Independence, a long process completed only in 1825, is seen as the most important event in nineteenth-century Latin American economic history.Footnote 1 Two different approaches to the post-independence era in Latin America can be distinguished. One uses the United States as a yardstick and results in pessimistic assessments of Latin America's post-colonial performance.Footnote 2 Another, associated with the recent growth and development literature that looks into the historical roots of present backwardness in different world regions, depicts – in its most recent form – the half century that followed independence as ‘lost decades’.Footnote 3 The purpose of this paper is to challenge these views by assessing the performance of Latin America during the period between the achievement of colonial emancipation (around 1820) and the beginning of the first wave of globalisation (around 1870). While not rejecting the comparison with the United States, the argument here suggests that contrasting Latin America's economic performance with those world regions that shared its main features, namely, former European colonies with similar geographical conditions and factor endowments and comparable levels of per capita income at independence, can provide new insights into the causes of Latin America's current retardation.Footnote 4

A caveat is needed regarding the inclusion of Brazil and Cuba. Although the paper focuses on economic performance after independence, Brazil (a country that remained united and reached full independence gradually), and Cuba (which remained under colonial rule until 1898 and was largely stable for most of the period under consideration except at its very end when the island suffered the Ten Years' War between 1868 and 1878), are also considered here because they provide a counterpoint of stability and gradual institutional transition while opening up to international commodity and factor markets.

This paper begins by considering the effects of independence across Latin America, in particular the fiscal and commercial consequences of the end of colonial rule and the opening of the region to the international economy, and then analyses the aggregate economic performance of the new republics in comparative perspective. The main findings can be summarised as follows. First, the release of the fiscal burden of the imperial system was partly offset in the new countries by the higher costs of governing themselves. Second, integration into the world economy brought net gains to Latin American economies over the long run, although they were unevenly distributed. Third, in post-independence Latin America, per capita GDP experienced moderate growth on average but exhibited a large variance across regions. When compared to the United States, Latin America's position deteriorated, but it remained unaltered with respect to the European periphery and clearly improved with respect to Africa and Asia. Hence, ‘lost decades’ seems an unwarranted depiction of this period.

Assessing the Demise of Colonial Rule

Independence brought with it the release of the colonial fiscal and trade burden. The colonial fiscal burden consisted of the taxes levied on the indigenous population, and the surpluses of the colonial administration (the ‘remittances from the Indies’) were sent to Spain. Strictly speaking, the fiscal burden should be defined as uncompensated remittances, and should thus represent net revenues for the metropolis. Since part of the remittances was in fact allocated to the defence or security of the empire, they provide an upper bound of the actual fiscal burden. In the 1790s this expenditure represented more than half of all the sums sent to Spain from the American colonies.Footnote 5 By 1800, residents in Bourbon Mexico paid more taxes than Spaniards in the metropolis and were making, therefore, a significant contribution to the imperial administration.Footnote 6 Removing colonial rule eliminated the fiscal burden and, ceteris paribus, added to Latin American GDP.Footnote 7

However, if the net gain for Latin America is to be estimated, an increase in the costs of administering many political units, rather than a single one, has to be taken on board. The monetary and fiscal disintegration brought about by independence produced the demise of the largest monetary union and fiscal structure in existence, contributed to political fragmentation, and was reflected in weak national administrations and increasing transaction costs.Footnote 8 Separation from Spain had negative effects in terms of economic efficiency: commercial links among regions, however weak in colonial times, were no longer guaranteed. Increasing market integration within the Spanish empire during the late seventeenth and especially the eighteenth century, as shown by the convergence of prices in the Viceroyalty of Peru, came to a halt with independence.Footnote 9 Intra-colonial fiscal transfers were, according to Regina Grafe and Alejandra Irigoin, the successful basis of the colonial system.Footnote 10 In their view, colonial self-sufficiency rather than transfers to the metropolis was the main fiscal goal of the empire as a result of negotiation between creole elites and the imperial authorities. However, as William Summerhill points out, fiscal transfers would only increase aggregate output if they went from low to high productivity areas.Footnote 11 After independence unequal access to fiscal resources in the absence of intra-colonial redistribution of tax revenues provoked a struggle for the control of fiscal resources and led to political strife.Footnote 12 Costs in defence and law enforcement had to be duplicated, and coordination in the provision of public goods became more difficult. There is, however, the theoretical possibility that the efficient size of government was not that of one government for all of Spanish America, but one of smaller scale. If this were the case, the benefits from independence for Latin America would be higher than those suggested here.

Each new republic faced the challenge of creating a new fiscal and monetary system and a domestic financial market. Customs duties became the backbone of the new fiscal systems, as in the United States after independence.Footnote 13 Unlike the United States, however, most Latin American governments suffered chronic deficits during the first half of the nineteenth century as tax revenues stagnated and military expenses increased. In fact, fiscal policies were subordinated to military and political caudillos, at the expense and dilution of tax administration. A vicious cycle emerged in which fiscal weakness led to weak government which led in turn to frequent challenges to the elite in power. As a result, civil strife proliferated.Footnote 14 According to Douglass North, William Summerhill and Barry Weingast, the break with the metropolis destroyed many of the institutions that provided credible commitments to rights and property within the Spanish empire.Footnote 15 The lack of stabilising institutions made it impossible to achieve efficient economic organisation. Hence, a scramble to preserve colonial protection and privileges or to secure new powers occurred.

