While repairing Rio de Janeiro's sewer network in advance of the 2016 Olympic Games, construction workers came upon an unexpected past: the remains of the port that received approximately 900,000 captives in the transatlantic slave trade. The rediscovery of the Valongo Wharf prompted Rio de Janeiro's then-mayor, Eduardo Paes, to exclaim, ‘when I saw the place, I was absolutely shocked. I am going to build a plaza there like in Rome. Those are our Roman ruins.’Footnote 1 That plaza has yet to materialise, though in July 2017 officials from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) did add the site to its World Heritage list. Drawing comparisons to Hiroshima and Auschwitz, UNESCO described Valongo as the ‘most important physical trace’ of the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans in the Americas.Footnote 2

Both Paes’ and UNESCO's recognition of the port aligns with a recent expansion in public, official sponsorship for the excavation and preservation of the material remains of the transatlantic slave trade, slavery and racialised violence throughout the Atlantic basin. In what historian Ana Lucia Araujo has termed the ‘memorialisation phenomenon’, reais, euros and dollars have funded an array of projects far beyond Valongo, from the International Slavery Museum in Liverpool (opened in 2007) to the Whitney Plantation Museum in Louisiana (opened in 2015).Footnote 3 The New York Times Magazine billed the Louisiana site as the first museum dedicated to slavery ‘in America’.Footnote 4

The city of São Paulo has, to date, not appeared on the map of these myriad memorialisation projects. Readers would be right to ask: why should it? Dominant popular and academic representations have long cast the city of São Paulo as a non-Black, immigrant metropolis whose growth had little to do with slavery, the slave trade and African descendants, particularly in comparison with the supposed true hubs of Africa in Brazil, the cities of Rio de Janeiro and Salvador in Bahia. The myth of São Paulo as a non-Black, immigrant metropolis obscures much of the actual history of the city and province of São Paulo, including the city's role as the provincial capital of one of plantation slavery's final frontiers in the Americas, or what historians have termed ‘Second Slavery’.Footnote 5

In this article I examine how the destruction and reproduction of geographic space served in the construction of the myth of São Paulo as a non-Black, ethnically immigrant metropolis in the middle of the twentieth century.Footnote 6 From the 1920s to the 1960s, São Paulo's urban planning and political elite transformed the geographical and historic centre of the city through an ambitious modernisation plan structured by asphalted avenues. The roadways that the plan's authors considered most vital – from functional as well as symbolic perspectives – cut through the districts of Liberdade and Bela Vista. Through the 1940s, these districts had the first- and third-highest proportions of populations of African descent in the city.Footnote 7 In addition, they possessed significant sites linked to histories of slavery, racial violence, formal abolition and Black liberation. São Paulo musician Geraldo Filme described these places as two of the three neighbourhoods comprising the city's early twentieth-century ‘zona do negro’, or ‘Black zone’.Footnote 8

Beginning in the 1930s, expropriations, demolitions and roadway construction transformed the material and social composition of Bela Vista and Liberdade, pushing many African-descendent residents to the city's margins and razing some of the sites they considered significant. Beyond the material reconstitution of the region, this planning project also transformed the ethnoracialised geography of these two neighbourhoods. Constructing asphalted avenues in Liberdade and Bela Vista paved the way for the transformation of these neighbourhoods in the following decades into two of the city's iconic ‘Japanese’ and ‘Italian’ spaces. Those reconstructions survive through the present. Cherry-blossom lanterns, Italian cantinas and a towering Shinto torii dominate the visible landscape of these archetypical ‘ethnic enclaves’, providing concrete support for the myth of Brazil's most populous city as a non-Black, multicultural metropolis.

In the following I excavate the history of a singular demolition that took place in 1942–3 during this expansive redevelopment project. Located at the northern tip of the Liberdade neighbourhood, the Church of Our Lady of Remedies (Igreja de Nossa Senhora dos Remédios) served as the headquarters of a radical, final phase of Brazil's antislavery campaign in the 1880s. Abolitionists based at the Remedies coordinated mass flight from plantations in the provincial interior and relocation to quilombos (freed settlements) throughout the province of São Paulo. They also published an influential antislavery journal, A Redempção (‘The Redemption’). For five decades following the formal abolition of slavery in 1888, the church then housed a museum to the enslaved – perhaps, contrary to the New York Times Magazine appraisal of the Whitney Plantation Museum, the actual ‘first in [the] America[s]’ – replete with objects like shackles and instruments of torture that freed people had carried with them into Liberdade.

It would not be wrong to say that the Remedies church and museum were largely forgotten after their demolition in 1942–3, but such a characterisation presents forgetting as a passive process: a seemingly inevitable result of palimpsestic urban change in former slave societies. Forgetting, however, can also take place through deliberate effort and an organised set of practices. In other words, forgetting can also amount to a project.Footnote 9 Through historical mapping and granular, though revealing, archival evidence, in the following I outline the motivations behind, and meanings of, razing the Church of the Remedies. The levelling of this singular site, I argue, comprised part of a spatial project of forgetting where the demolition and dislocation of the city's ‘Black zone’ was a welcome by-product, if not indeed desired outcome, of urban redevelopment. This interpretation expands dominant understandings of one of the seminal redevelopment projects of twentieth-century São Paulo, particularly how that project contributed to the myth of São Paulo as a non-Black metropolis as well as the city's enduring racialised sociospatial inequalities.

The Remedies, to 1938: Black Liberation through Abolition and Memorialisation

On the morning of 10 June 1883, the 45 enslaved people listed in Figure 1 received manumission certificates in front of the Church of the Remedies. The head of the Remedies brotherhood, Antônio Bento, had most likely secured their formal freedom. In the meeting of the brotherhood the week following, Bento requested that ‘in today's minutes be inscribed the list of those manumitted, so that all of time can attest’.Footnote 10 The members granted the request, and the names were listed alongside those of their former owners as well as the notary that held their freedom papers. The 1883 event reveals the core elements of the Black liberation project based at the Remedies: the formal abolition of slavery, the public condemnation of enslavers, and the memorialisation of those who had succumbed to, survived and/or worked to dismantle enslavement and racial violence.

Figure 1. Manumissions, Church of the Remedies, 1883

Source: A Redempção: Folha comemorativa da abolição do captiveiro, 13 May 1899, p. 8.

The development of the district surrounding the Church of the Remedies, Liberdade, was inextricably linked to the abolitionist campaign in the 1880s. In the mid-nineteenth century, however, the region's linguistic and material landscapes were organised by markedly different names and practices. In 1850, the place later designated Liberdade consisted of two plazas connected by a street (one block long) running north−south (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Original Liberdade Region in the City of São Paulo, 1850

Source: Gastão Cesar Bierrembach de Lima, ‘Planta da cidade de São Paulo, 1850’, Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo.

In 1850, the label printed on the map for the northern plaza in this region was ‘7 September Square (Pillory)’ (‘Largo Sete de Setembro (Pelourinho)’). The first part of the name commemorated the date in 1822 when Pedro I, Prince of Brazil, declared independence from Portugal. The parenthetical ‘Pillory’ referenced the alternative name for the square, which had served as the epicentre of public punishment in São Paulo. On the same 1850 map, the southern square was labelled ‘Hanging Square’ (‘Largo da Forca’) and ‘Hanging Hill’ (‘Morro da Forca’). The punishment and execution of enslaved African descendants and convicted people in São Paulo took place in these spaces. On the adjacent block to the east of the Hanging Square was the ‘Our Lady of the Afflicted’ (‘Nossa Senhora dos Afflictos’) chapel and cemetery, dated 1786. This common grave was the first public cemetery in São Paulo and served as the burial grounds for African and African-descendent enslaved people.Footnote 11

The label ‘Liberdade’ appeared on official maps for the first time in this region in 1868 through the renaming of Rua da Liberdade, or ‘Freedom Street’, which connected the two squares.Footnote 12 By 1877, the earlier names for those squares had been removed from maps: ‘Pillory’ had been dropped from ‘7 September Square’, and ‘Hanging Square’ had been renamed ‘Freedom Square’.Footnote 13 Between 1868 and 1877, therefore, the region gained the place names that would survive into the twenty-first century. The contemporary boundaries of the Liberdade district are more expansive than this earlier space, which I describe in the following as the ‘original Liberdade’ (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). This territory was the first place in the city of São Paulo where ideals of independence and freedom were inscribed in the linguistic landscape. Those lofty principles were projected onto a region long defined by racialised violence, torture and death.

