Introduction

The rap group Hermanos de Causa puts it best in one of their poetic lyrics: ‘Don't you tell me that there isn't any, because I have seen it; don't tell me that it doesn't exist, because I have lived it … Don't say there is no racism where there is a racist … prejudice is always there’.Footnote 1 They are not alone in denouncing what many black Cubans perceive as a growing social problem: the persistence of racial prejudice and discrimination.

This discussion about race and racism in Cuban society is a fairly recent development. Not too long ago, scholars and activists were denouncing the silence that surrounded this issue. Interestingly, there are elements in the current debate that resemble the first years of the Cuban Revolution, when discussions of race, racism and discrimination came to the centre of national attention. But the fact that the current debate is taking place after five decades of socialist redistributive policies and radical change makes it significantly different. After all, in the minds of many in Cuba these social labels and conducts should have long disappeared by now. The fact that they have not – and on this point there is near consensus – lends itself to alternative, contradictory explanations. Two thousand eight is not 1959.

This paper analyses recent debates on race and racism in Cuba in the context of changing economic and social conditions in the island. These conditions, in turn, must be discussed against the backdrop of the significant economic and social changes that what we now know as ‘the Cuban Revolution’ implemented in the island since the 1960s. Furthermore, current conditions and debates also need to be analysed in relation to a powerful national discourse of racial fraternity that posits that all Cubans are equal members of the nation, the existence of overwhelming evidence to the contrary notwithstanding. My ultimate goal is to assess what impact, if any, current debates on race have had on Cuban authorities and on public perceptions about racial differences in the island.

‘I shall not be silent’: Race and Cultural Production

Rap musicians have played a leading role in forcing a national dialogue on race onto Cuban society. The Hip Hop movement, a loose network of rappers, DJs, break dancers, graffiti artists, producers and cultural promoters, emerged in the island in the early 1990s and acquired national visibility in the middle of decade, after the organisation of the first national rap festival in 1995. Several factors contributed to the consolidation of a national Hip Hop movement. These include the annual festivals of rap, the organisation of several Symposiums on Cuban Hip Hop after 2005, the creation of an official agency for the promotion of rap music (the Agencia Cubana de Rap), as well as the publication of a journal since 2003, which is graphically titled Movimiento: la revista cubana de Hip Hop.Footnote 2

This movement has articulated the frustrations, concerns and aspirations of the black youth, a sector of the population that came to age in the late 1980s and early 1990s, a period of significant changes in Cuban society. State welfare programs crumbled under the effects of the so-called Special Period, as authorities labelled the economic and social crisis that the country experienced following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Racial discrimination and racist discourses gained in prominence, visibility and acceptability. Unlike their elders, who were protagonist and first-hand witnesses of the profound social transformations that Cuban society experienced during the 1960s and 1970s, these youths grew up in a relatively egalitarian society, only to see that equality erode in front of their own eyes. Even though rap was an imported diasporic musical idiom, its emergence and growing popularity in Cuba during the 1990s was very much the expression of local needs and conditions.Footnote 3

Among these conditions were the rapid deterioration of race relations in the island and the resurgence of racism and discrimination in Cuban society. As these youths encountered concrete racial barriers and experienced racism and rejection, they turned to rap to demand redress and social justice. The best example of this discourse continues to be the paradigmatic song Tengo (‘I Have’) by Hermanos de Causa, one of the best-known and most important songs produced by the whole rap movement in the island since its creation. This song rewrote the famous 1964 poem of Nicolás Guillén, Cuba's well-known poet and activist, who as a communist militant had been an active participant in the struggles for racial equality since the 1930s. Guillen's Tengo celebrated the elimination of racial segregation in the early years of the Cuban Revolution and the achievements of the revolutionary government in the area of racial equality. The poem listed all that blacks had obtained under the Revolution, from unrestricted access to previously out-of-reach beaches and hotels, to job opportunities and education. Thanks to the Cuban Revolution, blacks finally had what they should have always had.

From the vantage point of the 1990s, however, what blacks had in Cuban society looked very different to Hermanos de Causa, who used their song to denounce the persistence of racial discrimination and the growing marginalisation of blacks: ‘Tengo una raza oscura y discriminada. Tengo una jornada que me exige y no da nada. Tengo tantas cosas que no puedo ni tocarlas. Tengo instalaciones que no puedo ni pisarlas … Tengo lo que tengo sin tener lo que he tenido’.Footnote 4