Alas, hard empirical evidence on the impact of the release of the colonial fiscal and trade burden on each new republic remains scant and only a few national testimonies can be provided. In Mexico the extraordinary rise in internal military expenditures, a growing tendency to rely on forced loans, and the increasing fiscal autonomy of local treasuries resulted in the destruction of the colonial treasury system.Footnote 16 As a result the supply of credit was reduced and, it has been argued, local credit markets disintegrated.Footnote 17 Meanwhile, the internal public debt grew by nearly 40 per cent between 1823 and 1848, an outcome of growing fiscal deficits. Such a situation represented a break with the past, as there were no deficits under colonial rule. In fact, there were transfers of surplus from one colony to another (situados).Footnote 18 Independence in Mexico led to the abolition of two major sources of income of the colonial administration: the Indian tribute (levied on all heads of households in Indian towns) and mining taxes (a 10 per cent duty had been levied on all silver produced). This reduced the potential income of the state by almost 30 per cent.Footnote 19 Instability paralleled the growth of the public debt, leading arguably to the crowding out of private investment.Footnote 20 A negative association has been posited between political instability and economic growth in the half-century after Mexican independence.Footnote 21

In the other main centre of the Spanish empire, Peru, independence took place under different circumstances: foreign republican armies defeated royalist elites. The destruction of fixed capital during the war, fiscal mismanagement and default, and political turmoil had a negative impact on the economy.Footnote 22 The republican state, which suffered from a chronic fiscal deficit, increased taxation, faced a difficult recovery. As in Mexico, the abandonment and flooding of mines and the high price of the mercury, used to refine silver, appears to lie behind the collapse of mining.Footnote 23 Independence, in the end, did not deliver the conditions for sustained economic growth.

In another area of large indigenous population, Central America, the economic effects of political instability and war included the destruction of capital, obstacles to trade and transport, and insecurity for investors, while the government extracted forced loans from merchants.Footnote 24 The prolonged transition to private property surely introduced uncertainty that delayed investment in land improvement and increased transaction costs.Footnote 25

The case of Brazil is rather exceptional as it remained united and centralised and experienced a relatively peaceful transition to independence (but for the Pernambuco rebellion in 1817), during which time institutional continuity was apparent. It is presented here as a useful counterpoint to most other Spanish American countries. Brazil, like Chile, behaved differently as the country managed to create institutions that protected groups from aggression and expropriation, although it failed to achieve political competition and cooperation among sub-national administrative entities.Footnote 26 Colombia, in turn, was successful in improving the colonial tax regime and, by 1850, had a much fairer, efficient and neutral fiscal system. The head tax on Indians, taxes on public employees and alcabalas (a tax on all sales of domestic products) were eliminated, and the state drew its revenues mainly from customs taxes on imports.Footnote 27

Regarding the former Viceroyalty of the River Plate, here political stability and economic growth were achieved in Buenos Aires and Uruguay, while stagnation and political instability prevailed in the interior.Footnote 28 The economy of Buenos Aires benefited from the disappearance of a fiscal system that had created disincentives for productive activities. Stable political institutions that allowed contract enforcement were introduced.Footnote 29 The Rosas dictatorship restricted property and free trade, but lack of political freedoms did not imply the total suppression of economic freedoms. In the interior provinces, however, the principles of economic freedom were not easily accepted. Only with the 1853 constitution was national organisation on the basis of economic freedom widely accepted, while its enforcement took another thirty years.

The provinces of the Viceroyalty of the River Plate failed to devise an incentive structure to keep them voluntarily united under a single government and to take advantage of economies of scale in the provision of defence and justice, reducing transaction costs and encouraging economic development, as the separation of Uruguay and Paraguay revealed. Military threats and trade blockades had long lasting economic and political consequences in Paraguay, leading to a crisis in public finances and economic contraction, and to the political demise of proponents of more representative governments and freer trade. They also gave rise to political absolutism and the redistribution of property towards the state.Footnote 30 Economic activity in the three decades following independence fell below the levels reached in the late colonial period.

To summarise this section, reallocating resources from a large closed economy, the colonial empire, to small and often open economies such as the new republics implied a non-negligible cost. The colonial empire provided security and justice at a cost that was not too high. With independence, new providers of protection emerged, but with a lower capacity than the metropolis. Transaction costs increased with independence, as political and economic institutions went through a period of turmoil and redefinition, while continued violence between and within countries also contributed to less well-defined property rights. These costs were higher for the new republics because of their fragmentation and the loss of economies of scale. Moreover, a single fiscal system within a monetary and customs union, such as the Spanish empire, probably represented significant savings compared to the multiple national fiscal and monetary units created by colonial independence. On the whole, it can be conjectured that the benefits that countries in Spanish America derived from the removal of the fiscal burden were partly offset by the increasing costs of providing their own governments.

