Instead, it encourages ordained Buddhists to resolve internal offenses involving only ordained members of the Buddhist clergy within the institution. This rule is found in the Mahīśāsaka Vinaya, or Buddhist monastic law transmitted from the Mahīśāsaka tradition. In the Chinese translation of this legal text, the Wufen lü, in the section discussing a rule whose violation requires a formal meeting of the entire order,Footnote 16 nuns who fall victim to violent assault are prohibited from reporting the crime to the lay court. Instead, they should seek help and support from family members or peers within the Buddhist clergy, including parents, relatives, fellow Buddhist monks and nuns, or lay Buddhist men and women. Refusing to provide needed support in such cases, while being able to and after being contacted for this purpose, would constitute a light offense of wrongdoing, the slightest offense in the Buddhist monastic legal system that would call for a self-confession. When reporting the assault to these supporters and guardians, the nun victim should inform them of the identity of the assaulter and ask them to chastise the assaulter for her. If the nun victim were to report the crime in the lay court, the moment she completed a round trip to court she would commit an offense entailing a formal meeting of the order for ordained Buddhist nuns. Were a probationary nun or a novice nun to do so, it would constitute a light offense of wrongdoing. In the Buddhist legal system, a novice nun must spend around two years in probation before requesting to be fully ordained.

This restriction in the Mahīśāsaka Vinaya is not insignificant. While the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya had been predominately influential among Chinese Buddhists in guiding their ordination ceremonies and regular study of the Buddhist monastic code, Mahīśāsaka Vinaya and the Buddhist monastic code from other traditions (Sarvāstivāda, Mahāsāṃghika, and Mūlasarvāstivāda) had all been circulated and used by the Buddhist monastic community in China.Footnote 17 Buddhists in China today still consult the non-dominate Vinaya texts such as the Mahīśāsaka Vinaya. Indeed, the co-authors of the ninety-five-page report cited articles from both the Mahīśāsaka Vinaya and the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya to support their accusations of administrative and financial misconduct against the abbot.Footnote 18 They also cited various historical and contemporary Buddhist monk writers to analyze why it is fundamentally wrong for ordained Buddhists to have sex.

The available options of legal venues for nun victims is further complicated by the chaotic distribution of jurisdictional authority over ordained Buddhists among different government and religious organs. Apart from the state court and the Buddhist monasteries and nunneries, there were at least two other government and Buddhist organs that could investigate the case under discussion. One is the State Administration for Religious Affairs (Guojia zongjiao ju 國家宗教局). The Ministry of the Interior (Neizheng bu 內政部) was the chief government organ that dealt with religious affairs during the Republican era. After 1949, the State Administration for Religious Affairs replaced the Ministry of the Interior as the primary office for handling religious affairs. The other potential investigator is the Buddhist Association of China, which was established at the beginning of the Republican period and continues to exist autonomously in China and Taiwan to the present day.

One unique feature of the legal governance of Buddhist establishments in China is the differentiation of the Chinese Buddhist monasteries from the Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and those located on the frontiers of Tibet and Xinjiang. From 1929 to 1935, the Ministry of the Interior promulgated regulations for the Chinese, Tibetan, and Mongolian Buddhists, respectively.Footnote 19 In contemporary China, the differentiation between Chinese and non-Chinese Buddhist intuitions has been retained. Moreover, multiple layers of government and religious powers have become involved in the governance of Buddhist affairs. These powers range from the Buddhist Association of China that oversees the Chinese Buddhist establishments and their ordained members,Footnote 20 the State Administration for Religious Affairs that directly oversees the Tibetan Buddhist establishments,Footnote 21 and the regional People's Congress.Footnote 22