A second important theme addressed by many rap musicians concerns widespread racial profiling by the police and the persistence of racist stereotypes that depict blacks as troublemakers prone to crime and violence. ‘Policía, policía tú no eres mi amigo, para la juventud cubana eres la peor pesadilla’, sings Papá Humbertico.Footnote 5 ‘Mi color te trae todos los días … a toda hora, la misma persecución’, concurs Alto Voltaje.Footnote 6 Hermanos de Causa deal with these issues in another paradigmatic song, Lágrimas Negras. As they do in Tengo, they use an icon of Cuban national culture, a love song composed in the 1930s by Miguel Matamoros, to comment on contemporary social problems: ‘negro delincuente, concepto legendario, visto como el adversario en cualquier horario … El agente policiaco con silbato o sin silbato, sofocando a cada rato, los más prietos son el plato preferido, los otros aquí son unos santos … más fácil es culpar a alguno de color oscuro … estoy cansado de que aprietes tu bolso cuando te paso por al lado’.Footnote 7 Molano MC complicates this denunciation further by noting, in his well-known ¿Quién tiró la tiza? that it is working class blacks youths – el negro ese – who get marked as troublemakers. The group Obsesión, in turn, notes that these stereotypes are also gendered. In their La llaman puta they refer to the difficult options faced by women who cannot obtain a job and are forced into jineterismo or prostitution, an activity that, in the eyes of many white Cubans, is a preferred choice for black females.Footnote 8

The raperos and raperas have also used their music to discuss larger questions of race, history and identity. Many have used Afro-Cuban religious symbols to highlight the need to fully acknowledge African contributions to Cubanidad. Some rappers play an active role in this process of recovery and affirmation by using Yoruba terms in their songs, an effort that seeks to arrest and perhaps even reverse the process of cultural destruction associated with slavery and the Middle Passage.Footnote 9 Las Krudas put it eloquently: ‘Mis costumbres las cambiaron, mis dialectos aplastaron, mi lengua la olvidé’.Footnote 10Anónimo Consejo asks a similar question: ‘¿De dónde vine?’.Footnote 11

As part of this conversation on history and identity, some rappers invoke the names of Afro-Cuban heroes in the wars for independence or in the struggles for justice and racial equality during the republic, from Antonio Maceo to Gustavo Urrutia. Several of them refer to the Partido Independiente de Color (PIC) and its leaders, Evaristo Estenoz and Pedro Ivonet, who were killed in a racist backlash following the party's revolt in 1912. References to the PIC are charged with symbolism: the party is the national paradigm for racially-defined mobilisation and its activities were barely known to most Cubans, rappers included, until recently. By inscribing these actors into their narratives of history and Afro-Cuban identity, rappers such as Anónimo Consejo or Papá Humbertico invite young Cubans, particularly black young Cubans, to recover elements of their past that have long been silenced.Footnote 12

Debates about race and nation are also linked to global struggles for racial justice. Many rappers establish these links explicitly, invoking Afro-Cuban national heroes along with fighters for racial justice and equality elsewhere, particularly in the United States and South Africa. In this manner they insert themselves into what several scholars have characterized as diasporic conversations on race, justice, and identity. Anónimo Consejo, for instance, identifies with Nelso Mandela and calls him guapo, a term that in Cuban vernacular refers to tough street guys, but that is also used to designate bravery. The group Primera Base dedicates a song to Malcolm X while claiming to be like him: ‘Igual que tú, igual que tú, nigger, a nigger like you’. Las Krudas call themselves ‘warriors’ and ask their ‘oppressed race’ to raise a fist in unity. The important thing, as Hermanos de Causa puts it, is to give ‘continuity to the Afro struggle’.Footnote 13

Visual artists have also been prominent participants in these debates about race, racism and Cubanidad. Roughly at the same time that raperos and raperas were beginning to raise their voices in the early 1990s from the working-class neighbourhoods of Havana and other cities, a group of young painters began to address issues of race and identity in their works. It is perhaps not altogether surprising that their discourses paralleled those of the musicians, whose concerns, aspirations and frustrations they largely shared, even though these discourses were articulated and disseminated in different social spaces. As one of these visual artists, Roberto Diago, has stated, ‘what I am doing is something similar to a painting in a rap mode’.Footnote 14

These ‘visual raps’ were articulated in three important exhibits organised in Havana between 1997 and 1999. The first of these, Queloides (I Parte), was organised by artist Alexis Esquivel and curator Omar Pascual Castillo at Casa de Africa. Although keloids (wound-induced raised scars) can appear on any skin, many in Cuba believe that the black skin is particularly susceptible to them.Footnote 15 Thus the title evokes the persistence of racial stereotypes, on the one hand, and the traumatic process of dealing with racism and discrimination, on the other hand. The artists who were invited to participate, many of whom do not self-identify as blacks, had incorporated topics concerning race and identity into their works. In addition to Esquivel and Castillo, the exhibit included works by Alvaro Almaguer, Manuel Arenas, Roberto Diago, René Peña, Douglas Pérez, Elio Rodríguez Valdés (el Macho), Gertrudis Rivalta and José Angel Vincench. ‘I, as well as other colleagues had many questions and concerns about racial prejudice in Cuba’, explains Esquivel, ‘The artists focused on the black person as a marginalized individual faced with economic disadvantages, traumas, and self reflection’.Footnote 16

