Introduction

On 26 July 1959, over one million Cubans converged on the city of Havana. The crowds had been gathering in and around the city for weeks, with a reported 14,000 peasants arriving daily.Footnote 1 By midnight, 500,000 guajiros from Cuba's various provinces joined Habaneros in the Civic Plaza to await celebrations commemorating the sixth anniversary of the rebel attack on the Moncada military barracks in Santiago de Cuba.Footnote 2 The Moncada celebration offered the new Cuban government a platform from which to showcase the political contributions of rural farmers and highlight the agrarian base of the revolutionary struggle. To publicly display Cuba's newfound commitment to its rural population, the government issued the peasantry a special invitation to the July celebration and made the necessary arrangements for guajiros to travel to Havana in time for the festivities.

As part of its demonstration of goodwill, the government also offered the international community access to the events of the day. Pre-recorded interviews with Fidel Castro aired in the United States on the day of the celebration, and foreign journalists flocked to the city to witness and report on the festivities.Footnote 3 Universal-International Press reported that ‘one million machete-wielding peasants jammed the square before Cuba's national capital in response to the call of Fidel Castro’.Footnote 4 While the numbers might have been exaggerated, this statement is indicative of the wonder that the scene inspired in all who witnessed the unravelling of events in Cuba, and with good reason. In the years preceding the political transition of 1959, urban areas in Cuba had been closely monitored to ensure that the spaces of the city projected a picture of Western civilisation. So much so, in fact, that by the administration of Gerardo Machado (1925–33), Cuba's urban model was threatening to transform the capital city ‘into a tropical Paris’.Footnote 5 The public face of neocolonialism also extended beyond architecture and urban planning; vagrancy and other laws, for example, excluded many of the city's visibly impoverished, non-white and rural populations from the political structures and social organisations of urban life.Footnote 6 Indeed, neocolonial administrations throughout Latin America differed little from their colonial predecessors in their ability to use the city as a base for (re)creating Hispanic civilisation in the Americas.Footnote 7 The decision by Mexico's Porfirio Díaz to ‘close’ the capital city to the country's peasantry in the days preceding the 1910 World's Fair provides striking evidence of this tradition. No less significant, however, was the nationalist response that neocolonialism inspired. A few years after the aforementioned event the Mexican capital was seized by the troops of Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata as Mexico erupted in revolution. The now-famous photograph of the two insurgent leaders sitting side by side in the National Palace serves as a reminder of the Mexican Revolution's challenge to neocolonial rule and is poignantly embodied in the troops’ occupation of the metaphorically ‘forbidden city’.Footnote 8

While the exclusivity of the city (and the challenge to this tradition) is a theme common to Latin America, it is also one rooted in the specifics of Cuban history. The country's long struggle for independence (1868–78, 1879–80 and 1895–8) underlined existing differences between urban and rural areas and created new disparities as guajiros arrived in towns and cities under a shroud of criminal suspicion. Following the end of colonial rule, displaced guajiros remained in urban areas as unwanted wards of the US administration, where the stigma acquired during the revolutionary struggle was honed into a narrative of rural difference that circulated well into the First Republic. To be sure, images depicting the guajiro as an embodiment of idealised nationhood circulated in Republican Cuba, but it is important to note that he was not only celebrated as a symbol of national identity, but as a distinctly white national symbol.Footnote 9 The implications of this are profound: if guajiros embodied Cuba's national soul and the term implicitly defined one as white, then Cuba might remain a nation of European descendants long after emancipation was achieved and independence realised. The nineteenth-century processes of emancipation and independence had not only allowed black Cubans to demand political inclusion in Cuba but had also forced white Cubans to reconsider the future position of blacks within the emerging Republic.Footnote 10 The direction in which the guajiro evolved can thus be read as a symbolic attempt steeped in Cuba's political history to exclude blacks from the emerging republic.

When Fidel Castro addressed the nation on that July day, he was likely recalling the guajiro's historical position vis-à-vis urban Cubans and the ideology that had long sustained such divisions. But the invitation to Havana issued to the Cuban peasantry was more than an embodied rejection of Cuba's colonial and neocolonial past. The rally also signalled the unification of urban and rural Cuba made possible, in part, by the government's atonement for how events had unravelled during the process leading up to independence.Footnote 11

For guajiros living in the western provinces, reconcentración had defined their experience of the final struggle against Spain. Reconcentración was the colonial government's attempt to determine the outcome of the war by forcibly relocating the Cuban peasantry to areas outside of towns and cities that remained under Spanish control. In reality, however, ‘reconcentration’ equated to a death sentence for the 155,000 to 170,000 Cuban guajiros subjected to the orders and irrevocably disrupted the lives of countless others who found themselves compelled to leave the ruined countryside.Footnote 12 Despite the damage it inflicted, the Cuban reconcentración has occupied only a small space in the English-language historiography of Cuban independence. Until the recent publication of John Lawrence Tone's War and Genocide in Cuba, 1895–1898, little was known outside of Cuba and specialist circles about the forced relocation of individuals during the final struggle.Footnote 13 The silence in the English-language literature stands in stark contrast to the fascination that North Americans, at least, seemed to have with the reconcentrados at the turn of the century. Reports from sources as varied as Harper's Weekly, the New York Times and The Patchouge Press all provided readers with regular updates on the Cuban reconcentrados. To be sure, the stories were politically motivated and coloured by the political fantasies of the publications’ readerships, but they nonetheless evidence a dearth of material around which narratives of the events can be pieced together. The current silence in the historical record is due in part to the nature of the aforementioned accounts and the scarcity of materials available in the Cuban archives – the result of changing political administrations in Spain and Cuba and the unwillingness of colonial administrators to be associated with the devastation.Footnote 14 The silence cannot all be attributed to a scarcity of material, however. It is also the result of a scholarly tradition that has looked to economic factors to explain the historic marginalisation of the Cuban peasantry and has said very little about the political uses of rural displacement.Footnote 15