Figure 3. Key Sites in the Original Liberdade: Antônio Bento's Home, the Praça da Liberdade, and the Church of the Remedies

Source: Map by author. Basemap from ‘Mapeamento 1930 – SARA’, GeoSampa, www.geosampa.prefeitura.sp.gov.br.

Various narratives circulate about the origins of the place name ‘Liberdade’. Some describe it as popularly given in the early nineteenth century, well before it appeared on official city maps. One story holds that the name referenced the freedom that souls gained as individuals condemned to death were executed in the ‘Hanging Square’. Another popular narrative points to the thrice-failed hanging of a defiant soldier named Francisco Chagas, or Chaguinhas, who in 1821 nearly escaped death and became a saint of the local Chapel of the Afflicted.Footnote 14 Records also indicate that in the middle of the nineteenth century free and enslaved Africans and their descendants in São Paulo were already pursuing antislavery activities in the original Liberdade. A group of freed people, for instance, founded a samba group, named the Zouavos, in the 1850s in the neighbourhood that advocated for slavery's abolition.Footnote 15

The original Liberdade became a hub, however, of Black liberation activities in São Paulo during the abolitionist campaign in the 1880s. The most prominent figure of that campaign in São Paulo since the 1860s was lawyer Luís Gama. After Gama's death in 1882, magistrate Bento took a leading role in organised antislavery activities. The brotherhood based at the Church of the Remedies, which Bento had led since 1880, became a base for abolitionist efforts. The Remedies brotherhood originally incorporated as a formally Catholic lay fraternal order in 1836. Black liberation efforts had figured into the life of the brotherhood since its inception. The organisation's founding charter, for example, stipulated that, on occasion of the annual celebration of the church's saint, any leftover financial resources ought to be applied ‘to the liberation of a captive’.Footnote 16

Bento invoked the Remedies’ history of Black liberation in his early organising efforts. In a brotherhood meeting in 1882, for instance, Bento called for the members to ‘follow the beautiful lead of their founders’ by signing a petition that he had composed to the Brazilian emperor against the imperial statute that sanctioned the whipping of enslaved people.Footnote 17 Given the proximity of the Remedies church to the pillory in São Paulo, the members of the Remedies brotherhood had likely witnessed first-hand instances of such violence against the enslaved. Not surprisingly, all brotherhood members present at the 1882 meeting signed the petition, an act that marked the intensification of the Remedies’ formal involvement in the abolitionist campaign.

In the early 1880s the abolitionist campaign in São Paulo shifted strategies from manumission efforts within the legal system to direct abolition by force.Footnote 18 If not the sole architect of this shift, Bento played a principal part putting it into practice. He organised the ‘Caifazes’, a collective composed of freed people, enslaved persons, immigrants, artists, journalists, lawyers and masons, which was headquartered at the Church of the Remedies. Explaining the group's composition and strategy, historian Emília Viotti da Costa writes: ‘[T]he Caifazes did not content themselves with denouncing the horrors of slavery in the press. The printing press of their journal, A Redempção, constituted a legitimate revolutionary nucleus, where members of the brotherhood of the Nossa Senhora dos Remédios church gathered, a majority being “working-class Blacks”.’Footnote 19

The Caifazes’ Black liberation project in the 1880s stretched both east and west into the province of São Paulo as members encouraged mass flight from plantations and resettlement in the capital city or in quilombos. The Caifazes’ antislavery campaign also included the forcible freeing of enslaved people within the city of São Paulo. In an interview with urbanist Raquel Rolnik, Black-movement leader Francisco Lucrécio recalled that:

[…] where today is the Ladeira da Memória, there was an auction site of Black slaves. When the Irmãos da Alma [Soul Brothers] knew the slaves would go to auction, they organised a march dressed in purple clothes with torches in their hands. They left the [Remedies] church, descending Riachuelo Street and when it was time for the auction they let loose. The torches became clubs. Then they stole the Blacks and took them to the quilombo of Father Felipe, up in the mountains. He knew the trails in the forest that led to Jabaquara.Footnote 20

The auction site that Lucrécio references here sat just a few blocks west of the Church of the Remedies. The similarities between the Caifazes’ project and the antislavery fight in the United States led historian Kim Butler to characterise the network they constructed as Brazil's Underground Railroad.Footnote 21

In the 1880s the original Liberdade also served as a stage for the dramatisation of the violence of slavery. Castro Alves’ antislavery poem ‘Slave Ship’ was set to music and performed at least twice in the 1880s in São Paulo. One of the performances occurred at the São José Theatre, a block north-west of the Church of the Remedies.Footnote 22 Other performances targeted an audience broader than the theatre-going public. In the 1880s the Caifazes rescued a recently tortured, enslaved person from the interior of the province and transferred him to the city of São Paulo. Bento then placed him at the front of a religious procession led by the members of the Remedies brotherhood. The scene was recorded by Antônio Manuel Bueno de Andrada, a friend of Bento and abolitionist sympathiser:

Among the saints on the processional floats, suspended on long rods, appeared instruments of torture: shackles, yokes, scourges, etc. In the front, beneath the image of crucified Christ, the miserable captive walked unsteadily and vacillating […] The impression on the city was profound. The police did not dare impede the march of the popular mass […] Everyone felt profoundly disturbed, except for the wretched, tormented Black man, whose pains had made him mad.Footnote 23

Exhibiting the violence of enslavement through the tortured man, the Caifazes dramatised the moral campaign against slavery and sought to elicit public support for formal abolition.

In parallel to encouraging mass flight and garnering public support for abolition, abolitionists based at the Remedies church also assembled and organised a material archive that would form the basis of the museum dedicated to the enslaved. In an issue of O Novo Horizonte, a newspaper from São Paulo's Black press, journalists remembered the place: ‘In the vestry of the Church of the Remedies, [Bento] organised a museum with instruments of the martyrdom of slaves, which were presented with the following label: “All these instruments are authentic and were used.”’Footnote 24 Journalist and Frente Negra Brasileira (Brazilian Black Front, FNB) leader José Correia Leite similarly recalled that ‘The church had a museum of instruments of slave torture.’Footnote 25 Viotti da Costa wrote that there were ‘instruments of torture like hooks, irons, chains, found by the members of the brotherhood’.Footnote 26 In an 1899 commemorative edition of the Caifazes’ antislavery journal A Redempção, one author recounted that ‘the Remedies brotherhood has precious treasures, the collection of irons taken from the enslaved, which the Paulista Museum would not be able to exhibit’.Footnote 27 The final comment emphasised the distinctiveness of the Remedies’ collection in comparison to one of the city's most eminent patrimonial institutions.

In the years following formal abolition in 1888, the Remedies museum to the enslaved preserved the material realities of racial violence, enslavement, torture and punishment alongside the material and linguistic elements of the original Liberdade that indexed triumphalist narratives of abolition, including the place name ‘Freedom’ itself. Creating and preserving this museum represented the significance of remembering and memorialisation to the Remedies abolitionists’ Black liberation project. The original Liberdade and the Remedies specifically also served as centres of emancipation commemorations beginning in the earliest years after formal abolition. In May 1889, for instance, O Estado de S. Paulo recorded the following:

The day before yesterday, in São Paulo the commemorative festivities for the 13th began. Diverse jongos of Blacks, in great joy, covered Liberdade Square and Liberdade Street, stopping various times in front of Dr Antônio Bento's house. At the side of the beloved abolitionist's house, they raised an elegant bandstand, where the Remedies band played during the 12th and 13th.Footnote 28

These celebrations would continue every year into the 1930s, even in the face of official efforts to suppress them. An article in an 1897 commemorative edition of A Redempção, for instance, noted that the local police captain had forced the 13 May celebration to end at ten o'clock. The author critiqued the captain for taking issue with ‘the dances that the freed people have grown accustomed to performing once per year’ while not attending to the ‘constant robberies that take place in the south of Sé, which even the newspapers have grown tired of reporting because there are so many’.Footnote 29 Correia Leite noted that even beyond the 13 May celebrations, the Remedies and the adjacent João Mendes Plaza became ‘points of concentration for many Black people’.Footnote 30

The Remedies and the original Liberdade broadly were also key sites for formal political organising by Black residents of São Paulo. The FNB headquarters itself sat two blocks south of the Remedies on Liberdade Street at number 196, across from the former Hanging Square.Footnote 31 The FNB coordinated 13 May celebrations in the 1930s, which commenced at the Remedies church. The decisions to base the FNB in Liberdade and to begin 13 May commemorations at the Church of the Remedies indicate efforts to link historical and then-contemporary Black liberation struggles through memorialisation and political action.