This focus remained at the centre of the following exhibit, which took place a few months later at the Centro Provincial de Artes Plásticas y Diseño in Havana. Curated by young art historian, critic and writer Ariel Ribeaux Diago, the exhibit was titled Ni músicos ni deportistas. The title made clear reference to the widespread stereotype that blacks only excel in popular music and sports, two activities that racist discourses equate with an easy life of limited intellectual substance.Footnote 17 The five artists participating in this exhibit – Manuel Arenas, Alexis Esquivel, René Peña, Douglas Pérez and Elio Rodríguez – had taken part in Queloides (I Parte) and continued their conversation on issues of racial representation, stereotypes, history and marginalisation. Ribeaux saw the exhibit, for which he produced an award-winning essay, as the creation of an ‘autonomous space’ where blacks could recognise themselves and be recognised ‘as social beings with specificities’. This space was also one of memory and remembrance, where artists sought to recover the ‘barely existing history’ of a racial group ‘without memory’.Footnote 18

Ribeaux was also the curator and promoter of the third exhibit, also titled Queloides, which was solicited by the Centro de Desarrollo de las Artes Visuales in Havana to celebrate the tenth anniversary of this institution in 1999.Footnote 19 Some of the participants in the previous exhibits – Arenas, Esquivel, Peña, Douglas, Elio – were back, along with Gertrudis Rivalta, who participated in the first Queloides. They were joined by Pedro Alvarez, Lázaro Saavedra, Juan Carlos Alom, Andrés Montalvan and José A. Toirac – this was, in short, the largest of the exhibits. Ribeaux basically envisioned Queloides II as an expansion of Ni músicos ni deportistas and insisted on the need to have a serious conversation about race.

Like the raperos and raperas, these artists used their work to ask vital questions about the meanings of blackness and its intersections with the history of the Cuban nation. Some of them mocked traditional racist images that are very much part of the Cuban popular imaginary. Painter Elio Rodríguez Valdés, for instance, has used his art to criticise folklorist visions of Afro-Cubans, either as eroticised female fetishes who attract lustful tourists to the island, or as male sexual predators who threaten traditional social and racial boundaries. One of his series, Las perlas de tu boca (1995) evokes the image of the slave market, where teeth were used to assess age and health conditions. These poster-like images frequently present a black male – the artist himself – in a white universe, where he does not belong, as with Gone with the Macho (title in English), or satirise the vision of the black male sexual predator, as in La noche del Macho in which he appears as a vampire ready to conquer/devour a lighter mulatto woman. In the 1999 series Mulatísimas, Rodríguez complicates dominant nationalist discourses that identify the nation with a mulatto woman.Footnote 20 Instead of presenting the mulatto woman as a site of national/racial reconciliation, El Macho uses his tobacco-style marquillas to denounce the persistent use of this iconography for commercial and tourist purposes, as he does in Tropicalísima. He typically inserts some elements of the revolutionary iconography – Che Guevara's legendary beret, for example – in his paintings as well, signalling how these icons easily coexist with traditional discourses of race and gender.Footnote 21

Fig. 1. Elio Rodríguez Valdés, El Macho, Tropicalísima, Silk screen illuminated, 1999. Reproduced by permission of Elio Rodríguez.

The conflictive relationship between race, gender and nation is also represented in René Peña's work. A graduate of English language who turned to photography in the early 1990s, Peña seeks to locate social and racial conflicts on the human body. Like Elio Rodríguez, he has mocked racist stereotypes such as that of the black rapist, a stereotype that is part of the global racist imaginary. Pushing this stereotype to the limits in a well-known 1994 photograph, Peña shows a nude torso in which the penis is replaced by a knife. In Queloides II he presented pieces from his series Man Made Materials (original title in English) in which he offers close ups of the black skin. By bringing the black skin close to spectators, Peña assaults fears of racial contagion – this is the knife again, in a different shape – and reasserts the humanity of the black body, no longer just the object of lust and erotic desire.Footnote 22

Fig. 2. René Peña, Serie Rituales (1994), Gelatin silver print. Reproduced by permission of René Peña.