State Governance of Buddhism

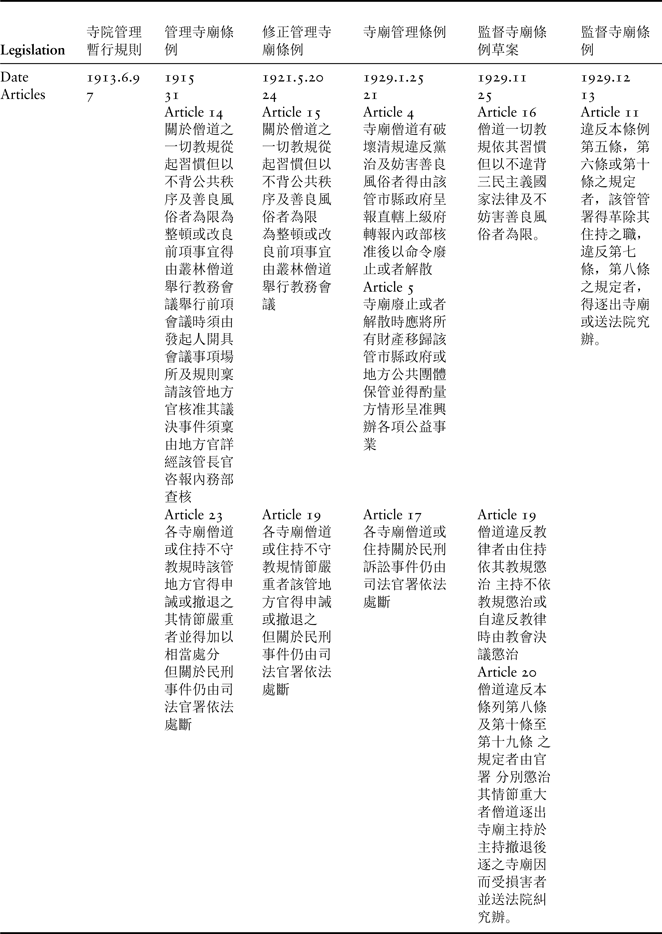

In post-imperial China, the state relied on an increasingly secularized government organ staffed by state-appointed lay officials to manage religious affairs: the abovementioned Ministry of the Interior carried out this duty during the Republican era and, after 1949, an office that is now known as the State Administration for Religious Affairs. From 1913 to 1929, the Beiyang government and the Nationalist government carried out at least six legislative experiments on the management of Buddhist affairs (see the appendix), during which the government revised its policy on how to manage Buddhist institutions six times. Existing scholarship on the history of these government offices and legislation on the management of Buddhist affairs largely center on the articles concerning the handling of Buddhist monastic property.Footnote 23 My discussion below departs from this focus on the Article on monastic property to examine the Article that addresses the treatment of ordained Buddhist offenders in order to understand the historical context for the adjudication of Xuecheng in contemporary China.

Early legislation focused on the handling of Buddhist monastic property and, as in the seven articles of the 1913 law, says nothing about what to do with ordained Buddhist offenders.Footnote 24 Yet articles imposing the state's full jurisdictional control over the Buddhist establishment soon appeared in revisions promulgated in 1915, and retained in the 1921 revision.Footnote 25 The 1915 legislation contains a total of thirty-one articles divided into six sections on general rules, temple property, ordained Buddhists and Daoists of the monastery, temple registration, penalty, and an appendix. Article 14 in the third section permits the Buddhist clergy to hold community meetings to deal with issues concerning the observance of monastic rules by its ordained members. Article 23 in the fifth section on penalty requires the state's judicial offices to investigate ordained Buddhist monks and nuns who had committed civil or criminal offenses, and authorizes local government officials to directly handle Buddhist clerical offenders who had committed offenses against the Buddhist monastic law.Footnote 26 These rules are reiterated in Articles 15 and 19 in the 1921 legislation.