In addition to providing social-service programmes, the Liberdade-headquartered FNB also advocated against policies and practices of racial discrimination. For instance, FNB organisers in the early 1930s redoubled earlier efforts to overturn the exclusion of Black people from São Paulo's police force, the Civil Guard.Footnote 32 Correia Leite discussed this issue in the following, likely fictionalised, scene:

At the door to a bar, a Black man already of a certain age, half drunk, extends his flattened, calloused hands to a civil guard, an immigrant, with blond hair, eyes like a cat, a majestic prowess like a giant.

‘Look at this’, the Black man said. ‘This is 50 years behind the plough. Half a century! Half a century! My youth, my blood, my sweat. Hoe, shanty, coffee plantation, I left everything in the ground. Afterwards, 13th May. For years, I would samba on Liberdade Street, in front of Antônio Bento's house. I drank a lot. 13th May. You do not understand any of this. Look at my hands. I am free, young man. Let me drown myself in booze. I am free. It seems incredible. And Blacks can't even be civil guards …’Footnote 33

The freedman here critiques the failed promises of abolition and persisting inequalities through the exchange with the White immigrant, a stand-in for the ‘free’ labour valorised by São Paulo politicians and planters as the country's future beyond abolition. The freedman engages the immigrant as a personification of that historical process and argues for his rights, including by invoking his participation in abolition celebrations at the Remedies in the original Liberdade. The geography in his plea casts that region as a site of memory for the project of formal abolition as well as a mournful, contemporary representation of the continuities of racialised inequalities following the formal end of slavery.

The Church of the Remedies also appeared prominently in author Paulo Cursino de Moura's São Paulo de outrora (1932). In a section titled ‘The Pillory’, Cursino de Moura depicts Pai João, an archetypal formerly enslaved man in Brazilian folklore, standing in front of the Church of the Remedies.Footnote 34 Scanning the church up and down and peering into the adjacent square, he looks for a sign with the square's name, which he is unable to read. He asks a passer-by, who tells him that it is the 7 September Square. ‘Well then, they changed it’, he responds. ‘Here was the Pillory Square.’ He proceeds to record other changes in the surroundings: ‘The old Black man did not recognise the local place … Everything had changed.’Footnote 35

While invisible in material space, Pai João recalls the former pillory with acute detail: ‘A pillar of crude stonework. Solid stones, where two large rings, cemented into the block, hung. Underneath, chains flowing, like snakes, on the flooring, a little taller than the height of the road, forming a type of stage.’ He also comments on how that spatial history had been buried: ‘The pillory disappeared. It's good. The memory of the past is erased in the popular soul.’Footnote 36 A personification of that buried and disappearing past, Pai João also represented the persistence of memories of racialised violence in the original Liberdade and adjacent to the Remedies church in the 1930s.

Cursino de Moura published this history in 1932, at the beginning of a transformative decade of urban redevelopment in the region surrounding the Remedies. In that first edition the author noted the changes that had already reshaped the original Liberdade, with one significant exception:

[…] there was sanctuary […] in other abolitionists’ farms, in modest people's homes and in churches. At the Church of the Remedies, at [the Church] of Misericórdia, in the square of that name (demolished in 1888, coinciding with the abolition law, as if to say – ‘I am no longer needed’) and at [the Church] of São Gonçalo. The oldest relic of the times gone by, that the pickaxe of progress has to date still respected – the Church of the Remedies – solemnly attests to the protection of slaves.Footnote 37

Writing in the early 1930s, the refuge of the Church of the Remedies seemed secure from the ‘pickaxe of progress’. The fixture served as the point of reference for Pai João, representative of a generation for whom the memories of the local space remained acute. Cursino de Moura's allegory served as a type of prose memorial to counter the forgetting that would accompany the razing of the Remedies and other sites meaningful for African descendants in the original Liberdade in the decades following.

In the 1930s, the Church of the Remedies came to occupy a prominent place in first drafts of Brazil's official national patrimony. Mário de Andrade, the famed modernist, was instrumental in creating Brazil's first federal institution focused on historical and artistic patrimony, the Serviço do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional (National Historic and Artistic Heritage Service, SPHAN). In 1937 Andrade submitted a report to the director of SPHAN concerning ‘architectural monuments of historical and artistic value’ that he argued deserved ‘federal preservation’.Footnote 38 Andrade recommended eight sites in the city of São Paulo, including the Remedies, which he described in the following:

It belongs to the Brotherhood of Our Lady of the Remedies and was built on 17 July 1812. The date of the church's establishment is not known at present. The frontispiece on the current façade of the building, which is covered with blue tiles, says 1812. The abolitionists of 1888, led by Luís Gama and others, met in the church. Photos of the façade can already be found in the central headquarters of SPHAN.Footnote 39

Andrade included a description like this for each of the eight sites, providing the rationale for their historical and artistic value. For the Remedies, he highlighted the pivotal links between the church and the abolitionist campaign (historical value) and the tiles on the façade (artistic value), which were atypical in São Paulo. The Church of the Remedies was shortly thereafter featured in the first issue of the nationally focused SPHAN journal, published in 1937.Footnote 40 Of the eight sites Andrade recommended for preservation in São Paulo, the Remedies was the only one ultimately demolished.Footnote 41

The preservation of the Remedies, including its potential designation as official national patrimony by SPHAN, would have proved meaningful, most especially in preventing the demolition that would commence the year following Andrade's recommendation. At the same time, such recognition would have followed nearly 50 years of memorialisation work already conducted by former abolitionists at the Remedies. While the compilation of a national material memory became an institutionalised, state practice in the late 1930s, former abolitionists had, since the 1880s, pursued their own spatial project of remembering that produced the Remedies church and museum as monuments to the enslaved and freed as well as to the ongoing project of Black liberation, more broadly.

‘The Pickaxe of Progress’: Demolishing the Remedies

In 1929 construction workers unearthed a common grave while installing a new telephone cable near the Church of the Remedies. Journalists from the newspaper Diário Nacional, whose headquarters sat across the street from the site, chronicled the findings in an article titled ‘In Excavations Made Surrounding the Church of the Remedies, Human Bones Were Encountered: Stories Say That in This Place, a Century Earlier, the Members of the Religious Brotherhood Were Buried.’ The article recounted the brotherhood's 1880s antislavery campaign. ‘The role of the Remedies brothers’, the author explained, ‘was most important to the abolition campaign, the church becoming a legitimate refuge against slavery. United in life by religious faith and by the ideas that they put forward, the brothers remained united after death, in the common grave.’Footnote 42

While the Diário Nacional journalist concluded that the ‘skeletons found yesterday were the last resistance to the expansionist project of progress’, the new telephone cable in fact signalled the beginning, not the end, of planning and executing progress in this significant region.Footnote 43 The year following the excavation, urban planner and head of São Paulo transportation and public works, Francisco Prestes Maia, would publish Estudo de um plano de avenidas para a cidade de São Paulo (Study of a Plan of Avenues for São Paulo, hereafter referred to as the ‘Avenues Plan’).Footnote 44 In this ambitious redevelopment project Prestes Maia projected a ring road through the Remedies communal grave along with the Church of the Remedies and the museum to the enslaved. The demolition of the Remedies church and museum occurred in 1942–3, four years after Prestes Maia had been appointed to head São Paulo's city government (a position he held until 1945). The demolition generated a surprisingly durable collective amnesia about this site in the city of São Paulo broadly and within the specific geography of the city's early twentieth-century ‘Black zone’, in particular. In the following sections I present evidence that this amnesia was not incidental. Instead, the demolition of the Remedies comprised part of a planned project of forgetting, animated, though perhaps not exclusively motivated, by anti-Black racism.