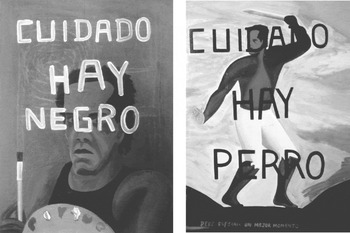

The image of the black predator has also been important to Manuel Arenas, who ridicules the association between race and crime, so important to some of the rap musicians mentioned above. In his Cuidado hay negro and Cuidado hay perro, two pieces included in the first Queloides exhibit, Arenas ridicules fears of blacks while discussing the deep roots of this racial discourse in the history of the Cuban nation. In Cuidado hay perro he inserts a fighting runaway slave (or a member of the 19th-century Liberation Army), to illustrate that current racial fears are nothing new in Cuban history. The historical context is reinforced by a text included in the painting: ‘Deve esperar un mejor momento’ (‘He must wait for a propitious moment’). This inscription makes reference to one persistent thread in Cuban nationalist discourse: that blacks must be patient and mobilise only if the moment is propitious (which never is). Arenas further ridicules these historically-grounded racist fears in Cuidado hay negro, where the dangerous black male is the painter himself.Footnote 23

Figs. 3 and 4. Manuel Arenas, ‘Cuidado hay negro’ and ‘Cuidado hay perro’ (1997), oil and mixed media on canvass. Reproduced by permission of Manuel Arenas.

These artists have also engaged in a serious conversation about history and identity. These themes are especially prominent in the work of Alexis Esquivel, who questions established truths in Cuban historical narratives and challenges some of the silences of Cuban nationalism. His Carlos M. de Céspedes y la libertad de los negros questions the well known narrative that presents Céspedes, initiator of the war of independence in 1868 and ‘father of the motherland’, as a magnanimous patriarch who gives freedom to his slaves. According to Cuban traditional historiography this gesture marks the beginning of the war, which is in turn the beginning of the end of the slave system in the island. It is a discourse in which freedom and abolition are very much the result of white generosity, not of the initiatives of slaves and other popular actors.Footnote 24

Fig. 5. Alexis Esquivel, Carlos M. de Céspedes y la libertad de los negros (1993), oil on cardboard. Reproduced by permission of Alexis Esquivel.

What the traditional discourse on white generosity does not say is that Céspedes also decreed that slavery would not be immediately abolished, that the insurgents would respect the properties of the slave owners, and that liberated slaves would be kept under control. Esquivel's ‘Céspedes’ turns this dominant nationalist narrative around by showing a Padre de la Patria who is a prisoner of his own fears – the fear of black disorder, the fear of a black Cuba, the fear of Haiti.Footnote 25

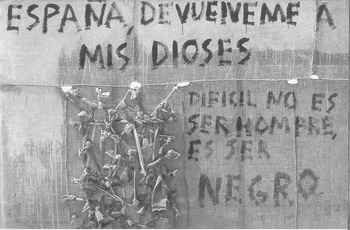

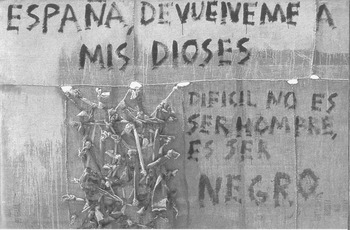

Fig. 6. Juan Roberto Diago, España devuélveme a mis dioses (2002), oil on jute. Reproduced by permission of Juan Roberto Diago.

These artists have also shared with the raperos a concern about Africa. The importance of African elements in Cuban religiosity has long been a theme in Cuban arts and letters, and the topic was central to the work of some painters who preceded this movement, such as Manuel Mendive. Religiosity was also central to the work of the late Belkis Ayón, of the same generation of the Queloides group. But some of these artists have pushed beyond religion to highlight the centrality of Africa to Cuban history and national culture, while exposing ingrained stereotypes about blacks. The work of artist Juan Roberto Diago, another of the young painters who exhibited in Queloides (I Parte), exemplifies these concerns. Diago uses humble materials in his pieces, including sackcloth and dirt brought from Africa. These elements are combined to offer a narrative where historical silences and stereotypes are contested, and where elements of the African past are reclaimed as crucial to contemporary Cubans. He frequently makes his message clearer by inserting graffiti-style texts in his works, reinforcing the association between his work and rap. For example, ‘España devuélveme a mis dioses’ talks about the process of cultural loss associated with the Middle Passage and displays an equally explicit text: ‘Dificil no es ser hombre, es ser negro’.Footnote 26

Other intellectuals, writers and activists, are participating in these public conversations about race, nationhood and identity, some times with a clear polemical tone.Footnote 27 Pedro Pérez Sarduy has asked what black Cubans really ‘have’, using language identical to Hermanos de Causa and invoking Guillén's poem as well.Footnote 28 Award-winning novelist and poet Teresa de Cárdenas has published several children and youth books where she approaches some of the same issues addressed by painters and musicians: racial stereotypes and prejudice; the connections between a past of slavery and present social conditions; the loss of memory, culture and history associated with Africa; and the need to recover these untold stories for children and young readers. ‘I write about those who rarely appear in books: the black woman, the black man, the black girl, the elderly, abused children, raped women …’ Cárdenas identifies Cubanidad with the runaway slaves that fought against slavery and invokes Africa as a central reference: ‘Africa is everything that has to do with my past, all that I ignore’.Footnote 29