After the Nationalist government replaced the Beiyang government, the new government's revision to this legislation promulgated on January 25, 1929, immediately provoked strong opposition from the Buddhist community. Influential lay Buddhists and eminent monks telegraphed their criticisms on almost every Article to the Nationalist government in Nanjing.Footnote 27 The strongest opposition focused on Article 4 and Article 17. Article 4 permits the government to dismiss a monastery and confiscate its property when an individual monk or nun from the institution is convicted of offenses violating the law of the Buddhist monastic community, the nationalist party, or social customs. Subsequently, the local government or a public organization would be entitled to confiscate or claim the monastic property for various uses.Footnote 28 On March 15, 1929, members from the Buddhist Association of Sichuan Province criticized Article 4 for “destroying Buddhism in the name of protecting it.”Footnote 29 A number of such criticisms also appeared in Buddhist journals.Footnote 30 Five monks and four lay Buddhists on the standing committee of the Buddhist Association of China submitted a joint petition to the Legislative Yuan (Lifa yuan 立法院), a legislature of the Nationalist government that continued to exist in Taiwan today, demanding the latter to consider the comments and suggestions on how to revise the legislation under debate.Footnote 31 In the telegraph to the Nanjing government from the Buddhist Association of Sichuan Province, Buddhists disputed both articles. They refuted Article 4 because no department in the government had been closed when officials working for that unit had committed offenses, and so a Buddhist monastery should not be punished for the offenses committed by its members. Article 17 proposes to have criminal and civil cases involving ordained Buddhists prosecuted by the state. Buddhists also opposed Article 17 by arguing that ordained Buddhist monks and nuns are under the protection and governance of state law, just as all other lay people. For this reason, when an ordained Buddhist commits an offense against state law, they should be prosecuted under state law, just as would an ordinary lay offender. Article 17 thus is an unnecessary repetition of common sense and thus should be deleted.

In the multiple rounds of negotiations between the government and the Buddhist community, the government persistently insisted on the state's jurisdiction over ordained Buddhist offenders when they committed crimes against the state law. An examination of my translation of Articles 23, 19, and 17 from the regulations promulgated in 1915, 1921, and 1929 should suffice to demonstrate this persistence. (The original articles, in Chinese, are provided in the appendix.)

When ordained Buddhists, Daoists, and abbots from all monasteries did not obey their monastic disciplines, the local official of that district should discipline them or expel them. Those whose offenses are serious should receive penalties. When their offenses are related to civil disputes and criminal offenses, they should be adjudicated by the judicial offices in accordance with the law.Footnote 32

When ordained Buddhists, Daoists, and abbots from all monasteries did not obey their monastic disciplines, even if the transgressions were serious, the local official of that district should discipline them or expel them. When their offenses are related to civil disputes and criminal offenses, they should be adjudicated by the judicial offices in accordance with the law.Footnote 33

All civil disputes and criminal offenses of ordained Buddhists and Daoists as well as their abbots should still be prosecuted by the judicial offices in accordance with the law.Footnote 34

While acknowledging the state's full jurisdictional control over ordained Buddhists who had committed civil and criminal offenses, the Buddhist clergy also insisted on the clergy's self-governance of Buddhists who had committed offenses violating the Buddhist monastic law. Buddhists from the Buddhist Association of Sichuan Province demanded the Buddhist institution's jurisdictional independence in adjudicating clerical offenses against Buddhist monastic law or the community bylaw of their hosting monastery,Footnote 35 as well as the jurisdictional independence to consult the Buddhist monastic law to determine the penalty for convicted offenses. If such offenses required punishment beyond confession in accordance with the Buddhist monastic law, the abbot of the offenders’ hosting monastery would have the authority to punish the offenders by expelling them.