Some caveats are needed, however. The Spanish empire's involvement in wars during the final part of the colonial period consumed enormous funds, and so its disappearance, as a result of independence, implied a benefit. Moreover, the loss of economies of scale as independence brought about political fragmentation should be balanced against the increasing costs of keeping colonial populations under control. These objections work in favour of the idea that independence did bring some benefits to Latin America and provide a lower bound to the gains from the release of the colonial burden that have been discussed in this section. Conversely, since part of the remittances to the metropolis was allocated to the defence of the empire, the identification of the fiscal burden with total remittances to Spain results in an upper bound.

Opening Up to the International Economy

The release of the trade burden imposed by the colonial system allowed the new Latin American countries to have access to expanding world commodity and factor markets.Footnote 31 Independence allowed the Latin American republics to trade directly with Europe and North America, and represented a reduction in transportation and commercialisation costs that, ceteris paribus, would increase the volume of trade. However, warfare and political instability in the decades following independence made the adjustment to the new international trade regime difficult. Similarly, tariff protection resulting from the new republics' budget constraints probably diminished the positive impact arising from the removal of Iberian commercial monopolies.Footnote 32

While the Latin American economies opened up to international trade, this does not necessarily imply their acceptance of free trade, in the sense of a lack of tariffs, since rising customs revenues represented a relatively inexpensive way to increase government revenue due to the low costs of monitoring. On the other hand, claims of increasing protectionism are not warranted when an increase in the ratio of customs revenues to imports (or total trade) – the nominal level of tariff protection – is accompanied by the growth of real imports per head.Footnote 33 ‘Opening up’ here means the removal of prohibitive tariffs and the increasing access of Latin American economies to international commodity and factor markets. De facto opening up would be, then, confirmed by growing ratios of exports to GDP and by the increase of real exports (that is, the value of exports adjusted for price changes) and foreign investment per Latin American inhabitant.

Trade theories suggest a series of testable hypotheses with regard to the consequences of opening up to the world economy for economic growth in Latin American countries. As a result of getting rid of the trade burden a new ‘frontier’ opened up in which land expanded at a rising cost in terms of other resources.Footnote 34 An expansion of trade would then be expected, as would an increase in output due to better resource allocation. Terms of trade, that is, the relative price of exports in terms of imports, might decline, according to the Prebisch School, as Latin America exported primary goods and imported manufactured produce, although, in the light of classical economists, the opposite would occur.Footnote 35 At the same time, changes in income distribution should take place, with a tendency for within-country inequality to rise as the reward to land, the abundant and less evenly distributed factor, improves relative to labour.Footnote 36 Finally, a worsening of the Latin American position in the world economy can be predicted.Footnote 37

Let us begin by examining the evolution of the net barter terms of trade (NBTT), that is, the ratio of export to import prices, which provide a measure of the purchasing power per unit of exports. If the NBTT had turned in favour of Latin America, opening up to the international economy as a consequence of colonial emancipation, it would have been beneficial rather than harmful. Estimates for major Latin American countries are presented in Table 1. In Mexico the NBTT experienced a moderate improvement between 1828 and 1881 (a growth of 1.4 per cent per year), and probably added 3 per cent to GDP by 1860.Footnote 38 Venezuela's terms of trade followed the Mexican pattern of stability over the period between 1830 and 1850, but then deteriorated in the early 1850s and recovered in the 1870s.Footnote 39 In Chile, after a sharp rise and decline at the time of independence, stability was the rule.Footnote 40 Brazilian purchasing power per unit of exports increased by three-quarters between 1826–30 and 1876–80.Footnote 41 Colombian NBTT improved as much as Brazil between the late 1830s and 1880.Footnote 42 Linda and Richard Salvucci were able (on the basis of Paul Gootenberg's data) to estimate that the net barter terms of trade of Peru increased by 47 per cent between the 1830s and the early 1850s.Footnote 43 Argentina's terms of trade showed an improvement that peaked in the late 1850s.Footnote 44 The evolution of the NBTT in Cuba presents the exception to the rule, as the island's NBTT deteriorated sharply between the early 1840s and 1860s.Footnote 45 Thus, when Latin America started opening up, cautiously and unevenly, its resource abundance did not bring about a deterioration of the terms of trade that would have hindered Latin American growth. Newland's argument for Argentina – that the domestic terms of trade (that is, those perceived by the Latin American population) ought to have improved more than the international terms of trade as independence allowed merchants to trade directly in world markets, colonial tariffs were repealed and the new tariffs were often lower – could possibly be extended to other Latin American countries.Footnote 46

Table 1 Net Barter Terms of Trade in Latin American Countries, 1810–1880

[Average 1836–40=100]

Sources: Cuba: Salvucci and Salvucci, ‘Cuba’, pp. 204–7; Mexico: Salvucci, ‘Mexican Terms of Trade’; Venezuela: Baptista, Bases cuantitativas, pp. 86–90; Colombia: Ocampo, Colombia, p. 93; Brazil: Leff, Underdevelopment, vol. I, p. 82; Argentina: Newland, ‘Exports’, pp. 412–3; Chile: Braun et al., ‘Economía chilena’.