The realisation of key elements of the Avenues Plan in the 1930s–1940s represented one of the most ambitious and influential mid-twentieth-century redevelopment projects in the city of São Paulo. An early draft of that plan was released in 1926, when Prestes Maia and fellow urbanist João Florence d'Ulhôa Cintra published an outline for the redevelopment of the city's central road network. Their proposal presented a version of a ring road north of the Sé Cathedral.Footnote 45 This original plan would have spared the Remedies church and museum (see Figure 4). Four years later, in the much-expanded and comprehensive Avenues Plan, Prestes Maia shifted the ring road south of the Sé Cathedral (see Figure 5).

Figure 4. 1926 Plan for the Ring Road Drafted by Prestes Maia and Ulhôa Cintra

Note: Shaded region north of the Sé Cathedral shows the planned trajectory of the ring road that would have spared the church.

Source: Map by author, adapted from Prestes Maia and Ulhôa Cintra, ‘Um problema actual: Os grandes melhoramentos de São Paulo’.

Figure 5. Map of the Completed Ring Road in 1945, Showing the Alternate Trajectory South of the Sé Cathedral

Source: Map by author, adapted from Prestes Maia, Os melhoramentos de São Paulo.

This shift accompanied a substantial expansion of the João Mendes Plaza, which would become a crucial stretch of the ring road running along an approximately east−west axis. This revised plan also entailed the linking of João Mendes Plaza with 7 September Square (the former Pillory Square), which would establish a wider road linkage between the Sé and Liberdade districts running south to Liberdade Avenue. This expanded, connected plaza, square and avenue – which formed a ‘T’ shape – would serve as a central transportation node for streetcars and the city's growing network of bus transportation. Realising this ambitious plan would require the demolition of a series of structures in these blocks, including the Remedies church and museum and an adjacent building the brotherhood owned.

Prestes Maia's appointment as mayor in 1938 gave him the institutional authority with which to execute key components of the Avenues Plan. Redevelopment of the João Mendes Plaza and 7 September Square became an early focus of his administration. In February 1939 Prestes Maia signed a decree ‘declaring for public use, to be expropriated, all of the block between the roads 11 August, Irmã Simpliciana and plazas João Mendes and 7 September ’.Footnote 46 This expropriation decree encompassed over two dozen structures; however, a press article about the decree singled out the planned demolition of the Church of the Remedies: ‘A curious detail … with the expropriations to be made, one of the oldest Catholic temples of the city, the Church of the Remedies, will disappear.’Footnote 47 The brief but sympathetic aside reveals the historical significance of the Remedies church among the buildings slated for demolition in this area.

The leadership of the Remedies brotherhood received formal notice of the expropriation and convened a meeting in early March 1939 to discuss their next move. Their discussion centred on the amount that they understood the municipal government had committed to the expropriation: 3,000 contos (approx. US$177,074).Footnote 48 The leader of the meeting and 30-year head of the brotherhood, Carlos Corrêa de Toledo, found the sum incommensurate with the market value of properties in the area. He cited a prior episode from 1929 when the municipal government had considered expropriation, during which the archbishop of São Paulo had estimated the market value of the church and attached building as at least 3,500 contos. Thirteen years later and amid a transformative redevelopment project that would raise local property values, the proposed sum fell well short of expectations.Footnote 49

While the expropriation amount figured centrally in the brotherhood's deliberations at the March meeting, they also kept the history of the church at the forefront of their conversation. Corrêa de Toledo, for instance, directly followed his reading of the expropriation decree with a historical overview of the brotherhood's role in the 1880s antislavery struggle, lauding the ‘great figures who passed through this place and left indelible marks through their religious and patriotic service’.Footnote 50 The brotherhood, no doubt, calculated the value of the church based on the local real-estate market as much as the place's historical significance to the abolitionist project and the memorialisation of the enslaved.

Perhaps surprisingly, the surviving record from the March meeting suggests that the brotherhood did not discuss a move to block the expropriation and demolition. They might have calculated that doing so would prove difficult, if not impossible, given the appointment of Prestes Maia to the municipal government and the authoritarian climate of the Estado Novo. The brotherhood's leader, Corrêa de Toledo, instead adopted a moderate negotiation stance that focused on the terms and not the fact of expropriation. He declined ‘numerous offers’ of assistance from lawyers willing to represent the organisation before the municipal government out of a desire ‘to carry out negotiations on totally harmonious grounds’. Fresh from the March meeting, Corrêa de Toledo felt ‘certainty [that] the municipal powers will be the first to recognise the high value of the real estate to be expropriated for the demands of urban progress’.Footnote 51

Some observers in São Paulo's mainstream press adopted a similar position, writing appreciatively about the church's historical significance while, at the same time, accepting the demolition as the perhaps lamentable but necessary price of progress. An article from March 1939 pointed to the traffic bottleneck in front of the church as a ‘serious threat to the future expansion of the metropolis’ before concluding: ‘Now, 218 years later, the traditional paulistano temple will disappear, in order to attend to the growth of the city's progress.’Footnote 52 Though noting the church was ‘one of the few monuments from the colonial epoch’, a February 1939 article conceded that ‘the old temple […] for necessities imperative to the development of the paulista capital, is, now, condemned to disappearance’.Footnote 53 A November 1942 article asserted that the church, ‘which in that stretch of the city represented old São Paulo’, would ‘open up space, under the pickaxe of urbanism, to the works devised by Mr Prestes Maia, works that in the short space of almost five years made our central capital among the most beautiful cities of Brazil and America’.Footnote 54 An article following the demolition concluded: ‘If, on the one hand, we lament the disappearance of “one more” of the city's historical patrimony, on the other hand we have to agree that the old temple, sitting at the narrowest of bottlenecks that disturbed traffic at the beginning of Liberdade Street, needed to be removed.’Footnote 55 While such articles gestured toward the church's historical significance, few described the specific connections to slavery, abolition or ongoing projects of Black liberation.

Other observers shared the high appraisal of the value of the church but, instead of accepting demolition as inevitable or necessary, worked to thwart it. These included the prominent cultural figures and city government employees Mário de Andrade and historian Nuto Sant'Anna, who had lobbied for the preservation of the Remedies even before Prestes Maia's appointment as mayor in 1938. After the expropriation decree in 1939, they continued to lobby against demolition. Andrade, for example, discussed the Remedies in correspondence with Luis Saia, an urbanist and ethnographer who would lead SPHAN's São Paulo district office from the late 1930s through to the 1970s. Both Mário de Andrade and Saia sent letters advocating for the preservation of the Remedies to Rodrigo Melo Franco de Andrade, SPHAN's director. In a letter to Mário de Andrade dated 7 March 1939, Saia wrote:

About the case of the Church of the Remedies, I also already sent a report to Rodrigo. I don't know if it will stave off the demolition. It's a complicated case, since a lot of work was already put into related expropriations, other construction work has already been carried out, all of this implicating the future demolition of the church. I proposed to Dr Rodrigo, if the demolition is indeed unavoidable, the budget for a complete model of the church to be made for SPHAN.Footnote 56

Saia's comments seem to draw on backroom conversations with urbanistic and preservation authorities. His observations suggest that already in early March 1939 – a week before the Remedies brotherhood had even held their first meeting to determine their response to the expropriation decree – the demolition was inevitable. The brotherhood's leadership itself may have also received this information through backchannels, which might help to explain their acquiescence to the fact, if not the terms, of demolition. Saia's proposal for a scale model of the church, additionally, demonstrates an early effort to imagine alternative modes of preserving the Remedies and the pasts that the brotherhood had memorialised.