This essay is thus an attempt to layer previous studies by positioning guajiros at the intersections of the armed conflict, where Cuban, Spanish and US political interests met. It uses war documents produced by the Cuban, Spanish and US armies to establish the movement of Cuban peasants and then analyses government records pertaining to guajiros, including the rich but hereto under-utilised archive of the US Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs, to arrive at an understanding of the raced and criminalised perception of the Cuban peasantry circulating between 1895 and 1902. The essay argues that the circumstances under which the rural population was brought into urban areas, while undermining the foundations of Spanish colonial rule, also criminalised guajiros in the process. The colonial government, after all, had pursued the policy because it associated the countryside with the rebel insurgency, and that association implicated guajiros as potential rebel combatants in the war. Unlike the insurgents, however, reconcentrados had not volunteered to fight in the independence movement, and their status as wards of the colonial government also made them immediately suspect to those who supported the cause of Cuba libre. During the process leading up to independence, then, guajiros found themselves inadvertently associated with both sides of the political struggle, and thus the targets of both the Cuban and Spanish armies.

This ambiguous position was a key factor in establishing future perceptions and in fuelling fear and suspicion among US administrators once Cuba gained independence from Spain. Because guajiros had made up the initial base of the armed insurgency it was not a great leap for US military officials to conclude that they could once again form part of another rebel insurgency similar to the one threatening US interests in the Philippines.Footnote 16 Race, too, played a decisive role in the ambiguous perception of guajiros and was used to further the political agendas of various parties. In the years immediately preceding the military intervention, North American journalists had depicted Cuban insurgents as the heroic, largely white descendants of Spaniards. As the political future of Cuba became increasingly linked with that of the United States, the image of Cuba and Cubans was radically transformed to depict the country as a ‘black’ nation akin to that of Haiti. The effect, of course, was to portray Cubans as racially inferior and therefore incapable of self-government.Footnote 17

But the correlation between blackness and the Cuban Liberation Army (CLA) was not solely a North American construct forged out of imperialist desires to keep the CLA at bay. Long before the military occupation began, Cubans in the western provinces had already begun to associate the armed insurgency with the black, mambí battalions from Oriente, leading to the popular perception that towns and cities were being overrun by a ‘black invasion’ from the east.Footnote 18 The correlation was one easily extended to the displaced guajiros. Not only did Cuban peasants make up much of the rank and file of the CLA, as did Cubans of African descent, but they also arrived in towns and cities as a result of the ruination of the countryside that followed in the wake of the CLA. Outbreaks of disease, too, seemed to ominously follow both migrants and insurgents, and further sharpened the negative and decidedly raced perception of the peasantry.Footnote 19 This is not to downplay the effects of the 11-month US military occupation of Havana, but rather to contextualise the US's ability to proliferate the decidedly negative and raced views of urban guajiros that were explicitly reproduced in the Cuban public sphere in the years that followed. The association of guajiros with blackness, criminality and disease that bled into the First Republic was thus the product of, to quote the late Cuban historian Francisco Pérez Guzmán, ‘la herida profunda’ that the country sustained during its final struggle for independence.

Colonial Reconcentración

During the 30-year armed struggle, towns and cities like Havana witnessed little of the fighting that ravaged rural areas and suffered even less of the infrastructural destruction. The shock of the war was experienced instead through the demographic shifts caused by the policy of reconcentración and the condition of the city in its aftermath. The first proclamation (bando) of relocation to affect the western provinces was issued on 21 October 1896.Footnote 20 By that time, almost two years had passed since the CLA had declared a revolution against Spain. After years of organising from abroad and successfully securing arms and provisions to fund the independence cause, military leaders Antonio Maceo, Máximo Gómez and José Martí returned to Cuba anticipating the start of the war. For insurgents and colonial administrators, command over the Cuban countryside and control over the rural population was a key component of the struggle. In fact, the colonial policy of reconcentración had been introduced as a military strategy during the earlier Ten Years’ War (1868–78) and practised in other areas of the Spanish empire. General Félix de Echauz y Guinart had published a report in the midst of his military campaign against the Cuban insurgency in which he detailed the actions necessary to ensure a Spanish victory, and the neutralisation of the rural population by reconcentración was central to his plan.Footnote 21 He pointed out that the natural resources found in rural areas enabled insurgents to survive for long periods of time and that access to the coastlines facilitated their ability to procure reinforcements from abroad. He urged Spanish officials to seal off the coast while ‘tearing up the country’ if they were to have any hope of defeating the rebels.Footnote 22

General Valeriano Weyler's decision to implement reconcentración in the autumn of 1896 would certainly prove the efficacy of his predecessor's military strategy. The forces of Maceo and Gómez had previously captured the eastern parts of the island, and by January of 1896 had also invaded the western provinces. Later that same year, however, the Spanish offensive to regain the liberated areas of the island severely punished the insurgency. Part of the Spanish offensive included support for General Arsenio Martínez Campos’ proposal to reconcentrate the Cuban peasantry. The general warned, however, that the policy's success would hinge on the funds and manpower available to colonial administrators and that it might well spell disaster for the Cuban peasantry, stating that ‘their misery and hunger would be horrible’.Footnote 23 By February of 1896, Martínez Campos’ inability to repel the Cuban insurgency had resulted in his replacement with General Weyler, who became the primary author of the military offensive that included the reconcentración of western Cuba.