The process of reclaiming Africa is also evident in the work of other writers. Poet Nancy Morejón deals with this subject in several of her works, particularly in her Poética de los altares, where she defends the existence of a common, transnational Afroamérica.Footnote 30 Rogelio Martínez Furé, one of the leading researchers of African culture in Cuba, has continued his decades-long work of disseminating African literature in the island.Footnote 31 Other compilations of African legends have been published, along with a multitude of books on Afro-Cuban religions.Footnote 32 These books have found an eager audience, as Santería and other Afro-Cuban religions have experienced a remarkable renaissance since the early 1990s, a process that has contributed significantly to public conversations on race, culture and national identity in the island. As Christine Ayorinde has explained, Santería has become the country's national religion and is practiced by people of different racial and social groups.Footnote 33

Academics and social scientists inside and outside the island have also begun to study the problem of race, both in its historical dimensions and in contemporary society. Historical events such as the 1912 massacre, which has elicited so much interest among young painters and musicians, have been researched in books and in one important documentary by filmmaker Gloria Rolando.Footnote 34 The Centro de Antropología de Cuba has promoted important research on racial themes since the early 1990s and, from UNEAC, the project Color Cubano has sought to create a space for discussions on race and marginality. Moreover, the 1998 Congress of UNEAC openly debated the existence of racial discrimination in jobs and the media.Footnote 35

A few cultural and civic activists are also contributing to public debates about race and racism.Footnote 36 Although their activities are more difficult to trace, the importance of their work should not be underestimated. These activists disseminate information about racist practices, organise public acts to celebrate forgotten historical dates, figures and events, and petition authorities concerning cases of discrimination. Their impact is frequently circumscribed to their communities, but they have also helped to create awareness about the persistence of racial discrimination in Cuban society through their interactions with authorities.

An excellent example of this kind of civic and cultural activist is the Cofradía de la Negritud, a civic organisation founded in 1998 by engineer Norberto Mesa Carbonell. The Cofradía was created to work against some of the most negative effects of the Special Period on race relations, particularly a growing income gap according to race and the lack of good employment opportunities for blacks in the most desirable sectors of the national economy. They have demanded official action on these issues, approaching the National Assembly to request a parliamentary debate on racism and the creation of a state institution charged with the implementation of a national policy against racism. They ask for the elimination of racial references in employment application forms and the creation of mechanisms to prevent discriminatory practices in the allocation of jobs, particularly in ‘dollar stores, tourism, firms and corporations’. They have also requested what in practice amounts to affirmative action policies to facilitate the ‘proportional access of people from poor families to centres of educational excellence’.Footnote 37

Two other areas in which the Cofradía detects widespread discrimination are those of police repression and issues of representation in the media. They share the raperos' and painters' indignation concerning practices of racial profiling by the police, a concern that seems to be fairly widespread among black Cubans. Thus their request in this area: ‘To make sure that police actions do not continue to give the impression that they are based on stereotypes concerning skin colour, or that citizens are treated differentially for this reason’. As for representation, they have petitioned for an ‘effective and proportional presence’ of ‘blacks and mulattoes’ on television, ballet and in movies.

The members of this group are also participating in public discussions about history and identity. Very much like the rap musicians and visual artists, they demand a public and systematic acknowledgement of the contributions that Africans and their descendants have made to the country's ‘progress’ and to the formation of the Cuban nation. They have campaigned to officially designate Mariana Grajales, mother of Afro-Cuban patriot and war hero Antonio Maceo, as Madre de la Patria, just as white patriot and slave owner Carlos Manuel de Céspedes is known to be the Padre de la Patria. They have worked to raise public awareness about the PIC and the racist massacre of 1912. In June 2006 they approached the president of the Union of Journalists (UPEC) to request coverage for the PIC, their actions, and the repression against them. When in early 2007 the newspaper Granma published a list of historical dates that did not include the events of 1912, they wrote to the director of the newspaper demanding official acknowledgement for the 95th anniversary of the PIC's revolt and the ‘racist genocide’ against its members.Footnote 38 Fusing past and present struggles into a single narrative, the Cofradía referred to the need to inscribe these ‘terrible events’ in ‘the historical memory of the nation’, so that they could never be repeated. The actions of the Independientes were not ‘something of the past’, they explained, for their efforts serve as inspiration to those who currently ‘make growing efforts in the fight against racism, discrimination, and racial inequalities that, in plain sight and with the silence of many, have gained preponderance in our country’.