The seeming inevitability of demolition did not, however, deter preservationists from continuing to make their pitch, including in São Paulo's mainstream press. Sant'Anna, for instance, wrote a 1942 article in Folha da Noite, titled ‘It Was the Headquarters of the Enslaved in São Paulo.’ The piece foregrounded the Remedies’ ties to enslavement and abolition and highlighted the proximity of the church to the former Pillory Square. Sant'Anna concluded with a direct appeal to urbanistic authorities: ‘In the face of all of these facts’, he surmised, ‘the demolition of the traditional Church of the Remedies is lamentable. I believe that, correcting a few urbanistic defects, the temple could be conserved.’Footnote 57 It is unclear whether those ‘defects’ referred to characteristics of the church or to Prestes Maia's plan for redevelopment at the João Mendes Plaza and 7 September Square. In either case, the historian clearly saw the Remedies church – even in 1942, with the levelling imminent – as both salvageable and worth saving, not incompatible with redevelopment.

Author Afonso Schmidt penned one of the most passionate and imaginative pleas for preservation. Schmidt's was one of the only articles from the mainstream press to directly reference the Remedies museum to the enslaved. In his overview of the place's history, Schmidt wrote: ‘Those who gained their freedom, by flight or by violence, brought their irons, as a pious offering, to the blessed church. The body of the church, little by little, became a museum of torture devices.’Footnote 58 Schmidt's piece drew on a first-person visit to the church.Footnote 59 Neither Mário de Andrade nor Sant'Anna mentioned the museum in newspaper articles or in records relating to SPHAN. Schmidt's unique mention of the museum may have been due to him being one of the few observers to visit the inside of the church and therefore become familiar with the museum's contents. It is also plausible that Andrade and Sant'Anna had visited the church but calculated that highlighting the museum would weaken the case for preservation with urbanistic authorities like Prestes Maia. They may have surmised that officials might be sympathetic to a monument to the abolition of slavery – the argument Sant'Anna made in the press – but repelled by a memorial that preserved material instruments and memories of racial violence.

In his appeal for preservation, Schmidt adopted a different approach that kept the material culture of the museum to the enslaved front and centre:

The Church of Our Lady of the Remedies cannot disappear […] It should be conserved, even if inside a glass case […] It is the Church of Our Lady of Abolition. Almost all countries preserve these antiquities: governments give them rights as national monuments. Do the same with the Remedies. Raze the block that hides it. Reform it. Encircle it with gates cast with the irons of the enslaved. But do not remove it from there.Footnote 60

Schmidt asserted that the contents of the museum should be dismantled, a suggestion that he, too, may have seen that memorialised material culture and the racial violence it symbolised as incompatible with São Paulo's modernisation. At the same time, his proposal that the irons should be melted down and incorporated into a gate surrounding the structure represents the transformation, rather than disappearance, of that material culture and, to an extent, the pasts symbolised therein. Though likely at odds with the wishes of those who had curated and preserved the museum to the enslaved, Schmidt's proposal did steer an imaginative and more reverent, if ultimately unrealised, middle course.

These impassioned appeals to stop the demolition of the Remedies did not ultimately persuade urbanistic authorities, who took control of the structure in September 1942. The Remedies brotherhood ultimately received between 1.2 and 1.4 million cruzeiros (approx. US$61,800–72,100)Footnote 61 in the expropriation: substantially less than half of what the leader Corrêa de Toledo understood the city government's valuation of the church to be in the March 1939 meeting. Two sources indicate that judicial authorities settled the final amount of the expropriation, suggesting that what Corrêa de Toledo had hoped would be a harmonious negotiation did not end up as such.Footnote 62

The municipal government may well have reduced their initial expropriation offer by half, a move that the brotherhood, which already found the original proposal of 3,000 contos / Cr$3 million wanting, would have likely found distressing. It is also possible that a city official communicated the expropriation cost of the entire block, rather than just the Remedies properties, to the brotherhood's representatives. The city government paid Cr$1.1 million for the other privately held building on the block, which together with the Remedies church and attached building would have brought the expropriation total to Cr$2.5 million. Costs associated with other expropriated buildings in the vicinity, or, perhaps, an expropriation cost associated with the municipal library that sat between the Remedies and the other privately held building, could have easily brought the total near Cr$3 million.Footnote 63

Whether either of these scenarios captures what took place, the expropriation ultimately left the Remedies brotherhood with less than half of what they had anticipated and, as noted above, substantially less than the valuation of the church that the archbishop of São Paulo had made in 1929. The brotherhood itself owned these properties, which likely served as a meaningful source of wealth generation and preservation. The reduced expropriation sum, combined with the increase of prices during wartime, were also consequential in hampering progress on the rebuilding of the church in the years following.

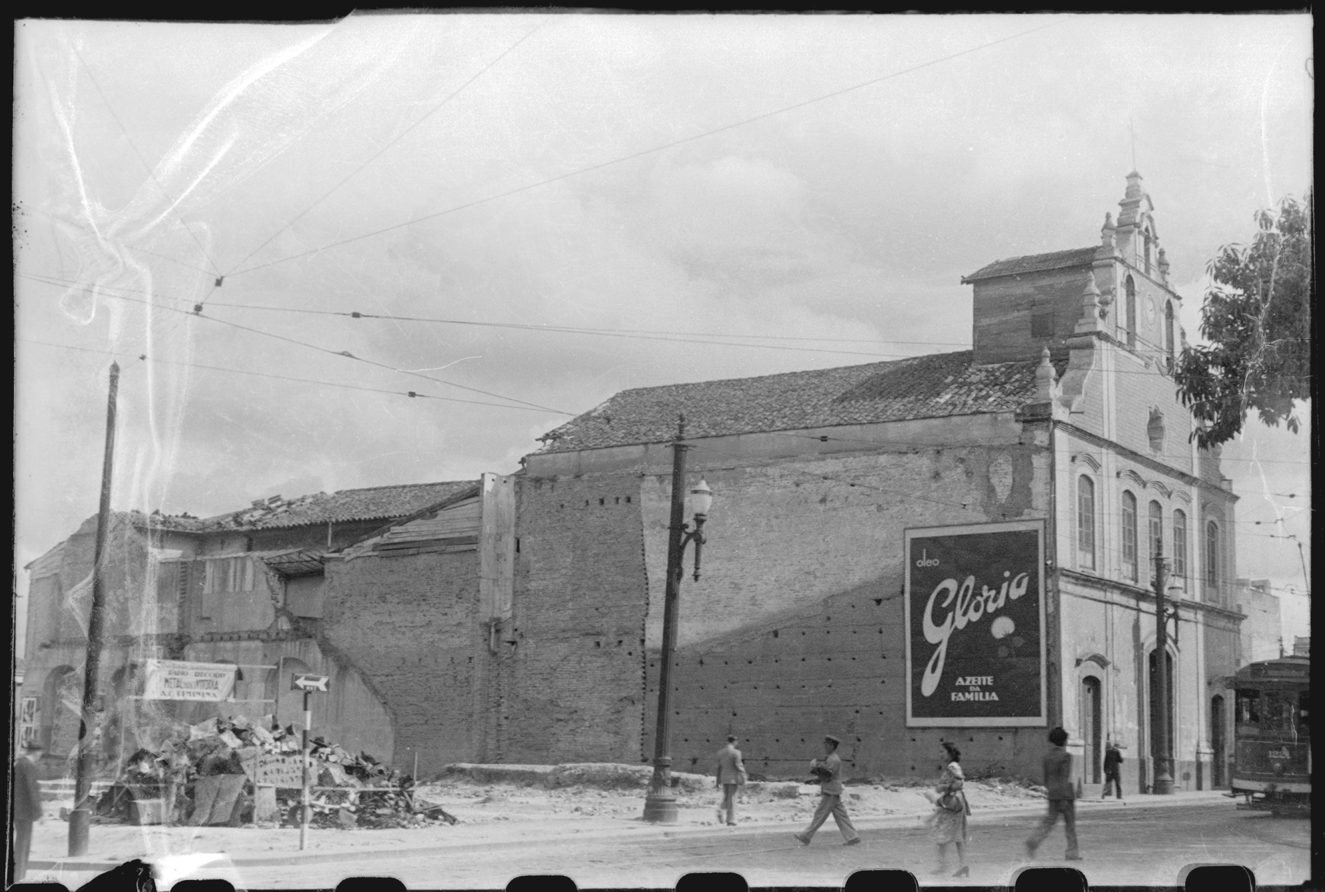

The demolition of the Remedies began in late 1942 (see Figure 6), drawing the attention of notable São Paulo residents. Modernist poet Oswald de Andrade, for instance, wrote in his journal of being at the Remedies on the day of demolition.Footnote 64 The levelling spanned months, in fact, and was quickly followed by the work to construct a station on the streetcar line at 7 September Square. One source suggests that Prestes Maia moved into his office in City Hall – a few blocks north-west of the demolition site – to be nearby in case any complications arose.Footnote 65 The anecdote illustrates the significance that redevelopment in this stretch of the Avenues Plan held for Prestes Maia.