The aggressive reconcentración in Pinar del Río in 1896 was influenced by the belief (harboured by both sides) that the rural population would play a key role in this war of economic destruction. The CLA had already evidenced its willingness to use the rural population to its military advantage. On 1 July 1895, Máximo Gómez had decreed that all Cuban labour from which the colonial government could derive profit should cease immediately. Those who failed to follow the order would have ‘their sugar cane … set on fire and their processing plants demolished’.Footnote 24 The proclamation was no doubt a powerful factor in Weyler's decision to counter Gómez's threat by rounding up the rural population in the western provinces. According to the October bando, guajiros had eight days to report to a specific locale and were expressly forbidden to bring foodstuffs, farm animals and various other possessions. Anyone found in the affected areas after an eight-day grace period would be reclassified as a ‘rebel auxiliary’ and treated as a captured member of the insurgent army.Footnote 25 More relocation orders soon followed – on 15 January 1897 Havana and Matanzas fell subject to the orders, as did Santa Clara two weeks later. Additional proclamations amplified earlier ones, forcing reconcentrados as well as guajiros voluntarily fleeing the countryside to arrive en masse and await resettlement instructions. Those who arrived on the outskirts of Havana came from as far away as Pinar del Río and Matanzas and brought with them news and information that spread panic among the urban population. The countryside was rapidly deteriorating, they claimed, and sugar mills were rumoured to be ‘ablaze in the province of Matanzas’.Footnote 26

For peasants, fire proved to be a dangerous weapon in the hands of the insurgents and a decisive factor in the destruction of the countryside. In the province of Pinar del Río, insurgents burned half of all standing towns after Maceo entered in January 1896. Juan Alvarez, one of Maceo's company commanders, reportedly burned not only vacant homes in the countryside but also those occupied by guajiros. Some 40 homes were torched in this way in the suburb of Luis Lazo in Pinar del Río alone, and inhabitants were forced to flee to towns and cities before the forces of Antonio Maceo.Footnote 27 Ironically, the actions of the insurgent army had a similar effect on the Cuban countryside as those of the colonial administration. As the colonial government focused its efforts on re-concentrating the rural population around towns and cities, the insurgent army quickly if inadvertently de-concentrated the Cuban countryside. Instead of forcibly relocating individuals, however, the insurgent army ensured that a steady stream of rural migrants would arrive in urban areas when unauthorised theft occurred or when guajiro homes and fields were set ablaze. To justify their actions, insurgents looked to stories of guajiros who had ‘gone to the city with the soldiers’ or else had sold food and livestock to the inhabitants of towns and cities, thereby helping to sustain the colonial administration.Footnote 28

Depopulating the countryside also had altruistic advantages for the insurgent leadership. If a new republic was to rise from the ashes of destruction, Cuba's urban areas would first need to be introduced to the liberating force that the Cuban countryside has always represented. What better way to prepare towns and cities to accept their transformation from loci of colonial civilisation into bastions of ‘Cuba libre’ than to allow guajiros to introduce the process? The fate of guajiros was thus sealed by the insurgency when it specifically targeted the remaining neutrality of rural labourers in the central province of Sancti Spíritus.Footnote 29 Unlike its previous proclamation targeting planters, this notice called for the criminalisation of all Cuban workers who laboured on sugar plantations or whose labour otherwise benefited the colonial administration, thereby ensuring that those guajiros who did not join the insurgent forces became rural migrants who would indirectly contribute to the insurgent effort.Footnote 30 The division of Cuba into a rural ‘republic-in-arms’ and an ‘urban colony’ served the practical interest of the insurgency. The leadership of the CLA seemed to understand that it could not take on the responsibility of clothing, feeding and otherwise caring for the large numbers of guajiros who, in part because of the scorched-earth policy that both armies pursued, were finding it difficult to feed and care for themselves. Gómez also understood that the only option for this population was to seek shelter in urban spaces, where they would quickly become the problem of the colonial administration and would thereby help divert funds and resources away from the war being waged against the insurgency. Guajiros fleeing to towns and city centres were also useful in their ability to relay information to urban dwellers who might otherwise have remained ignorant of the events occurring in the countryside. Their physical presence called into question the power of the colonial administration by illustrating the inability of the government to meet even the most basic needs of its subjects. Migrants and reconcentrados thus threatened to undermine the appeal of Spanish colonialism by exposing the perilous condition of the country's economic foundations and the impotence of the colonial government to remedy the situation.

Large planters in the western provinces also presented insurgent forces with an opportunity to chip away at the legitimacy of the colonial government. Despite popular (and true) accounts of wealthy planters who set their own cane ablaze in protest at colonialism, planters became the last bastions of colonial rule in the Cuban countryside and thus the primary targets of the CLA. During the war, half of the sugar-producing fields in the provinces of Havana and Matanzas were levelled. In Matanzas, 96 per cent of all farms and 92 per cent of all sugar mills were destroyed, and 94 per cent of horses and 97 per cent of all cattle were slaughtered during the fighting.Footnote 31 The numbers were similar across the island. Of the 1.4 million acres cultivated in 1895, only 900,000 had survived by 1898.Footnote 32 If the insurgent army could succeed in destroying sugar and other production, the Spanish government would be revealed as an inefficient entity that was unable to protect the interests of the planter class.Footnote 33

Meanwhile, in Havana, the precarious position of the colonial administration was apparent in the declining condition of the city. Visitors to the city commented on the circumstances under which colonial employees laboured. Economic transactions in the city, for example, were increasingly carried out in gold, silver, copper and the occasional US dollar. Although the war had made the colonial scrip unstable, colonial employees continued to be paid, when they were paid at all, in the depreciated scrip. As a result, many could be found begging for alms on Havana's streets. This is perhaps not surprising given that banknotes issued by the colonial government in 1896 had lost 96 per cent of their value by the end of the war.Footnote 34 After 1896, city residents experienced the war in far different terms than their rural counterparts. Unlike the guajiros, who continued to experience the war through personal losses and the relentless destruction of the countryside, Habaneros, like other urban residents, experienced the war through the increasing inability of the colonial government to care for the city and its population of newcomers.