Location mattered in the nineteenth century as the tyranny of distance was a determining factor of trade – in particular, prior to the construction of railways – despite the sharp reduction in ocean freight and insurance rates. Freight rates from Antwerp to Rio de Janeiro in 1850 were only 40 per cent of those prevailing in 1820, but freight rates from Antwerp to New York fell even more, to one-fourth. Meanwhile, insurance rates were cut to one-half and to one-third respectively for voyages from Rio and Buenos Aires to Antwerp.Footnote 47 Transport costs from Antwerp to Buenos Aires and Rio remained relatively stable between 1850 and 1870 but those to Valparaiso, on the Pacific Rim, fell by 40 per cent as a consequence of the convergence of transport costs to the Pacific with those to the Atlantic coast of Latin America's Southern Cone.Footnote 48

Geographical constraints imply that there would be different outcomes from exposure to international trade across regions. Densely populated coastal regions with a temperate climate would be at an advantage compared to landlocked hinterlands in tropical areas, as migration and infrastructure development become more difficult and incentives existed for coastal economies to impose costs on them.Footnote 49 Landlocked economies such as Bolivia and Paraguay, the interior regions of Mexico, Colombia, Brazil and Argentina, and Andean countries such as Ecuador and Peru were clearly at a disadvantage relative to coastal regions. In addition, countries on the Pacific Rim had a transport cost disadvantage over those on the Atlantic coast. Table 2 provides some insights into overall transport costs that emphasise the importance of internal costs of transportation.

Table 2. Transport Costs in Latin America c. 1842

[Pounds sterling per tonne]

Sources: Celia W. Brading, ‘Un análisis comparativo del costo de la vida en diversas capitales de Hispanoamérica (1842)’, Boletín Histórico de la Fundación John Boulton, vol. 20 (1969), pp. 229–66.

Wide regional discrepancies in the degree of integration into the international economy would be expected. In post-independence Mexico the liberalisation of factor markets was a gradual process which ended laws restricting immigration and capital inflows and brought an increase in openness.Footnote 50 Meanwhile in Peru, mercantilist policies remained in place. After an episode of trade expansion up to the mid-1820s, fixed prices, taxation and protectionism remained an obstacle to economic activity for decades. It was only three decades later that the stimulus of the international demand (the guano boom) opened up the country.Footnote 51

Qualitative evidence on Central America suggests stagnation, but the current value of imports from Britain almost doubled (while UK export prices were practically halving) between two peaks (1826 and 1839) though they declined afterwards.Footnote 52 There were limited incentives to trade within Central America as physical barriers implied high transport costs. Independence brought a rupture in colonial commercial networks and procedures. Links between regions of the Federation weakened as export orientation increased. Together with political instability, these factors led to the creation of five new countries in 1839. An exogenous shock also occurred as a consequence of the US assimilation of California: new maritime routes through the isthmus of Panama, together with the completion of the Panama railway in 1855, led to a sharp decline in transport costs, increasing trade and financial flows.Footnote 53

In Brazil, by contrast to Spanish America, independence did not involve a shift in the direction of trade.Footnote 54 The Buenos Aires economy profited from the disappearance of colonial regulation that forced it to trade through the metropolis. Rather than re-exporting silver from Alto Perú, Buenos Aires became an economy exporting livestock products. The main consequence of independence there was the addition of new lands to the area under cultivation and the opening of the region to foreign trade.Footnote 55

The hypothesis that the opening up of Latin American countries to the international economy had a substantial but uneven impact can be empirically tested with evidence on the purchasing power of exports (current values of exports deflated by the price of imports), also known as the income terms of trade, normalised by the size of each country's population in order to capture its relative importance (Table 3).Footnote 56 Location conditioned the importance of trade, with the Southern Cone and the Caribbean ahead of the rest in terms of both levels and growth rates. Significant increases in the relative size of trade are also noticeable for Brazil, Colombia and Peru. The figures at a regional level, which are highly conjectural, suggest that per capita exports increased in Latin America by 50 per cent over these 40 years. For the group of eight countries for which more reliable information is available (LA8 in Table 3), the purchasing power of exports per inhabitant trebled over the period from 1830 to 1870, which implies an average annual rate of growth of 2.8 per cent. Nonetheless, the dispersion in countries' behaviour is, perhaps, the most remarkable feature of Table 3, with Cuba's per capita exports being almost three times the Latin American average in 1830, while Peru only represented one-tenth of it.Footnote 57

Table 3. Purchasing Power of Exports per Capita

[1880 Pounds Sterling]

Note: Current values deflated with the British export price index. LA8 includes Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Mexico, Peru and Venezuela.

Sources: For 1830 exports are from Paul Bairoch and Bouda Etemad, Structure par produits des exportations du Tiers-Monde 1830–1937 (Geneva, 1985), p. 72, and population, from sources in Table 6; for 1850 and 1870, exports come from Bulmer-Thomas, Economic History, pp. 21, 412–3, converted into pounds sterling with Lawrence H. Officer, ‘Exchange rate between the United States dollar and the British pound, 1791–2000’., Economic History Services, EH.Net, 2001, <http://www.eh.net/hmit/exchangerates/pound.php>. The British export price index comes from Mitchell, British Historical Statistics, p. 526.