Given the actions and efforts of all these intellectuals, artists and activists, it is increasingly difficult to sustain, as was the case just a few years ago, that race continues to be a taboo in public discourses. The ‘social debate’ about this topic is no longer a ‘deferred battle’, to use Roberto Zurbano's expression.Footnote 39 This battle is being waged in Cuba today. Indeed, one of the unintended and perhaps one of the few welcome effects of the so-called Special Period is that it forced this conversation on the Cuban people. But it did so by giving race a social visibility, currency and importance that it had not enjoyed for decades.

The Special Period and the Erosion of Racial Equality

In his Race in Another America, sociologist Edward Telles explains that a racially-unequal social structure is based on three important factors: extreme social inequality; a ‘discriminatory glass ceiling’ that limits the access of nonwhites to the middle class, and ‘a racist culture’ that explains the social subordination of nonwhites as a natural fact that needs not be analysed.Footnote 40 The Cuban post-revolutionary experience seems to validate the centrality of these factors. Although much more research is needed on the impact of the Cuban Revolution on this and other areas of social life, the available evidence strongly suggests that the Cuban revolutionary experiment was remarkably successful in dismantling the first two factors mentioned by Telles. The government seems to have been much less successful, however, in dismantling Cuba's racist culture.Footnote 41

The significant reduction of inequalities in a number of key areas of social life since the 1960s, from income levels to access to social capital, resulted in a dramatic decline in several indicators of racial inequality. Most revolutionary policies sought to improve the material conditions of the poorest sectors of society – what revolutionary leaders called los humildes – where blacks and mulattoes were vastly over-represented. Initial programs in education, job training and housing all targeted the poor and resulted in concrete and immediate gains for the non-white population. The 1961 literacy campaign created educational opportunities for thousands of poor Cubans who were functionally illiterate. Some of the least privileged members of the working population participated in training programs that resulted in significant mobility, both substantially and symbolically. Low-income students were housed at the mansions of the country's bourgeoisie and given state scholarships. Employment opportunities were created in sectors that had been virtually closed to blacks, such as retail stores and banks. Some of the poorest shanty towns were destroyed, their residents offered access to state subsidised housing.Footnote 42

The process of reducing social inequalities was accelerated by the massive flight of the upper and middle-upper sectors of Cuban society, those who had enjoyed a privileged position in pre-revolutionary society in terms of wealth, education and status.Footnote 43 The new managerial and professional spaces were filled by individuals from lower social ranks, creating significant social mobility in the process. Further redistribution of income took place through the rationing system, the standardisation of salaries in the massive public sector, and the socialisation of key services. By the late 1970s racial inequality had not only diminished significantly in several important areas, but large numbers of non-white Cubans had completed technical or university degrees and entered the ranks of the professions and into managerial positions. The Cubans had not only eliminated Telles's ‘hyperinequality’, but also destroyed the ‘discriminatory glass ceiling’ that had kept blacks at the bottom of society in the past. Large numbers of nonwhites had acquired the education and income associated with middle class status.

As the Special Period would soon show, however, this status was somewhat precarious. Despite significant gains in education and employment, many blacks continued to live in the poorest urban neighbourhoods and remained dangerously close to poverty and to a past of deprivations that refused to simply disappear. More to the point, they continued to inhabit a racist culture that in many subtle and not-so-subtle ways continued to inform social and personal interactions and life opportunities. A multitude of aphorisms, popular sayings, and jokes continued to denigrate blacks as naturally inferior and predisposed to crime and violence. Racist prejudices were also evident in shaping public opinions about inter-racial couples, always one of the most sensitive areas in any racially-stratified society.Footnote 44

This racist culture seems to have been reproduced in the safety of private spaces, where it remained hidden for many years. Debates about race and racism largely disappeared from public spaces since the 1960s, when Cuban authorities proudly proclaimed that the Revolution had eradicated, once and for all, racial discrimination from the island.Footnote 45 In this sense, the Cuban government ended up subscribing to a modified version of the dominant interpretation of the nationalist ideology of racial fraternity, an interpretation that had been championed by all republican governments before.Footnote 46 According to this interpretation, racial divisions were a thing of the past. Most republican administrations endorsed the notion that Cubans had taken definitive and irreversible steps towards racial integration since the wars for independence. A racially-fraternal nation was supposed to be an achievement of those foundational wars. The Cuban revolutionary government's version was not all that different: racial divisions were indeed a thing of the past, but only because ‘the Revolution’ had concluded the work of the mambises.

The survival and reproduction of this racist culture helps to explain why, when the Cuban economy collapsed in the early 1990s, the ensuing crisis produced racially-differentiated effects. The ‘glass ceiling’, which was previously defined in terms of education and occupation, was redefined and ‘dollarised’. The legalisation of the US dollar created massive differences in terms of consumption and material wellbeing between those who had access to hard currency and those who did not.