General Weyler's failure to ameliorate the increasingly perilous and public conditions of the reconcentrados or shift the tide of the war resulted in his replacement with General Ramón Blanco in October 1897. One of Blanco's first decisions was to ascertain the number of individuals displaced from the countryside and living in towns and cities before moving to end the reconcentración. He ordered provincial governors to provide numbers for the reconcentrados in each district and the conditions in which they lived. In Pinar del Río, 47,000 people were reportedly part of the reconcentración out of a total population of 226,692, and 50 per cent of the reconcentrados were claimed to have perished. Matanzas reported a total of 99,312 reconcentrados out of a total population of 273,174. The mortality rate in the province was placed at 26 per cent. Santa Clara, which served as the front line for much of the period, suffered 140,000 reconcentrados and a 38 per cent mortality rate among them.Footnote 35 While the provincial governor of Havana did not report numbers, data are available from the reports prepared by the US government in January 1899. Approximately 150,000 individuals, many of them women and children, had reportedly been reconcentrated to the Province of Havana, which at the time had a population of 235,981.Footnote 36 In the three-month period from August to December 1897, 1,700 individuals entered the Havana camp known as Los Fosos (The Ditches). By December of 1897, 460 of the new arrivals were said to be dead or dying from disease and starvation.Footnote 37

As Martínez Campos had predicted, the strained resources of the colonial administration could not meet the expenses of both the armed struggle and the reconcentración. Under Weyler, much of this responsibility had been shifted to local government and private individuals. ‘Cultivation zones’, for example, had been created with the initial reconcentration orders in Oriente and were a crucial component of making the reconcentración feasible in the western provinces. The zones were envisioned as a way to facilitate the administration's ability to feed reconcentrados (or rather, to allow reconcentrados to feed themselves), but they also functioned to strategically further the colonial government's war efforts. Reconcentrados with suspected familial ties to the CLA were denied provisions as a way to punish and deter future insurgents.Footnote 38 Because they were administered by the colonial government and run by municipal juntas composed of a military commander, judge, alcalde and urban residents, the zones were also looked at suspiciously by insurgents, causing frictions to erupt between reconcentrados who laboured in the zones and members of the insurgency. After Blanco's arrival, insurgent suspicions increased when the administration suspended the orders of reconcentración.Footnote 39 As part of the suspension, the administration agreed to provide daily food rations and work opportunities in the sugar cane fields still under cultivation. It also agreed to furnish reconcentrados with civil and military protection and guaranteed their treatment at the hands of the Spanish planters.Footnote 40 The precarious nature of the reconcentrados’ position became evident when the administration acknowledged the reconcentrados’ need to carry arms in order to defend themselves and their property.Footnote 41 Exactly who they were defending themselves from, however, was a question with perhaps too many possibilities to answer.

Outbreaks of disease also aggravated living conditions and contributed to the stigmatisation of guajiros. Starvation, anaemia, and intestinal and other diseases had a devastating effect on the rural population congregated in and around the towns and cities. Disease had a tendency to follow the same course as the insurgent army and travel through the same rural areas. Smallpox infections increased in the eastern areas of the island along with the fighting, and the epidemics tended to move westward. Indeed, the insurrection actually altered the spatial dynamics of disease and introduced new epidemics into areas previously immune to outbreaks.Footnote 42 In the city of Havana, the sanitary inspector of the United States Marine Hospital Service (USMHS) noted that outbreaks of smallpox had ‘increased very considerably’ among the civilian population.Footnote 43 This came as no surprise to the servicemen stationed at the USMHS whose job it was to inspect port cities and who had declared Los Fosos a ‘pest hole’. One serviceman noted that on the day he inspected Los Fosos, ‘there were 500 people found in and around the building, and of that number over 200 were found lying on the floor sick and dying … the emaciation of their bodies [was] startling’. By December of 1897, the USMHS believed that 1,190 of the 1,700 guajiros assigned to Los Fosos had perished.Footnote 44 The dependence created by the reconcentración, the escalation of the war and the rapid spread of disease meant that by the end of 1897, the number of recorded deaths in the province of Pinar del Río had increased from the pre-war level of 1,857 to 15,454. In Havana province, the number went from 6,730 to 18,123; in Matanzas, from 6,775 to 25,347; and in Santa Clara, the number skyrocketed from 8,427 to 46,477.Footnote 45

Like the reconcentrados in towns and cities, the spread of disease played directly into the strategy of insurgents and worked to discredit the colonial administration. The island's Junta Superior de Sanidad (Superior Board of Health), which convened regularly through 1896 to discuss the spread of contagious disease, noted that colonial soldiers were the primary reason for the growing number of deaths in Havana.Footnote 46 Before reconcentrados and rural migrants became the chief sanitary concern for the administration, the sick and dying Spanish soldiers produced the perception of urban disorder that would later cast doubt on the colonial administration's ability to rule.Footnote 47 Moreover, the deadly outbreaks of disease, specifically the smallpox epidemic of 1896–7, devastated Havana residents not accustomed to dealing with epidemics of this magnitude since the end of the earlier Ten Years’ War, and certainly not in every environ of the city.Footnote 48 The epidemic spread outside of Havana and infected areas along the northern coastline, including Matanzas, Sagua La Grande and Pinar del Río. When the disease resurfaced a year later, it was clear that the city was the source of the contagion.Footnote 49 To urban dwellers in the western provinces, the epidemic implicated the population of reconcentrados. Where once outbreaks of disease had been contained to the poorer sections of the city, epidemics were now spreading beyond indigent neighbourhoods and resurfacing at the height of the reconcentración, travelling the same path as the war. This placed the blame for contagions squarely on the shoulders of the city's new arrivals. The USMHS further reinforced this belief when it concluded that ‘the localities affected most are along the bay, near the wharves, and in the suburbs. Here, on the one hand are segregated poorer classes, in overcrowded and unsanitary dwellings, and, on the other, the refugees from the country. The unusual epidemic is mostly due to the great influx of these refugee country people’.Footnote 50 The USMHS's statements reveal the growing belief among US administrators and Cubans alike that, as the war continued, reconcentrados and displaced guajiros were to blame for the outbreaks of contagion.