Figure 6. Photograph of the Partially Demolished Church of the Remedies

Source: Photo by B. J. Duarte, 1942, Acervo Fotográfico do Museu da Cidade de São Paulo.

While the church was razed in 1942–3, not all of the structural elements and objects within the Remedies were ground to dust. São Paulo's archbishop issued a decree in late 1942 with instructions on how to ‘reduce the […] temple of the Remedies to profane use, so that it could be demolished’. This decree mandated that ‘All of the objects and sacred implements should be removed by the Brotherhood of the Remedies and stored in a secure place, and recorded in an inventory that will be registered in the minutes of the brotherhood and in this Metropolitan Curia.’Footnote 66 The contents of the museum to the enslaved may well have been listed in this inventory, but I have not located records to confirm as much in documents from the brotherhood or in the curia. Other sacred material objects from the Remedies, however, were ultimately transferred to the reconstructed church and/or local museums.

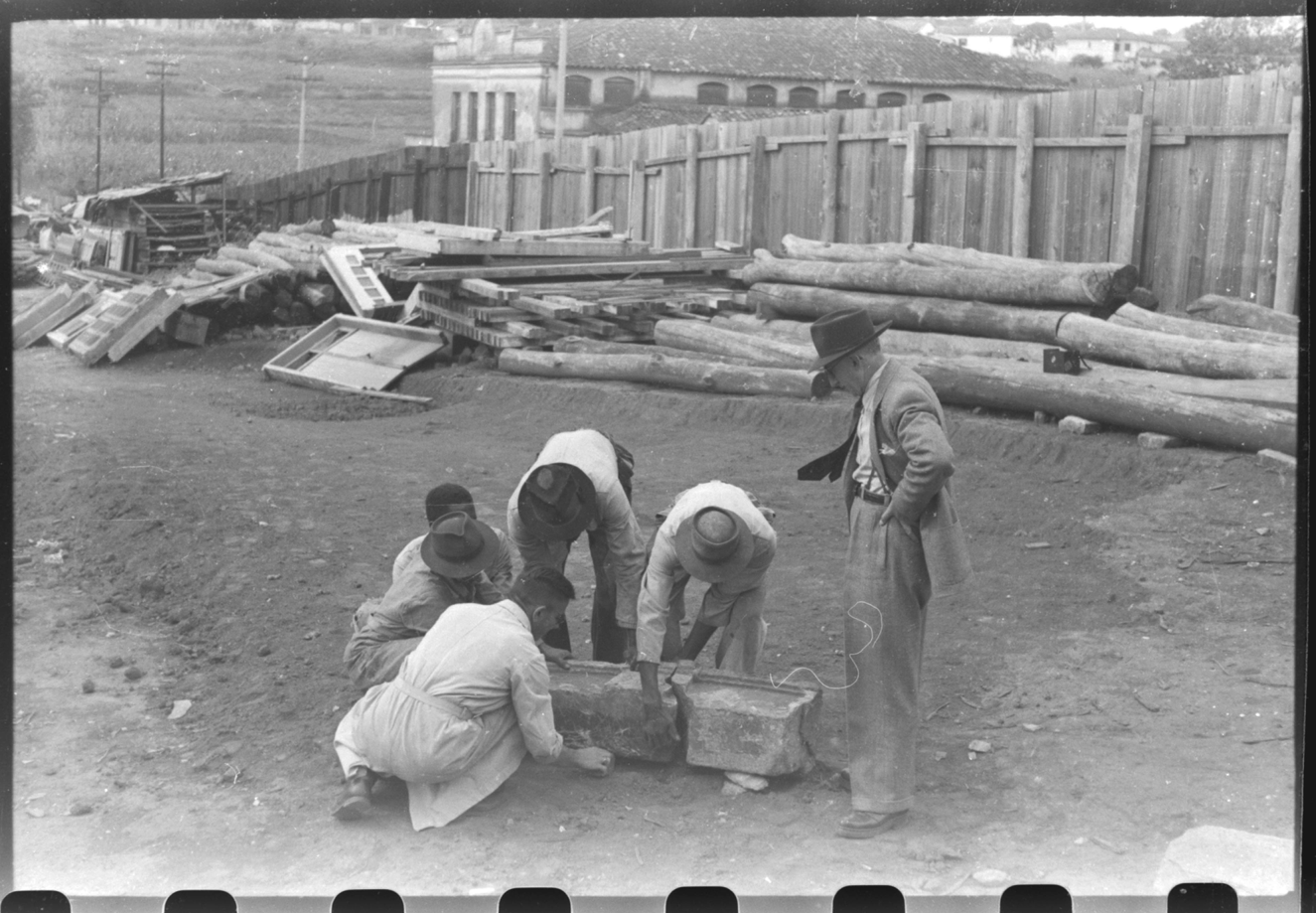

Outside parties took an interest in salvaging some materials from the Remedies. Benedito Junqueira (B. J.) Duarte, the head of the iconographic section of the municipal Department of Culture, captured the piecemeal dismantling of the Remedies in a series of photos. Duarte's photos from 1944 reveal that doors, stones and wooden beams from the Remedies had been transferred to a municipal government storage facility. Sant'Anna lobbied the city government to establish a permanent exhibition to the Remedies comprised of these salvaged materials in the Ipiranga Museum.Footnote 67 One of Duarte's photos shows Sant'Anna observing workers at the storage facility reassembling the stone from above the Remedies front door (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Photograph of Nuto Sant'Anna and Workers Reassembling a Stone from the Demolished Church of the Remedies.

Source: Photo by B. J. Duarte, 1944, Acervo Fotográfico do Museu da Cidade de São Paulo.

The Remedies brotherhood began the effort to reconstruct the church in quick order after demolition. They had acquired land in the nearby Cambuci neighbourhood in early 1943 and, by October, had laid the cornerstone for the new church. However, the increased cost of construction materials during wartime hampered the effort to rebuild, as a 1946 article in O Estado de S. Paulo explained: ‘[T]he construction had to withstand the incredible and absurd inflation of the materials most necessary for its progress, such as iron, wood, bricks, etc. Result: the money didn't suffice. The project stopped midway.’Footnote 68 The church would ultimately be completed; however, the location of the objects from the museum to the enslaved remains unknown into the twenty-first century.

Prestes Maia's Value Judgement and Placing Anti-Black Racism

An extraordinary needle in the archival haystack furnishes revealing insight into Prestes Maia's perspective on the demolition of the Remedies. In late 1942 or early 1943 Prestes Maia submitted an extensive report with an update on urban redevelopment projects to the São Paulo State Assembly. In structure, tone and detail, the exhaustive document mirrored the Avenues Plan itself. In the early pages of the report, he addressed the construction of the ring road in the proximity of the Remedies church and museum: ‘The great expansion of the João Mendes Plaza, extended all the way to Tabatinguera Street, required almost 3 million cruzeiros of expropriation expenditures, including the Church of the Remedies, of debatable historical and artistic value, and whose location strangulated the best passage to the neighbourhoods of Glória and Liberdade.’Footnote 69 Prestes Maia rarely spoke extemporaneously about his projects. He let his voluminous, erudite and polished technical publications do most of the talking. That pattern makes this six-word value judgement of the Church of the Remedies an unusual and illuminating window into the ideology that animated the decision to demolish the Remedies church and museum and, I suggest, the Avenues Plan more broadly.