Evidence from more reliable national sources on the purchasing power of exports (in terms of imports) confirms these findings. Income terms of trade improved in Cuba at an annual rate of 2.7 per cent between 1826/30 and 1870/74, while in Mexico its cumulative rate of variation was 3.5 per cent between 1828/30 and 1872/74.Footnote 58 In Colombia they grew at 4 per cent annually between 1834/39 and 1870/75, while in Venezuela the annual rate was 3.3 per cent between 1831/5 and 1871/75.Footnote 59 In Brazil income terms of trade increased at an annual rate of 3.5 per cent over 1822/31–1862/71.Footnote 60 Finally, in the Southern Cone, Argentina's purchasing power of exports grew at a yearly rate of 5.5 per cent between 1821/25 and 1866/70, while Chile's did so at 6.2 per cent annually over the period between 1821/25 and 1871/75.Footnote 61 An alternative view, that of the purchasing power of Latin American exports to Britain, offers similar results with an annual rate of growth of 5.1 per cent between 1824/26 and 1874/76.Footnote 62

Table 4 shows an alternative measure of the size of the trade sector, the exports/GDP ratio, for a smaller group of countries. Following Victor Bulmer-Thomas's approach, I have computed the ratio of per capita exports to GDP per head at current prices.Footnote 63 This method produces trade ratios in which GDP is adjusted for differences in the price level across countries in a given benchmark year, so-called ‘real’ GDP. This means that, in the case of developing countries such those of Latin America, ‘real’ GDP is larger than ‘nominal’ GDP (that is, the figure obtained by converting the value of GDP in domestic currency into dollars at the trading exchange rate). This is because non-tradeables have lower aggregate price levels in developing countries than in advanced nations. Thus, the resulting trade ratios derived with ‘real’ GDP (Table 4, Panel A) are usually lower than those computed with ‘nominal’ GDP.Footnote 64 If we wish to obtain figures comparable to those currently used in the literature, that is, calculated with ‘nominal’ GDP, the level of ‘real’ GDP ought to be adjusted to the price level of each particular country at the benchmark year (Table 4, Panel B).

Table 4. Exports/GDP Ratios in Latin America, 1830–1870 (%)

Panel A. Exports/‘real’ GDP

Sources: Per capita exports from the sources cited in Table 3; per capita GDP (expressed in 1990 Geary-Khamis dollars) is from Table 6, converted into current prices with the US implicit GDP deflator from Louis Johnston and Samuel H. Williamson, ‘The Annual Real and Nominal GDP for the United States, 1789 – Present.’ Economic History Services, April 2002, <http://www.eh.net/hmit/gdp>. ‘Nominal’ GDP per head is calculated from ‘real’ GDP multiplied by the price level (PL), in other words the ratio of the purchasing power parity exchange rate to the trading exchange rate, from United Nations, World Comparisons of Purchasing Power and Real Product for 1980 (New York, 1987). For Cuba, the population-weighted average PL has been used, as for LA8.

On average, the relative weight of foreign trade increased by two-thirds between 1830 and 1870. As would be expected, the relative weight of trade is inversely proportional to the country's size. Thus, Cuba and Uruguay appear as very open countries, while the opposite is true of Mexico. However this is not the case of Brazil. Meanwhile, the River Plate was the region that increased its exposure to the international economy most between 1830 and 1850.

The inflow of British capital into Latin America confirms the uneven but significant integration of Latin American countries into the international capital market (Table 5).Footnote 65 The growth of real foreign investment per inhabitant provides another measure of openness for the region. Over the half-century after independence, the purchasing power of British investment per inhabitant increased six-fold, at an average annual rate of growth of 3.7 per cent. The purchasing power of British investment per capita in 1865 was two and a half times the level in 1825 but it really took off after 1865, a phenomenon linked to government loans and, to a lesser extent, associated with the shift of foreign investment toward railway construction and public utilities.Footnote 66 The dispersion across countries (which declined between 1825 and 1865 but increased thereafter) stands out; by 1875 British capital was concentrated in the River Plate, Peru and Central America.

Table 5. Purchasing Power of British Investment per capita [1880 Pounds Sterling]

Note: Current values deflated with the British export price index.

Sources: Investment: Stone, ‘British Direct and Portfolio Investment’, pp. 690–722; British export price index: Mitchell, British Historical Statistics, p. 526.