The displaced also found themselves at the centre of other controversies that reinforced the belief that they constituted a dangerous element in the city. Necessity-driven criminal activity in Havana, such as the theft of food and animals, dramatically increased along with criminal activity in general.Footnote 51 While this increase in theft is not surprising given the lack of resources available, there were, of course, other reasons for the rise in crime. Men, women and children broke with colonial laws because enforcement was now lacking. In this way they signalled the weakening power of the colonial administration through its inability to enforce public order.

Once the orders to end the reconcentración were extended in March 1898, fully bringing the policy to a close, reconcentrados found themselves facing many of the same dangers they had previously encountered. With the aid of the Board of Reconcentrados, private charities, citizens and church officials, each municipality was responsible for relocating the rural population living in its respective area. The perils of returning home, however, remained all too real for reconcentrados. Rumours circulated that Spanish soldiers were indiscriminately shooting guajiros outside of former camps, and that guajiros were dying for lack of food and water in the Cuban countryside.Footnote 52 Reports from colonial administrators corroborate the rumours, although they assign the blame to the insurgent forces.Footnote 53 The uncertainty of who was responsible for the murders suggests that both armies were perceived as potential aggressors and that both sides saw reconcentrados as enemies ‘more or less disguised’.Footnote 54

Despite the dangers, government administrators found ways to encourage those who remained in towns and cities to return ‘home’. The military governor of Marianao, for example, not only issued an order providing for the return of the displaced guajiros but was also prepared to offer his protection, US$ 500 to be distributed among the returning families, and free rail tickets.Footnote 55 The declining condition of the city played a key role in official attempts to relocate guajiros to the countryside. According to USMHS observers in Havana, ‘the streets and pavements reek with human excreta, both solid and liquid matter being scattered around indiscriminately … An inspection of the principal markets developed the fact that meats exposed for sale were not protected from the filth floating in the atmosphere’.Footnote 56 Other reports blamed deteriorating conditions on the unproductive newcomers, especially those with physical conditions that prevented them from working or leaving the city. One observer noted that ‘cities, overfilled with men, women, and children without work, were unable to sustain a population of consumers who produced nothing’.Footnote 57 Given the perils of the countryside and the resultant reluctance of some reconcentrados to return there, the Board of Reconcentrados distributed emergency provisions such as food, clothing and medicine, and established soup kitchens to aid those in need.Footnote 58

Emergency help also arrived from the expected sources. The United States, always an interested party where Cuba was concerned, now rallied to the aid of the reconcentrados. International indignation at the conditions created by the war had escalated since Weyler first implemented the reconcentración, and now prompted the American Red Cross, directed by Clara Barton and working under the direction of the US Department of State, to lead the relief efforts. The result was the Central Cuban Relief Committee, which in January 1898 began to collect food, clothing, medical supplies and money to ship to Havana.Footnote 59 By February, an estimated US$ 40,000 in aid had arrived in Cuba, including 40 tons of food.Footnote 60 When the USS Maine blew up in Havana harbour, however, the committee's relief efforts were indefinitely postponed and many of the provisions sat in the harbour and in padlocked warehouses pending the US's decision on its future role in Cuba. By the second week of April, the Red Cross was forced to evacuate in fear of an imminent declaration of war.Footnote 61

Clara Barton's efforts are evidence of the attention that the plight of the reconcentrados received in the United States and the munificence that the imagined population elicited. Gender played a significant role within popular US constructions of the reconcentrated population and the country's subsequent extension of charity to this group. Isabella M. Witherspoon, a part-time novelist from Long Island, New York, exemplified US approaches towards the displaced guajiros.Footnote 62 In 1898, instalments of Witherspoon's novel Rita de Garthez, The Beautiful Reconcentrado appeared in a local newspaper for the enjoyment of a US readership. The fictional account described the heroic journey that took one peasant from the rural countryside and into Havana in search of his missing family. The guajiro's journey begins when he returns to his village after a suspicious absence (one assumes he was with the insurgency) only to find it torched by colonial soldiers and his mother and sister subjected to reconcentración. He thus begins the odyssey that takes him into the city, where he concocts a plan to procure US intervention and save the lives of the reconcentrated peasants. While Isabella Witherspoon and her contemporaries wrote about the fair-haired descendants of Spaniards (in the title of her novel, ‘Garthez’ was likely an attempt to mimic Castilian Spanish), her readers must have imagined not only a noble Cuban peasantry unjustly persecuted and fighting against a tyrannous monarchy but also the innocent victims of the struggle, many of whom were women, children and the elderly (see Figure 1). Women's journals, weekly magazines and newspapers all published accounts of the war in Cuba and used the age and gender demographics of the reconcentrados, the plight of the rural population and the inhospitable environment of the city to lobby for US intervention.Footnote 63 Stories of the insurgents and the deserving population of reconcentrados stirred many to action: the Ward Line shipping company in New York, for example, volunteered to transport all charitable goods collected by the Red Cross to Havana free of charge. Without the cooperation of this company and others like it, the prohibitively high costs of shipping would have likely prevented the work of the Red Cross and the distribution of goods in Cuba.Footnote 64