Prestes Maia's interpretation of the ‘debatable’ value of the church cannot reasonably be attributed to ignorance about the unequivocal value that the place held for many São Paulo residents, especially, but not exclusively, those of African descent. In the nineteenth century, the church had been deemed of significant enough historical value for inclusion in Militão Augusto de Azevedo's collection of photos of São Paulo, snapped between 1862 and 1887 (see Figure 8). In the more contemporary context of the 1930s (and as noted above), articles about the history of the church had circulated in São Paulo's mainstream press and, in 1937, in SPHAN's magazine (which had a national scope). What's more, Prestes Maia had a well-worn copy of Cursino de Moura's São Paulo de outrora in his personal library – the book with the story of the archetypal Pai João described above – wherein his few annotations revealed an interest in the history of African descendants in Brazil, in particular.Footnote 70

Figure 8. Church of the Remedies, Militão Augusto de Azevedo, circa 1887

Source: Acervo Instituto Moreira Salles.

We would also expect that Prestes Maia was aware of, if not directly involved in debates about, the preservation arguments made by figures like Mário de Andrade. Indeed, the specific vocabulary that Prestes Maia used in his appraisal – ‘[…] historical and artistic value’ – echoed Andrade's language from the 1937 report (‘architectural monuments of historical and artistic value’) about sites in the city of São Paulo worth federal preservation. Prestes Maia's reference to value in that 1942−3 document also recalls the centrality of that word in the deliberations of the Remedies brotherhood from the March 1939 meeting. This similitude suggests that Prestes Maia's appraisal may have been a direct rebuttal to the arguments that both the preservationists and the brotherhood had put forth about the historical and artistic value of the Remedies. The contrast between the superlative, widely known value that the Remedies held for many in São Paulo and the ‘debatable’ value with which Prestes Maia described it is striking.

The value judgement in the report is also significant because it was rather unnecessary. Prestes Maia could have limited his comments to the latter half of that sentence, which, reasonably, emphasises the transportation bottleneck in front of the Remedies that strained access between the districts of Sé and Liberdade. Or, alternatively, he might have acknowledged that the church indeed held great significance for many in São Paulo while lamenting that, nonetheless, its location necessitated demolition. Many journalists in São Paulo's mainstream press – and, recall, even the leadership of the brotherhood itself in its first meeting after the expropriation decree – adopted this position. Alternatively, still, we might wonder why, among the dozens of structures demolished for the expansion of the João Mendes Plaza, Prestes Maia mentioned the Remedies church at all. Why single out the Remedies and explain the logic of its demolition through this subtle, yet unmistakably dismissive, appraisal?

Prestes Maia's value judgement of the Remedies becomes even more curious in light of his interest in the blue tiles that covered the façade of the church. Mário de Andrade referenced these tiles in his 1937 report as evidence supporting the artistic value of the Remedies. Indeed, though common in other regions in Brazil, such ornamentation was rare in São Paulo. The Church of the Remedies may have been, in fact, the only building in the city with its façade ornamented thusly.Footnote 71 One source indicates that Prestes Maia sought to acquire these tiles and requested them from the brotherhood. The brotherhood's members refused. The tiles were initially given to a plant nursery in the park in Ibirapuera and, supposedly, ‘never heard of again’.Footnote 72

Remarkably, 150 of these tiles today hang in the municipal government's library dedicated to architecture and urbanism, which bears the name of Prestes Maia. He coordinated the construction of this library in 1963, and since then it has housed an extensive collection from his own personal archive of books, technical documents and objects. The label accompanying the tiles indicates that they were restored in 1973, eight years after Prestes Maia's death. It is not clear to me how the tiles ended up here, and what role, if any, Prestes Maia might have played in that process. Other tiles from the façade ended up in the São Paulo Museum of Sacred Art and the collection of the Museum of the City. Whatever the explanation for how the tiles landed in the library named for Prestes Maia, his wish to acquire them starkly contradicts his own appraisal of the supposed ‘debatable historical and artistic value’ of the church and museum.

While we might find Prestes Maia's comments and actions suspicious to the point of duplicitous, does this collection of evidence support the conclusion that anti-Black racism motivated the demolition of the Remedies? Such a conclusion is not prominent in the two dominant threads of criticism of the Avenues Plan, which instead concentrate on architectural patrimony and population displacement, respectively. Both lines of criticism present the Avenues Plan as indiscriminate – not motivated by or involving racialised social difference – in its destructive and negative impacts.

A 1942 article about the demolition of the Remedies, written by the director of the São Paulo State Archive, Lelis Vieira, for instance, reflects the first thread of Avenues Plan criticism. He wrote: ‘It is clear that civilisation does not respect the city; that progress ignores everything; that comfort is more important than traditions; that so-called aesthetics destroy museums; that urbanism spoils eaves, mutilates mouldings, punctures blinds, puts out light fixtures, and achieves the perfection of turning a village into a capital.’Footnote 73 His criticism lambasted modern architecture and urbanism for its indiscriminate destruction of the city's colonial built environment. A similar sentiment appears in a later article from 1946: ‘[… for] the expansion of the place and decongestion of traffic, it was necessary to sacrifice nothing less than this historical patrimony of the city, and, with it, the entire block’.Footnote 74 These criticisms focused on the confrontation between modern architecture and urbanism with earlier urbanistic patterns and building styles, especially religious architecture. We would expect to find comparable criticisms of modern architecture and urbanism in disparate urban contexts. Indeed, the patrimony vein of criticism was not particular to the case of the Remedies or even to the city of São Paulo.

With more attention to the social implications of the Avenues Plan, other observers have critiqued the displacement that demolitions caused. For instance, Luiz de Anhaia Mello, an architect-urbanist and contemporary of Prestes Maia, criticised the latter's redevelopment projects in 1945 for leaving an estimated 150,000 people homeless.Footnote 75 More recently, scholars such as Nabil Bonduki, Teresa Caldeira and James Holston have critiqued the displacement caused by the Avenues Plan and the sociospatial inequalities that redevelopment helped to (re)produce.Footnote 76 While these authors help to elucidate the roots of São Paulo's pronounced contemporary inequalities in the Avenues Plan, the case of the Remedies supports an expanded critical interpretation of this seminal modernisation programme in São Paulo that foregrounds questions of racial prejudice and racialised inequalities.

The decision to demolish the Remedies went beyond the logic and criteria of transportation planning. Historian Benedito Lima de Toledo gestures toward this conclusion when he writes that Prestes Maia ‘wanted to demolish the Church of the Remedies – I do not remember his argument why – and arranged the grounds to do so’.Footnote 77 Lima de Toledo here implies that Prestes Maia desired to demolish the church and, subsequently, found an urbanistic basis to support doing so. While this analysis and Prestes Maia's six-word value judgement suggest that he wanted to demolish the church, what other historical context can help us to understand whether, again, this desire was motivated by anti-Black racism, specifically?

A productive parallel example to consider is the proposed demolition of the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of Black Men (Igreja Nossa Senhora do Rosario dos Homens Pretos), a Black brotherhood founded in 1711. Between 1903 and 1905 the City of São Paulo had expropriated and demolished the brotherhood's original church, which then relocated to the north-east of the old city centre at Paissandu Square.Footnote 78 In the 1930 Avenues Plan, Prestes Maia again set the municipal government's sights on the relocated church, asserting it should be demolished and rebuilt in the Barra Funda neighbourhood. In a map of his proposed demolitions from the Avenues Plan, Prestes Maia included the church in an open-ended, catchall category of projects related to ‘new alignments or modifications’. The church sat multiple blocks from the nearest avenue projected for enlargement and, therefore, was an oddly remote choice for demolition.Footnote 79

Prestes Maia, in fact, had no avenue-making plans for the site of the Rosary church. Instead, he intended to erect a monument to Duque de Caxias, a prominent military and political figure of nineteenth-century Brazil.Footnote 80 The significance of the Rosary church and Prestes Maia's proposal for replacement suggests that he desired to displace a significant centre of Black life in the city and construct, in its stead, a monument that celebrated a White historical figure. The proposed expropriation and demolition show how Prestes Maia's plan went beyond issues of transportation planning and urban amenities to encompass spatial projects relating to memorialisation. Prestes Maia would not succeed in the expropriation of the Rosary church, however, which remains at Paissandu Square through to the present.Footnote 81

Though sparse in the written historical record, some São Paulo residents commented on demolition episodes like those of the Rosary and the Remedies as directly involving anti-Black racism. For example, researcher Virgínia Leone Bicudo recorded the following observation from a Black resident about the proposed demolition of the Rosary church in 1945: ‘That attitude of prejudice in São Paulo is not exceptional – by the same motive, one thinks about the removal of the church of the Rosary from Paissandu Square, they say to erect a monument. Discussing the subject with a White Catholic, he told me: “It is necessary to clean that place, to remove the church from there”.’Footnote 82 The quote suggests that the discourses about, and the demolition of, buildings like the Rosary and the Remedies may have served as a concrete means through which Black residents of São Paulo could identify the racial prejudice and inequities that structure(d) paulistano society yet were frequently denied or veiled.