This redefinition of the glass ceiling had multiple social effects. Social status was no longer commensurate with education, as had been the case in the past. An advanced education was no longer a requisite to attain middle-class status. Many people who received dollars, either through family remittances or jobs in the tourist sector, did not have a university education.Footnote 47 By the 1990s people in the island were saying that the key to a good life was neither education nor participation in revolutionary organisations, but to have ‘fe’, that is familia en el extranjero.Footnote 48

One of the most visible social effects of the dollarisation of the glass ceiling was a significant increase in racial inequality. One the one hand, most blacks in the island lack ‘fe’. Since the early 1990s blacks have received a disproportionately small share of the dollar remittances from abroad. This is largely a function of the racial composition of the Cuban-American community, which is overwhelmingly white. According to a survey conducted in Havana in 2000, 34 per cent of households receive remittances from abroad. But whereas 44 per cent of white households received remittances, only 23 per cent of black households did. A team of researchers from the Centro de Antropología de Cuba found that between 1996 and 2002, whites were 2.5 times more likely to receive remittances than blacks.Footnote 49

In addition to this, there is significant evidence that blacks' access to jobs in the tourist sector and in the joint ventures that involve foreign capital has been exceedingly low. According to research done by the Centro de Antropología de Cuba, blacks barely represent five per cent of the labour force employed in tourism and other sectors where it is possible to earn dollars. The 2000 survey found that when total payments (pesos and dollars) are taken into account in the state sector, the proportion of blacks in the top income tier is only three per cent, compared to 12 per cent among whites. And this is in the state sector. In the small self-employed sector differences are even larger, for the most lucrative activities in this sector – home-based restaurants, renting of rooms to tourists – imply the ownership of resources that most black families do not have.Footnote 50

Many of these jobs are allocated through informal networks in which blacks are clearly disadvantaged. As a black worker in a Havana hotel explained, ‘Part of it is information. Many of the openings are spread through word of mouth. I think there is a perception that the hotels and the tourists prefer whites, therefore whites get asked to apply. I try to spread the word to blacks when there are openings, but many of them do not get hired, and many cannot make it through the interview process. Many are simply discouraged and do not try anymore’. As this testimony shows, the disadvantage of blacks refers to perceptions about their undesirability for these jobs, on the one hand, and to concrete actions to prevent their entry into this sector, on the other hand. After all, those who do apply rarely ‘make it’ through the interviews and get discouraged as a result.Footnote 51

These ‘perceptions’ revolve around aesthetic criteria and beliefs concerning black's decency and efficiency. Concretely, many of the people charged with hiring for these positions believe that to work in the tourist sector, particularly in positions that require direct contact with tourists–and which carry better opportunities for income – it is necessary to have buena presencia, a ‘pleasant appearance’ that only whites can have.Footnote 52 Others simply believe that blacks lack the moral and personal requisites necessary to perform important jobs and base hiring decisions on these perceptions. According to several surveys conducted in the island in the mid-1990s, most whites believe that blacks and whites do not share the same values, decency and intelligence.Footnote 53 As a result, white managers create significant obstacles to black applicants, even if they do not always openly acknowledge their reservations.Footnote 54 And this is no secret: when asked whether blacks and whites have equal opportunity to obtain jobs in tourism, a substantial proportion of white and black respondents offer a negative answer.Footnote 55

Some whites have seen further confirmation of their racist beliefs since the 1990s. As blacks reacted to these changing realities and exclusions, they turned to the informal economy for opportunities. In practice, this has meant performing jobs which are either openly or implicitly illegal, including hustling, selling of stolen goods and prostitution – a group of activities that usually come under the rubric of jineterismo in the island. To many whites this serves as confirmation that blacks are in fact naturally predisposed to corruption and crime. In the eyes of some of these individuals this may be one of the most important lessons of the revolutionary experience: if after several decades of social engineering blacks were unable to achieve full equality, then they must have some constitutional, genetic, deficiencies.Footnote 56 This perception seems to be shared by the police, which constantly targets young black males as suspects of illegal behaviour, stops them in the streets, and asks them to furnish identity papers.Footnote 57

Race, Silence, and Racial Democracy

This is the context in which the artists, writers, musicians and artists mentioned above have been working for the last 15 years. They have reacted to the growing visibility and acceptability of openly racist discourses and remarks, to discriminatory practices in job allocations, and to widespread police profiling. They have also questioned what it means to be Cuban, and how race intersects with Cubanidad. In other words, they have been questioning how, in what is supposed to be a racially-fraternal and egalitarian nation, racist ideas and practices persist.