Figure 1. Los Fosos on the Front Cover of Harper's Weekly, 2 April 1898

Barton's efforts, like Witherspoon's novel, helped to create an appealing image for a US public already intimately familiar with the policy of reconcentración. The photographs and short stories printed in the US media painted reconcentrados in ways that resonated with the moral sensibilities of the US public; the fact that many of the reconcentrated were women and children only helped propel public interest forward. The United States ordered reports to be compiled and invited North American writers to testify before Congress about the ‘real condition’ of Cuba. Photographs also circulated depicting indigent mothers and children with distended bellies; men were also present, albeit elderly or emaciated. The public relations campaign was brilliant. As far as the US public was concerned, the guajiro population was composed of the same young men and women that Witherspoon had imagined, along with their helpless dependents. Furthermore, unaccompanied women whose fathers, husbands and sons had either become part of the insurgency or else fallen victim to the villainous Spanish elicited easy sympathy. For North Americans familiar with the story of Evangelina Cisneros and her detention in Cuba, the women and children who languished in detention camps were evidence of the injustice and lasciviousness of Spaniards. The representation of the reconcentrados thus served to produce the moral outrage necessary to convince the US public of the need to protect Cuba's population of women and children. More importantly, however, their gender and age made them not only a sympathetic population but a politically impotent one as well. Intervention would therefore come on behalf of recognisable, deserving reconcentrados who could pose no future political or military threat.

The interest of the US and its potential political consequences were not lost on the Cuban population, some of whom took the opportunity to decry intervention as opportunist. The Havana-based Diario de la Marina lauded the colonial administration's rejection of US help once the US declaration of war was issued on 25 April 1898.Footnote 65 Others saw the foreign offers of aid as an opportunity to join a fashionable cause. Balls and charities organised by affluent urban dwellers reflected an urban and middle-class affinity towards the United States that long pre-dated the decline of colonial rule and that further exposed the colonial government's impotency in caring for its dependent population.Footnote 66

The long-awaited declaration of war brought with it a naval blockade and had disastrous consequences for the rural population. Those who remained found sanctuary in Los Fosos. Four other camps in Havana province, some of which doubled as prisons, hospitals and orphanages, also served as makeshift refugee centres. In an ironic shift of fate, the centres of forced confinement now became ad-hoc sanctuaries for guajiros living in urban centres. Those who decided to ‘relocate’ to the countryside amidst the worsening conditions radically altered the demographics of the island. Railway stations became popular living quarters for former reconcentrados, as rail tickets were relatively easy to obtain for those who wished to reach the interior of the island and makeshift towns provided access to travellers who might provide alms. Railway stops also became the pragmatic endpoints of the journeys ‘home’ that many guajiros found themselves incapable of finishing. In the town of Jaruco, some 20 miles east of Havana, thousands of reconcentrados turned the railway stop into an overnight refugee centre.Footnote 67 The Red Cross reported that ‘Jaruco is one of the great points of devastation; it is said that more people have died there than entire town numbers in times of peace. Everything is scarce and dear; even water has to be bought’.Footnote 68 By the end of the reconcentración and the beginning of the US military occupation, guajiros found themselves in an ‘in-between’ space – neither defeated colonialists nor triumphant victors, and part of a Cuba that could no longer be defined as exclusively urban or rural.

Military Occupation

The ways in which North Americans had imagined Havana posed irreconcilable contradictions between popular US perceptions and the reality that the US administration encountered on 1 January 1899. The ‘discovery’ of a racially mixed military leadership when US depictions had portrayed insurgents in the same white, racially homogenous terms as guajiros helped explain the exclusion of the CLA and the imposition of military rule to North American audiences (and no doubt some Cuban ones as well).Footnote 69 Like the USMHS in Havana, the US military would reinforce the association between guajiros, the insurgent army and blackness. Upon entering the city, US administrators and their military forces encountered all of the visual signifiers that resonated with their own understandings of blackness but that did not translate into similar racial ideologies in Cuba – especially among the ‘liberated’ guajiro population, many of whom would have considered themselves ‘white’ by virtue of geography, history and tradition. Given the latent racism that had long associated disease and criminality with blackness, it was not a great leap for administrators to attribute Havana's perilous condition to its non-white population.Footnote 70 Displaced guajiros in need of services were further looked to as evidence of the racial ‘character’ of the island and the inability of the population to care for itself.Footnote 71

The pervasiveness of racism was not just a phenomenon among US administrators. Despite the popularity of José Martí's discourse of a ‘raceless’ nation of Cubans, Cubans themselves were not immune to colonial racial ideologies, and this included the members of the Cuban insurgency. It is true that the CLA boasted a significant number of black and mulatto leaders: Antonio Maceo, José Maceo, Guillermo Moncada, Dimas Zamorra, Quintín Bandera(s) and Flor Crombet were all honoured members of the rebel insurgency, many of them from the significantly ‘blacker’ areas of Oriente. This did not insulate black officers and their troops from the racism of white officers and soldiers, however, or from the regionalism that often equated Cuba's eastern provinces with blackness. Ada Ferrer's study of Quintín Banderas demonstrates that the latent racism present among members of the Cuban insurgency could lead to charges of ‘uncivilised’ behaviour being brought against black officers from Oriente, and that black and mulatto soldiers in the rebel army also experienced similar acts of racial discrimination when they transgressed colonial racial norms.Footnote 72 Ferrer's study highlights that Cuban perceptions of ‘uncivilised’ behaviour were intricately connected to Cuban geography. This meant that as the CLA made its way from Oriente into the western provinces of the country, it had to combat the raced and racist perceptions of westerners, which is not surprising given Cuba's demographics at the time. In areas of Oriente the population classified as ‘non-white’ was listed as 63 per cent, a significant contrast to the 32 per cent figure of a place like Las Villas.Footnote 73 Thus, as the CLA moved westward, it had to contend with Cuban concerns over the racial nature and direction of the war.