Analysing the proposed demolition of the Rosary and the successful demolition of the Remedies in the same frame supports an interpretation of Prestes Maia's project as animated, though perhaps not exclusively motivated, by anti-Black racism. This racism was veiled behind the discourse of urbanistic neutrality and the spatial memory politics embedded in the Avenues Plan, which held places prominently associated with, and often significant to, African descendants as representative of São Paulo's undesirable past. The Remedies brotherhood had memorialised those pasts through the museum to the enslaved. That memorialised material history was at odds, however, with the future-oriented spatial project of whitening, modernity and progress that Prestes Maia had outlined in the Avenues Plan and that various urban authorities had pursued in São Paulo over generations.Footnote 83 Demolition would serve to resolve that contradiction in 1942–3, paving the way for a collective forgetting in dominant memory about the histories of racial violence and Black liberation that the Remedies at once housed, symbolised and memorialised.Footnote 84

This argument builds on the work of earlier authors, especially Gabriel Marques, an African descendant whose compelling prose has received scant recognition by scholars. Marques witnessed the implementation of Prestes Maia's Avenues Plan first-hand, including as a resident of the street (Tabatinguera) that dead-ended into João Mendes Plaza.Footnote 85 He interpreted the significance of the Avenues Plan in the context of the redevelopment of the Largo da Memória (‘Memory Square’), the site of auctions of the enslaved in São Paulo, into the Praça da Bandeira (‘Flag Plaza’). Marques wrote: ‘Progress gave a new soul to the place. Progress even changed the name for the purpose, perhaps, of erasing the Black past.’ Marques understood the redevelopment of this site – both materially and linguistically – as a project that rendered African descendants and their histories invisible. As he concluded, ‘The truth is that nothing else records, today, what was, yesterday, that rough piece of paulistano soil […] They buried it beneath the asphalt.’Footnote 86

My interpretation of the Avenues Plan as a racialised spatial project of forgetting aligns closely with Marques’. Indeed, while throughout this article I present original evidence around the history of the Remedies church and museum (which do not appear in Marques’ writings), the argument I advance here follows and directly supports the supposition that he put forth – albeit somewhat delicately – 60 years ago. I expect that many other African-descendent residents of Liberdade and throughout the city of São Paulo held interpretations similar to Marques’ in the mid-twentieth century, even if their voices – like the Remedies itself – were buried in the decades following.

The Remedies in Context: (Un)Making Ethnoracial Space

In addition to the Remedies, urban authorities levelled other sites significant to, and prominently associated with, African descendants in this era in São Paulo and beyond. In the same year that demolition began on the Remedies, for instance, officials in Rio de Janeiro demolished the Praça Onze, a key site in the city's mythical ‘Little Africa’ region, for a new avenue.Footnote 87 Such demolitions support the conclusion that the destruction and reproduction of urban space served in the whitening project and in the maintenance of racialised inequalities in Brazilian cities, even if the geography of those inequalities has not precisely mirrored other ethnoracially diverse, highly stratified cities in the hemisphere.Footnote 88 Prestes Maia's six-word value judgement provides a uniquely incriminating bit of evidence to support this observation for the case of São Paulo, though we would expect that spatial authorities in other cities shared a similar ideology.

While the case of the Remedies points to broader patterns about the whitening project across urban Brazil, its demolition also helps to illuminate the singularity of the outcomes of that project in São Paulo. The demolition of the Remedies formed one front in the spatial project of forgetting in São Paulo that displaced or razed places with high populations of African descendants and/or prominent associations with slavery, racial violence, abolition and Black liberation. Elsewhere I chart other places razed in this project, such as the Saracura neighbourhood in the district of Bela Vista, which had the highest concentration of African descendants in the city at the time of its demolition for the construction of 9 July Avenue.Footnote 89 Despite its levelling, popular memories of Saracura have persisted, particularly through the Vai-Vai samba school, which remains headquartered in Bela Vista on the edge of the former Saracura neighbourhood.Footnote 90 Compared with Saracura, fewer traces of the original Remedies survived in the decades after demolition.

The state-sponsored transformation of Liberdade into a ‘Japanese’ neighbourhood in the 1960s–1970s contributed to amnesia about the Remedies. This project introduced an array of urban amenities and modifications to the built environment designed to index Japanese ethnic identity.Footnote 91 Though the project ended with the inauguration of the remade Liberdade in 1978, elements of the project continue through the present. In 2018 the São Paulo state government renamed the local metro station from ‘Liberdade’ to ‘Liberdade – Japão’. The change emphasised the connections between the territory of Liberdade and Japan and, simultaneously, further obscured the history of Liberdade's ‘Black zone’. The demolition and displacement of São Paulo's ‘Black zone’ in the early twentieth century, combined with state-sponsored projects to produce non-Black ‘ethnic enclaves’ in its stead in the decades following, have helped to concretise the myth of São Paulo as a non-Black city in ways that diverge from other racial and spatial contexts, including the Praça Onze and Rio de Janeiro.

While over much of the last half century the history of Liberdade's ‘Black zone’ has been obscured, the local spatial memory politics may be shifting. In 2020 São Paulo state deputy José Américo introduced legislation to rename the Liberdade metro station again, to ‘Japão – Liberdade − África’. It is uncertain whether the proposal will pass. A more assured shift appears in developments relating to São Paulo's first public cemetery for enslaved African descendants, the Cemetery of the Afflicted, located in Liberdade behind the Chapel of the Afflicted. This chapel (see Figure 9) is one of the few structures still standing that attests to Liberdade's significance in São Paulo's ‘Black zone’.

Figure 9. Chapel of the Afflicted, 2017

Source: Photo by author.

The adjacent cemetery had long been interred beneath a complex of asphalted highways and concrete buildings. In 2018, the demolition of a building next to the Chapel of the Afflicted led to an excavation, and archaeologists discovered nine bodies of the formerly enslaved from the Cemetery of the Afflicted.Footnote 92 In January 2020, São Paulo's city government approved a project to create a memorial at the site, ‘aimed at the preservation of the archaeological archive and memory of the Black men and women who lived in the Liberdade neighbourhood, in the centre of São Paulo, during the period of slavery’.Footnote 93 This description makes no mention of the African descendants who lived in Liberdade after the period of formal abolition. However, the cemetery project does reflect an emerging pattern in São Paulo of official recognition of sites significant to African descendants and the memorialisation of histories of racial violence, enslavement, abolition and Black liberation.Footnote 94 While the Remedies has not yet gained a prominent place among these recent memorialisation projects, its history illuminates the deep precedent to these contemporary efforts as well as the official project that led to the disappearance and forgetting of São Paulo's mid-twentieth-century ‘Black zone’.

Acknowledgements

I thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors and staff of JLAS for their productive comments on this article. I also thank Michael Amoruso, Fernando Atique, Meredith Frazier Britt, Maria Helena Britto, Waldir Britto, Luis Ferla, Jeffrey Lesser, Fernando Ripol and Thomas D. Rogers for offering comments on and/or sharing in critical conversations about the Remedies.