The Nationalist government took these protests and suggestions from the Buddhist community seriously. On March 28, 1929, the Executive Yuan (Xingzheng yuan 行政院) required the Ministry of the Interior to discuss the suggestions submitted by General Wang Zhen (1908–1993).Footnote 36 On April 3, it further forwarded the protests from the Buddhist Association of Sichuan Province to the Ministry of the Interior.Footnote 37 In May, the Ministry of the Interior asked the Legislative Yuan to review the legislation promulgated in January.Footnote 38 On May 25, the Nationalist government asked the Legislative Yuan to postpone the implementation of the January 1929 legislation.Footnote 39 In June and July, the Ministry of the Interior sent notice to local governments to pause adjudicating any case related to Buddhist temples before a new legislation was announced. On August 30, the Nationalist government urged the Ministry of the Interior to immediately submit a revised draft of the legislation to the Legislative Yuan,Footnote 40 and made the same request again on September 7Footnote 41 and November 7.Footnote 42

The Nationalist government and the Buddhist clergy apparently had more rounds of negotiation. The Legislative Yuan started by presenting a draft.Footnote 43 In this draft, Article 4 in the January version disappeared and Article 17 in the January version was revised to be split into two Articles: Article 19 and Article 20. Article 19 permits the Buddhist clergy to adjudicate clerical offenses violating only the Buddhist monastic law. Article 20 authorizes the government to prosecute ordained Buddhists who had offended under Article 8 and Articles 10–19 in the draft version, which primarily concern ordination, management of temple property, and observance of state law. In the final version that the Legislative Yuan promulgated on December 7, 1929,Footnote 44 all the articles concerning the treatment of Buddhist clerical offenders had been deleted. Only Article 11 stipulated that abbots who had committed offenses must be sent to the state court for investigation.

This 1929 legislation continued to be used in Taiwan, until it fell out of use in 2006. In mainland China, the Communist Party established its own office to manage religious affairs, which is now known as the State Administration for Religious Affairs.Footnote 45 The systematic legislation on religious affairs in China or such legislation that has become publicly available, however, date only to the 1990s. This legislation focuses on the management of religious practitioners, organizations, and venues. In contemporary China, the most authoritative legislation on the management of religious affairs is the Regulation on Religious Affairs (Zongjiao shiwu tiaoli 宗教事务条例), which was revised and nationally promulgated on February 1, 2018.Footnote 46 This legislation repeatedly states that any individual or organization that has violated the state law of China will face criminal prosecution.

Buddhist Self-Governance

In post-imperial China, accompanying the exclusion of ordained Buddhists in the state-controlled government unit overseeing Buddhist affairs was the establishment of a new Buddhist organization for self-governance: the Buddhist Association of China.Footnote 47 This association oversees national Buddhist affairs among the Buddhist communities following the Chinese Buddhist tradition. It has had a succession of names: Zhongguo fojiao zonghui 中國佛教總會 (General Buddhist Association of China) in 1912; Zhongguo fojiao xuehui 中國佛教學會 (Buddhist Association of China) in 1928; and Zhongguo fojiao hui 中國佛教會 (Buddhist Association of China) in 1929. It was officially registered as an organization in 1937. After 1949, the organization moved to Taiwan, where it remains functioning today. In mainland China, it emerged as Zhongguo fojiao xiehui 中國佛教協會 (Buddhist Association of China) in 1953.Footnote 48

In his study of the Buddhist revival in China, Holmes Welch described the Buddhist Association of China in modern China as “an intermediary” between the monasteries and the official organs exercising jurisdiction over them.Footnote 49 In another book discussing Buddhism during the Mao era, he equated the role of the Buddhist Association of China with that of the monastic officials (sengguan 僧官) in imperial China.Footnote 50 This reading now seems only partially tenable.

The Buddhist Association of China showed little interest in seeking jurisdiction over ordained Buddhists. This lack of interest in jurisdictional autonomy is clearly reflected in the historical evolution of how its members define their legal status in the charter of this association. The charter comprises of rules established for members of the association. In 1917, the Tibetan Buddhist monk Lcang skya Blo bzang dpal ldan bstan pa'i sgron me (1890–1957) and the Chinese Buddhist monk Qinghai清海 revised the Charter of the General Buddhist Association of China (Zhonghua fojiao zonghui zhangcheng 中華佛教總會章程) as the Charter of the Buddhist Association of China (Zhonghua fojiao hui zhangcheng 中華佛教會章程) with twenty-three articles.Footnote 51 Article 11 states that ordained Buddhist monk and nun members who behave in accordance with state law are under equal protection of state law. Article 8 encourages monk and nun members to seek mediation from the local government when they are involved in disputes with other ordained Buddhists or with the laity. When such mediation with the local government fails, they are encouraged to seek mediation with the Buddhist Association of China. In the later revisions of the charter, the Buddhist Association of China no longer functions as an intermediary for adjudicating disputes involving ordained Buddhists. In 1935, the charter was revised at least twice. The first draft revision contained twenty-nine articles.Footnote 52 The final version was approved on July 18, 1935, with a total of thirty-two articles.Footnote 53