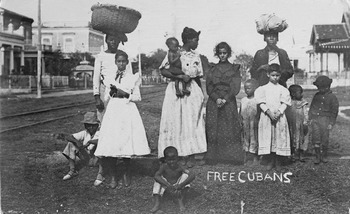

Figure 2. Free Cubans, Cuba, 1898

Insurgents and guajiros who found themselves associated with the CLA (whether accurately or not) aroused suspicion and racial stereotyping. Esteban Montejo, a former slave, ‘guajiro’ and soldier for the insurgents, recounted the racism he was subjected to not just by members of the CLA but also by foreigners who reinforced Cuban beliefs that the insurgency was waging a race war against the ‘civilisation’ that colonialism had fostered. In one particular account, Montejo relates how his struggle with a Galician man and a conscript in the Spanish army carried explicitly racial overtones. After sparing the man his life, Montejo is surprised when the Spanish soldier accuses the insurgent army of being composed of ‘savages’. As an explanation for the epithet, Montejo offers: ‘They started to think we were animals, not men – that's how they came to call us mambises. Mambí means the child of a monkey and a buzzard. It was a taunting phrase’.Footnote 74 While there is no evidence that the term originated as a racial slur, the encounter nonetheless illustrates the centrality of race and racial perception during the wars. For mambises, racial identification provided a central component of their identity as insurgents, in part because of the significance placed upon it by Cubans, Spaniards and North Americans. Ironically, just as foreigners had played a key role in the ‘white’ perception of guajiros almost a century earlier, they now contributed to the ‘black’ perception of insurgents and orientales and associated the CLA with a ‘savage’ black constituency. To further complicate matters, few foreigners (or Cubans, for that matter) could distinguish or cared to distinguish between ‘black’ members of the CLA, mambises, rural insurgents, peasants and their ‘white’ counterparts. Rather, designations were based on geography, history and tradition – and the war and subsequent reconcentración disrupted many of the historic understandings when it implicated displaced guajiros in the decline of the city, the spread of disease and the increase in criminal activity.

Not surprisingly given the racial perceptions of the island, the US military disarmed and then disbanded the CLA almost immediately after arriving in Havana. Some former officers and soldiers were assimilated into the newly formed Guardia Rural (Rural Guard), but many others refused to relinquish their arms and remained part of a dissatisfied and disenfranchised rural population.Footnote 75 To US administrators, the population of guajiros constituted a potential problem similar to that which they had represented for the colonial administration.Footnote 76 Fitzhugh Lee, the military governor of Havana in 1899, warned that ‘if by accident or bad management an exchange of shots took place anywhere between the Cubans and American soldiers … the country might have a guerrilla war on its hands and our troubles [will] multiply’.Footnote 77 To complicate matters, guajiros were no longer isolated in the more remote areas of the island as they had been years earlier. In the event of an altercation, Lee recognised that the legitimacy of the US administration on the island would come into question, as the conflict would provide Cubans with visible evidence that US administrators, like their Spanish predecessors, were unable to provide Havana with the urban amenities that they had implicitly promised with the occupation. Gaining control over the island and legitimating the power of the US administration thus became a project that began in the city. The urban services that had reinforced the power of colonial rule had come to a complete stop, with disastrous effects for urban dwellers. On the eve of independence, the number of urban poor in and around Havana had actually increased. According to the US general in charge of overseeing the rebuilding of the city, William H. Ludlow, ‘the physical condition of the city could only be described as frightful. There were several thousand reconcentrados in and about, who had been herding [sic] like swine and [were] perishing like flies. They were found dead in the streets and in their noise some [sic] quarters, where disease and starvation were rampant. Other thousands were lacking food, clothes, and medicine’.Footnote 78 At the outset of 1899, 242,055 indigents composed of former reconcentrados and migrants were congregated on the urban periphery.Footnote 79 Reconcentrados, Ludlow commented, were ‘dying in streets and alleys’.Footnote 80

Like the colonial administrators and the urban residents themselves, the acting sanitary inspector of Havana Province, Foster Winn, attributed new outbreaks of smallpox, dysentery, yellow fever and malaria to the city's population of former reconcentrados.Footnote 81 In part, Winn was correct to point out the correlation – during the reconcentración, the number of deaths attributed to disease had increased in Havana. Between 1895 and 1896, deaths in the municipality jumped from 7,410 to 11,728; the figure increased again between 1896 and 1897 to 18,123, and again in 1898 to 21,235. In the span of less than one decade, the city had witnessed a 300 per cent increase in the numbers of dead or dying. Between 1897 and 1898, over 1,500 Habaneros perished in the span of just one year and thousands more died in the poorer municipalities as a result of the epidemics. Across the bay, in the town of Regla, over 3,000 deaths occurred in 1898. In Guanabacoa, over 3,500 deaths occurred as a result of disease.Footnote 82

Because former reconcentrados were visibly implicated in the deteriorating physical conditions of Havana, they became part of the US reconstruction plan that emphasised hygiene, sanitation and order. The reintroduction of sanitary and urban services was successful in decreasing the number of deaths and epidemics. By August of 1899 deaths in the municipality of Havana had dropped to 6,136, and epidemics showed a similar decline. Yellow fever cases had increased threefold between 1895 and 1896 (jumping from 570 cases to 1,540 by August of 1899), but there were only 19 documented cases in the entire Municipality of Havana by the end of the US military occupation.Footnote 83 Routine censuses were also implemented to monitor health and disease. The health department in Havana investigated numerous cases of typhoid, tuberculosis, meningitis and yellow fever in the city and its surrounding areas. The cases were separated by age, race, and neighbourhood in order to more closely monitor and quarantine the offenders.Footnote 84 By the beginning of the First Republic, no new cases of yellow fever were reported in the Municipality of Havana and outbreaks of disease were also successfully contained.Footnote 85