The opening up of Latin America to the international economy has been associated with a widening of income differences within national boundaries and across countries. Little evidence is available on the former for the pre-1870 period, although Argentina represents an exception. Carlos Newland and Javier Ortiz have shown that the expansion in the pastoral sector resulting from improved terms of trade increased the rewards to capital and land, the most intensively used factors, while the farming sector contracted and the returns of its intensive factor, labour, declined, as confirmed by the drop in nominal wages.Footnote 67 A redistribution of income in favour of owners of capital and land (the estancieros) at the expense of workers took place, an empirical confirmation of the Stolper-Samuelson theoretical predictions.Footnote 68

To summarise, release from the colonial trade burden had net gains for the economies of Latin America, as the evolution of the quantities and prices of exported goods suggests. Although trade did not have the strength to pull the economy along as an episode of export-led growth, it can be argued that, when it was not hindered by geographic and institutional barriers, it facilitated growth.Footnote 69 Trade in nineteenth-century Latin America seems to have been, in most national cases, a handmaiden of growth.Footnote 70 Hence, recent claims by Robert Bates, John Coatsworth and Jeffrey Williamson that ‘Latin America failed to exploit the world trade boom between 1820 and 1870 [because of its] aggressive anti-trade policies’, and that, in the early nineteenth century, ‘the growth rates of exports per capita were below 1 per cent per annum’, are at odds with the empirical evidence presented here. This is also the case with their argument that foreign investment was just an ‘ephemeral investment cycle in the early to mid 1820s’.Footnote 71

Weighing up Aggregate Performance in the Post-Independence Era

Evidence on aggregate economic performance across countries shows a wide variance. This paper provides estimates and conjectures for eight countries, based on national authors.Footnote 72 In the core of the colonial empire, Mexico and Peru, independence did not deliver the conditions for sustained economic growth. Wartime destruction of fixed capital, the flight of financial capital, mining depression, fiscal mismanagement and political turmoil all contributed negatively to growth. Among the explanatory hypotheses for sluggish performance in Mexico and Peru are political instability and the decline in silver production, which did not recover until mid-nineteenth century, both as a result of these countries' economic policies and changes in the international market for mercury.Footnote 73

Quantitative guesses are available for Mexico's economic performance. According to Coatsworth, output per head fell at a yearly rate of nearly −0.6 per cent between 1800 and 1860.Footnote 74 Salvucci, in turn, pointed out that prolonged stagnation or even the decline of per capita income are appropriate depictions of Mexican economic performance over the period between 1800 and 1840.Footnote 75 More recently Coatsworth has conceded that, after a decline during the independence wars, a very mild recovery (0.2 per cent per year) occurred between 1820 and 1845.Footnote 76 Ernest Sánchez Santiró has gone further in this revision by sustaining that economic growth and population expansion occurred between 1820 and the mid-1850s, followed by stagnation and even decline until 1870.Footnote 77

Slave economies offer a distinct and different behaviour. They did not undergo a deep political and institutional transformation. Cuba remained loyal to Spain and experienced sustained progress until 1860.Footnote 78 Antonio Santamaría's recent estimates point to an annual growth rate of around 1 per cent for real per capita GDP between 1790 and 1860.Footnote 79 Low rates of growth in a context of free trade, limited structural change, and political stability characterised the case of Brazil.Footnote 80

Meanwhile, in the former Viceroyalty of New Granada, output per head in Venezuela experienced a rise up to the middle of the nineteenth century and stagnated during its central decades.Footnote 81 In Colombia, stability in the level of income per head between 1820 and 1850 was followed by strong growth, giving an average yearly growth rate of 0.5 per cent between 1820 and 1870.Footnote 82

Economies in the Southern Cone show, in turn, sustained economic progress after independence. Chilean GDP per head grew at 1.5 per cent a year between 1810 and 1870, though most of the improvement took place after 1830.Footnote 83 Available economic indicators suggest fast growth in the Buenos Aires region, which translated into an improvement in Argentina's per capita income. Increases in population and the labour force, urbanisation, and a significant rise of total factor productivity in livestock production are among the distinctive features of the River Plate region after independence.Footnote 84 The per capita agricultural output of the Argentine littoral grew at 2 per cent per year between 1825 and 1865.Footnote 85 If we assume that this sector was representative of the littoral's economy as a whole, while in Argentina's interior provinces per capita income stagnated, a population-weighted rate of growth of 0.8 per cent per year would result for per capita GDP.Footnote 86 It does not seem far-fetched to assume that Uruguay's behaviour was rather similar to that on the Argentine side of the River Plate.Footnote 87

The fragmented evidence and conjectures for each country can be used to derive comparative levels of per capita income for Latin America during the 1820–1870 period. The International Comparisons Project (ICP) has produced levels of per capita GDP, adjusted for its purchasing power parity (PPP), that is, for differences in national price levels, for a large sample of countries at different benchmark years that are expressed in so called ‘international’ dollars. ICP benchmark levels for 1990 have been projected with national indices of per capita income at constant prices by Angus Maddison to produce historical series of real GDP per head for a large number of countries.Footnote 88 I followed a similar procedure for Latin American countries and projected backwards per capita GDP levels for 1990 (in Geary-Khamis dollars)Footnote 89 with volume indices of product per head obtained from the available national estimates and conjectures (Table 6). For the rest of the world I used Angus Maddison's figures. Moreover, by weighting each country's per capita GDP level by its share in Latin American population, an aggregate figure can be derived for the entire region. The implicit yearly growth for Latin America's income per head between 1820 and 1870 is 0.5 per cent, a moderate though respectable rate in its historical context, which provides a more optimistic view of the post-independence performance than the recent suggestion of Bates et al. that per capita GDP grew at 0.07 percent per year, ‘or, adjusting for the dubious quality of the data, about zero’.Footnote 90 A caveat is, nonetheless, necessary: the high variance of national estimates for per capita income (the coefficient of variation for a group of eight countries was 0.42 in 1820 and went up to 0.53 in 1870) renders any average figure for Latin America questionable.