In 1936, the Buddhist Association of China was offered an opportunity to assume more jurisdictional control over ordained Buddhist monks and nuns. That year, increasing numbers of disputes between ordained Buddhist monks and nuns motivated the Central Department for Military Training of the Nationalist Party of China (Guomingdang zhongyang minxunbu 國民黨中央民訓部) to invite the Buddhist Association of China to become more involved in the legal governance of the Buddhist clergy. The significantly expanded draft charter, with a total of seventy articles,Footnote 54 proposed that the Buddhist Association of China function as an adjudicator for internal disputes between different Buddhist institutions as well as those between ordained Buddhist monks and nuns. This recommendation is reflected in multiple articles in this expanded charter. For example, Article 8 specifies that the duties of the Buddhist Association of China include “mediating all disputes among Buddhist monasteries and nunneries, as well as those among ordained Buddhist monks and nuns.” Article 25 specifies that one right of the ordained Buddhist members of this association is to “seek mediation from this Association when one has disputes with monks and nuns from one's hosting monastery or nunnery or with those from other monasteries and nunneries.” Article 25 also offers assistance to member Buddhist institutions and individual members when they are ill-treated, face unavoidable disasters, or encounter great difficulties. Article 54 further specifies that the association's supervisory board (Jianshi hui 監事會) is in charge of providing such mediation. It is also noteworthy that Article 26 also specifies that a member's membership can be revoked if one has committed offenses against state law or Buddhist monastic law, or has become indulgent in gambling or other reckless behavior that might damage the reputation of the association and the dignity of fellow monks and nuns; however, this Article on revoking membership was later removed because it was too abstract and unfeasible to implement in practice.Footnote 55

In protesting against many of the unfavorable Articles in this draft charter, the Buddhist community ended up losing more than they gained. In their effort to revise unreasonable Articles such as those requiring all ordained Buddhists to become members of this association and forbidding any lay Buddhists from joining this association, they also lost the offer to legalize the association's jurisdictional power over internal disputes among ordained Buddhists within the clergy. When the revision was delivered to the Buddhist Association of China in June 1936,Footnote 56 many lay and ordained Buddhists expressed their rejection of many of the new or revised articles. Around August 23, 1936, the editorial team of the Journal of the Buddhist Association of China reportedly received twenty-five comments on this revision.Footnote 57 Because of such protests, the charter was revised several times. In the later revisions of the charter subsequently promulgated in 1939 and 1947,Footnote 58 the article that offers the Buddhist Association of China the judicial power to adjudicate institutional and personal disputes involving ordained Buddhists disappeared permanently. This judicial power was never reintroduced in either of the charters of the Buddhist Association of China in mainland China or in Taiwan after 1949.

In recent decades, while still acknowledging the state's jurisdiction over ordained Buddhists who violated state law, the Buddhist Association of China attempted to reclaim the Buddhist establishment's jurisdictional autonomy over internal disputes among its ordained members. On October 21, 1993, the Buddhist Association of China approved the regulations on the national management of Chinese Buddhist monasteries (Quanguo hanchuan fojiao siyuan guanli banfa 全国汉传佛教寺院管理办法). Articles in these regulations recommend options for dealing with clerical offenders at three levels. Article 18 permits the hosting monastery/nunnery to convene an internal discussion on clerical offenders who had committed severe crimes, disobeyed community bylaws, or refused to correct their behaviours. The institutional administration team has the authority to expel the offender (qiandan 迁单). At the next level, the hosting monastery/nunnery can also report severe offenses that damage the reputation of the entire clergy to the local Buddhist Association, recommend and implement punishment by revoking the offenders' membership within the clergy, forfeiting their certificates of ordination (dudie 度牒) and the certificates attesting to their receipt of the precepts (jiedie 戒牒), and transferring their household registrations from the hosting institutions to their place of origin. For offenses violating the penal code of the state, the case would be adjudicated externally by the state's relevant law enforcement unit.