The US focus on health and infrastructure was a strategic one. If US administrators had learned anything from the failures of Spanish colonialism, it was the importance of maintaining political legitimacy in towns and cities. Guajiros and the conditions in which they lived, particularly in and around Havana, were therefore the natural targets of the US project in Cuba. The US's economic investment reflects this understanding. An additional US$ 50,000 was allocated for the express purpose of dealing with health conditions in Cuba, and administrators hired private contractors to oversee the reconstruction of the city.Footnote 86 They cleared vacant lots, urbanised neighbourhoods, and transformed empty city spaces into public parks.Footnote 87 Street paving, cleaning and trash collection were once again urban staples. The area spanning the municipality of Havana and its outlying neighbourhoods was surveyed, redefined and redrawn into a newly formed and incorporated Department of Havana. To avoid another epidemic of yellow fever, all public buildings were cleaned and disinfected, and 35 miles of sewers were emptied and renovated to allow for proper drainage.Footnote 88 Most importantly, the new Office of the Municipal Architect emphasised hygiene in ways that not only made the city an attractive and modern environ but also divorced Havana from the reconcentración and its population of displaced guajiros.

There were other factors contributing to the emphasis on hygiene and correcting the problems associated with displaced guajiros. Mariola Espinosa has noted that the impetus for US intervention in Cuba emanated, at least in part, from a need to insulate the US economy from the economic toll that quarantines associated with disease would take.Footnote 89 Outbreaks in Cuba affected the US economy, principally in the US south, because of the danger of transporting yellow fever from Havana into US ports. The overwhelming belief among residents and administrators that guajiros were the source of contagions provided the military government with yet another reason for ridding the city of the displaced population. To have done otherwise might not only have jeopardised the legitimacy of the new administration and hurt its economic interests, but also posed a threat to the future of US–Cuban economic relations. To reinforce its emphasis on hygiene, the Office of the Municipal Architect stipulated that any residence deemed dangerous or unhygienic should be immediately demolished.Footnote 90 The building codes were tantamount to an order of relocation for many residents who could not afford to rebuild under the new regulations or who were otherwise occupying insalubrious abodes. Many of the displaced guajiros who remained in Havana after the reconcentración thus found themselves the targets of the US military government. They remained as part of a new urban underclass that, decades later, would prompt one Havana resident to describe rural migrants as having reduced the dignity of the city ‘to the level of savagery’.Footnote 91

Conclusion

For long-time residents of Havana, the impetus to accept North American rule came about as the colonial project was visibly discredited and the United States emerged to fill the vacuum as a protector of urban and propertied interests. After an initial improvement in conditions, however, the number of urban poor in and around Havana had increased from 242,055 in 1899 to 302,526 in 1907. And despite the eradication of epidemics, sanitary conditions for Havana's poorest residents had seen only marginal improvements.Footnote 92 Disparities between urban and rural populations continued to increase during the First Republic, to the extent that by the mid-1950s, just prior to the emergence of the July 26 Movement, unemployment was 7 per cent higher and illiteracy rates were four times greater for rural Cubans than for their urban counterparts.Footnote 93 These disparities did not go unnoticed. Differences in living standards were critiqued in publications with urban readerships; the Havana serial Bohemia ran stories contrasting the modern advancement, good nutrition and overall wealth of urban areas in the western provinces with the rural areas of Oriente. In its depictions, housing and urban services were often used as the measures of modern living, and the contrast, which had always been stark, was now startlingly bleak.Footnote 94

The gathering of the Cuban peasantry in Havana on 26 July 1959 was thus laden with symbolic meaning. It sought to address some of the central issues raised by the independence wars but unsatisfactorily answered (for the new government, at least) during the neocolonial republic that followed the US military occupation. The reconcentración, for example, had not only dislocated hundreds of thousands of individuals but also served to organise Cuban, Spanish and North American views of the peasant population. The strategic associations that emerged between guajiros and blackness, criminality and disease were therefore important because they all but ensured that guajiros would become little more than the fictional soul of an independent Cuba trying to come to terms with the nature of its independence.

The response of Habaneros to the crisis of the guajiro, however, also serves to illustrate the limits of colonial and neo-colonial ideologies. When guajiros were unable to return to the ruined countryside following the end of the reconcentración, for example, some displaced peasants found refuge and lodging in the private homes of individuals.Footnote 95 Luisa Quijano from Marianao took on the care of reconcentrados who were in ill health and suffering from disease.Footnote 96 Quijano's move foreshadowed the response of the urban population decades later, when Fidel Castro would ask Habaneros to accommodate the large numbers of peasants invited to the city for the July celebration. Symbolically at least, the scene in Havana on 26 July 1959 was the final step in uniting the ‘two Cubas’ that Máximo Gómez and Antonio Maceo had seen when they looked across the war-torn island. They saw an urban, Spanish and ‘colonial’ Cuba thriving in towns and cities, while ‘Cuba libre’ was alive and well only in the rural countryside. It seems that for its part, the leadership of the July 26 Movement subscribed to a similar belief. The mythology of the movement located Cuban nationhood within the countryside, away from the dystopia of the city and within the redemptive figure of the guajiro.Footnote 97 But it also sought to introduce towns and cities to this redemptive power. The peasantry's arrival on 26 July was the yearned-for arrival of the Cuban manigua that had long eluded the Cuban insurgency. Only by bringing the redemptive power of the countryside and the guajiro into the city (both literally and figuratively) could the new government finally disassociate the urban areas of Cuba from the colonial and neocolonial administrations of the past. The rhetorical transformation of the Cuban peasantry into the moral fibre of the nascent revolution thus served a pragmatic purpose as well as a symbolic one. The event effectively provided a second opportunity for urban inhabitants and the new government to capitalise on the revolutionary potential of the guajiro and thus prove worthy of becoming the seat of the new revolutionary government.