Table 6. Comparative GDP per Head, 1820–1870

(Expressed in 1990 International Geary-Khamis Dollars)

Note: For supra-national entities, population weighted averages are used. Numbers in brackets correspond to the number of countries included.

Sources: Maddison, World Economy, p. 642, except for Latin America. Volume indices of Latin American per capita GDP were spliced with Maddison's per capita GDP levels for 1990, expressed in 1990 Geary-Khamis dollars.

Argentina: Gerardo Della Paolera, Alan M. Taylor and Carlos Bózolli, ‘Historical Statistics’, in Gerardo Della Paolera and Alan M. Taylor (eds.), A New Economic History of Argentina (Cambridge, 2003), pp. 376–85 (plus CD-Rom), GDP, 1884–1990, spliced with Roberto Cortés Conde, La economía argentina en el largo plazo (Buenos Aires, 1997), from 1875 onwards. I assumed the level for 1870 was identical to that of 1875. Newland and Poulson, ‘Purely Animal’, p. 328, estimated that Argentina's littoral agricultural output per head grew at 2 per cent per year between 1825 and 1865. I have assumed that this sector was representative of the littoral economy as a whole, and that there was no per capita growth in Argentina's interior provinces. A population-weighted average suggests an annual rate of growth of per capita GDP of 0.8 per cent. Population data comes from Newland, ‘Economic Development’, pp. 212 and 218.

Brazil: GDP, Richard W. Goldsmith, Brasil 1850–1984: Desenvolvimento financeiro sob um século de inflaçao (Sao Paulo, 1986), 1850–1980. Zero per capita income growth for the early nineteenth century as suggested by Leff, Underdevelopment and Development, vol. I, p. 33, was adopted. A lower initial level and, subsequently, a higher growth rate would result if the assumption of Angus Maddison, Monitoring the World Economy, 1820–1992 (Paris, 1995), p. 143, that per capita income growth in the 1820–50 period grew at the same pace as in 1850–1913 were accepted.

Chile: Díaz, Lüders and Wagner, ‘Economía chilena’, p. 57.

Colombia: Kalmanovitz and López Rivera, ‘Ingreso colombiano, 1820–1905; then, GRECO [Grupo de Estudios de Crecimiento Económico], El crecimiento económico colombiano en el siglo XX (Bogotá, 2002).

Cuba: Santamaría, ‘Cuentas nacionales’.

Mexico: Coatsworth, ‘Decline’, p. 41, for the nineteenth century. Following Coatsworth, ‘Mexico’, p. 502, I accepted a mild rise in per capita GDP over the 1820–1845 period; INEGI, Estadísticas Históricas de México, (México DF, 1995), after 1896.

Uruguay: Luis Bértola y asociados, El PBI de Uruguay 1870–1936 y otras estimaciones (Montevideo, 1998). I assumed that Uruguay evolved at the same rate as Argentina's littoral between 1850 and 1870, and at the same rate as Argentina as a whole over the 1820–50 period.

Venezuela: Baptista, Bases cuantitativas, pp. 28, 58.

The historical literature has employed the United States as the yardstick to measure Latin American achievements over the nineteenth century.Footnote 91 A glance at the evolution of per capita income levels in Table 6 suggests that, compared with the United States, Latin America experienced a sustained decline over the period 1820–1870. A country by country analysis, though, appears more informative: while the position of Mexico and Brazil relative to the United States halved, Argentina, Cuba and Venezuela experienced only moderate decline, and Chile and Uruguay kept their positions roughly unaltered.

However, the fact that by 1820 output per head in the United States was practically double that of Latin American raises the question of whether the United States is an appropriate comparator.Footnote 92 Focusing exclusively on the contrast with the United States inevitably leads to a negative assessment of Latin America's economic and political behaviour after independence.Footnote 93 Furthermore, such a comparison diverts attention from the real issue: the extent to which Latin America underperformed in terms of its own potential. Falling behind the United States does not necessarily imply that development opportunities were missed by the new Latin American republics. Lower human capital to labour ratios (implied by life expectancy and literacy rates) and disparate geographical conditions (average temperature, distance to the sea, and latitude) imply different steady states for Anglo-America and Latin America.Footnote 94 Moreover, the insistence of historians on the different institutional settings in Anglo-America and Latin America (the colonial heritage, the initial inequality of wealth and political power, and the definition of property rights) suggest that it would be unrealistic to expect a similar performance in Latin America to that of the United States in the decades to come.Footnote 95