Procedure in Legal Practices

The State Administration for Religious Affairs conducted what appeared to be a preliminary administrative investigation. On August 23, 2018, this office announced the results of its investigation on its official website.Footnote 59 First, it confirmed that the accused had committed sexual harassment through texting. It considered this a violation of Buddhist monastic law and thus recommended the hosting monastery and the Buddhist Association of China take serious action to follow up in accordance with the relevant Buddhist regulations and the Charter of the Buddhist Association of China. Second, it did not confirm whether the accused had committed the alleged sexual assault but reported that the Beijing City police had officially filed a complaint and started an investigation. Third, it verified that allegations of administrative and financial misconduct were both true and the relevant local government offices had taken over the case to follow up with further investigation and charges.

As of October 2018, the only confirmed sexual misconduct by the accused was sexual harassment via phone text messages. The recommendation was to treat this offense according to Buddhist monastic law and the charter of the Buddhist Association of China. However, this charter addresses only issues concerning the administrative and financial management of the Buddhist institutions in China; it makes no reference to how offenses related to sexual misconduct should be handled. The Law of the People's Republic of China on the Protection of Women's Rights and Interests gives victims the option of filing an administrative complaint with their employer or the employer of the accused, or filing a civil lawsuit in state court, but does not specify what punishment would be imposed on the accused, if convicted. In Buddhist monastic law texts transmitted from India, having sexual intercourse is one of the four grave offenses for an ordained Buddhist monk, but verbal sexual harassment is not mentioned as sexual misconduct.Footnote 60

Punishment of the accused began even before the results of the investigation were announced publicly. While waiting for the result of the investigation from the State Administration for Religious Affairs, the accused quietly resigned from his post as President of the Buddhist Association of China. At its ninth national meeting on August 15, the association acknowledged its acceptance of this resignation. To this day, the whereabouts of the accused remains unclear.Footnote 61

Among the four possible prosecutors for Xuecheng's case, three of them either refused to respond or faced conflicts of interest. The monastery that had hosted the accused and the accusers was initially approached to handle the case, but the administration took no action. The position of the accused as the abbot of this monastery may have contributed to this lack of action by the monastery. Yet there were historical precedents about how to deal with such cases. During the Yuan Dynasty, a similar case was resolved by appointing the abbot of a nearby monastery to adjudicate the case. In the eighth month of the first year in the Yanyou 延祐 era (1314), a Buddhist monk Chonggui 崇圭 sued the abbot of his monastery for committing illicit sexual intercourse on a lay woman.Footnote 62 In the legal context of the Yuan Dynasty, an internal lawsuit between ordained Buddhists from the Buddhist clergy would be handled by the abbot of the litigants' hosting monastery. But the accused was the designated monastic judge for the lawsuit. So the Department of Justice (xingbu 刑部) ruled that the case should be litigated by the abbot of a nearby monastery. This was not how the 2018 case against Xuecheng was handled, however. The local police were also contacted, but apparently did not file the case, for unspecified reasons. Of the remaining two options, the Buddhist Association of China opted out because the accused was its president. This left only the State Administration for Religious Affairs to handle the investigation of this case.