The efforts of these artists, intellectuals and activists have not been without results. Although few if any concrete institutional steps have been taken to target the growing racial gap, they have been largely successful in raising awareness about this problem and bringing it to the attention of authorities and the Cuban public. In a country where this problem did not officially exist just a few years ago – as late as 1997 Fidel Castro was still saying publicly that ‘the Revolution [had] eliminated racial discrimination’ from the island – this is no small achievement.Footnote 58

To begin with, these intellectuals have managed to place the issue in the national media, not only in specialised journals such as Temas, Catauro: Revista Cubana de Antropología and Criterios, but also in periodicals with a wider circulation such as El Caimán Barbudo, Bohemia, and Juventud Rebelde. The first issue of La Gaceta de Cuba in 2005 was devoted entirely to questions of race, culture, and identity in Cuban contemporary society.Footnote 59 Although not necessarily in response to the Cofradía's request, in 2007 Granma devoted a full page to commemorate the revolt of the Partido Independiente de Color and a national commission has been appointed to commemorate the creation of the PIC.Footnote 60 Perhaps the most notable success of these intellectuals and artists is to have changed public perceptions about Cuba's racial democracy. It is no small feat that in Cuba, the land of José Martí and of racial fraternity, most people now agree that racism constitutes a problem.Footnote 61

There is also evidence that authorities are listening, at least to some degree. Since the late 1990s Cuban leaders have acknowledged that racial differences continue to characterise Cuban society. Reversing previous assertions about the subject, Fidel Castro has repeatedly stated that racial differences remain and that this problem requires additional attention.Footnote 62 Although Cuban leaders tend to explain racial differences and discrimination as ‘remnants of the past’, the official acknowledgement that Cuba is not, after all, a country free of racial differences lends legitimacy to the work of the intellectuals and activists interested on this problem and to the debates that they have promoted.Footnote 63 Furthermore, government authorities are now paying closer attention to issues of political representation and have publicly demanded that blacks, women, and youths be promoted to positions of leadership within government structures and the Communist Party. It does not seem to be a coincidence that among the representatives elected to the National Assembly in January 2008, blacks and mulattoes represent 35 per cent, a proportion which is identical to that reported in the 2002 census. It is certainly not a coincidence that the National Electoral Commission released information concerning the racial distribution of those elected.Footnote 64

Several factors have limited the impact of the debate on racial issues proposed by cultural actors and activists, however. Many artists and writers complain that it is very difficult to publicize their work through the national media and denounce official efforts to minimize the impact of their work. Cultural authorities have created a special agency for rap music, for instance, but many raperos and raperas assert that the promotion of their music at a national scale is limited and that Hip Hop's ‘presence in the mass media’ continues to be ‘controversial’, as promoter Ariel Fernandez asserts. Las Krudas put it eloquently: ‘A mí me quieren callar, a mí, ¿por qué’. The situation is not altogether different in other areas of cultural life. Writer Teresa de Cárdenas notes that she is ‘an author for whom it is very difficult to publish, at least in Cuba’. Black actress Elvira Cervera proposed a project, ‘All in Sepia’ to increase the dismal representation of blacks in theatre, but met with official silence. Visual artists have exhibited their important work in state galleries, but they report lack of support and occasional hostility towards their work. It is worth noting that the important exhibit Queloides II received limited coverage in the national press.Footnote 65

The impact of this dialogue on race and discrimination is further limited by the fact that these cultural actors do not speak with a coordinated voice. In fact, it is not possible to speak of an Afro-Cuban cultural movement ‘in the programmatic sense’, as painter Elio Rodríguez Valdés asserts.Footnote 66 At the same time, there is a growing awareness among at least some of these musicians, artists, writers, academics, and activists, that they share very similar concerns about racism and its social effects. Some of these concerns are being articulated in spaces outside direct government control, such as the symposia on Cuban Hip Hop organized since 2005.Footnote 67

It may be possible to interpret the Cuban government's limited tolerance for this new Afro-Cuban cultural movement as an attempt of the ruling elites to defuse racial conflicts through the selective incorporation or nationalization of oppositional cultural forms.Footnote 68 Yet the efforts of these cultural actors cannot be reduced to a narrative of elite manipulation. In a sense, the Cuban government has become a victim of some of its own successes. The revolution's radical programme of redistribution of resources and the socialization of key social services resulted in the creation of an unusually large black intelligentsia – the very artists, writers, musicians, activists and intellectuals who are now demanding concrete government actions to turn the official rhetoric of equality into a reality. Furthermore, the government's rhetoric of equality, invoked during the 1960s and 1970s to silence public debates on race, is now used by these young intellectuals to denounce the resurgence of racism and to oppose discriminatory practices in Cuban society. Given its own much touted commitment to equality, the government has little choice but to allow the circulation of these critical discourses and, to a degree, to respond to them. The critics of the ideologies of racial fraternity frequently forget an important lesson: these ideologies place limits not only on subordinate sectors; they also place limits on the political options of the elites – they define what is politically possible in fairly concrete ways. One of the things that seem impossible now is to render these artists and intellectuals effectively silent. As Hermanos de Causa announce in one of their beautiful songs, ‘yo no callaré’.