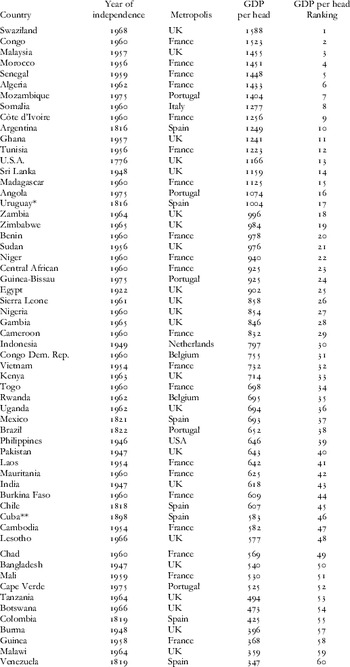

The relevant task, then, would be to identify the feasible counterfactual scenarios that might have led to higher paths of growth. While this is a most difficult empirical challenge at present, it can be observed that, in addition to having been colonies of European powers, a non-negligible group of countries in Asia and Africa shared, at the time of their independence in the 1950s and 1960s, some of the initial conditions of the new Latin American republics in the 1820s: high fertility rates, high land-labour ratios, and high transport costs, low human capital endowment, as well as exogenous factors such as climate and location.Footnote 96 Moreover, the experience of indirect colonial governance, the creation of a modern state from scratch, the fragmentation of former colonies, and the failure to implement modern constitutions inherited from the metropolis are common features of post-independence Latin America and Africa.Footnote 97 On top of that, their levels of GDP per capita at the time of independence are comparable. Former colonies have been ranked in Table 7 according to their GDP per head at the time of emancipation.Footnote 98 In this sample, Latin American countries are concentrated in the fourth and fifth quintiles, except for the River Plate which, like the United States, belongs to the top quintile.Footnote 99 It appears, then, that at the time of independence the new Latin American republics were closer in terms of per capita income to former European colonies in Asia and in Africa than to the United States. Thus, it can be suggested that the contrast with former European colonies in Asia and Africa may provide a useful comparator for post-colonial performance in Latin America. In fact, when Latin America's performance is compared with that of world regions other than the United States during the half-century after independence the picture changes dramatically. Although it fell behind a handful of countries in Western Europe Latin American income per head kept pace with the European periphery and grew faster than Asia and Africa.

Table 7. Per Capita GDP at the Time of Colonial Independence (1990 International Geary-Khamis Dollars)

Note: Per capita GDP are for c. 1820 in the case of Latin American countries.

* Uruguay became an independent country in 1828. Before that it was part of the River Plate Republic.

** Although Cuba became independent in 1898, the level of GDP per head corresponds here to c. 1820.

Sources: Per capita GDP, Latin America, Table 6; Others are from Maddison, World Economy, pp. 552–6, 598–603.

Concluding Remarks

The goal of this article has been to challenge current assessments of Latin American economic performance between emancipation from Spain around 1820 and the beginning of the first wave of globalisation, around 1870. More specifically it questions the value of the United States as the only yardstick to evaluate Latin America, which supports the depiction of the half-century following independence as ‘lost decades’. Such an approach implies that the path followed by the United States provided a feasible counterfactual for Latin America and, thus, implicitly assumes that factor proportions and institutions, as well as policies, were similar across the Americas. The evidence assembled in this paper suggests that falling behind the United States does not necessarily imply that development opportunities were missed by the new Latin American republics. As Stanley and Barbara Stein pointed out:

The existence of a huge, under-populated virgin land of extraordinary resource endowment directly facing Europe and enjoying a climate comparable to that of Europe represented a potentiality for development which existed nowhere else in the New World.Footnote 100

The challenge remains to establish whether Latin America under-performed in terms of its own potential. As a feasible alternative, a systematic comparison with regions that shared its features at the time of their respective independence from European colonial powers (namely, similar geographical conditions and factor endowments, and comparable levels of income per head) is proposed.

The conventional periodisation of Latin American economic history, which sees a clear discontinuity in the early nineteenth century before growth accelerated in its final decades, is also challenged here. Although the short-run effects of independence on economic performance were clearly negative, a more benign picture emerges when we look back at the post-independence era over half a century. The economic discontinuity caused by independence lasted for less time than is usually assumed, especially by those who view these as ‘lost decades’. A more gradual picture can be put forward, with a dramatic drop in income per head during the early revolutionary years, followed by a moderate but sustained growth in the half-century after complete independence, and then an acceleration that placed Latin American countries among the best performers in the world economy during the heyday of the first globalisation.Footnote 101

Independence exacerbated regional disparities. Coatsworth is probably right when he sees ‘the pace of nineteenth-century institutional modernization’ as a ‘good predictor of long term economic performance’.Footnote 102 Institutional modernisation seems to have occurred earlier and faster in the new republics that had not been at the core of the Spanish empire. Moreover, geography mattered, and location and access to the sea conditioned countries' access to world commodity and factor markets and, consequently, their potential for long term growth.

On the whole, however, real product per head grew in Latin America between 1820 and 1870 at a similar rate to the global average, matching that of the European periphery and proving far higher than that occurring in Asia and Africa. ‘Lost decades’ seems to be an inadequate description of aggregate performance in post-independence Latin America.