Conclusion

The collapse of imperial China in 1911 gave way to a new legal system, providing opportunities for renegotiation of the Buddhist clergy's legal status and jurisdiction vis-à-vis the state. The need to protect Buddhist monastic properties from state and military encroachment forced Buddhists to collectively denounce personal clerical privilege under the new legal system in 1929. In imperial China, clerical privileges could range from immunity from trial in state lay court to lenience in punishment for the conviction of crimes.Footnote 63

This choice of Buddhist clergy to identify as ordinary legal subjects under state law was officially recognized. On June 9, 1932, the Minister of the Interior, Huang Shaofang 黃紹妨, defined ordained Buddhists monks and nuns as citizens who enjoy voting rights.Footnote 64 This new identity of ordained Buddhists was also respected by law in Republican China. On June 10, 1937, the Jiangsu provincial government inquired to the Ministry of the Interior as to whether an ordained Buddhist who had smoked opium would be disqualified from being nominated as abbot of a Buddhist monastery.Footnote 65 In its reply dated June 28, the Ministry of the Interior first declared that smoking opium is an offense against state law and thus requires punishment in accordance with state law. It recommended that the Buddhist clergy adjudicate the other aspects of the opium-smoking offense in accordance with the Buddhist monastic law. It further elaborated that an opium-smoker is absolutely disqualified from being nominated as the abbot of a Buddhist monastery, given that Article 11 in the Charter of the Buddhist Association of China does not even allow anyone who develops an unvirtuous addiction, violates the laws of the Buddhist monastic community, or commits other offenses to remain a member of the association.

The emergence of this new legal status of ordained Buddhists as ordinary citizens who fall under the protection and governance of state law had a lasting influence on how the Buddhist clergy positioned itself in the legal context of Republican and contemporary China. While the Buddhist Association of China offered the Chinese Buddhist institutions the jurisdictional power to adjudicate internal disputes among ordained Buddhists, the Buddhist clergy never sought to reclaim the clerical privileges that ordained Buddhists had fought for since the fourth century in imperial China.Footnote 66 The lack of special references to ordained Buddhists in the constitution and other criminal and civil law codes also indicates their acceptance as ordinary legal subjects within the state legal system.

Throughout the development of Xuecheng's case, individual monks and nuns in contemporary China have demonstrated a high level of legal sensitivity. As victims of sexual harassment and sexual assault, both Nun A and Nun C first approached the fellow monks in their community for help. When the monks became aware of the case, they provided the required assistance and reached out to the administration in the offender's hosting monastery to handle the case internally. When an internal resolution was unattainable, the victim Nun C and the monk supporters of the nun victims then reached out to the local police for support. Despite the lack of initial institutional cooperation, every step taken by the victim nuns and their monk supporters appears to comply with state law and the law of their religious community in the legal context of contemporary China described above.

The legal procedures adopted in handling the present case also help us understand how the realignment of relations between the state and the Buddhist clergy in Republican China came to define the state's exercise of control over religion in legal practice in China today. These procedures resonate with Welch's account of state governance of religion in late Qing. Before involving the police and the local government, the state allowed a third-party agency, between the state and the Buddhist clergy, to conduct the preliminary investigation. Because the accused was then the President of the Buddhist Association of China, the State Administration for Religious Affairs eventually took up the case. After the preliminary investigation, the hosting monastery and the Buddhist Association of China were invited to address the confirmed offense of sexual harassment in accordance with the Buddhist monastic law, the local government was invited to further investigate the allegations of financial and administrate misconduct, and the police was invited to investigate the allegation of sexual assault. In the handling of this case, external law enforcement was invited to intervene only when internal mediation failed. The entire process reveals that despite its harsh legislative control over religion and constitutional claims on ordained Buddhists as ordinary citizens under the state law, the state in legal practice nevertheless showed leniency to ordained Buddhist offenders, or at least to a high-profile state-appointed monk official.

Acknowledgments

I thank Leonard W. J. van der Kuijp for reading and offering critical comments on earlier drafts of this article. I also thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor of the journal, whose comments and suggestions have helped improve the article. All errors are my own.

Appendix: Articles on Ordained Buddhist Offenders in Republican Legislations